Key Points

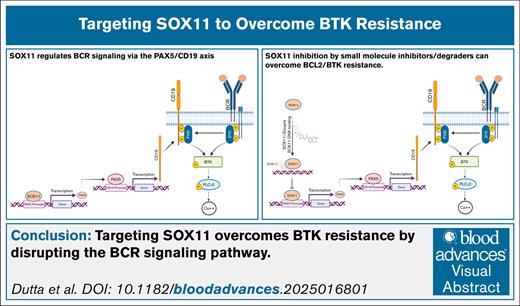

SOX11 contributes to BTK resistance in MCL via the PAX5/CD19 axis directly increasing BCR and downstream signaling pathways.

Targeting SOX11 overcomes BTK resistance by disrupting the BCR signaling pathway, leading to cell death in therapy-resistant MCL cells.

Visual Abstract

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is an incurable subtype of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Despite multiple approved Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (BTKis), resistance to BTKi continues to pose a major clinical challenge. The transcription factor sex determining region Y-box 11 (SOX11) is expressed in most patients with MCL and is associated with poor outcomes. We have previously demonstrated SOX11-dependent B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling in transgenic models of MCL. Here, we report that SOX11 drives BCR signaling via the transcriptional activation of the PAX5/CD19 axis. The translational potential of these results is significant as single-cell RNA sequencing data show that SOX11 is overexpressed in ibrutinib-resistant patients as compared to ibrutinib-sensitive patients. Treatment with the SOX11 DNA-binding inhibitor (SOX11i) significantly reduces the expression of PAX5, CD19, and components of BCR signaling in both ibrutinib-sensitive and ibrutinib-resistant cell lines. Importantly, SOX11i was able to demonstrate cytotoxicity in cells derived from ibrutinib-resistant, venetoclax (B-cell lymphoma 2 [BCL2] inhibitor), and chimeric antigen receptor T-cell–resistant patient-derived xenograft models in vitro. SOX11i treatment reduced the tumor growth in vivo in an MCL xenograft model without any significant toxicity. SOX11 inhibition offers significant potential for patients with MCL, especially BTKi-resistant patients, by targeting upstream resistance mechanisms.

Introduction

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) represents an aggressive B-cell neoplasm within the non-Hodgkin lymphoma classification, characterized by a poor prognosis and median overall survival of ∼6 years.1 The molecular pathogenesis of MCL is primarily driven by 2 key alterations: the characteristic chromosomal translocation t(11;14)(q13;q32) and constitutive activation of the B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling pathway.2,3 Growing experimental and clinical evidence demonstrates that dysregulated BCR signaling serves as a critical oncogenic mechanism in MCL and other B-cell malignancies, promoting both lymphomagenesis and disease progression.3,4 The BCR complex comprises antigen-binding transmembrane immunoglobulin molecules associated with immunoglobulin alfa (Igα)/Igβ (CD79a/CD79b) transmembrane heterodimers, facilitating intracellular signal transduction. Upon antigen engagement, the BCR initiates the assembly of a core “signalosome,” incorporating various signaling and adaptor molecules including multiple nonreceptor protein tyrosine kinases, notably spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK) and Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK). BCR stimulation promotes MCL cell survival and proliferation through BTK-mediated activation of downstream effectors, including AKT (protein kinase B) and NF-κB. BCR signaling inhibitors have shown therapeutic promise in treating B-cell lymphomas.3-6 Covalent BTK inhibitors (BTKis; eg, ibrutinib [IBN], acalabrutinib, and zanubrutinib) and noncovalent BTKis for example pirtobrutinib have been approved for MCL treatment.7-9 There are several mechanisms of intrinsic and adaptive resistance to BTKis, including the acquisition of mutations in BTK itself and the activation of compensatory pathways such as NF-κB and PI3K (phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase)/Protein kinase B (AKT)/mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR).10-12 Despite promising advances in targeted therapies, including BCL2 inhibitors (BCL2i), and CD19-directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy remains an unmet need for treatment strategies capable of inducing durable responses in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL.

Sex determining region Y-box 11 (SOX11) is a neural transcription factor (TF) encoded by the SOX11 gene located on chromosome 2p25. SOX11 is overexpressed in most MCL cases (78%-93%). As a member of the SOXC family of high mobility group TFs, SOX11 belongs to a group that includes SOX4, SOX11, and SOX12.9,13 Numerous studies have shown that SOX11 is a key MCL driver through its regulation of several oncogenic mechanisms. Its presence correlates with a more aggressive disease course and poorer clinical prognosis.14 Our previous studies demonstrated that SOX11 overexpression contributes to MCL pathogenesis by enhancing BCR signaling in transgenic mouse models of MCL.15 However, the precise mechanism by which SOX11 modulated BCR signaling was not known. The present study uses functional and pharmacological approaches to understand the mechanism by which SOX11 modulates the BCR pathway and how SOX11 inhibition can overcome resistance to IBN, which is a critical problem in clinical MCL therapeutics.

Methods

Chemicals and antibodies

IBN and venetoclax (ABT-199) (Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX) and SOX11 DNA-binding inhibitor2 (SOX11i; Compound R [Cpd R]) dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma) and stored at –80°C. Kolliphor(R) HS 15 and N, N-dimethylacetamide (DMA) was acquired from (Sigma). Human anti-mouse IgM was purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove. Supplemental Table 1 lists the used antibodies and their sources.

Cells and cell culture

MCL cell lines, JeKo-1, Z-138, and MAVER-1, were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The JVM-2 cell line was procured from ATCC. JeKo BTK KD cells derived from JeKo-1 cells have intrinsic IBN resistance due to BTK depletion,16 and JeKo-R cells have acquired resistance to IBN.17 Cells Mino-VR, and Rec-VR cells have acquired venetoclax resistance.18 All cell lines were authenticated by short tandem repeat DNA profiling and routinely tested for mycoplasma infection as per standard practice (MycoAlert, Lonza Bioscience). MCL cell lines were maintained in RPMI1640 medium with L-glutamine (Corning) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gemini Bio-Products) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin 100× solution (Gibco). The cells were grown at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2.

Primary patient samples

All patient specimens used in this study were collected in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All research involving human samples was conducted under protocols approved by the Ohio State University Institutional Review Board, with informed written consent obtained, and only deidentified samples were used. Primary MCL cells were isolated from the peripheral blood (PB) of 2 patients with acquired IBN-resistant MCL and 2 patients who had not been previously exposed to IBN. Patient characteristics are detailed in supplemental Table 2. Before using in the experiments, cells were thawed and incubated in a complete RPMI-1640 medium for 3 hours.

SOX11 and CD19 silencing by CRISPR/Cas9 and lentiviral infection

CRISPRevolution synthetic guide RNAs targeting SOX11 (sequence: CCGGGAGGCGCUGGACACGG) and negative control scrambled synthetic guide RNA were procured from Synthego. Each guide RNA was individually complexed with spCas9 protein (Synthego) to form ribonucleoprotein complexes. JeKo-1 MCL cells were washed, pelleted, and gently resuspended in Nucleofector Solution SF, supplemented with Lonza solution and Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) electroporation enhancer buffer (in a 5:1 molar ratio).19 After adding the ribonucleoprotein complex, cells were electroporated using a Lonza 4D-Nucleofector in EO-115 mode. SOX11 short hairpin RNA was purchased from Vector Builder (clone id: VB900063-0018npz and VB900063-0007dkw). For lentiviral infections, 1.0 × 106 exponentially growing MCL target cells (Z-138), cultured in their corresponding mediums with 10% of fetal bovine serum and without antibiotics, were mixed with 1 × 107 TU/mL concentration of lentiviral particles and plated on 24-well plates at 0.5 × 106 cells per mL (polybrene concentration, 5 μg/mL). Cells were centrifuged for 90 minutes at 1000g and 32°C. After centrifugation, 1 mL of complete medium was added to the cells and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2. The same protocols were used to generate CD19 knockout cell lines (JeKo-1, Z-138, and JeKo-1_IBN-R) using the Vector Builder clone ID: VB240709-1579uqf. Infected MCL cells were resuspended in a new complete medium with puromycin selection at a final concentration of 0.5 μg/mL. The efficiency of the knockdown was assessed by western blot (WB) experiments. Single-cell clones were derived by limited dilution from the batch-edited cells and screened for the loss of SOX11 and CD19 expression using western blotting.

SOX11 overexpression

For the stable ectopic expression of SOX11, the SOX11 coding sequence was cloned into a p3XFLAG-CMV-10 expression vector (Sigma-Aldrich), Lentiviral particles were produced by cotransfecting HEK293T cells with the SOX11 vector and packaging plasmids (pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1α lentivector; System Biosciences) using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Virus-containing supernatant was collected 48 and 72 hours posttransfection, filtered through a 0.45-μm filter, and used to transduce target MAVER-1, JeKo-1, and JVM-2 cells in the presence of 8 μg/mL of polybrene. Transduced cells were selected using puromycin at 0.5 μg/mL for 7 days. The ectopic expression of SOX11 was confirmed by immunoblot analysis.

Analysis of published RNA sequencing data

We reanalyzed the single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data from 2 previous studies (Zhang et al and Yan et al).20,21 The scRNA-seq data were processed using the Seurat package (version 5.1.0). Following quality control, gene expression matrices were normalized using a log transformation. Differential expression analysis was conducted to compare the expression of SOX11, PAX5, and CD19 among the 3 groups: normal, BTKi-sensitive (BTKi-S), and BTKi-resistant (BTKi-R). The statistical significance of pairwise comparisons was determined using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Expression correlations among SOX11, PAX5, and CD19 were calculated independently for the BTKi-S and BTKi-R groups using Spearman’s rank correlation. Statistical significance was determined at a threshold of P < .05.

Annexin V/dead cell apoptosis assay

Apoptosis was assessed using annexin V (AnnV) binding to phosphatidylserines, with propidium iodide (PI) serving as a secondary staining dye that selectively permeates dead cells. Briefly, 1 × 106 cells were seeded in 2 mL of complete medium in a 6-well plate. The cells were treated with 20 μM of SOX11i (Cpd R), 10 μM of IBN, and 0.5 μM of venetoclax for 24 hours, whereas untreated cells were used in the control group. After incubation, the cells were collected by centrifugation at 300g for 5 minutes to form a pellet. The pellet was washed twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline and resuspended in 1 mL of 1× AnnV binding buffer (Invitrogen, Oregon). The suspension was transferred to fluorescence-activated cell sorter tubes, and 5 μL of AnnV along with 100 μg/mL of PI dye were added to each sample. The samples were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 15 minutes. Flow cytometry analysis was performed using the Attune NxT Flow Cytometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Cell viability assay

IBN-resistant JeKo-1 (JeKo-1_IBN-R) cells and CD19-depleted JeKo-1_IBN-R cells were treated with increasing concentrations of IBN. Cell viability and IC50 (50% inhibitory concentration) values were determined using the CellTiter-Glo assay (G7572; Promega), as described previously.19 Viability at each drug concentration was calculated and expressed as a percentage relative to DMSO-treated control.

Protein extraction and western blot analysis

Cells were lysed using 1× RIPA lysis buffer (catalog no. 20-188, Merck) with a protease-phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (catalog no. A32961, Pierce, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Lysates were centrifuged at 14 000g for 20 minutes at 4°C. Protein was subjected to 4% to 12 % of sodium dodecyl sulfate-acrylamide gel and transferred onto the polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Bio-Rad). Blocking was conducted for 1 hour at room temperature (catalog no. 2170, ChemiBLOCKER, Millipore Sigma), followed by washing with 1× Tris-buffered saline with Tween. The primary antibody was probed overnight at 4°C, followed by thorough washing before the addition of the secondary antibody. Signals from horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were developed using enhanced chemiluminescence substrates (Clarity Western ECL substrate and ChemiDoc MP Imaging System; Bio-Rad). β-Actin was used as a loading control for normalization. Image J software was used for quantification.

Cell sorting and flow cytometry analysis

B1a cells from Transgenic-SOX11 (Tg-SOX11) and wild-type (WT) mice were sorted from PB. In brief, red blood cells were lysed using BD Pharm Lyse (BD Biosciences) at room temperature for 10 min and centrifuged at 300g. PB was stained with antibodies specific to murine CD19, CD3, B220, CD23, and PAX5 (details are presented in supplemental Table 1). Flow cytometry was performed on a Cytek Aurora. Flow data were then analyzed using Cytobank.

In vivo tumor and PDX models

All animal studies were conducted by the Institute for Animal Studies guidelines at Mount Sinai (New York, NY). Five million Z-138 cells were mixed with 50% Matrigel (BD Biosciences) and injected subcutaneously into the right flank of 4-week-old to 5-week-old Hsd:Athymic Nude-Foxn1 mice (Envigo). When the tumors approached 0.5 to 0.7 cm in diameter at ∼10 to 14 days after the injection of cancer cells, the mice were divided into 2 groups (each experimental group contains n = 6 mice): (1) a SOX11i (Cpd R) group, which received a dose of 75 mg/kg intraperitoneal (IP) twice daily for 14 days and (2) a control untreated group, which received (1.5% DMA volume-to-volume ratio and 9% Solutol HS 15 weight-to-volume ratio) daily. Tumor volume and weight were assessed every 2 days. Tumor volumes were calculated using the following equation: ([V = 0.5 × L × W²]/4)3. The data were expressed as average tumor volume (mm3) per group as a function of time. Animals were sacrificed when the tumor diameter was >1 cm or after loss of >10% body weight per the institutional guidelines.

To establish a novel MCL patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model, 107 cryopreserved cells from patients with MCL were injected intravenously into NOD scid gamma (NSG) mice. Upon reaching the end point criteria, human MCL cells were harvested from the mouse spleens and treated ex vivo with Cpd R.

Immunohistochemical staining

Mouse tumors were fixed in 4% formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Four-micrometer sections were prepared, deparaffinized, and subjected to heat-induced antigen retrieval using citrate buffer (pH 6.4). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by treating the sections with 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol. Indirect immunohistochemistry was conducted using antispecies-specific biotinylated secondary antibodies, followed by avidin–horseradish peroxidase or avidin–alkaline phosphatase, and visualized with Vector Blue or DAB color substrates (Vector Laboratories). When necessary, sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. The primary antibodies used were Ki-67 (catalog no. 7904286; Roche) and PAX5 (catalog no. 12709; Cell Signaling).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software V.10.4.1. All experiments were conducted at least in biological triplicates. Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation of triplicate experiments. The significance of the differences between experimental variables was determined using the Student t test or one-way analysis of variance. The significance of P values is <.05, <.01, or <.001, wherever indicated.

Results

SOX11 regulates CD19 expression and BCR signaling in MCL through PAX5

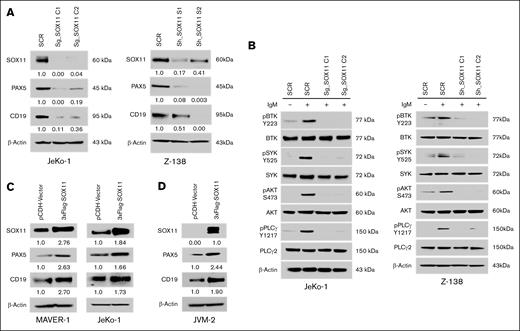

Our earlier studies have demonstrated that PAX5 is a direct transcriptional target of SOX11.13 To elucidate the potential role of SOX11 in BCR signaling, we generated SOX11 knockout clones in 2 SOX11-expressing MCL cell lines, JeKo-1 and Z-138. Western blot analysis demonstrated significant SOX11 depletion in 2 independent knockout clones relative to WT controls (Figure 1A). Notably, SOX11-deficient MCL cells exhibited diminished expression of both PAX5 and CD19. The CD19 receptor is a costimulatory molecule downstream of PAX5 that amplifies BCR signaling.

Genetic depletion of SOX11 reduced the expression of PAX5 and CD19. (A) CRISPR/Cas9- and short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-mediated knockdown of SOX11 resulted in reduced protein levels of PAX5 and CD19 in JeKo-1 and Z-138 cells. SCR refers to the scramble control; sg_SOX11 indicates guide RNAs C1 and C2; sh_SOX11 represents shRNA constructs C1 and C2, respectively. (B) Genetic knockdown of SOX11 led to reduced phosphorylation of downstream BCR signaling components. SOX11-deficient cells were stimulated with 5 μg/mL of IgM for 10 minutes, followed by immunoblot analysis of whole-cell lysates. (C) Overexpression of SOX11, tagged with 3XFlag, induces elevated levels of PAX5 and CD19 expression in the MAVER-1 and JeKo-1 cell lines. (D) Ectopic expression of SOX11 resulted in an increased level of PAX5 and CD19 in the SOX11-negative cell line JVM-2. Immunoblot experiments were performed to validate the results, and β-actin was used as a loading control to ensure equivalent loading and transfer. SCR, scramble control; sg_SOX11, guide RNAs C1 and C2; sh_SOX11, shRNA constructs C1 and C2.

Genetic depletion of SOX11 reduced the expression of PAX5 and CD19. (A) CRISPR/Cas9- and short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-mediated knockdown of SOX11 resulted in reduced protein levels of PAX5 and CD19 in JeKo-1 and Z-138 cells. SCR refers to the scramble control; sg_SOX11 indicates guide RNAs C1 and C2; sh_SOX11 represents shRNA constructs C1 and C2, respectively. (B) Genetic knockdown of SOX11 led to reduced phosphorylation of downstream BCR signaling components. SOX11-deficient cells were stimulated with 5 μg/mL of IgM for 10 minutes, followed by immunoblot analysis of whole-cell lysates. (C) Overexpression of SOX11, tagged with 3XFlag, induces elevated levels of PAX5 and CD19 expression in the MAVER-1 and JeKo-1 cell lines. (D) Ectopic expression of SOX11 resulted in an increased level of PAX5 and CD19 in the SOX11-negative cell line JVM-2. Immunoblot experiments were performed to validate the results, and β-actin was used as a loading control to ensure equivalent loading and transfer. SCR, scramble control; sg_SOX11, guide RNAs C1 and C2; sh_SOX11, shRNA constructs C1 and C2.

To assess the functional impact of SOX11 deficiency on BCR signaling, we evaluated the phosphorylation status of key downstream effectors following surface antigen stimulation. Immunoblot analysis using phospho-specific antibodies against BTK, SYK, AKT, and phospholipase C gamma 2 (PLCγ2) revealed altered signaling profiles between WT and SOX11-knockout cells (Figure 1B). Moreover, the ectopic expression of SOX11 in JeKo-1 and MAVER-1 cells led to an increase in PAX5 and CD19 expression levels (Figure 1C), along with enhanced global tyrosine phosphorylation (supplemental Figure 1A). In addition, the ectopic expression of SOX11 in SOX11-negative JVM-2 cells resulted in a twofold increase in PAX5 and CD19 protein levels (Figure 1D). Notably, PAX5 depletion in SOX11-overexpressing JeKo-1 cells led to reduced CD19 expression (supplemental Figure 1B), suggesting that SOX11 modulates BCR signaling through a PAX5/CD19-dependent mechanism.

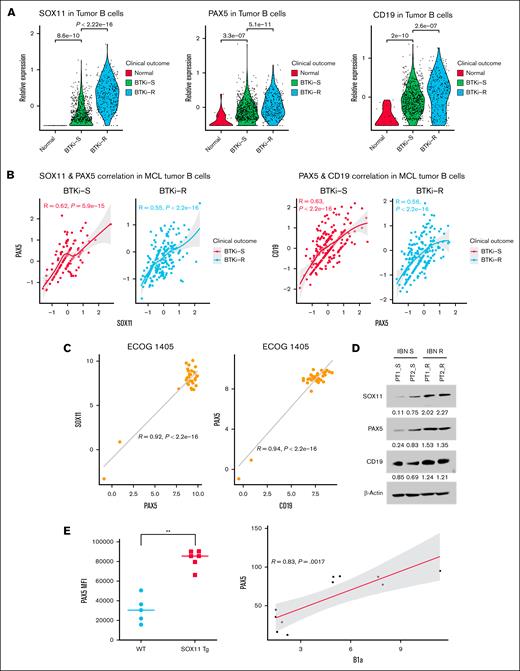

SOX11 expression correlates with PAX5/CD19 in primary MCL and murine models, with higher SOX11 expression in BTK-resistant tumors

We analyzed scRNA-seq data from 2 previous studies,20,21 comprising gene expression profiles of 16 448 tumor B-cells derived from 23 samples collected from 13 patients with MCL across 3 groups: normal, BTKi-S, and BTKi-R. Our analysis revealed that SOX11, PAX5, and CD19 exhibited similar expression trends. SOX11 was overexpressed in MCL cells from IBN-resistant patients compared with SOX11 expression in the cells from IBN-sensitive patients (P < .05) (Figure 2A). Moreover, SOX11 messenger RNA (mRNA) expression correlated with PAX5 (R = 0.62, P < .05) and CD19 expression (R = 0.55, P < .05) in IBN-resistant samples (Figure 2B). We also analyzed the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) 1405 data sheet22 from patients with MCL for relative mRNA expression of SOX11, PAX5, and CD19. The correlation analysis revealed that SOX11 expression positively correlated with PAX5 (R = 0.92, P < .05) and CD19 expression (R = 0.94, P < .05), as shown in Figure 2C.

SOX11-PAX5-CD19 axis correlates with BTKi resistance in MCL. (A) Violin plot showing the relative expression levels of SOX11, PAX5, and CD19 in normal, BTKi-S, and BTKi-R MCL cell samples from the patients. Each dot represents an individual tumor B cell, with colors indicating clinical outcomes. (B) Scatter plot illustrates the correlation between SOX11 and PAX5 (left) and PAX5 and CD19 (right) in BTKi-S and BTKi-R MCL tumor B cells, respectively. A fitted line with 95% confidence intervals is shown. The correlation coefficient and P value are indicated on each plot. (C) SOX11, PAX5, and CD19 mRNA expression are positive correlates in patients’ tumor cells (n = 39, ECOG 1405 data sheets). (D) Immunoblot analysis showing the expression of SOX11, PAX5, and CD19 in primary cells from IBN-sensitive and IBN-resistant patients. β-Actin was used as a loading and transfer control. (E) Increased levels of PAX5 were observed in CD5+, CD19+, and CD23– (B1a) PB mononuclear cells from Tg-SOX11 mice (n = 6) in comparison to WT mice (n = 5) controls. ∗∗, P < .001. ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

SOX11-PAX5-CD19 axis correlates with BTKi resistance in MCL. (A) Violin plot showing the relative expression levels of SOX11, PAX5, and CD19 in normal, BTKi-S, and BTKi-R MCL cell samples from the patients. Each dot represents an individual tumor B cell, with colors indicating clinical outcomes. (B) Scatter plot illustrates the correlation between SOX11 and PAX5 (left) and PAX5 and CD19 (right) in BTKi-S and BTKi-R MCL tumor B cells, respectively. A fitted line with 95% confidence intervals is shown. The correlation coefficient and P value are indicated on each plot. (C) SOX11, PAX5, and CD19 mRNA expression are positive correlates in patients’ tumor cells (n = 39, ECOG 1405 data sheets). (D) Immunoblot analysis showing the expression of SOX11, PAX5, and CD19 in primary cells from IBN-sensitive and IBN-resistant patients. β-Actin was used as a loading and transfer control. (E) Increased levels of PAX5 were observed in CD5+, CD19+, and CD23– (B1a) PB mononuclear cells from Tg-SOX11 mice (n = 6) in comparison to WT mice (n = 5) controls. ∗∗, P < .001. ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

The scRNA-seq data and mRNA expression were further validated at the protein level in primary cells from IBN-sensitive (no prior exposure to IBN) and IBN-resistant patients. Consistently, we observed that IBN-resistant patients exhibited a twofold to threefold higher expression of SOX11 than those who had not received IBN (Figure 2D). These findings were further supported by observations in Eμ-SOX11–overexpressing transgenic mice, which showed higher PAX5 expression in splenic B1a cells compared to that in WT mice (Figure 2E).

SOX11 modulates BCR signaling activity via CD19 in MCL cells

The human CD19 antigen is a 95 kDa transmembrane glycoprotein belonging to the Ig superfamily. It plays a critical role in regulating B-cell signaling thresholds by modulating BCR-dependent signaling. As an essential component in mounting an optimal immune response, CD19 interacts with the BCR and other surface molecules, facilitating direct and indirect recruitment of various downstream protein kinases.

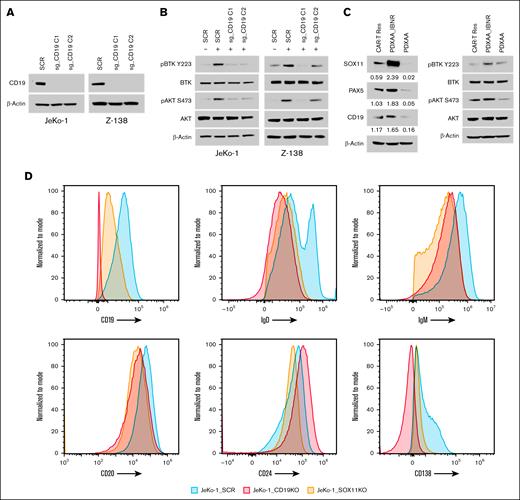

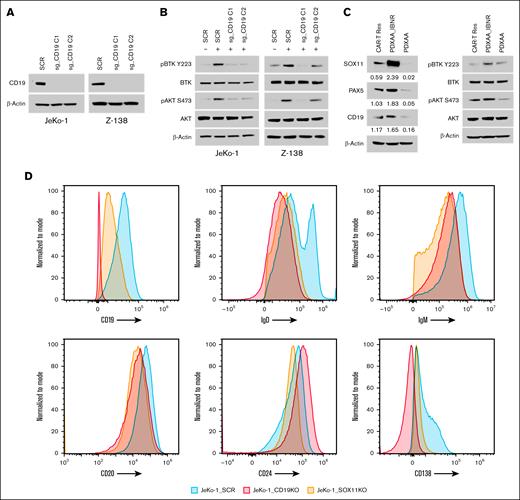

To evaluate the functional role of CD19 in BCR signaling, we generated CD19 knockout SOX11-expressing MCL cell lines, JeKo-1 and Z-138 (Figure 3A). The loss of CD19 in these MCL cells resulted in reduced phosphorylation of BTK (p-BTK) and AKT (p-AKT) (Figure 3B). In addition, we examined the relationship between CD19 expression and p-BTK and p-AKT levels in primary samples from both IBN-sensitive and IBN-resistant patients, as well as in a PDX model. Analysis of these samples revealed that high SOX11 expression correlates with elevated CD19 levels and increased phosphorylation of BTK and AKT (Figure 3C; supplemental Figure 2).

CD19 regulates BCR signaling in a SOX11-dependent manner. (A) CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genetic depletion of CD19 decreased CD19 protein expression in JeKo-1 and Z-138 cells, along with (B) a reduction in the phosphorylation of BTK and AKT. Immunoblot experiments were performed to validate the results, whereas β-actin was assayed to ensure equivalent loading and transfer. (C) Immunoblot experiments were performed in PDX cells, with results indicating that high SOX11 expression leads to an increase in CD19 levels, leading to enhanced downstream BCR signaling. (D) Histograms depict the expression of B-cell and plasma cell surface markers (CD19, CD20, CD24, and CD138), as well as surface IgD and IgM, as measured by flow cytometry in SOX11 and CD19 knockout JeKo-1 cell lines, compared to that in the WT mice. CAR-T Res, CAR-T resistance; SCR, scramble control.

CD19 regulates BCR signaling in a SOX11-dependent manner. (A) CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genetic depletion of CD19 decreased CD19 protein expression in JeKo-1 and Z-138 cells, along with (B) a reduction in the phosphorylation of BTK and AKT. Immunoblot experiments were performed to validate the results, whereas β-actin was assayed to ensure equivalent loading and transfer. (C) Immunoblot experiments were performed in PDX cells, with results indicating that high SOX11 expression leads to an increase in CD19 levels, leading to enhanced downstream BCR signaling. (D) Histograms depict the expression of B-cell and plasma cell surface markers (CD19, CD20, CD24, and CD138), as well as surface IgD and IgM, as measured by flow cytometry in SOX11 and CD19 knockout JeKo-1 cell lines, compared to that in the WT mice. CAR-T Res, CAR-T resistance; SCR, scramble control.

Furthermore, we assessed surface marker expression in SOX11- and CD19-depleted MCL cells. Compared to control cells, SOX11-depleted JeKo-1 cells exhibited reduced surface levels of CD19, IgM, and IgD (Figure 3D), and this trend was also observed in CD19-depleted JeKo-1 cells (Figure 3D). These findings indicate that SOX11 regulates CD19 expression and modulates BCR signaling.

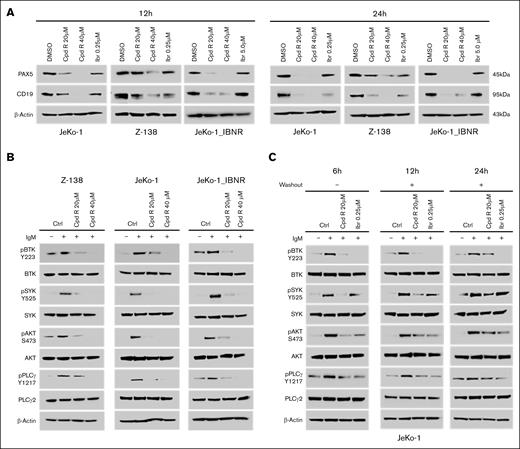

SOX11i treatment of MCL cells in vitro reduces BCR signaling with an associated decrease in CD19 and PAX5 protein expression

The SOX11i (Cpd R) is a DNA-binding inhibitor that binds directly to the SOX11 DNA-binding domain and interferes with DNA binding. To assess the inhibitor's potency in regulating SOX11-mediated BCR signaling through PAX5/CD19, we treated SOX11+ MCL cells with increasing concentrations of Cpd R (0-40 μM) at 2 time points: 12 hours and 24 hours. Treatment with the SOX11i significantly decreased the expression of PAX5 and CD19 protein levels (Figure 4A) in MCL cells. It also reduced the phosphorylation of downstream BCR pathway proteins, namely, p-BTK, p-SYK, p-AKT, and p-PLCγ, without altering total BTK, SYK, AKT, and PLCγ2 levels (Figure 4B) in sensitive Z-138, JeKo-1, and IBN-resistant JeKo-1_IBN-R cell lines, which exhibits increased PI3K-AKT signaling, modeling BCR bypass. In addition, we evaluated SOX11i potency in venetoclax-resistant MCL cells (Mino-VR) (supplemental Figure 3). In washout experiments with JeKo-1 cells (Figure 4C), SOX11i treatment potently reduced the phosphorylation of downstream BCR signaling proteins, with IBN serving as a standard control.

SOX11i (Cpd R) treatment reduced the PAX5 and CD19 protein expression and attenuated downstream BCR signaling in MCL. (A) JeKo-1, JeKo-1_IBN-R, and Z-138 cells were incubated with Cpd R for 12 and 24 hours and IBN at indicated concentrations, after which PAX5 and CD19 were monitored by immunoblotting analysis. (B) JeKo-1, JeKo-1_IBN-R, and Z138 cells were treated for 12 hours and then stimulated with 5 μg/mL of IgM for 10 minutes. Whole-cell lysates were analyzed using immunoblotting. (C) JeKo-1 cells were treated for 6 hours with Cpd R (20 μM) and IBN (0.25 μM), followed by washing, transfer to fresh medium, and collection at the indicated time points. Immunoblotting analysis was then performed. β-Actin was assayed to ensure equivalent loading and transfer. Ctrl, DMSO Control.

SOX11i (Cpd R) treatment reduced the PAX5 and CD19 protein expression and attenuated downstream BCR signaling in MCL. (A) JeKo-1, JeKo-1_IBN-R, and Z-138 cells were incubated with Cpd R for 12 and 24 hours and IBN at indicated concentrations, after which PAX5 and CD19 were monitored by immunoblotting analysis. (B) JeKo-1, JeKo-1_IBN-R, and Z138 cells were treated for 12 hours and then stimulated with 5 μg/mL of IgM for 10 minutes. Whole-cell lysates were analyzed using immunoblotting. (C) JeKo-1 cells were treated for 6 hours with Cpd R (20 μM) and IBN (0.25 μM), followed by washing, transfer to fresh medium, and collection at the indicated time points. Immunoblotting analysis was then performed. β-Actin was assayed to ensure equivalent loading and transfer. Ctrl, DMSO Control.

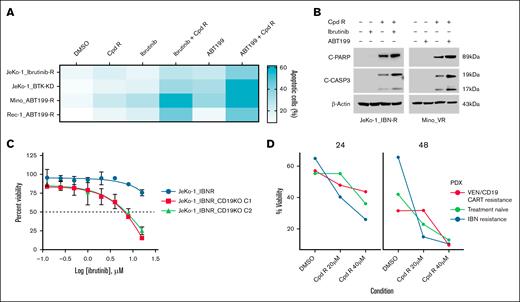

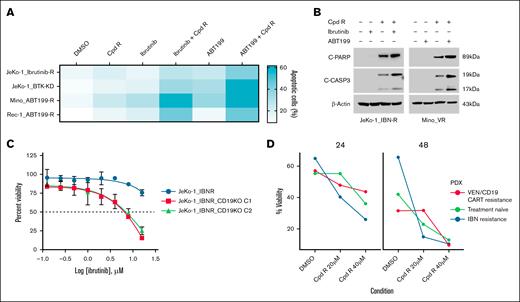

SOX11i treatment promotes apoptotic cell death in IBN and venetoclax-resistant MCL cells

To screen for combinational therapies that could overcome IBN and venetoclax resistance, we treated MCL cells (JeKo-1_IBN-R, JeKo-1_BTK-KD, Mino_ABT-199-R, and Rec-1_ABT-199-R) with SOX11i in combination with IBN and venetoclax, using AnnV/PI double staining and flow cytometry to assess viability. Cotargeting with SOX11i (Cpd R), IBN, and venetoclax overcame IBN resistance in vitro (Figure 5A). Treatment with 20 μM of SOX11i alone for 24 hour induced 20% apoptosis compared to the DMSO control in resistant cells. However, compared to SOX11i treatment alone, combining SOX11i with 10 μM of IBN and 0.5 μM of venetoclax significantly increased apoptosis threefold to 60%.

SOX11i, alone or combined with IBN and venetoclax, enhances apoptotic cell death in resistant MCL cells. (A) Apoptosis was measured using an AnnV/PI assay in IBN-resistant cell lines (JeKo-1_IBN-R and JeKo-1_BTK-KD) and venetoclax-resistant cell lines (Mino_ABT-199-R and Rec-1_ABT-199-R) after 24 hours of cotreatment with Cpd R (20 μM) with IBN (10 μM) or ABT-199 (0.5 μM). (B) JeKo-1_IBN-R and Mino-VR cells were incubated with IBN (10 μM) ± Cpd R (20 μM), and ABT-199 (0.5 μM) ± Cpd R (20 μM) for 24 hours, after which C-PARP and CASP3 cleavage were monitored by immunoblotting analysis. β-Actin was assayed to ensure equivalent loading and transfer. (C) CD19 knockout cells (JeKo-1_IBN-R) were treated with varying concentrations of IBN (0-16 μM) for 48 hours. Cell viability at each drug concentration was then quantified and expressed as a percentage relative to the DMSO control. (D) Patient-derived xenograft cells were treated with Cpd R at the specified concentrations (20-40 μM) for 2 different time points (24 hours and 48 hours). Cell viability was measured following treatment and compared to the DMSO control. VEN, venetoclax.

SOX11i, alone or combined with IBN and venetoclax, enhances apoptotic cell death in resistant MCL cells. (A) Apoptosis was measured using an AnnV/PI assay in IBN-resistant cell lines (JeKo-1_IBN-R and JeKo-1_BTK-KD) and venetoclax-resistant cell lines (Mino_ABT-199-R and Rec-1_ABT-199-R) after 24 hours of cotreatment with Cpd R (20 μM) with IBN (10 μM) or ABT-199 (0.5 μM). (B) JeKo-1_IBN-R and Mino-VR cells were incubated with IBN (10 μM) ± Cpd R (20 μM), and ABT-199 (0.5 μM) ± Cpd R (20 μM) for 24 hours, after which C-PARP and CASP3 cleavage were monitored by immunoblotting analysis. β-Actin was assayed to ensure equivalent loading and transfer. (C) CD19 knockout cells (JeKo-1_IBN-R) were treated with varying concentrations of IBN (0-16 μM) for 48 hours. Cell viability at each drug concentration was then quantified and expressed as a percentage relative to the DMSO control. (D) Patient-derived xenograft cells were treated with Cpd R at the specified concentrations (20-40 μM) for 2 different time points (24 hours and 48 hours). Cell viability was measured following treatment and compared to the DMSO control. VEN, venetoclax.

We further explored the impact of cotargeting IBN/venetoclax and Cpd R on apoptotic signaling in resistant cell lines. JeKo-1 cells resistant to IBN and Mino cells resistant to venetoclax were treated with IBN/venetoclax and Cpd R for 24 hours, and apoptosis induction was assessed by monitoring the cleavage of poly (adenosine 5′-diphosphate-ribose) polymerase (PARP) and caspase-3 (CASP3). SOX11i (Cpd R) alone induced significant PARP cleavage in both resistant cell lines, which was further enhanced when cells were cotreated with IBN/venetoclax and Cpd R. However, PARP cleavage was absent in cells treated with IBN/venetoclax alone or left untreated. Similarly, CASP3 cleavage was markedly increased with cotreatment but was not observed with IBN/venetoclax alone or no treatment (Figure 5B). In addition, we generated CD19 knockout (supplemental Figure 4) BTK-resistant JeKo-1 cells to evaluate their sensitivity to IBN. Our results, presented in Figure 5C, demonstrated that CD19 knockout in JeKo-1_IBN-R cells enhanced their sensitivity to IBN treatment. We also evaluated the therapeutic potential of Cpd R using PDX cells obtained from NSG mice engrafted with PB mononuclear cells from an IBN-resistant patient with MCL and from 1 that progressed after commercial CD19–CAR-T therapy both in leukemic phase and passaged 3 times (details in supplemental Table 2). Previously cryopreserved MCL cells were treated ex vivo with Cpd R at 2 distinct time points and specified concentrations (Figure 5D). Treatment with Cpd R resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in cell viability compared with that in the DMSO control, indicating robust activity even in resistant PDX models.

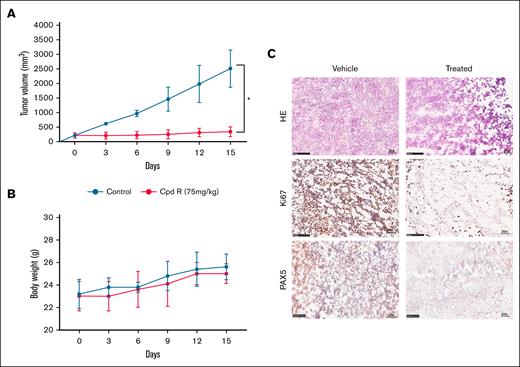

SOX11i treatment inhibits MCL tumor cell proliferation in vivo

Following the superior degree of in vitro activity of SOX11i (Cpd R), its effect was evaluated in vivo using a xenograft model of the MCL cell line, Z-138 in immunocompromised athymic Nude-Foxn1nu mice. Before in vivo studies, we evaluated the pharmacokinetic profiling of Cpd R (details in the supplemental Methods and supplemental Figure 5). Once the tumor volume of the inducted mice reached 100 mm3 to 200 mm3, mice were randomly segregated into 2 groups: (1) vehicle control and (2) CpdR-treated. Each group of animals received IP administration of either the vehicle control or Cpd R at a dose of 75 mg/kg, twice daily for 14 consecutive days. Significant tumor volume reduction was observed in the compound R-treated group compared to the vehicle control. By day 14, tumor volumes in the Cpd R-treated group were significantly smaller, indicating effective inhibition of tumor progression (Figure 6A). Quantitatively, Cpd R treatment reduced tumor volumes by 7.5-fold compared to the vehicle control group. These findings highlight the significant therapeutic efficacy of Cpd R in modulating tumor growth, leading to apoptosis in tumor tissue.

Efficacy of Cpd R in in vivo MCL model. In the subcutaneous model, Z138 cells (5 × 106) were injected in the flank region (n = 6). Ten days after establishing the tumor, mice were randomized and treated with Cpd R (75 mg/kg IP twice daily) for 14 days. The analysis involved monitoring of (A) tumor growth volume and (B) changes in body weight, which were assessed every 3 days. (C) HE staining and immunohistochemistry staining of Ki67 and PAX5 of tumor sections are analyzed between vehicle and drug-treated animals. Original magnification ×20. HE, hematoxylin and eosin.

Efficacy of Cpd R in in vivo MCL model. In the subcutaneous model, Z138 cells (5 × 106) were injected in the flank region (n = 6). Ten days after establishing the tumor, mice were randomized and treated with Cpd R (75 mg/kg IP twice daily) for 14 days. The analysis involved monitoring of (A) tumor growth volume and (B) changes in body weight, which were assessed every 3 days. (C) HE staining and immunohistochemistry staining of Ki67 and PAX5 of tumor sections are analyzed between vehicle and drug-treated animals. Original magnification ×20. HE, hematoxylin and eosin.

To further substantiate these results, ex situ tumor weight quantification was performed at the end of the study (supplemental Figure 6A). Tumor weight in the Cpd R-treated group was reduced by 3.56-fold compared to the vehicle control group, aligning with the observed tumor volume reduction.

In addition to evaluating efficacy, the systemic toxicity of compound R was assessed by monitoring animal body weight throughout the study (Figure 6B). No significant reduction in body weight and no organ-specific toxicity on histology was observed in either group (supplemental Figure 6B), suggesting that IP administration of Cpd R is well tolerated and safe at the given dosing schedule.

To further substantiate these findings, immunohistochemistry for Ki67 (a marker of cellular proliferation) and PAX5 were conducted on tumor tissues from treated mice. The results demonstrated minimal Ki67 and PAX5 presence in the tumor tissue of the Cpd R-treated group compared to the vehicle control group (Figure 6C). This outcome aligns with the observed reduction in tumor growth and density, further validating the therapeutic impact of Cpd R.

Discussion

BTK inhibition has emerged as a key therapeutic approach for treating B-cell malignancies. However, clinical challenges persist as patients frequently exhibit primary resistance to BTKis or develop acquired resistance during treatment.11,23 Ongoing research continues to explore novel therapeutic strategies and targets in this area. TFs regulate gene expression by binding to upstream sequences or distal elements of the transcription start site, playing a critical role in cell proliferation and differentiation.24,25 SOX11, a TF expressed in most patients with MCL, significantly contributes to MCL pathogenesis and influences various cancer-related pathways.2,26 Our present manuscript focuses on a novel dissection of the contribution of SOX11 to the regulation of the BCR signaling pathway, which remains a major approach to treating MCL with multiple approved BTKis. Our results (Figure 1) demonstrate that SOX11 positively regulates BCR signaling by upregulating CD19 expression at the transcriptional level via PAX5. Genetic depletion of SOX11 decreases protein levels of CD19, which leads to reduced activation of BTK and its downstream targets. In addition, single-cell sequencing revealed that SOX11 is overexpressed in BTKi-resistant primary cells, a pattern that is also reflected at the protein level (Figure 2). These findings suggest that CD19 overexpression in these cells is a downstream consequence of SOX11 overexpression, potentially offering a therapeutic opportunity through anti-CD19 CAR-T or bispecific antibody approaches in patients resistant to BTKi. To further clarify the underlying molecular mechanisms, we demonstrated in Figure 3 and supplemental Figure 1 that SOX11 directly regulates the BCR signaling response via the PAX5/CD19 axis, as shown consistently in both cell lines and PDX models. Our findings indicate that SOX11 influences neoplastic transformation beyond the canonical lineage-defining function of the TF PAX5, which preserves B-cell identity and blocks terminal differentiation into plasma cells, maintaining the cells’ capacity for antigen-induced activation and proliferation.

Although TFs are usually considered undruggable targets, several drugs targeting these factors have been developed. The BCL6i FX1 shows promising activity in activated B-cell (ABC)-diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.27 Our SOX11i, Cpd R, demonstrates potent antitumor activity in MCL cell lines.2

Previous work demonstrated that Cpd R synergizes with BTKi. Our current findings extend this result by showing that Cpd R is active in models resistant to BTKis, BCL2i, and even CAR-T therapies, including those with TP53 mutations that are linked to a poor prognosis.28,29 Treatment with Cpd R alone, as well as in combination with IBN and venetoclax, increases apoptosis in resistant cells. To further validate that these resistant cells become more responsive to IBN when combined with Cpd R, we performed a genetic knockout of CD19. This knockout heightened the sensitivity of the resistant cells to IBN treatment (Figure 5). In parallel, resistant cells treated with Cpd R exhibited a reduction in CD19 expression and a subsequent decrease in downstream BCR signaling (Figure 4).

To further assess the effect of Cpd R, we examined the levels of cleaved PARP because CASP3 is the main enzyme responsible for PARP cleavage during programmed cell death.30 Our immunoblotting results confirmed that the combination of Cpd R with IBN and venetoclax increased the level of cleaved PARP in MCL cells that were resistant to either IBN or venetoclax. In addition, Cpd R proved highly effective in overcoming resistance in PDX models with IBN and CAR-T resistance (Figure 5) and showed promising results in in vivo MCL xenograft models.

Importantly, like small-molecule inhibitors, Proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) emerge as effective tools for targeting previously undruggable and mutant proteins, showing high potency and specificity in degrading oncogenic drivers. Many PROTACs have advanced to clinical trials, particularly for hematologic cancers, following promising preclinical results.31-34 We have developed a novel SOX11-specific degrader using PROTAC technology, consisting of a warhead ligand for SOX11, an E3 ubiquitin ligase-binding ligand, and a linker capable of degrading SOX11 protein in MCL cells.35 SOX11-specific degraders could be a paradigm-shifting modality as they appear to work against BTKi and BCL2i-resistant tumors.

In addition, SOX11 is highly correlated with tumor-associated macrophages and CD4+/CD8+ T cells.26 Future research will explore the combination of SOX11 degrader with CAR-T cells and CD20×CD3 bispecific antibodies, focusing on their potential to leverage the immunogenic cell death mechanism. This strategy represents a promising approach for the treatment of patients with relapsed MCL.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the patients and healthy volunteers who provided tissue samples for these studies. The graphical abstract was created with BioRender.com.

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute R01 CA252222, R01 CA244899, R01 CA262754, K12 CA270375, and CA196521 and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, which provides all facilities. This work utilized the Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectrometer Systems at Mount Sinai, acquired with funding from the National Institutes of Health’s Shared Instrumentation Grant (SIG) grants 1S10OD025132 and 1S10OD028504.

Authorship

Contribution: R.P.D. contributed to the conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, supervision, investigation, visualization, methodology, writing of the original draft, project administration, and review and editing of the manuscript; H.-H.L. contributed to the data curation, formal analysis, and review and editing of the manuscript; V.V.L. contributed to the resources, data curation, formal analysis, validation, investigation, methodology, and review and editing of the manuscript; R.P.S. contributed to the data curation, formal analysis, methodology, and review and editing of the manuscript; F.Y. contributed to the data curation, software, investigation, visualization, and review and editing of the manuscript; Y.L. contributed to the data curation, and review and editing of the manuscript; H.U.K. contributed to the resources, methodology, data curation, and review and editing of the manuscript; J.J. contributed to the resources, supervision, and review and editing of the manuscript; L.A. contributed to the conceptualization, resources, formal analysis, supervision, methodology, and review and editing of the manuscript; M.W. contributed to the resources, supervision, and review and editing of the manuscript; S.P. contributed to conceptualization, resources, data curation, supervision, funding acquisition, validation, investigation, methodology, writing of the original draft, project administration, and review and editing of the manuscript; and X.Q. contributed to resource, methodology and review of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.J. is a cofounder and equity shareholder in Cullgen, Inc; a scientific cofounder and scientific advisory board member of Onsero Therapeutics, Inc; a consultant for Cullgen, Inc, EpiCypher, Inc, Accent Therapeutics, Inc, and Tavotek Biotherapeutics, Inc; and the Jin Laboratory received research funds from Celgene Corporation, Levo Therapeutics, Inc, Cullgen, Inc, and Cullinan Therapeutics, Inc. S.P. is a consultant for Grail, Regeneron, Genentech/Roche, and Poseida Therapeutics; is on the advisory board for Grail; and the Parekh Laboratory receives research support from Grail, Celgene/Bristol Myers Squibb Corporation, Caribou Biosciences, imCORE, and Poseida Therapeutics. M.W. is a consultant for Acerta Pharma, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Boxer Capital, Galapagos NV, Genmab, InnoCare, Janssen, Kite Pharma, Lilly, Merck, Physicians Education Resources (PER), Pfizer, and Oncternal; and the Wang Laboratory receives research support from Acerta Pharma, AstraZeneca, Bantam Pharma, BeiGene, BioInvent, Celgene, Genmab, Genentech, Innocare, Janssen, Juno Therapeutics, Kite Pharma, Lilly, Loxo Oncology, Molecular Templates, Nurix Therapeutics, Oncternal, Pharmacyclics, Velosbio, and Vincerx. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Correspondence: Samir Parekh, Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology, The Tisch Cancer Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Hess CSM Building, 1470 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10029; email: samir.parekh@mssm.edu.

References

Author notes

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article, figures, and the supplementary Materials. Original data are available on request from the corresponding author, Samir Parekh (samir.parekh@mssm.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.