Bone disease represents a hallmark feature of multiple myeloma (MM), affecting nearly all patients during the disease course. Morphological imaging techniques play a crucial role in detecting bone disease, whereas functional ones are also fundamental for the differentiation of active from inactive disease and prognostic stratification. The International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) currently recommends whole-body low-dose computed tomography (WBLDCT) as the first-choice imaging technique for the diagnosis of bone disease, whereas magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is recommended in cases without further myeloma-defining events. However, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose–positron emission tomography/CT (18F-FDG–PET/CT) currently represents the standard imaging technique, because it combines both morphological and functional data. Indeed, it allows detection of bone lesions (alternatively to WBLDCT), prognostic stratification, and monitoring of treatment response, being recommended by the IMWG for the assessment of imaging minimal residual disease. The IMPeTUs (Italian Myeloma criteria for PET Use) have proposed a visual descriptive assessment of 18F-FDG–PET/CT, with standardized definitions of metabolic responses. However, the use of further functional imaging techniques is being investigated, with diffusion-weighted (DW)–MRI being related to very promising results regarding both staging and response assessment, to the extent that myeloma response assessment and diagnosis system guidelines have recently proposed a standardization of acquisition, interpretation and reporting of this technique in MM, and the British guidelines consider DW-MRI an alternative to 18F-FDG–PET/CT. This review summarizes current knowledge on the use of functional imaging techniques in MM and their incorporation in recommendations/guidelines, and discusses potential future developments in this setting.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) represents the second most common hematologic malignancy. It is caused by infiltration and proliferation of clonal plasma cells (PCs), primarily within the bone marrow (BM), and it is preceded by asymptomatic precursor stages (monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and smoldering MM [SMM]).1

Among clinical manifestations, myeloma-related bone disease (MBD) is the most common, affecting about 80% of patients with newly diagnosed MM (NDMM) and nearly all patients during disease course. MBD may cause bone pain and skeletal-related events, including pathological fractures, spinal cord compression, and need for radiotherapy/surgical procedures.2,3 Current diagnostic criteria by the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) define MBD as the presence of ≥1 osteolytic lesion (≥5 mm in size) on skeletal surveys, computed tomography (CT), or the CT component of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose–positron emission tomography/CT (18F-FDG–PET/CT). Alternatively, another myeloma-defining event (MDE) is the presence of >1 focal lesion (FL), each ≥5 mm in size, by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI),4 as 2 studies in SMM have shown 70% progression rate to symptomatic MM at 2 years with a median time-to-progression of 13 to 15 months.5,6 Furthermore, disruption of cortical bone with growth of tumor masses arising from skeletal lesions may be causative of paraskeletal disease (PSD), affecting 6% to 34% of patients, with similar incidence at diagnosis and relapsed/refractory MM (RRMM). Conversely, hematogenous spread of malignant PCs to soft tissues may result in extramedullary disease (EMD), affecting 0.5% to 4.8% of patients with NDMM, and 3.4% to 14% of patients with RRMM.7,8

The IMWG recommends whole-body low-dose CT (WBLDCT) as the first-choice/minimum requirement imaging technique, being more sensitive than conventional skeletal radiography in detecting osteolytic lesions9; with 18F-FDG–PET/CT as a potential alternative. In cases without CT-assessed osteolytic lesions and absence of other MDEs, whole-body MRI (WB-MRI), or spine and pelvis MRI (axial skeleton MRI [AS-MRI]), if WB-MRI is unavailable, is recommended to unveil FLs.10 Indeed, MRI showed the highest sensitivity in detecting early bone damage and diffuse BM involvement, differentiating pathological from osteoporotic fractures, and studying cord compression or other neurologic events.11-14

Though conventional morphological imaging techniques represent the mainstay of MBD detection and are available worldwide, functional techniques are useful for prognostic stratification and are mandatory for treatment response evaluation, allowing noninvasive assessment of tissue composition, metabolism, blood flow, or other features related to disease activity. This is even more important in nonsecretory disease, as response cannot be evaluated by monitoring biochemical markers. Indeed, current IMWG guidelines recommend integration of conventional hematologic response with minimal residual disease (MRD) evaluation, both by next-generation sequencing/next-generation flow and imaging. Indeed, potential EMD, spatial heterogeneity, and patchy BM infiltration may hinder MRD assessment on BM, making imaging MRD fundamental. 18F-FDG–PET/CT is currently considered the standard recommended technique in this setting.10,15 However, a role for further techniques is emerging. Herein, we focus on functional imaging in MM, regarding diagnosis/staging, prognostic stratification, and response assessment.

18F-FDG–PET/CT

PET/CT is a dual imaging technique combining functional and morphological assessment. The former is based on evaluation of a radiotracer uptake (with a spatial resolution of ∼5 mm), which allows to study metabolism and proliferation, thus becoming a surrogate marker of disease activity. The latter is due to the CT portion, providing the correct anatomical localization of metabolic foci, and allowing the identification of osteolytic lesions, fractures, PSD, and EMD.

The standard field of view (FOV) in MM usually includes at least skull, AS, upper limbs, and femurs. PET acquisition begins about 60 minutes after radiotracer infusion, and has a duration of 15 to 20 minutes. Last-generation scanners, however, are characterized by longer FOV, reaching significantly higher sensitivity and better spatial resolution. These tomographs require lower scanning time and inferior doses of radiotracer, decreasing radiation exposure. Notably, renal failure and metallic implants, representing contraindications to contrast agent-based techniques and MRI, respectively, are not impediments for PET/CT. The IMWG and the European Association of Nuclear Medicine have published specific guidelines aiming at standardizing acquisition, reporting and interpretation of 18F-FDG–PET/CT in PC dyscrasias.16,17

Interpretation of PET/CT scans is based on both visual/qualitative and semiquantitative analyses. The latter uses a voxel-based parameter called standardized uptake value (SUV); specifically, SUVmax reflects the highest voxel value within the region of interest (ROI). Radiotracer uptake and SUV measurement are influenced by several factors, including patient’s weight and body composition, respiratory motion, tracer’s affinity, time elapsed from injection to image acquisition, location of the ROI, size of the matrix, and specific reconstruction parameters.18 As SUV refers to specific ROI, quantitative volumetric parameters have been introduced to assess the overall disease activity. The most commonly used are metabolic tumor volume (MTV) and total lesion glycolysis. However, their use in MM is currently limited by lack of standardization regarding delimitation of affected areas and definition of disease activity, to quantify tumor burden.19-23

18F-FDG is the standardized most used radiotracer in MM, as it undergoes uptake, phosphorylation, and storage in metabolically active cells. False-negative scans may occur from recent high-dose steroid administration, hyperglycemia, or small skull lesions close to the brain. Furthermore, it was reported that ∼10% of patients have non–FDG-avid disease due to the lack of expression of glucose transporters or glycolysis enzymes, particularly hexokinase-2, potentially being not stable over time and changing during disease course. Conversely, false-positive FLs may result from artifacts (radiotracer accumulation in physiological districts, metallic implants), inflammation, infections, postsurgical areas or biopsies, fractures, or bone remodeling, whereas false diffuse disease (DD) may be caused by anemia or recent radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or growth factors administration.16,24 To overcome these limitations, several alternative tracers have been investigated, with some having potential theranostic implications. However, their use is limited by low availability and expertise, absence of standardization, need for local cyclotron for radiotracers with short half-life, and lack of prospective data.25,26

The Italian Myeloma criteria for PET Use (IMPeTUs) have recently proposed a standardized assessment of 18F-FDG–PET/CT, based on visual descriptive integration of metabolic and anatomical characteristics. The formers are based on Deauville 5-point scale (DS), with active disease being DS ≥4 (Table 1).27

IMPeTUs

| Lesion type . | Site . | Number . | Grading . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diffuse | BM (“A” if hypermetabolism in limbs and ribs) | — | DS |

| F (focal) | S (skull) | X1 (n = 0) | |

| Sp (spine) | X2 (n = 1-3) | ||

| Ex-Sp (extraspine) | X3 (n = 4-10) | ||

| X4 (n > 10) | |||

| L (lytic) | — | ||

| Fr (fractures) | ≥1 | ||

| PSD | DS | ||

| EMD | N (nodal)∗ | ||

| EN (extranodal)† |

| Lesion type . | Site . | Number . | Grading . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diffuse | BM (“A” if hypermetabolism in limbs and ribs) | — | DS |

| F (focal) | S (skull) | X1 (n = 0) | |

| Sp (spine) | X2 (n = 1-3) | ||

| Ex-Sp (extraspine) | X3 (n = 4-10) | ||

| X4 (n > 10) | |||

| L (lytic) | — | ||

| Fr (fractures) | ≥1 | ||

| PSD | DS | ||

| EMD | N (nodal)∗ | ||

| EN (extranodal)† |

Adapted from Nanni et al27 with permission.

For nodal N disease: C, cervical; SC, supraclavicular; M, mediastinal; Ax, axillary; Rp, retroperitoneal; Mes, mesentery; In, inguinal.

For extranodal disease: Li, liver; Mus, muscles; Spl, spleen; Sk, skin; Oth, other.

