Key Points

Genetic or pharmacological inhibition of NFATC2 in mice provides protection from hypersensitivity reactions to antileukemic asparaginase.

Loss of NFATC2 in mice leads to lower Th2 cytokines levels, lower IgE and antigen-specific antibody levels, and decreased FcεR1 expression.

Abstract

The family of nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) transcription factors plays a critical role in mediating immune responses. Our previous clinical pharmacogenetic studies suggested that NFATC2 is associated with the risk of hypersensitivity reactions to the chemotherapeutic agent L-asparaginase (ASNase) that worsen outcomes during the treatment of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. We therefore hypothesized that the genetic inhibition of NFATC2 would protect against the development of anti-ASNase antibodies and ASNase hypersensitivity. Our study demonstrates that ASNase-immunized NFATC2-deficient mice are protected against ASNase hypersensitivity and develop lower antigen-specific and total immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels compared with wild-type (WT) controls. Furthermore, ASNase-immunized NFATC2-deficient mice develop more CD4+ regulatory T cells, fewer CD4+ interleukin-4–positive (IL-4+) cells, higher IL-10/TGF-β1 levels, and lower IL-4/IL-13 levels relative to WT mice. Basophils and peritoneal mast cells from ASNase-immunized, but not naïve, NFATC2-deficient mice had lower FcεRI expression and decreased IgE-mediated mast cell activation than WT mice. Furthermore, ASNase-immunized, but not naïve, NFATC2-deficient mice developed less severe shock than WT mice after induction of passive anaphylaxis or direct histamine administration. Thus, inhibition of NFATC2 protects against ASNase hypersensitivity by impairing T helper 2 responses, which may provide a novel strategy for attenuating hypersensitivity and the development of antidrug antibodies, including to ASNase.

Introduction

The bacterial enzyme L-asparaginase (ASNase) is a critical component of multidrug chemotherapy for pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).1 The most common adverse reaction to ASNase in children is the development of an antidrug antibody response that can decrease plasma drug levels, mediate hypersensitivity reactions, and increase the risk of relapse.2-7 ASNase hypersensitivity most commonly occurs after induction therapy,4 suggesting that patients are likely sensitized to ASNase during initial drug use and experience hypersensitivity reactions upon subsequent reexposure. The mechanism of the adverse reaction therefore likely includes ASNase processing by antigen-presenting cells, epitope presentation on major histocompatibility complex class 2 molecules, CD4+ T-cell activation/differentiation, and T-cell–dependent B-cell differentiation to plasma and memory B cells.

Members of the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) family of transcription factors can affect antibody responses to protein-based therapeutics, such as ASNase, through their important roles in immunity. Consistent with this, our previous genome-wide association study (GWAS) associated the rs6021191 intronic variant of NFAT (NFATC2), which increases NFATC2 messenger RNA expression, with a higher risk of ASNase hypersensitivity among pediatric ALL patients.8 In contrast, ALL patients who have trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) overexpress the NFAT inhibitors DYRK1A and DSCR19 and have a lower risk of developing ASNase hypersensitivity.8 These observations suggest that the NFAT pathway promotes immune responses to ASNase and that inhibition of NFAT may protect against ASNase hypersensitivity.

The NFAT family of transcription factors encodes 5 distinct proteins, in which 4 NFAT family members, NFATC1 (NFAT2), NFATC2 (NFAT1), NFATC3 (NFAT4), and NFATC4 (NFAT3), are dephosphorylated by calcineurin, a Ca2+-dependent serine/threonine phosphatase, and translocate to the nucleus, where they associate with target DNA sequences and regulate gene expression.10-12 Of the known NFAT isoforms, NFATC2 accounts for 80% to 90% of total NFAT in resting T cells and is known for regulating the expression of the cytokines interferon γ (INF-γ), interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-5, and IL-13.11,13,14 Previous studies using NFATC2-deficient mice have suggested that NFATC2 suppresses T helper (Th)2 allergic immune responses15 ; however, other studies have demonstrated that NFATC2 deficiency suppresses experimental colitis16 and increases the immunosuppressive function of regulatory T cells (Tregs) during airway hyperresponsiveness.17 These disparate observations, along with the results of our clinical studies, led us to use NFATC2-deficient mice to elucidate the role of this transcription factor in immune responses to ASNase. Here, we demonstrate that NFATC2 deficiency or pretreatment with the NFAT inhibitor 11R-VIVIT protects mice from ASNase hypersensitivity by suppressing Th2 responses.

Materials and methods

Mice

NFATC2-deficient mice were purchased from Mutant Mouse Resource & Research Centers (Chapel Hill, NC). Founders were on a mixed 129/SvJ and C57BL/6J background and were subsequently backcrossed to C57BL/6 for 10 generations. Eight- to 12-week-old mice were enrolled in experiments, and all animal experiments were performed under protocols approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Cares and Use Committee.

Determining differences in histamine-induced anaphylaxis in WT and NFATC2-deficient mice

Naïve and ASNase-immunized wild-type (WT) and NFATC2 knockout (KO) mice received IV histamine (2 mg in 100 µL of phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]), as previously described,18 and anaphylaxis was quantified by measuring the decrease in rectal temperature.

Blocking anaphylaxis exacerbation by Th2 cytokines in WT mice with anti–IL-4Rα mAb

ASNase-immunized mice received 3 mg of anti-mouse IL-4Rα monoclonal antibody (mAb; M1) or an isotype control mAb (GL117) intraperitoneally, as described previously,19 3 days and 1 day before being challenged with 2 mg of IV histamine. The severity of anaphylaxis was quantified by measuring the decrease in rectal temperature.

Administration of 11R-VIVIT ameliorates experimental ASNase-induced hypersensitivity

C57BL6/J WT mice received 11R-VIVIT at 10 mg/kg intraperitoneally in PBS 5 minutes after each ASNase sensitization dose. Blood samples were collected 1 day before inducing anaphylaxis, and all mice were challenged with 100 μg of IV Escherichia coli ASNase.

ASNase immunization, antibodies, drug levels, anaphylaxis, and flow cytometry

A detailed description of additional methods used in this study is found in the supplemental Data.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 8 statistical software, using 2-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test or 2-tailed, unpaired Student t test. All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. A value of P ≤ .05 was considered significant, as summarized in supplemental Table 1.

Results

NFATC2 KO mice are protected against ASNase hypersensitivity

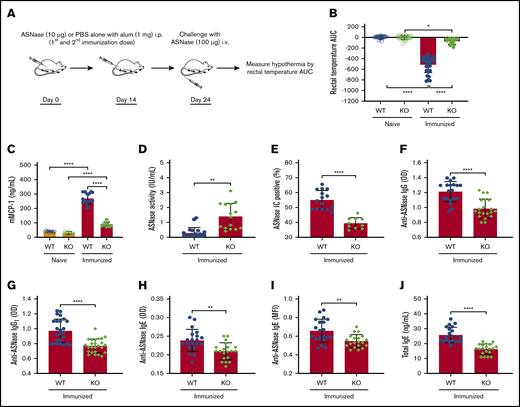

The impetus of our current study was our previous clinical observation that host factors that increase or decrease NFATC2 protein levels have a corresponding effect on the risk of ASNase hypersensitivity in pediatric ALL patients.8 Consequently, we used NFATC2-deficient mice20 and our murine model of ASNase hypersensitivity21 to elucidate the role of NFATC2 on ASNase hypersensitivity and the development of antidrug antibodies. To determine whether the KO mice were protected from ASNase hypersensitivity, we immunized mice with ASNase or PBS and challenged them with ASNase (Figure 1A). Our data demonstrate that NFATC2 deficiency protects from ASNase hypersensitivity, as determined by the onset of drug-induced hypothermia (an indicator of shock), detected by measuring decreases in rectal temperature after drug administration and quantified by estimating the area under the temperature curve (Figure 1B). Also, ASNase-immunized and challenged KO mice had lower serum mMCP-1 (a measure of mast cell degranulation; Figure 1C), higher ASNase drug levels (Figure 1D), fewer ASNase (Figure 1E), lower anti-ASNase total IgG, IgG1, and IgE levels (Figure 1F-I), and lower total IgE levels (Figure 1J) relative to WT mice. The decreased antibody levels and fewer ASNase ICs suggest that NFATC2 deficiency could protect against hypersensitivity reactions, at least partially, by downmodulating both the IgE/FcεR1 and IgG/FcγRIII pathways of anaphylaxis.22,23 Because NFATC2 regulates cytokine expression, and cytokines can influence antibody and mast cell responses and responses to mast cell–produced mediators, we next investigated the effect of NFATC2 deficiency on Th2 cells and cytokines.

NFATC2-deficient mice are protected against the development of anti-ASNase antibodies and ASNase hypersensitivity. (A) Schematic representation of ASNase immunization and challenge protocol. (B) Immunized NFATC2-deficient (KO) mice are protected against developing hypothermia when challenged with ASNase. (C-E) KO mice have lower mMCP-1 levels (C), higher ASNase drug or activity levels (D), and fewer detectable ASNase immune complexes (ICs) (E) in plasma after the ASNase challenge. (F-J) Plasma antibody levels were assessed after immunization and KO mice developed lower anti-ASNase total immunoglobulin G (IgG) (F), anti-ASNase IgG1 (G), anti-ASNase IgE antibody responses (H-I), and total IgE (J) relative to WT mice. *P < .05; **P < .01; ****P < .0001. alum, aluminium hydroxide adjuvant; AUC, area under the curve; i.p., intraperitoneal; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; OD, optical density.

NFATC2-deficient mice are protected against the development of anti-ASNase antibodies and ASNase hypersensitivity. (A) Schematic representation of ASNase immunization and challenge protocol. (B) Immunized NFATC2-deficient (KO) mice are protected against developing hypothermia when challenged with ASNase. (C-E) KO mice have lower mMCP-1 levels (C), higher ASNase drug or activity levels (D), and fewer detectable ASNase immune complexes (ICs) (E) in plasma after the ASNase challenge. (F-J) Plasma antibody levels were assessed after immunization and KO mice developed lower anti-ASNase total immunoglobulin G (IgG) (F), anti-ASNase IgG1 (G), anti-ASNase IgE antibody responses (H-I), and total IgE (J) relative to WT mice. *P < .05; **P < .01; ****P < .0001. alum, aluminium hydroxide adjuvant; AUC, area under the curve; i.p., intraperitoneal; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; OD, optical density.

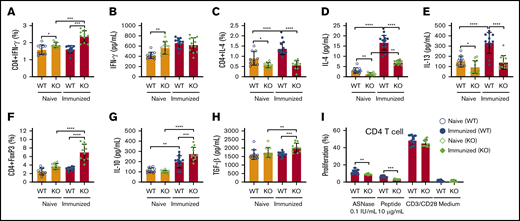

NFATC2 KO mice have decreased Th2 responses, attenuated CD4+ T-cell proliferation, and more regulatory CD4+ T cells

To more completely identify how NFATC2 contributes to ASNase hypersensitivity, we measured CD4+ T-cell frequency and the expression of Th1 and Th2 cytokines in naïve and ASNase-immunized WT and KO mice. As previously reported, we found that naïve NFATC2-deficient mice developed splenomegaly, with a similar frequency of total leukocytes (CD45+) and a slight increase in splenic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells relative to WT mice (supplemental Figure 1A-C).20 Furthermore, the spleens from naïve KO mice had more Th1 cells (CD4+INF-γ+) and higher plasma INF-γ levels than those from naïve WT mice (Figure 2A-B). Also, naïve KO mice had fewer splenic CD4+IL-4+ cells and lower levels of the Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 than naïve WT mice (Figure 2C-E). The decreased IL-4 and IL-13 responses were even more pronounced in KO mice after ASNase immunization (Figure 2C-E). We also observed that ASNase-immunized KO mice developed more CD4+ Tregs and higher serum levels of their associated inhibitory cytokines, IL-10 and TGF-β1 (Figure 2F-H). Because IL-4 and IL-13 promote IgE production, mast cell responses, and sensitivity to mast cell–produced mediators, these changes in cytokine responses to ASNase in KO mice likely contribute to the decreased severity of ASNase hypersensitivity in these mice.24,25

NFATC2 deficiency attenuates Th2 responses, decreases ASNase-specific CD4+T-cell proliferation, and increases regulatory T cells after ASNase immunization. (A-H) Naïve NFATC2 KO mice have more CD4+ INF-γ+ T cells (A) and higher plasma INF-γ levels (B) than WT mice. Naïve and immunized KO mice have fewer CD4+IL-4+ T cells (C) and less plasma IL-4 and IL-13 (D-E) compared with WT controls. After ASNase immunization, KO mice develop more CD4+ Tregs (F) and have higher plasma IL-10 (G) and TGF-β1 levels (H) than WT controls. (I) Immunized KO mice have decreased splenic CD4+ T-cell proliferation in response to ASNase or an ASNase T-cell epitope relative to immunized WT control mice. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001.

NFATC2 deficiency attenuates Th2 responses, decreases ASNase-specific CD4+T-cell proliferation, and increases regulatory T cells after ASNase immunization. (A-H) Naïve NFATC2 KO mice have more CD4+ INF-γ+ T cells (A) and higher plasma INF-γ levels (B) than WT mice. Naïve and immunized KO mice have fewer CD4+IL-4+ T cells (C) and less plasma IL-4 and IL-13 (D-E) compared with WT controls. After ASNase immunization, KO mice develop more CD4+ Tregs (F) and have higher plasma IL-10 (G) and TGF-β1 levels (H) than WT controls. (I) Immunized KO mice have decreased splenic CD4+ T-cell proliferation in response to ASNase or an ASNase T-cell epitope relative to immunized WT control mice. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001.

In contrast to the differences in T-cell differentiation and cytokine responses, there were no differences in CD4+ T-cell proliferation by anti-CD3/CD28 antibody–stimulated splenocytes from naive or ASNase-immunized WT and KO mice (Figure 2I; supplemental Figure 2). However, the CD4+ T-cell proliferation of ASNase-immunized KO splenocytes in response to ASNase or an ASNase T-cell epitope peptide (212PKVGIVYNYANASDLPAKA231)26,27 was decreased relative to ASNase-immunized WT mice (Figure 2I). Our data indicate that there may be no defect in T-cell antigen receptor signaling associated with NFATC2 deficiency, but rather that KO mice develop fewer ASNase-specific CD4+ T cells after immunization.

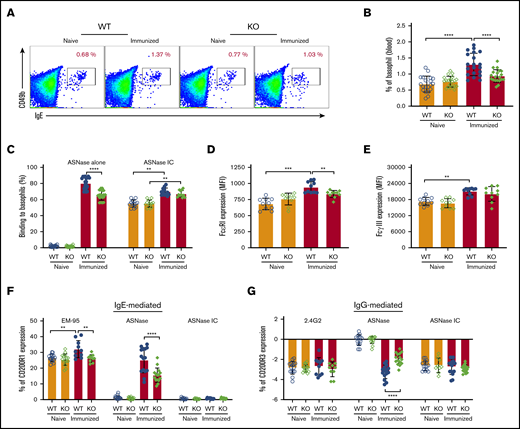

Attenuation of IgE-mediated basophil activation in NFATC2 KO mice

Our previous data indicate that hypersensitivity to ASNase can be mediated via both the IgE/FcεR1 and IgG/FcγRIII pathways of anaphylaxis, where both Fc receptors are expressed in basophils and mast cells.28 Interestingly, we found that the basophil frequency among the peripheral blood cells was lower in immunized, but not naïve, KO mice compared with WT controls (Figure 3A-B). The recognition or binding of fluorochrome-labeled ASNase to basophils required immunization and was greater in immunized WT rather than KO mice (Figure 3C). Furthermore, the binding of preformed ICs to the naïve basophils of WT and KO mice was equivalent but increased after immunization (Figure 3C). Immunization increased both the FcεRI and FcγRIII expression of basophils in WT but not KO mice (Figure 3D-E). Also, incubation of peripheral blood cells with ASNase activated more basophils from immunized WT than KO mice through both the IgE/FcεRI-mediated and the IgG/FcγRIII pathways (Figure 3F-G). Incubation with the anti-IgE mAb EM-95 similarly increased CD200R1 more on basophils from immunized WT than KO mice. In contrast, the effect of anti-FcγRIIB/RIII mAb 2.4G2 or ASNase ICs did not differ between mouse strains. These observations suggest that basophils from immunized KO mice are less responsive to antigen because of attenuated IgE levels, FcεRI expression, and ASNase ICs levels relative to immunized WT mice.

NFATC2-deficient mice have attenuated IgE-mediated anaphylaxis. (A-B) ASNase-immunized NFATC2 KO mice have fewer peripheral blood basophils than immunized WT mice. (C) Immunized KO mice have decreased basophil ASNase-specific recognition relative to WT mice, but no difference in the binding to ASNase ICs. (D) Basophil FcεRI expression increases after ASNase immunization but is lower in KO mice relative to controls. (E) Basophil FcγRIIB/RIII expression increases after ASNase immunization but is similar between WT and KO mice. (F-G) IgE- and IgG-mediated basophil activation is attenuated in KO mice compared with WT controls, but there is no difference in ASNase IC–induced basophil activation between WT and KO mice. **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001.

NFATC2-deficient mice have attenuated IgE-mediated anaphylaxis. (A-B) ASNase-immunized NFATC2 KO mice have fewer peripheral blood basophils than immunized WT mice. (C) Immunized KO mice have decreased basophil ASNase-specific recognition relative to WT mice, but no difference in the binding to ASNase ICs. (D) Basophil FcεRI expression increases after ASNase immunization but is lower in KO mice relative to controls. (E) Basophil FcγRIIB/RIII expression increases after ASNase immunization but is similar between WT and KO mice. (F-G) IgE- and IgG-mediated basophil activation is attenuated in KO mice compared with WT controls, but there is no difference in ASNase IC–induced basophil activation between WT and KO mice. **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001.

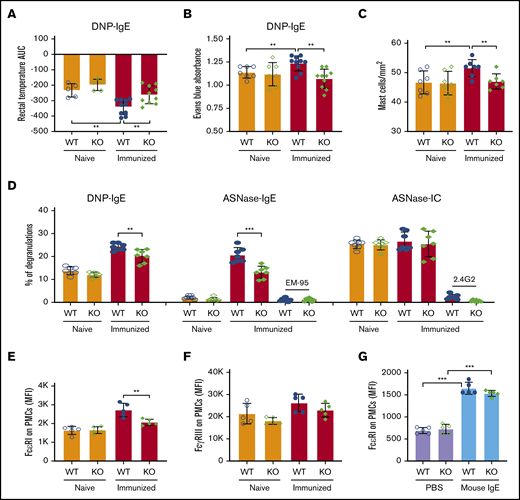

NFATC2 deficiency attenuates IgE-mediated mast cell degranulation and anaphylaxis via decreased expression of the IgE receptor

We next used several models of in vivo passive anaphylaxis in naïve and ASNase-immunized mice to verify protection from IgE-mediated anaphylaxis by NFATC2 deficiency and to interrogate the effect of NFATC2 on mast cell function. Using a model of passive systemic anaphylaxis, WT and NFATC2 KO mice were sensitized with anti-dinitrophenyl (DNP) IgE and challenged the next day with DNP–human serum albumin (HSA) to induce anaphylaxis (supplemental Figure 3A). As expected, DNP-HSA strongly induced anaphylaxis in anti-DNP IgE–sensitized WT mice, which was further exacerbated by ASNase immunization (Figure 4A). ASNase-immunized, but not naïve, KO mice developed significantly less severe anaphylaxis than similarly treated WT mice (Figure 4A).

IgE-mediated PSA, PCA, and mast cell degranulation are attenuated in immunized NFATC2-deficient mice. (A) IgE-induced passive systemic anaphylaxis (PSA) is attenuated in NFATC2 KO mice. (B-C) Similarly, anti-DNP IgE-mediated passive cutaneous anaphylaxis (PCA) is attenuated in KO mice (B) and leads to fewer mast cells in the ear pinnae of mice (C). (D) IgE- but not IC-mediated ex vivo mast cell degranulation is attenuated in KO mice. (E) FcεRI expression on peritoneal mast cells (PMCs) is decreased by NATC2 deficiency. (F) FcγRIIB/RIII expression of PMCs is similar in WT and KO mice. (G) PMC FcεRI expression is induced by IgE to a similar extent in WT and KO mice. **P < .01; ***P < .001.

IgE-mediated PSA, PCA, and mast cell degranulation are attenuated in immunized NFATC2-deficient mice. (A) IgE-induced passive systemic anaphylaxis (PSA) is attenuated in NFATC2 KO mice. (B-C) Similarly, anti-DNP IgE-mediated passive cutaneous anaphylaxis (PCA) is attenuated in KO mice (B) and leads to fewer mast cells in the ear pinnae of mice (C). (D) IgE- but not IC-mediated ex vivo mast cell degranulation is attenuated in KO mice. (E) FcεRI expression on peritoneal mast cells (PMCs) is decreased by NATC2 deficiency. (F) FcγRIIB/RIII expression of PMCs is similar in WT and KO mice. (G) PMC FcεRI expression is induced by IgE to a similar extent in WT and KO mice. **P < .01; ***P < .001.

To further evaluate the effect of NFATC2 deficiency on in vivo mast cell anaphylaxis, we elicited FcεRI-mediated passive cutaneous anaphylaxis in naïve and ASNase-immunized WT and KO mice. Mice received intradermal ear injections of anti-DNP IgE antibody and were challenged the next day with DNP-HAS along with the vascular permeability tracer Evans blue to measure plasma extravasation associated with local cutaneous anaphylaxis (supplemental Figure 3B). Dye extravasation was similar in naïve WT and KO mice and was increased by immunization only in WT mice (Figure 4B). Consistent with the extravasation data, immunization increased the frequency of mast cells in the ear for WT but not NFATC2 KO mice (Figure 4C). This suggests that NFATC2 does not directly affect passive cutaneous anaphylaxis, but rather promotes a heightened mast cell response that exacerbates anaphylaxis. These data are consistent with immunization leading to heightened immune responses in WT but not NFATC2 KO mice.

To validate our in vivo anaphylaxis results, we evaluated ex vivo mast cell degranulation by measuring the release of granule-associated enzyme β-hexosaminidase, which is a hallmark of mast cell degranulation. Mast cells were derived from the peritoneal cavity of naïve or immunized WT or NFATC2-deficient mice, and anti-DNP IgE or anti-ASNase IgE antibodies could bind to their FcεRI. The PMCs were then incubated with DNP-HSA or ASNase to induce degranulation. ASNase-immunized, but not naïve, NFATC2-deficient PMCs had less DNP- and ASNase-mediated degranulation than WT PMCs (Figure 4D; supplemental Figure 3C). The degranulation induced by ASNase was FcεRI dependent, as shown by its blocking with anti-IgE mAb. Consistent with the results from our ex vivo basophil analysis (Figure 3D), NFATC2 deficiency was associated with reduced PMC FcεRI expression (Figure 4E), suggesting that the difference in the β-hexosaminidase release was likely due to less cell-associated antigen-specific IgE on the surface of NFATC2-deficient PMCs. In contrast, no difference was found for ASNase IC–induced, FcγR-dependent β-hexosaminidase release from the PMCs of naïve or immunized WT or KO mice (Figure 4D). Consistent with our PMC degranulation data, WT and KO PMCs expressed comparable levels of FcγRIIB/RIII (Figure 4F).

Our results indicate that much of the anaphylaxis protection mediated by NFATC2 deficiency is associated with decreased FcεRI expression (Figure 3D-E) and lower IgE antibody levels (Figure 1H-J), which may be due to a lower Th2 response that attenuates IgE secretion and thereby FcεRI expression.29 It has been previously described that IgE binding to FcεRI enhances mast cell FcεRI expression.30,31 To further confirm that the difference in FcεRI expression between the mice is due to differences in IgE levels, we induced FcεRI expression in naive WT and NFATC2-deficient mice by administering IV mouse IgE mAb or PBS daily for 3 days and measuring PMC (c-Kit+IgE+) FcεRI expression. We observed a two-fold induction of FcεRI relative to controls in both WT and KO mice (Figure 4G), indicating that there was no defect in FcεRI expression induction by IgE associated with the NFATC2 deficiency.

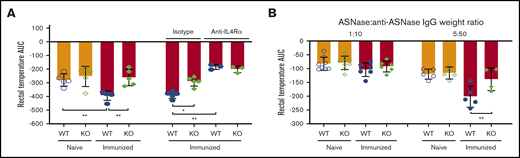

Th2 cytokines exacerbate ASNase-induced anaphylaxis

Our results are consistent with the possibility that the attenuation of anaphylaxis in NFATC2-deficient mice is partially due to decreased IL-4 responses, leading to diminished IgE antibody production. This, in turn, limits the immunization-induced increases in mast cell/basophil FcεRI expression. The combination of decreased mast cell/basophil FcεRI and decreased ASNase-specific IgE likely attenuates ASNase-induced basophil/mast cell degranulation by reducing cell-associated anti-ASNase IgE. However, it is also feasible that other mechanisms contribute to the difference in anaphylaxis between immunized WT and KO mice, such as an attenuation in the severity of anaphylaxis as a result of decreased IL-4 and/or IL-13 levels and their synergistic action with vasoactive mediators to increase vascular permeability.32,33 Consistent with this possibility, ASNase-immunized KO mice developed less severe shock than immunized WT mice challenged with histamine (supplemental Figure 4A-C; Figure 5A), whereas no difference in the severity of shock was detected between histamine-injected naïve WT and KO mice. Likewise, immunized NFATC2 KO mice developed less severe anaphylaxis relative to WT controls when directly challenged with ASNase ICs (Figure 5B; supplemental Figure 5A-B), although differences in the severity by genotype were dose dependent, indicating that both the levels of vasoactive mediators released upon degranulation and the differential cytokine levels are required to demonstrate exacerbated anaphylaxis in WT mice.

ASNase-induced anaphylaxis exacerbation is due to higher IL-4/IL-13 in WT mice after immunization. (A) ASNase-immunized mice received 3 mg of anti-mouse IL-4Rα (M1) or an isotype-matched control mAb, were challenged the next day with 2 mg of histamine IV, and evaluated for the development of hypothermia. NFATC2 deficiency protects against histamine-induced anaphylaxis exacerbation in immunized mice, and the difference in anaphylaxis between WT and KO mice is abolished after blocking IL-4Rα. (B) Immunized KO mice are protected from passive ASNase IC–mediated anaphylaxis relative to controls when prepared at 5 µg of ASNase and 50 µg of purified anti-ASNase IgG, but not at a fivefold lower dose. *P < .05; **P < .01.

ASNase-induced anaphylaxis exacerbation is due to higher IL-4/IL-13 in WT mice after immunization. (A) ASNase-immunized mice received 3 mg of anti-mouse IL-4Rα (M1) or an isotype-matched control mAb, were challenged the next day with 2 mg of histamine IV, and evaluated for the development of hypothermia. NFATC2 deficiency protects against histamine-induced anaphylaxis exacerbation in immunized mice, and the difference in anaphylaxis between WT and KO mice is abolished after blocking IL-4Rα. (B) Immunized KO mice are protected from passive ASNase IC–mediated anaphylaxis relative to controls when prepared at 5 µg of ASNase and 50 µg of purified anti-ASNase IgG, but not at a fivefold lower dose. *P < .05; **P < .01.

To confirm that the anaphylaxis exacerbation in immunized WT mice was due to higher IL-4/IL-13 levels, we blocked IL-4Rα in vivo using an anti–IL-4α mAb19 and challenged mice with histamine. We found that the severity of anaphylaxis in immunized WT mice was significantly reduced by the anti–IL-4α mAb relative to isotype control mice, supporting our hypothesis (supplemental Figure 4A; Figure 5A).

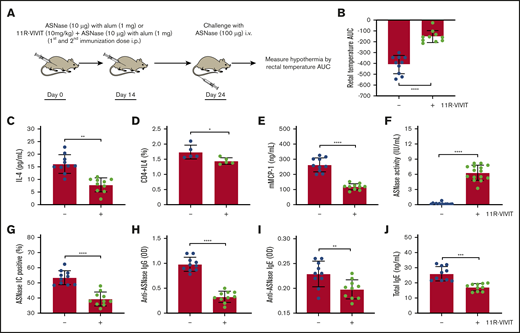

Pharmacological inhibition of NFAT protects mice from ASNase-induced antibody responses and ASNase hypersensitivity reactions

On the basis of our studies using NFATC2 KO mice, we hypothesized that pharmacological inhibition of NFAT would provide similar protection from Th2 immune responses and ASNase anaphylaxis. To test our hypothesis, we used the peptide NFAT inhibitor 11R-VIVIT, which selectively blocks calcineurin-mediated NFAT activation without affecting calcineurin phosphatase activity.34,35 11R-VIVIT was administered to WT mice concurrently with ASNase immunization (Figure 6A). Treatment with 11R-VIVIT did not significantly alter spleen weight (supplemental Figure 6A-C), as was observed for NFATC2 KO vs WT mice, suggesting that the effect of NFATC2 loss on the spleen requires chronic inhibition of the transcription factor, supporting previous studies demonstrating the safety of 11R-VIVIT.36 Furthermore, 11R-VIVIT significantly protected mice from ASNase hypersensitivity to an extent similar to that seen in NFATC2 KO mice (Figure 6B), attenuated plasma IL-4 levels (Figure 6C), and resulted in a decreased frequency of CD4+IL-4+ T cells (Figure 6D). Consistent with the protection from ASNase hypersensitivity and attenuated IL-4 response, 11R-VIVIT–treated mice had lower plasma mMCP-1 (Figure 6E), higher ASNase drug levels (Figure 6F), fewer ASNase ICs (Figure 6G), and lower anti-ASNase IgG/IgE and total IgE levels relative to controls (Figure 6H-J). Taken together, 11R-VIVIT suppressed the ASNase-induced Th2 response and fully protected mice from ASNase hypersensitivity, similar to our genetic NFATC2 inhibition studies.

Pharmacological inhibition of NFAT rescues ASNase-induced immune responses. (A) Schematic representation of ASNase immunization, 11R-VIVIT treatment, and the ASNase challenge protocol. (B) Immunized WT mice treated with 11R-VIVIT (10 mg/kg) are protected against developing hypothermia when challenged with ASNase. (C-D) 11R-VIVIT–treated mice have lower levels of IL-4 plasma levels and CD4+IL-4+ T-cell frequency. (E-J) Furthermore, 11R-VIVIT–treated mice had lower plasma mMCP-1 (E), higher ASNase drug levels (F), fewer detectable ASNase ICs (G), and lower anti-ASNase IgG/IgE and total IgE levels relative to controls (H-J). *P < .05; **P < .01; ****P < .0001.

Pharmacological inhibition of NFAT rescues ASNase-induced immune responses. (A) Schematic representation of ASNase immunization, 11R-VIVIT treatment, and the ASNase challenge protocol. (B) Immunized WT mice treated with 11R-VIVIT (10 mg/kg) are protected against developing hypothermia when challenged with ASNase. (C-D) 11R-VIVIT–treated mice have lower levels of IL-4 plasma levels and CD4+IL-4+ T-cell frequency. (E-J) Furthermore, 11R-VIVIT–treated mice had lower plasma mMCP-1 (E), higher ASNase drug levels (F), fewer detectable ASNase ICs (G), and lower anti-ASNase IgG/IgE and total IgE levels relative to controls (H-J). *P < .05; **P < .01; ****P < .0001.

Discussion

This study supports that the NFATC2 transcription factor is a key regulator of ASNase-induced anaphylaxis. ASNase is a chemotherapeutic agent used for treatment of pediatric leukemias, but the development of an immune response to this agent can lead to decreased systemic drug levels, anaphylaxis, and increased risk of leukemia relapse. Therefore, strategies that can mitigate this immunotoxicity are urgently needed to improve therapy.1-7 A recent clinical study led by our group identified by GWAS a higher risk of ASNase hypersensitivity among carriers of the NFATC2 rs6021191 variant, which leads to elevated expression of this transcription factor.8 Furthermore, our clinical analyses identified that Down syndrome ALL patients, who overexpress NFAT pathway inhibitors as a result of trisomy 21, are protected from the immune response to ASNase, suggesting that modulating NFATC2 protein levels has a corresponding effect on the risk of ASNase hypersensitivity in pediatric ALL patients.8 On the basis of our clinical studies, we hypothesized that inhibition of NFATC2 would protect from ASNase immune responses. Consistent with our GWAS, our current study demonstrates that genetic inhibition of NFATC2 in mice protects from ASNase-induced hypersensitivity (Figure 1B), attenuates anti-ASNase antibody responses (Figure 1F-J), rescues ASNase drug levels (Figure 1D), and leads to decreased mast cell degranulation (ie, mMCP-1; Figure 1C).

Our previous studies showed that hypersensitivity to ASNase can be mediated via both anti-ASNase IgG and/or IgE and the immunoglobulin receptors FcγRIII and FcεRI, respectively, where both Fc receptors are expressed in basophils and mast cells.28 Our murine model of ASNase hypersensitivity indicates that NFATC2 KO mice are protected from IgE/FcεRI-mediated hypersensitivity based on the severity and extent of hypothermia (Figure 1B), lower anti-ASNase IgE (Figure 1I-J), lower mMCP-1 (Figure 1C), and attenuated basophil activation (Figure 3F) relative to WT mice. Our findings indicate that much of the protection mediated by the loss of NFATC2 is due to attenuated Th2 responses, leading to decreased total IgE antibody secretion (Figure 1H-J) and thereby lower FcεRI expression.29 Consistent with attenuated IgE leading to decreased FcεRI expression30,31 rather than NFATC2 deficiency having a direct effect on FcεRI, similar FcεRI expression was stimulated in naïve KO and WT mice receiving murine IgE (Figure 4G). Using passive models of anaphylaxis, we found that mast cell function was likely not affected by the loss of NFACT2, because there was no difference in DNP-induced anaphylaxis among naïve WT and NFATC2 KO mice (Figure 4A-B,D), which is consistent with previous studies.37,38 Rather, after immunization, our passive models of anaphylaxis recapitulate the results of our model of ASNase-induced hypersensitivity, demonstrating lower FcεRI expression (Figure 4E) and attenuated mast cell degranulation (Figure 4D).

Previously, we demonstrated that IgG-mediated anaphylaxis requires ASNase-specific IgG antibodies to form ASNase ICs, which can thereafter bind to the FcγRIII of immune cells and trigger IgG-mediated hypersensitivity. In our current study, we observed that NFATC2-deficient mice were protected from IgG-mediated anaphylaxis because of decreased levels of anti-ASNase IgG, fewer ASNase ICs upon drug reexposure (Figure 1E-F), and, therefore, attenuated FcγRIII-mediated basophil (Figure 3D) and mast cell degranulation (Figure 4D). However, the binding of preformed ASNase ICs to the naïve basophils of WT and KO mice was equivalent but increased after immunization (Figure 3C), consistent with the increased basophil FcγRIII expression after ASNase immunization (Figure 3E). Nevertheless, unlike FcεRI expression, there was no differential FcγRIII expression between WT and NFATC2 KO mice before or after ASNase immunization (Figure 3E; Figure 4F). On the basis of these results, no difference in IgG/FcγRIII anaphylaxis between WT and NFATC2 KO mice would be expected solely as a result of mast cell or basophil degranulation.

Interestingly, our model of ASNase-mediated IgG/FcγRIII anaphylaxis showed that immunized NFATC2 KO mice had less severe shock than WT mice (Figure 5B), indicating that other factors aside from IC binding to FcγRIII contribute to the severity of hypersensitivity. Past studies have demonstrated that Th2 cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-13 can exacerbate IgE/IgG-mediated hypersensitivity via the IL-4R of vascular endothelial cells.32 Consistent with the effect of Th2 cytokines on ASNase-induced hypersensitivity, we also found that immunized WT mice had more severe anaphylaxis than NFATC2 KO mice when challenged with histamine (Figure 5A). Furthermore, we demonstrated that the severity of histamine-induced anaphylaxis in immunized WT mice could be attenuated by an anti–IL-4α mAb,19 confirming that NFATC2 KO mice are protected from exacerbated ASNase-induced anaphylaxis via an attenuated Th2 response (supplemental Figure 4A; Figure 5A). Altogether, our studies indicate that both the levels of vasoactive mediators released upon degranulation and differential cytokine levels are required to demonstrate aggravated anaphylaxis in WT mice.

Several investigations using NFATC2-deficient mice have attempted to clarify the role of this transcription factor in the regulation of CD4+ Th1/Th2 differentiation.20,39-43 The conclusions from these findings are inconsistent, and several suggestions have been proposed to explain the lack of agreement. Our results are remarkable, in contrast to the original studies performed using similar and genetically identical mice, which have indicated increased production of IL-4 and other Th2 cytokines in NFATC2 KO mice. It is unlikely that the differences are due to antigen variation, because our murine model and the models used by the Rao laboratory15,20 both lead to Th2 responses. It is, however, possible (but unlikely because of the low immunization dose used) that asparagine depletion by ASNase has a direct effect on antigen presentation after endocytosis, but no data are currently available to investigate this possibility. Rather, it is more likely that other factors, such as diet, husbandry, or the rederivation process, may lead to gut microbiota and epigenetics changes that affect the binding of NFATC2 to the promoter of Th2 or Th1 cytokine genes.44,45

Several studies support that NFATC2 deficiency impairs the expression of NFATC2 target genes14,41,46 and provides protection from various immune-mediated diseases in mice.16 Karwot et al17 demonstrated that NFATC2 KO mice were protected from allergen-induced experimental asthma, where the protection was associated with an increase in CD4+ Tregs and suppression of the NFATC2 target gene IL-2. Consistent with this study, ASNase-immunized NFATC2 KO mice had an increased frequency of splenic CD4+ Tregs (Figure 2F) and elevated plasma levels of the Treg cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β relative to controls (Figure 2G-H). Furthermore, we observed a decrease in Th2 cells and their associated cytokines in ASNase-immunized NFATC2 KO mice (Figure 2C-E). Therefore, there may be multiple mechanisms by which NFATC2 deficiency attenuates Th2 responses to ASNase-induced immune responses. In agreement with our results and previous studies, pretreatment of WT mice with the NFAT inhibitor 11R-VIVIT protected them from ASNase-induced anaphylaxis and attenuated Th2 responses after immunization (Figure 6B-D). However, 11R-VIVIT can also inhibit other NFAT family transcription factors; therefore, it is possible that the inhibition of other NFATs also contributed to the pharmacological protection observed.

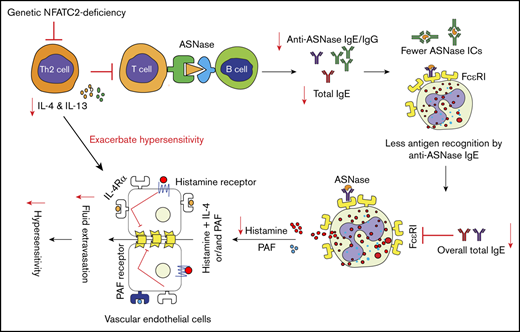

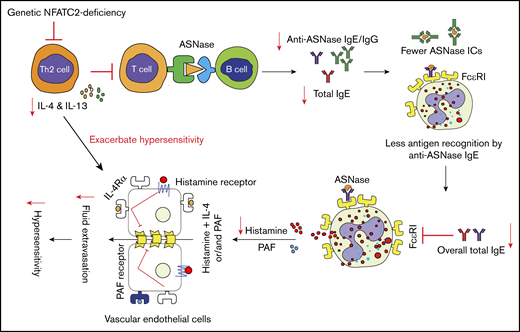

In summary, in the present study, we provide evidence that NFATC2 plays a critical role in the regulation of Th2 responses and ASNase hypersensitivity. To our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating that genetic or pharmacological inhibition of NFATC2 can protect against systemic hypersensitivity by attenuating Th2 cytokine responses. Taken together, the results of our study indicate that NFATC2-deficient mice are protected against anaphylaxis by attenuation of the Th2 immune response after antigen exposure, which limits the anaphylaxis-promoting responses of B cells, basophils, mast cells, and vascular endothelial cells (Figure 7). Conclusively, our results suggest that NFATC2 may serve as a therapeutic target to mitigate unwanted immune/hypersensitivity responses against ASNase and possibly other agents.

Schematic representation of NFATC2 contributions to the severity of anaphylaxis. NFATC2 deficiency leads to an attenuated Th2 response, resulting in less secretion of IL-4 and other Th2 cytokines. This attenuated cytokine response leads to lower antibody levels, and the decrease in total IgE reduces the FcεRI expression on basophils and mast cells. The decreased FcεRI expression and lower plasma IgE level lead to less cell-associated IgE and decreased basophil/mast cell degranulation upon antigen exposure. Similarly, the decrease in anti-ASNase IgG antibodies results in fewer ASNase ICs upon antigen exposure and decreased IgG/FcγRIII-mediated anaphylaxis. Furthermore, the decrease in IL-4 secretion caused by NFATC2 deficiency limits the severity of histamine-induced anaphylaxis. PAF, platelet-activating factor.

Schematic representation of NFATC2 contributions to the severity of anaphylaxis. NFATC2 deficiency leads to an attenuated Th2 response, resulting in less secretion of IL-4 and other Th2 cytokines. This attenuated cytokine response leads to lower antibody levels, and the decrease in total IgE reduces the FcεRI expression on basophils and mast cells. The decreased FcεRI expression and lower plasma IgE level lead to less cell-associated IgE and decreased basophil/mast cell degranulation upon antigen exposure. Similarly, the decrease in anti-ASNase IgG antibodies results in fewer ASNase ICs upon antigen exposure and decreased IgG/FcγRIII-mediated anaphylaxis. Furthermore, the decrease in IL-4 secretion caused by NFATC2 deficiency limits the severity of histamine-induced anaphylaxis. PAF, platelet-activating factor.

For data sharing requests, send e-mails to the corresponding author, Christian A. Fernandez (chf63@pitt.edu).

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by the University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy and National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute grant RO1 CA216815.

Authorship

Contribution: S.R., F.D.F., and C.A.F. designed experiments and wrote the manuscript; and S.R. and M.R. performed all experiments.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Christian A. Fernandez, Center for Pharmacogenetics, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, School of Pharmacy, University of Pittsburgh, 335 Sutherland Dr, Pittsburgh, PA 15261; e-mail: chf63@pitt.edu.

References

Author notes

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.