We present a novel immunotherapy platform for hematological cancers that exploits fundamental metabolic dysregulation of cancer cells.

Our multivalent, thiol-reactive chemistry covalently links immune adjuvants to free thiols on cancer cell debris induced by chemotherapy.

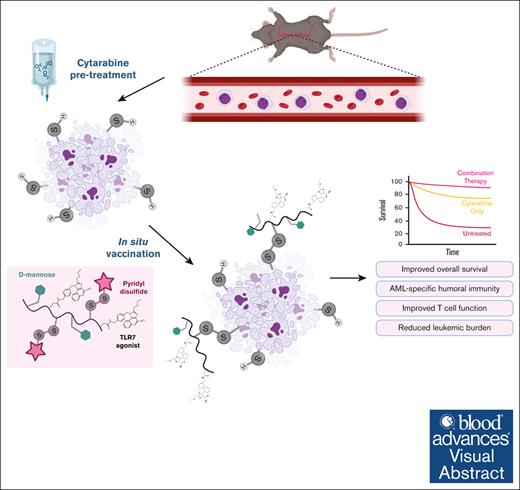

Visual Abstract

Therapeutic vaccination has long been a promising avenue for cancer immunotherapy but is often limited by tumor heterogeneity. The genetic and molecular diversity between patients often results in variation in the antigens present on cancer cell surfaces. As a result, recent research has focused on personalized cancer vaccines. Although promising, this strategy suffers from time-consuming production, high cost, inaccessibility, and targeting of a limited number of tumor antigens. Instead, we explore an antigen-agnostic polymeric in situ cancer vaccination platform for treating blood malignancies, in our model here with acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Rather than immunizing against specific antigens or targeting adjuvant to specific cell-surface markers, this platform leverages a characteristic metabolic and enzymatic dysregulation in cancer cells that produces an excess of free cysteine thiols on their surfaces. These thiols increase in abundance after treatment with cytotoxic agents such as cytarabine, the current standard of care in AML. The resulting free thiols can undergo efficient disulfide exchange with pyridyl disulfide (PDS) moieties on our construct and allow for in situ covalent attachment to cancer cell surfaces and debris. PDS-functionalized monomers are incorporated into a statistical copolymer with pendant mannose groups and TLR7 agonists to target covalently linked antigen and adjuvant to antigen-presenting cells in the liver and spleen after IV administration. There, the compound initiates an anticancer immune response, including T-cell activation and antibody generation, ultimately prolonging survival in cancer-bearing mice.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is the most common type of leukemia, with >20 000 cases every year in the United States alone.1 Despite development and approval of several new therapies specific for genetic mutants in AML (FLT3, IDH, and others), the first-line standard of care remains cytarabine- and anthracycline-based dosing regimens that often result in severe side effects.2,3 Importantly, recently developed advancements in immunotherapy for other cancers, such as antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) and chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, are generally less effective in AML due to the lack of unique antigens that can be safely targeted.4,5 The only US Food and Drug Administration–approved immunotherapy for AML is an ADC using anti-CD33, which was approved in 2017 for newly diagnosed CD33+ AML,6 accounting for roughly 85% to 90% of cases.7 However, its suboptimal safety profile and limited response rates motivate the development of new immunotherapies for patients with AML.8,9

Cytarabine is a cytotoxic cytosine analog that interferes with DNA replication, approved nearly 50 years ago.10 Newly developed drugs that target mutant proteins, such as gilteritinib and olutasidenib, are often dosed in combination with cytarabine and other chemotherapies11,12 to promote sensitivity to cytarabine.13 In other cancers, chemotherapy has been used in combination with immune-stimulating agents to encourage an immune response against tumor antigens released during cell death.14-16 Several studies have explored adjuvants such as toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists, including poly(I:C) (TLR3),17 LPS (TLR4),18 R848 (TLR7/8),19 CpG (TLR9),20 and others,21 for the treatment of leukemia. However, none of these have reached clinical utility, in part, due to ineffective delivery strategies that lead to reduced activity and systemic toxicity.

Our previous work demonstrated an adjuvant delivery platform for in situ solid tumor vaccination based on characteristic dysregulated metabolism of cancer cells.22 Importantly, the platform relies on cancer-intrinsic mechanisms that generate free thiols on cell surfaces and debris, making it applicable to most cancers regardless of antigen profile, an advantage over other targeted immunotherapy approaches. Here, we combine p(Man-TLR7-PDS) therapy with low-dose cytarabine, used to induce cancer cell death and subsequent cellular debris in the blood. We found promising efficacy in its ability to promote an anticancer immune response and prolong survival in the C1498 murine model of AML without exacerbating toxicities. This work serves to further advance a promising, cancer-agnostic immunotherapy.

Methods

Mice and cancer cell lines

Female C57BL/6 mice or B6.SJL-PtprcaPepcb/BoyJ (CD45.1) mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratory at age 8 to 10 weeks. C1498 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured according to instructions, with routine checks for mycoplasma contamination. Tumor inoculations were 106 cells in 100 μL sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) injected IV. Polymer and cytarabine solutions were verified as endotoxin-free before injection via HEK-Blue TLR4 reporter cells (InvivoGen). All animal experiments were approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Monomer and polymer synthesis

All monomers (methacrylamides with side chains of pyridyl disulfide (PDS), mannose, or an imidazoquinoline TLR7 agonist) and polymers were synthesized as previously described.22,23 All polymers are copolymers with hydroxypropyl methacrylamide (HPMA) as an inert monomer and are named only by the presence of functional monomers, except for p(HPMA), which contains no functional monomers.

In vitro p(PDS) binding to C1498 cells

For detection, AZDye 647 DBCO (Click Chemistry Tools) was conjugated to polymer at a 1:1.5 excess and left to react overnight, with purification using 7 kDa molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) desalting column. C1498 cells were incubated on ice with various concentrations of dye-labeled polymer for 60 minutes. In cytarabine pretreatment experiments, cells were treated with various concentrations of cytarabine for 4 hours or treated with 10 μg/mL cytarabine for varying amounts of time before polymer incubation. After polymer incubation, cells were stained for viability using LIVE/DEAD Fixable Violet Dead Cell Stain (Invitrogen), then acquired on BD LSRFortessa, and analyzed via FlowJo.

Effect of cytarabine treatment on C1498 cells in vitro

C1498 cells were treated with varying concentrations of cytarabine for 18 hours. Staining was performed using eBioscience Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (ThermoFisher) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Antibodies are listed in supplemental Table 1. Cells were acquired and analyzed via flow cytometry as described above.

In vitro activity of p(Man-TLR7-PDS)

Spleens from 2 healthy mice were collected and pooled into a single cell suspension, preprepared by mechanically disrupting the spleen through a 70 μm cell strainer (ThermoFisher). Whole splenocytes or C1498 cells were plated in a round-bottom 96-well plate at a concentration of 50 000 cells per well and treated with various concentrations of TLR7 equivalent p(Man-TLR7-PDS) (as quantified by absorbance at 327 nm) or R848 molar equivalent in a volume of 100 μL. Supernatant was collected 8 hours after treatment and analyzed via mouse TNFα ELISA (Invitrogen).

Ex vivo p(Man-PDS) cell binding

Two days after CD45.1 mice (n = 4-5) were inoculated, blood was collected, and white blood cells were isolated by removing plasma via centrifugation then red blood cells with ACK lysing buffer (Gibco). Isolated cells were incubated with labeled p(PDS-Man) for 90 minutes at 37°C. Cell viability was determined using LIVE/DEAD Fixable Violet Dead Cell Stain (Invitrogen). Intracellular staining was performed using eBioscience Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (ThermoFisher) according to manufacturer’s protocol using antibodies listed in supplemental Table 1. Cells were acquired and analyzed via flow cytometry as described above.

Three days after C57Bl/6 mice (n = 4-5) were inoculated, a subset of mice was treated intraperitoneally with cytarabine, and after 4 hours, blood was collected. Whole blood was incubated with labeled p(PDS-Man) for 90 minutes at 37°C. White blood cells were isolated and processed for flow cytometry as described above.

Tissue biodistribution of mannose and PDS polymers

Mice bearing day 18 C1498 were injected IV with fluorescently–labeled polymer variants at a dose of 80 nmol fluorophore. After 8 hours, mice were euthanized and organs were weighed and homogenized using FastPrep tissue homogenizer (MP Bio). Supernatant fluorescence intensity was quantified using Cytation3 Cell Imaging Reader (BioTek). Liver samples consist of the average of 2 ∼100 mg tissue samples from the left lobe, kidney samples are 1 whole kidney, spleen samples are the entire spleen, and plasma samples are ∼50 μL, normalized to actual volume.

Histological analysis of polymer tissue biodistribution

C1498-bearing mice received 2 mg cytarabine intraperitoneally on day 1 after tumor inoculation then 40 μg TLR7 equivalent p(Man-TLR7-PDS) IV on day 2. On day 20, mice were injected with 80 nmol fluorophore of labeled p(Man-PDS). After 6 hours, mice were euthanized, and organs (spleen, kidney, ovary, and liver section) were collected for histological analysis. Before fixing, ovaries were photographed for empirical comparison. Tissues were fixed and cryoprotected for 24 hours each with 1% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS, 15% sucrose in PBS, 30% sucrose in PBS, then 1:1 30% sucrose:OCT Compound (Tissue-Tek). Tissues were then frozen in OCT and sliced into 8 μm sections using Cryostar NX70 (ThermoFisher). Slides were then fixed with ProLong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (ThermoFisher) and imaged with Olympus VS200 Slideview Research Slide Scanner and analyzed in QuPath.

Therapeutic efficacy of p(Man-TLR7-PDS) combination therapy

For each experiment, combination treatment was administered with 2 mg cytarabine intraperitoneally on day 1 after C1498 inoculation followed by 40 μg TLR7 equivalent of p(Man-TLR7-PDS), repeated weekly. p(Man-TLR7-PDS) treatment was compared on a TLR7-equivalent basis for p(Man-TLR7) and on a PDS-equivalent basis for p(Man-PDS). Time between injections and number of weeks of treatment varies as described. Mice were monitored for signs of disease progression and euthanized at humane end points based on symptomology, including body weight.

Histological analysis of leukemic lesions

C1498-inoculated mice were treated with cytarabine and p(Man-TLR7-PDS) combination in week 1 only. On day 20, mice were euthanized, and organs (spleen, 1 kidney, 1 ovary, and ∼100 mg liver section) were collected for histological analysis. Organs were fixed with 2% PFA overnight, embedded in paraffin, and sliced into 5 μm sections before imaging with Olympus VS200 Slideview Research Slide Scanner and image processing in QuPath. Analysis was performed by a pathologist (J.W.K.) blinded to specimen grouping.

Systemic markers of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and organ toxicity

C1498-inoculated mice were treated with cytarabine and p(Man-TLR7-PDS) combination therapy weekly for 3 weeks. Six hours after each polymer injection, blood was collected in heparinized tubes, and plasma was isolated via centrifugation. For blood chemistry analysis, plasma was diluted 4× in sterile water, and albumin, ALT, amylase, total bilirubin, and total protein were quantified using Vet Axcel blood chemistry analyzer (Alfa Wasserman). For proinflammatory cytokine analysis, LEGENDPlex mouse inflammation panel (13-plex) was used (BioLegend) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Endogenous anti-C1498 antibody detection

C1498-inoculated mice were treated with cytarabine and p(Man-TLR7-PDS) combination therapy weekly for 4 weeks. On day 22, the day of final treatment, blood samples were collected in heparinized tubes, and plasma was isolated by centrifugation. C1498 cells were incubated with 10% plasma in PBS from treated mice for 60 minutes on ice, washed twice with PBS, then incubated with AlexaFluor647 anti-IgG (polyclonal, Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 30 minutes at 4°C. Cells were collected and analyzed via flow cytometry.

Circulating and splenic T-cell activation

C1498-inoculated mice were treated with cytarabine and p(Man-TLR7-PDS) combination therapy weekly for 3 weeks. On day 20, 5 days after final treatment, spleens and blood were harvested and processed as previously described. Cells were stained using antibodies listed in supplemental Table 1.

Results

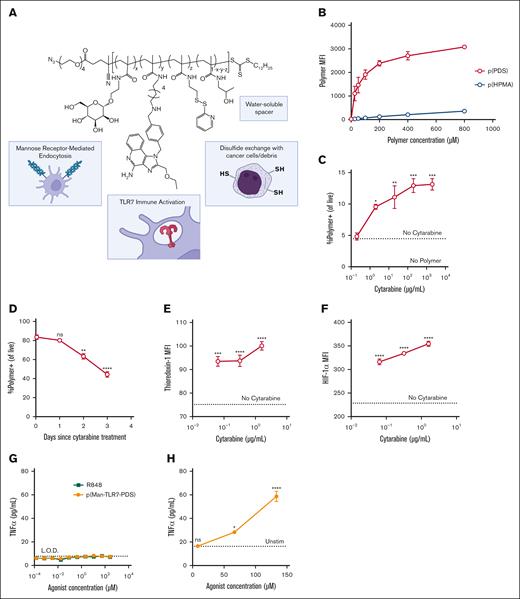

Cysteine-binding polymers synergize with cytarabine to bind AML cells in vitro

Based on our previous work on cancer cell-binding adjuvants,22 we hypothesized that our cysteine-binding polymer could bind C1498 cells, a murine model of AML. Our full construct, p(Man-TLR7-PDS), contains mannose moieties (Man) for uptake by antigen-presenting cells (APCs) via receptor-mediated endocytosis, imidazoquinolinone-based TLR7 agonists (TLR7) for endosomal immune activation, pyridyl disulfide (PDS) moieties for disulfide exchange with free thiols on tumor cell surfaces and debris, and water-soluble HPMA “spacer” monomers (Figure 1A). To confirm that the material can bind free thiols on cell surfaces, we incubated fluorescently–labeled p(PDS) copolymer with C1498 cells on ice (to inhibit endocytosis) and quantified cell binding with flow cytometry. The PDS–containing polymer bound cells more than a nonbinding, molecular weight–matched p(HPMA) polymer (Figure 1B). Furthermore, we confirmed binding is thiol-mediated by preblocking or prereducing cell-surface cysteines (supplemental Figure 1). We then sought to understand how cytarabine affected free thiol accessibility of C1498 cells. Cytarabine pretreatment increased polymer binding efficiency in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1C), and effects were strongest with more recent cytarabine treatment (Figure 1D). Cytarabine treatment also increased levels of thioredoxin-1 (Trx-1) and hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (Figure 1E-F). The key role of both the thioredoxin system24,25 and hypoxia-induced signaling26,27 in the etiology and treatment of leukemias has long been under investigation. Our previous work demonstrated colocalization of polymer retention with Trx-1high regions of solid tumors, and the interplay of the systems28,29 provides insight into the mechanisms of cancer cell binding.

PDS-containing polymers bind C1498 cells aided by cytarabine pretreatment in vitro and activate splenocytes ex vivo. (A) Schematic of full cysteine–binding polymeric glycoadjuvant, p(Man-TLR7-PDS). (B) MFI of concentration-dependent binding of fluorescently-labeled p(PDS) or “spacer” only p(HPMA) to C1498 cells as quantified by flow cytometry. (C) C1498 cells were pretreated with varying doses of cytarabine for 4 hours before polymer incubation. MFI data of cytarabine-dependent binding of labeled p(PDS) are shown. (D) C1498 cells were pretreated with 10 μg/mL cytarabine at various time points before polymer incubation. MFI data of time-dependent binding of labeled p(PDS) are shown. C1498 cells were treated with varying doses of cytarabine for 18 hours and demonstrated dose-dependent increase in intracellular thioredoxin-1 (E) and hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (F). Statistics shown are relative to untreated condition. (G) C1498 cells or (H) whole mouse splenocytes were stimulated for 8 hours with varying concentrations of p(Man-TLR7-PDS) or R848 and evaluated for TNFα secretion. All data are plotted as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM; n = 3). All experiments were repeated with similar results. Statistical analyses were performed using ordinary 1-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; ns, not significant.

PDS-containing polymers bind C1498 cells aided by cytarabine pretreatment in vitro and activate splenocytes ex vivo. (A) Schematic of full cysteine–binding polymeric glycoadjuvant, p(Man-TLR7-PDS). (B) MFI of concentration-dependent binding of fluorescently-labeled p(PDS) or “spacer” only p(HPMA) to C1498 cells as quantified by flow cytometry. (C) C1498 cells were pretreated with varying doses of cytarabine for 4 hours before polymer incubation. MFI data of cytarabine-dependent binding of labeled p(PDS) are shown. (D) C1498 cells were pretreated with 10 μg/mL cytarabine at various time points before polymer incubation. MFI data of time-dependent binding of labeled p(PDS) are shown. C1498 cells were treated with varying doses of cytarabine for 18 hours and demonstrated dose-dependent increase in intracellular thioredoxin-1 (E) and hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (F). Statistics shown are relative to untreated condition. (G) C1498 cells or (H) whole mouse splenocytes were stimulated for 8 hours with varying concentrations of p(Man-TLR7-PDS) or R848 and evaluated for TNFα secretion. All data are plotted as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM; n = 3). All experiments were repeated with similar results. Statistical analyses were performed using ordinary 1-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; ns, not significant.

p(Man-TLR7-PDS) activates endogenous immune cells but not AML cells in vitro

Because PDS-containing polymers bind to C1498 cells, it is important to understand whether p(Man-TLR7-PDS) is immunologically active on those cells. Despite clinical success of TLR7/8 agonists as immune adjuvant therapies,30,31 other reports have suggested a protumorigenic role of TLR7 and TLR8 expression in cancer cells.32,33 Notably, neither our construct nor small molecule TLR7/8 agonists induce secretion of key downstream proinflammatory cytokines by C1498 cells (Figure 1G; supplemental Figure 2).34 The lack of response lead us to explore TLR7 expression in C1498 cells, in which we observed no detectable expression as compared with RAW 264.7 cells (supplemental Figure 3). However, p(Man-TLR7-PDS) does induce dose-dependent TNFα secretion in whole splenocytes, a population of APCs and T cells (Figure 1H). The spleen is a key filtration center for blood and is a common site of metastasis in the C1498 AML model.35

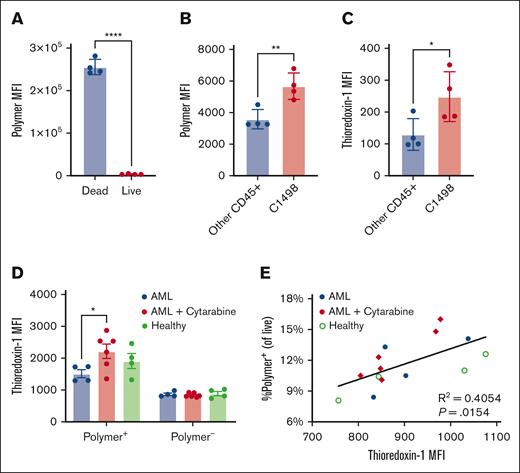

Cysteine-binding polymers preferentially bind Trx-1 expressing C1498 cells ex vivo

To understand which blood cells interact with p(Man-TLR7-PDS) upon IV injection, white blood cells from mice bearing AML were incubated with fluorescently-labeled p(Man-PDS), as we expected both mannose and PDS units were important for cellular biodistribution. The polymer bound significantly more to dead cells than live cells (Figure 2A), although experimentally dead cells make up <5% of cells on average (supplemental Figure 4). This supports our hypothesis that the polymer binds not only live cancer cells but also dying cancer cells and debris, which are generally more immunogenic.36 This rationalizes our combination therapy with cytarabine, which not only enhances the extent of PDS-mediated cell binding but also itself induces cell death. Importantly, the polymer binds preferentially to live C1498 cells as compared with other healthy immune cells (Figure 2B). We further characterized the immune cell populations that bound polymer (supplemental Figure 5; supplemental Figure 6). Finally, C1498 cells had significantly higher levels of Trx-1 (Figure 2C), a finding that corroborates previous reports.24

PDS polymers preferentially bind C1498 cells and debris ex vivo, correlating with thioredoxin expression. (A-C) CD45.1 mice were inoculated with 1 million C1498 cells IV (n = 4). After 2 days, blood was collected, and white blood cells were isolated and incubated with labeled p(PDS-Man). Shown are (A) relative polymer binding to dead vs live cells or to (B) C1498 cells vs other CD45+ immune cells, as well as (C) overall intracellular Trx-1 levels in C1498 cells vs other CD45+ immune cells. (D-E) Separately, C57Bl/6 mice were inoculated with 1 million C1498 cells intravenously (n = 4-5). After 3 days, a subset of mice was treated intraperitoneally with cytarabine, and after 4 hours, blood was collected. Whole blood was incubated with labeled p(PDS-Man). Red blood cells were removed via ACK lysis, and remaining cells were stained for flow cytometry. (D) Intracellular Trx-1 levels were quantified separately in cells that were polymer+ and polymer–. (E) Frequency of polymer+ cells is correlated with Trx-1 expression. All data are plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 3). Statistical analyses were performed using unpaired t tests (A-C), ordinary 2-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons (D), and Pearson correlation. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

PDS polymers preferentially bind C1498 cells and debris ex vivo, correlating with thioredoxin expression. (A-C) CD45.1 mice were inoculated with 1 million C1498 cells IV (n = 4). After 2 days, blood was collected, and white blood cells were isolated and incubated with labeled p(PDS-Man). Shown are (A) relative polymer binding to dead vs live cells or to (B) C1498 cells vs other CD45+ immune cells, as well as (C) overall intracellular Trx-1 levels in C1498 cells vs other CD45+ immune cells. (D-E) Separately, C57Bl/6 mice were inoculated with 1 million C1498 cells intravenously (n = 4-5). After 3 days, a subset of mice was treated intraperitoneally with cytarabine, and after 4 hours, blood was collected. Whole blood was incubated with labeled p(PDS-Man). Red blood cells were removed via ACK lysis, and remaining cells were stained for flow cytometry. (D) Intracellular Trx-1 levels were quantified separately in cells that were polymer+ and polymer–. (E) Frequency of polymer+ cells is correlated with Trx-1 expression. All data are plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 3). Statistical analyses were performed using unpaired t tests (A-C), ordinary 2-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons (D), and Pearson correlation. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

Secondly, we aimed to understand the implications of cytarabine pretreatment on polymer cellular biodistribution, particularly how it relates to Trx-1 levels. Here, we incubated fluorescent p(Man-PDS) with whole blood taken from healthy mice, C1498-inoculated mice, and C1498-inoculated mice that were pretreated with cytarabine. Trx-1 levels were higher in cells that bind polymer as opposed to those that do not, particularly for the cytarabine pretreatment condition (Figure 2D). There was a significant positive correlation between frequency of polymer+ cells with their Trx-1 levels (Figure 2E), further supporting a relationship between polymer binding and thioredoxin activity. There was no difference in residual polymer left in the plasma after whole blood incubation (supplemental Figure 7).

PDS and mannose monomers skew tissue biodistribution

To better understand where the cysteine-binding polymers accumulate upon IV injection, we synthesized molecular weight–matched polymer variants with different compositions, allowing for us to draw conclusions about the influence of each monomer on biodistribution. We IV injected equivalent doses of fluorescently-labeled p(HPMA), p(PDS), p(Man-PDS), and p(Man) into healthy mice and quantified bulk fluorescence of homogenized liver (Figure 3A), kidney (Figure 3B), and spleen (Figure 3C) and plasma (Figure 3D). Our observations followed our hypotheses about the roles of each monomer, in which liver and spleen accumulation were largely driven by mannose due to mannose-receptor expression on hepatocytes and Kupffer cells37 in the liver and dendritic cells and macrophages in the spleen.38 Similarly, kidney distribution and plasma persistence was driven by PDS due to its ability to bind free cysteines in the blood such as cysteine 34 of albumin, increasing the apparent molecular weight, thus increasing residence time in the renal filtration system.39

Both PDS and mannose moieties drive p(Man-TLR7-PDS) tissue biodistribution. (A-D) Mice bearing day 18 C1498 were injected IV with fluorescently–labeled polymer variants (n = 3). After 8 hours, mice were sacrificed and organs were harvested, weighed, and homogenized to determine polymer distribution. Normalized fluorescence intensity values are given for (A) liver, (B) kidney, (C) spleen, and (D) plasma. (E) In a similar, separate experiment, mice were treated with fluorescent p(Man-TLR7-PDS) IV, with or without cytarabine pretreatment 1 day prior (n = 5). Normalized fluorescence of each tissue is given. (F) Fluorescence images of tissue sections showing polymer accumulation (red) and DAPI (gray) (scale bar, 400 μm). All data are plotted as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using ordinary 1-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Both PDS and mannose moieties drive p(Man-TLR7-PDS) tissue biodistribution. (A-D) Mice bearing day 18 C1498 were injected IV with fluorescently–labeled polymer variants (n = 3). After 8 hours, mice were sacrificed and organs were harvested, weighed, and homogenized to determine polymer distribution. Normalized fluorescence intensity values are given for (A) liver, (B) kidney, (C) spleen, and (D) plasma. (E) In a similar, separate experiment, mice were treated with fluorescent p(Man-TLR7-PDS) IV, with or without cytarabine pretreatment 1 day prior (n = 5). Normalized fluorescence of each tissue is given. (F) Fluorescence images of tissue sections showing polymer accumulation (red) and DAPI (gray) (scale bar, 400 μm). All data are plotted as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using ordinary 1-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

p(Man-TLR7-PDS) is retained in APC-rich tissues

With this information on tissue biodistribution, we wanted to determine where our full, therapeutically active construct was retained and whether its biodistribution was affected by cytarabine pretreatment. There was significant accumulation in the kidney, spleen, and liver but very little in the plasma, the levels of which were not altered by cytarabine pretreatment (Figure 3E). This supports our hypothesis that, when injected IV, the polymer quickly exits circulation and is retained in tissues based on its apparent size (based on cysteine binding) and mannose-receptor ligands (based on APC internalization). To corroborate these results, we repeated the experiment but harvested organs for histological analysis. Polymer again accumulated significantly in the spleen, liver, and kidney (Figure 3F). In the spleen, the polymer seemed to localize to the capsule and red pulp more so than the white pulp regions. In the kidney, we observed more significant retention in the outer cortex as opposed to the inner medulla regions.

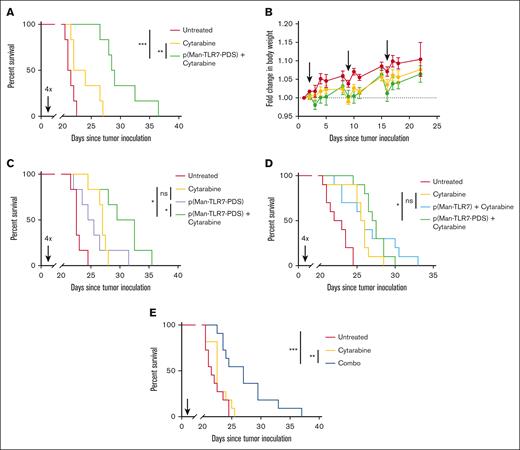

Combination therapy promotes survival in a therapeutic AML model

To understand the therapeutic efficacy of our treatment, we inoculated mice with C1498 cells and administered cytarabine combination therapy weekly at varying polymer doses starting on day 1. We then monitored the mice for signs of disease progression and followed their overall survival. In our first study, we validated the dose of 40 μg TLR7 equivalent polymer as maximally efficacious, with no additional survival benefit and higher risk of toxicity conferred by higher doses (supplemental Figure 8). When treated weekly, 4 doses of combination therapy at our optimized dose significantly prolonged overall survival, both in comparison with untreated and cytarabine–only treated mice (Figure 4A). During this study, there was no significant deviation in body weight associated with treatment (Figure 4B). We also compared combination therapy with single-agent efficacy of p(Man-TLR7-PDS). Combination therapy offered significant survival benefit over the polymer treatment alone, which itself was not beneficial over cytarabine alone (Figure 4C). Furthermore, we sought to illustrate the importance of the cysteine-binding mechanism of polymer therapy by comparing cytarabine therapy with either p(Man-TLR7-PDS) or a molecular weight–matched, nonbinding control polymer p(Man-TLR7). Only p(Man-TLR7-PDS) plus cytarabine therapy, not nonbinding polymer combination therapy, conferred survival benefit over cytarabine treatment (Figure 4D). A similar study showed that combination therapy with a nonadjuvanted polymer variant, p(Man-PDS), did not increase overall survival vs cytarabine (supplemental Figure 9). Finally, we evaluated the efficacy of combination therapy in a single injection setting, in which treatment was administered once near the onset of disease. Here also, survival is significantly prolonged with treatment (Figure 4E).

p(Man-TLR7-PDS) combination therapy significantly enhances overall survival. C57Bl/6 mice were inoculated with 1 million C1498 cells IV (day 0). For each experiment, combination treatment was administered with 2 mg cytarabine on day 1 followed by 40 μg TLR7 equivalent of p(Man-TLR7-PDS), repeated weekly. Time between injections and number of weeks of treatment varies as described. (A-B) Combination treatment was separated by 24 hours and administered for 4 weeks (n = 6), and mice were tracked for (A) overall survival and (B) change in body weight through first event. (C) Combination treatment was compared in its survival benefit to single-agent efficacy of p(Man-TLR7-PDS) (n = 6). (D) p(Man-TLR7-PDS) combination treatment was compared in its survival benefit to an equivalent TLR7 dose of molecular weight–matched, nonbinding control polymer p(Man-TLR7) in combination with cytarabine. Data are pooled from 2 separate experiments in which combination treatment was separated by 24 hours and administered for 4 weeks (n = 5 each replicate; 10 total). (E) Combination treatment was separated by 6 hours and administered for 1 week and evaluated for its survival event in a single injection context. Data are pooled from 2 separate experiments with identical conditions (n = 5-6 each replicate; 11 total). All data are plotted as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using pairwise log-rank (Mantel-Cox) curve comparison for survival with multiple testing correction. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ns, not significant.

p(Man-TLR7-PDS) combination therapy significantly enhances overall survival. C57Bl/6 mice were inoculated with 1 million C1498 cells IV (day 0). For each experiment, combination treatment was administered with 2 mg cytarabine on day 1 followed by 40 μg TLR7 equivalent of p(Man-TLR7-PDS), repeated weekly. Time between injections and number of weeks of treatment varies as described. (A-B) Combination treatment was separated by 24 hours and administered for 4 weeks (n = 6), and mice were tracked for (A) overall survival and (B) change in body weight through first event. (C) Combination treatment was compared in its survival benefit to single-agent efficacy of p(Man-TLR7-PDS) (n = 6). (D) p(Man-TLR7-PDS) combination treatment was compared in its survival benefit to an equivalent TLR7 dose of molecular weight–matched, nonbinding control polymer p(Man-TLR7) in combination with cytarabine. Data are pooled from 2 separate experiments in which combination treatment was separated by 24 hours and administered for 4 weeks (n = 5 each replicate; 10 total). (E) Combination treatment was separated by 6 hours and administered for 1 week and evaluated for its survival event in a single injection context. Data are pooled from 2 separate experiments with identical conditions (n = 5-6 each replicate; 11 total). All data are plotted as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using pairwise log-rank (Mantel-Cox) curve comparison for survival with multiple testing correction. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ns, not significant.

Formation of tumor lesions is reduced by combination therapy

Beyond survival, we wanted to understand if our combination therapy altered extravascular cancer cell infiltration, a common observation in the C1498 model.40 On day 20, after 3 weeks of treatment, the ovaries were drastically enlarged with untreated disease by eye, and our combination therapy reduced the size to nearly healthy levels (Figure 5A). The combination therapy significantly reduced liver weight to nearly healthy levels (Figure 5B) (from a separate experiment). Finally, we performed hematoxylin and eosin staining of ovary, liver, and kidney tissues to visualize incidence of cancer cell infiltration (Figure 5C), as reported by others.41-43 Specifically, there is clear tumor formation in the ovaries and also leukemic infiltration in the surrounding periadnexal soft tissue of untreated but not combination-treated mice. We also observed leukemic colonization in the liver, in which there is a distinct pattern of periportal infiltration with subcapsular migration, again only in the untreated mice. The kidneys themselves were relatively unchanged by disease, but there was renal hilar adipose tissue involvement in the untreated group but not in combination-treated group. We can reasonably conclude that there is no histologic evidence of previous or active leukemic involvement in any of the mice that received combination therapy.

Combination therapy prevents extravascular leukemic burden. (A) Combination treatment was separated by 24 hours and administered for 1 week (n = 2-4). On day 20, ovaries were photographed for macroscopic size comparison. (B) Combination treatment was separated by 24 hours and repeated for 3 weeks (n = 5). On day 20, total liver weights are compared. (C) Representative ovary, liver, and kidney histology with H&E staining on day 20. Scale bars as noted in the figures (250 μm for ovary; 100 μm for periadnexal soft tissue, liver [high power], and renal hilar adipose tissue; 1 mm for liver [low power] and kidney). H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

Combination therapy prevents extravascular leukemic burden. (A) Combination treatment was separated by 24 hours and administered for 1 week (n = 2-4). On day 20, ovaries were photographed for macroscopic size comparison. (B) Combination treatment was separated by 24 hours and repeated for 3 weeks (n = 5). On day 20, total liver weights are compared. (C) Representative ovary, liver, and kidney histology with H&E staining on day 20. Scale bars as noted in the figures (250 μm for ovary; 100 μm for periadnexal soft tissue, liver [high power], and renal hilar adipose tissue; 1 mm for liver [low power] and kidney). H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

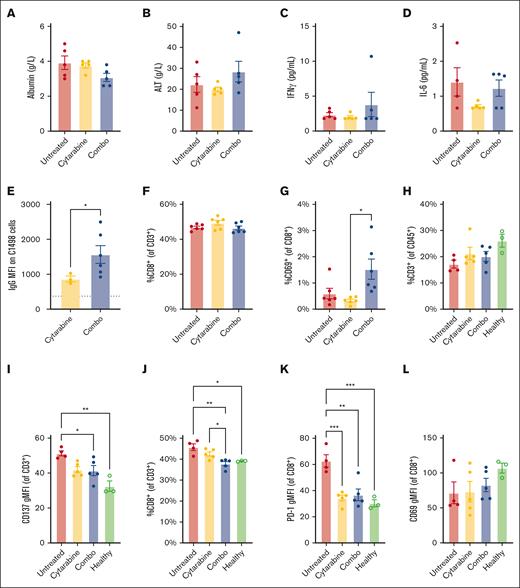

Clinically relevant toxicity markers are unchanged by p(Man-TLR7-PDS) combination therapy

A limitation of immunotherapy involving immune-stimulating adjuvants is their potential to induce CRS and cause organ toxicity. To evaluate the risk of our therapy, we treated mice with combination therapy weekly for 3 weeks and measured levels of clinically relevant markers of toxicity in the plasma after treatment. There were no significant changes in levels of serum albumin (Figure 6A) as a metric of kidney toxicity and alanine amino-transferase (ALT) (Figure 6B) as a marker of liver toxicity. The lack of apparent toxicity to the kidney and liver are particularly important as our molecule accumulates in those tissues. We also quantified levels of amylase to understand pancreatic toxicity and total bilirubin and total protein to corroborate our findings in liver and kidney function, respectively, and again found no changes relative to untreated mice (supplemental Figure 10). Simultaneously, we evaluated blood levels of proinflammatory cytokines that would indicate CRS. There was no significant upregulation in the key inflammatory mediators interferon gamma (Figure 6C) and IL-6 (Figure 6D), key cytokines downstream TLR signaling. In several other cytokines and chemokines associated with CRS, we observed no changes induced by our treatment (supplemental Figure 11).

p(Man-TLR7-PDS) combination therapy is well-tolerated and induces distinct immune phenotype. C57Bl/6 mice were inoculated with 1 million C1498 cells IV (day 0). For each experiment, combination treatment was administered with 2 mg cytarabine on day 1 followed by 40 μg TLR7 equivalent of p(Man-TLR7-PDS), repeated weekly. Time between injections and number of weeks of treatment varies as described. (A-D) Combination treatment was separated by 24 hours and repeated for 3 weeks (n = 5). On day 16 (week 3), 6 hours after polymer injection, serum was collected for analysis. Serum was analyzed for changes in (A) albumin, (B) alanine transferase, (C) inflammatory mediators interferon gamma, and (D) IL-6 levels. (E) Combination treatment was separated by 24 hours and administered for 4 weeks (n = 6). On day 23, endogenous C1498–specific IgG was quantified via on-cell ELISA for surviving mice. (F-G) Combination treatment was separated by 24 hours and repeated for 3 weeks (n = 6). On day 20, blood was analyzed for (F) total CD8+ T cells and (G) their CD69 expression. Experiment was repeated with similar results. (H-L) Combination treatment was separated by 24 hours and repeated for 3 weeks (n = 5). On day 20, spleens were harvested and analyzed via flow cytometry relative to healthy control mice (n = 3). T-cell subsets were compared, including (H) total CD3+ T-cell compartment, (I) CD137 expression on total T cells, (J) fraction of T cells that are CD8+, and (K) PD-1 and (L) CD69 expression on CD8+ T cells. All data are plotted as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using unpaired t tests (A), Pearson correlation (B), and ordinary 2-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons (C-K). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01. IL-6, interleukin-6.

p(Man-TLR7-PDS) combination therapy is well-tolerated and induces distinct immune phenotype. C57Bl/6 mice were inoculated with 1 million C1498 cells IV (day 0). For each experiment, combination treatment was administered with 2 mg cytarabine on day 1 followed by 40 μg TLR7 equivalent of p(Man-TLR7-PDS), repeated weekly. Time between injections and number of weeks of treatment varies as described. (A-D) Combination treatment was separated by 24 hours and repeated for 3 weeks (n = 5). On day 16 (week 3), 6 hours after polymer injection, serum was collected for analysis. Serum was analyzed for changes in (A) albumin, (B) alanine transferase, (C) inflammatory mediators interferon gamma, and (D) IL-6 levels. (E) Combination treatment was separated by 24 hours and administered for 4 weeks (n = 6). On day 23, endogenous C1498–specific IgG was quantified via on-cell ELISA for surviving mice. (F-G) Combination treatment was separated by 24 hours and repeated for 3 weeks (n = 6). On day 20, blood was analyzed for (F) total CD8+ T cells and (G) their CD69 expression. Experiment was repeated with similar results. (H-L) Combination treatment was separated by 24 hours and repeated for 3 weeks (n = 5). On day 20, spleens were harvested and analyzed via flow cytometry relative to healthy control mice (n = 3). T-cell subsets were compared, including (H) total CD3+ T-cell compartment, (I) CD137 expression on total T cells, (J) fraction of T cells that are CD8+, and (K) PD-1 and (L) CD69 expression on CD8+ T cells. All data are plotted as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using unpaired t tests (A), Pearson correlation (B), and ordinary 2-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons (C-K). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01. IL-6, interleukin-6.

p(Man-TLR7-PDS) combination therapy promotes humoral immune function

To understand the effects of p(Man-TLR7-PDS) therapy on humoral responses, we quantified the induced antibody response after 4 weeks of treatment. On day 22 of the study, endogenous C1498-specific IgG in survivors significantly rose relative to the cytarabine-only controls (Figure 6E). This result suggests the possible involvement of antibody–dependent cellular cytotoxicity,44 although this was not the focus of our study. In a similar experiment, IgG isotypes of anti-C1498 antibodies trended toward IgG2a skewing, as evidenced by an increase in IgG2a to IgG1 ratio (supplemental Figure 12). IgG2a is the isotype of IgG that is most effective in directing antibody–dependent cellular cytotoxicity.45

p(Man-TLR7-PDS) combination therapy promotes T-cell immune activation

We investigated cellular immunity via CD8+ T-cell activation by treating C1498-bearing mice with combination therapy for 3 weeks and characterized blood cell populations on day 20 (supplemental Figure 13). Although there was no change in the proportion of total CD8+ T cells relative to controls (Figure 6F), the frequency of those CD8+ T cells expressing CD69 more than doubled with the combination therapy (Figure 6G). We looked at CD69 expression on CD4+ T cells and CD25 expression on both subsets and did not observe any significant differences (supplemental Figure 14). CD69 is commonly viewed as an early activation marker, but its expression is also associated with tissue-resident memory fate.46 In the C1498 model, others have quantified CD69 expression as a function of T-cell antigen experience47 and activation.48

We also characterized splenic T-cell activation (supplemental Figure 15). Although the frequency of total T cells did not change significantly across groups (Figure 6H), CD137 expression decreased on total T cells with our treatment (Figure 6I). CD137 promotes T-cell survival and expansion in a healthy context, however, CD137 in leukemia and lymphoma can have an overall immunosuppressive effect, inhibiting T-cell activation and promoting the growth of malignant cells.49,50 The proportion of CD8+ T cells decreased with our treatment, similar to levels found in healthy mice (Figure 6J), which could suggest an expansion of CD4+ T cells or an exodus of CD8+ T cells to other sites of leukemic infiltration.51,52 Those CD8+ T cells present expressed lower levels of programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) with treatment than without (Figure 6K). PD-1 has been reported as a key immune evasion mechanism in the C1498 model, with PD-1 knockout mice having improved survival outcomes.53 Curiously, unlike those in the blood, splenic total CD8+ T cells did not show altered levels of CD69 expression (Figure 6L). Additionally, we characterized the CD8–CD3+ subset as a proxy for CD4+ T cells and observed several trends, including reduction of CD25 expression (supplemental Figure 16), suggesting reduced regulatory T cells. Regulatory T cells are key for the immune evasion of AML cells in both the murine C1498 model54,55 and human disease.56

Discussion

In this work, we leveraged the characteristic redox imbalance of AML25,57,58 to preferentially adjuvant tumor cells and debris via their exofacial free thiols for in situ vaccination via IV administration. We found that the redox imbalance is further exacerbated by cytarabine treatment,59 associated with Trx-1 expression, improving binding of our polymer to cancer cells. Once bound, the polymer traffics with the tumor cells and debris to APCs in the liver and spleen, in which mannose moieties enable receptor-mediated endocytosis and TLR7 agonists drive immune activation. We observe C1498-specific humoral immunity and broadly improved cellular immunity with our combination therapy, ultimately promoting improved survival. This presents a promising advancement in targeted immunotherapy over other antigen-targeted immunotherapy approaches, which have failed to see the clinical success in AML that they have in other cancers such as B-cell lymphomas.60,61

Our work used the C1498 model of murine AML, which, despite some limitations in recapitulating human disease, is widely accepted as a preclinical model.35 Importantly, many of the leukemic features are preserved between mice and the human disease,62 and several of our experimental readouts share key importance with patient pathology. For example, high expression of PD-1 is associated with poor overall survival in patients with AML,63 and our combination therapy induces a significant reduction in PD-1 expression on splenic CD8+ T cells. Similarly, CD137 can induce differentiation of primary AML cells,64 so, our reduction of CD137 levels may be clinically meaningful.

ADCs have been explored to target immune-activating drugs such as TLR agonists to cancer cell surfaces to induce a vaccinal response.65-67 This approach can, however, be confounded by development of antidrug antibodies,68,69 because the ADC is essentially a conjugate vaccine for the targeting antibody itself. Here, we sought to use a nonprotein polymer to target both a TLR agonist and an APC endocytosis moiety to cancer cells in a manner that does not require identification of a cell-surface tumor antigen. We show that combination treatment with low-dose cytarabine leads to significant survival benefit after IV administration. This approach may have applicability in other hematological malignancies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the University of Chicago Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Facility, Mass Spectrometry Facility, Soft Matter Characterization Facility, Cytometry and Antibody Technology Facility, Human Tissue Resource Center, Integrated Light Microscopy Core, and Animal Resource Center.

This work was supported by the Chicago Immunoengineering Innovation Center of the University of Chicago and by the National Institutes of Health (CA253248).

Authorship

Contribution: A.J.S. and J.A.H. conceived the project; A.J.S., A.M., A.T.A., and J.A.H. designed the research strategy; A.J.S. and S.G. performed in vitro work; A.J.S., K.C., T.N.B., K.C.R., A.T.A., A.L.L., and A.S. performed in vivo experiments; K.C.R., A.L.L., and AM advised data analysis; J.K. analyzed histology data; J.A.H. supervised the work; A.S. and K.C.R. wrote the manuscript with contributions from K.C., T.N.B., K.C.R., A.T.A., A.M., and J.A.H.; and all authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.J.S. and J.A.H. are inventors on a patent for the University of Chicago. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jeffrey A. Hubbell, University of Chicago, 5640 S Ellis Ave, Room 369, Chicago, IL 60637; email: jhubbell@uchicago.edu.

References

Author notes

Additional data are available upon request from the corresponding author, Jeffrey A. Hubbell (jhubbell@uchicago.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![Combination therapy prevents extravascular leukemic burden. (A) Combination treatment was separated by 24 hours and administered for 1 week (n = 2-4). On day 20, ovaries were photographed for macroscopic size comparison. (B) Combination treatment was separated by 24 hours and repeated for 3 weeks (n = 5). On day 20, total liver weights are compared. (C) Representative ovary, liver, and kidney histology with H&E staining on day 20. Scale bars as noted in the figures (250 μm for ovary; 100 μm for periadnexal soft tissue, liver [high power], and renal hilar adipose tissue; 1 mm for liver [low power] and kidney). H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/8/7/10.1182_bloodadvances.2023012529/2/m_blooda_adv-2023-012529-gr5.jpeg?Expires=1769127817&Signature=OpZFLJvxwRMUZbXcLTVeW0f5Hn78kUAIHRtvrfqLe95lPudH6wWQqySHlUM12hsSEk6qm9KtzXaJv8quHwKkXdZaxAzvYbhLjOnIyLdPUsfco9QA-Uiep4nTYOn~nkvKw~tTpNkjlewxogZsTIfrkLNbMjxOWd75GoXlLticqbZFIwendooDAbNAAR1nVEo029SLCxzng2clH-aEU17VzbaULX8lKoEq65W-D07rbU~-7fvxD9liHk~irxr05Oe7vO3IaY-dXoCoOT2VcBkCLlo8Sb9cwBelNIaBysjMGGSaPqYkeLlpr1ft902k-KZqnzazF-LiB5Sm8p~sKpTdDg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)