Key Points

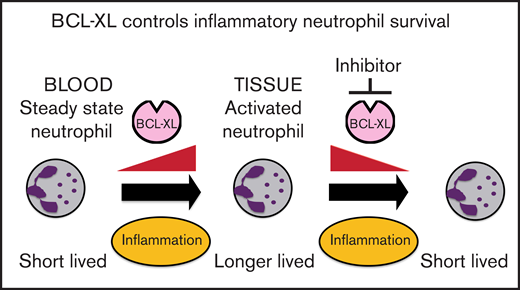

Neutrophils switch to BCL-XL for survival upon exposure to inflammatory cytokines.

Inhibition of BCL-XL preferentially depletes neutrophils from sites of inflammation, but not those circulating in the steady state.

Abstract

Neutrophils help to clear pathogens and cellular debris, but can also cause collateral damage within inflamed tissues. Prolonged neutrophil residency within an inflammatory niche can exacerbate tissue pathology. Using both genetic and pharmacological approaches, we show that BCL-XL is required for the persistence of neutrophils within inflammatory sites in mice. We demonstrate that a selective BCL-XL inhibitor (A-1331852) has therapeutic potential by causing apoptosis in inflammatory human neutrophils ex vivo. Moreover, in murine models of acute and chronic inflammatory disease, it reduced inflammatory neutrophil numbers and ameliorated tissue pathology. In contrast, there was minimal effect on circulating neutrophils. Thus, we show a differential survival requirement in activated neutrophils for BCL-XL and reveal a new therapeutic approach to neutrophil-mediated diseases.

Introduction

Neutrophils (also called polymorphonuclear leukocytes [PMNs]) are the most abundant circulating human leukocyte (∼60%), being produced in bone marrow (BM) at 1011 cells/d1 to balance the normallyshort half-life of terminally differentiated cells released into the peripheral blood.2 However, whencirculating neutrophils are recruited from blood to sites of infection or inflammation, their life span andfunctional effects can be extended by local environmentalfactors.

Neutrophils provide first-line defense against pathogens and cellular debris. They shapeimmune responses through the production of cytokines, chemokines, and direct cell interactions.3 However, neutrophils can also cause tissue damage, such as in rheumatoid arthritis (RA),4 gout,5 and immunopathology in antiviral responses (eg, influenza pneumonia,6 COVID-197).

Neutrophil life span is extended within inflamed tissues by inflammatory cytokines such as granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), tumor necrosis factor, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), and interleukin-1 (IL-1) and IL-6.8 Accordingly, genetic ablation or therapeutic antagonism of these cytokines attenuates many inflammatory diseases.9-12 Although cytokine-targeted biologics offer improved specificity and efficacy compared with traditional anti-inflammatory drugs, some patients do not respond, or lose their response over time.13 Therefore, alternative therapeutic options, particularly targeting aberrant neutrophilic inflammation, are still required.

Apoptosis regulates the life span of immune cells though the BCL-2 family of proteins.14 Anti-apoptotic members (BCL-2, BCL-XL, BCL-W, MCL-1, and A1/BFL-1) bind to pro-apoptotic effectors BAX/BAK, preventing their activation and initiation of cell death. Diverse stress stimuli induce a second pro-apoptotic group, the BH3-only proteins (BID, BIM, PUMA/BBC3, BAD, NOXA/PMAIP, BIK/BLK/NBK, BMF, and HRK/DP5), which selectively compete for binding with the anti-apoptotic proteins, thus facilitating release of BAX/BAK. BAX/BAK then permeabilize the mitochondrial outer membrane, releasing cytochrome c (and other factors such as SMAC/DIABLO) into the cytosol to form the apoptosome, leading to activation of caspases and irreversible demolition of the cell. Certain BH3-only proteins (eg, BIM, PUMA) may activate BAX/BAK directly.15–17

Intriguingly, immune cells rely on distinct anti-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins for their survival.18,19 This requirement may be altered by extrinsic factors such as cytokine exposure20 or cellular activation.18,21,22 Given the profound changes between neutrophils circulating in the peripheral blood and those trafficking to inflamed tissue sites, we reasoned that their reliance on individual survival proteins might also change.

A-1331852 is a highly potent and selective inhibitor of BCL-XL with oral bioavailability that is well tolerated in mice.23,24 All inhibitors of BCL-XL induce rapid and reversible thrombocytopenia23,25,26 because of on-target induction of apoptosis in platelets. Although clinically manageable, this effect complicates clinical translation. However, there is increasing recognition that platelets can amplify inflammation by regulating immune cell recruitment and function.27–29 Neutrophils also appear to interact with platelets to promote thrombosis in severe viral pneumonia (eg, influenza, COVID-19), in addition to causing direct lung damage.30–32 Thus, relative thrombocytopenia may not always be a barrier to the clinical evaluation of BCL-XL inhibitors in inflammatory disease.

Here, we demonstrate that BCL-XL maintains neutrophil survival selectively within inflamed tissues. This survival switch occurs in response to inflammatory cytokines. Concordantly, antagonism of BCL-XL prevented the accumulation of activated neutrophils in synovial, pulmonary, and peritoneal compartments in several inflammatory disease models in mice, but had minimal effect on the numbers of circulating neutrophils or other immune cell populations. As expected, there was depletion of platelets due to their well-documented dependence on BCL-XL for survival.23,25,26 These results provide insight into the differential usage of BCL-2 family members by neutrophils and suggest BCL-XL antagonists be considered for the treatment of inflammatory diseases associated with neutrophil-mediated tissue damage.

Methods

Mice and reagents

All mice were on a C57BL/6 (B6) background and were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions; experiments were approved by the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research animal ethics committee (see supplemental Methods).

A-1331852 (BCL-XL inhibitor; made in house), S63845 (MCL-1 inhibitor; Active Biochem, Kowloon, Hong Kong), and ABT-199 (BCL-2 inhibitor; Active Biochem) were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide for in vitro use. A-1331852 was prepared for in vivo use in vehicle (2.5% dimethyl sulfoxide, 10% ethanol, 27.5% PEG-400, 60% Phosal 50 PG)23 and administered at 100 mg/kg by oral gavage. Tamoxifen (2 mg) was administered by oral gavage in vehicle containing 5% ethanol and 95% corn oil.

Mouse subset analysis, flow cytometry, and cell sorting

Single-cell suspensions from tissues and blood were prepared and analyzed (see supplemental Methods).

Immunoblotting

Whole-cell protein extracts were prepared by lysis in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors and western blotting performed (see supplemental Methods).

Mouse cell culture

For survival assays, cells were cultured at 1 to 2 × 104/well (sorted neutrophils) or 2 to 3 × 105 (unsorted blood leukocytes) in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum and recombinant mouse GM-CSF or G-CSF (R & D Systems) as indicated. Cells were cultured for a minimum 2-hour preconditioning step (37°C, 5% CO2) to allow for sufficient cytokine stimulation, before fresh media containing GM-CSF or G-CSF, and 1 μM A-1331852, S63845, or ABT-199 was added and cells cultured for a further 16 hours. For combination treatment, 2.5 μM dexamethasone (DEX; Sigma) and 1 μM A-1331852 were used. Cells were stained with surface markers (if required) and survival measured by flow cytometry following the addition of propidium iodide (PI) and a standardized number of APC calibration beads. Data show the absolute number of viable (PI−) neutrophils recovered at each condition.

Human sample collection and culture

Synovial fluid was collected by knee arthrocentesis from patients at the Rheumatology Unit, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Melbourne, Australia. Samples of peripheral blood were collected via venipuncture of healthy volunteers through the Volunteer Blood Donor Registry. All samples were obtained under the approval of human ethics committees (Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Royal Melbourne Hospital) with written informed consent from all patients involved. Neutrophils were enriched on a Ficoll-Paque density gradient33 and cultured at 1 to 2 × 104/well in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum and recombinant human GM-CSF or human G-CSF (R & D Systems) as indicated for a minimum of 2 hours before fresh media containing GM-CSF or G-CSF and 1 μM A-1331852, S63845, or ABT-199 was added and cells cultured for a further 16 hours. Cytokine preconditioning was implemented for all experiments (irrespective of in situ exposure) to ensure active stimulation of survival signaling before the addition of drug inhibitors. Upon harvesting, neutrophils were identified by surface staining with anti-CD16-PE and anti-CD66b-APC (both BioLegend); cell survival was measured by flow cytometry following the addition of PI and a standardized number of APC calibration beads. Data show the absolute number of viable (PI−) neutrophils recovered at each condition.

Serum transfer-induced arthritis

Arthritis was induced in male recipients by 100 µL intraperitoneal (IP) injection of pooled serum from arthritic K/BxN mice.34,35 Disease progression was monitored by daily clinical assessment of each paw as follows: 0, no edema/erythema; 1, inflamed digits; 2, mild edema/erythema over 1 surface of paw; 3, edema/erythema involving the entirety of the paw; and 4, edema/erythema involving the entirety of the paw and joint ankylosis. A composite score for each animal comprising the addition of scores from each paw (4 in total; maximum score, 16 per animal) is shown. Experiments displayed are pooled from a minimum of n = 2 experiments with therapeutic intervention commencing when mice display signs of established disease (days 2-4; average arthritis score, 6-7).

OVA model of allergic lung inflammation

Lung inflammation was induced as described.36 Mice were immunized IP with 200μl alum/ovalbumin (OVA) comprising 20 μg low-endotoxin chicken ovalbumin (Worthington) and 2.25 mg aluminum hydroxide (Sigma-Aldrich) in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) on day 1 (d1) and d7. Mice were rested for 3 weeks before being challenged daily for 4 consecutive days with nebulized 2% (w/v) OVA (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS for 15 minutes. Mice were bled a minimum of 2 hours following the last dose of drug, euthanized, underwent bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), and spleen and femur collected.

Peritonitis

Peritonitis was induced by IP injection with either 10 μg lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Sigma-Aldrich) or 1 mg monosodium urate (MSU) crystals (InvivoGen) in PBS. Mice were bled and euthanized 16 to 18 hours after drug treatment as indicated with peritoneal lavage and spleen collected. For methylated bovine serum albumin (mBSA)-specific peritonitis, mice were sensitized to antigen by intradermal injection of 200 μg mBSA in complete Freund adjuvant on d0 and incomplete Freund adjuvant on d14 with peritonitis induced by IP injection of 200 μg mBSA in PBS on d21 as described.37 Mice were bled and peritoneal lavage collected on d28.

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons were made using a 2-tailed Student t test (Prism v 9.0 software, Graphpad, CA). Data were shown as the means ± standard deviation (SD) or standard error of the mean (SEM) as indicated with P values < .05 considered statistically significant.

Results

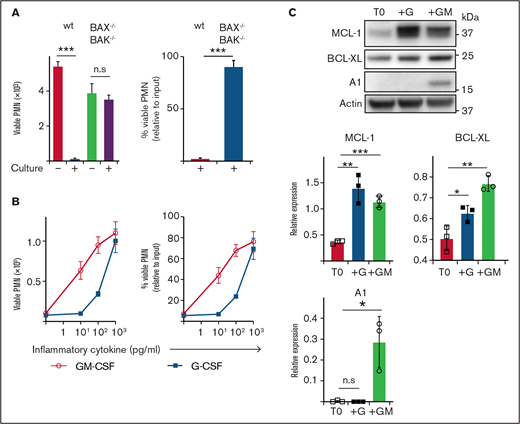

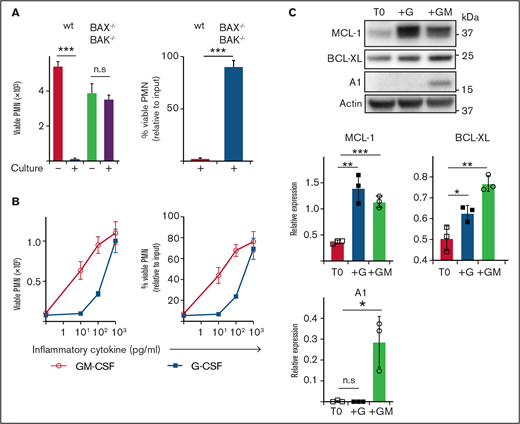

Neutrophil apoptosis is reduced under inflammatory conditions correlating with increased expression of anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family proteins

Neutrophils are short-lived under steady-state conditions in vitro and in vivo; however, exposure to inflammatory cytokines greatly extends their survival. To explore this effect, we cultured mouse neutrophils in vitro. Although B6 (wild type ) neutrophils underwent extensive spontaneous death after 16 hours of culture (>95% dead), consistent with death occurring via apoptosis, neutrophils lacking critical effectors BAX/BAK (BAX−/−BAK−/−) were completely resistant (<5% dead) (Figure 1A). Exposure to inflammatory cytokines GM-CSF or G-CSF reduced spontaneous apoptosis, with ∼80% viable neutrophils recovered after culture (1 ng/mL) (Figure 1B). Anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family proteins MCL-1, A1 and BCL-XL have all been implicated in regulating mature neutrophil apoptosis.38–41 Conversely, mature neutrophils express very little BCL-2, even under G- or GM-CSF stimulation, although it is readily detectable in immature precursors.41–44 Freshly isolated neutrophils expressed MCL-1 and BCL-XL, but no detectable A1 (Figure 1C). Culture with GM-CSF significantly increased the levels of MCL-1, BCL-XL, and A1. Culture with G-CSF also significantly increased MCL-1 and BCL-XL, but did not induce A1 expression. Based on these results, we hypothesized that MCL-1 or BCL-XL (or both) could be maintaining neutrophil survival through a pathway common to both GM-CSF and G-CSF cytokine signaling.

Enumeration of and expression of anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family proteins by mouse neutrophils recovered after culture. (A) B6 (wild type) or BAX−/−BAK−/− viable neutrophil (PMN) recovery was assessed before or after culture in standard media (B) B6 neutrophils were cultured with or without GM-CSF or G-CSF at the indicated dose for 16 hours before the number of viable PMN was determined by flow cytometry. Data are shown as mean ± SD of viable PMN per well. Data show a single representative experiment of n = 3 experiments. (C) Western blot analysis was performed on freshly isolated B6 mouse neutrophils (T0) or those cultured with 5 ng/mL G-CSF (+G) or 5 ng/mL GM-CSF (+GM). Data from n = 3 independent experiments with protein expression displayed relative to actin loading control. Data analyzed using a 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

Enumeration of and expression of anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family proteins by mouse neutrophils recovered after culture. (A) B6 (wild type) or BAX−/−BAK−/− viable neutrophil (PMN) recovery was assessed before or after culture in standard media (B) B6 neutrophils were cultured with or without GM-CSF or G-CSF at the indicated dose for 16 hours before the number of viable PMN was determined by flow cytometry. Data are shown as mean ± SD of viable PMN per well. Data show a single representative experiment of n = 3 experiments. (C) Western blot analysis was performed on freshly isolated B6 mouse neutrophils (T0) or those cultured with 5 ng/mL G-CSF (+G) or 5 ng/mL GM-CSF (+GM). Data from n = 3 independent experiments with protein expression displayed relative to actin loading control. Data analyzed using a 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

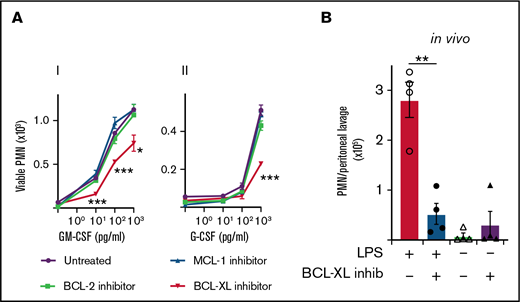

BCL-XL inhibitor A-1331852, but not inhibitors of MCL-1 or BCL-2, restores neutrophil apoptosis under inflammatory conditions

Given that both MCL-1 and BCL-XL levels correlated with cytokine-mediated survival, we next tested the effect of inhibiting each of these proteins, as well as BCL-2, on neutrophil viability in vitro. Mouse leukocytes were cultured with or without G-CSF or GM-CSF before selective inhibitors of MCL-1 (S63485), BCL-XL (A-1331852), or BCL-2 (ABT-199) were added and cells cultured for a further 16 hours. As expected (Figure 1), few viable neutrophils were recovered in the absence of inflammatory cytokines irrespective of drug treatment (Figure 2A). Although neutrophils cultured with MCL-1 or BCL-2 inhibitors showed similar survival responses to both GM-CSF and G-CSF relative to drug-naïve controls, the survival of neutrophils cultured with BCL-XL inhibitor was significantly impaired (Figure 2Ai,ii). BCL-XL inhibitor reduced the recovery of viable neutrophils at all concentrations of GM-CSF tested compared with control (0.01, 0.1, 1 ng/mL GM-CSF) (Figure 2Ai). It also significantly reduced neutrophil recovery at concentrations of G-CSF that promoted survival (1 ng/mL) (Figure 2Aii). Neutrophils lacking BAX/BAK (BAX−/−BAK−/−) were completely resistant to death induced by all drug inhibitors (supplemental Figure 1). As expected,14 the MCL-1 and BCL-2 inhibitors effectively killed B cells present within the mixed leukocyte cultures, confirming pharmacological activity (supplemental Figure 2). As reported previously, neutrophils genetically deficient in A1 survived equally as well as A1-sufficient controls when cultured with GM-CSF,45 unless BCL-XL function was also impaired (supplemental Figure 3). To confirm our results within a pathophysiologically relevant setting, we tested BCL-XL inhibition in mice in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a known inducer of inflammatory cytokines such as GM-CSF in vivo.46 Mice were injected with LPS IP to induce sterile peritonitis before treatment with either BCL-XL inhibitor or vehicle control by oral gavage. Other controls included mice that did not receive LPS before treatment. LPS administration induced significant IP neutrophil recruitment. Concordant with our in vitro data, viable neutrophil numbers in the peritoneal cavity of BCL-XL inhibitor treated LPS-induced mice were markedly reduced (>fivefold) compared with vehicle-treated LPS-induced mice, so much so that the recovery was comparable to mice that never received LPS stimulation (Figure 2B). These data implicate BCL-XL as an important mediator of neutrophil survival under inflammation both in vitro and in vivo.

Mouse neutrophils require BCL-XL for enhanced survival during inflammation. (A) Leukocytes from B6 mice were preconditioned in culture in the presence or absence of their respective inflammatory cytokines (i) GM-CSF or (ii) G-CSF at the indicated dose for 16 hours. Cells were then cultured in the presence or absence of 1 µM BCL-XL inhibitor (A-1331852), MCL-1 inhibitor (S63845), or BCL-2 inhibitor (ABT-199). After 16 hours, viable neutrophils (PMN) were enumerated by flow cytometry. Data are shown as mean ± SD of viable PMN per well. Data show a single representative experiment of n = 3 experiments. (B) B6 mice were injected with 10 µg LPS or PBS control IP. Sixteen hours later mice were treated with 100 mg/kg BCL-XL inhibitor or vehicle by oral gavage. After 16 hours, peritoneal cells were recovered by lavage and viable PMN enumerated by PI staining and flow cytometry. Data show a single representative experiment of 2 experiments; n = 4 animals/group; mean ± SEM . All data were analyzed using a 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

Mouse neutrophils require BCL-XL for enhanced survival during inflammation. (A) Leukocytes from B6 mice were preconditioned in culture in the presence or absence of their respective inflammatory cytokines (i) GM-CSF or (ii) G-CSF at the indicated dose for 16 hours. Cells were then cultured in the presence or absence of 1 µM BCL-XL inhibitor (A-1331852), MCL-1 inhibitor (S63845), or BCL-2 inhibitor (ABT-199). After 16 hours, viable neutrophils (PMN) were enumerated by flow cytometry. Data are shown as mean ± SD of viable PMN per well. Data show a single representative experiment of n = 3 experiments. (B) B6 mice were injected with 10 µg LPS or PBS control IP. Sixteen hours later mice were treated with 100 mg/kg BCL-XL inhibitor or vehicle by oral gavage. After 16 hours, peritoneal cells were recovered by lavage and viable PMN enumerated by PI staining and flow cytometry. Data show a single representative experiment of 2 experiments; n = 4 animals/group; mean ± SEM . All data were analyzed using a 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

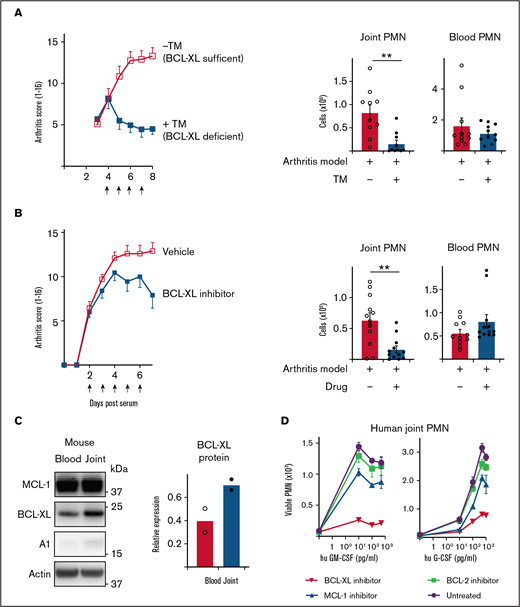

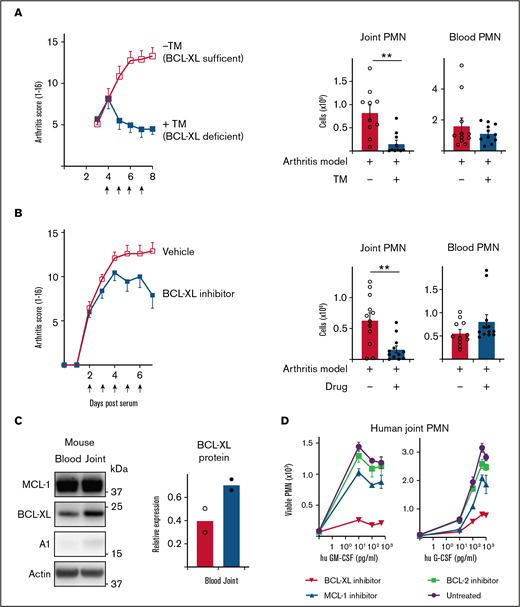

Inhibition of BCL-XL kills neutrophils from inflamed human and mouse joints and halts the progression of STIA. (A) STIA was induced in Rosa26CreERT2.Bcl-xfl/fl mice. Arthritic mice were treated for 4 days with 2 mg tamoxifen (+TM) or vehicle control (−TM) by oral gavage starting day 4 postserum injection to induce deletion of Bcl-x leading to loss of BCL-XL protein (as indicated by arrows). Following treatment (d8 postserum injection), PMN were enumerated in joint and blood by PI staining and flow cytometry. Data show pooled data from n = 2 experiments; 10-11 animals/group; mean ± SEM. (B) STIA was induced in B6 mice by IP injection of K/BxN serum. Arthritic mice were treated for 5 days with 100 mg/kg BCL-XL inhibitor or vehicle by oral gavage, starting d2 postserum injection (as indicated by arrows). Disease severity was measured using a standardized visual scoring system.74 Following inhibitor treatment (d7 postserum injection) PMN were enumerated in joint and blood by PI staining and flow cytometry. Data shown were pooled from 2 experiments (n = 10/group STIA); mean ± SEM. (C) Joint and blood PMN were sorted from arthritic mice and western blot analysis performed to assess MCL-1, BCL-XL, A1, and actin expression. BCL-XL expression is displayed relative to actin loading control. Data shown were pooled from 2 experiments (n = 10/group); mean ± SEM. (D) Cell aspirates were obtained from inflamed joints of inflammatory arthritis patients and enriched for neutrophils on a Ficoll gradient. Cells were preconditioned in culture in the presence or absence of GM-CSF or G-CSF at the indicated dose for 16 hours. Cells were then cultured in the presence or absence of 1 µM BCL-XL inhibitor (A-1331852), MCL-1 inhibitor (S63845), or BCL-2 inhibitor (ABT-199). After 16 hours, viable PMN were enumerated by flow cytometry. Data are shown as mean ± SD of PMN recovery per well. Data show a single representative experiment of n = 2 experiments. All data were analyzed using a 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

Inhibition of BCL-XL kills neutrophils from inflamed human and mouse joints and halts the progression of STIA. (A) STIA was induced in Rosa26CreERT2.Bcl-xfl/fl mice. Arthritic mice were treated for 4 days with 2 mg tamoxifen (+TM) or vehicle control (−TM) by oral gavage starting day 4 postserum injection to induce deletion of Bcl-x leading to loss of BCL-XL protein (as indicated by arrows). Following treatment (d8 postserum injection), PMN were enumerated in joint and blood by PI staining and flow cytometry. Data show pooled data from n = 2 experiments; 10-11 animals/group; mean ± SEM. (B) STIA was induced in B6 mice by IP injection of K/BxN serum. Arthritic mice were treated for 5 days with 100 mg/kg BCL-XL inhibitor or vehicle by oral gavage, starting d2 postserum injection (as indicated by arrows). Disease severity was measured using a standardized visual scoring system.74 Following inhibitor treatment (d7 postserum injection) PMN were enumerated in joint and blood by PI staining and flow cytometry. Data shown were pooled from 2 experiments (n = 10/group STIA); mean ± SEM. (C) Joint and blood PMN were sorted from arthritic mice and western blot analysis performed to assess MCL-1, BCL-XL, A1, and actin expression. BCL-XL expression is displayed relative to actin loading control. Data shown were pooled from 2 experiments (n = 10/group); mean ± SEM. (D) Cell aspirates were obtained from inflamed joints of inflammatory arthritis patients and enriched for neutrophils on a Ficoll gradient. Cells were preconditioned in culture in the presence or absence of GM-CSF or G-CSF at the indicated dose for 16 hours. Cells were then cultured in the presence or absence of 1 µM BCL-XL inhibitor (A-1331852), MCL-1 inhibitor (S63845), or BCL-2 inhibitor (ABT-199). After 16 hours, viable PMN were enumerated by flow cytometry. Data are shown as mean ± SD of PMN recovery per well. Data show a single representative experiment of n = 2 experiments. All data were analyzed using a 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

Inducible deletion ofBcl-x or treatment with BCL-XL inhibitor A-1331852 depletes neutrophils from inflamed joints and attenuates established disease in mice with experimental arthritis

Serum transfer-induced arthritis (STIA) is a neutrophil-dependent experimental mouse model of RA that mimics the effector phase of human disease.47,48 The transfer of autoreactive serum from arthritic K/BxN mice leads to deposition of immune complexes in joints and recruitment of neutrophils and other innate leukocytes leading to cartilage loss, bone erosion, and other clinical features of human RA. To test the requirement for BCL-XL in maintaining neutrophil survival in this model, we used Rosa26CreERT2.Bcl-xfl/fl mice whereby Bcl-x (and thus BCL-XL) could be globally deleted by tamoxifen administration.49,50 Disease was induced by serum transfer (d0) and allowed to establish as determined by daily clinical assessment of arthritis score. On d4 postserum, mice were dosed daily for 4 days with tamoxifen to induce Bcl-x deletion and euthanized on d8. Remarkably, although arthritis in BCL-XL-sufficient mice became more severe as expected, BCL-XL-deficient mice did not worsen (Figure 3A). Concordant with the arthritis scores, joints recovered from BCL-XL-deficient mice contained significantly fewer neutrophils (fourfold) compared with those of BCL-XL-sufficient mice (Figure 3A), whereas numbers of blood neutrophils between the 2 groups were not significantly different.

Next, we repeated the experiments using BCL-XL inhibitor drug A-1331852.23,24 In these experiments, mice were gavaged with BCL-XL inhibitor or vehicle commencing day 2 postserum, when all mice showed signs of clinical disease. Mice were dosed daily for 5 days and euthanized on d7. Concordant with the genetic-deletion data, BCL-XL inhibitor reduced the progress in clinical severity compared with vehicle controls (Figure 3B) and also significantly reduced neutrophil numbers in joints (threefold) but not in blood (Figure 3B) or BM (supplemental Figure 4). Interestingly, when neutrophils from control animals were assessed for BCL-2 family protein expression, BCL-XL was found to be upregulated in joint compared with blood, consistent with enhanced expression resulting from local inflammation (Figure 3C; supplemental Figure 5).

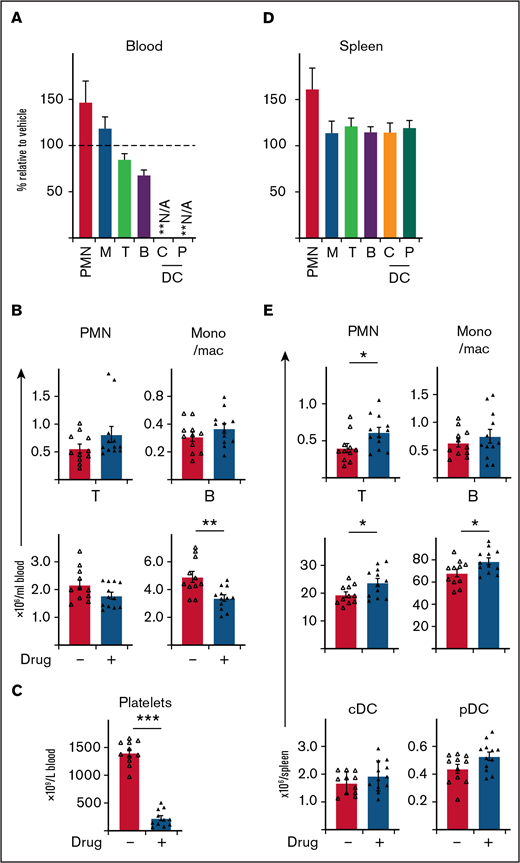

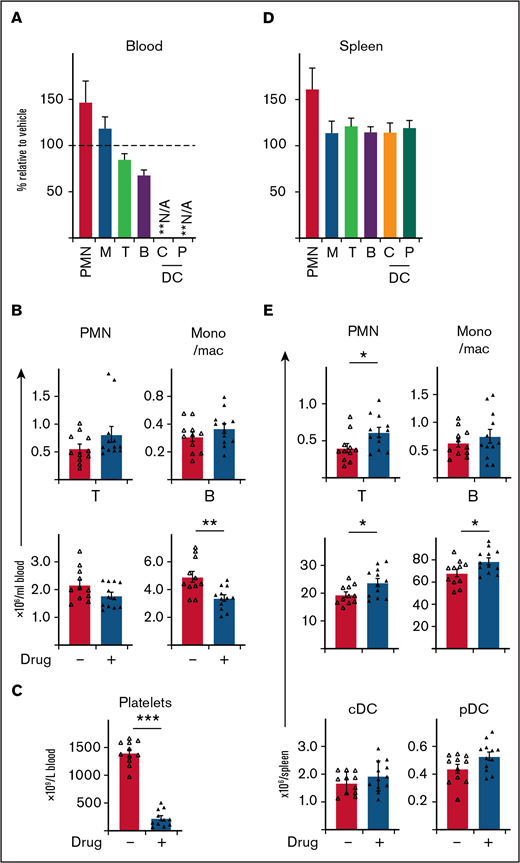

BCL-XL inhibitor preferentially targets neutrophils at sites of inflammation, without systemic depletion of other immune cell populations in mice, apart from platelets. STIA was induced in B6 mice by IP injection of K/BxN serum. Arthritic mice were treated for 5 days with 100 mg/kg BCL-XL inhibitor or vehicle by oral gavage starting d2 postserum injection. Following inhibitor treatment (d7 postserum injection) viable neutrophils (PMN), monocyte/macrophage (mono/mac; M), T cells (T), B cells (B), plasmacytoid dendritic cell (pDC; P), conventional dendritic cell (cDC; C) were enumerated in (A-B) blood and (D-E) spleen by PI staining and flow cytometry. Platelets were enumerated in whole blood by analysis on an Advia 2120i automated hematological analyzer (C). Data shown were pooled from 2 experiments (n = 10 mice/group; mean ± SEM). All data analyzed using a 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

BCL-XL inhibitor preferentially targets neutrophils at sites of inflammation, without systemic depletion of other immune cell populations in mice, apart from platelets. STIA was induced in B6 mice by IP injection of K/BxN serum. Arthritic mice were treated for 5 days with 100 mg/kg BCL-XL inhibitor or vehicle by oral gavage starting d2 postserum injection. Following inhibitor treatment (d7 postserum injection) viable neutrophils (PMN), monocyte/macrophage (mono/mac; M), T cells (T), B cells (B), plasmacytoid dendritic cell (pDC; P), conventional dendritic cell (cDC; C) were enumerated in (A-B) blood and (D-E) spleen by PI staining and flow cytometry. Platelets were enumerated in whole blood by analysis on an Advia 2120i automated hematological analyzer (C). Data shown were pooled from 2 experiments (n = 10 mice/group; mean ± SEM). All data analyzed using a 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

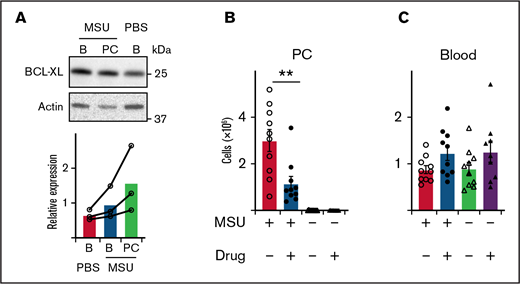

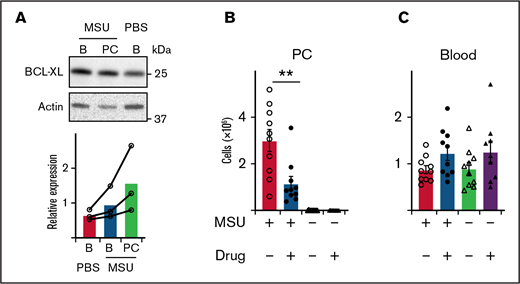

BCL-XL inhibitor kills neutrophils elicited during MSU-induced peritonitis in a mouse model of gout. (A) B6 mice were injected with 1 mg MSU crystals IP or left untreated (PBS). Blood (B) and peritoneal cavity (PC) neutrophils were sorted by flow cytometry 16 hours later, and western blot analysis performed to determine the amount of BCL-XL and actin protein. BCL-XL expression is shown relative to actin loading control. A line connects data from each separate experiment. (B-C) B6 mice were injected with MSU crystals IP or left untreated. Four hours post-MSU mice were treated with 100 mg/kg BCL-XL inhibitor or vehicle control by oral gavage. Sixteen hours later, (B) peritoneal or (C) blood cells were collected and neutrophils enumerated by PI staining and flow cytometry. Data shown were pooled from 2 experiments (n = 10/group; mean ± SEM). All data were analyzed using a 2-tailed Student t test. **P < .01.

BCL-XL inhibitor kills neutrophils elicited during MSU-induced peritonitis in a mouse model of gout. (A) B6 mice were injected with 1 mg MSU crystals IP or left untreated (PBS). Blood (B) and peritoneal cavity (PC) neutrophils were sorted by flow cytometry 16 hours later, and western blot analysis performed to determine the amount of BCL-XL and actin protein. BCL-XL expression is shown relative to actin loading control. A line connects data from each separate experiment. (B-C) B6 mice were injected with MSU crystals IP or left untreated. Four hours post-MSU mice were treated with 100 mg/kg BCL-XL inhibitor or vehicle control by oral gavage. Sixteen hours later, (B) peritoneal or (C) blood cells were collected and neutrophils enumerated by PI staining and flow cytometry. Data shown were pooled from 2 experiments (n = 10/group; mean ± SEM). All data were analyzed using a 2-tailed Student t test. **P < .01.

To determine whether these findings extrapolated to humans, we obtained synovial fluid neutrophils from human patients with inflammatory joint disease and blood from healthy controls, and tested their BCL-2 protein requirements under inflammation in vitro. Enriched neutrophils were cultured with or without human GM-CSF or G-CSF for at least 2 hours before inhibitors of MCL-1 (S63485), BCL-XL (A-1331852), or BCL-2 (ABT-199) were added and cells cultured for a further 16h. Concordant with our mouse data (Figures 1 and 2) and published literature,51,52 few viable neutrophils were recovered after culture in the absence of cytokine (Figure 3D). Addition of G- or GM-CSF improved neutrophil viability, an effect attenuated by BCL-XL inhibitor treatment (Figure 3D). Interestingly, although blood PMN from healthy donors exposed to inflammatory cytokines were preferentially sensitive to BCL-XL inhibition, MCL-1 inhibitor also had a significant effect (supplemental Figure 6).

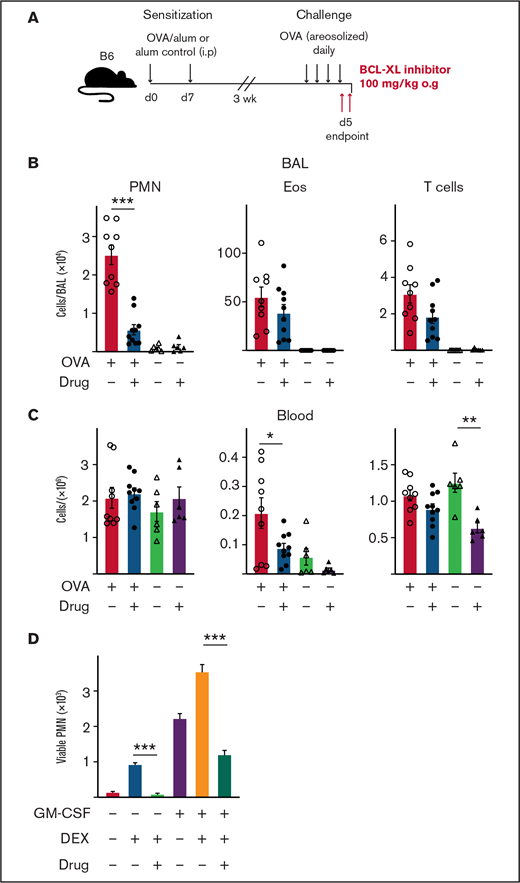

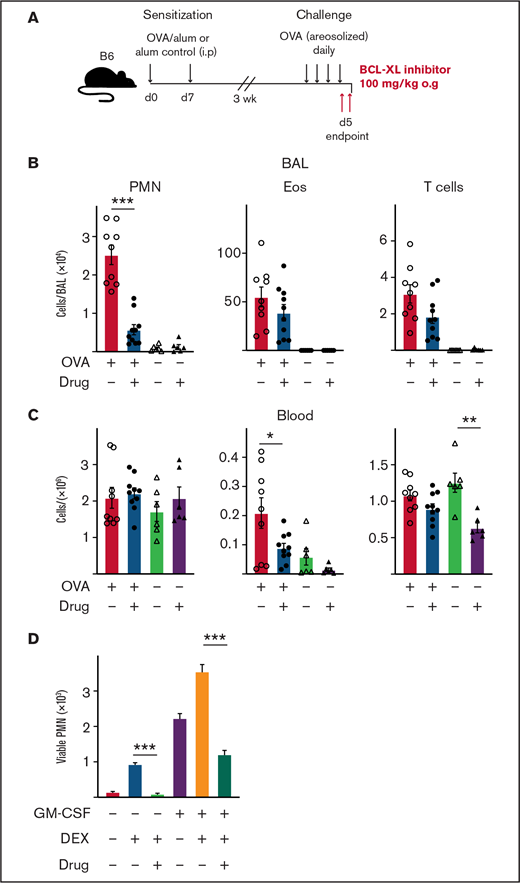

Treatment with BCL-XL inhibitor A-1331852 preferentially depletes lung-infiltrating neutrophils during airway inflammation in mice. B6 mice were sensitized to OVA protein by IP injection of alum/OVA or alum alone control on d0 and d7. After 3 weeks, mice were challenged daily for 4 consecutive days with aerosolized OVA. Mice were gavaged orally with either the BCL-XL inhibitor or vehicle on d4 after OVA challenge, and again the following morning 2 hours before organ harvest. (A) Schematic of the OVA model of airway inflammation. Upon end point, (B) BAL and (C) blood were collected and the number of viable neutrophils (PMN), eosinophils (Eos), and T cells were determined by PI staining and flow cytometry. Data shown is pooled from 2 experiments (n = 4-6 mice/group; mean ± SEM). All data were analyzed using a 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001. (D) PMN were cultured with various combinations of 1 µM BCL-XL inhibitor A-1331852, 2.5 µM DEX, and 0.1 ng/mL GM-CSF. After 16 hours, viable PMN were enumerated by flow cytometry. Data shown as mean ± SD of viable PMN per well. Data show a single representative experiment of n = 3 experiments. All data were analyzed using a 2-tailed Student t test. ***P < .001.

Treatment with BCL-XL inhibitor A-1331852 preferentially depletes lung-infiltrating neutrophils during airway inflammation in mice. B6 mice were sensitized to OVA protein by IP injection of alum/OVA or alum alone control on d0 and d7. After 3 weeks, mice were challenged daily for 4 consecutive days with aerosolized OVA. Mice were gavaged orally with either the BCL-XL inhibitor or vehicle on d4 after OVA challenge, and again the following morning 2 hours before organ harvest. (A) Schematic of the OVA model of airway inflammation. Upon end point, (B) BAL and (C) blood were collected and the number of viable neutrophils (PMN), eosinophils (Eos), and T cells were determined by PI staining and flow cytometry. Data shown is pooled from 2 experiments (n = 4-6 mice/group; mean ± SEM). All data were analyzed using a 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001. (D) PMN were cultured with various combinations of 1 µM BCL-XL inhibitor A-1331852, 2.5 µM DEX, and 0.1 ng/mL GM-CSF. After 16 hours, viable PMN were enumerated by flow cytometry. Data shown as mean ± SD of viable PMN per well. Data show a single representative experiment of n = 3 experiments. All data were analyzed using a 2-tailed Student t test. ***P < .001.

Taken together, these data demonstrate a requirement for BCL-XL expression in the pathogenesis of RA, suggesting a particular role in the maintenance of neutrophils within locally inflamed joints, but not in steady-state systemic circulation.

Treatment with BCL-XL inhibitor A-1331852 does not induce systemic depletion of most immune cell populations in arthritic mice, with the exception of platelets

To further explore the therapeutic utility of BCL-XL inhibitors in inflammatory diseases, we next determined drug effects on other immune cells. BCL-XL inhibitor treatment was repeated in STIA mice as described previously and then immune cells in blood and spleen assessed. Remarkably, BCL-XL inhibitor treatment had little effect on most immune populations (Figure 4). Within blood, no reduction in monocyte/macrophage or T-cell populations were observed; as expected (Figure 3B), circulating neutrophils were also not reduced (Figure 4A-B). There was a small (statistically significant) reduction in circulating B cells. Most notably, the number of circulating platelets was substantially reduced in BCL-XL inhibitor treated mice compared with vehicle controls, demonstrating effective drug-mediated inhibition of BCL-XL function (Figure 4C).23,25,26 Within the spleen, no reduction in the numbers of any immune cell populations was observed; there was a small increase in the numbers of neutrophils and lymphocytes (both T and B) (Figure 4E).

These data demonstrate that BCL-XL inhibitor treatment is highly selective for depletion of inflammatory neutrophils and circulating platelets within STIA mice, with little effect on other immune cells.

Treatment with BCL-XL inhibitor A-1331852 rapidly depletes neutrophils from the peritoneal cavity in an experimental mouse model of gout

Next, we considered if BCL-XL inhibition could also effectively treat other neutrophil-mediated inflammation. MSU-induced peritonitis in mice simulates immune responses seen in human gout. Leukocyte recruitment is mediated by a cascade of inflammatory cytokines, most prominently IL-1, with neutrophils pivotal in pathogenesis.53 We induced peritonitis in mice by IP injection of 1 mg MSU and 16 hours later sorted neutrophils harvested from peritoneal cavity (PC) or blood. Control mice were injected with saline. Concordant with our arthritis findings discussed previously, neutrophils isolated from the inflamed peritoneal cavity of MSU-treated mice trended toward higher BCL-XL expression compared with those from blood from the same animals, or blood from controls, although this did not reach statistical significance (Figure 5A). We observed a similar neutrophil effect when peritonitis was induced in sensitized mice by injection of mBSA (supplemental Figure 7). Blood neutrophils from MSU treated animals appeared to have slightly higher BCL-XL expression compared with blood neutrophils from untreated controls (Figure 5A). Minimal BCL-2 expression was detected in neutrophils under any condition (supplemental Figure 8). To determine whether BCL-XL inhibition could ameliorate MSU peritonitis, we gavaged mice with BCL-XL inhibitor or vehicle control 5 hours after MSU injection. Peritoneal cells were harvested 16 hours after MSU injection. As expected, MSU induced marked neutrophil recruitment to the PC compared with saline alone (Figure 5B). MSU-induced neutrophil infiltration was reduced threefold (P < .01) by BCL-XL inhibitor compared with vehicle control treatment (Figure 5B). No difference in the number of circulating blood neutrophils was detected between any of the groups of mice (Figure 5C).

These data support the idea that BCL-XL dependence is common to neutrophils in inflamed sites.

Treatment with BCL-XL inhibitor A-1331852 preferentially depletes neutrophils, above other lung-infiltrating immune cells, in a mouse model of airway inflammation

Our results indicate that BCL-XL inhibition can deplete neutrophils from inflamed tissue. Next, we tested selective BCL-XL inhibition on neutrophils in a disease model where other inflammatory cells (eg, eosinophils) predominate. The classical OVA challenge model of airway inflammation is a T cell-dependent model that induces eosinophil, neutrophil, and T-cell recruitment to the lungs of sensitized mice.36,54 Mice were sensitized on d0 and d7 by IP injection of either OVA/alum or alum alone. After 3 weeks, mice were challenged with aerosolized OVA daily for 4 days to establish lung inflammation before being treated orally with either BCL-XL inhibitor or vehicle, as indicated (Figure 6A). Mice were euthanized 2 to 3 hours following the last dose of treatment. As expected, OVA/alum mice treated with vehicle developed pulmonary inflammation with marked increases in eosinophils, neutrophils, and T cells in the BAL (Figure 6B). Strikingly, BCL-XL inhibition led to a fivefold reduction in the number of BAL neutrophils, whereas the numbers of eosinophils and T cells were not significantly different from vehicle controls (Figure 6B). Numbers of blood neutrophils were unaffected by BCL-XL inhibition (Figure 6C). Under these conditions, the number of blood eosinophils and T cells were also modestly reduced in drug-treated mice compared with vehicle (Figure 6C).

Although eosinophilic airway inflammation can be effectively controlled by treatment with conventional glucocorticoid therapy, neutrophilic airway inflammation is often refractory.55 Therefore, we compared the sensitivity of neutrophils to glucocorticoids (DEX), BCL-XL inhibitor, or both, with or without GM-CSF stimulation in vitro (Figure 6D). Addition of DEX promoted neutrophil survival, which was further enhanced under GM-CSF. Notably, BCL-XL inhibitor reduced the ability of DEX alone or DEX/GM-CSF combination to promote neutrophil survival (10-fold and threefold, respectively). Thus, BCL-XL inhibition restored neutrophil sensitivity to apoptosis, even during glucocorticoid-enhanced survival, in the presence or absence of an inflammatory cytokine. These data show that BCL-XL inhibition preferentially depletes neutrophils in inflammatory tissue sites, even during glucocorticoid treatment.

Discussion

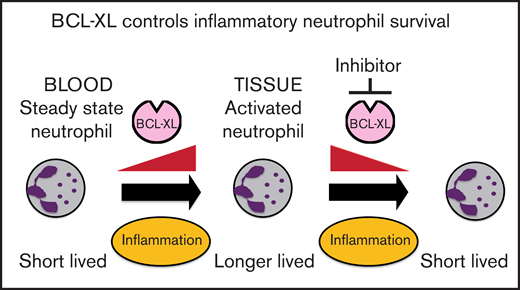

In steady-state, mature neutrophils have a short life span, but this is extended during inflammation in response to local environmental cues. Failure to appropriately regulate neutrophil life span can contribute to tissue damage and chronicity in inflammatory diseases.56 Conversely, if inflammatory neutrophil survival is insufficient, clearance of pathogens and cellular debris may be impaired. Thus, identifying proteins that control neutrophil survival under different conditions may provide selective targets for therapy.

We have identified BCL-XL as a critical regulator of inflammatory neutrophils, but not circulating neutrophils in the steady-state. Concordant with previous reports, freshly isolated neutrophils underwent apoptosis in vitro because removal of critical apoptotic effectors BAX and BAK completely prevented cell death. This response changed markedly with exposure to inflammatory cytokines GM-CSF or G-CSF (Figures 1-3). Although MCL-1 and BCL-XL both increased in mouse neutrophils exposed to inflammatory cytokines, only deficiency in BCL-XL attenuated extended survival under these conditions (Figures 2 and 3). Human neutrophils exposed to inflammatory cytokines were also preferentially sensitive to BCL-XL inhibition (Figure 3D), with those from blood showing additional codependence on MCL-1 (supplemental Figure 6). Concordant with previous reports,51,52 neutrophil viability was significantly compromised without exogenous cytokines, even when cells were isolated from highly inflamed tissues such as rheumatic joints (Figure 3D). This suggests the extended survival induced by inflammatory cytokines requires continuous exposure in situ, a mechanism that may contribute to removal of inflammatory neutrophils once local cytokine tapers.

MCL-1 is required for circulating neutrophil survival. Mice with neutrophils deficient in MCL-1 develop severe neutropenia57,58 and spontaneous apoptosis of human blood neutrophils correlates with loss of MCL-1 protein.44,59 Circulating steady-state neutrophils do not express BCL-2, or BCL-W,41,44,60 but do express BAX and BAK.44,61 In contrast, we show that inflammatory neutrophils under diverse conditions depend on BCL-XL. This likely represents a “switch” from steady-state survival maintained by short-lived MCL-1 (0.5- to 3-hour half-life) to inflammatory-state survival, mediated by longer lived BCL-XL (∼16-hour half-life).42,62 Our finding that activation status influences BCL-XL may also explain why expression of BCL-XL in neutrophils has been contentious.39–41,44,63 We acknowledge that circulating neutrophils may become sensitive to BCL-XL inhibition under systemic inflammation (eg, sepsis), or when appreciable amounts of inflammatory cytokines access the circulation during tissue inflammation.

This switch to BCL-XL dependency in inflammatory milieus offer therapeutic selectivity by BCL-XL inhibition. We used several different murine models of inflammatory diseases and to treat with BCL-XL inhibitor after disease commencement. In each case, we found a significant reduction in inflammatory neutrophils, with little effect on the numbers of BM or circulating neutrophils, or other immune cells (Figure 4). This was highlighted in STIA, a model of human RA. BCL-XL inhibition led to marked clinical improvement (Figure 3A-B) on par with that of neutrophil-depleting antibody RB6-8C5 when given at a similar time in the course of established disease,64 as well as other therapies shown to provide clinical benefit to RA patients including anti-GM-CSF,65 corticosteroids,66 and methotrexate.67

The specificity of this drug treatment was highlighted in the OVA lung model, where BCL-XL inhibitor reduced inflammatory neutrophil numbers, but not the predominant eosinophil population. This effect may have resulted from IL-5-induced BCL-2 expression in lung eosinophils, enabling their survival in the absence of BCL-XL function.68,69 Lung infiltrating neutrophil numbers often correlate with disease severity, and is inversely predictive of treatment success.70,71 Although corticosteroids are commonly used against inflammation, neutrophils are refractory72; indeed, survival may even be prolonged.73 We found that BCL-XL inhibition was able to attenuate even DEX-extended neutrophil survival (Figure 6D).

Here, we show that a BCL-XL inhibitor can selectively target neutrophils in inflamed sites, without causing systemic neutropenia. These data provide compelling preclinical rationale to carefully evaluate inhibitors of individual BCL-2 family members, such as BCL-XL, as a new approach to reducing the severity and chronicity of inflammatory diseases.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lisa Reid, Rhiannan Crawley, Marina Patsis, Rebekah Meeny, Teisha Mason, Sophia Russo, Tom Kitson, and Lauren Wilkins for technical assistance. The authors also thank David Huang for reagents and advice regarding the preparation of BH3 mimetic compounds.

This work was supported by Arthritis Australia (Grant-in-Aid to E.C. and C.L.), Rebecca L. Cooper Foundation, Reid Charitable Trusts (I.W.), and National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) grants and fellowships (#1143976, #1150425, #1080321, #1105209 to A.L.; #1113577 to I.W.; and #1125436 to C.K). The NHMRC Independent Research Institutes Infrastructure Support Scheme grant (361646) and the Victorian State Government Operational Infrastructure Support grant is acknowledged.

Authorship

Contribution: E.C., A.M.L., C.L., I.W., and C.K. designed research; E.C., C.L., T.K., Y.Y., M.H., N.I., A.W., D.D., J.H., R.M.S., and Y.Z. performed research; P.C., M.J.H., R.A., C.W., D.N., G.L., W.W., N.H., J.R., V.B., and R.S. contributed vital new reagents or analytical tools; E.C., C.L., and T.K. collected, analyzed, and interpreted data; and E.C., C.L., I.W., and A.L. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: All relevant authors are employees of The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research. This institute receives milestone and royalty payments for the development of BH3 mimetic drugs. Employees of The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute may be eligible for financial benefits related to these payments. All other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Emma Carrington, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, 1G Royal Parade, Parkville, 3052, Australia; e-mail: Carrington@wehi.edu.au.

References

Author notes

E.M.C. and C.L. contributed equally to this work.

I.P.W. and A.M.L. contributed equally to this work.

For original data, please contact the corresponding author: Emma Carrington (carrington@wehi.edu.au).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.