TO THE EDITOR:

Global protein synthesis rate plays a critical role in the governance of cell growth, metabolism, and tumor cell proliferation. Stabilization of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4F (eIF4F) complex, comprised of the eIF4E/eIF4A/eIF4G subunits, is a hallmark of resistance to anti-BRAF and anti-MEK therapies in several melanoma and colon cancer models.1-3 This occurs through persistent hyper-phosphorylation of the negative regulator 4E-BP1, which leads to release of eIF4E from 4E-BP1 and hyperactivation of eIF4F-mediated translation initiation. Here, we identify casein kinase 1δ (CK1δ) as a novel regulator of mRNA translation and promising target for cancer drug development.

Both CK1δ and CK1ε are components of pre-40S ribosome subunits and are collectively required for the maturation of 40S ribosomes during translation.4 CK1ε is required for translation initiation by upregulating 4E-BP1 phosphorylation in some models of breast cancer.5 However, in lymphoma, knockdown of CK1ε does not significantly impact 4E-BP1 phosphorylation.6 Furthermore, PF4800567, a selective CK1ε inhibitor, failed to repress 4E-BP1 phosphorylation in lymphoma cells.6 These observations question whether CK1ε is broadly involved in regulating translation in cancer models, particularly lymphoma. We present evidence that CK1δ is an activator of translation initiation in models of lymphoma. CK1δ acts by stimulating 4E-BP1 phosphorylation and is associated with the m7G cap. Chemical inhibition of CK1δ strongly inhibits 4E-BP1 phosphorylation, eIF4F complex assembly, and translation initiation and demonstrates potent and specific antilymphoma activity in vitro and in vivo.

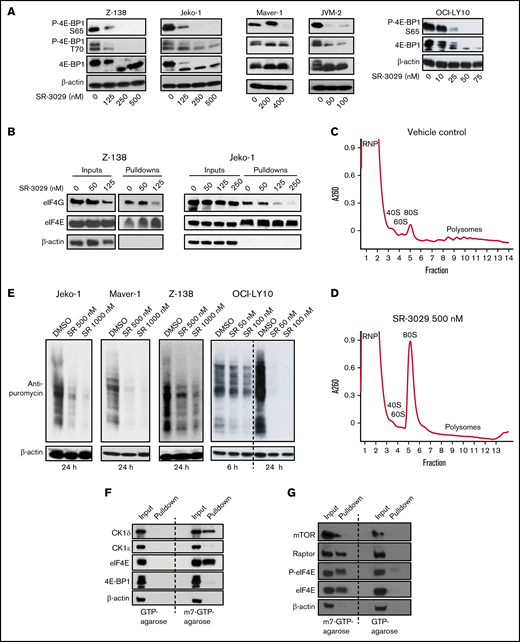

We found that PF670462, a dual CK1ε/CK1δ inhibitor, reduces phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 in the mantle cell lymphoma line Z-138 (supplemental Figure 1A). This result, combined with our previous work targeting CK1ε with a dual inhibitor of PI3Kδ, umbralisib, led us to hypothesize that CK1δ may play an important role in regulating translation initiation in lymphoma via phosphorylation of 4E-BP1. SR-3029 is the most potent selective CK1δ inhibitor that is widely available7 and was used in this study to interrogate these relationships. Consistent with our hypothesis, we found that SR-3029 potently inhibited phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 in Z-138 cells and other lymphoma cell lines representing mantle cell lymphoma (MCL; Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 1B) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL; supplemental Figure 1C).

CK1δ inhibitor SR-3029 downregulates translation initiation. (A) CK1δ inhibition disrupts 4E-BP1 phosphorylation. Five lymphoma cell lines, Z-138, Jeko-1, Maver-1, and JVM-2 (representing mantle cell lymphoma), and OCI-LY10 (representing diffuse large B-cell lymphoma), were treated with SR-3029 or vehicle control for 24 hours. Protein levels were determined by immunoblot. P-, phosphorylated protein. (B) CK1δ inhibition disrupts eIF4F assembly. The lymphoma cell lines Z-138 and Jeko-1 were treated with SR-3029 or DMSO control at the indicated concentrations for 24 hours and then processed for the m7GTP cap binding assay using m7GTP agarose beads to pull down cap binding proteins, which were analyzed by immunoblot. The level of eIF4G reflects eIF4F assembly, whereas the level of eIF4E is constant and serves as the loading control. (C-D) CK1δ inhibition disrupts global translation. Z-138 cells were treated with DMSO vehicle control (C) or SR-3029 500 nM (D) for 6 hours. Cell lysates were fractionated on 10% to 50% sucrose density gradients by centrifugation. The x axis shows fractions collected, and the y axis shows absorbance at OD260. Shown are the ribonucleoprotein particle fraction (RNP), ribosomal subunits (40S, 60S, and 80S), and polysomes. (E) SUnSET translation assay. Bulk translation was determined in 3 MCL cell lines and 1 DLBCL cell line treated with SR-3029 at the indicated concentrations or DMSO control for 24 hours (or 6 and 24 hours in the case of OCI-LY10). Puromycin was then added at the final concentration of 1 μg/mL for 30 minutes. Cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblot using anti-puromycin or anti–β-actin antibodies. (F-G) CK1δ associates with the mRNA cap structure in lymphoma. m7GTP cap binding assays were performed in untreated Z-138 lymphoma cells. (F) Protein levels of CK1δ, CK1ε, eIF4E, 4E-BP1, and β-actin were determined in the input and pulldown fractions by immunoblotting. (G) Protein levels of mTOR, Raptor, eIF4E, P-eIF4E, and β-actin were determined in the input and pulldown fractions by immunoblotting.

