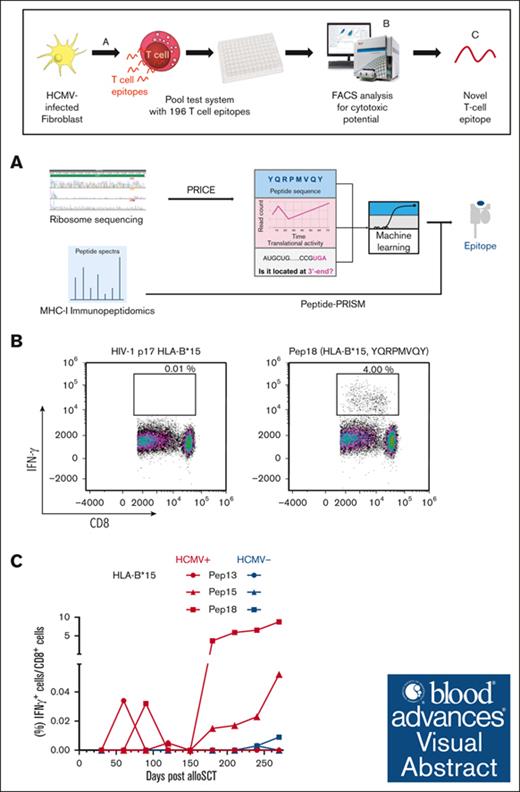

HCMV-derived peptides for HLA-A∗03:01 and HLA-B∗15:01 haplotypes were identified via Ribo-seq, mass spectrometry, and machine learning.

Six novel immunogenic peptides were identified, establishing a framework for efficient detection of peptides from Ribo-seq data sets.

Visual Abstract

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) reactivation poses a substantial risk to patients receiving tranplants. Effective risk stratification and vaccine development is hampered by a lack of HCMV-derived immunogenic peptides in patients with common HLA-A∗03:01 and HLA-B∗15:01 haplotypes. This study aimed to discover novel HCMV immunogenic peptides for these haplotypes by combining ribosome sequencing (Ribo-seq) and mass spectrometry with state-of-the-art computational tools, Peptide-PRISM and Probabilistic Inference of Codon Activities by an EM Algorithm. Furthermore, using machine learning, an algorithm was developed to predict immunogenicity based on translational activity, binding affinity, and peptide localization within small open reading frames to identify the most promising peptides for in vitro validation. Immunogenicity of these peptides was subsequently tested by analyzing peptide-specific T-cell responses of HCMV-seropositive and -seronegative healthy donors as well as patients with transplants. This resulted in the direct identification of 3 canonical and 1 cryptic HLA-A∗03–restricted immunogenic peptides as well as 5 canonical and 1 cryptic HLA-B∗15–restricted immunogenic peptide, with a specific interferon gamma–positive (IFN-γ+)/CD8+ T-cell response of ≥0.02%. High T-cell responses were detected against 2 HLA-A∗03–restricted and 3 HLA-B∗15–restricted canonical peptides with frequencies of up to 8.77% IFN-γ+/CD8+ T cells in patients after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Therefore, our comprehensive strategy establishes a framework for efficient identification of novel immunogenic peptides from both existing and novel Ribo-seq data sets.

Introduction

Reactivation of latent human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is the most common infectious complication after allogeneic stem cell transplantation (allo-SCT), resulting in high morbidity and mortality.1,2 Clinical evidence indicates that a delayed HCMV-specific T-cell response is a main risk factor of prolonged HCMV viremia and HCMV disease.3,4

Although many immunodominant HCMV-derived antigens, such as immediate-early protein 1 (IE1) and phosphoprotein 65 (pp65) have been described, it has become apparent that the HCMV-specific T-cell response relies on a much broader HCMV antigen spectrum.5-12 A broad anti-HCMV T-cell response is most likely a necessity for the immune system to control HCMV infection.13 Risk stratification via the detection of HCMV-specific T cells and re-establishment of the anti-HCMV T-cell response have been shown to reduce HCMV-associated morbidity and mortality.14,15 These approaches are reliant on immunogenic peptides. Only few HCMV-derived peptides are available for the common HLA haplotypes HLA-A∗03:01 and HLA-B∗15:01. Thus, to improve HCMV vaccine development and personalized risk stratification via immune monitoring, additional HCMV-derived peptides need to be identified.

Previous studies have used various methods, including prediction algorithms16 and overlapping peptide pools,17,18 to identify HCMV antigens. Although ribosome sequencing (Ribo-seq) has been widely used to discover novel immunogenic peptides, its utility has been constrained by the inability to detect cryptic peptides and the presence of a high noise-to-signal ratio, leading to the loss of potentially valuable candidates.19 Recently, we have made significant advancements in Ribo-seq by applying Probabilistic Inference of Codon Activities by an EM Algorithm (PRICE) to process Ribo-seq data. This improved methodology enabled us to identify and quantify the translation of novel small open reading frames (ORFs) encoded by HCMV.19 Furthermore, our analyses of a large panel of mass spectrometry (MS) data of peptides bound by HLA-I using our Peptide-PRISM method revealed widespread HLA-I presentation of cryptic peptides. These are translated from ORFs outside of the annotated proteome and encoded in 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions, noncoding RNAs, and intronic and intergenic regions and within coding sequences shifted with respect to the conventional (canonical) reading frame.20 Although cryptic peptides tend to be short-lived and are mostly unidentifiable with conventional computational analyses of MS data, they can be used as a source for HLA-I peptides.20

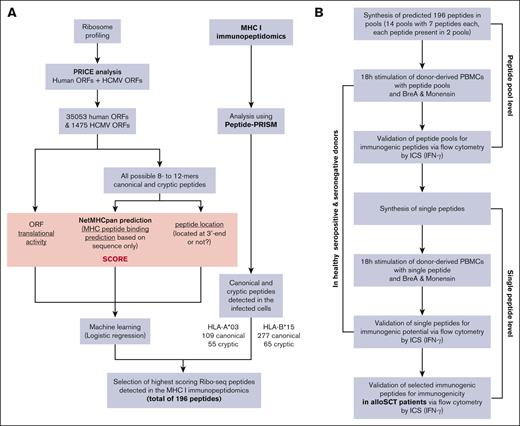

In this study, we implemented Peptide-PRISM and PRICE to analyze data sets from MS and Ribo-seq experiments. Our objective was to identify HLA-I–bound peptides in the HCMV-infected human fibroblast (HF) cell lines HF-99/713 and HF-γ. To improve the strategy of evidence-driven candidate selection for immunogenicity testing, we expanded our analysis to include cryptic peptides. Focusing on HLA-A∗03 and HLA-B∗15 haplotypes, we developed a machine learning algorithm that ranked all HCMV-encoded cryptic and canonical peptides identified by MS based on translational activity, positioning, and binding affinity. By implementing this ranking system, we were able to selectively choose the most promising candidate peptides for in vitro validation of their immunogenicity.

A subsequent pool test strategy allowed for us to identify these peptide candidates for validation at single peptide level in both healthy donors and allo-SCT recipients. Thus, we present a comprehensive approach that combines in silico and in vitro methods to identify new HLA-I–restricted, HCMV-derived peptides and efficiently assess their immunogenicity. This approach has led to the discovery of novel HCMV-derived immunogenic peptides, which hold potential for vaccine development, immunomonitoring, and immunotherapy applications.

Methods

Data sets for analysis

We analyzed previously published MS data of the HCMV-infected human foreskin fibroblast cell lines using Peptide-PRISM version 1.1.0.20 Briefly, Peptide-PRISM uses de novo peptide sequencing to identify 10 candidate sequences per mass spectrum, which were then screened against the whole human and viral genome and transcriptome. Peptides were classified as either conventional or cryptic as described, and the group-specific false discovery rates were estimated using a mixture model approach. netMHCpan 4.1 was then used to compute binding affinities for all 6 HLA alleles expressed in the respective cells, and the top-scoring allele was assigned to each peptide. For the identification of HCMV-derived HLA-A∗03 ligands, HF-99/7 cells were used for infection as described previously.13 For identification of further HCMV-derived HLA-A∗03 and HLA-B∗15:01 ligands, HF-γ cells (a kind gift of Dieter Neumann-Haefelin and Valeria Kapper-Falcone, University Medical Center Freiburg) were used for infection. With a multiplicity of infection of 10, the cells were infected with an AD169VarL strain–derived bacterial artificial chromosome-based HCMV mutant virus lacking the genes US2-US6 and US11 for 48 hours before harvesting of cells and determination of HLA-I ligandomes, as described previously.21 These data sets were generated on a high-resolution mass spectrometer (Orbitrap Lumos), which is required for the de novo peptides sequencing analysis. Results were filtered for a category-specific 10% false discovery rate by Peptide-PRISM. We used the HCMV, host ORF, and their total translational activities derived from Ribo-seq data of HCMV infected fibroblasts from the article by Erhard et al.19

Machine learning for the prediction of HLA-I presented peptides

We first generated all 8- to 10-oligomer peptide sequences from all translated ORFs (HCMV and human; as defined by the Ribo-seq data) and used netMHCpan 4.1 to predict HLA-I binding to HLA-A∗03 and HLA-B∗15 for all these peptides. Each peptide was classified as either canonical or cryptic based on their sequences being part of the human proteome (Ensembl version 90) or HCMV proteome (KF297339.1, NC_006273, EF999921, or MF871618). We further annotated all peptides by their translational activity from Ribo-seq and also flagged them as N-terminal or not (0 or 1) according to the Ribo-seq ORF. We then trained logistic regression models separately for canonical HLA-A∗03, cryptic HLA-A∗03, canonical HLA-B∗15, and cryptic HLA-B∗15. The independent variables were the netMHCpan score, translational activity, and the binary flag indicating an N-terminal peptide. The dependent variable was the presence of the peptide among the HLA-I immunopeptidome MS data. These regression models were used to rank all viral peptides and again separately for the 2 haplotypes and canonical/cryptic. For the final selection of the candidates for immunogenicity testing, all peptides not detected by MS were removed, and the top 49 scoring peptides were selected within each of the 4 groups (HLA-A∗03/HLA-B∗15 and canonical/ cryptic; Figure 1A).

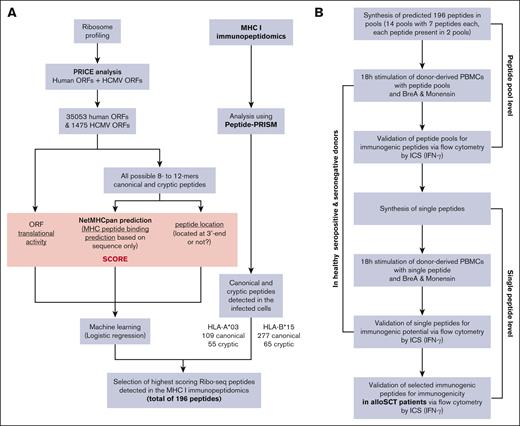

Workflow of the complete strategy for the identification of novel immunogenic peptides. (A) Bioinformatic workflow for the in silico prediction of HCMV-derived peptides. (B) Workflow of the in vitro validation strategy of the in silico HCMV-derived peptide predictions. BreA, Brefeldin A; ICS, intracellular cytokine staining;

Workflow of the complete strategy for the identification of novel immunogenic peptides. (A) Bioinformatic workflow for the in silico prediction of HCMV-derived peptides. (B) Workflow of the in vitro validation strategy of the in silico HCMV-derived peptide predictions. BreA, Brefeldin A; ICS, intracellular cytokine staining;

Institutional review board approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of the University of Wuerzburg (protocol code 17/19-sc) and Hannover Medical School (ethical numbers 3639-2017 and 2744-2015).

Study population

According to standard donation requirements,22 40 healthy donors with HCMV-seropositive and 27 HCMV-seronegative HLA type were included at the Hannover Medical School Institute of Transfusion Medicine and Transplant Engineering between June 2020 and April 2022. Residual blood samples from platelet apheresis disposable kits used for routine platelet collection from these healthy donors were used. All donors were pretested for HCMV serostatus as described previously using commercially available immunoglobulin G (IgG) western blot.23 Eighteen allo-SCT recipients with HCMV seropositivity and 12 with HCMV seronegativity (females, 36.7%; males, 63.3%) were included in a cohort at the University Hospital of Wuerzburg between August 2019 and April 2022 after informed written consent was obtained. HLA typing was performed for all participants at the Institute of Transfusion Medicine and Hemotherapy, University Hospital of Wuerzburg (supplemental Table 1). The study exclusively included samples of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) obtained from donors with the haplotypes HLA-A∗03 and/or HLA-B∗15. HCMV seropositivity/negativity in all patients was routinely confirmed by IgG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and western blot23,24 at the Institute of Virology, University of Wuerzburg.

Blood collection, cryopreservation, and thawing process

Whole blood (40 mL) was drawn into monovette blood collection system tubes (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany) containing EDTA (allo-SCT recipients), or buffy coats were obtained during apheresis (healthy volunteers). PBMCs were isolated via a density gradient (histopaque, 1.077 g/mL; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Cells were counted using a Neubauer improved counting chamber (Laboroptik, Lancing, United Kingdom) and cryopreserved at a concentration of up to 1.0 × 107 PBMCs per mL. Cryopreservation medium consisted of 40% RPMI 1640 medium glutamax (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), 50% fetal calf serum (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich). After initial storage at −80°C, PBMCs were transferred to liquid nitrogen for long-term storage.

For thawing, immune cell medium (ICM), consisting of RPMI glutamax + 10% fetal calf serum + 50 μg/mL gentamycin (Gibco), was prewarmed. Cryopreserved PBMCs were incubated in prewarmed ICM. Thereafter, the cells were washed with 10 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (Gibco) and resuspended in 20 mL of ICM. PBMCs were allowed to rest for 3 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2, passed through a 70 μm cell strainer (EASYstrainer, Greiner, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), and resuspended in ICM at a concentration of 5 × 106 cells per mL.

Design of peptide pools and reconstitution of single peptides

By applying a crossing scheme, 49 peptides per haplotype were spread across 14 pools (7 peptides per pool [peptide & elephants, Hennigsdorf, Germany], with purity of at least 70%). Each peptide was included in 2 different pools. Lyophilized peptide pools and single peptides were dissolved in 100% DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich), diluted with water (Aqua ad iniectabilia, Deltamedica, Reutlingen, Germany) to a final concentration of 2 mg/mL (in 10% DMSO), and stored at −80°C.

PBMC stimulation and staining

Two hundred microliters of ICM containing 1 × 106 PBMCs were seeded in each well of a 96-well round bottom plate (Falcon, Corning Incorporated-Life Sciences, Durham, NC) and incubated for 2 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. PBMCs were stimulated with either peptide pools (7 μg/μL and 35 μg/μL), single peptides (1 μg/μL), 0.1 μg/mL of a pp65 peptide mix (PepMix HCMVA pp65, >90% purity, JPT Peptide Technologies, Berlin, Germany), the appropriate HIV background control (HIV_Gag [HLA-A∗03] RLRPGGKKK and HIV-1 p17 [HLA-B∗15] RLRPGGKKKY), or 0.1 μg/mL of an HIV peptide mix (PepMix HIV 1 NEF, Ultra, JPT) at 37°C and 5% CO2. In certain experiments, pp65 peptides were presented on the donors' alternative HLA allotype (pp65 peptide sequences; HLA-A∗01: YSEHPTFTSQY, HLA-A∗02: NLVPMVATV, HLA-A∗11: ATVQGQNLK, HLA-A∗24: QYDPVAALF and HLA-B∗07: TPRVTGGGAM, HLA-B∗08: ELRRKMMYM, and HLA-B∗35: IPSINVHHY) via the same stimulation protocol. Wells for negative and positive controls remained unstimulated. Brefeldin A (10 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) and GolgiStop (1.2 μL per well; 0.67 μL/mL; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) were added to all wells after 1 hour of incubation. The previously unstimulated wells used for the positive control were stimulated with PMA (0.5 μg/mL) and ionomycin (1 μg/mL; both Sigma-Aldrich). PBMCs were incubated for another 18 hours before being stained as described previously,25 with the only difference being that staining was performed in a 96-well round bottom plate instead of 4 mL round-bottom polystyrene tubes. Ethidium monoazide (0.5 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) was used as a live-dead stain; α-CD3-AF700 (1 μL per well; Becton Dickinson, 557943), α-CD4-V500 (1 μL per well; Becton Dickinson, 560768), and α-CD8-V450 (2 μL per well; Becton Dickinson, 560347) were used for extracellular staining; and α-interferon gamma (IFN-γ)–fluorescein isothiocyanate (5 μL per well; Beckman Coulter, IM2716U) was used for intracellular staining (Figure 1B).

Flow cytometry

Stained PBMCs were acquired using a CytoFLEX cytometer (AS34240) with CytExpert version 2.4 software (both from Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). Kaluza version 2.1 (Beckman Coulter) was used for data analysis. The gating strategy is shown in supplemental Figure 1.

Statistical analysis

Subtracting HIV peptide–induced frequencies (considered negative control in individuals negative for HIV) from HCMV peptide–induced frequencies resulted in background-corrected, HCMV peptide–specific T-cell frequencies. Statistical significance was tested using the Mann-Whitney U test. When applicable, the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure was used to test for a false-positive discovery rate of <0.2%. Data were compiled, analyzed, and visualized using GraphPad Prism version 9.4 (Boston, MA).

Data availability

Results

Bioinformatic identification of HLA-I peptides

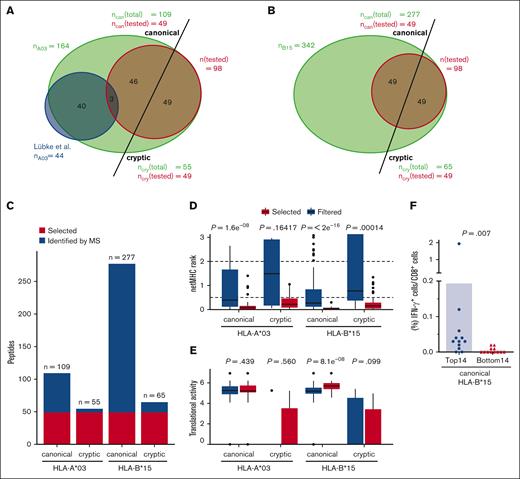

Using MS analysis of peptides obtained from purified HLA-I complexes, we effectively identified an extensive repertoire of HLA-I presented peptides derived from 2 HCMV-infected HF cell lines. The Ribo-Seq database for HF-γ cells for HLA-A∗03 and HLA-B∗15 were generated and analyzed. Additionally, a previously published dataset for HF-99/7 cells was reanalyzed for novel immunogenic peptides.13 In total, we discovered 164 HLA-A∗03–restricted and 342 HLA-B∗15–restricted HCMV-derived peptide sequences from both data sets (supplemental Table 2). Among the HCMV-derived peptides we identified, a subset of 40 peptides were previously published alongside the original data set that underwent reanalysis. However, these 40 peptides represented only 37% of the HLA-A∗03–restricted, canonical peptides (n =109) and 8% of the total identified peptides (n = 506; Figure 2A,B). In addition to 109 canonical peptides restricted to HLA-A∗03 and 277 canonical peptides restricted to HLA-B∗15, we identified 55 cryptic peptides for HLA-A∗03 and 65 cryptic peptides for HLA-B∗15. Our peptide pool testing strategy required the selection of 49 candidates from each category (canonical HLA-A∗03:01, canonical HLA-B∗15:01, cryptic HLA-A∗03:01, and cryptic HLA-B∗15:01; Figure 2C). Thus, we included additional data to filter viral peptides for bona fide HLA-I binders. We used machine learning to integrate data on translational activity of the ORF encoding each peptide, HLA-I binding affinity prediction, and positional information of the peptide within its ORF into a single score that we used to rank peptides and selected the top 49 candidates. The most important feature was the netMHCpan score for both alleles, followed by the translational activity and the positional information (supplemental Figure 2). The predicted binding affinity for selected peptides was significantly better than for filtered sequences (Figure 2D), and ORFs encoding selected peptides were more strongly translated at least for canonical HLA-B∗15:01–restricted peptides (Figure 2E). This indicates that indeed both criteria were used to rank peptides. We further validated the algorithm by performing in vitro stimulation of PBMCs from 12 healthy donors with HLA-A∗03+ and 12 with HLA-B∗15+ HCMV seropositivity. We reasoned that if the model accurately predicts peptide immunogenicity, the pooled top-ranked peptides would induce a more pronounced pool-specific T-cell response than lower-ranked pooled peptides. We compared the pool-specific T-cell frequencies of the top-ranked peptides (ranks 1-14) with those of the lower-ranked peptides (ranks 36-49) to identify differences in their immunogenicity. The reactivity of the peptide pools was too sporadic in the tested HLA-A∗03+ donors for any definitive conclusions. However, in HLA-B∗15+ healthy donors, the top 14 peptides significantly triggered higher pool-specific T-cell frequencies than the bottom 14 peptides (mean, 0.19 vs 0.01 IFN-γ+/CD8+ T-cell frequencies; P = .007), as shown in Figure 2F. We did not test cryptic peptides for algorithm validation because of their anticipated low reactivity.

Bioinformatic identification of HLA-I peptides. (A,B) The distribution of identified canonical and cryptic peptide sequences restricted by HLA-A∗03 (A) and HLA-B∗15 (B) including an overlap of HLA-A∗03 restricted, canonical peptides published in the report by Lübke et al,13 which relies on 1 of the data sets examined in our study (A). (C) Identified and selected canonical and cryptic peptides for the haplotypes HLA-A∗03:01 and HLA-B∗15:01. (D,E) Box plot showing the distributions of netMHC ranks and translational activity measured by Ribo-seq of all peptides selected for testing (selected) and all other peptides identified by MHC-I immunopeptidomics (filtered). (D) The default cutoffs for strong binders (cutoff = 0.5) and binders (cutoff = 2) of the netMHC score are indicated. (F) Validation of immunogenicity of the top ranked 14 peptides vs the bottom ranked 14 peptides used for pool testing. Background-corrected peptide-specific T-cell frequencies of PBMCs from healthy donors with HCMV-seropositive HLA-B∗15+ stimulated with peptide pools A, B, F, and G (as described in Figure 3C, HLA-B∗15 canonical) are shown. Each symbol represents 1 donor. Mann-Whitney U test was used for statistical analysis (∗∗P < .01). can, canonical; cry, cryptic.

Bioinformatic identification of HLA-I peptides. (A,B) The distribution of identified canonical and cryptic peptide sequences restricted by HLA-A∗03 (A) and HLA-B∗15 (B) including an overlap of HLA-A∗03 restricted, canonical peptides published in the report by Lübke et al,13 which relies on 1 of the data sets examined in our study (A). (C) Identified and selected canonical and cryptic peptides for the haplotypes HLA-A∗03:01 and HLA-B∗15:01. (D,E) Box plot showing the distributions of netMHC ranks and translational activity measured by Ribo-seq of all peptides selected for testing (selected) and all other peptides identified by MHC-I immunopeptidomics (filtered). (D) The default cutoffs for strong binders (cutoff = 0.5) and binders (cutoff = 2) of the netMHC score are indicated. (F) Validation of immunogenicity of the top ranked 14 peptides vs the bottom ranked 14 peptides used for pool testing. Background-corrected peptide-specific T-cell frequencies of PBMCs from healthy donors with HCMV-seropositive HLA-B∗15+ stimulated with peptide pools A, B, F, and G (as described in Figure 3C, HLA-B∗15 canonical) are shown. Each symbol represents 1 donor. Mann-Whitney U test was used for statistical analysis (∗∗P < .01). can, canonical; cry, cryptic.

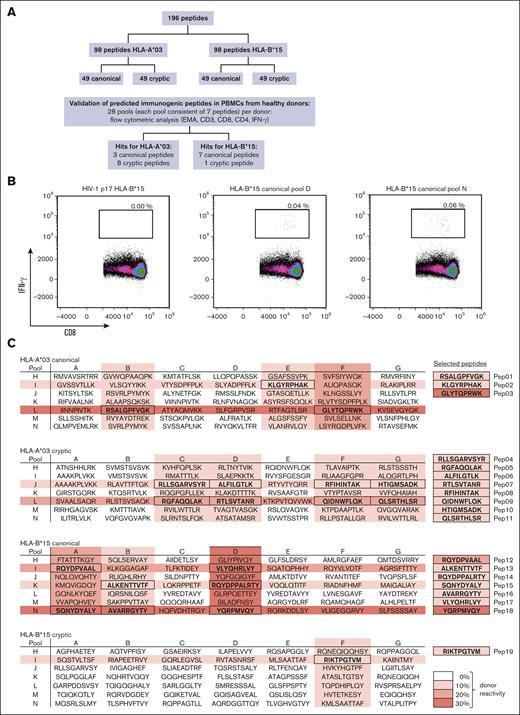

Peptide pool testing of in silico identified T-cell epitopes reveals potentially immunogenic HCMV-derived peptides

In silico analysis identified 98 HLA-A∗03 (49 canonical and 49 cryptic) and 98 HLA-B∗15 (49 canonical and 49 cryptic) potentially immunogenic HCMV-derived peptides (Figure 3A) for in vitro validation. Stimulation of PBMCs with each single peptide was not feasible because of the number of identified peptides. Therefore, we used a pool testing strategy. For both HLA-A∗03 and HLA-B∗15, each peptide was included in 2 peptide pools with a total of 7 peptides, resulting in a total of 14 pools per haplotype. Peptide pools were considered immunogenic when PBMC stimulation led to background-corrected IFN-γ+/CD8+ T-cell frequencies of at least 0.02% in both pools. Representative density plots of peptide pool- or HIV peptide-stimulated PBMCs are shown in Figure 3B. Stimulation of PBMCs with HIV-derived peptides (considered as background control in individual negative for HIV) led to negligible background frequencies (median, 0.00%). Background-corrected pool-specific T-cell frequencies induced by the reactive peptide pools ranged from 0.02% to 0.06% (range, HLA-A∗03 canonical, 0.02%-0.05%; cryptic, 0.03%-0.04%; and HLA-B∗15 canonical, 0.02%-0.06%; cryptic, 0.04%; Figure 3C). Canonical peptide pools induced specific T-cell responses more frequently in HCMV-seropositive donors than cryptic peptide pools. Three canonical peptides for HLA-A∗03 showed pool-specific T-cell frequencies of at least 0.02% in 30% of the healthy donors and 7 canonical peptides for HLA-B∗15 in 40% of the donors. Cryptic peptides (8 HLA-A∗03 and 1 HLA-B∗15) were only detectable in 10% of the donors for each haplotype. In summary, peptide pool testing reduced the number of potentially immunogenic peptides from 196 to 19 (Figure 3C; supplemental Table 3). Eleven of the identified peptides were HLA-A∗03-restricted (3 canonical and 8 cryptic) and 8 HLA-B∗15-restricted (7 canonical and 1 cryptic).

Identification of novel epitopes using peptide pools. (A) Workflow used to identify novel immunogenic peptide candidates. (B) Representative flow cytometric density plot analyzing IFN-γ+/CD8+ T-cell frequencies after stimulation with canonical peptide pools D and N as well as a negative background control (HIV-1 p17 HLA-B∗15). (C) Overview of peptide pools A-N (consisting of 7 peptides each). Each single peptide was present in 2 pools (A-G and H-N). Peptide sequences are highlighted if both peptide pools containing a peptide elicited IFN-γ+/CD8+ T-cell frequencies of ≥0.02%. Color density (0%-30% donor reactivity) indicates the percentage of healthy donors with a cytotoxic T-cell response induced by a certain peptide pool (IFN-γ+/CD8+ T-cell frequencies of ≥ 0.02%). EMA, ethidium monoazide.

Identification of novel epitopes using peptide pools. (A) Workflow used to identify novel immunogenic peptide candidates. (B) Representative flow cytometric density plot analyzing IFN-γ+/CD8+ T-cell frequencies after stimulation with canonical peptide pools D and N as well as a negative background control (HIV-1 p17 HLA-B∗15). (C) Overview of peptide pools A-N (consisting of 7 peptides each). Each single peptide was present in 2 pools (A-G and H-N). Peptide sequences are highlighted if both peptide pools containing a peptide elicited IFN-γ+/CD8+ T-cell frequencies of ≥0.02%. Color density (0%-30% donor reactivity) indicates the percentage of healthy donors with a cytotoxic T-cell response induced by a certain peptide pool (IFN-γ+/CD8+ T-cell frequencies of ≥ 0.02%). EMA, ethidium monoazide.

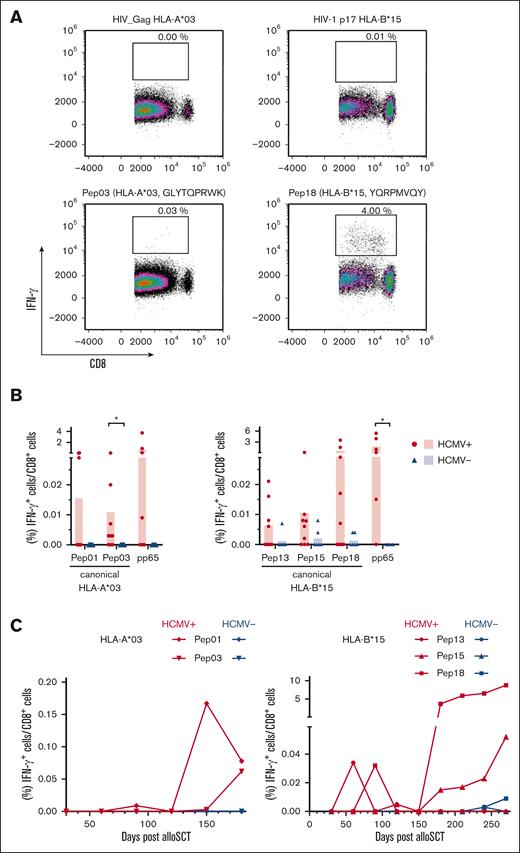

Single peptide testing confirmed potentially immunogenic peptides

To further validate the immunogenicity of the peptides discovered by pool testing, PBMCs from healthy donors with HCMV seropositivity were stimulated with single peptides (supplemental Table 3). Stimulation of PBMCs from healthy donors with HCMV seronegativity was used to evaluate the specificity of these peptides. A single peptide was considered immunogenic when PBMC stimulation led to background-corrected IFN-γ+/CD8+ T-cell frequencies of at least 0.02%. Given the scarcity of HCMV-derived HLA-A∗03 and HLA-B∗15 antigens, we quantified T-cell frequencies specific to pp65 presented by the donors' alternative HLA allotype for comparative analysis. Representative density plots of single peptide– or HIV peptide–stimulated PBMCs from donors with HCMV seropositivity are shown in Figure 4A. Two HLA-A∗03–restricted peptides triggered significantly higher peptide-specific T-cell frequencies in donors with HCMV seropositivity than in those with HCMV seronegativity: the canonical peptide HLA-A∗03 Pep03 (P = .001) and the cryptic peptide HLA-A∗03 Pep11 (P = .040). In addition, 6 HLA-B∗15-restricted peptides elicited significantly higher peptide-specific T-cell frequencies in donors with HCMV seropositivity than in those with HCMV seronegativity: canonical HLA-B∗15 Pep12 (P = .020), HLA-B∗15 Pep13 (P = .010), HLA-B∗15 Pep15 (P = .009), HLA-B∗15 Pep17 (P = .008), HLA-B∗15 Pep18 (P = .004), and cryptic HLA-B∗15 Pep19 (P = .001; Figure 4B). The frequency of peptide-reactive donors ranged from 5% to 26%. Donor reactivity was found after stimulation with the canonical peptides HLA-A∗03 Pep01 (10%), HLA-A∗03 Pep02 (10%), and HLA-A∗03 Pep03 (10%) and HLA-B∗15 Pep12 (11%), HLA-B∗15 Pep13 (16%), HLA-B∗15 Pep 17 (11%), and HLA-B∗15 Pep18 (26%) as well as the cryptic peptide HLA-A∗03 Pep11 (10%; supplemental Table 3). Peptides for which the analysis revealed P <.05 and a log2-transformed mean-to-mean ratio of at least 1.5 (Figure 4C) as well as a donor reactivity of at least 10% (supplemental Table 3, response in donors, single peptide) were chosen for subsequent evaluation among the patient samples after allo-SCT.

Confirmation of identified immunogenic epitopes at the single peptide level. (A-B) PBMCs from healthy donors were stimulated with HCMV-derived single peptides. Peptide-specific T-cell frequencies (IFN-γ+/CD8+) were quantified by flow cytometry. (A) Representative flow cytometric density plots of IFN-γ+/CD8+ T-cell frequencies after stimulation with a background control (HIV_Gag HLA-A∗03 or HIV-1 p17 HLA-B∗15) or HCMV-derived peptides are shown. (B) Background-corrected peptide-specific T-cell frequencies of PBMCs from healthy donors with HCMV seropositivity (red circles) or seronegativity (blue triangles). PBMCs were also stimulated with pp65 peptides that were presented on the donors' alternative HLA allotype for comparative analysis. Each symbol represents 1 donor. The Mann-Whitney U test and Benjamini-Hochberg procedure for a false-positive discovery rate of <0.2 were used for statistical analysis (∗ P < .05; ∗∗ P < .01; ∗∗∗ P < .001). (C) Volcano plot showing the P value (Mann-Whitney U test) and respective log2-transformed mean-to-mean ratios between healthy donors with HCMV seropositivity and HCMV seronegativity from Figure 4B. Peptides were classified into nonimmunogenic (●; log2-transformed mean-to-mean ratio < 1.5; P > .05) or immunogenic (▲; log2-transformed mean-to-mean ratio > 1.5; P < .05) peptides.

Confirmation of identified immunogenic epitopes at the single peptide level. (A-B) PBMCs from healthy donors were stimulated with HCMV-derived single peptides. Peptide-specific T-cell frequencies (IFN-γ+/CD8+) were quantified by flow cytometry. (A) Representative flow cytometric density plots of IFN-γ+/CD8+ T-cell frequencies after stimulation with a background control (HIV_Gag HLA-A∗03 or HIV-1 p17 HLA-B∗15) or HCMV-derived peptides are shown. (B) Background-corrected peptide-specific T-cell frequencies of PBMCs from healthy donors with HCMV seropositivity (red circles) or seronegativity (blue triangles). PBMCs were also stimulated with pp65 peptides that were presented on the donors' alternative HLA allotype for comparative analysis. Each symbol represents 1 donor. The Mann-Whitney U test and Benjamini-Hochberg procedure for a false-positive discovery rate of <0.2 were used for statistical analysis (∗ P < .05; ∗∗ P < .01; ∗∗∗ P < .001). (C) Volcano plot showing the P value (Mann-Whitney U test) and respective log2-transformed mean-to-mean ratios between healthy donors with HCMV seropositivity and HCMV seronegativity from Figure 4B. Peptides were classified into nonimmunogenic (●; log2-transformed mean-to-mean ratio < 1.5; P > .05) or immunogenic (▲; log2-transformed mean-to-mean ratio > 1.5; P < .05) peptides.

As a result, 10 of 19 peptides (52.6%) identified during pool testing could be confirmed in single peptide testing.

The identified peptides are not extensively presented on other HLA alleles

To determine whether the identified peptides were predominantly expressed on HLA-A∗03 or HLA-B∗15, we stimulated PBMCs from healthy donors with HLA-A∗03- and HLA-B∗15- negative HCMV seropositivity using the 6 novel peptides. Notably, although a HCMV peptide mix, comprising peptides for a wide range of allotypes, predictably led to high peptide mix–specific CD8+ frequencies, none of our new peptides triggered a peptide-specific response in these donors (supplemental Figure 3).

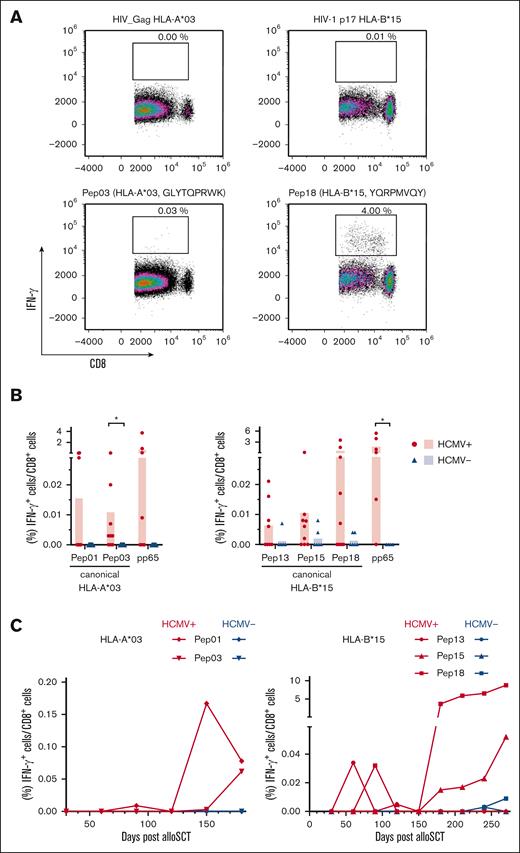

Peptides induce specific T-cell frequencies in patient samples

To assess the clinical relevance, we analyzed peptide-specific T-cell responses in patients with HCMV seropositivity after allo-SCT (supplemental Table 1). Representative density plots of single peptide– or HIV peptide–stimulated PBMCs from allo-SCT recipients with HCMV seropositivity are shown in Figure 5A. On average, HCMV reactivation can be detected at day +171 in allo-SCT recipients with HCMV seropositivity after discontinuation of letermovir prophylaxis.25 Therefore, we analyzed PBMCs from patients on day +180 after allo-SCT during HCMV-specific T-cell proliferation to increase the probability of detecting cytotoxic T-cell responses against the identified peptides.

Verification of the immunogenicity of the identified HCMV-derived peptides in PBMCs from patients after allo-SCT. (A) Representative flow cytometric density plots of IFN-γ+/CD8+ T-cell frequencies after stimulation with a background control (HIV_Gag HLA-A∗03 or HIV-1 p17 HLA-B∗15) or HCMV-derived single peptides are shown. (B) Background-corrected peptide-specific T-cell frequencies of PBMCs from patients with HCMV seropositivity (red circles) or seronegativity (blue triangles) 180 days after allo-SCT after stimulation with HCMV-derived single peptides. PBMCs were also stimulated with pp65 peptides that were presented on the donors' alternative HLA allotype for comparative analysis. Each symbol represents 1 donor. The Mann-Whitney U test and Benjamini-Hochberg procedure for a false-positive discovery rate of <0.2 were used for statistical analysis (∗ P < .05). (C) PBMCs from an allo-SCT recipients with HCMV seropositivity (red) or HCMV seronegativity (blue) were longitudinally collected every 30 days from day +30 to day +180 (HLA-A∗03) or day +270 (HLA-B∗15). PBMCs were stimulated with the specified HCMV-derived single peptides. Background-corrected IFN-γ+/CD8+ T-cell frequencies are shown. The used specific peptides can be identified by the symbols shown in Figure 5C.

Verification of the immunogenicity of the identified HCMV-derived peptides in PBMCs from patients after allo-SCT. (A) Representative flow cytometric density plots of IFN-γ+/CD8+ T-cell frequencies after stimulation with a background control (HIV_Gag HLA-A∗03 or HIV-1 p17 HLA-B∗15) or HCMV-derived single peptides are shown. (B) Background-corrected peptide-specific T-cell frequencies of PBMCs from patients with HCMV seropositivity (red circles) or seronegativity (blue triangles) 180 days after allo-SCT after stimulation with HCMV-derived single peptides. PBMCs were also stimulated with pp65 peptides that were presented on the donors' alternative HLA allotype for comparative analysis. Each symbol represents 1 donor. The Mann-Whitney U test and Benjamini-Hochberg procedure for a false-positive discovery rate of <0.2 were used for statistical analysis (∗ P < .05). (C) PBMCs from an allo-SCT recipients with HCMV seropositivity (red) or HCMV seronegativity (blue) were longitudinally collected every 30 days from day +30 to day +180 (HLA-A∗03) or day +270 (HLA-B∗15). PBMCs were stimulated with the specified HCMV-derived single peptides. Background-corrected IFN-γ+/CD8+ T-cell frequencies are shown. The used specific peptides can be identified by the symbols shown in Figure 5C.

Peptide-specific cytotoxic T-cell frequencies were found to be as high as 0.08% and 3.42% for HLA-A∗03– and HLA-B∗15–restricted peptides, respectively. Canonical HLA-A∗03 Pep01 elicited a frequency of 0.08% peptide-specific cytotoxic T cells in patients with HCMV seropositivity, whereas no peptide-specific T-cell responses were detected in patients with HCMV seronegativity. PBMCs stimulated with canonical HLA-A∗03 Pep03 showed significantly elevated peptide-specific T-cell frequencies in patients with HCMV seropositivity compared with those with HCMV seronegativity (P = .010). A total of 33.3% of the patients were reactive to HLA-A∗03 Pep01, and 22.2% of the patients were reactive to HLA-A∗03 Pep03. Canonical HLA-B∗15 Pep13, HLA-B∗15 Pep15, and HLA-B∗15 Pep18 also induced higher peptide-specific cytotoxic T-cell responses in patients with HCMV seropositivity than in those with HCMV seronegativity. HLA-B∗15 Pep18 induced the most marked specific T-cell response with frequencies up to 3.42%, which is comparable with T-cell frequencies specific to pp65 presented by the donors' alternative HLA allotype (up to 5.31%; P = .038). A total of 33.3%, 22.2%, and 44.4% of the patients were reactive to HLA-B∗15 Pep13, HLA-B∗15 Pep15 and HLA-B∗15 Pep18, respectively (Figure 5B).

Finally, the levels of peptide-specific cytotoxic T cells were longitudinally quantified in the respective peptide-reactive patients from day +30 to day +180 (HLA-A∗03) or day +270 (HLA-B∗15). As expected, peptide-specific cytotoxic T-cell frequencies increased around the time of HCMV reactivation in most cases. Of all HLA-A∗03-restricted peptides, HLA-A∗03 Pep01 stimulation induced the highest specific cytotoxic T-cell frequencies in a patient with HCMV seropositivity with specific T-cell frequencies of 0.17% at day +150. In HLA-B∗15 allo-SCT recipients, stimulation with HLA-B∗15 Pep18 resulted in the highest specific cytotoxic T-cell frequencies. Frequencies increased from 0.00% on day +150 to 3.64% on day +180 and 8.77% on day +280. HLA-B∗15 Pep13– and HLA-B∗15 Pep18–specific cytotoxic T cells were detectable as early as day +60 and day +90, respectively. Peptide-specific cytotoxic T-cell frequencies in patients with HCMV seronegativity were not detectable or were very low (0.00%-0.01%; mean, 0.00%), indicating high specificity of the identified peptides (Figure 5C).

Thus, 5 of 10 peptides (50%) identified during single peptide testing also induced reactivity in allo-SCT recipients.

Discussion

Most prior in silico approaches to identify HLA-I immunogenic peptide candidates relied on affinity prediction alone.16-18 However, peptides undergo cleavage by the proteasome, are transported into the endoplasmic reticulum, and are trimmed by peptidases. All these steps are much harder to predict than HLA-I binding affinity but are also important factors in determining whether peptides are presented. Therefore, MS approaches to experimentally determine HLA-I binding peptides have become very popular. The main limitation of MS approaches is the production of false positives and false negatives. High-quality mass spectra are only obtained for a subset of the peptides that enter the mass spectrometer. Lower-quality mass spectra frequently give rise to false peptide sequence identification, resulting in a sensitivity-specificity trade-off for data analysis. We reasoned that filtering more strictly based on the MS identification score could increase the likelihood of a correct identification. However, this approach would also exclude potentially interesting peptides. To overcome this limitation, we took a more comprehensive approach for selecting peptides for immunogenicity testing. In addition to MS data, we considered translational activity, positional information, and binding affinity prediction and used machine learning to combine these features into a single score. By integrating these various pieces of data, we aimed to improve the accuracy and specificity of our peptide selection. The score has been computed not to rely on predicted binding affinity only. For in vitro validation, enzyme linked immuno spot assay, FLUOROSPOT, and flow cytometry are commonly used for the quantification of IFN-γ+ cells after stimulation.27-30 We performed flow cytometry analysis to assess HCMV-specific T-cell responses to specifically quantify CD8+ cytotoxic T cells. Our approach allowed us to robustly detect peptide-specific T-cell frequencies as low as 0.02% because of high fluorescence intensity changes associated with positive events and extremely low background frequencies (median, 0.00%).

To assess the novelty of our findings, we searched for our identified peptides in the Immune Epitope Database as a source of defined epitopes.31 Six of the 10 identified peptides displayed no results and were therefore considered novel HCMV-derived immunogenic peptides. As expected, only the 2 cryptic peptides of the 6 novel HCMV-derived peptides could not be identified using the UniProt database (Table 1). The 4 novel HCMV-derived canonical peptides were derived from DNA polymerase processivity factor (UL44), phosphoprotein 85 (UL25), major DNA-binding protein (UL57), and viral inhibitor of caspase-8-induced apoptosis (UL36) (Table 1). The majority of the identified peptides (80%) validated in healthy donors were canonical, only a couple were cryptic, and only 1 of the cryptic peptides elicited a cytotoxic T-cell response in 1 allo-SCT recipient. Potential explanations for the low reactivity to major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I)–restricted cryptic peptides are that (1) they are not a primary target of the HCMV-specific cytotoxic T-cell response; (2) only a few individuals are responsive to these peptides, and a larger cohort is needed to identify immunogenic cryptic peptides; (3) crosspresentation and priming cannot occur efficiently because of the instability of microproteins; (4) HLA-A∗03– and HLA-B∗15–restricted cryptic peptides do not play a major role in antigen presentation of HCMV, or individuals with other HLA restrictions present cryptic HCMV peptides more efficiently; and (5) cryptic peptides might be more relevant among MHC-II–restricted peptides.34

Fifty percent of the peptides eliciting peptide-specific T-cell responses in healthy donors also induced cytotoxic T-cell responses in allo-SCT recipients. This finding might have translational relevance. Allo-SCT recipients are immunocompromised and at high risk for prolonged and symptomatic HCMV reactivation. Immune monitoring via quantification of HCMV-specific T-cell responses is used to identify patients at high risk for future prolonged and symptomatic HCMV reactivation. This allows for personalized and targeted treatment of this high-risk group,35,36 decreasing morbidity and mortality among allo-SCT recipients.37,38 A lack of available peptides results in incorrect high-risk classifications of allo-SCT recipients, especially among patients with rare HLA haplotypes.39-41 The novel HLA-A∗03- and HLA-B∗15–restricted peptides might help minimize this gap and improve patient care.

Another promising approach to decrease HCMV-associated morbidity and mortality is the development of an HCMV vaccine, which is still not available and remains an important medical need.42 Vaccination for allo-SCT recipients who are immunocompromised with live-attenuated or recombinant live viral vaccines is not recommended, and other vaccination strategies, such as chimeric peptide vaccines and peptide vaccines, rely on the identification of peptides.42 Therefore, our novel peptides also support HCMV vaccine development. Other fields of application for these peptides include peptide-loaded MHC multimers for the detection and isolation of HCMV-specific cytotoxic T cells, basic research, and the generation of highly specific peptide antibodies.43,44

Use of peptides instead of proteins has major advantages for these applications. In general, peptides are more specific with a decreased risk for cross-reactivity because they target a specific epitope of a protein.45 Unlike most native proteins, their use is simplified by increased stability and solubility as well as a straightforward and inexpensive manufacturing process.46 However, peptide HLA restrictions limit the number of patients who can benefit from these applications.47

This study has some limitations. First, predictive inaccuracies can arise when netMHCpan is used to estimate peptide binding to HLA class I alleles from MS data because the tool does not guarantee absolute precision. To enhance the reliability of the results, future studies could use monoallelic cell lines that express only a single variant of HLA-I. This approach would reduce the complexity of interpreting MS data because the binding events can be attributed to the specific HLA-I allele expressed by the cell line. Second, it cannot be excluded that the immunogenicity of some peptides has been missed due to the low numbers of responsive donors. Third, our readout was limited to intracellular stained IFN-γ. Even though this is an informative readout, it does not prove IFN-γ secretion in contrast to other methods such as enzyme-linked immuno spot assay, FLUOROSPOT and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

In conclusion, we have identified 6 novel, immunogenic, HCMV-derived peptides for individuals with HLA-A∗03 and HLA-B∗15 haplotypes, establishing a framework for efficient identification of new immunogenic peptides from both existing and novel Ribo-seq data sets.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all donors from the University Hospital of Wuerzburg and the Hannover Medical School for their blood donation, as well as Sarina Lukis (Hannover Medical School) for the preparation and sending of donor blood. The authors thank Lubov Darst, Selina Grafelmann, and Anna Groβ for their major assistance in obtaining the patient samples and Oana Butto (University Hospital of Wuerzburg) for her help with the PBMC isolation.

This work was supported by a grant of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft FOR 2830 “Advanced concepts in cellular immune control of cytomegalovirus” (project number 398367752 [S.K.]; project number 398367752 [H.E.]; DO-1275/7-1 [L.D.]; ER-927/1-2 [F.E.]; SCHL-1888/8-2 [A.S.]; and project number 421451204 [B.E.-V.]). In addition, it was supported by a grant of the Interdisziplinäre Zentrum für Klinische Forschung (S.K.).

Authorship

Contribution: H.E., F.E., G.U.G., and S.K.conceived the study; S.K. performed patient enrollment and clinical documentation; I.M., F.E., and B.K.P. performed in silico analyses; A.F.R., C.D.L., and C.K. planned and performed the experiments; S.T.-Z. organized donor material; L.B.; A.N. and M.L. conducted infection experiments and performed HLA ligandome experiments; A.F.R., I.M., A.S., and F.E. analyzed data; A.F.R. visualized data; A.F.R., C.D.L., F.E., L.D., B.E.-V., H.E., and S.K. led project administration and supervision; F.E., L.D., A.S., B.E.-V., H.E., G.U.G., and S.K. acquired the funding; A.F.R., C.D.L., F.E., and S.K. wrote the original draft of the manuscript; and all authors reviewed, edited, and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Florian Erhard, Faculty for Informatics and Data Science, University of Regensburg, Bajuwarenstraße 4, 93053 Regensburg, Germany; email: florian.erhard@informatik.uni-regensburg.de; and Sabrina Kraus, Department of Internal Medicine II, University Hospital of Würzburg, Oberdürrbacherstraße 6, 97080 Würzburg, Germany; email: kraus_s3@ukw.de.

References

Author notes

∗A.F.R. and C.D.L. contributed equally to this work.

†F.E. and S.K. contributed equally to this work.

Data are available from the corresponding author, Sabrina Kraus (kraus_s3@ukw.de).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.