Key Points

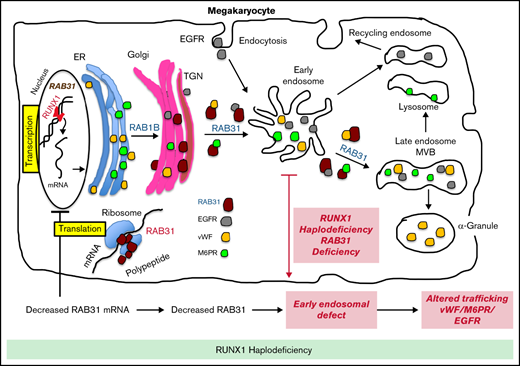

RAB31 is a RUNX1 target; regulates VWF, epidermal growth factor receptor, and mannose-6-phosphate trafficking; and is downregulated in RHD.

EE and vesicle trafficking defects induced by RAB31 downregulation likely contribute to α-granule defects with RUNX1 mutation.

Abstract

Transcription factor RUNX1 is a master regulator of hematopoiesis and megakaryopoiesis. RUNX1 haplodeficiency (RHD) is associated with thrombocytopenia and platelet granule deficiencies and dysfunction. Platelet profiling of our study patient with RHD showed decreased expression of RAB31, a small GTPase whose cell biology in megakaryocytes (MKs)/platelets is unknown. Platelet RAB31 messenger RNA was decreased in the index patient and in 2 additional patients with RHD. Promoter-reporter studies using phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate–treated megakaryocytic human erythroleukemia cells revealed that RUNX1 regulates RAB31 via binding to its promoter. We investigated RUNX1 and RAB31 roles in endosomal dynamics using immunofluorescence staining for markers of early endosomes (EEs; early endosomal autoantigen 1) and late endosomes (CD63)/multivesicular bodies. Downregulation of RUNX1 or RAB31 (by small interfering RNA or CRISPR/Cas9) showed a striking enlargement of EEs, partially reversed by RAB31 reconstitution. This EE defect was observed in MKs differentiated from a patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cell line (RHD-iMKs). Studies using immunofluorescence staining showed that trafficking of 3 proteins with distinct roles (von Willebrand factor [VWF], a protein trafficked to α-granules; epidermal growth factor receptor; and mannose-6-phosphate) was impaired at the level of EE on downregulation of RAB31 or RUNX1. There was loss of plasma membrane VWF in RUNX1- and RAB31-deficient megakaryocytic human erythroleukemia cells and RHD-iMKs. These studies provide evidence that RAB31 is downregulated in RHD and regulates megakaryocytic vesicle trafficking of 3 major proteins with diverse biological roles. EE defect and impaired vesicle trafficking is a potential mechanism for the α-granule defects observed in RUNX1 deficiency.

Introduction

Rab proteins are small GTPases that control intracellular vesicle trafficking.1-3 They function as molecular switches that alternate between guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-bound active form and guanosine diphosphate–bound inactive form to coordinate vesicle trafficking through interaction with effector molecules that bind the GTP-bound form. Intracellular trafficking events regulated by Rab proteins include budding, fission of transporting vesicles from donor membranes, their movement along cytoskeletal tracks, and docking/fusion to acceptor membranes. More than 70 members of the Rab family have been identified, and they play specific roles in vesicle trafficking, depending on their cellular locations.1,2,4 At least 40 Rab proteins are recognized in human platelets,4 but specific roles in vesicle trafficking are unknown in platelets or megakaryocytes for the majority.

RAB31 (Ras-related protein in brain 31), a member of the RAB5 subfamily of Rab GTPases, was cloned from human platelets,5 and it shared ∼82% homology with RAB22B protein identified in human melanocytes.6 RAB31 regulates anterograde and retrograde membrane trafficking between the Golgi/trans-Golgi network (TGN) and the endosomes and plasma membrane.3,7,8 It is localized in tubular vesicular carriers that bud from TGN, travels along microtubules, and fuses with endocytic membranes, indicating its critical involvement in TGN to endosome transport.7,8 Previous studies have shown that RAB31 regulates epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) trafficking from early endosomes (EEs) to late endosomes in A431 neuronal cells9 and mannose-6-phosphate receptor (M6PR) trafficking from TGN to endosomes in HeLa cells.10 RAB31 has been implicated in the maintenance of Golgi structure with a disruption on RAB31 depletion, insulin-driven glucose transporter-4 trafficking in adipocytes,11 and phagocytosis in macrophages.12 RAB31 has also been implicated in human cancers, with increased expression in some such as colorectal cancers.13,14 However, little is known about the role and function of RAB31 or the mechanisms regulating its expression in megakaryocytes and platelets.

The RUNT-related transcription factor 1, RUNX1 (also called AML1 or CBFA2), is a master regulator of hematopoiesis and a major player in megakaryocyte/platelet biology.15-19 Human monoallelic RUNX1 mutations are associated with familial thrombocytopenia, platelet α-granule and dense granule deficiencies, impaired platelet responses to activation, abnormalities in megakaryocyte differentiation, and a predisposition to myeloid malignancies.15,17,20 Our platelet expression profiling studies using Affymetrix microarrays in a patient with a heterozygous RUNX1 mutation showed that several genes were downregulated,21 and our subsequent studies found that some of them are transcriptional targets of RUNX1.18,22,23 These profiling studies also showed21 that platelet RAB31 expression was decreased in our study patient with RUNX1 haplodeficiency (RHD). In the current studies, we show that RAB31 is a direct RUNX1 transcriptional target and is downregulated in RHD. To understand the role of RAB31 in megakaryocyte/platelet biology, we studied the trafficking of 3 proteins with distinct biological roles: von Willebrand factor (VWF), an α-granule protein synthesized by human megakaryocytes; EGFR; and M6PR. We provide the first evidence that RAB31 regulates endosomal trafficking of these proteins in megakaryocytic human erythroleukemia (HEL) cells and that this trafficking is impaired and associated with an EE defect on RUNX1 downregulation. This EE defect was observed in megakaryocytes differentiated from a RHD patient–derived induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) line. These studies advance impaired RAB31-related vesicle trafficking as a potential mechanism for the α-granule defects in patients with RHD.

Methods

Patient information

Patient P1 (a 40-year-old man) has life-long thrombocytopenia and abnormal platelet function associated with a single point mutation (c.352-1G>T) in intron 3 at the splice acceptor site for exon 4 leading to a frame shift with premature termination in the conserved RUNT homology domain of RUNX1.24 Details of the platelet function abnormalities18,21,25 -27 and expression profiling studies in this patient have been described previously. We studied 2 other patients (an 8-year-old boy [P2] and his 3-year-old sister [P3]) from an unrelated family with thrombocytopenia and an RUNX1 mutation (c.508 + 1G>A). The maternal grandmother and great uncle had a history of acute myeloid leukemia. The patients had abnormal agonist-induced aggregation and secretion on laboratory testing. The studies on the patients and control subjects were approved by Institutional Review Boards and were performed after obtaining informed consent.

Cell culture

HEL cells from ATCC (Rockville, MD) were grown and induced in RPMI 1640 medium as described previously.27 These cells were treated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (10 nM) to induce megakaryocytic transformation unless specified otherwise. iPSC-derived megakaryocytes (iMKs) were differentiated as described from an established control iPSC line, designated as CHOPWT6 (Control 2 iPSC line in the study by Sullivan et al28 ) and a patient-derived iPSC line29 derived from an RHD patient with a monoallelic splice acceptor defect near exon 4 of RUNX1.17

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted from platelets derived from whole blood of healthy donors and the patients.23 The RNAs were subjected to first strand complementary DNA synthesis using Superscript III (Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Norristown, PA) and amplified by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using SYBR Green PCR (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) mix and primers (0.1 μM each) for RAB31: forward 5′-GGAGCTCAAAGTGTGCCTTC-3′ and reverse 5′-CGGCTGATTCCTTGAAAGAG-3′ or for GAPDH: forward 5′-AACTGTGTGGTC TTGAA CCTCCGT-3′ and reverse 5′-ACACACTCTCATGCAGCTACCAT-3′. The real-time PCR parameters were as follows: 95°C for 10 minutes followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds, 55°C for 20 seconds, and 72°C for 20 seconds using a Master Cycler Real-Time PCR system (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY); relative abundances were calculated by the ΔΔCT method using GAPDH as the reference gene.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed on HEL cells (1 × 106) treated with PMA (10 nM) for 24 hours using the ChIP-It kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) and antibodies as described previously.30 Chromatin samples were immunoprecipitated with anti-RUNX1 antibody (sc-8563x) or with normal immunoglobulin G (IgG) (sc-2028) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX). Immunoprecipitated samples were analyzed by PCR using the primers (supplemental Table 1). Amplification was performed by using Go Taq Green Master Mix (Promega, Madison, WI) with one cycle at 95°C for 2 minutes followed by 32 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, 62°C for 45 seconds, and 72°C for 60 seconds. Amplified products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were performed by using HEL cell nuclear extracts as described31 with infrared-labeled RAB31 probes (supplemental Table 2). RAB31 promoter region −2013/−1 (from ATG) has 4 RUNX1 consensus sites. Double-stranded oligonucleotides encompassing these sites (RAB31 site I probe −816/−797, site II probe −976/−957, site III probe −1506/−1487, and site IV probe −2016/−1997) were labeled with infrared dye 700 (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE). Binding reaction between nuclear extract (6 μg) and probe was performed on ice for 30 minutes. Supershift assays were performed with anti-RUNX1 antibody (sc-8563) or normal IgG (sc-2028) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The reaction mixture was resolved by electrophoresis using 5% TBE ready-made gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and visualized on an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences).

Promoter-reporter assays

The RAB31 wild-type (WT) promoter (-2023 bp/+41 bp) and constructs with specific mutations in RUNX1 sites were generated by using a directional PCR method with gene-specific primers incorporated with restriction sites (MluI or Nhe I at 5′ side and Hind III or Nhe I at 3′ side). The PCR products were cloned into TOPO TA cloning vector (Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific). The recombinant TOPO TA plasmid was digested with appropriate restriction enzymes, and the promoter region was subcloned in between same restriction sites of the pGL3-Basic promoter. Sequences were confirmed by DNA sequencing on the ABI Prism 377 (Genewiz, South Plainfield, NJ). Promoter-reporter constructs were transfected individually along with a standard Renilla luciferase (in a 50:1 ratio) into HEL cells (2 × 106) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Philadelphia, PA). In parallel, promoter-less pGL3-Basic vector was also transfected in these experiments, and dual luciferase assays were performed as described previously.31 The primer sequences of WT construct and its mutants are shown in supplemental Table 3. Promoter activity was expressed as the ratio of firefly luciferase activity to Renilla luciferase activity relative to that of the promoter-less vector. All transfection experiments were performed 3 times in triplicate.

RAB31 regulation by RUNX1

HEL cells (2 × 106) were cotransfected with WT RAB31 luciferase promoter construct along with control small interfering RNA (siRNA) or RUNX1 siRNA (100 nM each; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) to determine downregulation of promoter activity. Cells were cotransfected with RAB31 WT luciferase construct and RUNX1 expression vector, RUNX1-pCMV6-XL4, or its empty vector, pCMV-XL4 (1 µg each; OriGene Technologies, Rockville, MD) to study the effect of RUNX1 overexpression. pRL Renilla Luciferase Control Reporter Vector (pRL-TK, 0.1 μg) was used in each transfection as an internal standard. Dual-luciferase assays were performed. Protein levels were assessed in cell lysates by immunoblotting.30

Immunoblotting

HEL cells were lysed in M-Per protein extraction reagent (Pierce Biotechnology, Waltham, MA) with protease inhibitor cocktail (Active Motif) and subjected to gel electrophoresis on 4% to 20% Mini-PROTEAN TGX gels (Bio-Rad) and the protein transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Blots were probed with antibodies against RAB31 (ARP61983_P050; Aviva Systems Biology, San Diego, CA), RUNX1 (sc-8563 or sc-365644), or actin (sc-1616R) or M6PR (sc-365196) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, and mPR alpha polyclonal antibody (PA5-61376, Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific), and then with IRDye-labeled secondary antibodies (LI-COR Biosciences) using Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences).

Nucleofection

HEL cells (1 × 106) were mixed with control siRNA or RUNX1 siRNA (100 nM each) or RAB31 siRNA (125 nM; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or RUNX1 siRNA (100 nM) plus Rab31 expression plasmid (4 µg; OriGene Technologies) individually and nucleofected by using Amaxa cell line Nucleofector kit V in a Nucleofector 2b device (Lonza, Morristown, NJ). The nucleofected cells were resuspended in the medium supplemented with PMA and incubated at 37°C with 5% carbon dioxide. After 24 hours, medium was aspirated, and cells were gently washed with 1X phosphate-buffered saline, fixed with 4% formaldehyde at room temperature for 15 minutes, and stored at 4°C. In parallel, cells were lysed for immunoblotting.

Immunofluorescence studies.

Platelets and HEL cells were seeded on human plasma fibronectin-coated or poly-l-lysine–coated coverslips. Cells were fixed in phosphate-buffered saline containing 3.7% formaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 before immunostaining with antibodies as described previously.26 Where indicated, cells were exposed to EGF (0.25 μg/mL) for 8 minutes before seeding on coverslips. Cells were stained for markers of EEs (early endosomal autoantigen 1 [EEA1]), late endosome/multivesicular bodies (MVBs) (CD63), and EGFR. The antibodies used are presented in supplemental Table 4. Images were obtained on an EVOS microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or a TCS SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL), using a 63X/1.40 numerical aperture oil immersion objective at room temperature and EVOS or Leica imaging software, respectively. Post-acquisition processing and analysis were performed with Adobe Photoshop and ImageJ32 and were limited to image cropping and brightness/contrast adjustments applied to all pixels per image simultaneously. Particle areas were determined from single-color thresholded images from at least 3 submicron slices per cell with at least 50 cells per type, using ImageJ with at least 50 cells per type; they are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean. The fluorophores used were fluorescein isothiocyanate, Cy3, and Cy5.

Generation of RAB31 knockout HEL cell lines.

Single-guide RNA (sgRNA) pairs targeting RAB31 were designed for targeting and predicted off-target sites using online CRISPR Design (http://crispr.mit.edu/) and CRISPOR (http://www.crispor.org). The annealed sgRNAs were inserted into the AIO-GFP (Cas9) plasmid containing dual U6 promoter-driven sgRNAs and enhanced green fluorescent protein–coupled Cas9 nuclease as described elsewhere.33 The following oligonucleotides were used: sgRNA 1 forward: 5′-CACCGGGACACTGCTGGTCAG GAAC; sgRNA 1 reverse: 5′-AAACGTTCCTGACCAGC AGTGTCCC; sgRNA 2 forward: 5′-CACCGGCTGAGCCTCGATAGTACAT; sgRNA 2 reverse: 5′-AAACATGTACTATCGAGGC TCAGCC. The resulting plasmid was transfected into HEL cells using Nucleofector II (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) following the manufacturer’s instructions. After 24 hours, individual green fluorescent protein–positive cells were single-sorted into wells of a 96-well plate. Clonal knockout cultures were identified and confirmed by target region PCR sequencing and immunoblotting with RAB31 antibodies.

Bioinformatics.

RAB31 sequence (accession number NM_006868) was obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information gene database. Potential binding sites for transcription factors were analyzed by using computer program TFBIND (http://tfbind.hgc.jp).

Statistical analysis for in vitro studies

Results of the in vitro studies are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean. Differences were compared by using the t test.

Results

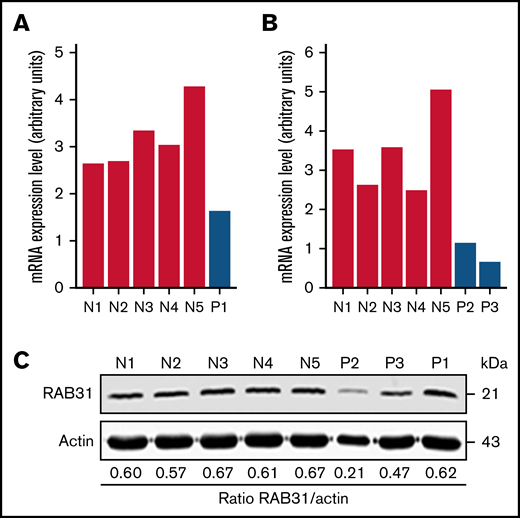

Decreased platelet RAB31 expression in RHD

On platelet expression profiling using Affymetrix U133 Gene Chips, RAB31 expression was decreased in our patient (P1) with a RUNX1 mutation compared with healthy control subjects (fold change, 0.28775; P = .008).21 We validated this by real-time PCR using a fresh sample (Figure 1A). Platelet RAB31 messenger RNA by real-time PCR was decreased in 2 additional patients, P2 and P3 (siblings from an unrelated family with RHD) (Figure 1B). By immunoblotting, platelet RAB31 was decreased in patients P2 and P3 compared with healthy subjects (Figure 1C).

RAB31 expression in platelets from RUNX1-haplodeficient patients (P) and normal control subjects (N). Platelet RAB31 messenger RNA (mRNA) levels by quantitative PCR in the index patient (P1) (A) or in 2 siblings (P2 and P3) from an unrelated family (B) with a RUNX1 mutation compared with 5 normal subjects (N1-N5). mRNA levels normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase expression. (C) Platelet RAB31 by immunoblotting in 3 patients (P1-P3) and 5 healthy subjects (N1-N5). Protein expressions are shown in the ratio of RAB31 to actin.

RAB31 expression in platelets from RUNX1-haplodeficient patients (P) and normal control subjects (N). Platelet RAB31 messenger RNA (mRNA) levels by quantitative PCR in the index patient (P1) (A) or in 2 siblings (P2 and P3) from an unrelated family (B) with a RUNX1 mutation compared with 5 normal subjects (N1-N5). mRNA levels normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase expression. (C) Platelet RAB31 by immunoblotting in 3 patients (P1-P3) and 5 healthy subjects (N1-N5). Protein expressions are shown in the ratio of RAB31 to actin.

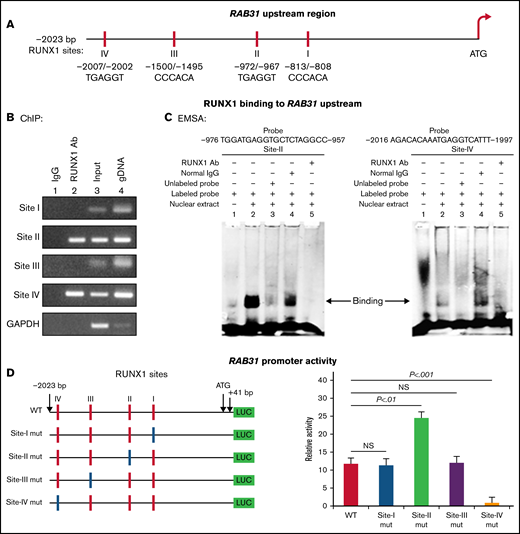

RAB31 regulation by RUNX1

RAB31 promoter sequence (2023 bp from ATG codon) revealed 4 consensus RUNX1 binding sites at 5′-813/-808-3′ (from ATG; Site I), 5′-972/-967-3′ (Site II), 5′-1500/-1495-3′ (Site III) and 5′-2007/-2002-3′ (Figure 2A). The ChIP assay was performed on HEL cell chromatin using an anti-RUNX1 antibody. PCR amplification of chromatin immunoprecipitated with the anti-RUNX1 antibody showed enrichment of promoter regions with site II and site IV; no enrichment was noted with normal IgG (Figure 2B). The chromatin regions containing sites I and III were not enriched. These results indicate that RUNX1 binds to RAB31 promoter.

