Stem cell–dose escalation is one way to overcome immune rejection of incompatible stem cells. However, the number of hematopoietic precursors required for overcoming the immune barrier in recipients pretreated with sublethal regimens cannot be attained with the state-of-the-art technology for stem cell mobilization. This issue was addressed by the observation that cells within the human CD34+ population are endowed with veto activity. In the current study, we demonstrated that it is possible to harvest about 28- to 80-fold more veto cells on culturing of purified CD34+cells for 7 to 12 days with an early-acting cytokine mixture including Flt3-ligand, stem cell factor, and thrombopoietin. Analysis of the expanded cells with fluorescence-activated cell-sorter scanning revealed that the predominant phenotype of CD34+CD33− cells used at the initiation of the culture was replaced at the end of the culture by cells expressing early myeloid phenotypes such as CD34+CD33+ and CD34−CD33+. These maturation events were associated with a significant gain in veto activity as exemplified by the minimal ratio of veto to effector cells at which significant veto activity was detected. Thus, whereas purified unexpanded CD34+ cells exhibited veto activity at a veto-to-effector cell ratio of 0.5, the expanded cells attained an equivalent activity at a ratio of 0.125. The availability of novel sources of veto cells such as those in this study might contribute to the realization of immunologic tolerance in “minitransplants,” without any risk of graft-versus-host disease.

Introduction

The use of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cells for the induction of transplantation tolerance as a prelude for subsequent organ transplantation or for adoptive cell therapy in cancer represents a difficult challenge. A major obstacle to achieving this desirable goal is associated with the elusive role of donor T cells. Although numerous studies demonstrated the valuable facilitating effect of T cells on bone marrow engraftment,1-8 the risk of lethal graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) associated with alloreactive T cells is unacceptable for organ transplantation or in the treatment of nonmalignant diseases such as sickle cell anemia or autoimmunity.

Therefore, the development of new strategies for attaining durable engraftment of allogeneic stem cells with minimal risk of GVHD in patients pretreated with mild bone marrow ablative therapy is desirable. One approach to overcoming immune rejection of incompatible stem cells rigorously depleted of T cells has made use of stem cell–dose escalation.9 However, although this modality has become a clinical reality in the treatment of patients with leukemia who have previously received intensive chemotherapy, it has been suggested in studies in mice7 and nonhuman primates (X. Yao, unpublished data, July 2001) that the number of hematopoietic precursors required to overcome the immune barrier in recipients pretreated with sublethal regimens cannot be attained with the state-of-the-art technology for stem cell mobilization.

Rachamim et al10 demonstrated that cells within the human CD34+ population are endowed with potent veto activity. The term “veto” relates to the ability of cells to neutralize cytotoxic T-lymphocyte precursors (CTL-p) directed against their antigens.11-17 Thus, when purified CD34+ cells were added to bulk mixed lymphocyte reactions (MLRs), they suppressed CTLs against matched stimulators but not against stimulators from a third party.10

Clearly, the limitations of CD34+ collection in humans might be overcome if it was possible to expand ex vivo the cells within the early progenitor population that are responsible for the veto effect. Our results in this study suggest that veto activity, unlike the self-renewal potential associated with pluripotential stem cells, can indeed be expanded in short-term culture of CD34+cells. Thus, it was possible to harvest about 80-fold more veto cells on culturing of CD34+ cells for 7 to 12 days under conditions that induce predominantly myeloid differentiation. The availability of such enriched veto cell preparations should provide a new option for boosting engraftment of megadose CD34+transplants in patients who have undergone mild conditioning treatment and thereby induce durable immune tolerance without any risk of GVHD.

Methods

Collection of peripheral blood progenitor cells, processing, and CD34+ cell purification

Peripheral blood progenitor cells (PBPCs) were collected from healthy related allogeneic donors enrolled in our ongoing transplant programs, after mobilization of cells with standard doses of recombinant granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. To prepare mononuclear cells from PBPCs, cells were placed on a Ficoll-Paque Plus gradient (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) and centrifuged. CD34+ cells were purified by magnetic cell sorting using magnetic beads linked to anti-CD34 mAb (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). The purity of CD34+ cells was analyzed by flow cytometry.

CTL reactivity

To measure CTL reactivity, we used the method described by Rachamim et al10 and established in mouse studies by Leshem et al.18 Briefly, this method makes use of secondary MLRs to amplify the initial signal. We found this to be important because of the low signal observed in a marked proportion of our studies in which CTL reactivity was measured at the end of primary MLRs. Such low responses might be associated with the delay in obtaining blood samples caused by the requirement to test for possible viral contamination, as well as by HLA typing.

The primary MLR was prepared as follows. Responder lymphocytes from donor C were allowed to react with stimulator cells from 2 donors (A and B). Responder and stimulator donors were selected according to their class I HLA typing to be non–cross-reactive with each other. The cells from donor C (1 × 106/mL) were cultured with 1 × 106/mL irradiated (30 Gy) stimulator cells, with or without addition of 0.5 × 106/mL CD34+ cells (obtained from donor A). The cells were cultured in 6 mL complete tissue culture medium (CTCM) and 10% fetal-calf serum (FCS; Biological Industries, Kibbutz Beit Haemek, Israel) for 5 days. CTCM is RPMI 1640 containing 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM HEPES, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, and 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol (Biological Industries).

At the end of the primary MLR, cells were harvested from the MLR culture and separated by using the Ficoll method. Serial 4-fold dilutions of responder cells (from 4 × 104 to 0.156 × 103/well) were then prepared and seeded in round-bottomed, 96-well plates in 16 replicate samples for each dilution. Each well contained 105 irradiated stimulator cells from the donor who provided the original cells in the bulk MLR. The cultures were incubated for 7 days in CTCM, 10% FCS, and 10 U/mL recombinant interleukin 2 (IL-2; EuroCetus, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) in a final volume of 0.2 mL.

Estimate of CTL activity

Cytotoxic activity was assayed by transferring a fixed volume (100 μL) of limiting-dilution analysis cultures to conical-bottomed, 96-well plates (Greiner, Frickenhausen, Germany) and incubating the effector cells for 4 hours with 5 × 103 blasts (target cells) from the donor or a third party that had been stimulated with concanavalin A (Sigma, St Louis, MO) and labeled with chromium 51 (51Cr). The mean radioactivity from 16 replicate samples was calculated, and the percentage of specific lysis was determined by using the following equation: 100 × (experimental release − spontaneous release)/(total release − spontaneous release). The release of 51Cr by target cells cultured in medium alone was defined as spontaneous release; that by cells lysed with 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate was defined as total release.

Frequency calculation of CTL-p

To calculate the frequency from the limiting-dilution culture readout, we used the following equation: ln y = −fx + ln a (which represents the zero-order term of the Poisson distribution19), in which y is the percentage of nonresponding cultures, x is the number of responding cells per culture, f is the frequency of responding precursors, and a is the y-intercept theoretically equal to 100%. Microwell cultures were considered positive for a cytolytic response when values exceeded the mean spontaneous release value by at least 3 SDs of the mean. The percentage of responding cultures was defined by calculating the percentage of positive cultures. The CTL-p frequency (f) and SE were determined from the slope of the line drawn by using linear regression analysis of the data. To evaluate the significance of the difference between the slopes of 2 regression lines, t was calculated as follows: t = f1−f2/√[SE2(f1) + SE2(f2)].20

The role of cell contact (transwell assay)

Responder cells (1 × 106/mL) and irradiated stimulator cells (1 × 106/mL) were placed in the lower chamber of a transwell culture system (Transwell-col; Costar, Cambridge, MA). Purified donor CD34+ cells (0.5 × 106/mL) were placed together with the responder cells (1 × 106/mL) in the upper chamber. After 5 days of incubation, the cells were harvested and again cultured in limiting-dilution cultures.

Flow cytometry analysis of intracellular interferon γ

Cells from 5-day MLRs and additional 7-day limiting-dilution cultures were harvested and activated (106/mL) with 8 ng/mL phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (Sigma), 1 μM ionomycin (Sigma), and 2 μM monensin (Sigma). Monensin was added to the cultures to cause intracellular accumulation of newly synthesized proteins by arresting their transport in the Golgi complex. After 2 hours of incubation at 37°C, cells were collected, washed in phosphate-buffered saline, and distributed into plastic tubes (∼ 0.2 × 106cells/tube) for immunofluorescent staining. A supplement of ChromPure human IgG (50 μg/tube; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) was added to reduce nonspecific staining, and the cells were then stained with anti-CD3 Cy-Chrom (PharMingen, San Diego, CA), washed, fixed, and permeabilized with fixation and permeabilization reagents (Leucoperm kit; Serotec, Oxford, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For intracellular staining, cells were incubated with anti–interferon γ (anti–IFN-γ) and fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugated (PharMingen), or its appropriate isotype control. Samples were analyzed by using a FACScan flow cytometer, and data were analyzed with LYSIS II software (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

Expansion culture

Purified CD34+ cells (1 × 105/mL in a total volume of 1 mL) were cultured in 24-well plates in Iscoves modified Dulbecco medium containing 10% FCS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin, 50 ng/mL recombinant human Flt3-ligand (FL), 50 ng/mL recombinant human stem cell factor (SCF), and 1 ng/mL recombinant human thrombopoietin (TPO; R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN). On day 5, the same doses of FL, SCF, and TPO were added; and on days 7 to 12, cells were harvested and tested for their veto activity.

Results

The veto activity of noncultured CD34+cells

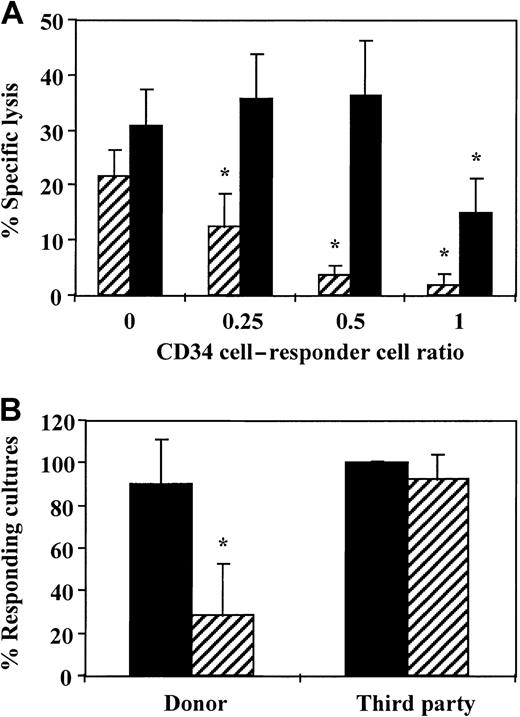

To evaluate whether veto cells can be expanded in a short-term culture of CD34+ cells, we first characterized the veto effect of noncultured CD34+ cells at different ratios of CD34+ to responder cells to define the lowest ratio at which veto activity was exhibited. As shown in Figure1A, marked inhibition was detected at a CD34+-to-responder cell ratio of 0.5 or higher. At this ratio, 80% inhibition of the CTL activity was recorded when the culture contained stimulator cells from the CD34+ donor, whereas no significant inhibition was detected when the culture contained stimulators with a third-party origin. On the basis of this dose-response curve, all subsequent experiments were carried out at a CD34+-to-responder cell ratio of 0.5.

Veto activity of CD34+ cells.

(A) A dose-response curve testing the veto activity of CD34+ cells at different ratios of veto to responder cells. Equal numbers (1 × 106/mL) of responder cells and irradiated allogeneic stimulator cells from the donor of the CD34+ cells (▨) and a third-party donor (▪) were cocultured for 5 days. Different numbers of purified CD34+cells were added to obtain the indicated ratios of CD34+ to responder cells. The responder cells were then cultured again for 7 days under limiting dilution, and the CTL activity was determined by51Cr-release assay. Two experiments were carried out. Data are from 1 representative experiment and represent the percentage of specific lysis at a cell concentration of 4 × 104effector cells/well. The asterisk indicates a significant difference (P < .001 on t test compared with control cultures without CD34+ cells). (B) The average CTL response (±SD) in the presence (▨) and absence of CD34+ cells (▪) at a veto-to-responder cell ratio of 0.5. The veto effect was tested as described above, and data from 11 independent experiments using different donors were pooled. Data represent the percentage of responding cultures at a cell concentration of 1 × 104cells/well. The asterisk indicates a significant difference (P < .001 on t test compared with control cultures without CD34+ cells).

Veto activity of CD34+ cells.

(A) A dose-response curve testing the veto activity of CD34+ cells at different ratios of veto to responder cells. Equal numbers (1 × 106/mL) of responder cells and irradiated allogeneic stimulator cells from the donor of the CD34+ cells (▨) and a third-party donor (▪) were cocultured for 5 days. Different numbers of purified CD34+cells were added to obtain the indicated ratios of CD34+ to responder cells. The responder cells were then cultured again for 7 days under limiting dilution, and the CTL activity was determined by51Cr-release assay. Two experiments were carried out. Data are from 1 representative experiment and represent the percentage of specific lysis at a cell concentration of 4 × 104effector cells/well. The asterisk indicates a significant difference (P < .001 on t test compared with control cultures without CD34+ cells). (B) The average CTL response (±SD) in the presence (▨) and absence of CD34+ cells (▪) at a veto-to-responder cell ratio of 0.5. The veto effect was tested as described above, and data from 11 independent experiments using different donors were pooled. Data represent the percentage of responding cultures at a cell concentration of 1 × 104cells/well. The asterisk indicates a significant difference (P < .001 on t test compared with control cultures without CD34+ cells).

Figure 1B shows a summary of the results of 11 independent experiments conducted with cells from different donors. HLA class I disparities for the responder and stimulator cells used in each experiment are summarized in Table 1. The average CTL activity against target cells from the donor of the CD34+ cells was 90.3% ± 20.8%, and it was markedly inhibited by the addition of the CD34+ cells (28.1% ± 24.7%). In contrast, the CTL activity against third-party cells (100% ± 1%) was not affected significantly by the presence of CD34+ cells (92% ± 12.5%). It could be argued that if the addition of CD34+ cells to an anti–third-party MLR led to a less extensive expansion of the CD34+ cells compared with their expansion when added to an anti–CD34+-donor MLR, the apparent reduction in CTL activity might have resulted from a different dilution factor of the CTL-p frequency by the CD34+ cells. However, in 11 experiments, the average cell recovery at the end of the 5-day culture when comparing antidonor MLRs in the presence and absence of CD34+ cells was increased by a factor of 1.35 ± 0.58, whereas the increase in cell recovery in anti–third-party MLRs was 1.61 ± 0.65 (P ≥ .13).

HLA class I determinants of effector and stimulator cells

| Experiment . | Responder cells . | Stimulator cells . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Donor CD34+cells . | Third-party cells . | ||

| 1 | A3/68(28), B7/14 | A1/30(19), B8/13 | A24(9)/33(19), B35/52(5) |

| 2 | A3/24(9), B13/63(15) | A1/68(28), B37/35 | A24(9)/26(10), B38(16) |

| 3 | A2/24(9), B14/40 | A1/68(28), B37/35 | A3/24(9), B13/63(15) |

| 4 | A3/32(19), B8/44(12) | A1/2, B44(12)/63(15) | A30(19), B35/53 |

| 5 | — | A1/24, B35/51 | A3/23, B41 |

| 6 | — | A1/26, B35 | A2/3, B41/61 |

| 7 | A2, B18/41 | A26(10)/68(28), B38(16)/56(22) | A1/23(9), B35/49(21) |

| 8 | A29(19)/30(19), B13/7 | A1/24(9), B8/38(16) | A68(28), B14/44(12) |

| 9 | A11/24(9), B41/51(5) | A1/24(9), B8/38(16) | A2/30(19), B18/44(12) |

| 10 | A2/26(10), B38(16)/47 | A2/30, B13/18 | A1/3, B52(5)/38(16) |

| 11 | — | A1/11, B35/52(5) | A2/28, B38(16), 55(22) |

| Experiment . | Responder cells . | Stimulator cells . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Donor CD34+cells . | Third-party cells . | ||

| 1 | A3/68(28), B7/14 | A1/30(19), B8/13 | A24(9)/33(19), B35/52(5) |

| 2 | A3/24(9), B13/63(15) | A1/68(28), B37/35 | A24(9)/26(10), B38(16) |

| 3 | A2/24(9), B14/40 | A1/68(28), B37/35 | A3/24(9), B13/63(15) |

| 4 | A3/32(19), B8/44(12) | A1/2, B44(12)/63(15) | A30(19), B35/53 |

| 5 | — | A1/24, B35/51 | A3/23, B41 |

| 6 | — | A1/26, B35 | A2/3, B41/61 |

| 7 | A2, B18/41 | A26(10)/68(28), B38(16)/56(22) | A1/23(9), B35/49(21) |

| 8 | A29(19)/30(19), B13/7 | A1/24(9), B8/38(16) | A68(28), B14/44(12) |

| 9 | A11/24(9), B41/51(5) | A1/24(9), B8/38(16) | A2/30(19), B18/44(12) |

| 10 | A2/26(10), B38(16)/47 | A2/30, B13/18 | A1/3, B52(5)/38(16) |

| 11 | — | A1/11, B35/52(5) | A2/28, B38(16), 55(22) |

Measurements were made by using serologic analysis. Values in parentheses denote parent antigens from which the new specifications have split.

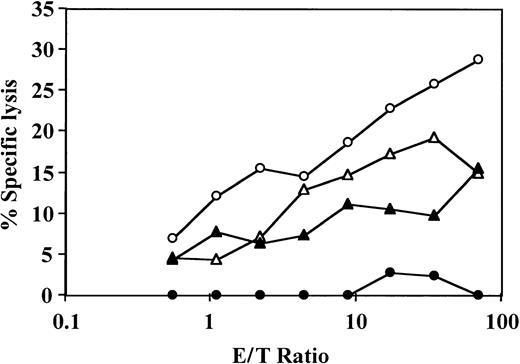

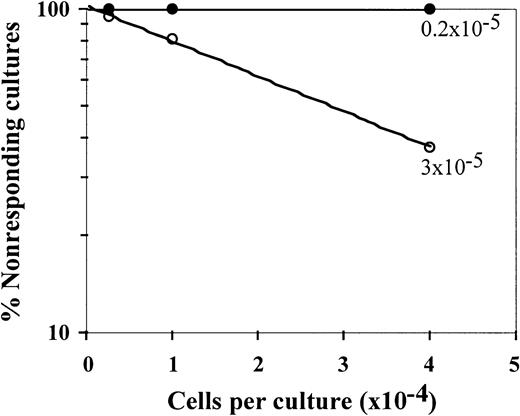

The veto specificity of the CD34+ cells was also exhibited when the stimulators from the third party were added to the initial bulk MLR together with the stimulators from the CD34+ donor (Figure 2). Thus, on addition of CD34+ cells, the CTL-p frequency against the target cells from the CD34+ donor was reduced by 1 log, from 10 × 10−5 to 0.8 × 10−5(P < .005), whereas the CTL-p frequency against the third-party target cells was reduced from 3 × 10−5 to 2 × 10−5 (P > .1).

Veto activity of CD34+ cells: the veto activity is specific for CTL-p against CD34+ donor cells.

Responder cells (1 × 106/mL) were simultaneously cultured with irradiated stimulators (0.7 × 106/mL) from the donor of the CD34+ cells (○) and a third party (▵) for 5 days in the absence (○,▵) or presence (●,▴) of CD34+ cells added at a veto-to-responder ratio of 0.4:1. The responder cells were then divided equally, and each fraction was cultured again for 7 days under limiting dilution with stimulators from the donor of the CD34+ cells (A) or stimulators from the third-party donor (B). The CTL activity was determined by51Cr-release assay with the relevant target cells. The CTL-p frequency was calculated. The parameters for the different regression lines were as follows. (A) CTL-p frequency against stimulators from the CD34+ donor in the absence of CD34+ cells (○) was ln y = − 13.8 × 10−5x + ln 118.6 (R2 = 0.955, SE(f) = 2.1 × 10−5,P = .022, f with 95% confidence interval [CI] = 4.7 × 10−5 to 2.3 × 10−4). In the presence of CD34+ cells (●), ln y = −0.84 × 10−5x + ln 102.9 (R2 = 0.873, SE(f) = 2.2 × 10-6,P = .065, f with 95% CI = − 1.3 × 10−6 to 1.8 × 10−5). In the presence of CD34+ cells (●), f was significantly lower (P < .005) than in the absence of these cells (○). (B) Anti–third-party CTL-p frequency in the absence of CD34+ cells (▵) was ln y = − 2.6 × 10−5 x + ln 103.6 (R2 = 0.982, SE(f) = 2.4 × 10−6,P = .008, f with 95% CI = 1.5 × 10−5 to 3.7 × 10−5). In the presence of CD34+ cells (▴): ln y = − 2 × 10−5 x + ln 97.8 (R2 = 0.898, SE(f) = 3.8 × 10−6,P = .014, f with 95% CI = 7.6 × 10−6 to 3.2 × 10−5). There was no significant difference between f in the presence (▴) and absence (▵) of CD34+cells (P > .1).

Veto activity of CD34+ cells: the veto activity is specific for CTL-p against CD34+ donor cells.

Responder cells (1 × 106/mL) were simultaneously cultured with irradiated stimulators (0.7 × 106/mL) from the donor of the CD34+ cells (○) and a third party (▵) for 5 days in the absence (○,▵) or presence (●,▴) of CD34+ cells added at a veto-to-responder ratio of 0.4:1. The responder cells were then divided equally, and each fraction was cultured again for 7 days under limiting dilution with stimulators from the donor of the CD34+ cells (A) or stimulators from the third-party donor (B). The CTL activity was determined by51Cr-release assay with the relevant target cells. The CTL-p frequency was calculated. The parameters for the different regression lines were as follows. (A) CTL-p frequency against stimulators from the CD34+ donor in the absence of CD34+ cells (○) was ln y = − 13.8 × 10−5x + ln 118.6 (R2 = 0.955, SE(f) = 2.1 × 10−5,P = .022, f with 95% confidence interval [CI] = 4.7 × 10−5 to 2.3 × 10−4). In the presence of CD34+ cells (●), ln y = −0.84 × 10−5x + ln 102.9 (R2 = 0.873, SE(f) = 2.2 × 10-6,P = .065, f with 95% CI = − 1.3 × 10−6 to 1.8 × 10−5). In the presence of CD34+ cells (●), f was significantly lower (P < .005) than in the absence of these cells (○). (B) Anti–third-party CTL-p frequency in the absence of CD34+ cells (▵) was ln y = − 2.6 × 10−5 x + ln 103.6 (R2 = 0.982, SE(f) = 2.4 × 10−6,P = .008, f with 95% CI = 1.5 × 10−5 to 3.7 × 10−5). In the presence of CD34+ cells (▴): ln y = − 2 × 10−5 x + ln 97.8 (R2 = 0.898, SE(f) = 3.8 × 10−6,P = .014, f with 95% CI = 7.6 × 10−6 to 3.2 × 10−5). There was no significant difference between f in the presence (▴) and absence (▵) of CD34+cells (P > .1).

The veto activity of CD34+ cells is not due to cold target inhibition

It could be argued that the suppression observed on addition of CD34+ cells was due to cold target inhibition, that is, that the CD34+ cells added to the effector population could have competed with the 51Cr-labeled target cells for CTL-mediated lysis at the end of the culture period. Such competition will take place only when the CD34+ and target cells bear the same HLA class I antigens and therefore the observed chromium release will be reduced in antidonor cultures but not in anti–third-party cultures. To address this possibility, we isolated the effector T cells at the end of the bulk culture period by E-rosetting with sheep red blood cells (analysis of this fraction by flow cytometry showed more than 90% T cells and no detectable CD34+ cells) and tested the CTL activity of the purified T cells. As shown in Figure 3, the veto effect was retained after removal of the CD34+cells.

The veto effect on the effector T cells is not affected by removal of CD34+ cells at the end of the cell culture.

Responder cells and irradiated allogeneic stimulator cells were cocultured for 5 days with (●) or without (○) addition of CD34+ cells. The responder cells were then cultured again with the original stimulators and IL-2 (10 U/mL) for 7 days. At the end of the second culture period, the responders were isolated by E-rosetting with sheep red blood cells and tested for CTL activity by analysis of 51Cr-release. A control experiment with (▴) and without (▵) addition of the same CD34 cells to an MLR of the same responder cells against a third party was carried out in parallel. Shown are the results of 1 experiment. The SD of 6 values was consistently less than 10% of the mean.

The veto effect on the effector T cells is not affected by removal of CD34+ cells at the end of the cell culture.

Responder cells and irradiated allogeneic stimulator cells were cocultured for 5 days with (●) or without (○) addition of CD34+ cells. The responder cells were then cultured again with the original stimulators and IL-2 (10 U/mL) for 7 days. At the end of the second culture period, the responders were isolated by E-rosetting with sheep red blood cells and tested for CTL activity by analysis of 51Cr-release. A control experiment with (▴) and without (▵) addition of the same CD34 cells to an MLR of the same responder cells against a third party was carried out in parallel. Shown are the results of 1 experiment. The SD of 6 values was consistently less than 10% of the mean.

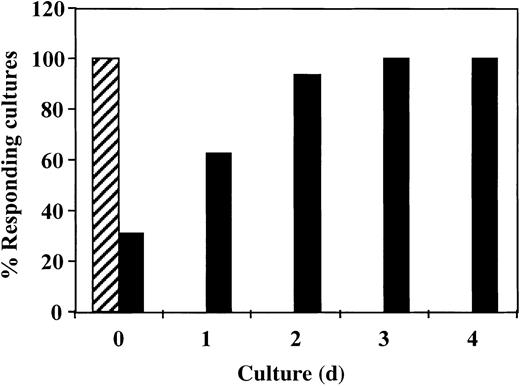

Inhibition of antidonor response requires the addition of CD34+ cells in the first 24 hours of culture

To study the critical period for the induction of the veto activity by CD34+ cells, we added the CD34+cells at different times after initiation of the culture. As shown in Figure 4, inhibition of the response took place only when the CD34+ cells were added at initiation of the culture or 1 day afterward. No inhibition was detected when CD34+ cells were added on day 2 or later. Thus, the veto effect of CD34+ cells, similar to that of other veto cells,21-24 acts in the early induction phase of allogeneic CTLs.

The veto activity of CD34+ cells: inhibition of antidonor response requires addition of CD34+ cells in the initial 24 hours of culture.

Responder cells and irradiated allogeneic stimulator cells were cocultured for 5 days with (▪) or without (▨) addition of CD34+ cells. CD34+ cells were added at different time intervals. At the end of the culture period, the responders were cultured again in limiting-dilution cultures for 7 days and the CTL activity was determined.

The veto activity of CD34+ cells: inhibition of antidonor response requires addition of CD34+ cells in the initial 24 hours of culture.

Responder cells and irradiated allogeneic stimulator cells were cocultured for 5 days with (▪) or without (▨) addition of CD34+ cells. CD34+ cells were added at different time intervals. At the end of the culture period, the responders were cultured again in limiting-dilution cultures for 7 days and the CTL activity was determined.

The veto effect is not mediated by contaminating CD34− cells and requires cell contact

It could be argued that the reduction in antidonor reactivity by CD34+ cells is mediated by contaminating cells capable of alloreactivity against the effector cells. Therefore, we compared the veto effect of CD34+ cells with that exhibited by the CD34− cell fraction, which contains a significant number of T cells. As shown in Table2, although a marked reduction in CTL-p frequency was found in MLRs to which purified CD34+ cells were added, no inhibition was detected when cells of the CD34− fraction were added. Thus, the veto activity of cells within the CD34+ cell fraction cannot be attributed to residual CD34− cells. To investigate whether the CD34+ veto activity could be delivered through the liquid medium without cell contact, MLRs were prepared in transwell plates, with 2 chambers separated by a membrane. The responder cells and the irradiated donor stimulator cells were placed in the lower chamber and the purified CD34+ cells were placed together with the responder cells in the upper chamber. As shown in Table 2, CTL activity was not reduced when the CD34+ cells were separated from the stimulated responder cells by a membrane that may allow passage of soluble factors but not cells.

Results indicating that the veto effect is not mediated by contaminating CD34− cells and requires cell contact

| Cells* . | MLR against donor A . | MLR against donor B . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTL activity (% responding cultures)† . | Veto activity (% inhibition)‡ . | CTL activity (% responding cultures)† . | Veto activity (% inhibition)‡ . | |

| None | 87.5 | — | 93.75 | — |

| CD34+ | 18.75 | 79 | 62.5 | 33 |

| CD34− | 100 | 0 | Not done | — |

| CD34+ in transwell | 87.5 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| Cells* . | MLR against donor A . | MLR against donor B . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTL activity (% responding cultures)† . | Veto activity (% inhibition)‡ . | CTL activity (% responding cultures)† . | Veto activity (% inhibition)‡ . | |

| None | 87.5 | — | 93.75 | — |

| CD34+ | 18.75 | 79 | 62.5 | 33 |

| CD34− | 100 | 0 | Not done | — |

| CD34+ in transwell | 87.5 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

The role of alloreactivity was evaluated by testing the veto effect of the CD34+ cells in comparison to the CD34− cells, which included a significant number of alloreactive T cells compared with the CD34+cells. The role of cell contact was evaluated by using the transwell assay. Briefly, the responder cells to be tested for their cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) response were cultured with irradiated stimulator cells in the lower chamber of the transwell plate. The CD34+ cells were cultured with responder cells in the upper chamber.

Cells from donor A were added to a 5-day mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) against stimulator cells from donor A or B.

The CTL activity was tested at the end of a 7-day limiting-dilution culture in microtiter plates. Wells were scored positive for CTL activity when chromium release exceeded the mean spontaneous release value by at least 3 SDs from the mean. Data are the percentages of responding cultures at a cell concentration of 1 × 104 responder cells/well.

Veto activity of tested cells was evaluated by assessment of their capacity to inhibit alloreactive CTL precursors in the MLR to which they were added at a 0.5 ratio of veto to responder cells.

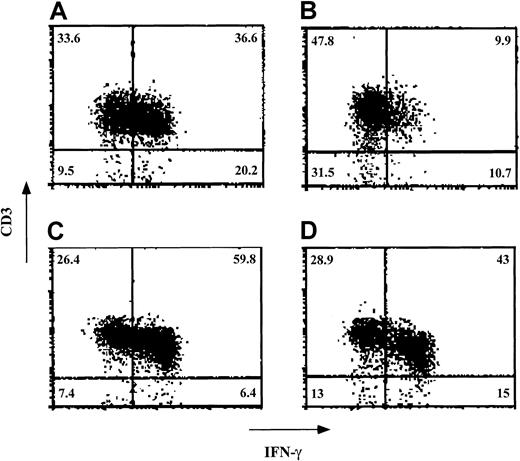

Specific reduction by CD34+ cells of effector cells positive for intracellular IFN-γ

The specificity exhibited when the veto activity of CD34+ cells was tested in MLRs was also reflected by the levels of effector T cells positive for intracellular IFN-γ. Thus, in 7 experiments, the percentage of CD3+ cells expressing IFN-γ on stimulation against cells obtained from the donor of the CD34+ cells was reduced by 47.5% ± 15.3% when CD34+ cells were added at a veto-to-responder cell ratio of 0.5. In contrast, when stimulated against third-party cells, CD3+ cells positive for IFN-γ had a significantly lower average inhibition level on addition of CD34+ cells (18.7% ± 19.7%; P < .001).

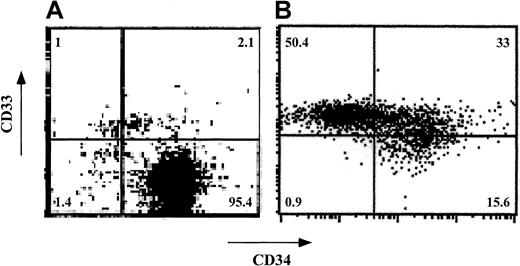

Expansion of veto cells after short-term culture of CD34+ cells

Expansion of human CD34+ cells in short-term cultures is usually associated with a significant loss of self-renewal capacity and with differentiation into myeloid phenotypes.25-29 To test whether CD34+ cells can be expanded ex vivo without loss of veto activity, CD34+ cells were cultured for a short period (7-12 days) in the presence of an early-acting cytokine mixture including FL, SCF, and TPO30 (concentrations of 50, 50, and 1 ng/mL, respectively). Phenotyping using fluorescence-activated cell-sorter scanning (FACS) revealed that although about 97% of the cells were CD34+CD33− before culture, the expanded cells had 3 major subpopulations: CD34+CD33−(15.6%), CD34+CD33+ (33.0%), and CD34−CD33+ (50.5%; Figure5). Furthermore, most of the cells displayed CD13 (79%) and low CD4 levels (80%) and did not express CD8, CD20, or CD56 (data not shown). Thus, as expected, the cells had differentiated predominantly along the myeloid lineage.

Phenotypic characterization of ex vivo–expanded purified CD34+ cells.

CD34+ cells were cultured for 7 days in Iscoves modified Dulbecco medium containing FL, SCF, and TPO. CD34 and CD33 cell-surface expression was analyzed by cytofluorometry before (A) and after (B) ex vivo expansion. The percentage of each cell subpopulation is shown in the relevant area of each dot plot.

Phenotypic characterization of ex vivo–expanded purified CD34+ cells.

CD34+ cells were cultured for 7 days in Iscoves modified Dulbecco medium containing FL, SCF, and TPO. CD34 and CD33 cell-surface expression was analyzed by cytofluorometry before (A) and after (B) ex vivo expansion. The percentage of each cell subpopulation is shown in the relevant area of each dot plot.

The ex vivo–generated cells were tested for their effect on CTL-p frequency (Figure 6) and activity (Table3) and their effect on the levels of effector T cells positive for intracellular IFN-γ (Figure7). As shown in Table 3, significant veto activity (> 70% inhibition) was exhibited by the expanded cells at veto-to-responder cell ratios of 0.5, 0.25, and 0.125. When tested at a veto-to-effector cell ratio of 0.125, the expanded cells markedly inhibited the antidonor CTL response, whereas the anti–third-party CTL response was not inhibited. Also at this ratio, the addition of expanded cells led to a reduction in CTL-p frequency, from 3 × 10−5 to 0.2 × 10−5 cells (P < .001; Figure 6). Thus, compared with the results in the initial CD34+CD33− cell fraction, in which the veto activity was detected only at a veto-to-responder cell ratio of 0.5 (Figure 1A), the veto activity of the expanded cells was enriched 4 fold. Considering the 7- to 20-fold expansion of the cells at the end of the culture, the total number of veto cells was increased by 28 to 80 fold.

Veto activity of ex vivo–expanded CD34+cells: detection of veto effect at a veto-to-responder cell ratio of 0.125.

Limiting dilution of CTL-p in cultures of responder cells stimulated against cells from the donor of the CD34+ cells in the presence (●) or absence (○) of ex vivo–expanded cells was carried out, and the CTL-p frequency was calculated. The parameters for the different regression lines were as follows. In the absence of CD34+-expanded cells (○), ln y = − 2.6 × 10−5 x + ln 106.1 (R2 = 0.999, SE = 3.1 × 10−7,P = .007, f with 95% CI = 2.2 × 10−5 to 3 × 10−5). In the presence of CD34+-expanded cells (●), ln y = − 0.18 × 10−5 x + ln 101.1 (R2 = 0.964, SE = 3.5 × 10−7,P = .121, f with 95% CI = −2.6 × 10−6to 6.3 × 10−6). In the presence of ex vivo–expanded cells (●), f was significantly lower (P < .001) than in the absence of these cells (○).

Veto activity of ex vivo–expanded CD34+cells: detection of veto effect at a veto-to-responder cell ratio of 0.125.

Limiting dilution of CTL-p in cultures of responder cells stimulated against cells from the donor of the CD34+ cells in the presence (●) or absence (○) of ex vivo–expanded cells was carried out, and the CTL-p frequency was calculated. The parameters for the different regression lines were as follows. In the absence of CD34+-expanded cells (○), ln y = − 2.6 × 10−5 x + ln 106.1 (R2 = 0.999, SE = 3.1 × 10−7,P = .007, f with 95% CI = 2.2 × 10−5 to 3 × 10−5). In the presence of CD34+-expanded cells (●), ln y = − 0.18 × 10−5 x + ln 101.1 (R2 = 0.964, SE = 3.5 × 10−7,P = .121, f with 95% CI = −2.6 × 10−6to 6.3 × 10−6). In the presence of ex vivo–expanded cells (●), f was significantly lower (P < .001) than in the absence of these cells (○).

Veto activity of ex vivo–expanded CD34+ cells: determination of veto activity at different ratios of veto to responder cells

| Experiment . | CD34 veto cells (veto-responder ratio)3-150 . | MLR against donor A . | MLR against donor B . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before culture . | After culture . | CTL activity (% responding cultures)3-151 . | Veto activity (% inhibition)3-152 . | CTL activity (% responding cultures)3-151 . | Veto activity (% inhibition)3-152 . | |

| 1 | — | — | 87.5 | — | 93.75 | — |

| 0.5 | — | 18.75 | 79 | 62.5 | 33 | |

| — | 0.5 | 6.25 | 93 | 50 | 47 | |

| — | 0.25 | 18.75 | 79 | 62.5 | 33 | |

| 2 | — | — | 62.5 | — | 100 | — |

| — | 0.25 | 6.25 | 90 | 100 | 0 | |

| — | 0.125 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | |

| Experiment . | CD34 veto cells (veto-responder ratio)3-150 . | MLR against donor A . | MLR against donor B . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before culture . | After culture . | CTL activity (% responding cultures)3-151 . | Veto activity (% inhibition)3-152 . | CTL activity (% responding cultures)3-151 . | Veto activity (% inhibition)3-152 . | |

| 1 | — | — | 87.5 | — | 93.75 | — |

| 0.5 | — | 18.75 | 79 | 62.5 | 33 | |

| — | 0.5 | 6.25 | 93 | 50 | 47 | |

| — | 0.25 | 18.75 | 79 | 62.5 | 33 | |

| 2 | — | — | 62.5 | — | 100 | — |

| — | 0.25 | 6.25 | 90 | 100 | 0 | |

| — | 0.125 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | |

MLR indicates mixed lymphocyte reaction; and CTL, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte.

Responder cells and irradiated stimulator cells (from donor A or donor B) were cocultured for 5 days in the absence or presence of CD34 cells from donor A, obtained before and after culture (for 7 days in experiment 1 and 10 days in experiment 2). The responder cells were then cultured again for 7 days under limiting dilution in microtiter plates.

Wells were scored positive for CTL activity when chromium release exceeded the mean spontaneous release value by at least 3 SDs from the mean. Data are the percentages of responding cultures in experiments 1 and 2 at cell concentrations of 1 × 104and 4 × 104 responder cells/well, respectively.

Veto activity of tested cells was evaluated by assessment of their capacity to inhibit alloreactive CTL precursors in the MLR to which they were added at the indicated ratios of veto to responder cells.

Veto activity of ex vivo–expanded CD34+cells: effect on intracellular staining of IFN-γ in the effector T cells.

Responder cells and irradiated allogeneic stimulator cells were cocultured for 5 days in the absence (A and C) and presence (B and D) of cells obtained after a 12-day ex vivo expansion of CD34+ cells. The stimulator cells in the MLR (carried out at a veto-to-responder cell ratio of 0.125) were from either the donor of the CD34+ cells (A and B) or a third party (C and D). After the 5-day MLR, the cells were subjected to an additional 7-day limiting-dilution culture. The cells were then incubated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, ionomycin, and monensin; fixed; and stained for detection of the intracellular IFN-γ. Lymphocytes were gated on the basis of their forward scatter–side scatter profile. The percentage of each cell subpopulation is indicated in the relevant area of each dot plot. Shown are data from 1 of 3 experiments.

Veto activity of ex vivo–expanded CD34+cells: effect on intracellular staining of IFN-γ in the effector T cells.

Responder cells and irradiated allogeneic stimulator cells were cocultured for 5 days in the absence (A and C) and presence (B and D) of cells obtained after a 12-day ex vivo expansion of CD34+ cells. The stimulator cells in the MLR (carried out at a veto-to-responder cell ratio of 0.125) were from either the donor of the CD34+ cells (A and B) or a third party (C and D). After the 5-day MLR, the cells were subjected to an additional 7-day limiting-dilution culture. The cells were then incubated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, ionomycin, and monensin; fixed; and stained for detection of the intracellular IFN-γ. Lymphocytes were gated on the basis of their forward scatter–side scatter profile. The percentage of each cell subpopulation is indicated in the relevant area of each dot plot. Shown are data from 1 of 3 experiments.

Finally, because human CD34+ cells exhibit a specific inhibitory effect on the levels of effector T cells positive for intracellular IFN-γ, we tested the inhibitory effect of ex vivo–expanded cells in 3 experiments. In a typical experiment (Figure7), the percentage of CD3+ cells expressing IFN-γ on stimulation against stimulator cells from the donor of the CD34+ cells was 36.6% in the absence of added cells. On addition of ex vivo–expanded cells at a veto-to-responder cell ratio of 0.125, this was reduced to 9.9%. In contrast, when CD3+cells positive for IFN-γ were stimulated against cells from a third party, their levels were 59.8% in the absence of added cells and 43% on the addition of expanded cells.

Discussion

The recognition that immune barriers can be overcome by cell-dose escalation with several nonalloreactive veto cells and other facilitating cells offers an attractive approach for the induction of durable hematopoietic chimerism.1-6,23,31-36 This approach was successfully implemented in the treatment of heavily pretreated patients with leukemia, allowing engraftment of 3-loci–mismatched, CD34+ stem cell transplants from haploidentical family members.37-39 Thus, the residual host immunity previously shown to be associated with a high rate of graft rejection (mediated predominantly by CTL-p40-42) in such transplants was overcome by using large doses of CD34+ cells.

Subsequently, a study in a murine model using purified Sca-1+Lin− early progenitors found that the same concept can be applied to allow engraftment of fully mismatched hematopoietic cells in sublethally irradiated recipients, thereby overcoming a more robust residual immunity.7 Most important, durable chimerism was achieved in this study in the absence of alloreactive donor T cells and without any risk of GVHD. However, this study also showed that the number of stem cells required to attain this goal is too high and therefore may not be provided to patients by the available modalities of stem cell mobilization. Thus, the role of other nonalloreactive facilitating cells that might have a synergy with the megadose stem cell transplants in overcoming the immune barrier without producing GVHD has been promoted.7,8 24

One possibility for addressing this issue was indicated by the observation of Rachamim et al10 that cells within the human CD34+ population are endowed with veto activity. In the current study, we further characterized the veto activity of CD34+ cells, showing different attributes of these cells, including a dose-response curve, the time window in the MLR for induction of the veto effect, and the role of cell contact. We also ruled out, by removing the CD34+ cells at the end of the MLR, the possibility of an artifact that might have been caused by cold target inhibition. Thus, we fully confirmed and extended the early observation that CD34+ cells possess marked veto activity. In addition, we demonstrated that in parallel to the specific reduction in CTL-p, CD34+ cells induce specific inhibition of the levels of effector T cells positive for intracellular IFN-γ.

Considering that a large number of early myeloid progenitors can be expanded ex vivo by short-term cultures using different cytokine combinations,25-29 43-47 we hypothesized that if the veto activity could be retained along the myeloid differentiation pathway, then a small fraction of the CD34+ cells used for transplantation could provide a substantial source of veto cells. Our current results confirmed this hypothesis, demonstrating that it is possible to harvest about 28- to 80-fold more veto cells on culturing of purified CD34+ cells for 7 to 12 days with an early-acting cytokine mixture including FL, SCF, and TPO.

FACS analysis of the expanded cells revealed that the predominant phenotype of CD34+CD33− cells used at the initiation of the culture was replaced at the end of the culture by cells expressing early myeloid phenotypes such as CD34+CD33+ and CD34−CD33+. However, these maturation events were associated with a significant gain in veto activity as exemplified by the minimal ratio of veto to effector cells at which veto activity was detected. Thus, although purified unexpanded CD34+cells exhibited veto activity at a veto-to–effector cell ratio of 0.5, the expanded cells attained an equivalent activity at a ratio of 0.125. Likewise, it is noteworthy that the levels of effector cells positive for intracellular IFN-γ, which were specifically reduced by unexpanded CD34+ cells, were also markedly inhibited by the expanded cells at a CD34+- to-responder ratio of 0.125. Thus, this assay might be used as a convenient surrogate for the Cr-release assay.

The mechanism mediating the veto activity of different veto cells is still unknown. Veto activity was defined in 1980 by Muraoka and Miller11 as the capacity to specifically suppress CTL-p directed against antigens of the veto cells themselves but not against third-party antigens. Interestingly, it has been shown that some of the most potent veto cells are of T-cell origin; in particular, a very strong veto activity was documented for CD8+ CTL lines or clones.2,12-15 48-51

The specificity of the veto effect mediated by CTL clones was shown in several studies to be unrelated to their T-cell–receptor specificity.16,52,53 Although early studies emphasized the role of CD8-mediated apoptosis,16,48,54,55 more recent evidence indicated a role for Fas-FasL.56,57 Moreover, it was demonstrated by using blocking anti-CD8, by generating CTLs from FasL or perforin-mutated mice, and by gene transfer of FasL, that the veto activity of nonalloreactive CD8+ CTLs is dependent on the simultaneous expression of both CD8 and FasL.24

Preliminary data suggested that the veto activity of human CD34+ cells is also mediated by apoptosis (H.G., et al, unpublished data, January 2002); however, it seems that neither CD8 nor FasL is a likely mediator of this activity. In addition, Sca-1+Lin− mouse early progenitors were found to exhibit potent veto activity similarly to human CD34+ cells. Clearly, further elucidation of the possible mechanisms mediating the veto activity of early hematopoietic stem cells might be more easily explored in murine models because of the availability of several knockouts or mutants of key molecules.

Regardless of the mechanism involved, our new observation that CD33+ cells derived on short-term culture from CD34+CD33− cells are also endowed with veto activity is consistent with the induction of tolerance by megadose CD34+ transplants. Thus, it is possible that during the early period after transplantation, the residual host antidonor CTL-p could be made tolerant not only directly by the infused CD34+ cells but also by their CD33+ progeny, which expand exponentially and reach very large numbers in a very short time. Clearly, the probability of such CTL-p being triggered irreversibly by donor antigen-presenting cells (APCs) is proportionally inverse to the chance that transplanted CD34+ or newly formed CD33+ cells will veto the CTL-p. Considering our finding that this effect can take place only within the initial 24 hours of contact between the effector CTL-p and the APCs, the availability of veto cells during the early posttransplantation period is critical.

Our current results, which suggest that ex vivo expansion of CD34+ cells can afford about 28- to 80-fold more veto cells before the day of transplantation, could be applicable to achievement of tolerance under less intensive conditioning protocols. Currently, conventional unseparated bone marrow or peripheral blood stem cell transplants are used extensively after a nonmyeloablative conditioning in HLA-identical recipients with leukemia.58-60 These transplants are associated with significant alloreactivity because of the large number of T cells in the transplant inoculum that, in most instances, eradicate hematopoiesis in the recipient. This alloreactivity is also associated with a marked incidence of lethal GVHD. Therefore, these “minitransplants” are limited to use in patients with end-stage hematologic malignant diseases for whom a perfectly HLA-matched donor is available. The significant risk of GVHD precludes the use of nonmyeloablative hematopoietic transplants in their current form for induction of transplantation tolerance before organ transplantation or in the treatment of other, nonmalignant diseases. The availability of novel sources of veto cells such as those provided in this study by ex vivo expansion of CD34+ cells should eliminate the risk of GVHD and might contribute to the clinical realization of the important goal of tolerance induction after nonmyeloablative conditioning.

Supported in part by a grant from the Gabrielle Rich Leukemia Research Foundation. Y.R. is the incumbent of the Henry Drake Professorial Chair.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Yair Reisner, Weizmann Institute of Science, Department of Immunology, Rehovot, 76100, Israel; e-mail:yair.reisner@weizmann.ac.il.

![Fig. 2. Veto activity of CD34+ cells: the veto activity is specific for CTL-p against CD34+ donor cells. / Responder cells (1 × 106/mL) were simultaneously cultured with irradiated stimulators (0.7 × 106/mL) from the donor of the CD34+ cells (○) and a third party (▵) for 5 days in the absence (○,▵) or presence (●,▴) of CD34+ cells added at a veto-to-responder ratio of 0.4:1. The responder cells were then divided equally, and each fraction was cultured again for 7 days under limiting dilution with stimulators from the donor of the CD34+ cells (A) or stimulators from the third-party donor (B). The CTL activity was determined by51Cr-release assay with the relevant target cells. The CTL-p frequency was calculated. The parameters for the different regression lines were as follows. (A) CTL-p frequency against stimulators from the CD34+ donor in the absence of CD34+ cells (○) was ln y = − 13.8 × 10−5x + ln 118.6 (R2 = 0.955, SE(f) = 2.1 × 10−5,P = .022, f with 95% confidence interval [CI] = 4.7 × 10−5 to 2.3 × 10−4). In the presence of CD34+ cells (●), ln y = −0.84 × 10−5x + ln 102.9 (R2 = 0.873, SE(f) = 2.2 × 10-6,P = .065, f with 95% CI = − 1.3 × 10−6 to 1.8 × 10−5). In the presence of CD34+ cells (●), f was significantly lower (P < .005) than in the absence of these cells (○). (B) Anti–third-party CTL-p frequency in the absence of CD34+ cells (▵) was ln y = − 2.6 × 10−5 x + ln 103.6 (R2 = 0.982, SE(f) = 2.4 × 10−6,P = .008, f with 95% CI = 1.5 × 10−5 to 3.7 × 10−5). In the presence of CD34+ cells (▴): ln y = − 2 × 10−5 x + ln 97.8 (R2 = 0.898, SE(f) = 3.8 × 10−6,P = .014, f with 95% CI = 7.6 × 10−6 to 3.2 × 10−5). There was no significant difference between f in the presence (▴) and absence (▵) of CD34+cells (P > .1).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/99/11/10.1182_blood.v99.11.4174/6/m_h81122619002.jpeg?Expires=1765928882&Signature=Z6bQPrNDwG8soT5MNuz46adyS3l2lOBTGaKw71Y5DuEXfxTuYrVLkmQO2oQ4DjUCWxuEL8CU1pTU~wrR2jAAcE86cE5enQjq1nKdSUiSieEGlNlIZjoJwnJgBxvINW0iswr1OVczPsx9SmBhQa3mZ5CmgKJO2nttD5M9gu0~8Khani5Q0xtkckc84clP5YtzXOdkpHA51tuFNxbSeY3P~Zq7P4jPaEFhheyZb9Y1uP9C4XBSItzbrAbjNpiUYLehJKc4Ob8djK7Fm9~AL0-HQe53M-tmvMCfeCveiROSRfwxhdo~5tYiy~uqXBVY212sdHztLJ2AV7ZaGzEj8fNz8A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal