Key Points

Adults with SCD will use patient-facing guidelines delivered through an mHealth app.

The results of the trial have implications for improving patient education and reducing hospitalizations for adults with SCD.

Abstract

Despite the increased number of evidence-based guidelines for sickle cell disease (SCD), dissemination of evidence-based guidelines in lay language for individuals or families with SCD has not been evaluated. We conducted a feasibility randomized controlled trial to determine the acceptability of a mobile health (mHealth) app with patient-facing guidelines to improve the knowledge of individuals with SCD about SCD-specific knowledge and reduce hospitalizations. Primary outcome measures include recruitment, retention, and adherence rates. Adults with SCD were enrolled at 2 sickle cell centers between 2018 and 2022. Participants were randomized to receive either an mHealth app + booklet with patient-facing guidelines or a booklet with the guidelines alone. Participants completed surveys at baseline and a final 6-month visit. Approximately 67 of 74 (91%) agreed to participate and were randomized, with 50 of 67 (75%) completing all the study components. All participants who completed the study in the treatment arm used the app. Our results demonstrated high recruitment, retention, and adherence rate for the first randomized trial for an mHealth app with patient-facing guidelines in adults with SCD. This clinical trial was registered at https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ as #NCT03629678.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is an inherited hemoglobin disorder that affects ∼100 000 Americans, most of whom are from socially disadvantaged groups.1-4 Over the past 40 years, SCD has changed from a life-threatening disease of early childhood to a chronic disease with life-threatening vaso-occlusive episodes.5 As with other chronic diseases, evidence-based guidelines advise health care providers about managing SCD and its complications. Although the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI)6 and the American Society of Hematology (ASH)7 published guidelines for the evidence-based management of SCD, knowledge about these guidelines and their disease is a crucial challenge for adults with SCD.8,9 This knowledge gap can result in poor disease self-management, leading to increased hospitalizations and other complications. Improving patient education and knowledge of SCD-specific guidelines is crucial to reducing the burden of the disease.

Low rates of clinical practice guideline use and adherence for health maintenance, treatment, and prevention of complications are common barriers to the long-term health of individuals with SCD.10-16 These problems include low adherence rates for hydroxyurea, low rate of preventive stroke screening, and poor compliance rates with immunization and prophylactic antibiotic recommendations. Traditionally, clinical practice guidelines are written for clinicians, who then use them to inform their disease management recommendations to patients. However, individuals with the disease and their family members play a crucial role in adhering to these guidelines through their behaviors. Well-informed and educated individuals with SCD and their family members can participate in clinical decision making and help shape the extent to which guidelines are applied and adhered to. Improving patient education and knowledge about SCD-specific guidelines can lead to more informed, activated patients. These informed, activated patients will more likely adhere to their shared evidence-based treatment decisions and have better outcomes.

Our prior work demonstrated that individuals want access to SCD-specific guidelines.8,9 They wanted these guidelines in multiple formats, including booklets and mobile health (mHealth) apps. We subsequently developed patient-facing versions of the 2014 NHLBI guidelines in booklets through a process including community-based participatory research8 and an engaging patient-centered mHealth app. Although mHealth apps with patient-facing guidelines could potentially promote patient engagement, increase SCD-specific knowledge, and improve patient outcomes, whether mHealth apps or booklets can deliver patient-facing guidelines and improve knowledge and outcomes is unknown.

To address these knowledge gaps, we conducted a feasibility randomized controlled trial to determine the acceptability of our mHealth app with patient-facing guidelines vs booklets alone with patient-facing guidelines. Using an mHealth app can provide patients easy access to evidence-based guidelines, educational materials, and a platform for monitoring and tracking disease management. This trial assessed the recruitment, retention, and adherence rates of the intervention. We also evaluated the preliminary efficacy of the mHealth app in improving knowledge of SCD-specific guidelines and reducing hospitalizations and acute care utilization.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a feasibility randomized controlled trial at 2 centers: Vanderbilt University Medical Center and the Ohio State University, between 2018 and 2022. The institutional review boards approved the trial at each institution. The inclusion criteria were patients receiving care at the SCD clinic, having a diagnosis of SCD (hemoglobin SS, SC, and Sβ thalassemia), being able to speak and understand written English, having access to a smartphone or computer, and being between the ages of 18 and 70 years. Participants were recruited from SCD clinics, and written informed consent was obtained before randomization. Participants were randomized to 2 arms: (1) the mHealth app + booklet arm, in which participants received the mHealth app and a booklet with patient-facing guidelines, and (2) the booklet-alone arm, in which participants received only a booklet with the patient-facing guidelines.

