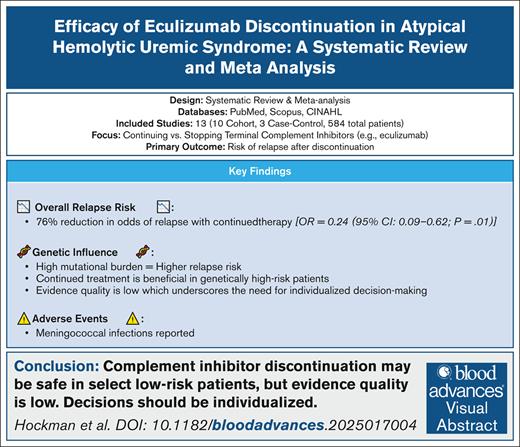

Visual Abstract

Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS), a life-threatening complement-mediated disorder, is now treatable with terminal complement inhibitors like eculizumab. Although effective, these therapies are costly, and increase susceptibility to infections, notably meningococcal disease, raising concerns about long-term use. The optimal duration of complement inhibition remains unclear, prompting efforts to explore the possibility of treatment discontinuation. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the benefits and risks of stopping terminal complement inhibitor therapy in aHUS. We searched PubMed, Scopus, and CINAHL for studies of continuing vs stopping anticomplement treatment in aHUS. Of 3303 identified studies, 13 observational studies (3 case control and 10 cohort) comprising 584 patients were included. Overall, continuing treatment was associated with an ∼76% reduction in the odds of relapse (odds ratio [OR], 0.24; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.09-0.62; P = .01). Study design influenced results: cohort studies showed a more modest effect (OR, 0.40 [95% CI, 0.15-1.09]), whereas case-control studies reported inflated estimates (OR, 0.04; 95% CI, 0.02-0.08; subgroup interaction P = .03). When the analysis was restricted to cohort studies, the effects became uncertain (statistically nonsignificant with large CIs, indicating the possibility that outcomes with continued treatment could be either superior or inferior to those observed after treatment withdrawal, or that there may be no true difference in relapse rates between the 2 therapies). Although current evidence is insufficient to provide personalized guidance on which patients with aHUS can safely discontinue anticomplement therapy, findings from higher-quality studies, which show no statistical difference between continued and discontinued treatment, suggest that discontinuation may be possible for at least some patients.

Introduction

Thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) includes a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by the triad of Coombs negative microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and organ dysfunction, which most commonly presents as acute kidney injury.1 The term hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) has been used to describe a subset of these diseases, but current nomenclature has shifted to emphasize underlying pathogenic mechanisms rather than clinical presentation alone.2 It is classified according to suspected etiology, for example, the most common TMA is infection-associated TMA, which can be secondary to Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and H1N1/influenza A. Primary TMA can be complement-mediated (atypical HUS [aHUS]) or noncomplement-mediated TMA. Complement-mediated HUS (CM-HUS), also known as aHUS, can be due to a mutation in a complement gene or the presence of factor H (FH) autoantibodies. CM-HUS accounts for ∼10% of all HUS cases. Non–CM-HUS includes metabolism-associated HUS such as cobalamin C and G disease, or variants in DGKE and WT1 genes. Secondary aHUS occurs in association with an alternative underlying etiology (eg, secondary to malignant hypertension, autoimmune disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, or scleroderma, malignancy-induced, pregnancy-associated, stem cell and solid organ transplantation, or drugs such as calcineurin inhibitors, oral contraceptives, and quinine).1

aHUS is characterized by cases resulting from dysregulation of the complement cascade, a critical component of innate immunity. These can be due to genetic variants in complement regulatory proteins or autoantibodies against these proteins; however, a pathologic variant is not always identified, and thus aHUS remains a clinical diagnosis.3 aHUS was historically associated with extremely high mortality, but is now successfully treated with terminal complement inhibitors with excellent prognosis with cumulative estimate of end-stage renal disease–free survival improved from 39.5% in the control cohort to 85.5% in the eculizumab-treated cohort.1,4 Eculizumab and ravulizumab are a humanized monoclonal antibodies that specifically target and inhibit C5, blocking the terminal complement pathway while preserving the important immunoprotective and immunoregulatory functions of proximal complement activation.4 By preventing C5 cleavage into C5a and C5b, eculizumab effectively blocks the formation of the C5b-9 complex, which is responsible for causing cell lysis, endothelial injury, and thrombosis in aHUS.5 This inhibition reduces complement-mediated damage to the kidney and other organs, leading to a significant reduction in the clinical manifestations of aHUS. However, terminal complement inhibitors such as eculizumab or ravulizumab are typically recommended to continue indefinitely, and are associated with financial burden and adverse events (eg, incidence of meningococcal infection 0.0055 per person year).4 Attempts have been made to discontinue terminal complement inhibitor therapy, hoping that long-term remission can be maintained without extracosts or risks associated with anticomplement therapies, though the optimal duration of complement inhibition remains unknown.1,6 A narrative review published in 2022 identified 5 studies that discontinued terminal complement inhibitor therapy and reaffirmed the uncertainty about the optimal duration of anticomplement therapies.1 To address this uncertainty and provide a more comprehensive assessment of the discontinuation of terminal complement inhibitors, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of cessation of the treatment for complement-mediated aHUS.

Our main objective was to determine whether discontinuation of eculizumab lead to an increase in aHUS relapse. As a part of the review, we grouped the studies on various classifications such as gene mutations, follow-up time, and study type to see if any significant differences could be found. We also documented the rate of adverse outcomes including meningococcal infections, treatment-related mortality, infusion reactions, and serious adverse events (SAEs) related to terminal complement inhibitor therapies.

Methods

Search strategy

Using terms designed by a medical librarian (supplemental Search Term 1), we electronically searched PubMed (US National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health), Scopus (Elsevier), and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Heath Literature (CINAHL) Complete (EBSCOhost) from inception through 18 February 2025. The search strategy used a combination of subject headings (eg, MeSH in PubMed) and keywords for concepts related to aHUS and discontinuation of terminal complement inhibitor therapies. The PubMed search strategy was modified for the other 2 databases, replacing MeSH terms with appropriate subject headings, when available, and maintaining similar keywords. The search strategy was peer-reviewed by a second librarian using a modified Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) checklist.7 To identify additional articles, the reference lists of included articles were hand-searched and cited.

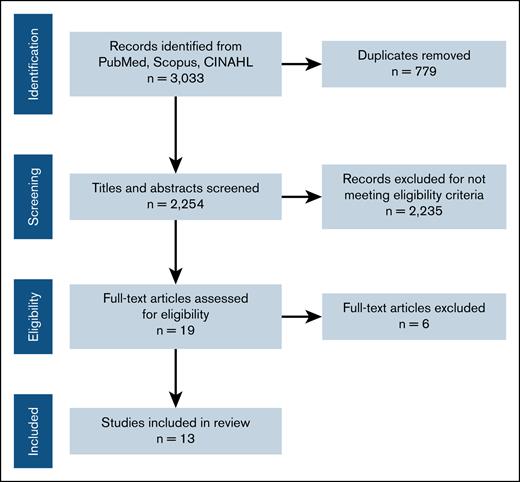

Selection of studies

References were exported into the review management software, Covidence, for deduplication and study selection.8 Two review authors independently screened titles and abstracts to determine eligibility using our selection criteria. Conflicts were resolved by a third reviewer. Following the same process, 2 review authors then independently screened full-text articles, with conflicts being resolved by a third reviewer. The study selection process is presented as a flowchart according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) statement,9 showing the total number of retrieved references, and the numbers of included and excluded studies (Figure 1).

Studies that were selected were comparative studies evaluating the outcomes of continuing vs discontinuing terminal complement inhibitor therapy in patients diagnosed with aHUS. For this review, aHUS was defined as aHUS with identified genetic variants in complement genes or exclusion of other secondary TMAs, as reported in the included studies. There were no randomized controlled trials conducted on this topic, and we included observational studies such as case-control and cohort studies with historical controls. Studies published in any language as full-text or abstracts were eligible if sufficient information was available on study design, characteristics of participants, interventions, and outcomes. The studies included patients of any age diagnosed with aHUS as defined in each report. All studies were eligible if they used the intervention of terminal complement inhibitor therapy. Although the studies did not formally exclude ravulizumab, none captured its use; thus, all evaluated discontinuation of eculizumab. The studies that did not fulfill the criteria listed previously were excluded. In particular, noncomparative studies and studies where terminal complement inhibitor therapy was used while awaiting the final diagnostic confirmation of aHUS were excluded. Studies including patients without aHUS, animal or basic sciences studies, therapies other than terminal complement inhibitors, studies with no historical or simultaneous control, or narrative reviews, editorials, and commentaries were excluded.

Data extraction

For each included study, 4 authors independently extracted data using a standardized form. Extracted data included study characteristics, participant characteristics including genetic variant testing completed by each study, outcomes of interest, length of follow-up, and quality assessment (Table 1). Discrepancies in data extraction relied on a fifth author arbitration when needed. The primary efficacy outcomes were relapse. Additional outcomes of interest included adverse events, including rate of meningococcal infections, infusion reactions and SAEs related to terminal complement inhibitor therapies (including method of adverse events ascertainment, and how severity or seriousness was measured).

Study characteristics for each included study

| Author (year) . | Setting . | Country . | NOS score . | Study design . | Industry funded . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ardissino10 (2024) | Center for HUS Prevention, Control, and Management | Italy | 7 | Case-control | No |

| Baskin et al11 (2022) | Turkish aHUS Registry | Turkey | 7 | Cohort | No |

| Brocklebank et al4 (2023) | National Renal Complement Therapeutics Centre | England | 7 | Case-control | No |

| Chaturvedi (2020) | Johns Hopkins Complement Associated Disease Registry | United States | 8 | Cohort | No |

| Ito (2022) | Pediatric Postmarketing Study Cohort | Japan | 7 | Cohort | Yes |

| Kant et al12 (2020) | Johns Hopkins Hospital | United States | 7 | Cohort | No |

| Massa et al13 (2022) | The AORN Cardarelli of Naples | Italy | 7 | Cohort | Not stated |

| Menne et al14 (2019) | N/A | Germany | 8 | Cohort | Yes |

| Merrill et al15 (2017) | Johns Hopkins Complement Associated Disease Registry | United States | 7 | Cohort | Yes |

| Neave et al16 (2019) | UK TMA Referral Centre | United Kingdom | 7 | Cohort | No |

| Palma et al17 (2021) | Brazilian Thrombotic Microangiopathy and Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome Study Group | Brazil | 7 | Case-control | Yes |

| Wetzels et al18 (2015) | Radboud University Medical Center | The Netherlands | 6 | Cohort | Yes |

| Wijnsma et al19 (2018) | Radboud University Medical Center | The Netherlands | 7 | Cohort | No |

| Author (year) . | Setting . | Country . | NOS score . | Study design . | Industry funded . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ardissino10 (2024) | Center for HUS Prevention, Control, and Management | Italy | 7 | Case-control | No |

| Baskin et al11 (2022) | Turkish aHUS Registry | Turkey | 7 | Cohort | No |

| Brocklebank et al4 (2023) | National Renal Complement Therapeutics Centre | England | 7 | Case-control | No |

| Chaturvedi (2020) | Johns Hopkins Complement Associated Disease Registry | United States | 8 | Cohort | No |

| Ito (2022) | Pediatric Postmarketing Study Cohort | Japan | 7 | Cohort | Yes |

| Kant et al12 (2020) | Johns Hopkins Hospital | United States | 7 | Cohort | No |

| Massa et al13 (2022) | The AORN Cardarelli of Naples | Italy | 7 | Cohort | Not stated |

| Menne et al14 (2019) | N/A | Germany | 8 | Cohort | Yes |

| Merrill et al15 (2017) | Johns Hopkins Complement Associated Disease Registry | United States | 7 | Cohort | Yes |

| Neave et al16 (2019) | UK TMA Referral Centre | United Kingdom | 7 | Cohort | No |

| Palma et al17 (2021) | Brazilian Thrombotic Microangiopathy and Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome Study Group | Brazil | 7 | Case-control | Yes |

| Wetzels et al18 (2015) | Radboud University Medical Center | The Netherlands | 6 | Cohort | Yes |

| Wijnsma et al19 (2018) | Radboud University Medical Center | The Netherlands | 7 | Cohort | No |

Assessment of random error and the risk of bias in included studies

Sample size and power calculations (alpha and beta errors) were extracted to assess for random error affecting the reported results. For observational studies, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess quality.20 The NOS separately assesses the bias in case-control and cohort studies.20 Cohort studies were evaluated in terms of selection of cohorts, comparability of cohorts, and assessment of outcome. Case-control studies were evaluated according to the selection of cases and controls, comparability of cases and controls, and ascertainment of exposure.20 Each criterion was given a “star” to judge whether the study could be characterized as low, high, or unclear risk for bias. Three authors appraised the eligible studies. In the case of disagreement, further assessment was made in the consensus with 2 other authors who made the final determination.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes, the number of events and the total number of participants (eg, relapse rate) were extracted. Effects were measured in terms of odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Data synthesis

For studies that were homogenous in clinical and methodological characteristics, all data were pooled in a meta-analysis. We used the Sidik-Jonkman random-effects model for meta-analysis. Analyses were performed according to the recommendations of The Cochrane Collaboration Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.21 The Cochrane statistical software Review Manager (RevMan) 5 and Stata was used for all analyses. One review author entered the data into the software, and 2 additional authors checked the data for accuracy.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity across studies were evaluated in a random-effects meta-analysis by estimating the between-study variance (τ2) with the Sidik-Jonkman model, and conducting Cochran Q test, with a significance threshold of P value <.1. The I2 statistic was used to quantify possible inconsistency (moderate, I2 > 30%; and considerable inconsistency, I2 > 75%).21 The etiology for heterogeneity was identified by exploring potential causes through sensitivity and subgroup analyses. We extracted data on relapse and adverse events, as well as information on study design, patient characteristics, and follow-up duration. Potential publication bias was assessed by generating a funnel plot and statistically tested by conducting Egger linear regression test, considering a P value of <0.1 as significant.21

Results

Literature search

Of the 3303 studies identified, abstract and title review was performed on 2254 abstracts after excluding duplicates. Full-text review was performed on 19 studies, and identified 13 that collectively included 584 patients (Figure 1). There were 3 case-control studies and 10 cohort studies. The characteristics of each included study are reported in Table 1. The demographics of the included patients were representative of the average aHUS population.1

Outcomes

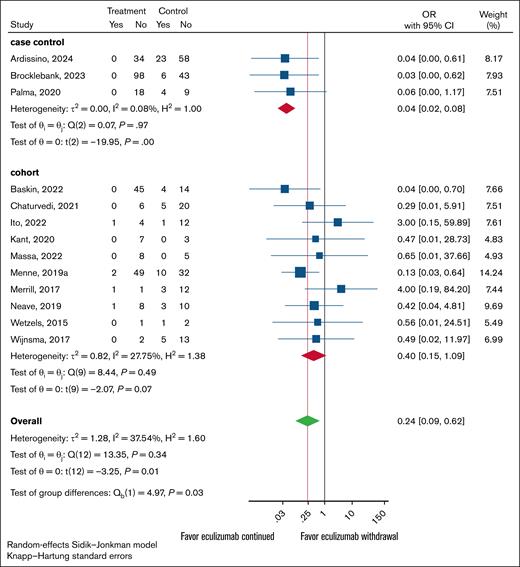

Overall aHUS relapse

Overall, continuing treatment was associated with an ∼76% (95% CI, 38-91) reduction in the odds of relapse, with an OR of 0.24 (95% CI, 0.09-0.62; P = .01; Figure 2). The effects differed by study design: highly significant results favoring continued treatment were observed in case-control studies (OR, 0.04; 95% CI, 0.02-0.08; P < .001), whereas no statistically significant effects were seen in cohort studies (OR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.15-1.09; P = .07). The test of interaction for group differences was significant (P = .03), explaining the reason for the overall heterogeneity (τ2 = 1.28; H2 = 1.6), whereas observing minimal heterogeneity within each design, with fairly consistent treatment effects (Figure 2). Thus, the apparent overall “high heterogeneity” mostly reflects the difference between these 2 study types, not random inconsistency. Because of these findings, we restricted further analyses to cohort studies, generally considered high-quality studies, than the case-control for the assessment of treatment effects (see Discussion). However, we report the results based on all studies in supplemental Figures 1-3.

