Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT) is a curative option for patients with high-risk malignancies and nonmalignant disorders. Long-term survival depends on robust immune reconstitution (IR), which governs overall immune homeostasis and risks of infection, graft-versus-host disease, and relapse. However, despite its centrality to posttransplant outcomes, IR is not consistently monitored across transplant centers, limiting ability to generate meaningful, comparable, and translatable data. This review synthesizes current knowledge on numerical and functional IR milestones after allo-HCT, with a primary focus on flow cytometry-based monitoring of key immune cell subsets. Importantly, early CD4+ T-cell recovery (achieving >50 cells per μL by day 100 after transplant), is supported by strong clinical evidence and correlates with improved outcomes. Although emerging data suggest that additional subsets (CD8+ T cells, natural killer cells, B cells, naïve and recent thymic emigrant T cells, and γδ T cells) may also influence clinical trajectories, further harmonized, multicenter studies are needed to validate prognostic relevance across transplant settings. We propose practical, evidence-based guidelines for IR monitoring, including recommended time points, preferred assays, and flow cytometry panel components. Additionally, we highlight modifiable factors (eg, immunosuppressive drug exposures, graft manipulation) offering interventional opportunities for influencing IR. Harmonized monitoring strategies will support robust correlation between IR and clinical outcomes, guide real-time risk stratification, and facilitate the development of targeted, individualized transplant approaches. Standardization efforts led by consortia and registries are essential for advancing knowledge and optimizing care. We provide a roadmap for implementing uniform IR monitoring to improve outcomes and quality of life for allo-HCT recipients.

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT) is often the only curative treatment option for patients with high-risk hematologic malignancies and various inherited nonmalignant disorders.

The reconstitution of a fully functional hematopoietic and immune system after conditioning and hematopoietic cell graft infusion is essential for long-term survival, because it mitigates the risk of infections, graft rejection, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), and eradicates malignant disease.1,2 The immune system shapes posttransplant outcomes, influencing key processes including engraftment, host tolerance, pathogen clearance, commensal regulation, tissue repair, metabolism, and wound healing.3 Achieving these functions ensures homeostasis, and requires the balanced, integrated, and coordinated function of multiple components of the innate and adaptive immune systems.

Well-defined and harmonized standards for monitoring immune reconstitution (IR), particularly lymphocyte recovery, represent an unmet need but are essential for the establishment of internationally standardized numerical and functional thresholds of immune recovery. Harmonization will enable better correlation of IR with clinical outcomes and undoubtedly create opportunities for incorporating evidence-based IR end points into observational and interventional studies, improving real-time individual prognostication and risk stratification. Moreover, elucidating mechanisms that govern IR will facilitate optimization of transplant preparative regimens, graft engineering, adoptive cell therapies, use of immunosuppression, supportive care, and social reintegration practices, to yield optimal IR, ultimately enhancing event-free survival, overall survival (OS), and quality of life.

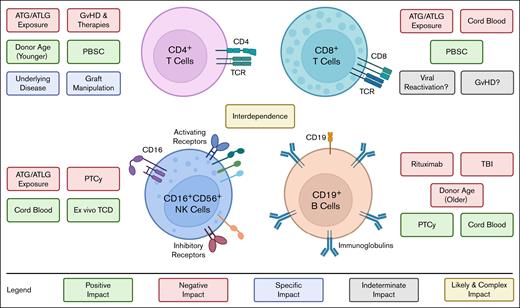

Several heterogeneous pre- and post-HCT factors, some modifiable, others not, clearly influence IR kinetics (Figure 1). These stem from the diverse nature of underlying diseases, recipient and donor/graft characteristics, and transplant-related medications and supportive care. These factors might differentially influence recovery of immune cell subsets (Figure 2). Recovery of the innate and adaptive immune system and its dependency on thymic regeneration proceeds in a recognizable pattern (Figure 1). Harmonizing how transplant centers monitor IR will provide a rapid expansion of current knowledge of all these aspects.

Global overview of post-HCT IR, pre- and post-HCT factors affecting IR and proposed strategies to optimize IR assessment. Pre-HCT factors affecting IR: IR kinetics are influenced by several modifiable and nonmodifiable factors, including the intensity and type of conditioning regimens; cell dose; graft composition; cell source (BM, PBSC, CB); degree and loci of HLA disparity; graft manipulation (eg, ex vivo or in vivo TCD); donor/recipient pairing; donor/recipient age; preparative regimens and drugs/serotherapy used for GVHD prophylaxis (including interindividual variability of pharmacogenomics, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics). Expanding tailored approaches beyond model-based dosing of ATG4-8 to other key variables, such as conditioning intensity, graft composition, and immune suppression strategies, could further optimize IR and improve transplant outcomes.4-8 Post-HCT factors affecting IR: after transplantation, several factors affect IR. Drugs used for GVHD prophylaxis or therapy, GVHD incidence, infections and viral reactivations can each negatively affect IR. Potential strategies to promote post-HCT IR may include adoptive cell therapies and immunotherapy or regenerative approaches. Immune cell compartments and reconstitution: initially, innate immune cells (blue) recover, followed by cells of the adaptive immune system (green). Posttransplant lymphocyte IR is posited to occur in 2 phases9,10: the earliest is a thymus-independent peripheral expansion (pink) of infused graft lymphocytes responding to host homeostatic cytokines.11 This is followed by a delayed, thymus-dependent, “regenerative” phase (orange) occurring months to years after HCT, wherein marrow-derived lymphocyte precursors mature to naïve T cells in the thymus. Thymopoiesis gives rise to a polyclonal TCR repertoire that confers full tolerance to host antigens. Strategies for harmonization, integration, analysis, and expected outcomes: development of shared standard operating procedures, flow cytometric antibody panels, and harmonization of timing of analysis, allows data comparison from different centers, integration in large databases, and potential applications of innovative machine learning/artificial intelligence tools. Together this effort will allow to establish functional thresholds for IR for stratification of patients and clinical management. AI, artificial intelligence; cAUC, cumulative area under the curve; CB, cord blood; CIBMTR, Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research, EBMT, European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation; ML, machine learning; PBSC, peripheral blood stem cell; TBI, total body irradiation.

Global overview of post-HCT IR, pre- and post-HCT factors affecting IR and proposed strategies to optimize IR assessment. Pre-HCT factors affecting IR: IR kinetics are influenced by several modifiable and nonmodifiable factors, including the intensity and type of conditioning regimens; cell dose; graft composition; cell source (BM, PBSC, CB); degree and loci of HLA disparity; graft manipulation (eg, ex vivo or in vivo TCD); donor/recipient pairing; donor/recipient age; preparative regimens and drugs/serotherapy used for GVHD prophylaxis (including interindividual variability of pharmacogenomics, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics). Expanding tailored approaches beyond model-based dosing of ATG4-8 to other key variables, such as conditioning intensity, graft composition, and immune suppression strategies, could further optimize IR and improve transplant outcomes.4-8 Post-HCT factors affecting IR: after transplantation, several factors affect IR. Drugs used for GVHD prophylaxis or therapy, GVHD incidence, infections and viral reactivations can each negatively affect IR. Potential strategies to promote post-HCT IR may include adoptive cell therapies and immunotherapy or regenerative approaches. Immune cell compartments and reconstitution: initially, innate immune cells (blue) recover, followed by cells of the adaptive immune system (green). Posttransplant lymphocyte IR is posited to occur in 2 phases9,10: the earliest is a thymus-independent peripheral expansion (pink) of infused graft lymphocytes responding to host homeostatic cytokines.11 This is followed by a delayed, thymus-dependent, “regenerative” phase (orange) occurring months to years after HCT, wherein marrow-derived lymphocyte precursors mature to naïve T cells in the thymus. Thymopoiesis gives rise to a polyclonal TCR repertoire that confers full tolerance to host antigens. Strategies for harmonization, integration, analysis, and expected outcomes: development of shared standard operating procedures, flow cytometric antibody panels, and harmonization of timing of analysis, allows data comparison from different centers, integration in large databases, and potential applications of innovative machine learning/artificial intelligence tools. Together this effort will allow to establish functional thresholds for IR for stratification of patients and clinical management. AI, artificial intelligence; cAUC, cumulative area under the curve; CB, cord blood; CIBMTR, Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research, EBMT, European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation; ML, machine learning; PBSC, peripheral blood stem cell; TBI, total body irradiation.

Immune recovery of the main cell subsets is positively or negatively influenced by different pre- and post-HCT factors and the subsets are interconnected. Recovery of CD4+ T cells is negatively affected by excessive exposure to ATG/ATLG and by immune suppressive GVHD therapies. Conversely, young donor age and use of PBSC as source for HCT hasten CD4+ T-cell recovery. Specific graft manipulations and underlying diseases can variably augment or hinder CD4+ T-cell IR. ATG/ATLG also impairs CD8+ T-cell recovery, along with using CB as a graft source,12 likely due to the naivety of CB CD8+ T cells. The use of PBSC may hasten recovery of CD8+ T-cell IR. The impact of viral reactivations and GVHD remains to be fully characterized. Although higher numbers of CD8+ T cells may offer protection against viral reactivation, this may also indicate an already active antiviral response and/or alloimmunity.13 As for GVHD, the correlation with CD8+ counts is also not established but in some studies increased CD8+ T-cell counts were observed in patients who have ongoing aGVHD1 or cGVHD.12,14 ATG/ATLG exposure or use of PTCy can delay recovery of NK cells, whereas use of CB or ex vivo TCD promotes early NK cell recovery.15-18 In 1 retrospective cohort study of 499 patients, median numbers of NK cells at 1 month after HCT were reduced after PTCy (20 cells per μL), when compared with ATLG (79-113 cells per μL) or neither PTCy nor ATLG (210 cells per μL). These differences failed to persist after 2 months after HCT.18 Older recipient age has been associated with poorer B-cell IR, as well as use of rituximab, or TBI, which can lead to long-term B-cell defects characterized by lower naïve B cells and switched memory B cells for up to 2 years after HCT.19,20 B-cell IR is faster after HCT with CB or after PTCy. Several studies indicate an interconnection among recovery of different lymphocyte subsets that needs better characterization.13,21 ATLG, anti–T lymphoglobulin; CB, cord blood; PBSC, peripheral blood stem cell; TBI, total body irradiation.

Immune recovery of the main cell subsets is positively or negatively influenced by different pre- and post-HCT factors and the subsets are interconnected. Recovery of CD4+ T cells is negatively affected by excessive exposure to ATG/ATLG and by immune suppressive GVHD therapies. Conversely, young donor age and use of PBSC as source for HCT hasten CD4+ T-cell recovery. Specific graft manipulations and underlying diseases can variably augment or hinder CD4+ T-cell IR. ATG/ATLG also impairs CD8+ T-cell recovery, along with using CB as a graft source,12 likely due to the naivety of CB CD8+ T cells. The use of PBSC may hasten recovery of CD8+ T-cell IR. The impact of viral reactivations and GVHD remains to be fully characterized. Although higher numbers of CD8+ T cells may offer protection against viral reactivation, this may also indicate an already active antiviral response and/or alloimmunity.13 As for GVHD, the correlation with CD8+ counts is also not established but in some studies increased CD8+ T-cell counts were observed in patients who have ongoing aGVHD1 or cGVHD.12,14 ATG/ATLG exposure or use of PTCy can delay recovery of NK cells, whereas use of CB or ex vivo TCD promotes early NK cell recovery.15-18 In 1 retrospective cohort study of 499 patients, median numbers of NK cells at 1 month after HCT were reduced after PTCy (20 cells per μL), when compared with ATLG (79-113 cells per μL) or neither PTCy nor ATLG (210 cells per μL). These differences failed to persist after 2 months after HCT.18 Older recipient age has been associated with poorer B-cell IR, as well as use of rituximab, or TBI, which can lead to long-term B-cell defects characterized by lower naïve B cells and switched memory B cells for up to 2 years after HCT.19,20 B-cell IR is faster after HCT with CB or after PTCy. Several studies indicate an interconnection among recovery of different lymphocyte subsets that needs better characterization.13,21 ATLG, anti–T lymphoglobulin; CB, cord blood; PBSC, peripheral blood stem cell; TBI, total body irradiation.

We review current best evidence, state-of-the-art monitoring approaches, and key challenges for determining IR milestones after allo-HCT. Specifically, we address principal findings regarding the most well-studied immune cell subsets and recommend practical, evidence-based guidelines for transplant centers worldwide to prospectively harmonize post-HCT IR monitoring across transplant disease characteristics, treatment intensity and toxicity, including time points or milestones, when applicable. This consensus review and the final recommendations were established through advanced written discussions and in-person deliberations during the annual meeting of the Westhafen Intercontinental Group (a scientific consortium that includes members representing the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research, European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, Pediatric Disease Working Party, International BFM (Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster), Children’s Oncology Group, and Pediatric Transplantation and Cellular Therapy Consortium), held 28 to 29 March 2025.

Best supported clinical evidence for IR

Flow-cytometry for immune cell phenotyping and quantification is readily available at transplant centers. Here, we present the various immune cell subsets that have been studied most thoroughly to date and offer rationale and recommendations for harmonizing their monitoring.

CD4+ T lymphocytes

CD4+ (helper) T cells are crucial for controlled and effective immune responses to pathogens. Low numbers of CD4+ T cells early after transplantation are linked to a higher incidence of complications and decreased survival.2,22-25 Historically, a CD4+ T-cell count of <200 cells per μL, derived from experiences managing patients with HIV, has been used to risk stratify patients with increased risk of opportunistic infections, and remains a relevant milestone for determining duration of infection prophylaxis after HCT.26

There is increasing evidence that the pace of T-cell reconstitution is modifiable and, as such, improving the reliability with which HCT recipients achieve early T-cell reconstitution is a priority. Conditioning regimen type and intensity and GVHD prophylaxis represent opportunities to enhance CD4+ IR.27-29 Serotherapy, administered to minimize graft rejection and GVHD, affects CD4+ T-cell recovery.30 Several population pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies show that high pretransplant exposure to rabbit antithymocyte globulin (rATG) is associated with decreased incidence of graft rejection and GVHD, whereas residual posttransplant rATG exposure is associated with delayed CD4+ IR and increased nonrelapsed mortality (NRM).4,31,32 Weight-based dosing of rATG yields variable exposure,31,33 because rATG is mainly cleared through “target-mediated clearance” predicted by absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) in patients with weights of >40 kg. Prospective studies using “model-based dosing” of rATG, incorporating recipient weight and ALC, results in better CD4+ IR, decreased NRM, and increased OS.4-6 Similarly, increased anti–T lymphoglobulin exposure delays CD4+ T-cell reconstitution.7 Clearance of alemtuzumab is also likely affected by ALC and body weight,34 and ongoing efforts are developing similar population pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic models.35-37 Fludarabine overexposure with standard body surface area–based dosing also results in delayed CD4+ T-cell IR,38 supporting a hypothesis that model-based dosing of fludarabine may prove beneficial.

Early CD4+ T-cell IR may represent either a causative factor or surrogate marker for acquiring regulatory function that prevents immune-related complications of HCT. Contemporaneous data from multiple studies consistently show that achieving a milestone CD4+ T-cell count of >50 cells per μL within 100 days after allo-HCT (across different transplant platforms and ages) is associated with a fourfold to fivefold reduced cumulative incidence of NRM and, in some studies, a lower risk of acute myeloid leukemia relapse (Table 1).5,8,13,21,31,39-43 Patients who reach this milestone have threefold to fourfold lower NRM from adenovirus reactivations.43 Among patients with acute GVHD (aGVHD), this milestone is associated with better survival,41 although the influence of CD4+ count on treatment responses is still unclear. Higher CD4+ T cells by day 100 was also associated with a threefold lower cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD (cGVHD).6,21 These findings collectively underscore the importance of implementing strategies to predict CD4+ T-cell count after allo-HCT to facilitate clinical decision-making.

