The consequences of T-cell activation depend exclusively on costimulation during antigen–T-cell receptor interaction. Interaction between the T-cell coreceptor CD28 and its ligand B7 during antigen-antigen receptor engagement results in full activation of T cells, the outcomes of which are proliferation and effector functions. The ability of CD28 to costimulate the production of interleukin-2 (IL-2) explains the importance of this costimulation. The signaling event mediated by CD28 engagement has been proposed to have 2 components: one is sensitive to the immunosuppressive drug cyclosporin A (CsA), and the other one is CsA-resistant. In this report, we demonstrate that the CsA-resistant pathway is sensitive to the immunosuppressive drug rapamycin. Treatment with rapamycin blocked IL-2 production after activation of human peripheral blood T cells with phorbol ester (PMA) and anti-CD28 (CsA-resistant pathway), whereas this drug did not have any effect on PMA plus ionomycin stimulation (CsA-sensitive pathway). The inhibitory effect of rapamycin was on messenger RNA stability and translation, rather than on IL-2 transcription or protein turnover.

Introduction

Costimulation plays an important role in the outcome of T-cell activation. When T-cell antigen receptors (TCRs) interact with antigen-major histocompatibility complex in the absence of coreceptor engagement, T cells become nonfunctional, a state usually referred to as anergy. However, if T cells receive costimulation during antigen-TCR interaction, T cells become functionally activated, and the outcomes are proliferation and the generation of effector populations. CD28 is one important coreceptor, which regulates T-cell proliferation and survival. The ability to costimulate the production of interleukin-2 (IL-2) and induce Bcl-XL gene expression comprise important roles that CD28 signaling plays in T-cell activation.1-3 Besides IL-2, CD28 costimulation also induces other important cytokine genes, including interferon-γ (IFN-γ), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and IL-8.4 These effects of CD28 ligation on cytokine gene expression have been shown to occur by both transcriptional and posttranscriptional (messenger RNA [mRNA] stability) mechanisms.5-7

Although significant work has been done to elucidate the signaling pathways involved in CD28 costimulation, a complete understanding of these pathways is yet to be achieved. It is not clear whether CD28 engagement generates a unique signaling pathway that complements TCR signaling or whether CD28 signaling potentiates TCR-mediated signaling to decrease the threshold of T-cell activation.8,9 It has been proposed that CD28 signaling has 2 components: one is calcium dependent and sensitive to cyclosporin A (CsA) similar to TCR signaling, and the other one is calcium independent and resistant to CsA.10 One of the first signaling molecules directly involved with activated CD28 was phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K), although the role of PI3-K in CD28 signaling remains controversial.11-13 Recently, it has been shown that transgenic mice or primary T cells carrying a CD28 mutant that lacks ability to bind PI3-K were capable of distinguishing proliferative signals from survival signals. These cells were unable to express Bcl-XL, whereas their ability to proliferate and to produce IL-2 were intact.14-16 Previously, it has been shown that signals originating from TCR and CD28 converge on the activation of jun N-terminal kinase (JNK),17 but Vav-1, a protooncogene product, has been shown to be the point of integration for the 2 activation signals and lies upstream to the JNK signaling pathway.18-21

Rapamycin is a macrolide antibiotic with potent immunosuppressive properties. Rapamycin is structurally related to the well-known immunosuppressant FK506 and binds to the same intracellular receptor FKBP12 (FK506-binding protein).22 Interestingly, although both FK506 and rapamycin bind to the same intracellular receptor, the principal target proteins are different for these 2 compounds. Whereas FK506-FKBP12 inhibits the serine-threonine phosphatase calcineurin, rapamycin-FKBP12 inhibits the serine-threonine kinase mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin)/FRAP (FKBP12–rapamycin-associated protein).23-28 Rapamycin treatment has been shown to cause G1 arrest in a variety of cell types, including T cells.29,30 The inhibition of T-cell proliferation is primarily due to the blockage of IL-2 signaling,31,32supporting the clinical use of rapamycin as an immunosuppressant.33 It has been well established that mTOR is a key regulator of translation,34 and 2 of the most important components in the translational process that are regulated by mTOR are 4EBP-1 and p70s6k.344EBP-1 is a repressor of eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF4E) and is regulated by a phosphorylation/dephosphorylation mechanism.35 The availability of the eIF4E is critical for translation and is dependent on the phosphorylation status of 4EBP-1. Hypophosphorylated 4EBP-1 binds to eIF4E and prevents it from forming a productive mRNA cap binding complex, whereas phosphorylation of 4EBP-1 abrogates this interaction.36 Another target of mTOR is p70s6k, which phosphorylates S6 protein of the 40S ribosome, and is important in regulating the translation of an essential family of mRNAs that contain an oligopyrimidine tract at their transcription start site.37 38

Depending on the primary stimulation, CD28 can initiate multiple pathways. One of these pathways is CsA resistant and has been suggested to be involved in graft-versus-host disease during allogenic bone marrow transplantation.39 Surprisingly, very little is known about this pathway. In this report we demonstrate the effect of rapamycin on the CsA-resistant pathway of CD28 costimulation. Rapamycin treatment inhibited the production of IL-2 by activated human peripheral blood T cells. The inhibition of IL-2 production was mainly due to the blockage of the CsA-resistant pathway, because rapamycin had no effect on the CsA-sensitive pathway. The mechanism of the effect of rapamycin on the IL-2 production was observed at 2 levels: decreased translation and decreased mRNA stability.

Materials and methods

Cells and tissue cultures

Freshly purified human peripheral blood T cells were obtained from healthy donors who provided informed consent. The T cells were more than 95% CD3+ cells. Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 2 mM glutamine. Phorbol ester (PMA; Sigma, St Louis, MO) was used at 10 ng/mL, ionomycin (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) at 1 μg/mL, and αCD28 monoclonal antibody 9.3 (kindly provided by Dr Carl H. June, University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA) at 100 ng/mL. CsA, rapamycin, okadaic acid, and actinomycin D were purchased from Calbiochem, and LY294002 was purchased from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA).

Antibodies

Anti–JNK-1 (C-17; sc-474) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Antiphospho 4EBP-1 (Ser65; No. 9451S), antiphospho p70s6k (Thr421/Ser424; No. 9204S), and antiphospho p38 (Thr180/Tyr 182; No. 9211S) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). C-Jun (1-169-GST; catalog No. 14195), antihuman Stat5A (No. 06-553), and Stat5B (No. 06-554) were purchased from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY).

IL-2 assay

A total of 2 × 106 T cells/mL was stimulated with various conditions overnight at 37°C. In the case of CsA, rapamycin, or okadaic acid, cells were pretreated for 1 hour. After incubation, supernatants were collected, and the IL-2 was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay by using Human IL-2 Flexia Kit from Biosource (Camarillo, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

The preparation of nuclear extracts and electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) were performed as described previously.40 The oligonucleotide corresponding to the consensus Stat-binding site from FcgRI promoter was tcgaCGCATGTTTCAAGGATTTGAGATGTATTTCCCAGAAAAGGc. During supershift assay, anti-Stat5A and B were added to the binding reaction 15 minutes before the addition of the radiolabeled probe.

Northern blot analysis

Total RNA was isolated by solubilization in guanidine thiocyanate as described by Chomczynski and Sacchi.41Total RNA (10 μg) was electrophoresed on formaldehyde agarose gels and transferred to GeneScreen Plus membranes. A 400–base pair polymerase chain reaction product corresponding to a portion of the IL-2 complementary DNA (cDNA) was used as a probe. To study mRNA stability, T cells were stimulated with PMA/αCD28 in the presence or absence of rapamycin (20 ng/mL) for 18 hours. Actinomycin D (10 μg/mL) was then added, and the cultures were then incubated further for various periods of times. After incubations, cells were harvested, and total RNAs were isolated for Northern blot analysis.

Western blotting and kinase assay

Whole cell lysates were prepared as described previously.42 For Western blot analysis, 25 μg cell lysates were analyzed on 12% polyacrylamide gels. The proteins were electrotransferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA). Detection of specific phosphoproteins was carried out with ECL-Plus Western blotting kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). For kinase assay, 35 μg cellular lysates were immunoprecipitated by anti–JNK-1 antibody (1.5 μg). To capture immunocomplexes, protein G-agarose (10 μL 50% slurry) was first incubated with the antibody in the extraction buffer for 1 hour at 4°C. The antibody-protein G-agarose was then washed with extraction buffer without Triton X-100 and was exposed to the lysates for 1 more hour at 4°C. After extensive wash, immunocomplexes were incubated in kinase buffer (25 mM HEPES, pH 7.7, 20 mM MgCl2, 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, 20 mM p-nitrophenylphosphate, 0.1 mM sodium ortho vanadate, 2 μg/mL E64, 10 μg/mL phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 2 mM dithiothreitol) containing 0.1 mM adenosine triphosphate (ATP). The kinase reaction was started by adding 2 μg GST–c-Jun (1-169) and 2 μCi (0.074 MBq) [γ-32P] ATP (10 Ci/mmol [37 × 1010 Bq], NEN Life Science Products, Boston, MA), and the reaction mixture was incubated at 30°C for 30 minutes with frequent mixing. The reaction was stopped by adding NuPAGE LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The samples were boiled for 6 minutes and were analyzed on 10% NuPAGE Novex Bis-Tris Gels using MES SDS buffer (Invitrogen).

Results

Effect of rapamycin on the production of IL-2 by activated T cells

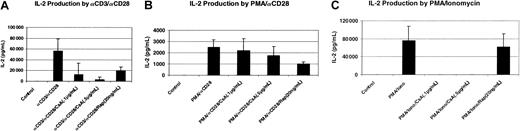

It has been reported that IL-2 signaling in activated T cells is rapamycin sensitive, whereas IL-2 production is rapamycin insensitive.31,32 Other reports show that IL-2 production by activated T cells is sensitive to rapamycin.43 44 To investigate the effect of rapamycin on the IL-2 production by activated T cells, we used freshly isolated human peripheral blood T cells. As shown in Figure 1A, T cells stimulated with cross-linked αCD3 and αCD28 produced a significant amount of IL-2, and this production was suppressed significantly by the pretreatment of the cells with rapamycin.

Effect of rapamycin on the production of IL-2 by activated T cells.

Human peripheral blood T cells (2 × 106/mL) were stimulated with either plate-bound αCD3 (200 ng/mL) plus soluble αCD28 (100 ng/mL) (A), or with PMA (10 ng/mL) plus αCD28 (B), or with PMA plus ionomycin (1 μg/mL) (C) for 24 hours at 37°C. For drug treatment, T cells were pretreated for 1 hour with either CsA or rapamycin (Rap). Supernatants were collected for IL-2 assay as described in “Materials and methods.” Four different donors were used in this assay.

Effect of rapamycin on the production of IL-2 by activated T cells.

Human peripheral blood T cells (2 × 106/mL) were stimulated with either plate-bound αCD3 (200 ng/mL) plus soluble αCD28 (100 ng/mL) (A), or with PMA (10 ng/mL) plus αCD28 (B), or with PMA plus ionomycin (1 μg/mL) (C) for 24 hours at 37°C. For drug treatment, T cells were pretreated for 1 hour with either CsA or rapamycin (Rap). Supernatants were collected for IL-2 assay as described in “Materials and methods.” Four different donors were used in this assay.

Previous studies have shown that the immunosuppressive drug CsA drastically inhibits, but does not completely block, IL-2 production following stimulation with αCD3 and αCD28.4 The drug-resistant activity can most likely be traced to the CD28 signaling pathway, because stimulation of cells with PMA (to mimic Ca++-independent aspects of CD3 signaling) and αCD28 is entirely resistant to CsA. However, the CsA-sensitive pathway can be mimicked by stimulation with PMA and ionomycin.4 We wanted to know whether the immunosuppressive properties of rapamycin were due to the inhibition of CsA-resistant pathway. Peripheral blood T cells were stimulated either with PMA plus αCD28 or with PMA plus ionomycin in the presence or absence of either CsA or rapamycin. As shown in Figure 1B and C, PMA/αCD28 was a weaker stimulus to IL-2 production; however, CsA had minimal effect on PMA/αCD28 stimulation, whereas this treatment completely blocked PMA/ionomycin-mediated IL-2 production. In contrast, rapamycin significantly inhibited PMA/αCD28-induced IL-2 production, whereas it did not have any effect on PMA/ionomycin stimulation. Similar effects were also observed at a lower dose of rapamycin (10 ng/mL) (data not shown). These data suggest that rapamycin alters IL-2 production by activated T cells, and this suppressive effect is mediated by the sensitivity of the CsA-resistant CD28 costimulatory pathway to rapamycin.

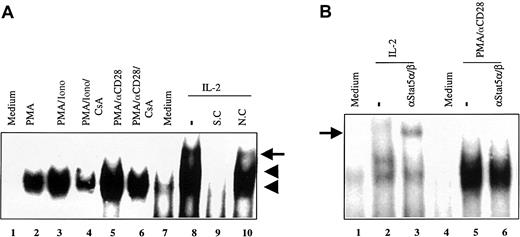

Because the effect of rapamycin has been reported to be due to blocking IL-2 signaling, it was important to demonstrate that no IL-2 signaling was involved in the suppressive effect of rapamycin on the CsA-resistant CD28 costimulatory pathway. We decided to use a sensitive assay to monitor the involvement of IL-2 signaling. We performed EMSA by using the consensus Stat-binding site from the FcγRI promoter to detect Stat 5α and β, 2 IL-2–specific Stats.45,46 As shown in Figure 2A, one inducible DNA–protein complex was observed after stimulation of T cells with PMA, PMA/ionomycin, or PMA/αCD28 (lanes 2, 3, and 5). This complex was specific as determined by the competition analysis using specific and nonspecific competitors (data not shown). Stimulation of preactivated T cells with IL-2 produced 3 inducible DNA–protein complexes (indicated by 2 arrowheads and an arrow; lane 8 versus lane 7), 2 of which were specific (indicated by the arrowheads) as determined by the competition analysis (lanes 9 and 10). To determine whether Stat 5α and β were part of the inducible DNA–protein complexes, supershift analysis was performed by using αStat 5α and β antisera (Figure 2B). The combination of αStat 5α and β did not react with the PMA/αCD28-inducible complex (lane 6 versus lane 5), and this finding was also true for PMA/ionomycin-inducible complex (data not shown). In contrast these antisera supershifted the IL-2–induced upper complex as shown in the earlier report (lane 3 versus lane 2).47 Thus, the rapamycin-sensitive pathway does not appear to involve IL-2 signaling. These data suggest that the effect of rapamycin on PMA/αCD28-mediated signaling was not due to the blockage of IL-2 signaling.

EMSA using consensus Stat-binding site from FcγRI promoter.

(A) Nuclear extracts (5 μg) from peripheral blood T cells treated with medium alone (lane 1), PMA (lane 2), PMA/ionomycin (lane 3), PMA/ionomycin/CsA (lane 4), PMA/αCD28 (lane 5), and PMA/αCD28/CsA (lane 6) for 20 hours were used in EMSA. Nuclear extracts from preactivated T cells treated with medium alone (lane 7) and with IL-2 (100 U/mL; lane 8) were also used in the EMSA. 32P-labeled Stat-binding site from FcγRI promoter was used as a probe. Lanes 9 and 10 represent competition assays using an unlabeled oligonucleotide corresponding to the promoter sequence as a specific competitor (S.C.), and an oligonucleotide corresponding to the IFN-γ promoter sequence as a nonspecific competitor (N.C.). The arrowheads represent the specific bands, and the arrow indicates the nonspecific band. (B) Supershift assay using nuclear extracts from either preactivated T cells treated with medium alone (lane 1), and IL-2 (lanes 2-3), or T cells treated with medium alone (lane 4) and PMA/αCD28 (lanes 5-6). The arrow indicates the supershifted complex.

EMSA using consensus Stat-binding site from FcγRI promoter.

(A) Nuclear extracts (5 μg) from peripheral blood T cells treated with medium alone (lane 1), PMA (lane 2), PMA/ionomycin (lane 3), PMA/ionomycin/CsA (lane 4), PMA/αCD28 (lane 5), and PMA/αCD28/CsA (lane 6) for 20 hours were used in EMSA. Nuclear extracts from preactivated T cells treated with medium alone (lane 7) and with IL-2 (100 U/mL; lane 8) were also used in the EMSA. 32P-labeled Stat-binding site from FcγRI promoter was used as a probe. Lanes 9 and 10 represent competition assays using an unlabeled oligonucleotide corresponding to the promoter sequence as a specific competitor (S.C.), and an oligonucleotide corresponding to the IFN-γ promoter sequence as a nonspecific competitor (N.C.). The arrowheads represent the specific bands, and the arrow indicates the nonspecific band. (B) Supershift assay using nuclear extracts from either preactivated T cells treated with medium alone (lane 1), and IL-2 (lanes 2-3), or T cells treated with medium alone (lane 4) and PMA/αCD28 (lanes 5-6). The arrow indicates the supershifted complex.

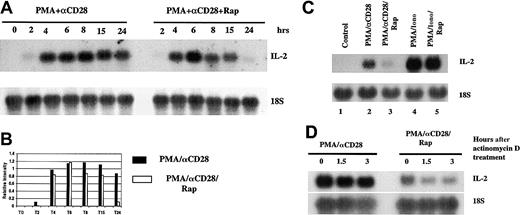

Rapamycin affects PMA/CD28-mediated IL-2 message stability

To determine whether the effect of rapamycin on IL-2 production was transcriptional or posttranscriptional, we performed Northern blot analysis using total RNAs. T cells were stimulated with PMA/αCD28 in the presence or absence of rapamycin for various periods of times, and total RNAs were isolated and were analyzed by Northern blot analysis. As shown in Figure 3A, IL-2 message was detected as early as 2 hours, peaked about 6 hours, and stayed at high levels for at least 24 hours. Interestingly, pretreatment with rapamycin did not alter the induction of IL-2 message at the earlier time points, although this treatment did suppress the mRNA level at 24 hours. Figure 3B shows the graphical representation of the IL-2 mRNA levels quantitated and normalized with the 18S ribosomal RNA. These data suggest that rapamycin did not have any effect on IL-2 gene transcription. We tested the effect of rapamycin on the transient transfection assay by using an IL-2 promoter-reporter construct. Rapamycin did not affect PMA/αCD28-mediated promoter activity (data not shown), which is in agreement with the recent report by Kane et al.48 Therefore, rapamycin does not act at the level of the IL-2 promoter. To examine the differential effect of rapamycin on PMA/CD28 versus PMA/ionomycin-induced IL-2 mRNA levels, peripheral blood T cells were stimulated with either medium alone, PMA/αCD28, or PMA/ionomycin in the presence or absence of rapamycin for 18 hours. Total RNAs extracted from activated T cells were analyzed by Northern blot analysis. As shown in Figure 3C, PMA/αCD28-induced IL-2 mRNA level was reduced by rapamycin pretreatment (compare lane 3 with lane 2), whereas rapamycin did not have any effect on PMA/ionomycin-induced IL-2 mRNA level (lane 5 versus lane 4). The difference in the IL-2 mRNA levels between PMA/αCD28 versus PMA/ionomycin stimulation reflects the difference in the IL-2 production by these 2 sets of stimuli (Figure 1B,C).

Effect of rapamycin on PMA/CD28-induced IL-2 mRNA.

(A) Total RNAs (10 μg) from peripheral blood T cells treated with PMA plus αCD28 in the presence (right panel) or absence (left panel) of rapamycin for various periods of times were analyzed by Northern blot analysis (upper panel). A polymerase chain reaction–amplified fragment corresponding to a portion of IL-2 cDNA was used as a probe. The same membrane was stripped and reprobed with an 18s ribosomal RNA probe (lower panel). (B) Graphical representation of the IL-2 mRNA levels quantitated and normalized with 18S ribosomal RNA. (C) Northern blot analysis using total RNAs (10 μg) from T cells stimulated with either medium alone, PMA/αCD28, or PMA/ionomycin in the presence or absence of rapamycin for 18 hours. (D) Peripheral blood T cells were stimulated for 18 hours in the presence or absence of rapamycin. Actinomycin D was then added, and the cultures were incubated further for various periods of times. After each point cells were harvested; total RNAs were isolated and analyzed by Northern blot analysis.

Effect of rapamycin on PMA/CD28-induced IL-2 mRNA.

(A) Total RNAs (10 μg) from peripheral blood T cells treated with PMA plus αCD28 in the presence (right panel) or absence (left panel) of rapamycin for various periods of times were analyzed by Northern blot analysis (upper panel). A polymerase chain reaction–amplified fragment corresponding to a portion of IL-2 cDNA was used as a probe. The same membrane was stripped and reprobed with an 18s ribosomal RNA probe (lower panel). (B) Graphical representation of the IL-2 mRNA levels quantitated and normalized with 18S ribosomal RNA. (C) Northern blot analysis using total RNAs (10 μg) from T cells stimulated with either medium alone, PMA/αCD28, or PMA/ionomycin in the presence or absence of rapamycin for 18 hours. (D) Peripheral blood T cells were stimulated for 18 hours in the presence or absence of rapamycin. Actinomycin D was then added, and the cultures were incubated further for various periods of times. After each point cells were harvested; total RNAs were isolated and analyzed by Northern blot analysis.

Next we wanted to test the effect of rapamycin on IL-2 mRNA stability. Peripheral blood T cells were treated with PMA/αCD28 in the presence or absence of rapamycin for 18 hours. At 18 hours actinomycin D was added to the culture to stop new RNA synthesis, and cells were incubated further for either 1.5 or 3 more hours. At each time point, cells were collected and RNAs were isolated for Northern blot analysis. As shown in Figure 3D, PMA/αCD28-induced IL-2 mRNA was fairly stable throughout the time of actinomycin D treatments (lanes 1-3). In contrast, addition of rapamycin caused rapid degradation of IL-2 message (lanes 4-6). These data suggest that the effect of rapamycin on PMA/αCD28-mediated IL-2 production was mediated by increasing the turnover of IL-2 mRNA.

