Key Points

CD11c/CD18 is expressed on short-term hematopoietic stem cells and multipotent progenitor cells.

Additionally, CD11c/CD18 plays a role in the homeostasis of HSPCs under stress.

Abstract

β2 integrins are well-known leukocyte adhesion molecules consisting of 4 members: CD11a-d. Their known biological functions range widely from leukocyte recruitment, phagocytosis, to immunological synapse formation, but the studies have been primarily focused on CD11a and CD11b. CD11c is 1 of the 4 members and is extremely homologous to CD11b. It has been well known as a dendritic cell marker, but the characterization of its function has been limited. We found that CD11c was expressed on the short-term hematopoietic stem cells and multipotent progenitor cells. The lack of CD11c did not affect the number of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) in healthy CD11c knockout mice. Different from other β2 integrin members, however, CD11c deficiency was associated with increased apoptosis and significant loss of HSPCs in sepsis and bone marrow transplantation. Although integrins are generally known for their overlapping and redundant roles, we showed that CD11c had a distinct role of regulating the expansion of HSPCs under stress. This study shows that CD11c, a well-known dendritic cell marker, is expressed on HSPCs and serves as their functional regulator. CD11c deficiency leads to the loss of HSPCs via apoptosis in sepsis and bone marrow transplantation.

Introduction

CD11c/CD18 (CD11c; also called αXβ2, complement receptor 4, p150,90; gene Itgax) is a member of leukocyte adhesion molecule β2 integrins. β2 integrins consist of 4 members CD11a/CD18 (CD11a, αLβ2, leukocyte function-associated antigen-1; gene Itgal), CD11b/CD18 (CD11b, αMβ2, macrophage-1 antigen; gene Itgam), CD11c, and CD11d/CD18 (CD11d, αDβ2; gene Itgad). They are heterodimeric molecules consisting of different α-subunit (CD11a-d) and the same β-subunit (CD18). The top domain of the α subunit is called the I domain and serves as a ligand-binding domain. Conformational change of the I domain into its active form and resultant binding of these integrins to their ligands activates biochemical and mechanical signaling called “outside-in” signals into the cell to regulate multiple cellular functions.1,2 The biological importance of β2 integrins in leukocyte functions is undoubtedly appreciated from the genetic disease leukocyte adhesion deficiency type I (LAD I), an autosomal-recessive disorder caused by mutations of β2 integrins, which results in defective β2 integrins or deficient level of β2 integrins and is characterized by recurrent infection.3,4 Among the 4 members, CD11a and CD11b have been extensively studied. CD11a is ubiquitously expressed on leukocytes and involved in a number of important functions in leukocytes, including trafficking and immunological synapse formation.5,6 CD11b is mainly expressed on innate immune cells and plays a role in their recruitment, phagocytosis, and cell death.7-10 In contrast to CD11a and CD11b, CD11c has been primarily used as a marker of dendritic cells (DCs),11 and the study on its physiological function has been limited.

CD11b and CD11c are predicted to arise from gene duplication event.12 CD11a is less homologous to CD11b-d.13 The identity of the ligand-binding domain and the β-propeller domain between CD11b and CD11c is high (∼77%).14 CD11b and CD11c recognize overlapping ligands including iC3b, denatured proteins, fibrinogen, and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1).15-21 CD11b is predominantly expressed on myeloid cells, and is also expressed on natural killer (NK) cells, mast cells, a subset of T and B cells.21 CD11c is most abundant on DCs. In addition, its expression has been reported on a subset of macrophages, NK cells, T cells, and B cells. Whether these 2 highly homologous molecules that share many common ligands have distinct functions remains unknown. Some differences between them have been described in vitro. CD11c has better accessibility to negatively charged residues of ligands than CD11b.20 The cytoplasmic domain of CD11b has only 56% identity with that of CD11c and is less than two-thirds of the size of the CD11c cytoplasmic domain, suggesting that they might interact with different intracellular proteins.22 Knowing these differences, both CD11b and CD11c are involved in adhesion, phagocytosis, and podosome formation in vitro.23 Although the involvement of CD11b in adhesion and phagocytosis has been well described in vivo,24,25 CD11c function in vivo remains to be determined.

Sepsis remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality with an annual cost of $20.3 billion dollars, accounting for nearly one-fifth of the total aggregate costs in all hospitalizations in the United States.26 A large number of clinical trials to modify the systemic inflammatory response in sepsis have shown limited success.27 The Surviving Sepsis Campaign’s guidelines for the management of severe sepsis and septic shock have been widely implemented,28-30 but the mortality from sepsis remains high, ranging from 20% to 30%31-33 with questionable benefit of goal-directed protocol-based care,31,33 indicating the need for targeted therapy. We previously studied the role of CD11a and CD11b in infection using the experimental polymicrobial abdominal sepsis model. We found that CD11a deficiency attenuated neutrophil migration to the peritoneal cavity and CD11b deficiency mitigated neutrophil phagocytic ability.34-36 Both deficiencies worsened the outcome of the experimental sepsis. However, the role of CD11c in sepsis pathology has been largely unknown.

Here, we examined the role of CD11c in sepsis pathology using the experimental polymicrobial abdominal sepsis and systemic lipopolysaccharide (LPS) injection models. Unexpectedly, we found a novel and unique role of CD11c in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell (HSPC) function. CD11c expression was confirmed on both mouse and human HSPCs. Its deficiency did not affect the number of HSPCs at naive state but was associated with the loss of HSPC population in both models. Numbers of differentiated peripheral blood leukocytes were significantly reduced in the sepsis model. Apoptosis was involved in the loss of HSPCs. The mixed chimeric study also confirmed the critical role of CD11c in the regulation of HSPC population.

Material and methods

Mice

CD11a−/−, CD11b−/−, and CD11d−/− mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. C57BL/6 CD45.1 and CD45.2 mice were also purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. CD11c−/− mice were kindly given by Christie Ballantyne (Baylor University). ICAM-1−/− mice were kindly given by Gregory Priebe (Boston Children’s Hospital). They were housed under specific pathogen-free condition, with 12-hour light and dark cycles. All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Boston Children’s Hospital. Male mice were used in this study.

Abdominal sepsis model

All experimental procedures complied with institutional and federal guidelines regarding the use of animals in research. Polymicrobial abdominal sepsis was induced by cecal ligation and puncture surgery, as we previously performed.36 In brief, mice were anesthetized with ketamine 60 mg/kg and xylazine 5 mg/kg given intraperitoneally (IP). Following exteriorization, the cecum was ligated at 1.0 cm from its tip and subjected to a single, through-and-through puncture using a 20-gauge needle. A small amount of fecal material was expelled with gentle pressure to maintain the patency of puncture sites. The cecum was reinserted into the abdominal cavity; 0.1 mL/g warmed saline was administered subcutaneously. Buprenorphine was given subcutaneously to alleviate postoperative surgical pain.

Flow cytometry analysis of hematopoietic progenitor cells

Whole bone marrow cells were isolated from mice and stained on ice with various antibody cocktails to identify progenitor compartment. According to the literature,37-39 the lineage marker for mouse bone marrow neutrophil maturation study includes anti-mouse CD3 (mCD3; 145-2C11), anti-mCD19 (ID3), anti-mCD115 (AFS98), anti-mNK1.1 (PK136), and anti-mSiglecF (ES22-10D8; Miltenyi, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany); lineage marker for mouse hematopoietic system includes anti-mCD11b/human CD11b (hCD11b) (M1/70), anti-mGr-1 (RB6-8C5), anti-mCD3 (145-2C11), anti-CD4 (RM4-5), anti-CD8 (53-6.7), anti-mB220 (RA3-6B2), anti-mNK1.1 (PK136), and anti-mTer119 (TER-119). The other anti-mouse antibodies include anti-mCD45.1 (A20), anti-mCD45.2 (104), anti-mIgM (R6-60.2), anti-mCXCR2 (SA045E1), anti-mCXCR4 (L276F12), anti–mC-Kit (2B8), anti-mSca-1 (D7), anti-mCD34 (RAM34), anti-mCD150 (TC15-12F12.2), anti-mCD48 (HM48-1), anti-mFcR (93), anti-mIL7Ra (A7R34), anti-mCD11c (N418), and its isotype control hamster IgG1 (A19-3). Human bone marrow cells and whole blood were purchased from AllCells (Quincy, MA). Lineage marker for human hematopoietic system includes: anti-hCD2 (RPA-2.10), anti-hCD3 (OKT3), anti-hCD4 (RPAT4), anti-hCD7(CD7-6B7), anti-hCD8 (RPAT8), anti-hCD10 (HI10a), anti-hCD11b (M1/70), anti-hCD14 (M5E2), anti-hCD19 (HIB19), anti-hCD20 (2H7), anti-hCD56 (N901; Immunotec, Vaudreuil-Dorion, Canada), and anti-hGPA (HI264). The other anti-human antibodies include anti-hCD38 (HIT2), anti-hCD34 (561), anti-hCD90 (5E10), anti-hCD45RA (HI100), anti-hIL7Ra (A019D5), anti-hCD11c (Bu15), and its isotype control (MG2b-57). If not specified, the antibodies were purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA) and BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ). Cell counting was done by applying Sphero AccuCount beads (ACBP-50-10; Spherotech Inc, Lake Forest, IL). Data were acquired on a Canto II cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (FlowJo LLC, Ashland, OR).

Proliferation and apoptosis assay

Proliferation of cells was examined either with Ki67 staining or 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) staining. Mice were injected IP with 1 mg of BrdU. To detect BrdU incorporation into bone marrow hematopoietic cells, BD cytofix/cytoper Plus kit (555028; BD Biosciences) and Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-BrdU antibody (3D4; BioLegend) were applied according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were subjected to flow cytometry analysis. For Ki67, cells were intracellular stained with anti-m Ki67 antibody (11F6; BioLegend). Apoptosis was detected with intracellular staining of active caspase-3 antibody (559341; BD Biosciences).

RNA-sequencing experiments

LSK cells were sorted by FACSAria system and subjected to RNA purification using Qiagen RNeasy Plus Mini kits. RNA samples were quantified using Qubit 2 Fluorometer (Life Technology, Carlsbad, CA) and RNA integrity was checked with Agilent TapeStation (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). SMART-Seq v4 Ultra Low Input kit for Sequencing was used for full-length complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis and amplification (Clonetech, Mountain View, CA), and Illumina Nextera XT library was used for sequencing library preparation. Briefly, cDNA was fragmented, and adaptor was added using transposase, followed by limited-cycle polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to enrich and add index to the cDNA fragments. The final library was assessed with Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer and Agilent TapeStation. The sequencing libraries were multiplexed and clustered on 1 lane of a flow cell. After clustering, the flow cell was loaded on the Illumina HiSeq instrument according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The samples were sequenced using a 2 × 150 paired-end configuration. After investigating the quality of the raw data, sequencing reads were trimmed to remove possible adapter sequences and nucleotides with poor-quality using Trimmomatic v.0.36. The trimmed reads were mapped to the mouse reference genome using STAR aligner v.2.5.2b. Only unique reads that fell within exon regions were counted. After extraction of gene hit counts, the gene hit count table was used for downstream differential expression analysis. Using DESeq2, a comparison between the groups of samples was performed. The Wald test was used to generate P value and log2 fold changes. Genes with adjusted P < .05 and absolute log2 fold change >1 were called differentially expressed genes.

Systemic LPS injection model

Mice were subjected to LPS (from Pseudomonas aeruginosa 10, 10 mg/kg; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) injection via tail vein. Mice were euthanized at different time points for analysis. In some experiment, Z-Val-Ala-As-fmk (Z-VAD-fmk) (10 mg/kg; Selleck, Houston, TX) IP was given 1 hour prior to LPS injection.

Bone marrow histology

Naive or LPS (10 mg/kg) injected WT or CD11c−/− mice were subjected to bone marrow histology analysis. Mice assigned to LPS injection were euthanized at 4 hours after LPS injection. Extracted femoral bone was subjected to 4% paraformaldehyde treatment of 2 days, then to 0.25 M ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid for 2 weeks. Bone samples that were cut longitudinally into 5-µm slices using a Leica Cryostat were stained with goat polyclonal anti–c-kit antibody (AF1356; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and rabbit polyclonal anti-laminin antibody (AB2034; Sigma) as primary antibody, followed by donkey polyclonal anti-goat IgG-DyLight488 antibody and donkey polyclonal anti-rabbit DyLight650 antibody (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA) as secondary antibodies. Nuclei was stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; ThermoFisher). Images were obtained with Pannoramic MIDI II (3DHISTECH Ltd, Budapest, Hungary). Images were analyzed with Caseviewer software (3DHISTECH Ltd).

Chimeric mouse experiments

To generate mixed bone marrow chimeras, recipient mice on the C57BL/6 background were irradiated with 2 doses of 550 rad with 4-hour intervals. Wild-type (WT; CD45.1) and WT (CD45.2) derived bone marrow cells or WT (CD45.1) and CD11c−/− (CD45.2) derived bone marrow cells were mixed at the ratio of 1:1 with total of 5 × 106 cells and IV injected into the tail vein of lethally irradiated recipients. Mice were evaluated for the reconstitution of the immune compartment at various time points after bone marrow transplantation. To prevent bacterial infection, the mice were provided with autoclaved drinking water containing Sulfatrim for 1 week prior to and for 4 weeks after irradiation.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed as indicated in the figure legends. Statistical significance was defined as P < .05. All the statistical calculations were performed using PRISM 5 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Results

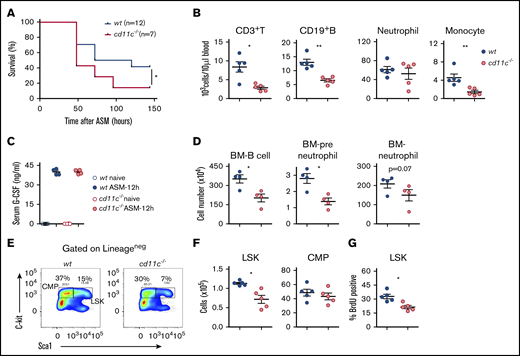

CD11c deficiency led to the loss of HSPCs and worsened the sepsis outcome

We examined the role of CD11c in the severe polymicrobial abdominal sepsis model (ASM) induced by cecal ligation and puncture surgery, which best recapitulates human sepsis.40 CD11c−/− mice demonstrated higher mortality from sepsis than WT mice (Figure 1A). There was no difference in neutrophil, monocyte, T- and B-cell count at baseline (data not shown). The number of peripheral blood neutrophils, monocytes, T cells, and B cells was much lower in CD11c−/− mice at 36 hours after cecal ligation and puncture surgery (Figure 1B), indicating that less circulating leukocytes were available for them to eradicate microbes. In acute infection, neutrophils act as the first-line defense mechanism. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) stimulates HSPC activity and facilitates neutrophil production.41 As expected, G-CSF levels significantly increased following sepsis (Figure 1C). However, no difference in G-CSF levels was observed between WT and CD11c−/− mice (Figure 1C). Because the number of both myeloid- and lymphoid-lineage cells was lower in peripheral blood, we examined the bone marrow and surprisingly found that the number of both neutrophil progenitors (preneutrophils), neutrophils and B cell were already significantly less in CD11c−/− mice following sepsis (Figure 1D). Hence, we hypothesized that CD11c deficiency might have impacted emergency granulopoiesis.42 The analysis of lineage-negative population showed that the absolute numbers of Lineage−sca-1+c-kit+ (LSK) cells were significantly reduced in CD11c−/− mice compared with WT mice (Figure 1E-F). Lineage−Sca-1− c-kit+ cells consist of myeloid progenitor cells.43 The percentage of common myeloid progenitor (CMP) cells in the lineage-negative population was significantly less in CD11c−/− mice (data not shown). The total number of CMP cells was not statistically different between WT and CD11c−/− mice, though the mean was lower in CD11c−/− mice. To explain the loss of LSK cells in CD11c−/− mice, we studied the proliferation of bone marrow cells by in vivo BrdU labeling in both WT and CD11c−/− mice that were subjected to sepsis induction. The ratio of BrdU+ cells among LSK cells, but not among CMP cells was significantly less in CD11c−/− mice at 24 hours after the surgery (Figure 1G). These results suggested that CD11c−/− mice experienced impaired HSPC proliferation in the setting of the experimental polymicrobial sepsis compared with WT mice.

CD11c deficiency impairs HPSCs in the experimental polymicrobial abdominal sepsis model. Both WT and CD11c−/− mice were subjected to polymicrobial abdominal sepsis (ASM) induced by cecal ligation and puncture surgery. (A) Sepsis survival. Shown is 1 of 2 independent experiments with the same pattern. (B) Blood leukocyte counts at 36 hours after surgery. (C) Sera collected before or at 12 hours after surgery was measured for G-CSF by ELISA. (D) Bone marrow (BM) B-cell, preneutrophil, and mature neutrophil counts at 36 hours after surgery. Preneutrophils were identified as Lin−CD115−SiglecF−Gr-1+CD11b+CXCR4hic-kitintCXCR2− and mature neutrophils were identified as Lin−CD115−SiglecF−Gr-1+CD11b+CXCR4−c-kit−CXCR2+.66 (E) Representative flow cytometry plot of LSKs and CMPs identified by costaining c-kit and sca-1 in lineage-negative BM cells. (F) Absolute number of LSKs and CMPs in 2 femurs of WT and CD11c−/− mice at 24 hours after surgery. (G) Proliferation profile. At 20 hours after surgery, mice were pulsed with BrdU for an additional 4 hours, then analyzed for BrdU incorporation in the BM cells. (B-D,F-G) Symbols indicate individual mice. Data are representative of 2 experiments. Error bars indicate ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was tested with the log-rank test (A), Student t test (B,D,F-G), and 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post hoc analysis (C). *P < .05; **P < .01.

CD11c deficiency impairs HPSCs in the experimental polymicrobial abdominal sepsis model. Both WT and CD11c−/− mice were subjected to polymicrobial abdominal sepsis (ASM) induced by cecal ligation and puncture surgery. (A) Sepsis survival. Shown is 1 of 2 independent experiments with the same pattern. (B) Blood leukocyte counts at 36 hours after surgery. (C) Sera collected before or at 12 hours after surgery was measured for G-CSF by ELISA. (D) Bone marrow (BM) B-cell, preneutrophil, and mature neutrophil counts at 36 hours after surgery. Preneutrophils were identified as Lin−CD115−SiglecF−Gr-1+CD11b+CXCR4hic-kitintCXCR2− and mature neutrophils were identified as Lin−CD115−SiglecF−Gr-1+CD11b+CXCR4−c-kit−CXCR2+.66 (E) Representative flow cytometry plot of LSKs and CMPs identified by costaining c-kit and sca-1 in lineage-negative BM cells. (F) Absolute number of LSKs and CMPs in 2 femurs of WT and CD11c−/− mice at 24 hours after surgery. (G) Proliferation profile. At 20 hours after surgery, mice were pulsed with BrdU for an additional 4 hours, then analyzed for BrdU incorporation in the BM cells. (B-D,F-G) Symbols indicate individual mice. Data are representative of 2 experiments. Error bars indicate ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was tested with the log-rank test (A), Student t test (B,D,F-G), and 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post hoc analysis (C). *P < .05; **P < .01.

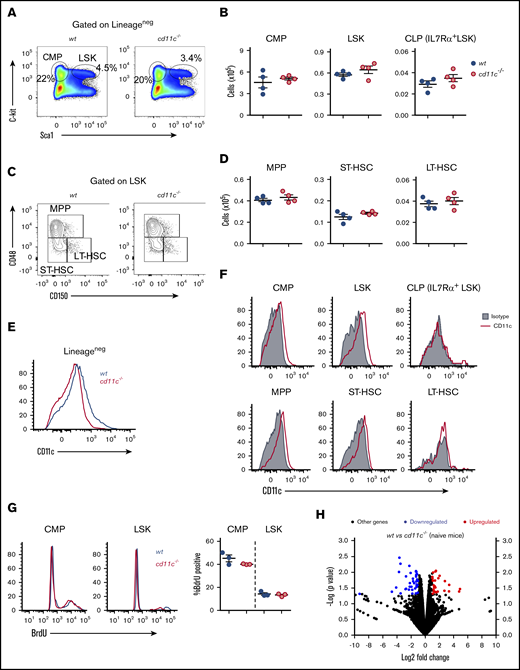

CD11c was expressed on HSPCs in mouse and human bone marrow

It was important to follow-up these results in sepsis to determine whether WT and CD11c−/− mice differed in hematopoiesis in the absence of an experimental insult. There was no difference between WT and CD11c−/− mice in the frequency and the number of LSK cells, CMP cells, or common lymphoid progenitor (CLP) cells among lineage-negative bone marrow cells between WT and CD11c−/− mice (Figure 2A-B). The LSK population was further divided into long-term hematopoietic stem cells (LT-HSCs), short-term HSCs (ST-HSCs), and multipotent progenitors (MPPs) using phenotypic markers (Figure 2C). Importantly, there was no difference in LT-HSC, ST-HSC, and MPP cell number (Figure 2D). We did not observe any CD11c expression on the surface of preneutrophils, immature neutrophils, mature neutrophils, pre-/pro-B cells, or immature B cells (data not shown). The expression of CD11c on lineage-negative bone marrow cells was confirmed by comparison between WT and CD11c−/− mice (Figure 2E). Among the Lineage− cell population in WT mice, CD11c was expressed on the cell surface of LSK cells and CMP cells, but not on CLP cells (Figure 2F). Furthermore, MPPs and ST-HSCs, not LT-HSCs showed CD11c expression (Figure 2F). To evaluate translational implication of our findings, we also examined CD11c expression on human bone marrow stem cells and peripheral blood stem cells. The human HSC population is seen in Lineage−CD34+CD38−CD90+CD45RA+ population. CD11c was expressed on this phenotypic HSC population in both bone marrow and peripheral blood (supplemental Figure 1A-B). There was no difference in the frequency of BrdU+ LSK cells between naive WT and CD11c−/− mice, indicating no difference in the proliferation between 2 strains at baseline (Figure 2G). BrdU+ LSK cells in CD11c−/− mice had relatively lower mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). Illumina sequencing of pooled RNA from sorted LSK cells showed that among 16 981 genes read from both genotypes, only 26 genes were upregulated and only 38 genes were downregulated in CD11c−/− LSK cells compared with WT LSK cells. Thus, gene expression profiles between WT and CD11c−/− LSK cells were remarkably similar (Figure 2H). The list of up- and downregulated genes is shown in supplemental Table 1. Overall, flow cytometry and gene-expression profiling showed only a slight difference in HSPCs between naive WT and CD11c−/− mice. Among naive mice deficient in the 3 other α-subunits of the β2 integrin subfamily, no significant differences in the frequency of BrdU+ CMP and LSK cells were found either (supplemental Figure 1C).

The expression of CD11c on HPSCs and its role. (A) Representative flow cytometry plot of LSKs and CMPs identified by costaining of c-kit and sca-1 in lineage-negative BM cells from naive WT and CD11c−/− mice. (B) Absolute numbers of LSKs, CMPs, and CLPs in 2 femurs of naive WT and CD11c−/− mice. (C) Representative flow cytometry plot profiling LT-HSC, ST-HSC, and MPP subpopulations in LSKs. (D) Absolute numbers of LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, and MPPs in 2 femurs of WT and CD11c−/− mice. (E) CD11c expression on lineage-negative BM cells confirmed by using CD11c−/− mice. Shown was the representative histogram overlay analysis. BM cells from 3 WT or CD11c−/− mice were pooled and used in each experiment; at least 5 independent experiments were done with the same pattern. (F) CD11c expression on LSKs, CMPs, CLPs, LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, and MPPs in WT mice. Representative histograms are shown. (G) BrdU incorporation assay. Left, Representative histogram overlay of BrdU staining. Right, Cumulative analysis of frequency of BrdU+ population in WT and CD11c−/− mice. (H) Volcano plot from RNA-sequencing analysis of LSK cells isolated from naive WT and CD11c−/− mice. Data were representative of 5 experiments (A-F) or 3 experiments (G-H) with the same pattern. Symbols indicate individual mice. Error bars indicate ± SEM. (B,D,G) Statistical significance was tested by the Student t test.

The expression of CD11c on HPSCs and its role. (A) Representative flow cytometry plot of LSKs and CMPs identified by costaining of c-kit and sca-1 in lineage-negative BM cells from naive WT and CD11c−/− mice. (B) Absolute numbers of LSKs, CMPs, and CLPs in 2 femurs of naive WT and CD11c−/− mice. (C) Representative flow cytometry plot profiling LT-HSC, ST-HSC, and MPP subpopulations in LSKs. (D) Absolute numbers of LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, and MPPs in 2 femurs of WT and CD11c−/− mice. (E) CD11c expression on lineage-negative BM cells confirmed by using CD11c−/− mice. Shown was the representative histogram overlay analysis. BM cells from 3 WT or CD11c−/− mice were pooled and used in each experiment; at least 5 independent experiments were done with the same pattern. (F) CD11c expression on LSKs, CMPs, CLPs, LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, and MPPs in WT mice. Representative histograms are shown. (G) BrdU incorporation assay. Left, Representative histogram overlay of BrdU staining. Right, Cumulative analysis of frequency of BrdU+ population in WT and CD11c−/− mice. (H) Volcano plot from RNA-sequencing analysis of LSK cells isolated from naive WT and CD11c−/− mice. Data were representative of 5 experiments (A-F) or 3 experiments (G-H) with the same pattern. Symbols indicate individual mice. Error bars indicate ± SEM. (B,D,G) Statistical significance was tested by the Student t test.

Systemic LPS injection induced loss of HSPCs in CD11c−/− mice

Previously, it was shown that HSCs acted as a direct pathogen stress sensor through Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4).44 LPS, a TLR4 ligand, is the cell wall component of gram-negative bacteria and contributes to sepsis pathophysiology. To mimic systemic infection, we examined the role of CD11c in a systemic LPS injection model. LPS IV injection caused a far greater decline of lineage negative cells in the bone marrow of CD11c−/− mice than in that of WT mice (Figure 3A). Furthermore, the number of WT LSK cells significantly increased at 6 and 14 hours after LPS injection, whereas the number of CD11c−/− LSK cells declined in the same time period (Figure 3B). In WT mice, the number of CMP cells significantly decreased over time from the baseline, likely due to emergent production of neutrophils (Figure 3B). Among LSK cells, ST-HSCs and MPPs were almost absent in CD11c−/− mice at 6 hours after LPS stimulation, whereas CD11c−/− LT-HSC was observed in the bone marrow (Figure 3B). Furthermore, the number of WT bone marrow neutrophils decreased, suggesting mobilization into the periphery. In contrast, the number of bone marrow CD11c−/− neutrophils showed no similar decrease (supplemental Figure 2A), consistent with dysregulation. In another contrast, the number of CD11c−/− CMP cells decreased much more than that of WT CMP cells. The immunofluorescence histology confirmed that c-kit+ population significantly increased in the bone marrow of WT mice following LPS injection (Figure 3C). In contrast, in CD11c−/− mice, LPS induced little increase in the c-kit+ population in the bone marrow, despite comparable amounts of c-kit+ populations at the naive stage of the 2 genotypes (Figure 3C), in line with our flow cytometry analysis (Figure 3A).

CD11c deficiency affects HPSC proliferation and survival in a systemic LPS injection model. (A) Representative flow cytometry plot showing lineage-negative BM cells at different time points post-LPS injection (10 mg/kg IV). (B) Dynamics of LSK and CMP numbers of WT and CD11c−/− mice after LPS injection. Data are shown as mean ± SEM of 3 to 6 mice per group per time point. Representative flow cytometry plots of LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, and MPPs are shown. (C) Immunofluorescence staining of progenitor cells in BM. Femurs from WT mice and CD11c−/− mice (both naive and 4 hours post-LPS) were stained with c-kit (green), DAPI (blue), and laminin (pink). Shown are representative images (full scale bar, 5 mm [in 1 mm increments]). (D-E) Proliferation and apoptosis measurement by Ki67 and active caspase 3 staining. Both WT and CD11c−/− mice were euthanized at 3 hours after LPS injection. (D) Representative flow cytometry plots of LSK cells. (E) Frequency (top panel) and absolute number (bottom panel) of Ki67+, active caspase 3–positive, and Ki67+/active caspase 3–positive in LSKs. (F) Z-VAD-fmk treatment. CD11c−/− mice received either vehicle (5% dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO] in saline, IP) treatment or Z-VAD (10 mg/kg, dissolved in 5% DMSO in saline, IP) treatment at 1 hour before and 2 hours after LPS injection, and then were euthanized at 6 hours after LPS injection. Total BM cells, lineage-negative cells, LSKs, and CMPs were counted. (G) Volcano plot from RNA-sequencing analysis of LSK cells isolated from WT and CD11c−/− mice at 4 hours after LPS injection. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments with the same pattern. Error bars indicate ± SEM. Statistical significance was examined by 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc analysis (B), with the Student t test (E), and with 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc analysis (F). *P < .05; ***P < .001.

CD11c deficiency affects HPSC proliferation and survival in a systemic LPS injection model. (A) Representative flow cytometry plot showing lineage-negative BM cells at different time points post-LPS injection (10 mg/kg IV). (B) Dynamics of LSK and CMP numbers of WT and CD11c−/− mice after LPS injection. Data are shown as mean ± SEM of 3 to 6 mice per group per time point. Representative flow cytometry plots of LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, and MPPs are shown. (C) Immunofluorescence staining of progenitor cells in BM. Femurs from WT mice and CD11c−/− mice (both naive and 4 hours post-LPS) were stained with c-kit (green), DAPI (blue), and laminin (pink). Shown are representative images (full scale bar, 5 mm [in 1 mm increments]). (D-E) Proliferation and apoptosis measurement by Ki67 and active caspase 3 staining. Both WT and CD11c−/− mice were euthanized at 3 hours after LPS injection. (D) Representative flow cytometry plots of LSK cells. (E) Frequency (top panel) and absolute number (bottom panel) of Ki67+, active caspase 3–positive, and Ki67+/active caspase 3–positive in LSKs. (F) Z-VAD-fmk treatment. CD11c−/− mice received either vehicle (5% dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO] in saline, IP) treatment or Z-VAD (10 mg/kg, dissolved in 5% DMSO in saline, IP) treatment at 1 hour before and 2 hours after LPS injection, and then were euthanized at 6 hours after LPS injection. Total BM cells, lineage-negative cells, LSKs, and CMPs were counted. (G) Volcano plot from RNA-sequencing analysis of LSK cells isolated from WT and CD11c−/− mice at 4 hours after LPS injection. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments with the same pattern. Error bars indicate ± SEM. Statistical significance was examined by 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc analysis (B), with the Student t test (E), and with 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc analysis (F). *P < .05; ***P < .001.

To understand the mechanism of HPSC loss in CD11c−/− mice in the systemic LPS injection model, we examined the degree of proliferation and cell death. At 3 hours after LPS injection, a significantly higher number of apoptotic LSK cells were seen in CD11c−/− mice probed by active caspase 3 staining (Figure 3D-E). At this time point, there was also a significant increase in the number of proliferating LSK cells indicated by higher percentage of Ki67high LSK cells. The comparison of highly proliferating LSK cells between WT and CD11c−/− mice showed that apoptosis was more significant in highly proliferating CD11c−/− LSK cells (Figure 3E). In contrast, the proliferation and apoptosis of CD11c−/− CMP cells were not significantly different from those of WT CMP cells (supplemental Figure 2B). At 6 and 14 hours after LPS injection, the degree of proliferation was less in CD11c−/− LSK cells than in WT LSK cells (supplemental Figure 2C), consistent with the result from experimental polymicrobial sepsis model (Figure 1G). Because BrdU labeling reflects the accumulation of proliferated cells, whereas Ki-67 staining reflects the real-time status of cell proliferation, we concluded that both the increased Ki-67 and decreased BrdU incorporation in CD11c−/− LSK cells pointed to the loss of proliferating LSK cells in CD11c−/− mice upon LPS stimulation.

To test the hypothesis that apoptosis was responsible for the significant loss of LSK cells in CD11c−/− mice upon LPS stimulation, CD11c−/− mice were subjected to LPS injection in the presence of pan caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-fmk. Z-VAD-fmk significantly attenuated the loss of LSK cells after LPS injection in CD11c−/− mice (Figure 3F), supporting our hypothesis. However, the number of LSK cells in CD11c−/− mice treated with Z-VAD was less than that in WT mice receiving vehicle, indicating that other mechanisms may be involved. To examine any transcriptomic difference, we performed RNA sequencing analysis of LSK cells from mice subjected to LPS injection. Among 17 568 genes that were read, 37 genes were upregulated and 165 genes were downregulated in CD11c−/− LSK cells (Figure 3G). Upregulated genes included Eph receptor,45 heat shock protein 1,46 indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 147 and IL-33,48 which are involved in proliferation and/or apoptosis. Downregulated genes included a group of cell cycle related genes such as cyclin A2 and E2F transcription factor 4 (E2f4). The list of up- and downregulated genes is shown in supplemental Table 1.

We also tested the response to systemic LPS injection in mice with other β2 integrin α subunit knockout. The number of CD11a−/−, CD11b−/− and CD11d−/− LSK cells significantly increased as WT LSK cells did (supplemental Figure 2D). The number of CD11a−/−, CD11b−/−, and CD11d−/− CMP cells significantly decreased as that of WT LSK cells did. This suggested that loss of HSPCs in the systemic LPS infection model was unique to CD11c−/− mice. ICAM-1 serves as a ligand for all the β2 integrin members. The number of ICAM-1−/− LSK cells significantly increased as WT cells did (data not shown), indicating that ICAM-1 was unlikely to be a ligand for CD11c in this process.

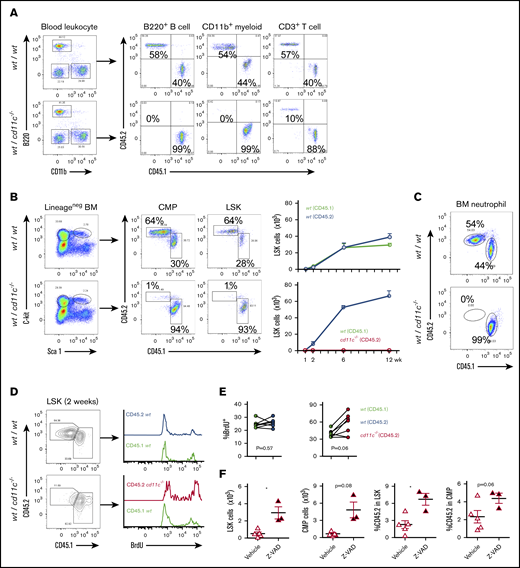

Bone marrow mixed chimeric mice experiment demonstrated that CD11c intrinsically impacted HSPC function

To further verify the role of CD11c in HSPCs and confirm that this role was intrinsic to the hematopoietic system, we generated mixed bone marrow chimeric mice to harbor both WT and CD11c−/− mice-derived hematopoietic systems, which were distinguished by congenic markers CD45.1 and CD45.2, respectively. Control mixed chimeras were made by reconstitution of CD45.1 and CD45.2 WT bone marrow cells. At 6 and 12 weeks after transplantation, peripheral blood was examined. In control chimera, peripheral blood myeloid cells, B cells, and T cells originated equally from WT CD45.1 and WT CD45.2 donors. In contrast, in WT and CD11c−/− bone marrow chimeras, peripheral blood B cells and myeloid cells derived from the CD11c−/− donor were almost absent, and T cells were diminished compared with those from WT donor (Figure 4A; supplemental Figure 3A). To understand the underlying cause of this phenotype, we examined the bone marrow of these chimeric mice. Consistent with the peripheral leukocyte analysis, CD11c−/− donor-derived LSK cells were almost absent from the bone marrow of the mixed WT/ CD11c−/− chimera as early as 2 weeks after transplantation (Figure 4B; supplemental Figure 3B-C). Compatible with the peripheral blood result, neutrophils in bone marrow in the WT/CD11c chimeric mice were predominantly WT as early as 2 weeks after bone marrow transplantation (Figure 4C; supplemental Figure 3D). In contrast, the bone marrow neutrophils of control chimera were derived from both CD45.1 and CD45.2 backgrounds (Figure 4C; supplemental Figure 3D). The bone marrow of chimeric mice at 1 week after transplantation showed equal numbers of WT and CD11c−/− derived LSK cells in the bone marrow (supplemental Figure 3B-C). CD11c−/− LT-HSC, ST-HSC and MPP were observed in the bone marrow at 1 week after transplantation (supplemental Figure 3C), suggesting that all the HSPC components from CD11c−/− bone marrow cells adequately homed to the bone marrow. A significant loss of CD11c−/− derived LSK cells subsequently occurred between 1 and 2 weeks after bone marrow transplantation.

CD11c deficiency affects repopulation of HSPCs. (A-F) Mixed chimeric mouse study. Chimeric mice were made by transplanting the mixture of CD45.1 WT and CD45.2 WT BM cells or CD45.1 WT and CD45.2 CD11c−/− BM cells at the ratio of 1:1 into lethally irradiated recipient mice. (A) At 10 weeks post-BM transplantation, peripheral blood from recipient mice was collected and subjected to flow cytometry analysis. Shown are representatives of 5 mice in both groups. (B-C) At 12 weeks, BM cells from recipient mice were collected and subjected to flow cytometry analysis. (B) Left panel, Representative flow cytometry plots of lineage-negative cells, LSKs, and CMPs from different originations differentiated by congenic markers. Right panel, Cumulative absolute number of LSKs at various time points post-BM transplantation. (C) Representative flow cytometry plots of BM neutrophils from different originations differentiated by congenic markers at 12 weeks post-BM transplantation. Shown are representatives of 5 mice in both groups. (D-E) Proliferation measured by in vivo BrdU labeling. At 2 weeks post-BM transplantation, BrdU pulse injection was performed to examine the proliferation. (D) Representative flow cytometry plots. (E) The frequency of BrdU+ in LSKs in WT/WT chimera or in WT/ CD11c−/− chimera. Line indicates an individual chimeric mouse. (F) Z-VAD-fmk treatment of WT/ CD11c−/− chimera. Starting at 1 week after BM transplantation, chimeric mice were treated with either vehicle (5% DMSO in saline, IP) or Z-VAD (10 mg/kg, dissolved in 5% DMSO in saline, IP) daily for 4 days. Then, the mice were euthanized and BM LSKs and CMPs were counted and analyzed by flow cytometry. (Left 2 panels) Cell number. (Right panel) Ratio of CD11c−/− derived CD45.2 positive cells in LSK or CMP. (A-C) Representatives of 3 to 5 independent experiments with the same pattern. (D-F) Representatives of 2 independent experiments with the same pattern. Symbols indicate individual mice. Statistical significance was examined by the Student t test (E-F). *P < .05.

CD11c deficiency affects repopulation of HSPCs. (A-F) Mixed chimeric mouse study. Chimeric mice were made by transplanting the mixture of CD45.1 WT and CD45.2 WT BM cells or CD45.1 WT and CD45.2 CD11c−/− BM cells at the ratio of 1:1 into lethally irradiated recipient mice. (A) At 10 weeks post-BM transplantation, peripheral blood from recipient mice was collected and subjected to flow cytometry analysis. Shown are representatives of 5 mice in both groups. (B-C) At 12 weeks, BM cells from recipient mice were collected and subjected to flow cytometry analysis. (B) Left panel, Representative flow cytometry plots of lineage-negative cells, LSKs, and CMPs from different originations differentiated by congenic markers. Right panel, Cumulative absolute number of LSKs at various time points post-BM transplantation. (C) Representative flow cytometry plots of BM neutrophils from different originations differentiated by congenic markers at 12 weeks post-BM transplantation. Shown are representatives of 5 mice in both groups. (D-E) Proliferation measured by in vivo BrdU labeling. At 2 weeks post-BM transplantation, BrdU pulse injection was performed to examine the proliferation. (D) Representative flow cytometry plots. (E) The frequency of BrdU+ in LSKs in WT/WT chimera or in WT/ CD11c−/− chimera. Line indicates an individual chimeric mouse. (F) Z-VAD-fmk treatment of WT/ CD11c−/− chimera. Starting at 1 week after BM transplantation, chimeric mice were treated with either vehicle (5% DMSO in saline, IP) or Z-VAD (10 mg/kg, dissolved in 5% DMSO in saline, IP) daily for 4 days. Then, the mice were euthanized and BM LSKs and CMPs were counted and analyzed by flow cytometry. (Left 2 panels) Cell number. (Right panel) Ratio of CD11c−/− derived CD45.2 positive cells in LSK or CMP. (A-C) Representatives of 3 to 5 independent experiments with the same pattern. (D-F) Representatives of 2 independent experiments with the same pattern. Symbols indicate individual mice. Statistical significance was examined by the Student t test (E-F). *P < .05.

BrdU incorporation assay suggested that LSK cells originated from CD11c−/− mice possessed significantly enhanced proliferation compared with their counterparts on WT background (Figure 4D-E). No difference in proliferation was seen in CMP cells (data not shown). Although myeloid cells and B cells undergo differentiation and maturation in the bone marrow, T cells undergo maturation in the thymus following the migration of their progenitor cells from the bone marrow. As expected, few double-negative, single-positive, and double-positive T cells on CD11c−/− background were observed in WT/CD11c−/− mixed chimeric mice compared with their counterparts on WT background (supplemental Figure 3E). To examine the contribution of apoptosis in the loss of CD11c−/− derived HSPC repopulation in the bone marrow, mixed chimeric mice (WT / CD11c−/−) were assigned to either vehicle or Z-VAD-fmk treatment of 4 consecutive days starting at 1 week after the transplantation, when HSPCs from both cells were expected to exist similarly in the bone marrow. We found that Z-VAD-fmk treated group had significantly higher number of LSK cells on CD11c−/− background in the bone marrow, indicating that apoptosis was at least in part responsible for the loss of CD11c−/− derived LSK cells (Figure 4F), consistent with our result in LPS model (Figure 3E). Because the majority of CD11c−/− LSK cells was absent by week 2 after bone marrow transplantation, we focused to examine the contribution of apoptosis in HSPC number using Z-VAD-fmk at this time frame. In the future, a much longer duration of Z-VAD-fmk administration can be considered to examine the role of CD11c at later time points after bone marrow transplantation.

Discussion

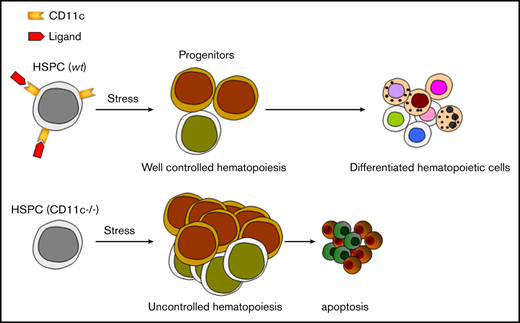

Overall, our study showed for the first time that β2 integrin CD11 c/CD18 was critical for HSPC function under stress. Adhesive interactions are important in the regulation of hematopoiesis.49 The role of other integrins in HSPCs has been described. Integrins containing α4, α6, and β7 subunits regulate HSPC homing.50-52 Integrin αvβ3 plays a role in maintaining the quiescence of HSPCs.53 CD11a has been shown to be important for lymphocyte progenitor development, but not for HSPCs.54 Our finding is that CD11c/CD18 has a distinct role compared with other β2 integrins, but also relative to other integrins. During sepsis, stress granulopoiesis is activated to increase myeloid cell production. This involves a robust proliferation of HSPCs.42 This physiological response of the hematopoietic system to various infections is governed by a direct stimulation of progenitor cells through the activation of TLRs,55 growth factors and cytokines (including G-CSF)56 produced by the bone marrow niche-forming cells and mature hematopoietic cells and paracrine effects of TLR-activated HSPCs.57 The contribution of bone marrow failure to morbidity and mortality in sepsis has been not fully studied owing to the difficulty of collecting samples, but the lower number of differentiated cells in the bone marrow was associated with worse outcome in 1 study.58 Although the number of HSPCs can be affected by many factors in the sepsis model, we showed that the deficiency of CD11c on HSPCs resulted in loss of HSPCs in sepsis. CD11c was expressed on ST-HSC and MPP, not on LT-HSC. In line with this finding, we found that the ST-HSC and MPP population was absent in CD11c−/− mice stimulated by LPS, whereas LT-HSC population was spared. This was associated with exaggerated proliferation and subsequent apoptosis of HPSCs. This lead to less available CMP in CD11c−/− mice following LPS stimulation. In mixed chimera study, CD11c−/− HPSCs also showed exaggerated proliferation and apoptosis in bone marrow, though they were homed normally, indicating that CD11c was highly involved in homeostasis of HPSCs under stress. We do not know whether CD11c function is impaired in severe septic patients. Future study to delineate the function of CD11c in patients with severe sepsis would potentially open an avenue to control and facilitate HSPC proliferation in a timely manner to boost the immune system in sepsis.

There are, however, limitations to our study. CD11c binds to a diverse array of ligands in vitro. We have not identified a paired ligand for CD11c in vivo in this study. ICAM-1 is 1 of known CD11c ligands, but our study did not support that ICAM-1 would be involved in CD11c-mediated HSPC modulation. CD11c is a complement receptor classified as complement receptor 4 and binds to iC3b in vitro.59 C3 and C5 are involved in HSPC mobilization and homing.60-62 C3 cleaved fragments (C3a, desArgC3a, iC3b) increase in the bone marrow during mobilization.63 Fibrinogen and LPS are also reported as CD11c ligands in vitro, where fibrinogen has been shown to trigger proliferation of B cells via CD11c.64,65 Identifying CD11c ligand remains to be done in the future. The role of CD11b in neutrophil apoptosis has been previously described.10 The type of ligands that activate CD11b can affect neutrophil apoptosis quite differently. Thus, identification of a ligand for CD11c on HSPCs will also help to elucidate the underlying mechanism of apoptosis induction in CD11c−/− LSK cells.

CD11c is frequently used as a marker of DCs, which are of great importance in sensing danger in the immune system. Whether the role of CD11c is solely on stem cells or on stem cell–derived cells in other tissues such as bone marrow–derived DCs, will require further work including the use of conditional CD11c knockout mice.

Requests for data may be e-mailed to the corresponding author, Koichi Yuki, at koichi.yuki@childrens.harvard.edu.

Acknowledgments

This work was in part supported by the Children's Hospital Medical Center Anesthesia Foundation (K.Y.) and National Institutes of Health grants R01GM118277 (K.Y.) and R01GM127600 (K.Y.) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and grant R21 HD099194 (K.Y.) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Authorship

Contribution: L.H., R.A.V., and K.Y. designed and performed experiments and wrote the manuscript; and V.G.S. and T.A.S. designed experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Koichi Yuki, Cardiac Anesthesia Division, Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, 300 Longwood Ave, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail: koichi.yuki@childrens.harvard.edu.

References

Author notes

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![CD11c deficiency affects HPSC proliferation and survival in a systemic LPS injection model. (A) Representative flow cytometry plot showing lineage-negative BM cells at different time points post-LPS injection (10 mg/kg IV). (B) Dynamics of LSK and CMP numbers of WT and CD11c−/− mice after LPS injection. Data are shown as mean ± SEM of 3 to 6 mice per group per time point. Representative flow cytometry plots of LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, and MPPs are shown. (C) Immunofluorescence staining of progenitor cells in BM. Femurs from WT mice and CD11c−/− mice (both naive and 4 hours post-LPS) were stained with c-kit (green), DAPI (blue), and laminin (pink). Shown are representative images (full scale bar, 5 mm [in 1 mm increments]). (D-E) Proliferation and apoptosis measurement by Ki67 and active caspase 3 staining. Both WT and CD11c−/− mice were euthanized at 3 hours after LPS injection. (D) Representative flow cytometry plots of LSK cells. (E) Frequency (top panel) and absolute number (bottom panel) of Ki67+, active caspase 3–positive, and Ki67+/active caspase 3–positive in LSKs. (F) Z-VAD-fmk treatment. CD11c−/− mice received either vehicle (5% dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO] in saline, IP) treatment or Z-VAD (10 mg/kg, dissolved in 5% DMSO in saline, IP) treatment at 1 hour before and 2 hours after LPS injection, and then were euthanized at 6 hours after LPS injection. Total BM cells, lineage-negative cells, LSKs, and CMPs were counted. (G) Volcano plot from RNA-sequencing analysis of LSK cells isolated from WT and CD11c−/− mice at 4 hours after LPS injection. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments with the same pattern. Error bars indicate ± SEM. Statistical significance was examined by 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc analysis (B), with the Student t test (E), and with 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc analysis (F). *P < .05; ***P < .001.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/4/24/10.1182_bloodadvances.2020002504/1/m_advancesadv2020002504f3.png?Expires=1767708664&Signature=ruoox4sadKkNzL0CDZP~KYC~BQCqZiyqRc6EDxm0Mxagsg3Z1hide-Ud8aqFwlDw9rdQSEZiWycxOyE0CE4A-hfg~pAQle7Xb6pKZpWVti7Ughb3N3gRemeZMOQw9-XJ8JcvPFxA2TjHKfE8WoeUW3jNFaHfsKkUUq-zk9idRsa5Dam95tWZhE4xH-HoUCOwwyTJgAqwbuhNrrvmh4kOL4xit4gw6K618WUQIl3fXXVc7mrZuOm-x6Km4EW0T2S1~j4DcLfkYzopckjUjPx9oLv8P4wwX9rDU~T3NrZdtNbXvmSqbHh7d~-edWzNYc~ipIxNDpSUbvt-1HDdv3cF~Q__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)