Key Points

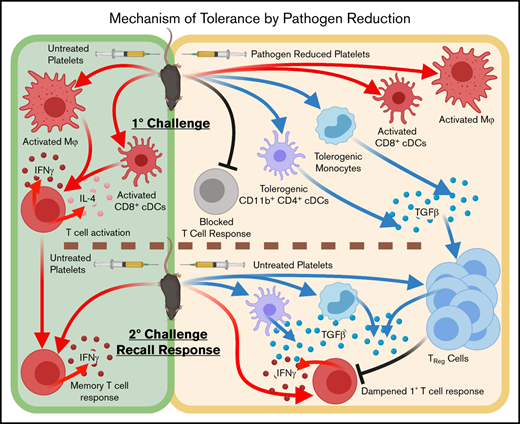

Pathogen-reduced platelets induce tolerogenic CD11b+ CD4+ dendritic cells and monocytes and induce Treg-cell responses to subsequent exposure.

Pathogen-reduced platelets do not induce T-cell activation, and T-cell responses to subsequent untreated transfusions are diminished.

Abstract

Alloimmunization against platelet-rich plasma (PRP) transfusions can lead to complications such as platelet refractoriness or rejection of subsequent transfusions and transplants. In mice, pathogen reduction treatment of PRP with UVB light and riboflavin (UV+R) prevents alloimmunization and appears to induce partial antigen-specific tolerance to subsequent transfusions. Herein, the in vivo responses of antigen-presenting cells and T cells to transfusion with UV+R-treated allogeneic PRP were evaluated to understand the cellular immune responses leading to antigen-specific tolerance. Mice that received UV+R-treated PRP had significantly increased transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) expression by CD11b+ CD4+ CD11cHi conventional dendritic cells (cDCs) and CD11bHi monocytes (P < .05). While robust T-cell responses to transfusions with untreated allogeneic PRP were observed (P < .05), these were blocked by UV+R treatment. Mice given UV+R-treated PRP followed by untreated PRP showed an early significant (P < .01) enrichment in regulatory T (Treg) cells and associated TGF-β production as well as diminished effector T-cell responses. Adoptive transfer of T-cell–enriched splenocytes from mice given UV+R-treated PRP into naive recipients led to a small but significant reduction of CD8+ T-cell responses to subsequent allogeneic transfusion. These data demonstrate that pathogen reduction with UV+R induces a tolerogenic profile by way of CD11b+ CD4+ cDCs, monocytes, and induction of Treg cells, blocking T-cell activation and reducing secondary T-cell responses to untreated platelets in vivo.

Introduction

Alloimmunization derived from platelet-rich plasma (PRP) transfusions can interfere with subsequent transfusions by causing platelet refractoriness or transplant rejection.1-6 Although the risk of alloimmunization has been profoundly reduced with the wide adoption of leukoreduction practices,7-13 recent estimates of alloantibody generation in platelet recipients range from ∼4% to 18%, with most responses targeting major histocompatibility complex (MHC) antigens.14-17 Pathogen reduction technology (PRT) treatment with UVB light and riboflavin (UV+R) reduces not only the risk of transfusion-transmission of infectious agents but also alloantibody responses18-20 and confers a partial antigen-specific immune tolerance to subsequent exposures of untreated allogeneic PRP in mice.18 In vitro, UV+R induces rapid cell death of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and downregulation of surface adhesion molecules, which blocks allogeneic T-cell responses in mixed lymphocyte reactions.21 Furthermore, UV+R-treated PRP induces a quasi-apoptotic state in human and mouse leukocytes that may lead to processing of these cells in a tolerogenic manner.22

Both platelets and contaminating leukocytes contribute to the alloantibody responses in platelet transfusion.23,24 Alloantibody responses result from complex interactions of innate and adaptive cellular responses that involve antigen-presenting cells (APCs) such as macrophages (Mϕs), conventional dendritic cells (cDCs), and B cells, and their cognate T cells.23,25,26 While advances have been made in understanding the cellular immune response to red blood cell (RBC) transfusions, less is known about the mechanisms regulating cellular responses against allogeneic platelets.27-30 Platelets can incite inflammatory responses due to factors such as platelet storage lesion, platelet-specific surface receptors, and platelet-expressed products,31-36 leading to adverse transfusion reactions, including allergic reactions, febrile nonhemolytic reactions, sepsis, and transfusion-associated acute lung injury.31,37 Conversely, platelets can induce tolerance by transfusion-related immunomodulation in some contexts.33,38 Autologous or syngeneic platelets, via CD154 or other factors, can modulate immune responses by directly interacting with APCs, leading to augmented cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) or humoral responses in mice.31,39-42 Similarly, platelets and platelet-secreted products can directly affect human APCs in vitro.34,35,42-50 While studies have identified roles for APCs or T cells in the immune response to allogeneic platelets,34,50-54 a comprehensive understanding of how the recipient immune system responds to allogeneic platelet transfusions in vivo is lacking. Furthermore, while the effect of PRT or UV light on blood components has been evaluated in vitro,21,55-60 in vivo studies have focused predominantly on alloantibody outcomes, with little known about cellular responses.18,21,22,61 Immune tolerance, including induction of T regulatory cells (Treg cells), has been associated with other UV treatment strategies in humans and animal models,62-68 suggesting similar mechanisms may be induced by PRT.

The immune response can be inflammatory or immunoregulatory depending on immune context, much of which is established early by APCs that bridge the innate and adaptive responses. Alternatively, adaptive immune responses can be regulated by peripheral tolerance mechanisms mediated primarily by CD4+ Treg cells.69 We evaluated the mechanisms behind partial tolerance induced by UV+R through examination of innate and adaptive cellular immune responses in vivo to allogeneic PRP transfusions.

Materials and methods

Mice

Male and female BALB/cJ (BALB/c) mice aged 7 to 23 weeks and female C57Bl/6J (B6) mice aged 7 to 12 weeks (The Jackson Laboratory) were maintained in a specific-pathogen–free vivarium at Vitalant Research Institute (San Francisco, CA) in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals under the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. Research was approved with oversight of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Covance Laboratories (San Carlos, CA) under Animal Welfare Assurance A3367-01.