Characterization of RAB31 promoter. (A) RAB31 promoter region (−2023 bp from ATG codon) showing 4 RUNX1 consensus-binding sites. (B) RUNX1 binding to RAB31 upstream region by ChIP. PCR amplification of HEL cell chromatin immunoprecipitated by IgG (lane 1) and RUNX1 antibody (lane 2); PCR amplification of input or total DNA (lane 3) and amplification of genomic DNA (gDNA) (lane 4) using RAB31 primers. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was amplified as an internal control. (C) EMSA using WT nucleotide probes carrying RUNX1-binding site II (−957/−976; left) and site IV (−1997/−2016; right) in RAB31 promoter and PMA-treated HEL nuclear extracts. EMSA using site II probe (left panel) lane 1, no extract; lane 2, protein binding to the probe; lane 3, loss of protein binding by competition with excess unlabeled probe; lane 4, no loss of binding by competition with normal IgG; and lane 5, loss of protein binding on competition with anti-RUNX1 antibody. EMSA using site IV probe (right panel, lanes 1-5): similar results were obtained with the probe with site II. Representative of 3 independent experiments. (D) Luciferase reporter studies on RAB31 promoter in PMA-treated HEL cells. Left panel: WT RAB31 promoter with 4 RUNX1 sites (red boxes) and constructs with specific mutants (blue boxes). Right panel: shown is luciferase activity. Site II mutation shows increase in activity compared with WT construct; site IV mutation decreased activity, indicating sites II and IV are functional. Presented as mean ± standard error of the mean of 3 independent experiments in triplicate. NS, not significant.

Characterization of RAB31 promoter. (A) RAB31 promoter region (−2023 bp from ATG codon) showing 4 RUNX1 consensus-binding sites. (B) RUNX1 binding to RAB31 upstream region by ChIP. PCR amplification of HEL cell chromatin immunoprecipitated by IgG (lane 1) and RUNX1 antibody (lane 2); PCR amplification of input or total DNA (lane 3) and amplification of genomic DNA (gDNA) (lane 4) using RAB31 primers. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was amplified as an internal control. (C) EMSA using WT nucleotide probes carrying RUNX1-binding site II (−957/−976; left) and site IV (−1997/−2016; right) in RAB31 promoter and PMA-treated HEL nuclear extracts. EMSA using site II probe (left panel) lane 1, no extract; lane 2, protein binding to the probe; lane 3, loss of protein binding by competition with excess unlabeled probe; lane 4, no loss of binding by competition with normal IgG; and lane 5, loss of protein binding on competition with anti-RUNX1 antibody. EMSA using site IV probe (right panel, lanes 1-5): similar results were obtained with the probe with site II. Representative of 3 independent experiments. (D) Luciferase reporter studies on RAB31 promoter in PMA-treated HEL cells. Left panel: WT RAB31 promoter with 4 RUNX1 sites (red boxes) and constructs with specific mutants (blue boxes). Right panel: shown is luciferase activity. Site II mutation shows increase in activity compared with WT construct; site IV mutation decreased activity, indicating sites II and IV are functional. Presented as mean ± standard error of the mean of 3 independent experiments in triplicate. NS, not significant.

EMSA was performed by using HEL nuclear extracts and labeled RAB31 oligos encompassing each RUNX1 consensus site (supplemental Table 2). These studies revealed RUNX1 binding to probes containing sites II and IV (Figure 2C) but not to probes containing sites I and III (not shown). In studies with the labeled probe containing site II, there was protein binding (lane 2), which was competed with excess unlabeled probe (lane 3). The binding was not altered by normal IgG (lane 4) but was inhibited by RUNX1 antibody (lane 5). Similar results were observed in studies with the oligo containing site IV. These findings are consistent with ChIP analysis (Figure 2B). Together, the ChIP and EMSA indicate that RUNX1 binds to consensus sites I and IV. In promoter-reporter studies (Figure 2D), there was a striking loss of promoter activity with mutation of site IV of the RAB31 promoter compared with the WT construct, indicating that this site was functional. Mutation of site II caused enhancement in promoter activity, suggesting that it is a negative regulator. There was no change in promoter activity with mutations of sites I and III.

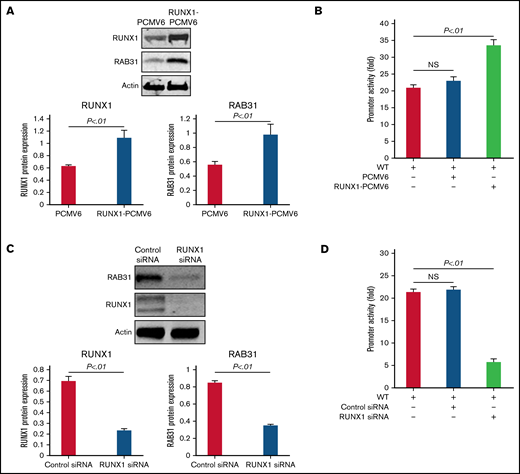

RUNX1 overexpression in HEL cells increased endogenous RUNX1 and RAB31 protein expression (Figure 3A) and RAB31 promoter activity of the WT luciferase construct (Figure 3B). RUNX1 siRNA inhibited endogenous RUNX1 and RAB31 protein expression (Figure 3C) and promoter activity (Figure 3D). Together, these findings indicate that RAB31 is regulated by RUNX1.

Effect of RUNX1 overexpression and RUNX1 depletion by siRNA on RAB31 protein expression and promoter activity. (A) Effect of RUNX1 overexpression. Immunoblotting of RUNX1 and RAB31 of HEL lysates transfected with RUNX1 expression plasmid (RUNX1-pCMV6) and empty plasmid (PCMV6). Actin was the loading control. Presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of 3 independent experiments. (B) Effect of RUNX1 overexpression on promoter activity (luciferase). RAB31 WT promoter construct was cotransfected with RUNX1 expression plasmid or empty plasmid in HEL cells. Promoter activity was enhanced with RUNX1 plasmid. Activity shown as mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments in triplicate. (C) Effect of RUNX1 downregulation (siRNA). Immunoblotting of HEL lysates transfected with control or RUNX1 siRNA. Actin was the loading control. Presented as mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. (D) Effect of RUNX1 siRNA on promoter activity. RAB31 WT promoter construct was cotransfected with control or RUNX1 siRNA. Promoter activity was reduced with RUNX1 siRNA. Presented as mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments in triplicate. RUNX1 siRNA inhibited RAB31 protein expression and promoter activity. NS, not significant.

