CD4+CD56+ malignancies are rare hematologic neoplasms, which were recently shown to correspond to the so-called type 2 dendritic cell (DC2) or plasmacytoid dendritic cells. This study presents the biologic and clinical features of a series of 23 such cases, selected on the minimal immunophenotypic criteria defining the DC2 leukemic counterpart, that is, coexpression of CD4 and CD56 in the absence of B, T, and myeloid lineage markers. Clinical presentation typically corresponded to cutaneous nodules associated with lymphadenopathy or spleen enlargement or both. Cytopenia was frequent. Circulating malignant cells were often detected. Massive bone marrow infiltration was seen in 20 of 23 (87%) patients. Most tumor cells exhibited nuclei with a lacy chromatin, a blastic aspect, large cytoplasm-containing vacuoles or microvacuoles beside the plasma membrane, and cytoplasmic expansions resembling pseudopodia. Other immunophenotypic characteristics included both negative (CD16, CD57, CD116, and CD117) and positive (CD36, CD38, CD45 at low levels, CD45RA, CD68, CD123, and HLA DR) markers. The prognosis was rapidly fatal in the absence of chemotherapy. Complete remission was obtained in 18 of 23 (78%) patients after polychemotherapy. Most patients had a relapse in less than 2 years, mainly in the bone marrow, skin, or central nervous system. Considering these clinical and biologic features, the conclusion is made that CD4+CD56+malignancies constitute a genuine homogeneous entity. Furthermore, some therapeutic options were clearly identified. Finally, relationships between the pure cutaneous indolent form of the disease and acute leukemia as well as with the lymphoid/myeloid origin of the CD4+CD56+ malignant cell are discussed.

Introduction

CD4+CD56+ malignancies are rare hematopoietic tumors described initially by Brody et al1 and later also reported by others.2,3These tumors seem to be characterized by a frequent skin involvement and a rapid aggressive course with bone marrow infiltration and are referred to as blastic natural killer (NK) lymphoma/leukemia in the World Health Organization classification.4 Most of these tumors have been diagnosed from skin biopsies as CD56+ NK lymphoma1-3 or as hematologic neoplasms, the latter referring to the absence of an identified cellular counterpart.5,6 These malignancies were postulated to correspond to an entity different from myeloid/NK cell acute leukemia.7 Indeed, myeloid/NK cell acute leukemias are characterized by the expression of such myeloid markers as CD11b, CD33, and myeloperoxidase (MPO) antigen in conjunction with CD7 and CD56 expression.8 By contrast, CD4+CD56+ malignancies usually lack the expression of conventional myeloid and lymphoid T- and B-cell markers.6

In an effort to better define the CD4+CD56+entity, a multicenter study was conducted by the French GEIL group (Groupe d'Etude Immunologique des Leucémies) on this rare hematopoietic tumor. Phenotypic, molecular, and functional studies, conducted in our group, revealed striking similarities between these leukemias and a subtype of dendritic cells, the so-called plasmacytoid dendritic cell (DC) or type 2 dendritic cell (DC2), allowing the proposition that CD4+CD56+ leukemia might correspond to DC2 malignancies.9

Here, we present the clinical and biologic features of a series of 23 patients. Patients were selected on minimal immunophenotypic criteria allowing the recognition of the phenotypic criteria of DC2 leukemic counterpart, corresponding to the coexpression of CD4 and CD56 molecules in the absence of expression of the T-cell markers CD3 and CD5, the B-cell markers CD19 and 20, and the myeloid markers CD13, CD33, and MPO antigen. We show that strict application of these immunophenotypic criteria allows definition of a homogeneous entity in terms of clinical behavior, cytology, and immunophenotypic profile. Therefore, analysis of this series identifies the key clinical and biologic features allowing the diagnosis of this disease and identifies some therapeutic options.

Patients, materials, and methods

Selection of patients

A multicenter study was conducted by the GEIL on CD4+CD56+ malignancies with bone marrow involvement. Preliminary analysis of a series of 11 patients, defined on the basis of the coexpression of CD4 and CD56 molecules on neoplastic cells, led to the recognition of 9 patients for whom the immunophenotypic profile of tumor cells was homogeneous, that is, CD4+, CD56+, CD13−, CD33−, MPO−, CD3− (both surface and intracytoplasmic), CD5−, CD19−, and CD20−. Therefore, databases of each local center working with the GEIL were screened for patients having hematologic malignancies corresponding to this immunophenotype. The result was the definition of a series of 23 patients corresponding to these criteria. Cells isolated from patients 2, 6, 7, 8, 11, and 18 have been previously characterized regarding plasmacytoid DC differentiation.9 Data on patients 3 and 23 have already been reported.6 10

Morphologic analysis

Bone marrow aspirates and peripheral blood films, stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa, were observed by 2 reviewers (J.F. and F.V.) and systematically stored on the Leica-Tribvn telemedecine system database (Paris, France) for further comparison. The blast cells were classified according to their size, nuclear outline, presence of one or several nucleoli, chromatin density, and amount and structure of cytoplasm. Dysplastic features in myeloid lineage were investigated. Bone marrow smears were available for patients 1 and 15, at a time when they displayed myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). These smears were also reviewed. Cytochemical techniques used for MPO and esterase (α-naphtyl butyrate esterase or naphtyl ASD acetate) detection, were performed according to standard techniques.

Immunophenotypic profile of CD4+CD56+malignant cells

Tumor cells from bone marrow or peripheral blood cells were characterized by flow cytometry after double or triple immunolabeling according to the European Group for the Immunological Characterization of Leukemias (EGIL) recommendations.11 CD56 expression was also systematically evaluated by flow cytometry. CD16, CD36, CD38, CD45, CD56, CD71, CD117, HLA DR, and CD45RA, were tested in some cases as indicated in Tables 2 and 3. Interleukin 3 receptor (IL-3R; CDw123, clone 18774B, Pharmingen, Heidelberg, Germany) and granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor receptor (GM-CSFR; CD116, clone 33335B, Pharmingen) expression were tested by 3 of us (M.C.J., M.M., and B.D.) as described elsewhere.9 Expression of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) was evaluated by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for patients 6, 7, and 8, as described.9 CD68 expression was evaluated by immunocytochemistry on cell smears or on tissue biopsies in 12 cases.

Results

Clinical characteristics

The patients were selected on the basis of the immunophenotype of bone marrow or blood tumor cells. Immunophenotypic criteria were defined as follows: tumor cells should coexpress CD4 and CD56 and should not express CD13, CD33, MPO, CD3 (either at the surface and intracytoplasmic), CD5, CD19, and CD20. The reported series of 23 patients was issued from 12 different centers and were diagnosed over a period of 8 years from 1992 to 2000.

Detailed clinical characteristics at diagnosis are provided in Tables1 and 2. There were 17 males and 6 female patients. Three patients were children (2, 9, and 12, respectively, 8, 6, and 14 years old). Two patients were young adults (22 and 23, respectively, 28 and 29 years old). Eighteen patients were over 55 years of age. Altogether the median age was 69 years old (range, 5-86 years). Patients 10 and 14 had a family history of neoplasm. Patients 1 and 15 had a past history of MDS (1 refractory anemia [RA] and 1 refractory anemia with excess blasts [RAEB]).

Clinical characteristics and patient follow-up

| Patient no. . | Age/sex . | Past history . | Past treatment . | Extramedullary sites of involvement . | Initial therapy5-152 . | CR/PR . | Outcome Relapse . | Survival . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin . | Lymph node . | Spleen . | Other . | ||||||||

| 15-150 | 76/M | RA | Symptomatic | + | + | + | Symptomatic | No | 3 mo+ | ||

| 2 | 8/M | None | None | + | + | + | + | Cytarabine, mitoxantrone | CR | Yes, at mo 12 | 37 mo+ |

| 3 | 86/F | None | None | + | Symptomatic | No | 3 mo+ | ||||

| 4 | 81/F | None | None | + | + | Cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone | CR | Yes, at mo 6 | 12 mo+ | ||

| 5 | 68/F | None | None | + | Lomustine, adriamycin, cytarabine | CR | Yes, at mo 18 | 22 mo | |||

| 6 | 69/M | None | None | + | + | + | Cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone | CR | Yes, at mo 12 | 12 mo+ | |

| 7 | 75/M | None | None | + | + | VP16/AraC/ifosfamide | CR | Yes, at mo 4 | 6 mo+ | ||

| 8 | 72/M | None | None | + | + | Cyclophosphamide, epirubicine, vincristine, prednisone | PR | Yes, at mo 9 | 23 mo+ | ||

| 9 | 6/F | None | None | + | + | Rubidomycine, prednisone, asparaginase, vincristine + allogenic BMT at the first CR | CR | No | 98 mo | ||

| 10 | 55/M | One son dead of AML3 | None | + | Lomustine, adriamycin, cytarabine | CR | Yes, at mo 15 | 16 mo+ | |||

| 115-151 | 79/M | None | None | + | Cyclophosphamide, VP16, prednisone | CR | Yes, at mo 6 | 8 mo+ | |||

| 12 | 14/M | None | None | + | Vincristine, prednisone, daunorubicin, asparaginase5-151 | CR | No | 10 mo | |||

| 135-151 | 74/M | None | None | + | VP16/ifosfamide | CR | Yes, at mo 6 | 17 mo+ | |||

| 14 | 74/F | One sister with breast carcinoma | None | + | Vincristine, 6-mercaptopurine, cyclophosphamide, cytarabine | CR | No | 5 mo | |||

| 155-150 | 67/M | RAEB + cutaneous nodule | Electron-therapy + caryolysine + hydroxyurea | + | + | + | Idarubicine, cytarabine | CR | Yes, at mo 3 | 5 mo | |

| 16 | 75/F | None | None | + | + | + | + | Prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, daunorubicin | No | 9 mo+ | |

| 17 | 60/M | None | None | + | + | Lomustine, adriamycin, cytarabine | CR | Yes, at mo 8 | 9 mo+ | ||

| 18 | 82/M | None | None | + | Vincristine, cyclophosphamide, adriamycin | CR | 4 mo | ||||

| 19 | 56/M | Cutaneous nodules one month before | None | + | + | Daunorubicin, cytarabine | CR | Yes, at mo 9 | 13 mo+ | ||

| 20 | 67/M | None | None | + | + | + | 6-Mercaptopurine, methotrexate, prednisone | PR | Yes, at mo 5 | 12 mo | |

| 21 | 70/M | None | + | + | + | + | Cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone | CR | Yes, at mo 6 | 7 mo+ | |

| 225-151 | 28/M | None | None | + | Cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine, prednisone, allogenic BMT at the first CR | CR | Yes, at mo 12 | 38 mo+ | |||

| 23 | 29/M | None | None | + | Cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine, prednisone, allogenic BMT at the first CR | CR | No | 76 mo | |||

| Frequencies | 17/M (74%), 6/F (26%) | 19/23 (83%) | 12/23 (52%) | 9/23 (39%) | 6/23 (26%) | 18 CR (78%) | 15 relapses/ 18 (83%), | Median = 12 mo | |||

| 2 PR (9%) | Median, 9 mo | (range 3-96 mo) | |||||||||

| 14/23 (61%) with both | |||||||||||

| Patient no. . | Age/sex . | Past history . | Past treatment . | Extramedullary sites of involvement . | Initial therapy5-152 . | CR/PR . | Outcome Relapse . | Survival . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin . | Lymph node . | Spleen . | Other . | ||||||||

| 15-150 | 76/M | RA | Symptomatic | + | + | + | Symptomatic | No | 3 mo+ | ||

| 2 | 8/M | None | None | + | + | + | + | Cytarabine, mitoxantrone | CR | Yes, at mo 12 | 37 mo+ |

| 3 | 86/F | None | None | + | Symptomatic | No | 3 mo+ | ||||

| 4 | 81/F | None | None | + | + | Cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone | CR | Yes, at mo 6 | 12 mo+ | ||

| 5 | 68/F | None | None | + | Lomustine, adriamycin, cytarabine | CR | Yes, at mo 18 | 22 mo | |||

| 6 | 69/M | None | None | + | + | + | Cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone | CR | Yes, at mo 12 | 12 mo+ | |

| 7 | 75/M | None | None | + | + | VP16/AraC/ifosfamide | CR | Yes, at mo 4 | 6 mo+ | ||

| 8 | 72/M | None | None | + | + | Cyclophosphamide, epirubicine, vincristine, prednisone | PR | Yes, at mo 9 | 23 mo+ | ||

| 9 | 6/F | None | None | + | + | Rubidomycine, prednisone, asparaginase, vincristine + allogenic BMT at the first CR | CR | No | 98 mo | ||

| 10 | 55/M | One son dead of AML3 | None | + | Lomustine, adriamycin, cytarabine | CR | Yes, at mo 15 | 16 mo+ | |||

| 115-151 | 79/M | None | None | + | Cyclophosphamide, VP16, prednisone | CR | Yes, at mo 6 | 8 mo+ | |||

| 12 | 14/M | None | None | + | Vincristine, prednisone, daunorubicin, asparaginase5-151 | CR | No | 10 mo | |||

| 135-151 | 74/M | None | None | + | VP16/ifosfamide | CR | Yes, at mo 6 | 17 mo+ | |||

| 14 | 74/F | One sister with breast carcinoma | None | + | Vincristine, 6-mercaptopurine, cyclophosphamide, cytarabine | CR | No | 5 mo | |||

| 155-150 | 67/M | RAEB + cutaneous nodule | Electron-therapy + caryolysine + hydroxyurea | + | + | + | Idarubicine, cytarabine | CR | Yes, at mo 3 | 5 mo | |

| 16 | 75/F | None | None | + | + | + | + | Prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, daunorubicin | No | 9 mo+ | |

| 17 | 60/M | None | None | + | + | Lomustine, adriamycin, cytarabine | CR | Yes, at mo 8 | 9 mo+ | ||

| 18 | 82/M | None | None | + | Vincristine, cyclophosphamide, adriamycin | CR | 4 mo | ||||

| 19 | 56/M | Cutaneous nodules one month before | None | + | + | Daunorubicin, cytarabine | CR | Yes, at mo 9 | 13 mo+ | ||

| 20 | 67/M | None | None | + | + | + | 6-Mercaptopurine, methotrexate, prednisone | PR | Yes, at mo 5 | 12 mo | |

| 21 | 70/M | None | + | + | + | + | Cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone | CR | Yes, at mo 6 | 7 mo+ | |

| 225-151 | 28/M | None | None | + | Cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine, prednisone, allogenic BMT at the first CR | CR | Yes, at mo 12 | 38 mo+ | |||

| 23 | 29/M | None | None | + | Cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine, prednisone, allogenic BMT at the first CR | CR | No | 76 mo | |||

| Frequencies | 17/M (74%), 6/F (26%) | 19/23 (83%) | 12/23 (52%) | 9/23 (39%) | 6/23 (26%) | 18 CR (78%) | 15 relapses/ 18 (83%), | Median = 12 mo | |||

| 2 PR (9%) | Median, 9 mo | (range 3-96 mo) | |||||||||

| 14/23 (61%) with both | |||||||||||

“Other” was liver for patients 1, 2, 15, 16, and 21; tonsils for patients 6 and 21; lung, eyes, and CNS for patient 6. lomustine, indicates lomustine; BMT, bone marrow transplantation; CR, complete remission; PR, partial remission; No, absence of remission; +, death. In case of relapse, the date of the first relapse is indicated. Patient 9 was treated according to EORTC58881 VHR protocol, patient 12 according to the FRALLE 2000-BT protocol, and patient 15 according to the GOELAL protocol for adults.

Diagnosis of refractory anemia without excess of blasts (RA) 3 years previously for patient 1; diagnosis of RAEB 2 years previously for patient 15.

Initial cutaneous localization and secondary medullary dissemination.

Generic names are followed by their proprietary products: cytarabine, Aracytine; cyclophosphamide, Endoxan; ifosfamide, Holoxan; mitoxantrone, Novantrone; vincristine, Oncovin; 6-mercaptopurine, Purinethol.

Peripheral blood cell counts and bone marrow infiltration

| Patient no. . | Peripheral blood . | % blasts in bone marrow . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (× 109/L) . | Neutro (× 109/L) . | Hb (g/dL) . | PLT (× 109/L) . | % Blasts . | ||

| 1 | 12.7 | 6 | 8 | 40 | 16 | 63 |

| 2 | 2.8 | 1 | 7 | 82 | 6 | 70 |

| 3 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 7 | 570 | 56 | 87 |

| 4 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 11 | 56 | 16 | 44 |

| 5 | 4 | 3 | 12 | 141 | 1 | 67 |

| 6 | 3.8 | 2.2 | 12.7 | 98 | 2 | 40 |

| 7 | 4.9 | < 0.1 | 11.6 | 132 | 0 | 74 |

| 8 | 4.9 | 2.3 | 11 | 132 | 0 | 74 |

| 9 | 9.3 | 4 | 8.8 | 51 | 6 | 90 |

| 10 | 4 | 2.4 | 12.3 | 156 | 0 | 80 |

| 11* | 2.4 | 1.5 | 15 | 201 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 65 | 2.6 | 8.4 | 40 | 78 | 96 |

| 13* | 3.4 | 2 | 15.5 | 133 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | 2.7 | 1.8 | 11.7 | 80 | 0 | 74 |

| 15 | 1 | 1.6 | 8.8 | 78 | NE | 60 |

| 16 | 72 | 5 | 7 | 27 | 89 | 90 |

| 17 | 5.6 | 2.6 | 13 | 126 | 15 | 100 |

| 18 | 32.9 | 1.9 | 13.5 | 34 | 94 | 92 |

| 19 | 11.6 | 6 | 11.9 | 169 | 0 | 52 |

| 20 | 1.9 | 0.95 | 10.3 | 107 | NE | 21 |

| 21 | 11.8 | 6.1 | 9.9 | 75 | 2 | 48 |

| 22* | 8.8 | 6 | 13.5 | 413 | 0 | 0 |

| 23 | 3.1 | 0.93 | 9.7 | 101 | 5 | 90 |

| Frequencies | 13/21 (62%) | 20/23 (87%) | ||||

| Median | 4 | 2.1 | 11 | 101 | 2 | 67 |

| Range | 1-72 | < 0.1-6.1 | 7-15.5 | 27-570 | 0-94 | 0-100 |

| Patient no. . | Peripheral blood . | % blasts in bone marrow . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (× 109/L) . | Neutro (× 109/L) . | Hb (g/dL) . | PLT (× 109/L) . | % Blasts . | ||

| 1 | 12.7 | 6 | 8 | 40 | 16 | 63 |

| 2 | 2.8 | 1 | 7 | 82 | 6 | 70 |

| 3 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 7 | 570 | 56 | 87 |

| 4 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 11 | 56 | 16 | 44 |

| 5 | 4 | 3 | 12 | 141 | 1 | 67 |

| 6 | 3.8 | 2.2 | 12.7 | 98 | 2 | 40 |

| 7 | 4.9 | < 0.1 | 11.6 | 132 | 0 | 74 |

| 8 | 4.9 | 2.3 | 11 | 132 | 0 | 74 |

| 9 | 9.3 | 4 | 8.8 | 51 | 6 | 90 |

| 10 | 4 | 2.4 | 12.3 | 156 | 0 | 80 |

| 11* | 2.4 | 1.5 | 15 | 201 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 65 | 2.6 | 8.4 | 40 | 78 | 96 |

| 13* | 3.4 | 2 | 15.5 | 133 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | 2.7 | 1.8 | 11.7 | 80 | 0 | 74 |

| 15 | 1 | 1.6 | 8.8 | 78 | NE | 60 |

| 16 | 72 | 5 | 7 | 27 | 89 | 90 |

| 17 | 5.6 | 2.6 | 13 | 126 | 15 | 100 |

| 18 | 32.9 | 1.9 | 13.5 | 34 | 94 | 92 |

| 19 | 11.6 | 6 | 11.9 | 169 | 0 | 52 |

| 20 | 1.9 | 0.95 | 10.3 | 107 | NE | 21 |

| 21 | 11.8 | 6.1 | 9.9 | 75 | 2 | 48 |

| 22* | 8.8 | 6 | 13.5 | 413 | 0 | 0 |

| 23 | 3.1 | 0.93 | 9.7 | 101 | 5 | 90 |

| Frequencies | 13/21 (62%) | 20/23 (87%) | ||||

| Median | 4 | 2.1 | 11 | 101 | 2 | 67 |

| Range | 1-72 | < 0.1-6.1 | 7-15.5 | 27-570 | 0-94 | 0-100 |

WBC indicates white blood cell count; Neutro, neutrophils; Hb, hemoglobin; PLT, platelets; NE, not evaluated.

Initial cutaneous localization and secondary medullary dissemination.

Skin lesions were observed at diagnosis for 19 of 23 (83%) patients and 14 of 23 (61%) patients had lymphadenopathy or splenomegaly or both. It is noteworthy that isolated skin lesions were the initial cause of the first medical advice. The patients were usually otherwise in good health, with no systemic symptoms. If not immediately treated, the skin lesions were always rapidly disseminating. These skin lesions were heterogeneous in size but usually at least 1 cm in diameter, purple, easily visible, and infiltrating the dermis (Figure1). When performed, skin biopsies revealed a histopathologic aspect similar to that described by Petrella et al,6 corresponding to a dense dermal infiltration with malignant cells without epidermal involvement. Other sites of the disease at diagnosis included the liver (4 of 23 patients), tonsils (2 of 23 patients), lungs, eyes, and central nervous system (CNS; patient 2).

Clinical appearance of skin lesions from 2 patients.

Obvious multiple cutaneous nodular erythematous purple lesions are seen. (A) Patient 10. (B) Patient 6. Magnification, × 1.

Clinical appearance of skin lesions from 2 patients.

Obvious multiple cutaneous nodular erythematous purple lesions are seen. (A) Patient 10. (B) Patient 6. Magnification, × 1.

Thrombopenia was noted in 18 of 23 patients (78%), anemia in 15 of 23 (65%), leukoneutropenia in 8 of 23 (34%), and leukocytosis in 5 of 23 (22%) patients. Overall, only 2 of 23 (9%) displayed no cytopenia. Levels of peripheral malignant cells ranged between 1% to 94% in 13 of 21 (62%) patients. Bone marrow involvement was observed in 20 of 23 (87%) patients at diagnosis. The 3 patients (11, 13, and 22) with no detectable bone marrow involvement at diagnosis had isolated cutaneous lesions.

Morphologic and cytochemical features

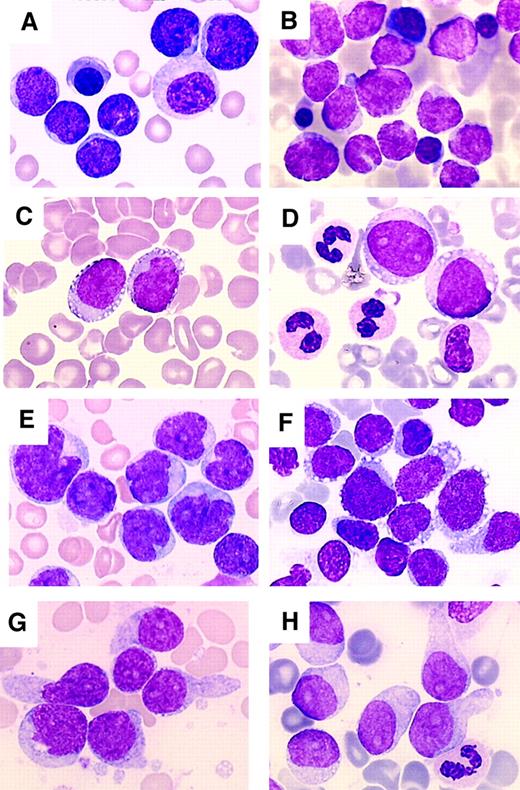

Morphologic analysis of bone marrow aspirates showed most often hypercellular bone marrow with a high count of neoplastic cells. The size of neoplastic cells was variable. In the majority of cases the proliferation was quite homogeneous with cells of small/medium (9 patients) or medium/large size (7 patients). In the other 7 patients the population was heterogeneous with a mixture of small, medium, and large cells. The cells usually had a large amount of cytoplasm (19 of 23, 83% cases with a medium or low nucleus-cytoplasm ratio). In all cases the cytoplasm displayed a clearly heterogeneous structure with faint basophilia and no granulation. Cytoplasmic vacuolation, caused probably by glycogen deposits, was a frequent feature (19 of 23, 83%). These vacuoles were small (numerous microvacuoles) or large. A peculiar arrangement of the vacuoles as in a pearl necklace along the cytoplasmic outline was often observed (Figure2). Another frequent feature was the presence of pseudopodia-shaped cytoplasmic expansions (15 of 23, 65%). The nucleus was usually of regular shape (13 of 23, 57%). In the other 10 patients (43%), a high number of cells showed an irregular nuclear configuration with notched, folded, or bilobar features. The nuclear chromatin pattern was loose, neither fine nor condensed in 13 patients. In the other 10 patients, the chromatin was lacy with a blastic appearance. Nucleoli were easily seen in a variable number of cells in 15 patients. In 2 patients, all cells displayed a prominent nucleolus. Mitotic figures were absent or scarce except in 6 patients (Figure 2shows the different cytologic aspects of CD4+CD56+ tumor cells). The MPO and esterase reactions were negative in all instances. Morphologic analysis of peripheral blood smears showed neoplastic cells of blastic appearance in 13 patients (> 0.5 × 109/L).

Morphologic aspects of CD4+CD56+ tumor cells.

May-Grunwald staining of bone marrow smears. (A) Patient 1. (B) Patient 2. (C) Patient 8. (D) Patient 4. (E) Patient 12. (F) Patient 9. (G) Patient 17. (H) Patient 10. CD4+CD56+ tumor cells may correspond to small cells with a nucleus of a regular shape, a lacy chromatin, and a high nucleus/cytoplasm ratio (A and B). Cells may be larger with still a lacy chromatin and with a regularly shaped (C and D) irregular or indented (E) nucleus. The chromatin often presents a typical blastic appearance (F-H). Nucleoli are often clearly visible (A, C-E, G, and H). The size of blast cells may be heterogeneous (E and F). Tumor cells often display cytoplasmic vacuolation arranged as a pearl necklace along the cytoplasmic outline (C and D) or forming microvacuoles giving a heterogeneous aspect to the cytoplasm (F-H). Pseudopodialike membrane expansions are also frequent (F-H). Dysplastic features may be noted (A and D). Magnification, × 1000.

Morphologic aspects of CD4+CD56+ tumor cells.

May-Grunwald staining of bone marrow smears. (A) Patient 1. (B) Patient 2. (C) Patient 8. (D) Patient 4. (E) Patient 12. (F) Patient 9. (G) Patient 17. (H) Patient 10. CD4+CD56+ tumor cells may correspond to small cells with a nucleus of a regular shape, a lacy chromatin, and a high nucleus/cytoplasm ratio (A and B). Cells may be larger with still a lacy chromatin and with a regularly shaped (C and D) irregular or indented (E) nucleus. The chromatin often presents a typical blastic appearance (F-H). Nucleoli are often clearly visible (A, C-E, G, and H). The size of blast cells may be heterogeneous (E and F). Tumor cells often display cytoplasmic vacuolation arranged as a pearl necklace along the cytoplasmic outline (C and D) or forming microvacuoles giving a heterogeneous aspect to the cytoplasm (F-H). Pseudopodialike membrane expansions are also frequent (F-H). Dysplastic features may be noted (A and D). Magnification, × 1000.

Significant dysplastic features of one or more cell lines were observed in 5 patients: trilineage dysplasia of moderate grade in 1, dysgranulopoiesis and dyserythropoiesis in 1, and dysgranulopoiesis in 3. Examination of bone marrow smears from the 2 patients with a prior history of MDS (patients 1 and 15) at time of diagnosis of the MDS evidenced a trilineage dysplasia for these patients. Blast cell count was below 1% for patient 1. Patient 15 had 5% blasts at the time of MDS diagnosis. The morphology of blast cells at the time of MDS diagnosis was not related to that of CD4+CD56+tumor cells for this case, where blast cells were small, poorly differentiated, with a fine chromatin, without vacuoles or pseudopodia-shaped cytoplasmic expansions.

Immunophenotypic characterization of CD4+CD56+ tumor cells

Immunophenotypic features of malignant cells are summarized in Table 3. Among the markers expressed by CD4+CD56+ tumor cells, CD45 was present at a low level in all 19 patients tested, CD68 was found to be positive in 92% of tested patients (11 of 12), HLA DR in 91% (21 of 23), and CD36 in 85% (18 of 21). Other markers frequently expressed by tumor cells were CD38 (74%), CD71 (72%), and CD7 (61%). CD2 was detected in 2 of 23 (9%) patients. Thirteen patients were additionally tested for the expression of CD116 (GM-CSFR), CD123 (IL-3R), and CD45 RA (Table 4). These patients homogeneously coexpressed CD123 and CD45 RA in the absence or with only low levels of CD116.

Immunophenotypic characteristics of the patients

| Patient no. . | CD2 . | CD4 . | CD7 . | CD8 . | CD16 . | CD34 . | CD36 . | CD38 . | CD45 . | CD56 . | CD57 . | CD68 . | CD71 . | CD117 . | HLA DR . | TdT . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | W | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| 2 | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | W | + | − | + | − | + | − | |

| 3 | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | W | + | − | + | − | + | − | |

| 4 | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | |

| 5 | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | W | + | − | − | + | |||

| 6 | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | W | + | − | + | − | + | −† | |

| 7 | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | W | + | − | + | − | + | −† | |

| 8 | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | W | + | − | + | − | + | −† | |

| 9 | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | ||||

| 10 | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | W | + | − | + | + | − | + | |

| 11* | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | W | + | − | + | + | − | + | |

| 12 | − | + (W) | + | − | − | − | + | + | W | + | − | + | − | + | + | |

| 13* | − | + | + | − | − | + | W | + | − | + | + | |||||

| 14 | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | W | + | − | − | + | |||

| 15 | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | W | + | − | + | − | − | + | |

| 16 | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | W | + | − | − | − | + | |||

| 17 | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | W | + | − | − | + | − | ||

| 18 | − | + | − | + (W) | − | − | − | W | + | − | − | − | + | − | ||

| 19 | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | + | |||||||

| 20 | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | |||||

| 21 | − | + | + (W) | − | − | − | + | + (W) | W | + | − | + | + | − | + | |

| 22* | − | + | + (W) | − | − | − | − | + (W) | W | + | − | − | + | − | − | |

| 23 | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | W | + | − | + | − | + | |||

| Frequencies | 2/23 | 23/23 | 14/23 | 1/23 | 0/21 | 0/23 | 18/21 | 14/19 | 19/19 | 23/23 | 0/22 | 11/12 | 8/11 | 0/21 | 21/23 | 1/10 |

| 9% | 100% | 61% | 4% | 0% | 0% | 85% | 74% | 100% | 100% | 0% | 92% | 72% | 0% | 91% | 10% |

| Patient no. . | CD2 . | CD4 . | CD7 . | CD8 . | CD16 . | CD34 . | CD36 . | CD38 . | CD45 . | CD56 . | CD57 . | CD68 . | CD71 . | CD117 . | HLA DR . | TdT . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | W | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| 2 | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | W | + | − | + | − | + | − | |

| 3 | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | W | + | − | + | − | + | − | |

| 4 | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | |

| 5 | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | W | + | − | − | + | |||

| 6 | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | W | + | − | + | − | + | −† | |

| 7 | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | W | + | − | + | − | + | −† | |

| 8 | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | W | + | − | + | − | + | −† | |

| 9 | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | ||||

| 10 | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | W | + | − | + | + | − | + | |

| 11* | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | W | + | − | + | + | − | + | |

| 12 | − | + (W) | + | − | − | − | + | + | W | + | − | + | − | + | + | |

| 13* | − | + | + | − | − | + | W | + | − | + | + | |||||

| 14 | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | W | + | − | − | + | |||

| 15 | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | W | + | − | + | − | − | + | |

| 16 | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | W | + | − | − | − | + | |||

| 17 | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | W | + | − | − | + | − | ||

| 18 | − | + | − | + (W) | − | − | − | W | + | − | − | − | + | − | ||

| 19 | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | + | |||||||

| 20 | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | |||||

| 21 | − | + | + (W) | − | − | − | + | + (W) | W | + | − | + | + | − | + | |

| 22* | − | + | + (W) | − | − | − | − | + (W) | W | + | − | − | + | − | − | |

| 23 | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | W | + | − | + | − | + | |||

| Frequencies | 2/23 | 23/23 | 14/23 | 1/23 | 0/21 | 0/23 | 18/21 | 14/19 | 19/19 | 23/23 | 0/22 | 11/12 | 8/11 | 0/21 | 21/23 | 1/10 |

| 9% | 100% | 61% | 4% | 0% | 0% | 85% | 74% | 100% | 100% | 0% | 92% | 72% | 0% | 91% | 10% |

W indicates weak.

Immunophenotypic data obtained during secondary medullary dissemination.

TdT expression analyzed by RT-PCR.

Expression of CD116, CD123 and CD45RA on CD4+CD56+ tumor cells

| Patient no. . | CD116 . | CD123 . | CD45 RA . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | W | + | + |

| 3 | W | + | + |

| 6 | − | + | + |

| 7 | − | + | + |

| 8 | − | + | + |

| 10 | − | + | + |

| 113-150 | W | + | + |

| 133-150 | − | + | ND |

| 14 | W | + | + |

| 16 | W | + | + |

| 18 | − | + | + |

| 21 | W | + | + |

| 223-150 | − | + | + |

| 23 | W | + | + |

| Frequencies | 7W/14 | 14/14 | 13/13 |

| 50% | 100% | 100% |

| Patient no. . | CD116 . | CD123 . | CD45 RA . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | W | + | + |

| 3 | W | + | + |

| 6 | − | + | + |

| 7 | − | + | + |

| 8 | − | + | + |

| 10 | − | + | + |

| 113-150 | W | + | + |

| 133-150 | − | + | ND |

| 14 | W | + | + |

| 16 | W | + | + |

| 18 | − | + | + |

| 21 | W | + | + |

| 223-150 | − | + | + |

| 23 | W | + | + |

| Frequencies | 7W/14 | 14/14 | 13/13 |

| 50% | 100% | 100% |

W indicates weak.

Immunophenotypic data obtained during secondary medullary dissemination.

Blast cells from patient 18 expressed CD8 and TdT was also present only in patient 12, both markers frequently found to be expressed on tumor cells of a lymphoid origin.

Therapeutic response

All patients but 2 received polychemotherapy (Table 1). All but one of the treated patients received an anthracycline/anthracenedione-based protocol or cyclophosphamide/ifosfamide (Endoxan/Holoxan) or both (n = 15). These therapeutic protocols also included vincristine (Oncovin)/VP16 (n = 14) or cytarabine (Aracytine) (n = 6). Prednisone was also given to 11 patients. Three patients (9, 22, and 23) received an allogeneic bone marrow transplant in the course of the first complete remission. Median follow-up was 15 months (range, 2-96 months). Whatever the type of polychemotherapy administered, 18 of 21 (86%) patients achieved complete remission. Two of 21 (9%) patients achieved partial response. No response was observed for patient 16.

To date, 15 of 18 (83%) patients who achieved complete remission have had a relapse (Table 1). The median time of relapse was 9 months (range, 3-18 months). Bone marrow involvement was found in 73% of the patients at relapse (Table 5). It is noteworthy that the 3 patients with isolated cutaneous lesions at diagnosis had a relapse in the bone marrow within 6 months. If present at diagnosis, skin lesions were also systematically observed at relapse. Five patients (33%; patients 6, 8, 15, 21, and 22) had a relapse in the CNS. Other sites of relapse were lymph nodes, spleen, and the gums. A leukemic phase was noted at relapse for 3 patients. Among patients treated by polychemotherapy, overall survival was 52% (10 of 19) after 1-year of follow-up and 25% (4 of 16) after 24 months of follow-up. Among the 3 patients who benefited from allogeneic bone marrow transplantation, patients 9 and 23 were still in complete remission after 60 months of follow-up.

Sites of first relapse

| Patient no. . | Bone marrow . | Skin . | CNS . | Other . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | + | + | ||

| 4 | + | |||

| 5 | + | |||

| 6 | + | |||

| 7 | + | |||

| 8 | + | + | + | + |

| 10 | + | + | ||

| 11 | + | |||

| 13 | + | + | ||

| 15 | + | |||

| 17 | + | |||

| 19 | + | |||

| 20 | + | + | ||

| 21 | + | + | + | + |

| 22 | + | + | + | + |

| Frequencies | 11/15 | 6/14 | 5/15 | 6/15 |

| 73% | 43% | 33% | 40% |

| Patient no. . | Bone marrow . | Skin . | CNS . | Other . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | + | + | ||

| 4 | + | |||

| 5 | + | |||

| 6 | + | |||

| 7 | + | |||

| 8 | + | + | + | + |

| 10 | + | + | ||

| 11 | + | |||

| 13 | + | + | ||

| 15 | + | |||

| 17 | + | |||

| 19 | + | |||

| 20 | + | + | ||

| 21 | + | + | + | + |

| 22 | + | + | + | + |

| Frequencies | 11/15 | 6/14 | 5/15 | 6/15 |

| 73% | 43% | 33% | 40% |

“Other” was lymph nodes for patient 7, gingiva for patient 8, spleen for patients 13 and 20, peripheral blood for patients 8, 21, and 22.

Discussion

CD4+CD56+ malignancies were first postulated to be NK cell lymphomas/leukemias on the basis of CD56 expression.1-3 In a recent study, Petrella et al6 have described this entity as a CD4+CD56+ hematopoietic neoplasm of unknown origin. To better define this entity in terms of clinical and biologic features, the GEIL group conducted a study based on the selection of patients on immunophenotypic criteria. Recently, DC2/plasmacytoid DCs have been identified as the counterpart of CD4+CD56+ malignant cells.9 In this study, we describe data on 23 patients with such malignancies.

The most significant features of CD4+CD56+tumors can be described from this comprehensive series of patients, allowing the diagnosis of such malignancies. The majority of patients were older adults, but the disease may occur in younger adults or in children. At diagnosis, most patients had cutaneous nodules that had appeared a few weeks to a few months previously. Surface body examination often showed disseminated purple lesions of the dermis. The health status was good, with no systemic symptoms. Lymphadenopathy or spleen enlargement or both were frequent. Cytopenia was common, although leukocytosis was noted in a few patients. Peripheral malignant cells were often detected. Bone marrow involvement was usually observed, with a high percentage of malignant cells. When not initially detected, bone marrow infiltration occurred rapidly in the course of the disease. Morphologic and cytochemical analysis revealed a high frequency of vacuolation with pseudopodialike cytoplasmic expansions. MPO and monocytic esterase activity were never detected. Beyond the immunophenotypic criteria for patient selection, tumor cells exhibited a homogeneous immunophenotype including both positive and negative markers corresponding to a neoplasm of a CD36+, CD68+, and HLA DR+ bone marrow hematopoietic precursors with low expression of CD45 and lack of CD34, CD117, CD14, CD15, CD16, CD57, and MPO antigen. Most patients also expressed CD7, CD38, and CD71. Finally, cytogenetic analysis of these malignancies showed a complex karyotype in most instances with recurrent cytogenetic events, such as complete or partial deletion of the 5q arm, deletion of chromosome 13, 6q abnormalities, deletion of 12p region, deletion of chromosome 9 and 15.41

The evolution of CD4+CD56+ malignancies was rapidly fatal when polychemotherapy was impossible. Whatever the polychemotherapy protocol applied, complete remission was obtained easily for all but 2 patients. However, relapse has been a highly frequent event in our large series and the prognosis was poor at 24 months. Two major clinical and therapeutic features emerge from this series. First, among these 23 patients with CD4+CD56+ malignancies, one had an initial CNS localization and 5 had relapses in the CNS. These clinical data clearly indicate that the CNS could be a persistent blast cell sanctuary, suggesting that systematic preventive intrathecal chemotherapy could be indicated in this disease in addition to intensive polychemotherapy. Second, only patient 9 (a child) and patient 22 (a young adult) are still in complete remission after 60 months of follow-up and are probably cured of their disease. These patients have both undergone polychemotherapy followed by allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in the course of the first complete remission. This could correspond in part to an antileukemic effect of allogeneic cells (for a review, see Dansey and Baynes12). Such intensive therapeutic protocols may not be possible in older adults. Novel therapeutic perspectives may be possible considering the potential interest in nonablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation, which can be now used for patients aged 60 to 65 years.12 Therefore, from this series of CD4+CD56+ malignancies with bone marrow dissemination, it is possible to suggest a therapeutic strategy that may be able to cure the patient, which would consist of an intensive polychemotherapy protocol applied for acute lymphoblastic leukemia with poor prognosis associated with intrathecal chemotherapy and followed by allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in the course of the first complete remission.

CD4+CD56+ tumor cells shared some features with blast cells of acute leukemia. Indeed, the levels of CD45 expression on CD4+CD56+ blast cells were always low, corresponding to those expected for acute leukemia blast cells.13 The fact that some cases may be secondary to myelodysplastic syndromes is also consistent with this proposal. The morphology of CD4+CD56+ blast cells evokes that of acute leukemia blast cells for most cases with a lacy chromatin and prominent nucleoli. Even though cutaneous nodules appear to be the major clinical symptom of this disease, bone marrow involvement was almost always present. As in the chloroma of acute monoblastic leukemia,14-16 bone marrow infiltration appeared clearly to be part of the natural history of the disease for patients without detectable bone marrow involvement at early diagnosis. In addition to cutaneous nodules, some patients had a clinical presentation immediately evocative of an acute leukemia with massive bone marrow involvement, major leucocytosis with circulating malignant cells. Some other clinical features such as CNS dissemination are shared by both acute lymphoblastic and monoblastic leukemia. These immunophenotypic, cytologic, and clinical features, together with data obtained by Chaperot et al,9 suggest that CD4+CD56+ malignancies correspond to a neoplasm of a bone marrow hematopoietic precursor committed to the DC2/plasmacytoid DC differentiation pathway. These elements, taken together, suggest that CD4+CD56+ malignancies are related to acute leukemia, that is, to a neoplasm of a bone marrow precursor.

It cannot be ruled out that our series could be biased due to the selection of patients having bone marrow dissemination of their disease. Indeed, more indolent forms of this disease without systemic dissemination would have been missed with the definition strategy we used. Cases of CD4+CD56+ malignancies reported in the literature interestingly were also characterized by cutaneous nodules with lymphadenopathy, spleen enlargement, frequent cytopenia, or bone marrow infiltration.1-3,6,17-19 CD68 expression by CD4+CD56+ tumor cells has also been previously reported.2,3,6 The series published by Petrella et al describes 7 cases, identifying del(5q) as a recurrent cytogenetic event.6 These chromosomal anomalies have equally been reported occasionally in the other series.1-3 Cytogenetic analysis of this series confirms these recurrent cytogenetic events.41 However, it is still unclear whether CD4+CD56+ malignancies with bone marrow dissemination and pure cutaneous CD4+CD56+malignancies with indolent clinical presentation are at opposite ends of the spectrum of the same disease or correspond to 2 different entities with different natural history and clinical or biologic behavior.

Until recently, the origin of CD4+CD56+malignant cells has remained uncertain. In fact, CD4+CD56+ cells specifically express both CD45 RA and CD123 (IL-3R α chain) and do not express CD116 (GM-CSFR). These immunophenotypic characteristics have been discussed in detail by Chaperot et al9 with regard to the immunophenotype of DC2/plasmacytoid DCs. The origin of DC2/plasmacytoid DCs remains elusive and CD4+CD56+ malignancies do not express markers allowing to clearly ascribe them to a myeloid or a lymphoid origin with certainty. However, both myeloid and DC2/plasmacytoid DCs derive at least from a common hematopoietic precursor in the bone marrow.20 21

Considering this series of 23 patients, some elements argue in favor of a myeloid origin of CD4+CD56+ malignant cells. CD36 and CD68 expression was observed in most tested cases. Both markers are reported to be present on cells belonging to the myeloid lineage. From this point of view, it should be noted that, even though it was absent at diagnosis, the myeloid marker CD33 was observed in 2 patients (10 and 13) at relapse. Expression of CD33 was also induced after in vitro culture of CD4+CD56+ malignant cells.9 Five patients exhibited significant features of MDS with a predominance of dysgranulopoiesis, including both hypogranulated and pseudo Pelger-Huet cells. Among these 5 patients, 2 had a history of MDS. Acute leukemia secondary to transformation of MDS very often is of the myeloid lineage. Comparison between the morphology of blast cells at the time of MDS diagnosis and that of cells recognized to correspond to CD4+CD56+ malignant cells was not conclusive for these patients. No immunophenotypic data were available on blast cells at the time of MDS diagnosis either. The karyotype was normal for these 2 patients at the time of both MDS and CD4+CD56+ malignancy diagnosis. Therefore, it is not possible to conclude whether CD4+CD56+malignancies arose coincidentally in some older patients with pre-existing MDS or could correspond to MDS transformation. However, it is interesting to recall that DC2/plasmacytoid DCs were initially termed “plasmacytoid T cells” or “plasmocytoid monocytes”22 and that the evolution of a “plasmacytoid T-cell lymphoma” in acute myeloid leukemia as well as an association with or transformation of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia in “plasmacytoid T-cell lymphoma” have been reported by Muller-Hermelink et al in 1983,23 and Beiske et al in 198624 as well as by Facchetti et al in 1990.25 These tumors were CD4+, did not express either B or T surface lineage markers, might express such myeloid lineage markers as CD68, and had T-cell receptor (TCR) loci in germline configuration,26,27 and the question of the myelomonocytic origin of these cells was clearly raised.28

Identification of DC2/plasmacytoid DCs as the physiologic counterpart of CD4+CD56+ malignant cells could also suggest a lymphoid origin because such cells have been ascribed to the lymphoid lineage in both mice and humans.29,30 The expression of λpre-B and pre-TCRα chains was found for both DC2/plasmacytoid DCs and CD4+C56+ malignant cells by Chaperot et al9 and support a lymphoid origin of these cells. TdT, usually expressed in acute lymphoblastic leukemia, was only tested for a minority of our patients, and was found positive in one patient.12 However, TdT is a weak lymphoid marker according to the EGIL classification of acute leukemia11and TdT may be expressed in some cases of acute myeloid leukemia.31-33 Among this series of 23 patients, a single patient was found to express CD8. This raises also the question of the lymphoid origin of tumor cells in this case because DC2/plasmacytoid DCs isolated from mice express CD8.34 In fact, a recent report suggests that, in mice, both myeloid DCs (CD8α−) and lymphoid DCs (CD8α+) could derive from a common hematopoietic lymphoid CD4low precursor able to reconstitute T-cell, DC1, and DC2 lineage but unable to reconstitute the myeloid lineage.35 However, the analysis of mice deficient for Notch1 or for both c-kit and the common cytokine receptor γ chain revealed that T-cell and lymphoid DC differentiation pathways may be dissociated.36,37 Even if the hypothesis of a lymphoid origin of these cells is favored, this could also suggest the existence of independent nonlymphoid nonmyeloid hematopoietic DC precursors, as discussed by Martin et al35 and Banchereau et al.38 Therefore, considering the origin of DC2/plasmacytoid DCs leads to the hypothesis that CD4+CD56+ malignancies may correspond to a neoplasm of a nonmyeloid nonlymphoid hematopoietic precursor, explaining why neither a lymphoid nor a myeloid origin could be ascribed to these tumor cells.6

In CD4+CD56+ malignancies, cutaneous localization of the disease is a frequent event. This raises the question of the cutaneous tropism of CD4+CD56+blast cells. The CD56 molecule is an isoform of the neural cell adhesion molecule expressed on myeloid blast cells, NK cells, and myeloma plasma cell, for example, is involved in cell-cell interactions and could be involved in homing.39 Normal DC2/plasmacytoid DCs are expected in secondary lymphoid organs, and so far were not detected in the skin. DC2/plasmacytoid DCs cells do not express the CD56 molecule. CD56 expression has been reported to be associated with the extramedullary dissemination of acute myeloid leukemias.40 These data raise the question of the functional role of CD56 on DC2/plasmacytoid blast cells in relation to the original pattern of extramedullary dissemination.

We would like to thank Pr L. Laroche (Hôpital Avicenne, Bobigny, France); Drs N. Vey and R. Bouabdallah (Institut Paoli Calmettes, Marseille, France); Dr N. Atkhen (Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou, Paris, France); Dr G. Chedeveille (Hôpital Necker, Paris, France); Drs F. Girodon, F. Mugneret, G. Couillault, S. Dalac, T. Petrella, P. Pfitzenmeyer, and B. Salles (CHU Bocage, Dijon, France); Drs T. Lamy and C. Dauriac (Hôpital Pontchaillou, Rennes, France); Pr C. Berthou (CHU de Brest, Brest, France); Dr H. Orfeuvre (CHR Bourg en Bresse); Dr B. Corront and Dr Bizet (CHR Annecy) for helpful clinical advice. We are grateful to Dr Veronique Deneys (Laboratoire d'Immuno-Hématologie, Bruxelles, Belgique), Dr P. Darodes de Tailly (EFS Besançon, France), Pr M. Imbert and Dr H. Jouault (Laboratoire d'Hématologie, Hôpital Henri Mondor, Créteil, France), and Pr H. Merle-Béral (Laboratoire d'Hématologie, Hôpital Pitié Salpétrière, Paris, France) for submitting cases.

Supported in part by a grant from ARC number 9951 and 5729 to the Groupe d'Etude Immunologique des Leucémies.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Marie-Christine Béné, Groupe d'Etude Immunologique des Leucémies (GEIL), Laboratoire d'Immunologie du CHU, Faculté de Médecine, BP 184, 54 400 Vandoeuvre Les Nancy, France; e-mail: bene@grip.u-nancy.fr; or Jean Feuillard, Service d'Hématologie Biologique et EA ATHSCO, Hôpital Avicenne et Université Paris 13, 125 route de Stalingrad, 93009 Bobigny CEDEX, France; e-mail: jean.feuillard@avc.ap-hop-paris.fr.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal