Key Points

Autoimmune hypoglycemia belongs to the clinical spectrum of HHV8+ MCD and rituximab is an effective treatment of this condition.

This rare complication is related to autoantibodies directed toward the insulin receptor and activating the insulin signaling pathway.

Introduction

Castleman disease (CD) is a rare nonclonal lymphoproliferative disorder. Diagnosis is based on histological features.1 Some cases of multicentric Castleman disease (MCD) are related to a polyclonal proliferation of human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8)–infected plasmablasts (called “HHV8+ MCD”), mostly encountered in immunocompromised hosts. The infected cells are uniformly immunoglobulin M and λ positive and locate in the mantle zone of the lymph node. These cells are associated with a marked polyclonal plasma cell infiltrate. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and other cytokine release complications make this condition life threatening.2,3 Numerous autoantibodies can develop during MCD flares, and autoimmune thrombocytopenia, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura4 have been described. We report on autoimmune hypoglycemia as a new autoimmune complication occurring in 5 patients with active HHV8+ MCD. We demonstrate that hypoglycemia is caused by autoantibodies directed toward the insulin receptor (IR) and that rituximab is an effective and safe treatment of this condition.

Methods

Definition of HHV8+ MCD

MCD was defined by the presence of a clinical flare as previously described,5 and node biopsy consistent with HHV8+ MCD.2

Experimental methods, including inhibition of 125I-insulin binding on insulin receptor by the patients’ serum, purification of serum immunoglobulins, effect of patient serum immunoglobulins on insulin signaling, and immunofluorescence characterization of anti-IR immunoglobulin light chains, have been detailed in the supplemental Methods.6-8 This study was approved by the local institutional review board (IMMUNOLYMPH protocol, CLEA-2020-113) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

IL-6 measurement

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) plasma levels were measured using an electrochemiluminescent immunoassay (Roche Diagnostics).

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparison between HHV8+ MCD patients with or without autoimmune hypoglycemia was based on the nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Results and discussion

Patient 1

An 80-year-old man was referred with deterioration of general status and fever. Past medical history was positive for HIV− HHV8+ MCD treated with rituximab 3 years before admission and insulin-treated type 2 diabetes diagnosed 12 years earlier.

Clinical examination revealed generalized supracentimetric lymphadenopathies. Biological features showed elevated levels of acute phase reactants, anemia, polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia, and high HHV8 whole blood viral load (5.8 log copies per mL). Histological examination of a left cervical lymph node showed typical aspects of HHV8+ MCD.

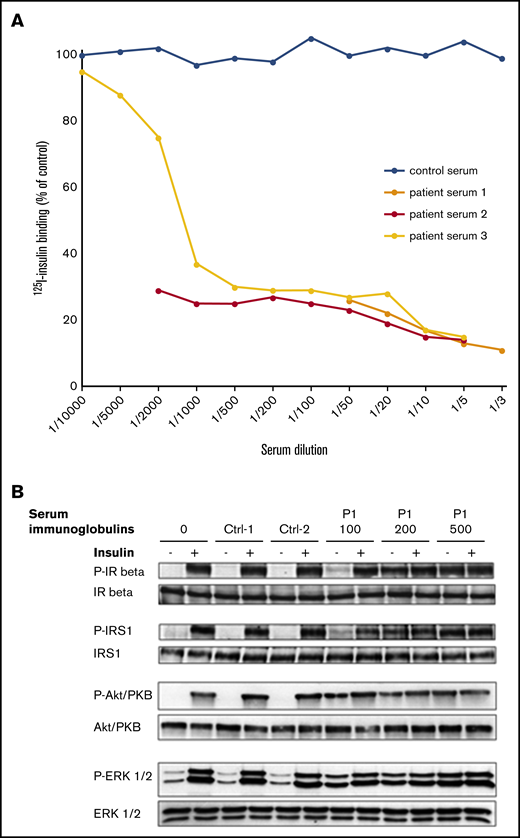

Concomitant to MCD relapse, the patient presented with recurrent fasting hypoglycemia despite discontinuation of insulin therapy for 4 weeks and low levels of endogenous serum insulin and C-peptide. The patient serum was shown to strongly inhibit the binding of insulin to its receptor on Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-IR cells, even at high dilution, so that half-maximal inhibition of insulin binding was observed at a serum dilution of at least 1:1500 (Figure 1A). Inhibition of 125I-insulin binding on IR was retained using purified immunoglobulins from the patient serum (data not shown). Serum immunoglobulins from the patient mimicked the effect of insulin on phosphorylation of IR and IR substrate-1, as well as on activation of the mitogen-activated protein (MAP)–kinase ERK1/2 and the protein kinase B Akt/PKB in CHO-IR cells. The effect was dose dependent and was not induced by control immunoglobulins (Figure 1B). Screening for anti-insulin antibody was negative. Immunofluorescence assay performed on CHO-IR cells showed that both κ and λ light chains colocalized with the IR, indicating that anti-IR antibodies were polyclonal. Control serum used at the same concentration did not show any light chain staining (supplemental Figure 1A,C).

Effects of P1 serum on insulin binding and signaling. (A) Effect of patient 1 serum on 125I-insulin binding to IR. Results from 3 independent experiments. (B) Effect of P1’s serum immunoglobulins (100, 200, and 500 μg/mL as indicated) on insulin signaling. Immunoglobulins from 2 control subjects were used at 200 μg/mL for comparison. Activated (phosphorylated) and total forms of the IR β, the insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS1), the MAP-kinase ERK1/2, and the protein kinase B (Akt-PKB) are evaluated by western blot on lysates from cells incubated or not with insulin, as indicated (see supplemental Methods). Data are representative of 2 independent experiments.

Effects of P1 serum on insulin binding and signaling. (A) Effect of patient 1 serum on 125I-insulin binding to IR. Results from 3 independent experiments. (B) Effect of P1’s serum immunoglobulins (100, 200, and 500 μg/mL as indicated) on insulin signaling. Immunoglobulins from 2 control subjects were used at 200 μg/mL for comparison. Activated (phosphorylated) and total forms of the IR β, the insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS1), the MAP-kinase ERK1/2, and the protein kinase B (Akt-PKB) are evaluated by western blot on lysates from cells incubated or not with insulin, as indicated (see supplemental Methods). Data are representative of 2 independent experiments.

Treatment with etoposide resulted in prompt improvement of fever and polyadenopathy. Short-term evolution was marked by the onset of transitory intense hyperglycemia requiring high-insulin doses compatible with extreme insulin resistance syndrome. The addition of 4-weekly rituximab infusions finally allowed a rapid and durable return to baseline blood sugar levels, and the patient remained free of MCD flares.

Clinical and biological characteristics of 4 additional patients

Between December 2000 and June 2018, 4 patients (patients 2 to 5) presented with recurrent hypoglycemia in the setting of HHV8+ MCD flares. This complication affected 1.9% of the patients included in our HHV8+ MCD cohort consisting of 257 patients. No cases of antibodies to the insulin receptor were reported to be present in 2 large cohorts representing more than 100 HHV8+ MCD patients (M. Bower, British National Centre for HIV Malignancy, London, United Kingdom, and Mario Corbellino, III Division of Infectious Diseases, FBF-Sacco Hospital, Milan, Italy, e-mail communication, 29 July 2020). Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Hypoglycemia clinical signs were psychomotor retardation in 4 patients with altered consciousness in one of them. Other causes of hypoglycemia, such as insulinoma, IGF-1–producing tumors, and adrenal insufficiency, had been ruled out. No acanthosis nigricans was noted. No patient had a previous history of diabetes. Two patients were HIV infected. A HIV− patient was concomitantly diagnosed with a bone marrow localization by a low-grade B-cell lymphoma. In 2 of 5 patients, hypoglycemia was concomitant of the first flare of HHV8+ MCD. All patients had a presentation suggesting HHV8+ MCD flare at hypoglycemia onset. All of them showed polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia, and 2 had evidence of low-level IgGκ (patient 1) and IgAκ (patient 5) monoclonal components. Of note, all patients displayed slightly significant higher gammaglobulin levels than the 252 other patients diagnosed with HHV8+MCD issued from our cohort (median: 34 g/L vs 23.5 g/L; P = .04). Median C-reactive protein (CRP) level was lower in the described patients compared with 252 patients diagnosed with HHV8+ MCD issued from our cohort (50 mg/L vs 131 mg/L; P = .009). This latter result has uncertain significance because of quick fluctuations of CRP levels occurring in HHV8+ MCD. These results need to be taken cautiously because of the small sample of patients with autoimmune hypoglycemia. Diagnosis of HHV8+ MCD was confirmed on lymph node biopsy in the 4 patients. Patient 3 also presented with mild cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma lesions. Two patients had other clinical or biological autoimmune manifestations detailed in Table 1. No anti-insulin antibody was found.

Characteristics of patients at hypoglycemia onset

| . | Patient 1 . | Patient 2 . | Patient 3 . | Patient 4 . | Patient 5 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 80 | 24 | 72 | 72 | 55 |

| Sex | Male | Male | Male | Male | Male |

| Date of hypoglycemia diagnosis | 2015 | 2000 | 2012 | 2017 | 2018 |

| MCD, y since diagnosis | 3 | 4 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| Clinical presentation | Fever | Splenomegaly | Fever | Splenomegaly | Splenomegaly |

| Adenopathy | Adenopathy | Adenopathy | Adenopathy | Adenopathy | |

| Coma | |||||

| CRP, mg/L | 117 | 5 | 200 | 50 | 37 |

| IL-6, pg/mL | NA | 31.9 | NA | NA | 33 |

| Gammaglobulin, g/L | 58.9 | 20.8 | 18.4 | 34 | 65 |

| KS, at diagnosis | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| HHV8 RT-PCR (log) | 5.8 | 4.78 | +* | +* | 6.29 |

| HIV, y since diagnosis | † | 14 | † | 12 | † |

| CD4, mm−3 | † | 330 | † | 432 | † |

| HIV viral load, copies per mL | † | 2210 | † | 47 | † |

| Glycemia, mmol/L | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.05 | 1.6 | 3.4 |

| Insulin, mIU/L | 2.84 | 4.1 | 290 | 242 | NA |

| C-peptide, nmol/L | <0.10 | <0.10 | 1.491 | 3.3 | NA |

| Anti-IR Ab | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Inhibition of insulin binding | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Anti-insulin Ab | No | No | No | No | No |

| Other immune manifestations | No | No | No | wAIHA | wAIHA, lupus anticoagulant |

| . | Patient 1 . | Patient 2 . | Patient 3 . | Patient 4 . | Patient 5 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 80 | 24 | 72 | 72 | 55 |

| Sex | Male | Male | Male | Male | Male |

| Date of hypoglycemia diagnosis | 2015 | 2000 | 2012 | 2017 | 2018 |

| MCD, y since diagnosis | 3 | 4 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| Clinical presentation | Fever | Splenomegaly | Fever | Splenomegaly | Splenomegaly |

| Adenopathy | Adenopathy | Adenopathy | Adenopathy | Adenopathy | |

| Coma | |||||

| CRP, mg/L | 117 | 5 | 200 | 50 | 37 |

| IL-6, pg/mL | NA | 31.9 | NA | NA | 33 |

| Gammaglobulin, g/L | 58.9 | 20.8 | 18.4 | 34 | 65 |

| KS, at diagnosis | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| HHV8 RT-PCR (log) | 5.8 | 4.78 | +* | +* | 6.29 |

| HIV, y since diagnosis | † | 14 | † | 12 | † |

| CD4, mm−3 | † | 330 | † | 432 | † |

| HIV viral load, copies per mL | † | 2210 | † | 47 | † |

| Glycemia, mmol/L | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.05 | 1.6 | 3.4 |

| Insulin, mIU/L | 2.84 | 4.1 | 290 | 242 | NA |

| C-peptide, nmol/L | <0.10 | <0.10 | 1.491 | 3.3 | NA |

| Anti-IR Ab | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Inhibition of insulin binding | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Anti-insulin Ab | No | No | No | No | No |

| Other immune manifestations | No | No | No | wAIHA | wAIHA, lupus anticoagulant |

Ab, antibody; KS, Kaposi sarcoma; NA, not available; RT-PCR, real-time polymerase chain reaction; wAIHA, warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia.

HHV8 qualitative evaluation.

Not appropriate (HIV−).

Characterization of anti-IR antibodies

Anti-IR antibody was isolated in the 4 additional patients and resulted in inhibition of insulin binding (data not shown). Characterization of antibody isotype by immunofluorescence staining in P5 showed a polyclonal pattern as in P1 (supplemental Figure 1B).

Disease course

Four patients were treated with 4-weekly rituximab infusions, and one was lost to follow-up. This treatment correlated with rapid remission of autoimmune hypoglycemia. Disappearance of anti-IR autoantibodies was observed in the 3 patients for whom follow-up samples were available. No relapse occurred in these 3 patients.

Discussion

Type B insulin resistance syndrome, more aptly named “syndrome of antibodies to the insulin receptor,” is caused by autoantibodies directed toward the IR. It can be primary or secondary to connective tissues diseases or malignancies.6,8-13 Common presentation is severe hyperglycemia requiring extremely high insulin doses associated with widespread acanthosis nigricans, weight loss, and hyperandrogenism, but hypoglycemia may also occur.7,8,11

We report 5 cases of symptomatic autoimmune hypoglycemia occurring during HHV8+ MCD flares that were reversible using MCD therapy. Anti-IR antibodies were identified in all samples leading to inhibition of insulin binding. Agonistic effect of this antibody could be biochemically demonstrated in 2 patients. Interestingly, following etoposide administration, patient 1 developed hyperglycemia requiring very high doses of insulin. The occurrence of both hypoglycemic and hyperglycemic episodes in the same patient was previously described during the course of type B insulin resistance syndrome.7,8,11 Pathophysiological hypotheses have involved the coexistence of activating and blocking autoantibodies and/or modifications in antibody titers leading to insulin-like or desensitization effects.11,14 Return to baseline blood glucose levels was achieved after rituximab administration and was concomitant to antibody disappearance in the serum.12-15 This latter point suggests that the observed hyperglycemic state was, at least partially, linked to the effect of the antibody.

To date, only 1 patient with hypoglycemia has been previously described in association with HIV− HHV8+ MCD, and no specific etiology was retained.16 This singular autoimmune complication seems to be restricted to HHV8+ MCD, as it has never been reported in HHV8− idiopathic variant of MCD. We suggest that HHV8 itself may not be the sole trigger, as autoimmune hypoglycemia appears to be closely related to HHV8+ MCD and has never been reported in other HHV8-associated diseases. This latter point makes cross-reactivity between HHV8 and the insulin-receptor–shared epitopes less likely than the emergence of an anti-IR–secreting plasma-cell driven by HHV8. Moreover, the finding of both κ and λ light chains colocalizing with the IR in patients 1 and 5 rules out its sole secretion by HHV-8–infected B cells, which are uniformly IgM-λ+cells.17,18 This finding was in accordance with the IgG isotype of anti-ADAMTS13 antibody found in MCD-associated thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.4 This may rather indicate that high human IL-6 secretion, a hallmark of MCD, could promote the occurrence of self-reacting plasma cells, as suggested by human IL-6 transgenic mice studies.19 HHV8+ MCD is also associated with the secretion of HHV8-related viral IL-6, that might exert additional effects on plasma cell growth.20

Autoimmune hypoglycemia belongs to the clinical spectrum of HHV8+ MCD and should be carefully sought in patients with neurological impairment in this setting. On the other hand, HHV8+ MCD should also be ruled out in patients presenting with fever and unexplained hypoglycemia. Rituximab is effective in the treatment of type B insulin resistance syndrome14 and is also the preferred treatment of HHV8+ MCD. This justified the use of the drug in this particular setting, which was shown to be an effective and safe strategy.

For data sharing, please contact the corresponding author at david.boutboul@aphp.fr.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Romain Morichon (UMS LUMIC platform, Sorbonne Université, Centre de Recherche Saint-Antoine, INSERM U938, Paris, France) for confocal microscopy, Mark Bower and Mario Corbellino for sharing helpful information on HHV8+ MCD patients, and Constance Guillaud, Justine Poirot, and Mirlinda Berisha for technical support.

Authorship

Contribution: P.A. and D. Boutboul wrote the manuscript; P.A., D. Boutboul, L. Galicier, C.B., C.F., E.B., V.Q.-M., L.C., N.B., M.M., J.F., R.B., L. Gérard, and E.O. contributed to the patient recruitment and management; M.A., C.V., D. Bengoufa, and D. Boutboul performed the experiments and analyzed the data; S.F. performed IL-6 dosage and analyzed the data; L. Gérard performed statistical analysis; C.V. and D. Boutboul supervised the project; and all the authors reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: David Boutboul, Clinical Immunology Department, Hôpital Saint Louis, 1 Av Claude Vellefaux, Université de Paris, 75010 Paris, France; e-mail: david.boutboul@aphp.fr.

References

Author notes

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.