Key Points

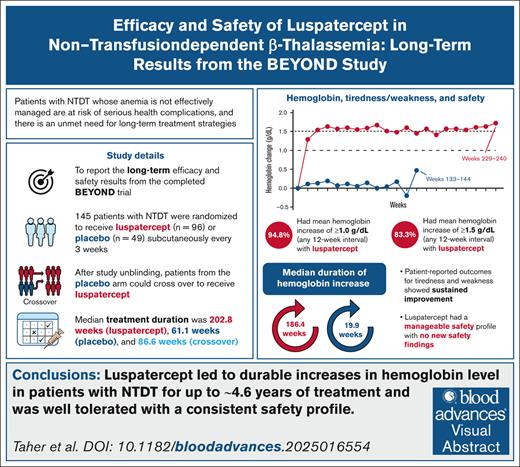

Luspatercept treatment led to durable increases in hemoglobin levels in patients with NTDT (up to ∼4.6 years of treatment).

Luspatercept was well tolerated in the study population, and had a long-term safety profile that was consistent with previous studies.

Visual Abstract

Chronic anemia due to non–transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia (NTDT) can result in clinical morbidities, particularly with inadequate management. Luspatercept was previously shown to improve hemoglobin levels in patients with NTDT in the phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled BEYOND trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03342404). Here, we report long-term efficacy and safety results from the final analysis of BEYOND spanning an additional 26 months (∼2.2 years) of follow-up. Median treatment duration was 202.8 weeks for luspatercept and 61.1 weeks for placebo. Overall, 94.8% and 22.4% of patients in the luspatercept and placebo arms, respectively, achieved a mean hemoglobin increase from baseline ≥1.0 g/dL during any 12-week interval, with mean durations of response of 1136.0 and 203.3 days, respectively. Patient-reported tiredness and weakness showed sustained improvement with luspatercept treatment. The most common treatment-emergent adverse events in the luspatercept group were headache (45.8% vs 20.4% with placebo), bone pain (43.8% vs 6.1%), back pain (39.6% vs 12.2%), and arthralgia (38.5% vs 16.3%). Treatment-emergent extramedullary hematopoiesis events were reported in 12 (9.0%) and 2 (4.1%) patients receiving luspatercept and placebo, respectively, although differences in treatment exposures prevented informative comparisons. Of the 4 patients receiving luspatercept who reported thromboembolic events, all had >1 risk factor. These results show that luspatercept led to a sustained increase in hemoglobin levels in patients with NTDT for up to ∼4.6 years of treatment, with a consistent safety profile and no new safety findings. Luspatercept is a valuable treatment option for patients with NTDT, addressing the need for effective long-term treatment of anemia. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT03342404.

Introduction

β-Thalassemia is a genetic disorder that results in absent or reduced production of functional β-globin chains of hemoglobin, leading to chronic anemia.1 Based on red blood cell (RBC) transfusion requirements over time, β-thalassemia is classified as either transfusion-dependent thalassemia (TDT) or non-TDT (NTDT). Patients with NTDT may require RBC transfusions sporadically under specific circumstances, such as surgery, infection, pregnancy, or management of clinical complications.1,2 Although patients with NTDT usually have less severe anemia, they report lower quality-of-life (QoL) scores than patients with TDT.3,4 In NTDT cases where anemia is not managed effectively, patients can suffer from serious health complications (eg, osteoporosis, bone deformities, hepatosplenomegaly, extramedullary hematopoiesis [EMH], primary iron overload, end organ damage, hypercoagulability, and vascular disease), and have compromised life expectancy compared with healthy individuals.5-8 This highlights the importance of timely and appropriate disease management. Furthermore, various observational studies have indicated a higher risk of morbidities and significantly worse overall survival in patients with NTDT whose hemoglobin levels are <10 g/dL; these studies also found that hemoglobin increases by 1.0 g/dL significantly decreased the odds of developing morbidities,9-12 and prompted guidelines recommendations on the treatment of NTDT-associated anemia.2,13

Treatment strategies for patients with NTDT focus on managing chronic anemia, and include RBC transfusions, splenectomy, and fetal hemoglobin inducers such as hydroxyurea.2,13,14 However, these treatments can result in iron overload, alloimmunization, and increased risk of serious infections and thromboembolic events (TEEs).2,13-16 Available data on fetal hemoglobin induction with hydroxyurea are scarce or inconclusive, and there is a lack of randomized controlled trials in NTDT.2,16,17 Given the limited treatment options and their associated complications, there is a high unmet need for effective and safe treatments for NTDT-associated anemia.

Luspatercept is a novel transforming growth factor-β superfamily ligand trap that acts at multiple stages of erythropoiesis, and leads to expansion and maturation of erythroid precursors.18-21 Luspatercept is approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of anemia in patients with TDT based on data from the phase 3 BELIEVE study, in which luspatercept significantly reduced transfusion burden.22 In the primary analysis of the BEYOND study in patients with NTDT, a significantly higher proportion of patients treated with luspatercept achieved a hemoglobin increase ≥1.0 g/dL compared with patients receiving placebo,23 leading to European Medicines Agency approval of luspatercept for the treatment of adults with NTDT-associated anemia. Here, we report the long-term efficacy and safety results from the completed BEYOND study.

Methods

The BEYOND study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03342404) was a phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial, with a ≥48-week double-blind treatment phase (patients could continue receiving luspatercept or placebo until after the last enrolled patient completed 48 weeks of treatment) and a subsequent ≤24-month open-label phase. Full details of the trial design and results from the double-blind treatment phase have been published.23 Briefly, adults with NTDT and hemoglobin ≤10 g/dL were randomized (2:1) to luspatercept or placebo, stratified by baseline hemoglobin level (≥8.5 g/dL vs <8.5 g/dL) and NTDT patient-reported outcome tiredness/weakness (NTDT-PRO T/W) domain score (≥3 vs <3).23-25 NTDT-PRO T/W domain scores ≥3 are indicative of symptomatic NTDT,23-25 and a score decrease is considered improvement. Non–transfusion-dependence was defined as requiring ≤5 RBC units per 24 weeks and receiving no RBC transfusions for ≥8 weeks before randomization. Luspatercept was administered subcutaneously once every 3 weeks at a starting dose of 1.0 mg/kg, which could be increased to 1.25 mg/kg or reduced if there was toxicity or excessive hemoglobin increase. Patients received best supportive care, including RBC transfusions when necessary and iron chelation therapy. After unblinding, patients in the luspatercept group could continue to receive luspatercept, whereas patients randomized to placebo could cross over to receive luspatercept during the open-label phase (crossover group). After study completion, patients could continue luspatercept treatment in the long-term follow-up study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04064060).

Primary analysis efficacy and safety results (14 September 2020) have been published.23 Here, we present the long-term analysis results as of the study completion date (28 November 2022). Efficacy end points (analyzed in the intent-to-treat population) have not been assessed in the crossover group due to lack of long-term data; therefore, the luspatercept group referred to herein does not include crossover patients. The following efficacy end points were evaluated in this long-term analysis: achievement of erythroid response (ie, a mean hemoglobin increase from baseline ≥1.0 g/dL during any 12- and 24-week intervals until end of treatment); achievement of a mean hemoglobin increase from baseline ≥1.5 g/dL during any 12-week interval; mean duration of erythroid response; mean time as a responder (percentage of total study duration); mean changes in hemoglobin from baseline by 12-week intervals (weeks 1-240); proportions of patients who remained RBC transfusion-free during the entire treatment period; median time to first RBC transfusion; mean changes from baseline in serum ferritin (SF); and liver iron concentration (LIC) overall and based on iron chelation therapy receipt. Mean change from baseline in NTDT-PRO T/W domain score (week 1 until end of treatment) was evaluated in the health-related QoL-evaluable population, defined as all randomized patients with an evaluable assessment of a given PRO or health-related QoL measure at baseline and ≥1 postbaseline visit.

Safety assessments (analyzed in the safety population) for patients originally randomized to luspatercept or placebo and for the crossover group included treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) by grade; seriousness; relatedness to treatment; and whether they resulted in dose delay, reduction, study drug discontinuation, or death. Other assessed AEs of clinical relevance include bone pain, hypertension, and TEAEs of special interest (EMH, TEEs, malignancies, and premalignant disorders).

Model-based statistics were performed up to week 96. Odds ratios for luspatercept vs placebo with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and P values for erythroid responses were estimated using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test with randomization stratification factor(s) in the model.

Least-squares means of the difference in SF and LIC between luspatercept and placebo arms were based on analysis of covariance models with treatment group, baseline hemoglobin category (≥8.5 g/dL vs <8.5 g/dL), baseline NTDT-PRO T/W score (≥3 vs <3), and either baseline SF or LIC as covariates. Derived LIC values (via T2∗, R2∗, or R2 parameter) or electronic case report form collected values were used (patients with LIC values >43 mg/g dry weight were excluded).

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the principles of Good Clinical Practice of the International Council for Harmonisation Harmonised Tripartite Guideline. The protocol, amendments, and informed consent form were approved by each study site’s Institutional Review Board (IRB)/Independent Ethics Committee (IEC). The IRB/IEC and relevant authorities were informed of all subsequent protocol amendments in accordance with local legal requirements. All patients provided written informed consent prior to their participation in the study.

Results

Patient disposition and treatment exposure

Baseline characteristics of patients from the BEYOND study were reported previously.23 Patient disposition is presented in Figure 1. Of 96 and 49 patients randomized to luspatercept and placebo, respectively, 90 (93.8%) and 35 (71.4%) completed 48 weeks of treatment in the double-blind treatment phase. At week 144, 76 (79.2%) patients remained in the luspatercept group; patients originally randomized to placebo had crossed over to receive luspatercept in the open-label phase (38/49 [77.6%]) or discontinued treatment. Of these 38 crossover patients, 31 (81.6%) and 3 (7.9%) completed 48 and 96 weeks of luspatercept treatment, respectively. As of study completion, 93 of 134 (69.4%) patients taking luspatercept including crossover patients had transitioned to the long-term follow-up study (www.ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04064060).

Patient disposition. In the luspatercept (including crossover) group and placebo group, treatment discontinuations occurred in 39 of 134 (29.1%) and 31 of 49 (63.3%) patients, respectively. The main reasons for study drug discontinuation in the luspatercept and placebo groups, respectively, were lack of efficacy (2/134 [1.5%] and 17/49 [34.7%]), withdrawal by patient (23/134 [17.2%] and 10/49 [20.4%]), and AEs (8/134 [6.0%] and 4/49 [8.2%]). AEs leading to study drug discontinuation in patients receiving luspatercept (including crossover) were arthralgia, hemolytic anemia, and lupus-like syndrome (1 patient); spinal cord compression and EMH masses (1 patient); pulmonary arterial hypertension (1 patient); myocardial infarction (1 patient); transient ischemic attack (1 patient); back pain, bone pain, and palpitations (1 patient each). In the placebo group, AEs that led to study drug discontinuation were fatigue and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (1 patient), and hypotension, asthenia, and hepatocellular carcinoma (1 patient each). ∗As of last patient last visit date (28 November 2022).

Patient disposition. In the luspatercept (including crossover) group and placebo group, treatment discontinuations occurred in 39 of 134 (29.1%) and 31 of 49 (63.3%) patients, respectively. The main reasons for study drug discontinuation in the luspatercept and placebo groups, respectively, were lack of efficacy (2/134 [1.5%] and 17/49 [34.7%]), withdrawal by patient (23/134 [17.2%] and 10/49 [20.4%]), and AEs (8/134 [6.0%] and 4/49 [8.2%]). AEs leading to study drug discontinuation in patients receiving luspatercept (including crossover) were arthralgia, hemolytic anemia, and lupus-like syndrome (1 patient); spinal cord compression and EMH masses (1 patient); pulmonary arterial hypertension (1 patient); myocardial infarction (1 patient); transient ischemic attack (1 patient); back pain, bone pain, and palpitations (1 patient each). In the placebo group, AEs that led to study drug discontinuation were fatigue and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (1 patient), and hypotension, asthenia, and hepatocellular carcinoma (1 patient each). ∗As of last patient last visit date (28 November 2022).

Treatment discontinuations were more common in the placebo group (31/49 [63.3%]) than in the luspatercept including crossover group (39/134 [29.1%]). Figure 1 reports the reasons for study drug discontinuation.

Median (range) treatment duration was 202.8 (15.0-242.3) weeks in the luspatercept group, 61.1 (3.0-138.0) weeks in the placebo group, and 86.6 (3.0-97.0) weeks in the crossover group. Median (range) number of study drug doses received per patient was 55.0 (3.0-78.0) in the luspatercept group, 20.0 (1.0-46.0) in the placebo group, and 23.5 (1.0-30.0) in the crossover group.

Among patients in the luspatercept and crossover groups, respectively, 56 (58.3%) and 24 (63.2%) had ≥1 dose titration, 87 (90.6%) and 36 (94.7%) had ≥1 dose delay (mainly due to hemoglobin ≥11.5 g/dL or an AE), 70 (72.9%) and 20 (52.6%) had ≥4 dose delays, and 22 (22.9%) and 5 (13.2%) had ≥1 dose reduction (mainly due to a hemoglobin increase >2.0 g/dL; supplemental Table 1).

Efficacy end points

Erythroid response

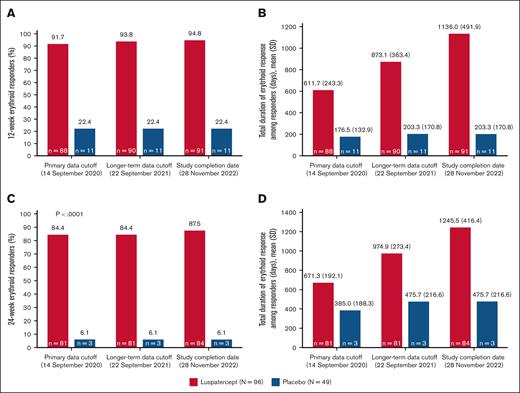

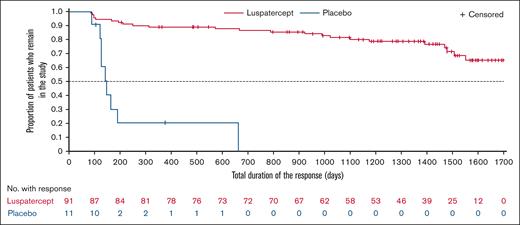

In this final analysis, 91 (94.8%) patients in the luspatercept group achieved erythroid response, defined as mean hemoglobin increase from baseline ≥1.0 g/dL in the absence of RBC transfusions, during any 12-week interval (Figure 2A). The mean (standard deviation [SD]) cumulative duration of erythroid response during any 12-week interval was longer with luspatercept vs placebo at the primary analysis (611.7 [243.3] vs 176.5 [132.9] days); at the end of the study, mean (SD) cumulative duration of erythroid response in the luspatercept arm was 1136.0 (491.9) days (Figure 2B). Supplemental Figure 1 shows comparison of the median treatment duration with the median erythroid response duration. Overall, the mean duration of erythroid response constituted 86.2% and 39.0% of the total study duration for responders in the luspatercept and placebo arms, respectively. Periods of response for individual patients receiving luspatercept are shown in supplemental Figure 2. Median total duration of erythroid response over rolling 12-week intervals in the luspatercept group was not reached as of study completion (Figure 3).

Achievement and duration of 12-week and 24-week erythroid responses. (A) Achievement of 12-week erythroid response; (B) total (cumulative) duration of 12-week erythroid response by data cutoff date; (C) achievement of 24-week erythroid response; (D) total (cumulative) duration of 24-week erythroid response by data cutoff date. Median (range) treatment durations at the primary data cutoff, longer-term data cutoff, and study completion date were 99.7 (15.0-132.1) vs 61.1 (3.0-121.9), 150.1 (15.0-185.4) vs 61.1 (3.0-138.0), and 202.8 (15.0-242.3) vs 61.1 (3.0-138.0) weeks, respectively, for luspatercept vs placebo.

Achievement and duration of 12-week and 24-week erythroid responses. (A) Achievement of 12-week erythroid response; (B) total (cumulative) duration of 12-week erythroid response by data cutoff date; (C) achievement of 24-week erythroid response; (D) total (cumulative) duration of 24-week erythroid response by data cutoff date. Median (range) treatment durations at the primary data cutoff, longer-term data cutoff, and study completion date were 99.7 (15.0-132.1) vs 61.1 (3.0-121.9), 150.1 (15.0-185.4) vs 61.1 (3.0-138.0), and 202.8 (15.0-242.3) vs 61.1 (3.0-138.0) weeks, respectively, for luspatercept vs placebo.

Duration of mean hemoglobin increase from baseline. Kaplan-Meier plot of duration of mean hemoglobin increase from baseline ≥1.0 g/dL over rolling 12-week intervals. Patients receiving placebo were assessed up to crossing over to luspatercept treatment. The luspatercept group does not include crossover patients. Hemoglobin assessment was done using the consecutive rolling 12-week intervals within the double-blind treatment period (ie, from day 2 to day 85, etc). Duration assessment started from the first day of the first rolling 12-week interval during which mean hemoglobin increase from baseline ≥1.0 g/dL was achieved and ended with the last day of the last consecutive rolling 12-week interval during which mean hemoglobin increase from baseline ≥1.0 g/dL was maintained. A patient was censored at the efficacy cutoff, defined as minimum (death date, study discontinuation date, last dose date +20).

Duration of mean hemoglobin increase from baseline. Kaplan-Meier plot of duration of mean hemoglobin increase from baseline ≥1.0 g/dL over rolling 12-week intervals. Patients receiving placebo were assessed up to crossing over to luspatercept treatment. The luspatercept group does not include crossover patients. Hemoglobin assessment was done using the consecutive rolling 12-week intervals within the double-blind treatment period (ie, from day 2 to day 85, etc). Duration assessment started from the first day of the first rolling 12-week interval during which mean hemoglobin increase from baseline ≥1.0 g/dL was achieved and ended with the last day of the last consecutive rolling 12-week interval during which mean hemoglobin increase from baseline ≥1.0 g/dL was maintained. A patient was censored at the efficacy cutoff, defined as minimum (death date, study discontinuation date, last dose date +20).

The proportion of patients achieving erythroid response during any 24-week interval was also significantly higher in the luspatercept vs placebo arm at the primary analysis (81 [84.4%] vs 3 [6.1%]; P < .0001). At study completion, the erythroid response rate during any 24-week interval in the luspatercept group was 87.5% (n = 84; Figure 2C). The mean (SD) duration of 24-week erythroid response with luspatercept at study completion was 1245.5 (416.4) days (Figure 2D).

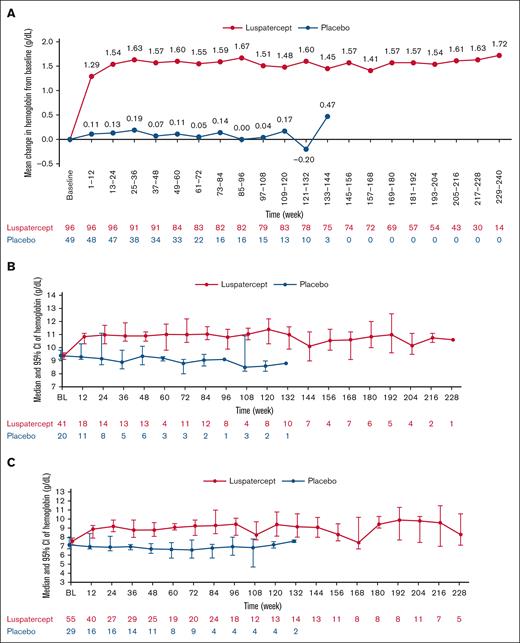

A mean hemoglobin increase ≥1.5 g/dL during any 12-week interval over the entire treatment period was achieved by 80 (83.3%) and 4 (8.2%) patients in the luspatercept and placebo arms, respectively. The mean change in hemoglobin from baseline in the luspatercept group was sustained through week 240 (Figure 4A); Figure 4B-C shows the median (95% CI) hemoglobin levels in the luspatercept and placebo arms during the entire treatment stratified by baseline hemoglobin level (≥8.5 g/dL vs <8.5 g/dL).

Mean change from BL in hemoglobin and median hemoglobin levels during entire treatment period by BL hemoglobin. (A) Mean change from BL in hemoglobin; (B) median (95% CI) hemoglobin levels for patients with ≥8.5 g/dL hemoglobin at BL; (C) median (95% CI) hemoglobin levels for patients with <8.5 g/dL hemoglobin at BL. BL, baseline.

Mean change from BL in hemoglobin and median hemoglobin levels during entire treatment period by BL hemoglobin. (A) Mean change from BL in hemoglobin; (B) median (95% CI) hemoglobin levels for patients with ≥8.5 g/dL hemoglobin at BL; (C) median (95% CI) hemoglobin levels for patients with <8.5 g/dL hemoglobin at BL. BL, baseline.

RBC transfusions

Of the 82 (85.4%) patients in the luspatercept group and 42 (85.7%) patients in the placebo group who had not received any RBC transfusions in the 24 weeks before randomization, 70 (85.4%) and 28 (66.7%) patients, respectively, remained RBC transfusion-free during the entire treatment period. Overall, 75 of 96 (78.1%) patients in the luspatercept arm and 28 of 49 (57.1%) in the placebo arm were RBC transfusion-free during the entire treatment period (supplemental Figure 3). A total of 21 (21.9%) patients in the luspatercept arm received 91 RBC transfusions during treatment (totaling 136 RBC units), whereas 21 (42.9%) patients in the placebo arm received 118 RBC transfusions (190 RBC units). The most reported reason for transfusions in both groups was anemia; other reasons included surgery, leg ulcer, infection, other AEs, prophylaxis for travel, prophylaxis for back pain, and transfusion before receiving COVID-19 vaccination. The median (range) time to first RBC transfusion (for patients who received RBC transfusions) was 233.0 (2.0-1314.0) days in the luspatercept group and 148.0 (9.0-632.0) days in the placebo group. The postbaseline transfusion event frequency, defined as the sum of all transfusion events during the efficacy evaluation period adjusted for continuous 24-week intervals, was nominally significantly lower among patients receiving luspatercept compared with those receiving placebo, with an interval transfusion rate per 24 weeks of 0.12 (95% CI, 0.06-0.22) with luspatercept vs 0.55 (95% CI, 0.34-0.88) with placebo (nominal P < .0001; relative risk vs placebo 0.22 [95% CI, 0.10-0.47]).

In the luspatercept arm, median SF levels remained stable from baseline to week 96, whereas the placebo arm experienced an increase over the same period. Analyses of iron overload are reported in the supplemental Results and Discussion (supplemental Figures 4 and 5).

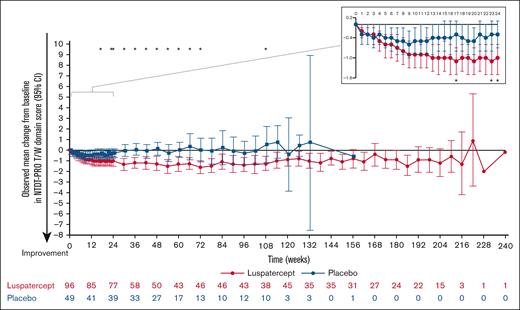

NTDT-PRO T/W domain score

At baseline, patients in the luspatercept and placebo arms had median (interquartile range) NTDT-PRO T/W domain scores of 4.3 (2.4-5.8) and 4.1 (2.5-5.4), respectively, indicative of symptomatic patient-reported tiredness and weakness. During weeks 1 to 24, the NTDT-PRO T/W domain score decreased from baseline in both luspatercept and placebo arms; however, the decrease in the luspatercept group was more pronounced, suggesting improvement in patient-reported tiredness and weakness (Figure 5). After the first 24 weeks, the mean change from baseline in NTDT-PRO T/W domain score in the placebo arm increased and stabilized around 0 throughout the remaining treatment duration, indicating no change in symptoms. In the luspatercept arm, the decrease from baseline was maintained around –1, suggesting a durable improvement in patient-reported tiredness and weakness symptoms for over 200 weeks of treatment (Figure 5).

Observed mean change from baseline in NTDT-PRO T/W domain scores over the entire treatment period. ∗P < .05 indicates statistically significant between-group difference in mean change from baseline.

Observed mean change from baseline in NTDT-PRO T/W domain scores over the entire treatment period. ∗P < .05 indicates statistically significant between-group difference in mean change from baseline.

Safety

An overview of reported TEAEs and TEAEs that occurred in ≥10% of patients in any treatment group are presented in Table 1. TEAEs were reported in 96 (100%) patients in the luspatercept group, 48 (98.0%) in the placebo group, and 38 (100%) in the crossover group; serious TEAEs were reported in 23 (24.0%), 13 (26.5%), and 3 (7.9%) patients, respectively. Treatment-related TEAEs were reported in 79 (82.3%) patients in the luspatercept group, 18 (36.7%) in the placebo group, and 29 (76.3%) in the crossover group, whereas treatment-related serious TEAEs were reported in 4 (4.2%), 0, and 1 (2.6%) patients, respectively. One patient died from pulmonary edema and myocardial ischemia on study day 1190, but this death was considered unrelated to luspatercept by the investigator.

Overview of TEAEs and most common TEAEs

| Patients with ≥1 . | Luspatercept (N = 96) . | Placebo (N = 49) . | Crossover∗ (N = 38) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| TEAE | 96 (100) | 48 (98.0) | 38 (100) |

| Grade ≥3 TEAE | 33 (34.4) | 15 (30.6) | 7 (18.4) |

| Serious TEAE | 23 (24.0) | 13 (26.5) | 3 (7.9) |

| TEAE leading to dose delay | 47 (49.0) | 11 (22.4) | 18 (47.4) |

| TEAE leading to dose reduction | 11 (11.5) | 0 | 2 (5.3) |

| TEAE leading to study drug discontinuation | 5 (5.2) | 4 (8.2) | 3 (7.9) |

| TEAE leading to death | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Treatment-related TEAE | 79 (82.3) | 18 (36.7) | 29 (76.3) |

| Treatment-related grade ≥3 TEAE | 12 (12.5) | 0 | 2 (5.3) |

| Treatment-related serious TEAE | 4 (4.2) | 0 | 1 (2.6) |

| Treatment-related TEAE leading to dose delay | 10 (10.4) | 0 | 3 (7.9) |

| Treatment-related TEAE leading to dose reduction | 11 (11.5) | 0 | 2 (5.3) |

| Treatment-related TEAE leading to study drug discontinuation | 4 (4.2) | 0 | 2 (5.3) |

| Treatment-related TEAE leading to death | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TEAEs occurring in ≥10% of patients in either treatment arm | |||

| Headache | 44 (45.8) | 10 (20.4) | 10 (26.3) |

| Bone pain | 42 (43.8) | 3 (6.1) | 8 (21.1) |

| Back pain | 38 (39.6) | 6 (12.2) | 14 (36.8) |

| Arthralgia | 37 (38.5) | 8 (16.3) | 11 (28.9) |

| COVID-19 | 34 (35.4)† | 0 | 15 (39.5) |

| Pyrexia | 30 (31.3) | 9 (18.4) | 11 (28.9) |

| Pain in extremity | 29 (30.2) | 5 (10.2) | 6 (15.8) |

| Diarrhea | 25 (26.0) | 6 (12.2) | 5 (13.2) |

| Influenza-like illness | 25 (26.0) | 3 (6.1) | 2 (5.3) |

| Cough | 24 (25.0) | 1 (2.0) | 2 (5.3) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 23 (24.0) | 11 (22.4) | 1 (2.6) |

| Fatigue | 23 (24.0) | 10 (20.4) | 8 (21.1) |

| Prehypertension | 23 (24.0) | 7 (14.3) | 3 (7.9) |

| Oropharyngeal pain | 23 (24.0) | 6 (12.2) | 1 (2.6) |

| Pharyngitis | 21 (21.9) | 7 (14.3) | 1 (2.6) |

| Hypertension | 21 (21.9) | 1 (2.0) | 7 (18.4) |

| Asthenia | 19 (19.8) | 5 (10.2) | 0 |

| Dizziness | 19 (19.8) | 4 (8.2) | 3 (7.9) |

| Abdominal pain | 18 (18.8) | 6 (12.2) | 4 (10.5) |

| Dyspepsia | 18 (18.8) | 2 (4.1) | 3 (7.9) |

| Immunization reaction | 18 (18.8) | 0 | 5 (13.2) |

| Myalgia | 16 (16.7) | 5 (10.2) | 3 (7.9) |

| Influenza | 15 (15.6) | 5 (10.2) | 1 (2.6) |

| Abdominal pain upper | 15 (15.6) | 3 (6.1) | 5 (13.2) |

| Toothache | 15 (15.6) | 1 (2.0) | 0 |

| Nausea | 14 (14.6) | 6 (12.2) | 1 (2.6) |

| Iron overload | 14 (14.6) | 5 (10.2) | 0 |

| Insomnia | 14 (14.6) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.6) |

| Menstruation irregular | 13 (13.5) | 3 (6.1) | 2 (5.3) |

| Gastroenteritis | 12 (12.5) | 4 (8.2) | 2 (5.3) |

| Neck pain | 12 (12.5) | 2 (4.1) | 1 (2.6) |

| Epistaxis | 12 (12.5) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.6) |

| Vomiting | 11 (11.5) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.6) |

| Traumatic fracture | 10 (10.4) | 1 (2.0) | 0 |

| EMH | 10 (10.4) | 2 (4.1) | 2 (5.3) |

| Anxiety | 10 (10.4) | 0 | 1 (2.6) |

| Palpitations | 9 (9.4) | 6 (12.2) | 4 (10.5) |

| Rhinitis | 9 (9.4) | 6 (12.2) | 0 |

| Tonsillitis | 4 (4.2) | 6 (12.2) | 1 (2.6) |

| Patients with ≥1 . | Luspatercept (N = 96) . | Placebo (N = 49) . | Crossover∗ (N = 38) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| TEAE | 96 (100) | 48 (98.0) | 38 (100) |

| Grade ≥3 TEAE | 33 (34.4) | 15 (30.6) | 7 (18.4) |

| Serious TEAE | 23 (24.0) | 13 (26.5) | 3 (7.9) |

| TEAE leading to dose delay | 47 (49.0) | 11 (22.4) | 18 (47.4) |

| TEAE leading to dose reduction | 11 (11.5) | 0 | 2 (5.3) |

| TEAE leading to study drug discontinuation | 5 (5.2) | 4 (8.2) | 3 (7.9) |

| TEAE leading to death | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Treatment-related TEAE | 79 (82.3) | 18 (36.7) | 29 (76.3) |

| Treatment-related grade ≥3 TEAE | 12 (12.5) | 0 | 2 (5.3) |

| Treatment-related serious TEAE | 4 (4.2) | 0 | 1 (2.6) |

| Treatment-related TEAE leading to dose delay | 10 (10.4) | 0 | 3 (7.9) |

| Treatment-related TEAE leading to dose reduction | 11 (11.5) | 0 | 2 (5.3) |

| Treatment-related TEAE leading to study drug discontinuation | 4 (4.2) | 0 | 2 (5.3) |

| Treatment-related TEAE leading to death | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TEAEs occurring in ≥10% of patients in either treatment arm | |||

| Headache | 44 (45.8) | 10 (20.4) | 10 (26.3) |

| Bone pain | 42 (43.8) | 3 (6.1) | 8 (21.1) |

| Back pain | 38 (39.6) | 6 (12.2) | 14 (36.8) |

| Arthralgia | 37 (38.5) | 8 (16.3) | 11 (28.9) |

| COVID-19 | 34 (35.4)† | 0 | 15 (39.5) |

| Pyrexia | 30 (31.3) | 9 (18.4) | 11 (28.9) |

| Pain in extremity | 29 (30.2) | 5 (10.2) | 6 (15.8) |

| Diarrhea | 25 (26.0) | 6 (12.2) | 5 (13.2) |

| Influenza-like illness | 25 (26.0) | 3 (6.1) | 2 (5.3) |

| Cough | 24 (25.0) | 1 (2.0) | 2 (5.3) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 23 (24.0) | 11 (22.4) | 1 (2.6) |

| Fatigue | 23 (24.0) | 10 (20.4) | 8 (21.1) |

| Prehypertension | 23 (24.0) | 7 (14.3) | 3 (7.9) |

| Oropharyngeal pain | 23 (24.0) | 6 (12.2) | 1 (2.6) |

| Pharyngitis | 21 (21.9) | 7 (14.3) | 1 (2.6) |

| Hypertension | 21 (21.9) | 1 (2.0) | 7 (18.4) |

| Asthenia | 19 (19.8) | 5 (10.2) | 0 |

| Dizziness | 19 (19.8) | 4 (8.2) | 3 (7.9) |

| Abdominal pain | 18 (18.8) | 6 (12.2) | 4 (10.5) |

| Dyspepsia | 18 (18.8) | 2 (4.1) | 3 (7.9) |

| Immunization reaction | 18 (18.8) | 0 | 5 (13.2) |

| Myalgia | 16 (16.7) | 5 (10.2) | 3 (7.9) |

| Influenza | 15 (15.6) | 5 (10.2) | 1 (2.6) |

| Abdominal pain upper | 15 (15.6) | 3 (6.1) | 5 (13.2) |

| Toothache | 15 (15.6) | 1 (2.0) | 0 |

| Nausea | 14 (14.6) | 6 (12.2) | 1 (2.6) |

| Iron overload | 14 (14.6) | 5 (10.2) | 0 |

| Insomnia | 14 (14.6) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.6) |

| Menstruation irregular | 13 (13.5) | 3 (6.1) | 2 (5.3) |

| Gastroenteritis | 12 (12.5) | 4 (8.2) | 2 (5.3) |

| Neck pain | 12 (12.5) | 2 (4.1) | 1 (2.6) |

| Epistaxis | 12 (12.5) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.6) |

| Vomiting | 11 (11.5) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.6) |

| Traumatic fracture | 10 (10.4) | 1 (2.0) | 0 |

| EMH | 10 (10.4) | 2 (4.1) | 2 (5.3) |

| Anxiety | 10 (10.4) | 0 | 1 (2.6) |

| Palpitations | 9 (9.4) | 6 (12.2) | 4 (10.5) |

| Rhinitis | 9 (9.4) | 6 (12.2) | 0 |

| Tonsillitis | 4 (4.2) | 6 (12.2) | 1 (2.6) |

Data are given as n (%).

Patients who crossed over from placebo to luspatercept.

The excess of COVID-19 cases among patients who received luspatercept was likely due to completion of the double-blind treatment phase by most patients randomized to placebo before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Tracked AEs of clinical relevance were bone pain and hypertension (Table 2). Treatment-emergent bone pain occurred in 42 (43.8%) patients in the luspatercept group, 3 (6.1%) in the placebo group, and 8 (21.1%) in the crossover group. The median (range) times to first onset of bone pain were 3.0 (1.0-1397), 40.0 (25.0-67.0), and 4.0 (1.0-334.0) days, respectively. Most treatment-emergent bone pain events were grade 1 or 2 in severity, but 3 patients in the luspatercept group had nonserious grade 3 events that resolved within 6 to 15 days from onset. Treatment-related bone pain AEs led to dose reductions in 4 patients in the luspatercept group. One patient in the crossover group discontinued treatment due to a bone pain event.

TEAEs of clinical relevance and special interest

| TEAE . | Luspatercept (N = 96) . | Placebo (N = 49) . | Crossover∗ (N = 38) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All grades . | Grade 3/4 . | All grades . | Grade 3/4 . | All grades . | Grade 3/4 . | |

| TEAEs of clinical relevance | ||||||

| Hypertension† | 21 (21.9) | 3 (3.1) | 1 (2.0) | 0 | 7 (18.4) | 0 |

| Bone pain‡ | 42 (43.8) | 3 (3.1) | 3 (6.1) | 0 | 8 (21.1) | 0 |

| TEAEs of special interest | ||||||

| TEE | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 0 | 2 (5.3) | 1 (2.6) |

| EMH | 10 (10.4) | 0 | 2 (4.1) | 1 (2.0) | 2 (5.3) | 0 |

| Malignancies | 0 | 0 | 2 (4.1) | 2 (4.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Premalignant disorders | 2 (2.1) | 0 | 1 (2.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TEAE . | Luspatercept (N = 96) . | Placebo (N = 49) . | Crossover∗ (N = 38) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All grades . | Grade 3/4 . | All grades . | Grade 3/4 . | All grades . | Grade 3/4 . | |

| TEAEs of clinical relevance | ||||||

| Hypertension† | 21 (21.9) | 3 (3.1) | 1 (2.0) | 0 | 7 (18.4) | 0 |

| Bone pain‡ | 42 (43.8) | 3 (3.1) | 3 (6.1) | 0 | 8 (21.1) | 0 |

| TEAEs of special interest | ||||||

| TEE | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 0 | 2 (5.3) | 1 (2.6) |

| EMH | 10 (10.4) | 0 | 2 (4.1) | 1 (2.0) | 2 (5.3) | 0 |

| Malignancies | 0 | 0 | 2 (4.1) | 2 (4.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Premalignant disorders | 2 (2.1) | 0 | 1 (2.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Data are given as n (%).

Patients who crossed over from placebo to luspatercept.

Includes only the preferred term hypertension.

Includes only the preferred term bone pain.

Treatment-emergent hypertension was reported in 21 (21.9%) patients in the luspatercept group, 1 (2.0%) in the placebo group, and 7 (18.4%) in the crossover group. Treatment-related hypertension was reported in 14 (14.6%), 0, and 2 (5.3%) patients, respectively. Three patients in the luspatercept group had grade 3 treatment-emergent, treatment-related, nonserious hypertension, of which 2 improved to ongoing grade 1 or 2, and 1 improved to ongoing grade 1 prehypertension.

TEAEs of special interest included EMH, TEEs, malignancies, and premalignant disorders (Table 2). EMH cases reported as TEAEs occurred in 10 (10.4%), 2 (4.1%), and 2 (5.3%) patients in the luspatercept, placebo, and crossover groups, respectively (supplemental Table 2). Twelve of these events were nonserious and grade 1 or 2 in severity, and most (11/14) cases were asymptomatic. One patient in the luspatercept group with a history of EMH (previously treated with hydroxyurea prior to study treatment) reported serious grade 4 spinal cord compression, resulting in drug discontinuation and treatment with laminectomy, dexamethasone, heparin, and transfusions, and improved to a nonserious grade 2 event (preferred term was updated from spine compression to EMH). One patient in the placebo arm had serious grade 3 mediastinal EMH with compression complications, which required thoracotomy for EMH mass resection. Of the 14 patients who reported TEAEs of EMH, 7 had EMH at baseline (6 luspatercept recipients and 1 placebo recipient). Five of these patients had subsequent evaluation(s) for EMH during the trial, and masses remained stable in size for all 5 patients. Of note, EMH assessment by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at baseline was required only for patients who had a prior EMH diagnosis.

TEEs occurred in 2 (2.1%), 0, and 2 (5.3%) patients in the luspatercept, placebo, and crossover groups, respectively. In the luspatercept group, 1 patient had a serious, suspected treatment-related, grade 3 myocardial infarction. This patient had several TEE risk factors, including iron overload, thrombocytosis, and splenectomy. The other patient had a grade 1 splenic infarction (considered unrelated to treatment by the investigator). In the crossover group, 1 patient developed 2 pulmonary emboli (1 grade 3 and 1 grade 2); the grade 2 event was suspected to be treatment related. This patient also had TEE risk factors (iron overload and splenectomy). The other patient in the crossover group had grade 2 superficial vein thrombosis, which was considered unrelated to treatment by the investigator.

Malignancies were reported only in the placebo arm: 1 patient had a serious grade 4 diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and 1 had a serious grade 3 hepatocellular carcinoma. Three premalignant events were reported in 2 patients in the luspatercept arm (grade 2 colon adenoma and grade 1 hypergammaglobulinemia) and in 1 patient in the placebo arm (grade 2 anal polyp), all of which were nonserious and considered unrelated to study drug.

Discussion

In recent years, understanding of NTDT disease burden and complications has increased, leading to recognition of the importance of chronic anemia management in this population. These findings from the BEYOND study, which include an additional 26 months (∼2.2 years) of follow-up from the primary analysis,23 show the rapid increase in mean hemoglobin levels in patients with NTDT treated with luspatercept during the first 12 weeks was sustained up to week 240 (∼4.6 years). In addition to fixed interval analyses, clinical benefit with luspatercept was also observed when analyzing data by any 12- or 24-week intervals. This indicates that long-term luspatercept treatment provides clinical benefit exhibited by durable improvements in hemoglobin levels, therefore alleviating anemia in patients with NTDT, in agreement with the first clinical study of luspatercept in β-thalassemia.26

Patients with NTDT experience a range of clinical complications and increased mortality due to suboptimal management of anemia, further underscoring the need for safe and effective treatments. Several studies have shown increases in hemoglobin levels can potentially reduce the odds of developing morbidities in patients with NTDT,9-12 and are associated with significantly lower mortality in regularly transfused patients with NTDT compared with those who receive transfusions sporadically.7 The importance of increased pretransfusion hemoglobin levels was also recently shown for patients with TDT.27,28 Nevertheless, some NTDT-associated complications take years to develop; therefore, longer follow-up or real-world data are needed to assess fully how luspatercept-mediated hemoglobin increases translate into reduction of long-term complications or mortality.29 A long-term follow-up study evaluating the safety of luspatercept is underway (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04064060).

Although patients with NTDT do not require RBC transfusions, except under specific circumstances, studies have shown RBC transfusions for patients with NTDT effectively improve hemoglobin levels, decrease rates of morbidities, and slow disease progression.7,30 Even so, frequent RBC transfusions over a long period may lead to transfusion-dependence, “phenoconversion” from NTDT to TDT, and increased risk of secondary iron overload and resulting cardiac and liver complications.31-33 In the BEYOND study, luspatercept significantly increased the time to first RBC transfusion and reduced patients’ transfusion needs, with the differences in favor of luspatercept becoming greater with the analysis duration.

As of study completion, the proportions of patients who experienced ≥1 TEAE, grade ≥3 TEAEs, and serious TEAEs were similar in the luspatercept and placebo arms, despite the much longer treatment exposure for luspatercept (202.8 weeks vs 61.1 weeks for placebo) and no adjusting of the TEAE incidence rates for exposure. Although incidence rates of bone pain or hypertension were greater in patients treated with luspatercept, the TEAEs were mostly mild and manageable. Management of patients with TDT receiving luspatercept, including addressing TEAEs, has been previously described.34 Treatment discontinuations due to TEAEs remained low during the study, there were no deaths related to luspatercept treatment, and no treatment-emergent malignancies detected among patients receiving luspatercept.

EMH is a common condition related to β-thalassemia, which can result in complications, such as neural compression due to masses in the paraspinal location. Development of hematopoietic masses in the spine occurs in 11% to 15% of patients with EMH; however, >80% of cases remain asymptomatic, and are discovered incidentally or reported in prospective observation as part of the disease’s natural history.2,35 Although EMH is more prevalent in patients with NTDT than TDT, rates may vary.2 Most EMH events reported in the BEYOND study were of minor clinical significance, and incidence rates aligned with those reported in the literature,6,36,37 but there was a risk of underdiagnosis due to lack of systematic MRI screening at baseline (only patients with prior history of EMH masses had MRI evaluation). It is important to note that patient crossover from placebo to luspatercept introduced a bias between treatment exposure and time to event, preventing informative comparisons between EMH incidence rates reported in the 3 groups. Clinical guidelines, such as those from the Thalassaemia International Federation, recommend that patients with NTDT should be closely monitored for EMH and their anemia actively managed to minimize EMH risk.2 Evaluation for EMH should occur at initiation and during treatment, and patients should be monitored for symptoms or complications of EMH.2,38

NTDT is a hypercoagulable state with an increased risk for TEEs. Of the 4 patients treated with luspatercept with reported treatment-emergent TEEs, all had >1 TEE risk factor, including splenectomy (3 patients), which is known to increase risk of TEE occurrence.2,39 A comprehensive evaluation of the underlying disease and other inherited or acquired thrombosis risk factors in patients with NTDT is essential for informed management and TEE prophylaxis. Notably, incidence rates of TEEs in patients with NTDT in the BEYOND study were lower than those reported in patients with TDT in BELIEVE (TEEs occurred in 3.6% and 0.9% of patients in the luspatercept and placebo arms, respectively).22 These observations suggest TEEs are unlikely to be related to luspatercept, but are possibly due to an indirect effect of decreased transfusion requirements and higher numbers of prothrombotic endogenous RBCs in patients with TDT. However, this interpretation requires further evaluation.

In the primary analysis, luspatercept treatment in patients with NTDT provided a rapid and sustained increase in hemoglobin levels, accompanied by an improvement in NTDT-PRO T/W domain score, which became more pronounced over time.23,40 The NTDT-PRO T/W outcomes at study completion show sustained symptom improvement, and support luspatercept as an important treatment option for patients with NTDT. Full results of PRO analyses will be reported separately.

In summary, luspatercept demonstrated robust efficacy by increasing mean hemoglobin levels in patients with NTDT, which were sustained for up to ∼4.6 years with a consistent safety profile. Luspatercept is, therefore, a valuable treatment option for NTDT-associated anemia.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the patients, families, and clinical study teams who participated in the trial. The authors thank Ana Carolina Giuseppi for her role in accessing and verifying the data; and Christopher Pelligra and Matt Dyer for patient-reported outcome data analysis and interpretation.

This study was supported by Celgene, a Bristol Myers Squibb Company, in collaboration with Acceleron Pharma Inc, a wholly owned subsidiary of Merck & Co, Inc, Rahway, NJ. Writing and editorial assistance were provided by Karolina Lech, of Excerpta Medica, funded by Bristol Myers Squibb.

The funders were involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing of the report.

Authorship

Contribution: A.T.T., the chief investigator, and M.D.C. designed the trial; A.T.T., V.V., A.K., S.P., P.R., J.B.P., T.D.C., G.L.F., and M.D.C. contributed to data acquisition; O.E., R.P., W.-L.K., Y.L., M.R., R.W., and L.M.B. accessed and verified the data; W.-L.K. and Y.L. performed the statistical analysis; and all authors contributed to data interpretation, carefully reviewed and approved the final version, had full access to all the data in the study, and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.T.T. reports consultancy fees and research support from Agios Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novo Nordisk, Pharmacosmos, and Vifor Pharma. V.V. reports grants or contracts from Agios Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers Squibb, DisperSol Technologies LLC, The Government Pharmaceutical Organization, Ionis Pharmaceuticals Inc, Novartis, Pharmacosmos, and Vifor Pharma; and consulting fees from Agios Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers Squibb, DisperSol Technologies LLC, Ionis Pharmaceuticals Inc, Novartis, Pharmacosmos, and Vifor Pharma. A.K. reports grants or contracts from Bristol Myers Squibb; honoraria/payment for lectures, presentations, speakers bureau, manuscript writing, or education events from Agios Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers Squibb, Chiesi, and Vertex; travel support from Bristol Myers Squibb; and participation on a data safety monitoring board or an advisory board for Agios Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers Squibb, Vertex, and Vifor Pharma. S.P. reports honoraria/payment for lectures, presentations, speakers bureau, manuscript writing, or education events from Bristol Myers Squibb. P.R. reports honoraria/payment for lectures, presentations, speakers bureau, manuscript writing, or education events from Agios Pharmaceuticals and Bristol Myers Squibb; receiving travel support from Agios Pharmaceuticals; and participation on a data safety monitoring board or an advisory board for Agios Pharmaceuticals and Bristol Myers Squibb. J.B.P. reports consultancy and research funding from Silence Therapeutics; and honoraria for advisory boards from Agios Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Vifor Pharma. T.D.C. reports consulting fees from Agios Pharmaceuticals, Chiesi, and Celgene/Bristol Myers Squibb. G.L.F. reports honoraria/payment for lectures, presentations, speakers bureau, manuscript writing, or education events from Agios Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Vertex; participation on a data safety monitoring board or an advisory board for Garuda Pharmaceuticals; and leadership or fiduciary role for Anemia Foundation. K.M.M. reports grants or contracts from Agios Pharmaceuticals and Pharmacosmos; and consultancy fees from Agios Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers Squibb, CRISPR Therapeutics, Novartis, Pharmacosmos, and Vifor Pharma. O.E. reports being employed by Bristol Myers Squibb. R.P. and L.M.B. report support for the present manuscript, being employed by and owning stock in Bristol Myers Squibb. W.-L.K. reports being employed by Bristol Myers Squibb. Y.L. and M.R. report being employed by and owning stock in Bristol Myers Squibb. M.D.C. reports support for the present manuscript from Agios Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers Squibb, Sanofi, and Vertex; honoraria/payment for lectures, presentations, speakers bureau, manuscript writing, or education events from Agios Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Sanofi; travel support from Sanofi; and participation on a data safety monitoring board or an advisory board for Sanofi, Silence Therapeutics, and Vertex. R.W. declares no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for R.W. is MediGo Consulting, LLC, Princeton, NJ.

Correspondence: Ali T. Taher, Department of Internal Medicine, American University of Beirut Medical Center, Halim and Aida Daniel ACC, 4th floor, Abdelaziz St, Hamra, Beirut 1107 2020, Lebanon; email: ataher@aub.edu.lb.

References

Author notes

Bristol Myers Squibb will honor legitimate requests for our clinical trial data from qualified researchers with a clearly defined scientific objective. We consider data-sharing requests for phase 2 to 4 interventional clinical trials that completed on or after 1 January 2008. In addition, primary results from these trials must have been published in peer-reviewed journals, and the medicines or indications approved in the United States, European Union, and other designated markets. Sharing is also subject to protection of patient privacy and respect for the patient’s informed consent. Data considered for sharing may include nonidentifiable patient-level and study-level clinical trial data, and full clinical study reports and protocols. Bristol Myers Squibb reserves the right to update and change criteria at any time. Other criteria may apply, for details please visit Bristol Myers Squibb at https://vivli.org/ourmember/bristol-myers-squibb/.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![Patient disposition. In the luspatercept (including crossover) group and placebo group, treatment discontinuations occurred in 39 of 134 (29.1%) and 31 of 49 (63.3%) patients, respectively. The main reasons for study drug discontinuation in the luspatercept and placebo groups, respectively, were lack of efficacy (2/134 [1.5%] and 17/49 [34.7%]), withdrawal by patient (23/134 [17.2%] and 10/49 [20.4%]), and AEs (8/134 [6.0%] and 4/49 [8.2%]). AEs leading to study drug discontinuation in patients receiving luspatercept (including crossover) were arthralgia, hemolytic anemia, and lupus-like syndrome (1 patient); spinal cord compression and EMH masses (1 patient); pulmonary arterial hypertension (1 patient); myocardial infarction (1 patient); transient ischemic attack (1 patient); back pain, bone pain, and palpitations (1 patient each). In the placebo group, AEs that led to study drug discontinuation were fatigue and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (1 patient), and hypotension, asthenia, and hepatocellular carcinoma (1 patient each). ∗As of last patient last visit date (28 November 2022).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/9/23/10.1182_bloodadvances.2025016554/2/m_blooda_adv-2025-016554-gr1.jpeg?Expires=1770925227&Signature=ozaFanSIwejynRFIXcAp1X4KVC22iVEmyVOxymRru929YuLjBuh3ytQ4g5evZ4OrRRX-cAnXPzAUjsnBoH1RJUA949pfjApK540PfGlyx4sHtKTTaThO1xRrUrBzO7oezKp0wWBuU6uB1fOZEftWqxlRxp0gTMWuL6~38fNvWUagBruh0kLlvzd~FRVQ4FZyu289J9U-25GPVh5sWabNUZV0uqIuJqOXBqBTPccnTmY1HYPXyUrAc~UlucbXgaHp5ZoTUd2ZumLQqwY3HAMhuOXxqa7VT17Gv1mgDyJkFDUnOpzKad-h5NkHOtTRy6MXJZxHXxb-GPp2lAZc7K4L2A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)