CK1δ inhibitor SR-3029 downregulates translation initiation. (A) CK1δ inhibition disrupts 4E-BP1 phosphorylation. Five lymphoma cell lines, Z-138, Jeko-1, Maver-1, and JVM-2 (representing mantle cell lymphoma), and OCI-LY10 (representing diffuse large B-cell lymphoma), were treated with SR-3029 or vehicle control for 24 hours. Protein levels were determined by immunoblot. P-, phosphorylated protein. (B) CK1δ inhibition disrupts eIF4F assembly. The lymphoma cell lines Z-138 and Jeko-1 were treated with SR-3029 or DMSO control at the indicated concentrations for 24 hours and then processed for the m7GTP cap binding assay using m7GTP agarose beads to pull down cap binding proteins, which were analyzed by immunoblot. The level of eIF4G reflects eIF4F assembly, whereas the level of eIF4E is constant and serves as the loading control. (C-D) CK1δ inhibition disrupts global translation. Z-138 cells were treated with DMSO vehicle control (C) or SR-3029 500 nM (D) for 6 hours. Cell lysates were fractionated on 10% to 50% sucrose density gradients by centrifugation. The x axis shows fractions collected, and the y axis shows absorbance at OD260. Shown are the ribonucleoprotein particle fraction (RNP), ribosomal subunits (40S, 60S, and 80S), and polysomes. (E) SUnSET translation assay. Bulk translation was determined in 3 MCL cell lines and 1 DLBCL cell line treated with SR-3029 at the indicated concentrations or DMSO control for 24 hours (or 6 and 24 hours in the case of OCI-LY10). Puromycin was then added at the final concentration of 1 μg/mL for 30 minutes. Cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblot using anti-puromycin or anti–β-actin antibodies. (F-G) CK1δ associates with the mRNA cap structure in lymphoma. m7GTP cap binding assays were performed in untreated Z-138 lymphoma cells. (F) Protein levels of CK1δ, CK1ε, eIF4E, 4E-BP1, and β-actin were determined in the input and pulldown fractions by immunoblotting. (G) Protein levels of mTOR, Raptor, eIF4E, P-eIF4E, and β-actin were determined in the input and pulldown fractions by immunoblotting.

Given the critical role of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation in releasing eIF4E for assembly of the eIF4F complex8 (comprising eIF4G, eIF4E, and eIF4A), the above results led us to question whether SR-3029 may inhibit translation initiation. We first investigated whether SR-3029 affects cap recruitment of eIF4F using a m7GTP cap binding assay.9 In this assay, eIF4E binds directly to the mRNA m7G cap10 and serves as a loading control, whereas the level of eIF4G in the pulldown fraction indicates the efficiency of eIF4F assembly. We observed that SR-3029 substantially reduced the amount of eIF4G pulled down by the m7GTP-agarose beads in the MCL cell lines Z-138 and Jeko-1, without significantly reducing the level of cap-bound eIF4E (Figure 1B). To assess the effects of SR-3029 on global protein synthesis, we conducted polysome profiling analysis. In Z-138 lymphoma cells treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), the 40S, 60S, and 80S ribosome peaks were easily identified, and polysome levels were elevated (Figure 1C). SR-3029 treatment resulted in a substantial increase in the 80S monosome peak at the expense of polysomes indicating that CK1δ inhibition, either directly or indirectly, repressed global translation (Figure 1D).

To further characterize how SR-3029 influences global protein synthesis we performed a surface sensing of translation (SUnSET) assay, in which puromycin was used to terminate translation elongation. The levels of terminated polypeptides can be determined with an anti-puromycin antibody11 and indicate global protein synthesis levels. SR-3029 substantially inhibited incorporation of puromycin in multiple MCL cell lines (Jeko-1, Maver-1, and Z-138) and 1 DLBCL cell line (OCI-LY10; Figure 1E). Collectively, these results suggest that the CK1δ inhibitor SR-3029 represses protein synthesis in lymphoma cells via inhibiting 4E-BP1 phosphorylation and eIF4F assembly.

The above results implicating CK1δ in translation initiation led us to suggest that CK1δ may be associated with the mRNA cap, which we assessed using a m7GTP cap-binding assay. We observed that CK1δ was pulled down by m7GTP agarose beads in Z-138 lymphoma cells in a manner similar to the cap-binding protein eIF4E (Figure 1F). We reasoned that binding of CK1δ and eIF4E to m7GTP beads was specific based on the following criteria: (1) control GTP beads failed to pull down these proteins and (2) CK1ε was not pulled down by m7GTP beads (Figure 1F). The m7GTP beads (but not GTP beads) also pulled down mTOR, Raptor, eIF4E, and phosphorylated eIF4E (Figure 1G), which are components of the translation preinitiation complex (PIC).12 These results suggest that CK1δ is associated with components of the PIC and may regulate translation initiation via this association.

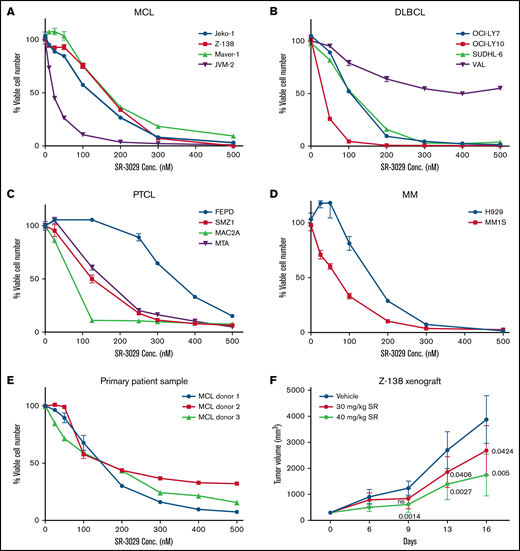

Given the importance of translation in blood cancer cell proliferation and the role of CK1δ in upregulating translation, we reasoned that the CK1δ inhibitor SR-3029 may effectively block tumor growth. We found that SR-3029 potently inhibited the viability of 4 human MCL cell lines using the Cell Titer Glo assay (Figure 2A), with IC50 values at 48 hours in the range of 22.3 to 202.3 nM (supplemental Table 1). SR-3029 also inhibited viability in human cell lines of DLBCL, the most common aggressive lymphoma (Figure 2B). A notable exception was the DLBCL cell line VAL, which was resistant to SR-3029 and lacks 4E-BP-1.13 Presumably, these cells may be able to bypass inhibitors that act via 4E-BP1. Although peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) has a poorer prognosis compared with B-cell lymphomas because of the lack of effective treatment, PTCL cell lines were also sensitive to SR-3029 (Figure 2C). Multiple myeloma (MM) cell lines were highly sensitive to SR-3029 (Figure 2D). Moreover, primary lymphoma cells from patients with MCL were sensitive to SR-3029 (Figure 2E). Importantly, SR-3029 (30-40 mg/kg daily dosing by oral gavage) exhibited a dose-dependent tumor growth inhibition in a mouse xenograft model of MCL, established using Z-138 cells injected subcutaneously in the flank of SCID beige mice (Figure 2F). No significant body weight loss was observed in any treatment group (supplemental Figure 2A) indicating that SR-3029 is well tolerated and that its effects are relatively specific to lymphoma cells in this context.

CK1δ inhibitor SR-3029 potently inhibits tumor growth in broad subtypes of blood cancers. (A-E) SR-3029 potently inhibits viability of lymphomas. Lymphoma cell lines or primary lymphoma cells were treated with SR-3029 or DMSO control at the concentrations indicated on the x axis for 48 hours. Cell viability was quantitated using the Cell-Titer Glo (Promega) assay and is plotted on the y axis. Shown is the average of 3 experiments from the 48-hour treatment, presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. (F) A mouse xenograft model of human lymphoma was established using the Z-138 cell line in SCID beige mice. Tumor volume (y axis) is plotted against the time of treatment (x axis) for 2 treatment cohorts and the vehicle control. P values of the treatment cohorts vs control are indicated as determined by repeated-measure analysis of variance.

CK1δ inhibitor SR-3029 potently inhibits tumor growth in broad subtypes of blood cancers. (A-E) SR-3029 potently inhibits viability of lymphomas. Lymphoma cell lines or primary lymphoma cells were treated with SR-3029 or DMSO control at the concentrations indicated on the x axis for 48 hours. Cell viability was quantitated using the Cell-Titer Glo (Promega) assay and is plotted on the y axis. Shown is the average of 3 experiments from the 48-hour treatment, presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. (F) A mouse xenograft model of human lymphoma was established using the Z-138 cell line in SCID beige mice. Tumor volume (y axis) is plotted against the time of treatment (x axis) for 2 treatment cohorts and the vehicle control. P values of the treatment cohorts vs control are indicated as determined by repeated-measure analysis of variance.

Because SR-3029 has been reported to kill MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells through inhibiting nuclear localization of β-catenin,14 we set out to determine whether SR-3029 had this effect in lymphoma. SR-3029 treatment did not reduce nuclear β-catenin in the MCL cell line Z-138 and DLBCL cell line OCI-LY10 (supplemental Figure 2B-C), despite that SR-3029 potently inhibited phosphorylation of 4E-BP1. Taken together, these results suggest that the broad antilymphoma activity of SR-3029 is mediated primarily by downregulation of translation.

In this study, we demonstrate that CK1δ is a positive regulator of translation initiation. This conclusion is supported by the observations that CK1δ inhibition disrupts 4E-BP1 phosphorylation, eIF4F assembly, and global translation. Furthermore, CK1δ exhibits m7GTP cap-binding activity in a manner similar to eIF4E. A future challenge will be to determine the precise mechanism by which CK1δ stimulates translation initiation in lymphoma cells, which could be direct or indirect, and will require an understanding of the substrate(s) of CK1δ.

We present evidence that blocking translation in blood cancer cells via inhibition of CK1δ may be an innovative strategy to treat broad subtypes of B- and T-cell lymphomas and multiple myeloma. Although SR-3029 may exhibit off-target (CK1δ) effects at high concentrations, at the low concentrations and in the lymphoma models we tested, SR-3029 appears to specifically inhibit CK1δ-mediated translation. In the lymphoma models studied, the effects of CK1δ inhibition do not invoke the mechanism of repressing β-catenin nuclear localization. In breast cancer and possibly some other cancer models, the primary role of CK1δ may be to mediate Wnt/β-catenin signaling as previously reported.14 At the therapeutic effective dose ranges, SR-3029 appears to be well tolerated in mice based on our results and those of previously reported.14 Other observations supporting a favorable therapeutic window include: normal peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy donors were relatively resistant to SR-3029 in contrast to malignant cell lines (supplemental Figure 2D), and CK1δ protein level was more abundant in lymphoma cell lines compared with PBMCs from the healthy donors (supplemental Figure 2E). Although preliminary in nature, these results suggest that the selective CK1δ inhibitor SR-3029 could be developed into a safe and effective treatment for patients with lymphomas that are dependent on dysregulated protein translation. Inhibition of CK1δ may offer a new mechanistic approach for the treatment of hematologic malignancies.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank John Blenis and Lewis C. Cantley for critical reviews.

C.D. is supported by the Columbia University TRx award, Columbia University CTO pilot award, and Columbia University precision medicine pilot award. C.D. is grateful for the philanthropic support from Gloria and Roberto X Hidalgo, James Kofski, and Diane and Joseph Xavier Meehan. M.J. is funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R35-GM-128802. L.E.B. is supported by NIH grant R35 GM124633-01 and the Hirschl Family Trust. This publication was supported in part through National Cancer Institute Cancer Center support grant P30CA013696 and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH, grant UL1TR001873. O.A.O. is an American Cancer Society research professor and was funded in part by NIHG grant R01 FD-R-006814-01.

Contribution: C.D., M.J., L.E.B., I.P., and O.A.O. conceptualized the study; C.D., I.P., M.J., and L.E.B. created the methodology; C.D., I.P., A.M.S.G., M.J., L.E.B., A.G., S.D.S., and L.S. investigated the study; C.D. and L.E.B. wrote the original draft; C.D., L.E.B., M.J., A.G., and O.A.O. reviewed and edited the manuscript; C.D., M.J., L.E.B., and O.A.O. acquired funding; C.D., M.J., L.E.B., and O.A.O. provided resources; and C.D., M.J., L.E.B., and O.A.O. supervised the study.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Changchun Deng, Early Development, Oncology Therapeutic Area Janssen Research & Development, 1400 McKean Rd, Spring House, PA 19477; e-mail: cdeng@its.jnj.com; and Luke E. Berchowitz, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, 701 W 168th St. HHSC 1520, New York, NY 10025; e-mail: leb2210@cumc.columbia.edu.

References

Author notes

Contact the corresponding author for data sharing: leb2210@cumc.columbia.edu.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.