Key Points

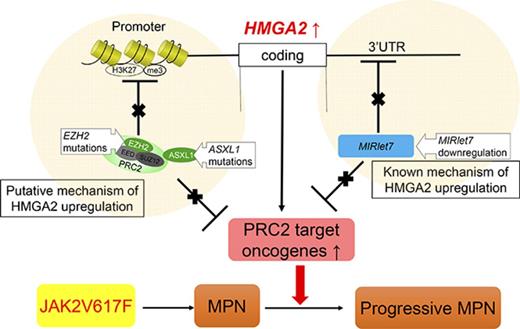

In patients with MPNs, repression of MIRlet-7 and mutations in the polycomb genes EZH2 and ASXL1 correlate with HMGA2 overexpression.

Hmga2 overexpression collaborates with JAK2V617F to promote lethal MPN in mice, highlighting the crucial role of Hmga2.

Abstract

High-mobility group AT-hook 2 (HMGA2) is crucial for the self-renewal of fetal hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) but is downregulated in adult HSCs via repression by MIRlet-7 and the polycomb-recessive complex 2 (PRC2) including EZH2. The HMGA2 messenger RNA (mRNA) level is often elevated in patients with myelofibrosis that exhibits an advanced myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) subtype, and deletion of Ezh2 promotes the progression of severe myelofibrosis in JAK2V617F mice with upregulation of several oncogenes such as Hmga2. However, the direct role of HMGA2 in the pathogenesis of MPNs remains unknown. To clarify the impact of HMGA2 on MPNs carrying the driver mutation, we generated ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice overexpressing Hmga2 due to deletion of the 3′ untranslated region. Compared with JAK2V617F mice, ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice exhibited more severe leukocytosis, anemia and splenomegaly, and shortened survival, whereas severity of myelofibrosis was comparable. ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F cells showed a greater repopulating ability that reproduced the severe MPN compared with JAK2V617F cells in serial bone marrow transplants, indicating that Hmga2 promotes MPN progression at the HSC level. Hmga2 also enhanced apoptosis of JAK2V617F erythroblasts that may worsen anemia. Relative to JAK2V617F hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), over 30% of genes upregulated in ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F HSPCs overlapped with those derepressed by Ezh2 loss in JAK2V617F/Ezh2Δ/Δ HSPCs, suggesting that Hmga2 may facilitate upregulation of Ezh2 targets. Correspondingly, deletion of Hmga2 ameliorated anemia and splenomegaly in JAK2V617F/Ezh2Δ/wild-type mice, and MIRlet-7 suppression and PRC2 mutations correlated with the elevated HMGA2 mRNA levels in patients with MPNs, especially myelofibrosis. These findings suggest the crucial role of HMGA2 in MPN progression.

Introduction

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), including polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), and primary myelofibrosis (primary MF [PMF]), are characterized by the chronic proliferation of mature myeloid cells, extramedullary hematopoiesis, and progression to MF or acute leukemia.1-3 Mutations in JAK2,4,5 CALR,6,7 and MPL8 are established drivers of myeloproliferation. Expression of JAK2V617F in mice can reproduce PV, ET, or MF phenotype,9-14 but the role of driver mutations in clonal expansion and disease progression has not been well defined. Mutations in epigenetic modifiers, such as TET2,15 DNMT3A,16,17 ASXL1,18 and EZH2,19 and the aberrant expression of microRNAs20 might lead to MPN progression by altering gene expression, but their targets are largely unknown.

We21 and others22 recently demonstrated elevation of the proto-oncogene, high-mobility group AT-hook 2 (HMGA2) messenger RNA (mRNA) in granulocytes and CD34+ cells of patients with MPNs, especially in PMF with the worst outcome among MPNs.23 HMGA2 expression is negatively regulated by MIRlet-7 microRNAs,24 and high HMGA2 mRNA levels were correlated with reduced MIRlet-7 in some patients with MPNs.21 We have generated transgenic (tg) mice harboring Hmga2 complementary DNA (cDNA) with a truncated 3′ untranslated region (UTR) (ΔHmga2), thereby lacking binding sites of MIRlet-7 that repress Hmga2 expression.25 ΔHmga2 mice overexpress Hmga2, develop ET-like disease, and their hematopoietic cells exhibit a clonal advantage against wild-type (WT) cells at the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) level in serial bone marrow (BM) transplants (BMTs). Alternatively, endogenous Hmga2 expression is upregulated by the loss of Bmi1 or Ezh2 in conjunction with Arf/Ink4a-knockout (KO)26 or JAK2V617F27-29 in mice representing more severe MF than mice with Arf/Ink4a-KO or JAK2V617F alone.

HMGA2 is important for the self-renewal of fetal HSCs, but is not expressed in normal adult tissues and hematopoiesis,30 whereas various cancer cells overexpress HMGA2.31,32 HMGA2 mRNA is overexpressed in hematopoietic cells of most patients with PMF,21,22,33 but its direct role in the MPNs remains unknown. Here, because most MPN patients with high HMGA2 mRNA levels harbor a driver mutation represented by JAK2V617F,21 we studied mice carrying both JAK2V617F and overexpression of Hmga2 due to tg-ΔHmga2 (ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F) or conditional deletion of Ezh2 (JAK2V617F/Ezh2Δ). The present study revealed that Hmga2 directly promotes progression of MPN with JAK2V617F and, correspondingly, severe MPN of JAK2V617F/Ezh2Δ/WT mice can be rescued by deletion of Hmga2; the study also revealed that MIRlet-7 suppression and polycomb-recessive complex 2 (PRC2) mutations correlated with the elevated HMGA2 mRNA levels in patients with PMF.

Materials and methods

Mice

All mice were on a C57BL6/J background and analyzed 12 weeks after birth or 8 weeks after BMT unless otherwise specified. ΔHmga2 mice25 and JAK2V617F mice (line 2 with MF generated from BDF-1 by backcrossing with WT C57BL6/J mice)13,34 were previously described. Ezh2flox/flox mice35 were crossed with Rosa26::Cre-ERT mice (TaconicArtemis GmbH, Köln, Germany), and deletion of Ezh2 was induced by intraperitoneal administration of 1 mg per day tamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in corn oil (Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 consecutive days from 4 weeks after BMT. HMGA2−/WT mice,36 and Ly5.2+ and Ly5.1+ WT mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), CLEA (Tokyo, Japan), and RIKEN-BRC (Tsukuba, Japan). Peripheral blood cells were counted by XT-1800i (Sysmex, Kobe, Japan). All studies were approved by the Animal Study Committee of Fukushima Medical University.

Histopathology

Hematoxylin-eosin, silver, and anti-HMGA2 stains (Spring Bioscience, Pleasanton, CA) were performed for paraffin-embedded samples with standard protocols. Pictures were taken and digitized by a DP73 microscope with CellSens software (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Cells

From mice, peripheral leukocytes were obtained by lysing samples with Pharm Lyse (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ). BM nuclear cells were collected by grinding bones, and mononuclear cells (MNCs) were separated by centrifugation through Ficoll Histopaque (Sigma-Aldrich). The patients’ granulocytes were separated by centrifugation through Ficoll Lymphosepar I (IBL, Gunma, Japan).21

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed using a FACSCanto II (BD). Cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-Ter119, phycoerythrin (PE)-CD71, eFluora 450–B220, peridinin chlorophyll (PerCP)/Cy5.5–T-cell receptor β (TCRβ), and allophycocyanin (APC)-Gr1; or PerCP/Cy5.5-Sca-I, PE/Cy7-cKit, Alexa647-CD34, PE-CD16/32, FITC-CD41, and Biotin-Lineage (CD3e, CD4, CD5, CD8a, CD11, B220, Ter119, and Gr1) followed by visualization with APC/Cy7-streptavidin. For chimerism analyses, eFluora450-B220, PerCP/Cy5.5-TCRβ, APC-CD45.1, and PE-CD45.2 (all from eBioscience, San Diego, CA) were used. Phosflow with phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3) antibody (BD) was performed according to the manufacturers’ protocol.

Colony assay

On a 35-mm plate, BM MNCs were cultured in 1 mL of semisolid methylcellulose medium. For colony-forming unit–erythroid (CFU-E), 1 × 105 cells were cultured in M3234 (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) with or without human erythropoietin (EPO; Bioworld Technology, St. Louis Park, MN), and the colony numbers were counted after 3 days. For myeloid colonies, 1 × 104 cells were cultured in M3434 (StemCell Technologies) and colonies were counted after 5 days.

Western blotting

The total protein was extracted from 1 × 107 BM MNCs using CelLytic M buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). The samples were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden), blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (Wako, Tokyo, Japan), and probed with primary antibodies to Stat3, pStat3 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), actin, and anti-rabbit or anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX). The signals were detected with the LAS3000 (Fujitsu, Tokyo, Japan), and densities of bands were measured using ImageJ (version 1.50i; NIH, Bethesda, MD).

BMT

Recipient mice were lethally irradiated (9.0 Gy) 24 hours before BMT and cells were injected IV under anesthesia with isoflurane (Intervet, Osaka, Japan). In the competitive repopulations, 2.5 × 106 Ly5.2+ BM cells with the same number of Ly5.1+ WT BM cells were injected into Ly5.1+ mice. Serial BMTs were performed from these recipients to other lethally irradiated Ly5.1+ mice. For phenotypic reconstitution, 5.0 × 106 BM cells were injected.

RNA sequencing

Each preparation of RNA extracted from flow-sorted BM lineage−Sca1+cKit+ cells (LSKs) and CD71+Ter119+ erythroblasts using an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was subjected to reverse transcription (RT) and amplification for 14 cycles, respectively, with the SMARTer Ultra Low Input RNA kit for Sequencing v3 (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). The double strand–cDNA was fragmented using the S220 Focused ultrasonicator (Covaris), then cDNA libraries were generated using a NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep kit (New England BioLabs, Beverly, MA). Sequencing was performed using HiSeq1500 (Illumina) with a single-read sequencing length of 60 bp. After mapping the reference genes to mm10 with TopHat v2.0.13, fragments per kilobase of exon per million reads mapped (FPKM) and reads per kilobase of exon per million reads mapped (RPKM) values were calculated using Cufflinks v2.2.1. After omitting the genes with <0.3 FPKM/RPKM values, values were used for evaluation of gene expressions and detections of affected gene sets by gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA; Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA). Genes with >1.5-fold upregulation were also applied to the pathway analysis using Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (IPA; Qiagen). Principal component analysis and statistical significance for overlapping genes among genotypes were evaluated according to the RPKM values with 0.5 of the pseudo count using R 3.3.0 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria). Gene sets with both <.05 nominal P values and <0.25 false discovery rate (FDR) q values were determined as significantly affected sets in GSEA. Pathways with a z score > |2| were considered to be significant for IPA.

Patients

We studied 45 patients (27 ET, 18 PMF), including 15 patients who were enrolled in our previous study.21 The diagnosis was made according to World Health Organization (WHO) 2008 criteria,37 and peripheral blood samples were collected at the time of examination. Samples from 13 healthy volunteers served as controls. The present study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of Fukushima Medical University, which is guided by local policy, national law, and the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient and healthy volunteer.

qRT-PCR

The total RNA extracted from granulocytes was used for RT with RevarTra Ace qPCR RT Master Mix (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan) and the TaqMan MicroRNA RT kit (LifeTechnologies, Carlsbad, CA) for mRNA and microRNA, respectively. Quantitative RT–polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed using a TP800 (Takara, Otsu, Japan) followed by data analysis with Multiplate RQ software (Takara) using the comparative cycle threshold method. RNA levels were determined as relative to HPRT1 and U6 noncoding RNA for mRNA and microRNA, respectively. The upper limit of the HMGA2 mRNA level in granulocytes (1.0) was determined in our former study according to +2 standard deviations (SDs) of the mean value in 13 healthy volunteers.21 The lower limit level of MIRlet-7c in granulocytes was determined according to −2SD of the mean value of 15 healthy volunteers. The primers and probes are listed in supplemental Table 1.

Mutation analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from the patients’ peripheral leukocytes using the QIAamp DNA Mini kit (Qiagen) for screening of mutations in JAK2, MPL,and CALR38-40 and the target sequence for 50 genes41 in a GeneRead DNAseq panel for human myeloid neoplasms (Qiagen) using a MiSeq (Illumina). The data were analyzed by the Qiagen NGS Data Analysis web portal. Silent mutations and known germ line polymorphisms in the National Center for Biotechnology Information single nucleotide polymorphism public database were excluded.

Statistics

Statistical significance was determined by an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test, the Tukey–honest significant difference (HSD) test, or 2-way factorial analysis of variance. Survival differences were measured by a log-rank test. All statistical analyses were performed using R3.3.0.

Results

Hmga2 promotes progression of MPN in JAK2V617F mice

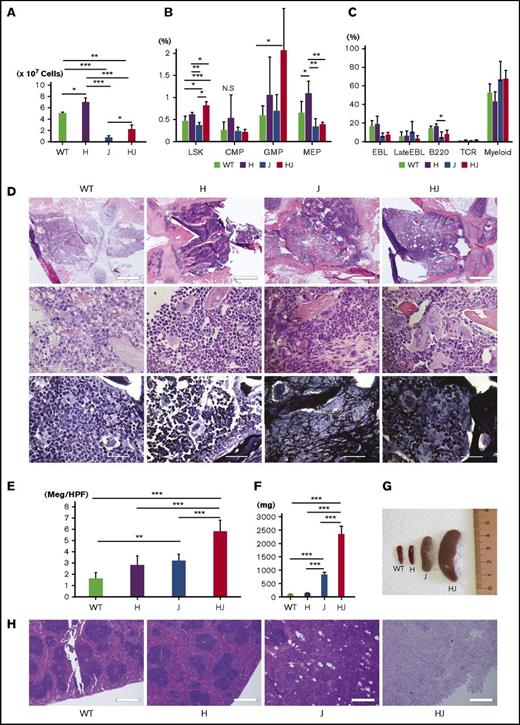

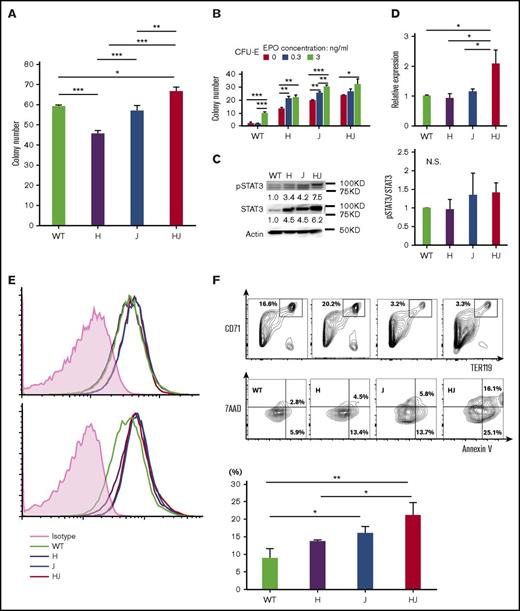

First, we crossed ΔHmga2 mice with JAK2V617F-tg (JAK2V617F) mice (Figure 1A). WT, ∆Hmga2/JAK2WT (ΔHmga2), Hmga2WTJAK2V617F (JAK2V617F), and ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice were born at expected Mendelian ratios. At 12 weeks old, JAK2V617F mice showed leukocytosis and anemia; we previously reported the similar trend in mice with JAK2V617F of BDF-113 and C57BL6/J27,34 backgrounds. However, leukocytosis and anemia were most severe in ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice (Figure 1B). Neutrophilia without proliferation of blasts was prominent in ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice (Figure 1C-D). The ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice died within 150 days, whereas other mice survived for over 1 year (Figure 1E). The number of BM nuclear cells were increased in ΔHmga2 mice but decreased in JAK2V617F mice, and they were partially restored in ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice (Figure 2A). In the presence of JAK2V617F, Hmga2 augmented the ratio of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell (HSPC)-enriched LSKs (Figure 2B), but not erythroblasts (Figure 2C). Modest increases of granulocyte-macrophage progenitor and Gr1+ cells were observed in the JAK2V617F and ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice (Figure 2B-C). Megakaryocytes were more proliferative in ΔHmga2 and Jak2V617F mice compared with WT mice, and were further increased in ΔHmga2/Jak2V617F mice without morphologic change (Figure 2D-E). JAK2V617F and ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F BM were equally fibrotic; there was no MF in the WT or ΔHmga2 BM (Figure 2D). Splenomegaly was more remarkable and the splenic structures were destroyed in ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice compared with both ΔHmga2 and JAK2V617F mice (Figure 2F-H). BM cells showed slight increases in myeloid colonies in ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice (Figure 3A). All of the ΔHmga2, JAK2V617F, and ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F BM showed EPO-independent erythroid-colony formation, an important feature of MPN. The colony numbers were the highest in ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F for each EPO concentration, and the difference became smaller as the EPO concentration increased (Figure 3B).

Progressive MPN in ΔHmga2/JAK2V617Fmice. (A) Schematic diagram of the experiment. WT, ΔHmga2 (H), JAK2V617F (J), and ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F (HJ) mice were obtained in predicted Mendelian ratios. The analyses were performed at 12 weeks old. (B) Complete blood cell counts (means ± standard error of the mean [SEM]) and (C) fractions of white blood cells (%) in 5 WT, 7 H, 5 J, and 4 HJ mice. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 calculated by the Tukey-HSD test. (D) May-Giemsa stains of peripheral blood samples (original magnification ×1000). Scale bars indicate 50 µm. (E) Survival periods. N = 9 for WT, 9 H, 12 J, and 7 HJ mice. The P values were calculated by a log-rank test. Bas, basophil; Eos, eosinophil; Hb, hemoglobin concentration (g/dL); Lym, lymphocyte; Mon, monocyte; Neu, neutrophil; OS, overall survival; PLT, platelet count (×1011/L); RBC, red blood cell count (×1012/L); WBC, white blood cell count (×109/L).

Progressive MPN in ΔHmga2/JAK2V617Fmice. (A) Schematic diagram of the experiment. WT, ΔHmga2 (H), JAK2V617F (J), and ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F (HJ) mice were obtained in predicted Mendelian ratios. The analyses were performed at 12 weeks old. (B) Complete blood cell counts (means ± standard error of the mean [SEM]) and (C) fractions of white blood cells (%) in 5 WT, 7 H, 5 J, and 4 HJ mice. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 calculated by the Tukey-HSD test. (D) May-Giemsa stains of peripheral blood samples (original magnification ×1000). Scale bars indicate 50 µm. (E) Survival periods. N = 9 for WT, 9 H, 12 J, and 7 HJ mice. The P values were calculated by a log-rank test. Bas, basophil; Eos, eosinophil; Hb, hemoglobin concentration (g/dL); Lym, lymphocyte; Mon, monocyte; Neu, neutrophil; OS, overall survival; PLT, platelet count (×1011/L); RBC, red blood cell count (×1012/L); WBC, white blood cell count (×109/L).

Hmga2 expression augments BM cells and HSCs with enhancing extramedullary hematopoiesis in JAK2V617F-induced MPN. (A) The total nuclear cell numbers from the ground right femur (×107). N = 3 for each. (B) The ratio of each fraction in BM by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS; percentage in all gated cells) is shown. N = 5 for WT, 5 H, 4 J, and 3 HJ mice. (C) Ratios of differentiated cells in BM (percentage in all gated cells). N = 3 for each genotype. (D) Sternal BM histology. Hematoxylin and eosin (top and middle) and silver (bottom) stains. Scale bars indicate 500 μm (top; original magnification ×40) and 50 µm (middle and bottom; original magnification ×1000). (E) Mean megakaryocyte counts in high-powered field (Meg/HPF; ×400). Mean of 5 fields are shown in each genotype. (F) Spleen weight (N = 4, each genotype). (G) Representative picture of the spleens from the littermates. (H) Histology of spleens (hematoxylin and eosin stain). Scale bars indicate 500 µm (original magnification ×40). (A-C, E-F) Bars show the means ± SEM. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 (Tukey-HSD test). B220, B220+ B cell; CMP, common myeloid progenitor cell; EBL, CD71+Ter119+ erythroblast; GMP, granulocyte-macrophage progenitor cell; H, ΔHmga2; HJ, ∆Hmga2/JAK2V617F; J, JAK2V617F; LateEBL/Ret, CD71+Ter119dim late erythroblast/reticulocyte; MEP, megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitor cell; Myeloid, Gr-1+ myeloid cell; N.S., not significant; T, TCR+ T cell.

Hmga2 expression augments BM cells and HSCs with enhancing extramedullary hematopoiesis in JAK2V617F-induced MPN. (A) The total nuclear cell numbers from the ground right femur (×107). N = 3 for each. (B) The ratio of each fraction in BM by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS; percentage in all gated cells) is shown. N = 5 for WT, 5 H, 4 J, and 3 HJ mice. (C) Ratios of differentiated cells in BM (percentage in all gated cells). N = 3 for each genotype. (D) Sternal BM histology. Hematoxylin and eosin (top and middle) and silver (bottom) stains. Scale bars indicate 500 μm (top; original magnification ×40) and 50 µm (middle and bottom; original magnification ×1000). (E) Mean megakaryocyte counts in high-powered field (Meg/HPF; ×400). Mean of 5 fields are shown in each genotype. (F) Spleen weight (N = 4, each genotype). (G) Representative picture of the spleens from the littermates. (H) Histology of spleens (hematoxylin and eosin stain). Scale bars indicate 500 µm (original magnification ×40). (A-C, E-F) Bars show the means ± SEM. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 (Tukey-HSD test). B220, B220+ B cell; CMP, common myeloid progenitor cell; EBL, CD71+Ter119+ erythroblast; GMP, granulocyte-macrophage progenitor cell; H, ΔHmga2; HJ, ∆Hmga2/JAK2V617F; J, JAK2V617F; LateEBL/Ret, CD71+Ter119dim late erythroblast/reticulocyte; MEP, megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitor cell; Myeloid, Gr-1+ myeloid cell; N.S., not significant; T, TCR+ T cell.

Stat3 activation and apoptotic erythroblasts in ΔHmga2/JAK2V617Fmice. (A) Myeloid colonies from 1 × 104 BM MNCs (N = 3 for each genotype, means ± SEM). *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 (Tukey-HSD tests). (B) Numbers of CFU-E colonies (means ± SEM) from 1 × 105 of BM MNCs (N = 3 for each genotype). *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 (Tukey-HSD tests). The P values calculated by ANOVA were <.01 for both EPO concentrations and mouse transgenes. (C) Western blotting of Stat3 and pStat3 in BM MNCs without cytokine stimulation in each tg mouse. Left panel, A representative result; right panel, mean pSTAT3/STAT3 concentration (from 2 independent experiments) relative to WT. (D) Stat3 mRNA in BM MNCs by qRT-PCR (means ± SEM; N = 3 for each). *P < .05 (Tukey-HSD test). (E) FACS for pStat3 in BM MNCs incubated in the absence (top) and presence (bottom) of IL-3. The horizontal and vertical axes, respectively, indicate the brightness of pStat3 and the cell counts. (F) FACS for apoptosis of CD71+Ter119+ erythroblasts by Annexin V/7-Aminoactinomycin D (7AAD) staining. Top panel, A representative result; bottom panel, mean ratio of Annexin V+/7AAD− apoptotic erythroblasts from 3 independent experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 (Tukey-HSD tests). (A-F) H, ΔHmga2; J, JAK2V617F; HJ, ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F.

Stat3 activation and apoptotic erythroblasts in ΔHmga2/JAK2V617Fmice. (A) Myeloid colonies from 1 × 104 BM MNCs (N = 3 for each genotype, means ± SEM). *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 (Tukey-HSD tests). (B) Numbers of CFU-E colonies (means ± SEM) from 1 × 105 of BM MNCs (N = 3 for each genotype). *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 (Tukey-HSD tests). The P values calculated by ANOVA were <.01 for both EPO concentrations and mouse transgenes. (C) Western blotting of Stat3 and pStat3 in BM MNCs without cytokine stimulation in each tg mouse. Left panel, A representative result; right panel, mean pSTAT3/STAT3 concentration (from 2 independent experiments) relative to WT. (D) Stat3 mRNA in BM MNCs by qRT-PCR (means ± SEM; N = 3 for each). *P < .05 (Tukey-HSD test). (E) FACS for pStat3 in BM MNCs incubated in the absence (top) and presence (bottom) of IL-3. The horizontal and vertical axes, respectively, indicate the brightness of pStat3 and the cell counts. (F) FACS for apoptosis of CD71+Ter119+ erythroblasts by Annexin V/7-Aminoactinomycin D (7AAD) staining. Top panel, A representative result; bottom panel, mean ratio of Annexin V+/7AAD− apoptotic erythroblasts from 3 independent experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 (Tukey-HSD tests). (A-F) H, ΔHmga2; J, JAK2V617F; HJ, ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F.

We sought the basis of the severe phenotype in ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice. Based on a recent finding on the importance of STAT3 in MPNs,42 we investigated the Stat3 status. We found increased expression of Stat3 mRNA and protein in BM MNCs of ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice compared with ΔHmga2 and JAK2V617F mice (Figure 3C-D), whereas the basal Stat3 phosphorylation was comparable among these genotypes (Figure 3C,E). We also evaluated the apoptosis of erythroblasts because ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice presented with more severe anemia despite EPO-independent erythroid-colony formation and similar MF compared with JAK2V617F mice. The ratios of erythroblasts were equally altered in JAK2V617F and ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F BM, but ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F erythroblasts were more apoptotic (Figure 3F).

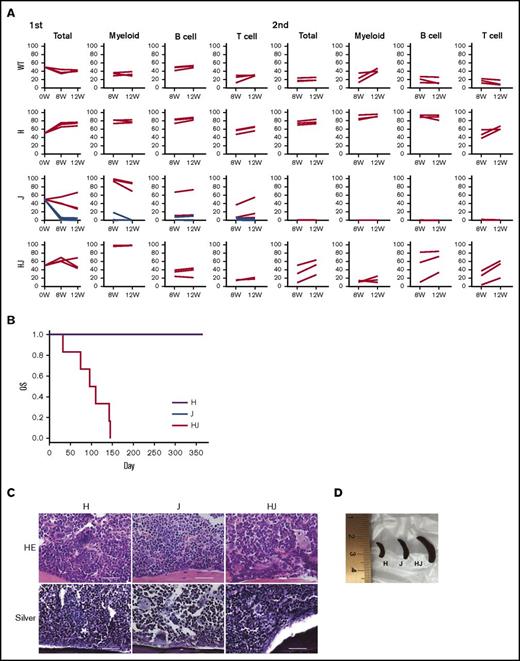

Hmga2 expands the JAK2V617F clone and reproduces the severe MPN after BMT

To investigate repopulating ability, we transplanted Ly5.2+ ΔHmga2, JAK2V617F, or ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F BM cells with Ly5.1+ competitor cells into lethally irradiated mice. After the initial BMT, ΔHmga2, and ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F cells were engrafted in all recipients, whereas JAK2V617F cells were <10% in 4 of 7 recipients (Figure 4A). The proportion of the Ly5.2+ donor cells were the highest in recipients of ΔHmga2 followed by ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F in B cells and total cells, and the opposite was found in myeloid cells. After a second BMT, ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F cells were less dominant than ΔHmga2 cells but were restored, whereas JAK2V617F cells were completely rejected (Figure 4A). ΔHmga2 cells fully expanded after a third BMT (not shown), confirming the strong repopulating and self-renewal abilities of HSCs overexpressing Hmga2,25,30 which likely conferred a clonal dominance to JAK2V617F cells. Moreover, the BMT from ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice to WT mice reproduced splenomegaly and proliferation of megakaryocytes in BM, despite not inducing MF (Figure 4C-D). However, mice transplanted with ΔΔHmga2/JAK2V617F cells survived for a shorter time compared with the recipients from single-tg mice (Figure 4B).

Hmga2 expression promotes the repopulating ability and phenotypic reconstitution of JAK2V617F-induced MPN. (A) Competitive repopulations (N = 3-7). Ly5.2+ H, J, or HJ BM cells with competitor Ly5.1+ WT BM cells at the ratio of 1:1 were injected into lethally irradiated Ly5.1+ mice. The ratios (percentage; vertical axis) of Ly5.2+ cells in lineages at the indicated time points (horizontal axis) after the first (left) and second (right) BMT are shown. BM cells collected 12 weeks after first BMT were injected for recipients of the secondary BMT. Among J (JAK2V617F) mice (N = 7), BM cells from mice that achieved engraftment at the first BMT (red lines, N = 3) were exclusively referred to the second BMT. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves, (C) sternal BM histology, and (D) representative picture of the spleens of recipient mice at 12 weeks after the BMT, in BMT from the indicated transgenic mice without competitors (N = 6 for each). (B) P values were calculated by a log-rank test. (C) Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) and silver stains are shown (original magnification ×400). Scale bars indicate 50 µm. H, ΔHmga2; J, JAK2V617F; HJ, ∆Hmga2/JAK2V617F.

Hmga2 expression promotes the repopulating ability and phenotypic reconstitution of JAK2V617F-induced MPN. (A) Competitive repopulations (N = 3-7). Ly5.2+ H, J, or HJ BM cells with competitor Ly5.1+ WT BM cells at the ratio of 1:1 were injected into lethally irradiated Ly5.1+ mice. The ratios (percentage; vertical axis) of Ly5.2+ cells in lineages at the indicated time points (horizontal axis) after the first (left) and second (right) BMT are shown. BM cells collected 12 weeks after first BMT were injected for recipients of the secondary BMT. Among J (JAK2V617F) mice (N = 7), BM cells from mice that achieved engraftment at the first BMT (red lines, N = 3) were exclusively referred to the second BMT. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves, (C) sternal BM histology, and (D) representative picture of the spleens of recipient mice at 12 weeks after the BMT, in BMT from the indicated transgenic mice without competitors (N = 6 for each). (B) P values were calculated by a log-rank test. (C) Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) and silver stains are shown (original magnification ×400). Scale bars indicate 50 µm. H, ΔHmga2; J, JAK2V617F; HJ, ∆Hmga2/JAK2V617F.

Long-term Hmga2 expression causes anemia without MF

The impact of Hmga2 on MF was not evident in BMT. To clarify whether Hmga2 alone induces fibrosis in the long-term, we studied old ΔHmga2 mice (supplemental Figure 1). Eventually, 60-week-old ΔHmga2 mice exhibited anemia, but ratios of their erythroid progenitors and erythroblasts were not different from old WT mice. They showed moderate splenomegaly, but never developed MF, as confirmed in a considerable number (N = 26). Moreover, the erythroblasts from old ΔHmga2 mice were more apoptotic compared with old WT mice. However, serial BMT revealed that cells from old ΔHmga2 mice retain a clonal advantage against young WT cells. Taken together, the long-term expression of Hmga2 induces anemia possibly due to the apoptosis of erythroblasts without MF, whereas their HSCs possess the repopulating ability of young ΔHmga2 mice.

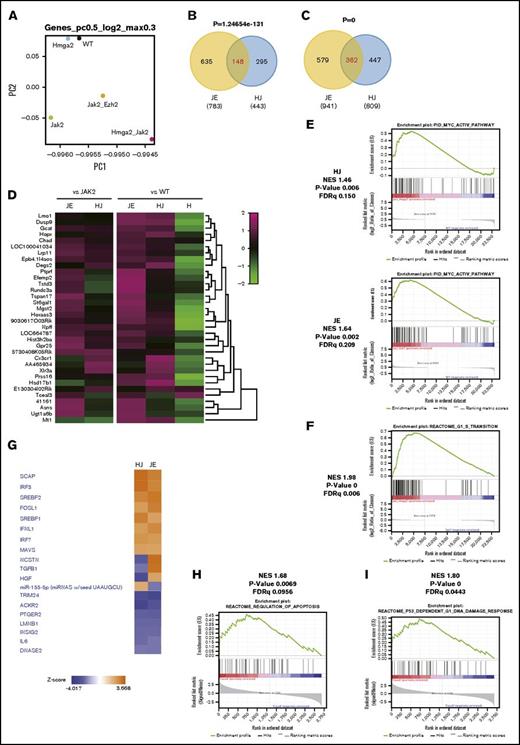

Gene expression profile in JAK2V617F cells with Hmga2 overexpression

HMGA2 changes chromatin structure and binds to AT-rich DNA sequences via AT-hook domains, leading to the upregulations of targets.43 To identify HMGA2 targets in the setting of MPNs, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) of LSKs from WT, ΔHmga2, JAK2V617F, and ∆Hmga2/JAK2V617F mice, as well as JAK2V617F/Ezh2Δ/Δ mice based on recent reports showing that Ezh2 KO deteriorates MPNs with upregulating endogenous Hmga2 expression in HSPCs of mice with JAK2V617F.27-29 Relative to WT, ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice showed the greatest change in the gene expression profile among genotypes (Figure 5A). We found that 148 of 443 genes (33.4%) or 362 of 809 genes (44.7%) were upregulated in ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice compared with JAK2V617F mice or WT mice, respectively, overlapped with those of JAK2V617F/Ezh2Δ/Δ mice (Figure 5B-C; supplemental Table 2), and that 35 genes, including known oncogenes targeted by Ezh2, Lmo1, Gcat, and Prss16,44 were common (Figure 5D). There were some commonly enriched gene sets, including those involved in activation of the MYC pathway between ∆Hmga2/JAK2V617F and JAK2V617F/Ezh2Δ/Δ mice (Figure 5E). ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F LSKs had frequent upregulation of gene sets associated with cell cycle and metabolism (Figure 5F; supplemental Tables 3 and 4). Pathway analysis with IPA also revealed the common activation of several pathways in LSKs of ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F and JAK2V617F/Ezh2Δ/Δ mice compared with those of JAK2V617F mice, including chaperone-related SCAP and SREBF1/2 pathways, whereas TGFB was upregulated only in those of JAK2V617F/Ezh2Δ/Δ mice (Figure 5G).

Hmga2 overexpression alters transcription of genes including the targets of Ezh2. (A) A Principal component (PC) analysis based on total gene expression in LSK cells (LSKs) isolated from WT, H, J, HJ, or JE recipient mice (5 for each and mixed for RNA-seq) 4 weeks after tamoxifen injection. (B) Venn diagrams showing upregulated genes between HJ and JE LSKs relative to J. (C) Venn diagrams showing upregulated genes between HJ and JE LSK cells relative to WT. (D) Heatmaps showing the expression of representative genes upregulated in panels B and C. (E) MYC pathway enriched in HJ (top) and JE (bottom) compared with WT. This pathway was not enriched in J (FDR = 0.389). (F) Enrichment plot of G1-S transition (HJ vs J), which represents frequent upregulations of gene sets associated with cell cycle and metabolism in ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F LSKs (shown in supplemental Tables 3 and 4). (G) Signal activation/inactivation in HJ and JE mice relative to J shown by an upstream analysis. Pathways with z score > |2| in both HJ and JE are shown. (H) CD71+Ter119+ erythroblasts sorted from BM of 12-week-old WT, H, J, and HJ mice (3 for each) were mixed for RNA-seq. Enrichment of gene sets for regulation of apoptosis (HJ vs J) is shown. (I) GSEA of RNA-seq data for p53-dependent G1 DNA damage response pathway in erythroblasts (HJ vs J). H, ΔHmga2; J, JAK2V617F; HJ, ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F; JE, JAK2V617F/Ezh2Δ/Δ; NES, normalized enrichment score.

Hmga2 overexpression alters transcription of genes including the targets of Ezh2. (A) A Principal component (PC) analysis based on total gene expression in LSK cells (LSKs) isolated from WT, H, J, HJ, or JE recipient mice (5 for each and mixed for RNA-seq) 4 weeks after tamoxifen injection. (B) Venn diagrams showing upregulated genes between HJ and JE LSKs relative to J. (C) Venn diagrams showing upregulated genes between HJ and JE LSK cells relative to WT. (D) Heatmaps showing the expression of representative genes upregulated in panels B and C. (E) MYC pathway enriched in HJ (top) and JE (bottom) compared with WT. This pathway was not enriched in J (FDR = 0.389). (F) Enrichment plot of G1-S transition (HJ vs J), which represents frequent upregulations of gene sets associated with cell cycle and metabolism in ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F LSKs (shown in supplemental Tables 3 and 4). (G) Signal activation/inactivation in HJ and JE mice relative to J shown by an upstream analysis. Pathways with z score > |2| in both HJ and JE are shown. (H) CD71+Ter119+ erythroblasts sorted from BM of 12-week-old WT, H, J, and HJ mice (3 for each) were mixed for RNA-seq. Enrichment of gene sets for regulation of apoptosis (HJ vs J) is shown. (I) GSEA of RNA-seq data for p53-dependent G1 DNA damage response pathway in erythroblasts (HJ vs J). H, ΔHmga2; J, JAK2V617F; HJ, ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F; JE, JAK2V617F/Ezh2Δ/Δ; NES, normalized enrichment score.

We also investigated CD71+Ter119+ erythroblasts by RNA-seq to identify the mechanisms of severe anemia in ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice. Significantly affected groups (supplemental Tables 5 and 6) included gene sets of apoptosis regulation (Figure 5H) and p53 activation (Figure 5I), which is well known to induce anemia due to apoptosis of erythroid progenitors.45-47 Moreover, enriched gene sets in erythroblasts were different from those in LSKs. For example, interferon-related genes, involving the JAK-STAT pathway, were enriched in erythroblasts (FDR q = 0.02; supplemental Table 5), but not in LSKs (FDR q > 0.5), of ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice.

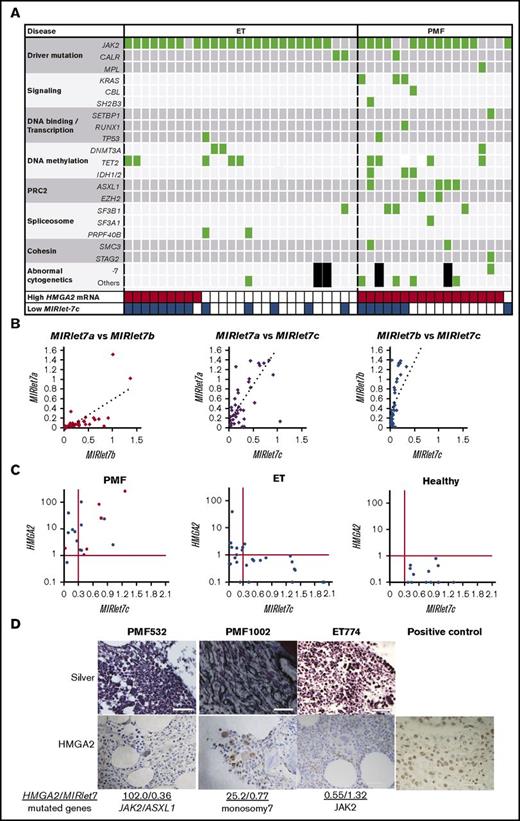

Most patients with PMF highly express HMGA2 mRNA with the repression of MIRlet-7 or mutations in PRC2 components

Subsequently, we studied the HMGA2 mRNA and MIRlet-7 levels, and mutations in the epigenetic modifiers in patients with MPNs. We focused on ET and PMF because the megakaryocyte lineage is dominant in those groups and an Ezh2 deletion in megakaryocytes played an important role in the progression of JAK2V617F-induced MF.27 High HMGA2 mRNA levels were observed in granulocytes of some ET (9 of 27, 33.3%) and most PMF (17 of 18, 94.4%). Most patients had a driver mutation in JAK2, CALR, or MPL in both ET (25 of 27, 92.6%) and PMF (15 of 18, 83.3%). For other investigated genes, most patients with PMF harbored at least 1 additional mutation, whereas ET rarely had such a mutation, except for DNA methylation–related enzymes (Figure 6A; supplemental Table 7). Patients with PMF also carried chromosomal abnormalities; none of them showed 12q rearrangement involving the HMGA2 locus, whereas 1 patient had monosomy 7, which causes EZH2 loss.19

High HMGA2 mRNA levels in patients with PMF are correlated with either repressed MIRlet-7 expressions or mutations in PRC2 components. (A) Mutations in the patients with ET (N = 27) and PMF (N = 18). Black squares indicate no metaphase cells in the chromosomal analysis. (B) Correlations in the expression of MIRlet-7a, -7b, and -7c in granulocytes of the patients with ET and PMF. MIRlet-7a vs -7b, R = 0.70 (left); MIRlet-7a vs -7c, R = 0.74 (center); MIRlet-7b vs -7c, R = 0.85 (right) (R indicates correlation coefficients). (C) Correlations in the expression levels of MIRlet-7c and HMGA2 mRNA in the granulocytes of individual patients. The red lines indicate the lower (MIRlet-7c) or upper (HMGA2) limit of the normal range determined according to the data of the healthy controls (see “Materials and methods”). Red circles indicate the patients with mutations in PRC2-related EZH2 and ASXL1, and a rhomboid denotes a patient with monosomy 7 involving EZH2. (D) Immunostaining of biopsied BM. The nuclei of megakaryocytes from 2 PMF patients with high expression of HMGA2 were positively stained by anti-HMGA2 antibody; those of the ET patient with low expression of HMGA2 were not stained. The tissue from breast cancer, in which the nuclei of neoplastic cells were positively stained, was used as a positive control. Scale bars indicate 50 μm.

High HMGA2 mRNA levels in patients with PMF are correlated with either repressed MIRlet-7 expressions or mutations in PRC2 components. (A) Mutations in the patients with ET (N = 27) and PMF (N = 18). Black squares indicate no metaphase cells in the chromosomal analysis. (B) Correlations in the expression of MIRlet-7a, -7b, and -7c in granulocytes of the patients with ET and PMF. MIRlet-7a vs -7b, R = 0.70 (left); MIRlet-7a vs -7c, R = 0.74 (center); MIRlet-7b vs -7c, R = 0.85 (right) (R indicates correlation coefficients). (C) Correlations in the expression levels of MIRlet-7c and HMGA2 mRNA in the granulocytes of individual patients. The red lines indicate the lower (MIRlet-7c) or upper (HMGA2) limit of the normal range determined according to the data of the healthy controls (see “Materials and methods”). Red circles indicate the patients with mutations in PRC2-related EZH2 and ASXL1, and a rhomboid denotes a patient with monosomy 7 involving EZH2. (D) Immunostaining of biopsied BM. The nuclei of megakaryocytes from 2 PMF patients with high expression of HMGA2 were positively stained by anti-HMGA2 antibody; those of the ET patient with low expression of HMGA2 were not stained. The tissue from breast cancer, in which the nuclei of neoplastic cells were positively stained, was used as a positive control. Scale bars indicate 50 μm.

The expression levels of MIRlet-7a, -7b, and -7c were correlated with each other (Figure 6B), and the expression of MIRlet-7c represents those of MIRlet-7 family members. Interestingly, the reduced MIRlet-7c levels were correlated with high HMGA2 mRNA levels in most patients with ET, but in less than half of the PMF. Patients with MPNs who highly expressed HMGA2 mRNA (6 of 26, 23.1%) more often harbored monosomy 7 or mutations in PRC2 members, EZH2 and ASXL1, compared with patients without high HMGA2 expression (0 per 19, 0%; P = .032), especially in patients without a reduction in MIRlet-7 expression (5 of 11, 45.5%) (Figure 6A,C). In contrast, there were no differences in the frequencies of mutations in other gene groups. Therefore, the loss of PRC2 members might be associated with the upregulation of HMGA2 in patients as in mice.27-29 We then investigated the expression of HMGA2 in biopsied BM. HMGA2 is highly expressed primarily in hematopoietic cells, especially the nucleus of megakaryocytes (Figure 6D), suggesting the possibility that HMGA2 correlates with proliferation of megakaryocytes in these patients as in JAK2V617F mice overexpressing HMGA2.

Depletion of endogenous Hmga2 ameliorates MPN with anemia in JAK2V617F mice with the loss of Ezh2

To confirm the importance of Hmga2 in MPNs with JAK2V617F and the loss of Ezh2, we crossed Hmga2-KO (Hmga2−/WT) mice36 with JAK2V617F/Ezh2Δ/Δ mice, and obtained JAK2V617F/Ezh2Δ/WT/Hmga2−/WT and JAK2V617F/Ezh2Δ/WT/Hmga2WT/WT mice after the second generation. Mice transplanted with JAK2V617F/Ezh2Δ/Δ cells and those with JAK2V617F/Ezh2Δ/WT cells showed a similar MPN-like phenotype with more severe anemia, leukocytosis, and splenomegaly compared with mice transplanted with JAK2V617F cells,27 and mimic patients with EZH2 mutations because mutations in EZH2 rarely acquire homozygosity in patients.28 Thus, we performed BMT from JAK2V617F/Ezh2Δ/WT/Hmga2−/WT and JAK2V617F/Ezh2Δ/WT/Hmga2WT/WT mice (Figure 7A). Strikingly, JAK2V617F/Ezh2Δ/WT/Hmga2−/WT recipients, whose Hmga2 mRNA was suppressed to the basal level (0.9-fold) of JAK2V617F mice, revealed significantly reduced splenomegaly, leukocytosis, thrombocythemia, and anemia, compared with JAK2V617F/Ezh2Δ/+/Hmga2WT/WT recipients with a twofold higher expression of Hmga2 mRNA compared with JAK2V617F mice (Figure 7B-C).

Hmga2 inhibition ameliorates MPN in JAK2V617Fmice with Ezh2 KO. (A) Schematic diagram of Hmga2 KO (Hmga2−/+) in JAK2V617F/EZH2fl°x/WT/CRE-ERT (JE). BM cells were collected from JE with HMGA2−/+ (JEH) or HMGA2+/+ (JE) mice and transplanted. Conditional Ezh2 KO was initiated by tamoxifen 4 weeks after transplantation. (B) Complete blood cell counts (means ± SEM). N = 5 for each. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 (Student t test). (C) Spleens at 8 weeks after transplantation with JE, JEH, JE without Cre [JE(Cre−)], and JEH without Cre [JE(Cre−)H] cells. Left, Representative figure. Right, Mean spleen weight. N = 3 for each; ***P < .001 (Turkey-HSD test).

Hmga2 inhibition ameliorates MPN in JAK2V617Fmice with Ezh2 KO. (A) Schematic diagram of Hmga2 KO (Hmga2−/+) in JAK2V617F/EZH2fl°x/WT/CRE-ERT (JE). BM cells were collected from JE with HMGA2−/+ (JEH) or HMGA2+/+ (JE) mice and transplanted. Conditional Ezh2 KO was initiated by tamoxifen 4 weeks after transplantation. (B) Complete blood cell counts (means ± SEM). N = 5 for each. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 (Student t test). (C) Spleens at 8 weeks after transplantation with JE, JEH, JE without Cre [JE(Cre−)], and JEH without Cre [JE(Cre−)H] cells. Left, Representative figure. Right, Mean spleen weight. N = 3 for each; ***P < .001 (Turkey-HSD test).

Discussion

HMGA2 is overexpressed in solid cancers, and is associated with their poor prognosis,32 but little is known about its role in hematologic diseases. In ΔHmga2 mice, Hmga2 is overexpressed by deleting its 3′UTR containing MIRlet-7–binding sites; such deletions have been found in a variety of cancers,24 but are rare in MPNs.21,33 The truncated HMGA2 make fusion genes, which may affect the disease phenotype, although MIRlet-7 is more important for regulation of gene expression than the fusions in vitro.24 In our former study, none of the 38 patients with high HMGA2 mRNA levels carried a rearrangement of the HMGA2 locus, and MIRlet-7 was low in the majority, but not in all of them.21 The present study revealed that about half of PMF patients with high HMGA2 mRNA levels, without the repression of MIRlet-7, harbor mutations of PRC2-related EZH2 and ASXL1 (Figure 6C). This might be in line with a previous report describing upregulation of Hmga2 by loss of PRC2 through H3K27 trimethylation.27 Here, our murine data may imply that Hmga2 is a key player in the progression of MPNs with loss of PRC2 or MIRlet-7. First, the addition of 3′UTR-deleted Hmga2 to JAK2V617F (ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F) mice, which represents the disruption of the MIRlet-7/HMGA2 axis in patients with MPNs, markedly exacerbated anemia, leukocytosis, and splenomegaly. These were similarly seen in JAK2V617F/Ezh2Δ/Δ mice that represent loss of PRC2.27 Correspondingly, anemia, leukocytosis, and splenomegaly were effectively ameliorated by KO of Hmga2 in JAK2V617F/Ezh2Δ/WT mice. Moreover, LSKs of ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice showed overlapping gene upregulations with JAK2V617F/Ezh2Δ/Δ mice.

Importantly, cells from ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice could reconstitute the disease phenotype following the second BMT. The influence of JAK2V617F on HSC ability is controversial; some researchers reported that JAK2V617F attenuates HSC ability,9,10,34,48 whereas others showed that JAK2V617F increases LSKs and repopulating ability.11,49 Such differences may come from variations in the strategies of introduction and the expression level of JAK2V617F.48 However, Hmga2 expression conferred a further proliferative capacity to already proliferative JAK2V617F cells and improved dominance in serial BMT, although we used the tg-JAK2V617F system in which HSC ability may be more impaired than in other systems.50 Furthermore, LSKs were decreased in JAK2V617F BM compared with WT or ΔHmga2 BM, and Hmga2 expression restored LSKs to JAK2V617F BM (Figure 2B). Thus, Hmga2 may contribute to both proliferation and expansion of an MPN clone at the HSC level, and compensate number and/or function of HSCs impaired by JAK2V617F. We also found that BMT recipients from HJ mice showed a similarly shortened survival period (97 days of median survival after the BMT; Figure 4D) as individual tg HJ mice (92 days after the birth, Figure 1E), suggesting that their cause of death was associated with hematologic abnormality. In the recipients of HJ BM, splenomegaly was more severe than in recipients of J BM, while less severe compared with individual HJ mice. On the other hand, moribund recipients of HJ BM consistently showed severe anemia (<5 g/dL hemoglobin) as seen in individual HJ mice, implying that anemia may be a possible cause of death.

In BM MNCs of ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice, Stat3 expression was higher than in other strains, and some genes involved in the JAK-STAT pathway were upregulated in erythroblasts but not LSKs of ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice, indicating that differentiated cells are more responsible to proliferative phenotype than HSPC level. Despite more severe anemia, the severity of MF was similar and BM cell number was not decreased in ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice compared with JAK2V617F mice. Considering that the apoptosis of erythroblasts was increased in ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice with enrichment of p53 activation (Figure 5H), ineffective erythropoiesis associated with p53-mediated apoptosis45-47 might be a factor that increases anemia. In contrast to ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F, JAK2V617F/Ezh2Δ/Δ mice presented more severe MF with decreased BM cellularity, compared with JAK2V617F mice.27 In the RNA-seq of LSKs, the transforming growth factor (TGF)–related pathway was upregulated in JAK2V617F/Ezh2Δ/Δ rather than ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice, relative to JAK2V617F mice. Notably, TGFBR1 is a direct target of EZH2,29 and activated TGFB signaling is important to evoke MF.51-53 Therefore, targets of Ezh2 other than Hmga2 may play a greater role in fibrosis in this context. RNA-seq also revealed that an Ezh2 deletion and overexpression of Hmga2 share deregulated oncogenic targets such as Lmo154-56 in the presence of JAK2V617F. These observations give rise to the hypothesis that when the loss of Ezh2 and/or MIRlet-7 block the inhibition of some oncogenes, Hmga2 may synergistically accelerate such upregulation in the MPN stem cells. Moreover, chaperone-related pathways were affected in both JAK2V617F/Ezh2Δ/Δ and ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice (Figure 5E). This may be consistent with the finding that HMGA2 recruits chaperones to alter chromatin structures that contribute to the oncogenic activity of HMGA2.43,57

Apart from PMF, our patients with ET did not have a mutation in EZH2 or ASXL1, in agreement with a previous report,58 and the expression levels of HMGA2 were inversely correlated with those of MIRlet-7 (Figure 6C). Thus, the cause of high expression of HMGA2 in these patients may be repression of MIRlet-7, but it is unclear how MIRlet-7 is downregulated. Lin28b is a well-known negative regulator of MIRlet-7.59,60 Although the Lin28b/MIRlet-7/Hmga2 axis regulates the self-renewal of fetal HSCs, Lin28b is silenced after birth.30,61 In agreement, most of our patients did not express LIN28b at detectable levels (data not shown). At present, low-level LIN28B or other alterations, for example, DNA methylation,62,63 and NF45/9064 may be candidates for future investigation.

In conclusion, our study suggests a crucial role of Hmga2 in the progression of MPNs. Amelioration of the severe phenotype in JAK2V617F mice with Ezh2 KO, by inhibition of Hmga2, indicates that HMGA2 may be one of the most important targets upregulated by mutations of PRC2 components and encourages the development of HMGA2-targeted therapy for patients with high-risk MPNs.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Toshio Kitamura (The Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo) for PLAT-E cells, Haruhiko Koseki (RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences) for Ezh2∆/∆ mice, and Minae Takasaki, Ayumi Haneda, Fumiko Miura, and Moe Muramatsu for technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (26860720 and 16K19582 [K.U.], 24591405 and 15K09484 [K.I.], 15K09457 [K.H.-S.], 15K09483 [K.O.], and 25461920 [T.M.]), and Aplastic Anemia & MDS International Foundation (3048-42179) (K.I.).

Authorship

Contribution: K.U. designed the research, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; K.I. designed and supervised the research, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; T.I., K.O., Y.S., P.J.M., and M.B. supervised the study; K.H.-S. performed experiments and analyzed data; Y.H. performed histologic study; T.S., H.O., S. Kimura, and A.S.-N. collected and preserved patients’ samples and analyzed data; Y.N. performed experiments; T.M. analyzed data; S.M. and N.K. examined mutations; K. Shide and K. Shimoda provided mice and interpreted results; S. Koide, K.A., and M.O. performed RNA-seq; A.I. performed RNA-seq and supervised the study; and Y.T. supervised the study and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Kazuhiko Ikeda, Department of Hematology, Fukushima Medical University, 1 Hikarigaoka, Fukushima 960-1295, Japan; e-mail: kazu-ike@fmu.ac.jp.

References

Author notes

The data reported in this article have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GSE87464).

![Figure 1. Progressive MPN in ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F mice. (A) Schematic diagram of the experiment. WT, ΔHmga2 (H), JAK2V617F (J), and ΔHmga2/JAK2V617F (HJ) mice were obtained in predicted Mendelian ratios. The analyses were performed at 12 weeks old. (B) Complete blood cell counts (means ± standard error of the mean [SEM]) and (C) fractions of white blood cells (%) in 5 WT, 7 H, 5 J, and 4 HJ mice. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 calculated by the Tukey-HSD test. (D) May-Giemsa stains of peripheral blood samples (original magnification ×1000). Scale bars indicate 50 µm. (E) Survival periods. N = 9 for WT, 9 H, 12 J, and 7 HJ mice. The P values were calculated by a log-rank test. Bas, basophil; Eos, eosinophil; Hb, hemoglobin concentration (g/dL); Lym, lymphocyte; Mon, monocyte; Neu, neutrophil; OS, overall survival; PLT, platelet count (×1011/L); RBC, red blood cell count (×1012/L); WBC, white blood cell count (×109/L).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/1/15/10.1182_bloodadvances.2017004457/3/m_advances004457f1.jpeg?Expires=1767709776&Signature=bsxoo3S5t3f3RAa5xz7dTdq569PezjdQjEubYPNBAGUmp4LhxWDo8tfFGNt67gADn9hN8SzOAeRjj3Nb4IwY~NxRxUJNWrBRbj~P8NZG2c6stBkBzn3AGqiISga-cJHoOuKW8HIpMj6XdrKuJdCJ~~ZMcblRiweBsFlzaHU3Hwkzk0frlFTovFyQGUKk561vmPBw4SYPtr59hpyKpddJ-2kKbErSGuATubo~31vJCyHjaLcYNvOw3zHvmhSmKKLttfJukkCSe3fvajeCn9DX~fzirfwCp7xnVySGavNXEn2sOVdt8V7m1KvcvioW0MMM8XgIJ1Ah3dwlN0sFhzhvgg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 7. Hmga2 inhibition ameliorates MPN in JAK2V617F mice with Ezh2 KO. (A) Schematic diagram of Hmga2 KO (Hmga2−/+) in JAK2V617F/EZH2fl°x/WT/CRE-ERT (JE). BM cells were collected from JE with HMGA2−/+ (JEH) or HMGA2+/+ (JE) mice and transplanted. Conditional Ezh2 KO was initiated by tamoxifen 4 weeks after transplantation. (B) Complete blood cell counts (means ± SEM). N = 5 for each. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 (Student t test). (C) Spleens at 8 weeks after transplantation with JE, JEH, JE without Cre [JE(Cre−)], and JEH without Cre [JE(Cre−)H] cells. Left, Representative figure. Right, Mean spleen weight. N = 3 for each; ***P < .001 (Turkey-HSD test).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/1/15/10.1182_bloodadvances.2017004457/3/m_advances004457f7.jpeg?Expires=1767709776&Signature=V64leeychKGzAZzEqQQaOYC9MU3mWM1Efr4F5ICcoSEkPsAjoA1j2ZBz3-mzmVMq7xEv39w9cQPYXA~R2~AQvCE8KJUxq1rAMKehg1kCpvA9~fZQMtszhGeHfvnSHCNxumE1jSnH5f3flfmhxHSB4PT8KgQfuTdyRdfn80f~PC6~kVCzO0iYYH4b7hufuCzr7e0DXY4zYTE-sXBBjeCq0n3SzBuV1sRQy2mA3tdkbyjmyxxa4A03fq63hWilO7hDJr1dXBjVe2osCQTFd-8Ned-GeanW3mLvCr7WegVBfMYSBJJynzaI~Ja~FVv4snB5yMD~2944EhMyFfNT5N0iFw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)