Participants participated in an initial baseline visit and a 6-month follow-up visit. They were compensated with a $25 gift card for their initial visit and $50 for their 6-month follow-up visit. During the initial visit, after they consented, research personnel told them that the 11 surveys would take ∼45 minutes to complete. Participants then determined whether they could stay and complete the surveys. If participants could stay, they were randomized, given booklets and the mHealth app if they were randomized to the mHealth app + booklet arm or only the booklets if in the booklet-only arm, and then administered baseline surveys. Sometimes participants had to leave during surveys, and then the remaining surveys were sent to them electronically to complete. If they could not stay, they were still randomized, handed the mHealth app and booklet or only a booklet, depending on their randomization, and their baseline surveys were electronically sent for them to complete when they had more time. If participants were randomized to the mHealth app + booklet arm, they were introduced to the mHealth app before they left, which took ∼10 to 15 minutes. A few participants who consented but were not randomized told research personnel that they would not complete surveys if sent electronically. For the population that preferred in-person completion of surveys, research personnel waited until they came in again to randomize them, give them the mHealth app and booklet or only booklet, depending on randomization, and have them complete baseline surveys. The trial ended before some participants could return for another visit and finish enrolling. At the 6-month follow-up visit, surveys were repeated. All survey instruments were available in electronic form (through Research Electronic Data Capture [REDCap]) and administered via iPads.

The mHealth app

The mHealth app consisted of 2 components, an app of web pages with patient-facing guideline material and a REDCap project.

The web application is located at https://www.scdguide.org/. The content in the web app was like that in the booklets previously described.8 Briefly, the web application included sections on an overview, treatments (eg, medications, transfusions, and transplants), complications (eg, acute sickle cell pain, infections, acute chest syndrome, pulmonary hypertension, leg ulcers, strokes, kidney disease, and depression), wellness (eg, women’s health, prevention and screening, avoiding pain triggers, managing stress, taking care of your teeth, diet and exercise, and tobacco, alcohol, and drug use), and a fully searchable glossary to find any topic of interest. The REDCap project included a profile and interactive content to explore and understand the guidelines. Initially, participants could answer questions to create their profiles. In their profile, participants could click links to review guidelines, edit their profile, track their pain, set goals, take chapter quizzes about the guidelines, and create a pain action plan or an asthma action plan. The REDCap project also included the ability to send daily text messages at a time they chose, which contained a message they could create and a link to their profile. In the pain tracker, participants could record their daily pain experience and what they did to manage their pain. They could also record their mood here. Through the goals feature, they could keep track of their weekly goals or goals for the next 6 months. The chapters included quizzes to help review the content from the website with the guidelines. The pain action plan guided individuals through a stepwise approach to managing acute pain at home. The asthma action plan was for people who wanted to create a plan for managing their asthma with their provider. This mHealth app reinforced important points of guideline content and motivated patient engagement through quizzes and text message reminders.

Measurements of the feasibility of the mHealth app required for a phase 3 trial

The feasibility of the trial was measured with 3 outcomes: recruitment, retention, and adherence rates to the mHealth app. The recruitment rate was calculated based on the proportion of participants who were approached, consented, and randomized divided by the number of participants approached. The retention rate was measured based on the proportion of participants who were randomized and elected to remain in the trial and completed all trial components, including the 6-month follow-up surveys. The adherence rate of the app was measured by the proportion of participants who started a patient profile, which allows the viewing of the guidelines, out of the total number who were randomized to the app. We measured additional optional feature app usage, including pain diaries, goalsetting diaries, and quizzes. SCD knowledge was measured with a 40-item questionnaire covering the guidelines. Demographics were self-reported through surveys. Hospitalizations and acute care utilization (hospitalization, emergency room visits, and day-hospital visits) were determined by chart review.