Effect of RUNX1 overexpression and RUNX1 depletion by siRNA on RAB31 protein expression and promoter activity. (A) Effect of RUNX1 overexpression. Immunoblotting of RUNX1 and RAB31 of HEL lysates transfected with RUNX1 expression plasmid (RUNX1-pCMV6) and empty plasmid (PCMV6). Actin was the loading control. Presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of 3 independent experiments. (B) Effect of RUNX1 overexpression on promoter activity (luciferase). RAB31 WT promoter construct was cotransfected with RUNX1 expression plasmid or empty plasmid in HEL cells. Promoter activity was enhanced with RUNX1 plasmid. Activity shown as mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments in triplicate. (C) Effect of RUNX1 downregulation (siRNA). Immunoblotting of HEL lysates transfected with control or RUNX1 siRNA. Actin was the loading control. Presented as mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. (D) Effect of RUNX1 siRNA on promoter activity. RAB31 WT promoter construct was cotransfected with control or RUNX1 siRNA. Promoter activity was reduced with RUNX1 siRNA. Presented as mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments in triplicate. RUNX1 siRNA inhibited RAB31 protein expression and promoter activity. NS, not significant.

EE defect and altered EGFR endosomal trafficking in RUNX1 or RAB31 deficiency

RAB31 has been reported to regulate EGFR endosomal trafficking in mouse neural progenitor cells.9 We studied the effects of RUNX1 and RAB31 siRNAs in megakaryocytic HEL cells using immunofluorescent staining for markers of EEs (EEA1)34 (Figure 4) and late endosomes/MVBs (CD63)35 and EGFR (Figure 5).

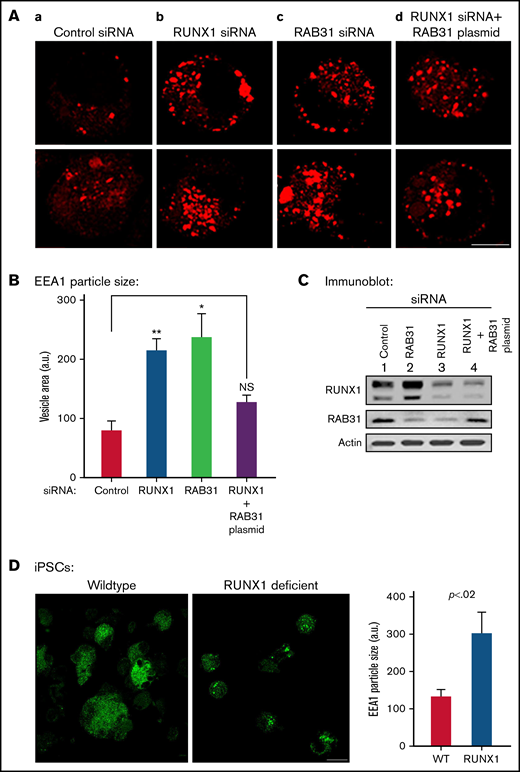

Effect on EE morphology on siRNA knockdown of RUNX1 or RAB31 in megakaryocytic HEL cells and in iMK differentiated from WT and RHD iPSCs. (A) Immunofluorescence studies on the effects of siRNA knockdown of RUNX1 and RAB31 in megakaryocytic HEL cells immobilized on coverslips and stained for EEA1 in: (a) control cells; (b) cells treated with RUNX1 siRNA, showing striking enlargement of EEA1 particles; (c) cells treated with RAB31 siRNA, showing similar alteration in EEs; and (d) RUNX1-depleted cells with RAB31 reconstitution showing partial reversal of EEA1 abnormality. In each column, 2 random examples of cells are shown. (B) Quantification of the size of EEA1 particles with RUNX1 or RAB31 depletion by siRNAs and with RAB31 reconstitution by RAB31 plasmid in RUNX1-depleted cells is shown. Presented as mean ± standard error of the mean of 3 independent experiments. (C) Immunoblotting showing RUNX1, RAB31, and actin (loading control) in control cells and with knockdown of RUNX1 or RAB31 and after RAB31 reconstitution in RUNX1-depleted cells. (D) Early endosomal defect in iMKs differentiated from iPSCs generated from a patient with RUNX1 mutation (RHD) compared with those from WT iPSCs. Scale bar = 10 µm. P values (*P < .001; **P < .0001) are for comparisons with control siRNA. NS, not significant.

Effect on EE morphology on siRNA knockdown of RUNX1 or RAB31 in megakaryocytic HEL cells and in iMK differentiated from WT and RHD iPSCs. (A) Immunofluorescence studies on the effects of siRNA knockdown of RUNX1 and RAB31 in megakaryocytic HEL cells immobilized on coverslips and stained for EEA1 in: (a) control cells; (b) cells treated with RUNX1 siRNA, showing striking enlargement of EEA1 particles; (c) cells treated with RAB31 siRNA, showing similar alteration in EEs; and (d) RUNX1-depleted cells with RAB31 reconstitution showing partial reversal of EEA1 abnormality. In each column, 2 random examples of cells are shown. (B) Quantification of the size of EEA1 particles with RUNX1 or RAB31 depletion by siRNAs and with RAB31 reconstitution by RAB31 plasmid in RUNX1-depleted cells is shown. Presented as mean ± standard error of the mean of 3 independent experiments. (C) Immunoblotting showing RUNX1, RAB31, and actin (loading control) in control cells and with knockdown of RUNX1 or RAB31 and after RAB31 reconstitution in RUNX1-depleted cells. (D) Early endosomal defect in iMKs differentiated from iPSCs generated from a patient with RUNX1 mutation (RHD) compared with those from WT iPSCs. Scale bar = 10 µm. P values (*P < .001; **P < .0001) are for comparisons with control siRNA. NS, not significant.

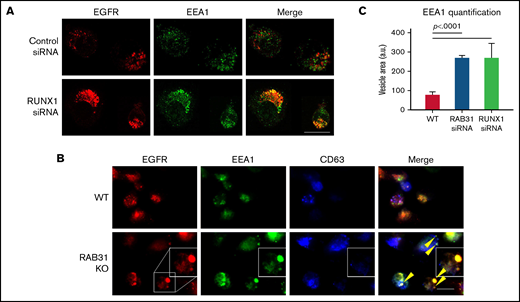

Effect of siRNA RUNX1 knockdown and CRISPR/Cas RAB31 knockout in megakaryocytic HEL cells on EGFR trafficking. (A) Effect of siRNA knockdown of RUNX1. Cells were exposed to EGF (0.25 μg/mL) for 8 minutes, immobilized on coverslips, and stained for EEA1 and EGFR. Compared with WT cells (upper panels), with RUNX1 knockdown (lower panels) there was marked enlargement of EEA1-positive vesicles (green) with colocalization of EGFR (red). (B) CRISPR/Cas9 RAB31 knockout (KO) cells were exposed to EGF for 8 minutes and immobilized on coverslips, and stained for EGFR (red), EEA1 (green), and CD63 (blue). Compared with WT cells (upper panels), with RAB31 KO (lower panels), there was enlargement of EEA1-positive vesicles with colocalization of EGFR, shown by yellow arrows and the insets. There was partial colocalization of EGFR with CD63. (C) Quantification of size of EEA1-positive particles in WT, RUNX1-depleted, and RAB31-depleted cells. Presented as mean ± standard error of the mean of 3 independent experiments. Scale bar = 10 µm.

Effect of siRNA RUNX1 knockdown and CRISPR/Cas RAB31 knockout in megakaryocytic HEL cells on EGFR trafficking. (A) Effect of siRNA knockdown of RUNX1. Cells were exposed to EGF (0.25 μg/mL) for 8 minutes, immobilized on coverslips, and stained for EEA1 and EGFR. Compared with WT cells (upper panels), with RUNX1 knockdown (lower panels) there was marked enlargement of EEA1-positive vesicles (green) with colocalization of EGFR (red). (B) CRISPR/Cas9 RAB31 knockout (KO) cells were exposed to EGF for 8 minutes and immobilized on coverslips, and stained for EGFR (red), EEA1 (green), and CD63 (blue). Compared with WT cells (upper panels), with RAB31 KO (lower panels), there was enlargement of EEA1-positive vesicles with colocalization of EGFR, shown by yellow arrows and the insets. There was partial colocalization of EGFR with CD63. (C) Quantification of size of EEA1-positive particles in WT, RUNX1-depleted, and RAB31-depleted cells. Presented as mean ± standard error of the mean of 3 independent experiments. Scale bar = 10 µm.

With siRNA RUNX1 depletion, there was a striking enlargement of EEA1 particles (Figure 4A-B). Similar findings were noted on siRNA knockdown of RAB31 with increased size of EEA1 particles. This was partially reversed by ectopic expression of RAB31 in RUNX1-depleted cells, suggesting a RAB31 role in the observed alterations. Immunoblotting confirmed the expected knockdown of RUNX1 or RAB31 and RAB31 reconstitution in RUNX1-depleted cells (Figure 4C). RHD-iMKs also showed an increase in EEA1 particle size (Figure 4D), providing evidence of the EE defect.

Exposure of HEL cells to EGF for 8 minutes at 37°C resulted in internalization of membrane EGFR (Figure 5A). In control cells, colocalization of EGFR with EEA1 appeared to be in the perinuclear area where RAB31 has been shown to localize.3,10 On RUNX1 knockdown, there was a prominent increase in EEA1-positive granule size with enrichment by EGFR (Figure 5A,C), suggesting a block in the endocytic pathway at the EEA1 level. To investigate RAB31 role in receptor/vesicle trafficking in HEL cells, we generated RAB31-deleted (knockout) HEL cell lines using CRISPR/Cas9. In RAB31 knockout cells, EEA1 vesicles were enlarged compared with control cells (Figure 5B). In WT cells, EGFR showed partial colocalization with CD63, a marker of late endosome/MVB, and with EEA1. In RAB31 knockout cells, EGFR partially colocalized with EEA1 and strikingly in the enlarged EEA1-positive vesicles (Figure 5B-C). Together, these studies suggested that RUNX1 deficiency and RAB31 knockout induce a marked alteration in EE morphology, attributed to impaired EE maturation,36 and disruption of EGFR trafficking with accumulation in EEs.

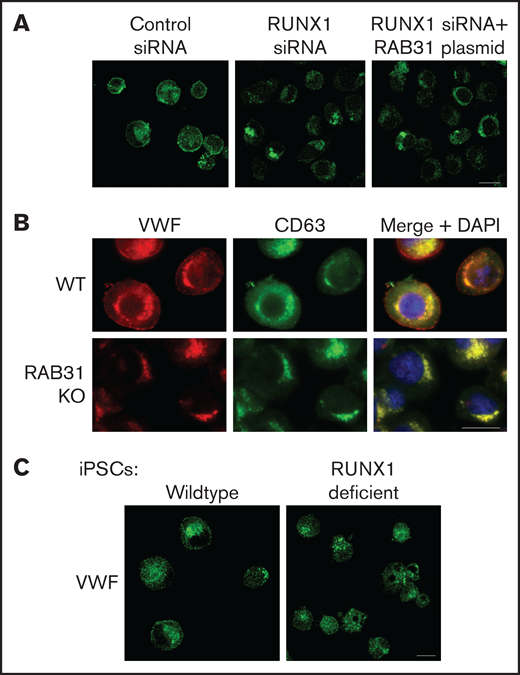

Altered VWF trafficking on in RUNX1- and RAB31-deficient cells

VWF is synthesized by MK and is present in platelet α-granules. In our previous studies,22 VWF trafficking was distorted on knockdown of RUNX1 or of the small GTPase RAB1B, a RUNX1 target, with altered RAB1B-mediated VWF trafficking from endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi. In control HEL cells, there was heterogeneous patterning, and VWF exhibited a combination of a ringed band pattern concentrated near the plasma membrane and was being condensed in the perinuclear area (Figures 6A-B). With siRNA RUNX1 knockdown, the peripheral banding pattern of VWF was absent (Figure 6A) with dispersion in the perinuclear area, indicating altered VWF trafficking. Ectopic expression of RAB31 did not reverse these alterations. In RAB31 knockout cells, there was little to no VWF detectable at the plasma membrane or in CD63– vesicles, whereas perinuclear colocalization with CD63 was prominent (Figure 6B), consistent with accumulation in late endosomes/MVBs. These findings suggest a defect in VWF handling on RAB31 knockout, with loss of plasma membrane VWF and retention in late endosomes/MVBs. Studies in control iMKs (Figure 6C) revealed the plasma membrane banding of VWF, which was lost in RHD-iMKs.

Effect on VWF trafficking in HEL cells of RUNX1 knockdown by siRNA and of RAB31 knockout by CRISPR/Cas targeting, and in iMKs differentiated from WT iPSCs and iPSCs generated from a subject with a RUNX1 mutation. (A) RUNX1-knockdown in HEL cells. PMA-treated HEL cells were nucleofected with control or RUNX1 siRNA and with RAB31 plasmid along with RUNX1 siRNA. They were stained for VWF (green). Cells with control siRNA showed VWF in the perinuclear regions and a band along the plasma membrane, which was lost on RUNX1 knockdown. RAB31 reconstitution did not restore the plasma membrane VWF. (B) RAB31-CRISPR/Cas knockout (KO) in HEL cells. Immunostaining for VWF (red), CD63 (green, late endosome/MVB), and their overlap (yellow). In WT cells. VWF is present in the perinuclear regions and at the plasma membrane as a rim of red dots, with an overlap between VWF and CD63 (yellow). In RAB31 KO cells, VWF was absent at the plasma membrane with an overlap of VWF and CD63-positive areas, suggesting retention of VWF in late endosomes/MVBs and defective VWF trafficking to plasma membrane. (C) iMKs differentiated from WT iPSCs and RHD-iPSCs with RUNX1 mutation were stained for VWF (green). The RHD-iMKs showed a loss of the plasma membrane VWF. Scale bar = 10 µm. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Effect on VWF trafficking in HEL cells of RUNX1 knockdown by siRNA and of RAB31 knockout by CRISPR/Cas targeting, and in iMKs differentiated from WT iPSCs and iPSCs generated from a subject with a RUNX1 mutation. (A) RUNX1-knockdown in HEL cells. PMA-treated HEL cells were nucleofected with control or RUNX1 siRNA and with RAB31 plasmid along with RUNX1 siRNA. They were stained for VWF (green). Cells with control siRNA showed VWF in the perinuclear regions and a band along the plasma membrane, which was lost on RUNX1 knockdown. RAB31 reconstitution did not restore the plasma membrane VWF. (B) RAB31-CRISPR/Cas knockout (KO) in HEL cells. Immunostaining for VWF (red), CD63 (green, late endosome/MVB), and their overlap (yellow). In WT cells. VWF is present in the perinuclear regions and at the plasma membrane as a rim of red dots, with an overlap between VWF and CD63 (yellow). In RAB31 KO cells, VWF was absent at the plasma membrane with an overlap of VWF and CD63-positive areas, suggesting retention of VWF in late endosomes/MVBs and defective VWF trafficking to plasma membrane. (C) iMKs differentiated from WT iPSCs and RHD-iPSCs with RUNX1 mutation were stained for VWF (green). The RHD-iMKs showed a loss of the plasma membrane VWF. Scale bar = 10 µm. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Studies on M6PR in RUNX1- and RAB31-deficient cells

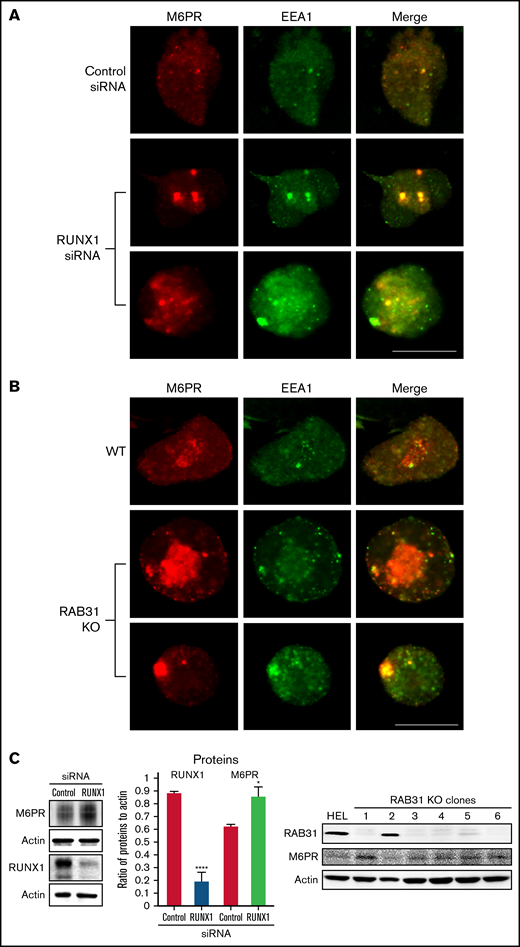

M6PR are transmembrane glycoproteins that regulate trafficking of lysosomal enzymes to lysosomes, where they are degraded.37,38 M6PR binds newly synthesized lysosomal hydrolases in TGN and delivers them to pre-lysosomal compartments. In HeLa cells, RAB31 has been reported to regulate trafficking of calcium-dependent M6PR from TGN to endosomes.10 In the present studies, upon RUNX1 knockdown or RAB31 knockout, there was a markedly increased size of EEA1 particles compared with control cells with colocalization of M6PR with EEA1 (Figure 7A-B). On immunoblotting, M6PR was increased on siRNA RUNX1 knockdown and in 5 of 6 clones of RAB31 knockout cells (Figure 7C), suggesting accumulation of M6PR.

Effect on M6PR trafficking in HEL cells of RUNX1 siRNA knockdown and of RAB31-CRISPR/Cas9 knockout (KO). HEL cells were immobilized on cover slips and immunostained for M6PR (red) and EEA1 (green). Shown are images from confocal microscopy. (A) RUNX1 knockdown. (B) RAB31 KO. Under both conditions, in WT cells there is partial colocalization of M6PR with EEA1. With RUNX1 knockdown or RAB31 KO, there is colocalization of M6PR with enlarged EEA1 particles in the merged images. (C) Left panel: Immunoblotting on HEL lysates transfected with control or RUNX1 siRNA. Actin was used as loading control. Bars show densitometric analysis on immunoblot protein expression. Presented as mean ± standard error of the mean of 4 independent experiments. M6PR expression was increased in RUNX1 siRNA-depleted cells. Right panel: Immunoblotting shows M6PR expression in RAB31-KO (CRISPR/Cas) clones and actin as loading control. M6PR expression was increased in 5 of 6 clones with RAB31 KO. Scale bar = 10 µm. P values indicate comparisons vs control siRNA; *P < .001, ****P < .0001.

Effect on M6PR trafficking in HEL cells of RUNX1 siRNA knockdown and of RAB31-CRISPR/Cas9 knockout (KO). HEL cells were immobilized on cover slips and immunostained for M6PR (red) and EEA1 (green). Shown are images from confocal microscopy. (A) RUNX1 knockdown. (B) RAB31 KO. Under both conditions, in WT cells there is partial colocalization of M6PR with EEA1. With RUNX1 knockdown or RAB31 KO, there is colocalization of M6PR with enlarged EEA1 particles in the merged images. (C) Left panel: Immunoblotting on HEL lysates transfected with control or RUNX1 siRNA. Actin was used as loading control. Bars show densitometric analysis on immunoblot protein expression. Presented as mean ± standard error of the mean of 4 independent experiments. M6PR expression was increased in RUNX1 siRNA-depleted cells. Right panel: Immunoblotting shows M6PR expression in RAB31-KO (CRISPR/Cas) clones and actin as loading control. M6PR expression was increased in 5 of 6 clones with RAB31 KO. Scale bar = 10 µm. P values indicate comparisons vs control siRNA; *P < .001, ****P < .0001.

Discussion

These studies provide the first evidence that small GTPase RAB31 is regulated in megakaryocytic cells by RUNX1 (Figures 2 and 3) and that platelet expression of RAB31 is decreased in patients with RHD (Figure 1). The cell biological roles of RAB31 in MK/platelets are unknown. Our studies show that RAB31 regulates the trafficking of 3 proteins with diverse functions (EGFR, VWF, and M6PR), and their trafficking is defective, with striking alterations in EEs on downregulation of RAB31, as well as of RUNX1, which regulates its expression.

A consistent abnormality noted in our studies on knockdown of RUNX1 or RAB31 in HEL cells was a striking increase in size of EEs (Figures 4-6). This was also noted in RHD-iMKs (Figure 4D). These morphologic changes have been considered as a marker of defective EE maturation.36 This abnormality in RUNX1-deficient cells was reversed, partially rescued by RAB31 (Figure 4A), suggesting a role for RAB31 in the endosomal defect. EEs are one of the earliest endocytic vesicles to receive proteins, and they play a major function in their sorting into subsequent recycling, secretory, and degradative compartments.1,39 Enlarged EEs have been observed in Alzheimer disease and Niemann-Pick disease and are attributed to defective endosomal trafficking.36 Defective fusion of EEs and subsequent fission are postulated to result in the increase in size and number.36,40 We show that RUNX1 deficiency induces a similar defect in MK cells, mediated, at least in part, by RAB31 downregulation.

Our studies provide evidence for a role of RAB31 in the trafficking in megakaryocytic cells of VWF, EGFR, and M6PR, which have distinct roles in cell biology. Their trafficking was altered on RAB31 knockdown along with altered EEs. Studies in non-MK cells have shown that RAB31 regulates protein trafficking from Golgi to early endosomes and to other compartments.8-10 We found EGFR colocalization in the enlarged EEs on downregulation of RUNX1 or RAB31 (Figure 4), consistent with a partial block in trafficking at EEs. Rab31 is a member of the RAB5 family, implicated in early endocytosis.1,39 Because our studies were performed in cells exposed to EGF, which stimulates endocytosis of EGFR, they suggest an effect on the handling of proteins from the surface membrane. This is relevant because platelets/MKs incorporate numerous proteins by endocytosis,41 the mechanism by which fibrinogen and factor V are incorporated into α-granules42 ; neither is synthesized by human MKs.

We provide evidence that RAB31 regulates trafficking of VWF; this is important because VWF is synthesized by MKs and sequestered in α-granules, and defects involving α-granules and their constituents are a hallmark of RHD.18 We have shown that platelet VWF is decreased in patients with RHD and in megakaryocytic cells by RUNX1 downregulation.22 VWF trafficking in megakaryocytic cells is altered by downregulation of RUNX1 and by small GTPase RAB1B (also, a RUNX1 target). We now show a RAB31 role in VWF trafficking, distinct from that of RAB1B. In WT cells, VWF is concentrated near the plasma membrane and in the perinuclear area (Figure 6). With siRNA RUNX1 knockdown, there was a loss of the peripheral membrane banding pattern (Figure 6A). This was also noted in RHD-iMK (Figure 6C). In RAB31 knockout cells, plasma membrane VWF was lost, with prominent perinuclear colocalization with CD63 (Figure 6B), the latter suggesting accumulation in the MVBs/late endosomes. These findings suggest VWF handling is defective on RAB31 knockout. In RUNX1-deficient HEL cells, ectopic RAB31 expression did not rescue the plasma membrane VWF (Figure 6A). We have shown22 that RAB1B regulates VWF trafficking from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi, upstream of the steps recognized to be regulated by RAB31 (from TGN to EE and to late endosome).10 Thus, the effects of RUNX1 knockdown reflect combined alterations in RAB1B and RAB31, and possibly other RUNX1-regulated genes.21 We postulate that the inability of RAB31 to rescue membrane VWF in RUNX1-deficient cells (Figure 6A) may be related to the concurrent aberration in the upstream step (from Golgi to EE) due to RAB1B downregulation.22 Overall, these studies add RAB31 to the list of regulators of VWF trafficking.43

M6PRs regulate trafficking of lysosomal enzymes from the TGN to lysosomes.37,38 On downregulation of RUNX1 or RAB31, there was striking M6PR colocalization in the enlarged EEs, with an increase in cell lysates (Figure 7), suggesting altered trafficking and accumulation. Little is known regarding the role of M6PR in MK/platelets. M6pr−/− mice platelets had structural alterations, increased adhesion to collagen, and decreased heparanase (the predominant platelet lysosomal enzyme) associated with increased plasma levels, consistent with its mistargeting; the mice had a prothrombotic phenotype.44 Interestingly, our previous studies found impaired secretion of lysosomal enzymes by RHD platelets,27 suggesting a potential link to aberrant M6PR trafficking.

α-granule deficiencies are well established in RHD with decreases in several proteins (PF4, β-thromboglobulin, VWF)18,22 ; the mechanisms are not fully understood. They likely reflect alterations in multiple RUNX1-regulated genes. Our studies advance the concept that altered protein trafficking due to downregulation of RUNX1-regulated RAB proteins constitutes a hitherto unrecognized mechanism, along with other mechanisms. For example, PF4 is a transcriptional target of RUNX1,45 and decreased synthesis contributes to the low levels. Platelet albumin and fibrinogen are decreased in RHD, and their platelet endocytosis is impaired.46 Overall, our studies provide new insights into the role of RAB31 in protein trafficking in MK cells, especially of VWF, and advance understanding of the mechanisms underlying the granule defects in RHD.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the patients and their families to these studies, spanning many years.

This study was supported by research funding from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01 HL109568 and R01 HL137376, A.K.R.; R01 HL137207 and HL159006, L.E.G.) and by the American Heart Association Transformational Project Award (20TPA35490278, L.E.G.).

Authorship

Contribution: G.J. and G.M. performed the research, analyzed the data, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript; L.E.G. designed and performed the research, analyzed and interpreted the data with respect to the immunofluorescence studies, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript; J.W. performed the research and analyzed the data with respect to the immunofluorescence studies; M.P.L. performed studies in establishing the RUNX1 mutation in 2 of the patients and revised the manuscript; F.D.C.-C. performed the research and contributed to the manuscript; B.E., D.L.F., and M.P. generously provided the control and patient-derived iPSC lines, and were involved in the iMK studies; A.K.R. conceived, designed, and performed the research, as well as interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript; and all authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: A. Koneti Rao, Sol Sherry Thrombosis Research Center and Section of Hematology, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University, 3420 N. Broad St, 204 MRB, Philadelphia, PA 19140; e-mail: koneti@temple.edu.

References

Author notes

G.J., G.M., and L.E.G. contributed equally to this study.

RAB31 sequence (accession number NM_006868) was obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information gene database.

Requests for data sharing may be submitted to the corresponding author (e-mail: koneti@temple.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.