The B-cell lymphoproliferative malignancies B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) share characteristics, including overlapping chromosomal aberrations with deletions on chromosome bands 13q14, 11q23, 17p13, and 6q21 and gains on chromosome bands 3q26, 12q13, and 8q24. To elucidate the biochemical processes involved in the pathogenesis of B-CLL and MCL, we analyzed the expression level of a set of genes that play central roles in apoptotic or cell proliferation pathways and of candidate genes from frequently altered genomic regions, namely ATM, BAX, BCL2, CCND1, CCND3, CDK2,CDK4, CDKN1A, CDKN1B,E2F1, ETV5, MYC, RB1,SELL, TFDP2, TNFSF10, andTP53. Performing real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction in a panel of patients with MCL and B-CLL and control samples, significant overexpression and underexpression was observed for most of these genes. Statistical analysis of the expression data revealed the combination of CCND1 and CDK4 as the best classifier concerning separation of both lymphoma types. Overexpression in these malignancies suggests ETV5 as a new candidate for a pathogenic factor in B-cell lymphomas. Characteristic deregulation of multiple genes analyzed in this study could be combined in a comprehensive picture of 2 distinctive pathomechanisms in B-CLL and MCL. In B-CLL, the expression parameters are in strong favor of protection of the malignant cells from apoptosis but did not provide evidence for promoting cell cycle. In contrast, in MCL the impairment of apoptosis induction seems to play a minor role, whereas most expression data indicate an enhancement of cell proliferation.

Introduction

B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) are B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) of low and intermediate grades, respectively. Both diseases are types of follicle mantle-derived lymphoproliferative malignancies. B-CLL is the most common leukemia in adults of the Western world and is associated with the accumulation of immuno-incompetent B-lymphocytes with low proliferative activity. These noncycling lymphocytes escape from the induction of programmed cell death.1-5 A highly variable clinical course with a median survival time of 7 to 10 years is characteristic for B-CLL.6 In contrast, patients with MCL have a median survival of 3 years,7 and MCL is characterized by the (11;14)(q31;q32) translocation resulting in the up-regulation of cyclin D1 (CCND1) by the immunoglobulin heavy-chain enhancer elements.8 9

Both malignancies are characterized by common chromosomal aberrations. Although MCL is associated with higher complexity of the karyotype, there are striking similarities between common genetic aberrations in MCL and B-CLL: deletions on chromosome bands 13q14, 11q23, 17p13, and 6q21 and gains on chromosome bands 3q26, 12q13, and 8q24.10-15 For some chromosomal loci, the affected genes are identified, such as TP53 on 17p1316,17 andATM (ataxia telangiectasia mutated) on 11q23.18-21 However, the molecular mechanisms causing B-CLL and MCL are still unknown. To determine to which degree cell cycle progression or impairment of apoptosis induction plays a role in the pathomechanisms of these neoplasias, we performed a quantitative expression study of genes whose products have a central function in both processes. Little is known with regard to quantitative expression of the respective genes. Quantitative studies in MCL revealed overexpression of cyclin D122,23 andMYC.24 In B-CLL faint expression of CD95 (TNFSF6) and CD95-R (TNFRSF6),5,25overexpression of BCL2, steady-state expression ofTP53, and decreased expression of BAX in progressive disease were reported.26

To obtain a comprehensive view of the activated or deregulated factors and pathways with oncogenic potential, we analyzed a series of MCL and B-CLL samples for expression of the following genes, which were selected based on their localization in altered genomic regions or on the function of their products in cell cycle and apoptosis control:ATM, BAX, BCL2, CCND1, cyclin D3 (CCND3), CDK2, CDK4, p21 (CDKN1A), p27 (CDKN1B), E2F1,ETV5, MYC, RB1, L-selectin (SELL), DP2 (TFDP2), TRAIL (TNFSF10), and TP53. Using the real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RQ-PCR) technique,27 we identified genes that are overexpressed or underexpressed in B-CLL and MCL, some of which were previously not known to be altered in these diseases. The potential impact of our results on the elucidation of the pathways that contribute to the pathomechanisms and clinical behavior of B-CLL and MCL is discussed in detail.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patients

The study comprised samples from 62 patients with B-CLL and 16 patients with MCL diagnosed according to established morphologic and immunophenotypical criteria6,7 and samples from 14 control subjects obtained after informed consent. In general, characteristic morphology and immunophenotype (B-CLL, CD5+CD19+CD23+; MCL, CD5+CD19+CD23−) were required for the diagnosis, and variations were observed only in a minority of patients (in MCL, CD5−, n = 2; CD23+, n = 2). In patients with atypical features, the disease classification was based on best available evidence, including lymph node biopsy specimen if clinically feasible. In addition, the translocation t(11;14)(q13;q32) was present in all cases of MCL except one (highlighted by an asterisk in the figures and legends) and in none of the cases of B-CLL, as detected by our previously reported interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization assay.28CD38 was expressed in more than 30% of cells in 7 of 16 B-CLL patients studied. Patient age ranged from 37 to 86 years (median, 61 years) in B-CLL and from 51 to 83 years (median, 67 years) in MCL. The sex ratio was (male-to-female) 2.05 in B-CLL and 2.2 in MCL. Thirty-one percent of patients with MCL and 34.1% of patients with B-CLL underwent chemotherapy before the study. However, all patients had active disease, and no chemotherapy had been administered for at least 3 months. Staging information was incomplete in 16 of the 62 B-CLL patients; 16 were Binet stage A, 18 stage B, and 12 stage C. Of the mantle cell lymphomas, 15 were stage IV, and in one patient staging information was incomplete. To reduce the variation of gene expression caused by experimental methods, peripheral blood was the preferred tumor cell source for both entities (13 of 16 MCL; 57 of 62 B-CLL) based on 2 considerations. The first was that the expression profile of the tumor cells might have reflected the in vivo microenvironment from which the cells are derived, and the second was that the artificial expression profile changes caused by differences in cell manipulation might have been reduced. The use of blood as a tumor cell source resulted in a selection bias toward leukemic MCL patients but allowed for a high tumor cell content of the preparations documented by immunophenotypic and genetic criteria. Genomic aberrations in addition to the t(11;14) were present in all MCL patients and were detected in 67% to 97% (median, 86%) of cells with a disease-specific probe set.15 Control samples for B-cell neoplasias are never ideal because it is not understood how much a given phenotype—for example, CD5 positivity—is representative of the original cell pool from which the tumor cells developed or is characteristic of the neoplastic transformation. In agreement with current knowledge, we therefore chose the CD19+fractions as control samples, which were purified using MACS CD19 MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) from buffy coat preparations that were obtained randomly from our blood bank. Age distribution of the donors was 18 to 68 years, with a male-to-female ratio of 1:3. Each gene was analyzed in 19 to 34 B-CLL, 6 to 15 MCL, and 5 to 10 control samples.

Sample and RNA preparation

The human chronic B-cell leukemia cell line EHEB29(DSMZ no. ACC67) was cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin. Mononuclear cell fractions from B-CLL and MCL patients and control samples were obtained through Ficoll density-gradient centrifugation. Total RNA was extracted using the TRIZOL reagent (Gibco BRL, Eggenstein, Germany). To avoid contamination by genomic DNA, 2 μg total RNA was subjected to a DNAse I digestion (5 U; Roche, Mannheim, Germany) in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 75 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM dithiothreitol for 10 minutes at 25°C and 10 minutes at 37°C. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using the GeneAmp Kit with random hexamer primers (RNA PCR System; PE Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany) at a concentration of 18.75 mM Tris-HCl and 0.25 mM dithiothreitol.

Real-time quantitative reverse-transcription PCR

Each cDNA sample was analyzed in triplicate (aliquot of 1 μL each) using the ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detector (PE Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany). Quantitative assessment of DNA amplification was detected either through the TaqMan probes, which are specific for the targeted gene, or through the dye SYBR Green. The TaqMan probe containing 2 dyes, a reporter and a quencher dye, fluoresces on removal of the quencher by the 5′-3′ exonuclease activity of the Taq polymerase during PCR, and SYBR Green fluoresces on binding to dsDNA. The RQ-PCR reactions were carried out in a total volume of 50 μL according to the manufacturer's manuals for SYBR Green PCR Core Reagents and TaqMan Universal Master Mix (PE Applied Biosystems). The primer and TaqMan probe concentration were 300 nM and 200 nM, respectively.

For thermal cycling, the following conditions were applied: 2 initial incubations of 2 minutes at 50°C and 10 minutes at 95°C, then 40 cycles of 15 seconds at 95°C and 1 minute at 60°C. For SYBR Green PCR reactions, these settings were extended with an initial step of 30 minutes at 37°C and 3 final steps of 15 seconds at 95°C, 15 seconds at 60°C, and 15 seconds at 95°C. The heating rate (ramping) between the last 2 steps was increased to 20 minutes to obtain a melting curve of the final RQ-PCR products (ABI Prism Dissociation Curve Software, PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). This is necessary because SYBR Green fluorescence may also be derived from side products such as primer-dimers.

Oligonucleotides used for RQ-PCR are listed in Table1. TaqMan probes were labeled by a 5′ FAM reporter and a 3′ TAMRA quencher, except for the 5′ VIC-labeled reporter in the TaqMan PreDevelopedAssayReagents (PDAR, PE Applied Biosystems), which were used as control amplicons to normalize the template. Primers and TaqMan probes were all designed using Primer Express software (PE Applied Biosystems).

Sequences of primers and TaqMan probes

| Primer designation . | Sequence (5′-3′) . |

|---|---|

| ATM forward | TGGATCCAGCTATTTGGTTTGA |

| ATM reverse | CCAAGTATGTAACCAACAATAGAAGAAGTAG |

| BAX forward | CCTTTTCTACTTTGCCAGCAAAC |

| BAX reverse | GAGGCCGTCCCAACCAC |

| BCL2 forward | GGCTGGGATGCCTTTGTG |

| BCL2 reverse | GCCAGGAGAAATCAAACAGAGG |

| CCND1 forward | CTGGAGGTCTGCGAGGAACA |

| CCND1 TaqMan probe | AGGTCTTCCCGCTGGCCATGAACTAC |

| CCND1 reverse | TTTTTCACGGGCTCCAGC |

| CCND3 forward | GCCCTCTGTGCTACAGATTATACCT |

| CCND3 reverse | TGCTGCCCGTGGCG |

| CDK2 forward | GCTAGCAGACTTTGGACTAGCCAG |

| CDK2 reverse | AGCTCGGTACCACAGGGTCA |

| CDK4 forward | ATGTTGTCCGGCTGATGGA |

| CDK4 reverse | CACCAGGGTTACCTTGATCTCC |

| CDKN1A forward | CGCTAATGGCGGGCTG |

| CDKN1A reverse | CGGTGACAAAGTCGAAGTTCC |

| CDKN1B forward | CTGCAACCGACGATTCTTCTACT |

| CDKN1B reverse | GGGCGTCTGCTCCACAGA |

| E2F1 forward | AGATGGTTATGGTGATCAAAGCC |

| E2F1 reverse | ATCTGAAAGTTCTCCGAAGAGTCC |

| ETV5 forward | GCGGCCTGTGATTGACAGA |

| ETV5 reverse | GGAACTTGTGCTTCAGCTAACCA |

| LMNB1 forward | GATTGCCCAGTTGGAAGCCT |

| LMNB1 reverse | TGGTCTCGTTAATCTCCTCTTCATACA |

| MYC forward | TGCCAGGACCCGCTTCT |

| MYC TaqMan probe | CAGCTGCTTAGACGCTGGATTTTTTTCG |

| MYC reverse | GAGGCTGCTGGTTTTCCACTA |

| PGK1 forward | AAGTGAAGCTCGGAAAGCTTCTAT |

| PGK1 reverse | AGGGAAAAGATGCTTCTGGG |

| RB1 forward | CTTGCATGGCTCTCAGATTCAC |

| RB1 TaqMan probe | ATTAAACAATCAAAGGACCGAGAAGGACCAACTG |

| RB1 reverse | AGAGGACAAGCAGATTCAAGGTG |

| SELL forward | TCACGTCGTCTTCTGTATACTGTGG |

| SELL reverse | TTGCAGCTAGCATTTCAGTGATG |

| TFDP2 forward | TCAGGCAAATGCTCTCTGGAG |

| TFDP2 reverse | ACCAAGAAGGTCCTGTGGAGATAT |

| TNFSF10 forward | GAGCTGAAGCAGATGCAGGAC |

| TNFSF10 reverse | TGACGGAGTTGCCACTTGACT |

| TP53 forward | CCCTTCAGATCCGTGGGC |

| TP53 TaqMan probe | TCTGTCCCCCTTGCCGTCCCA |

| TP53 reverse | TGAGTTCCAAGGCCTCATTCA |

| Primer designation . | Sequence (5′-3′) . |

|---|---|

| ATM forward | TGGATCCAGCTATTTGGTTTGA |

| ATM reverse | CCAAGTATGTAACCAACAATAGAAGAAGTAG |

| BAX forward | CCTTTTCTACTTTGCCAGCAAAC |

| BAX reverse | GAGGCCGTCCCAACCAC |

| BCL2 forward | GGCTGGGATGCCTTTGTG |

| BCL2 reverse | GCCAGGAGAAATCAAACAGAGG |

| CCND1 forward | CTGGAGGTCTGCGAGGAACA |

| CCND1 TaqMan probe | AGGTCTTCCCGCTGGCCATGAACTAC |

| CCND1 reverse | TTTTTCACGGGCTCCAGC |

| CCND3 forward | GCCCTCTGTGCTACAGATTATACCT |

| CCND3 reverse | TGCTGCCCGTGGCG |

| CDK2 forward | GCTAGCAGACTTTGGACTAGCCAG |

| CDK2 reverse | AGCTCGGTACCACAGGGTCA |

| CDK4 forward | ATGTTGTCCGGCTGATGGA |

| CDK4 reverse | CACCAGGGTTACCTTGATCTCC |

| CDKN1A forward | CGCTAATGGCGGGCTG |

| CDKN1A reverse | CGGTGACAAAGTCGAAGTTCC |

| CDKN1B forward | CTGCAACCGACGATTCTTCTACT |

| CDKN1B reverse | GGGCGTCTGCTCCACAGA |

| E2F1 forward | AGATGGTTATGGTGATCAAAGCC |

| E2F1 reverse | ATCTGAAAGTTCTCCGAAGAGTCC |

| ETV5 forward | GCGGCCTGTGATTGACAGA |

| ETV5 reverse | GGAACTTGTGCTTCAGCTAACCA |

| LMNB1 forward | GATTGCCCAGTTGGAAGCCT |

| LMNB1 reverse | TGGTCTCGTTAATCTCCTCTTCATACA |

| MYC forward | TGCCAGGACCCGCTTCT |

| MYC TaqMan probe | CAGCTGCTTAGACGCTGGATTTTTTTCG |

| MYC reverse | GAGGCTGCTGGTTTTCCACTA |

| PGK1 forward | AAGTGAAGCTCGGAAAGCTTCTAT |

| PGK1 reverse | AGGGAAAAGATGCTTCTGGG |

| RB1 forward | CTTGCATGGCTCTCAGATTCAC |

| RB1 TaqMan probe | ATTAAACAATCAAAGGACCGAGAAGGACCAACTG |

| RB1 reverse | AGAGGACAAGCAGATTCAAGGTG |

| SELL forward | TCACGTCGTCTTCTGTATACTGTGG |

| SELL reverse | TTGCAGCTAGCATTTCAGTGATG |

| TFDP2 forward | TCAGGCAAATGCTCTCTGGAG |

| TFDP2 reverse | ACCAAGAAGGTCCTGTGGAGATAT |

| TNFSF10 forward | GAGCTGAAGCAGATGCAGGAC |

| TNFSF10 reverse | TGACGGAGTTGCCACTTGACT |

| TP53 forward | CCCTTCAGATCCGTGGGC |

| TP53 TaqMan probe | TCTGTCCCCCTTGCCGTCCCA |

| TP53 reverse | TGAGTTCCAAGGCCTCATTCA |

Data normalization

To obtain a calibration graph, cDNA from the B-CLL cell line EHEB was serially diluted 8 times in H2O at a ratio of 2:1 and was measured in every single RQ-PCR run. A single RQ-PCR run consisted of the analysis of one amplicon measured at the different dilutions, the patient and the control samples. The fluorescence threshold (Ct) value is equal to the cycle number when the fluorescence reaches a set threshold. The resultant calibration graph (Ct versus log unit of the standard template [UST], which is a virtual value for the amount of cDNA) correlates Ct values with the amount of template in the PCR reaction. This was performed for every amplicon separately. To standardize the amount of sample cDNA, 4 endogenous control amplicons were used: the housekeeping genes coding for phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (PGK1) and lamin b1 (LMNB1) (SYBR Green), cyclophilin A (PPIA), and hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl-transferase (HPRT1) (TaqMan; PDAR). The average value of all 4 amplicons served as calibrator for a first normalization. Thereafter, the patient data were normalized using the mean value of all control sample data yielding the relative expression of each gene. In the following equation, which summarizes the calculation process, logarithmic values are used; otherwise values between 1 and 0 would be mathematically underrepresented.

Equation for data normalization

Statistical data analysis

Two approaches were used to analyze the discrimination ability of the gene expression data: (1) using a measure of between-sample separation and (2) using a measure of within-sample homogeneity.

We applied cutoff analyses for each gene individually to discriminate controls from lymphoma samples using maximally selected χ2 statistics.30 The absolute values of the log-transformed normalized data were used to test for the existence of cutoff values in expression to discriminate patient from control samples by overexpression or underexpression. In case of a statistically significant result, the cutoff was estimated by the value corresponding to the maximum χ2 statistic, and a one-sided 99% confidence interval of the cut-off value was computed using 1000 bootstrap samples. The upper boundary of this confidence interval then defines limits for overexpression or underexpression on the log scale. By back-transformation into the scale of the original data, these limits describe a normal range of gene expression in control samples with respect to expression observed in tumors. For theCCND1 data, for example, the original values range from 0.2 to 712. The range of the log-transformed data are −2.25 to 9.48, and taking absolute values yields numbers between 0.02 and 9.48. The upper limit of the resultant one-sided 99% confidence interval of the cut-off value for these transformed data was 2.56. With 5.90 = 22.56 this number and its reciprocal value 0.17 ( = 1/5.90) were set as limits of a normal range ofCCDN1 expression to identify significant differential expression (Table 2). Always 2-sided tests were used. The result of a test was considered statistically significant if the P value of its corresponding test statistic was smaller than or equal to 1% (P ≤ .01). No further P value adjustment was performed to account for multiple testing.

Statistical data analyses using maximally selected χ2 square analysis and univariate CART analysis

| Gene . | Sample sizes . | Maximally selected χ2statistics* . | CART† . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C . | B . | M . | Corrected P . | Estimated normal range . | Decision regions . | Overall error rate . | |||

| C . | B . | M . | |||||||

| ATM | 5 | 29 | 14 | .25 | — | — | — | — | — |

| BCL2 | 6 | 26 | 12 | .01 | 0.38-2.61 | — | — | — | — |

| BAX | 6 | 24 | 12 | .11 | — | — | — | — | — |

| CCND1 | 9 | 31 | 15 | .01 | 0.17-5.9 | — | — | > 34.4 | 0.11 |

| CCND3 | 9 | 31 | 15 | .27 | — | — | — | < 0.23 | 0.33 |

| CDK2 | 6 | 21 | 13 | .05 | — | — | — | > 3.13 | 0.30 |

| CDK4 | 8 | 25 | 13 | < .001 | 0.38-2.65 | < 2.03 | 2.03-11.96 | > 11.96 | 0.15 |

| TP53 | 9 | 34 | 14 | < .001 | 0.53-1.89 | — | — | — | — |

| RB1 | 9 | 32 | 15 | .11 | — | — | — | — | — |

| CDKN1B | 8 | 19 | 10 | .006 | 0.42-2.37 | < 1.85 | > 2.39 | 1.85-2.39 | 0.24 |

| CDKN1A | 9 | 19 | 8 | .79 | — | — | — | — | — |

| MYC | 7 | 31 | 14 | .002 | 0.39-2.55 | — | — | — | — |

| SELL | 8 | 32 | 6 | .003 | 0.37-2.73 | — | — | — | — |

| E2F1 | 6 | 24 | 12 | .24 | — | — | — | > 3.83 | 0.24 |

| TFDP2 | 10 | 24 | 15 | .03 | — | — | — | — | — |

| ETV5 | 8 | 28 | 15 | < .001 | 0.09-10.9 | — | — | — | — |

| TNFSF10 | 6 | 26 | 11 | .13 | — | — | — | > 9.63 | 0.28 |

| Gene . | Sample sizes . | Maximally selected χ2statistics* . | CART† . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C . | B . | M . | Corrected P . | Estimated normal range . | Decision regions . | Overall error rate . | |||

| C . | B . | M . | |||||||

| ATM | 5 | 29 | 14 | .25 | — | — | — | — | — |

| BCL2 | 6 | 26 | 12 | .01 | 0.38-2.61 | — | — | — | — |

| BAX | 6 | 24 | 12 | .11 | — | — | — | — | — |

| CCND1 | 9 | 31 | 15 | .01 | 0.17-5.9 | — | — | > 34.4 | 0.11 |

| CCND3 | 9 | 31 | 15 | .27 | — | — | — | < 0.23 | 0.33 |

| CDK2 | 6 | 21 | 13 | .05 | — | — | — | > 3.13 | 0.30 |

| CDK4 | 8 | 25 | 13 | < .001 | 0.38-2.65 | < 2.03 | 2.03-11.96 | > 11.96 | 0.15 |

| TP53 | 9 | 34 | 14 | < .001 | 0.53-1.89 | — | — | — | — |

| RB1 | 9 | 32 | 15 | .11 | — | — | — | — | — |

| CDKN1B | 8 | 19 | 10 | .006 | 0.42-2.37 | < 1.85 | > 2.39 | 1.85-2.39 | 0.24 |

| CDKN1A | 9 | 19 | 8 | .79 | — | — | — | — | — |

| MYC | 7 | 31 | 14 | .002 | 0.39-2.55 | — | — | — | — |

| SELL | 8 | 32 | 6 | .003 | 0.37-2.73 | — | — | — | — |

| E2F1 | 6 | 24 | 12 | .24 | — | — | — | > 3.83 | 0.24 |

| TFDP2 | 10 | 24 | 15 | .03 | — | — | — | — | — |

| ETV5 | 8 | 28 | 15 | < .001 | 0.09-10.9 | — | — | — | — |

| TNFSF10 | 6 | 26 | 11 | .13 | — | — | — | > 9.63 | 0.28 |

Absolute values of the log-transformed normalized data were used to test for the existence of cutoff values in expression to discriminate tumor from control samples by overexpression or underexpression. If the corresponding corrected P value of the maximally selected χ2 statistic was smaller than or equal to .01 we assumed that a cutoff gene expression existed. In these cases the cutoff was estimated by the value corresponding to the maximum χ2 statistic, and a one-sided 99% confidence interval of the cutoff value was computed using 1000 bootstrap samples. The upper boundary of this confidence interval then defined limits for overexpression or underexpression on the log-scale. By back-transformation into the original data scale, these limits described a normal range for gene expression with respect to the observed gene expression in tumors.

For each gene, univariate CART analysis was performed resulting in decision trees used to discriminate the three samples—B-CLL, MCL, and control. We used the entropy index to grow the trees and the cross-validated misclassification rate to prune them. Overall error rates are presented, together with the decision regions of the trees. Error rates and regions are not shown if the tree could not be validated by 10-fold cross-validation.

C indicates control; B, B-CLL; and M, MCL.

In addition, we used the concept of Classification and Regression Trees (CART)31 to classify into the control and the 2 patient groups. The tree is built by recursive partitioning using entropy as a measure of within-node homogeneity. The tree was pruned using 10-fold cross-validation where the pruning criterion is the cross-validated error rate. CART was applied to the expression data of each gene individually and to the full set of genes simultaneously. The 2 genes identified as the most important ones for the 3-group classification in the joint analysis are displayed in a scatterplot describing the partition for the data induced by these genes. All statistical analyses were performed using the software package S-Plus (Insightful, Seattle, WA).

Results

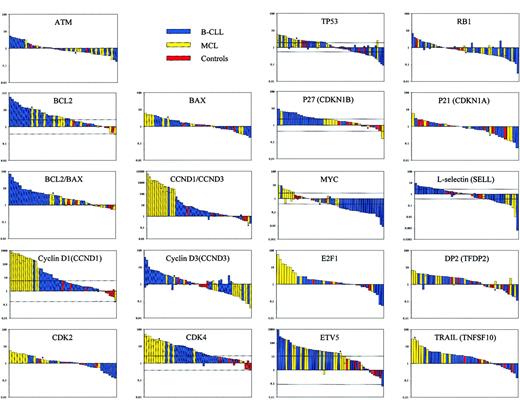

Quantitative expression of the following cell cycle and apoptosis-associated genes were analyzed by RQ-PCR in series of 19 to 34 B-CLL, 6 to 15 MCL, and 5 to 10 CD19+ control samples obtained from healthy persons: ATM, BCL2, BAX, cyclin D1 (CCND1), cyclin D3 (CCND3), CDK2, CDK4, TP53, RB1, p27 (CDKN1B), p21 (CDKN1A), MYC, E2F1, DP2 (TFDP2), ETV5, and TRAIL (TNFSF10) as well as L-selectin (SELL). Furthermore, because of the known interrelationships, the ratios for BCL2/BAX andCCND1/CCND3 were calculated. The data are displayed in Figure 1, and the results of the statistical analyses are presented in Table 2.

Quantitative expression analysis of 17 cell cycle and apoptosis-related genes in B-CLL and MCL.

Relative expression measured by RQ-PCR, normalized to 4 housekeeping genes and control expression data by bar plots, where the height of the bars represents the relative gene expression for individual patient and control samples on a logarithmic scale. Horizontal lines crossing the bars indicate the computed limits for significant up-regulation and down-regulation determined by the maximum χ2 square analysis (Table 2). Each bar represents one patient or control sample. The single MCL without the t(11;14)(q13;q32) translocation is highlighted by an asterisk. Because the RQ-PCR analyses were repeated for the genes BCL2, CCND1, CCND3,CDK4, TP53, RB1, MYC,SELL, TFDP2, and ETV5, a horizontal line in the respective bar shows the resultant value of the second analysis.

Quantitative expression analysis of 17 cell cycle and apoptosis-related genes in B-CLL and MCL.

Relative expression measured by RQ-PCR, normalized to 4 housekeeping genes and control expression data by bar plots, where the height of the bars represents the relative gene expression for individual patient and control samples on a logarithmic scale. Horizontal lines crossing the bars indicate the computed limits for significant up-regulation and down-regulation determined by the maximum χ2 square analysis (Table 2). Each bar represents one patient or control sample. The single MCL without the t(11;14)(q13;q32) translocation is highlighted by an asterisk. Because the RQ-PCR analyses were repeated for the genes BCL2, CCND1, CCND3,CDK4, TP53, RB1, MYC,SELL, TFDP2, and ETV5, a horizontal line in the respective bar shows the resultant value of the second analysis.

For the genes ATM, BAX, RB1,CDKN1A, and TFDP2, there was no statistically significant discrimination between controls and patients (maximally selected χ2 statistics). The maximally selected χ2 statistics tests yielded cut-off values for the genesBCL2, CCND1, CDK4, TP53, CDKN1B, MYC, SELL,and ETV5, indicating significant overexpression or underexpression. BCL2 was up-regulated 2.6- to 57.5-fold in 61.5% of the B-CLL and 58.3% of the MCL patients. The increase inBCL2 expression in B-CLL was particularly evident when the ratio of BCL2 to BAX was calculated. TheCCND1 expression was found to be 43- to 712-fold up-regulated in 93.3% of the MCL patients, corresponding to the known up-regulation in MCL patients as a consequence of the t(11;14) translocation. Interestingly, the single MCL patient without the t(11;14)(q13;q32) translocation (highlighted by asterisk; see Figure 1) did not show an up-regulation of CCND1. In 25.8% of the B-CLL patients, CCND1 was significantly up-regulated in a range of 6- to 196-fold. Analysis of the CDK4 amplicon revealed a 4.9- to 51.3-fold up-regulation in 92.3% of the MCL patients and a 2.65- to 19-fold increase in 56% of the B-CLL patients. The TP53 data resulted in a heterogeneous group in which 38.2% of the B-CLL patients and 43% of the MCL patients were 2.1- to 5.4-fold up-regulated, whereas 12% of B-CLL and 14% of MCL patients were 1.9- to 11-fold down-regulated. Up-regulation of CDKN1Bwas observed in 79% of B-CLL and 20% of MCL samples. RegardingMYC, a 2.8- to 116-fold down-regulation was observed in 54.8% of the B-CLL and 14.3% of the MCL patients. On the other hand, a 2.6- to 9.5-fold up-regulation was shown in 28.6% of the MCL patients. Expression of SELL was increased up to 9.5-fold in 34% of the B-CLL patients but was decreased in 22% of B-CLL patients and 67% of MCL patients. The ETV5 gene was up-regulated up to 910-fold in most of the tested B-cell neoplasias (B-CLL, 68%; MCL, 73%).

Analysis of the RQ-PCR data by CART revealed that the expression ofCCND1, CCND3, CDK2, CDK4, CDKN1B, E2F1, andTNFSF10 allowed a classification concerning the control, B-CLL, and MCL groups. The respective decision regions and overall error rates are listed in Table 2. A 34.4-fold up-regulation of CCND1discriminates well between the MCL and B-CLL patients (compare data in Figure 1). For CCND3, down-regulation by a factor of 4.3 separates 47% of the MCL patients in one group. Normalization ofCCND1 data using CCND3 as calibrator showed no difference to the CCND1 expression profile. TheCDK2 data revealed a group of the MCL patients with more than 3.13-fold up-regulation (53.8%) distinguished from a heterogeneous group of controls and patients below. The CART method indicated 3 groups according to the CDK4 expression level. Controls were separated from the patients by the 2.03-fold increase in expression, and a second cut-off discriminates the MCL patients with a 12.0- to 51.3-fold overexpression (76.9%) from a B-CLL group with 2.03- to 12.0-fold overexpression (84%). Similarly, CDKN1Bexpression data permitted distinction of these 3 groups, clustering 79% of B-CLL patients and one MCL patient (10%) in one group and 50% of the MCL patients in the second group. For E2F1, the cut-off value of 3.83 allowed separation of 67% of the MCLs. According to the expression level of TNFSF10 one group with 45% MCL patients was indicated.

The expression levels of the genes tested, their pathways, and possible interactions are illustrated in graphic format in Figure2. The best separation of the 3 sample groups (B-CLL vs MCL vs control) was achieved when combining the expression parameters of the genes coding for cyclin D1 and CDK4 (Figure 3).

Outline of the major pathways concerning apoptosis and cell cycle and their roles in B-CLL and MCL according to the present study.

The width of the letters and arrows are representative for the expression levels of the affected gene product (inset). Dotted arrows and contoured letters indicate gene mutations and their effects. B-CLL: expression parameters are in strong favor of a protection of the malignant cells from apoptosis but did not provide evidence for promoting cell cycle. MCL: impairment of apoptosis induction seems to play a minor role, whereas most expression data indicate an enhancement of cell proliferation. For details see text.

Outline of the major pathways concerning apoptosis and cell cycle and their roles in B-CLL and MCL according to the present study.

The width of the letters and arrows are representative for the expression levels of the affected gene product (inset). Dotted arrows and contoured letters indicate gene mutations and their effects. B-CLL: expression parameters are in strong favor of a protection of the malignant cells from apoptosis but did not provide evidence for promoting cell cycle. MCL: impairment of apoptosis induction seems to play a minor role, whereas most expression data indicate an enhancement of cell proliferation. For details see text.

Partition for controls, B-CLL, and MCL samples induced by the joint CART analysis.

The decision tree induced by the joined CART analysis is built from rules for CDK4 and CCND1 expression levels. Scatterplot shows the regions as defined by the decision tree. These regions are indicated by large digits. Individual data points are marked by their group membership (C, control; B, B-CLL; M, MCL). Only cases are drawn if expression values were computed for both genes,CDK4 and CCND1. The single MCL without the t(11;14)(q13;q32) translocation is highlighted by an asterisk.

Partition for controls, B-CLL, and MCL samples induced by the joint CART analysis.

The decision tree induced by the joined CART analysis is built from rules for CDK4 and CCND1 expression levels. Scatterplot shows the regions as defined by the decision tree. These regions are indicated by large digits. Individual data points are marked by their group membership (C, control; B, B-CLL; M, MCL). Only cases are drawn if expression values were computed for both genes,CDK4 and CCND1. The single MCL without the t(11;14)(q13;q32) translocation is highlighted by an asterisk.

Discussion

Despite the increasing knowledge of recurrent genomic alterations and the affected corresponding genes in B-CLL and MCL, the pathomechanism of the 2 diseases is not well understood. Although there is considerable overlap between the genomic regions altered in B-CLL and MCL, the clinical courses are very different and there is more aggressiveness in MCL, which suggests differences in the affected pathways. In general, 2 principal phenomena lead to the accumulation of tumor cells and are known to be crucial for malignant diseases: deficiency in programmed cell death and induction or enhancement of cell cycle progression. To elucidate the biochemical processes involved in the pathogenesis of B-CLL and MCL, we analyzed the expression level of a set of genes whose products are known to play central roles in one of these phenomena or even in the selection of apoptotic versus cell proliferation pathways. Furthermore, we analyzed the expression of new candidate genes, located in the frequently altered genomic region 3q26 (TFDP2, ETV5, TNFSF10) and playing a role in distinct apoptotic or cell cycle control pathways. Although cellular expression profiles can be analyzed on even larger sets of genes using arrays,32 33 the quantitative assessment of gene expression using DNA chips is inferior to RQ-PCR. We here report on the detailed analysis of the expression of 17 genes, revealing the yet unknown aberrant expression of a new candidate gene (ETV5), and we provide strong evidence for highly distinctive pathomechanisms in B-CLL and MCL. The potential impact of most of the observed gene up- and down-regulations on the mechanism of each malignancy is summarized in Figure 2.

TP53 and ATM, the genes recurrently mutated in B-CLL and in MCL, function upstream of the immediate cell cycle control. Entry into S phase is tightly associated with the function of the p53 protein, a transcription factor that is stabilized and activated on DNA damage, and in turn it regulates the transcription of a large number of genes, including the p21 inhibitor, which is capable of silencing the cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) essential for S-phase entry.34,35 The inactivation of both alleles of theATM gene by deletion and deleterious point mutations in most of the patients indicated that ATM plays a pathogenic role in MCL.21 P53 and ATM both recognize signals in response to DNA damage and induce repair mechanisms,36 affecting whether a cell continues to proliferate or enters a cell death program. Because there was no deviation of the expression of ATM on the RNA level and the expression of TP53 was heterogeneous, the transcript levels of both genes did not indicate a different use of pathways. In contrast, the RNA level of factors downstream of p53 allowed such an assessment. With respect to the regulation of apoptosis, B-CLL and MCL differ considerably (Figure 2).

The antiapoptotic BCL2 oncogene plays an important role in B-cell malignancies. BCL2 is consistently expressed in B-CLL.37 Hanada et al38 found 2- to 25-fold higher levels than in normal lymphocytes. We could show an even higher range of expression for approximately two thirds of the B-CLL patients and modest up-regulation in more than half the MCL patients. TheBAX data showed no such significant differential expression levels. Because BAX counters the antiapoptotic effect of BCL2 and promotes apoptosis,39 the high ratio of BCL2 toBAX in the patient groups protects the malignant cells from apoptosis, with stronger dominance in B-CLL.

TRAIL (TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand) is a member of the TNF ligand superfamily and is capable of inducing apoptosis.40Interestingly, TRAIL has the potential to kill tumor cells more efficiently than nonmalignant cells.41 Our data indicate an overexpression in 45% of MCL patients that would foster apoptosis but might be antagonized by increased BCL2 levels. Indeed, 3 of the 4 comparable patients showed coactivation of TNFSF10and BCL2, which would argue against a significant role of apoptosis in MCL.

The difference between B-CLL and MCL is even higher with regard to the expression level of factors responsible for cell cycle progression (Figure 2), such as CDKs and coregulators. Cyclin D1 belongs to the G1 cyclins and plays a key role in the cell cycle regulation during G1 phase by cooperating with CDKs.42,43 In MCL, overexpression of cyclin D1 results from the translocation t(11;14), by which CCND1 comes under the control of the immunoglobulin enhancer.44 The MCL samples showed a higher level of cyclin D1 expression than the subset of up-regulated B-CLL samples, indicating a lesser impact in the B-CLL pathomechanism. This is further corroborated by the observed increase in CDKN1B. Interestingly, in B-CLL patients with up-regulation ofCDKN1B, 4 of 6 also showed an increase in expression ofCDK4. Because p27 antagonizes the proliferative effect of CDK–cyclin complexes, this observation argues further against an enhancement of cell cycle progression in B-CLL. Conversely, MCLs were shown to have increased p27 protein degradation,45possibly contributing to the up-regulation of CDK–cyclin complexes in this disease. Cyclin D3 functions similarly to cyclin D1 by activating CDK4 and CDK6,46 and it acts together with cyclin D2 as a main regulator for the G1/S phase transition.47 Motokura et al48 found in synchronized HeLa cells that the mRNA levels of cyclin D1 and cyclin D3 were regulated reciprocally throughout the cell cycle. For cyclin D3 we were able to demonstrate lower expression levels for 47% of the MCL patients, which correlates with a cyclin D1-mediated induction of a consecutive down-regulation of cyclin D3.47

CDK4 and CDK6 form complexes with D-type cyclins, the most important substrate of which is RB1 and related pocket proteins. Increased expression in CDK4 is again higher in MCL, corresponding to the higher level of cyclin D1 in this disease. Because CDK2 is also highly expressed in MCL, cyclin-dependent activation of cell cycle progression is a key aspect of the pathomechanism of mantle cell lymphoma. In line with this observation is the inactivation of the CDK4 inhibitor p16 through genomic alterations.49-51 The up-regulation ofCDK2, CDK4, and CCND1 is likely to result in the activation of RB1, upon which E2F is released and the transcription of S-phase enzymes is induced.52,53 In line with the activation of this central pathway is the finding of a higher expression of E2F1 transcripts in two thirds of the MCL patient group: E2F1 is a member of the E2F family, which is specifically active in late G1 and the subsequent S phase of the cell cycle.54

Because MYC plays an activating role in CDK–cyclin complexes, mitogen-induced or ectopically expressed MYC also shifts quiescent cells into the S phase.53 55 More than 28% of the MCL patients showed up-regulated expression, and approximately 55% of the B-CLL patients showed down-regulated expression. Thus, the RNA expression level of this gene is again in full agreement with the overall picture emerging from this study, which is that cell cycle progression is the dominant effect in MCL but is only of minor importance in B-CLL.

Extensive statistical analysis of the expression data resulted in the identification of genes whose expression provides the best discrimination between the 2 B-cell lymphomas and the control samples. As presented in Figure 3, the best separation of the 3 sample groups was achieved when combining the expression parameters of the genes coding for cyclin D1 and CDK4. Thus, it can be predicted that diagnostic tools for the distinction of MCL and B-CLL, which are based on assessment of the transcript level as shown for cyclin D1 alone,23 would be highly specific if the test is a combination of these 2 markers.

Because 3q26 is frequently altered in MCL (48%) and in B-CLL (5%), 3 genes localized within this chromosome band and associated with apoptotic or cell cycle control pathways were selected for this study—the E2F dimerization partner DP2, the Ets-related transcription factor ETV5, and the apoptosis-inducing ligand TRAIL. The expression level of these 3 genes did not correlate with the presence of genomic aberrations. Interestingly, a significantly high expression ofETV5 was found in 68% of the B-CLLs and in 73% of the MCLs. Although the absolute ratio of ETV5 expression in neoplastic versus normal cells should be qualified based on the low expression levels observed in normal cells, the data clearly show that ETV5 expression is characteristic for the investigated malignant cells. ETV5 or ERM (Ets-related molecule PEA3-like) belongs to the PEA3 superfamily of Ets transcription factors, which are involved in tumorigenesis and developmental processes and interact with promoters of several genes via the ETS domain. The transcriptional activator ETV5 is a target for the Ras/Raf-1/MAPK pathway and can also be activated through the protein kinase A.56 Because the pattern of proliferation of B-CLL and MCL cells is highly distinct but ETV5 is overexpressed in both disease cell populations, ETV5 seems not to play a direct role in mitogenic responses of MCL and B-CLL cells. Because target genes for ETV5 have not been identified, its role in tumorigenesis is still elusive. c-Jun, another oncogenic factor, acts synergistically on the transcription activity of ETV5.57 PEA3 group members, including ETV5, are overexpressed in metastatic human breast cancer cells and mouse mammary tumors and might therefore play an important role in mammary oncogenesis.58 Thus, our finding of a strong up-regulation of ETV5 in B-CLL and MCL suggests this gene as a new candidate for the pathomechanism of B-cell lymphomas.

We are grateful to Gunnar Wrobel (Heidelberg) for helpful discussions and Margit Pförsich (Ulm) for assistance in cell sorting.

Supported in part by grants from the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (01KW 9935) and the European community (QLG1-CT2000-00687).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Peter Lichter, Abteilung Organisation komplexer Genome (H0700), Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, Im Neuenheimer Feld 280, D-69120 Heidelberg, Germany; e-mail: m.macleod@dkfz.de.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal