Key Points

Neutrophils rolling on P-selectin secrete OSM, which triggers rapid signals through gp130 receptors on endothelial cells.

Paracrine signaling by neutrophil-released OSM enhances P-selectin–dependent adhesion during inflammation and thrombosis.

Abstract

In the earliest phase of inflammation, histamine and other agonists rapidly mobilize P-selectin to the apical membranes of endothelial cells, where it initiates rolling adhesion of flowing neutrophils. Clustering of P-selectin in clathrin-coated pits facilitates rolling. Inflammatory cytokines typically signal by regulating gene transcription over a period of hours. We found that neutrophils rolling on P-selectin secreted the cytokine oncostatin M (OSM). The released OSM triggered signals through glycoprotein 130 (gp130)–containing receptors on endothelial cells that, within minutes, further clustered P-selectin and markedly enhanced its adhesive function. Antibodies to OSM or gp130, deletion of the gene encoding OSM in hematopoietic cells, or conditional deletion of the gene encoding gp130 in endothelial cells inhibited neutrophil rolling on P-selectin in trauma-stimulated venules of the mouse cremaster muscle. In a mouse model of P-selectin–dependent deep vein thrombosis, deletion of OSM in hematopoietic cells or of gp130 in endothelial cells markedly inhibited adhesion of neutrophils and monocytes and the rate and extent of thrombus formation. Our results reveal a paracrine-signaling mechanism by which neutrophil-released OSM rapidly influences endothelial cell function during physiological and pathological inflammation.

Introduction

In acute inflammation, circulating neutrophils tether to and roll along postcapillary venules.1 They then arrest, spread, and migrate through endothelial cell junctions to reach injured or infected tissues.2 Rolling neutrophils integrate signals as they engage selectins and chemokines on activated endothelial cells.3,4 These signals activate neutrophil β2 integrins, which interact with ICAM-1 on endothelial cells to reduce rolling velocities and cause arrest.

Signaling in endothelial cells is a proximal event in the inflammatory response.2 Agonists such as thrombin or histamine rapidly (in minutes) mobilize P-selectin from the membranes of Weibel-Palade bodies to the apical plasma membrane,5-7 where it initiates neutrophil rolling.8 P-selectin dimerizes through transmembrane domain interactions.9,10 It further clusters in clathrin-coated pits before it is internalized.11 Both dimerization and clustering enhance P-selectin’s ability to mediate rolling.12,13 Compared with histamine, thrombin reduces clathrin-mediated clustering of P-selectin through a RhoA-dependent mechanism that dampens rolling.14 Thus, differential signaling in endothelial cells can affect the adhesive function of P-selectin.

Cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) also trigger inflammatory signals in endothelial cells.2 They act primarily by inducing transcription of messenger RNA for adhesion proteins such as E-selectin and ICAM-1 and chemokines such as CXCL1. Because of the time required for transcription and translation (hours), these proteins reach the endothelial cell surface later than P-selectin mobilized from Weibel-Palade bodies.

Oncostatin M (OSM) is a member of the IL-6 family of cytokines.15,16 OSM and related cytokines bind to heterodimeric receptors that share the signaling subunit glycoprotein 130 (gp130).15 Endothelial cells express many OSM receptors.17 Previous studies examined how exogenous OSM affects gene expression in cultured human endothelial cells over many hours.18-20 For example, OSM increases transcription of messenger RNA for P-selectin with delayed kinetics compared with genes upregulated by other cytokines.18 No study has addressed whether OSM influences endothelial cell function in vivo. Some macrophages and T cells activated in vitro express OSM.16,21,22 In the circulation, however, neutrophils are the predominant cells that express OSM. Neutrophils store OSM in granules that could be readily mobilized.23,24 Ligand engagement of gp130-containing receptors activates kinases that could induce rapid effector functions.15 We therefore asked whether rolling neutrophils release OSM that triggers rapid signals in endothelial cells. We found that neutrophil-derived OSM enhanced P-selectin clustering in clathrin-coated pits of endothelial cells. This paracrine signaling markedly augmented P-selectin–mediated rolling in postcapillary venules and P-selectin–mediated thrombosis in flow-restricted veins.

Methods

Detailed information on reagents and protocols is provided in supplemental Methods.

Cells

Blood was collected from healthy volunteers with a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation. Human neutrophils were isolated as described.13 Umbilical cords were provided by the Pathology Department of Mercy Laboratory Oklahoma with a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mercy Laboratory Oklahoma. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were isolated and cultured as described.13 HUVECs were passaged ≤2 times for all experiments.

Mouse bone marrow leukocytes were isolated as described.25 Briefly, cells were isolated by gently flushing femurs and tibias with 10 mL of Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) without Ca2+ or Mg2+. After lysing red blood cells in 150 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM NaHCO3, and 1 mM EDTA, the cells were washed with HBSS and resuspended at 2 × 106/mL in HBSS containing 1.26 mM Ca2+, 0.81 mM Mg2+, and 0.5% human serum albumin. Neutrophils were isolated from bone marrow leukocytes by a density gradient method.26

Isolation of mouse lung endothelial cells (MLECs) was performed as described previously,27,28 with minor modifications. Briefly, lungs from 2 or 3 mice were washed, minced into 1- to 2-mm2 pieces in 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS)–Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) with antibiotics, and digested with collagenase type I (2 mg/mL) at 37°C for 1 hour with occasional vortex. The digested tissues were filtered through a 70-μm cell strainer and centrifuged. The cells were cultured on gelatin-coated dishes with DMEM containing 20% FBS and 100 μg/mL endothelial cell growth factors (Sigma-Aldrich). After 48 hours, the cells were harvested with trypsin and EDTA, and incubated with biotin-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD102 monoclonal antibody (mAb; BD Biosciences) followed by streptavidin-conjugated microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). The CD102+ cells were collected with a magnetic separator (StemCell Technologies), and cultured on gelatin-coated plates with DMEM containing 20% FBS and 100 μg/mL endothelial cell growth factors. As ascertained by flow cytometry, ∼90% were endothelial cells that stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated rat anti-mouse CD31 mAb.

Antibodies and reagents

Mouse anti-human P-selectin mAbs S12 and G1,29 anti-human gp130 mAb 4B11,30 and anti-human P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) mAbs PL1 and PL231 were described. Goat anti–P-selectin immunoglobulin G (IgG) was described.32 Rat anti-mouse P-selectin mAb RB40.34 and rat anti-mouse PSGL-1 mAb 4RA10 were described.33-35 Commercial antibodies are detailed in supplemental Methods.

Mice

All mice were backcrossed with C57BL/6J mice at least 10 times. C57BL/6J mice were used as wild-type (WT) controls. Osm−/− knockout mice lacking OSM36 were provided by Atsushi Miyajima (University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan).

gp130flox/flox mice37 were crossed with transgenic mice expressing Cre recombinase ERT2 under control of the promoter for the cdh5 gene that encodes vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-cadherin; VECad-Cre-ERT2).38 WT mice injected with tamoxifen were used as controls. Cre-mediated recombination was induced by intraperitoneal injection of tamoxifen (2 mg per mouse) for 5 consecutive days. All mouse protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation.

Flow cytometry

Human heparinized blood from healthy volunteers was collected by venipuncture, and red blood cells were removed by dextran sedimentation. Mouse-heparinized blood was obtained from the facial vein, and red blood cells were lysed. Human or mouse peripheral blood leukocytes were washed in HBSS with 0.5% human serum albumin. The cells were preincubated with 5 μg/mL Fc-blocking antibody (BD Biosciences) for 20 minutes at 4°C, and washed in HBSS with 0.5% human serum albumin. Both human and mouse cells were fixed and permeabilized with a Cytofix/Cytoperm fixation and permeabilization kit (BD Biosciences). The cells were then washed with BD Perm/Wash buffer (BD Biosciences). Mouse anti-human OSM IgG2a or nonimmune control mouse IgG2a was labeled using an Alexa Fluor 488 mouse antibody labeling kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Goat anti-mouse OSM IgG or nonimmune control goat IgG was labeled using an Alexa Fluor 488 goat IgG-labeling kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For human cells, the fixed and permeabilized cells were stained with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated isotype control mouse IgG2a, anti-CD3, anti-CD14, or anti-CD16b, plus Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated mouse anti-mouse OSM IgG or control mouse IgG. For mouse cells, the fixed and permeabilized cells were stained with 5 μg/mL PE-conjugated isotype control rat IgG, anti-Ly6G, anti–macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor (M-CSFR), or anti-CD3, plus Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated goat anti-mouse OSM IgG or control goat IgG. The neutrophil, monocyte, or T-cell population was identified by its scatter properties and by CD16b, CD14, or CD3 staining for human cells, or Ly6G, M-CSFR, or CD3 staining for mouse cells, respectively. In some experiments, mouse peripheral blood leukocytes were pretreated with Fc-blocking antibody and then incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated anti-Ly6G, anti-M-CSFR, or anti-CD3, plus control rat IgG or rat anti-mouse gp130 mAb followed by PE-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG, or plus PE-conjugated anti–PSGL-1, anti–β2 integrin, anti-CD44, or anti–L-selectin.

In other experiments, thrombi collected from the inferior vena cava (IVC) 24 hours after stenosis were minced into small pieces and digested in HBSS with Ca2+ and Mg2+ containing 1 mg/mL collagenase type IV (Worthington) and 100 μg/mL DNAse I (Roche) for 15 minutes at 37°C, with occasional vortex. After digestion, the single-cell suspension was passed through a 100-μm cell strainer and washed in HBSS without Ca2+ and Mg2+, containing 5 mM EDTA and 1% human serum albumin. The cells were preincubated with 5 μg/mL Fc-blocking antibody for 20 minutes at 4°C, and then incubated with 5 μg/mL PE-conjugated anti-Ly6G or anti–M-CSFR for 20 minutes at 4°C. Six-micrometer polystyrene beads (PolySciences) (1 × 105) were added to 500 μL of cell suspension. The neutrophil or monocyte population was identified by its scatter properties and by Ly6G or M-CSFR staining. The number of neutrophils or monocytes per thrombus was quantified.

OSM release from human or mouse neutrophils

Human neutrophils (2 × 107) or mouse neutrophils (107) in 1 mL of HBSS/0.5% human serum albumin with Ca2+ and Mg2+ were incubated, respectively, on immobilized human platelet-derived P-selectin9 or on mouse P-selectin–IgM– or control CD45-IgM–coated plates with or without movement on a rotary shaker at 70 rpm for 30 minutes at room temperature. After incubation, the buffer was collected and adherent cells were lysed with 1 mL of 1% Triton X-100, 125 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 10 mM EDTA, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and a protease inhibitor cocktail (1:50; Thermo Fisher Scientific). OSM in buffer or lysate was measured with human or mouse OSM ELISA kits (R&D Systems).

Intravital microscopy

Intravital video microscopy of the cremaster muscle of anesthetized mice was performed as described.39-41 Exteriorization of the cremaster muscle was completed within 10 minutes. In some experiments, 10 µg of goat anti–ICAM-1 IgG, goat anti-gp130 IgG, goat anti-OSM IgG, nonimmune goat IgG, or rat anti–P-selectin mAb was injected IV 10 minutes before cremaster exteriorization. In some experiments, neutrophils isolated from WT or Osm−/− bone marrow leukocytes were labeled with red fluorescence dye (PKH26) or far red fluorescence dye (CellVue Claret). Labeled WT cells, Osm−/− cells, or a 1:1 mixture of WT and Osm−/− cells (5 × 106 labeled cells of each genotype in 200 μL of saline) were injected into Osm−/− mice IV just before exteriorization of the cremaster muscle. The vessels were stained by IV injection of 5 μg of Alexa Fluor 488–labeled anti-CD31 mAb 1 hour before exteriorization of the cremaster muscle. In all experiments, leukocyte rolling and adhesion were recorded in 3 to 5 venules from each mouse. Microvessel diameters, length, and centerline velocity were comparable in mice from all genotypes. Mean leukocyte rolling velocities and rolling fluxes were analyzed offline.

Bone marrow transplantation

Bone marrow transplantation was performed as described.28 Briefly, bone marrow cells from WT or Osm−/− mice were isolated, and 2 × 106 cells were injected IV into lethally irradiated Osm−/− or WT mice, respectively. After 8 weeks, reconstitution of hematopoietic cells was evaluated by intracellular staining of OSM in Ly6G+ neutrophils from peripheral blood collected from facial vein.

Flow chamber assay

Rolling of mouse bone marrow neutrophils on confluent monolayers of MLECs or on immobilized P- or E-selectin with or without coimmobilized ICAM-1 or CXCL1 was performed as described,26 with modifications detailed in supplemental Methods. Rolling of human neutrophils on confluent monolayers of HUVECs or on immobilized human P-selectin was performed as described.11,13

Site density measurement

HUVECs were incubated for 10 minutes in the presence or absence of 0.1 mM histamine or 10 ng/mL exogenous human OSM. The surface density of P-selectin on HUVECs was measured using 125I-labeled mAb S12 as described.11

Internalization assay

HUVECs were incubated for 10 minutes in the presence or absence of 0.1 mM histamine or 10 ng/mL exogenous human OSM. The rate of internalization of P-selectin was measured by the ability of an acidic buffer to remove 125I-labeled mAb G1, prebound to the cell surface at 4°C, after warming to 37°C for various intervals.11 The cell-bound radioactivity remaining at each time point represented the amount of internalized P-selectin and was presented as a percentage of the initial cell-bound radioactivity.

Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy

HUVECs were incubated for 10 minutes in the presence or absence of 0.1 mM histamine or 10 ng/mL exogenous human OSM. The cells were fixed and permeabilized, and confocal microscopy was used to measure colocalization of cell-surface P-selectin with α-adaptin.13

Deep vein thrombosis

Deep vein thrombosis induced by flow restriction of the IVC was performed as described.42,43 Mice were placed under anesthesia by continuous inhalation of 1% to 2% isoflurane in 100% oxygen. Intestines were exteriorized and covered with saline-moistened gauze to prevent drying after laparotomy. The IVC was gently separated and permanently ligated over a 30-gauge needle with a 7.0 nylon, nonabsorbable suture (Braintree Scientific, Inc). The needle spacer was then removed to prevent complete vein occlusion. Side branches were not ligated. Control mice underwent sham surgery without occlusion of the IVC. The peritoneum and skin were then closed.

Ultrasonography was performed with a Vevo 2100 system with 40-MHz mouse scan head (VisualSonics) to confirm flow restriction and to monitor thrombus progression, including the frequency and size of the thrombus. Color Doppler mode or pulse-wave Doppler mode was used for measuring the flow direction or the flow velocity, respectively.

In some mice, spinning-disk intravital microscopy of the IVC was performed as described.42,44 The IVC was superfused with thermocontrolled (35°C) bicarbonate-buffered saline 3 hours after occlusion. One hour before microscopy, 4 μg of PE-conjugated anti-Ly6G mAb or 4 μg of PE-conjugated anti-mouse M-CSFR mAb in 200 μL of saline was injected through the retro-orbital venous plexus. The PE-labeled neutrophils or monocytes in the IVC were observed 1 mm below the ligation in the experimental group or 1 to 2 mm below the left renal vein in sham-surgery control mice. Rolling or adherent cells were defined as described.42

Thrombi, collected from mice euthanized 24 hours after ligation, were used for measurement of weight, for flow cytometry, and for western blots.

Statistical analysis

Statistical differences between groups were analyzed using the unpaired and 2-sided tail Student t test or with 1-way analysis of variance with the post hoc multiple-comparison test. Thrombus frequencies were analyzed using χ2 tests of contingency tables. Values were considered significant at P < .05.

Results

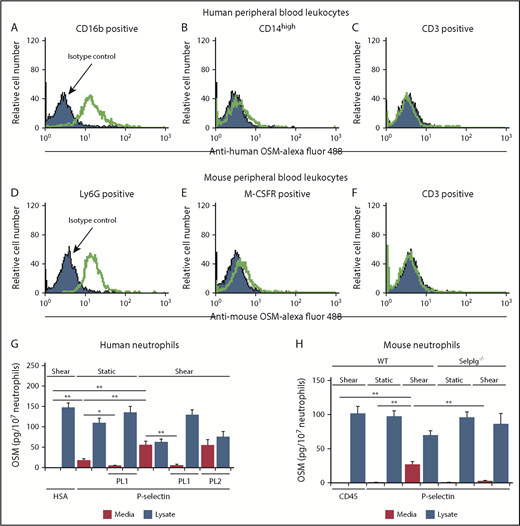

Adhesion of human or mouse neutrophils to P-selectin triggers release of OSM

We used flow cytometry to detect OSM in permeabilized leukocytes from humans and mice. Leukocyte subsets were identified by light scatter and immunostaining. OSM was expressed by neutrophils but not by monocytes or lymphocytes (Figure 1A-F). We confirmed expression of OSM in lysates of human and mouse neutrophils by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Figure 1G-H). Incubation of human or mouse neutrophils with immobilized P-selectin under variable shear forces, and to a lesser extent under static conditions, triggered release of OSM into the medium (Figure 1G-H). Blocking anti–PSGL-1 mAb PL1, but not nonblocking anti–PSGL-1 mAb PL2, prevented OSM release from human neutrophils, and PSGL-1–deficient neutrophils from Selplg−/− mice did not release OSM. These data demonstrate that PSGL-1 engagement as neutrophils adhere to P-selectin, particularly under shear, is sufficient to induce secretion of OSM.

Adhesion of human or mouse neutrophils to P-selectin triggers release of OSM. (A-F) Representative flow cytometric data of intracellular OSM expression in permeabilized CD16b+ human neutrophils, CD14-high human monocytes, CD3+ human lymphocytes, Ly6G+ mouse neutrophils, M-CSFR+ mouse monocytes, or CD3+ mouse T lymphocytes. The indicated cell population was defined by its specific surface marker and by light scatter. (G) Measurement of OSM in medium or in lysates of human neutrophils after incubation with immobilized human serum albumin (HSA) or human platelet-derived P-selectin with or without shear on a rotary shaker, in the presence or absence of blocking anti-human PSGL-1 mAb PL1 or nonblocking anti–PSGL-1 mAb PL2. (H) Measurement of OSM in medium or in lysates of neutrophils from WT or Selplg−/− mice after incubation with immobilized mouse CD45-IgM or mouse P-selectin–IgM with or without shear on a rotary shaker. The data in panels A-F are representative of 3 experiments. The data in panels G-H represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) from 3 experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Adhesion of human or mouse neutrophils to P-selectin triggers release of OSM. (A-F) Representative flow cytometric data of intracellular OSM expression in permeabilized CD16b+ human neutrophils, CD14-high human monocytes, CD3+ human lymphocytes, Ly6G+ mouse neutrophils, M-CSFR+ mouse monocytes, or CD3+ mouse T lymphocytes. The indicated cell population was defined by its specific surface marker and by light scatter. (G) Measurement of OSM in medium or in lysates of human neutrophils after incubation with immobilized human serum albumin (HSA) or human platelet-derived P-selectin with or without shear on a rotary shaker, in the presence or absence of blocking anti-human PSGL-1 mAb PL1 or nonblocking anti–PSGL-1 mAb PL2. (H) Measurement of OSM in medium or in lysates of neutrophils from WT or Selplg−/− mice after incubation with immobilized mouse CD45-IgM or mouse P-selectin–IgM with or without shear on a rotary shaker. The data in panels A-F are representative of 3 experiments. The data in panels G-H represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) from 3 experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01.

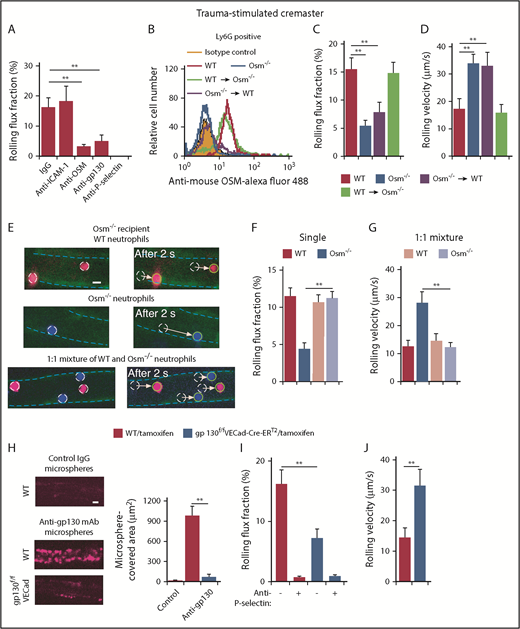

Interactions of neutrophil-derived OSM with gp130-containing receptors on endothelial cells enhance P-selectin–dependent rolling in mouse postcapillary venules

We used intravital microscopy to visualize neutrophil rolling in postcapillary venules of the mouse cremaster muscle. Surgical trauma causes mast cells to release histamine, which induces rapid mobilization of P-selectin to the endothelial cell surface.45 Flowing leukocytes, almost all neutrophils, roll in trauma-stimulated venules in a P-selectin–dependent manner.46 Very few rolling neutrophils arrest on ICAM-1 because there is insufficient CXCL1 to activate β2 integrins. We monitored the rolling flux fraction, which normalizes the number of rolling cells to the number of circulating neutrophils. Consistent with published data,46 we observed that injecting anti–P-selectin antibody, but not anti-ICAM-1 antibody, eliminated neutrophil rolling (Figure 2A). Remarkably, injecting antibodies to OSM or gp130 reduced the rolling flux fraction almost as much as anti–P-selectin antibody (Figure 2A). These data suggest that OSM augments P-selectin–dependent rolling on endothelial cells through gp130-dependent signaling.

Interactions of neutrophil-derived OSM with gp130-containing receptors on endothelial cells enhance P-selectin–dependent rolling in mouse postcapillary venules. (A) Rolling flux fraction of leukocytes in postcapillary venules of trauma-stimulated cremaster muscle from WT mice with or without injection of the indicated mAb. (B) Representative flow cytometric data of intracellular OSM expression in Ly6G+ neutrophils from WT mice, Osm−/− mice, irradiated Osm−/− mice transplanted with bone marrow from WT mice, or irradiated WT mice transplanted with bone marrow from Osm−/− mice. (C-D) Rolling flux fraction and rolling velocity of leukocytes in postcapillary venules of trauma-stimulated cremaster muscle from the indicated genotype. (E) Representative fluorescent images of injected labeled neutrophils rolling in postcapillary venules of trauma-stimulated cremaster muscle of Osm−/− mice. Venular endothelial cells were labeled with Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-CD31 mAb, outlined by the blue dashed line. The images depict distances rolled by the circled cells in a 2-second interval. The arrow indicates the path of each rolling cell. Top, Injected WT neutrophils (red); middle, injected Osm−/− neutrophils (blue); bottom, injected 1:1 mixture of WT (red) and Osm−/− (blue) neutrophils. Scale bar, 10 μm. (F-G) Rolling flux fraction and rolling velocity of injected labeled cells. (H, left) Representative images of Fluoresbrite Red microspheres coated with anti-gp130 mAb or isotype control IgG adhering to endothelial cells in trauma-stimulated venules of cremaster muscle from tamoxifen-treated WT or gp130flox/floxVECad-Cre-ERT2 mice. To block rolling of leukocytes, which also express gp130, anti-mouse PSGL-1 mAb 4RA10 was injected 1 hour before exteriorization of the cremaster muscle. (H, right) Quantification of the covered area of adherent microspheres with digital image analysis software. The data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from 10 venules from 5 mice. Scale bar, 10 μm. (I-J) Rolling flux fraction and rolling velocity of leukocytes in postcapillary venules of trauma-stimulated cremaster muscle from tamoxifen-treated WT or gp130flox/floxVECad-Cre-ERT2 mice, with or without preinjection of blocking anti–P-selectin mAb. The data in panels B and H are representative of 5 experiments. The data in panels A,C-D,F,I-J represent the mean ± SEM from 10 to 20 venules from 4 to 8 mice in each group. **P < .01.

Interactions of neutrophil-derived OSM with gp130-containing receptors on endothelial cells enhance P-selectin–dependent rolling in mouse postcapillary venules. (A) Rolling flux fraction of leukocytes in postcapillary venules of trauma-stimulated cremaster muscle from WT mice with or without injection of the indicated mAb. (B) Representative flow cytometric data of intracellular OSM expression in Ly6G+ neutrophils from WT mice, Osm−/− mice, irradiated Osm−/− mice transplanted with bone marrow from WT mice, or irradiated WT mice transplanted with bone marrow from Osm−/− mice. (C-D) Rolling flux fraction and rolling velocity of leukocytes in postcapillary venules of trauma-stimulated cremaster muscle from the indicated genotype. (E) Representative fluorescent images of injected labeled neutrophils rolling in postcapillary venules of trauma-stimulated cremaster muscle of Osm−/− mice. Venular endothelial cells were labeled with Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-CD31 mAb, outlined by the blue dashed line. The images depict distances rolled by the circled cells in a 2-second interval. The arrow indicates the path of each rolling cell. Top, Injected WT neutrophils (red); middle, injected Osm−/− neutrophils (blue); bottom, injected 1:1 mixture of WT (red) and Osm−/− (blue) neutrophils. Scale bar, 10 μm. (F-G) Rolling flux fraction and rolling velocity of injected labeled cells. (H, left) Representative images of Fluoresbrite Red microspheres coated with anti-gp130 mAb or isotype control IgG adhering to endothelial cells in trauma-stimulated venules of cremaster muscle from tamoxifen-treated WT or gp130flox/floxVECad-Cre-ERT2 mice. To block rolling of leukocytes, which also express gp130, anti-mouse PSGL-1 mAb 4RA10 was injected 1 hour before exteriorization of the cremaster muscle. (H, right) Quantification of the covered area of adherent microspheres with digital image analysis software. The data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from 10 venules from 5 mice. Scale bar, 10 μm. (I-J) Rolling flux fraction and rolling velocity of leukocytes in postcapillary venules of trauma-stimulated cremaster muscle from tamoxifen-treated WT or gp130flox/floxVECad-Cre-ERT2 mice, with or without preinjection of blocking anti–P-selectin mAb. The data in panels B and H are representative of 5 experiments. The data in panels A,C-D,F,I-J represent the mean ± SEM from 10 to 20 venules from 4 to 8 mice in each group. **P < .01.

Osm−/− mice are healthy without specific challenge and have moderate anemia, thrombocytopenia, and lymphocytosis.36 Neutrophils from Osm−/− mice expressed normal levels of major adhesion receptors, including PSGL-1 and β2 integrins (supplemental Figure 1). They exhibited normal integrin-dependent slow rolling on purified P- or E-selectin coimmobilized with ICAM-1 (supplemental Figure 2A,C), and normal integrin-dependent arrest and spreading when CXCL1 was also coimmobilized (supplemental Figure 2B,D). To determine whether P-selectin–dependent rolling on endothelial cells is regulated by OSM from hematopoietic or nonhematopoietic cells, we conducted reciprocal bone marrow transplantation experiments. Flow cytometry confirmed reconstitution of WT neutrophils expressing OSM in OSM-deficient recipients and of OSM-deficient neutrophils in WT recipients (Figure 2B). Mice lacking OSM in hematopoietic cells, like mice with global deletion of OSM, had moderate anemia, thrombocytopenia, and lymphocytosis (supplemental Table 1). Mice lacking OSM only in hematopoietic cells, like mice with global deletion of OSM, exhibited markedly reduced numbers of rolling cells and elevated rolling velocities in postcapillary venules (Figure 2C-D). In contrast, neutrophils rolled normally in mice lacking OSM in nonhematopoietic cells. These results demonstrate that OSM from hematopoietic cells augments P-selectin–dependent rolling. Because neutrophils are the only circulating hematopoietic cells that express OSM, our data implicate neutrophil-derived OSM in this process. We further confirmed the importance of neutrophil-released OSM by injecting differentially labeled WT neutrophils, Osm−/− neutrophils, or a 1:1 mixture of WT and Osm−/− neutrophils into Osm−/− mice. Spinning-disk microscopy was used to visualize rolling of fluorescent neutrophils in trauma-stimulated venules. Compared with labeled WT neutrophils, labeled Osm−/− neutrophils rolled in fewer numbers and with faster velocities when cells from each genotype were injected separately (Figure 2E-G). In contrast, Osm−/− neutrophils rolled like WT neutrophils when they were injected together (Figure 2E-G). These results indicate that OSM released from rolling WT neutrophils can correct the defective rolling of Osm−/− neutrophils.

We hypothesized that neutrophil-released OSM enhances P-selectin–dependent rolling by transducing signals through gp130-containing receptors on endothelial cells. To test this hypothesis, we crossed gp130flox/flox mice37 with VECad-Cre-ERT2 mice,38 which express a tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase under control of the promoter for the cdh5 gene that encodes VE-cadherin. Tamoxifen administration to VECad-Cre-ERT2 mice deletes floxed alleles in endothelial cells but not in hematopoietic or other cells.38 Tamoxifen treatment did not alter peripheral blood counts (supplemental Table 1). We confirmed that tamoxifen did not induce deletion of gp130 in hematopoietic cells of gp130flox/floxVECad-Cre-ERT2 mice (supplemental Figure 3). We further confirmed tamoxifen-inducible deletion of gp130 in endothelial cells of gp130flox/floxVECad-Cre-ERT2 mice by injecting fluorescent microspheres coated with control IgG or anti-gp130 mAb. After tamoxifen treatment, spinning-disk intravital microscopy revealed diffuse binding of anti-gp130–coated microspheres in postcapillary venules of WT mice but not of gp130flox/floxVECad-Cre-ERT2 mice (Figure 2H). Furthermore, tamoxifen treatment markedly impaired P-selectin–dependent neutrophil rolling in venules of gp130flox/flox VECad-Cre-ERT2 mice (Figure 2I-J). These results suggest that neutrophil-derived OSM augments P-selectin–dependent rolling through gp130-dependent signaling in endothelial cells.

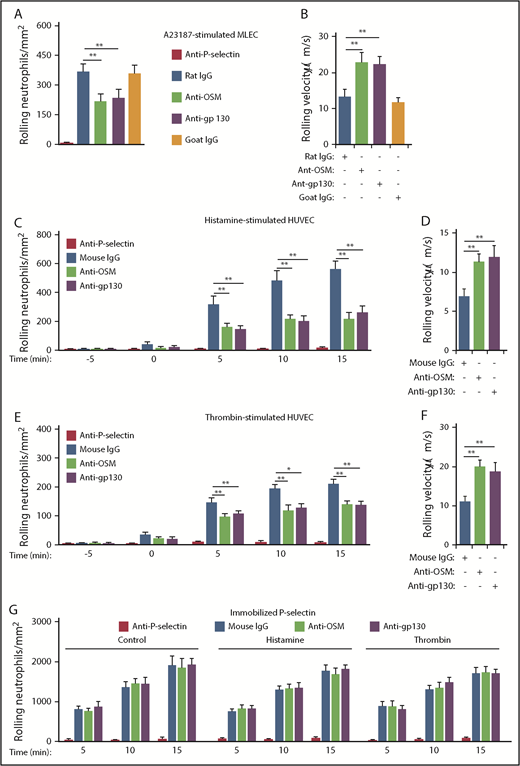

Interactions of neutrophil-derived OSM with gp130-containing receptors enhance P-selectin–dependent rolling on stimulated mouse or human endothelial cells in vitro

To further address how OSM regulates P-selectin–mediated rolling, we perfused mouse neutrophils over monolayers of MLECs, which constitutively express P-selectin that is stored in Weibel-Palade bodies.47 Because MLECs respond weakly to histamine,48 we used the calcium ionophore A23187 to mobilize P-selectin to the apical cell surface. Rolling neutrophils rapidly accumulated on A23187-stimulated MLECs (Figure 3A). Anti–P-selectin mAb prevented neutrophil rolling, confirming its dependence on P-selectin. Notably, blocking mAbs to OSM or gp130 significantly reduced the number of rolling neutrophils (Figure 3A) and increased the rolling velocities of the remaining cells (Figure 3B). We next perfused human neutrophils over monolayers of HUVECs. Within minutes, histamine or thrombin treatment mobilizes P-selectin from Weibel-Palade bodies to the apical surface of HUVECs.5,7 As observed previously,8,14 rolling neutrophils rapidly accumulated on HUVECs after adding histamine or thrombin to the monolayer (Figure 3C,E). Anti–P-selectin mAb prevented neutrophil rolling, confirming its dependence on P-selectin. Blocking mAbs to OSM or gp130 significantly reduced the number of rolling neutrophils (Figure 3C,E) and increased the rolling velocities of the remaining cells (Figure 3D,F). Rolling neutrophils also rapidly accumulated on immobilized, purified P-selectin, and anti–P-selectin mAb prevented rolling (Figure 3G). However, neither histamine nor thrombin, nor mAbs to OSM or gp130, affected neutrophil rolling on purified P-selectin (Figure 3G). These results demonstrate that neutrophil-released OSM must engage gp130-containing receptors on endothelial cells to enhance P-selectin–dependent rolling.

Interactions of neutrophil-derived OSM with gp130-containing receptors enhance P-selectin–dependent rolling on stimulated mouse and human endothelial cells in vitro. (A) Number of mouse neutrophils rolling on MLECs 30 minutes after A23187 stimulation in the presence of the indicated mAb. (B) Mean rolling velocity of mouse neutrophils on MLECs 30 minutes after A23187 stimulation in the presence of the indicated antibody. (C) Number of human neutrophils rolling on HUVECs at the indicated time before or after adding histamine (time = 0), in the presence of the indicated antibody. (D) Mean rolling velocity of neutrophils on HUVECs 5 minutes after adding histamine, in the presence of the indicated antibody. (E) Number of neutrophils rolling on HUVECs at the indicated time before or after adding thrombin (time = 0), in the presence of the indicated antibody. (F) Mean rolling velocity of neutrophils on HUVECs 5 minutes after adding thrombin, in the presence of the indicated antibody. (G) Number of neutrophils rolling on immobilized purified P-selectin at the indicated time after initiation of perfusion, in the presence or absence of histamine, thrombin, and the indicated antibody. The data represent the mean ± SD from 3 experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Interactions of neutrophil-derived OSM with gp130-containing receptors enhance P-selectin–dependent rolling on stimulated mouse and human endothelial cells in vitro. (A) Number of mouse neutrophils rolling on MLECs 30 minutes after A23187 stimulation in the presence of the indicated mAb. (B) Mean rolling velocity of mouse neutrophils on MLECs 30 minutes after A23187 stimulation in the presence of the indicated antibody. (C) Number of human neutrophils rolling on HUVECs at the indicated time before or after adding histamine (time = 0), in the presence of the indicated antibody. (D) Mean rolling velocity of neutrophils on HUVECs 5 minutes after adding histamine, in the presence of the indicated antibody. (E) Number of neutrophils rolling on HUVECs at the indicated time before or after adding thrombin (time = 0), in the presence of the indicated antibody. (F) Mean rolling velocity of neutrophils on HUVECs 5 minutes after adding thrombin, in the presence of the indicated antibody. (G) Number of neutrophils rolling on immobilized purified P-selectin at the indicated time after initiation of perfusion, in the presence or absence of histamine, thrombin, and the indicated antibody. The data represent the mean ± SD from 3 experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01.

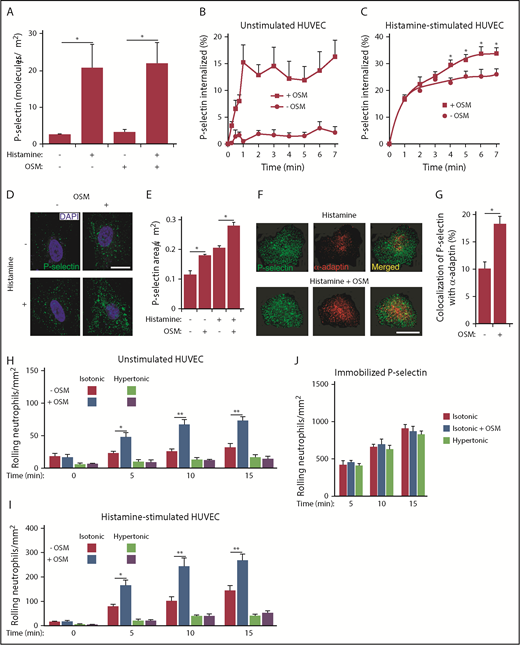

OSM increases clustering of P-selectin in clathrin-coated pits of human endothelial cells

Unstimulated HUVECs express very few P-selectin molecules on the apical surface.5,7 The surface density of P-selectin peaks ∼10 minutes after addition of histamine or thrombin and then declines as P-selectin is internalized through clathrin-coated pits.7,49 We measured binding of radiolabeled anti–P-selectin mAb to HUVECs that were chilled to 4°C (to prevent endocytosis) before or 10 minutes after treatment with histamine, OSM, or both agonists. OSM treatment did not alter the overall number of P-selectin molecules on unstimulated or histamine-stimulated HUVECs (Figure 4A).

OSM increases clustering of P-selectin in clathrin-coated pits of human endothelial cells. (A) Density of P-selectin molecules on the surface of HUVECs 10 minutes after adding control buffer or the indicated agonist. (B) Internalization rate of P-selectin on HUVECs 10 minutes after adding buffer with or without or OSM. (C) Internalization rate of P-selectin on HUVECs 10 minutes after adding histamine-containing buffer with or without OSM. (D) Representative confocal immunofluorescence images of HUVECs 10 minutes after treatment with histamine, OSM, or both agonists. The sections were fixed, permeabilized, and incubated with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue) to visualize cell nuclei and with anti–P-selectin antibody (green) to visualize the distribution of P-selectin. Scale bar, 20 μm. (E) Quantification of the areas of P-selectin puncta. (F) Representative confocal immunofluorescence images of HUVECs 10 minutes after treatment with histamine or with histamine plus OSM. The sections were fixed, permeabilized, and incubated with anti–P-selectin antibody (green) and anti–α-adaptin antibody (red). Merged images revealed partial colocalization of α-adaptin with P-selectin (yellow). Scale bar, 20 μm. (G) Quantification of colocalization of P-selectin with α-adaptin. (H) Number of fixed human neutrophils, in isotonic or hypertonic medium with or without OSM, rolling on HUVECs at the indicated time. (I) Number of fixed human neutrophils, in isotonic or hypertonic medium with or without OSM, rolling on HUVECs at the indicated time after addition of histamine. (J) Number of fixed human neutrophils, in isotonic or hypertonic medium with or without OSM, rolling on immobilized purified P-selectin at the indicated time. The data in panels A-C,E,G represent the mean ± SEM from 3 to 8 experiments. The data in panels D and F are representative of 4 experiments. The data in panels H-J represent the mean ± SD from 3 experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01.

OSM increases clustering of P-selectin in clathrin-coated pits of human endothelial cells. (A) Density of P-selectin molecules on the surface of HUVECs 10 minutes after adding control buffer or the indicated agonist. (B) Internalization rate of P-selectin on HUVECs 10 minutes after adding buffer with or without or OSM. (C) Internalization rate of P-selectin on HUVECs 10 minutes after adding histamine-containing buffer with or without OSM. (D) Representative confocal immunofluorescence images of HUVECs 10 minutes after treatment with histamine, OSM, or both agonists. The sections were fixed, permeabilized, and incubated with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue) to visualize cell nuclei and with anti–P-selectin antibody (green) to visualize the distribution of P-selectin. Scale bar, 20 μm. (E) Quantification of the areas of P-selectin puncta. (F) Representative confocal immunofluorescence images of HUVECs 10 minutes after treatment with histamine or with histamine plus OSM. The sections were fixed, permeabilized, and incubated with anti–P-selectin antibody (green) and anti–α-adaptin antibody (red). Merged images revealed partial colocalization of α-adaptin with P-selectin (yellow). Scale bar, 20 μm. (G) Quantification of colocalization of P-selectin with α-adaptin. (H) Number of fixed human neutrophils, in isotonic or hypertonic medium with or without OSM, rolling on HUVECs at the indicated time. (I) Number of fixed human neutrophils, in isotonic or hypertonic medium with or without OSM, rolling on HUVECs at the indicated time after addition of histamine. (J) Number of fixed human neutrophils, in isotonic or hypertonic medium with or without OSM, rolling on immobilized purified P-selectin at the indicated time. The data in panels A-C,E,G represent the mean ± SEM from 3 to 8 experiments. The data in panels D and F are representative of 4 experiments. The data in panels H-J represent the mean ± SD from 3 experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01.

We next measured the internalization rate of P-selectin by quantifying the ability of acidic buffer to remove radiolabeled anti–P-selectin mAb, prebound to the cell surface at 4°C, after warming the cells to 37°C for various intervals. On unstimulated HUVECs, OSM markedly increased the acid-resistant pool of P-selectin during the first minute after rewarming HUVECs to 37°C, consistent with more rapid internalization (Figure 4B). On histamine-treated HUVECs, OSM did not alter the already rapid internalization rate of P-selectin within the first 2 minutes of rewarming. However, it increased the acid-resistant internalized pool of P-selectin over the next 5 minutes (Figure 4C).

The accelerated internalization of P-selectin suggested that OSM enhances the recruitment of P-selectin into clathrin-coated pits. We used confocal immunofluorescence microscopy to visualize the distribution of P-selectin on HUVECs that were fixed and permeabilized after treatment with histamine, OSM, or both agonists. OSM increased the average size of P-selectin puncta on both unstimulated and histamine-stimulated HUVECs, consistent with greater clustering in clathrin-coated pits (Figure 4D-E). Furthermore, OSM increased the colocalization of P-selectin with α-adaptin, a component of clathrin-coated pits13,50 (Figure 4F-G). These results demonstrate that OSM augments clustering of P-selectin in clathrin-coated pits before it is internalized.

Clustering of P-selectin in clathrin-coated pits facilitates neutrophil rolling under flow.13 To determine whether OSM enhances rolling by clustering P-selectin, we incubated unstimulated HUVECs with control isotonic medium or with hypertonic medium to disrupt clathrin-coated pits,51 which prevents clustering of P-selectin.13 We fixed neutrophils to prevent release of endogenous OSM and to limit the effects of the hypertonic medium to HUVECs. We then perfused the fixed neutrophils over HUVEC monolayers. Adding OSM to unstimulated or histamine-stimulated HUVECs rapidly increased rolling of fixed neutrophils in isotonic but not hypertonic medium (Figure 4H-I). Neither OSM nor hypertonic medium affected rolling of fixed neutrophils on purified P-selectin (Figure 4J). These data demonstrate that OSM-triggered clustering of P-selectin in clathrin-coated pits of endothelial cells enhances neutrophil rolling.

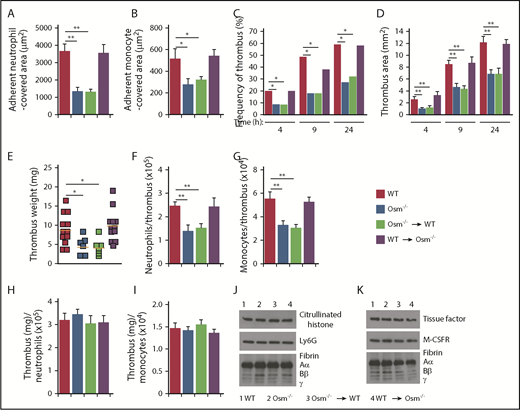

Interactions of neutrophil-derived OSM with gp130-containing receptors on endothelial cells increase P-selectin–dependent thrombosis in flow-restricted veins

We explored the contribution of neutrophil-derived OSM in a mouse model of P-selectin–dependent deep vein thrombosis. In this model, a ligature reduces blood flow in the IVC by ∼90%, causing a thrombus to develop upstream of the stenosis in ∼50% of vessels.42-44,52 Histamine released from mast cells mobilizes P-selectin to the endothelial surface of the IVC, which initiates rolling of neutrophils and monocytes.53 Signaling through PSGL-1 and chemokine receptors on the rolling cells triggers integrin-dependent arrest.42,52 Adherent neutrophils release DNA/histone-rich neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), and monocytes express tissue factor.42,52 These mediators trigger thrombus formation. Spinning-disk intravital microscopy 3 hours after IVC ligation revealed extensive firm adhesion of neutrophils and monocytes in WT mice and in mice lacking OSM only in nonhematopoietic cells (Figure 5A-B). In contrast, significantly fewer neutrophils and monocytes adhered in mice with global deletion of OSM and in mice lacking OSM only in hematopoietic cells. Because monocytes do not express OSM, these data indicate that neutrophil-released OSM also enhances P-selectin–dependent rolling of monocytes, which then arrest through integrin-dependent mechanisms. Ultrasonography revealed markedly reduced thrombus formation and thrombus area during the first 24 hours after IVC ligation in mice lacking OSM globally or only in hematopoietic cells (Figure 5C-D). The weights of thrombi, collected 24 hours after ligation, and the number of neutrophils and monocytes per thrombus were also significantly reduced in these genotypes (Figure 5E-G). However, the thrombus weight per neutrophil or monocyte was equivalent in all genotypes (Figure 5H-I). Furthermore, immunoblots of thrombi revealed equivalent citrullinated histones (a component of NETs) and fibrin relative to the neutrophil marker Ly6G (Figure 5J), and equivalent tissue factor and fibrin relative to the monocyte marker M-CSFR (Figure 5K). These data demonstrate that neutrophil-derived OSM augments thrombosis by increasing P-selectin–dependent adhesion of neutrophils and monocytes in the flow-restricted IVC. It does not, however, further stimulate the prothrombotic activity of the adherent neutrophils or monocytes.

Neutrophil-derived OSM increases P-selectin–dependent thrombosis in flow-restricted veins. (A-B) Quantification of endothelial surface area covered with firmly adherent Ly6G+ neutrophils or M-CSFR+ monocytes using spinning-disk intravital microscopy, 3 hours after ligation of the IVC in mice of the indicated genotype. (C-D) Kinetics of thrombus development (frequency) and thrombus size (area) in the indicated genotype, measured by ultrasonography at the indicated times after ligation. (E) Thrombus weight in the indicated genotype 24 hours after ligation. Each symbol represents an individual thrombus. Horizontal red bars represent median values. (F-G) Number of Ly6G+ neutrophils or M-CSFR+ monocytes per thrombus 24 hours after ligation in the indicated genotype, as measured by flow cytometry. (H-I) Normalized thrombus weight per Ly6G+ neutrophil or M-CSFR+ monocyte. (J) Western blot of thrombus lysates probed with antibodies to fibrin, Ly6G, and citrullinated histone. (K) Western blot of thrombus lysates probed with antibodies to fibrin, M-CSFR, and tissue factor. The Aα, Bβ, and γ chains of fibrin are marked. The data in panels A-I represent the mean ± SEM from 5 to 12 mice in each group. The data in panels J-K are representative of 3 experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Neutrophil-derived OSM increases P-selectin–dependent thrombosis in flow-restricted veins. (A-B) Quantification of endothelial surface area covered with firmly adherent Ly6G+ neutrophils or M-CSFR+ monocytes using spinning-disk intravital microscopy, 3 hours after ligation of the IVC in mice of the indicated genotype. (C-D) Kinetics of thrombus development (frequency) and thrombus size (area) in the indicated genotype, measured by ultrasonography at the indicated times after ligation. (E) Thrombus weight in the indicated genotype 24 hours after ligation. Each symbol represents an individual thrombus. Horizontal red bars represent median values. (F-G) Number of Ly6G+ neutrophils or M-CSFR+ monocytes per thrombus 24 hours after ligation in the indicated genotype, as measured by flow cytometry. (H-I) Normalized thrombus weight per Ly6G+ neutrophil or M-CSFR+ monocyte. (J) Western blot of thrombus lysates probed with antibodies to fibrin, Ly6G, and citrullinated histone. (K) Western blot of thrombus lysates probed with antibodies to fibrin, M-CSFR, and tissue factor. The Aα, Bβ, and γ chains of fibrin are marked. The data in panels A-I represent the mean ± SEM from 5 to 12 mice in each group. The data in panels J-K are representative of 3 experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01.

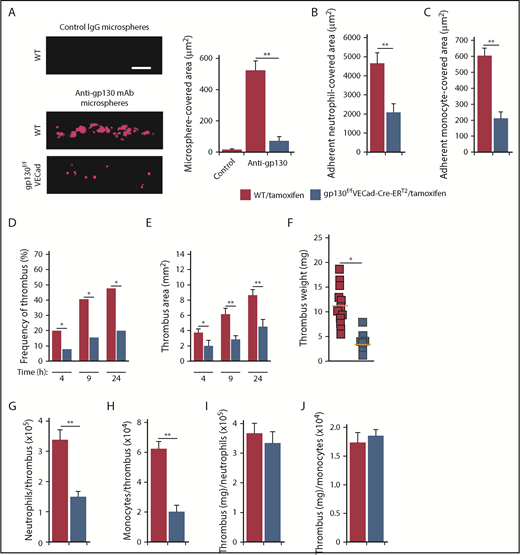

To determine whether neutrophil-derived OSM promoted deep vein thrombosis through gp130-dependent signaling in endothelial cells, we administered tamoxifen to WT or gp130flox/floxVECad-Cre-ERT2 mice. Spinning-disk microscopy of the IVC confirmed deletion of gp130 in endothelial cells of gp130flox/floxVECad-Cre-ERT2 mice (Figure 6A). Compared with tamoxifen-treated WT mice, significantly fewer neutrophils and monocytes adhered in tamoxifen-treated gp130flox/floxVECad-Cre-ERT2 mice (Figure 6B-C). Ultrasonography showed markedly reduced thrombus formation and thrombus area during the first 24 hours after IVC ligation in tamoxifen-treated gp130flox/floxVECad-Cre-ERT2 mice (Figure 6D-E). The weights of thrombi collected 24 hours after ligation, and the number of neutrophils and monocytes per thrombus were also significantly reduced (Figure 6F-H). As with control and OSM-deficient mice, the thrombus weight per neutrophil or monocyte was similar in tamoxifen-treated WT and gp130flox/floxVECad-Cre-ERT2 mice (Figure 6I-J). Taken together, these data demonstrate that neutrophil-derived OSM triggers gp130-dependent signals in endothelial cells, which increase P-selectin–dependent leukocyte adhesion and thrombosis in the flow-restricted IVC.

Signaling through gp130-containing receptors on endothelial cells increases P-selectin–dependent thrombosis in flow-restricted veins. (A) Representative images of gp130 expression (red) in the IVC of tamoxifen-treated WT or gp130flox/floxVECad-Cre-ERT2 mice obtained with spinning-disk intravital microscopy. Fluoresbrite red microspheres coated with anti-gp130 mAb or isotype control mAb were injected IV into tamoxifen-treated WT or gp130flox/floxVECad-Cre-ERT2 mice 20 minutes before exposing the IVC. Top, IVC of tamoxifen-treated WT mouse injected with isotype control mAb-coated beads; middle, IVC of tamoxifen-treated WT mouse injected with anti-gp130 mAb-coated beads; bottom, IVC of tamoxifen-treated gp130flox/floxVECad-Cre-ERT2 mouse injected with anti-gp130 mAb-coated beads. The graph at right indicates quantification of the covered area of adherent microspheres with digital image-analysis software. The data represent the mean ± SEM from 5 mice. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B-C) Quantification of endothelial surface area covered with firmly adherent Ly6G+ neutrophils or M-CSFR+ monocytes, 3 hours after ligation of the IVC. (D-E) Kinetics of thrombus development (frequency) and thrombus size (area) in mice of the indicated genotype, measured by ultrasonography at the indicated times after ligation. (F) Thrombus weight in the indicated genotype 24 hours after ligation. Each symbol represents an individual thrombus. Horizontal red bars represent median values. (G-H) Number of Ly6G+ neutrophils or M-CSFR+ monocytes per thrombus 24 hours after ligation in the indicated genotype, as measured by flow cytometry. (I-J) Normalized thrombus weight per Ly6G+ neutrophil or M-CSFR+ monocyte. The data represent the mean ± SEM from 5 to 12 mice in each group. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Signaling through gp130-containing receptors on endothelial cells increases P-selectin–dependent thrombosis in flow-restricted veins. (A) Representative images of gp130 expression (red) in the IVC of tamoxifen-treated WT or gp130flox/floxVECad-Cre-ERT2 mice obtained with spinning-disk intravital microscopy. Fluoresbrite red microspheres coated with anti-gp130 mAb or isotype control mAb were injected IV into tamoxifen-treated WT or gp130flox/floxVECad-Cre-ERT2 mice 20 minutes before exposing the IVC. Top, IVC of tamoxifen-treated WT mouse injected with isotype control mAb-coated beads; middle, IVC of tamoxifen-treated WT mouse injected with anti-gp130 mAb-coated beads; bottom, IVC of tamoxifen-treated gp130flox/floxVECad-Cre-ERT2 mouse injected with anti-gp130 mAb-coated beads. The graph at right indicates quantification of the covered area of adherent microspheres with digital image-analysis software. The data represent the mean ± SEM from 5 mice. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B-C) Quantification of endothelial surface area covered with firmly adherent Ly6G+ neutrophils or M-CSFR+ monocytes, 3 hours after ligation of the IVC. (D-E) Kinetics of thrombus development (frequency) and thrombus size (area) in mice of the indicated genotype, measured by ultrasonography at the indicated times after ligation. (F) Thrombus weight in the indicated genotype 24 hours after ligation. Each symbol represents an individual thrombus. Horizontal red bars represent median values. (G-H) Number of Ly6G+ neutrophils or M-CSFR+ monocytes per thrombus 24 hours after ligation in the indicated genotype, as measured by flow cytometry. (I-J) Normalized thrombus weight per Ly6G+ neutrophil or M-CSFR+ monocyte. The data represent the mean ± SEM from 5 to 12 mice in each group. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Discussion

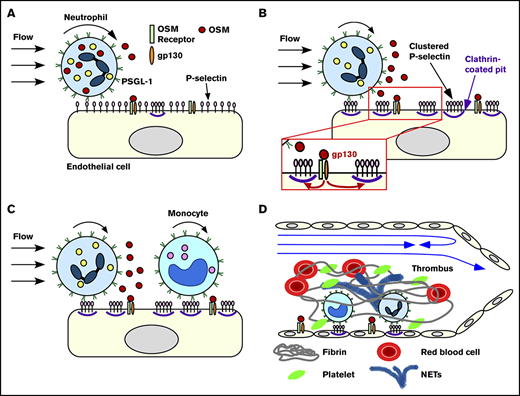

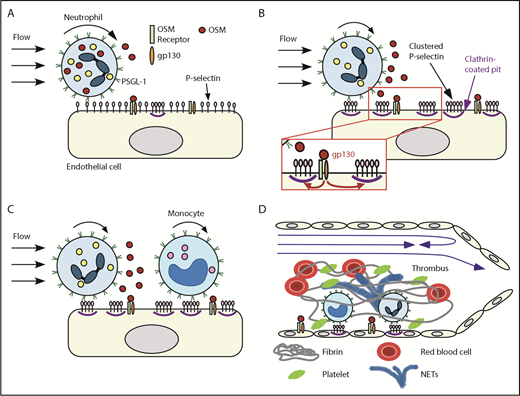

We have demonstrated that rolling neutrophils secrete OSM as they engage P-selectin in venules or veins. The secreted OSM triggers gp130-dependent signals in endothelial cells that cluster P-selectin in clathrin-coated pits and markedly enhance its adhesive function. This signaling loop amplifies recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes during the earliest stages of inflammation and deep vein thrombosis (Figure 7).

Neutrophil-derived OSM triggers endothelial gp130 signaling that enhances P-selectin–dependent leukocyte adhesion and thrombosis. Neutrophils rolling on P-selectin release OSM (A) that triggers gp130 signaling in endothelial cells (B). Signaling through gp130 augments clustering of P-selectin in clathrin-coated pits, which enhances rolling of neutrophils and monocytes and facilitates integrin-dependent arrest (B-C). In flow-restricted veins, the increased leukocyte adhesion promotes thrombosis (D). See “Discussion” for details.

Neutrophil-derived OSM triggers endothelial gp130 signaling that enhances P-selectin–dependent leukocyte adhesion and thrombosis. Neutrophils rolling on P-selectin release OSM (A) that triggers gp130 signaling in endothelial cells (B). Signaling through gp130 augments clustering of P-selectin in clathrin-coated pits, which enhances rolling of neutrophils and monocytes and facilitates integrin-dependent arrest (B-C). In flow-restricted veins, the increased leukocyte adhesion promotes thrombosis (D). See “Discussion” for details.

We confirmed that OSM is expressed by neutrophils but not by monocytes or lymphocytes under basal conditions. Neutrophil OSM is stored in gelatinase and secretory granules,23,24 which have a lower signaling threshold for secretion than for azurophilic and specific granules.54 PSGL-1–dependent adhesion of neutrophils to immobilized P-selectin, particularly under variable shear conditions, was sufficient to induce secretion of OSM. Interactions of P-selectin with PSGL-1 on neutrophils mediate both adhesion and signaling.3,26,42,55 Oligomeric or immobilized P-selectin or anti–PSGL-1 antibodies can induce signals in the absence of shear stress.56,57 Force-dependent interactions under shear stress might amplify signaling by increasing the number of P-selectin/PSGL-1 bonds or by other mechanisms.58

Neutrophil-released OSM signaled through gp130-containing receptors on endothelial cells. These receptors are most likely heterodimers of gp130 with the OSM receptor β subunit, because mouse OSM binds only to this receptor.59 Human OSM might also signal through heterodimers of gp130 with the leukemia inhibitory factor receptor α subunit.16 Conditional deletion of the gp130 allele in endothelial cells of adult mice reduced P-selectin–dependent rolling like acute injection of anti-gp130 antibody. We observed the same phenotype in mice injected with anti-OSM antibody or in mice lacking OSM in hematopoietic cells. Thus, the immediate consequence of deleting endothelial cell gp130 in adult mice is the inability to respond to OSM. By contrast, deleting endothelial cell gp130 during development increases postnatal CXCL1 expression, facilitating leukocyte arrest but impairing transendothelial migration.28

It was previously shown that exogenous OSM, within 15 minutes, stimulates HUVECs to support P-selectin–dependent adhesion of neutrophils.20 This effect was ascribed to mobilization of P-selectin from Weibel-Palade bodies to the plasma membrane, although the surface density of P-selectin was not measured. We found that OSM did not change the surface density of P-selectin on HUVECs before or after stimulation with histamine, which does mobilize P-selectin. Instead, it augmented clustering of P-selectin in clathrin-coated pits. Clathrin-mediated clustering of P-selectin on transfected cells or on HUVECs markedly enhances its ability to support leukocyte rolling under flow.13,14 Clustering stabilizes rolling by slowing the dissociation rates of P-selectin/PSGL-1 bonds. Like histamine, thrombin not only induces mobilization of P-selectin to the endothelial cell surface, but it also diminishes clathrin-dependent clustering of P-selectin and thus impairs rolling.14 In contrast, OSM facilitated rolling, not by mobilizing P-selectin, but by increasing P-selectin clustering. The effect was dramatic. In trauma-stimulated venules, blocking or deleting OSM or gp130 markedly reduced the numbers of neutrophils rolling on P-selectin and increased the velocities of those still rolling. In flow-restricted veins, it also reduced P-selectin–dependent rolling of monocytes, which do not express OSM. Thus, neutrophil-released OSM regulates P-selectin–dependent rolling of other leukocytes. In vitro, clathrin-mediated clustering has a greater effect on P-selectin function at lower surface densities.13 Activated platelets express significantly higher surface densities of P-selectin,60,61 which may lessen the requirement for clustering.

Our results document a paracrine signaling mechanism by which OSM released from neutrophils rolling on P-selectin stimulates gp130-containing receptors on endothelial cells. The effect is to greatly facilitate P-selectin–dependent rolling during the earliest stages of inflammation. Neutrophils rolling on E-selectin, which endothelial cells express later during inflammation, release cytosolic myeloid-related proteins 8 and 14 that signal through Toll-like receptor 4 on neutrophils by an autocrine mechanism.62 The effect is to activate β2 integrins that mediate slow rolling and arrest. Rolling neutrophils also secrete 2 other proteins, pentraxin 3 and myeloperoxidase, which influence adhesion by nonsignaling mechanisms. Pentraxin 3 decreases rolling by competitively binding to P-selectin on endothelial cells.63 Myeloperoxidase enhances adhesion by attenuating the electrostatic repulsion between the negatively charged glycocalyces of neutrophils and endothelial cells.64 Pentraxin 3 is stored in specific granules,65 and myeloperoxidase is stored in azurophilic granules.66 Both types of granules are less readily mobilized than the gelatinase and secretory granules that store OSM,54 and likely exert their effects later during inflammation. OSM and other neutrophil-derived proteins act in concert with mediators from other cells to promote and then limit neutrophil adhesion during inflammation.41,67,68 Furthermore, neutrophils release OSM after migrating outside blood vessels,69-71 and some agonists cause neutrophils to synthesize more OSM.23,71 In turn, extravascular OSM modulates the expression of chemokines that regulate leukocyte recruitment.69,72

Neutrophil-derived OSM was a major contributor to P-selectin–mediated thrombosis in flow-restricted IVCs of mice. In this clinically relevant model, P-selectin/PSGL-1 interactions initiate rolling of neutrophils and monocytes.42,52 Chemokines such as CXCL1 and CCL2 accumulate on the venular surface.42,52 Cooperative signaling through PSGL-1 and CXCR2 causes rolling neutrophils to arrest and to produce procoagulant NETs.42 Related cooperative mechanisms likely signal rolling monocytes to arrest and to express procoagulant tissue factor. OSM deficiency reduced thrombus formation by impairing P-selectin–dependent rolling of neutrophils and monocytes, which decreased integrin-dependent arrest. However, it did not interfere with prothrombotic signaling in the remaining adherent cells. Overall, our results demonstrate that neutrophil-released OSM influences endothelial cell function in both physiological and pathological conditions. These insights may offer new approaches to treat inflammatory and thrombotic diseases.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Atsushi Miyajima for Osm−/− mice, Cindy Carter for technical assistance, and Ben Fowler and Justin Willige for assistance with confocal microscopy.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant HL034363 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and grant GM114731 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Authorship

Contribution: H.S. and R.P.M. conceived the study; H.S., T.Y., and Z.L. performed experiments; all authors interpreted data; and H.S., T.Y., and R.P.M. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: R.P.M. is a cofounder of Selexys Pharmaceuticals, now part of Novartis AG, and of Tetherex Pharmaceuticals. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for H.S. is Advanced Cardiac Care, Nazih Zudhi Transplant Institute, INTEGRIS Baptist Medical Center, Oklahoma City, OK.

Correspondence: Rodger P. McEver, Cardiovascular Biology Research Program, Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, 825 NE 13th St, Oklahoma City, OK 73104; e-mail: rodger-mcever@omrf.org.

References

Author notes

H.S. and T.Y. contributed equally to this study.