Key Points

HSCT in patients with DDX41-related myeloid malignancies is safe and not associated with an increased risk for GVHD but with later relapse.

Using a DDX41mut donor is associated with a risk for donor cell leukemia after HSCT in patients with DDX41-related myeloid malignancies.

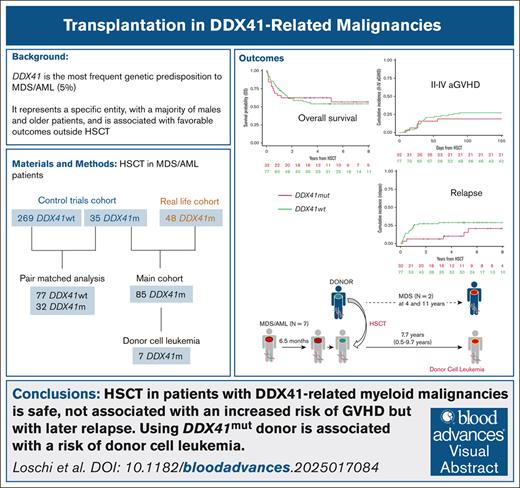

Visual Abstract

Germ line DDX41 mutations (DDX41mut) are identified in ∼5% of myeloid malignancies with an excess of blasts, representing a distinct myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)/acute myeloid leukemia (AML) entity. The disease is associated with better outcomes than DDX41 wild-type (DDX41WT) cases, but patients who do not undergo allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) may experience late relapse. Because of the recent identification of DDX41mut, data on the post-HSCT outcomes remain limited. In this study, we report the HSCT outcomes of 83 patients with DDX41mut MDS/AML. With a median follow-up of 4.4 years, the 2-year leukemia-free survival (LFS) was 68.6% (95% confidence interval [CI], 57.1-77.6) and the 2-year nonrelapse mortality (NRM) was 21.1% (95% CI, 12.9-30.6). We then assessed the impact of DDX41mut using a pair match analysis performed on patients who underwent a transplantation in AML clinical trials. No significant differences were observed between patients with DDX41mut and those with DDX41WT in terms of LFS at 2 years (hazard ratio, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.59-1.90; P = .84), overall survival, NRM, relapse, or graft-versus-host disease incidence. The cumulative incidence of relapse for DDX41mut showed a trend toward a lower relapse rate during the first year then higher after 1 year. Given the familial nature of the disease, we specifically examined patients who relapsed after HSCT with a related donor and identified 7 cases of DDX41mut donor cell leukemia. In this study, HSCT in patients with DDX41mut AML was not associated with an increased risk for toxicity. However, we observed a potential for later relapse, which could potentially be mitigated by selecting related donors based on DDX41 status.

Introduction

Myeloid malignancies with germ line pathogenic mutations in the DEAD-box helicase 41 gene (DDX41mut) are classified as myeloid neoplasms (MNs) with germ line predisposition without a pre-existing platelet disorder or organ dysfunction according to the 2022 World Health Organization.1DDX41mut is the most common genetic predisposition in MNs and is associated with familial myelodysplastic syndromes (MDSs) and acute myeloid leukemias (AMLs), accounting for ∼5% of sporadic MDS/AML cases.2,3 The most recent studies suggest that this subset represents a combined MDS/AML continuum that constitutes an independent and specific entity with favorable outcomes in cohorts treated with hypomethylating agents,4 intensive chemotherapy,5 or, more recently, venetoclax-based combinations.6,7 Because a greater understanding of the disease has only recently been achieved, DDX41 mutational status is not yet incorporated into prognostic scoring systems, such as the Molecular International Prognosis Scoring System for MDS8 and the European LeukemiaNet (ELN) 2022 for AML.9 However, in the context of patients who receive less intensive chemotherapy (azacitidine and venetoclax), it is now classified as favorable in the ELN 2024 classification.10,11 However, despite reports of better response rates to conventional therapies and prolonged survival when compared with wild-type DDX41 cases (DDX41WT), patients with DDX41mut MDS/AML still experience relapse without hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT).4,5

HSCT is the only curative approach for MNs with a germ line predisposition and requires adaptation of the conditioning regimen and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis in certain already identified genetic syndromes, such as Fanconi anemia or short telomere syndromes.12,13 Patients with a recognized germ line predisposition to MNs exhibit a higher incidence of complications after HSCT than those with sporadic disease.14 This includes an increased risk for graft rejection, increased GVHD severity, elevated infection risks, and the development of additional nonhematologic malignancies during later follow-up.15,16 One of these specific conditions related to the germ line feature is donor cell leukemia (DCL) in which a novel hematologic malignancy arises from transplanted donor stem cells in patients with germ line predispositions who receive transplants from related donors that share the same germ line mutation.17

There are limited data on the outcomes of patients with DDX41-related MNs after HSCT, particularly concerning prolonged follow-up after transplantation.18

We report here the posttransplantation outcomes of a retrospective cohort of 83 patients with DDX41mut MDS/AML with prolonged follow-up, along with a pair-matched comparison between patients with DDX41mut AML and patients with DDX41WT AML.

Methods

Patients

We conducted a multicenter, national, retrospective study to identify patients with DDX41mut who received HSCT between 2007 and 2022 at French hematologic centers (Figure 1). We included a cohort of 304 patients with AML from clinical trials (35 DDX41mut and 269 DDX41WT) who received a transplant in their first complete remission (CR). This cohort was derived from a group of 2186 patients with AML that was previously reported in a study focused on hematologic outcomes after intensive chemotherapy5 (supplemental Methods; supplemental Table 1). In addition, we collected data on 48 real-world patients with DDX41mut who received a transplant, including 29 AML and 19 MDS cases. Using the Francophone Society of Stem Cell Transplantation (Société Francophone de Greffe de Moelle et de Thérapie Cellulaire) registry, we reported the posttransplantation outcomes of the 83 patients with DDX41mut MDS/AML and compared the outcomes between patients with DDX41mut and those with DDX41WT in the trial cohort of 304 patients with AML (Figure 1).

This study was approved by a national review board and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and French ethical regulations.

DNA sequencing, variant classification, and germ line origin

Mononuclear cells from bone marrow samples were isolated using Ficoll gradient centrifugation, and peripheral blood was only used as an alternative when bone marrow DNA quality was insufficient for sequencing. Genomic DNA was extracted using standard procedures and was analyzed using capture-based next-generation sequencing. Only patients with DDX41 variants who exhibited a variant allele frequency >40%, suggesting a possible germ line origin, and a frequency in the normal population of <0.1% (Genome Aggregation Database) were consistently included and collectively reviewed for classification according to the guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology.19DDX41 variants were interpreted as causal if they were classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic according to these guidelines. The presence of an additional somatic DDX41 mutation was also considered strong evidence for causality. In recipients with DCL, the germ line origin was confirmed for all patients in extra-hematopoietic tissues (3 using fibroblasts, 3 using oral epithelial cells, and 1 using bone marrow cells during complete remission) as recommended by the recent guidelines from the United Kingdom Cancer Genetics Group, CanGene-CanVar, and the National Health Service (NHS) England Haematological Oncology Working Group.20

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was leukemia-free survival (LFS), defined as the time from transplant to the first event of relapse or death. Secondary endpoints included overall survival (OS), cumulative incidence of relapse (CIR), nonrelapse mortality (NRM), incidences of acute GVHD (aGVHD) grade 2 to 4 and 3 to 4, chronic GVHD (cGVHD), and extensive cGVHD. OS was defined as the time from transplant to death. Relapse was defined as the first evidence of disease recurrence or progression after transplantation.21 NRM was defined as the time from transplant to death in the absence of relapse. CIR and NRM were mutually competing events. GVHD outcomes were scored according to the Mount Sinai Acute GVHD International Consortium and National Institutes of Health criteria for aGVHD and cGVHD, respectively,22,23 with relapse and death as competing events.

Statistical analysis

For all analyses, the quantitative variables were described as median, first and third quartiles, and minimum and maximum values. Qualitative variables were described as number and percentage. Different groups (DDX41mut and DDX41WT or AML and MDS) were compared using the Wilcoxon test for quantitative variables and the χ2 or exact Fisher test for qualitative variables. LFS and OS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and outcomes with competing events were estimated using the cumulative incidence function. The median follow-up was calculated using the reverse Kaplan-Meier estimator.

A pair-matched analysis that compared patients with DDX41mut AML with patients with DDX41WT AML from the trial cohort (304 patients with AML) was performed using both exact matching and propensity score matching (Figure 1). The variables that were used for exact matching included donor type (matched sibling donors, matched unrelated donors (MUDs), mismatched unrelated donors, and unrelated cord blood), source of cells (bone marrow, peripheral blood, or cord blood), patient sex, and ELN-2017 classification (favorable, intermediate, and adverse). Propensity score matching was applied based on age at transplant, donor’s female-to-male ratio, conditioning regimen (reduced intensity conditioning, myeloablative Conditioning [MAC] chemo, and MAC total body irradiation), and the use of antithymoglobulin (ATG).

The pair-matching method allowed up to 3 DDX41WT matches for each DDX41mut patient. Three DDX41WT matches were found for 20 DDX41mut patients; for 5 patients, 2 DDX41WT matches were found; for 7 patients, only 1 match was found; and finally, for 3 DDX41mut patients, no DDX41WT matches could be identified. Finally, of the 304 patients, 32 DDX41mut patients were pair-matched with 77 DDX41WT patients. The outcomes were compared and tested between groups using Cox models, including a cluster term for matched groups. Because the CIR was nonproportional, the impact of DDX41 mutational status was evaluated as a time-dependent effect, split into before and after 1 year. Time-specific estimations of the outcomes and hazard ratios (HRs) were provided, along with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All tests were 2-sided with a significance level set at 5%. The analysis was performed using R Core Team software, version 4.2.3.24

Results

Features and HSCT outcomes of the 83 patients with DDX41mut MDS/AML

The clinical characteristics at HSCT of the 83 patients with DDX41mut (64 AML and 19 MDS) are presented in Table 1. The median age at diagnosis and at transplantation was 60.6 years (interquartile range, 53.7-64.3) and 61.6 years (interquartile range, 55-65.4), respectively. Most patients were male (84.3%), and the median follow-up from HSCT was 4.4 years (95% CI, 3.3-5.5). According to the ELN 2017 classification,25 at diagnosis, patients with AML were classified as intermediate risk (68.6%), and the remaining were classified as adverse risk (31.4%). At the time of transplantation, 60 (93.8%) patients with AML had achieved CR1, whereas the 4 remaining patients with AML received the transplant in CR2. At the time of transplantation, 9 patients with MDS had previously achieved hematologic response (including 8 with CR), 2 (11.1%) had progressive disease, 2 (11.1%) had primary induction failure, and 5 (27.8%) received upfront transplantation (for 1 patients with MDS, the disease status at transplantation was unknown). About half of the patients received a MUD transplantation (n = 38; 45.8%). Additional donor and transplant characteristics are described in Table 1. The source of stem cells was peripheral blood for 69 patients (83.1%). A total of 46 patients with AML and 16 patients with MDS received a reduced-intensity conditioning, corresponding to 74.7% of the patients. GVHD prophylaxis was based on a cyclosporine-based regimen for 79 (95%) patients, whereas 58 (69.9%) underwent in vivo T-cell depletion using ATG. Notably, for all patients who had a haplo-identical donor (n = 11) and 1 patient who received a graft from a mismatched unrelated donor, GVHD prophylaxis consisted of posttransplantation cyclophosphamide (PT-Cy), combined with cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil.

Characteristics of the 83 patients with DDX41mut MDS or AML

| Modalities . | All (N = 83) . | AML (n = 64) . | MDS (n = 19) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | |||

| Median (IQR) | 60.6 (53.7-64.3) | 60 (49.6-64.2) | 61.9 (59.6-64.3) |

| Age at HSCT | |||

| Median (IQR) | 61.63 (55-65.4) | 60.6 (50.2-64.7) | 64.6 (61.8-65.8) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Female | 13 (15.7) | 10 (15.6) | 3 (15.8) |

| Male | 70 (84.3) | 54 (84.4) | 16 (84.2) |

| Disease status at HSCT, n (%) | |||

| CR1 | 63 (78.8) | 58 (93.5) | 5 (27.8) |

| CR2 | 4 (4.9) | 4 (6.5) | 0 (0) |

| CR (number unknown) | 3 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 3 (16.7) |

| Primary induction failure | 2 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (11.1) |

| Improvement (no CR) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.6) |

| Progressive | 2 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (11.1) |

| Upfront HSCT | 5 (6.2) | 0 (0) | 5 (27.8) |

| Not available | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Donor type, n (%) | |||

| MSD | 24 (28.9) | 17 (26.6) | 7 (36.8) |

| Matched other relative | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0) |

| MMRD | 11 (13.3) | 8 (12.5) | 3 (15.8) |

| MUD 10/10 | 38 (45.8) | 30 (46.9) | 8 (42.1) |

| MMUD 9/10 | 5 (6) | 5 (7.8) | 0 (0) |

| UD (unknown mismatch) | 2 (2.4) | 2 (3.1) | 0 (0) |

| CBU | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.6) | 1 (5.3) |

| Source of stem cells, n (%) | |||

| BM | 10 (12) | 10 (15.6) | 0 (0) |

| BM+PB | 2 (2.4) | 2 (3.1) | 0 (0) |

| PB | 69 (83.1) | 51 (79.7) | 18 (94.7) |

| Double CBU | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.6) | 1 (5.3) |

| Myeloablative regimen, n (%) | |||

| No | 62 (74.7) | 46 (71.9) | 16 (84.2) |

| Yes | 21 (25.3) | 18 (28.1) | 3 (15.8) |

| TBI, n (%) | |||

| No | 71 (85.5) | 53 (82.8) | 18 (94.7) |

| Yes | 12 (14.5) | 11 (17.2) | 1 (5.3) |

| ATG, n (%) | |||

| No | 25 (30.1) | 20 (31.2) | 5 (26.3) |

| Yes | 58 (69.9) | 44 (68.8) | 14 (73.7) |

| GVHD prophylaxis, n (%) | |||

| No | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0) |

| ATG only | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.6) | 1 (5.3) |

| CSA | 13 (15.7) | 10 (15.6) | 3 (15.8) |

| CSA+MMF | 37 (44.6) | 25 (39.1) | 12 (63.2) |

| CSA+MTX | 18 (21.7) | 18 (28.1) | 0 (0) |

| MMF+TACRO | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0) |

| PTCY+CSA+MMF | 12 (14.5) | 9 (14.1) | 3 (15.8) |

| Modalities . | All (N = 83) . | AML (n = 64) . | MDS (n = 19) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | |||

| Median (IQR) | 60.6 (53.7-64.3) | 60 (49.6-64.2) | 61.9 (59.6-64.3) |

| Age at HSCT | |||

| Median (IQR) | 61.63 (55-65.4) | 60.6 (50.2-64.7) | 64.6 (61.8-65.8) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Female | 13 (15.7) | 10 (15.6) | 3 (15.8) |

| Male | 70 (84.3) | 54 (84.4) | 16 (84.2) |

| Disease status at HSCT, n (%) | |||

| CR1 | 63 (78.8) | 58 (93.5) | 5 (27.8) |

| CR2 | 4 (4.9) | 4 (6.5) | 0 (0) |

| CR (number unknown) | 3 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 3 (16.7) |

| Primary induction failure | 2 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (11.1) |

| Improvement (no CR) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.6) |

| Progressive | 2 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (11.1) |

| Upfront HSCT | 5 (6.2) | 0 (0) | 5 (27.8) |

| Not available | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Donor type, n (%) | |||

| MSD | 24 (28.9) | 17 (26.6) | 7 (36.8) |

| Matched other relative | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0) |

| MMRD | 11 (13.3) | 8 (12.5) | 3 (15.8) |

| MUD 10/10 | 38 (45.8) | 30 (46.9) | 8 (42.1) |

| MMUD 9/10 | 5 (6) | 5 (7.8) | 0 (0) |

| UD (unknown mismatch) | 2 (2.4) | 2 (3.1) | 0 (0) |

| CBU | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.6) | 1 (5.3) |

| Source of stem cells, n (%) | |||

| BM | 10 (12) | 10 (15.6) | 0 (0) |

| BM+PB | 2 (2.4) | 2 (3.1) | 0 (0) |

| PB | 69 (83.1) | 51 (79.7) | 18 (94.7) |

| Double CBU | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.6) | 1 (5.3) |

| Myeloablative regimen, n (%) | |||

| No | 62 (74.7) | 46 (71.9) | 16 (84.2) |

| Yes | 21 (25.3) | 18 (28.1) | 3 (15.8) |

| TBI, n (%) | |||

| No | 71 (85.5) | 53 (82.8) | 18 (94.7) |

| Yes | 12 (14.5) | 11 (17.2) | 1 (5.3) |

| ATG, n (%) | |||

| No | 25 (30.1) | 20 (31.2) | 5 (26.3) |

| Yes | 58 (69.9) | 44 (68.8) | 14 (73.7) |

| GVHD prophylaxis, n (%) | |||

| No | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0) |

| ATG only | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.6) | 1 (5.3) |

| CSA | 13 (15.7) | 10 (15.6) | 3 (15.8) |

| CSA+MMF | 37 (44.6) | 25 (39.1) | 12 (63.2) |

| CSA+MTX | 18 (21.7) | 18 (28.1) | 0 (0) |

| MMF+TACRO | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0) |

| PTCY+CSA+MMF | 12 (14.5) | 9 (14.1) | 3 (15.8) |

BM, bone marrow; CBU, cord blood unit; CSA, ciclosporin A; IQR, interquartile range; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MMRD, mismatched related donor; MMUD, mismatched unrelated donor; MSD, matched sibling donor; MTX, methotrexate; PB, peripheral blood; RIC, reduced intensity conditioning; TACRO, tacrolimus; TBI, total body irradiation; TCD, T-cells depletion; UD, unrelated donor.

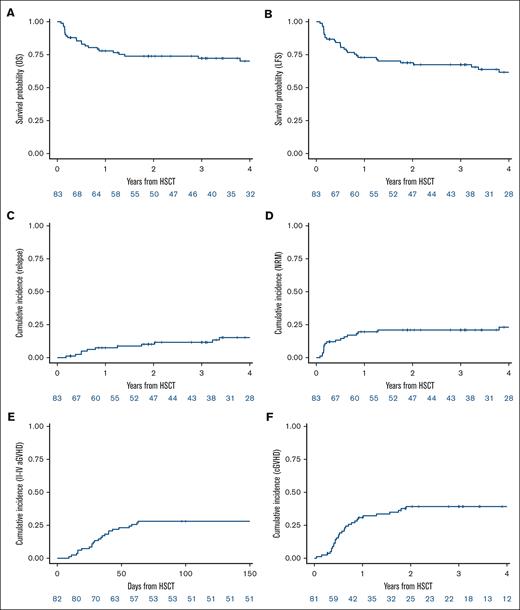

With a median follow-up of 4.7 years (95% CI, 3.4-5.9), the 2-year LFS was 68.9% (95% CI, 57.5-77.8) (Figure 2B; supplemental Figure 1B). The 2-year OS was 73.9% (95% CI, 62.8-82.1) (Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 1A). The CIR at 2 years was 10.2% (95% CI, 4.7-18.1) (Figure 2C; supplemental Figure 1C). The median time to relapse was 28.5 months (range, 2-124). The cumulative incidence of NRM at 2 years was 21% (95% CI, 12.8-30.5) (Figure 2D; supplemental Figure 1D). The cumulative incidence of grade 2 to 4 aGVHD at day 100 was 28% (95% CI, 18.8-38.1) (Figure 2E; supplemental Figure 1E), with the cumulative incidence of grade 3 to 4 aGVHD at day 100 being 14.6% (95% CI, 8-23.2) (supplemental Figure 1F). The cumulative incidence of cGVHD at 2 years was 39.2% (95% CI, 28.2-50.1) (Figure 2F; supplemental Figure 1G). The cumulative incidence of extensive cGVHD at 2 years was 9.6% (95% CI, 4.2-17.7) (supplemental Figure 1H). The transplantation outcomes are detailed in Table 2. A total of 28 patients died; 9 died from relapse and 19 from NRM with 6 patients dying as a consequence of GVHD (supplemental Table 2). During follow-up, 1 patient developed secondary nonhematologic malignancies (esophageal carcinoma).

Outcomes of the 83 patients with DDX41mut. (A) OS. (B) LFS. (C) Cumulative incidence of relapse. (D) Cumulative incidence of NRM. (E) Cumulative incidence of grade 2 to 4 aGVHD. (F) Cumulative incidence of cGVHD.

Outcomes of the 83 patients with DDX41mut. (A) OS. (B) LFS. (C) Cumulative incidence of relapse. (D) Cumulative incidence of NRM. (E) Cumulative incidence of grade 2 to 4 aGVHD. (F) Cumulative incidence of cGVHD.

Transplantation outcome of the 83 patients with DDX41mut patients

| Outcomes . | All patients (N = 83) . | AML (n = 64) . | MDS (n = 19) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estimation (95% CI) . | Estimation (95% CI) . | Estimation (95% CI) . | |

| Median FU, y | 4.7 (3.4-5.9) | 4.8 (3.4-6.5) | 3.9 (1.9-5.9) |

| OS (2 years) | 73.9 (62.8-82.1) | 72.7 (59.7-82.1) | 78 (51.5-91.1) |

| LFS (2 years) | 68.9 (57.5-77.8) | 71.2 (58.3-80.8) | 61.3 (35.5-79.3) |

| RI (2 years) | 10.2 (4.7-18.1) | 6.5 (2.1-14.7) | 22.3 (6.6-43.7) |

| NRM (2 years) | 21 (12.8-30.5) | 22.2 (12.8-33.2) | 16.4 (3.8-36.9) |

| aGVHD-II/IV (100 days) | 28 (18.8-38.1) | 25.4 (15.4-36.7) | 36.8 (15.9-58.1) |

| aGVHD-III/IV (100 days) | 14.6 (8-23.2) | 12.7 (5.9-22.2) | 21.1 (6.3-41.6) |

| cGVHD (2 years) | 39.2 (28.2-50.1) | 37.9 (25.6-50) | 43.7 (18.7-66.5) |

| cGVHD Ext (2 years) | 9.6 (4.2-17.7) | 6.9 (2.2-15.4) | 18.8 (4.3-41.3) |

| Outcomes . | All patients (N = 83) . | AML (n = 64) . | MDS (n = 19) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estimation (95% CI) . | Estimation (95% CI) . | Estimation (95% CI) . | |

| Median FU, y | 4.7 (3.4-5.9) | 4.8 (3.4-6.5) | 3.9 (1.9-5.9) |

| OS (2 years) | 73.9 (62.8-82.1) | 72.7 (59.7-82.1) | 78 (51.5-91.1) |

| LFS (2 years) | 68.9 (57.5-77.8) | 71.2 (58.3-80.8) | 61.3 (35.5-79.3) |

| RI (2 years) | 10.2 (4.7-18.1) | 6.5 (2.1-14.7) | 22.3 (6.6-43.7) |

| NRM (2 years) | 21 (12.8-30.5) | 22.2 (12.8-33.2) | 16.4 (3.8-36.9) |

| aGVHD-II/IV (100 days) | 28 (18.8-38.1) | 25.4 (15.4-36.7) | 36.8 (15.9-58.1) |

| aGVHD-III/IV (100 days) | 14.6 (8-23.2) | 12.7 (5.9-22.2) | 21.1 (6.3-41.6) |

| cGVHD (2 years) | 39.2 (28.2-50.1) | 37.9 (25.6-50) | 43.7 (18.7-66.5) |

| cGVHD Ext (2 years) | 9.6 (4.2-17.7) | 6.9 (2.2-15.4) | 18.8 (4.3-41.3) |

Ext, extensive; FU, follow-up; RI, relapse incidence.

Among the 12 patients who received PT-Cy as GVHD prophylaxis, 4 had MDS and 8 had AML. All but 1 recipient of these 12 patients received a graft from a mismatched related donor, and all but 1 received a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen. For all recipients, GVHD prophylaxis consisted of a combination of PT-Cy, cyclosporine, and mycophenolate mofetil. With a median follow-up of 2 years (95% CI, 0.3-5.3) for these 12 patients, the 2-year LFS was 75% (95% CI, 40.8-91.2), the 2-year OS was 75% (95% CI, 40.8-91.2), the 2-year CIR was 0 because no patients relapsed, and the 2-year NRM was 25% (95% CI, 5.4-51.7). The cumulative incidence of grade 2 to 4 aGVHD at day 100 was 33.3% (95% CI, 9.4-60) with a cumulative incidence of grade 3 to 4 aGVHD at day 100 of 8.3% (95% CI, 0.4-32.3). The cumulative incidence of cGVHD at 2 years was 8.3% (95% CI, 2.6-52) with no patient developing extensive cGVHD. One patient died from aGVHD, and 2 other patients died from pulmonary infections unrelated to GVHD (supplemental Table 3).

Pair-matched analysis comparing the transplantation outcomes of patients with DDX41mut and patients with DDX41WT

To obtain comparable groups to analyze the impact of DDX41 status on HSCT outcomes, 32 patients with DDX41mut AML were pair-matched with 77 patients with DDX41WT AML in CR1 after intensive chemotherapy (Table 3). The median age at diagnosis was 61.1 years (95% CI, 49-64.2) in the DDX41mut group and 58.2 years (95% CI, 49.1-64.1) in the DDX41WT group. The median age at HSCT was 61.5 years (95% CI, 49.6-64.7) in the DDX41mut group and 58.9 years (95% CI, 49.5-64.7) in the DDX41WT group. There was a male predominance in both groups (81.8% among DDX41mut and 81.2% among DDX41WT). The median time to transplantation was 5.9 months (95% CI, 5-6.6) in the DDX41mut group and 5.4 months (95% CI, 4.6-6.4) in the DDX41WT group. According to the ELN 2017 classification, 22 (69%) patients with DDX41mut had intermediate risk and 10 (31%) had adverse risk, whereas 49 (64%) patients with DDX41WT had intermediate risk and 28 (36%) had adverse risk. About half of the patients in both groups received a graft from an MUD, whereas 31% of patients with DDX41mut and 35% of patients with DDX41WT received a transplantation from a sibling donor. The donor was haploidentical in 6% of DDX41mut recipients and in 5% of DDX41WT recipients. The remaining patients in both groups received a graft from a mismatched unrelated donor (9% in both groups). Peripheral blood stem cells were the main stem cell source, accounting for 81% of the HSCTs in both groups. The conditioning regimen was myeloablative for 28% of the patients with DDX41mut and for 35% of the patients with DDX41WT. The GVHD prophylaxis regimen included ATG in 66% of patients with DDX41mut and in 61% of patients with DDX41WT.

Patients’ characteristics after matched pairing of 109 patients with AML

| Modalities . | DDX41 WT (n = 77) . | DDX41 MUT (n = 32) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | ||

| Median (IQR) | 58.2 (49.1-64.1) | 61.1 (49-64.2) |

| (Range) | (20-71.4) | (35.3-72.3) |

| Age at HSCT | ||

| Median (IQR) | 58.9 (49.5-64.7) | 61.5 (49.6-64.7) |

| (Range) | (20.6-71.8) | (36.2-72.6) |

| Months between diagnosis and HSCT | ||

| Median (IQR) | 5.4 (4.6-6.4) | 5.9 (5-6.6) |

| (Range) | (3-144.5) | (3.7-10) |

| Patient sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 14 (18.2) | 6 (18.8) |

| Male | 63 (81.8) | 26 (81.2) |

| Female to male, n (%) | ||

| No | 56 (72.7) | 22 (68.8) |

| Yes | 21 (27.3) | 10 (31.2) |

| ELN status, n (%) | ||

| Int | 49 (63.6) | 22 (68.8) |

| Adv | 28 (36.4) | 10 (31.2) |

| Donor type, n (%) | ||

| MSD | 27 (35.1) | 10 (31.2) |

| MMRD | 4 (5.2) | 2 (6.2) |

| MUD | 39 (50.6) | 17 (53.1) |

| MMUD | 7 (9.1) | 3 (9.4) |

| Source of cells, n (%) | ||

| BM | 15 (19.5) | 6 (18.8) |

| PB | 62 (80.5) | 26 (81.2) |

| Myeloablative regimen, n (%) | ||

| No | 50 (64.9) | 23 (71.9) |

| Yes | 27 (35.1) | 9 (28.1) |

| TBI, n (%) | ||

| No | 63 (81.8) | 26 (81.2) |

| Yes | 14 (18.2) | 6 (18.8) |

| MAC TBI, n (%) | ||

| RIC | 50 (64.9) | 23 (71.9) |

| MAC chemo | 25 (32.5) | 7 (21.9) |

| MAC TBI | 2 (2.6) | 2 (6.2) |

| In vivo TCD, n (%) | ||

| No | 30 (39) | 11 (34.4) |

| ATG | 47 (61) | 21 (65.6) |

| GVHD prevention, n (%) | ||

| CSA | 13 (16.9) | 5 (15.6) |

| CSA+MMF | 27 (35.1) | 12 (37.5) |

| CSA+MMF+TACRO | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| CSA+MTX | 32 (41.6) | 13 (40.6) |

| MTX+MMF | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) |

| PTCY+CSA | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) |

| PTCY+CSA+MMF | 2 (2.6) | 1 (3.1) |

| Modalities . | DDX41 WT (n = 77) . | DDX41 MUT (n = 32) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | ||

| Median (IQR) | 58.2 (49.1-64.1) | 61.1 (49-64.2) |

| (Range) | (20-71.4) | (35.3-72.3) |

| Age at HSCT | ||

| Median (IQR) | 58.9 (49.5-64.7) | 61.5 (49.6-64.7) |

| (Range) | (20.6-71.8) | (36.2-72.6) |

| Months between diagnosis and HSCT | ||

| Median (IQR) | 5.4 (4.6-6.4) | 5.9 (5-6.6) |

| (Range) | (3-144.5) | (3.7-10) |

| Patient sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 14 (18.2) | 6 (18.8) |

| Male | 63 (81.8) | 26 (81.2) |

| Female to male, n (%) | ||

| No | 56 (72.7) | 22 (68.8) |

| Yes | 21 (27.3) | 10 (31.2) |

| ELN status, n (%) | ||

| Int | 49 (63.6) | 22 (68.8) |

| Adv | 28 (36.4) | 10 (31.2) |

| Donor type, n (%) | ||

| MSD | 27 (35.1) | 10 (31.2) |

| MMRD | 4 (5.2) | 2 (6.2) |

| MUD | 39 (50.6) | 17 (53.1) |

| MMUD | 7 (9.1) | 3 (9.4) |

| Source of cells, n (%) | ||

| BM | 15 (19.5) | 6 (18.8) |

| PB | 62 (80.5) | 26 (81.2) |

| Myeloablative regimen, n (%) | ||

| No | 50 (64.9) | 23 (71.9) |

| Yes | 27 (35.1) | 9 (28.1) |

| TBI, n (%) | ||

| No | 63 (81.8) | 26 (81.2) |

| Yes | 14 (18.2) | 6 (18.8) |

| MAC TBI, n (%) | ||

| RIC | 50 (64.9) | 23 (71.9) |

| MAC chemo | 25 (32.5) | 7 (21.9) |

| MAC TBI | 2 (2.6) | 2 (6.2) |

| In vivo TCD, n (%) | ||

| No | 30 (39) | 11 (34.4) |

| ATG | 47 (61) | 21 (65.6) |

| GVHD prevention, n (%) | ||

| CSA | 13 (16.9) | 5 (15.6) |

| CSA+MMF | 27 (35.1) | 12 (37.5) |

| CSA+MMF+TACRO | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| CSA+MTX | 32 (41.6) | 13 (40.6) |

| MTX+MMF | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) |

| PTCY+CSA | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) |

| PTCY+CSA+MMF | 2 (2.6) | 1 (3.1) |

The median follow-up in the pair-matched cohort was 6.1 years (95% CI, 5-7.1), being 5.9 years (95% CI, 3.4-8) for patients with DDX41mut and 6.2 years (95% CI, 5-7.1) for patients with DDX41WT. The patient outcomes are detailed in Table 4. There was no significant difference in the LFS at 6 years between patients with DDX41mut and those with DDX41WT (6-year LFS: 47.9%; 95% CI, 27.8-65.5 vs 52.1%; 95% CI, 40.1-62.7; HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.59-1.90; P = .84; Figure 3A). There was no significant difference in the OS between patients with DDX41mut and those with DDX41WT (6-year OS: 56.8%; 95% CI, 36.5-72.8 vs 54.2%; 95% CI, 42-64.8; HR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.45-1.93; P = .91; Figure 3B). In total, 13 of the 32 patients with DDX41mut died during follow-up with NRM being the main cause of death (69.2%), whereas in the DDX41WT group, 34 of 77 died and the main cause of death was relapse (55.9%). The median time to death from transplantation was 4.8 months in patients with DDX41mut and 9.6 months in the DDX41WT group. There was no statistical difference in relapse incidence at 6 years between patients with DDX41mut and patients with DDX41WT (6-year relapse incidence: 20.8%; 95% CI, 6.9-39.8 vs 29%; 95% CI, 19.2-39.5; Figure 3C). However, the median time to relapse was 50.1 months in the DDX41mut group vs 7.5 months in the DDX41WT group. Although not statistically significant, there was a trend toward fewer relapses in the first year after HSCT (HR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.07-1.14; P = .08) and, conversely, a trend toward a higher relapse incidence 1 year after HSCT (HR, 7.51; 95% CI, 0.86-65.51; P = .07) among patients with DDX41mut.

Post-HSCT outcomes in pair-matched patients

| Outcomes . | Matched patients . | DDX41 WT (n = 77) . | DDX41 MUT (n = 32) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimation (95% CI) . | Estimation (95% CI) . | Estimation (95% CI) . | ||

| Median FU, y | 6.1 (5-7.1) | 6.2 (5-7.1) | 5.9 (3.4-8) | |

| OS (2 years) | 62 (52.2-70.4) | 61.7 (49.8-71.6) | 62.5 (43.5-76.7) | .91 |

| OS (6 years) | 55.1 (44.9-64.2) | 54.2 (42-64.8) | 56.8 (36.5-72.8) | |

| LFS (2 years) | 59.5 (49.6-68) | 58.2 (46.3-68.3) | 62.5 (43.5-76.7) | .84 |

| LFS (6 years) | 51.1 (40.9-60.5) | 52.1 (40.1-62.7) | 47.9 (27.8-65.5) | |

| RI (2 years) | 21.2 (14-29.3) | 27.5 (17.9-37.8) | 6.2 (1.1-18.4) | .07 |

| RI (6 years) | 26.3 (18-35.3) | 29 (19.2-39.5) | 20.8 (6.9-39.8) | |

| NRM (2 years) | 19.3 (12.5-27.2) | 14.4 (7.6-23.2) | 31.2 (16.1-47.6) | .19 |

| NRM (6 years) | 22.6 (15.1-31) | 18.9 (10.9-28.7) | 31.2 (16.1-47.6) | |

| aGVHD-II/IV (100 days) | 24.8 (17.1-33.2) | 27.3 (17.8-37.6) | 18.8 (7.5-34) | .33 |

| aGVHD-III/IV (100 days) | 8.3 (4-14.4) | 7.8 (3.2-15.2) | 9.4 (2.3-22.5) | .79 |

| cGVHD (2 years) | 37.7 (28.6-46.8) | 40.4 (29.3-51.2) | 31.2 (16-47.8) | .34 |

| cGVHD (6 years) | 37.7 (28.6-46.8) | 40.4 (29.3-51.2) | 31.2 (16-47.8) | |

| cGVHD Ext (2 years) | 14.3 (8.4-21.8) | 18.7 (10.8-28.4) | 3.3 (0.2-14.9) | .07 |

| cGVHD Ext (6 years) | 14.3 (8.4-21.8) | 18.7 (10.8-28.4) | 3.3 (0.2-14.9) |

| Outcomes . | Matched patients . | DDX41 WT (n = 77) . | DDX41 MUT (n = 32) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimation (95% CI) . | Estimation (95% CI) . | Estimation (95% CI) . | ||

| Median FU, y | 6.1 (5-7.1) | 6.2 (5-7.1) | 5.9 (3.4-8) | |

| OS (2 years) | 62 (52.2-70.4) | 61.7 (49.8-71.6) | 62.5 (43.5-76.7) | .91 |

| OS (6 years) | 55.1 (44.9-64.2) | 54.2 (42-64.8) | 56.8 (36.5-72.8) | |

| LFS (2 years) | 59.5 (49.6-68) | 58.2 (46.3-68.3) | 62.5 (43.5-76.7) | .84 |

| LFS (6 years) | 51.1 (40.9-60.5) | 52.1 (40.1-62.7) | 47.9 (27.8-65.5) | |

| RI (2 years) | 21.2 (14-29.3) | 27.5 (17.9-37.8) | 6.2 (1.1-18.4) | .07 |

| RI (6 years) | 26.3 (18-35.3) | 29 (19.2-39.5) | 20.8 (6.9-39.8) | |

| NRM (2 years) | 19.3 (12.5-27.2) | 14.4 (7.6-23.2) | 31.2 (16.1-47.6) | .19 |

| NRM (6 years) | 22.6 (15.1-31) | 18.9 (10.9-28.7) | 31.2 (16.1-47.6) | |

| aGVHD-II/IV (100 days) | 24.8 (17.1-33.2) | 27.3 (17.8-37.6) | 18.8 (7.5-34) | .33 |

| aGVHD-III/IV (100 days) | 8.3 (4-14.4) | 7.8 (3.2-15.2) | 9.4 (2.3-22.5) | .79 |

| cGVHD (2 years) | 37.7 (28.6-46.8) | 40.4 (29.3-51.2) | 31.2 (16-47.8) | .34 |

| cGVHD (6 years) | 37.7 (28.6-46.8) | 40.4 (29.3-51.2) | 31.2 (16-47.8) | |

| cGVHD Ext (2 years) | 14.3 (8.4-21.8) | 18.7 (10.8-28.4) | 3.3 (0.2-14.9) | .07 |

| cGVHD Ext (6 years) | 14.3 (8.4-21.8) | 18.7 (10.8-28.4) | 3.3 (0.2-14.9) |

Outcomes of the 109 pair-matched patients with AML (77 DDX41WT and 32 DDX41mut). (A) LFS. (B) OS. (C) Cumulative incidence of relapse. (D) Cumulative incidence of NRM. (E) Cumulative incidence of grade 2 to 4 acute GVHD. (F) Cumulative incidence of cGVHD.

Outcomes of the 109 pair-matched patients with AML (77 DDX41WT and 32 DDX41mut). (A) LFS. (B) OS. (C) Cumulative incidence of relapse. (D) Cumulative incidence of NRM. (E) Cumulative incidence of grade 2 to 4 acute GVHD. (F) Cumulative incidence of cGVHD.

Regarding NRM, there was no significant difference between the 2 groups (6-year NRM: 31.2% for DDX41mut vs 18.9% for DDX41WT; HR, 1.73; 95% CI, 0.76-3.93; P = .19; Figure 3D). Among the 25 patients who died of NRM (10 DDX41mut and 15 DDX41WT), the main causes were infections (6 patients, including 2 DDX41mut) and GVHD (8 patients, including 3 DDX41mut). The causes of death are detailed in supplemental Table 3. Regarding GVHD prophylaxis, 4 patients (1 DDX41mut and 3 DDX41WT) received PT-Cy. Among these patients, all received a graft from a haploidentical donor. There was no significant difference in grade 2 to 4 aGVHD (100-day grade 2-4 aGVHD: 18.8%; 95% CI, 7.5-34 in DDX41mut and 27.3%; 95% CI, 17.8-37.6 in DDX41WT; HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.60-1.50; P = .33; Figure 3E) nor in grade 3 to 4 aGVHD (100-day grade 3-4 aGVHD: 9.4%; 95% CI, 2.3-22.5 in DDX41mut and 7.8%; 95% CI, 3.2-15.2 in DDX41WT; HR, 1.23; 0.37-5.59; P = .79; supplemental Figure 2A). There was no significant difference in cGVHD between the DDX41mut and DDX41WT groups (6-year cGVHD: 31.2%; 95% CI, 16-47.8 in DDX41mut and 40.4%; 95% CI, 29.3-51.2 in DDX41WT; HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.33-1.46; P = .36; Figure 3F). Finally, regarding extensive cGVHD, a trend for less extensive cGVHD was observed among patients with DDX41mut (6-year extensive cGVHD: 3.3%; 95% CI, 0.2-14.9 in DDX41mut and 18.7%; 95% CI, 10.8-28.4 in DDX41WT; HR, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.02-1.18; P = .07; supplemental Figure 2B).

Characteristics and outcomes of patients with posttransplantation donor cells leukemia

For patients who relapsed after a matched related donor transplantation, a major concern was the DDX41 status of the donor at the time of transplantation. In this study, HSCT was performed between 2007 and 2022, a period during which DDX41 screening was not routinely performed. Screening for the DDX41 germ line mutation in related potential donors has only been recently implemented in France at specific centers. Among the 83 patients with DDX41mut who received a transplant, 11 relapsed after a related donor transplantation. Among these, at the time of relapse, 6 had a donor cell chimerism of 100% and 1 had a chimerism of 95% that persisted over time, indicating leukemia of donor cell origin in 7 patients (Figure 4; supplemental Figure 3; supplemental Table 5). The presence of the germ line DDX41 mutation identified in recipients was confirmed in peripheral blood samples from 5 of the 7 donors.

DCL. Features and outcomes of the 7 patients who experienced DCL after a first related HSCT.

DCL. Features and outcomes of the 7 patients who experienced DCL after a first related HSCT.

Six of the 7 patients were male. At diagnosis before HSCT, they presented with MDS with excess blasts (n = 4) or AML (n = 3) at a median age of 58 years (43-64). All 7 patients had a germ line DDX41mut that was confirmed either in fibroblast culture or buccal smear. The karyotype was normal for 4 of them, and the others had translocations t(6;17), t(X;3), and del(20q). The somatic landscape revealed few somatic mutations except for somatic DDX41mut. Notably, 3 patients had a family history of MDS and/or AML. As a bridge to transplantation, 5 patients received intensive chemotherapy, and 1 patient received azacitidine. The median age of the recipients at HSCT was 59 years (43-65). The median time from diagnosis to transplantation was 7 months (3-58). Only 1 patient received MAC. For 6 patients, the graft source was peripheral blood stem cells, and 1 patient received bone marrow cells. Three patients developed grade 1 aGVHD, whereas 4 had no aGVHD. Half of the patients experienced cGVHD, most of them with limited severity.

The median time to relapse with donor cells was 86 months (6-116) after transplantation. The karyotype was normal for 6 patients, and the karyotype was unavailable for 1 case. The molecular genetic profile of the disease was available for all patients at diagnosis and relapse (supplemental Table 5; supplemental Figure 3). Subsequently, 3 patients received azacitidine, and 1 patient received intensive chemotherapy. Four patients underwent a second allogeneic HSCT. The median age at the second transplantation was 64 years (53-68). Regarding the outcome of the 3 patients who did not receive a second transplantation for their DCL, one achieved CR after azacitidine, and 2 died from disease progression. The timelines for these patients are detailed in supplemental Figure 3.

All 7 patients who relapsed originally received transplants from an HLA-identical sibling. All donors were male. Donors had normal blood cell counts at the time of donation at a median age of 53 years (40-61). Follow-up data were available for 6 of the 7 donors. One donor developed MDS with excess blasts, a normal karyotype, and acquired a somatic DDX41 mutation 11 years after donation. He received induction chemotherapy with CPX351, achieved CR, and proceeded to HSCT with an unrelated donor and is alive at the last follow-up. Another donor developed MDS, suspected to be a consequence of neutropenia and thrombocytopenia, with a normal karyotype 4 years after donation. The other 4 donors are alive with no signs of MN at 7, 10, 16, and 17 years after stem cell harvest, respectively.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this report is on the largest cohort of post-HSCT outcomes in patients with DDX41-related myeloid malignancies and the first pair-matched comparison (DDX41mut vs DDX41WT) in this context. With prolonged follow-up, we were able to demonstrate that DDX41mut in our study was not associated with a shorter OS, LFS, nor higher rates of toxicity.

In 2022, Baranwal et al reported the outcome of 13 patients with DDX41mut who received a transplant for a MN26 with a median follow-up of 10 months after transplantation. With a relatively high cumulative incidence of NRM at 1 year (44.8%), the main cause of death in the study was infection (3 patients, including COVID-19), and only 2 patients presented with GVHD. This observation was challenged by a retrospective study that compared the post-HSCT outcomes in 161 patients who were tested for germ line predisposition (DDX41 vs CHEK2 vs other predisposition vs patients without predisposing mutations) and reported a significantly higher rate of severe grade 3 to 4 aGVHD (38%) and cGVHD (33%) in the 21 patients with DDX41mut when compared with other groups.18 In our study with a 2-year NRM of 21.1%, we reported lower toxicity than previous studies. Specifically, our severe grade 3 to 4 aGVHD rates were lower (12.7% in patients with AML and 21.1% in patients with MDS) than those observed by Saygin et al18 and in our pair-matched analysis, the aGVHD and cGVHD rates were not higher among patients with DDX41mut than among those with DDX41WT. This may be because of several parameters, the primary one being that our patients predominantly received HSCT in CR1, whereas only 57% of the patients in the Australian cohort were transplanted in CR1. The size of our cohort prevented us from evaluating the effect of PT-Cy (used in 12 patients with DDX41mut), which has been suggested to be associated with lower aGVHD in patients with DDX41mut by Saygin et al.18 Among the patients who received PT-Cy as GVHD prophylaxis, 4 developed aGVHD grade 2 to 4 and 1 experienced grade 3 aGVHD. In the study by Saygin et al18 no patients developed severe aGVHD. This difference may be explained by the higher number of patients in our cohort. As reported by Saygin et al18 no patients in the PT-Cy group died from GVHD.

Our results align with the favorable outcomes observed in a cohort of 151 patients with DDX41-mutated AML, MDS, or Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, among whom 42 received an HSCT. Before transplantation, patients received either azacitidine, a combination of azacitidine and venetoclax, or intensive chemotherapy, alone or in combination with venetoclax. Half of the patients received a MAC regimen, and 61.9% of the patients received an MUD graft. Notably, GVHD prophylaxis consisted of PT-Cy in 71.4% of the patients, however, the study did not evaluate the incidence of aGVHD or cGVHD.6

To our knowledge, there is no previously published study that evaluated the cumulative incidence and kinetics of relapse after HSCT in this specific population. With a 2-year relapse incidence of 10.2% among patients with DDX41mut, we also highlighted a specific late relapse pattern associated with DDX41mut in our pair-matched analysis. Indeed, in our pair-matched analysis, the median time to relapse in the DDX41mut population was 50 months as opposed to 7.5 months among patients with DDX41WT. This observation is consistent with a multicenter retrospective study of 25 patients who experienced very late relapse after HSCT, which reported that the most common genetic mutation found in the leukemic cells was DDX41.27 Focusing on the 11 patients with DDX41mut who relapsed after being transplanted using related donors in our study, we described 7 cases of DCL. In all DCL cases, DDX41mut was detected in donor cells (donor cell chimerism of 100%) with a variant allele frequency that suggested a germ line origin in donor cells, and this was confirmed for 5 donors. To date, DCL has been reported in case reports28,29 in patients with DDX41mut, and systematic testing in all patients with MDS/AML before transplant is not performed in all centers. The DCL rate of 8.4% in this cohort and of 19.4% among the patients who received a transplantation from a related donor highlights the risk associated with related donors in this population. Potential related donors should undergo systematic predictive DDX41mut testing as recommended by the United Kingdom Cancer Genetics Group, CanGene-CanVar, NHS England Genomic Laboratory Hub Haematological Malignancies Working Group, and the British Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation and Cellular Therapy.30

One limitation of this study is its retrospective nature. However, obtaining prospective data on rare germ line myeloid malignancies is challenging, because screening may not be broadly performed. Larger cohorts with longer follow-up are needed to evaluate the impact of different conditioning regimens, donor types, and GVHD prophylaxis regimens in patients with DDX41mut MDS/AML. Another limitation of our study is that patients received HSCT between 2007 and 2022. Although this enabled a long follow-up, we acknowledge that transplantation modalities have changed over this period, especially in terms of improvements in supportive care and GVHD treatments.

Taken together, our results suggest that HSCT is safe in DDX41-related myeloid malignancies. Moreover, with significant follow-up, we did not find post-HSCT secondary malignancies associated with DDX41mut as has been described in other genetic predispositions. In this setting, our study highlights that the post-HSCT outcomes for patients with DDX41mut MDS/AML may be favorable, particularly in terms of a low relapse incidence. Because DDX41 germ line predisposition to MNs is not frequently associated with familial disease and considering this exceptional cohort of DCL cases, we recommend that all patients with MDS/AML who are candidates for HSCT with related donors be screened for DDX41 mutations and that potential related donors (for patients with DDX41mut) undergo genetic testing before donation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the families and individuals for their participation in these studies. The authors also acknowledge the Acute Leukemia French Association, French Innovative Leukemia Organization, Groupe Francophone des myélodysplasies, and Société Francophone de Greffe de moelle et de Thérapie Cellulaire cooperative groups and their investigators.

Authorship

Contribution: M.L. and M.S. designed the study and were involved in all aspects of the project, including acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of study data; J.-E.G. performed statistical analysis; M.L., M.-M.A., S.N., F.S.d.F., M.R., I.Y.-A., E.D., S.C., A.C., D.L., S.M., H.L., A.H., E.F., C.C.-L., T.C., L.A., M. D'aveni, R.D., N.M., S.B., H.D., C.R., A.P., E.D., P.T., R.P.d.L., and M.S. managed patients and provided clinical data; M.-C.V., N.G., A.P., M. Duchmann, L.L., E.C., N.D., and M.S. collected genetic data; M.L., M.-C.V., and M.S. wrote the manuscript; and all authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Michael Loschi, Department of Hematology, University Hospital of Nice, Cote d'Azur University, INSERM U1065, 151 route de Saint Antoine de Ginestiere, 06200 Nice, France; email: loschi.m@chu-nice.fr; and Marie Sébert, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, Hôpital Saint Louis and University of Paris, INSERM U944 and THEMA Institute, 1 Ave Claude Vellefaux, 75010 Paris, France; email: marie.sebert@aphp.fr.

References

Author notes

Data are available on request from the corresponding authors, Michael Loschi (loschi.m@chu-nice.fr) and Marie Sébert (marie.sebert@aphp.fr).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.