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics, including median and interquartile range for continuous data and percentages for categorical data. Linear and generalized linear models evaluated outcome changes and differences between groups. To assess the change in SCD-specific knowledge, randomized group, baseline SCD-specific knowledge, SCD type, gender identity, and age were included as covariates. For hospitalizations and acute care utilization in the first 6 months after baseline, the randomized group was used as a covariate, and the log number of events within 6 months before baseline plus half of an event was used as the offset in a quasi-Poisson generalized linear model.

Results

Demographics of the 2 arms

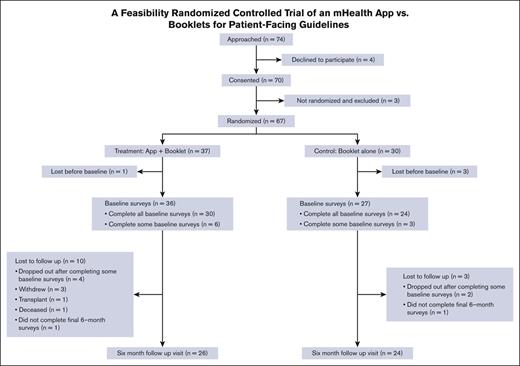

A total of 67 participants were randomly allocated; 37 were enrolled in the mHealth app + booklet arm and 30 in the booklet-alone arm. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the participants, and Figure 1 shows the screening, randomization, and follow-up Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram. Although baseline questionnaires were completed after randomization, there was no imbalance in missing data counts for any variables. Nonetheless, notable imbalances in gender identity (43% male in intervention and 27% in control) and sexual orientation (70% heterosexual in intervention and 80% in control) were present.

Enrollment, retention, and adherence rates were high in the trial

From the 2 centers (Vanderbilt University Medical Center and The Ohio State University), we approached 74 patients and obtained the consent of 70 subjects, of whom 67 were randomized (91% recruitment rate) and 50 completed the 6-month follow-up visit (75% retention rate). Most of the recruited subjects who were not retained did not complete baseline surveys (n = 10). Three patients withdrew, 1 underwent a hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and 1 died. Of the 30 randomly allocated to the intervention who completed the baseline surveys and did not die or have a hematopoietic stem cell transplant before the 6-month follow-up, 30 started setting up a profile on the app, which gave them access to the guidelines, and 29 completed the profile. Of those who created a profile, 6 completed a pain action plan, and 2 completed an asthma action plan. There was a large spread of usage of the diaries feature, with 17 completing only 1 diary, 6 completing 2 to 5 entries, 2 completing 20 to 40, and 5 completing >100. The set goals feature was unused by 2 participants, whereas 19 initiated 1 goal, 8 initiated 2 to 8 goals, and 1 initiated 21 goals. All initiated goals were completed, except for those by 2 participants who initiated 1 goal each. The quizzes feature was unused by 22 participants, whereas 6 completed 1 to 7 quizzes and 2 completed 20 to 21 quizzes.

Early results suggest that both arms improve knowledge

The combined group showed a moderate average change in SCD knowledge for both arms, but there were no differences between the 2 arms. The 95% confidence interval (CI) for the combined group average change indicated a near-null change or positive improvement (mean change, 0.77; standard deviation [SD], 2.89; 95% CI, −0.08 to 1.61; P = .08 compared with no change). However, there was a minimal difference in the change in SCD knowledge between groups (adjusted difference in means, −0.09; 95% CI, −1.84 to 1.66; P = .91).

A trend for decreasing health care use in the mHealth app + booklet arm vs booklet arm

The mHealth app + booklet arm was associated with a moderately lower risk of all-cause hospitalizations and hospitalizations for acute vaso-occlusive pain. The mHealth app + booklet arm was associated with a similar or lower risk of all-cause hospitalizations (relative risk, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.2-1.15; P = .1). The mHealth app + booklet arm was associated with a nonstatistically significant lower risk of hospitalizations for vaso-occlusive pain over the 6 months after baseline (relative risk, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.24-1.41; P = .2). The mHealth app + booklet arm was associated with a nonstatistically significant higher risk of all-cause acute care utilization over the 6 months after baseline (relative risk, 1.44; 95% CI, 0.68-3.05; P = .3). An alternative zero-inflated Poisson model indicated a near-zero association between the randomized arm and acute care utilization, with little evidence of zero inflation for each of the hospitalizations, pain-related hospitalizations, and acute care utilization. We conducted an additional analysis in which we excluded 1 outlier for the acute care utilization because they developed a comorbidity more severe than SCD (a brain tumor), which likely affected his acute care utilization during the study follow-up. After removing that outlier in postbaseline use, the results were in line with those for all hospitalizations and pain hospitalizations; randomization to the mHealth app + booklet arm was associated with similar or lower risk of all-cause acute care utilization over the 6 months after baseline (relative risk, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.27-1.15; P = .1).

Discussion

Guidelines for managing SCD have been developed for providers to provide evidence-based care to the population; however, to our knowledge, no national strategy has been developed thus far to make these guidelines patient centered, accessible, and actionable for adults with SCD. Understanding the guidelines for managing SCD is a major obstacle because they are not written in a manner understandable by individuals or family members of individuals with SCD.17-20 We previously developed booklets with the 2014 NHLBI patient-facing guidelines8; however, individuals with SCD stated they wanted them in an mHealth app.9 Although mHealth apps with SCD-specific guidelines can potentially increase knowledge of the guidelines and patient outcomes, it is unclear whether booklets or mHealth apps would be better for delivering these patient-facing guidelines. To address this significant gap, we designed and implemented a feasibility randomized controlled trial to determine the acceptability (ie, recruitment, retention, and adherence rates) of our mHealth app with patient-facing guidelines vs booklets alone with patient-facing guidelines.

The completion of this trial had 3 crucial findings. First, our results demonstrated high rates of successful recruitment, retention, and adherence to the study and intervention. Other trials have had lower recruitment rates, higher retention rates, and similar adherence rates.21-23 The differences in recruitment and retention rates may be due to our participants agreeing to participate but not completing the baseline surveys because most of them were lost to follow-up before baseline visit completion. This attrition could be due to extensive baseline surveys taking >45 minutes after a 10- to 15-minute mHealth app demonstration and participants being unable to complete the surveys during the clinic visit. Some participants told the research coordinators that they did not want to complete the study surveys after starting them or did not have enough time to complete all surveys in the clinic or at home. This trial was also conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which might have affected the ability of a participant or their desire to stay for extended clinic visits. Shorter baseline visits completed during clinical activities can improve our retention rates, as others have demonstrated.24,25 Finally, we obtained feedback about the trial and intervention through an exit interview survey at the 6-month follow-up visit. In the exit interview, we asked about facilitators and barriers to completing the trial (supplemental Table 1). This feedback could tailor the future larger clinical trial to improve retention rates. However, more feedback obtained through qualitative methods such as semistructured interviews would be helpful in better understanding barriers and facilitators to participation and engagement in future trials. Second, we provided evidence that providing an mHealth app + booklets can potentially reduce hospitalizations and acute care utilization compared with a booklet alone and that both interventions can improve SCD-specific knowledge. Third, we demonstrated that for adults with SCD, in the absence of a completed randomized controlled clinical trial for patient-facing guidelines, an mHealth app is a reasonable strategy to deliver guidelines and improve knowledge and outcomes.

Although many technological interventions have been shown to improve SCD knowledge, none have shown improvement in health care use.26 Our study showed a ∼40% reduction in hospitalizations (P = .1) and acute care utilization (P = .1) with the mHealth app compared with booklets alone. Although both the interventions booklet and app arms improved SCD-specific knowledge, an engaging app could improve SCD-specific health literacy, including knowledge and skills for self-management. The mHealth app had (1) easy accessibility of guidelines from a mobile phone; (2) quizzes that enforce knowledge of the guidelines; (3) an ability to track pain and mood and set health goals; (4) the ability to enter pain action plans and asthma action plans to assist in self-management of pain and asthma at home, potentially preventing acute care utilization; and (5) text message reminders that, although could be used for reminding about the app, might have been used by participants as reminders to take medications or a cue for self-management of their disease. A larger phase 3 trial could demonstrate statistically significant improvement in these critical outcomes.

SCD guidelines will undoubtedly evolve, and any effective tool for their dissemination must be adaptable and self-sustaining. ASH has updated the NHLBI SCD guidelines and developed several committees that created new guidelines.7 Through an iterative process of consultation and revisions with adults with SCD, patient-facing SCD guidelines can be kept up to date and delivered through user-friendly material to the sickle cell community. One of our next steps is to adapt the patient-facing guidelines to include new evidence-based guidelines, including the ASH guidelines for SCD.

As with any feasibility trial, our study has several limitations. First, the sample size was small, and we did not see significant differences in some of our outcomes. A larger randomized controlled trial is the logical next step. Second, we cannot determine how much interaction occurred between participants and the guidelines. Although we measured the steps to access guidelines and other app functionality, we could not directly measure the amount of time and review of the guidelines. Correlating patient educational level or cognitive function to app or booklet utilization and understanding was also not assessed. Further app enhancements could allow for a better understanding of guideline use in the future. Third, chart reviews were done for acute care utilization and hospitalizations, which could be limited by not having a complete history of all hospitals or emergency rooms a participant might have visited. Chart reviews were done in Epic, which allows for review of all acute care utilization received at any other Epic institution through Care Everywhere; however, some hospital systems on other electronic health record systems might have been missed. Finally, there may be other important social determinants of health that affect patient knowledge and adherence to guidelines (eg, participation in a community-based organization) or other health care experiences (eg, discrimination) that we did not assess in this study.

Results of our first-ever patient-facing guidelines feasibility trial, to our knowledge, indicated that adults with SCD are willing to participate in a randomized controlled trial using an mHealth app with patient-facing guidelines and adhere to the trial to improve knowledge and reduce acute care utilization. We also provided preliminary evidence that an mHealth app + booklets can reduce hospitalizations and acute care utilization compared with booklets alone. A larger randomized controlled trial could demonstrate the significant efficacy of the mHealth app in reducing acute care utilization, thereby closing the gap in an effective tool to deliver evolving patient-facing guidelines that can improve patient outcomes. The main findings of our trial provide substantial proof of high recruitment, retention, and adherence rates for the first randomized trial of an mHealth app with patient-facing guidelines in adults with SCD. The results of the trial have important implications for improving patient education and reducing hospitalizations and acute care utilization for adults with SCD.

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly appreciate the help of Chris Simpson, Renee Ashworth, and Alex Minor in recruiting and retaining participants. The authors also greatly appreciate the input from the Vanderbilt Meharry Sickle Cell Center of Excellence, the Sickle Cell Foundation of Tennessee, and the Sickle Cell Disease Association of America on the study and interventions.

This research was partly funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), part of the National Institutes of Health (award number K23HL141447) (R.M.C.).

Authorship

Contribution: M.R.D., L.E.C., and R.M.C. designed the study; N.Q., K.L., and R.M.C. collected the data; P.M.S. and X.L. performed the analyses; M.R.D., P.M.S., X.L., and R.M.C. interpreted the results; R.M.C. and P.M.S. wrote the first version of the manuscript; and before submission, all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.R.D. and his institution are the sponsors of 2 externally funded investigator-initiated research projects, and Global Blood Therapeutics will provide funding for these clinical studies but will not be a cosponsor for either study; M.R.D. does not receive any compensation for the conduct of these 2 investigator-initiated observational studies; is a member of the Global Blood Therapeutics advisory board for a proposed randomized controlled trial, for which he receives compensation; is on the steering committee for a Novartis-sponsored phase 2 trial to prevent priapism in men; was a medical adviser for the development of the CTX001 Early Economic Model; provided medical input on the economic model as part of an expert reference group for Vertex/CRISPR CTX001 Early Economic Model in 2020; and provided consultation to the Forma Pharmaceutical Company about SCD from 2021 to 2022. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Robert M. Cronin, Department of Internal Medicine, The Ohio State University, 370 W 9th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210; e-mail: robert.cronin@osumc.edu.

References

Author notes

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Robert M. Cronin (robert.cronin@osumc.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.