Overview of the impact of CD4 levels on HCT outcomes in children and adults

| Reference . | Platform . | Adult/pediatric . | Outcome . | NRM by CD4+ . | No. of patients . | Type of study . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admiraal et al6 | BM, PBSC, CB | Pediatric, young adult | Model-based dosing is associated with 90% CD4+ > 50 prior to day +100 and lower NRM in patients receiving ATG | >50: 5-y TRM 8% <50: 5-y TRM 34% | 214, multicenter | Retrospective, prospective |

| Lakkaraja et al39 | Ex vivo TCD | Pediatric, young adult | >50 CD4+ before day +100 improves TRM | >50: 5-y NRM 4% <50: 5-y NRM 31% | 180, single center | Retrospective |

| Barriga et al40 | BM, PBSC, CB | Pediatric | >50 CD4+ before day +100 improves TRM | >50: 2-y NRM 2.7% <50: 2-y NRM 22.2% | 101, single center | Prospective |

| Huang et al13 | PBSC (haplo-identical and HLA matched) | Adult | >50 CD4+ before day +100 associated with lower risk for EBV and CMV reactivation | NA | 122, single center | Retrospective |

| Troullioud Lucas et al21 | BM, PBSC, ex vivo TCD, CB | Pediatric, young adult | >50 CD4+ before day +100 improves outcomes >25 CD19+ before day +100 reduces NRM | NA | 503, multicenter | Retrospective |

| Admiraal et al5 | BM, CB | Pediatric | >50 CD4+ before day +100 improves TRM | >50: 2-y TRM 7% <50: 2-y TRM 43% | 58, single center | Prospective |

| Lakkaraja et al8 | Ex vivo TCD | Adult/pediatric | >50 CD4+ before day +100 improves NRM | >50: 5-y NRM 5% <50: 5-y NRM 36% | 554, single center | Retrospective |

| De Koning et al41 | BM, PBSC, in vitro TCD, CB | Pediatric | >50 CD4+ before day +100 improves OS and NRM after moderate to severe aGVHD | In patients with grade 3-4 aGVHD >50: 2-y NRM 30% <50: 2-y NRM 80% | 591, multicenter | Retrospective |

| Van Roessel et al42 | BM, PBSC, ex vivo TCD, CB | Pediatric, young adult | >50 CD4+ before day +100 is associated with improved survival | >50: 5-y NRM 3.2% <50: 5-y NRM 28.8% | 315, single center | Retrospective |

| Admiraal et al43 | BM, PBSC, CB | Pediatric | >50 CD4+ T cells associated with fewer viral reactivations | NA | 273, single center | Retrospective |

| Reference . | Platform . | Adult/pediatric . | Outcome . | NRM by CD4+ . | No. of patients . | Type of study . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admiraal et al6 | BM, PBSC, CB | Pediatric, young adult | Model-based dosing is associated with 90% CD4+ > 50 prior to day +100 and lower NRM in patients receiving ATG | >50: 5-y TRM 8% <50: 5-y TRM 34% | 214, multicenter | Retrospective, prospective |

| Lakkaraja et al39 | Ex vivo TCD | Pediatric, young adult | >50 CD4+ before day +100 improves TRM | >50: 5-y NRM 4% <50: 5-y NRM 31% | 180, single center | Retrospective |

| Barriga et al40 | BM, PBSC, CB | Pediatric | >50 CD4+ before day +100 improves TRM | >50: 2-y NRM 2.7% <50: 2-y NRM 22.2% | 101, single center | Prospective |

| Huang et al13 | PBSC (haplo-identical and HLA matched) | Adult | >50 CD4+ before day +100 associated with lower risk for EBV and CMV reactivation | NA | 122, single center | Retrospective |

| Troullioud Lucas et al21 | BM, PBSC, ex vivo TCD, CB | Pediatric, young adult | >50 CD4+ before day +100 improves outcomes >25 CD19+ before day +100 reduces NRM | NA | 503, multicenter | Retrospective |

| Admiraal et al5 | BM, CB | Pediatric | >50 CD4+ before day +100 improves TRM | >50: 2-y TRM 7% <50: 2-y TRM 43% | 58, single center | Prospective |

| Lakkaraja et al8 | Ex vivo TCD | Adult/pediatric | >50 CD4+ before day +100 improves NRM | >50: 5-y NRM 5% <50: 5-y NRM 36% | 554, single center | Retrospective |

| De Koning et al41 | BM, PBSC, in vitro TCD, CB | Pediatric | >50 CD4+ before day +100 improves OS and NRM after moderate to severe aGVHD | In patients with grade 3-4 aGVHD >50: 2-y NRM 30% <50: 2-y NRM 80% | 591, multicenter | Retrospective |

| Van Roessel et al42 | BM, PBSC, ex vivo TCD, CB | Pediatric, young adult | >50 CD4+ before day +100 is associated with improved survival | >50: 5-y NRM 3.2% <50: 5-y NRM 28.8% | 315, single center | Retrospective |

| Admiraal et al43 | BM, PBSC, CB | Pediatric | >50 CD4+ T cells associated with fewer viral reactivations | NA | 273, single center | Retrospective |

CB, cord blood; CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; NA, not available; PBSC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; TRM, transplant-related mortality.

There is robust evidence that early, sustained achievement of CD4+ IR of >50 cells per μL by 100 days after allo-HCT is associated with improved outcomes, including fewer viral reactivations and lower incidence of viral disease, lower NRM, improved survival in patients with aGVHD, less cGVHD, and subsequently better OS. Transplant approaches should be continuously refined to enhance early CD4+ IR.

CD8+ T lymphocytes

CD8+ T cells have cytotoxic function, essential for responding to viral, fungal, and mycobacterial infections, and mediating the graft-versus-malignancy effect. CD8+ T cells tend to recover early after HCT, perhaps through proliferative responses to early antigenic stimuli (eg, viral reactivations, recipient alloreactivity).44,45 This phenomenon of expansion and contraction may explain why the correlation of CD8+ T-cell recovery with post-HCT outcomes is less robust, as shown by various analyses (Table 2), underlining the limitations of using CD8+ IR as a measure for clinical decision-making after HCT and highlighting the interplay of many factors (Figure 2).14,21,43,46-49 Interestingly, in several studies, CD8+ T cells correlated better with relapse rates than other cell subsets but without differences in OS and disease-free survival.46,48

Overview of the impact of CD8 levels on HCT outcomes in children and adults

| Reference . | Platform . | Adult/pediatric . | Outcome . | No. of patients . | Type of study . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yakoub-Agha et al46 | Unmanipulated BMT and PBSC | Adult, pediatric | CD28neg CD8+ T cells < 179 cells per μL at day 60 associated with higher cumulative incidence of relapse | 80, single center | Prospective |

| Tian et al47 | Unmanipulated haplo | Adult, pediatric | ≥375 cells per μL at day 90 reduced infections, improved NRM, LFS, and OS | 214, single center | Prospective |

| Ranti et al48 | BMT, PBSC | Adult | >50 CD8+ T cells per μL reduces relapse incidence. No effect on OS, DFS. | 120, single center | Retrospective |

| Bondanza et al49 | Haplo (unmanipulated, CD34+, TCD) | Adult, pediatric | <20 CD8+ T cells per μL reduces OS and increases NRM | 144, multicenter | Retrospective |

| Troullioud Lucas et al21 | All | Pediatric, young adult | No association found between CD8+ T-cell IR and outcomes | 503, multicenter | Retrospective |

| Huang et al13 | All | Adult, young adult | In pts with early CD4+ T-cell recovery (>50/μL by day 100), higher CD8+ is associated with reduced EBV reactivation | 122, single center | Retrospective |