PRP preparation and UV+R

PRP preparation and UV+R treatment were performed as previously described.12,18,19,21,22,61 Briefly, PRP and white blood cells (WBCs) were isolated by gentle centrifugation and Ficoll separation, with WBCs added back to the PRP, yielding a mean of 4.36 × 106 WBCs/mL and 2.06 × 108 platelets/mL. This nonleukoreduced PRP, modeling a worst-case allogeneic transfusion, was used, as WBCs are necessary for partial immune tolerance induction by UV+R (supplemental Figure 1), and T-cell responses were undetectable with leukoreduced PRP (supplemental Figure 2). Pathogen-reduced products were treated with UV+R (Mirasol Pathogen Reduction Technology System, Terumo Blood and Cell Technologies) at a scaled dose. Transfusions consisted of 100 μL PRP given by lateral tail vein IV injection administered within 4 hours of collection.

Flow cytometry

Blood was collected by orbital enucleation under inhalation anesthesia into 14% citrate phosphate dextrose adenine-1. Spleens were homogenized between glass slides for analysis of lymphocytes. For analysis of APCs, spleens were digested in enzymatic solution with 2 mg/mL Collagenase D (Roche) in buffer for 30 minutes at 37°C. Following RBC lysis, samples were incubated in FcR block (BD), labeled with a BioLegend Zombie Aqua Fixable Viability Kit, and stained. Intracellular cytokine staining was performed with a BD Cytofix/Cytoperm Fixation/Permeabilization Kit after 3-hour stimulation in BD Leukocyte Activation Cocktail with BD GolgiPlug. Intracellular staining of Forkhead box P3 (FoxP3), CTL-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) was performed with an eBioscience FoxP3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer set. Anti-mouse antibodies that were used for this study are listed in supplemental Table 1. Absolute counts of cell populations were made with CountBright Absolute Counting Beads (Invitrogen). Samples were run on a BD FACS LSR II with BD FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences). Cytometry data were analyzed on FlowJo software version 10, selecting for live single events.

Adoptive transfer

Recipient spleens were collected 14 to 16 days after transfusion, homogenized between glass slides under sterile conditions, pooled, treated with RBC lysis solution, and depleted of B cells and plasma cells with purified B220 (RA3-6B2) and CD138 (281-2) antibodies from BioLegend and anti-rat immunoglobulin G magnetic beads (Dynabeads or BioMag) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were >89% depleted of B cells and >83.7% viable, and 17 to 20 × 106 were transferred IV into naive recipients. Mice were transfused 24 hours after adoptive transfer, and spleens were harvested 2, 4, 7, or 14 days after final transfusion for analysis of T-cell responses.

Statistical analysis

Analysis was performed using Prism version 7 (GraphPad Software). Two-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons posttest were used to compare each group to every other group, with significant differences reported. Heat maps show fold changes of groups when compared with the nontransfusion group. For visual clarity, heat maps and line graphs only show significance compared with the nontransfusion group unless otherwise noted. The remaining significant differences between groups are listed in supplemental Tables 2-8, along with total population frequency or number means, median fluorescence intensity (MFI), and standard deviation. Some time points with no differences were not further analyzed in subsequent experiments, and where <2 independent data sets were available, the data were excluded (as indicated with an “X”).

Results

APC responses

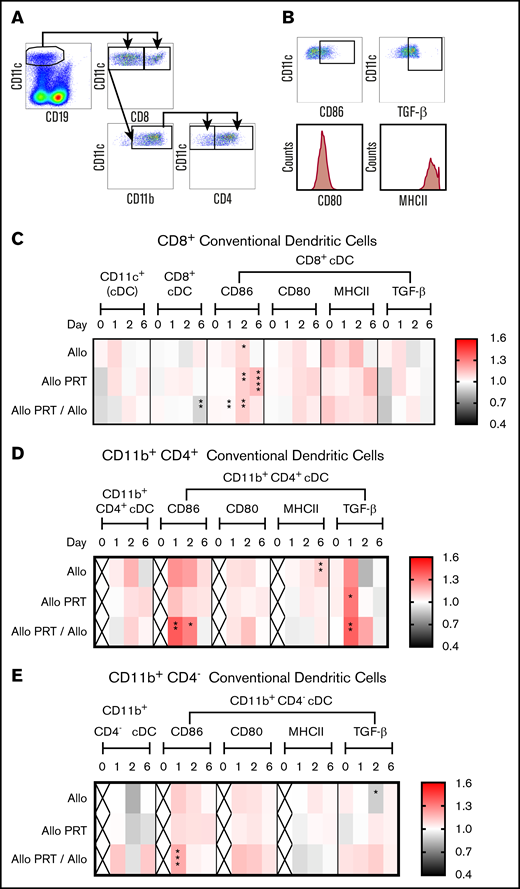

APCs, defined by class II MHC (MHCII) expression, take up antigens and, upon activation, upregulate surface costimulatory receptors (eg, CD86 or CD80) or regulatory elements such as TGF-β.70-72 Dendritic cells include various subsets with specific effector functions. CD8+ cDCs specialize in cross-presentation to CD8+ T cells.71-74 CD4+ CD11b+ cDCs primarily present to CD4+ T cells on MHCII (but can also cross-present to CD8+ T cells) and are potent producers of cytokines for CD4+ T-cell activation and regulation.73,74 CD4− CD11b+ cDCs, also called monocyte-derived DCs, are highly inflammatory,71 and plasmacytoid dendritic cells have both inflammatory and immunoregulatory capacity.71 To evaluate APC responses to both untreated and UV+R-treated PRP, B6 recipients were given no transfusion, a single untreated allogeneic BALB/c PRP transfusion (Allo), a single UV+R-treated allogeneic BALB/c PRP transfusion (Allo PRT), or an UV+R-treated allogeneic BALB/c PRP transfusion followed by an untreated allogeneic BALB/c PRP transfusion 2 weeks later (Allo PRT/Allo). APC populations from the spleen were evaluated at 4 hours or 1, 2, or 6 days after the final transfusion.

No differences were seen among total or subset cDC frequencies, except for a reduced frequency of CD8+ cDCs on day 6 for Allo PRT/Allo (Figure 1C). The cDC responses were similar for the most part between groups, with the exception that UV+R-treated groups appeared tolerogenic with increased TGF-β expression. Specifically, CD86+ CD8+ cDCs increased on day 2 in the Allo group, on days 2 and 6 in the Allo PRT group, and on days 1 and 2 in the Allo PRT/Allo group (Figure 1C). For CD11b+ CD4+ cDCs, CD86 expression increased on days 1 and 2 in the Allo PRT/Allo group, MHCII expression increased on day 6 in the Allo group, and TGF-β expression increased on day 1 in the Allo PRT and Allo PRT/Allo groups (Figure 1D). A similar trend in TGF-β+ expression in the Allo group was seen at day 1 (P = .053). CD86+ CD11b+ CD4− cDCs increased on day 1 in the Allo PRT/Allo group, and TGF-β expression was reduced on day 2 in the Allo group (Figure 1E).

PRT-treated platelets induce TGF-β production in CD4+cDCs. The responses of cDCs were examined at 4 hours (day 0) and at days 1, 2, and 6. (A) Cells were gated on CD11cHi CD8+, CD11cHi CD8− CD11b+ CD4+ or CD11cHi CD8− CD11b+ CD4− cDC subsets. (B) The frequencies of CD86+ and TGF-β+ cells and the median fluorescent intensities of CD80 and MHCII were evaluated for each cDC subset. (C-E) Heat maps show fold changes of each group compared with the nontransfused group. The frequency of total cDCs was derived from total live-cell events, and the frequency of CD11cHi CD8+ (C), CD11cHi CD8− CD11b+ CD4+ (D), and CD11cHi CD8− CD11b+ CD4− (E) were derived from total cDCs. The frequencies of CD86+ and TGF-β+ were derived from their respective cDC subset. “X” labels time points where <2 sets of data were available. Data combined from 2 or 3 independent experiments (n = 5 per group) are shown. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001.

PRT-treated platelets induce TGF-β production in CD4+cDCs. The responses of cDCs were examined at 4 hours (day 0) and at days 1, 2, and 6. (A) Cells were gated on CD11cHi CD8+, CD11cHi CD8− CD11b+ CD4+ or CD11cHi CD8− CD11b+ CD4− cDC subsets. (B) The frequencies of CD86+ and TGF-β+ cells and the median fluorescent intensities of CD80 and MHCII were evaluated for each cDC subset. (C-E) Heat maps show fold changes of each group compared with the nontransfused group. The frequency of total cDCs was derived from total live-cell events, and the frequency of CD11cHi CD8+ (C), CD11cHi CD8− CD11b+ CD4+ (D), and CD11cHi CD8− CD11b+ CD4− (E) were derived from total cDCs. The frequencies of CD86+ and TGF-β+ were derived from their respective cDC subset. “X” labels time points where <2 sets of data were available. Data combined from 2 or 3 independent experiments (n = 5 per group) are shown. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001.

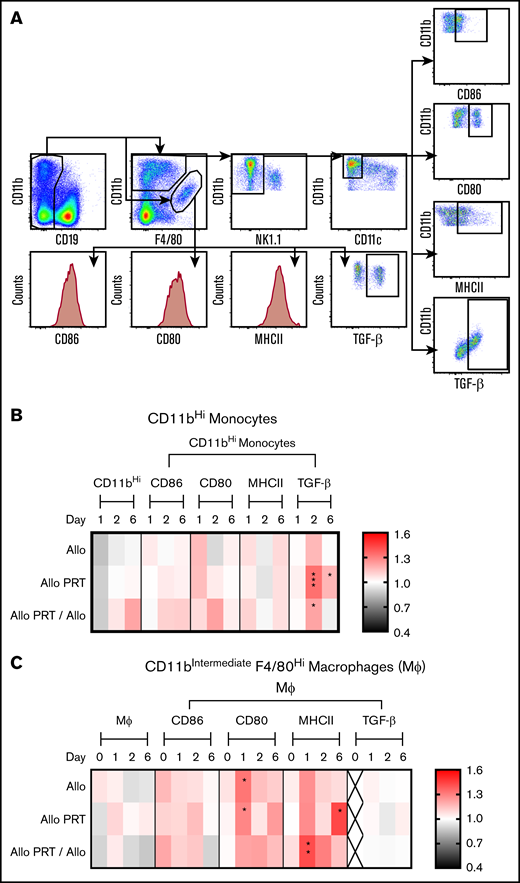

CD11bHi monocytes, but not mature macrophages, displayed evidence of tolerance in UV+R-treated groups, showing an increase in TGF-β expression on days 2 and 6 in the Allo PRT group and on day 2 in the Allo PRT/Allo groups (Figure 2B). For CD11bIntermediate F4/80Hi macrophages, CD80 expression was increased on day 1 for Allo and Allo PRT, and MHCII expression was increased on day 6 for Allo PRT and on day 1 for Allo PRT/Allo (Figure 2C). B cells (supplemental Figure 3) and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (supplemental Figure 4) displayed limited responses and no indication of increased TGF-β expression.

PRT-treated platelets induce TGF-β production in splenic monocytes. The responses of monocytes and Mϕ were examined at 4 hours (day 0) and at days 1, 2, and 6. (A) Cells were gated for monocytes by selecting for CD19- CD11bHi F4/80low(and)intermediate NK1.1− and CD11c− events or gated for macrophages by selecting for CD19− CD11bintermediate/F4/80Hi events. (B) Frequency of CD86+, CD80+, MHCII+, and TGF-β+ events were determined for monocytes with fold change compared with nontransfused group plotted. (C) For macrophages, measurements of median fluorescent intensities for CD86, CD80, and MHCII and frequency of TGF-β+ events were made, with fold change compared with nontransfused group plotted. The frequency of total monocytes and macrophages were derived from total live events and the frequencies of CD86+, CD80+, MHCII+, and TGF-β+ events were derived from total monocytes or macrophages, respectively. “X” labels time points where <2 sets of data are available. Data are combined from 2 or 3 independent experiments (n = 5 per group). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

PRT-treated platelets induce TGF-β production in splenic monocytes. The responses of monocytes and Mϕ were examined at 4 hours (day 0) and at days 1, 2, and 6. (A) Cells were gated for monocytes by selecting for CD19- CD11bHi F4/80low(and)intermediate NK1.1− and CD11c− events or gated for macrophages by selecting for CD19− CD11bintermediate/F4/80Hi events. (B) Frequency of CD86+, CD80+, MHCII+, and TGF-β+ events were determined for monocytes with fold change compared with nontransfused group plotted. (C) For macrophages, measurements of median fluorescent intensities for CD86, CD80, and MHCII and frequency of TGF-β+ events were made, with fold change compared with nontransfused group plotted. The frequency of total monocytes and macrophages were derived from total live events and the frequencies of CD86+, CD80+, MHCII+, and TGF-β+ events were derived from total monocytes or macrophages, respectively. “X” labels time points where <2 sets of data are available. Data are combined from 2 or 3 independent experiments (n = 5 per group). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

T-cell activation and cytokine production

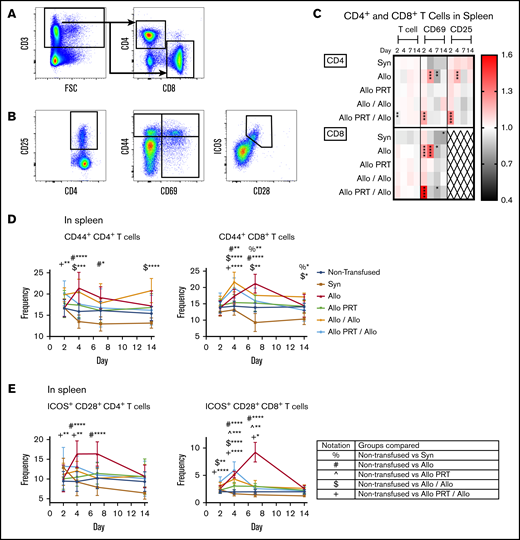

To evaluate T-cell responses to both untreated and UV+R-treated PRP, the same treatment groups were examined as described above in the “APC responses” section, with the addition of 2 groups: a single untreated syngeneic B6 PRP transfusion (Syn) control group and a group given untreated allogeneic BALB/c PRP transfusion followed by a second untreated allogeneic BALB/c PRP transfusion 2 weeks later (Allo/Allo). Mice were euthanized at 2, 4, 7, or 14 days after the final transfusion, and T-cell populations from the spleen and blood were evaluated. Upon activation, T cells upregulate surface expression of CD69, CD25, CD44 and costimulation receptors such as inducible T-cell costimulator (ICOS) and CD28.75-78 No differences in T-cell activation were observed for the Syn control, except for a reduction in CD69+ and CD44+ among splenic CD8+ T cells (Figures 3-4).

PRT-treated platelets induce only weak activation of splenic T cells and inhibit T-cell responses to subsequent untreated platelets. The responses of T cells were examined from the spleen at days 2, 4, 7, and 14. (A) Cells were gated on CD3+, followed by CD4+ or CD8+ events. FSC, forward scatter. (B) CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were then evaluated for frequency of CD25+, CD69+, CD44+, and ICOS+/CD28+. (C) Heat map shows fold changes in frequencies of each group compared with the nontransfused group for CD4+ T cells (top) or CD8+ T cells (bottom) (out of total CD3+ events) and CD69+ and CD25+ events (out of total CD4+ or CD8+ events, respectively). CD8+ T cells did not meet threshold of 100 positive events for CD25 and were therefore excluded (X). (D-E) Frequencies of CD44 expression (D) and ICOS+/CD28+ (E) out of total CD4+ or CD8+ T-cell events are plotted. Notation indicates significance between groups. Combined data from 5 independent experiments (n = 3-5 per group) are shown, and bars indicate mean and standard deviation. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001.

PRT-treated platelets induce only weak activation of splenic T cells and inhibit T-cell responses to subsequent untreated platelets. The responses of T cells were examined from the spleen at days 2, 4, 7, and 14. (A) Cells were gated on CD3+, followed by CD4+ or CD8+ events. FSC, forward scatter. (B) CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were then evaluated for frequency of CD25+, CD69+, CD44+, and ICOS+/CD28+. (C) Heat map shows fold changes in frequencies of each group compared with the nontransfused group for CD4+ T cells (top) or CD8+ T cells (bottom) (out of total CD3+ events) and CD69+ and CD25+ events (out of total CD4+ or CD8+ events, respectively). CD8+ T cells did not meet threshold of 100 positive events for CD25 and were therefore excluded (X). (D-E) Frequencies of CD44 expression (D) and ICOS+/CD28+ (E) out of total CD4+ or CD8+ T-cell events are plotted. Notation indicates significance between groups. Combined data from 5 independent experiments (n = 3-5 per group) are shown, and bars indicate mean and standard deviation. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001.

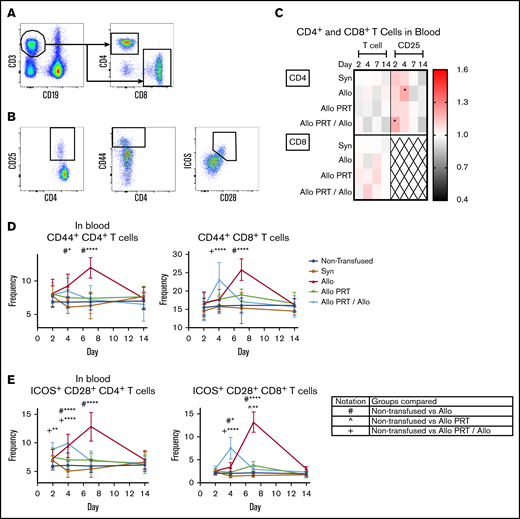

PRT-treated platelets induce only weak activation of blood T cells and inhibit T-cell responses to subsequent untreated platelets. The responses of T cells were examined from blood at days 2, 4, 7, and 14. (A) Cells were gated on CD3+/CD19−, followed by CD4+ or CD8+ events. (B) CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were then evaluated for frequency of CD25+, CD44+, and ICOS+/CD28+. (C) Heat map shows fold changes in frequencies of each group compared with the nontransfused group for CD4+ T cells (top) or CD8+ T cells (bottom) (out of total CD3+ events) or CD4+ CD25+ events (out of total CD4+ events). CD8+ T cells did not meet threshold of 100 positive events for CD25 and were therefore excluded (X). (D-E) Frequencies of CD44+ (D) or ICOS+/CD28+ (E) out of total CD4+ or CD8+ T-cell events, respectively. Notation indicates significance between groups. Data are combined from 3 independent experiments (n = 3 per group), and bars indicate mean and standard deviation. *P < .05, **P < .01, ****P < .0001.

PRT-treated platelets induce only weak activation of blood T cells and inhibit T-cell responses to subsequent untreated platelets. The responses of T cells were examined from blood at days 2, 4, 7, and 14. (A) Cells were gated on CD3+/CD19−, followed by CD4+ or CD8+ events. (B) CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were then evaluated for frequency of CD25+, CD44+, and ICOS+/CD28+. (C) Heat map shows fold changes in frequencies of each group compared with the nontransfused group for CD4+ T cells (top) or CD8+ T cells (bottom) (out of total CD3+ events) or CD4+ CD25+ events (out of total CD4+ events). CD8+ T cells did not meet threshold of 100 positive events for CD25 and were therefore excluded (X). (D-E) Frequencies of CD44+ (D) or ICOS+/CD28+ (E) out of total CD4+ or CD8+ T-cell events, respectively. Notation indicates significance between groups. Data are combined from 3 independent experiments (n = 3 per group), and bars indicate mean and standard deviation. *P < .05, **P < .01, ****P < .0001.

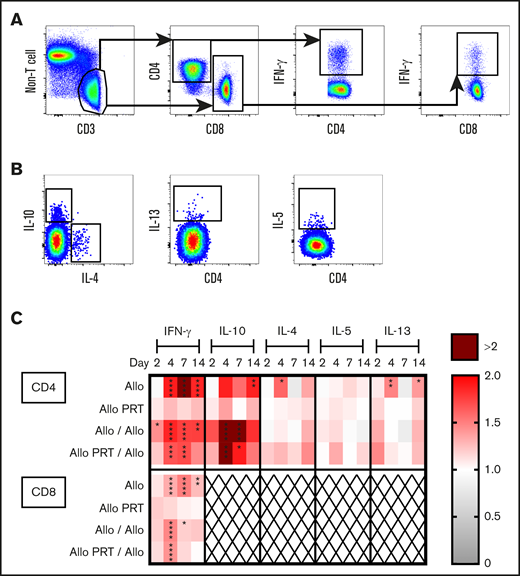

The Allo group mounted robust T-cell responses that appeared to peak at days 4 (CD4+) and 7 (CD8+) and resolve by day 14. Increases were observed in the spleen among CD4+ T cells for CD69+ and CD25+ on day 4 and for CD44+ and ICOS+/CD28+ on days 4 and 7 (Figure 3). Similarly, among CD8+ T cells, increases were seen in CD69+ on days 2 and 4 and CD44+ and ICOS+/CD28+ on days 4 and 7 (Figure 3). There were also reductions of CD69 among CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the spleen on day 7 (Figure 3C). The Allo response in the blood mirrored that of the spleen, with the exceptions that CD44+ was only elevated on day 7 for CD8+ T cells (Figure 4) and blood T cells did not express CD69. CD8+ T cells are known for CTL function and expression of interferon γ (IFN-γ), whereas CD4+ T cells regulate immunity via expression of IFN-γ, interleukin 4 (IL-4), IL-5, IL-13, and IL-10, among others.79 Robust cytokine production was observed for the Allo group, with increases of intracellular IFN-γ in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (days 4, 7, and 14) and intracellular IL-10 (day 14), IL-4 (day 4), and IL-13 (day 4 and 14) in CD4+ T cells (Figure 5).

PRT-treated platelets do not induce cytokine production by splenic T cells and alter the cytokine response to subsequent untreated platelets. Splenocytes from mice described in Figure 3 were stimulated for 3 hours and then stained for intracellular cytokine expression. (A) Cells were gated on CD3+/non-T-cell marker−, CD4+, or CD8+ T cells and IFN-γ+. (B) CD4+ T cells were gated on IL-10+, IL-4+, IL-13+, and IL-5+. (C) Heat map shows fold changes of each group compared with the nontransfused group for frequencies of cytokines out of total CD4+ T cells (top) or CD8+ T cells (bottom). CD8+ T cells did not meet threshold of 25 positive events for cytokines IL-10, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 and were therefore excluded (X). Data from 2 independent experiments are shown (n = 5 per group). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001.

PRT-treated platelets do not induce cytokine production by splenic T cells and alter the cytokine response to subsequent untreated platelets. Splenocytes from mice described in Figure 3 were stimulated for 3 hours and then stained for intracellular cytokine expression. (A) Cells were gated on CD3+/non-T-cell marker−, CD4+, or CD8+ T cells and IFN-γ+. (B) CD4+ T cells were gated on IL-10+, IL-4+, IL-13+, and IL-5+. (C) Heat map shows fold changes of each group compared with the nontransfused group for frequencies of cytokines out of total CD4+ T cells (top) or CD8+ T cells (bottom). CD8+ T cells did not meet threshold of 25 positive events for cytokines IL-10, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 and were therefore excluded (X). Data from 2 independent experiments are shown (n = 5 per group). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001.

Strikingly, the Allo PRT group showed virtually no signs of T-cell activation in vivo (Figures 3-5). There was only a small increase in ICOS+/CD28+ expression among CD8+ T cells on days 4 and 7 in the spleen (Figure 3E) and on day 7 in the blood (Figure 4E).

The Allo/Allo group showed signs of early but weak T-cell activation. Increases were seen in CD44+ among CD4+ T cells (days 4 and 14) and CD8+ T cells (days 4, 7, and 14), ICOS+/CD28+ among CD8+ T cells (days 2 and 4), IFN-γ among CD4+ (days 2, 4, 7, and 14) and CD8+ T cells (days 4 and 7), and IL-10+ among CD4+ T cells (days 4 and 7) (Figures 3 and 5).

The Allo PRT/Allo group appeared to have a short and weak primary T-cell response, though there were some signs of an early memory-like response. In the spleen, while the frequencies of total CD4+ T cells decreased (day 2), CD4+ T cells had increased frequencies of CD69+, CD25+, and CD44+ (day 2); ICOS+/CD28+ (days 2 and 4); IFN-γ+ (days 4 and 7); and IL-10+ (days 4 and 7) events (Figures 3 and 5). Among CD8+ T cells, there were increases in CD69+ (day 2, followed by a decrease at day 7), CD44+ (day 4), ICOS+/CD28+ (days 2, 4, and 7), and IFN-γ+ (day 4) events (Figures 3 and 5). In the blood, the Allo PRT/Allo group had elevated CD25+ (day 2) and ICOS+/CD28+ (days 2 and 4) among CD4+ T cells and CD44+ (day 4) and ICOS+/CD28+ (day 4) among CD8+ T cells (Figure 4). These responses in the blood were the best evidence of recall responses in this group, with higher responses seen at day 4 in the Allo PRT/Allo group compared with the Allo group, though these resolved rapidly by day 7.

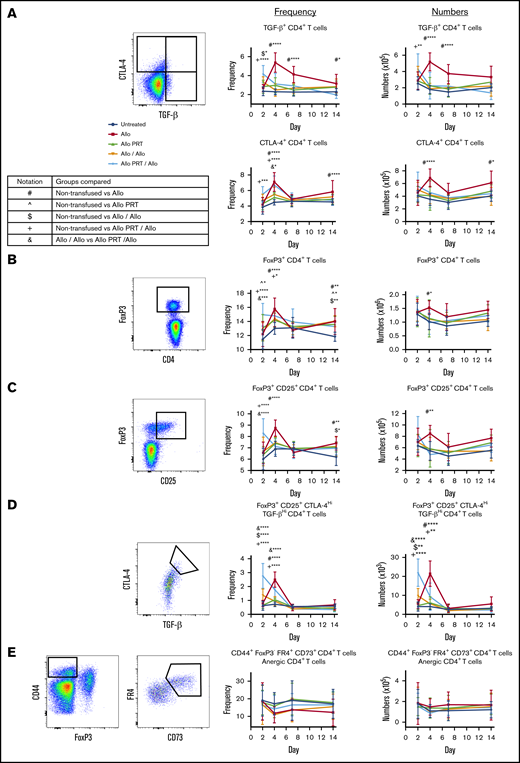

Treg-cell induction

Peripheral tolerance can be induced by several mechanisms, including T-cell deletion, anergy, or Tregs cells that exert tolerance through CTLA-4 and the inhibitory cytokines TGF-β and IL-10.69 The Allo group had increased numbers and/or frequency of TGF-β+ CD4+ T cells (days 4 and 7); CTLA-4+ CD4+, FoxP3+ CD4+ and FoxP3+/CD25+ CD4+ T cells (days 4 and 14); and “memory” Treg cells (FoxP3+/CD25+/CTLA-4Hi/TGF-βHi CD4+ T cells; day 4) (Figure 6A-D). Allo PRT only showed an increased frequency of FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells (days 2 and 14) (Figure 6B) but no other changes. The Allo/Allo group had increased frequency and/or numbers of memory Treg cells and TGF-β+ CD4+ T cells (day 2) and FoxP3+ CD4+ and FoxP3+/CD25+ CD4+ T cells (day 14) (Figure 6D). The Allo PRT/Allo group showed increased frequency and/or numbers of TGF-β+ CD4+ and FoxP3+/CD25+ CD4+ T cells (day 2) and memory Treg cells and CTLA-4+ CD4+ and FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells (day 2 and 4) (Figure 6A-D). The Allo PRT/Allo group, when compared with the Allo/Allo group, had an increased number and/or frequency of FoxP3+/CD25+ CD4+ T cells (day 2), CTLA-4+ CD4+ and FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells (day 4), and memory Treg cells (days 2 and 4), (Figure 6A-D). No differences in anergic (CD44+/FoxP3− folate receptor 4+/CD73+ CD4+) T cells were observed (Figure 6E).

PRT-treated platelet transfusion may induce early Treg-cell activity but no indicators of T-cell anergy. Splenocytes from mice described in Figure 3 were evaluated for markers of regulatory T cells and T-cell anergy. Representative gating selected for CD3+ CD4+ T cells that were positive for CTLA-4+ or TGF-β+ (A), regulatory FoxP3+ (B), regulatory FoxP3+/CD25+ (C), a subset of regulatory FoxP3+ CD25+ cells that were CTLA-4Hi or TGF-βHi (D), and anergic CD3+ CD4+ T cells by CD44+/FoxP3− folate receptor 4 (FR4)Hi/CD73Hi events (E). Frequencies (middle) and total numbers (right) are plotted. Notation indicates significance between groups. Data from 2 independent experiments (n = 5 per group) are shown, and bars indicate mean and standard deviation. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001.

PRT-treated platelet transfusion may induce early Treg-cell activity but no indicators of T-cell anergy. Splenocytes from mice described in Figure 3 were evaluated for markers of regulatory T cells and T-cell anergy. Representative gating selected for CD3+ CD4+ T cells that were positive for CTLA-4+ or TGF-β+ (A), regulatory FoxP3+ (B), regulatory FoxP3+/CD25+ (C), a subset of regulatory FoxP3+ CD25+ cells that were CTLA-4Hi or TGF-βHi (D), and anergic CD3+ CD4+ T cells by CD44+/FoxP3− folate receptor 4 (FR4)Hi/CD73Hi events (E). Frequencies (middle) and total numbers (right) are plotted. Notation indicates significance between groups. Data from 2 independent experiments (n = 5 per group) are shown, and bars indicate mean and standard deviation. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001.

Adoptive transfer

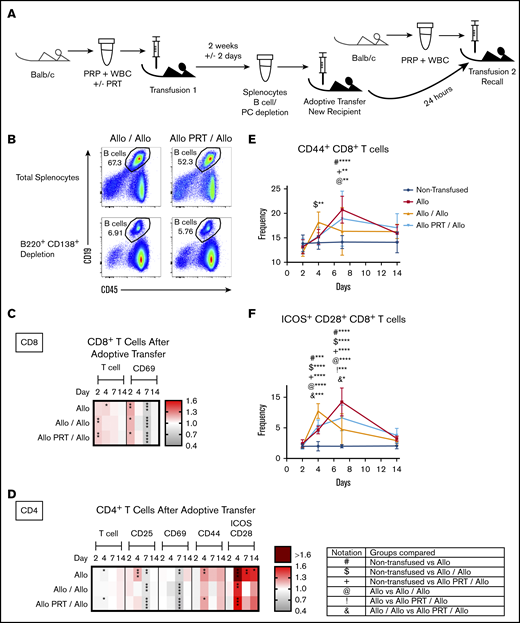

Adoptive transfer studies were conducted to avoid complications from potent anti-BALB/c antibodies at the time of secondary challenge for the Allo/Allo group,61 which could mediate removal of the antigen prior to T-cell activation. This also examined whether tolerance seen in the Allo PRT/Allo group was transferable. As shown in Figure 7A, B6 mice were given a single transfusion with either untreated or UV+R-treated BALB/c PRP, and then their splenocytes were harvested 2 weeks later, depleted of B cells and plasma cells (Figure 7B), and transferred into naive B6 mice. Host mice were then given a second transfusion with untreated BALB/c PRP (Allo/Allo and Allo PRT/Allo groups), with responses compared with B6 mice given either no transfusion or a single untreated BALB/c PRP alone (Allo).

Partial transfer of T-cell tolerance induced by transfusion of UV+R-treated platelets into naive recipient mice. (A) B-depleted splenocytes from mice given a single PRT-treated or untreated allogeneic PRP transfusion were adoptively transferred into naive recipient mice, and the recipients were examined for T-cell responses after a secondary allogeneic challenge with untreated allogeneic PRP transfusion. The recall responses were compared with mice given a single untreated allogeneic PRP transfusion and with nontransfused mice. PC, plasma cell. (B) Representative flow cytometry plots of pooled splenocytes prior to B-cell/plasma cell depletion (top) and after depletion (B220+ CD138+; bottom) for the Allo/Allo group (left) and Allo PRT/Allo group (right) that was used for adoptive transfer. (C-D) Heat maps show fold changes in frequency of activation markers for CD8+ T cells (C) and CD4+ T cells (D) for each group compared with the nontransfused group. (E-F) Frequency of CD44+ events (E) and ICOS+/CD28+ events (F) in the CD8+ T-cell gate. Notation indicates significance between groups. Combined data from 2 independent experiments are shown (n = 3-8 mice per group), and bars indicate mean and standard deviation. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001.

Partial transfer of T-cell tolerance induced by transfusion of UV+R-treated platelets into naive recipient mice. (A) B-depleted splenocytes from mice given a single PRT-treated or untreated allogeneic PRP transfusion were adoptively transferred into naive recipient mice, and the recipients were examined for T-cell responses after a secondary allogeneic challenge with untreated allogeneic PRP transfusion. The recall responses were compared with mice given a single untreated allogeneic PRP transfusion and with nontransfused mice. PC, plasma cell. (B) Representative flow cytometry plots of pooled splenocytes prior to B-cell/plasma cell depletion (top) and after depletion (B220+ CD138+; bottom) for the Allo/Allo group (left) and Allo PRT/Allo group (right) that was used for adoptive transfer. (C-D) Heat maps show fold changes in frequency of activation markers for CD8+ T cells (C) and CD4+ T cells (D) for each group compared with the nontransfused group. (E-F) Frequency of CD44+ events (E) and ICOS+/CD28+ events (F) in the CD8+ T-cell gate. Notation indicates significance between groups. Combined data from 2 independent experiments are shown (n = 3-8 mice per group), and bars indicate mean and standard deviation. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001.

The Allo control group for the adoptive transfer (Figure 7C-F) showed robust CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell activation, generally consistent with the Allo group responses described in Figure 3. The CD4+ T-cell responses for the Allo/Allo and Allo PRT/Allo groups after adoptive transfer were similar, though the decreased CD4+ T-cell frequency and increased CD44+ expression on day 4 was lacking in the Allo/Allo group. Decreases in CD69+ on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and CD25+ CD4+ T cells were observed on day 7 for all groups, and CD4+ T-cell frequency decreased for the Allo and Allo PRT/Allo groups on day 4 (Figure 7C-D).

Differential expression of activation markers after adoptive transfer was observed for CD8+ T-cell activation markers between groups (Figure 7E-F). While the Allo group had a robust primary response, the Allo/Allo group showed an early memory response, and the Allo PRT/Allo group had a suppressed primary response (Figure 7E-F). Early elevations in CD8+ T-cell frequency and expression of CD69+ were seen in all transfused groups (Figure 7C). Expression of CD44+ and ICOS+/CD28+ indicates that the CD8+ T-cell response in the Allo/Allo group peaked earlier (at day 4 vs day 7) in the Allo and Allo PRT/Allo groups (Figure 7E-F). While the timing of the Allo PRT/Allo and Allo CD8+ T-cell responses was similar, the peak was reduced in the Allo PRT/Allo group, with fewer ICOS+/CD28+ CD8+ T cells at day 7 (Figure 7F).

Discussion

Pathogen reduction with UV+R can reduce alloantibody responses and induce partial antigen-specific immune tolerance to subsequent untreated allogeneic PRP transfusions.12,18,19,21 This study examined the mechanism of this partial immune tolerance induction by evaluating the in vivo cellular immune responses of untreated PRP and UV+R-treated PRP in recipient mice. Overall, a single untreated allogeneic transfusion mounted a robust primary response and 2 consecutive such transfusions yielded an early memory inflammatory cellular response. Conversely, a single UV+R-treated PRP transfusion failed to induce cellular immune responses and dampened cellular T-cell responses to subsequent untreated allogeneic exposure. The suppressed immune responses appear to be attributed to tolerogenic CD11b+ CD4+ cDCs and monocytes, as well as Treg-cell induction. Importantly, T cells from mice that received a PRT-treated PRP transfusion conferred a small but significant CD8+ T-cell tolerance in naive recipients.

Direct presentation, where alloantigens on donor APCs present to the recipient T cells,25 was likely not a major contributor. UV+R-treated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells are unable to form conjugates with allogeneic T cells in vitro,21 and microchimerism was barely detectable 4 hours after untreated allogeneic transfusion and rapidly cleared within 24 to 48 hours (data not shown). Recipient cDCs, Mϕs, and B cells were activated, however, suggesting a role for indirect presentation of alloantigens, in line with other work.50-53 Others have shown platelets can directly activate cDCs,31,34,35,46,47,49,50 but this work specifically highlights recipient CD8+ cDCs as the critical subset in PRP alloimmunization, further supporting a role for CTL in platelet clearance.54,73 Although the response to untreated PRP showed similar effect sizes among CD11b+ CD4+ cDCs, only UV+R-treated PRP induced significantly elevated TGF-β expression among CD11b+ CD4+ cDCs and monocytes. Monocytes are generally considered inflammatory but can be immunosuppressive in some settings.80,81 CD11b+ CD4+ cDCs primarily regulate CD4+ T cells and can potentiate induction of peripheral Treg cells,73 which may explain the early induction of Treg cells in these mice. Prior studies have shown UV+R-treated WBCs take on apoptotic characteristics, and processing of these apoptotic-like cells may drive the tolerogenic phenotype we observed.22,82-84

Our findings are consistent with studies demonstrating that allogeneic platelets can give rise to T-cell responses50-54 but clarify the kinetics and quality of the alloimmune response. We demonstrate that the primary alloresponse includes CD4+ T cells with both T helper type 1 (Th1) and Th2 phenotypes,26 whereas the recall response skews toward a Th1 phenotype. We demonstrate that allogeneic PRP induces both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses but that the kinetics differ, with splenic CD4+ responses generally peaking earlier than CD8+ responses or CD4+ responses in the blood. Finally, we find that allogeneic PRP induces Treg cells, likely to regulate natural T-effector-cell contraction. Platelet transfusions in the clinic have been associated with increased recurrence or morbidity in acute leukemia,85 possibly due to impaired host immunity via induction of human Treg cells by platelet supernatant.86,87

In stark contrast to untreated PRP, UV+R treatment prevented T-cell responses to allogeneic PRP transfusions in vivo, consistent with in vitro reports.18,21,59 As UV+R treatment blocked the primary T-cell response, the response to a subsequent untreated transfusion in the Allo PRT/Allo group was likely a primary response shut down by regulatory mechanisms. This fits with the kinetics of the response in the Allo PRT/Allo group, and T-cell activation and cytokine expression appeared dampened when compared with the Allo/Allo group. A possible tolerance mechanism is that tolerogenic monocytes and CD11b+ CD4+ cDCs potentiate the induction of FoxP3+ CD4+ Treg cells in the initial transfusion of UV+R-treated PRP, resulting in suppression of responses to subsequent untreated allogeneic exposure by FoxP3+/CD25+/CTLA-4Hi/TGF-βHi CD4+ “memory” Treg cells.78 Importantly, this memory Treg-cell response was elevated at the earliest time point evaluated in the Allo PRT/Allo group compared with the other groups. The Allo PRT/Allo group also showed early CD4+ T-cell activation not observed in the Allo/Allo group, which could be activation of Treg cells, as the frequencies of activated T cells and Treg cells were similar in this group. Tolerance through deletion or anergy88-91 was not observed; however, as the analysis was based on total T-cell numbers, differences may have been below the limit of detection.

Although no evidence of CD8+ T-cell memory was seen in the spleen for the Allo PRT/Allo group, there was some early activation seen in the blood. This suggests a small fraction of CD8+ T cells that were largely undetectable in the primary response may have formed a modest effector memory T-cell response that remains in circulation.78,92 This may account for the small fraction of CD8+ T cells that increased coexpression of ICOS/CD28 in the Allo PRT group. Consistent with this, repeated exposures of UV+R-treated PRP eventually overcome protection and result in alloantibodies in mice.19 However, any effector memory cell activity generated in response to transfused UV+R PRP may have been counterbalanced by concurrent induction of Treg cells and tolerizing activity from APCs.

T-cell responses in the Allo/Allo group appear early, consistent with a secondary challenge, but were weaker than anticipated, possibly due to the presence of potent antibodies at the time of secondary challenge that cleared antigen rapidly, reducing T-cell responses. We addressed this issue with the adoptive transfer experiments, so that mice receiving secondary challenge would have T cells from the primary exposure, but not the antibodies. Mice that received an adoptive T-cell transfer from mice given untreated PRP exhibited an early memory CD8+ T-cell response to secondary challenge with untreated PRP. In contrast, mice that received an adoptive transfer from mice given UV+R-treated PRP prior to secondary challenge with untreated PRP showed 2 key features: (1) the early response for CD8+ T cells was similar to a single allogeneic transfusion indicating the absence of a memory response, and (2) the peak for ICOS+/CD28+ CD8+ T cells was slightly reduced compared with the peak of the control, suggesting some CD8+ T-cell tolerance was transferred. The partial transfer of tolerance may be due to insufficient numbers of transferred Treg cells and/or suggest a critical role for APCs in driving the tolerance in this model.

A potential limitation in extrapolating our findings to the clinical setting is that we focused on nonleukoreduced PRP, as WBCs are required for the tolerance observed with UV+R (supplemental Figure 1). Leukoreduction, while not universal, is standard practice in the developed world. As shown in supplemental Figure 2, and in some of our earlier published work, T-cell and antibody responses to leukoreduced PRP are significantly lower than responses to untreated nonleukoreduced PRP.18,19 Intriguingly, pathogen reduction appears to effectively block alloimmunization even in the absence of leukoreduction.

Preclinical studies have suggested UV+R treatment reduces the risk of alloimmunization.18-20,93 Contrastingly, clinical studies, including a systematic review of various PRT technologies and a recent trial of hemato-oncological patients, concluded that PRT does not prevent alloimmunization.17,94 However, the interpretation of these studies may be complicated by known confounding factors that could increase the risk of alloimmunization.95 Trials to date have included storage prior to transfusion, concurrent use of γ irradiation with PRT, and exposure to other untreated allogeneic blood products, all of which could increase alloimmunization risk independent of PRT.17,94-98 These confounding factors are well reviewed by Stolla.95 Further work is needed parse out the role of PRT from other confounding factors in the clinic that may increase the risk of alloimmunization.

For original data, please contact the corresponding author, Rachael P. Jackman, at rjackman@vitalant.org.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank John W. Heitman, Orsolya Darst, and Sophia Blessinger (all from Vitalant Research Institute) for technical assistance.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01 HL133024 and R01 HL144501) and, in part, by Terumo BCT, which provided equipment and materials for pathogen reduction.

Authorship

Contribution: J.Q.T. designed research, performed research, collected, analyzed, and interpreted data, performed statistical analysis and wrote manuscript; M.O.M. provided intellectual support and feedback, interpreted data, and reviewed and edited manuscript; and R.P.J. designed research, performed research, analyzed and interpreted data, and reviewed and edited manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Rachael P. Jackman, Vitalant Research Institute, 270 Masonic Ave, San Francisco, CA 94118; e-mail: rjackman@vitalant.org.

References

Author notes

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.