Platelets undergo a series of actin-dependent morphologic changes when activated by thrombin receptor activating peptide (TRAP) or when spreading on glass. Polymerization of actin results in the sequential formation of filopodia, lamellipodia, and stress fibers, but the molecular mechanisms regulating this polymerization are unknown. The Arp2/3 complex nucleates actin polymerization in vitro and could perform this function inside cells as well. To test whether Arp2/3 regulated platelet actin polymerization, we used recombinant Arp2 protein (rArp2) to generate Arp2-specific antibodies (αArp2). Intact and Fab fragments of αArp2 inhibited TRAP-stimulated actin-polymerizing activity in platelet extracts as measured by the pyrene assay. Inhibition was reversed by the addition of rArp2 protein. To test the effect of Arp2/3 inhibition on the formation of specific actin structures, we designed a new method to permeabilize resting platelets while preserving their ability to adhere and to form filopodia and lamellipodia on exposure to glass. Inhibition of Arp2/3 froze platelets at the rounded, early stage of activation, before the formation of filopodia and lamellipodia. By morphometric analysis, the proportion of platelets in the rounded stage rose from 2.85% in untreated to 63% after treatment with αArp2. This effect was also seen with Fab fragments and was reversed by the addition of rArp2 protein. By immunofluorescence of platelets at various stages of spreading, the Arp2/3 complex was found in filopodia and lamellipodia. These results suggest that activation of the Arp2/3 complex at the cortex by TRAP stimulation initiates an explosive polymerization of actin filaments that is required for all subsequent actin-dependent events.

Introduction

Activation of platelets produces a reproducible sequence of morphologic events, whether in suspension or during spreading on glass: rounding, filopodial projection, attachment, spreading, and ultimately contraction.1-6 These morphologic changes depend on the reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton, including severing of existing filaments, which causes the discoid platelet to round and depends on gelsolin,3,7,8 and polymerization of actin monomers into new filaments.3,9-11 These new actin filaments organize into 4 distinct structures: filopodia, lamellipodia, stress fibers, and a contractile ring.4 Each of these structures performs a different function, and each contains a different complement of actin-binding proteins.4-6

The Arp2/3 complex is likely to regulate the polymerization of actin during shape change in the platelet. Arp2/3 is a 7-member protein complex isolated by poly-proline chromatography from the soil amoeba,Acanthamoeba castellani.12 Although the Arp2 subunit was isolated from human platelets, first by F-actin affinity chromatography4 and later as a member of the Arp2/3 complex that mediates Listeria-induced actin assembly,13 neither its function nor its location in platelets has been previously reported. In vitro, Arp2/3 nucleates actin filament assembly14,15 and is required, together with 2 other proteins, to reconstitute the actin-based motility ofListeria bacteria.16 Arp 2/3 is reported to have at least 2 binding sites for actin: one that binds to the sides of actin filaments and the other that binds to the pointed ends of actin monomers nucleating barbed-end elongation.14,17,18 In vitro, this could produce networks of filaments that branch at 70° angles. In soil ameba and in cultured cells, Arp2/3 is found in the lamellipodia12,15,17 where filaments branch at 70° angles.19 Antibodies to the p34 subunit of Arp2/3 inhibit this branching activity in vitro and in vivo but do not inhibit the incorporation of actin monomer.17 Antibodies to the Arp2, but not the Arp3, subunit inhibit actin-polymerizing activity in extracts of Acanthamoeba.20 Based on correlations between this in vitro behavior and its cellular location, Arp2/3 is considered the best candidate to regulate actin dynamics physiologically at the membrane–cytoplasm interface.21-27

Because platelets are anucleate and are very small, they can neither be transfected nor injected. Permeabilization has been used to load platelets with pyrene-actin to study agonist-stimulated actin polymerization biochemically.3 11 In platelets, actin-polymerizing activity increases in response to the agonist, thrombin receptor activating peptide (TRAP), and 60% of this increase is preserved after permeabilization with detergent. We discovered that permeabilized platelets undergo normal morphologic events when exposed to glass: they adhere and reorganize their actin filaments into the typical 4 structures. We have used these techniques together with a set of molecular tools, including new inhibitory antibodies generated against recombinant Arp2 (rArp2), to test the role of Arp2/3 in actin dynamics and in the morphologic events of surface-activated shape change.

Materials and methods

Constructs and antibodies

Full-length Arp228 (GenBank accession number 71789) was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers with aKpnI site in the first 6 base pairs of the 5′ primer (GGTACCATGGACAGATCGAAGGG) and Psp1 and HindIII sites in the tail of the 3′ primer (reverse complement: (CCCGGGAAGCTTCTAGTGACTGATCTTTTG) from a clone containing the Arp2 cDNA. PCR products were ligated in pCR2.1 vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), excised with KpnI and BamH1, and ligated into the same sites in frame in the pQE30 vector (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Recombinant Arp2 containing 6 histidine tags was overexpressed in bacteria, purified, and confirmed by peptide sequencing. Gel slices of purified protein were used as immunogen in rabbits according to our protocols.4,5 Serum from 3 different rabbits was affinity purified separately by affinity column chromatography against rArp2. The final preparation contained 1 mg/mL affinity-purified antibody. Preimmune antibodies from the same rabbit were purified by protein A affinity chromatography and were used in parallel. In any given experiment, the preimmune antibodies were from the same rabbit as the immune antibody preparation. Fab fragments were prepared by papain digestion of purified antibodies, and the Fc fragment was removed by passage through a protein A column according to established protocols.29

Affinity-purified antipeptide rabbit antibodies against p34 were a gift from John Condeelis.17 Rabbit anti-kaptin was raised in our laboratory,5 and mouse anti-actin is from the monoclonal hybridoma JLA-4.4,5 Western blotting was performed as previously described.4-6

Quantification of the amount of Arp2 in platelets was performed as follows. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was used on the day of draw as described.4-6 The platelet count was determined (usually approximately 5.5 × 1011 platelets/U). After washing, the platelets from one unit of PRP were resuspended in gel sample buffer at a volume calculated to give a final concentration of 2.5 × 1011 platelets/mL. Various amounts of platelets were loaded into separate lanes on sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) in parallel with different amounts of purified rArp2 and were probed for Arp2 by Western blotting. The amount of Arp2 in the platelet sample was determined by comparing the density of resultant bands in the platelet samples with the density of bands containing a known amount of rArp2 using the GelDoc with Quantity One software (BioRad, Hercules, CA). The amount of Arp2 molecules per platelet was determined by dividing the amount of Arp2 detected on the blot by the number of platelets loaded on the gel. Molar concentration was determined by assuming that the average volume of a platelet was 7 fL.30 It required 1.6 × 108 platelets (6 μL) per platelet sample to detect a band on the blot, with an anti-Arp2 detection limit of 15 ng.

Precipitation of Arp2 with αArp2-conjugated protein A beads

Protein A beads were conjugated to affinity purified αArp2 or to preimmune antibodies from the same rabbit29 and were used to detect endogenous Arp2 in platelet extracts. Platelet extracts were prepared as described.4-6 Briefly, washed platelets were lysed by 1:1 dilution in lysis buffer containing 2% nonionic detergent and were sonicated briefly. Extracts (100 μL of 35 mg/mL protein) were incubated with 10 μL antibody-coupled beads for 4 hours at 4°C. Beads were collected by centrifugation and washed in lysis buffer. Proteins from equal volumes of supernatant and pellet were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to Western blots, and probed sequentially with αArp2 (1:1000), αp34 (1:500), and αactin (1:5,000), followed by horseradish peroxidase secondary antibody (antirabbit, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA; anti–mouse IgM, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Blots were imaged by chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ).

Pyrene actin polymerization kinetics

Pyrene actin (10% labeled; Cytoskeleton, Denver, CO) was aliquoted, lyophilized from G-buffer (5 mM Tris [pH 8.1], 0.2 mM CaCl2, 0.2 mM adenosine triphosphate [ATP], 0.5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]), and stored in liquid nitrogen. On the day of use, the actin was thawed, incubated at 10 μM in water for 4 hours at room temperature, and centrifuged for 1.5 hours at 100 000g. Immediately before each experiment, this stock of actin was diluted to 1.3 μM in 200 μL polymerization buffer (100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1 EGTA, 10 mM Tris [pH 7.0], 0.5 mM ATP, 0.5 mM DTT). The cuvette containing the diluted actin was placed in the fluorometer for a baseline reading before the platelet suspension was added.

Washed platelets were resuspended in platelet buffer (145 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 0.5 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM glucose, 10 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], and 0.3% globin-free bovine serum albumin more than 99% pure) and were maintained at 37°C. For sonication, 90 μL platelets were treated with 10 μL PHEM buffer (60 mM PIPES [pH 6.9], 25 mM HEPES [pH 6.9], 10 mM EGTA, 2 mM Mg Cl2, and protease inhibitors) with or without 1 μL of 1.2 mM TRAP (Sigma, St Louis, MO) as described.6Sonicates were prepared individually just before each assay, antibodies were added immediately thereafter, and the suspension was injected into the cuvette containing pyrene-actin.

For Triton permeabilization, a 1:10 dilution of 7.5% Triton X-100 with and without TRAP (1 μL of 1.2 mM) was added to the PHEM buffer, and no sonication was performed. Otherwise, the procedure was essentially the same as for sonication. For sonication or Triton permeabilization, fewer than 30 seconds elapsed between TRAP stimulation and measurement in the fluorometer.

After platelets were added, actin polymerization was measured for 10 to 20 minutes at 1-second intervals with excitation at 365 and emission 407 nm in a luminescence spectrometer (model LS50B; Perkin-Elmer, Wellesley, MA). Data were collected using the Winlab program and were analyzed with Microsoft Excel.

Each series of experiments was performed on the same day with the same preparations of actin and platelets, beginning with baseline measurements of actin alone, and of platelets with or without TRAP.

Morphometric analysis of αArp2 on shape change

Brief permeabilization with low amounts of Triton was used to load antibody into platelets before exposing them to glass. PRP (3 μL) diluted with platelet buffer to approximately 0.6 to 1.2 × 106 platelets/mL was treated with a 1/10 volume of 0.75% Triton in PHEM buffer with and without antibodies for 1 minute before mounting on a glass coverslip. The Triton concentration was immediately diluted by flooding the coverslip with 500 μL Tyrode solution (145 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 2 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM Na2PO4, 1.8 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM glucose).4 PRP was also applied to coverslips without permeabilization. After 20 minutes, the coverslip was fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PHEM buffer with 0.25% Triton containing 1/50 dilution of 3 μM fluorescein isothiocyanate–phalloidin (FITC–phalloidin; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR).4-6 Primary antibodies were detected by postfixation staining with Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (Cy3 is red; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories).

Immunofluorescence to determine endogenous Arp2/3 location

PRP without permeabilization was dotted onto glass coverslips, and the coverslip was flooded with Tyrode buffer as described above. After 20 minutes, spread platelets were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PHEM buffer containing a 1/50 dilution of FITC–phalloidin with or without 0.25% Triton for 20 minutes at room temperature. Fixed platelets were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma) in phosphate-buffered saline with 0.1% Triton X100. Coverslips were then stained with αArp2 followed by secondary antibody. Images were obtained on a Nikon fluorescence microscope equipped with an RT-Spot liquid crystal digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Starling Heights, IL).

Results

Generation of rArp2 and anti-Arp2 antibodies

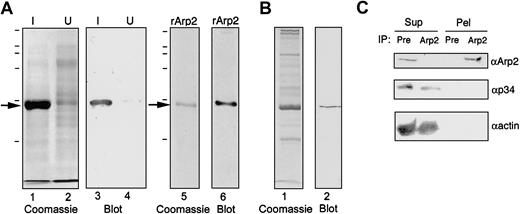

To develop tools to test the role of Arp2/3 in platelet actin dynamics, we cloned the Arp2 subunit and raised antibodies to full-length rArp2. Immunization of 8 different rabbits produced 3 with high-titer antiserum that was sensitive and specific for Arp2. We characterized the αArp2 antibodies against bacterially expressed rArp2 (Figure 1A) and against platelet extracts (Figure 1B-C). Affinity-purified αArp2 detected a single band in induced bacterial homogenates (Figure 1A, lane 3) and recognized purified rArp2 (Figure 1A, lane 6). The antibody could detect as little as 15 ng purified rArp2. In platelet extracts, αArp2 detected a single band of the appropriate molecular weight (44 kd) (Figure 1B).

Characterization of αArp2 antibodies.

(A) Affinity-purified αArp2 is specific for rArp2 in bacterial homogenates. Homogenates of IPTG-induced (I, lanes 1 and 3) or uninduced (U, lanes 2 and 4) M15 bacteria carrying the pQE30/Arp2 plasmid were electrophoresed in parallel. Gels were stained with Coomassie blue (lanes 1 and 2) or were Western blotted and probed with affinity-purified αArp2 antibodies (lanes 3 and 4). Coomassie blue–staining of purified recombinant Arp2 demonstrated a single band (lane 5) that was recognized by the affinity-purified antibody in Western blot (lane 6). In this case, 0.5 μg rArp2 has been loaded on the gel. (B) Detection of Arp2 in platelets by Western blot analysis. Platelet proteins were analyzed by Coomassie gels (lane 1) and for the presence of αArp2 in Western blots (lane 2). (C) Detection of native Arp2 in platelet extracts. Platelet extracts were incubated with protein A beads conjugated to either αArp2 (Arp2) or preimmune (Pre) antibodies from the same rabbit as αArp2, and the beads were collected by centrifugation. Supernatants (Sup) and pellets (Pel) were probed by Western blot for Arp2 (αArp2; top panel), p34, another Arp2/3 subunit (αp34; middle panel) or actin (αactin; lower panel). Note that Arp2 is removed from the extract and appears in the pellet after treatment with αArp2 beads but not with preimmune antibodies. Neither p34 nor actin sediments with the αArp2 beads.

Characterization of αArp2 antibodies.

(A) Affinity-purified αArp2 is specific for rArp2 in bacterial homogenates. Homogenates of IPTG-induced (I, lanes 1 and 3) or uninduced (U, lanes 2 and 4) M15 bacteria carrying the pQE30/Arp2 plasmid were electrophoresed in parallel. Gels were stained with Coomassie blue (lanes 1 and 2) or were Western blotted and probed with affinity-purified αArp2 antibodies (lanes 3 and 4). Coomassie blue–staining of purified recombinant Arp2 demonstrated a single band (lane 5) that was recognized by the affinity-purified antibody in Western blot (lane 6). In this case, 0.5 μg rArp2 has been loaded on the gel. (B) Detection of Arp2 in platelets by Western blot analysis. Platelet proteins were analyzed by Coomassie gels (lane 1) and for the presence of αArp2 in Western blots (lane 2). (C) Detection of native Arp2 in platelet extracts. Platelet extracts were incubated with protein A beads conjugated to either αArp2 (Arp2) or preimmune (Pre) antibodies from the same rabbit as αArp2, and the beads were collected by centrifugation. Supernatants (Sup) and pellets (Pel) were probed by Western blot for Arp2 (αArp2; top panel), p34, another Arp2/3 subunit (αp34; middle panel) or actin (αactin; lower panel). Note that Arp2 is removed from the extract and appears in the pellet after treatment with αArp2 beads but not with preimmune antibodies. Neither p34 nor actin sediments with the αArp2 beads.

Quantitative Western blot analysis comparing purified rArp2 with platelet extracts revealed that the concentration of Arp2 in platelets is 0.3 μM, or 1300 molecules per platelet. This amount is sufficient to account for all the new free actin filament ends (410-570 barbed ends/platelet) produced during activation,3,11,31 even if only half the Arp2/3 is activated. This is significantly less protein than VASP or gelsolin, which are estimated at 5 μM each,6,31,32 and this amount is consistent with the yield of Arp2/3 complex obtained from platelets in purification protocols.13

Arp2 was depleted from Triton-treated, sonicated platelet extracts by incubation with αArp2-conjugated protein A beads (Figure 1C). These extraction conditions were originally designed to depolymerize actin while preserving many other protein–protein interactions.4 5 Extracts were incubated with either αArp2- or preimmune–conjugated protein A beads, and the beads and supernatant were separated by centrifugation. By Western blot, Arp2 was cleared from the extract after incubation with αArp2 beads and was detected in the pellet containing the beads (Figure 1C, top panel). In contrast, Arp2 remained in the supernatant after treatment with preimmune beads. Reprobing of the same blot for p34 (another Arp2/3 subunit) or for actin revealed both proteins in the supernatant and not pelleted with αArp2 (Figure 1C, middle and lower panels). This demonstrated that αArp2 recognized native Arp2 in solution.

Effect of Arp2 inhibition on platelet actin-polymerizing activity

The effect of αArp2 on actin-polymerizing activity of platelet extracts was measured in the pyrene assay. To perform this assay, platelets must be permeabilized sufficiently for enough pyrene-labeled actin to be loaded for detection in the fluorometer.8 11Such permeabilization also allows entry of the αArp2 antibody, thus permitting measurements of the effect of antibody on actin polymerization.

TRAP produced a robust increase in actin-polymerizing activity in platelets permeabilized by sonication (6.3-fold, Figure2A, C) or detergent (Figure 2B). This TRAP-stimulated increase was exquisitely sensitive to αArp2 (Figure 2A-C). Addition of αArp2 (0.01 mg/mL in Figure 2A; or 15 μg/mL in Table 1) resulted in a 71% decrease in the polymerization rate during the initial 2 minutes after TRAP stimulation. This inhibitory effect was not seen with a different affinity-purified rabbit antibody raised against another actin-binding protein, kaptin,5 in which polymerization rates were 93.6% of untreated (Figure 2A,C; Table 1). Treatment with αp34 had only a slight inhibitory effect, with rates 82% of untreated (Figure2B; Table 1) as expected.17

αArp2 inhibits TRAP-stimulated actin-polymerizing activity.

Platelets were stimulated with TRAP and were permeabilized with and without antibody as indicated. Actin-polymerizing activity was measured immediately after antibody addition. For each graph, all tracings are from the same preparations of platelets and actin preparation obtained on the same day. Results are presented in arbitrary units (au), as is standard in the field. Final fluorescence intensity with nonstimulated platelets (no TRAP) was defined as 10 au. Platelet extracts always produced at least a 20% increase over actin alone (not shown). (A) Effect of αArp2 on actin-polymerizing activity of TRAP-stimulated sonicated platelets. TRAP (top tracing) increased actin-polymerizing activity 5-fold over nonstimulated platelets (lowest tracing) in samples permeabilized by sonication. Affinity-purified αArp2 added to the TRAP-stimulated platelets decreased the initial rate and the extent of polymerization, whereas anti-kaptin had little to no effect at the same concentration (0.01 mg/mL, 0.7 μM) used for αArp2. (B) Effect of αArp2 and αp34 on actin-polymerizing activity of TRAP-stimulated Triton-permeabilized platelets. Platelets were permeabilized by either sonication, as in Figure 1A, or with Triton and antibody added as indicated (αArp2 and αp34 were at 15 μg/mL [0.1 μM]). A similar increase in fluorescence was obtained with TRAP stimulation, whether platelets were permeabilized by sonication (sonic) or Triton (Tx). The increase in the initial rate of polymerization after TRAP stimulation was blocked by αArp2 regardless of whether permeabilization was with sonication or Triton. Less of an effect on TRAP-stimulated activity was detected with αp34. (C) Effect of Fab fragments of αArp2 on actin-polymerizing activity of TRAP-stimulated platelets. Platelets stimulated with TRAP and permeabilized as in Figure 1A were treated with antibodies as indicated at the following concentrations: anti-kaptin (0.1 μM), αArp2 + rArp2 (0.1 and 0.5 μM, respectively), Fab fragments of αArp2 (0.12 and 0.44 μM), and intact αArp2 from a different rabbit (0.1 μM). (D) Effect of αArp2 on actin-polymerizing activity of nonstimulated platelets. αArp2 was added (as indicated) to nonstimulated platelets immediately after sonication. Note that the arbitrary units (au) on the y-axis of the graph was expanded to increase the sensitivity to demonstrate the effect of the antibody on the lower level of activity present in nonstimulated platelets. (E) Dose dependence of αArp2 inhibition. The final fluorescence of representative experiments treated with increasing amounts of αArp2 or preimmune IgG (pre-IgG) is compared. A similar graph could be drawn for either anti-p34 or anti-kaptin as control antibody (Table 1). Experiments were normalized by setting the final fluorescence of parallel preparations, measured in the absence of antibody, at 100%, which allowed comparison of the low level of activity in nonstimulated platelets with the much higher activity after TRAP. Thus, results from TRAP-stimulated and nonstimulated experiments could be superimposed on the same graph.

αArp2 inhibits TRAP-stimulated actin-polymerizing activity.

Platelets were stimulated with TRAP and were permeabilized with and without antibody as indicated. Actin-polymerizing activity was measured immediately after antibody addition. For each graph, all tracings are from the same preparations of platelets and actin preparation obtained on the same day. Results are presented in arbitrary units (au), as is standard in the field. Final fluorescence intensity with nonstimulated platelets (no TRAP) was defined as 10 au. Platelet extracts always produced at least a 20% increase over actin alone (not shown). (A) Effect of αArp2 on actin-polymerizing activity of TRAP-stimulated sonicated platelets. TRAP (top tracing) increased actin-polymerizing activity 5-fold over nonstimulated platelets (lowest tracing) in samples permeabilized by sonication. Affinity-purified αArp2 added to the TRAP-stimulated platelets decreased the initial rate and the extent of polymerization, whereas anti-kaptin had little to no effect at the same concentration (0.01 mg/mL, 0.7 μM) used for αArp2. (B) Effect of αArp2 and αp34 on actin-polymerizing activity of TRAP-stimulated Triton-permeabilized platelets. Platelets were permeabilized by either sonication, as in Figure 1A, or with Triton and antibody added as indicated (αArp2 and αp34 were at 15 μg/mL [0.1 μM]). A similar increase in fluorescence was obtained with TRAP stimulation, whether platelets were permeabilized by sonication (sonic) or Triton (Tx). The increase in the initial rate of polymerization after TRAP stimulation was blocked by αArp2 regardless of whether permeabilization was with sonication or Triton. Less of an effect on TRAP-stimulated activity was detected with αp34. (C) Effect of Fab fragments of αArp2 on actin-polymerizing activity of TRAP-stimulated platelets. Platelets stimulated with TRAP and permeabilized as in Figure 1A were treated with antibodies as indicated at the following concentrations: anti-kaptin (0.1 μM), αArp2 + rArp2 (0.1 and 0.5 μM, respectively), Fab fragments of αArp2 (0.12 and 0.44 μM), and intact αArp2 from a different rabbit (0.1 μM). (D) Effect of αArp2 on actin-polymerizing activity of nonstimulated platelets. αArp2 was added (as indicated) to nonstimulated platelets immediately after sonication. Note that the arbitrary units (au) on the y-axis of the graph was expanded to increase the sensitivity to demonstrate the effect of the antibody on the lower level of activity present in nonstimulated platelets. (E) Dose dependence of αArp2 inhibition. The final fluorescence of representative experiments treated with increasing amounts of αArp2 or preimmune IgG (pre-IgG) is compared. A similar graph could be drawn for either anti-p34 or anti-kaptin as control antibody (Table 1). Experiments were normalized by setting the final fluorescence of parallel preparations, measured in the absence of antibody, at 100%, which allowed comparison of the low level of activity in nonstimulated platelets with the much higher activity after TRAP. Thus, results from TRAP-stimulated and nonstimulated experiments could be superimposed on the same graph.

Effect of antibodies on the initial rate of polymerization (δ au/δt)

| Treatment . | Ratio of the rates of polymerization (treatment/TRAP alone) . | Fold increase in rate of polymerization (TRAP + treatment/no TRAP) . |

|---|---|---|

| No TRAP | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 1.0 |

| TRAP | 1.0 | 6.33 ± 0.6 |

| TRAP + αArp2 (15 μg/mL or 0.1 μM) | 0.29 ± 0.04 | 2.1 ± 0.5 |

| TRAP + αp34 (15 μg/mL or 0.1 μM) | 0.82 ± 0.07 | 4.6 ± 0.5 |

| TRAP + αkaptin (15 μg/mL or 0.1 μM) | 0.936 ± 0.1135 | 5.015 ± 0.256 |

| TRAP + αArp2 (Fab) | ||

| 0.50 μg/mL (0.01 μM) | 0.55 | 4.0 |

| 5.00 μg/mL (0.10 μM) | 0.16 | 2.3 |

| 20.0 μg/mL (0.40 μM) | 0.13 | 1.9 |

| Treatment . | Ratio of the rates of polymerization (treatment/TRAP alone) . | Fold increase in rate of polymerization (TRAP + treatment/no TRAP) . |

|---|---|---|

| No TRAP | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 1.0 |

| TRAP | 1.0 | 6.33 ± 0.6 |

| TRAP + αArp2 (15 μg/mL or 0.1 μM) | 0.29 ± 0.04 | 2.1 ± 0.5 |

| TRAP + αp34 (15 μg/mL or 0.1 μM) | 0.82 ± 0.07 | 4.6 ± 0.5 |

| TRAP + αkaptin (15 μg/mL or 0.1 μM) | 0.936 ± 0.1135 | 5.015 ± 0.256 |

| TRAP + αArp2 (Fab) | ||

| 0.50 μg/mL (0.01 μM) | 0.55 | 4.0 |

| 5.00 μg/mL (0.10 μM) | 0.16 | 2.3 |

| 20.0 μg/mL (0.40 μM) | 0.13 | 1.9 |

Average (mean) change in au at 120 seconds ± SEM.

Effect of αArp2 on the rate of actin polymerization in the first 120 seconds (intensity change per second) was analyzed for 24 different experiments. Data from platelets permeabilized by sonication or by Triton were combined because results were similar. Experiments from different platelet preparations were normalized by setting the rate of increase in fluorescence (intensity units/sec) to 1.0 either for TRAP-stimulated platelets (first column) or for nonstimulated preparations (second column). For each individual measurement, the rate ratio (rate in treated sample/rate in TRAP or rate in nonstimulated samples from the same preparation) was calculated. The average rate of each treatment was derived by dividing the sum of the rate ratios for each individual measurement by the number of measurements. Note the dose response for Fab fragments: increasing amounts of Fab fragments decrease the rate of actin polymerization compared with TRAP alone.

Three additional experiments confirmed the specificity of the αArp2 antibody in inhibiting TRAP-stimulated actin polymerization. First, Fab fragments of αArp2 have similar inhibitory effects, demonstrating that inhibition is not dependent on the formation of large antibody–antigen complexes (Figure 2C; Table 1). Second, affinity-purified αArp2 from another rabbit also inhibited polymerization (αArp2; Figure 2C), showing that inhibition is not caused by some unique component in a particular preparation of antibody. Finally, pretreatment of the antibody with rArp2 protein completely abolished the inhibitory effect of αArp2 (rArp2, Figure2C). This demonstrates that αArp2 inhibition is dependent on interaction of the antibody with Arp2 protein.

Because Arp2/3 is expected to increase the initial rate of polymerization, we calculated the rates during the first 120 seconds and compared the effect of different treatments (Table 1). Only αArp2 and its Fab fragments—not αkaptin or αp34—caused a reproducible decrease in the initial polymerization rate. After treatment with Fab fragments at a final concentration of 0.40 μM, the actin polymerization rate was decreased to 13% of the rate in untreated platelets.

In the absence of TRAP, αArp2 had less effect on the low level of actin-polymerizing activity (Figure 2D), whereby at least 10-fold more antibody was required (compare 0.10 mg/mL without TRAP in Figure 2D with 0.01 mg/mL with TRAP in Figure 2A). The αArp2-sensitive activity in nonstimulated preparations could represent those platelets that have already been activated during preparation. The extent of inhibition was dependent on the concentration of αArp2 antibody in either TRAP-stimulated or nonstimulated platelets (Figure 2E). In contrast, preimmune IgG (Figure 2E, pre-IgG) had little effect on either preparation, even at the highest concentrations.

Adherence and spreading of permeabilized platelets on glass

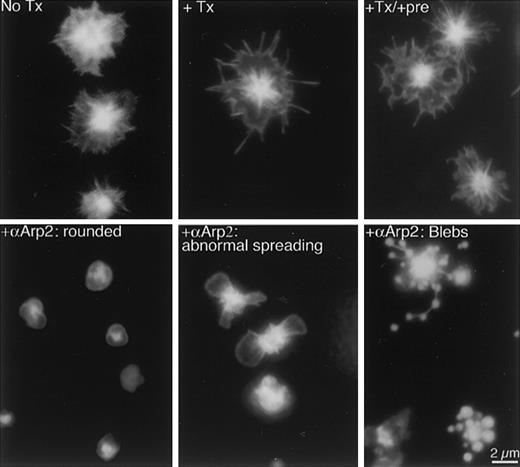

To examine whether the formation of particular actin structure(s) such as filopodia and lamellipodia requires Arp2/3 activity, we developed a technique to load platelets with αArp2 and then to observe the morphology of actin after spreading on glass (Figure 3). Platelets in plasma were exposed briefly to detergent with or without antibody, mounted on glass, and rapidly diluted with an approximately 500-fold excess of Tyrode solution. After spreading, platelets were fixed and stained for F-actin.

αArp2 inhibits filopodia and lamellipodia formation during spreading on glass.

Platelets were either directly spread on glass in plasma or were permeabilized briefly first with or without antibodies, and then mounted on glass. After 20 minutes, adherent platelets were fixed in the presence of FITC–phalloidin to stabilize and stain the F-actin. Top row of micrographs shows representative examples of spread platelets under 3 control conditions: no treatment (No Tx), permeabilized (+Tx), and permeabilized and loaded with preimmune antibodies (+Tx/+pre). The lower row of micrographs shows representative examples of platelets permeabilized and loaded with αArp2 before exposure to glass (+αArp2). Typical effects are frozen at the rounded stage (left panel), abnormal lamellipodia (middle panel), and blebbing (right panel).

αArp2 inhibits filopodia and lamellipodia formation during spreading on glass.

Platelets were either directly spread on glass in plasma or were permeabilized briefly first with or without antibodies, and then mounted on glass. After 20 minutes, adherent platelets were fixed in the presence of FITC–phalloidin to stabilize and stain the F-actin. Top row of micrographs shows representative examples of spread platelets under 3 control conditions: no treatment (No Tx), permeabilized (+Tx), and permeabilized and loaded with preimmune antibodies (+Tx/+pre). The lower row of micrographs shows representative examples of platelets permeabilized and loaded with αArp2 before exposure to glass (+αArp2). Typical effects are frozen at the rounded stage (left panel), abnormal lamellipodia (middle panel), and blebbing (right panel).

Permeabilization alone did not alter adherence to the glass. The same average number of platelets adhered with or without permeabilization (19.9 ± 7.6 and 19.5 ± 6.5 platelets per high-power field, respectively). The presence of any antibody increased adherence, regardless of antibody type (27.7 ± 5.2 platelets per high-power field after preimmune treatment and 28.2 ± 8.0 after αArp2 treatment). Permeabilization did not cause a detectable loss of Arp2/3, as determined by postfixation immunostaining (data not shown).

Permeabilized platelets exhibited all the typical actin structures as imaged by FITC–phalloidin staining (Figure 3, top row, middle panel), though some minor variations were observed. Filopodia seemed longer, and the diffuse staining in the cytoplasm was decreased. Permeabilized platelets treated with preimmune antibodies also formed filopodia, lamellipodia, and stress fibers indistinguishable from platelets permeabilized without antibody (Figure 3, top row, right panel).

Morphologic effect of Arp2 inhibition on platelet shape change

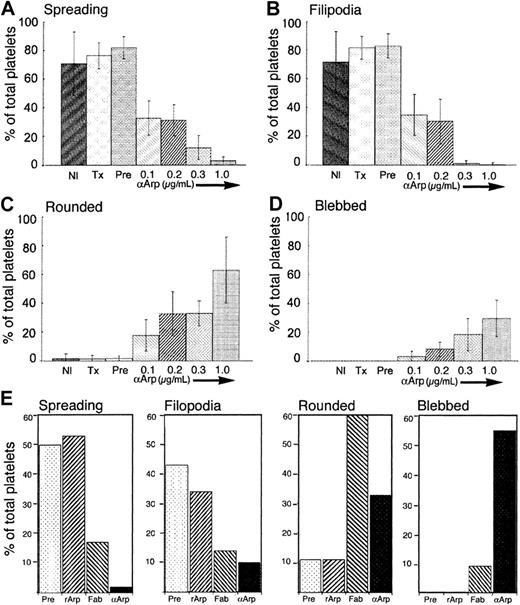

Inactivation of Arp2/3 had a striking effect on morphology and on actin structures (Figure 3, lower row). Four dose-dependent effects of αArp2 on morphology were observed and quantified: (1) decreased proportion of spread platelets; (2) decreased proportion with filopodia; (3) increased proportion in the rounded stage; and (4) presence of a novel morphology, blebbing, not seen in the absence of αArp2. These effects were quantitative and αArp2 dose dependent (Figure 4). Antibodies from 2 different rabbits were each used in parallel with the preimmune antibodies from the same rabbit.

Morphometric analysis of the effects of αArp2 on filopodia and lamellipodia and on morphology during spreading on glass.

(A-D) Effect of intact antibody on platelet spreading. Nl indicates untreated (n = 259 platelets); Tx, permeabilized only (n = 391); Pre, permeabilized and loaded with 1.0 μg/mL antibodies from preimmune serum from the same rabbit (n = 444); and 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, and 1.0, permeabilized and loaded with different concentrations of αArp2, in μg/mL, final concentration (n = 423, n = 385, n = 512, n = 609, respectively). (E) Effect of Fab fragments and rArp2 on platelet spreading. Platelets were permeabilized as in Figure3 and treated as follows: Pre indicates preimmune antibodies from the same rabbit (1μg/mL); rArp2, αArp2 and recombinant Arp2 protein (1 μg/mL and 5 μg/mL, respectively); Fab, Fab fragments of αArp2 (1 μg/mL); and αArp2, intact αArp2 antibody (1 μg/mL). Note that Fab fragments freeze 60% of the platelets in the rounded stage, whereas pretreatment of the antibody with rArp2 protein eliminates this effect. Blebbing was seen with intact antibody and with Fab fragments, though less frequently with Fab fragments.

Morphometric analysis of the effects of αArp2 on filopodia and lamellipodia and on morphology during spreading on glass.

(A-D) Effect of intact antibody on platelet spreading. Nl indicates untreated (n = 259 platelets); Tx, permeabilized only (n = 391); Pre, permeabilized and loaded with 1.0 μg/mL antibodies from preimmune serum from the same rabbit (n = 444); and 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, and 1.0, permeabilized and loaded with different concentrations of αArp2, in μg/mL, final concentration (n = 423, n = 385, n = 512, n = 609, respectively). (E) Effect of Fab fragments and rArp2 on platelet spreading. Platelets were permeabilized as in Figure3 and treated as follows: Pre indicates preimmune antibodies from the same rabbit (1μg/mL); rArp2, αArp2 and recombinant Arp2 protein (1 μg/mL and 5 μg/mL, respectively); Fab, Fab fragments of αArp2 (1 μg/mL); and αArp2, intact αArp2 antibody (1 μg/mL). Note that Fab fragments freeze 60% of the platelets in the rounded stage, whereas pretreatment of the antibody with rArp2 protein eliminates this effect. Blebbing was seen with intact antibody and with Fab fragments, though less frequently with Fab fragments.

Anti-Arp2 loading increased the proportion of rounded platelets in a dose-dependent manner (2.85%, 22%, 27%, 32%, and 63% for 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, and 1 μg/mL, respectively), with commensurate decreases in the proportion that had produced filopodia or spread (Figure 4). In the few αArp2-treated platelets with lamellipodia, spreading was abnormal (Figure 3, lower row, middle panel; Figure 4A). The decrease in numbers of platelets with filopodia was remarkable, with less than 5% of platelets showing any of these structures at αArp2 concentrations of only 0.3 μg/mL. In contrast, after 20 minutes of exposure to glass, more than 80% of preimmune-treated platelets had spread or produced filopodia, and only a small proportion of these (2.85%) remained in the rounded stage (Figure 4C). Platelets permeabilized with or without preimmune antibodies resembled untreated preparations.

The proportion of platelets with blebs, which are never found in control preparations, increased in direct relationship to the amount of αArp2 (2%, 7%, 22%, 37%, and 57% for 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, and 1.0 μg αArp2, respectively) (Figure 3, lower right panel; Figure 4D-E). The phalloidin staining of these blebs indicated that they must have contained filamentous actin, though the filaments were not organized into normal structures (Figure 3, lower right panel).

Fab fragments of αArp2 had similar effects, freezing most platelets in the rounded early stage of activation (Figure 4E). Addition of rArp2 protein reversed these effects. Blebbed platelets were also found after treatment with αArp2 Fab fragments, but the blebs were smaller and fewer platelets were affected (Figure 4E, last panel).

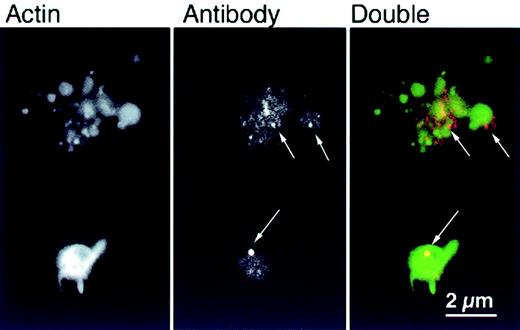

The efficiency of permeabilization was determined by staining platelets with secondary antibody after fixation (Figure5). Primary antibody was detected in 79% of platelets permeabilized in the presence of preimmune antibodies and 76% of those treated with αArp2. By immunofluorescence, secondary antibody staining of platelets loaded with intact αArp2 produced bright dots of varying sizes irregularly located in the platelet cytoplasm and separate from actin filaments (Figure 5, arrows). In platelets loaded with Fab fragments, the staining was also separated from the actin filaments but was more evenly distributed in the cytoplasm (data not shown).

αArp2 antibody is detected in the cytoplasm after permeabilization.

Representative examples of platelets permeabilized, loaded with αArp2, activated on glass, and fixed as in Figure 3. After fixation, platelets were stained with Cy3-labeled secondary antibody to determine whether the primary antibody gained access to the cytoplasm during permeabilization. Staining for αArp2 (red) and actin filaments with FITC–phalloidin (green) demonstrates diffuse speckling in the cytoplasm with some larger aggregates of antibody (arrows).

αArp2 antibody is detected in the cytoplasm after permeabilization.

Representative examples of platelets permeabilized, loaded with αArp2, activated on glass, and fixed as in Figure 3. After fixation, platelets were stained with Cy3-labeled secondary antibody to determine whether the primary antibody gained access to the cytoplasm during permeabilization. Staining for αArp2 (red) and actin filaments with FITC–phalloidin (green) demonstrates diffuse speckling in the cytoplasm with some larger aggregates of antibody (arrows).

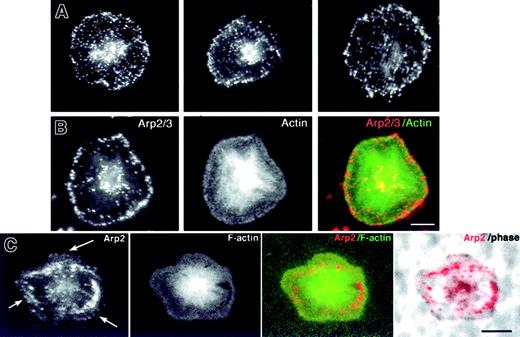

Location of Arp2/3 in normal platelets during spreading on glass

We used double-label immunofluorescence to compare the normal location of Arp2/3 with that of filamentous actin (Figure6). Platelets were first allowed to spread and then were fixed with paraformaldehyde in buffer with or without detergent. Fixation without detergent preserves a large pool of Arp2/3 that is lost when fixation includes Triton, whereas this pool is extracted in fixatives that include detergent.33 Thus, the timing of exposure to detergent allowed us to distinguish between extractable and actin-bound Arp2/3 in spread platelets.

Location of endogenous Arp2/3 in spread platelets.

(A) Three different spread platelets fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde containing 0.25% Triton and stained with αArp2. Arp2/3 displays a speckled cytoplasmic staining and a row of immunofluorescent dots at the periphery. (B) Double label of a single platelet fixed as in panel A and stained for Arp2/3 with αp34 (Cy3, red) and for actin filaments (FITC–phalloidin, green). Superimposition of the double label shows Arp2/3 at the periphery. Bar = 2 μm. (C) Triple image of a single platelet fixed without detergent to permit imaging by phase microscopy and then stained with αArp2 (red) and phalloidin (green). Note that Arp2/3 is found in a bright arc internal to the actin frill. Arrows indicate weak staining at the outermost edge of the lamellipodia. Also note that the platelet contours imaged by phalloidin correspond to those imaged by phase microscopy. Bar = 2 μm.

Location of endogenous Arp2/3 in spread platelets.

(A) Three different spread platelets fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde containing 0.25% Triton and stained with αArp2. Arp2/3 displays a speckled cytoplasmic staining and a row of immunofluorescent dots at the periphery. (B) Double label of a single platelet fixed as in panel A and stained for Arp2/3 with αp34 (Cy3, red) and for actin filaments (FITC–phalloidin, green). Superimposition of the double label shows Arp2/3 at the periphery. Bar = 2 μm. (C) Triple image of a single platelet fixed without detergent to permit imaging by phase microscopy and then stained with αArp2 (red) and phalloidin (green). Note that Arp2/3 is found in a bright arc internal to the actin frill. Arrows indicate weak staining at the outermost edge of the lamellipodia. Also note that the platelet contours imaged by phalloidin correspond to those imaged by phase microscopy. Bar = 2 μm.

Arp2/3 was detected at the edge of the lamellipodium of spread platelets fixed in the presence of detergent, as has been reported for other cells fixed this way (Figure 6).12,15,17,19 33Superimposition of images of the spread platelet double labeled for Arp2 (Figure 6B, red) and F-actin (Figure 6B, green) shows that Arp2/3 was coincident in most places with the actin frill of the lamellipodium. To determine whether the actin frill was at the edge of the platelet, phase microscopy was needed. However, when detergent was included in the fixative, effective imaging by phase microscopy was difficult. Therefore, we fixed platelets without detergent, double labeled them for F-actin (Figure 6C, green, FITC–phalloidin) and for αArp2 (Figure 6C, red, Cy3), and imaged them by phase microscopy and fluorescence microscopy. Phalloidin staining coincided with the phase image; thus phalloidin staining was a reliable indicator of the platelet surface contours. Arp2/3 staining was brighter than in platelets fixed in the presence of detergent. Under these conditions, a soluble pool of Arp2/3 was retained that lay in arcs internal to the lamellipodia. This signal was so bright that it hindered detection of the weaker staining of Arp2/3 at the leading edge (Figure 6C, arrows), and was also brighter than the green phalloidin signal.

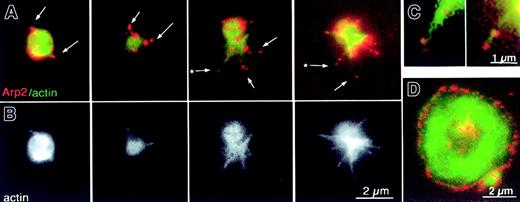

Platelets captured during early stages of activation revealed a relationship between Arp2/3 location and filopodia. In the early stages, Arp2/3 was concentrated in the cortex, and there was brighter staining over the short, F-actin–rich protrusions (Figure7A-B, far left). At later stages, the platelet contracts and growing filopodia stained for Arp2/3 at their tips and their bases (Figure 7A-B, second from left). As activation progressed, filopodia elongated and Arp2/3 was often found at the tip and at the base (Figure 7A-B, third and fourth from the left). In some cases, an area of Arp2/3 staining was also present on the shaft of the filopodium. Such filopodia are too small to be imaged by phase microscopy, containing as few as 3 actin filaments.1,3,9 30 Higher magnification of these filopodia demonstrated the relationship between Arp2/3 and actin filaments (Figure 7C). The small size of platelets at the filopodial stage of activation is apparent when they were compared to a fully spread platelet at the same magnification (Figure 7D).

Gallery of platelets at early stages of shape change showing localization of Arp2/3 at the cortex and at the tips and roots of filopodia.

Representative double images of platelets fixed in the presence of detergent as in Figure 6A-B. (A) Four different platelets fixed at progressively later stages of activation from left to right and imaged for both F-actin (FITC–phalloidin, green) and Arp2/3 (Cy3, red). (B) Corresponding images of the same 4 platelets showing only the actin channel. (C) Higher magnification of the 2 filopodia indicated in panel A by an asterisk. (D) Fully spread platelet at the same magnification as the other platelets in this figure for size comparison.

Gallery of platelets at early stages of shape change showing localization of Arp2/3 at the cortex and at the tips and roots of filopodia.

Representative double images of platelets fixed in the presence of detergent as in Figure 6A-B. (A) Four different platelets fixed at progressively later stages of activation from left to right and imaged for both F-actin (FITC–phalloidin, green) and Arp2/3 (Cy3, red). (B) Corresponding images of the same 4 platelets showing only the actin channel. (C) Higher magnification of the 2 filopodia indicated in panel A by an asterisk. (D) Fully spread platelet at the same magnification as the other platelets in this figure for size comparison.

Discussion

The experiments reported here provide direct functional evidence that Arp2/3 is required for both filopodial and lamellipodial formation in the platelet. Loading of platelets with αArp2 inhibits TRAP-stimulated actin polymerization and the formation of actin structures in a dose-dependent manner. This requirement for Arp2/3 suggests that actin polymerization, rather than reorganization of existing filaments, drives the first step of filopodial formation.

Arp2 and the formation of filopodia

The presence of Arp2/3 at the tips of the filopodia is surprising because Arp2/3 is reported to bind the pointed ends and the sides of actin filaments, whereas the other end, the barbed end, is at the tips of filopodia, as reported in cultured cells.34 Arp2/3 may be passively carried to the tip, along with membrane, as the filopodium grows. Arp2/3 may then nucleate new filaments for further growth of the filopodium. Alternatively, all platelet extensions that appear to be filopodia may not be identical to those produced by cells in culture. Indeed, in platelets, such extensions were originally termedpseudopodia, and some were found to contain microtubules.1 31 The actin filaments in some platelet filopodia may have reversed polarity, with the pointed end at the tip. Re-examination by electron microscopy of the actin organization and polarity in the platelet pseudopodia is needed to resolve these possibilities.

Whether Arp2/3 plays a role in filopodial formation in other cells is controversial. Evidence for Arp2/3 involvement is that cdc42, reported to activate Arp2/3,20,24 initiates filopodial formation in cultured cells.35,36 On the other hand, the Arp2/3 complex nucleates branched filament networks in vitro14,18,37 and is found at branch points by immunogold labeling in cells.19 Filopodia are composed of parallel filaments and do not have such branches, making such network formation by Arp2/3 seem unlikely. However, 2 recently published experiments show that Arp2/3 can nucleate filament formation in the absence of branching. First, anti-p34 blocks branching and slows, but does not inhibit, Arp2/3-induced actin polymerization;17 second, polymerization by Arp2/3 in the presence of tropomyosin has a similar effect37—no branching and a polymerization rate slower than fully activated Arp2/3 but faster than actin alone.

At least at the early stage of filopodial projection in platelets, Arp2/3 seems to be required, but it may not be sufficient, and other proteins such as VASP may be involved at later stages. VASP is found at the tips of filopodia in neuronal growth cones,38,39 and recruitment of VASP by the proline-rich domain of N-WASp is required in addition to Arp2/3 for efficient actin polymerization at the cell surface of a hematopoietic cell line, RBL-2H3.40 Initially described in stress fibers in platelets spread on glass,41VASP has recently been shown along the length of platelet filopodia and at the edge of the lamellipodia during spreading.6 Because VASP inhibits gelsolin severing, we have recently proposed that the release of VASP from sides of filaments could potentiate gelsolin activity.6 Many other actin-binding proteins that organize actin filament networks into three-dimensional structures are present in platelets and must act in concert on the newly formed filaments in a highly regulated choreography.

Inhibition by αArp2 is specific

Six control experiments establish that αArp2 inhibition is caused by its binding to Arp2 protein. Each of these 6 experiments was performed both in the pyrene assay and in the spreading assay. First, 3 different rabbits produced inhibitory antibodies. Second, preimmune antibodies, drawn from each rabbit before immunization, had no detectable effect. Third, αArp2 was highly specific for Arp2 by immunoprecipitation and Western blot. Anti-Arp2 did not precipitate other proteins, including actin or p34, another Arp2/3 family member. Fourth, inhibition was not detected with affinity-purified antibodies against another actin-binding protein, kaptin, or against p34, another Arp2/3 subunit. Fifth, αArp2 Fab fragments, which lack the ability to cross-link antigen, had the same inhibitory effect as intact αArp2. Sixth, pretreatment of the antibody with recombinant Arp2 protein eliminated inhibitory activity.

Activation of Arp2/3 in platelets

Another question will be how Arp2/3 is activated in platelets. Our results show that the thrombin and the glass-activated pathways converge on Arp2/3. In humans, N-WASp but not the WASp isoform activates Arp2/3.42-44 Platelets have little N-WASp and abundant WASp.45,46 Platelet extracts do not support the N-WASp–dependent actin polymerization induced by Shigellabacteria.47 Furthermore, platelets from patients with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome have no detectable defect in actin assembly on activation though they are abnormally small,48 indicating that some protein other than WASp must activate Arp2/3 in platelets. Other members of the WASp/Scar family appear to be expressed in platelets (Oda, personal communication). If the WIP isoform turns out to be present in platelets, this could be the activator of Arp2/3 for filopodial production.49 Because WASp appears to be the downstream mediator of cdc42, it will be important to determine whether cdc42 is also involved in platelet filopodial formation.

Binding to the sides of actin filaments can also activate Arp2/3.18,37,50 Actin filaments of the platelet membrane skeleton could thus serve as activation sites for Arp2/3 in platelets following agonist stimulation. The membrane skeleton of the nonstimulated platelet consists of submembranous microfilaments that line the inner surface of the platelet plasma membrane in an ordered array parallel to the membrane.51,52 In quick-freeze, deep-etch replicas of platelets captured in the early stages (1-2 seconds) after thrombin activation, this array becomes more prominent.52 Biochemical analysis of the resting platelet membrane skeleton demonstrates that actin, spectrin, myosin, and actin-binding protein are present.53-56 This membrane skeleton undergoes dramatic remodeling after agonist stimulation, including severing of the actin filaments.7,8,31,55 56 If severing is a consequence of the release of filaments by VASP, as we have proposed, then these filament sides could act as activation sites for Arp2/3.

Evidence for other nucleators of actin polymerization

Arp2/3 was not detected in all actin structures, and some actin-polymerizing activity remained in extracts treated with αArp2. Thus, other mechanisms may exist to initiate polymerization. Indeed, actin polymerization seems too important to be mediated by a single mechanism. Evidence supporting an alternative mechanism for actin polymerization includes a report that only 40% of cold-induced, barbed-end formation in platelets is inhibited by the C-terminal of N-WASp.57 Other candidates for nucleators include VASP (discussed above), gelsolin, moesin, and kaptin. Gelsolin severing of filaments is hypothesized to produce fragments that, once uncapped, act as nucleation sites for rapid elongation.8,58,59 Moesin, the only member of the ERM family found in platelets, is also present at filopodial tips and induces filopodiallike membrane protrusions when overexpressed in cultured cells.60 Kaptin, an ATP-sensitive F-actin–binding protein, is also found at sites of new filament formation in many cells and at the leading edges of the spread platelet.5

Alternatively, Arp2/3 may indeed be the only nucleator. After all, αArp2 inhibited the formation of all actin-based structures in spreading platelets at concentrations of 1 μg/mL. Absence of staining may not represent absence of the complex but rather an inability of the antibodies to detect it. The inhibition of actin polymerization suggests that a subset of the αArp2 antibodies compete with actin for the actin-binding domain of Arp2. Thus, actin-bound Arp2 may be recognized less well by the antibody.

Contextual model of Arp2/3 role in platelet actin reorganization

Based on these results, we propose the following model of Arp2-mediated platelet actin polymerization.61 A soluble pool of Arp2/3 is recruited to the membrane upon agonist stimulation in the first stage, rounding, of activation. Activation of this Arp2/3 would produce an explosive burst of polymerization of new filaments at the cortex. Polymerization is aided by an increase in actin monomers resulting from gelsolin severing and capping of existing filaments,6-8,11,58,59 possibly facilitated by cofilin-mediated depolymerization.16,19,27 Dissociation of side-binding proteins such as VASP would potentiate severing and depolymerization6 and expose filament sides to serve as activation sites for Arp2/3. Subsequent barbed-end capping by capping protein62 or 2E4/kaptin5 would limit the length and location of new filament elongation. Filopodia and lamellipodia would then form as new filaments become networked by other actin-binding proteins, such as VASP,6,41α-actinin,63 or tropomyosin.64

Conclusions

This study reports several significant advances. First, these results identify Arp2/3 as a major regulator of platelet actin dynamics, responsible for the formation of filopodia and lamellipodia. This represents a significant advance in our understanding of the molecular events leading to platelet shape change. Second, our new permeabilization method, which preserves the platelet's ability to respond to agonists after loading with molecules as large as immunoglobulins, at last makes it possible to manipulate the molecular composition of the platelet cytoplasm. This powerful new technology will allow us to investigate biochemical relationships between signaling pathways and morphologic changes occurring in platelets but common to all cells. Results from platelets are therefore likely to provide fundamental information about the principles and paradigms governing actin dynamics inside all cells since membrane-associated actin polymerization is also required for the formation of a wide number of physiologically significant structures in virtually all eukaryotic cells.

We thank Jem Prakash for technical assistance and Leslie Hunter for advice on bioengineering. We are grateful to Eric Fyrberg for the single-stranded cDNA of Arp2 and to John Condeelis for the anti-p34 antibody and helpful discussions. We thank Dee Bainton for her interest in our work and useful discussions.

Supported by Public Health Service award NIGMS RO1 47368 from the National Institutes of Health (E.L.B.), the Salomon Research Award (E.L.B.), and the Brown University UTRA program (E.S.K.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Elaine L. Bearer, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Brown University, Providence, RI 02912; e-mail:elaine_bearer@brown.edu.

![Fig. 2. αArp2 inhibits TRAP-stimulated actin-polymerizing activity. / Platelets were stimulated with TRAP and were permeabilized with and without antibody as indicated. Actin-polymerizing activity was measured immediately after antibody addition. For each graph, all tracings are from the same preparations of platelets and actin preparation obtained on the same day. Results are presented in arbitrary units (au), as is standard in the field. Final fluorescence intensity with nonstimulated platelets (no TRAP) was defined as 10 au. Platelet extracts always produced at least a 20% increase over actin alone (not shown). (A) Effect of αArp2 on actin-polymerizing activity of TRAP-stimulated sonicated platelets. TRAP (top tracing) increased actin-polymerizing activity 5-fold over nonstimulated platelets (lowest tracing) in samples permeabilized by sonication. Affinity-purified αArp2 added to the TRAP-stimulated platelets decreased the initial rate and the extent of polymerization, whereas anti-kaptin had little to no effect at the same concentration (0.01 mg/mL, 0.7 μM) used for αArp2. (B) Effect of αArp2 and αp34 on actin-polymerizing activity of TRAP-stimulated Triton-permeabilized platelets. Platelets were permeabilized by either sonication, as in Figure 1A, or with Triton and antibody added as indicated (αArp2 and αp34 were at 15 μg/mL [0.1 μM]). A similar increase in fluorescence was obtained with TRAP stimulation, whether platelets were permeabilized by sonication (sonic) or Triton (Tx). The increase in the initial rate of polymerization after TRAP stimulation was blocked by αArp2 regardless of whether permeabilization was with sonication or Triton. Less of an effect on TRAP-stimulated activity was detected with αp34. (C) Effect of Fab fragments of αArp2 on actin-polymerizing activity of TRAP-stimulated platelets. Platelets stimulated with TRAP and permeabilized as in Figure 1A were treated with antibodies as indicated at the following concentrations: anti-kaptin (0.1 μM), αArp2 + rArp2 (0.1 and 0.5 μM, respectively), Fab fragments of αArp2 (0.12 and 0.44 μM), and intact αArp2 from a different rabbit (0.1 μM). (D) Effect of αArp2 on actin-polymerizing activity of nonstimulated platelets. αArp2 was added (as indicated) to nonstimulated platelets immediately after sonication. Note that the arbitrary units (au) on the y-axis of the graph was expanded to increase the sensitivity to demonstrate the effect of the antibody on the lower level of activity present in nonstimulated platelets. (E) Dose dependence of αArp2 inhibition. The final fluorescence of representative experiments treated with increasing amounts of αArp2 or preimmune IgG (pre-IgG) is compared. A similar graph could be drawn for either anti-p34 or anti-kaptin as control antibody (Table 1). Experiments were normalized by setting the final fluorescence of parallel preparations, measured in the absence of antibody, at 100%, which allowed comparison of the low level of activity in nonstimulated platelets with the much higher activity after TRAP. Thus, results from TRAP-stimulated and nonstimulated experiments could be superimposed on the same graph.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/99/12/10.1182_blood.v99.12.4466/4/m_h81222703002.jpeg?Expires=1763627688&Signature=Z0gQ3wzaoR05muU703kV2sBqyiJ8Uc04BLTz253oOCe1Pz~6No5QLMBYdhIVaAdYzx-lYufvKsMzfG0enFcqFblht8QrBCzCv741ge7Ux~P~eXoWdsJMdILe4Wn9iZgRKkvFGf0Ahpf7dHpOqOUODvUgIUm8QTPFvpwH5SLPrxgCKldxwgNWlPyyFEFiBf~6OuqzZjYpf4NzKefuiGqgtdW5PyhE1JVBEdHga6DqVXhifi4ytrH8S-3yFDLMSVEKE2pmnehn-lJJQV33vGyTTmjH2QYBspO3AkYck~rH5VDyi~nauTCxyDlc~bzkuf2EgVmgjMsXmGX3knvHKGtMiA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal