Abstract

M-tropic human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) strains enter the cell after interaction with their receptors, CD4 and the G-protein–coupled chemokine receptor CCR5. The number of cell surface CCR5 molecules is thought to be important in determining the infection rate for HIV. Cell surface CCR5 is dependent on the rate of receptor internalization and recycling. Internalization of G-protein–coupled receptors after agonist activation is thought to occur either through clathrin-coated pits or through caveolae. In this study, the role of these different pathways was investigated in Chinese hamster ovary cells expressing CCR5 using specific inhibitors. Internalization of CCR5 after chemokine treatment was inhibited by sucrose, indicating a role for the clathrin-coated pit pathway. Activation of CCR5 leads to arrestin-2 movement in the cells, providing further evidence for the involvement of clathrin-coated pits. Nystatin and filipin also affected the rate of internalization of CCR5, indicating a role for caveolae. Using inhibitors of vesicle transport in the cell, it was found that the CCR5 recycling pathway is independent of the Golgi apparatus and late endosomes. Protein synthesis is not involved in receptor recovery. It seems likely that after internalization, CCR5 is directed to early endosomes and subsequently recycled to the cell surface.

Introduction

Chemokine receptor CCR5 is a member of the large family of G-protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) containing 7 membrane-spanning α-helices. CCR5 has been identified as the receptor for the chemokines macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α, MIP-1β, RANTES, MCP-1, MCP-2, MCP-3, MCP-4, and eotaxin.1 CCR5 also serves as a coreceptor for the entry of M-tropic human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) strains into cells.2-5 Binding of viral gp120 to CD4 leads to a conformational change in gp120, which results in binding to CCR5 and finally to viral entry into the cells.6 The number of coreceptors (CCR5) expressed on the cell surface is an important factor for virus infection of cells. Patients with a reduced number of CCR5 expressed on the cell surface, caused by a mutation in theCCR5 gene that leads to a truncated receptor not expressed on the cell surface, seem to have a degree of immunity against HIV-1 infection.7,8 In addition, a naturally high expression level of certain chemokines, such as MIP1-α and MIP-1β, leads to a lower CCR5 level and a higher immunity against HIV-1 infection.9 10

The mechanism by which the receptor number is regulated on the cell surface, however, is unclear. Receptor number on the cell surface is a balance between the rate of internalization and the rate of replacement (recycling and new synthesis). There are 2 major routes whereby GPCRs can be internalized after ligand binding. The first involves binding of arrestin to the receptor, which results in a movement of the receptor to clathrin-coated pits and internalization. The second pathway involves caveolae and is independent of clathrin-coated pits. The pathway dependent on clathrin-coated pits is still the best-known entry system into cells11 and may be considered a default system for degradation and recycling. Binding of arrestin-2 to the phosphorylated receptor in turn initiates the internalization process by binding to clathrin. Then the receptor–arrrestin-2 complex is sequestered in clathrin-coated pits. By the action of dynamin, the clathrin-coated pits are pinched off to become clathrin-coated vesicles. Rab5- and rab7-dependent vesicle fusion processes are involved in trafficking of the vesicles from early endosomes to late endosomes to lysosomes.12-14

Caveolae are microdomains in the plasma membrane approximately 50 to 100 nm across. They are involved in several crucial cellular functions such as endocytosis, photocytosis, transcytosis, calcium signaling, and cholesterol transport. Biochemical studies have revealed the complex molecular composition of caveolae.15 Caveolin, an integral membrane protein (21-24 kd),16,17 and the distinct lipid composition of the caveolae (enrichment of cholesterol, sphingolipids, and glycolipids but the lack of phospholipids)18,19 are the main molecular features of caveolae. Caveolae are capable of being internalized in a regulated manner or under well-defined conditions. Cholesterol is required for the maintenance of caveolae integrity and function.20

Although the rate of internalization of a receptor is an important factor in determining its level at the cell surface, the rate of recycling and the rate of synthesis of new receptors are also important. Some of the mechanisms of the recycling process are understood. Internalized receptors are thought to have several potential fates. One fate is dephosphorylation of the receptor in endosomes followed by recycling back to the plasma membrane. Sequentially, the receptors pass through late endosomes and the Golgi and finally are transported back to the cell surface. Another fate is that internalized receptors are degraded, which may result in receptor down-regulation. Protein synthesis has not been shown to play a role in receptor recycling.

Constituent mechanisms involved in these pathways can be inhibited specifically by different chemicals. Formation of clathrin-coated pits can be inhibited using 0.4 M sucrose or chlorpromazine,20whereas the caveolae pathway is sensitive to filipin and nystatin treatment.20 Filipin flattens the caveolae, inhibits the entry of cholera toxin, and releases several proteins of the cortical cytoskeleton, such as annexin II, alpha-actinin, ezrin, moesin, and membrane-associated actin.21 Brefeldin A inhibits vesicle formation at the level of the Golgi apparatus, resulting in the disruption of the traffic between the Golgi and the endoplasmic reticulum,22 without impairing endosomal or lysosomal function.23,24 Monensin blocks Golgi transport and prevents the acidification of intracellular compartments and, therefore, the recycling of receptors.25 Nocodazole inhibits microtubule polymerization and, therefore, the transport of endocytosed ligands from early to late endosomes.26

In this study we used these inhibitors to investigate the pathways that are involved during CCR5 internalization. Work with the inhibitors has been supported by confocal microscope studies of CCR5. We also investigated which compartments in the cells are involved during the recovery of the receptor and whether protein synthesis is involved.

Materials and methods

Cells and materials

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were transfected with pcDNA3 encoding CCR5 and selected for stable expression in 10% fetal calf serum (FCS)–Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM)–glutamine (2 mM) in the presence of G418. CHO.CCR5 cells were transfected with pREP.CD4 and were selected for the expression of CD4 and CCR5 in 10% FCS–DMEM–glutamine (2 mM) in the presence of hygromycin and G418. HeLa RC49 cells were obtained from D. Kabat and described previously.27 Chemokines were purchased from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ) or MRC Aids Reagent Repository Programme (Potters Bar, United Kingdom). Secondary antibodies were obtained from Sigma (Poole, United Kingdom), Serotec (Oxford, United Kingdom) or Harlan Sera-Lab (Loughborough, United Kingdom). Anti-CD4 antibody ARP318 was from the MRC Aids Reagent Repository Programme. Anti-CCR5 antibodies HEK/1/85a/7a and 1/74/3j were raised against intact CHO.CCR5 cells and the CCR5 N-terminal peptide, respectively, and were deposited in the MRC Aids Reagent Repository Programme. The plasmid p enhanced green fluorescent protein (pEGFP)–arrestin-2 was constructed as described previously.28 All other chemicals were from Sigma.

Chemicals

Nystatin, filipin, chlorpromazine, sucrose, and nocodazole were purchased from Sigma. Cycloheximide was from ICN (Basingstoke, United Kingdom). Cells were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C with chlorpromazine (25 μg/mL), filipin (5 μg/mL), brefeldin A (5 μM), monensin (50 μM), sucrose (0.4 M), or nystatin (50 μg/mL) before an internalization assay was performed. Alternatively, monensin or brefeldin A was added to the cells during the recovery phase of the receptor. Cycloheximide (10 μg/mL) was added during the recovery phase on the cells as indicated. When pretreating cells with nocodazole (30 μM), the incubation was performed for 1 hour on ice or at 37°C as indicated.

Internalization assay and flow cytometry analysis

HeLa RC49, CHO.CCR5, and CHO.CCR5.CD4 cells were incubated with serum-free medium for 2 hours at 37°C harvested with 2 mM EDTA–phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then resuspended in medium without serum at 5 × 106 cells/mL. Cells were then incubated with chemokines (50 nM) for various times at 37°C, and washed in ice-cold PBS or PBS containing 1% FCS and 1% NaN3 for fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis. Cell surface-expressed CCR5 was detected by flow cytometry using anti-CCR5 antibody HEK/1/85a/7a and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated anti–rat IgG. Cells were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with HEK/1/85a/7a (saturating amounts of hybridoma supernatant), washed 3 times with PBS buffer containing 1% FCS and 1% NaN3, and incubated for 1 h with FITC-labeled anti–rat IgG. Samples were quantified on a FACScan, and data were analyzed with CellQuest software version 3.1 (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Relative CCR5 surface expression was calculated as 100× [mean channel of fluorescence (stimulated) − mean channel of fluorescence (negative control)/mean channel of fluorescence (medium) − mean channel of fluorescence (negative control)] (%). CHO cells not expressing CCR5 and irrelevant monoclonal antibodies were used for negative controls with similar results. Cell surface expressed CD4 was detected in the same way, using the anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody ARP318 (5 μg per stain) and a corresponding secondary FITC-labeled antibody.

Recycling of receptor

Internalization was initiated as described. After 1-hour incubation with chemokines, the cells were washed 3 times in medium without FCS and resuspended in medium without FCS at 37°C. Samples were taken at different time points, and cells were washed in PBS buffer containing 1% FCS and 1% NaN3. Cells were stained with antibodies as described.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were grown on coverslips and incubated in medium without serum for 2 hours before treatment with chemokines for 1 hour. Cells were then washed with medium and incubated with the CCR5 antibody (HEK/1/85a/7a) for 1 hour at 37°C. After washing, the cells were incubated with the corresponding secondary FITC-labeled antibody for 1 hour, washed and fixed in ice-cold methanol, and mounted on glass slides. Images were taken using a Leica NT Confocal Imaging system. CHO.CCR5 or CHO.CCR5.CD4 cells were transiently transfected with pEGFP–arrestin-2 using LipofectAMINE (Invitrogen). Cells were treated with chemokines 48 hours after transfection and were stained with the CCR5 antibody and the corresponding secondary Rhodamine-labeled antibody.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Statistical analysis was performed using Studentt test (P < .05). Internalization data represent the means of at least 3 independent experiments.

Results

Cell surface expression of CCR5

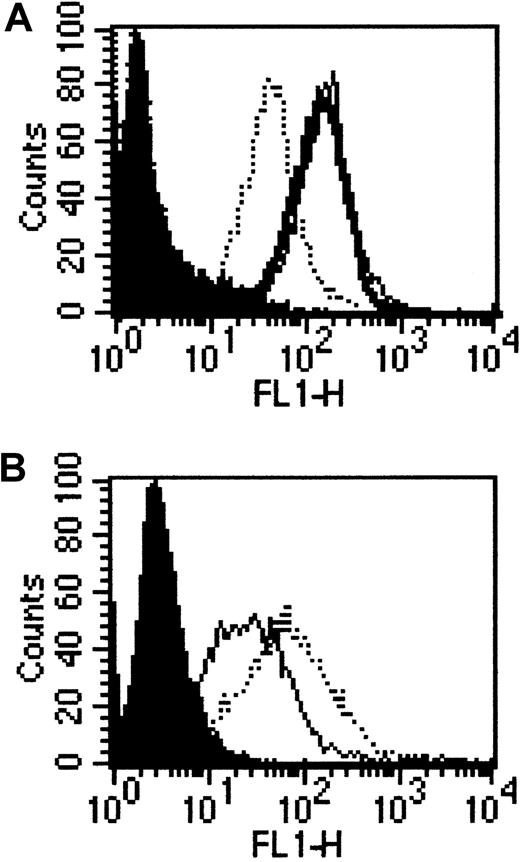

To investigate pathways of internalization of CCR5, we used 3 different cell lines: CHO cells that either expressed solely CCR5 (CHO.CCR5) or coexpressed CCR5 and CD4 (CHO.CCR5.CD4). We also used a HeLa cell line that expressed stably CCR5 and CD4.27 Cell surface expression of the receptor was determined using FACS analysis, and this showed comparable CCR5 expression levels of CHO.CCR5 and HeLa RC49, whereas the CHO.CCR5.CD4 cells expressed CCR5 at a much lower level (Figure 1A). CD4 expression levels on HeLa RC49 and CHO.CCR5.CD4 were similar (Figure 1B).

Expression of CCR5 and CD4 on CHO.CCR5, CHO.CCR5.CD4, and HeLa RC49 cells.

Expression was determined using FACS analysis as described in “Materials and methods.” (A) FACS analysis for the expression of CCR5. Black, negative control; bold line, CHO.CCR5 cells; dotted line, CHO.CCR5.CD4 cells; thin line, HeLa RC49. (B) FACS analysis for expression of CD4. Black, negative control; dotted line, CHO.CCR5.CD4 cells; thin line, HeLa RC49.

Expression of CCR5 and CD4 on CHO.CCR5, CHO.CCR5.CD4, and HeLa RC49 cells.

Expression was determined using FACS analysis as described in “Materials and methods.” (A) FACS analysis for the expression of CCR5. Black, negative control; bold line, CHO.CCR5 cells; dotted line, CHO.CCR5.CD4 cells; thin line, HeLa RC49. (B) FACS analysis for expression of CD4. Black, negative control; dotted line, CHO.CCR5.CD4 cells; thin line, HeLa RC49.

Inhibition of internalization

Cells were pretreated with 0.4 M sucrose for 1 hour at 37°C in medium without FCS, and then an internalization assay was performed with 3 different chemokines (50 nM) for 1 hour. Sucrose treatment inhibited MIP-1α–induced internalization in all 3 cell lines tested. A significant inhibition of RANTES-induced and MIP-1β–induced internalization by sucrose was observed in CHO.CCR5.CD4 cells (Table1). Treatment with 25 μg/mL chlorpromazine for 1 hour gave results similar to those seen with sucrose (data not shown).

Effect of sucrose on clathrin-coated pit-dependent internalization

| Cells . | Chemokine . | Control . | Sucrose . |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHO.CCR5 | MIP-1α | 50.8 ± 3.2 (6) | 101.4 ± 14.7 (6)* |

| RANTES | 54.4 ± 3.1 (5) | 79.7 ± 17.5 (6) | |

| MIP-1β | 85.6 ± 3.7 (6) | 99.0 ± 5.2 (3) | |

| CHO.CCR5.CD4 | MIP-1α | 48.6 ± 3.6 (7) | 76.9 ± 3.9 (6)† |

| RANTES | 59.6 ± 4.8 (8) | 69.5 ± 3.5 (8)† | |

| MIP-1β | 42.2 ± 10.9 (5) | 94.8 ± 4.5 (9)‡ | |

| HeLaRC49 | MIP-1α | 58.6 ± 4.9 (6) | 97.9 ± 6.1 (6)† |

| Cells . | Chemokine . | Control . | Sucrose . |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHO.CCR5 | MIP-1α | 50.8 ± 3.2 (6) | 101.4 ± 14.7 (6)* |

| RANTES | 54.4 ± 3.1 (5) | 79.7 ± 17.5 (6) | |

| MIP-1β | 85.6 ± 3.7 (6) | 99.0 ± 5.2 (3) | |

| CHO.CCR5.CD4 | MIP-1α | 48.6 ± 3.6 (7) | 76.9 ± 3.9 (6)† |

| RANTES | 59.6 ± 4.8 (8) | 69.5 ± 3.5 (8)† | |

| MIP-1β | 42.2 ± 10.9 (5) | 94.8 ± 4.5 (9)‡ | |

| HeLaRC49 | MIP-1α | 58.6 ± 4.9 (6) | 97.9 ± 6.1 (6)† |

Cells were treated with internalization inhibitor sucrose, as described, before internalization was induced with MIP-1α, RANTES, or MIP-1β, respectively. Cells that were not treated with inhibitor served as control for internalization. Data represent mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments.

P < .01, relative to control.

P < .001, relative to control.

P < .05, relative to control.

We then pretreated the cells with nystatin (50 μg/mL) and filipin (5 μg/mL) for 1 hour and performed an internalization assay as described (Table 2). Nystatin inhibited the MIP-1α–induced internalization in CHO.CCR5 and CHO.CCR5.CD4 cells. Internalization attributed to RANTES was inhibited by nystatin in CHO.CCR5 and CHO.CCR5.CD4 cells, whereas MIP-1β–induced internalization was only significantly inhibited in CHO.CCR5.CD4 cells. Filipin treatment inhibited internalization to a lesser degree. In CHO.CCR5 cells the inhibition was significant only with MIP-1α treatment, whereas in CHO.CCR5.CD4 cells the internalization from all 3 tested chemokines was significantly inhibited by filipin.

Effect of nystatin and filipin on caveolae-dependent internalization

| Cells . | Chemokine . | Control . | Inhibitor . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filipin . | Nystatin . | |||

| CHO.CCR5 | MIP-1α | 50.8 ± 3.2 (6) | 64.5 ± 4.5 (5)* | 97.2 ± 8.8 (6)† |

| RANTES | 54.4 ± 3.1 (5) | 63.9 ± 4.3 (6) | 84.0 ± 4.2 (6)† | |

| MIP-1β | 85.6 ± 3.7 (6) | 95.0 ± 3.6 (3) | 91.0 ± 4.6 (3) | |

| CHO.CCR5.CD4 | MIP-1α | 48.6 ± 3.6 (7) | 111.2 ± 2.4 (4)† | 70.8 ± 3.7 (5)‡ |

| RANTES | 59.6 ± 4.8 (8) | 77.4 ± 3.2 (8)† | 77.7 ± 4.9 (8)‡ | |

| MIP-1β | 42.2 ± 10.9 (5) | 98.5 ± 6.1 (9)‡ | 92.7 ± 6.9 (9)‡ | |

| Cells . | Chemokine . | Control . | Inhibitor . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filipin . | Nystatin . | |||

| CHO.CCR5 | MIP-1α | 50.8 ± 3.2 (6) | 64.5 ± 4.5 (5)* | 97.2 ± 8.8 (6)† |

| RANTES | 54.4 ± 3.1 (5) | 63.9 ± 4.3 (6) | 84.0 ± 4.2 (6)† | |

| MIP-1β | 85.6 ± 3.7 (6) | 95.0 ± 3.6 (3) | 91.0 ± 4.6 (3) | |

| CHO.CCR5.CD4 | MIP-1α | 48.6 ± 3.6 (7) | 111.2 ± 2.4 (4)† | 70.8 ± 3.7 (5)‡ |

| RANTES | 59.6 ± 4.8 (8) | 77.4 ± 3.2 (8)† | 77.7 ± 4.9 (8)‡ | |

| MIP-1β | 42.2 ± 10.9 (5) | 98.5 ± 6.1 (9)‡ | 92.7 ± 6.9 (9)‡ | |

Cells were treated with the inhibitors nystatin and filipin, as described, before internalization was induced with MIP-1α, RANTES, or MIP-1β, respectively. Cells that were not treated with inhibitor served as control for internalization. Data represent mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments.

P < .05, relative to control.

P < .001, relative to control.

P < .01, relative to control.

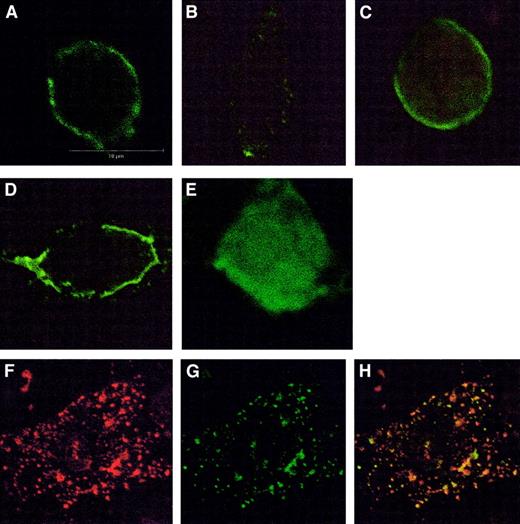

Effects of these inhibitors were also examined using confocal microscopy (Figure 2). In control cells CCR5 was localized to the plasma membrane, but after treatment with chemokine CCR5 was seen to move to a vesicular compartment in the cytosol. Sucrose, nystatin, and filipin prevented this movement in CHO.CCR5 and CHO.CCR5.CD4 cells, in agreement with the data outlined above. The role of arrestin-2 was examined by transient transfection of pEGFP–arrestin-2 in CHO.CCR5 or CHO.CCR5.CD4 cells. This showed that chemokine-induced activation of CCR5 leads to the redistribution of arrestin-2 in cells, resulting in a colocalization of arrestin-2 and CCR5 (Figure 2).

Immunofluorescence detection of CCR5 using confocal microscopy.

(A-D) Effects of inhibitors on CCR5 internalization in CHO.CCR5 cells. (A) Untreated cells, stained with anti-CCR5 antibody. (B) Cells treated with MIP-1α. (C) Cells pretreated with sucrose. (D) Cells pretreated with nystatin; cells were grown on coverslips for 24 hours and then treated with inhibitors and chemokine as described in “Materials and methods.” Similar results were obtained for filipin or in CHO.CCR5.CD4 cells (data not shown). (E-H) Effects of CCR5 activation on arrestin-2 movement in CHO.CCR5 cells. (E) Untreated cells transfected with pEGFP–arrestin-2. (F-H) Cells treated with MIP-1α as described and then stained with anti-CCR5 antibody and rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody. (F) CCR5 (red). (G) pEGFP–arrestin-2 (green). (H) Overlay arrestin-2 and CCR5.

Immunofluorescence detection of CCR5 using confocal microscopy.

(A-D) Effects of inhibitors on CCR5 internalization in CHO.CCR5 cells. (A) Untreated cells, stained with anti-CCR5 antibody. (B) Cells treated with MIP-1α. (C) Cells pretreated with sucrose. (D) Cells pretreated with nystatin; cells were grown on coverslips for 24 hours and then treated with inhibitors and chemokine as described in “Materials and methods.” Similar results were obtained for filipin or in CHO.CCR5.CD4 cells (data not shown). (E-H) Effects of CCR5 activation on arrestin-2 movement in CHO.CCR5 cells. (E) Untreated cells transfected with pEGFP–arrestin-2. (F-H) Cells treated with MIP-1α as described and then stained with anti-CCR5 antibody and rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody. (F) CCR5 (red). (G) pEGFP–arrestin-2 (green). (H) Overlay arrestin-2 and CCR5.

Effects of these inhibitors of membrane trafficking on the binding of chemokines to the receptor and the function of the receptor was assessed using a [35S]GTPγS binding assay.29 MIP-1α stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding to membranes of CHO.CCR5 cells was not affected by sucrose, nystatin, or filipin (data not shown), indicating that these inhibitors do not affect chemokine binding or activation of CCR5. Chlorpromazine interfered with the basal signal in the assay; hence, effects on chemokine activation could not be determined.

Recovery of the receptor

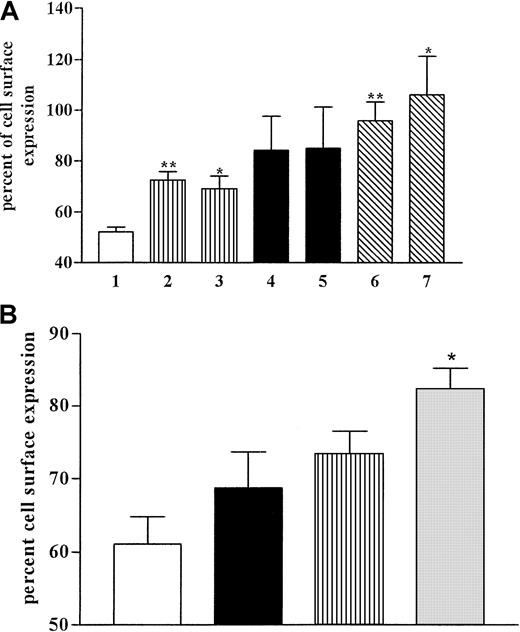

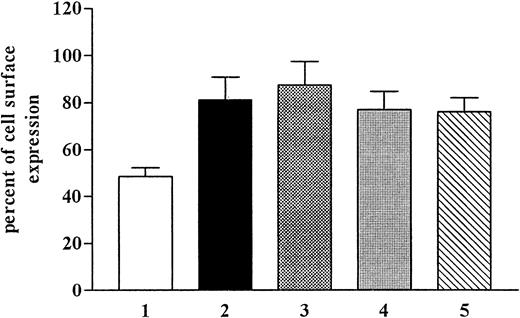

Recovery of the receptor to the cell surface was investigated after the internalization of CCR5 triggered by MIP-1α in CHO.CCR5 and HeLa RC49 cells (Figure 3). After 1-hour incubation with the chemokine at 37°C, cells were washed in medium and incubated at 37°C for the times indicated. In some experiments, protein synthesis in the cells was inhibited with cycloheximide (10 μg/mL) added during the recovery phase. After 120 minutes, most receptors on the cell surfaces returned to control levels in both cell systems used (Figure 3). In CHO.CCR5 cells we did not observe any effects of cycloheximide on the recovery rate (Figure 3). It seemed unlikely that protein synthesis was involved in receptor recovery. We concluded that CCR5 recovery was solely caused by receptor recycling.

CCR5 recovery after internalization and effects of cycloheximide.

(A) CHO.CCR5 cells. Internalization was induced with MIP-1α as described. After 1 hour cells were washed and incubated in medium at 37°C. When indicated, cycloheximide (10 μg/mL) was added during the recovery phase. At given time points, samples were taken and subjected to FACS stain. 1, control (MIP-1α; 2, 45 minutes; 3, 45 minutes (plus cycloheximide); 4, 90 minutes; 5, 90 minutes (plus cycloheximide); 6, 120 minutes; 7, 120 minutes (plus cycloheximide). (B) HeLa RC49 cells. Experimental set-up was as for panel A. ■, control; ▪, 75 minutes; ▥, 90 minutes; ░, 120 minutes. Data represent means ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments. **P < .01; *P < .05, relative to control (MIP-1α).

CCR5 recovery after internalization and effects of cycloheximide.

(A) CHO.CCR5 cells. Internalization was induced with MIP-1α as described. After 1 hour cells were washed and incubated in medium at 37°C. When indicated, cycloheximide (10 μg/mL) was added during the recovery phase. At given time points, samples were taken and subjected to FACS stain. 1, control (MIP-1α; 2, 45 minutes; 3, 45 minutes (plus cycloheximide); 4, 90 minutes; 5, 90 minutes (plus cycloheximide); 6, 120 minutes; 7, 120 minutes (plus cycloheximide). (B) HeLa RC49 cells. Experimental set-up was as for panel A. ■, control; ▪, 75 minutes; ▥, 90 minutes; ░, 120 minutes. Data represent means ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments. **P < .01; *P < .05, relative to control (MIP-1α).

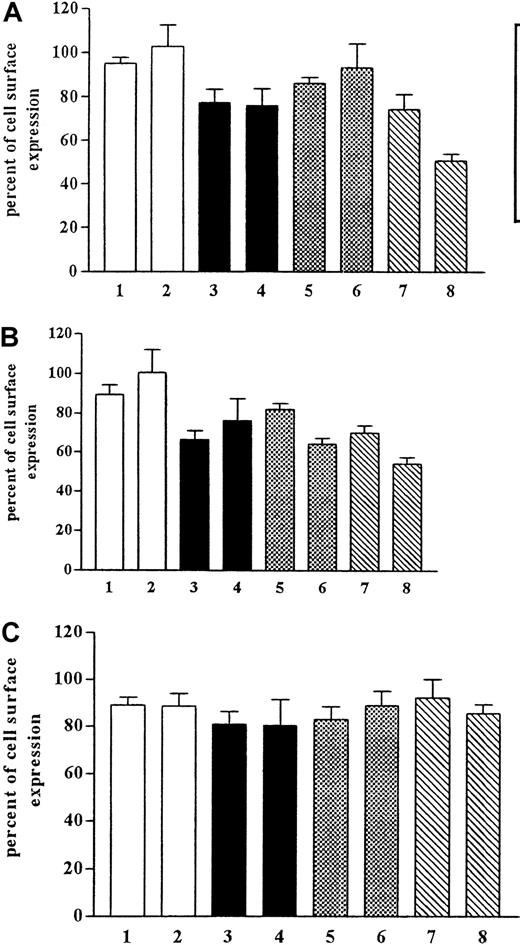

Internalization is only one determinant of the number of the cell surface receptors. Equally important is whether receptor recycling is taking place simultaneously with internalization and whether this recycling rate is influencing the internalization of the receptor. We pretreated the cells with monensin and brefeldin A (Figure4), which have been shown to inhibit the function of the Golgi apparatus and, therefore, to inhibit recycling. After pretreatment with monensin (50 μM), we observed the inhibition of internalization but no effect on recycling. Monensin has been shown to inhibit internalization by way of coated pits. Brefeldin A (5 μM) pretreatment of the cells had no significant effect on the internalization rate.

Effects of monensin and brefeldin A on recovery of CCR5.

CHO.CCR5 cells were pretreated for 1 hour with monensin or brefeldin A or both before internalization was induced. After 30 minutes and 60 minutes, respectively, cells were stained for FACS analysis. (A) MIP-1α. (B) RANTES. (C) MIP-1β. 1, monensin, 30 minutes; 2, monensin, 1 hour; 3, brefeldin A, 30 minutes; 4, brefeldin A, 1 hour; 5, monensin plus brefeldin A, 30 minutes; 6, monensin plus brefeldin A, 1 hour; 7, control, 30 minutes; 8, control, 60 minutes. Data represent mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments.

Effects of monensin and brefeldin A on recovery of CCR5.

CHO.CCR5 cells were pretreated for 1 hour with monensin or brefeldin A or both before internalization was induced. After 30 minutes and 60 minutes, respectively, cells were stained for FACS analysis. (A) MIP-1α. (B) RANTES. (C) MIP-1β. 1, monensin, 30 minutes; 2, monensin, 1 hour; 3, brefeldin A, 30 minutes; 4, brefeldin A, 1 hour; 5, monensin plus brefeldin A, 30 minutes; 6, monensin plus brefeldin A, 1 hour; 7, control, 30 minutes; 8, control, 60 minutes. Data represent mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments.

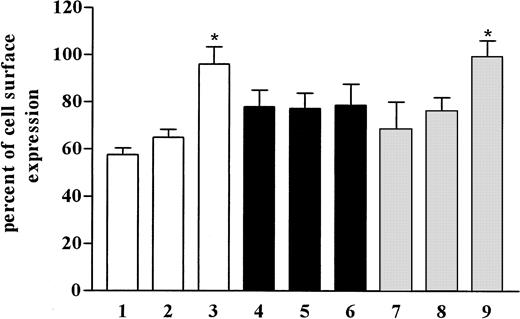

These experiments did not allow determination of the recycling rate of CCR5 receptor. Internalization was initiated as before, and the cells were incubated for recovery, as described, in the presence or absence of monensin and brefeldin A (Figure 5). This experiment should allow normal internalization, and the chemicals used should only influence the recovery phase. Because we were unable to observe an effect of monensin or brefeldin A on the recycling rate of CCR5 (Figure 5), we concluded that recycling of CCR5 is independent of the Golgi apparatus in the cells and that acidification of intracellular compartments is not necessary for receptor recycling.

Effects of monensin and brefeldin A on recovery of CCR5.

Internalization was initiated in CHO.CCR5 cells with MIP-1α, as described, and cells were washed and incubated in medium in the presence or absence of monensin and brefeldin A for 120 minutes. Cells were then subjected to FACS analysis. 1, control; 2, 120 minutes; 3, monensin, 120 minutes; 4, brefeldin A, 120 minutes; 5, brefeldin A plus monensin, 120 minutes. Data represent mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments.

Effects of monensin and brefeldin A on recovery of CCR5.

Internalization was initiated in CHO.CCR5 cells with MIP-1α, as described, and cells were washed and incubated in medium in the presence or absence of monensin and brefeldin A for 120 minutes. Cells were then subjected to FACS analysis. 1, control; 2, 120 minutes; 3, monensin, 120 minutes; 4, brefeldin A, 120 minutes; 5, brefeldin A plus monensin, 120 minutes. Data represent mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments.

These experiments showed that neither new synthesis of CCR5 nor transport through the Golgi apparatus of the cell is involved in the recycling phase. We treated the cells with nocodazole to investigate earlier transport mechanisms in the cell. Treatment of cells with nocodazole should inhibit transport of vesicles from early to late endosomes. Pretreatment of cells with nocodazole at 37°C did not have any effect on the recycling rate (Figure6). Nevertheless, when the cells were pretreated with nocodazole at 4°C, the recycling rate was diminished. In the same experiment we found that internalization was inhibited, and it seemed likely that incubation on ice disrupted the cell machinery leading to a reduction in the recovery rate.

Effects of nocodazole on receptor recovery in CHO.CCR5 cells.

Cells were pretreated with nocodazole either on ice or at 37°C as indicated for 1 hour, and internalization was initiated with MIP-1α for 1 hour. Cells were washed and incubated at 37°C for the time points indicated. Nocodazole was also added during the recovery phase. ■, control; ▪, nocodazole on ice; ░, nocodazole, 37°C; 1,4,7, control; 2,5,8, 60 minutes; 3,6,9, 120 minutes. Data represent mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments. *P < .05, relative to control.

Effects of nocodazole on receptor recovery in CHO.CCR5 cells.

Cells were pretreated with nocodazole either on ice or at 37°C as indicated for 1 hour, and internalization was initiated with MIP-1α for 1 hour. Cells were washed and incubated at 37°C for the time points indicated. Nocodazole was also added during the recovery phase. ■, control; ▪, nocodazole on ice; ░, nocodazole, 37°C; 1,4,7, control; 2,5,8, 60 minutes; 3,6,9, 120 minutes. Data represent mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments. *P < .05, relative to control.

Discussion

In this study we have examined the mechanisms that regulate the number of chemokine receptor CCR5 on cells and the effects of chemokines on these. We show that CCR5 internalization after chemokine treatment can occur through pathways involving clathrin-coated pits or caveolae. We also show that recycling of internalized CCR5 is independent of protein synthesis and depends on early endosomes.

It has been well established that the chemokine receptor CCR5 acts as a coreceptor for HIV-12 and that the levels of CCR5 on cells influence the rate of entry of HIV-1. Hence, patients with reduced or nonexistent levels of CCR5 on peripheral blood mononuclear cells exhibit immunity against HIV-1 infection.7,8 In addition, high expression of MIP-1α and MIP-1β in the blood provides some protection against HIV-1 infection.10 It seems that MIP-1α and MIP-1β are able to induce CCR5 internalization, thus reducing the entry of HIV-1.1 CCR5 levels on cells are a critical factor in the entry of HIV-1 and subsequent infection. It is important to understand in detail the mechanisms governing the level of CCR5 on cells.

Two pathways have been described for the internalization of G-protein–coupled receptors, such as CCR5, after their activation. One pathway uses clathrin-coated pits.11 Activated receptor is phosphorylated and binds to arrestin proteins, and the complex is transported to clathrin-coated pits. Here it is internalized in vesicles and transported to endosomes where dephosphorylation takes place. The receptor is then recycled back to the cell surface. Some receptors are not recycled but may be transported from endosomes to lysosomes or proteasomes, and then they are degraded.12-14A second pathway of internalization depends on caveolae. Caveolae are highly organized membrane structures that have been shown to be involved in the internalization of several GPCRs.

To investigate which pathways are involved in CCR5 internalization and recycling, we used 3 different cell lines expressing CCR5. Two CHO cell lines expressing CCR5 alone (CHO.CCR5) or with CD4 (CHO.CCR5.CD4) have been used. CCR5 is expressed at a higher level in CHO.CCR5 cells than in the CHO.CCR5.CD4 cells. Additionally, we used a HeLa cell line (RC49) that expresses CCR5 and CD4; levels of CCR5 were comparable to those in CHO.CCR5 cells.

First, we investigated the role of the 2 pathways of internalization using selective inhibitors, and similar results were seen in each of the 3 cell lines. Internalization of CCR5 from MIP-1α or RANTES was inhibited by 0.4 M sucrose. This treatment is known to inhibit GPCR internalization through clathrin-coated pits.20Internalization from MIP-1β was not inhibited in CHO.CCR5 cells, but this may reflect the fact that MIP-1β–induced internalization in these CCR5 cells is low. These data were confirmed using confocal microscopy (Figure 2), where sucrose treatment inhibited the movement of CCR5 away from the plasma membrane. Activation of CCR5 also leads to redistribution of arrestin-2 in the cells, leading to colocalization of CCR5 and arrestin-2 (Figure 2E-H). These observations provide further evidence for the involvement of clathrin-coated pits in CCR5 internalization. Similar data were obtained with chlorpromazine, which is also known to inhibit internalization by coated pits, but in this case we were unable to eliminate the possibility of effects of chlorpromazine on chemokine–receptor interaction (see above).

CCR5 was also affected by inhibitors of caveolae-dependent internalization pathways. In CHO.CCR5 cells, treatment with nystatin (50 μg/mL) inhibited MIP-1α and RANTES-induced internalization, whereas filipin (5 μg/mL) only inhibited MIP-1α internalization. In contrast in CHO.CCR5.CD4 cells, nystatin and filipin inhibited internalization induced by all 3 chemokines tested. These data were confirmed by confocal microscopy in which the chemokine-induced movement of CCR5 away from the plasma membrane was inhibited by these agents. From these results, it seems that caveolae may also be involved in CCR5 internalization, but there are some quantitative differences in the effects of the inhibitors in different cell lines. There are indeed some differences in the properties of the CHO cell lines expressing CCR5 used for this work. CHO.CCR5.CD4 cells exhibited a different morphology than CHO.CCR5 cells, with the former cells being more rounded and less spread out than CHO.CCR5 cells. This could be attributed to differences in the properties of the membrane in the 2 cell lines. Indeed, we were able to detect different expression levels of caveolin-1 or clathrin in these 2 cell lines. CHO.CCR5 expressed less clathrin than CHO.CCR5.CD4 but more caveolin-1 than CHO.CCR5.CD4 (data not shown), though both proteins were expressed in both cell lines. The different relative expression levels of clathrin and caveolin-1 may be indicative of differences in the properties of the membranes in the 2 cell lines and may affect the internalization mechanisms of the receptor.

Next, we investigated recovery mechanisms for CCR5 after internalization. Recovery experiments in CHO.CCR5 and HeLa RC49 cells showed that after 120 minutes' incubation, the level of receptor on the cell surface was back to nearly 100%. In CHO.CCR5 cells, we could not observe any effect of cycloheximide treatment on the recovery rate, so protein synthesis was unlikely to be involved in CCR5 recovery in these cells. Receptor recycling is thought to use several steps in the cell machinery. Receptors are transported to early and late endosomes, where dephosphorylation and resensitization takes place before recycling. To examine these processes, we used monensin treatment to inhibit the acidification of intracellular compartments and brefeldin A to block the translocation of protein from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi. After pretreatment of the cells with these compounds, however, we could not observe any MIP-1α–induced internalization of CCR5 in CHO.CCR5 cells. Monensin has been shown to inhibit pathways dependent on clathrin-coated pits and probably blocked internalization because of MIP-1α. The effects of brefeldin A are less clear because there are no reports that brefeldin A inhibits internalization pathways.

The experimental protocol was changed to circumvent these problems. Chemokine-induced internalization was performed in cells in the absence of inhibitors, and during the recovery phase brefeldin A or monensin was added to the cells. Using this experimental protocol, we did not observe any significant influence of monensin or brefeldin A on the recovery rate of CCR5. It seems likely that CCR5 is recycled back to the cell surface without passing through the Golgi apparatus in the cells.

Nocodazole has been described as an inhibitor of the transport of vesicles between early and late endosomes. We tested the effects of this substance on CCR5 recycling by pretreating cells. There was no effect of nocodazole on CCR5 recovery after internalization. It seems unlikely that late endosomes are involved in the recovery of the receptor. While this work was nearing completion, a study was published30 that showed that CCR5 was internalized to endosomal vesicles with properties similar to those described for recycling endosomes. These data, obtained with different techniques, are in full agreement with those in the current study.

Based on the current observations, the mechanism of CCR5 internalization and recycling seems to involve clathrin-coated pits and caveolae. After internalization, CCR5 is transported to early endosomes and recycled back to the cell surface. There is no evidence for the involvement of late endosomes, Golgi apparatus, or protein synthesis.

We thank Dr Jane McKeating for her involvement in the inception of the project and for generating cell lines and antibodies. We thank Dr Christine Shotton for monoclonal antibodies to CCR5 and Dr Lloyd Czaplewski (British Biotech) for various chemokine reagents. We thank the Centralized Facility for AIDS Reagents, supported by EU Programme EVA (contract BMH4 97/2515) and the United Kingdom Medical Research Council. We also thank Dr David Kabat for the HeLa RC49 cell line.

Supported by a project grant from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Philip G. Strange, School of Animal and Microbial Sciences, University of Reading, PO Box 228, Reading, RG6 6AJ, United Kingdom; e-mail: p.g.strange@rdg.ac.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal