Key Points

In response to TLR stimulation, monocytes from MPN patients persistently produce TNF-α.

This aberrant TNF-α response is due to a blunted response to the feedback inhibitor IL-10 and is not a direct consequence of JAK2V617F.

Abstract

Patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) have high levels of inflammatory cytokines, some of which drive many of the debilitating constitutional symptoms associated with the disease and may also promote expansion of the neoplastic clone. We report here that monocytes from patients with MPN have defective negative regulation of Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling that leads to unrestrained production of the inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) after TLR activation. Specifically, monocytes of patients with MPN are insensitive to the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin 10 (IL-10) that negatively regulates TLR-induced TNF-α production. This inability to respond to IL-10 is a not a direct consequence of JAK2V617F, as the phenotype of persistent TNF-α production is a feature of JAK2V617F and wild-type monocytes alike from JAK2V617F-positive patients. Moreover, persistent TNF-α production was also discovered in the unaffected identical twin of a patient with MPN, suggesting it could be an intrinsic feature of those predisposed to acquire MPN. This work implicates sustained TLR signaling as not only a contributor to the chronic inflammatory state of MPN patients but also a potential predisposition to acquire MPN.

Introduction

Myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) is a chronic hematologic malignancy resulting from the somatic acquisition of a mutation that leads to constitutive activation of thrombopoietin receptor (MPL) signaling (JAK2V617F, CALR, MPL) and subsequent expansion of mature myeloid cells. Patients with MPN have elevated serum inflammatory cytokine concentrations,1-3 and this chronic inflammatory state is responsible for the debilitating constitutional symptoms characteristic of this disease.4 Treatment with the JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib, the only drug approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for MPN, reduces inflammatory cytokines coincident with improvement of constitutional symptoms.5,6 Inflammation is also critical for MPN progression. For example, we have previously identified a central role for the inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in the clonal expansion of the JAK2V617F mutant clone.7 JAK2V617F endows on hematopoietic progenitors TNF-α resistance, giving the JAK2V617F clone a selective advantage over their TNF-α sensitive JAK2WT counterparts in high TNF-α environments. Therefore, targeting excessive TNF-α production should be therapeutically beneficial in MPN, and understanding the mechanism that drives excessive TNF-α production in MPN will guide strategies to target TNF-α in this disease.

TNF-α is classically produced by monocytes after stimulation of Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which are crucial pattern recognition receptors for microbial products.8 Tightly regulated negative feedback TLR signaling,9 orchestrated by the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin 10 (IL-10),10,11 is critical to avoid persistent production of inflammatory cytokines after TLR stimulation. Because of its integral role in inflammation and TNF-α production, we hypothesized that exaggerated TLR signaling contributes to the increased TNF-α seen in MPN. Here, we demonstrate that primary monocytes from patients with MPN have aberrantly prolonged production of TNF-α in response to TLR activation, and that this results from blunted IL-10R signaling. We also aim to address whether the excessive TNF-α production is a direct cell autonomous consequence of JAK2V617F or an intrinsic innate immune feature that predates the development of MPN.

Methods

Patients

Peripheral blood was obtained from patients with polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), myelofibrosis (MF), MPN family members, or normal volunteers. All participants gave their informed consent for the studies conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of California, Irvine; Portland Veteran’s Affairs Medical Center; and Oregon Health & Science University.

CD14+ Monocyte Isolation

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated by density gradient, using Ficoll-paque PLUS (GE Healthcare), and red blood cells were lysed by ammonium chloride potassium lysing buffer. Monocytes were selected using human CD14 MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec) and MACS separation column per the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with penicillin, streptomycin, l-glutamine and 10% fetal bovine serum and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 humidified incubator.

Jak2V617F knock-in bone marrow-derived macrophages

The Jak2V617F knock-in mouse model was a gift from Ann Mullally (Dana Farber Cancer Institute).12 Normal C57BL/6J and Jak2V617F knock-in mouse bone marrow cells were cultured on tissue-culture treated dishes in macrophage differentiation medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with penicillin, streptomycin, l-glutamine; 10% fetal bovine serum; and 10 ng/mL recombinant murine macrophage colony-stimulating factor [PeproTech]) to generate bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs). Cells were incubated for 6 days at 37° in 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator, and then nonadherent cells were removed by repetitive washing.

TNF-α and IL-10 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Human CD14+ monocytes or murine BMDMs were stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS; InvivoGen), R848 (InvivoGen), or LPS and recombinant human or mouse IL-10 (PeproTech) for the indicated time. For studies measuring the effect of IL-10 or IL-10R blocking antibody on LPS-induced TNF-α production, human recombinant IL-10 (PeproTech) or hIL-10R blocking antibody (BioLegend) were added to cells simultaneously with LPS. Supernatants were collected and centrifuged to remove cellular debris. Samples were flash-frozen and stored at −80°C until quantification. TNF-α and IL-10 were measured using human or mouse Ready-SET-Go! enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (eBioscience) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Measurement of intracellular TNF-α

Human CD14+ monocytes or murine BMDMs were stimulated with LPS for the indicated time and treated with brefeldin A (BD Biosciences) for the final 4 hours of stimulation. Cells were collected and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde followed by permeabilization with 0.005% saponin in phosphoflow staining buffer (phosphate-buffered saline + 0.5% bovine serum albumin). Human CD14+ monocytes were stained with PE-conjugated TNF-α antibody (BD Biosciences) and fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated CD14 antibody (BioLegend). Murine BMDMs were stained with PE-conjugated TNF-α antibody (eBioscience) and PerCP/Cy5.5 F4/80 antibody (BioLegend). Cells were analyzed on a BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer.

Phosphoflow

Fresh whole peripheral blood was stimulated with LPS, R848, or recombinant human IL-10 for 15 minutes or 2 hours and then fixed in 1.6% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with methanol. R848- and LPS-stimulated cells were stained with APC CD33 (BioLegend) and fluorescein isothiocyanate CD14 (BD Biosciences) to identify monocytes along with PE-conjugated phospho-p38 (pT180/pY182). IL-10-stimulated cells were stained with APC CD33 (BioLegend) and fluorescein isothiocyanate CD14 (BD Biosciences) to identify monocytes along with PE-conjugated pStat3 (pY705) antibody. All phosphoflow antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences. Cells were analyzed on a BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer.

SOCS3 expression

The expression of Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling 3 (SOCS3), which is induced in response to IL-10 stimulation, was quantified in CD14+ monocytes. The monocytes were stimulated with recombinant human IL-10 (PeproTech) for 15 minutes, 1 hour, or 2 hours at 1, 5, 10, or 50 ng/mL. Cells were pelleted and washed with PBS before lysis in TriPure reagent (Roche). RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s instructions and reverse-transcribed using the SuperScript VILO cDNA synthesis kit (Life Technologies). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed on a LightCycler 480 instrument (Roche) using Maxima SYBR Green quantitative PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher). SOCS3 primers were as follows: forward: 5′-CACTCTTCAGCATCTCTGTCG-3′; reverse: 5′-TCTCATTAGTTCAGCATTCCCG-3′. β-actin primers were as follows: forward: 5′-CATTGCCCGACAGGATGCAG-3′; reverse: 5′-CTCGTCATACTCCTGCTTGCTG-3′. Data were normalized to β-actin and analyzed via the Pfaffl method.

Quantitative JAK2V617F allele burden

CD14+ monocytes were stimulated with LPS for 4 or 10 hours and treated with brefeldin A for the final 4 hours of stimulation. Cells were stained for TNF-α, as described earlier. TNF-α+ and TNF-α− populations were sorted on a FACS Aria Fusion (BD Biosciences). DNA was extracted by direct lysis in buffer (10 mM Tris⋅HCl at pH 7.6, 50 mM NaCl, 6.25 mM MgCl2, 0.045% NP40, 0.45% Tween-20, 1 mg/mL proteinase K), followed by incubation at 56°C for 1 hour and 95°C for 15 minutes. Allele burden was determined using the ipsogen JAK2 MutaQuant kit (Qiagen), using a LightCycler480 (Roche). Data were analyzed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Sequencing of a patient with MPN and an identical twin

Next-generation sequencing was validated and performed in the Division of Molecular Pathology, Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, University of California, Irvine. DNA was isolated from peripheral blood, using a QIAamp DSP DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, GmbH). The targeted next-generation sequencing libraries were prepared from 100 ng DNA per sample, using the ArcherDX VariantPlex Myeloid (SK0123) workflow. The genes included on this panel are shown in supplemental Table 1. The resulting libraries were sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq instrument, using v2 chemistry (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Next, the FASTQ data files were analyzed on ArcherDX Suite Analysis software (v. 5.1.7) to identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), indels, structural rearrangements, and copy number variations.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. Data were analyzed using Student t tests, 1-way analysis of variance with Sidak’s post hoc analysis, 2-way analysis of variance with Sidak’s post hoc analysis, or 2-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc analysis where appropriate (GraphPad Prism).

Results

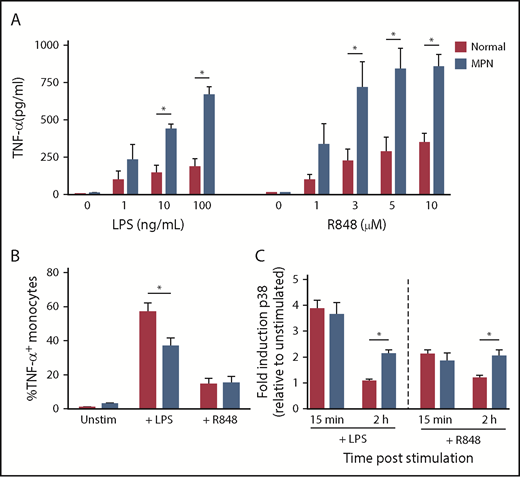

Patients with MPN produce more TNF-α in response to the TLR agonists

We measured TNF-α production by CD14+ monocytes stimulated with the TLR agonists LPS (TLR4) and R848 (TLR7/8), comparing patients with MPN and normal controls (Figure 1A). CD14+ cells were purified from fresh peripheral blood and incubated for 24 hours in the presence of increasing concentrations of TLR agonists. The concentration of TNF-α in the supernatant of monocytes of patients with MPN was higher than that of normal controls in response to both LPS and R848 (P ≤ .05).

Increased TNF-α production by MPN monocytes after stimulation with TLR agonists. (A) MPN (n = 2 PV, 2 ET, and 1 MF) and normal (n = 5) monocytes were stimulated with TLR agonists LPS or R848 at the concentrations shown. After 24 hours of culture, supernatant was harvested and TNF-α was measured by ELISA. (B) MPN (n = 8 PV, 3 ET, and 2MF) and normal (n = 8) monocytes were stimulated with 10 ng/mL LPS or 5 μM R848 and incubated with brefeldin A for 4 hours to prevent protein export. Intracellular staining for TNF-α was performed, and cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) MPN (n = 2 PV and 5 ET) and normal (n = 5) monocytes were stimulated with 10 ng/mL LPS or 5 μM R848 for 15 minutes or 2 hours before fixation and permeabilization. Cells were stained for phospho-p38 and analyzed on a flow cytometer. *P < .05.

Increased TNF-α production by MPN monocytes after stimulation with TLR agonists. (A) MPN (n = 2 PV, 2 ET, and 1 MF) and normal (n = 5) monocytes were stimulated with TLR agonists LPS or R848 at the concentrations shown. After 24 hours of culture, supernatant was harvested and TNF-α was measured by ELISA. (B) MPN (n = 8 PV, 3 ET, and 2MF) and normal (n = 8) monocytes were stimulated with 10 ng/mL LPS or 5 μM R848 and incubated with brefeldin A for 4 hours to prevent protein export. Intracellular staining for TNF-α was performed, and cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) MPN (n = 2 PV and 5 ET) and normal (n = 5) monocytes were stimulated with 10 ng/mL LPS or 5 μM R848 for 15 minutes or 2 hours before fixation and permeabilization. Cells were stained for phospho-p38 and analyzed on a flow cytometer. *P < .05.

Next, we compared the fraction of CD14+ monocytes that were actively producing TNF-α immediately after TLR ligation in patients with MPN vs normal controls. We stimulated MPN and normal control peripheral blood mononuclear cells with the LPS or R848 for 4 hours along with brefeldin A to retain TNF-α inside the cell, and then used intracellular flow cytometry to quantify the percentage of CD14+ monocytes that were TNF-α+ (Figure 1B). In unstimulated and R848-stimulated cells, there was no difference in the percentage of TNF-α+ CD14+ monocytes in MPN and normal controls (P > .05). Surprisingly, normal controls had a higher fraction of TNF-α+ cells than patients with MPN after LPS stimulation (P = .0001). We also measured TNF-α production using ELISA at early points (4 hours) after LPS stimulation and found no difference in the amount of TNF-α produced by MPN vs normal controls (supplemental Figure 1). Furthermore, patients with MPN and normal controls have a similar fraction of CD14+CD16+ proinflammatory monocytes (supplemental Figure 2). Thus, the increased TNF-α production in response to TLR ligation cannot be explained by an increased fraction of monocytes actively producing TNF-α immediately after stimulation, but instead may be a result of persistent TNF-α production at later points after stimulation.

Sustained activation of TLR signaling pathway in MPN monocytes

The mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways are key signaling intermediates in the cellular response to TLR stimulation. Activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is necessary for production of TNF-α after LPS stimulation.13 Therefore, we next quantified induction of phosphorylated p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in CD14+ monocytes from MPN vs normal controls 15 minutes and 2 hours after stimulation with LPS and R848 using phosphoflow (Figure 1C). At 15 minutes, both LPS and R848 induced an equivalent-fold induction of phospho-p38 in MPN and normal controls, demonstrating that initial signaling after TLR stimulation is not exaggerated in MPN. At 2 hours after stimulation with LPS and R848, however, phosphorylation of p38 was maintained or even increased in patients with MPN, whereas at 2 hours after stimulation, phosphorylation of p38 returned to baseline in normal controls. These data suggest that failure to dampen TLR signaling may be responsible for the persistent TNF-α production after TLR stimulation in MPN.

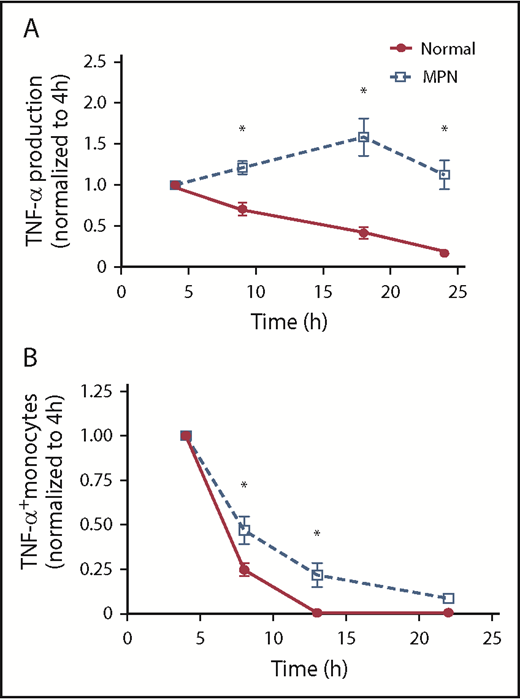

Persistent production of TNF-α by MPN patient monocytes after TLR ligation

We next compared the tempo of TNF-α production in MPN vs normal controls after TLR stimulation. We stimulated monocytes with LPS and quantified TNF-α in the supernatant at 4, 9, 18, and 24 hours later. The concentration of TNF-α at 4 hours was normalized to 1 for each patient to more easily visualize changes over time. In normal controls, the concentration of TNF-α was greatest at 4 hours but then consistently declined over time; in patients with MPN, however, the concentration of TNF increased over time, peaking at 18 hours post-LPS and persisting even at 24 hours post-LPS (Figure 2A). We also performed intracellular flow cytometry at multiple points after LPS stimulation and found that monocytes from patients with MPN maintained a higher percentage of TNF-α+ monocytes at later points compared with normal controls (Figure 2B). Our observations that the exaggerated TNF-α production is seen at late but not early points after LPS stimulation implicates a defect in the TLR signaling negative feedback loop in patients with MPN.

MPN monocytes persistently produce high levels of TNF-α. (A) MPN (n = 7 PV, 5 ET, and 4 MF) and normal (n = 13) monocytes were stimulated with 10 ng/mL LPS for 4, 9,18, and 24 hours before harvesting supernatant for ELISA. The amount of TNF-α produced at 4 hours was normalized to 1. (B) MPN (n = 5 PV, 4 ET, and 2 MF) and normal (n = 6) monocytes were stimulated with 10 ng/mL LPS for 4, 8, 13, and 22 hours before harvesting for flow cytometry analysis. All samples were treated with brefeldin A for 4 hours before harvesting. The percentage of monocytes expressing TNF-α at 4 hours was normalized to 1. *P < .05.

MPN monocytes persistently produce high levels of TNF-α. (A) MPN (n = 7 PV, 5 ET, and 4 MF) and normal (n = 13) monocytes were stimulated with 10 ng/mL LPS for 4, 9,18, and 24 hours before harvesting supernatant for ELISA. The amount of TNF-α produced at 4 hours was normalized to 1. (B) MPN (n = 5 PV, 4 ET, and 2 MF) and normal (n = 6) monocytes were stimulated with 10 ng/mL LPS for 4, 8, 13, and 22 hours before harvesting for flow cytometry analysis. All samples were treated with brefeldin A for 4 hours before harvesting. The percentage of monocytes expressing TNF-α at 4 hours was normalized to 1. *P < .05.

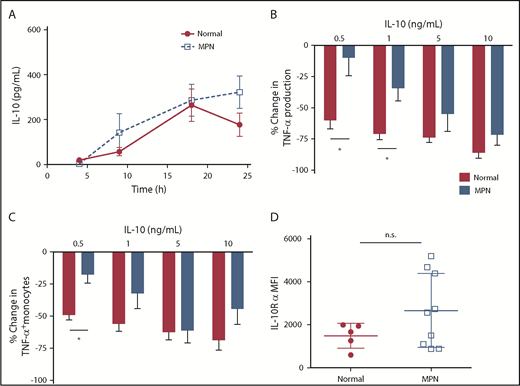

Blunted response to IL-10 by MPN monocytes is responsible for persistent TNF-α production in response to TLR ligation

IL-10 is produced in monocytes in response to LPS stimulation and acts as a negative feedback mechanism to dampen TNF-α production.14 To test the hypothesis that MPN monocytes produce less IL-10 in response to TLR activation, we measured IL-10 production by ELISA in MPN and normal control monocytes. We found that MPN monocytes produce at least as much IL-10 as normal controls at all points after LPS stimulation (Figure 3A). These data demonstrate that monocytes of patients with MPN produce adequate IL-10 in response to TLR stimulation, and yet do not dampen TNF-α production.

MPN monocytes produce adequate IL-10 but are less responsive to IL-10. (A) MPN (n = 4 PV, 4 ET, and 3 MF) and normal (n = 7) monocytes were stimulated with 10 ng/mL of LPS for 4, 9, 18, and 24 hours before harvesting supernatant for quantification of IL-10 via ELISA. (B) MPN (n = 2 PV and 3 ET) and normal (n = 6) monocytes were stimulated with 10 ng/mL LPS and various concentration of IL-10 simultaneously for 4 hours between harvesting of the supernatant for ELISA. The percentage change in TNF-α is measured by the difference in TNF-α production between adding IL-10 and without IL-10. (C) MPN (n = 2 PV and 3 ET) and normal (n = 5) monocytes were stimulated with 10 ng/mL LPS and various concentrations of IL-10 for 4 hours with brefeldin A before performing intracellular staining for TNF-α. The changes in TNF-α–positive monocytes are measured by the difference in monocytes expressing TNF-α between adding IL-10 and without IL-10. (D) The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of IL-10 receptor α is measured by gating on MPN (n = 4 PV, 3 ET, and 2 MF) and normal (n = 5) CD33high CD14+ monocytes from mononuclear cells, using flow cytometry analysis. *P < .05. ns, not significant.

MPN monocytes produce adequate IL-10 but are less responsive to IL-10. (A) MPN (n = 4 PV, 4 ET, and 3 MF) and normal (n = 7) monocytes were stimulated with 10 ng/mL of LPS for 4, 9, 18, and 24 hours before harvesting supernatant for quantification of IL-10 via ELISA. (B) MPN (n = 2 PV and 3 ET) and normal (n = 6) monocytes were stimulated with 10 ng/mL LPS and various concentration of IL-10 simultaneously for 4 hours between harvesting of the supernatant for ELISA. The percentage change in TNF-α is measured by the difference in TNF-α production between adding IL-10 and without IL-10. (C) MPN (n = 2 PV and 3 ET) and normal (n = 5) monocytes were stimulated with 10 ng/mL LPS and various concentrations of IL-10 for 4 hours with brefeldin A before performing intracellular staining for TNF-α. The changes in TNF-α–positive monocytes are measured by the difference in monocytes expressing TNF-α between adding IL-10 and without IL-10. (D) The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of IL-10 receptor α is measured by gating on MPN (n = 4 PV, 3 ET, and 2 MF) and normal (n = 5) CD33high CD14+ monocytes from mononuclear cells, using flow cytometry analysis. *P < .05. ns, not significant.

We then measured the ability of recombinant human IL-10 (rhIL-10) to dampen LPS-induced TNF-α production in patients with MPN and normal controls. A low concentration (0.5 ng/mL) of recombinant human IL-10 reduced LPS-induced TNF-α production by monocytes (Figure 3B), as well as the percentage of TNF-α+ monocytes (Figure 3C), by greater than 50% in normal controls, but only by 25% in patients with MPN. However, higher concentrations of IL-10 (5, 10 ng/mL) were able to reduce LPS-induced TNF-α production in normal and MPN monocytes to a similar degree. This suggests either that IL-10 produced by MPN monocytes is inherently ineffective or that IL-10R signaling in monocytes of patients with MPN is blunted in MPN compared with normal controls.

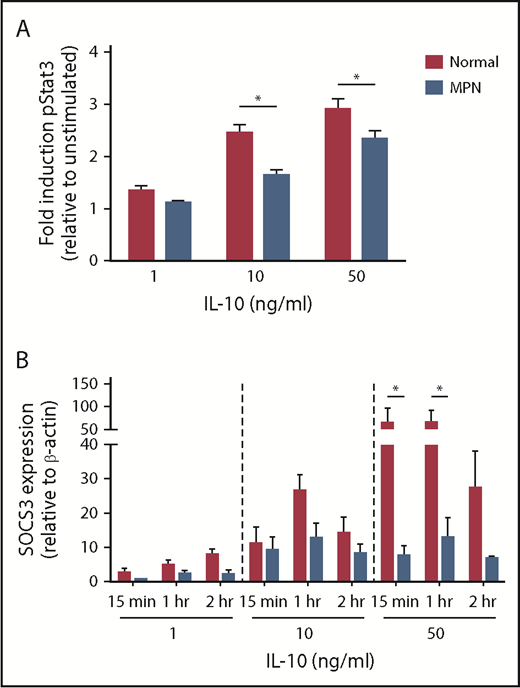

We measured IL-10R (CD210) cell surface expression in MPN and normal control monocytes by flow cytometry and did not find a decrease in IL-10R expression in patients with MPN (Figure 3D). To further evaluate IL-10R signaling in patients with MPN, we compared phospho-STAT3 (pSTAT3) activation of MPN vs normal control monocytes in response to IL-10 stimulation (Figure 4A). MPN monocytes did not induce pSTAT3 as robustly as normal controls in response to 10 ng/mL or 50 ng/mL IL-10 (P ≤ .01). Because SOCS3 expression is typically upregulated in response to IL-10R activation and dampens cytokine signaling,15,16 we also compared mRNA levels of SOCS3 in MPN vs normal control monocytes stimulated with IL-10 (Figure 4B). IL-10 at high concentrations did not induce expression of the SOCS3 gene as effectively in monocytes of patients with MPN as it did in normal controls. Taken together, our observations demonstrate that MPN monocytes have blunted IL-10R signaling resulting in unrestrained TLR-agonist-induced TNF-α production.

MPN monocytes have defective IL-10 signaling. (A) MPN (n = 9 PV, 6 ET, and 4 MF) and normal (n = 18) peripheral blood was stimulated for 15 minutes with IL-10 at the concentrations shown before fixation and permeabilization. CD33 high Cd14+ monocytes were gated for pStat3 and analyzed via flow cytometry. (B) MPN (n = 2 PV and 1ET) and normal (n = 3) monocytes were stimulated with IL-10 for 15 minutes, 1 hour, or 2 hours at the concentrations shown. SOCS3 mRNA was quantified by quantitative PCR and normalized to β-actin. *P < .05.

MPN monocytes have defective IL-10 signaling. (A) MPN (n = 9 PV, 6 ET, and 4 MF) and normal (n = 18) peripheral blood was stimulated for 15 minutes with IL-10 at the concentrations shown before fixation and permeabilization. CD33 high Cd14+ monocytes were gated for pStat3 and analyzed via flow cytometry. (B) MPN (n = 2 PV and 1ET) and normal (n = 3) monocytes were stimulated with IL-10 for 15 minutes, 1 hour, or 2 hours at the concentrations shown. SOCS3 mRNA was quantified by quantitative PCR and normalized to β-actin. *P < .05.

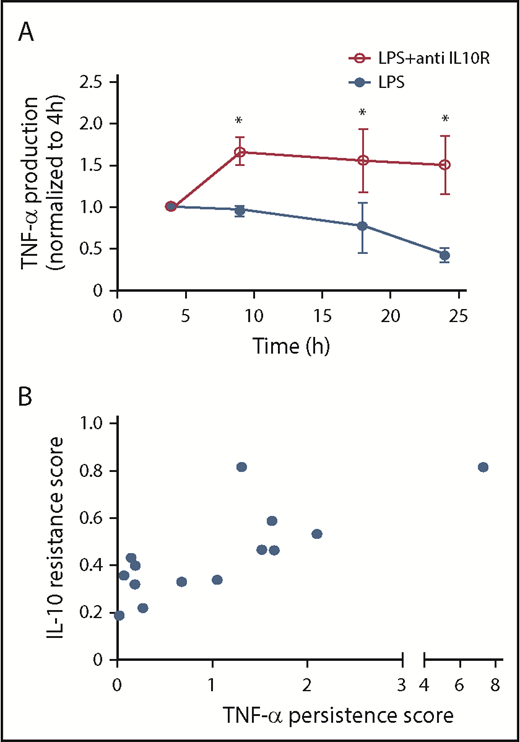

Blockade of IL-10R signaling induces persistent TNF-α production in normal control monocytes

We inhibited IL-10R signaling in normal control monocytes, using an IL-10R blocking antibody, and measured the effect on LPS-induced TNF-α production over time (Figure 5A). Whereas IL-10R blockade did not have an effect on LPS-induced TNF-α production at early points (4 hours) IL-10R blockade increased LPS-induced TNF-α production at later points, confirming our expectation that blocking IL-10R in normal monocytes should induce them to produce TNF with MPN-like kinetics.

IL-10R blocking is correlated to elevated TNF-α. (A) Normal monocytes (n = 2 PV, 2 ET, and 1 MF) were stimulated with 10 ng/mL LPS and with the addition of 1 μg/mL anti-IL-10R. Supernatants were collected for TNF-α quantification by ELISA at 4, 9, 18, and 24 hours after LPS stimulation. The amount of TNF-α produced at 4 hours was normalized to 1. (B) The correlation of TNF-α persistence score in MPN monocytes (n = 14) is defined as (TNF-α at 24 hours)/(TNF-α at 4 hours), and IL-10 resistance score is defined as (TNF-α of LPS + 1 ng/mL IL-10)/(TNF-α of LPS + 0 ng/mL IL-10). Pearson r = 0.7198, R2 = 0.5181. *P < .05.

IL-10R blocking is correlated to elevated TNF-α. (A) Normal monocytes (n = 2 PV, 2 ET, and 1 MF) were stimulated with 10 ng/mL LPS and with the addition of 1 μg/mL anti-IL-10R. Supernatants were collected for TNF-α quantification by ELISA at 4, 9, 18, and 24 hours after LPS stimulation. The amount of TNF-α produced at 4 hours was normalized to 1. (B) The correlation of TNF-α persistence score in MPN monocytes (n = 14) is defined as (TNF-α at 24 hours)/(TNF-α at 4 hours), and IL-10 resistance score is defined as (TNF-α of LPS + 1 ng/mL IL-10)/(TNF-α of LPS + 0 ng/mL IL-10). Pearson r = 0.7198, R2 = 0.5181. *P < .05.

IL-10 resistance correlates with TNF-α persistence in patients with MPN

We found that the degree of TNF-α persistence after LPS stimulation, as well as the ability of IL-10 to dampen LPS-induced TNF-α production, was variable among patients with MPN, with some patients being extremely abnormal and others being closer to normal. We reasoned that if TNF-α persistence is a result of blunted IL-10R signaling, then those patients with less of an ability to respond to IL-10 should have more extreme TNF-α persistence. For each patient with MPN and normal control, we calculated the TNF-α persistence score, defined as ([TNF-α at 24 hours]/[TNF-α at 4 hours]), as well as the IL-10 resistance score, defined as ([TNF-α of LPS + 1 ng/mL IL-10]/[TNF-α of LPS + 0 ng/mL IL-10]; Figure 5B). We found that the TNF-α persistence score and the IL-10 resistance score had a Pearson correlation coefficient (r) of 0.72, demonstrating that the inability of IL-10 to reduce LPS-induced TNF-α production correlates with an increased amount of TNF-α at 24 hours compared with 4 hours, as would be expected if IL-10 resistance is responsible for the persistent TNF-α production in patients with MPN.

Persistent TNF-α production is a feature of both wild-type and JAK2V617F monocytes from JAK2V617F-positive patients

To determine whether the persistent TNF-α production after TLR ligation is driven by JAK2V617F, we sorted TNF-α+ and TNF-α− CD14+ monocytes from JAK2V617F-positive MPN patients at 4 and 10 hours after LPS stimulation and quantified the JAK2V617F allele burden in each population (Table 1). We reasoned that if persistent TNF-α was driven by JAK2V617F in a cell-intrinsic manner, then the JAK2V617F allele burden should be higher in the sorted TNF-α+ population compared with the sorted TNF-α− population at 10 hours after LPS stimulation (supplemental Figure 3). We found the JAK2V617F allele burden was similar in the TNF-α+ and TNF-α− fractions at both 4 and 10 hours poststimulation, demonstrating that both the wild-type and the JAK2V617F mutant monocytes from patients with MPN contribute to the persistent TNF-α production in patients with MPN. This suggests that JAK2V617F does not drive persistent TNF-α production after LPS stimulation in a cell autonomous manner. Instead, JAK2V617F mutant cells may induce this phenotype on neighboring cells, or alternatively, unrestrained TLR-agonist–induced TNF-α production could be an intrinsic feature of patients with MPN, and could potentially be a predisposing factor to acquire the disease.

JAK2V617F allele burden in TNF-α+ monocytes

| Patient . | 4 h . | 10 h . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α− . | TNF-α+ . | TNF-α− . | TNF-α+ . | |

| 192 | 92.21 | 57.52 | 85.58 | 82.65 |

| 228 | 63.66 | 57.92 | 90.01 | 78.10 |

| 232 | 34.88 | 42.66 | 53.13 | 51.90 |

| 252 | 94.84 | 90.50 | 66.20 | 63.45 |

| 255 | 20.95 | 76.86 | 75.24 | 80.23 |

| Patient . | 4 h . | 10 h . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α− . | TNF-α+ . | TNF-α− . | TNF-α+ . | |

| 192 | 92.21 | 57.52 | 85.58 | 82.65 |

| 228 | 63.66 | 57.92 | 90.01 | 78.10 |

| 232 | 34.88 | 42.66 | 53.13 | 51.90 |

| 252 | 94.84 | 90.50 | 66.20 | 63.45 |

| 255 | 20.95 | 76.86 | 75.24 | 80.23 |

MPN monocytes (n = 5) were stimulated with 10 ng/mL LPS for 4 or 10 hours in the presence of brefeldin A, and intracellularly stained for TNF-α. TNF-α+ cells were sorted and JAK2V617F allele burden was determined by quantitative PCR.

Expression of JAK2V617F does not induce persistent TNF-α production after TLR ligation

Next, we used Jak2V617F knock-in mice12 to more specifically test whether JAK2V617F induces persistent production of TNF-α after TLR stimulation. We isolated BMDMs from normal and Jak2V617F knock-in mice and stimulated them with LPS. Intracellular cytokine staining demonstrated that Jak2V617F knock-in macrophages do not produce TNF-α longer than wild-type macrophages in response to LPS stimulation (supplemental Figure 4). Therefore, the results of our murine studies provide additional support for the notion that the TNF-α production after TLR ligation we observe in patients with MPN is not directly driven by JAK2V617F, but instead, is a unique feature of patients with MPN.

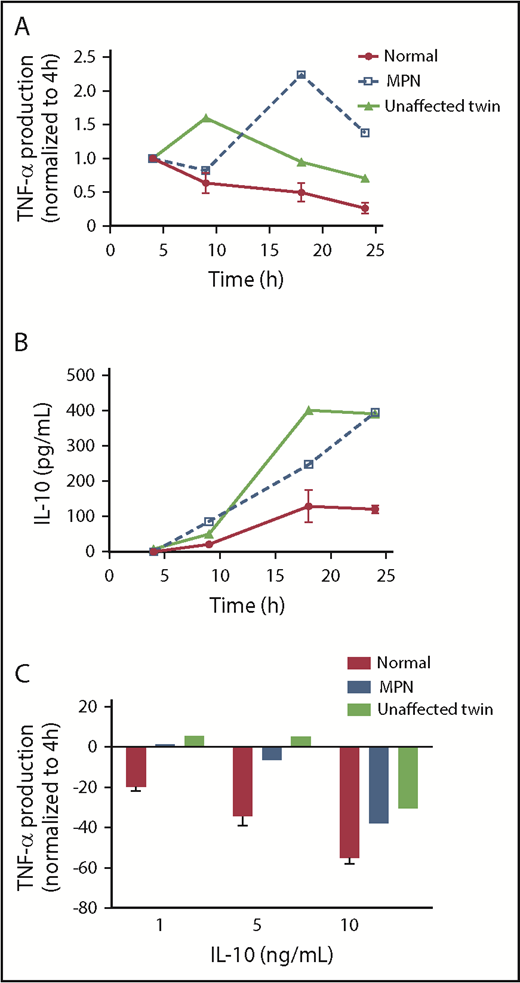

Persistent TNF-α production after TLR ligation in an unaffected identical twin of a patient with MPN

We obtained monocytes from identical twins discordant for MPN. One had JAK2V617F-positive PV and the other had no evidence of an MPN (normal blood counts, no detectable somatically acquired mutations on next-generation sequencing with a 75 myeloid targeted gene panel; details provided in supplemental Table 2). We stimulated monocytes from each twin and 2 age and sex matched normal control patients with LPS and measured TNF-α and IL-10 production over time by ELISA. We found that both the patient with PV and her unaffected twin had prolonged production of both TNF-α and IL-10 compared with the normal control (Figure 6A-B). We also observed that monocytes of the unaffected twin were less able to dampen LPS-induced TNF-α production in response to IL-10 (Figure 6C) than were normal monocytes. The conservation of prolonged TLR agonist-induced TNF-α production, as well as blunted IL-10 response in both the patient with PV and her unaffected identical twin, suggests that this abnormality predates the development of MPN and is not a consequence of the JAK2V617F mutation. That is, the aberrant monocyte response may be an intrinsic feature of those predisposed to acquire MPN.

Persistent TNF-α production and IL-10R signaling defects are found in an unaffected twin of a patient with MPN. (A) The monocytes of a patient with MPN, the unaffected twin of the patient, and normal donors (n = 2) were stimulated with 10 ng/mL LPS for 4, 9, 18, and 24 hours before supernatants were harvested for ELISA. The amount of TNF-α produced at 4 hours was normalized to 1. (B) The same supernatants harvested in A were taken for quantifying IL-10. (C) The monocytes of a patient with MPN, the unaffected twin of the patient, and normal donors (n = 2) were stimulated with 10 ng/mL LPS and various concentration of IL-10 simultaneously for 4 hours between harvesting of the supernatant for TNF-α ELISA. The percentage change in TNF-α is measured by the difference in TNF-α production between adding IL-10 and without IL-10.

Persistent TNF-α production and IL-10R signaling defects are found in an unaffected twin of a patient with MPN. (A) The monocytes of a patient with MPN, the unaffected twin of the patient, and normal donors (n = 2) were stimulated with 10 ng/mL LPS for 4, 9, 18, and 24 hours before supernatants were harvested for ELISA. The amount of TNF-α produced at 4 hours was normalized to 1. (B) The same supernatants harvested in A were taken for quantifying IL-10. (C) The monocytes of a patient with MPN, the unaffected twin of the patient, and normal donors (n = 2) were stimulated with 10 ng/mL LPS and various concentration of IL-10 simultaneously for 4 hours between harvesting of the supernatant for TNF-α ELISA. The percentage change in TNF-α is measured by the difference in TNF-α production between adding IL-10 and without IL-10.

Discussion

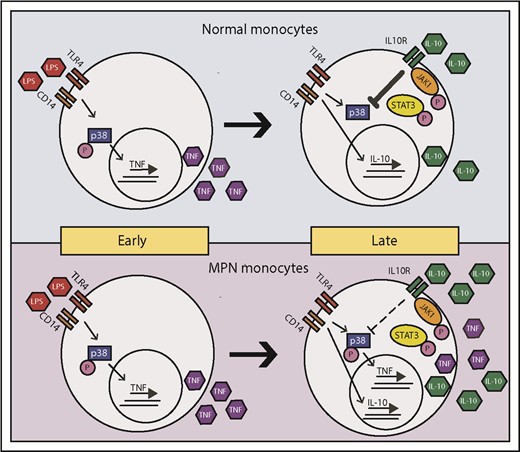

A chronic inflammatory state is a well-recognized feature of MPN, as derangement of inflammatory cytokines drives many of the debilitating symptoms associated with the disease4 and correlates with inferior prognosis.17 Inflammation likely plays an active role in MPN disease progression, giving the mutant cells a selective advantage over their wild-type counterparts.7 We find that patients with MPN produce TNF-α for a prolonged period after LPS stimulation. IL-10R signaling, which normally serves to dampen TNF-α production, is blunted in patients with MPN (Figure 7), and this could explain the prolonged TNF-α production we observe in patients with MPN. Interestingly, in some instances, patients with MPN appear to be less responsive to inflammatory stimuli initially (eg, MPN have a lower percentage of TNF+ monocytes at 4 hours in response to LPS, as shown in Figure 1B), and a generalized “sluggishness” to respond to stimuli may be a feature of patients with MPN. This persistent TNF-α production after LPS stimulation is not directly driven by JAK2V617F in a cell-intrinsic manner, as both wild-type and JAK2V617F mutant monocytes alike from patients with MPN persistently produce TNF-α after LPS stimulation (Table 1). It is possible that the presence of an MPN clone induces bystander normal cells to have prolonged TNF production. Although it is clear from mouse models that the presence of Jak2V617F cells induces inflammation,18,19 the specific phenotype of prolonged TNF-α production after TLR stimulation we observed in patients with MPN was not recapitulated in the knock-in Jak2V617F model (supplemental Figure 4). Furthermore, persistent TNF-α production in both a patient with PV and her unaffected identical twin suggests that prolonged TLR signaling may predate the development of MPN and could possibly play a contributory role in MPN disease development. To address this question, we are currently evaluating TLR signaling in a larger cohort of unaffected family members of patients with MPN.

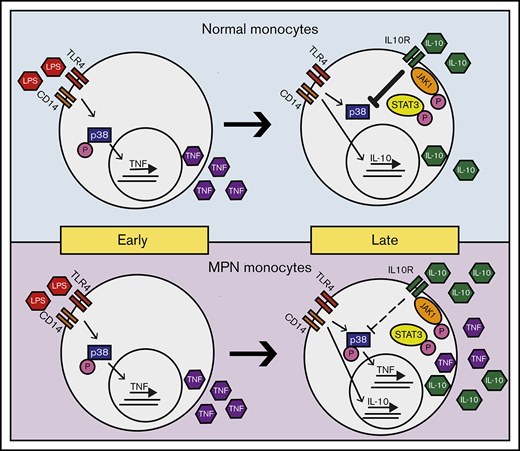

Model of LPS-induced inflammation in normal and MPN monocytes. MPN and normal monocytes produce a similar level of TNF-α in early times on LPS stimulation. Normal monocytes respond to IL-10 inhibition to abolish TNF-α production in late times, whereas MPN monocytes have a blunted response to IL-10 inhibition resulting in an overproduction of TNF-α.

Model of LPS-induced inflammation in normal and MPN monocytes. MPN and normal monocytes produce a similar level of TNF-α in early times on LPS stimulation. Normal monocytes respond to IL-10 inhibition to abolish TNF-α production in late times, whereas MPN monocytes have a blunted response to IL-10 inhibition resulting in an overproduction of TNF-α.

There is a growing body of evidence linking a genetic predisposition to chronic inflammation with MPN,20 suggesting that certain types of chronic inflammation may predispose people to MPN. Patients with MPN and their family members have an increased incidence of autoimmune diseases.21,22 Genome-wide association studies of MPN and inflammatory diseases have identified associations with the same genes. For example, the JAK2 SNP rs10758669, a SNP that tags the 46/1 haplotype associated with JAK2V617F mutated MPN,23-25 was also identified to be associated with Crohn’s disease.26 It has been proposed that the JAK2 46/1 haplotype results in an augmented response to cytokine stimulation, leading to increased inflammation.27 In addition, SNPs in SH2B3 (Lnk) are associated with MPN,25 as well as multiple sclerosis.28

We have found blunted IL-10R signaling in patients with MPN, as well as the unaffected twin of a patient with MPN, supporting the idea that blunted IL-10R signaling may be a feature of those predisposed to acquire MPN. Genetic loss of IL-10R signaling leads to inflammatory disease in both humans and mouse models. IL-10-deficient mice develop chronic enterocolitis.11 In humans, mutations in IL-10R cause early onset inflammatory bowel disease29 with persistent LPS-induced TNF-α production, the inability of IL-10 to reduce LPS-induced TNF-α production, and failure to upregulate SOCS3. Interestingly, patients with MPN have a higher rate and absolute risk for inflammatory bowel disease,30 linking these 2 disease entities with potentially common predispositions. Monocytes from individuals carrying specific IL-10R variants are less sensitive to IL-10-mediated inhibition of TNF-α production,31 reminiscent of our results in patients with MPN. It is conceivable that dampened IL-10R signaling could lead to both a predisposing factor common to both inflammatory bowel disease and MPN. Moreover, restoration of IL-10R signaling in MPN could potentially be of therapeutic benefit by normalizing excessive inflammatory cytokine production.

In addition to the chronic inflammation resulting from dampened IL-10R signaling, it is likely that the prolonged TLR signaling we observe in MPN monocytes extends to other immune cell populations, including hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). TLR agonists such as LPS induce hematopoietic stem cell cycling,32 and chronic TLR signaling causes proliferative stress, which exhausts HSCs.33-35 Although IL-10’s specific role in the response of HSC to TLR ligation has not been elucidated, it is conceivable that IL-10 plays a direct role in the negative regulation of TLR signaling in HSCs, just as it does in monocytes. Dysfunctional IL-10 signaling in monocytes leads to persistent TNF-α production after TLR ligation, and dysfunctional IL-10 signaling in HSC may lead to persistence of proliferative stress in HSCs after TLR ligation, resulting in accelerated aging of HSC. In support of this notion, HSCs from IL-10 knockout mice have inferior long-term reconstitution potential, and addition of IL-10 to in vitro cultured wild-type HSCs enhances their reconstitution potential.36 Hence, subtle dampening of IL-10R signaling could theoretically lead to accelerated HSC aging not only because it induces chronic TNF-α production but also because of direct effects on the response of HSCs to TLR agonists. Further studies should examine whether dampening of IL-10R signaling negatively affects the fitness of wild-type, but not JAK2V617F, HSC, affording JAK2V617F HSC a selective advantage in this context.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Department of Defense Career Development Award (A.G.F.), an MPN Research Foundation Challenge Award (A.G.F.), and the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (UL1 TR001414) (A.G.F.).

Authorship

Contribution: H.Y.L. and A.G.F designed research, performed research, analyzed data, produced figures, and wrote the paper; S.J.M. and M.R.G. performed research, analyzed data, and edited paper; and S.A.B., B.M.C., T.K.N., and N.H. performed research and analyzed data.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Angela G. Fleischman, Division of Hematology/Oncology, Department of Medicine, Irvine Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of California, Irvine, 839 Health Sciences Rd, Sprague Hall 126, Irvine, CA 92617; e-mail: agf@uci.edu.