Forest plot of anticomplement Rx withdrawal vs anticomplement Rx continuation stratified by study design.

Forest plot of anticomplement Rx withdrawal vs anticomplement Rx continuation stratified by study design.

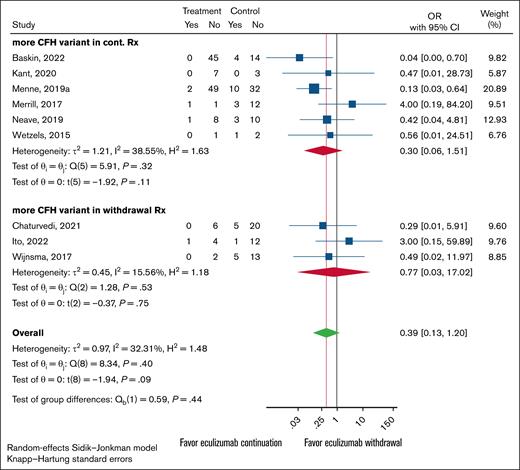

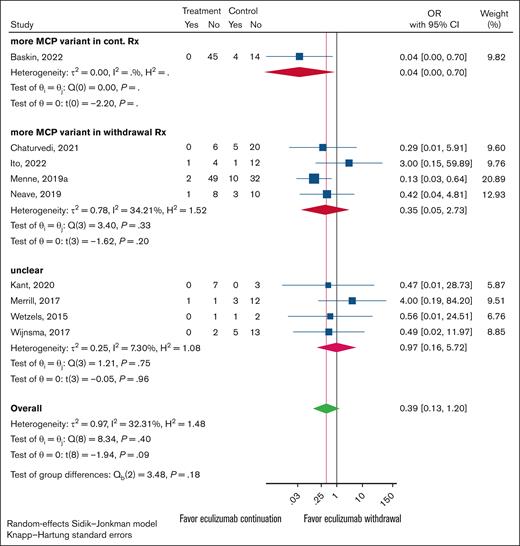

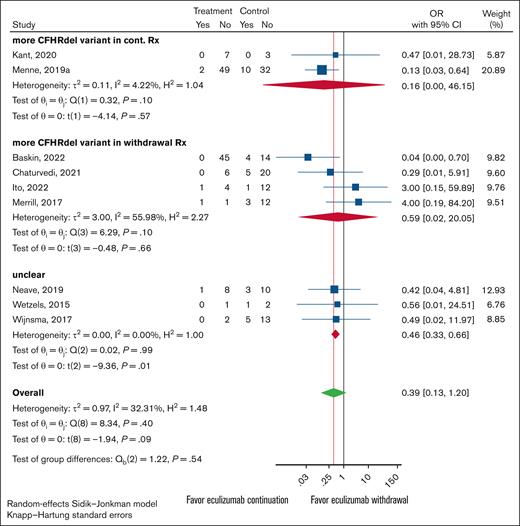

aHUS relapse by gene variant

For each study, the total number of participants with either complement FH (CFH), membrane cofactor protein (MCP), or CFHR1-3 deletion variants were individually tallied. These categories were set up to be mutually exclusive, and patients with multiple variant types (ie, a patient with both CFH and MCP variants) were not counted in either variant type to avoid multiplicities. The studies were then separated for each variant by each arm, the control (continued treatment) group or the experimental (withdraw treatment) group, had the higher count. Studies with equal variant counts in both arms were labeled as unclear.

Overall results for all 3 major variant types were uniform. There were no statistically significant differences in relapse rates between the continued and discontinued arms for any of the gene variants tested. However, the 95% CIs were wide, meaning the results are consistent with possible benefit for either withdrawal or continued treatment, as well as with no true difference between the 2 approaches (Figures 3-5). The analysis indicates that the presence of a particular variant should not guide treatment withdrawal. When considering all likely biased studies, the findings suggested that continued treatment over withdrawal may be superior, but even these cases test of the differences between subgroups was nonsignificant (supplemental Figures 1-3).

Forest plot of anticomplement Rx withdrawal vs anticomplement Rx continuation outcomes restricted to cohort studies. Studies were grouped by which experimental arm, continuation vs withdrawal, had the higher CFH variant presence. Rx, word treatment.

Forest plot of anticomplement Rx withdrawal vs anticomplement Rx continuation outcomes restricted to cohort studies. Studies were grouped by which experimental arm, continuation vs withdrawal, had the higher CFH variant presence. Rx, word treatment.

Forest plot of anticomplement Rx withdrawal vs anticomplement Rx continuation outcomes restricted to cohort studies. Studies were grouped by which experimental arm, continuation vs withdrawal, had the higher MCP variant presence. When the continuation and withdrawal groups had equal counts, the study was classified as unclear.

Forest plot of anticomplement Rx withdrawal vs anticomplement Rx continuation outcomes restricted to cohort studies. Studies were grouped by which experimental arm, continuation vs withdrawal, had the higher MCP variant presence. When the continuation and withdrawal groups had equal counts, the study was classified as unclear.

Forest plot of anticomplement Rx withdrawal vs anticomplement Rx continuation outcomes restricted to cohort studies. Studies were grouped by which experimental arm, continuation vs withdrawal, had the higher CFHR1-3 deletion variant presence. When the continuation and withdrawal groups had equal counts, the study was classified as unclear.

Forest plot of anticomplement Rx withdrawal vs anticomplement Rx continuation outcomes restricted to cohort studies. Studies were grouped by which experimental arm, continuation vs withdrawal, had the higher CFHR1-3 deletion variant presence. When the continuation and withdrawal groups had equal counts, the study was classified as unclear.

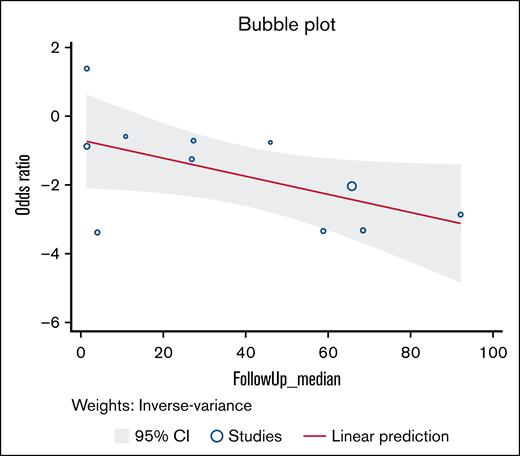

Length of follow-up

As a part of data extraction, the median time on treatment and median length of follow-up for each study was recorded. The median time on treatment for all studies was 6.6 months. The median length of follow-up was 27.4 months. We examined the relationship between relapse rates at various lengths of follow-up time cutoffs (6 months, 1 year, 18 months, 3 years, and 5 years). There were no significant differences between any length of follow-up time groupings. Overall follow-up time demonstrated a negative linear relationship with the OR (Figure 6). A cutoff point at which withdrawing treatment would be beneficial could not be identified.

Random-effects meta-regression. Bubble plot for random-effects meta-regression with median follow-up time in months as a study-level covariate.

Random-effects meta-regression. Bubble plot for random-effects meta-regression with median follow-up time in months as a study-level covariate.

Adverse events

Overall, eculizumab was well tolerated, with the most significant adverse events being infections, particularly meningococcal infections.4,22,12,23,15,16 Most infections were managed successfully, and patients continued eculizumab without significant long-term morbidity. Instances of renal impairment and other SAEs were generally infrequent and resolved with treatment.4,11,22 A full list of adverse events is presented in Table 2.

Adverse events included in each study

| Author (year) . | No. of eculizumab patients . | Age at disease onset, y . | Inclusion criteria . | Interventions . | Comparator . | Outcomes . | Length of follow-up . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ardissino10 (2024) | 115 | Median, 30.6 (IQR, 10.1-43.9) | All pediatric and adult patients diagnosed or referred to our center with aHUS from 2002 to 2022 | Conventional therapy | Eculizumab therapy | Short- and long-term relapse rate after discontinuation of therapy | Median, 5.7 years (IQR, 2.5-8.8) |

| Baskin et al11 (2022) | 63 | Median, 3.62 (IQR, 1.29-6.17) | Pediatric patients with aHUS who received >4 doses of eculizumab during the acute phase of the disease | Standard eculizumab therapy | Extended eculizumab therapy | Rate of aHUS relapse after discontinuing eculizumab | Median, 4.9 years (IQR, 1.7-8.4) |

| Brocklebank et al4 (2023) | 147 | Median, 25 y (range, 0-80) | All individuals referred between 2013 and July 2019 with suspected CaHUS who received eculizumab for native kidney disease | Eculizumab-treated CaHUS | Control CaHUS | The 5-year ESKD-free survival | Median, 1514 days (range, 2-3720) |

| Chaturvedi (2020) | 31 | Median, 44 (IQR, 25-53.5) | Individuals who started eculizumab for acute aHUS, without a history of renal transplant | Discontinuation of eculizumab therapy | None | Rate of aHUS relapse after discontinuing eculizumab | Median, 27 months (range, 3-75) |

| Ito (2022) | 40 | Median, 5 (range, 0-17) | Pediatric patients with aHUS who were aged <18 y at the first administration of eculizumab | Eculizumab therapy | None | The safety and efficacy of eculizumab for pediatric patients with aHUS in the real-world setting in Japan | Median, 408 days (range, 126-1681) |

| Kant et al12 (2020) | 10 | Median, 34 (range, 27-50) | Adult patients diagnosed with aHUS established with presence of TMA, acute kidney injury, absence of alternate identifiable etiology from January 2009 to December 2018 | No eculizumab prophylaxis | Eculizumab prophylaxis | Mortality and death-censored graft loss | Median, 3.48 years (range, 0.36-7.21) |

| Massa et al13 (2022) | 27 | N/A | Patients diagnosed with aHUS between January 2018 and December 2021 | Eculizumab therapy | None | N/A | N/A |

| Menne et al14 (2019) | 93 | Median, 21 (range, 0-80) | Patients with aHUS who participated in any of 5 parent eculizumab trials, and received at least 1 eculizumab infusion | Eculizumab therapy | None | The safety and efficacy of eculizumab for patients with aHUS | Median, 65.7 months (range, 9.9-102.2) |

| Merrill et al15 (2017) | 17 | Median 46 y (range, 19-74 y) | Adult patients diagnosed with aHUS and treated with eculizumab | Eculizumab therapy | None | Rate of aHUS relapse after discontinuing eculizumab | Median, 308.5 days (range, 33-1390) |

| Neave et al16 (2019) | 22 | Median, 32 (range, 16-67) | All adult patients prescribed ≥1 dose of eculizumab for an acute presentation of aHUS | Eculizumab therapy | None | Rates of renal recovery and rates of aHUS relapse in patients withdrawn from eculizumab | Median, 85 weeks (range 4-255) |

| Palma et al17 (2021) | 31 | Median, 18 (IQR, 1.83-30) | Adult and pediatric patients diagnosed with aHUS and treated with eculizumab | Eculizumab therapy | None | Rate of aHUS relapse after discontinuing eculizumab | Mean, 92 ± 78 months (adult) and 59 ± 46 months (pediatric) |

| Wetzels et al18 (2015) | 4 | Median, 28.5 (range, 21-43) | Patients with aHUS and CFH mutation | Discontinuation of eculizumab therapy | None | Rate of aHUS relapse after discontinuing eculizumab | Median, 11 months (range, 3-17) |

| Wijnsma et al19 (2018) | 20 | Median, 24 (IQR, 7-40) | All pediatric and adult patients with aHUS who were treated with eculizumab from November 2012 to October 2016 | Discontinuation of eculizumab therapy | None | Rate of aHUS relapse after discontinuing eculizumab | Median, 27.4 months (IQR, 7.8-42) |

| Author (year) . | No. of eculizumab patients . | Age at disease onset, y . | Inclusion criteria . | Interventions . | Comparator . | Outcomes . | Length of follow-up . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ardissino10 (2024) | 115 | Median, 30.6 (IQR, 10.1-43.9) | All pediatric and adult patients diagnosed or referred to our center with aHUS from 2002 to 2022 | Conventional therapy | Eculizumab therapy | Short- and long-term relapse rate after discontinuation of therapy | Median, 5.7 years (IQR, 2.5-8.8) |

| Baskin et al11 (2022) | 63 | Median, 3.62 (IQR, 1.29-6.17) | Pediatric patients with aHUS who received >4 doses of eculizumab during the acute phase of the disease | Standard eculizumab therapy | Extended eculizumab therapy | Rate of aHUS relapse after discontinuing eculizumab | Median, 4.9 years (IQR, 1.7-8.4) |

| Brocklebank et al4 (2023) | 147 | Median, 25 y (range, 0-80) | All individuals referred between 2013 and July 2019 with suspected CaHUS who received eculizumab for native kidney disease | Eculizumab-treated CaHUS | Control CaHUS | The 5-year ESKD-free survival | Median, 1514 days (range, 2-3720) |

| Chaturvedi (2020) | 31 | Median, 44 (IQR, 25-53.5) | Individuals who started eculizumab for acute aHUS, without a history of renal transplant | Discontinuation of eculizumab therapy | None | Rate of aHUS relapse after discontinuing eculizumab | Median, 27 months (range, 3-75) |

| Ito (2022) | 40 | Median, 5 (range, 0-17) | Pediatric patients with aHUS who were aged <18 y at the first administration of eculizumab | Eculizumab therapy | None | The safety and efficacy of eculizumab for pediatric patients with aHUS in the real-world setting in Japan | Median, 408 days (range, 126-1681) |

| Kant et al12 (2020) | 10 | Median, 34 (range, 27-50) | Adult patients diagnosed with aHUS established with presence of TMA, acute kidney injury, absence of alternate identifiable etiology from January 2009 to December 2018 | No eculizumab prophylaxis | Eculizumab prophylaxis | Mortality and death-censored graft loss | Median, 3.48 years (range, 0.36-7.21) |

| Massa et al13 (2022) | 27 | N/A | Patients diagnosed with aHUS between January 2018 and December 2021 | Eculizumab therapy | None | N/A | N/A |

| Menne et al14 (2019) | 93 | Median, 21 (range, 0-80) | Patients with aHUS who participated in any of 5 parent eculizumab trials, and received at least 1 eculizumab infusion | Eculizumab therapy | None | The safety and efficacy of eculizumab for patients with aHUS | Median, 65.7 months (range, 9.9-102.2) |

| Merrill et al15 (2017) | 17 | Median 46 y (range, 19-74 y) | Adult patients diagnosed with aHUS and treated with eculizumab | Eculizumab therapy | None | Rate of aHUS relapse after discontinuing eculizumab | Median, 308.5 days (range, 33-1390) |

| Neave et al16 (2019) | 22 | Median, 32 (range, 16-67) | All adult patients prescribed ≥1 dose of eculizumab for an acute presentation of aHUS | Eculizumab therapy | None | Rates of renal recovery and rates of aHUS relapse in patients withdrawn from eculizumab | Median, 85 weeks (range 4-255) |

| Palma et al17 (2021) | 31 | Median, 18 (IQR, 1.83-30) | Adult and pediatric patients diagnosed with aHUS and treated with eculizumab | Eculizumab therapy | None | Rate of aHUS relapse after discontinuing eculizumab | Mean, 92 ± 78 months (adult) and 59 ± 46 months (pediatric) |

| Wetzels et al18 (2015) | 4 | Median, 28.5 (range, 21-43) | Patients with aHUS and CFH mutation | Discontinuation of eculizumab therapy | None | Rate of aHUS relapse after discontinuing eculizumab | Median, 11 months (range, 3-17) |

| Wijnsma et al19 (2018) | 20 | Median, 24 (IQR, 7-40) | All pediatric and adult patients with aHUS who were treated with eculizumab from November 2012 to October 2016 | Discontinuation of eculizumab therapy | None | Rate of aHUS relapse after discontinuing eculizumab | Median, 27.4 months (IQR, 7.8-42) |

CaHUS, complement-mediated atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; IQR, interquartile range.

Quality of evidence

The quality assessment using the NOS is summarized in supplemental Table 1. Although the studies had scores >6 (indicating possible high quality), because of their retrospective, observational nature they were ultimately judged as low quality (certainty) evidence as per Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) guidance (see Discussion).24 There was 1 study graded as fair quality. There was no evidence of publication bias.25,26Table 3 shows multivariable meta-regression displaying effects of simultaneous adjustment for multiple covariates on the results of the analysis (supplemental Table 1). Study design, quality score, median follow-up and gene mutations (CFH, CFHdel, and MCP) were included in the analysis. The variable representing an interaction between study design and the quality score is statistically significant at P value .051, likely explaining heterogeneity observed in the results (Figure 2).

Adverse Events included in each study

| Author (year) . | No discussion of SAEs . | No SAEs experienced . | Meningococcal infections . | Other infections (bacterial, viral) . | Deaths . | Other listed SAEs . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ardissino10 (2024) | X | 4 | ||||

| Baskin et al11 (2022) | Allergic reaction (1) | |||||

| Brocklebank et al4 (2023) | 3 | Headache (1) | ||||

| Chaturvedi (2020) | X | 1 | ||||

| Ito (2022) | 1 | 12 | 4∗ | Renal impairment (5) | ||

| Kant et al12 (2020) | 0 | 1 (1, 0) | 3∗ | |||

| Massa et al13 (2022) | X | 11 (3∗) | ||||

| Menne et al14 (2019) | 4 | 14 (6, 8) | 3 | |||

| Merrill et al15 (2017) | 0 | 1 (1, 0) | 2 | |||

| Neave et al16 (2019) | X | 0 | 1 (1, 0) | 1 | ||

| Palma et al17 (2021) | X | 1 | ||||

| Wetzels et al18 (2015) | X | |||||

| Wijnsma et al19 (2018) | X |

| Author (year) . | No discussion of SAEs . | No SAEs experienced . | Meningococcal infections . | Other infections (bacterial, viral) . | Deaths . | Other listed SAEs . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ardissino10 (2024) | X | 4 | ||||

| Baskin et al11 (2022) | Allergic reaction (1) | |||||

| Brocklebank et al4 (2023) | 3 | Headache (1) | ||||

| Chaturvedi (2020) | X | 1 | ||||

| Ito (2022) | 1 | 12 | 4∗ | Renal impairment (5) | ||

| Kant et al12 (2020) | 0 | 1 (1, 0) | 3∗ | |||

| Massa et al13 (2022) | X | 11 (3∗) | ||||

| Menne et al14 (2019) | 4 | 14 (6, 8) | 3 | |||

| Merrill et al15 (2017) | 0 | 1 (1, 0) | 2 | |||

| Neave et al16 (2019) | X | 0 | 1 (1, 0) | 1 | ||

| Palma et al17 (2021) | X | 1 | ||||

| Wetzels et al18 (2015) | X | |||||

| Wijnsma et al19 (2018) | X |

X, not discussed/listed in specific study.

Deaths noted in study not attributable to eculizumab treatment.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the outcomes of discontinuing terminal complement inhibitor therapy in patients with aHUS. When considering all studies, continuing terminal complement inhibitor therapy reduced the odds of relapse by 76% (OR, 0.24; 95% CI, 0.09-0.62; P = .01). The absolute risk difference between withdrawing treatment and continuing treatment is 16.5% (95% CI, 7.56-20.5), converting into number needed to harm of 6 (95% CI, 5-13). That is, for every 6 (95% CI, 5-13) patients who are withdrawn from treatment, 1 will relapse compared with those who continue treatment. The potential benefit of continuing terminal complement inhibitor therapy to prevent relapse was seen in studies in case-control study designs, which are more susceptible to bias. The evidence from more reliable cohort studies demonstrated no significant differences between continuing and discontinuing therapy, indicating that it may be possible to discontinue terminal complement inhibitors in some patients.

In case-control studies, the risk of bias is particularly high due to the retrospective nature of data collection, in which cases and controls are selected after the outcome has occurred. This design could lead to selection bias, as it might overrepresent patients who have experienced a relapse or treatment failure, thereby inflating the apparent effectiveness of continued therapy. In contrast, cohort studies, which are less prone to selection bias, did not show a clear advantage for continuing therapy in most cases. Thus, there may be individuals in whom discontinuation of terminal complement inhibitor therapy could be considered, given their relatively lower risk of relapse. These results are consistent with our own experience, which suggests that some patients can safely discontinue anticomplement therapy. However, based on current evidence, it is not possible to individualize this decision. Although relapse rates decrease with longer follow-up (Figure 6), our data did not allow us to identify a specific cutoff at which anticomplement therapy can be safely stopped. Therefore, this decision remains dependent on the treating physician’s judgment, and on the patient’s preferences and values regarding the risks and benefits of stopping vs continuing treatment.

The relationship between genetic mutations and the response to terminal complement inhibitor therapy is an intriguing finding, but remains inconclusive. When considering all studies, we found that patients with multiple complement gene variants appear to benefit more from continued therapy, but, as explained earlier, the results were not conclusive (supplemental Figures 1-3). This was not the case when we restricted our analysis to higher-quality studies (Figures 3-5). Interestingly, we observed no impact of the gene CFH mutation in isolation on the effects of terminal complement inhibitor therapy. Given that the literature supports prognostic association of CFH gene mutation with relapse,27 this may indicate that the CFH mutation is not predictive of relapse after discontinuation of terminal complement inhibitor therapy. It may be more important to consider the total mutational burden when considering to discontinue terminal complement inhibitor therapy.

The included studies varied in their classification of variants as pathogenic, likely pathogenic, or variants of uncertain significance, which may contribute to heterogeneity in the reported outcomes. In the systematic review conducted by Acosta-Medina et al28 the presence of complement gene variants was found to significantly influence relapse risk following therapy withdrawal in patients with complement-mediated diseases. Specifically, individuals harboring such genetic variants demonstrated an almost threefold increase in the risk of relapse compared with those without these mutations. Notably, mutations in the CFH and MCP/CD46 genes were especially associated with a markedly elevated risk, underscoring the pathogenic role of dysregulated complement control in disease recurrence. In contrast, our study observed a uniform distribution of the 3 major variant types among participants, suggesting no particular genetic variant predominated, which can explain our results.

Therefore, while previous studies have highlighted the prognostic significance of specific complement gene mutations in relapse risk, our findings suggest that treatment decisions, particularly regarding therapy withdrawal, should not be based solely on genetic variant status. Instead, clinical judgment should incorporate a broader assessment of relapse risk, given that ongoing treatment appears to mitigate this risk across genetic subgroups.

A critical limitation of our gene variant analysis is the inherent selection bias in included studies. Clinicians likely made nonrandom decisions regarding eculizumab continuation vs discontinuation based on patients’ known genetic profiles. Patients with high-risk mutations (especially CFH or multiple variants) were likely preferentially kept on therapy, while those with no identified variants were more often selected for discontinuation. This selection bias may artificially inflate the apparent effectiveness of continued therapy in studies with higher gene variant ratios. This phenomenon helps explain the dramatically larger effect sizes in case-control studies compared with cohort studies.

In addition, in our analysis of continuing vs discontinuing eculizumab in aHUS, we found that some studies included patients without identified complement mutations in both treatment arms. In the clinical studies that formed the basis for eculizumab approval, 24% to 41% of patients had no identified genetic complement mutation or detectable CFH autoantibodies, yet showed similar treatment responses to those with identified mutations. When examining discontinuation outcomes specifically, Fakhouri et al29 found that out of 38 patients who discontinued eculizumab, 16 patients (42%) had no rare variants detected and, notably, none of these patients without identified mutations experienced relapse after discontinuation.

Future research should address this selection bias through randomized designs to balance genetic risk between comparison groups.

We also examined length of follow-up time in conjunction with relapse rates in this analysis. Studies were divided by length of follow-up time at 6 months, 1 year, 18 months, 3 years, and 5 years. There was no significant difference in the relapse rates with any of the lengths of follow-up time grouping. This indicates that the further removed from treatment withdrawal, the lower the likelihood of relapse. This is reinforced by Bouwmeester et al,30 who followed patients for 4 years, with most relapses occurring within the first year. However, there is no distinguishable length of follow-up time at which relapse rate increases after withdrawing treatment.

Adverse events were not consistently reported across studies, and drawing firm conclusions regarding them is challenging. Nonetheless, the potential for SAEs—such as meningococcal infections, infusion reactions, and treatment-related mortality—cannot be overlooked, especially given the higher infection risk associated with long-term complement inhibition. Although adverse events were relatively uncommon, the high risk of meningococcal infections remains a significant concern for patients on lifelong treatment. Brocklebank et al3 reported the rate of meningococcal infection in the treated cohort was 550 times greater than the background rate in the general population (incidence 550 per 100 000 person years, compared with a background national incidence of 1 per 100 000). This converts into number needed to harm of ∼182, calculated as 1/((550/100 000) – 1/(100 000)), indicating that ∼182 persons would need to be treated with anticomplement for a year for 1 patient to suffer from meningococcal infection, relative to the background rate. However, following clinical guidelines with vaccination and prophylactic penicillin, this risk can be reduced but not eliminated.

One of the key limitations of this study is the absence of randomized controlled trials. Observational studies are inherently more prone to biases such as confounding and selection bias, which can skew results. An additional barrier that emerged during analysis was the lack of uniform, standardized reporting of all planned outcome analyses. Due to poor quality of reporting, we were not able to extract data on overall survival, treatment-related mortality, renal function response, correction of anemia, and only provide narrative review of adverse events. 8 It is important to emphasize that our analysis relied heavily on the quality of reporting in the included studies. Unfortunately, reporting in this field has often been suboptimal and lacking in transparency. For example, even basic data such as the number of patients in each arm (denominator) and the number who relapsed (numerator) were frequently difficult to determine. These issues became even more pronounced in subgroup analyses by gene mutations. Given the importance of high-quality evidence synthesis for guideline development and clinical practice, we believe this is an important methodological contribution.

Despite the noted limitations, our analysis provides valuable insights into the ongoing debate surrounding terminal complement inhibitor therapy for aHUS. It highlights the potential for discontinuation in select patients, particularly those with fewer variants, but also underscores the need for careful monitoring and individualized decision-making. Until more robust evidence is available, clinicians should weigh the risks and benefits of continuing therapy on a case-by-case basis, considering all relevant clinical factors, including genetic profile, history of relapse, and the potential for adverse events.

Authorship

Contribution: A.H. extracted the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; B.D. designed the study, extracted the data, conducted the review, performed the meta-analysis, and contributed to writing the manuscript; S.A. conducted the review and performed the meta-analysis; S.R.C. extracted the data and performed the meta-analysis; E.B. created the search strategy; A.C. extracted the data and contributed to the manuscript; J.N.P. and C.G. reviewed the manuscript; and all authors agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Amy Hockman, Medical University of South Carolina, 171 Ashley Ave, Charleston, SC 29425; email: amh304@musc.edu.

References

Author notes

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Amy Hockman (amh304@musc.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.