| Belinovski et al44 | All | Pediatric | On 180 day CI of CMV infection higher for patients CD3+CD8+ of ≥200/μL on day +100. | 111, single center | Retrospective |

| Soares et al14 | MUD | Adult | Early increase in CD8+ T-cell subsets in patients who later develop cGVHD | 40, single center | Prospective |

| Ando et al12 | All | Adult | Higher CD8+ T cells on day +100 reduces NRM;higher activated CD8+ T cells on day +100 increases cGVHD | 358, single center | Retrospective |

| Reference . | Platform . | Adult/pediatric . | Outcome . | No. of patients . | Type of study . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yakoub-Agha et al46 | Unmanipulated BMT and PBSC | Adult, pediatric | CD28neg CD8+ T cells < 179 cells per μL at day 60 associated with higher cumulative incidence of relapse | 80, single center | Prospective |

| Tian et al47 | Unmanipulated haplo | Adult, pediatric | ≥375 cells per μL at day 90 reduced infections, improved NRM, LFS, and OS | 214, single center | Prospective |

| Ranti et al48 | BMT, PBSC | Adult | >50 CD8+ T cells per μL reduces relapse incidence. No effect on OS, DFS. | 120, single center | Retrospective |

| Bondanza et al49 | Haplo (unmanipulated, CD34+, TCD) | Adult, pediatric | <20 CD8+ T cells per μL reduces OS and increases NRM | 144, multicenter | Retrospective |

| Troullioud Lucas et al21 | All | Pediatric, young adult | No association found between CD8+ T-cell IR and outcomes | 503, multicenter | Retrospective |

| Huang et al13 | All | Adult, young adult | In pts with early CD4+ T-cell recovery (>50/μL by day 100), higher CD8+ is associated with reduced EBV reactivation | 122, single center | Retrospective |

| Belinovski et al44 | All | Pediatric | On 180 day CI of CMV infection higher for patients CD3+CD8+ of ≥200/μL on day +100. | 111, single center | Retrospective |

| Soares et al14 | MUD | Adult | Early increase in CD8+ T-cell subsets in patients who later develop cGVHD | 40, single center | Prospective |

| Ando et al12 | All | Adult | Higher CD8+ T cells on day +100 reduces NRM;higher activated CD8+ T cells on day +100 increases cGVHD | 358, single center | Retrospective |

BMT, BM transplantation; CI, cumulative incidence; CMV, cytomegalovirus; DFS, disease-free survival; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; haplo, haploidentical transplant; LFS, leukemia-free survival; MUD, matched unrelated donor; PBSC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; pts, patients.

The interconnectivity of immune recovery is highlighted by a retrospective study demonstrating that CD8+ T-cell recovery to ≥375 cells per μL on day 90 was associated with faster CD4+ T-cell and CD19+ B-cell recovery.47 Accordingly, the CD4:CD8 T-cell ratio may provide an additional milestone of IR, once both subsets are sufficiently recovered. In healthy individuals, the ratio is >1. Patients who have received transplantation typically have a lower ratio due to initial expansion of CD8+ T cells relative to CD4+ T cells (particularly with bone marrow [BM] and peripheral blood stem cell grafts). In some studies, a decreased CD4:CD8 T-cell ratio has been associated with GVHD50; however, data are too limited to support its use in clinical decision-making. Despite the emerging ability to monitor of virus-specific CD8+ T-cell responses, insufficient data are available to affect clinical decision-making.

Data on CD8+ T-cell reconstitution suggest that this subset is more dynamic, making it challenging to establish milestones of CD8+ T-cell reconstitution and validate correlation with outcome measures. Further studies are needed to ascertain this.

NK cells

Natural killer (NK) cells (CD3−CD56+) are cytotoxic innate lymphoid cells constituting the first line of defense against virally infected and cancerous cells and are the first lymphocytes that arise in the periphery after allo-HCT. These are further divided into an immature subset with immunomodulatory function (CD56brightCD16−) and a mature cytotoxic subset (CD56dimCD16++).51 CD56brightCD16− NK cells differentiate early after HCT from infused donor CD34+ progenitors and contribute to antiviral and leukemia defense, whereas reconstitution of CD56dimCD16++ NK cells occurs months later.15,52-54 In cord blood grafts, CD56brightCD16− NK cells reach normal numbers by 3 months after HCT.55 Unlike PBSC and BM transplants, a compensatory overexpansion of NK cells occurs early after cord blood transplant that may contribute to additional graft-versus-leukemia effects.56-58

Although post-HCT NK cell IR has been extensively studied, a definitive threshold that predicts outcome differences is still lacking, possibly due to the high impact of transplant-related factors on NK reconstitution (Figure 2). NK cell recovery occurs faster, and earlier sampling may be needed to find associations with transplant outcomes. As for GVHD prophylaxis, posttransplant cyclophosphamide (PTCy) yields the most severe initial depletion of NK cells15-18 when compared with ex vivo T-cell depletion (TCD),59-61 or with prophylaxis based on anti–T lymphoglobulin.18 Early after ex vivo TCD HCT (CD3−/CD19−, αβ T-cell receptor [αβTCR]–/CD19-depleted, or CD34-selected graft), remaining NK cells are the predominant lymphocyte subset that expands in vivo in response to homeostatic cytokines (ie, interleukin-15).59-62

Several studies (Table 3) have associated prompt recovery of NK cells with improved outcome (survival, relapse rate), both in T cell–replete and TCD HCT,53,63-68 whereas a recent retrospective, multicenter study showed no correlation between NK cell IR and survival.21

Overview of the impact of NK cell levels on HCT outcomes in children and adults

| Reference . | Platform . | Adult/pediatric . | Outcome . | No. patients . | Type of study . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mushtaq et al53 | All | Adult, pediatrics | Higher early NK cell number improves 2-year OS | 1785 patients from 21 studies. Reconstitution | Meta-analysis |

| Minculescu et al63 | T-cell replete | Adult | >150 NK cells per μL at day +30 improves OS | 298, single center | Retrospective |

| Troullioud Lucas et al21 | All | Pediatric, young adults | No association found between NK cell IR and outcomes | 503, multicenter | Retrospective |

| Cui et al464 | T-cell replete | Pediatric | >111 NK cells per μL at day +30 improves NRM | 122, single center | Retrospective |

| McCurdy et al65 | Haplo PTCy vs MSD/MUD | Adult | >50.5 cells per μL at day +28 improves OS and PFS | 145, single center | Prospective |

| Nguyen et al66 | CB, RIC | Adult | Higher CD16+ NK reduce TRM | 79, multicenter | Prospective |

| Kim et al67 | All | Adult | Lower (206.4 cells per mL vs 310.1 cells per μL) at day +30 and 90 days (147.6 cells per μL vs 403.0 cells per mL) associated with increased aGVHD. NKof >177 cells per μL at day +30 improves OS and PFS | 70, single center | Retrospective |

| Cui et al64 | All | Pediatric | NK of >111 cells per μL at day +30 and higher counts at day +60 improves 3-y OS, reduces RFS and NRM and aGVHD | 122, single center | Prospective |

| De Koning et al69 | T-cell repleted | Pediatric | Positive correlation between innate immunity and CD4+ T-cell recovery (either monocytes of >0.89 × 109/L and/or neutrophils >4.2 × 109/L and/or NK cells of >0.34 × 109/L within day +50) | 205, single center | Retrospective |

| Troullioud Lucas et al21 | BM, PBSC, ex vivo TCD, CB | Pediatric, young adult | No correlation between NK and survival | 503, multicenter | Retrospective |

| Reference . | Platform . | Adult/pediatric . | Outcome . | No. patients . | Type of study . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mushtaq et al53 | All | Adult, pediatrics | Higher early NK cell number improves 2-year OS | 1785 patients from 21 studies. Reconstitution | Meta-analysis |

| Minculescu et al63 | T-cell replete | Adult | >150 NK cells per μL at day +30 improves OS | 298, single center | Retrospective |

| Troullioud Lucas et al21 | All | Pediatric, young adults | No association found between NK cell IR and outcomes | 503, multicenter | Retrospective |

| Cui et al464 | T-cell replete | Pediatric | >111 NK cells per μL at day +30 improves NRM | 122, single center | Retrospective |

| McCurdy et al65 | Haplo PTCy vs MSD/MUD | Adult | >50.5 cells per μL at day +28 improves OS and PFS | 145, single center | Prospective |

| Nguyen et al66 | CB, RIC | Adult | Higher CD16+ NK reduce TRM | 79, multicenter | Prospective |

| Kim et al67 | All | Adult | Lower (206.4 cells per mL vs 310.1 cells per μL) at day +30 and 90 days (147.6 cells per μL vs 403.0 cells per mL) associated with increased aGVHD. NKof >177 cells per μL at day +30 improves OS and PFS | 70, single center | Retrospective |

| Cui et al64 | All | Pediatric | NK of >111 cells per μL at day +30 and higher counts at day +60 improves 3-y OS, reduces RFS and NRM and aGVHD | 122, single center | Prospective |

| De Koning et al69 | T-cell repleted | Pediatric | Positive correlation between innate immunity and CD4+ T-cell recovery (either monocytes of >0.89 × 109/L and/or neutrophils >4.2 × 109/L and/or NK cells of >0.34 × 109/L within day +50) | 205, single center | Retrospective |

| Troullioud Lucas et al21 | BM, PBSC, ex vivo TCD, CB | Pediatric, young adult | No correlation between NK and survival | 503, multicenter | Retrospective |

haplo, haploidentical transplant; MSD, matched sibling donor; MUD, matched unrelated donor; PFS, progression-free survival; RFS, relapse-free survivale; RIC, reduced intensity conditioning regimen.

Finally, reconstitution of innate immunity should be evaluated together with adaptive immunity given their high interconnectedness. For instance, early innate cell recovery (monocytes, neutrophils, and NK cells) is associated with increased CD4+ T-cell count by day 100.69 This association may relate to the proliferative capacity (fitness) of infused cells, stem cell content, and/or engraftment efficiency, and needs further delineation.

NK cell reconstitution may protect from adverse events early after HCT. It is advisable to further investigate and develop reference ranges for early protective NK cell IR across different HCT platforms, because this factor alone drives discrepant data about whether NK cell IR affects prognosis.

B lymphocytes

B-cell recovery occurs later than other lymphocyte subsets, with CD19+ B cells arising at 1.5 to 2 months after HCT and reaching normal levels at ∼1 year.19,70 However, numeric recovery of B cells does not always correspond with functional recovery and some patients, including those with recovery of normal numbers of total CD19+ B cells, have long-term antibody deficiencies, with 15% of patients requiring γ-globulin supplementation at 1 year.70 Recovery of B-cell function can be monitored by recovery of mature, switched memory B-cell populations as well as functional assays described hereafter. Many patients with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia receive pre- and/or post-HCT targeted therapies (eg, chimeric antigen receptor T cells, rituximab, blinatumomab, and inotuzumab ozogamicin).71 The use of rituximab can lead to long-term B-cell defects, characterized by lower naïve B cells and switched memory B cells after HCT.19,20 Further studies are needed detailing how these different therapies affect post-HCT B-cell IR.

Relatively scant data exist tying numerical B-cell IR to outcomes (Table 4), although they may indicate a positive correlation with OS and NRM.12,20 Importantly, some studies highlight an interconnection between early B-cell and CD4+ T-cell recovery that influences outcomes.21,70 This emphasizes the importance of closely monitoring B-cell reconstitution starting early after HCT. However, further studies are necessary to determine whether B-cell IR is a surrogate for improved BM recovery or if there is a mechanistic explanation for these results.

Overview of the impact of B-cell levels on HCT outcomes in children and adults

| Reference . | Platform . | Adult/pediatric . | Outcome . | No. patients . | Type of study . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ando et al12 | All | Adult | CD20+ mature B-cell recovery at day 100 improves OS and NRM | 358, single center | Retrospective |

| Zhou et al20 | All | Adult | B-cell reconstitution at 3 and 12 mo improves OS | 252, single center | Retrospective |

| Abdel-Azim et al70 | All | Pediatric | Switched memory B-cell recovery is correlated to CD4+ T-cell recovery at 6 mo | 71, single center | Retrospective |

| Troullioud Lucas et al21 | BM, PBSC, ex vivo TCD, CB | Pediatric, young adult | B-cell count of 25 cells per μL reduces NRM. Combined with CD4 of >50 cells per μL reduces NRM, aGVHD, cGVHD, and AML relapse | 503, multicenter | Retrospective |

| Reference . | Platform . | Adult/pediatric . | Outcome . | No. patients . | Type of study . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ando et al12 | All | Adult | CD20+ mature B-cell recovery at day 100 improves OS and NRM | 358, single center | Retrospective |

| Zhou et al20 | All | Adult | B-cell reconstitution at 3 and 12 mo improves OS | 252, single center | Retrospective |

| Abdel-Azim et al70 | All | Pediatric | Switched memory B-cell recovery is correlated to CD4+ T-cell recovery at 6 mo | 71, single center | Retrospective |

| Troullioud Lucas et al21 | BM, PBSC, ex vivo TCD, CB | Pediatric, young adult | B-cell count of 25 cells per μL reduces NRM. Combined with CD4 of >50 cells per μL reduces NRM, aGVHD, cGVHD, and AML relapse | 503, multicenter | Retrospective |

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CB, cord blood; PBSC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell.

B-cell reconstitution is associated with outcomes (OS, NRM) in certain settings, and periodic assessment of CD19+ B cells should be routinely conducted after HCT. Additional studies must be conducted to establish whether B-cell reconstitution, along with the interaction of B cells with other lymphocyte subsets, correlates with immunoglobulin levels and patient outcomes.

γδ T cells

γδ T–cell IR also plays a role in early immune defense and tumor surveillance. Unlike conventional αβ T cells, γδ T cells exhibit both adaptive and innate-like immune responses. These cells constitute up to 10% of peripheral T cells in healthy individuals and recognize tumor cells independently of HLA presentation, enabling rapid and broad cytotoxic activity against acute leukemia.72 However, no specific threshold of γδ T–cell reconstitution has been established that correlates with outcome.

The impact of different transplant-related factors on γδ T–cell reconstitution is less clear.73 In recent years, post-HCT γδ T–cell IR has been predominantly studied in the context of αβ-TCD haploidentical transplantation in which they rapidly expand from infused cells several weeks before αβ T cells expand and predominate.74,75 In the context of αβ-TCD HCT, patients who achieved >10% vs <10% γδ T cells between 60 and 270 days after HCT had increased disease-free survival (90% vs 31%).76 In a single-center study on 102 pediatric patients, patients with ≥150 γδ T cells per μL had a reduced incidence of infections and improved event-free survival (91% vs 55%).77 The role of γδ T cells and its subsets in GVHD remains controversial and needs to be further studied.

γδ T cells appear to play an early role in IR and leukemia control, particularly in the setting of αβ T–/CD19 B-cell–depleted haplo-HCT. However, more investigational studies are needed to establish the impact of these subsets on outcomes, the kinetics of reconstitution in different transplant settings, and potential need for clinical monitoring.

Thymic reconstitution: naïve T cells and RTEs

Recovery of thymopoiesis is indispensable for generating naïve T cells, allowing for an expanded T-cell repertoire. Thymic reconstitution thus (1) establishes operational tolerance that prevents de novo GVHD and autoimmunity through positive and negative selection of T cells and generation of T regulatory cells (Tregs); and (2) further aids in overcoming reactivation of endogenous viral infections and clearing de novo infections.

There is cross talk between developing T cells and thymic epithelial cells critical for T-cell development.78 Recent thymic emigrants (RTEs; CD45RA+CD27+CD62L+CD31+CD38++HLA-DR−) are naïve T cells that undergo the final steps of maturation in the periphery.79 Thymic output can alternatively be assessed molecularly by measuring TCR excision circles (TRECs).80 Although testing for TRECs is routinely used for newborn screening for severe combined immune deficiency, correlation with thymopoesis is confounded by peripheral proliferation of naïve T cells.81 TREC content in peripheral blood mononuclear cells strongly correlates with RTE measurement by flow cytometry.82 Monitoring of RTEs and/or TRECs provides a useful predictive marker of survival from severe viral infections,83,84 GVHD,83,85 NRM,84,86 and OS.84,86-89

A later biomarker of thymic output measures TCR repertoire diversity. Next-generation sequencing assesses the number and diversity of Vβ and γδ TCR clonotypes,90 a marker that signifies the completion of thymic reconstitution, ensuring immune tolerance, an optimal graft-versus-malignancy effect, and a fully restored ability to fight infections.1

Further research should be directed to apply flow cytometry for monitoring of RTEs and naïve T cells, confirm correlation with TRECs, and establish reference standards with the goal of clinically assessing adequacy of T-cell neogenesis alongside CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell reconstitution.

Tregs

Tregs, defined by CD4+CD25+CD127lowFoxP3+ expression, are essential for immune homeostasis and preventing autoimmunity by enforcing peripheral tolerance and regulating responses to self and foreign antigens.91-93 They suppress activation, proliferation, and cytokine production by T cells, B cells, NK cells, and antigen-presenting cells through mechanisms including secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines, metabolic disruption of effector T cells, cytolysis, and modulation of dendritic cell function via CTLA4-mediated downregulation of costimulatory molecules.94-96

After HCT, Treg reconstitution begins with homeostatic peripheral expansion followed by contribution from thymopoiesis.97,98 Treg proportions among CD4+ T cells typically normalize by 6 weeks after HCT across graft sources, with variable function due to GVHD, immunosuppression, and delayed thymic recovery.99-102 Similarly to CD4+ T cells, serotherapy delays Treg recovery,103 whereas PTCy spares Tregs and supports their rapid recovery.104

Low, early post-HCT Treg numbers or ratios to conventional T cells have been linked to increased incidence and severity of grade 2 to 4 aGVHD, higher GVHD-related NRM, and lower OS,105-107 and correlate with increased GVHD-related NRM and decreased OS.106 PTCy-based prophylaxis reduces rates of aGVHD and cGVHD without affecting graft-versus-leukemia effects, supporting a role for Treg reconstitution in mitigating GVHD.108 Treg expansion has also been noted during GVHD, although the functional relevance of this remains unclear.109

Tregs appear to play a role in mitigating GVHD, particularly in the setting of PTCy use. Further studies are needed to characterize their normal reconstitution kinetics early in transplant and after recovery of thymopoiesis, and to establish reference standards with the goal of assessment alongside conventional T-cell IR.

Investigational studies of functional IR

Although flow cytometry offers valuable information on immune cell numbers, assays of immune function help to characterize the quality of IR after HCT. Here, we examine existing data on immune functional assays that have been studied during the posttransplant period.

Monitoring functional recovery of innate immunity

NK cell cytolysis and cytokine production

NK cell proliferation, immunomodulatory cytokine secretion, and cytolytic activity correlate with immunophenotype.110 Cytokine-producing and cytolytic activities are acquired by NK cell “licensing” via complex interaction between self-specific killer immunoglobulin-like receptors and HLA class I.111 Cytolytic activity, measured by degranulation of NK cells after coculture with K562 erythroleukemia cell line, along with production of interferon gamma and other cytokines, is delayed after HCT for ∼3 to 6 months.110 Graft T-cell content, systemic immunosuppression, presence of GVHD, and cytomegalovirus reactivation all affect this timeline.52,110,112 Higher production of tumor necrosis factor α and interferon gamma by NK cells at 1 month after HCT has been associated with improved OS and reduced relapse rate.68

Further research may explore developing standardized, reproducible, and validated protocols for cytolytic activity and cytokine release to monitor functional NK cell recovery and correlating these functions with posttransplant outcomes.

Monitoring functional recovery of adaptive immunity

T lymphocyte cytokine and proliferative responses

T-cell proliferation can be assessed in response to nonspecific mitogens (most commonly phytohemagglutinin)113 or T cell–specific mitogens such as anti-CD3 and anti-CD28, alone or in combination. Such assays may inform diagnosis of severe combined immune deficiency and portend late effects and mortality after allo-HCT.114 Assay quality is highly variable and strongly affected by low, absent, and/or non-T/dysfunctional T cells. T-cell proliferation has also been assessed in response to specific antigens (most commonly tetanus and candida).115

Encouragingly, more contemporary flow cytometry–based protocols that simultaneously measure cell numbers, proliferation, and cytokine release after antigen stimulation (eg, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus) have been developed.116 These methods might be broadly applied in multicenter settings, so they are likely to supplant previous methods.113 Functional assays may be affected by incomplete numerical T-cell reconstitution, with an adequate threshold still to be determined.

Although methods to assess T-cell cytokine production and proliferation in response to mitogens, antigens, and viruses have been described, further research efforts may target development and standardization of flow cytometry–based protocols for lymphocyte cytokine release and proliferation to enable broader application in the clinical setting.

B lymphocyte function

Numerous surrogate markers signify functional B-cell IR. Recovery of immunoglobulin levels parallels numerical B-cell reconstitution (particularly of mature naïve B cells) and mimics normal human B-cell ontogeny, beginning with class switch to immunoglobulin M (IgM).70 The emergence of IgM isohemagglutinins to the A and B blood group antigens in a titer of ≥1:8 signifies onset of specific antibody production.117 IgG levels recover after IgM, signifying that supportive γ-globulin administration may be discontinued when IgG levels are consistently >400 mg/dL (or potentially higher for patients with inborn errors of immunity). γ-globulin independence therefore represents a readily obtainable surrogate marker of functional B-cell reconstitution.118 IgG recovery is followed by IgA recovery much later. Serum immunoglobulin levels, particularly in combination with absolute numbers of CD4+ T cells, have been demonstrated to predict adequate antibody titer responses to polysaccharide and influenza vaccination.119-121 Establishment of humoral immunity can be further confirmed by adequate vaccine responses to polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccines (ie, pneumococcal, haemophilus B vaccination [Hib], and meningococcal) and influenza vaccine.122

Monitoring of clinical γ-globulin dependence and IgM, IgA, and IgG, and isohemagglutinin switch may be routinely applied to assess functional B-cell IR, potentially in conjunction with vaccine titer responses, rather than flow cytometry. Harmonizing these measures is complicated by divergent practices around γ-globulin supplementation and vaccination.

Strategies for harmonization and monitoring timeline

In Figure 3 and Table 5, we summarize our quality of evidence, preferred assays, and endorsed intervals and/or milestones for measurement, together with the strength of recommendation. Specifically, early assessment of the main immune cell populations, beginning 1 month after HCT, should be performed. At these early time points, CD8+ T-cell and NK cell IR predominate, whereas CD4+ T-cell IR follows by day 100. We suggest continuing to monitor monthly until 3 months after HCT, unless the patient displays sufficient IR (ie, CD4+ T cells of >200 cells per μL), is without signs of GVHD, and off immunosuppression, allowing suspension of anti-infective prophylaxis and routine viral monitoring. Notably, patients requiring ongoing treatment for GVHD need close monitoring at least monthly while immune suppression is ongoing. After 3 months, it is important to continue to periodically assess IR for up to 24 months after HCT or until full recovery of immune function. For practical reasons, the minimum follow-up may coincide with time points for underlying disease and late effects follow-up. Additionally, centers may adopt more frequent IR monitoring schedules in the context of research studies.

Summary of recommendations for monitoring of post-HCT IR. (A) Recommended monitoring for clinical purposes: we recommend monitoring of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, NK cells, and B cells, with corresponding time points. Recommended periodic assessment of IgG production until IVIG independence is reached. (B) Additional monitoring for research purposes: several additional T-cell subsets can be monitored in the context of research studies. It is generally advisable to monitor CD4+ T-cell subsets when the total number of CD4+ T cells exceeds 200/μL. It is also possible to monitor TCR diversity by next-generation sequencing. Finally, it is possible to perform functional assays to evaluate NK cell cytolytic function and cytokine production or to evaluate T-cell proliferative capacity and cytokine response. (C) Additional tests can be performed in clinical setting but are not routinely recommended due to lack of evidence and/or standardized methods. See Table 5 for further details on our recommendations. DTaP, ditpheria tetanus acellular pertussis vaccination; Hib, haemophilus B vaccination; IVIG, IV immunoglobulins; PCV, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

Summary of recommendations for monitoring of post-HCT IR. (A) Recommended monitoring for clinical purposes: we recommend monitoring of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, NK cells, and B cells, with corresponding time points. Recommended periodic assessment of IgG production until IVIG independence is reached. (B) Additional monitoring for research purposes: several additional T-cell subsets can be monitored in the context of research studies. It is generally advisable to monitor CD4+ T-cell subsets when the total number of CD4+ T cells exceeds 200/μL. It is also possible to monitor TCR diversity by next-generation sequencing. Finally, it is possible to perform functional assays to evaluate NK cell cytolytic function and cytokine production or to evaluate T-cell proliferative capacity and cytokine response. (C) Additional tests can be performed in clinical setting but are not routinely recommended due to lack of evidence and/or standardized methods. See Table 5 for further details on our recommendations. DTaP, ditpheria tetanus acellular pertussis vaccination; Hib, haemophilus B vaccination; IVIG, IV immunoglobulins; PCV, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

Summary table of evidence and recommendations for IR monitoring and harmonization

| Immune system component or function . | Prognostic outcome: overall quality of evidence∗,†,‡ . | Preferred assay . | Recommended intervals or milestones for assay§ . | Strength of recommendationǁ (application)¶ . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS . | TRM/NRM . | DFS/EFS/RFS . | aGVHD . | cGVHD . | VR . | ||||

| CD4+ T cells | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | Flow cytometry | IAt months: 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24 | A (clinical) |

| CD8+ T cells | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | B (clinical) | ||

| CD19+ B cells | 2 | 2 | — | 2 | 2 | — | B (clinical) | ||

| CD56+CD16-/+ NK cells | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | — | 2 | B (clinical) | ||

| RTEs, naïve T cells, TRECs | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Flow cytometry (sequencing) | MWith CD4 T-cell reconstitution (CD4 of >200 cells per μL), until normal | B (research) |

| Treg cells | 2 | 2 | — | 2 | 2 | — | Flow cytometry | MWith CD4 T-cell reconstitution (CD4 of >200 cells per μL), until normal | B (research) |

| γδ T cells | — | — | 2 | — | — | — | Flow cytometry | Not established | C (research) |

| Vaccine response | — | — | — | — | — | — | Antibody titers | MAfter revaccination | C (clinical) |

| Isohemagglutinin switch | — | — | — | — | — | — | Serological titer | MWith B-cell reconstitution (>25-50 cells per μL), stop at detection | C (clinical) |

| IgG production | — | — | — | — | — | — | Quantitative immunoturbidimetry | IEvery 2-4 weeks until IVIG independence | C (clinical) |

| IgM and IgA production | — | — | — | — | — | — | Quantitative immunoturbidimetry | MWith B-cell reconstitution (>25-50 cells per μL), until normal | C (clinical) |

| NK cytolysis and cytokine production | 2 | 3 | 3 | — | — | — | Chromium release assay, flow cytometry | MWith NK cell reconstitution and off immunosuppression, until normal | C (research) |

| T-cell proliferative and cytokine responses | 2 | — | — | — | — | 3 | Flow cytometry | MWith T-cell reconstitution (CD4 of >200 cells per μL) and off immunosuppression, until normal | C (research) |

| TCR diversity | — | — | 3 | — | — | 3 | Next-generation sequencing | MWith evidence of thymopoiesis (by RTEs/TRECs), until normal | NR (research) |

| Immune system component or function . | Prognostic outcome: overall quality of evidence∗,†,‡ . | Preferred assay . | Recommended intervals or milestones for assay§ . | Strength of recommendationǁ (application)¶ . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS . | TRM/NRM . | DFS/EFS/RFS . | aGVHD . | cGVHD . | VR . | ||||

| CD4+ T cells | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | Flow cytometry | IAt months: 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24 | A (clinical) |

| CD8+ T cells | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | B (clinical) | ||

| CD19+ B cells | 2 | 2 | — | 2 | 2 | — | B (clinical) | ||

| CD56+CD16-/+ NK cells | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | — | 2 | B (clinical) | ||

| RTEs, naïve T cells, TRECs | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Flow cytometry (sequencing) | MWith CD4 T-cell reconstitution (CD4 of >200 cells per μL), until normal | B (research) |

| Treg cells | 2 | 2 | — | 2 | 2 | — | Flow cytometry | MWith CD4 T-cell reconstitution (CD4 of >200 cells per μL), until normal | B (research) |

| γδ T cells | — | — | 2 | — | — | — | Flow cytometry | Not established | C (research) |

| Vaccine response | — | — | — | — | — | — | Antibody titers | MAfter revaccination | C (clinical) |

| Isohemagglutinin switch | — | — | — | — | — | — | Serological titer | MWith B-cell reconstitution (>25-50 cells per μL), stop at detection | C (clinical) |

| IgG production | — | — | — | — | — | — | Quantitative immunoturbidimetry | IEvery 2-4 weeks until IVIG independence | C (clinical) |

| IgM and IgA production | — | — | — | — | — | — | Quantitative immunoturbidimetry | MWith B-cell reconstitution (>25-50 cells per μL), until normal | C (clinical) |

| NK cytolysis and cytokine production | 2 | 3 | 3 | — | — | — | Chromium release assay, flow cytometry | MWith NK cell reconstitution and off immunosuppression, until normal | C (research) |

| T-cell proliferative and cytokine responses | 2 | — | — | — | — | 3 | Flow cytometry | MWith T-cell reconstitution (CD4 of >200 cells per μL) and off immunosuppression, until normal | C (research) |

| TCR diversity | — | — | 3 | — | — | 3 | Next-generation sequencing | MWith evidence of thymopoiesis (by RTEs/TRECs), until normal | NR (research) |

DFS, disease-free survival; EFS, event-free survival; NR, not recommended; VR, viral reactivations.

Taxonomy adopted from Ebell et al.123

Good quality (level 1): systematic review/meta-analysis of good-quality cohort studies; or prospective cohort study with good follow-up.

Limited quality (level 2): systematic review/meta-analysis of lower-quality cohort studies or with inconsistent results; or retrospective cohort study or prospective cohort study with poor follow-up; or case-control study; or case series.

Other evidence (level 3): consensus guidelines; extrapolations from bench research; usual practice; opinion; disease-oriented evidence (intermediate or physiological outcomes only); or case series for studies of diagnosis, treatment, prevention, or screening.

I, intervals to perform regular measurement; M, milestone to achieve before first measurement, then regularly at serial time points (eg, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 mo).

A, recommendation based on consistent and good-quality patient-oriented evidence; B, recommendation based on inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence; C, recommendation based on consensus, usual practice, disease-oriented evidence, case series for studies of screening, and/or opinion; NR, no recommendation.

Clinical: readily performed in most clinical settings; Research: readily performed in centralized, clinical, and/or research laboratories, not sufficiently validated for widespread use.

Importantly, the adopted flow cytometry antibody panel must include all the main lymphocyte lineage markers (CD3, CD4, CD8, CD16, CD56, and CD19). Because the clinical impact of other subsets, such as RTEs or Tregs, is less clear, centers may include additional markers (eg, CD45RO/RA, CD62L, CD27, CD31) for research purposes, refinement, and eventual integration into clinical practice. Currently, data comparability across centers are extremely limited due to the heterogeneity of the panels and procedures used. Sharing the core antibody panel (clones and fluorochromes) is advisable to maximize the comparability of results among centers. Ideally, complete standardization among transplantation centers worldwide would lead to direct comparability and aggregation of all acquired data. The use of commercially available preset tubes ensures a high degree of standardization. Harmonization, involving the sharing of key steps rather than the whole procedure, offers an alternative approach that is easier to achieve and can be considered as a first step in obtaining comparable data.79,124 To improve comparability, centers should share common standard operating procedures for noncommercial flow cytometric panels to minimize technical variability. Harmonization or standardization across different centers is therefore crucial for advancing the discipline.

Discussion

We summarize the most current evidence and practical approaches regarding monitoring reconstitution of innate and adaptive immunity after allo-HCT. Harmonizing how and when to monitor different lymphocyte subsets (in a multicenter setting) will lead to collective knowledge that helps identify patients at risk of inferior outcomes and enrich evidence on the impact of different allo-HCT strategies on IR. Immunophenotyping by flow cytometry is widely available in most transplant centers, making it an ideal platform to catalyze this harmonization. We also discuss functional measures of IR and highlight areas in which research is needed to develop guidelines for their clinical use. Modifiable factors influencing IR should be thoroughly examined. For instance, drug exposures in preparative regimens for allo-HCT can be adjusted with alternative or synergistic approaches (eg, model-based dosing) to optimize the IR milieu and improve multiple outcomes and quality of life. Recipient age also represents an important biological determinant of immune recovery, particularly with respect to thymopoietic recovery, that has potentially distinct clinical implications for pediatric, young adult, and older patients. When possible, we have highlighted research that specifically separates or combines these populations, and our recommendations are expected to further inform targeted care for each age group.

There is robust, consistent evidence that achieving CD4+ T cells of >50 cells per μL within 100 days after HCT is associated with multiple improved outcomes after allo-HCT. More preliminary data suggest the likely clinical relevance of other CD4+ T-cell subsets (eg, naïve T cells and RTEs), CD8+ T cells, B cells, NK cells, and γδ T cells, although further harmonized monitoring strategies and higher quality data are needed to determine clinical recommendations as with CD4+ T cells. Additionally, detailed, systematic evaluation of the interplay between elements of innate and adaptive IR will inform future clinical recommendations. Currently, there is an unmet need to develop standardized, reproducible protocols for monitoring functional markers of innate and adaptive IR for prospective studies of clinical utility before definitive recommendations can be made.

Available evidence supports refining clinical practice guidelines based on routine monitoring the numerical reconstitution of lymphocyte subsets (Figure 3; Table 5). At present, evidence supports the discontinuation of infection prophylaxis once CD4+ T-cell IR exceeds 200 cells per μL and all immunosuppression is stopped. Conceivably, achieving a milestone of CD4+ T-cell IR of >50 cells per μL by day 100 after HCT (associated with transplant-related mortality of <5%), could be evaluated prospectively to inform risk-adapted approaches for managing infection prophylaxis, treatment of viral reactivations, GVHD prophylaxis and therapies, and isolation and supportive care practices. Further expansion and refinement of these guidelines will be better informed by incorporating best evidence from harmonizing comprehensive IR monitoring practices across centers.

In recent decades, several international consortia (eg, Associazione Italiana di Onco-Ematologia Pediatrica-Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster Study Group, Children’s Oncology Group, EuroFlow Consortium, Minimum Information about a Flow Cytometry Experiment guidelines by International Society for the Advancement of Cytometry) have been working to reduce interlaboratory variation (particularly in the field of leukemia diagnostics), and this has proven to be a complex task.125-127 In the field of HCT, international societies and registries (particularly the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research and European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation) should foster harmonization for measurement and reporting of post-HCT IR. Additionally, specific efforts could be made within prospective clinical trials that require the participating centers to align IR monitoring procedures. These efforts are particularly prudent for generating large IR databases for analysis using advanced computational approaches, especially machine learning and artificial intelligence, and thus vastly advance our knowledge.

Conclusion

Current evidence strongly supports the relationship between IR and HCT outcomes. Notably, early reconstitution of CD4+ T cells has been shown to improve outcomes. Further prospective investigation may support the prognostic impact of CD8+ T-cell, B-cell, and NK cell reconstitution. Evidence indicates the need for regular monitoring of IR by flow cytometry until completion and development of host tolerance, especially during the first 6 months after HCT.

Limitations of current knowledge in the field reflect the limitations of studies of post-HCT IR. Firstly, large, prospective, multicenter, systematic data collection (eg, from registries) is lacking and would facilitate a more robust association of IR with transplant outcomes. Secondly, evidence concerning the clinical relevance of many lymphocyte subsets (eg, naïve T cells, RTEs, γδ T cells) remains limited and needs prospective evaluation to establish the impact on HCT complications and recovery. Additionally, significant interest exists regarding the implications of lymphocyte subset chimerism on IR, and this warrants further investigation to inform clinical practice.

This work paves the way for implementing strategies to harmonize monitoring of IR, allowing systematic and parallel collection, sharing, and direct comparison of large datasets across transplant centers and in registries. Such a collaborative effort from consortia and individual centers will undoubtedly rapidly advance the field to improve outcomes for our patients.

Acknowledgments

A.G.T.L. and J.J.B. acknowledge support from National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center support grant P30 CA008748.

Authorship

Contribution: T.H., S.N., A.G.T.L., M.R.V., and J.J.B. contributed to the conception, design, and interpretation of the study; T.H., S.N., and A.G.T.L. wrote the initial manuscript draft, supervised by M.R.V. and J.J.B.; and all authors contributed to critically revising the manuscript for important intellectual content and provided final approval of the submitted version.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.J.B. reports honoraria from Avrobio, BlueRock, bluebird bio, Sanofi, Sobi, SmartImmune, and Advanced Clinical Consulting. R.M. reports honoraria for consulting or advisory role from Bellicum Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Vertex, Medac, Celgene/Bristol Myers Squibb, and bluebird bio. H.P. reports advisory roles with Vertex and Novartis. S.E.P. reports support for the conduct of clinical trials through Boston Children’s Hospital from Atara and Jasper; is an inventor of intellectual property related to development of third party viral-specific T-cell program with all rights assigned to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; reports consulting roles with Atara Biotherapeutics, Ensomo, HEOR, Mesoblast, Pierre Fabre, and VOR Bio; serves on data and safety monitoring boards for Stanford University and New York Blood Center; and holds equity interest in Regatta Biotherapies. N.N.S. states that the content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views of policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government; is supported by the Intramural Research Program, Center of Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute and National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health (ZIA BC 011823); reports research funding from Lentigen, VOR Bio, and Cargo Therapeutics; has attended advisory board meetings (no honoraria) for VOR, ImmunoACT, and Sobi; and reports royalties from Cargo. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

A complete list of the members of the Westhafen Intercontinental Group appears in “Appendix.”

Correspondence: Jaap Jan Boelens, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Stem Cell Transplant and Cellular Therapy, 1275 York Ave, New York, NY 10065; email: boelensj@mskcc.org; and Michael R. Verneris, CU Anschutz School of Medicine, Department of Pediatrics and Children's Hospital of Colorado, Center for Cancer and Blood Disorders. Research Complex 1, North Tower, 12800 E 19th Ave, Mail Stop 8302, Room P18-4108, Aurora, CO 80045; email: michael.verneris@cuanschutz.edu.

Appendix

Westhafen Intercontinental Group is a scientific consortium that includes Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR), European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT), Pediatric Disease Working Party (PDWP), I-BFM, Children’s Oncology Group (COG), and Pediatric Transplantation and Cellular Therapy Consortium (PCTCT).

References

Author notes

T.H., S.N., and A.G.T.L. contributed equally to this study.

M.V. and J.J.B. contributed equally to this study.