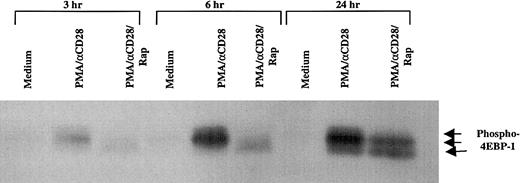

Effect of rapamycin on the phosphorylation status of 4EBP-1

It has been well established that mTOR, the target of rapamycin, plays an important role in translation.34 One of the important components in translation that is directly regulated by mTOR is 4EBP-1, a repressor of eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E), whose phosphorylation status dictates the initiation of translation.35 To examine the effect of PMA/CD28 stimulation on the phosphorylation status of 4EBP-1, peripheral blood T cells were stimulated with PMA/αCD28 for various periods of time, and the whole cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot analysis by using an antibody specific for phospho–4EBP-1 that is phosphorylated on Ser-65. As shown in Figure 4, multiple phosphorylated forms of 4EBP-1 were observed as early as 3 hours after stimulation, and the amount of phosphorylated proteins increased with time. Pretreatment of these cells with rapamycin caused the dephosphorylation of 4EBP-1, and this effect of rapamycin was observed as early as 3 hours. The effect of rapamycin was specific to PMA/CD28 stimulation, because PMA/ionomycin-induced multiple phosphorylated forms of 4EBP-1 were unaffected by rapamycin (data not shown). These and the data presented above demonstrate that rapamycin inhibits PMA/αCD28-mediated IL-2 production by 2 mechanisms: first, decreased translation of IL-2, which is the earliest effect, and second, decreased mRNA stability, which is the later effect.

Effect of rapamycin on PMA/CD28-induced phosphorylation status of 4EBP-1.

Peripheral blood T cells were treated with either medium alone, PMA/αCD28, or PMA/αCD28 plus pretreated rapamycin for various periods of times. Total cellular lysates (25 μg) were analyzed by immunoblotting with an antibody specific for phospho–4EBP-1 that is phosphorylated on Ser-65. Arrows indicate the different phosphorylated forms of 4EBP-1.

Effect of rapamycin on PMA/CD28-induced phosphorylation status of 4EBP-1.

Peripheral blood T cells were treated with either medium alone, PMA/αCD28, or PMA/αCD28 plus pretreated rapamycin for various periods of times. Total cellular lysates (25 μg) were analyzed by immunoblotting with an antibody specific for phospho–4EBP-1 that is phosphorylated on Ser-65. Arrows indicate the different phosphorylated forms of 4EBP-1.

Effect of rapamycin on PMA/CD28-mediated JNK-1 activity

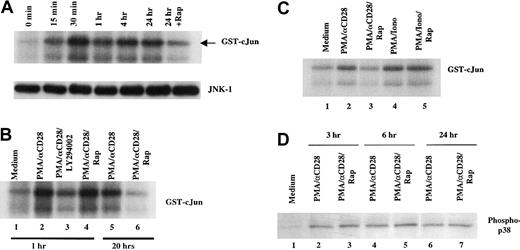

To determine the signaling pathways involved in the rapamycin-mediated IL-2 message instability, we examined PMA/αCD28-induced JNK-1 activity. JNK-1 has been shown to play an important role in IL-2 mRNA stability in activated T cells.49 Human peripheral blood T cells were stimulated with PMA/αCD28 for various periods of time. Whole cell lysates were prepared, and the immunocomplex kinase assay was performed according to the protocol described in “Materials and methods.” As shown in Figure 5A, PMA/αCD28 treatment induced kinase activity as early as 15 minutes, peaked around 30 minutes, and maintained a high level of activity for at least 24 hours. Interestingly, pretreatment of rapamycin suppressed JNK-1 activity at the 24-hour time point (Figure 5A, upper panel). The inhibition of JNK activity was not due to the difference in JNK protein level, because rapamycin treatment did not alter the JNK level (Figure 5A, lower panel). The effect of rapamycin was not observed at earlier time points as shown in Figure 5B. Pretreatment with rapamycin did not alter JNK-1 activity at the 1-hour assay (lane 4 versus lane 2), whereas it did affect the activity at the 20-hour time point (lane 6 versus lane 5). The time course of rapamycin treatments demonstrated a requirement of at least 18 hours for the inhibition of JNK-1 activity (data not shown). These data suggest the involvement of mTOR/FRAP in the PMA/αCD28-mediated JNK-1 activation.

Effect of rapamycin on PMA/CD28-induced JNK-1 activity.

(A) Upper panel, time course of JNK activation after PMA/CD28 stimulation. Total cellular lysates (35 μg) from peripheral blood T cells treated with PMA plus αCD28 for various periods of times were used in immunocomplex kinase assay for JNK-1 using recombinant GST-c-Jun (1-169) as substrate. The phosphorylated GST-c-Jun is indicated by an arrow. The faster migrating phosphorylated band is the shorter form of GST-c-Jun (1-169). Lower panel, equal amounts of lysates from time course analysis were analyzed by Western blot analysis using anti-JNK antibody. (B) Effect of LY294002 and rapamycin on PMA/CD28-induced JNK activity. Immunocomplex kinase assays for JNK-1 were performed using total cellular lysates (35 μg) from T cells treated with medium alone, PMA/αCD28 in the presence or absence of LY294002 or rapamycin for 1 hour, or PMA/αCD28 in the presence or absence of rapamycin for 20 hours. (C) Differential effect of rapamycin on PMA/CD28- versus PMA/ionomycin-induced JNK activity. Total cellular lysates (35 μg) from T cells treated with medium alone, PMA/αCD28 in the presence or absence of rapamycin, and PMA/ionomycin in the presence or absence of rapamycin for 18 hours were used for kinase assays. (D) Peripheral blood T cells were treated with medium alone, PMA/αCD28, or PMA/αCD28 plus pretreated rapamycin for various periods of times. Total cellular lysates (25 μg) were analyzed by immunoblotting with an antibody specific for the activated form of p38 that is phosphorylated on The-180 and Tyr-182.

Effect of rapamycin on PMA/CD28-induced JNK-1 activity.

(A) Upper panel, time course of JNK activation after PMA/CD28 stimulation. Total cellular lysates (35 μg) from peripheral blood T cells treated with PMA plus αCD28 for various periods of times were used in immunocomplex kinase assay for JNK-1 using recombinant GST-c-Jun (1-169) as substrate. The phosphorylated GST-c-Jun is indicated by an arrow. The faster migrating phosphorylated band is the shorter form of GST-c-Jun (1-169). Lower panel, equal amounts of lysates from time course analysis were analyzed by Western blot analysis using anti-JNK antibody. (B) Effect of LY294002 and rapamycin on PMA/CD28-induced JNK activity. Immunocomplex kinase assays for JNK-1 were performed using total cellular lysates (35 μg) from T cells treated with medium alone, PMA/αCD28 in the presence or absence of LY294002 or rapamycin for 1 hour, or PMA/αCD28 in the presence or absence of rapamycin for 20 hours. (C) Differential effect of rapamycin on PMA/CD28- versus PMA/ionomycin-induced JNK activity. Total cellular lysates (35 μg) from T cells treated with medium alone, PMA/αCD28 in the presence or absence of rapamycin, and PMA/ionomycin in the presence or absence of rapamycin for 18 hours were used for kinase assays. (D) Peripheral blood T cells were treated with medium alone, PMA/αCD28, or PMA/αCD28 plus pretreated rapamycin for various periods of times. Total cellular lysates (25 μg) were analyzed by immunoblotting with an antibody specific for the activated form of p38 that is phosphorylated on The-180 and Tyr-182.

As it has been reported by others,50 pretreatment with LY294002, an inhibitor of PI3-K, inhibited PMA/αCD28-induced JNK-1 activity (Figure 5B, lane 3 verus lane 2), indicating the involvement of PI3-K in this pathway. To demonstrate the specificity of the rapamycin effect, PMA/ionomycin-treated lysates were compared with PMA/αCD28-treated lysates in the JNK-1 assay (Figure 5C). Pretreatment with rapamycin did not alter PMA/ionomycin-induced JNK-1 activity (lanes 5 versus 4), whereas this treatment did inhibit PMA/αCD28-induced JNK-1 activity (lanes 3 versus 2). These data reinforce the fact that rapamycin only blocks the CsA-resistant pathway of CD28 costimulation.

Previously it has been shown that PMA/αCD28 stimulation also activates p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase.18 To examine whether p38 plays any role in IL-2 mRNA stability, we tested the effect of rapamycin on the PMA/αCD28-induced p38 by Western blot analysis using antiphospho p38 antiserum (Figure 5D). The phospho-p38 was induced as early as 3 hours and was present at the same levels for at least 24 hours. Interestingly, this induction was unaffected by rapamycin pretreatment. These data indicate the possible involvement of JNK-1 but not p38 in the PMA/αCD28-mediated IL-2 message stability.

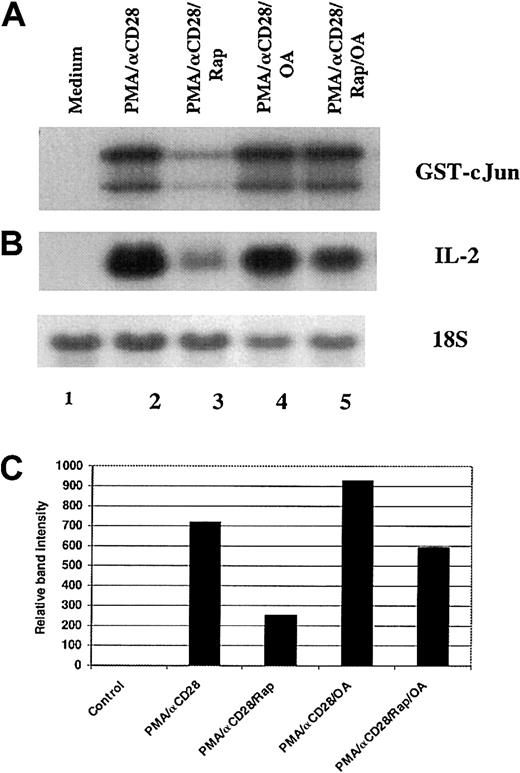

Role of PP2A in the rapamycin-mediated down-regulation of JNK-1 activity

It has been reported that rapamycin-induced dephosphorylation of p70S6K and 4E-BP1 was mediated by PP2A.51 To examine the role of PP2A in the inhibition of PMA/αCD28-induced JNK activity by rapamycin, peripheral blood T cells were stimulated with PMA plus αCD28 for 19 hours in the presence or absence of rapamycin and/or okadaic acid. As shown in Figure6A, pretreatment with rapamycin inhibited PMA/αCD28-induced JNK-1 activity (lanes 3 versus 2), and this inhibition was blocked by addition of okadaic acid to the rapamycin treatment (lanes 5 versus 3), whereas pretreatment with okadaic acid alone did not affect PMA/αCD28-induced JNK-1 activity (lanes 4 versus 2). These data suggest that rapamycin-induced blockage of JNK-1 activity was mediated by PP2A/PP1. To check whether the reversal of JNK-1 inhibition by okadaic acid was reflected in the IL-2 mRNA stability, Northern blot analysis was performed by using RNAs isolated from the same experiment as described in Figure 6A. Like the JNK assay, the suppression of PMA/αCD28-induced IL-2 message by rapamycin was reversed by simultaneous treatment with okadaic acid (Figure 6B, lanes 5 versus 3), whereas okadaic acid treatment alone did not alter PMA/αCD28-induced IL-2 mRNA level (Figure 6B, lanes 4 versus 2). Figure 6C shows the IL-2 mRNA levels quantitated and normalized with 18S ribosomal RNA. These data strongly suggest the possible involvement of JNK-1 in rapamycin-mediated IL-2 mRNA instability.

Role of PP2A/PP1 in the rapamycin-mediated down-regulation of JNK-1 activity and IL-2 mRNA level.

Peripheral blood T cells were stimulated for 18 hours with either medium alone (lane 1), PMA/αCD28 in the presence (lane 3) or absence of rapamyin (lane 2), PMA/αCD28 in the presence of rapamycin plus okadaic acid (OA; lane 4), or PMAS/αCD28 in the presence of OA (lane 5). After stimulation, cells were divided into 2 groups: one half was used for cellular lysate preparation, and the other half was used to isolate total RNAs. (A) Equal amounts of cellular lysates (35 μg) were used in the immunocomplex kinase assays for JNK-1 using recombinant GST-c-Jun (1-169) as substrate. (B) Equal amounts of RNAs (10 μg) were analyzed by Northern blot analysis using a fragment of IL-2 cDNA as a probe. (C) Graphical representation of the IL-2 mRNA levels quantitated and normalized with 18S ribosomal RNA.

Role of PP2A/PP1 in the rapamycin-mediated down-regulation of JNK-1 activity and IL-2 mRNA level.

Peripheral blood T cells were stimulated for 18 hours with either medium alone (lane 1), PMA/αCD28 in the presence (lane 3) or absence of rapamyin (lane 2), PMA/αCD28 in the presence of rapamycin plus okadaic acid (OA; lane 4), or PMAS/αCD28 in the presence of OA (lane 5). After stimulation, cells were divided into 2 groups: one half was used for cellular lysate preparation, and the other half was used to isolate total RNAs. (A) Equal amounts of cellular lysates (35 μg) were used in the immunocomplex kinase assays for JNK-1 using recombinant GST-c-Jun (1-169) as substrate. (B) Equal amounts of RNAs (10 μg) were analyzed by Northern blot analysis using a fragment of IL-2 cDNA as a probe. (C) Graphical representation of the IL-2 mRNA levels quantitated and normalized with 18S ribosomal RNA.

Discussion

Rapamycin treatment of T cells inhibits IL-2 signaling and blocks T-cell proliferation.31 32 In this report we demonstrate that rapamycin also blocks the production of IL-2 by activated human peripheral blood T cells. This effect of rapamycin was not accounted for by autocrine IL-2 signaling for the following reasons. First, we could not detect any Stat5, an IL-2–specific Stat, in PMA/αCD28-treated nuclear extracts in super shift assay, although stat5 was easily detected in the IL-2–treated nuclear extract (Figure2B). Second, if IL-2 signaling were involved in the PMA/αCD28 treatment, then PMA/ionomycin treatment also should have been effected by rapamycin, but this stimulation was unaffected even though a much higher level of IL-2 was produced by PMA/ionomycin treatment (Figure1B,C). The data presented here suggested that the treatment of rapamycin blocked IL-2 production in a pathway-specific manner.

Previous studies have shown that the activation of T cells with αCD3 plus αCD28 triggers pathways that are broadly classified into 2 groups: one is calcium dependent and sensitive to CsA and the other group is calcium independent and resistant to CsA.10 The CsA-resistant pathway has been thought to be responsible for the ineffectiveness of CsA in the treatment of graft-versus-host disease following allogenic bone marrow transplantation.39 To study these pathways separately, one can stimulate T cells either with PMA and αCD28 to mimic the CsA-resistant pathway or with PMA and ionomycin to activate the CsA-sensitive pathway. The data presented here demonstrate that rapamycin treatment blocks the CsA-resistant pathway of T-cell activation, whereas this treatment has no effect on the CsA-sensitive pathway.

One of the first signaling molecules involved in CD28 signaling was shown to be PI3-K.11-13 It has been shown that the serine-threonine kinase Akt, a target of PI3-K, can provide some of the CD28 costimulatory signals, eg, production of IL-2 and IFN-γ, but is unable to restore the production of IL-4 or IL-5 by CD28-deficient mice.48 Interestingly, expression of activated Akt in CD28-deficient mice was also unable to restore the proliferative response to secondary stimulation.48 Those researchers also reported, but data were not shown, that rapamycin did not effect Akt-mediated IL-2 promoter activation. mTOR, the target of rapamycin, has been shown to lie downstream of Akt in different cell types, including T cells.31,52 Because rapamycin inhibited IL-2 production by activated T cells, we wanted to know whether the effect of rapamycin was transcriptional or posttranscriptional. The Northern blot analysis presented here suggested that rapamycin did not have any effect on the transcription of the IL-2 gene, because the effect of rapamycin was not observed until 18 to 24 hours, whereas IL-2 message was detected as early as 2 hours (Figure 2A). The effect of rapamycin on IL-2 transcription was also verified by the transient transfection studies using IL-2 promoter reporter constructs (data not shown). Our data are in agreement with Kane et al48 in that rapamycin does not act at the level of the IL-2 promoter. The data presented in Figure 2C demonstrated that the effect of rapamycin was on PMA/αCD28-mediated IL-2 mRNA stability. These data put mTOR downstream of Akt in PMA/αCD28 signaling in peripheral blood T cells and demonstrate its involvement not in IL-2 transcription but in mRNA stability.

It has been well established that mTOR is a key regulator of translation,34 and 4EBP-1 is a downstream target molecule whose phosphorylation status dictates the initiation of translation.35 The availability of the initiation factor eIF4E is critical for the initiation of translation and is dependent on the phosphorylation status of 4EBP-1. Hypophosphorylated 4EBP1 binds to eIF4E, whereas hyperphosphorylation abrogates this interaction.36 We demonstrate here that the phospho–4EBP-1 induced by PMA/αCD28 treatment was found to be dephosphorylated by rapamycin pretreatment as early as 3 hours after exposure (Figure 4). These data suggested that the earliest effect of rapamycin on PMA/αCD28-mediated IL-2 production might be due to the blockage of IL-2 translation.

The role of JNK in IL-2 message stability has been well documented.49 We demonstrate here that JNK also plays an important role in CsA-resistant PMA/αCD28-mediated IL-2 mRNA stability. JNK has been shown to be activated by PMA/αCD28 by activation of vav and Rac, and this activation of JNK is CsA resistant.18 19 We demonstrate here that the PMA/αCD28-mediated JNK-1 activation is sensitive to rapamycin. Interestingly, the rapamycin effect on JNK-1 activity was not observed until 18 hours, although the kinase activity was detected as early as 15 minutes (Figure 5A). These data along with the fact that rapamycin had no effect on PMA/αCD28-mediated IL-2 transcription suggested that JNK-1 might be involved in PMA/αCD28-induced IL-2 mRNA stability but not in IL-2 transcription. The reason for the late effect of rapamycin on JNK activity is currently under investigation.

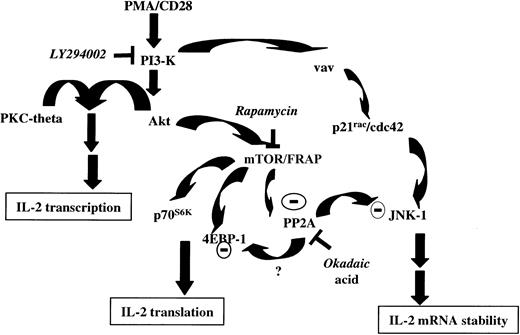

PMA/αCD28 stimulation also activated p38, but that activation was not sensitive to rapamycin treatment, indicating specific involvement of JNK-1 in PMA/αCD28-mediated IL-2 mRNA stability. The role of JNK-1 in IL-2 mRNA stability was further demonstrated by the fact that the treatment with okadaic acid, which reversed the rapamycin-mediated suppression of JNK-1 activity, also blocked the rapamycin-mediated suppression of IL-2 message (Figure 6A,B). These data suggest the involvement of PP2A/PP1 in the suppression of PMA/αCD28-induced JNK-1 activity on rapamycin treatment. Indeed, a similar phenomenon has been reported in the regulation of 4EBP-1 and p70s6k by PP2A during amino acid deprivation.51 In that study, the researchers reported the activation of PP2A on inhibition of mTOR by rapamycin. The inhibition of JNK-1 activity by rapamycin also suggests a linear pathway that includes mTOR and JNK-1. But that pathway may not be the case for the following reason: rapamycin-mediated suppression of mTOR may be responsible for the activation of PP2A/PP1, which in turn inhibits JNK-1 activity. To be in the same linear pathway with JNK-1, mTOR must be active in the presence of rapamycin. It is known that mTOR kinase activity is blocked by rapamycin. Thus, it is possible that JNK-1 activated by the vav/Rac pathway becomes the target of rapamycin-induced PP2A/PP1 (Figure 7). This possibility could also explain why the inhibition of JNK-1 activity by rapamycin is a late event.

Proposed model for signal transduction by PMA/CD28 stimulation.

PI3-K is activated on CD28 ligation. PI3-K then activates Akt by generating phosphatidylinositols. In association with PKC-theta, activated Akt then initiates IL-2 gene transcription. Activated Akt also modulates mTOR/FRAP, which in turn suppresses constitutively active PP2A. mTOR/FRAP is also involved in regulating the activity of p70S6K and 4EBP-1 and thus controlling IL-2 translation. In presence of rapamycin, inhibition of mTOR/FRAP activates PP2A. JNK-1 activated by PI3-K/vav/rac pathway acts to stabilize IL-2 message. Activated JNK-1 becomes the target of dephosphorylation and inactivation by activated PP2A; suppression of JNK-1 activity results in decreased IL-2 mRNA stability. Whether rapamycin-mediated dephosphorylation of 4EBP-1 is mediated by activated PP2A, as it has been shown during amino acid deprivation,51 needs to be determined.

Proposed model for signal transduction by PMA/CD28 stimulation.

PI3-K is activated on CD28 ligation. PI3-K then activates Akt by generating phosphatidylinositols. In association with PKC-theta, activated Akt then initiates IL-2 gene transcription. Activated Akt also modulates mTOR/FRAP, which in turn suppresses constitutively active PP2A. mTOR/FRAP is also involved in regulating the activity of p70S6K and 4EBP-1 and thus controlling IL-2 translation. In presence of rapamycin, inhibition of mTOR/FRAP activates PP2A. JNK-1 activated by PI3-K/vav/rac pathway acts to stabilize IL-2 message. Activated JNK-1 becomes the target of dephosphorylation and inactivation by activated PP2A; suppression of JNK-1 activity results in decreased IL-2 mRNA stability. Whether rapamycin-mediated dephosphorylation of 4EBP-1 is mediated by activated PP2A, as it has been shown during amino acid deprivation,51 needs to be determined.

The inhibitory effect on IL-2 signaling and subsequent blockage in T-cell proliferation by rapamycin has been well documented,31,32 and, because of its immunosuppressive property, rapamycin has been approved for clinical use along with other immunosuppressants.33 The data presented here regarding the inhibition of IL-2 production by rapamycin provide additional information on the mechanism of action of rapamycin in activated T cells. It will be of great interest to identify the physiologically relevant pathways that mimic the PMA/αCD28-mediated CsA-resistant pathway and to examine these pathways for their sensitivity to rapamycin. Indeed, IL-12 has been shown to synergize with CD28 in a CsA-resistant manner.53 The effect of rapamycin on this pathway is currently under investigation. Investigating the effect of rapamycin in vivo in the presence or absence of CsA on the differentiation of T-helper cells and on the development of graft-versus-host disease could greatly enhance our ability to perform allogeneic stem cell transplantation more safely.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, April 17, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2001-11-0062.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Paritosh Ghosh, Lymphocyte Cell Biology Section, Laboratory of Immunology, Gerontology Research Center, National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, 5600 Nathan Shock Dr, Baltimore, MD 21224; e-mail:ghoshp@grc.nia.nih.gov.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal