Key Points

HLA restriction of a TP VST bank can be determined and annotated using SALs.

Outcomes for patients who had VST products selected on the basis of HLA restriction data are excellent.

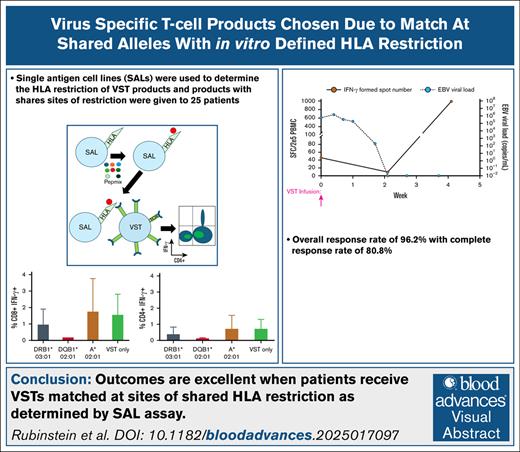

Visual Abstract

Patients with significant T-cell dysfunction from chemotherapy or hematopoietic stem cell transplant are at significant risk for complications of viral infections. Off-the-shelf third-party virus-specific T cells (TP VSTs) are an effective and well-tolerated treatment for the management of infection with adenovirus, BK polyomavirus, cytomegalovirus, and Epstein-Barr virus. TP VST product selection for any particular patient incorporates maximizing the number of HLA matches between the product and the patient, along with consideration of the antiviral activity of the product. We have previously shown that single-antigen cell lines (SALs), cell lines expressing a single HLA molecule, can be used in a flow cytometric-based assay to determine sites of HLA restriction for TP VST products. We hypothesized that incorporating match at sites of HLA restriction into TP VST product selection would improve response rates. Here we report on 25 patients who received TP VSTs for the treatment of 26 viral infections with at least 1 match at an HLA-restricted site. In this cohort, the overall response rate was 96.2%, with a complete response rate of 69.2%. These data suggest the annotation of VST banks to include SAL-derived HLA restriction could lead to improved product selection and efficacy. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT02532452.

Introduction

Acquired T-cell immunodeficiency caused by chemotherapy and/or allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) places patients at substantially increased risk of infection with double-stranded DNA viruses such as adenovirus (ADV), BK polyomavirus (BKV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).1 While supportive care measures continue to improve, these viruses remain an important source of morbidity and mortality.2 There are no effective conventional antiviral therapies for BKV, and those available for ADV, CMV, and EBV have high failure rates and substantial toxicity.3-5

Adoptive transfer of virus-specific T cells (VSTs) manufactured from healthy human donors is a well-established option for the treatment of these viruses.6 VSTs derived from a patient’s specific stem cell donor are highly effective, and offer the benefit of (in many cases) full HLA match.7,8 However, manufacture of donor-derived VSTs is limited to a very small number of transplant centers. Additionally, with an increasing number of patients receiving stem cells from haploidentical donors, there is potential for donor-derived VSTs in these cases to have antiviral activity driven through nonshared alleles. Third-party (TP) VSTs are available as off-the-shelf therapies with minimal lag time, allowing for potentially more widespread adoption.9,10 However, this process requires selection of a partially HLA-matched VST product for each individual patient, often, or perhaps usually, without knowing which alleles present viral-specific peptides.

Many TP VST trials, including published studies from our institution, have prioritized maximizing the number of sites of HLA match in product selection.11,12 HLA restriction is a term reflecting the concept that T cells respond to antigen only when that antigen is processed through specific HLA molecules.13 Therefore, the absolute number of HLA matches may be far less crucial to VST activity than matching the appropriate sites of HLA restriction.

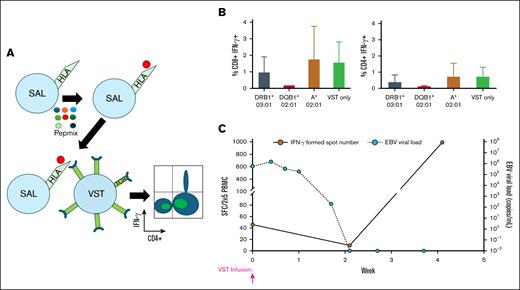

We have previously shown that HLA restriction for a VST product can be determined using single-antigen cell lines (SALs).12 SALs are immortalized cell lines engineered to express a single HLA molecule. These lines can be pulsed with viral antigen mixtures (Pepmixes) to allow for antigenic loading on the solely expressed HLA molecule. These loaded lines can then be cultured in the presence of VSTs, and then subjected to intracellular flow cytometry for interferon gamma (IFN-γ). As the SALs are the only source of antigen presented to the T cells in this system, if IFN-γ is detected then it indicates HLA restriction for that viral peptide. This coculture assay allows the determination of VST response against viral antigen presented on a single HLA. To date, we have evaluated HLA restriction in 35 TP VST products using at least 2 SALs corresponding to evaluation of restriction in at least 2 HLA molecules. Here we report on a cohort of 25 patients whose TP VST products were selected due to at least 1 match between the patient and the product at the site of HLA restriction as determined by the SAL assay.

Methods

VST manufacture and product selection

VSTs were manufactured as previously described, and met all required release criteria.14 In brief, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors were cultured in the presence of ADV, BKV, CMV, and EBV Pepmixes in the presence of interleukin-4 and interleukin-7.

The current study reports on a nonconsecutive cohort of patients who received a TP VST product with at least 1 match at a site of HLA restriction as determined by the SAL assay. Products underwent the HLA restriction assay retrospectively after their initial manufacture and characterization. Upon completion of the assay, annotation of HLA restriction for tested products was added into the product selection algorithm. For any tested allele, response was qualitatively noted as either not restricted (−) or restricted (+). A restricted allele was one in which a distinct CD3+/IFNγ+ population was present that was not seen in the no-SAL negative control, whereas a nonrestricted allele had no appreciable positive population above the negative control background. For restricted alleles, a qualitative score of +, ++, or +++ was assigned, indicating the magnitude of the response, and was based on the discretion of a reviewing investigator. The patients reported in this cohort all had HLA restriction data incorporated into their product selection.

Patient enrollment and clinical trial information

Patients were enrolled on a single-site phase 2 study examining the use of TP VSTs (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02532452). This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and the United States Food and Drug Administration. Key eligibility criteria for enrollment included being immunocompromised with plasma ADV ≥1000 copies per mL, blood CMV ≥500 IU/mL, blood EBV ≥9000 IU/mL, plasma BKV >1000 copies per mL, and/or the presence of invasive infection, symptomatic BK hemorrhagic cystitis, EBV-associated malignancy, or lymphoproliferative process. Invasive disease was supported by the presence of pertinent symptoms, and a positive viral polymerase chain reaction or histologic biopsy. Patients were excluded from the study if they had grade 2 to 4 acute graft-versus-host disease, ongoing chemotherapy treatment, uncontrolled bacterial or fungal infection, and >0.5 mg/kg per day of prednisone equivalent corticosteroids. Patients may not have received alemtuzumab or antithymocyte globulin within 14 days of infusion. Failure of prior antiviral therapy was not required for enrollment. Patients receive a fixed cell dose of 5 × 107 VST per m2. Patients were eligible to receive repeat infusions as frequently as 21 days if the infusions were tolerated and there was ongoing evidence of infection. Due to differences in their degree of immunosuppression and their differential response rates, this analysis excluded VST recipients with a history of solid organ transplant or autoimmune disease.

Response assessment

Patients were evaluated 4 weeks after their VST infusion. Response is reported after the first infusion for patients who received >1 infusion. Complete response (CR) was defined as a decrease in the viral load to below the lower limit of quantitation for the institutional viral assay, whereas a partial response (PR) was defined as a 1-log decrease from baseline viral load for patients treated for viremia. CR was defined as complete resolution of symptoms and/or imaging, and a PR was defined as an improvement in symptoms and/or imaging for patients with tissue disease.

SALs and in vitro estimation of HLA restriction

Immortalized DAP.3, RM3, or K562 cells stably transfected with a single class I or II HLA molecule were previously generated.15-17 Cells were either received directly from the producing laboratories or in a few cases purchased from the Fred Hutchinson International Histocompatibility Working Group. Class II expression was validated in the original draft describing the generation of these products.15 To validate the class I SALs, we stained with an HLA-ABC pan-antibody. Cells were thawed in a water bath, and then cultured in either Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium with 25 mM HEPES (N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-Nʹ-2-ethanesulfonic acid), 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 mM sodium pyruvate, 1% nonessential amino acids, 1% glutamax with/or without 200 μg/mL G418, or Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, 4 mM L-glutamine, 100 mM sodium pyruvate, and 200 μg/mL G418, depending on the cell line. Cells were then seeded at a density of 0.5 × 106 per mL (DAP.3), 2 × 106 per mL (RM3), or 2.5 × 106 per mL (K562) with 0.5 μg/mL of appropriate viral Pepmix. Class II SALs were incubated with Pepmix for 20 hours, while class I were incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. After incubation, cells were washed 3 times with phosphate-buffered saline, and then ∼2.5 × 105 VST cells were added and cocultured for 6 hours. Cells were then harvested, washed with phosphate-buffered saline, and stained with CD3-PE, CD4-APC-eFluor 780, CD8-FITC, and Zombie Violet viability dye. Cells were fixed and permeabilized, and then stained with an antibody against intracellular IFN-γ–APC. Flow cytometry analysis was performed using the MACSQuant Analyzer (Miltenyi Biotec). Each SAL line is also coincubated with a VST product in the absence of viral peptide as a negative control; representative assays showing an absence of reactivity in these conditions are shown in supplemental Figure 1. As the SALs are derived from cell lines that lack natural killer cells and the VST products are CD3 selected, no natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity against the SALs is expected.

ELISpot

IFN-γ Enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISpot) was performed on postinfusion recipient samples as previously described.14 Spot-forming cells (SFCs) were developed using the Human IFN-γ ELISpotPLUS kit (Mabtech, Nacka Strand, Sweden) and quantitated using the Immunospot S6 Analyzer (Cellular Technology Limited, Cleveland, OH). Background SFC counts in the media were subtracted from experimental conditions to determine the reported SFC count.

Results

SAL assay is an effective screening tool for determination of HLA restriction of VST products

A library of 27 SAL products was generated, with an emphasis on common HLA alleles seen in the population of the United States (Table 1). Estimation of HLA restriction was performed on 35 consecutively manufactured VST products that had ≥2 HLA alleles within their haplotypes for which we had a SAL product. VST donor serostatus was known in all cases for CMV and EBV, and restriction was only assessed for those viruses if the donor was seropositive. Serostatus for ADV and BKV was not known, but due to the high prevalence of infection with these viruses in the general public, restriction was assessed for these viruses in all lines. An allele was determined to have restriction if there was detectable CD4+IFN-γ+ cells and/or CD8+IFN-γ+ cells by intracellular flow cytometry, and lacking restriction if there was an absence of these populations.

HLA alleles covered by the SAL library

| A . | B . | DRB1 . | DQB1 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| A∗01:01 | B∗07:02 | DRB1∗01:01 | DQB1∗02:01 |

| A∗02:01 | B∗08:01 | DRB1∗03:01 | DQB1∗03:01 |

| A∗03:01 | B∗14:02 | DRB1∗04:01 | DQB1∗03:02 |

| A∗11:01 | B∗15:01 | DRB1∗07:01 | DQB1∗05:01 |

| A∗24:02 | B∗35:01 | DRB1∗11:01 | DQB1∗06:02 |

| A∗26:02 | B∗39:01 | DRB1∗15:01 | |

| A∗33:03 | B∗44:02 | ||

| B∗44:03 | |||

| B∗60:01 |

| A . | B . | DRB1 . | DQB1 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| A∗01:01 | B∗07:02 | DRB1∗01:01 | DQB1∗02:01 |

| A∗02:01 | B∗08:01 | DRB1∗03:01 | DQB1∗03:01 |

| A∗03:01 | B∗14:02 | DRB1∗04:01 | DQB1∗03:02 |

| A∗11:01 | B∗15:01 | DRB1∗07:01 | DQB1∗05:01 |

| A∗24:02 | B∗35:01 | DRB1∗11:01 | DQB1∗06:02 |

| A∗26:02 | B∗39:01 | DRB1∗15:01 | |

| A∗33:03 | B∗44:02 | ||

| B∗44:03 | |||

| B∗60:01 |

A median of 4 HLA alleles was tested per VST product (range, 2-6). The median number of restricted alleles per VST product, accounting for the fact that each allele was assessed for between 2 and 4 viruses, was 5 (range, 1-14). Accordingly, at least 1 site of restriction was found in all products.

SAL-derived HLA restriction data can be utilized in the selection of VST products for TP infusion

Twenty-five patients received infusions of TP VSTs with match at ≥1 HLA-restricted allele during the study period (May 2022-April 2025). Patient and disease characteristics are shown in Table 2. Twenty-two (88.0%) of the recipients had undergone stem cell transplant, 21 of which were allogeneic. Three patients (12.0%) had acquired T-cell dysfunction from chemotherapeutic treatment of hematologic malignancy, but none was actively receiving chemotherapy at the time of infusion. The median age at transplant was 16 years (range 4 months-70 years) for those who had received HSCT, and the median time from transplant to the infusion of VSTs with SAL data was 118 days (range, 23-425 days).

Characteristics of patients infused with VSTs matching at sites of HLA restrictions

| Characteristic . | Sample size (%) . |

|---|---|

| Biological sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 12 (48.0) |

| Male | 13 (52.0) |

| Reason for immunocompromise, n (%) | |

| HSCT | 22 (88) |

| Oncologic diagnosis without transplant | 3 (12) |

| Median age at HSCT (range) | 16 years (4 months-70 years) |

| Time from transplant to VST (range), d | 118 (23-425) |

| Indication for HSCT, n (%) | |

| Bone marrow failure syndrome | 6 (27.3) |

| Classical hematology | 1 (4.5) |

| Genetic disorder | 1 (4.5) |

| Immunodeficiency | 3 (4.5) |

| Malignancy | 11 (50) |

| Donor source, n (%) | |

| Autologous | 1 (4.5) |

| Cord unit | 1 (4.5) |

| Cord unit + haploidentical donor | 1 (4.5) |

| Haploidentical donor | 8 (36.4) |

| Matched unrelated donor | 8 (36.4) |

| Mismatched unrelated donor | 3 (4.5) |

| GVHD prophylactic regimen, n (%) | |

| Abatacept | 2 (4.5) |

| Calcineurin inhibitor | 17 (38.6) |

| Ex vivo T-cell depletion | 3 (6.8) |

| Posttransplant cyclophosphamide | 5 (11.4) |

| Other (MMF or MTX) | 16 (36.4) |

| Unknown | 1 (2.3) |

| Virus treated, n (%) | |

| ADV | 9 (34.6) |

| BKV | 5 (19.2) |

| CMV | 9 (34.6) |

| EBV | 3 (11.5) |

| Indication for treatment, n (%) | |

| Invasive viral disease | 6 (24.0) |

| Viremia | 17 (68.0) |

| Both | 2 (8.0) |

| Characteristic . | Sample size (%) . |

|---|---|

| Biological sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 12 (48.0) |

| Male | 13 (52.0) |

| Reason for immunocompromise, n (%) | |

| HSCT | 22 (88) |

| Oncologic diagnosis without transplant | 3 (12) |

| Median age at HSCT (range) | 16 years (4 months-70 years) |

| Time from transplant to VST (range), d | 118 (23-425) |

| Indication for HSCT, n (%) | |

| Bone marrow failure syndrome | 6 (27.3) |

| Classical hematology | 1 (4.5) |

| Genetic disorder | 1 (4.5) |

| Immunodeficiency | 3 (4.5) |

| Malignancy | 11 (50) |

| Donor source, n (%) | |

| Autologous | 1 (4.5) |

| Cord unit | 1 (4.5) |

| Cord unit + haploidentical donor | 1 (4.5) |

| Haploidentical donor | 8 (36.4) |

| Matched unrelated donor | 8 (36.4) |

| Mismatched unrelated donor | 3 (4.5) |

| GVHD prophylactic regimen, n (%) | |

| Abatacept | 2 (4.5) |

| Calcineurin inhibitor | 17 (38.6) |

| Ex vivo T-cell depletion | 3 (6.8) |

| Posttransplant cyclophosphamide | 5 (11.4) |

| Other (MMF or MTX) | 16 (36.4) |

| Unknown | 1 (2.3) |

| Virus treated, n (%) | |

| ADV | 9 (34.6) |

| BKV | 5 (19.2) |

| CMV | 9 (34.6) |

| EBV | 3 (11.5) |

| Indication for treatment, n (%) | |

| Invasive viral disease | 6 (24.0) |

| Viremia | 17 (68.0) |

| Both | 2 (8.0) |

GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MTX, methotrexate.

Twenty-six viruses were treated, as 1 recipient had both significant ADV and BKV at the time of infusion. Nine ADV infections (34.6%), 5 BKV infections (19.2%), 9 CMV infections (34.6%), and 3 EBV infections (11.5%) were treated. Seventeen patients (68.0%) were treated for viremia, 6 (24.0%) for invasive viral disease, and 2 (8%) had both active viremia and viral disease (1 with concurrent CMV viremia and CMV pneumonitis, another with ADV viremia and BK hemorrhagic cystitis).

The 25 patients received infusions from 12 different VST products with HLA restriction data (Table 3).

VST products analyzed for HLA restriction by SALs and infused into patients in this cohort

| VST Product ID . | A . | A . | B . | B . | C . | C . | DRB1 . | DRB1 . | DQB1 . | DQB1 . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4184-D115B | 01:01 | 11:01 | 08:01 | 35:02 | 04:01 | 07:01 | 03:01 | 11:04 | 02:01 | 03:01 | ||||||||

| A | + | A | – | A | + | |||||||||||||

| B | – | B | – | B | – | |||||||||||||

| C | NT | C | NT | C | NT | |||||||||||||

| E | + | E | ++ | E | + | |||||||||||||

| 4184-D121B | 01:01 | 30:01 | 08:01 | 15:01 | 03:04 | 07:01 | 03:01 | 07:01 | 02:01 | 02:02 | ||||||||

| A | – | A | – | A | + | |||||||||||||

| B | – | B | – | B | – | |||||||||||||

| C | + | C | + | C | + | |||||||||||||

| E | – | E | – | E | – | |||||||||||||

| 2777-344B | 24:02 | 24:02 | 08:01 | 50:01 | 06:02 | 07:02 | 03:01 | 07:01 | 02:01 | 02:02 | ||||||||

| A | + | A | + | A | + | A | +++ | |||||||||||

| B | + | B | + | B | + | B | + | |||||||||||

| C | + | C | + | C | + | C | + | |||||||||||

| E | + | E | – | E | + | E | – | |||||||||||

| 2777-345B | 01:01 | 26:01 | 08:01 | 27:05 | 01:02 | 07:01 | 01:01 | 03:01 | 02:01 | 05:01 | ||||||||

| A | + | A | – | A | ++ | A | + | |||||||||||

| B | ++ | B | – | B | – | B | + | |||||||||||

| C | NT | C | NT | C | NT | C | NT | |||||||||||

| E | ++ | E | – | E | ++ | E | + | |||||||||||

| 2777-355B | 23:01 | 26:01 | 08:01 | 35:01 | 04:01 | 07:02 | 03:01 | 04:02 | 02:01 | 03:02 | ||||||||

| A | + | A | + | A | – | A | – | A | + | |||||||||

| B | +++ | B | +++ | B | + | B | – | B | + | |||||||||

| C | NT | C | NT | C | NT | C | NT | C | NT | |||||||||

| E | NT | E | NT | E | NT | E | NT | E | NT | |||||||||

| 2777-370B | 02:01 | 03:01 | 14:01 | 44:02 | 05:01 | 08:02 | 07:01 | 11:01 | 02:02 | 03:01 | ||||||||

| A | – | A | – | A | + | |||||||||||||

| B | + | B | + | B | + | |||||||||||||

| C | +++ | C | + | C | ++ | |||||||||||||

| E | + | E | + | E | ++ | |||||||||||||

| 2777-371B | 01:01 | 02:01 | 15:01 | 44:02 | 02:02 | 04:01 | 04:04 | 13:01 | 03:02 | 06:03 | ||||||||

| A | + | A | – | A | + | A | + | |||||||||||

| B | – | B | – | B | – | B | + | |||||||||||

| C | + | C | ++ | C | + | C | + | |||||||||||

| E | – | E | + | E | – | E | + | |||||||||||

| 2777-402B | 01:01 | 11:01 | 15:02 | 44:02 | 05:01 | 08:01 | 12:02 | 15:01 | 03:01 | 06:02 | ||||||||

| A | + | A | ++ | |||||||||||||||

| B | – | B | + | |||||||||||||||

| C | + | C | + | |||||||||||||||

| E | – | E | – | |||||||||||||||

| 2777-404B | 26:01 | 26:01 | 08:01 | 51:01 | 07:02 | 15:02 | 03:01 | 11:01 | 02:01 | 03:01 | ||||||||

| A | + | A | ++ | A | + | A | + | |||||||||||

| B | – | B | – | B | – | B | + | |||||||||||

| C | NT | C | NT | C | NT | C | NT | |||||||||||

| E | NT | E | NT | E | NT | E | NT | |||||||||||

| 2777-419B | 01:01 | 01:01 | 14:01 | 51:01 | 07:01 | 15:02 | 07:01 | 09:01 | 02:02 | 03:03 | ||||||||

| A | – | A | + | |||||||||||||||

| B | – | B | ++ | |||||||||||||||

| C | NT | C | NT | |||||||||||||||

| E | – | E | – | |||||||||||||||

| 2777-423B | 02:01 | 23:01 | 08:01 | 08:01 | 07:02 | 07:02 | 03:01 | 03:01 | 02:01 | 02:01 | ||||||||

| A | – | A | + | A | – | A | + | |||||||||||

| B | – | B | – | B | – | B | + | |||||||||||

| C | ++ | C | ++ | C | + | C | + | |||||||||||

| E | + | E | + | E | + | E | + | |||||||||||

| 2777-437B | 02:01 | 30:02 | 40:06 | 53:01 | 04:01 | 15:02 | 03:01 | 16:02 | 02:01 | 05:02 | ||||||||

| A | – | A | + | A | – | |||||||||||||

| B | – | B | + | B | – | |||||||||||||

| C | + | C | + | C | – | |||||||||||||

| E | + | E | ++ | E | – | |||||||||||||

| VST Product ID . | A . | A . | B . | B . | C . | C . | DRB1 . | DRB1 . | DQB1 . | DQB1 . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4184-D115B | 01:01 | 11:01 | 08:01 | 35:02 | 04:01 | 07:01 | 03:01 | 11:04 | 02:01 | 03:01 | ||||||||

| A | + | A | – | A | + | |||||||||||||

| B | – | B | – | B | – | |||||||||||||

| C | NT | C | NT | C | NT | |||||||||||||

| E | + | E | ++ | E | + | |||||||||||||

| 4184-D121B | 01:01 | 30:01 | 08:01 | 15:01 | 03:04 | 07:01 | 03:01 | 07:01 | 02:01 | 02:02 | ||||||||

| A | – | A | – | A | + | |||||||||||||

| B | – | B | – | B | – | |||||||||||||

| C | + | C | + | C | + | |||||||||||||

| E | – | E | – | E | – | |||||||||||||

| 2777-344B | 24:02 | 24:02 | 08:01 | 50:01 | 06:02 | 07:02 | 03:01 | 07:01 | 02:01 | 02:02 | ||||||||

| A | + | A | + | A | + | A | +++ | |||||||||||

| B | + | B | + | B | + | B | + | |||||||||||

| C | + | C | + | C | + | C | + | |||||||||||

| E | + | E | – | E | + | E | – | |||||||||||

| 2777-345B | 01:01 | 26:01 | 08:01 | 27:05 | 01:02 | 07:01 | 01:01 | 03:01 | 02:01 | 05:01 | ||||||||

| A | + | A | – | A | ++ | A | + | |||||||||||

| B | ++ | B | – | B | – | B | + | |||||||||||

| C | NT | C | NT | C | NT | C | NT | |||||||||||

| E | ++ | E | – | E | ++ | E | + | |||||||||||

| 2777-355B | 23:01 | 26:01 | 08:01 | 35:01 | 04:01 | 07:02 | 03:01 | 04:02 | 02:01 | 03:02 | ||||||||

| A | + | A | + | A | – | A | – | A | + | |||||||||

| B | +++ | B | +++ | B | + | B | – | B | + | |||||||||

| C | NT | C | NT | C | NT | C | NT | C | NT | |||||||||

| E | NT | E | NT | E | NT | E | NT | E | NT | |||||||||

| 2777-370B | 02:01 | 03:01 | 14:01 | 44:02 | 05:01 | 08:02 | 07:01 | 11:01 | 02:02 | 03:01 | ||||||||

| A | – | A | – | A | + | |||||||||||||

| B | + | B | + | B | + | |||||||||||||

| C | +++ | C | + | C | ++ | |||||||||||||

| E | + | E | + | E | ++ | |||||||||||||

| 2777-371B | 01:01 | 02:01 | 15:01 | 44:02 | 02:02 | 04:01 | 04:04 | 13:01 | 03:02 | 06:03 | ||||||||

| A | + | A | – | A | + | A | + | |||||||||||

| B | – | B | – | B | – | B | + | |||||||||||

| C | + | C | ++ | C | + | C | + | |||||||||||

| E | – | E | + | E | – | E | + | |||||||||||

| 2777-402B | 01:01 | 11:01 | 15:02 | 44:02 | 05:01 | 08:01 | 12:02 | 15:01 | 03:01 | 06:02 | ||||||||

| A | + | A | ++ | |||||||||||||||

| B | – | B | + | |||||||||||||||

| C | + | C | + | |||||||||||||||

| E | – | E | – | |||||||||||||||

| 2777-404B | 26:01 | 26:01 | 08:01 | 51:01 | 07:02 | 15:02 | 03:01 | 11:01 | 02:01 | 03:01 | ||||||||

| A | + | A | ++ | A | + | A | + | |||||||||||

| B | – | B | – | B | – | B | + | |||||||||||

| C | NT | C | NT | C | NT | C | NT | |||||||||||

| E | NT | E | NT | E | NT | E | NT | |||||||||||

| 2777-419B | 01:01 | 01:01 | 14:01 | 51:01 | 07:01 | 15:02 | 07:01 | 09:01 | 02:02 | 03:03 | ||||||||

| A | – | A | + | |||||||||||||||

| B | – | B | ++ | |||||||||||||||

| C | NT | C | NT | |||||||||||||||

| E | – | E | – | |||||||||||||||

| 2777-423B | 02:01 | 23:01 | 08:01 | 08:01 | 07:02 | 07:02 | 03:01 | 03:01 | 02:01 | 02:01 | ||||||||

| A | – | A | + | A | – | A | + | |||||||||||

| B | – | B | – | B | – | B | + | |||||||||||

| C | ++ | C | ++ | C | + | C | + | |||||||||||

| E | + | E | + | E | + | E | + | |||||||||||

| 2777-437B | 02:01 | 30:02 | 40:06 | 53:01 | 04:01 | 15:02 | 03:01 | 16:02 | 02:01 | 05:02 | ||||||||

| A | – | A | + | A | – | |||||||||||||

| B | – | B | + | B | – | |||||||||||||

| C | + | C | + | C | – | |||||||||||||

| E | + | E | ++ | E | – | |||||||||||||

The HLA haplotype for each product is listed. Annotation of HLA restriction or lack thereof is indicated for each allele tested by SALs. The presence (+) or absence (−) of HLA restriction for any tested allele is indicated, and based on IFN-γ intracellular flow cytometry at the completion of the assay. For positive alleles, the magnitude was qualitatively graded on a +, ++, +++ scale. NT indicated when the VST donor was seronegative for that respective virus.

A, adenovirus; B, BK virus; E, Epstein-Barr virus; NT, not tested.

Of 25 patients, 23 (92%) were or had very recently received viral directed therapies at the time of VST infusion. One patient did not receive antivirals due to chronic kidney disease, while the other had low-level ADV only.

The date of onset of viremia and/or viral disease was available in 20 of 25 patients. The median time from onset to VST infusion was 33 days. Of note, 5 of 25 patients were primary patients of our transplant center; the median time to infusion for those patients was 9 days, reflecting an institutional preference for early administration of VSTs. The median time to infusion for outside patients was 57 days, reflecting a population that often was highly refractory to conventional antivirals.

Excellent clinical outcomes seen in VST recipients receiving products with match at sites of HLA restriction

Recipients and products matched at a median of 1 HLA-restricted allele (range 1-4), while the median absolute number of matches between recipients and products was 4 (range 2-9).

Clinical outcomes are summarized in Table 4. A CR was seen in 18 of 26 (69.2%) patients. Among the 7 patients with PRs, 6 had clinically relevant decreases in viremia: 1 patient had an ADV viral load decrease from 370 000 000 copies per mL to 7500 copies per mL, 1 had a CMV viral load decrease from 80 430 IU/mL to 997 IU/mL, 1 had an ADV viral load decrease from 84 093 copies per mL to 2087 copies per mL, 1 had a BKV viral load decrease from 18 700 IU/mL to 645 IU/mL, 1 had a CMV viral load decrease from 1813 IU/mL to 109 IU/mL, and 1 had an ADV viral load decrease from 16 000 000 copies per mL to 424 copies per mL. Additionally, the other PR was a patient with CMV retinitis who had improved symptoms following infusion. The overall response rate of 25 of 26 patients (96.2%) is highly clinically relevant.

Clinical outcomes for patients infused with VSTs with shared sites of HLA restriction

| Patient . | Virus treated . | Viral-directed therapy at time of VST . | Time from virus onset to VSTs, d . | Pretreatment disease burden . | Posttreatment disease burden . | Clinical response . | Sites of match . | VST product received . | Sites of match with HLA restriction . | Sites of match without HLA restriction . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 299 | BKV | Cidofovir and nephrostomy tubes | 61 | 18 700 | 645 | PR | 5 | 2777-370B | A∗02:01, DRB1∗07:01 | |

| 310 | BKV | None due to chronic kidney disease | N/A | HC | Resolved HC | CR | 4 | 2777-355B | B∗08:01, DRB1∗03:01, DQB∗03:02 | DQB1∗02:01 |

| 329 | ADV | Cidofovir | 21 | 370 000 000 | 7500 | PR | 4 | 2777-345B | DRB1∗01:01 | B∗08:01 |

| 334 | CMV | Foscarnet | 28 | 80 430 | 997 | PR | 3 | 4184-D121B | A∗01:01 | |

| 344 | CMV | Foscarnet, letermovir, cytogam | N/A | 1466 | <500 | CR | 3 | 2777-344B | A∗24:02 | |

| 356 | EBV | R-CHOP and high-dose methotrexate 1 month prior | 130 | PTLD | Resolution of PTLD by PET | CR | 4 | 2777-344B | A∗24:02 | DRB1∗07:01 |

| 360 | BKV | Foley with bladder irrigation | 105 | 9660 | <21.5 | CR | 3 | 2777-419B | DRB1∗07:01 | A∗01:01 |

| 403 | EBV | Rituximab | 93 | 5250 | 0 | CR | 4 | 4184-D115B | B∗08:01 | |

| 414 | EBV | None | 9 | 564 721 | 0 | CR | 3 | 2777-437B | A∗02:01 | |

| 418 | ADV | Cidofovir | 59 | 84 093 | 2087 | PR | 2 | 2777-344B | DRB1∗07:01 | |

| 422 | CMV | Valganciclovir | N/A | Retinitis | Improved symptoms | PR | 4 | 2777-370B | A∗02:01, DRB1∗07:01 | |

| 423 | CMV | Foscarnet, ganciclovir | 33 | 23 033 | <500 | CR | 3 | 2777-371B | A∗02:01 | |

| 431 | CMV | Foscarnet | 4 | 10 758; pneumonitis | 1838; worsened pneumonitis | NR | 3 | 2777-423B | A∗02:01, B∗0:801 | |

| 437 | ADV, BKV | Cidofovir | 9 | ADV 60 650; BK HC | ADV <500; BK HC resolved | CR, CR | 5 | 4184-D115B | DRB1∗03:01 | B∗08:01 |

| 443 | ADV | None | N/A | 190 | 0 | CR | 4 | 2777-404B | B∗08:01, DRB1∗03:01, DQB1∗02:01 | |

| 446 | ADV | Cidofovir | 55 | 393 | <190 | CR | 4 | 2777-404B | DRB1∗11:01 | |

| 449 | ADV | Cidofovir | 9 | 338 893 | <500 | CR | 9 | 2777-344B | A∗24:02, B∗08:01, DRB1∗03:01. DRB1∗07:01 | |

| 454 | CMV | Intravitreal foscarnet | 65 | Retinitis | Resolution of CMV in aqueous fluid and improved vision | CR | 2 | 2777-423B | A∗02:01 | |

| 455 | BKV | Cidofovir, nephrostomy tubes | 58 | HC | Resolution of HC | CR | 2 | 2777-402B | DRB1∗15:01 | |

| 466 | CMV | Foscarnet | 37 | 1813 | 109 | PR | 3 | 2777-371B | A∗02:01 | |

| 507 | CMV | Ganciclovir (IV and intravitreal), intravitreal foscarnet | ∼5 months | CSF CMV 600 | CSF CMV 0 | CR | 3 | 4184-D121B | A∗01:01, B∗08:01 | |

| 515 | ADV | Cidofovir | 29 | 16 000 000 | 424 | PR | 4 | 4184-D115B | DRB1∗03:01 | |

| 516 | ADV | Cidofovir | N/A | 5100 | <190 | CR | 5 | 4184-D115B | A∗01:01, DRB1∗03:01 | B∗08:01 |

| 524 | ADV | Cidofovir | 32 | Respiratory symptoms | Improved symptoms | CR | 5 | 2777-344B | DRB1∗03:01, DRB1∗07:01 | |

| 560 | CMV | Ganciclovir | 11 | 10 778 | 0 | CR | 5 | 4184-D121B | A∗01:01, B∗08:01 |

| Patient . | Virus treated . | Viral-directed therapy at time of VST . | Time from virus onset to VSTs, d . | Pretreatment disease burden . | Posttreatment disease burden . | Clinical response . | Sites of match . | VST product received . | Sites of match with HLA restriction . | Sites of match without HLA restriction . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 299 | BKV | Cidofovir and nephrostomy tubes | 61 | 18 700 | 645 | PR | 5 | 2777-370B | A∗02:01, DRB1∗07:01 | |

| 310 | BKV | None due to chronic kidney disease | N/A | HC | Resolved HC | CR | 4 | 2777-355B | B∗08:01, DRB1∗03:01, DQB∗03:02 | DQB1∗02:01 |

| 329 | ADV | Cidofovir | 21 | 370 000 000 | 7500 | PR | 4 | 2777-345B | DRB1∗01:01 | B∗08:01 |

| 334 | CMV | Foscarnet | 28 | 80 430 | 997 | PR | 3 | 4184-D121B | A∗01:01 | |

| 344 | CMV | Foscarnet, letermovir, cytogam | N/A | 1466 | <500 | CR | 3 | 2777-344B | A∗24:02 | |

| 356 | EBV | R-CHOP and high-dose methotrexate 1 month prior | 130 | PTLD | Resolution of PTLD by PET | CR | 4 | 2777-344B | A∗24:02 | DRB1∗07:01 |

| 360 | BKV | Foley with bladder irrigation | 105 | 9660 | <21.5 | CR | 3 | 2777-419B | DRB1∗07:01 | A∗01:01 |

| 403 | EBV | Rituximab | 93 | 5250 | 0 | CR | 4 | 4184-D115B | B∗08:01 | |

| 414 | EBV | None | 9 | 564 721 | 0 | CR | 3 | 2777-437B | A∗02:01 | |

| 418 | ADV | Cidofovir | 59 | 84 093 | 2087 | PR | 2 | 2777-344B | DRB1∗07:01 | |

| 422 | CMV | Valganciclovir | N/A | Retinitis | Improved symptoms | PR | 4 | 2777-370B | A∗02:01, DRB1∗07:01 | |

| 423 | CMV | Foscarnet, ganciclovir | 33 | 23 033 | <500 | CR | 3 | 2777-371B | A∗02:01 | |

| 431 | CMV | Foscarnet | 4 | 10 758; pneumonitis | 1838; worsened pneumonitis | NR | 3 | 2777-423B | A∗02:01, B∗0:801 | |

| 437 | ADV, BKV | Cidofovir | 9 | ADV 60 650; BK HC | ADV <500; BK HC resolved | CR, CR | 5 | 4184-D115B | DRB1∗03:01 | B∗08:01 |

| 443 | ADV | None | N/A | 190 | 0 | CR | 4 | 2777-404B | B∗08:01, DRB1∗03:01, DQB1∗02:01 | |

| 446 | ADV | Cidofovir | 55 | 393 | <190 | CR | 4 | 2777-404B | DRB1∗11:01 | |

| 449 | ADV | Cidofovir | 9 | 338 893 | <500 | CR | 9 | 2777-344B | A∗24:02, B∗08:01, DRB1∗03:01. DRB1∗07:01 | |

| 454 | CMV | Intravitreal foscarnet | 65 | Retinitis | Resolution of CMV in aqueous fluid and improved vision | CR | 2 | 2777-423B | A∗02:01 | |

| 455 | BKV | Cidofovir, nephrostomy tubes | 58 | HC | Resolution of HC | CR | 2 | 2777-402B | DRB1∗15:01 | |

| 466 | CMV | Foscarnet | 37 | 1813 | 109 | PR | 3 | 2777-371B | A∗02:01 | |

| 507 | CMV | Ganciclovir (IV and intravitreal), intravitreal foscarnet | ∼5 months | CSF CMV 600 | CSF CMV 0 | CR | 3 | 4184-D121B | A∗01:01, B∗08:01 | |

| 515 | ADV | Cidofovir | 29 | 16 000 000 | 424 | PR | 4 | 4184-D115B | DRB1∗03:01 | |

| 516 | ADV | Cidofovir | N/A | 5100 | <190 | CR | 5 | 4184-D115B | A∗01:01, DRB1∗03:01 | B∗08:01 |

| 524 | ADV | Cidofovir | 32 | Respiratory symptoms | Improved symptoms | CR | 5 | 2777-344B | DRB1∗03:01, DRB1∗07:01 | |

| 560 | CMV | Ganciclovir | 11 | 10 778 | 0 | CR | 5 | 4184-D121B | A∗01:01, B∗08:01 |

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; HC, hemorrhagic cystitis; N/A, not applicable; NR, nonresponse; PET, positron emission tomography; PTLD, posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder; R-CHOP, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone.

Six patients (5 CR, 1 PR) received products in which there were also shared alleles that did not have HLA restriction for the treated virus.

Nonresponse was seen in 1 patient (3.8%). This patient was treated for both CMV viremia and pneumonitis. There was a transient response in viremia, although the viral load quickly rebounded. However, there was no improvement in CMV pneumonitis, and the patient died 43 days after VST infusion of progressive respiratory failure. There was high viral load of CMV in bronchoalveolar lavage and high-resolution chest computed tomography findings consistent with infection; however, because there was no lung biopsy we cannot definitively rule out the possibility of on-target toxicity from the VSTs. This patient matched at 2 sites of HLA restriction, including A∗02:01, which is known to be crucial for CMV control.18

A representative example of SAL data for a VST product with subsequent resolution of viremia in a patient receiving this product is shown in Figure 1.

Representative example of using HLA restriction data derived from SALs to aid in VST selection. (A) Schematic representation of the SAL assay. (B) Bar graphs representing the CD8+IFN-γ+ and CD4+IFN-γ+ cell populations by intracellular flow cytometry after the completion of the SAL assay. These data are for product 2777-437B, which was then given to patient 414. The VST only column indicates VST products cocultured with Pepmix rather than cocultured with Pepmix-loaded SALs. (C) ELISpot data from patient 414 showing increase in EBV-directed T cells in the peripheral blood with a concurrent decrease in viral load.

Representative example of using HLA restriction data derived from SALs to aid in VST selection. (A) Schematic representation of the SAL assay. (B) Bar graphs representing the CD8+IFN-γ+ and CD4+IFN-γ+ cell populations by intracellular flow cytometry after the completion of the SAL assay. These data are for product 2777-437B, which was then given to patient 414. The VST only column indicates VST products cocultured with Pepmix rather than cocultured with Pepmix-loaded SALs. (C) ELISpot data from patient 414 showing increase in EBV-directed T cells in the peripheral blood with a concurrent decrease in viral load.

Seven patients received >1 infusion following their initial treatment with an HLA-restricted line. One patient (356) with posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder was empirically treated with 2 doses, with disease evaluation showing CR occurring after the second infusion. Another patient (344) received 5 additional doses of a different, non-SAL evaluated product for treatment of a different virus. Patient 507 received 6 additional infusions with the same product to aid in the management of CMV retinitis. The other 4 patients (403, 437, 455, 466) each received 1 additional infusion, and responded in all cases.

No patient had an infusion reaction with VSTs, and none developed graft-versus-host disease after infusion.

Expansion of antiviral T cells in peripheral blood after VST infusion

PBMCs were collected at the time of infusion, and then at least weekly for the first 4 weeks after infusion and stored for retrospective analysis. Adequate numbers of stored lymphocytes were available to perform IFN-γ ELISpot to detect antiviral T cells in the peripheral blood of 12 of 25 patients who received VST. Of 12 patients, 10 (83.3%) had CR, and 2 (16.7%) had PR to VSTs.

An increase in antiviral T cells was detected following infusion in 8 of 12 (67%) patients. Of the 4 patients, 2 without an increase in peripheral blood T cells were infused with VSTs for invasive tissue disease rather than viremia, which may explain the lack of increase in the peripheral blood compartment. Of the 2 patients with viremia who did not have an increase in T cells by ELISpot, 1 had a CR and 1 had a robust PR. In the 8 patients with increased T-cell numbers after infusion, the ELISpot frequency increased from a median baseline of 29 SFC/2 × 105 PBMCs (range, 0-202) to a median peak of 51 SFC/2 × 105 PBMCs (range 7-990). A representative example of increasing antiviral T cells in conjunction with decreasing viral load is shown in Figure 1C.

Discussion

In this study we report on 25 highly immunocompromised patients who received TP VSTs for the management of viral infection where there was ≥1 site of match at HLA-restricted alleles as determined by a robust in vitro SAL assay. Previously our selection algorithm prioritized the absolute number of HLA matches along with incorporation of preclinical IFN-γ activity in product choice. Based on these criteria, if no SAL data had been available, then a different VST product would have been selected in 20 of 26 (76.9%) patients.

The overall response rate was excellent at 96.2%, with 69.2% CR rate and highly clinically relevant responses in patients with PR. We previously reported the results of a cohort of 68 TP VST recipients using similar but slightly less stringent response criteria (defined as viral load less than the eligibility criteria for that virus) and found a response rate of 62.7%.19 This is also in line with or higher than other moderate-large trials using TP VSTs that had CR rates ranging from 41% to 94%.11,20-25 We hypothesize that the incorporation of HLA restriction data, which in theory allows for a more precise method for selecting donor products, may be a reason for the high response rate within this cohort.

Of note, there has been a lack of standardization across VST trials with regard to defining response criteria. In this study, we have defined CR as attaining a viral load below the lower limit of quantitation for the assay, in line with United States Food and Drug Administration guidance. However, if we were to use the most stringent response criteria possible (where CR is total resolution rather than just below the lower limit of quantitation), our overall response rate would remain unchanged, although the CR rate would decrease to 46%. This highlights that there can be challenges with interstudy comparisons of small VST studies.

Clinical trials with TP VSTs have varied in their selection criteria for products. Some studies have relied on maximizing HLA match without any knowledge of HLA restriction,11,14 and some do not discuss their algorithm.25 Some mention incorporating HLA restriction into the selection algorithm without further detail on how this is defined.21,22 Trials using the product first generated at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center defined their HLA restriction by assessing VSTs against EBV+ lymphoblastoid cell lines, matching 1 HLA allele that is effective, but also technically challenging and highly time consuming.26,27 We believe the SAL assay, which can be multiplexed and run over 2 days, can allow for a streamlined approach to determine HLA restriction. Accordingly, we now institute prospective SAL testing on all generated VST products where we have SALs for ≥2 HLA alleles.

There was only 1 nonresponding patient in this cohort, who ultimately died of complications of CMV pneumonitis. This patient received a VST product with match at 2 sites of restriction, including the highly immunodominant A∗02:01 allele. This product was also given to a patient with CMV retinitis with match at A∗02:01 who had resolution of CMV in their aqueous fluid, suggesting an active product. We hypothesize that the highly inflammatory infectious process leading to acute respiratory distress syndrome was poorly amenable to VST therapy, and may have led to more rapid clearance of partially matched TP VSTs. Unfortunately, due to critical illness we do not have peripheral blood samples from the nonresponding patient, and therefore cannot investigate the mechanisms behind treatment failure in this case.

We acknowledge that there are limitations within this study. This is a retrospective and single-arm cohort, and the comparator historical cohort is recent, although not concurrent. Additionally, the sample size is relatively small at 25 patients with 26 treated viruses. Finally, this study is not generalizable to all recipients of VSTs, as we focused exclusively on patients who received VSTs after HSCT or other oncologic diagnosis, and not those who received VSTs for inborn errors of immunity, solid organ transplant, or autoimmune disease. However, we believe the results are compelling enough to continue to prospectively analyze all pertinent VST products using SALs, and when feasible to account for HLA restriction in product selection. One additional benefit of defining HLA restriction for the most common HLA alleles within the United States population is that it may enable mini-banks of highly characterized VST products enriched in common haplotypes. This approach could increase the generalizability of TP VST therapy moving forward.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cath Bollard, Michael Keller, and Patrick Hanley for their critical contributions to the establishment of the virus-specific T cell (VST) program at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC). Additionally, the authors thank the staff of the Cellular Therapies Division at Hoxworth Blood Center for their critical aid in managing and manufacturing VSTs and infusions, and the CCHMC Bone Marrow Tissue Repository and the Cell Processing Core laboratories for ongoing technical assistance. Finally, the authors thank the patients and their families for taking part in this study.

This study was performed using divisional funds from the Division of Bone Marrow Transplantation and Immune Deficiency. The research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01HL169242-01A1 (J.D.R.).

Authorship

Contribution: J.D.R., S.M.D., C.L., and M.S.G. designed the study, performed research, and wrote the manuscript; G.P. and A.S. performed functional studies and analysis; D.H. performed virus-specific T cell manufacturing; D.A.L., Z.H., J.W., R.K., Y.M.W., and J.A.C. provided conceptual insights for study design, assisted with study subject accrual and data collection, and prepared scientific support; and all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jeremy D. Rubinstein, Division of Oncology, Cancer and Blood Diseases Institute, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, 3333 Burnet Ave, MLC 7018, Cincinnati, OH 45229; email: jeremy.rubinstein@cchmc.org.

References

Author notes

Original data are available on request from the corresponding author, Jeremy D. Rubinstein (jeremy.rubinstein@cchmc.org).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.