Key Points

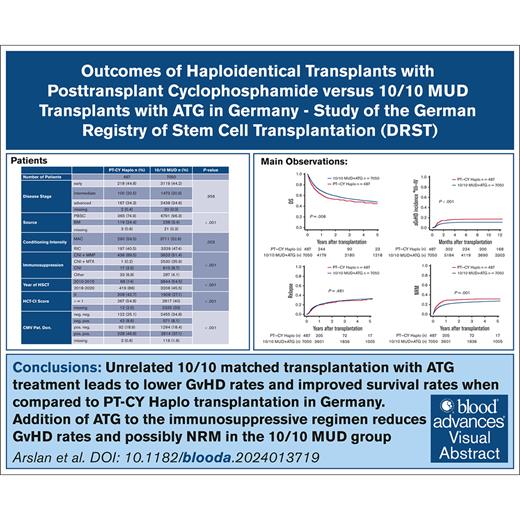

Five-year OS and DFS were significantly lower in PT-CY Haplo transplantation than 10/10 MUD transplantation with ATG in a German cohort.

10/10 MUD transplantation with ATG provides higher GRFS and lower aGVHD, cGVHD, and nonrelapse mortality (NRM) than PT-CY Haplo in a German cohort.

Visual Abstract

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) is the best curative treatment modality for many malignant hematologic disorders. In the absence of a matched related donor, matched unrelated donors (MUDs) and haploidentical donors are the most important stem cell sources. In this registry-based retrospective study, we compared the outcomes of allo-HSCTs from 10/10 MUDs with antithymocyte globulin (ATG)–based regimens (n = 7050) vs haploidentical transplants (Haplo-Tx) using posttransplant cyclophosphamide (PT-CY Haplo; n = 487) in adult patients with hematologic malignancies between 2010 and 2020. Cox proportional hazard-and competing risks regression models were formed to compare the outcomes. Overall survival (OS), Disease-free survival (DFS), and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD)–free and relapse-free survival (GRFS) were superior for 10/10 MUDs (OS [hazard ratio (HR), 1.27; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.10-1.47; P = .001]; DFS [HR, 1.17; CI, 1.02-1.34; P = .022]; GRFS [HR, 1.34; CI, 1.19-1.50; P < .001]). The risk of acute GVHD (aGVHD) grade 2 to 4, aGVHD grade 3 to 4, and chronic GVHD (cGVHD) was higher in the PT-CY Haplo group than the 10/10 MUD group (aGVHD grade 2-4 [HR, 1.46; CI, 1.25-1.71; P < .001]; aGVHD grade 3-4 [HR, 1.74; CI, 1.37- 2.20; P < .001]; cGVHD [HR, 1.30; CI, 1.11-1.51; P = .001]). A lower incidence of relapse was observed in the PT-CY Haplo group (relapse: HR, 0.83; CI, 0.69-0.99; P = .038). Unrelated 10/10 matched transplantation with ATG leads to lower GVHD rates and improved survival rates compared with PT-CY Haplo transplantation in Germany.

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) is a well-defined and established procedure for the curative treatment of malignant and nonmalignant hematologic diseases.1 One challenge is the selection of the best donor. Although matched related donors (MRD) and matched unrelated donors (MUD) are the preferred choices, lack of a suitable matched donor has resulted in the search for alternative donors. Only ∼30% of the patients who are allo-HSCT planned have a suitable MRD, and 25% of the patients among White Europeans lack a MUD. The likelihood of lacking a MUD in other racial and ethnic groups is even higher.2 Currently, the possible alternative stem cell sources are HLA-mismatched unrelated donor, HLA-haploidentical donor, or umbilical cord blood units.3 In patients without an available matched donor, donor selection is made according to criteria such as patient characteristics, type of disease, transplant regimen, the accessibility of donor, and the experience of the center.4 Over the last recent years, the use of posttransplant cyclophosphamide (PT-CY)–based regimens for the prophylaxis of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) with its associated ease of donor access and availability has led to rapidly increasing numbers of haploidentical transplants (Haplo-Tx) worldwide.5 According to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) database published in 2020, mismatched related transplantation, which reflect the increased use of Haplo-Tx, is the only category other than MUD that increased in the last years, whereas transplants from other donor sources are stable or declining.6

Although the mechanism of action of cyclophosphamide after transplantation is not fully understood, with regard to our knowledge, PT-CY functions by reducing or impairing activated and alloreactive donor T cells as well as upregulating regulatory T cells.7 A recent study also explained that myeloid-derived suppressor cells, as an important mediator of T-cell function, are upregulated by PT-CY. This may be reducing the risk of GVHD and may explain how Haplo-Tx and PT-CY in combination work with acceptable outcomes.8 In recent studies, Haplo-Tx with PT-CY has shown comparable survival outcomes, acute GVHD (aGVHD), chronic GVHD (cGVHD) and engraftment rates compared to MUDs in various types of hematologic malignancies and with different conditioning regimens.9-14 Although the number of studies are increasing over time, there are still not enough multicenter real-life data with a large amount of numbers directly comparing Haplo-Tx with PT-CY prophylaxis with MUD transplants with traditional GVHD prophylaxis. With the aim to aid answering the question whether Haplo-Tx may be an alternative to MUD transplantation in patients without a MRD and to better define the position of Haplo-Tx within the algorithm of donor selection, we performed a registry-based observational study using data from the German Registry for Stem Cell Transplantation (DRST).

Patients and methods

Patients

Adult patients having received a first allo-HSCT for a malignant disease of the hematopoietic system between 2010 and 2020 were eligible for this analysis. Graft sources were peripheral blood stem cells (PBSCs) and bone marrow (BM). The Haplo-Tx group consists of patients who received a mismatched related transplant with post-Tx cyclophosphamide as a component of the immunosuppressive regimen. The reference MUD group consists of 10/10 HLA matched transplantations, in which a high-resolution HLA-typing result was documented in patient and donor for the loci HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1, and -DQB1. All of the patients in this group had received a GVHD prophylaxis including ATG. The transplantations were performed between 2010 and 2020.

Data source and study design

The data for this study were provided by the DRST, which forms a subset of the database of Europian Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) for German patients. Follow-up data are collected by the transplant centers on the day of transplantation, after 100 days, and at yearly intervals later on. Study design is a retrospective observational registry analysis.

Definitions

Disease stage definitions were used as described in the report defining the EBMT risk score.15 HLA match was defined as identical protein sequence within the antigen recognition domain of each HLA allele for the loci HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1, and -DQB1 in patients and donors (10/10 match). Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time to death. Disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as the time to death or relapse; GVHD/relapse-free survival was defined as the number of days between transplantation and aGVHD grades 3 to 4/severe cGVHD/death/relapse, whichever occurred first.16 Relapse was defined as the number of days between transplantation and relapse, treating death from any other cause as a competing event (CE), called nonrelapse mortality (NRM). Grades 2 to 4 aGVHD and cGVHD were assigned according to previously described criteria.17,18 Incidence of aGVHD was defined as the number of days between transplantation and the occurrence of aGVHD grades 2 to 4 or 3 to 4, with relapse/death from other causes as a CE. Incidence of cGVHD was defined as the number of days between transplantation and the occurrence of cGVHD, with relapse/death as a CE. Neutrophil engraftment was defined as patients achieving neutrophil counts ≥0.5 × 109/L for 3 consecutive days, with early death in the observation period before engraftment treated as competing risk. Patients without the event of interest or a CE during their follow-up period were censored at the time of the last contact.

Statistical analysis

Differences between groups in descriptive statistics were tested using the Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables. For univariate survival analysis, the Kaplan-Meier method with log-rank significance testing was used. For competing end points, cumulative incidences were calculated with competing risk statistics. Cox proportional hazard models were used for multivariate analysis. The baseline variables and transplantation characteristics including patient age, diagnosis, EBMT stage, center, Karnofsky performance score (KPS), graft source, and previous autologous transplantation were included as covariates. Additionally, the variables including year of HSCT, female donor to male patient, donor age, Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation-spesific Comorbidity Index (HCT-CI) score, patient/donor cytomegalovirus status, and total body irradiation were included and analyzed. Missing values were treated as a separate category. Models were checked for the proportional hazards assumption. Only KPS showed a time-dependent effect present early after transplantation. The significance level was set to a P value of .05. A sensitivity analysis with a 1:4 propensity score matching was performed for the survival end points. The disease- and treatment-related matching variables were patient age, diagnosis, center, disease stage, KPS, stem cell source, previous autologous transplantation, conditioning intensity, and donor age.

This study was approved by the ethical review board of the University of Ulm (application number 227/21). All patients gave written consent for the registration of their follow-up data in the EBMT database and for the analysis of these data in a scientific context.

Results

Overall, 7537 transplantations were included in this analysis. The PT-CY Haplo group includes 487, and the remaining 7050 transplantations represent the 10/10 MUD group. Demographic characteristics of the cohorts are listed in Table 1. Differences between the patient and transplantation characteristics were found for all variables except EBMT stage and previous HSCT. Patients of the 10/10 MUD group received PBSC transplants (96.3%) more often than patients in the PT-CY Haplo group (74.9%). The predominant conditioning regimen was myeloablative conditioning (MAC) regimen for both groups, but patients in the PT-CY Haplo group are more likely to receive MAC (59.5% vs 52.6%). Approximately 50% of transplants in the 10/10 MUD group were performed between 2015 and 2020, compared with 86% in PT-CY Haplo patients.

Cohort characteristics

| . | PT-CY Haplo, n (%) . | 10/10 MUD, n (%) . | Total . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 487 | 7050 | 7537 | |

| Patient age, y | <.001 | |||

| 18-19 | 10 (2.1) | 73 (1) | 83 | |

| 20-29 | 48 (9.9) | 385 (5.5) | 433 | |

| 30-39 | 36 (7.4) | 457 (6.5) | 493 | |

| 40-49 | 72 (14.8) | 1053 (14.9) | 1125 | |

| 50-59 | 126 (25.9) | 2088 (29.6) | 2214 | |

| 60-69 | 166 (34.1) | 2394 (34) | 2560 | |

| 70-79 | 29 (6) | 600 (8.5) | 629 | |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| AML | 233 (47.8) | 2926 (41.5) | 3159 | <.001 |

| MDS/MPN | 74 (15.2) | 1710 (24.3) | 1784 | |

| NHL | 65 (13.3) | 640 (9.1) | 705 | |

| ALL | 57 (11.7) | 575 (8.2) | 632 | |

| MM | 19 (3.9) | 432 (6.1) | 451 | |

| SecAL | 17 (3.5) | 319 (4.5) | 336 | |

| CLL | 2 (0.4) | 165 (2.3) | 167 | |

| CML | 7 (1.4) | 149 (2.1) | 156 | |

| AL | 5 (1) | 89 (1.3) | 94 | |

| HL | 8 (1.6) | 45 (0.6) | 53 | |

| Disease stage | ||||

| Early | 218 (44.8) | 3119 (44.2) | 3337 | .956 |

| Intermediate | 100 (20.5) | 1473 (20.9) | 1573 | |

| Advanced | 167 (34.3) | 2438 (34.6) | 2605 | |

| Missing | 2 (0.4) | 20 (0.3) | 22 | |

| KPS | ||||

| ≥80 | 434 (89.1) | 6178 (87.6) | 6612 | .011 |

| <80 | 36 (7.4) | 407 (5.8) | 443 | |

| Missing | 17 (3.5) | 465 (6.6) | 482 | |

| Source | ||||

| PBSC | 365 (74.9) | 6791 (96.3) | 7156 | <.001 |

| BM | 119 (24.4) | 238 (3.4) | 357 | |

| Missing | 3 (0.6) | 21 (0.3) | 24 | |

| Previous auto-HSCT | ||||

| Yes | 63 (12.9) | 829 (11.8) | 892 | .481 |

| No | 424 (87.1) | 6221 (88.2) | 6645 | |

| Conditioning intensity | ||||

| MAC | 290 (59.5) | 3711 (52.6) | 4001 | .003 |

| RIC | 197 (40.5) | 3339 (47.4) | 3536 | |

| Immunosuppression | ||||

| CNI + MMF | 436 (89.5) | 3623 (51.4) | 627 | <.001 |

| CNI + MTX | 1 (0.2) | 2530 (35.9) | 4057 | |

| CNI | 17 (3.5) | 610 (8.7) | 2531 | |

| Other | 33 (6.8) | 287 (4.1) | 320 | |

| Year of HSCT | ||||

| 2010-2015 | 68 (14) | 3844 (54.5) | 3912 | <.001 |

| 2016-2020 | 419 (86) | 3206 (45.5) | 3625 | |

| Sex mismatch | ||||

| Yes | 109 (22.4) | 649 (9.2) | 758 | <.001 |

| No | 376 (77.2) | 6066 (86) | 6442 | |

| Missing | 2 (0.4) | 335 (4.8) | 337 | |

| Donor age, y | ||||

| 0-19 | 26 (5.3) | 164 (2.3) | 190 | <.001 |

| 20-29 | 110 (22.6) | 1753 (24.9) | 1863 | |

| 30-39 | 149 (30.6) | 1182 (16.8) | 1331 | |

| 40-49 | 106 (21.8) | 617 (8.8) | 723 | |

| 50-59 | 56 (11.5) | 208 (3) | 264 | |

| 60-99 | 16 (3.3) | 12 (0.2) | 28 | |

| Missing | 24 (4.9) | 3114 (44.2) | 3138 | |

| HCT-CI score | ||||

| 0 | 208 (42.7) | 1908 (27.1) | 2116 | <.001 |

| ≥1 | 267 (54.8) | 2817 (40) | 3084 | |

| Missing | 12 (2.5) | 2325 (33) | 2337 | |

| CMV Pat. Don. | ||||

| Neg. neg. | 122 (25.1) | 2455 (34.8) | 2577 | <.001 |

| Neg. pos. | 42 (8.6) | 571 (8.1) | 613 | |

| Pos. neg. | 92 (18.9) | 1294 (18.4) | 1386 | |

| Pos. pos. | 228 (46.8) | 2614 (37.1) | 2842 | |

| Missing | 3 (0.6) | 116 (1.6) | 119 | |

| TBI | ||||

| Yes | 111 (22.8) | 1634 (23.2) | 1745 | <.001 |

| No | 373 (76.6) | 5412 (76.8) | 5785 | |

| Missing | 3 (0.6) | 4 (0.1) | 7 |

| . | PT-CY Haplo, n (%) . | 10/10 MUD, n (%) . | Total . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 487 | 7050 | 7537 | |

| Patient age, y | <.001 | |||

| 18-19 | 10 (2.1) | 73 (1) | 83 | |

| 20-29 | 48 (9.9) | 385 (5.5) | 433 | |

| 30-39 | 36 (7.4) | 457 (6.5) | 493 | |

| 40-49 | 72 (14.8) | 1053 (14.9) | 1125 | |

| 50-59 | 126 (25.9) | 2088 (29.6) | 2214 | |

| 60-69 | 166 (34.1) | 2394 (34) | 2560 | |

| 70-79 | 29 (6) | 600 (8.5) | 629 | |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| AML | 233 (47.8) | 2926 (41.5) | 3159 | <.001 |

| MDS/MPN | 74 (15.2) | 1710 (24.3) | 1784 | |

| NHL | 65 (13.3) | 640 (9.1) | 705 | |

| ALL | 57 (11.7) | 575 (8.2) | 632 | |

| MM | 19 (3.9) | 432 (6.1) | 451 | |

| SecAL | 17 (3.5) | 319 (4.5) | 336 | |

| CLL | 2 (0.4) | 165 (2.3) | 167 | |

| CML | 7 (1.4) | 149 (2.1) | 156 | |

| AL | 5 (1) | 89 (1.3) | 94 | |

| HL | 8 (1.6) | 45 (0.6) | 53 | |

| Disease stage | ||||

| Early | 218 (44.8) | 3119 (44.2) | 3337 | .956 |

| Intermediate | 100 (20.5) | 1473 (20.9) | 1573 | |

| Advanced | 167 (34.3) | 2438 (34.6) | 2605 | |

| Missing | 2 (0.4) | 20 (0.3) | 22 | |

| KPS | ||||

| ≥80 | 434 (89.1) | 6178 (87.6) | 6612 | .011 |

| <80 | 36 (7.4) | 407 (5.8) | 443 | |

| Missing | 17 (3.5) | 465 (6.6) | 482 | |

| Source | ||||

| PBSC | 365 (74.9) | 6791 (96.3) | 7156 | <.001 |

| BM | 119 (24.4) | 238 (3.4) | 357 | |

| Missing | 3 (0.6) | 21 (0.3) | 24 | |

| Previous auto-HSCT | ||||

| Yes | 63 (12.9) | 829 (11.8) | 892 | .481 |

| No | 424 (87.1) | 6221 (88.2) | 6645 | |

| Conditioning intensity | ||||

| MAC | 290 (59.5) | 3711 (52.6) | 4001 | .003 |

| RIC | 197 (40.5) | 3339 (47.4) | 3536 | |

| Immunosuppression | ||||

| CNI + MMF | 436 (89.5) | 3623 (51.4) | 627 | <.001 |

| CNI + MTX | 1 (0.2) | 2530 (35.9) | 4057 | |

| CNI | 17 (3.5) | 610 (8.7) | 2531 | |

| Other | 33 (6.8) | 287 (4.1) | 320 | |

| Year of HSCT | ||||

| 2010-2015 | 68 (14) | 3844 (54.5) | 3912 | <.001 |

| 2016-2020 | 419 (86) | 3206 (45.5) | 3625 | |

| Sex mismatch | ||||

| Yes | 109 (22.4) | 649 (9.2) | 758 | <.001 |

| No | 376 (77.2) | 6066 (86) | 6442 | |

| Missing | 2 (0.4) | 335 (4.8) | 337 | |

| Donor age, y | ||||

| 0-19 | 26 (5.3) | 164 (2.3) | 190 | <.001 |

| 20-29 | 110 (22.6) | 1753 (24.9) | 1863 | |

| 30-39 | 149 (30.6) | 1182 (16.8) | 1331 | |

| 40-49 | 106 (21.8) | 617 (8.8) | 723 | |

| 50-59 | 56 (11.5) | 208 (3) | 264 | |

| 60-99 | 16 (3.3) | 12 (0.2) | 28 | |

| Missing | 24 (4.9) | 3114 (44.2) | 3138 | |

| HCT-CI score | ||||

| 0 | 208 (42.7) | 1908 (27.1) | 2116 | <.001 |

| ≥1 | 267 (54.8) | 2817 (40) | 3084 | |

| Missing | 12 (2.5) | 2325 (33) | 2337 | |

| CMV Pat. Don. | ||||

| Neg. neg. | 122 (25.1) | 2455 (34.8) | 2577 | <.001 |

| Neg. pos. | 42 (8.6) | 571 (8.1) | 613 | |

| Pos. neg. | 92 (18.9) | 1294 (18.4) | 1386 | |

| Pos. pos. | 228 (46.8) | 2614 (37.1) | 2842 | |

| Missing | 3 (0.6) | 116 (1.6) | 119 | |

| TBI | ||||

| Yes | 111 (22.8) | 1634 (23.2) | 1745 | <.001 |

| No | 373 (76.6) | 5412 (76.8) | 5785 | |

| Missing | 3 (0.6) | 4 (0.1) | 7 |

AL, acute leukemia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; auto-HSCT, autologous haematopoietic stemm cell transplantation; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; CMV Pat. Don., cytomegalovirus serostatus patient and donor; CNI, calcineurin inhibitors; HCT-CI, haemopoietic cell transplantation-spesific comorbidity index; MDS/MPN, myelodysplastic syndrome/myeloproliferative neoplasm; MM, multiple myeloma; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MTX, methotrexate; neg., negative; NHL, non hodgkin`s lymphoma; pos., positive; TBI, total body irradiation.

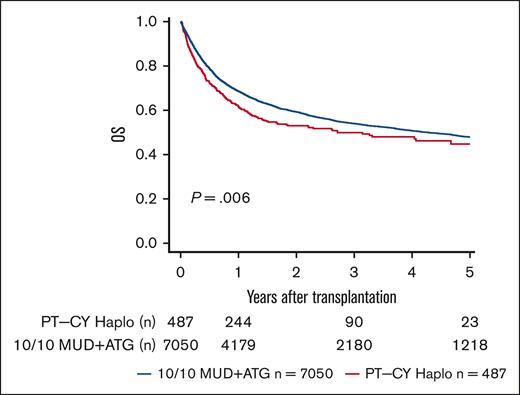

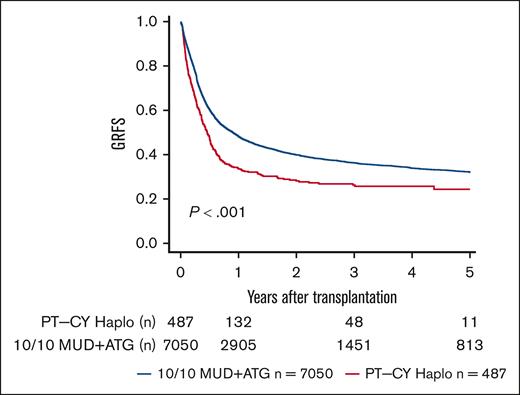

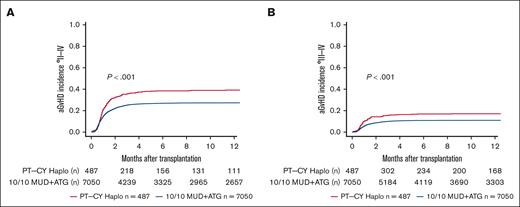

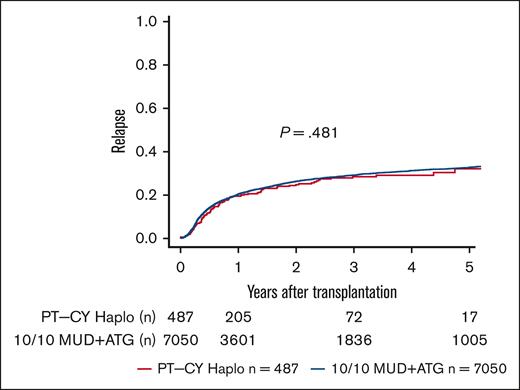

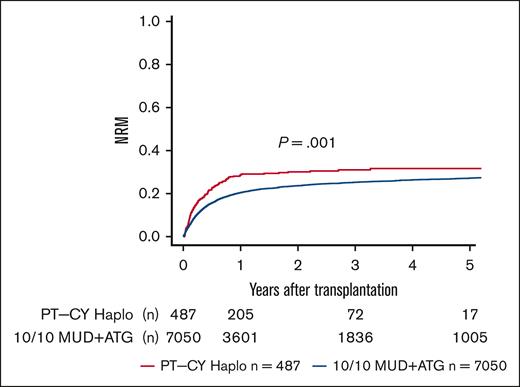

We performed sensitivity analyses for a complete-cohort approach using a 1:4 propensity score-matched analysis. We found point estimates in line with the complete-cohort analysis but narrower confidence intervals (95% CIs) and, hence, better statistical power for the full cohort approach (supplemental Table 1). In univariate analyses, lower OS and DFS were seen in PT-CY Haplo patients than 10/10 MUD patients (5-year OS, 44.8% vs 47.9% [P = .006]; 5-year DFS, 36.2% vs 40% [P = .013]; Figure 1; Table 2). GVHD-free and relapse-free survival (GRFS) was significantly worse in PT-CY Haplo patients (5-year GRFS, 24.4% vs 32% [P < .001]; Figure 2; Table 2). This difference may be attributed to a significantly higher aGVHD rate in the PT-CY Haplo group (1-year aGVHD grade 2-4 incidence, 39.2% vs 27.3% [P < .001]; 1-year aGVHD grade 3-4 incidence, 17.1% vs 11.1% [P < .001]; Figure 3A-B; Table 2) and a significantly higher NRM rate (5-year NRM, 31.7% vs 27.2% [P = .001]; Figure 4, Table 2). Additionally, relapse incidence was similar in both groups (5-year relapse, 32.1% vs 32.8% [P = .482]; Figure 5, Table 2).

Overall Survival. Unadjusted 5-year OS according to transplant type (P = .006).

Overall Survival. Unadjusted 5-year OS according to transplant type (P = .006).

Univariate probabilities (%) with 95% CI at different time points

| End point . | Group . | 1 y . | 3 y . | 5 y . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS | PT-CY Haplo | 61.9 (57.6-66.5) | 49.9 (45.1-55.3) | 44.8 (39.0-51.4) | .006 |

| 10/10 MUD | 68.6 (67.5-69.7) | 54.0 (52.7-55.3) | 47.9 (46.5-49.3) | ||

| DFS | PT-CY Haplo | 51.9 (47.5-56.7) | 40.5 (35.7-46.0) | 36.2 (30.4-43.1) | .013 |

| 10/10 MUD | 59.1 (57.9-60.3) | 45.6 (44.3-46.9) | 40.0 (38.7-41.4) | ||

| GRFS | PT-CY Haplo | 33.8 (29.6-38.4) | 26.3 (22.2-31.1) | 24.4 (19.9-29.9) | <.001 |

| 10/10 MUD | 48.2 (47.0-49.4) | 36.3 (35.1-37.6) | 32.0 (30.8-33.3) | ||

| NRM | PT-CY Haplo | 28.6 (24.5-32.8) | 31.0 (26.7-35.5) | 31.7 (27.2-36.2) | .001 |

| 10/10 MUD | 20.5 (19.5-21.4) | 25.2 (24.2-26.3) | 27.2 (26.0-28.3) | ||

| aGVHD 2-4 | PT-CY Haplo | 39.2 (34.8-43.6) | <.001 | ||

| 10/10 MUD | 27.3 (26.3-28.4) | ||||

| aGVHD 3-4 | PT-CY Haplo | 17.1 (13.9-20.6) | <.001 | ||

| 10/10 MUD | 11.1 (10.3-11.8) | ||||

| Relapse | PT-CY Haplo | 19.5 (16.0-23.3) | 28.5 (23.9-33.2) | 32.1 (26.1-38.3) | .482 |

| 10/10 MUD | 20.5 (19.5-21.4) | 29.2 (28.0-30.4) | 32.8 (31.6-34.1) | ||

| cGVHD | PT-CY Haplo | 31.9 (27.6-36.2) | 36.3 (31.8-40.9) | 38.7 (33.5-43.8) | .001 |

| 10/10 MUD | 24.5 (23.5-25.6) | 30.1 (29.0-31.3) | 30.8 (29.6-32.0) |

| End point . | Group . | 1 y . | 3 y . | 5 y . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS | PT-CY Haplo | 61.9 (57.6-66.5) | 49.9 (45.1-55.3) | 44.8 (39.0-51.4) | .006 |

| 10/10 MUD | 68.6 (67.5-69.7) | 54.0 (52.7-55.3) | 47.9 (46.5-49.3) | ||

| DFS | PT-CY Haplo | 51.9 (47.5-56.7) | 40.5 (35.7-46.0) | 36.2 (30.4-43.1) | .013 |

| 10/10 MUD | 59.1 (57.9-60.3) | 45.6 (44.3-46.9) | 40.0 (38.7-41.4) | ||

| GRFS | PT-CY Haplo | 33.8 (29.6-38.4) | 26.3 (22.2-31.1) | 24.4 (19.9-29.9) | <.001 |

| 10/10 MUD | 48.2 (47.0-49.4) | 36.3 (35.1-37.6) | 32.0 (30.8-33.3) | ||

| NRM | PT-CY Haplo | 28.6 (24.5-32.8) | 31.0 (26.7-35.5) | 31.7 (27.2-36.2) | .001 |

| 10/10 MUD | 20.5 (19.5-21.4) | 25.2 (24.2-26.3) | 27.2 (26.0-28.3) | ||

| aGVHD 2-4 | PT-CY Haplo | 39.2 (34.8-43.6) | <.001 | ||

| 10/10 MUD | 27.3 (26.3-28.4) | ||||

| aGVHD 3-4 | PT-CY Haplo | 17.1 (13.9-20.6) | <.001 | ||

| 10/10 MUD | 11.1 (10.3-11.8) | ||||

| Relapse | PT-CY Haplo | 19.5 (16.0-23.3) | 28.5 (23.9-33.2) | 32.1 (26.1-38.3) | .482 |

| 10/10 MUD | 20.5 (19.5-21.4) | 29.2 (28.0-30.4) | 32.8 (31.6-34.1) | ||

| cGVHD | PT-CY Haplo | 31.9 (27.6-36.2) | 36.3 (31.8-40.9) | 38.7 (33.5-43.8) | .001 |

| 10/10 MUD | 24.5 (23.5-25.6) | 30.1 (29.0-31.3) | 30.8 (29.6-32.0) |

GvHD and Relapse Free Survival. Unadjusted 5-year GRFS according to transplant type (P < .001).

GvHD and Relapse Free Survival. Unadjusted 5-year GRFS according to transplant type (P < .001).

aGvHD Incidences. (A) Unadjusted 1-year aGVHD °2 to 4 incidence according to transplant type (P < .001). (B) Unadjusted 1-year aGVHD °3 to 4 incidence according to transplant type (P < .001).

aGvHD Incidences. (A) Unadjusted 1-year aGVHD °2 to 4 incidence according to transplant type (P < .001). (B) Unadjusted 1-year aGVHD °3 to 4 incidence according to transplant type (P < .001).

Non-relapse Mortality. Unadjusted 5-year NRM incidence according to transplant type (P = .001).

Non-relapse Mortality. Unadjusted 5-year NRM incidence according to transplant type (P = .001).

Relapse Incidence. Unadjusted 5-year relapse incidence according to transplant type (P = .481).

Relapse Incidence. Unadjusted 5-year relapse incidence according to transplant type (P = .481).

Multivariate analyses confirmed the results of the univariate analyses. In multivariate analyses, these differences remained for OS and DFS (OS, [hazard ratio (HR), 1.27; 95% CI, 1.10- 1.47; P = .001]; DFS [HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.02-1.34; P = .022]; Table 3). Furthermore, lower GRFS was associated with PT-CY Haplo in multivariate modeling (HR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.19-1.50; P < .001). Higher NRM risk was found for PT-CY Haplo (HR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.36-1.94; P < .001). The risks of aGVHD grade 2 to 4, aGVHD grade 3 to 4, and cGVHD were higher in the PT-CY Haplo group than the 10/10 MUD group (aGVHD grade 2-4 [HR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.29-1.75; P < .001]; aGVHD grade 3-4 [HR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.37-2.20; P < .001]; cGVHD [HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.11-1.51; P = .001]; Table 4). In multivariate analysis, a slightly lower incidence of relapse was observed in the PT-CY Haplo group (relapse: HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.69-0.99; P = .038). Engraftment was delayed in the PT-CY Haplo group (median time to engraftment 10/10 MUD, 17 days; PT-CY Haplo, 20 days [P < .001]; and day-30 engraftment rates 10/10 MUD, 92.7%; PT-CY Haplo, 83.9%; supplemental Figure 1).

Multivariate analysis survival end points

| . | OS . | DFS . | GRFS . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | |

| Analysis group (Ref., 10/10 MUD), PT-CY Haplo | 1.27 | 1.10-1.47 | .001 | 1.17 | 1.02-1.34 | .022 | 1.34 | 1.19-1.50 | <.001 |

| Pat. age (Ref., 18-19), y | |||||||||

| 20-29 | 1.46 | 0.91-2.33 | .114 | 1.13 | 0.78-1.64 | .516 | 1.05 | 0.76-1.46 | .751 |

| 30-39 | 1.47 | 0.92-2.35 | .107 | 1.14 | 0.79-1.65 | .492 | 1.09 | 0.79-1.51 | .606 |

| 40-49 | 1.83 | 1.16-2.88 | .009 | 1.31 | 0.92-1.87 | .136 | 1.20 | 0.87-1.63 | .263 |

| 50-59 | 2.28 | 1.45-3.57 | <.001 | 1.58 | 1.11-2.25 | .011 | 1.40 | 1.03-1.91 | .033 |

| 60-69 | 2.73 | 1.74-4.27 | <.001 | 1.71 | 1.20-2.43 | .003 | 1.42 | 1.04-1.94 | .026 |

| 70-79 | 3.31 | 2.09-5.24 | <.001 | 2.07 | 1.44-2.97 | <.001 | 1.64 | 1.19-2.27 | .002 |

| EBMT stage (Ref., early) | |||||||||

| Intermediate | 1.35 | 1.22-1.48 | <.001 | 1.27 | 1.16-1.38 | <.001 | 1.20 | 1.11-1.30 | <.001 |

| Advanced | 1.85 | 1.70-2.01 | <.001 | 1.89 | 1.75-2.04 | <.001 | 1.72 | 1.60-1.85 | <.001 |

| KPS (Ref., ≥80), <80 | 1.84 | 1.63-2.09 | <.001 | 1.64 | 1.46-1.85 | <.001 | 1.59 | 1.42-1.78 | <.001 |

| Year of HSCT (Ref., 2010-2015), 2016-2020 | 0.88 | 0.79-0.97 | .015 | 0.89 | 0.80-0.98 | .018 | 0.91 | 0.83-1.00 | .039 |

| Donor age (Ref., 18-19), y | |||||||||

| 20-29 | 1.05 | 0.82-1.36 | .689 | 1.00 | 0.80-1.25 | .986 | 1.06 | 0.87-1.30 | .564 |

| 30-39 | 1.10 | 0.85-1.43 | .46 | 1.06 | 0.84-1.33 | .643 | 1.10 | 0.90-1.35 | .360 |

| 40-49 | 1.38 | 1.06-1.81 | .018 | 1.20 | 0.95-1.52 | .134 | 1.28 | 1.04-1.59 | .022 |

| 50-59 | 1.60 | 1.19-2.16 | .002 | 1.46 | 1.12-1.91 | .005 | 1.41 | 1.11-1.80 | .005 |

| 60-99 | 1.01 | 0.53-1.92 | .98 | 0.99 | 0.56-1.76 | .979 | 0.86 | 0.50-1.49 | .599 |

| HCT-CI score (Ref., 0), ≥1 | 1.22 | 1.12-1.33 | <.001 | 1.10 | 1.02-1.19 | .020 | 1.06 | 0.99-1.14 | .105 |

| CMV Pat. Don. (Ref., neg. neg.) | |||||||||

| Neg. pos. | 1.18 | 1.03-1.34 | .015 | 1.14 | 1.01-1.29 | .032 | 1.09 | 0.97-1.22 | .137 |

| Pos. neg. | 1.23 | 1.12-1.36 | <.001 | 1.18 | 1.08-1.29 | <.001 | 1.08 | 0.99-1.17 | .073 |

| Pos. pos. | 1.12 | 1.03-1.21 | .008 | 1.09 | 1.01-1.18 | .024 | 1.06 | 0.99-1.14 | .101 |

| Conditioning (Ref., MAC), RIC | 0.92 | 0.86-0.99 | .028 | 0.91 | 0.86-0.98 | .009 | 0.93 | 0.88-0.99 | .031 |

| . | OS . | DFS . | GRFS . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | |

| Analysis group (Ref., 10/10 MUD), PT-CY Haplo | 1.27 | 1.10-1.47 | .001 | 1.17 | 1.02-1.34 | .022 | 1.34 | 1.19-1.50 | <.001 |

| Pat. age (Ref., 18-19), y | |||||||||

| 20-29 | 1.46 | 0.91-2.33 | .114 | 1.13 | 0.78-1.64 | .516 | 1.05 | 0.76-1.46 | .751 |

| 30-39 | 1.47 | 0.92-2.35 | .107 | 1.14 | 0.79-1.65 | .492 | 1.09 | 0.79-1.51 | .606 |

| 40-49 | 1.83 | 1.16-2.88 | .009 | 1.31 | 0.92-1.87 | .136 | 1.20 | 0.87-1.63 | .263 |

| 50-59 | 2.28 | 1.45-3.57 | <.001 | 1.58 | 1.11-2.25 | .011 | 1.40 | 1.03-1.91 | .033 |

| 60-69 | 2.73 | 1.74-4.27 | <.001 | 1.71 | 1.20-2.43 | .003 | 1.42 | 1.04-1.94 | .026 |

| 70-79 | 3.31 | 2.09-5.24 | <.001 | 2.07 | 1.44-2.97 | <.001 | 1.64 | 1.19-2.27 | .002 |

| EBMT stage (Ref., early) | |||||||||

| Intermediate | 1.35 | 1.22-1.48 | <.001 | 1.27 | 1.16-1.38 | <.001 | 1.20 | 1.11-1.30 | <.001 |

| Advanced | 1.85 | 1.70-2.01 | <.001 | 1.89 | 1.75-2.04 | <.001 | 1.72 | 1.60-1.85 | <.001 |

| KPS (Ref., ≥80), <80 | 1.84 | 1.63-2.09 | <.001 | 1.64 | 1.46-1.85 | <.001 | 1.59 | 1.42-1.78 | <.001 |

| Year of HSCT (Ref., 2010-2015), 2016-2020 | 0.88 | 0.79-0.97 | .015 | 0.89 | 0.80-0.98 | .018 | 0.91 | 0.83-1.00 | .039 |

| Donor age (Ref., 18-19), y | |||||||||

| 20-29 | 1.05 | 0.82-1.36 | .689 | 1.00 | 0.80-1.25 | .986 | 1.06 | 0.87-1.30 | .564 |

| 30-39 | 1.10 | 0.85-1.43 | .46 | 1.06 | 0.84-1.33 | .643 | 1.10 | 0.90-1.35 | .360 |

| 40-49 | 1.38 | 1.06-1.81 | .018 | 1.20 | 0.95-1.52 | .134 | 1.28 | 1.04-1.59 | .022 |

| 50-59 | 1.60 | 1.19-2.16 | .002 | 1.46 | 1.12-1.91 | .005 | 1.41 | 1.11-1.80 | .005 |

| 60-99 | 1.01 | 0.53-1.92 | .98 | 0.99 | 0.56-1.76 | .979 | 0.86 | 0.50-1.49 | .599 |

| HCT-CI score (Ref., 0), ≥1 | 1.22 | 1.12-1.33 | <.001 | 1.10 | 1.02-1.19 | .020 | 1.06 | 0.99-1.14 | .105 |

| CMV Pat. Don. (Ref., neg. neg.) | |||||||||

| Neg. pos. | 1.18 | 1.03-1.34 | .015 | 1.14 | 1.01-1.29 | .032 | 1.09 | 0.97-1.22 | .137 |

| Pos. neg. | 1.23 | 1.12-1.36 | <.001 | 1.18 | 1.08-1.29 | <.001 | 1.08 | 0.99-1.17 | .073 |

| Pos. pos. | 1.12 | 1.03-1.21 | .008 | 1.09 | 1.01-1.18 | .024 | 1.06 | 0.99-1.14 | .101 |

| Conditioning (Ref., MAC), RIC | 0.92 | 0.86-0.99 | .028 | 0.91 | 0.86-0.98 | .009 | 0.93 | 0.88-0.99 | .031 |

Abbreviations are explained in Table 1.

Multivariate analysis competing risks end points

| . | NRM . | Relapse . | aGVHD 2-4 . | aGVHD 3-4 . | cGVHD . | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | |

| Analysis group (Ref., 10/10 MUD), PT-CY Haplo | 1.62 | 1.36-1.94 | <.001 | 0.83 | 0.69-0.99 | .038 | 1.46 | 1.25-1.71 | <.001 | 1.74 | 1.37-2.20 | <.001 | 1.30 | 1.11-1.51 | .001 |

| Patient age (Ref., 18-19), y | |||||||||||||||

| 20-29 | 1.16 | 0.59-2.27 | .673 | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| 30-39 | 1.23 | 0.63-2.42 | .544 | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| 40-49 | 2.09 | 1.10-3.98 | .024 | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| 50-59 | 2.43 | 1.28-4.59 | .006 | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| 60-69 | 3.19 | 1.69-6.02 | <.001 | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| 70-79 | 4.21 | 2.21-8.03 | <.001 | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| EBMT stage (Ref., early) | |||||||||||||||

| Intermediate | 1.27 | 1.12-1.43 | <.001 | 1.13 | 1.00-1.27 | .050 | — | — | 0.90 | 0.81-1.00 | .051 | ||||

| Advanced | 1.41 | 1.27-1.57 | <.001 | 1.78 | 1.61-1.97 | <.001 | — | — | 0.75 | 0.67-0.82 | <.001 | ||||

| KPS (Ref., ≥80), <80 | 2.10 | 1.81-2.43 | <.001 | — | — | — | 0.85 | 0.71-1.01 | .065 | ||||||

| Year of HSCT (Ref., 2010-2015), 2016-2020 | 0.87 | 0.76-1.00 | .058 | 0.92 | 0.83-1.01 | .085 | 0.96 | 0.86-1.07 | .476 | 1.02 | 0.85-1.21 | .849 | 0.83 | 0.76-0.92 | <.001 |

| Donor age (Ref., 18-19), y | |||||||||||||||

| 20-29 | 1.48 | 1.01-2.16 | .044 | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| 30-39 | 1.58 | 1.08-2.31 | .019 | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| 40-49 | 2.00 | 1.35-2.95 | .001 | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| 50-59 | 2.15 | 1.41-3.28 | <.001 | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| 60-99 | 1.50 | 0.63-3.58 | .361 | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| HCT-CI score (Ref., 0), ≥1 | 1.43 | 1.27-1.61 | <.001 | 0.85 | 0.77-0.93 | .001 | 1.15 | 1.03-1.27 | .010 | 1.27 | 1.07-1.50 | .005 | 0.87 | 0.80-0.96 | .004 |

| CMV Pat. Don. (Ref., neg. neg.) | |||||||||||||||

| Neg. pos. | 1.03 | 0.86-1.22 | .775 | — | 1.01 | 0.86-1.19 | .865 | 0.86 | 0.66-1.13 | .285 | — | ||||

| Pos. neg. | 1.23 | 1.08-1.39 | .001 | — | 0.91 | 0.80-1.03 | .120 | 0.91 | 0.75-1.11 | .349 | — | ||||

| Pos. pos. | 1.06 | 0.95-1.17 | .326 | — | 0.94 | 0.85-1.04 | .259 | 1.00 | 0.86-1.17 | .954 | — | ||||

| Conditioning intensity (Ref., MAC), RIC | — | — | — | — | 1.14 | 1.05-1.24 | .003 | ||||||||

| Previous autologous Tx (Ref., no), yes | — | — | — | — | — | ||||||||||

| Stem cell source (Ref., PBSC), BM | — | — | — | 0.74 | 0.53-1.03 | .076 | 0.75 | 0.61-0.92 | .006 | ||||||

| Sex mismatch (Ref., no), yes | — | — | — | — | 1.10 | 0.96-1.25 | .165 | ||||||||

| . | NRM . | Relapse . | aGVHD 2-4 . | aGVHD 3-4 . | cGVHD . | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | |

| Analysis group (Ref., 10/10 MUD), PT-CY Haplo | 1.62 | 1.36-1.94 | <.001 | 0.83 | 0.69-0.99 | .038 | 1.46 | 1.25-1.71 | <.001 | 1.74 | 1.37-2.20 | <.001 | 1.30 | 1.11-1.51 | .001 |

| Patient age (Ref., 18-19), y | |||||||||||||||

| 20-29 | 1.16 | 0.59-2.27 | .673 | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| 30-39 | 1.23 | 0.63-2.42 | .544 | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| 40-49 | 2.09 | 1.10-3.98 | .024 | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| 50-59 | 2.43 | 1.28-4.59 | .006 | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| 60-69 | 3.19 | 1.69-6.02 | <.001 | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| 70-79 | 4.21 | 2.21-8.03 | <.001 | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| EBMT stage (Ref., early) | |||||||||||||||

| Intermediate | 1.27 | 1.12-1.43 | <.001 | 1.13 | 1.00-1.27 | .050 | — | — | 0.90 | 0.81-1.00 | .051 | ||||

| Advanced | 1.41 | 1.27-1.57 | <.001 | 1.78 | 1.61-1.97 | <.001 | — | — | 0.75 | 0.67-0.82 | <.001 | ||||

| KPS (Ref., ≥80), <80 | 2.10 | 1.81-2.43 | <.001 | — | — | — | 0.85 | 0.71-1.01 | .065 | ||||||

| Year of HSCT (Ref., 2010-2015), 2016-2020 | 0.87 | 0.76-1.00 | .058 | 0.92 | 0.83-1.01 | .085 | 0.96 | 0.86-1.07 | .476 | 1.02 | 0.85-1.21 | .849 | 0.83 | 0.76-0.92 | <.001 |

| Donor age (Ref., 18-19), y | |||||||||||||||

| 20-29 | 1.48 | 1.01-2.16 | .044 | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| 30-39 | 1.58 | 1.08-2.31 | .019 | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| 40-49 | 2.00 | 1.35-2.95 | .001 | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| 50-59 | 2.15 | 1.41-3.28 | <.001 | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| 60-99 | 1.50 | 0.63-3.58 | .361 | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| HCT-CI score (Ref., 0), ≥1 | 1.43 | 1.27-1.61 | <.001 | 0.85 | 0.77-0.93 | .001 | 1.15 | 1.03-1.27 | .010 | 1.27 | 1.07-1.50 | .005 | 0.87 | 0.80-0.96 | .004 |

| CMV Pat. Don. (Ref., neg. neg.) | |||||||||||||||

| Neg. pos. | 1.03 | 0.86-1.22 | .775 | — | 1.01 | 0.86-1.19 | .865 | 0.86 | 0.66-1.13 | .285 | — | ||||

| Pos. neg. | 1.23 | 1.08-1.39 | .001 | — | 0.91 | 0.80-1.03 | .120 | 0.91 | 0.75-1.11 | .349 | — | ||||

| Pos. pos. | 1.06 | 0.95-1.17 | .326 | — | 0.94 | 0.85-1.04 | .259 | 1.00 | 0.86-1.17 | .954 | — | ||||

| Conditioning intensity (Ref., MAC), RIC | — | — | — | — | 1.14 | 1.05-1.24 | .003 | ||||||||

| Previous autologous Tx (Ref., no), yes | — | — | — | — | — | ||||||||||

| Stem cell source (Ref., PBSC), BM | — | — | — | 0.74 | 0.53-1.03 | .076 | 0.75 | 0.61-0.92 | .006 | ||||||

| Sex mismatch (Ref., no), yes | — | — | — | — | 1.10 | 0.96-1.25 | .165 | ||||||||

Relevant covariates that were associated with a higher risk in multivariate analysis were increasing patient age, intermediate and advanced disease stage, KPS <80, older donor age, and HCT-CI ≥1. Covariates that were associated with better outcomes were reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) and recent years of transplantation. BM as a stem cell source was associated with a tendency toward less GVHD.

Discussion

Using registry data from the DRST, we compared Haplo-Tx + PT-CY and 10/10 MUDs + ATG. Both univariate and multivariate analyses showed a slightly lower 5-year OS and DFS and a more pronounced lower GRFS for Haplo-Tx with PT-CY. This observation may, in part, be explained by a higher risk for GVHD in the latter group. In addition to that, specific toxicities of high-dose cyclophosphamide, such as possible early cardiac events and increased risk of non-cytomegalovirus herpesvirus infections, recently shown in different studies, may have led to an increased risk of NRM.19,20 However, the causes of mortality were not analyzed in this study. It is noteworthy that we found significantly higher rates of aGVHD in the PT-CY Haplo-Tx group. One explanation for this observation may be the fact that most patients in Germany receive ATG as part of the prophylaxis regimen before unrelated transplantation, and in our study, only 10/10 MUD transplants with ATG-based prophylaxis were included. The suppressive effect of ATG on aGVHD may lead to the advantage we see in this analysis for the MUD cohort. Another reason for this observation may be the high proportion of PBSC transplants in the PT-CY Haplo-Tx group possibly featuring a higher aGVHD risk due to its higher T-cell count than the original Baltimore protocol.21 We hypothesize that the combination of a high proportion of PBSC grafts, higher proportion of MAC, as well as the age structure with a substantial amount of older patients (age >50 years, 66%) among Haplo–PT-CY patients may lead to both an increased aGVHD risk and less well-tolerated treatment toxicity, consequentially leading to a higher NRM in our cohort. Conversely, the administration of ATG and matching for HLA-DQB1 in MUD patients, which prevents additional linked HLA mismatches within extended HLA class II haplotypes, may lead to a lower GVHD risk in our 10/10 MUD cohort.

With the increasing numbers of Haplo-Tx performed worldwide, comparative studies in various hematologic diseases, particularly in acute myeloid leukemia, has also increased. In one study, Brissot et al compared Haplo-Tx with PT-CY (n = 199) and 10/10 MUD (n = 1111). OS, GRFS, aGVHD, and 2-year NRM were similar between the groups in patients with acute myeloid leukemia with active disease.10 Another study from Baker et al compared matched or mismatched unrelated donor (n = 59) with conventional GVHD prophylaxis and Haplo-Tx with PT-CY (n = 54) in various types of malignancies. Relapse risk, transplantation-related mortality (TRM), PFS, OS, cumulative incidence of 6-month grade 2 to 4 aGVHD, grade 3 to 4 aGVHD, and 2-year cGVHD did not differ between the 2 groups.9

In this study, we report a cumulative incidence of 1-year grade 2 to 4 aGVHD of 39.2% in the Haplo-Tx group, corresponding to 27.3% in the 10/10 MUD group. The stem cell source was more often BM in the PT-CY Haplo group than in the reference group. In a recent study, published by Rashidi et al, 6-month aGVHD rate for Haplo-Tx with PT-CY was 32%.22 In one of the largest Haplo cohorts with PT-CY published so far, the CIBMTR reported that 100-day grade 2 to 4 GVHD rates were 29% in patients who received RIC and 33% for those who received MAC regimen. In the CIBMTR cohort, Haplo-Tx and MUD-Tx, both with PT-CY–based GVHD prophylaxis, were compared. Severe aGVHD rates and NRM were found to be higher in the Haplo group, whereas OS and DFS were lower after RIC regimen, and severe aGVHD was also higher in the group receiving MAC regimen.13 Due to the significant differences between the groups, the reanalysis of this data set with propensity score matching and inclusion of donor age was published in 2022. After matching 8/8 MUD and Haplo in a 1:5 ratio, there were no significant differences found in OS, DFS, and NRM.23 HLA disparity results in a higher incidence of cGVHD, whose complications are difficult to manage and influence the life quality of the patients.24 For the end point occurrence of cGVHD, the 5-year cGVHD rate was 38.7% in the Haplo group and 30.8% in the MUD group, which was statistically significant. There are studies in the literature with different results regarding the rates of cGVHD. In a meta-analysis published in 2020, a total of 17 studies were evaluated, which compared Haplo-Tx with PT-CY and MUD-Tx without PT-CY. In contrast to our findings, a reduced incidence of cGVHD was found in the Haplo groups.25 In another recently published study, GVHD characteristics after Haplo-Tx with PT-CY were compared with MUD using conventional prophylaxis. In this study, chronic gastrointestinal GVHD was less common after Haplo-Tx with PT-CY.14 In a study by the Japan Marrow Donor Program (JMDP) comparing Haplo–PT-CY with MUD transplantation for myelodisplastic syndrome (MDS), similar survival outcomes and less aGVHD for Haplo–PT-CY patients were found, but HLA-matching standard was 8/8, and relatively few patients in the 8/8 MUD group received ATG.26 In a single-center study by Mehta et al comparing Haplo–PT-CY vs MUD–PT-CY vs MSD–PT-CY, better survival was seen in MUD and MSD groups due to less NRM. In this study, aGVHD incidences were lowest in the PT-CY Haplo group, in which predominantly BM was given; 76% of the patients had received a RIC regimen, and the median patient age was 51 years.27

The introduction of Haplo-Tx with PT-CY–based GVHD prophylaxis for the treatment of malignant hematologic diseases raised different questions. In this context, probably one of the most important questions was whether there would be an increase in relapse, potentially resulting in adverse survival. This was based on the perception that high-dose PT-CY eliminates proliferating alloreactive T and natural killer cells immediately after transplantation and selectively keeps bystander naive and memory T cells.28-30 The slightly higher relapse incidence in multivariate analysis in the 10/10 MUD cohort are consistent with the concomitant lower GVHD incidences. Our study design precludes inference on the contribution of PT-CY itself to transplantation-associated toxicity.19 The preparation and dose of ATG/ anti–T lymphocyte globulin (ATLG) might influence GVHD risk and may account for the differential findings when comparing independent studies. In Germany, the vast majority of centers are using ATLG, whereas, in most of the other studies, ATG was used.31,32 Unfortunately, there was no sufficient distinction between ATG and ATLG given in the primary data, so the potential influence of ATG/ATLG preparation could not be analyzed in our study. Caution should be applied when comparing GRFS between different studies because the definitions for GRFS may vary. In our analysis, we considered only severe acute and chronic GVHD as events.

Parallel to the general trend worldwide, Haplo-Tx with PT-CY is also increasing in Germany. Within our study, 86% of the PT-CY Haplo transplantations were performed in the last 5 years, whereas only 45.5% of 10/10 MUD transplantations were conducted during these years. Due to the retrospective nature of our study, the potential impact of underlying disease risk on the decision to offer Haplo-Tx or 10/10 MUD transplantation was not evaluated. Because we chose to analyze the complete cohort, baseline characteristics are not balanced between the 2 groups and must be controlled for in the analysis. Our observation is in line with the report of Brazauskas and Logan, who stated that a complete-cohort approach is often more powerful.33 Another advantage of the complete-cohort approach is that it is immediately amenable to competing risks. In the sensitivity analyses of composite end points, we also compared the results with a propensity score-matched analysis, accounting for matching using stratified analyses, frailty modeling, and the marginal approach of Lee et al.34

To interpret the results of this retrospective observational study, some important limitations other than those mentioned above should also be taken into account. The experience or preference of transplant centers in the donor selection process may introduce hidden confounders. Moreover, relatively homogenous population genetics in Germany as well as the high number of volunteer donors registered in Germany may influence the results of our study in comparison with international studies. Additionally, because our study uses registry data, some of the patients may have been included in previous EBMT studies. However, our study is, to our knowledge, the first German multicenter report with a large number of cases comparing Haplo-Tx with PT-CY as a GVHD prophylaxis with 10/10 MUD transplantations with ATG-based GVHD regimens.

In conclusion, our study indicates that transplantation with a well-matched unrelated donor in combination with ATG treatment leads to lower aGVHD and cGVHD rates and improved survival outcomes compared with Haplo-Tx with PT-CY. A prospective randomized study is warranted to define the position of Haplo-Tx with PT-CY within the allogeneic donor selection algorithm.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant FU 1124).

The funding sources did not influence the content of the manuscript or the decision to submit for publication.

Authorship

Contribution: D.F., N.K., J.M., A.A., S.L., and H.S. are principal investigators, who designed the study, performed data analysis/interpretation, and wrote the manuscript; and E.S., M.R., J.S., T.S., G.B., G-N.F., M.S., P.D., R.Z., D.T., W.B., M. Eder, M. Edinger, E.M.A., C.N., A.S.-M., S.S., and J.B. contributed in data interpretation and in editing of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: R.Z. received honoraria from Novartis, Incyte, Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, medac, and Neovii. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

A complete list of the members of the German Registry of Stem Cell Transplantation study group appears in “Appendix.”

Correspondence: Daniel Fürst, Department of Transplantation Immunology, Institute of Clinical Transfusion Medicine and Immunogenetics Ulm, Helmholtzstrasse 10, 89081 Ulm, Germany; email: d.fuerst@blutspende.de.

Appendix

The complete list of the German Registry of Stem Cell Transplantation members contributing to this study are as follows: Nicolaus Kröger, UKE - Stammzelltransplantation Hamburg, 833 patients; Thomas Schroeder, Uni - Hämatologie u. Stammzelltr. Essen, 732 patients; Matthias Stelljes, Universitätsklinikum Münster, 450 patients; Peter Dreger, Universitätsklinikum Heidelberg, 422 patients; Matthias Eder, Med. Hochschule Hannover, 354 patients; Robert Zeiser, Universitätsklinikum Freiburg, 339 patients; Wolfgang Bethge, Universitätsklinikum Tübingen, 332 patients; Daniel Teschner, Universitätsklinikum Würzburg, 328 patients; Matthias Edinger, Universitätsklinikum Regensburg, 289 patients; Uwe Platzbecker, Universitätsklinikum Leipzig, 247 patients; Ahmet Elmaagacli, Asklepios Klinik St Georg Hamburg, 228 patients; Inken Hilgendorf, Universitätsklinikum Jena, 227 patients; Andreas Burchert, Universitätsklinikum Marburg, 225 patients; Friedrich Stölzel, Universitätsklinikum Kiel, 207 patients; Mareike Verbeek, Klinikum rechts der Isar München, 206 patients; Elisa Sala, Universitätsklinikum Ulm, 204 patients; Johanna Tischer, Klinikum Großhadern München, 182 patients; Johannes Schetelig, Universitätsklinikum Dresden, 174 patients; Arne Brecht, DKD Helios Klinik Wiesbaden, 145 patients; Martin Kaufmann, Robert-Bosch-Krankenhaus Stuttgart, 113 patients; Christoph Kimmich, Klinikum Oldenburg, 110 patients; med. Jörg Thomas Bittenbring, Universitätsklinikum Homburg (Saar), 109 patients; Gerald Wulf, Universitätsklinikum Göttingen, 91 patients; Igor Wolfgang Blau, Charité Berlin, 88 patients; Julia Winkler, Universitätsklinikum Erlangen, 84 patients; Gesine Bug, Universitätsklinikum Frankfurt (Main), 80 patients; Edgar Jost, Universitätsklinikum Aachen, 77 patients; Tobias Holderried, Universitätsklinikum Bonn, 69 patients; Mareike Dürholt, Ev. Krankenhaus Essen-Werden Essen, 67 patients; Christof Scheid, Universitätsklinikum Köln, 67 patients; Eva Wagner-Drouet, Universitätsklinikum Mainz, 61 patients; Denise Wolleschak, Universitätsklinikum Magdeburg, 49 patients; Mark Ringhoffer, Städt. Klinikum Karlsruhe, 45 patients; Michael Kiehl, Klinikum Frankfurt (Oder), 37 patients; Friederike Wortmann, Universitätsklinikum Lübeck, 34 patients; Guido Kobbe, Universitätsklinikum Düsseldorf, 33 patients; Roland Schroers, Ruhr Universität Bochum, 31 patients; Angela Krackhardt, Malteser Krankenhaus Flensburg, 29 patients; Stefan Klein, Universitätsklinikum Mannheim, 28 patients; Lutz P. Müller, Universitätsklinikum Halle (Saale), 26 patients; Christoph Schmid, Universitätsklinikum Augsburg, 22 patients; Stephan Kaun, Klinikum Bremen-Mitte Bremen, 18 patients; Ute Wieschermann, Helios Klinikum Duisburg, 10 patients; Tobias Bartscht, Helios Klinikum Schwerin, 10 patients; Ralf Georg Meyer, Gem. Transpl. Dortmund-Mitte Dortmund, 6 patients; Matthias Wölfl, Universitätsklinikum Würzburg, 3 patients; Peter Bader, Universitätsklinikum Frankfurt (Main), 3 patients; Peter Lang, Universitätsklinikum Tübingen, 3 patients; Judith Niederland, Helios Klinikum Berlin-Buch Berlin, 2 patients; Jakob Maucher, Diakonie-Klinikum Stuttgart, 2 patients; Christine Mauz-Körholz, Universitätsklinikum Gießen, 2 patients; Birgit Burkhardt, Universitätsklinikum Münster, 1 patient; Karim Kentouche, Universitätsklinikum Jena, 1 patient; Jakob Passweg, Universitätsspital Basel, 1 patient; Karoline Ehlert, Universitätsklinikum Greifswald, 1 patient.

References

Author notes

N.K. and D.F. contributed equally to this study.

Data may be accessed via the corresponding author by academic research groups beginning 12 months and ending 48 months following article publication. Access is conditional on approval by the data access committee of the DRST.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.