18F-FDG–PET/CT at staging

Current IMWG guidelines consider 18F-FDG–PET/CT as an alternative to WBLDCT regarding identification of osteolytic lesions as MDE, whereas radiotracer uptake without lytic lesions does not represent a criterion for treatment initiation.4 Its diagnostic role was supported by a study showing that risk of progression to active MM within 2 years for patients with SMM is 87% in cases with osteolytic lesions and 61% in cases of abnormal uptake without alterations in bone architecture, compared with 30% in patients with negative 18F-FDG–PET/CT.28

Several studies regarding 18F-FDG–PET/CT in MM have reported 80% to 100% sensitivity and specificity in detecting bone lesions.12,29-32 Diagnostic performance of 18F-FDG–PET/CT has been evaluated by comparing several imaging techniques. Comparisons with whole-body skeletal radiography survey have demonstrated higher sensitivity of 18F-FDG–PET/CT in MBD diagnosis, except for skull and ribs lesions.12,14,31,33 A prospective comparison between the CT portion of 18F-FDG–PET/CT and WBLDCT revealed high concordance, suggesting the possibility to use the dual technique as the only method for MM evaluation.34

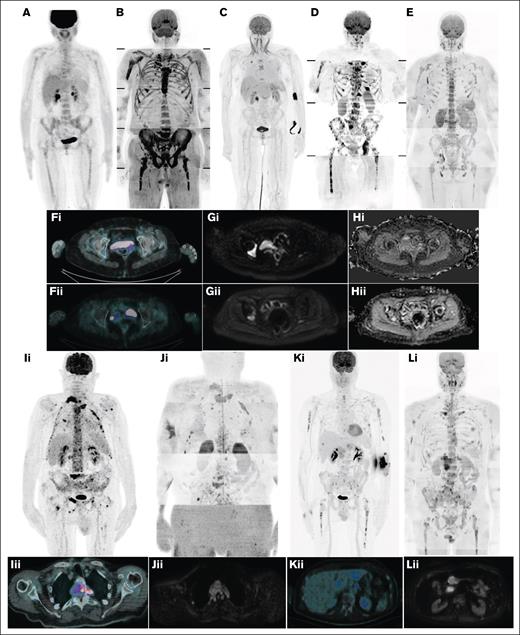

Various studies also compared 18F-FDG–PET/CT with conventional MRI. Regarding DD, lower sensitivity of the former was generally observed. Conversely, FLs comparisons resulted differently based on the specific FOV of MRI, as 18F-FDG–PET/CT detects additional lesions to AS-MRI in ∼30% of patients, whereas diagnostic performance resulted similar or slightly inferior compared with WB-MRI.12,13,32,35,36 However, 18F-FDG–PET/CT has a greater impact on clinical decisions than WB-MRI.36 Conventional MRI was also found to detect earlier disease relapse than 18F-FDG–PET/CT.13 Comparisons to diffusion-weighted (DW)–MRI, described in the following paragraphs, showed inferior sensitivity in detecting FLs, PSD, and DD. Moreover, 18F-FDG–PET/CT resulted in 96% sensitivity and 78% specificity in detecting EMD, being therefore considered the best technique in this setting, except for central nervous system, for which MRI represents the mainstay (Figure 1).37

Disease patterns by 18F-FDG–PET/CT and WB-DW-MRI. (A) DD by 18F-FDG–PET/CT; (B) DD by WB-DW-MRI; (C) focal on DD by 18F-FDG–PET/CT; (D) focal on DD by WB-DW-MRI; (E) micronodular disease by WB-DW-MRI; (F) focal disease by 18F-FDG–PET/CT before (i) and after (ii) treatment; (G-H) focal disease by WB-DW-MRI before (i) and after (ii) treatment; (I) PSD by 18F-FDG–PET/CT (coronal, i; axial, ii); (J) PSD by WB-DW-MRI (coronal, i; axial, ii); (K) EMD by 18F-FDG–PET/CT (coronal, i; axial, ii); and (L) EMD by WB-DW-MRI (coronal, i; axial, ii).

Disease patterns by 18F-FDG–PET/CT and WB-DW-MRI. (A) DD by 18F-FDG–PET/CT; (B) DD by WB-DW-MRI; (C) focal on DD by 18F-FDG–PET/CT; (D) focal on DD by WB-DW-MRI; (E) micronodular disease by WB-DW-MRI; (F) focal disease by 18F-FDG–PET/CT before (i) and after (ii) treatment; (G-H) focal disease by WB-DW-MRI before (i) and after (ii) treatment; (I) PSD by 18F-FDG–PET/CT (coronal, i; axial, ii); (J) PSD by WB-DW-MRI (coronal, i; axial, ii); (K) EMD by 18F-FDG–PET/CT (coronal, i; axial, ii); and (L) EMD by WB-DW-MRI (coronal, i; axial, ii).

18F-FDG–PET/CT in prognostic stratification

Clinical outcomes of patients with MM are extremely heterogeneous, and prognostic stratification is essential to identify high-risk patients.

Several features assessed by 18F-FDG–PET/CT have proven prognostic in different settings. For example, focal FDG uptake without underlying osteolysis in patients with SMM was related to threefold risk of progression and shorter time-to-progression to active MM.38 In patients with NDMM, significant correlation of both progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) with the presence of EMD, high number of FLs (>3) and elevated radiotracer uptake has been displayed by several studies and confirmed by recent meta-analyses.39,40 All these metabolic markers are related with specific biological aspects: EMD highlights metastatic properties with independence of clonal PCs from BM microenvironment and different disease biology; number of FLs is related to tumor burden; SUVmax to proliferation rate and aggressiveness. Notably, different values of SUVmax have been proposed: former experiences identified a cutoff value of ∼4 (mainly 4.2),29,41,42 whereas higher values (eg, >6.3 for FLs or >7.1 for BM diffuse uptake) were proposed in more recent trials.43 These characteristics could be integrated with conventional staging systems (International Staging System [ISS] and Revised ISS [R-ISS])42,44,45 or biological factors with established prognostic role (eg, circulating PCs)46 to improve patients’ stratification. As opposed to the presence of EMD, which has a well-known significant adverse outcome, discordant results have been produced regarding PSD, with some studies proposing it as an independent prognostic factor and others correlating outcomes with the number of PSD lesions.47-50 A prognostic role of volume parameters, including MTV, total lesion glycolysis, and the more recently described intensity of bone involvement and percentage of bone involvement has also been shown.20-23,51-53

The prognostic role of 18F-FDG–PET/CT has also been assessed in RRMM: high number of FLs (with diverse cutoffs ranging from >3 to >10 in different studies), elevated SUVmax (with heterogeneous values, typically higher than NDMM setting), and presence of EMD have been related to patients’ outcome.54-58 Recent studies have also demonstrated a role of baseline 18F-FDG–PET/CT in the setting of novel immunotherapies: PET positivity, PSD, EMD, and high MTV before chimeric antigen receptor T-cell infusion have proven significantly prognostic.59-64

Moreover, positivity of 18F-FDG–PET/CT resulted significantly associated to higher infiltration of BM-PCs, and the presence of high number of FLs to several markers of disease burden, including advanced staging according to Durie-Salmon system or elevated concentration of lactate dehydrogenase and β2-microglobulin.65 Furthermore, a significant link between high SUVmax and the presence of high-risk cytogenetic or molecular alterations, particularly del(17p)/TP53 mutation, has been observed.66 Overall, imaging characteristics maintain a significant independent prognostic role.52

Notably, a prognostic role of disease characteristics assessed through IMPeTUs has been proposed: patients’ outcome has been related to the number of FLs and presence of DD, PSD, and EMD (NDMM); and presence of DD and EMD (RRMM).67-70 Therefore, an integration of IMPeTUs features to Durie-Salmon staging has been proposed (Durie-Salmon Plus), with good concordance to R-ISS.68

18F-FDG–PET/CT in response assessment

The prognostic significance of 18F-FDG–PET/CT in response assessment has been demonstrated in different settings and at several time points. For example, early normalization of the metabolic scan in NDMM (7 days after induction initiation) is correlated with significantly improved PFS and OS, with a reversion of the adverse prognosis related to high number of baseline FLs, whereas persistence of >3 FLs is predictive of inferior outcome. Serial response assessment at different time points clarified that even later normalization and persistence of metabolic inactivity correlate with prognostic improvement, leading to conceptual treatment until suppression of FLs.41,71

Furthermore, multiple studies have demonstrated a significant role of postinduction metabolic response, showing that normalization of 18F-FDG–PET/CT is significantly associated to improved PFS and OS. Conversely, persistence of active FLs and elevated uptake (eg, >4.2) before transplant procedures is predictive of worse prognosis (regardless of hematologic responses).29,30,32,41,42,72,73 “IMAJEM” highlighted that a SUVmax reduction >25% from baseline after induction therapy is related to significant PFS improvement.74

However, the most important time point, currently recommended by IMWG guidelines, is before maintenance therapy.10 Indeed, several studies have demonstrated the fundamental prognostic role of metabolic response assessed 3 months after autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) or before maintenance, showing that normalization of metabolic activity is associated to longer PFS, OS, and time to relapse, and that residual SUVmax is inversely correlated to time to relapse.32,75,76 Moreover, the “CONPET” trial showed that consolidation treatment in patients with deep hematologic response but positive 18F-FDG–PET/CT after induction therapy and ASCT may lead to metabolic remission and likely to improved outcome.77

The prognostic role of metabolic response has also been confirmed in RRMM. Indeed, a significant benefit was shown in patients achieving normalization of 18F-FDG–PET/CT after chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, but data regarding the optimal timing for the assessment of response (1 or 3 months after infusion) are discordant.59,60,63 However, early evaluation of metabolic response in patients receiving T-cell engaging therapies has been associated to potential pseudoprogression due to flare-up phenomenon.78,79

Noteworthy, the lack of standardization regarding definition of responses is a main limitation. Former studies defined disease activity based on heterogeneous SUVmax values.29,30 Nevertheless, because the radiotracer uptake may be influenced by several factors, a comparison to physiologic uptake in anatomic sites (DS) appears reasonable, and IMWG guidelines defined PET negativity as the disappearance of every area of increased tracer uptake, or a decrease to less than mediastinal blood pool SUV or less than surrounding normal tissue.15 However, a joint analysis of “EMN02” and “IFM2009,” based on evaluation of 18F-FDG–PET/CT according to IMPeTUs, has recently found that achievement of DS <4 (uptake lower than liver) for both FLs and BM diffuse uptake represents an independent predictor for improved PFS and OS. Therefore, new standardized definitions of metabolic responses have been proposed (Table 2).80 The applicability of these criteria was recently validated within the “FORTE” trial.81

IMPeTUs and MY-RADS response criteria

| Metabolic response . | Description . | RACs . | Description . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complete metabolic response | Uptake less than or equal to liver activity in BM sites and FLs previously involved, including PSD and EMD (DS 1-3) | RAC1 | Highly likely to be responding:

|

| Partial metabolic response | Decrease in number and/or activity of BM/FLs present at baseline, but persistence of lesion(s) with uptake more than liver activity (DS 4-5) | RAC2 | Likely to be responding:

|

| Stable metabolic disease | No significant change in BM/FLs compared with baseline | RAC3 | No change:

|

| Progressive metabolic disease | New FLs consistent with MM compared with baseline | RAC4 | Likely to be progressing:

|

| RAC5 | Highly likely to be progressing:

|

| Metabolic response . | Description . | RACs . | Description . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complete metabolic response | Uptake less than or equal to liver activity in BM sites and FLs previously involved, including PSD and EMD (DS 1-3) | RAC1 | Highly likely to be responding:

|

| Partial metabolic response | Decrease in number and/or activity of BM/FLs present at baseline, but persistence of lesion(s) with uptake more than liver activity (DS 4-5) | RAC2 | Likely to be responding:

|

| Stable metabolic disease | No significant change in BM/FLs compared with baseline | RAC3 | No change:

|

| Progressive metabolic disease | New FLs consistent with MM compared with baseline | RAC4 | Likely to be progressing:

|

| RAC5 | Highly likely to be progressing:

|

CR, complete response; L-Di, longest diameter; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; TL, target lesion.

Furthermore, several studies (both in NDMM and RRMM, including early experiences with novel immunotherapies) have demonstrated variability between imaging and BM MRD, thus proposing their complementary integration to improve prognostic stratification. Overall, negativity of both 18F-FDG–PET/CT and BM MRD was found to be predictive of superior outcomes.77,81,83-89

WB-DW-MRI

DW imaging (DWI) represents a modern MRI protocol measuring the movement of water molecules within tissues, resulting inversely correlated to its cellular density. Myeloma response assessment and diagnosis system (MY-RADS) guidelines have proposed a standardization of acquisition, interpretation, and reporting of DW-MRI in MM, including its use in response assessment. This protocol uses field strength of 1.5 to 3 Tesla with a WB-FOV (skull vertex to knees) and section thickness of ∼4 to 5 mm. Scanning time ranges from 40 to 60 minutes. It relies on both conventional morphological sequences and functional ones, without need for contrast agents. The formers include T1-weighted, T2-weighted, and short tau inversion recovery sequences, whereas the latter are represented by DWI and T1-weighted sequences with Dixon technique for fat suppression. DWI is based on qualitative parameters (particularly the comparison with adjacent muscle using high b-value images, generally 800-900 s/mm2) and semiquantitative approaches, particularly the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC).82 This parameter has been significantly related to the grade of histological infiltration by malignant PCs and microvascular density.90

Normal BM is generally characterized by ADC values <600 to 700 μm2/s, due the presence of fat yellow marrow (with decreasing values in older people). Conversely, values of viable tumor are generally between 700 and 1400 μm2/s (Figure 2). Four disease patterns have been described: diffuse, micronodular, focal, and focal on diffuse (Figure 1; Table 3).90 As well as evaluation of ADC maps regarding BM infiltration and FLs, a volumetric parameter named total diffusion volume (TDV), calculated by measuring the voxels with abnormal ADC values, has been proposed to estimate tumor burden.91

Relation between ADC values, signal intensity in DWI sequences, and BM cellular density during disease course and response to therapy. MGUS, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Adapted from Dutoit et al92 and Ormond et al.93

DW-MRI disease patterns

| Disease pattern . | Description . |

|---|---|

| Diffuse | Diffuse decreased signal intensity in T1-weighted sequences and increased signal intensity in T2-weighted, STIR, and high b-value DW sequences, with ADC values >600 to 700 μm2/s |

| Micronodular | Widespread nodular areas <5 mm with preserved normal marrow in between |

| Focal | Lesions ≥5 mm with decreased signal in T1-weighted sequences, increased signal in T2-weighted and STIR sequences, hyperintense to background muscle in high b-value images, compatible ADC values (600-1400 μm2/s) |

| Focal on diffuse | Coexistence of focal and DD |

| Disease pattern . | Description . |

|---|---|

| Diffuse | Diffuse decreased signal intensity in T1-weighted sequences and increased signal intensity in T2-weighted, STIR, and high b-value DW sequences, with ADC values >600 to 700 μm2/s |

| Micronodular | Widespread nodular areas <5 mm with preserved normal marrow in between |

| Focal | Lesions ≥5 mm with decreased signal in T1-weighted sequences, increased signal in T2-weighted and STIR sequences, hyperintense to background muscle in high b-value images, compatible ADC values (600-1400 μm2/s) |

| Focal on diffuse | Coexistence of focal and DD |

Adapted from Messiou et al.82

STIR, short tau inversion recovery.

In patients responding to therapies, MRI can depict several signal changes. Indeed, decrease in number and size of FLs, reduced contrast uptake, modifications of BM pattern, increase of signal intensity in T1-weighted sequences due to fat conversion around or within the lesions (“fat dot” and “halo sign”) and decrease of signal intensity in T2-weighted or short tau inversion recovery can be shown by conventional MRI.94 However, WB-DW-MRI displays additional changes, as it integrates Dixon and DWI sequences. The former may highlight fat reconversion, as responding patients are characterized by higher increase of BM fat fraction (FF) than nonresponders.95,96 Furthermore, treatment response is characterized by significant changes of ADC values: tumor necrosis, microbleeding, and edema lead to reduction of cellular density and subsequent increased ADC values in early evaluations, whereas fat reconversion causes decrease of values in later assessments (Figure 2). Heterogeneous cutoff values have been proposed, with a great limitation represented by use of diverse b-values. MY-RADS guidelines have defined 5 response assessment categories (RACs), aimed at evaluating the probability of response or progression,82 a different approach from the categorical responses of IMPeTUs (Table 2). Usefulness and applicability of MY-RADS have been confirmed both in clinical trials and in the real-world setting.97,98

WB-DW-MRI at staging

Use of DW-MRI at baseline staging has been correlated to pooled sensitivity and specificity of 86% and 63%, respectively, with significant superiority over conventional MRI.99 WB-DW-MRI has been compared with WBLDCT, showing a good concordance regarding evaluation of focal involvement, number, and distribution of FLs.100

Furthermore, comparisons to 18F-FDG–PET/CT showed higher sensitivity of WB-DW-MRI regarding detection of FLs (with significant superiority in all anatomic regions, except the skull) and PSD, similar sensitivity in detecting EMD and discordant data regarding assessment of DD.101-103 Inter alia, “iTIMM” (to our knowledge, the only prospective trial published to date in this setting) has demonstrated superiority of WB-DW-MRI compared with 18F-FDG–PET/CT for detection of both FLs (83% vs 60%) and DD (82% vs 17%). Specifically, WB-DW-MRI was significantly more sensitive than the nuclear technique in all skeletal districts, apart from ribs, scapulae, and clavicles.104

Early results from our prospective experience have confirmed the superiority of WB-DW-MRI over 18F-FDG–PET/CT in detecting FLs (76% vs 54%) and PSD (30% vs 20%), whereas a slight concordance in detecting DD was observed.105 However, a retrospective study observed that treatment decisions were not statistically different if combining the 2 techniques, concluding that both are appropriate for initial staging.104

WB-DW-MRI in prognostic stratification

Studies regarding the prognostic role of baseline conventional MRI have demonstrated a significant impact of high number of FLs (>7 with AS-MRI, >25 with WB-MRI) and DD.11,106

Conversely, studies with DW-MRI have highlighted that the presence of ≥3 FLs with product of perpendicular diameters >5 cm2 is associated to inferior PFS and OS, independently from genetic risk, R-ISS, and presence of EMD. The number of FLs lost its prognostic impact after adjustment for size of FLs, emphasizing the role of high tumor burden.107 Furthermore, the presence of DD has been related to several markers of prognosis and disease burden, including high R-ISS, high-risk cytogenetics, greater BM-PC infiltration, higher M-protein concentration, and lower hemoglobin level.104,105 A significant prognostic role has also been reported for elevated TDV and ADC values.108-110

WB-DW-MRI in response assessment

Early studies with conventional MRI had shown a prognostic significance of FLs resolution after therapy,11,111 but high rates of false-positive results (due to the persistence of visible necrotic lesions on morphological sequences) have been reported, and recent trials failed to show a significant correlation with patients’ outcome.32

Conversely, several studies have shown a significant association between the increase of ADC values after treatment and the presence of a biochemical response.112,113 Furthermore, early modifications of FF metrics (after 1 cycle of induction therapy) and a progressive decrease of TDV, resulting directly proportional to the depth of hematologic response, have been observed.114,115

Use of DW-MRI in response assessment has been related to sensitivity and specificity of 78% and 73%, respectively, by a recent meta-analysis.99 Another meta-analysis has demonstrated a non-significant improvement of sensitivity (93% vs 74%), with similar specificity, as compared with conventional WB-MRI without DWI.116 Response assessment using MY-RADS guidelines has been proven prognostic: achievement of RAC1 after ASCT and sustained RAC1 after 1 year have been related to significant improvement of PFS and OS.98,117 Furthermore, significant correlation between greater decrease of relative FF and improved PFS was shown, thereby proposing a complementarity with conventional RACs.118

Comparison to 18F-FDG–PET/CT in response assessment highlighted good concordance.105 However, WB-DW-MRI identifies more residual FLs after treatment, though some FLs are only PET positive, thereby proposing a complementarity of the 2 techniques.84,89 A recent meta-analysis has compared 18F-FDG–PET/CT and WB-MRI (with DWI included in 5/12 studies), demonstrating significantly superior specificity of 18F-FDG–PET/CT (81% vs 56%) and nonsignificantly superior sensitivity of WB-MRI (90% vs 66%).116 Nevertheless, the persistence of positive 18F-FDG–PET/CT after induction therapy or after ASCT was correlated to a more significant impact on PFS than absence of response by WB-DW-MRI.119

Recent studies have also proposed an integration of response assessment by DW-MRI and BM MRD evaluation, showing better outcomes for double-negative patients than patients with positive MRD/imaging and double-positives.84,89,98 Improved outcome in patients with NDMM/RRMM receiving consolidation strategies because of imaging (DW-MRI or 18F-FDG–PET/CT) or MRD positivity was also shown.120Table 4 compares 18F-FDG–PET/CT and WB-DW-MRI.

Main features, advantages, and disadvantages of18F-FDG–PET/CT and WB-DW-MRI in MM

| . | 18F-FDG–PET/CT . | WB-DW-MRI . |

|---|---|---|

| Scanning time | 15-20 minutes (60 minutes after radiotracer infusion) | 40-60 minutes |

| Radiation exposure | 10-25 mSv | None |

| Diffuse BM involvement | Lower sensitivity | Higher sensitivity |

| Detection of FLs | Lower sensitivity | Higher sensitivity |

| Detection of PSD | Lower sensitivity | Higher sensitivity |

| Detection of EMD | Gold-standard technique | Less explored role (apparent similar sensitivity) |

| Prognostic features | >3 FLs, high SUVmax, other quantitative parameters (MTV, TLG, IBI, and PBI) | DD, >3 large (>5 cm2) FLs, high TDV, high ADC values |

| Role in response assessment | Gold-standard technique (IMWG); recent IMPeTUs for definition of metabolic responses (prognostic role of DS <4) | Recommended technique for British guidelines (MY-RADS criteria: prognostic role of RAC1) |

| . | 18F-FDG–PET/CT . | WB-DW-MRI . |

|---|---|---|

| Scanning time | 15-20 minutes (60 minutes after radiotracer infusion) | 40-60 minutes |

| Radiation exposure | 10-25 mSv | None |

| Diffuse BM involvement | Lower sensitivity | Higher sensitivity |

| Detection of FLs | Lower sensitivity | Higher sensitivity |

| Detection of PSD | Lower sensitivity | Higher sensitivity |

| Detection of EMD | Gold-standard technique | Less explored role (apparent similar sensitivity) |

| Prognostic features | >3 FLs, high SUVmax, other quantitative parameters (MTV, TLG, IBI, and PBI) | DD, >3 large (>5 cm2) FLs, high TDV, high ADC values |

| Role in response assessment | Gold-standard technique (IMWG); recent IMPeTUs for definition of metabolic responses (prognostic role of DS <4) | Recommended technique for British guidelines (MY-RADS criteria: prognostic role of RAC1) |

IBI, intensity of bone involvement; PBI, percentage of bone involvement; TLG, total lesion glycolysis.

DCE-MRI

Dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MRI is a functional protocol that allows to study tumor angiogenesis and microcirculation. It is based on high-temporal resolution repeated scanning before, during, and after gadolinium administration, using T1-weighted sequences of dorsolumbar spine. Time-intensity curves represent changes in local perfusion over time, and are based on the assessment of 2 main parameters: amplitude A, reflecting blood volume, and rate constant Kep, reflecting vessel wall permeability. Symptomatic MM is usually characterized by a steep wash-in and first pass (due to immediate flow from intravascular to interstitial space because of marked microvascular density and vessel permeability) and rapid washout (as high cellular density and small interstitial space cause a retrograde flow toward intravascular space). Patients rarely show steep but continuous wash-in, reflecting the persistence of large interstitial space.92,121

DCE-MRI displays a progressive increment of microcirculation from monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance to SMM to MM, with gradual increase of peak enhancement intensity, and decrease of time to peak enhancement intensity.122

Furthermore, higher amplitude A was proven a risk factor for progression of SMM to symptomatic MM, and both amplitude A and Kep were found to have a significant prognostic impact in patients with MM.123-126

Patients responding to therapy usually show significant decrease of wash-in slope and absolute enhancement, likely due to destruction of tumor vascularization. However, a steep wash-in and subsequent plateau may be observed in responders, reflecting increased vascularization due to hematopoiesis regeneration, following anti-MM treatment and stimulating agents.127,128 Moreover, lower values of maximal percentage of BM enhancement, amplitude A, and Kep have been observed in patients responding to therapy.124,129 A recent study has proposed a “combined skeletal score,” based on the integration of morphological and functional MRI data, from both DCE and DWI protocols, to enhance response assessment, particularly for complete response confirmation and prediction of relapse in apparently good-responding patients.128

Though encouraging, DCE-MRI use is limited by lack of clinical validation and standardization. Furthermore, it requires adjustment of results for variables impacting BM vascularization, including body mass index, age, and sex. Another limit is represented by gadolinium administration in patients with severe renal impairment, due to increased risk of nephrogenic systemic sclerosis.130

18F-FDG–PET/MRI

18F-FDG–PET/MRI represents a hybrid imaging technique currently being evaluated in PC dyscrasias.

A retrospective comparison between 18F-FDG–PET, WB-MRI and 18F-FDG–PET/MRI including DWI or DCE protocols showed superiority of 18F-FDG–PET/MRI over PET alone, regarding detection of both FLs (sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of 93%, 97%, and 95%) and DD (sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of 98%, 66%, and 79%), without improvement by adding DCE.131 A prospective trial enrolling patients with NDMM compared the diagnostic performance of this hybrid technique to PET and MRI separately, demonstrating similar accuracy for detection of FLs and DD in symptomatic patients, but superiority of MRI in SMM (allowing detection of FLs in 22% of patients).132

Furthermore, 18F-FDG–PET/MRI was recently evaluated in response assessment: concomitant negativity of PET (DS ≤3) and WB-DW-MRI (RAC1) after ASCT was related to significantly superior PFS than persistent positivity in 1 technique, particularly in case of MRI positivity.133

The main advantages of 18F-FDG–PET/MRI include the concomitant evaluation of morphology, BM cellular density, vascularization, and metabolic activity. However, it is scarcely available, expensive, and requires double expertise.

Conclusions

18F-FDG–PET/CT is currently considered the standard imaging technique in MM, as it combines morphologic and functional data. Indeed, its CT portion represents a recommended technique for MBD diagnosis, whereas the metabolic counterpart has a well-recognized role in prognostic stratification and response assessment, representing the recommended technique in this setting. However, this imaging technique harbors some limitations, with various causes of false-positive or -negative results. Recent years have been characterized by the introduction of novel functional techniques, first among all WB-DW-MRI. Its use in MM appears very promising, as various studies comparing it to 18F-FDG–PET/CT at staging have demonstrated higher sensitivity regarding detection of FLs, PSD, and DD, and similar sensitivity regarding EMD. Furthermore, a significant prognostic role in response assessment was shown, thereby overcoming the major limitation of conventional MRI. Indeed, British guidelines recommend its use as gold-standard imaging technique, and propose it as an alternative to 18F-FDG–PET/CT in response evaluation,134 though IMWG guidelines do not recommend it in response assessment. However, drafting of novel guidelines regarding response assessment is ongoing and it will likely advocate use of only functional imaging techniques (without further need for assessment of plasmacytomas size through conventional morphological techniques), and propose DW-MRI as an alternative to 18F-FDG–PET/CT. Notably, it should be highlighted that use of WB-DW-MRI is currently limited by slight availability and complex evaluation requiring specific expertise.

Furthermore, new software and algorithms, even using radiomics and artificial intelligence (in its declinations of machine and deep learning) are in development with promising results. The main aims are simplification, enhancement of reproducibility, improvement of diagnostic performance, noninvasive prediction of patients’ outcome and assistance to clinical choices.135-139

Future studies will have to further elucidate the complementarity of different functional imaging techniques, to investigate whether one of them might become a new gold standard or they might be alternatively used, and to assess and standardize the role of artificial intelligence tools in MM.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Departments of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, IRCCS Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Bologna, Bologna, Italy, for providing the images used in Figure 1.

Authorship

Contribution: E.Z. designed research, discussed data, supervised the project, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication; and M.T. performed research, discussed data, and drafted the original version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: E.Z. reports honoraria from Janssen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Amgen, and Takeda. M.T. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Elena Zamagni, IRCCS Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Bologna, Istituto di Ematologia “Seràgnoli,” Via Massarenti 9, 40138 Bologna, Italy; email: e.zamagni@unibo.it.

References

Author notes

Individual participant data will not be shared.