Key Points

Morphine stimulates retinal endothelial cell proliferation via MOR by transactivating VEGFR2 and an IL-6–dependent STAT3 pathway.

Chronic morphine treatment–promoted retinal neovascularization may contribute to retinopathy in patients with SCD.

Abstract

Neovascularizing retinopathy is a significant complication of sickle cell disease (SCD), occurring more frequently in HbSC than HbSS disease. This risk difference is concordant with a divergence of angiogenesis risk, as identified by levels of pro- vs anti-angiogenic factors in the sickle patient’s blood. Because our prior studies documented that morphine promotes angiogenesis in both malignancy and wound healing, we tested whether chronic opioid treatment would promote retinopathy in NY1DD sickle transgenic mice. After 10 to 15 months of treatment, sickle mice treated with morphine developed neovascularizing retinopathy to a far greater extent than either of the controls (sickle mice treated with saline and wild-type mice treated identically with morphine). Our dissection of the mechanistic linkage between morphine and retinopathy revealed a complex interplay among morphine engagement with its μ opioid receptor (MOR) on retinal endothelial cells (RECs); morphine-induced production of tumor necrosis factor α and interleukin-6 (IL-6), causing increased expression of both MOR and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) on RECs; morphine/MOR engagement transactivating VEGFR2; and convergence of MOR, VEGFR2, and IL-6 activation on JAK/STAT3-dependent REC proliferation and angiogenesis. In the NY1DD mice, the result was increased angiogenesis, seen as neovascularizing retinopathy, similar to the retinal pathology occurring in humans with SCD. Therefore, we conclude that chronic opioid exposure, superimposed on the already angiogenic sickle milieu, might enhance risk for retinopathy. These results provide an additional reason for development and application of opioid alternatives for pain control in SCD.

Introduction

Neovascularizing retinopathy involving vision loss is a severe complication of sickle cell disease (SCD).1-4 Although more prevalent in HbSC disease (∼43%), it also occurs in sickle cell anemia (∼14%).5 Sickle retinopathy fundamentally stems from occlusion of the peripheral retinal vasculature, leading to ischemia-reperfusion injury, inflammation, and angiogenesis (neovascularization). However, risk is likely established by other facets of the disease as well. Consistent with the HbSS vs HbSC prevalence difference, our earlier studies found that plasma vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) level (a strongly proangiogenic influence) is elevated in both HbSS and HbSC patients,6 but plasma thrombospondin level (a strongly counterveiling influence)7 is elevated only in HbSS patients.8 Levels of other proangiogenic factors are elevated in SCD as well.9,10 Thus, the pro- vs anti-angiogenic balance in blood is tipped in favor of neovascularizing retinopathy in some SCD patients.

In this preexisting proangiogenic context, it may be concerning that morphine and its congeners are used frequently, sometimes chronically, and possibly lifelong for pain mitigation in SCD. Our prior work using rodent models of cancer and wound healing documented that morphine administration induces substantial angiogenesis.11-16 This occurs because in addition to producing analgesia signaling via μ opioid receptor (MOR), morphine transactivates several receptor tyrosine kinases,17-21 such as VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2) and platelet-derived growth factor receptor β,12,22,23 thereby promoting cell-cycle progression and endothelial growth and survival.

VEGF itself is a key factor in retinal neovascularization and retinal vascular permeability generally,24 which supports that chronic morphine exposure might enhance development of retinal neovascularization and retinopathy. In the present study of chronic morphine treatment of sickle transgenic mice, we observed significant drug-induced angiogenesis in the form of retinal neovascularization. This not only provides new insight into the risk of retinopathy in SCD but also argues for development of opioid-independent treatment regimens for this disease.

We here used NY1DD sickle transgenic mice, which spontaneously exhibit some evidence of vascular changes in the retina and choroid,25 although they have a relatively mild sickle phenotype and do not show mechanical or thermal hyperalgesia.26 We considered using more severe HbSS-BERK mice, characterized for understanding sickle pathobiology and pain by our group. However, HbSS-BERK mice develop retinal degeneration by a homozygous rd1 mutation early in age, independent of sickle hemoglobin.27 Therefore, HbSS-BERK mice are not suitable to examine retinopathy. NY1DD mice seemed to be appropriate because of slower retinal vascular changes, which are helpful in examining whether opioids exaggerate the retinal vascular changes over time. Although the effect of opioids on pain cannot be analyzed in NY1DD mice, this model seems to be suitable for examining sickle retinopathy.

Methods

Methods are described in greater detail in the supplemental Material.

Animals

Mice were bred and maintained under controlled environmental conditions (12-hour light-to-dark cycle at 23°C) in our Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care–accredited facility and provided with standard laboratory food and water ad libitum. Genotypes were confirmed by hemoglobin isoelectric focusing.28 C57BL/6 mice with the same genetic background were used as wild-type (WT) controls. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Minnesota.

Drug treatment of mice

Starting at 9 months of age, mice were subcutaneously injected with pharmacological-grade morphine (Baxter Esilerderle Mfd. Healthcare Corporation) and/or naloxone (Hospira Inc., Lake Forest, IL). Duration was for 6, 10, or 15 months, and dose schedule was twice daily for 5 days per week as follows: morphine at 0.71 mg/kg per day (equivalent to 50 mg per 70 kg per day for a human) for 2 weeks, followed by 0.14-mg (equivalent to 10 mg for a human) increments every 2 weeks. Another group of mice received equimolar naloxone, an opioid receptor antagonist.

Imaging and scoring of retinal neovascularization

We visualized retinal vessels by detecting their ADPase activity. To provide numerical representations of angiogenesis, we digitally skeletonized vessels to measure length, nodes (branch points), and end points (number) as described previously.12,29

Mouse REC isolation and culture

Primary cell cultures of retinal endothelial cells (RECs) from 3-month-old WT or NY1DD mice were established and identified by fluorescence-activated cell sorting as 99% positive for endothelial cell markers CD31 and VEGFR2 as previously described.12,22

Radioligand binding to REC membranes

Details of cell membrane preparation from WT and NY1DD mice and the saturation or competitive binding of [3H]diprenorphine to REC membranes are described in the supplemental Material.

Cell proliferation and apoptosis

Cell proliferation was measured using 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (colorimetric) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay assay (Roche Diagnostics) as described previously.12,22 Apoptosis was determined as cytoplasmic histone-associated DNA fragments (mono- and oligonucleosomes) using Cell Death Detection ELISA Kit (Roche Diagnostics).7

Receptor expression

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction for gene expression in total RNA was performed. For evaluation of STAT3 signaling on receptor expression, RECs were incubated with 10 μM of morphine or interleukin-6 (IL-6; 1 ng/mL; R&D Systems) with or without STAT3 inhibitor peptide (PpYLKTK-mts, 0.5 mM; Calbiochem)

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was performed at least in triplicate and repeated at least 3 times. All data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analyses were performed using the PRISM program (version 6.0; GraphPad Software, Inc.). Comparison between conditions were made with an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test. Comparisons of multiple treatments were made by 1-way analysis of variance with Dunett’s multiple comparisons. The level for statistical significance was set at P < .05.

Results

Morphine-induced retinal neovascularization in sickle mice

It is already known that older NY1DD mice mimic several characteristics of human retinopathy in SCD, but only 30% show bilateral and mild chorioretinopathy between age 15 to 30 months.25 In the present study, we treated 9-month-old mice, either normal WT or NY1DD sickle, with saline (control) or morphine for 6, 10, or 15 months. After 6 months of either saline or morphine, NY1DD mice retained normal retinal vascular architecture, without evidence for neovascularization (data not shown). However, longer treatments of 10 and 15 months promoted neovascularization in the retinae of NY1DD but not WT mice (Figure 1; supplemental Figure 1). Retinae were examined first by microscopic evaluation of ADPase-stained, embedded flat mounts and then by digital skeletonization to enable quantitative comparisons.

Morphine (MS) induces retinal neovascularization in sickle mice, which is attenuated by coadministration of opioid antagonist naloxone (NAL). (A-D) C57BL/6 mice (WT) or NY1DD sickle mice treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or increasing doses of MS for 15 months. (E-G) NY1DD sickle mice treated with MS alone, MS with NAL, or PBS with saline or NAL for 10 months. (A) Representative images of isolated retinae with ADPase staining of blood vessels (magnification ×400). NY1DD sickle mice treated with PBS had typical hairpin loops in the periphery (green arrows) and few arteriovenous (AV) anastamoses (magenta arrows). MS-treated NY1DD sickle mice had more AV anastamoses (blue arrows). The results of statistical analysis of nodes showing vessel branching (B,E), total length of blood vessels (C,F), and total number of blood vessels in retinae are shown (D,G). N = 3 mice per treatment. All values are mean ± SEM, and significance was determined by 1-way analysis of variance, Dunnet’s multiple comparisons.

Morphine (MS) induces retinal neovascularization in sickle mice, which is attenuated by coadministration of opioid antagonist naloxone (NAL). (A-D) C57BL/6 mice (WT) or NY1DD sickle mice treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or increasing doses of MS for 15 months. (E-G) NY1DD sickle mice treated with MS alone, MS with NAL, or PBS with saline or NAL for 10 months. (A) Representative images of isolated retinae with ADPase staining of blood vessels (magnification ×400). NY1DD sickle mice treated with PBS had typical hairpin loops in the periphery (green arrows) and few arteriovenous (AV) anastamoses (magenta arrows). MS-treated NY1DD sickle mice had more AV anastamoses (blue arrows). The results of statistical analysis of nodes showing vessel branching (B,E), total length of blood vessels (C,F), and total number of blood vessels in retinae are shown (D,G). N = 3 mice per treatment. All values are mean ± SEM, and significance was determined by 1-way analysis of variance, Dunnet’s multiple comparisons.

Microscopic evaluation

Retinae from WT mice treated with saline for 15 months retained the normal organized vascular pattern with clearly defined alternating presence of arteries and veins. At the same time point, the saline-treated NY1DD mice retained typical hairpin loops in the periphery (Figure 1A green arrows) but with some abnormal AV anastamoses (Figure 1A magenta arrows), similar to those previously observed by Lutty et al.25,30

In striking contrast, retinae from morphine-treated NY1DD mice exhibited neovascular buds, seen as nodes on the vessels throughout the retina, suggesting that morphine stimulates a highly proliferative response in the retinal vasculature. Indeed, they revealed more apparent AV anastomoses (Figure 1A blue arrows), and the normal hairpin loops were absent, indicating retinal neovascularization. Indeed, their retinae exhibited abnormal vascular architecture with a very dense network of blood vessels, particularly with the central retina exhibiting overlapping vessels and abnormal patterns of vascularization (Figure 1A). Arteries and veins were indistinguishable; it is likely that increased vascularity arose from both.31 The retina at the ora serata, which normally has a sparse vasculature, had a somewhat denser vasculature within which abnormal AV anastomoses were interspersed. Although we did not see preretinal neovascularization in morphine-treated mice, capillary-free zones around arteries were greatly reduced.

Differences in patterns of branching and density of the vessels can be better appreciated in the skeletonized images (supplemental Figure 2).

Digital skeletonization

We deployed this approach to accurately convert retinal images to a form that enhances comparative, quantitative confirmation of angiogenesis robustness. Consistent with the described changes observed by microscope, this documented that morphine-treated NY1DD mice had indeed developed abnormal retinal neovascularization after both 10 and 15 months of treatment (supplemental Figure 1). Specifically, morphine induced significant increases in the total number of blood vessels, number of nodes showing the promotion of vessel branching, and total length of blood vessels (including both main trunks and branches; Figure 1B-D). Coadministration of naloxone with morphine significantly decreased each of these quantitative parameters (Figure 1E-G).

Upregulated MOR expression in sickle mouse RECs

It seemed likely to us that the neovascularizing retinopathy evoked by morphine in NY1DD sickle mice, but not WT controls, indicated that the high-affinity receptor of morphine, MOR, is upregulated in the RECs of sickle mice. However, the possibility that morphine may be acting via other opioid receptors still persists. Therefore, we performed pharmacological binding studies to analyze the binding sites for MOR and other opioid receptors in RECs from sickle and WT mice. Saturation binding assays using the opioid antagonist [3H]diprenorphine identified specific, saturable [3H]diprenorphine-binding to REC membrane preparations from WT and NY1DD mice. Scatchard analysis comparison for WT vs NY1DD RECs identified nearly identical opioid binding affinity (Kd = 8.61 ± 4.87 vs 8.99 ± 1.34 nM, respectively) but strikingly divergent maximal binding values (Bmax = 452.5 ± 85.13 vs 1233 ± 62.07 fmol/mg of protein, respectively; P < .05; Figure 2A-B; Table 1).

MOR is increased in binding affinity and number in retinal endothelial cells of sickle mice. Saturation binding curves (A) and Scatchard plots (B) for binding of [3H]diprenorphine to membranes from RECs isolated from WT and NY1DD mice. (C-D) Competitive binding of opioid receptor ligands with [3H]diprenorphine in membranes derived from RECs of WT (C) and NY1DD mice (D). MOR-specific agonists morphine, D-Ala(2), N-Me-Phe(4), Gly(5)-ol-enkephalin (DAMGO), and etorphine effectively competed for [3H]diprenorphine binding, reaching 0% of the specific binding, whereas {[D-Pen (2, 5)]-Enkephalin} (DPDPE; δ opioid receptor agonist) and U50488H (κ opioid receptor agonist) could not effectively compete for the specifically bound [3H]diprenorphine. In all cases, 10 μM of naloxone was used to determine nonspecific binding. Results represent mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate. (E) MOR expression is increased in retinae and RECs of sickle mice. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction was performed for MOR on total RNA on retinae or RECs isolated from naïve WT and NY1DD mice. Representative image for total RNA from retinae or RECs from 3 mice per group. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

MOR is increased in binding affinity and number in retinal endothelial cells of sickle mice. Saturation binding curves (A) and Scatchard plots (B) for binding of [3H]diprenorphine to membranes from RECs isolated from WT and NY1DD mice. (C-D) Competitive binding of opioid receptor ligands with [3H]diprenorphine in membranes derived from RECs of WT (C) and NY1DD mice (D). MOR-specific agonists morphine, D-Ala(2), N-Me-Phe(4), Gly(5)-ol-enkephalin (DAMGO), and etorphine effectively competed for [3H]diprenorphine binding, reaching 0% of the specific binding, whereas {[D-Pen (2, 5)]-Enkephalin} (DPDPE; δ opioid receptor agonist) and U50488H (κ opioid receptor agonist) could not effectively compete for the specifically bound [3H]diprenorphine. In all cases, 10 μM of naloxone was used to determine nonspecific binding. Results represent mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate. (E) MOR expression is increased in retinae and RECs of sickle mice. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction was performed for MOR on total RNA on retinae or RECs isolated from naïve WT and NY1DD mice. Representative image for total RNA from retinae or RECs from 3 mice per group. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Binding characteristics of [3H]diprenorphine for WT and NY1DD RECs

| REC membrane . | Mean ± SEM . | |

|---|---|---|

| Bmax, fmol/mg . | Kd, nM . | |

| WT | 452.5 ± 85.13 | 8.61 ± 4.87 |

| NY1DD | 1233 ± 62.07 | 8.99 ± 1.34 |

| REC membrane . | Mean ± SEM . | |

|---|---|---|

| Bmax, fmol/mg . | Kd, nM . | |

| WT | 452.5 ± 85.13 | 8.61 ± 4.87 |

| NY1DD | 1233 ± 62.07 | 8.99 ± 1.34 |

We confirmed that MOR is the dominant opioid receptor subtype responsible for morphine binding to RECs by performing competition binding assays using agonists selective for μ, δ, or κ opioid receptors on RECs (Figure 2C-D); these results are summarized in Table 2. (Greater detail can be found in the supplemental Material.) Correspondingly, the RECs and whole retinae from NY1DD mice revealed abnormally high messenger RNA expression of MOR (Figure 2E).

Ki values for opioid ligand inhibition of [3H]diprenorphine binding to WT and NY1DD REC membranes

| Ligand . | Mean ± SEM . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT . | NY1DD . | |||

| Ki, nM . | Displacement, %* . | Ki, nM . | Displacement, %* . | |

| Morphine | 111 ± 11.36 | 71.69 ± 2.54 | 42.33 ± 10.17 | 82.84 ± 3.87 |

| DAMGO | 86.37 ± 10.84 | 82.05 ± 2.61 | 62.83 ± 12.56 | 81.98 ± 3.33 |

| Etorphine | 8.78 ± 0.46 | 83.25 ± 3.29 | 1.74 ± 0.54 | 90.39 ± 3.37 |

| DPDPE | 2214 ± 205.5 | 12.21 ± 4.98 | 2808 ± 431.9 | 8.36 ± 3.18 |

| U50488H | 535.55 ± 6.56 | 6.35 ± 0.62 | 320.3 ± 70.76 | 10.48 ± 4.19 |

| Ligand . | Mean ± SEM . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT . | NY1DD . | |||

| Ki, nM . | Displacement, %* . | Ki, nM . | Displacement, %* . | |

| Morphine | 111 ± 11.36 | 71.69 ± 2.54 | 42.33 ± 10.17 | 82.84 ± 3.87 |

| DAMGO | 86.37 ± 10.84 | 82.05 ± 2.61 | 62.83 ± 12.56 | 81.98 ± 3.33 |

| Etorphine | 8.78 ± 0.46 | 83.25 ± 3.29 | 1.74 ± 0.54 | 90.39 ± 3.37 |

| DPDPE | 2214 ± 205.5 | 12.21 ± 4.98 | 2808 ± 431.9 | 8.36 ± 3.18 |

| U50488H | 535.55 ± 6.56 | 6.35 ± 0.62 | 320.3 ± 70.76 | 10.48 ± 4.19 |

From 3 experiments performed in triplicate.

Percentage of displacement of [3H]diprenorphine. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 10 μM of naloxone.

Thus, these data identify abnormally increased MOR expression in NY1DD sickle RECs, accompanied by a significantly higher number of MOR binding sites in NY1DD RECs. This could well explain the abnormal robustness of the angiogenesis response evinced by the sickle mice given morphine. We therefore examined this further.

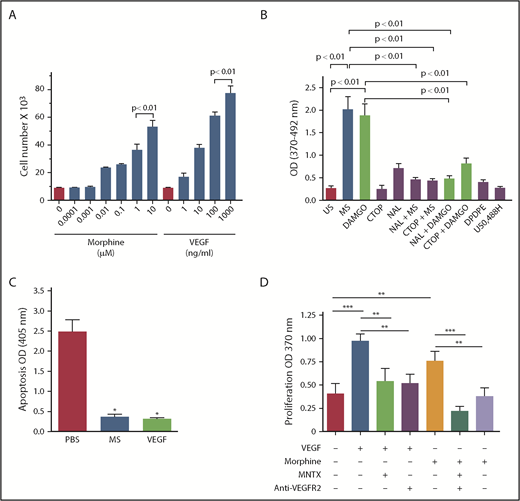

Morphine stimulates proliferation of sickle mouse RECs via MOR

Morphine exerts growth-promoting effects via angiogenic signaling in a variety of endothelial cell types, including human dermal microvascular endothelial cells, human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells, and mouse RECs.12,22,23 Therefore, we examined whether morphine induces REC proliferation in a dose-dependent manner, similar to the effect of VEGF.22 Studying mouse RECs, we found that both morphine and VEGF stimulated REC proliferation significantly at the low dose of 10 nM and 1 ng/mL, respectively (P < .01 vs 0 concentration for both; Figure 3A). Like morphine, the MOR-specific agonist DAMGO also stimulated REC proliferation, suggesting that MOR contributes to REC proliferation (Figure 3B). Complementary to REC proliferation, morphine and VEGF diminished apoptosis by ∼90% (P < .0005 vs phosphate-buffered saline; Figure 3C). This shows that, like VEGF, morphine stimulates proproliferative and survival-promoting signaling in both WT and NY1DD RECs.

Morphine (MS) and VEGF promote proliferation and survival signaling in RECs of sickle mice, and MS-induced proliferation is dependent on MOR. (A) RECs from NY1DD sickle mice show concentration-dependent increase in proliferation by MS and VEGF. (B) MS (1 μM) and MOR-selective agonist DAMGO (1 μM) stimulated proliferation of RECs from NY1DD sickle mice, which was inhibited by nonselective antagonist naloxone (NAL; 1 μM) and MOR-selective antagonist CTOP (1 μM). Specific antagonists for opioid receptors δ (DPDPE; 1 μM) and κ (U50488H; 1 μM) had no effect on proliferation. N = 3 mice per treatment. All values are mean ± SEM, and significance (P < .01) was determined by 1-way analysis of variance, Dunnet’s multiple comparisons. (C) MS (10 μM) and VEGF164 (100 ng/mL) promote survival signaling in NY1DD RECs. Results represent mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate. (D) N = 5 to 8 independent experiments. *P < .0005 vs phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was determined by an unpaired 2-tailed t test, **P < .05 and ***P < .01 1-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons.

Morphine (MS) and VEGF promote proliferation and survival signaling in RECs of sickle mice, and MS-induced proliferation is dependent on MOR. (A) RECs from NY1DD sickle mice show concentration-dependent increase in proliferation by MS and VEGF. (B) MS (1 μM) and MOR-selective agonist DAMGO (1 μM) stimulated proliferation of RECs from NY1DD sickle mice, which was inhibited by nonselective antagonist naloxone (NAL; 1 μM) and MOR-selective antagonist CTOP (1 μM). Specific antagonists for opioid receptors δ (DPDPE; 1 μM) and κ (U50488H; 1 μM) had no effect on proliferation. N = 3 mice per treatment. All values are mean ± SEM, and significance (P < .01) was determined by 1-way analysis of variance, Dunnet’s multiple comparisons. (C) MS (10 μM) and VEGF164 (100 ng/mL) promote survival signaling in NY1DD RECs. Results represent mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate. (D) N = 5 to 8 independent experiments. *P < .0005 vs phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was determined by an unpaired 2-tailed t test, **P < .05 and ***P < .01 1-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons.

Morphine- and DAMGO-induced proliferation was significantly inhibited by CTOP, a MOR-specific antagonist (Figure 3B), as well as by MNTX, which has relatively higher affinity for MOR compared with other opioid receptors (Figure 3D). In direct parallel to the measures of opioid binding to RECs described in the previous paragraph, this set of studies confirmed that the opioid-stimulated proliferation of RECs requires MOR activation (Figure 3B,D). Morphine-induced proliferation was also inhibited by blocking antibodies to VEGFR2 (Figure 3D), validating previous findings that morphine/MOR interaction transactivates signaling by VEGFR.22,23

In aggregate, these detailed studies confirm that opioid binding to RECs and resulting proliferative REC response (that predicts consequent angiogenesis) likely result from the abnormally increased number of morphine binding sites, in the form MOR, that are found on RECs from the NY1DD sickle mice.

Increased IL-6 in SCD contributes to upregulation of MOR in RECs

Expression of opioid receptors including MOR is upregulated by proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα).17,32-36 Additionally, chronic morphine treatment leads to an increase in IL-6 in wounds.37 Similar to earlier observations made by Belcher et al38 in 2003, we found NY1DD mice at baseline to have elevated levels of IL-6 and TNFα (Figure 4). Notably, morphine-treated NY1DD mice exhibited dramatic increases: 4.8-fold for serum IL-6 and 35-fold for serum TNFα (P < .01 vs saline-treated NY1DD mice). Furthermore, in response to morphine stimulation in vitro, NY1DD RECs released approximately twofold more IL-6 and fivefold more TNFα compared with WT RECs (P < .01; Figure 4). Finally, RECs from NY1DD mice, compared with WT RECs, exhibited far greater expression of MOR in response to stimulation with morphine or IL-6 (Figure 5). For each stimulus, this response was abrogated by a STAT3 inhibitor peptide (PpYLKTK-mts; Figure 5).

Morphine (MS) increases IL-6 and TNFα levels in serum and their secretion from RECs of sickle mice. Proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 (A-B) and TNFα (C-D) increased in serum of NY1DD sickle mice after MS treatment for 15 months (A,C) or conditioned medium from NY sickle RECs after MS treatment for 48 hours (B,D). All values are mean ± SEM for 3 mice per group or 3 independent experiments with RECs performed in triplicate. Significance was determined by 1-way analysis of variance, Dunnet’s multiple comparisons.

Morphine (MS) increases IL-6 and TNFα levels in serum and their secretion from RECs of sickle mice. Proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 (A-B) and TNFα (C-D) increased in serum of NY1DD sickle mice after MS treatment for 15 months (A,C) or conditioned medium from NY sickle RECs after MS treatment for 48 hours (B,D). All values are mean ± SEM for 3 mice per group or 3 independent experiments with RECs performed in triplicate. Significance was determined by 1-way analysis of variance, Dunnet’s multiple comparisons.

Morphine (MS) stimulates MOR and Flk1 gene expression by a STAT3-mediated mechanism. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction was performed for MOR and FLK-1/KDR (VEGFR2) on total RNA from RECs from WT and NY1DD sickle mice incubated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 1 μM of MS, or 1 ng/mL of IL-6 in the absence or presence of 0.5 mM of STAT3 inhibitor peptide (STAT3-I) for 48 hours. Representative density images are shown. All graph values are mean ± SEM for 3 independent experiments with RECs performed in triplicate. Significance was determined by 1-way analysis of variance, Dunnet’s multiple comparisons. *P < .0001 vs PBS of matching mouse/messenger RNA, **P < .01, ***P < .05, and ****P < .001 for matching treatment vs treatment + STAT3-I.

Morphine (MS) stimulates MOR and Flk1 gene expression by a STAT3-mediated mechanism. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction was performed for MOR and FLK-1/KDR (VEGFR2) on total RNA from RECs from WT and NY1DD sickle mice incubated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 1 μM of MS, or 1 ng/mL of IL-6 in the absence or presence of 0.5 mM of STAT3 inhibitor peptide (STAT3-I) for 48 hours. Representative density images are shown. All graph values are mean ± SEM for 3 independent experiments with RECs performed in triplicate. Significance was determined by 1-way analysis of variance, Dunnet’s multiple comparisons. *P < .0001 vs PBS of matching mouse/messenger RNA, **P < .01, ***P < .05, and ****P < .001 for matching treatment vs treatment + STAT3-I.

Therefore, data indicate that the already elevated IL-6 in NY1DD mice at baseline is further elevated when morphine is administered. In combination, these data suggest that increased IL-6 may be responsible for upregulated MOR expression in the retinae and RECs of NY1DD mice and occurs via STAT3 signaling pathway.

Even with these data, there remains 1 ambiguity. VEGF/VEGFR2 engagement is a key inducer of retinal angiogenesis,39,40 and our previous studies documented that morphine/MOR engagement transactivates VEGR2.22 Moreover, VEGF/VEGFR2,41 IL-6,42 and morphine/MOR43,44 all initiate the same STAT3-dependent, growth-promoting signaling pathway, which is also involved in the expression of VEGFR2 and MOR. Hence, we probed this further and found that exposure of NY1DD RECs to either morphine or IL-6 increased their expression of Flk1/VEGFR2 (by fivefold and threefold, respectively; Figure 5). These Flk1/VEGFR2 inductions were completely abrogated by a STAT3 inhibitor.

Discussion

This study was prompted by 2 well-known aspects of SCD. First, proliferative (neovascularizing) sickle retinopathy is not rare and can cause vision loss, a tragic complication.5,45,46 Second, sickle patients may be exposed to opioids recurrently or chronically, even from an early age. Because retinal neovascularization is caused by abnormal angiogenesis, we hypothesized that there could be a link between retinopathy and opioid exposure. Indeed, the basis for this link had already been established by our earlier studies, identifying morphine-driven angiogenesis in malignancy11,12,14 and wound healing13,15,16 (examples of this process being both harmful vs beneficial, respectively).

Unfortunately, the studies reported here indicate that our hypothesis was correct. The essential evidence is that sickle transgenic mice exposed chronically to morphine develop a rather dramatic degree of retinopathy of the neovascularizing type. Retinal changes were far less significant in both types of control mice: WT mice identically exposed to morphine and NY1DD mice chronically treated with saline only. The rest of the experiments described here were performed to dissect the specific endothelial biology linking morphine to retinal angiogenesis and to explain why the NY1DD sickle mice exhibited such heightened susceptibility to morphine, as compared with WT control mice.

As detailed in “Results,” our dissection of the mechanistic link between morphine and retinopathy revealed a complex interplay among morphine engagement with MOR on RECs; morphine-induced production of TNF-α and IL-6, cytokines causing increased expression of both MOR and VEGFR2, the receptor for VEGF on RECs; morphine/MOR engagement transactivating REC VEGFR2; and convergence of MOR, VEGFR2, and IL-6 activation on JAK/STAT3-dependent REC proliferation and angiogenesis. The result is increased angiogenesis, seen in sickle mice as neovascularizing retinopathy, similar to the retinal pathology occurring in humans with SCD.

We emphasize that opioids deployed in clinical use are superimposed upon the baseline, inflammatory milieu of those with SCD. This milieu certainly includes elevated levels of the specific inflammatory mediators we focused on here.38,47-51 Indeed, it has been suggested that the extreme complexity of the systemic inflammatory state in sickle cell anemia may render it truly unique in human biomedicine.47,52 Thus, the role of opioids would be to further augment the preexisting risk state. We are aware of no indication in the medical literature linking morphine with such effects in nonsickle individuals.

Focusing on IL-6, we note that it is a multitasking cytokine, a key regulator of inflammatory and immune responses, and its levels are increased in inflammatory disease.53 It is known to stimulate angiogenesis directly in cornea and cancer, and it does so by stimulating the secretion of VEGF, utilizing the STAT3 signaling pathway.54-56 This is the same effect we found here. Our finding that IL-6 induces strong expression of MOR messenger RNA in RECs, as well as MOR-specific opioid binding, parallels previous observations of morphine effects on the human neuroblastoma cell line SH SY5Y.32 The literature also indicates that administration of opioids to humans leads to elevated IL-6 levels 4 hours later.57 Significantly, humans with SCD have abnormally high levels of both IL-647 and VEGF.6

In the scenario our experiments define, the role of VEGF is fundamental and directly relevant to humans. The retinal vessels from SCD patients who have retinopathy (either proliferative or nonproliferative) are described to have abnormally high presence of VEGF, as detected by immunoreactivity.58 Furthermore, VEGF-targeted therapy using bevacizumab is reported to cause regression of retinal neovascularization in humans with SCD.59 Therefore, our observations that targeting VEGFR2 or MOR inhibits VEGF or morphine-induced proliferation may have a translational implication in ameliorating retinopathy resulting from elevated VEGF or opioids. Indirectly relevant is the fact that elevation of VEGF in the vitreous of patients with diabetes with proliferative retinopathy significantly correlates with an upregulation of inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1, supporting their presumed significance in inflammation affecting vitreoretinal diseases.60

The morphine dose we used in mice may be considered high compared with that used for analgesia clinically. Dosing for mice is ∼12 times that of the human dose based on body weight because of altered metabolism and surface area, which tends to be higher in mice.61 In transgenic sickle mice and cancer mice, a relatively higher dose of opioids is required compared with patients with SCD or cancer, respectively.11,48 This dose has been able to promote tumor angiogenesis similar to promotion of retinal neovascularization.12,14 Dose of opioids varies depending upon the disease. For example, sickle patients and mice require relatively higher doses of morphine for analgesia compared with other conditions with similar pain intensity.48,62,63 Furthermore, opioid tolerance is a phenomenon of central nervous system activity and receptor internalization. However, this may not be the case in proliferative conditions such as retinopathy, because newer cells formed continuously would express a virgin receptor able to bind morphine. This is the case in human prostate cancer, where we found increased MOR in more aggressively growing tumors, which was associated with poorer survival.64

We are not arguing for abandonment of opioids in the sickle context. In contrast, superimposition of the concern raised by our study upon other concerning aspects of opioids including, but not limited to, respiratory suppression and tolerance/addiction would seem to argue for the need to advance alternative approaches to analgesia through experimentation to application.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Carol Taubert, Barbara Benson, and Michael J. Franklin for preparation of graphics and editorial assistance, Ping-Yee Law for receptor binding studies, and Fuad Abdullah for mouse breeding and animal care.

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants RO1 HL068802 and 1U01HL117664-01 (K.G.), HL45922 (G.A.L.), and PO1 HL55552 (R.P.H.); and National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute grant CA109582 (K.G.).

Authorship

Contribution: K.G. developed the concept, analyzed and interpreted the data, supervised the study, and wrote the manuscript; C.C. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; G.A.L. provided expertise on the retinal vascularization technique, interpreted the data, and edited the manuscript; and R.P.H. interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Grifols provided drug for another research project, but it has no conflict with the work presented in this manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: K.G. is a consultant for Ferra Parmaceuticals, Tautona Group, Glycomimetics, and Novartis. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Kalpna Gupta, University of Minnesota Medical School, Mayo Mail Code 480, 420 Delaware St SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455; e-mail: gupta014@umn.edu.

References

Author notes

K.G. and R.P.H. contributed equally to this work.

![Figure 2. MOR is increased in binding affinity and number in retinal endothelial cells of sickle mice. Saturation binding curves (A) and Scatchard plots (B) for binding of [3H]diprenorphine to membranes from RECs isolated from WT and NY1DD mice. (C-D) Competitive binding of opioid receptor ligands with [3H]diprenorphine in membranes derived from RECs of WT (C) and NY1DD mice (D). MOR-specific agonists morphine, D-Ala(2), N-Me-Phe(4), Gly(5)-ol-enkephalin (DAMGO), and etorphine effectively competed for [3H]diprenorphine binding, reaching 0% of the specific binding, whereas {[D-Pen (2, 5)]-Enkephalin} (DPDPE; δ opioid receptor agonist) and U50488H (κ opioid receptor agonist) could not effectively compete for the specifically bound [3H]diprenorphine. In all cases, 10 μM of naloxone was used to determine nonspecific binding. Results represent mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate. (E) MOR expression is increased in retinae and RECs of sickle mice. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction was performed for MOR on total RNA on retinae or RECs isolated from naïve WT and NY1DD mice. Representative image for total RNA from retinae or RECs from 3 mice per group. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/3/7/10.1182_bloodadvances.2018026898/2/m_advances026898f2.png?Expires=1767927139&Signature=kzd-MoIhdF11RmGYxZujE5e6B2Yu7uZ6seEfTLO5CWcpEzYwxEfxOHLPOLFO45zdJaoqYpc172pAHzkduiZ4a1iK5JeV-TfwneOKPxu08Ss47wPkX7-HqSR1JzQkTOmEoORJYeCFzhfpvRYRGlTw0nA6vOdV2WkzXveUjkXV4CBER-laJT0V5v-NeDxgzDGppX1LyDeE7eG4j12q9asABthxhqJVBrHD0HuUHTZ7iqKNexzA3aDVuiliEHhMROhoB-8nhGhsv6XG7at2BZPcAgcb4iZQM8~bUKNDJ6yJVBMHzTYBzJSPFP~awmynwDmb~KdkP31wCwzySxoy7xIHiw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)