TO THE EDITOR:

Renal manifestations are the most common complications of sickle cell disease (SCD). Renal disease starts during childhood and progresses further in adults.1 Approximately 30% of patients with SCD develop chronic kidney disease (CKD), and 14% to 18% of them progress to end-stage kidney disease.2 Risk of CKD is 3-fold higher in patients with SCD than in the general population, yet early CKD diagnosis remains a challenge because of impaired urine concentration and glomerular hyperfiltration. In clinical practice, CKD screening methods are based on proteinuria and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) assessments. Proteinuria is often underdetected because of urine concentration defects, and eGFR calculation is complicated by increased glomerular filtration. The CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) equation overestimates glomerular filtration rate by almost 45 ml/min per 1.73 m2.3 Thus, there is an urgent need to find specific biomarkers for the early detection of CKD in patients with SCD. Recent studies identified several potential urinary biomarkers of CKD in patients with SCD, including ceruloplasmin,4 orosomucoid,5,6 and kringle domain–containing protein.7 However, all these biomarkers demonstrate only moderate sensitivity and specificity for the detection of early stages of CKD.

Soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR), a circulating form of a glycosyl phosphatidylinositol (GPI) membrane-anchored urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR), has recently emerged as a sensitive biomarker and a potential risk factor for CKD progression.8-10 Membrane-associated phospholipase C and secreted phospholipase D cleave GPI, releasing the full-length suPAR from the membrane.11,12 Both uPAR and suPAR can be cleaved by a variety of proteases, including cathepsin G, neutrophil elastase, plasmin, and urokinase-type plasmin activator (uPA) that will generate suPAR proteolytic fragments.13 suPAR fragments may induce podocyte foot effacement via activation of αvβ3 integrin leading to the development of proteinuria and kidney disease.14 A recent study that compared individuals with sickle cell trait and those without the trait, showed a strong association between elevated plasma suPAR (PsuPAR) levels and eGFR decline in carriers of the sickle cell trait.15 However, neither the mechanism of suPAR increase nor the association of suPAR levels with renal function in SCD has been investigated so far. Here, to the best of our knowledge, we have shown for the first time that circulating suPAR levels were elevated in SCD plasma. uPAR expression was increased in the activated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), collected from patients with SCD and macrophages differentiated from THP-1 cells, treated with hemoglobin S (HbS). PsuPAR levels positively correlated with stages of CKD and demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity in differentiating CKD stages 2 to 5 from stage 1 with a suPAR cutoff level of 3.75 ng/ml. The study was approved by the review board of Howard University, and all participants provided written informed consent before the sample collection.

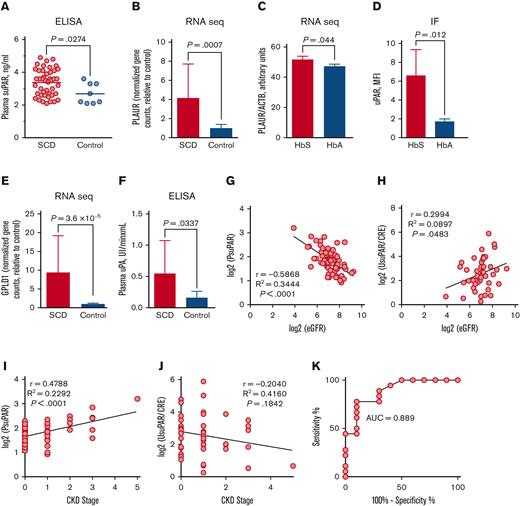

First, we measured PsuPAR levels in 44 patients with SCD without kidney disease in steady state and 8 patients without SCD as healthy control participants. We found significantly elevated PsuPAR levels in the SCD group compared with the control group (3.375 ± 0.1222 ng/ml, n = 44 for SCD vs 2.688 ± 0.2216 ng/ml, n = 8 for control participants, P = .0274; Figure 1A). No differences were found in suPAR levels between female and male patients with SCD (supplemental Figure 1). uPAR is expressed in various cells, including activated lymphocytes, monocytes, and macrophages.16,17 We hypothesize that uPAR expression is higher in SCD PBMCs. We isolated total RNA from PBMCs obtained from 6 patients with SCD and 6 age- and gender-matched healthy control paticipants and performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq; Illumina, San Diego, CA). Expression analysis of PLAUR gene that encodes uPAR, using DESeq2-generated gene counts (supplemental Figure 2A) and real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (supplemental Figure 2B), did not show a significant difference between SCD and control. Moreover, flow cytometry analysis also did not show significant differences in the percent of uPAR-positive cells and levels of uPAR expression between SCD and control PBMCs (supplemental Figure 3). Persistent inflammation, and lymphocytes and macrophage activation are common in patients with SCD.18 Nonactivated lymphocytes do not express uPAR, but activation with phytohemagglutinin or interleukin 2 (IL-2) induces uPAR expression in T lymphocytes.19 We activated PBMCs with phytohemagglutinin (0.5 μg/ml) for 48 hours followed by IL-2 (10 U/ml) for 24 hours and performed RNA-seq analysis in 9 SCD and 9 control samples. Analysis of DESeq2-generated gene counts showed significantly higher PLAUR expression levels in activated SCD PBMCs compared with activated PBMCs from healthy patients (P = .0007, n = 18; Figure 1B). Intravascular hemolysis, a common pathology of SCD, releases hemoglobin into circulation. Hemoglobin activates inflammasome in macrophages causing IL-1β production.20 IL-1β stimulates expression of uPAR in different cells including human monocytes.21 To test whether HbS increases uPAR levels in macrophages, human THP-1 monocytic cell line was differentiated into macrophages with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (25 nM, 72 hours). Macrophages were treated with either purified HbS or normal human HbA (5 μM) for 24 hours, and total RNA was isolated. RNA-seq analysis followed by DESeq2 showed a statistically significant trend toward increased PLAUR expression after HbS treatment compared with HbA treatment (P = .044; Figure 1C). Moreover, IF staining showed a significant increase in uPAR expression on THP-1–derived macrophages treated with HbS for 72 hours (P = .012; Figure 1D; supplemental Figure 4).

PsuPAR levels correlate with stages of CKD in patients with SCD. (A) PsuPAR levels for patients with SCD without CKD (n = 44) and patients without SCD as healthy control participants (n = 8). Results for each patient and means for groups are shown. (B) PLAUR expression determined by RNA-seq in activated PBMCs collected from patients with SCD (n = 9) and non-SCD healthy control participants (n = 9). (C) PLAUR expression determined by RNA-seq in THP-1–derived macrophages treated with either sickle (HbS) or healthy (HbA) human hemoglobin for 24 hours (n = 2). (D) Quantification of immunofluorescent (IF) staining of uPAR in THP-1–derived macrophages treated with mutated HbS or normal hemoglobin (HbA) for 72 hours. 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) is used for nuclear staining. Results are normalized for DAPI (n = 3). (E) GPLD1 expression determined by RNA-seq in PBMCs collected from patients with SCD (n = 6) and patients without SCD as healthy control participants (n = 6). (F) Plasma uPA activity determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays in patients with SCD (n = 13) and healthy control participants (n = 10). (G) Pearson correlation analysis of plasma log2 (PsuPAR) with log2 (eGFR) in patients with SCD (n = 77). (H) Pearson correlation analysis of urine log2 (UsuPAR/CRE) with log2 (eGFR) in patients with SCD (n = 44). (I) Pearson correlation analysis of plasma log2 (PsuPAR) with CKD stages in patients with SCD (n = 77). (J) Pearson correlation analysis of urine log2 (UsuPAR/CRE) with CKD stages in patients with SCD (n = 44). (K) Receiver operating characteristic analysis of PsuPAR shown for patients with SCD with stages 1 (n = 18) vs stages 2 to 4 (n = 10). Correlation and receiver operating characteristic were performed using GraphPad Prism 6. Results are shown as mean ± standard deviation. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. AUC, area under the curve; CRE, creatinine; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; PsuPAR, plasma suPAR; UsuPAR, urine suPAR.

PsuPAR levels correlate with stages of CKD in patients with SCD. (A) PsuPAR levels for patients with SCD without CKD (n = 44) and patients without SCD as healthy control participants (n = 8). Results for each patient and means for groups are shown. (B) PLAUR expression determined by RNA-seq in activated PBMCs collected from patients with SCD (n = 9) and non-SCD healthy control participants (n = 9). (C) PLAUR expression determined by RNA-seq in THP-1–derived macrophages treated with either sickle (HbS) or healthy (HbA) human hemoglobin for 24 hours (n = 2). (D) Quantification of immunofluorescent (IF) staining of uPAR in THP-1–derived macrophages treated with mutated HbS or normal hemoglobin (HbA) for 72 hours. 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) is used for nuclear staining. Results are normalized for DAPI (n = 3). (E) GPLD1 expression determined by RNA-seq in PBMCs collected from patients with SCD (n = 6) and patients without SCD as healthy control participants (n = 6). (F) Plasma uPA activity determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays in patients with SCD (n = 13) and healthy control participants (n = 10). (G) Pearson correlation analysis of plasma log2 (PsuPAR) with log2 (eGFR) in patients with SCD (n = 77). (H) Pearson correlation analysis of urine log2 (UsuPAR/CRE) with log2 (eGFR) in patients with SCD (n = 44). (I) Pearson correlation analysis of plasma log2 (PsuPAR) with CKD stages in patients with SCD (n = 77). (J) Pearson correlation analysis of urine log2 (UsuPAR/CRE) with CKD stages in patients with SCD (n = 44). (K) Receiver operating characteristic analysis of PsuPAR shown for patients with SCD with stages 1 (n = 18) vs stages 2 to 4 (n = 10). Correlation and receiver operating characteristic were performed using GraphPad Prism 6. Results are shown as mean ± standard deviation. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. AUC, area under the curve; CRE, creatinine; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; PsuPAR, plasma suPAR; UsuPAR, urine suPAR.

suPAR is produced by phospholipases- and proteases-mediated GPI cleavage. We analyze messenger RNA levels of uPAR-cleaving enzymes using RNA-seq data from nonactivated PBMCs and found significantly elevated levels of GPLD1 gene–expressing RNA that encodes phospholipase D (P = 3.6 × 10−5; Figure 1E) in SCD samples. We further tested the activity of the serum proteases using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. Activity of uPA was significantly higher in the plasma obtained from patients with SCD compared with the control participants (P = .033; SCD, n = 16; control, n = 10; Figure 1F). In contrast, no significant differences in the plasmin and neutrophil elastase activity were found (supplemental Figure 4).

PsuPAR levels strongly correlate with the development of CKD.22 Next, we investigated whether suPAR levels correlated with kidney function and stages of CKD in 77 patients with SCD. The cohort’s demographic characteristics and renal function are shown in Table 1. eGFR and CKD stage were determined as described in supplemental Data. We observed strong inversed correlation between plasma log2 (PsuPAR) and log2 (eGFR) (r = −0.5868, R2 = 0.3444, P < .0001; Figure 1G). The correlation was more pronounced in males (r = −0.7611, R2 = 0.5792, P < .0001) and less in females (r = −0.3976, R2 = 0.1581, P = .0091; supplemental Figure 6). In patients with kidney transplants from the general population, urine suPAR (UsuPAR) correlates better than PsuPAR with recurrent kidney disease.23 Thus, we tested a correlation between UsuPAR and eGFR in SCD. Urine concentrations of suPAR were normalized by urine creatinine (CRE). We observed weak positive correlation of urine log2 (UsuPAR/CRE) with log2 (eGFR) (r = 0.2994, R2 = 0.0897, P = .0483; Figure 1H). In the general population, PsuPAR levels also correlate with albuminuria.23 Although log2 (UsuPAR) weakly correlated with log2 (ALB/CRE) (r = −0.1324, R2 = 0.01753, P = .4281; supplemental Figure 7A), log2 (PsuPAR) showed no correlation with albuminuria in patients with SCD (r = −0.02677, R2 = 0.0007, P = .8715; supplemental Figure 7B).

Finally, analysis of the relationship between PsuPAR and UsuPAR and CKD stages showed a strong positive correlation of log2 (PsuPAR) with stages of CKD (r = 0.4788, R2 = 0.2292, P < .0001; Figure 1I). In contrast, log2 (UsuPAR) demonstrated a weak inversed correlation with CKD stages (r = −0.2040, R2 = 0.4160, P = .1842; Figure 1J). A receiver operating characteristic analysis showed high sensitivity and specificity to differentiate CKD stages 2 to 5 from stage 1 at suPAR cutoff level 3.75 ng/ml (sensitivity, 77.78%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 52.36-93.59; specificity, 90%; 95% CI, 55.5-99.75; area under the curve, 0.889; 95% CI, 0.7609-1.017; odds ratio, 7.77; Figure 1K).

In conclusion, we showed that activated SCD PBMCs, macrophages treated with HbS, and elevated phospholipase D and uPA levels in SCD plasma might collectively contribute to higher PsuPAR levels in patients with SCD, and that suPAR strongly correlates with eGFR and CKD progression in SCD. Thus, suPAR may be considered for CKD diagnostic in SCD in the future. The limitation of the study was the small cross-sectional cohort of participants. The APOL1 risk variants and hemoglobinuria were not assessed in this study.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Daniel Stocks for patient recruitment and Songping Wang and Xiaomei Niu for help in the samples’ identification. The authors also thank Castle Raley and Keith Crandall and the George Washington University School of Public Health Genomics Core for library preparation, sequencing, and guidance in data analysis.

This work was supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health (5R01HL125005, 5U54MD007597, 5P30AI117970, 3OT3HL147154, 5P50HL118006, and 5SC1HL150685).

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contribution: N.A., N.K., and M.J. performed experiments; S.D. and J.G.T. recruited study participants and collected samples; F.W., S.N., and M.J. conducted analysis of RNA sequencing data; N.A., S.N., and M.J. designed research and drafted the manuscript; and all authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Marina Jerebtsova, Department of Microbiology, College of Medicine, Howard University, Room 311, 520 W St NW, Washington, DC 20059; e-mail: marina.jerebtsova@howard.edu.

References

Author notes

Data are available on request from the author, Sergei Nekhai (snekhai@howard.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.