The serpin antithrombin III (AT III), the most important natural inhibitor of thrombin activity, has been shown to exert marked anti-inflammatory properties and proven to be efficacious in experimental models of sepsis, septic shock, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Moreover, clinical observations suggest a possible therapeutic role for AT III in septic disorders. The molecular mechanism, however, by which AT III attenuates inflammatory events is not yet entirely understood. We show here that AT III potently blocks the activation of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), a transcription factor involved in immediate early gene activation during inflammation. AT III inhibited agonist-induced DNA binding of NF-κB in cultured human monocytes and endothelial cells in a dose-dependent manner, suggesting that AT III interferes with signal transduction leading to NF-κB activation. This idea was supported by demonstrating that AT III prevents the phosphorylation and proteolytic degradation of the inhibitor protein IκBα. In parallel to reducing NF-κB activity, AT III inhibited the expression of interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, and tissue factor, genes known to be under the control of NF-κB. The observation that chemically modified AT III that lacks heparin-binding capacity had no effect on NF-κB activation supports the current understanding that the inhibitory potency of AT III depends on the interaction of AT III with heparinlike cell surface glycosaminoglycans. This hypothesis was underscored by the finding that the AT III β-isoform, known to have higher affinity for glycosaminoglycans, is more effective in preventing NF-κB transactivation than α–AT III. These data indicate that AT III can alter inflammatory processes via inhibition of NF-κB activation.

Introduction

Antithrombin is one of the most important endogenous regulators of coagulation, acting as the major inhibitor of thrombin and interfering with several plasma proteases such as kallikrein and factors IXa, Xa, XIa, and XIIa.1 Apart from its role in hemostasis, there is accumulating evidence that antithrombin III (AT III) exerts anti-inflammatory properties and improves survival in animal-sepsis models and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).2-4 There are a number of compelling reasons why AT III may also be an effective therapeutic agent in patients with sepsis.5-7 AT III was shown to reduce leukocyte–endothelial interaction,8 to prevent microvascular leakage,9 and to ameliorate ischemia/reperfusion injury.10 These effects, however, seem to result only in part from interference of AT III with thrombin activity because inhibition of thrombin generation alone did not prove similarly effective.11,12 The beneficial effects of AT III rather appear mainly to result from direct, thrombin-independent effects on vascular cells. AT III was found to stimulate nitric oxide synthesis in vascular smooth muscle cells,13 to inhibit migration and adhesion of neutrophils,14 and to attenuate cytokine production in monocytes and endothelial cells (ECs)15 in a thrombin-independent manner. However, despite the increasing number of reports describing direct effects of AT III on vascular cells, the molecular mechanisms underlying these effects remain to be elucidated.

In every inflammatory process, the vast majority of cellular events require nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) transcriptional activity. NF-κB proteins belong to a family of heterodimeric, sequence-specific transcription factors involved in the activation of an exceptionally large number of genes in response to inflammation and viral and bacterial infections (reviewed by Yamamoto and Gaynor16and Hatata et al17). These genes encode defense and signaling proteins, including cell surface molecules in immune function such as immunoglobulin κ light chain; class I and II major histocompatibility complex; cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, interferon-γ, tumor necrosis factor–α (TNF-α), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; as well as cell surface receptors such as tissue factor (TF), intercellular adhesion molecule-1, and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1. In unstimulated cells, NF-κB is sequestered in a cytoplasmic, inactive form bound to inhibitory IκB proteins. Various inflammatory stimuli, including viruses, antigen–receptor interactions, stress factors, cytokines, and bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPSs), induce rapid IκB dissociation and degradation and subsequently translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus, where it binds to decameric κB motifs of the consensus sequence and activates the transcription of its target genes.18 19

Despite the important role of the NF-κB pathway in septic and other inflammatory disorders and the comparatively high level of understanding we have of the entire pathway, it has so far not been investigated whether this pathway is affected by AT III. The present study, investigating the direct effect of AT III on the activation of NF-κB in vascular cells, provides new information concerning how AT III functions at the molecular level.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Monocytes.

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from buffy coats obtained from healthy blood donors by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden) and further fractionated as described previously.20Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The final cultures, suspended at a density of 1 × 106cells/mL in serum-free culture medium (RPMI 1640; GIBCO BRL), contained 90% to 95% monocytes as evidenced by Pappenheim staining and fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis, as well as nonspecific esterase staining of cytocentrifuge preparations.

Endothelial cells.

ECs were isolated from human umbilical veins with trypsin-EDTA solution according to the method of Jaffe et al.21 All experiments were performed with first-passage cells grown to confluence 2 days after seeding. All media and buffers were found to contain less than 10.0 pg/mL endotoxin by limulus amoebocyte lysate assay.

Cell viability.

Cell viability in the absence and presence of AT III was determined by ethidium bromide staining of cell aliquots and subsequent FACS analysis.

Antithrombin III

Preparation of immune-adsorbed AT III.

AT III concentrate (Kybernin P) was obtained from Aventis Behring (Marburg, Germany). AT III was further purified from Kybernin P by immune adsorption to a monoclonal antibody (mAb) bound to BrCN-Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB). In preliminary experiments, the mAb had been demonstrated to bind both isoforms with identical affinity. Spiking and column-overloading experiments had been performed to ensure that the isoform proportions of the samples applied were not altered by the immune-adsorption procedure. AT III concentrations used in the present study ranged from 0 to 30 IU/mL; by definition, 1 IU of AT III equals the amount found on average in 1 mL plasma and is equivalent to 150 μg/mL or 2.6 μM.

Separation of latent AT III and isoforms from AT III concentrate.

AT III isoforms were prepared from AT III concentrate (Kybernin P; Aventis Behring) by adsorption to Heparin-Fractogel. Twenty thousand units of AT III (Kybernin P) was dissolved in 2.0 L water for injection and pumped onto the heparin column (500 mL), which had been equilibrated with 0.015 M Na2H(PO4)-2-hydrate, 0.06 M NaH2(PO4)-2-hydrate, and 0.05 M NaCl, pH 7.2. Latent AT III was obtained by washing the column with equilibration buffer containing 0.2 M NaCl. The α-isoform of AT III was retained by increasing the ionic strength up to 0.8 M NaCl in equilibration buffer, whereas the β–AT III isoform was eluted with 2 M NaCl. Both preparations were dialyzed against 0.01 M Na-citrate, 0.15 M NaCl, pH 7.4. Concentrations were adjusted according to the respective heparin cofactor activity or AT III protein, respectively (at 150 μg/IU AT III). It had been ensured that the described procedure had no denaturing impact on the preparations.

Preparation of Trp49-blocked AT III.

A single Trp residue in AT III was chemically modified according to the method of Blackburn et al.22 Labeling of Trp49was achieved using dimethyl (2-hydroxy-5-nitrobenzyl) sulfonium bromide.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analyses of IκBα and IκBα-P were performed essentially as described before.23 Ten micrograms of cytoplasmic protein extract was separated on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Immunoblotting was done using rabbit polyclonal antibody specific for IκBα (c-21, 1:3000 dilution, 1-hour incubation; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody (sc-2004, 1:4000 dilution, 1-hour incubation; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Antibodies were diluted in phosphate-buffered saline, 5% nonfat dry milk, and 0.05% Tween. For detecting the Ser32-phosphorylated IκBα, rabbit anti-human IκBα antibody (9241S, 1:1000 dilution; New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) was used. Immunoreactive proteins were visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) Plus detection kit (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Nuclear extracts were prepared as described previously.20 NF-κB oligonucleotides (5′-AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGGC-3′) and AP-1 oligonucleotides (5′-CGCTTGATGACTCAGCCGGAA-3′) were labeled to a specific activity of greater than 5 × 107 cpm/μg DNA by end-labeling with [γ33P] dATP using T4 kinase. Oligonucleotide binding was performed in 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 60 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 4% Ficoll, 100 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.02 U calf thymus DNA, and 0.01 U poly (dI-dC) in a total volume of 20 μL. Nuclear extracts were incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature in the presence of 1 ng labeled oligonucleotide (approximately 50 000 cpm). Protein–DNA complexes were separated from the free DNA probe by electrophoresis on a 4% native polyacrylamide gel in 0.25× Tris boric acid EDTA buffer and subjected to autoradiography. Band intensities were quantified by densitometric analysis.

RNA isolation and reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction

Total cellular RNA was isolated by the acid guanidinum thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform method, as described by Chomczynski and Sacchi.24 Preparation of complementary DNA and subsequent PCR were performed as described previously.20 Sequences of intron spanning TF-specific primers were: sense, 5′-GCCGCCAACTGGTAGACATG-3′, and antisense, 5′-TAGCCAGGATGATGACAAGG-3′; and for the housekeeping gene β-actin: sense, 5′-AAAGACCTGTACGCC-3′, and antisense, 5′-CGTCATACTCCTGCTTGCTGATCCACATCTG-3′. Negative controls were performed routinely by running PCR without cDNA to exclude false-positive amplification products. The specificity of the obtained TF PCR products was verified by subjecting the related PCR product to automated DNA sequencing (model 373A; Applied Biosystems,Überlingen, Germany), essentially as described by the manufacturer, and comparing the resulting cDNA sequence with the published human TF cDNA sequence.25

Quantification of IL-6 and TNF-α secretion

IL-6 and TNF-α protein levels from monocyte culture supernatants were measured quantitatively using a commercially available, specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (IL-6: R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN; TNF-α: Hölzel, Köln, Germany). Serial dilutions of the corresponding recombinant cytokine provided standard curves for each individual ELISA plate. Absorbance was measured at 490 nm using an ELISA reader. The quantification was performed in duplicate.

Statistical methods

Data are described as mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance was estimated with Studentt test. Differences were assumed to be statistically significant at P < .05.

Results

AT III inhibits NF-κB activation in monocytes and ECs in a dose-dependent manner

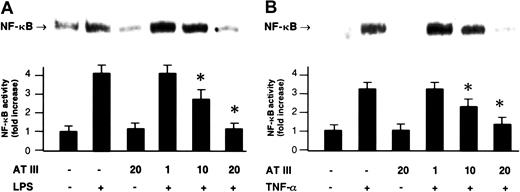

NF-κB was induced by treatment with LPS (monocytes) or TNF-α (ECs), both well-known NF-κB–activating agents in these cell types. This induction was shown by the appearance in nuclear extracts of the DNA-binding activity of NF-κB using electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) (Figure 1). The induction of NF-κB was prevented when AT III was present in the cell culture medium. Preincubation with AT III led to a dose-dependent inhibition of the agonist-induced DNA-binding activity of NF-κB in both monocytes and ECs, whereby 20 U/mL AT III entirely abrogated the NF-κB response to either LPS or TNF-α (Figure 1). Moreover, AT III (20 U/mL) was also found to suppress the low baseline NF-κB binding activity detected in unstimulated cells (Figure 1). The inhibitory effect was not due to any toxic effect on cells, as evidenced by ethidium bromide staining (data not shown).

Effect of AT III on NF-κB activation in monocytes and ECs.

Cells were either untreated or pretreated for 2 hours with the indicated concentrations of AT III, followed by a 1-hour stimulation with either LPS (monocytes; 10 μg/mL) (A) or TNF-α (ECs; 40 ng/mL) (B) in the presence and absence of AT III. Nuclear proteins from monocytes and ECs were analyzed by EMSA for binding to an oligonucleotide containing the NF-κB consensus sequence. Representative photographs of EMSA gels are shown in the upper panels. In the lower panels, a quantitation of the inhibiting effect of AT III on the agonist-induced binding activity is given. Band intensities corresponding to the NF-κB–DNA complexes were quantified by densitometric analysis using a Bio-Imaging analyzer. Values represent means ± SEM from 9 independent experiments (each cell type). *P < .01 versus stimulation in the absence of AT III.

Effect of AT III on NF-κB activation in monocytes and ECs.

Cells were either untreated or pretreated for 2 hours with the indicated concentrations of AT III, followed by a 1-hour stimulation with either LPS (monocytes; 10 μg/mL) (A) or TNF-α (ECs; 40 ng/mL) (B) in the presence and absence of AT III. Nuclear proteins from monocytes and ECs were analyzed by EMSA for binding to an oligonucleotide containing the NF-κB consensus sequence. Representative photographs of EMSA gels are shown in the upper panels. In the lower panels, a quantitation of the inhibiting effect of AT III on the agonist-induced binding activity is given. Band intensities corresponding to the NF-κB–DNA complexes were quantified by densitometric analysis using a Bio-Imaging analyzer. Values represent means ± SEM from 9 independent experiments (each cell type). *P < .01 versus stimulation in the absence of AT III.

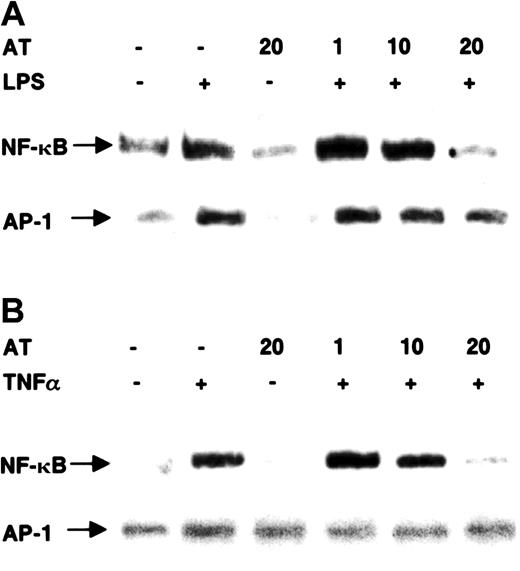

AT III specifically inhibits NF-κB activation

To test whether AT III is a specific inhibitor of NF-κB, we also analyzed nuclear extracts from AT III–treated cells for the DNA-binding activity of the transcription factor AP-1 (Figure2). Treatment of monocytes with LPS or of ECs with TNF-α induced NF-κB binding, which was strongly blocked by 20 U/mL AT III. In the same extracts, AT III could not prevent the induction of AP-1 binding activity.

Effect of AT III on DNA-binding activity of NF-κB and AP-1 in monocytes and ECs.

Cells were pretreated for 2 hours with different concentrations of AT III, followed by a 1-hour stimulation with either LPS (monocytes; 10 μg/mL) (A) or TNF-α (ECs; 40 ng/mL) (B) in the presence and absence of AT III. Nuclear extracts were analyzed by EMSA with33P-labeled DNA probes detecting κB and AP-1 binding activities, respectively. Representative photographs of EMSA gels are shown. Complexes tested for specific binding are indicated by arrows.

Effect of AT III on DNA-binding activity of NF-κB and AP-1 in monocytes and ECs.

Cells were pretreated for 2 hours with different concentrations of AT III, followed by a 1-hour stimulation with either LPS (monocytes; 10 μg/mL) (A) or TNF-α (ECs; 40 ng/mL) (B) in the presence and absence of AT III. Nuclear extracts were analyzed by EMSA with33P-labeled DNA probes detecting κB and AP-1 binding activities, respectively. Representative photographs of EMSA gels are shown. Complexes tested for specific binding are indicated by arrows.

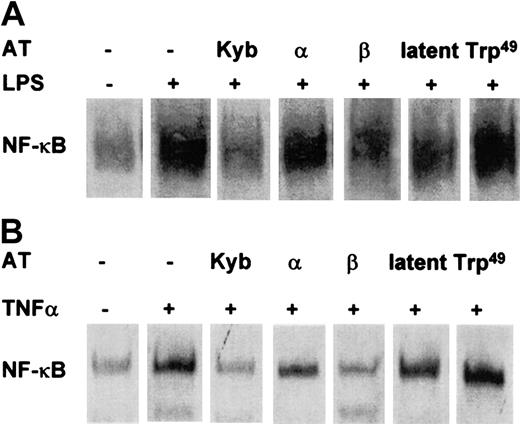

Inhibition of NF-κB involves the heparin-binding site of AT III

Whereas both the AT III plasma-derived concentrate and immune-adsorbed AT III potently prevented NF-κB induction, Trp49-modified AT III, which lacks heparin-binding properties, had no effect (Figure 3). The hypothesis that the inhibitory effect of AT III on NF-κB activation involves an interaction with heparinlike proteoglycans was supported by the observation that the AT III β-isoform, known to have high affinity to cell surface proteoglycans, displayed a more effective suppression of NF-κB induction in intact cells than was observed for the AT III α-isoform, which has a lower affinity to heparan sulfate proteoglycans (Figure 3). Latent AT III displayed only a small effect on NF-κB activity.

Effect of Trp49-modified AT III, latent AT III, β–AT III, and α–AT III on NF-κB activation in monocytes and ECs.

Cells were pretreated for 2 hours with the indicated AT compounds, followed by a 1-hour stimulation with LPS (monocytes; 10 μg/mL) (A) or TNF-α (ECs; 40 ng/mL) (B) in the presence and absence of the compounds. Nuclear proteins from monocytes and ECs were analyzed by EMSA for binding to an oligonucleotide containing the NF-κB consensus sequence.

Effect of Trp49-modified AT III, latent AT III, β–AT III, and α–AT III on NF-κB activation in monocytes and ECs.

Cells were pretreated for 2 hours with the indicated AT compounds, followed by a 1-hour stimulation with LPS (monocytes; 10 μg/mL) (A) or TNF-α (ECs; 40 ng/mL) (B) in the presence and absence of the compounds. Nuclear proteins from monocytes and ECs were analyzed by EMSA for binding to an oligonucleotide containing the NF-κB consensus sequence.

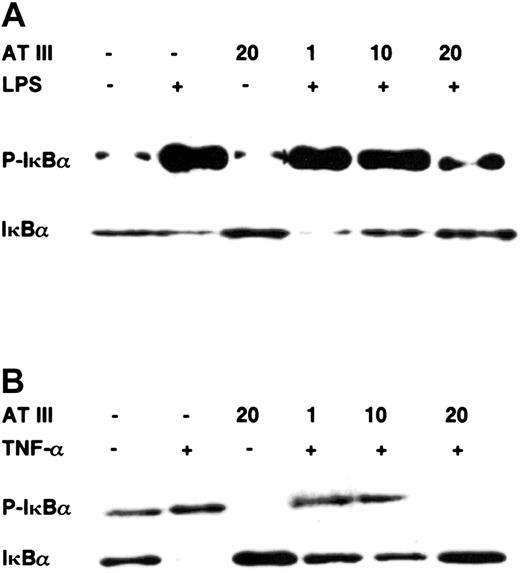

AT III interferes with IκBα degradation

Pathologic stimuli such as LPS or TNF-α induce translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus by phosphorylation of its inhibitory protein IκBα, which is then ubiquitinated and rapidly degraded by the 26S proteasome.19 Therefore, to examine the fate of IκBα upon stimulation after AT III treatment, we assayed IκBα degradation and phosphorylation by immunoblotting. Figure 4 shows that preincubation with AT III prevented agonist-induced IκBα degradation in a dose-dependent manner in both cell types. The loss of cytoplasmic IκBα was consistent with the occurrence of phosphorylated IκBα 15 minutes after stimulation, as monitored by immunoblot analysis using antibodies specific for the Ser32-phosphorylated form of IκBα. However, when stimulation was performed in the presence of AT III, reduced phosphorylated IκBα was detected in both monocytes and ECs. Again, not only did AT III block IκBα phosphorylation in stimulated cells, but it also suppressed the basal phosphorylation rate of IκBα in unstimulated cells. In conclusion, AT III seems to be a useful agent allowing interference with the mobilization of NF-κB by suppressing IκBα degradation in vascular cell types.

Effect of AT III on the agonist-induced phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα in monocytes and ECs.

Cells were pretreated for 2 hours with the indicated concentrations of AT III, followed by stimulation with either LPS (monocytes; 10 μg/mL) (A) or TNF-α (ECs; 40 ng/mL) (B) in the presence and absence of AT III. Cytoplasmic proteins were prepared, and immunoblotting was performed for the phosphorylated form of IκBα (P-IκBα) and for IκBα. In each case, data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Effect of AT III on the agonist-induced phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα in monocytes and ECs.

Cells were pretreated for 2 hours with the indicated concentrations of AT III, followed by stimulation with either LPS (monocytes; 10 μg/mL) (A) or TNF-α (ECs; 40 ng/mL) (B) in the presence and absence of AT III. Cytoplasmic proteins were prepared, and immunoblotting was performed for the phosphorylated form of IκBα (P-IκBα) and for IκBα. In each case, data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

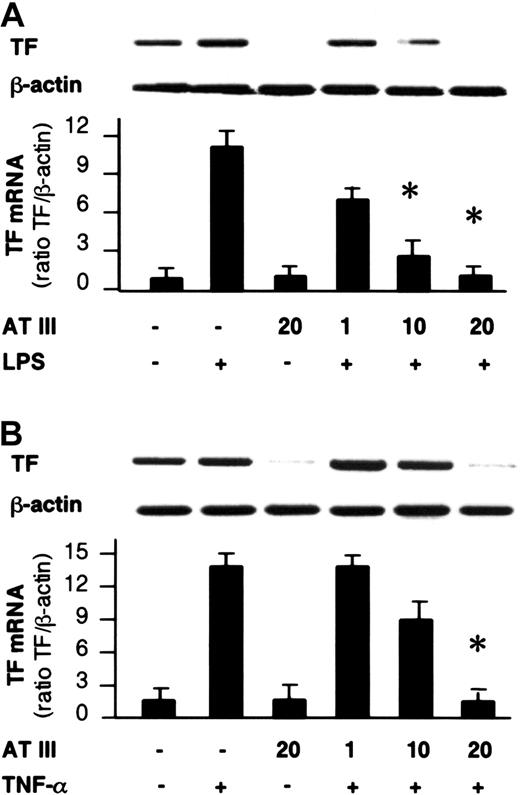

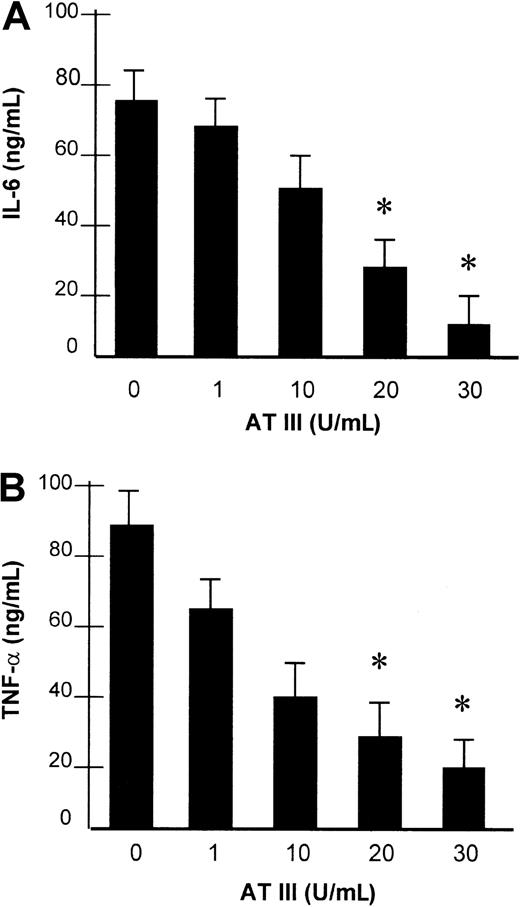

AT III affects NF-κB–controlled gene expression

The impact of AT III observed on NF-κB binding activity led us to investigate whether AT III affects the induction of NF-κB–controlled genes in monocytes and ECs. For this purpose, the transcription of the TF gene and the secretion of IL-6 and TNF-α were analyzed in both cell types and were assayed by reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and ELISA, respectively, upon stimulation of cells in the presence or absence of AT III. As shown in Figure 5, stimulation of cells resulted in strong induction of TF mRNA expression, which was suppressed by AT III in a dose-dependent manner to nearly baseline levels. Additionally, monocytes showing negligible basal IL-6 and TNF-α secretion exhibited a several-fold increase in cytokine secretion after LPS stimulation (Figure6). Pretreatment of cells with AT III reduced LPS-induced IL-6 and TNF-α production in a dose-dependent manner to a very low level. This indicates that the proinflammatory activation of cells is abolished if AT III is present in the culture medium in sufficient concentrations.

Effect of AT III on TF gene expression in monocytes and ECs.

Cells were pretreated for 2 hours with the indicated concentrations of AT III, followed by stimulation with either LPS (monocytes; 10 μg/mL) (A) or TNF-α (ECs; 40 ng/mL) (B). Cells were harvested after 4 hours of stimulation, and RT-PCR was performed with primers specific for TF or β-actin gene. A representative ethidium bromide visualization of TF and β-actin mRNA is given in the upper panel. Relative values of TF mRNA (normalized to β-actin) are given in the lower panel. The values represent means ± SEM of 4 independent experiments. *P < .01 versus stimulation in the absence of AT III.

Effect of AT III on TF gene expression in monocytes and ECs.

Cells were pretreated for 2 hours with the indicated concentrations of AT III, followed by stimulation with either LPS (monocytes; 10 μg/mL) (A) or TNF-α (ECs; 40 ng/mL) (B). Cells were harvested after 4 hours of stimulation, and RT-PCR was performed with primers specific for TF or β-actin gene. A representative ethidium bromide visualization of TF and β-actin mRNA is given in the upper panel. Relative values of TF mRNA (normalized to β-actin) are given in the lower panel. The values represent means ± SEM of 4 independent experiments. *P < .01 versus stimulation in the absence of AT III.

Effect of AT III on LPS-induced secretion of IL-6 and TNF-α.

Monocytes were preincubated with AT III for 2 hours, as indicated, and then stimulated with 10 μg/mL LPS for 8 hours. IL-6 (A) and TNF-α (B) protein levels from cell supernatants were measured by ELISA. Values represent means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments, with assays performed in duplicate. *P < .01 versus stimulation in the absence of AT III.

Effect of AT III on LPS-induced secretion of IL-6 and TNF-α.

Monocytes were preincubated with AT III for 2 hours, as indicated, and then stimulated with 10 μg/mL LPS for 8 hours. IL-6 (A) and TNF-α (B) protein levels from cell supernatants were measured by ELISA. Values represent means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments, with assays performed in duplicate. *P < .01 versus stimulation in the absence of AT III.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that AT III is a potent endogenous regulator allowing for interference with the mobilization of NF-κB in various vascular cell types. AT III was shown to be a specific inhibitor of NF-κB, blocking the induction of NF-κB but not of other transcription factors investigated in the present study, independently of the inducing agent and cell type. The inhibitory effect was found to have its molecular basis in the reduction of the phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of the NF-κB inhibitor protein IκBα. The data suggest that the inhibitory effect of AT III involves the interaction of AT III with heparinlike glycosaminoglycans on the cellular surface.

Simultaneous activation of the coagulation system is an almost invariable consequence of local or systemic inflammation. This interaction of coagulation and inflammation, which may have developed from evolutionary forces favoring survival of individuals able to localize and to contain the source of injury or infection, involves several mechanisms in which, on the one hand, inflammatory processes can activate coagulation, and, conversely, coagulation influences inflammation (for review, see Opal26). The interaction of coagulation and inflammation is evident from observations that several components of the coagulation system can, for example, stimulate inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α; up-regulate adhesion molecules; and promote neutrophil rolling or smooth muscle cell proliferation, all of which are important events in tissue inflammation.27,28 Anticoagulant proteins, on the other hand, may have the ability to completely change the behavior of immune or vascular cells.29,30 Among the natural anticoagulants, AT III has been proven to exert, in addition to its anticoagulant activities, potent anti-inflammatory effects in animal models and clinical studies2-6 and to improve the clinical outcome of patients with severe sepsis when given in high doses.7 These beneficial effects of AT III do not entirely result from inhibition of thrombin because selective inhibition of thrombin generation did not prove to have similar effectiveness.11,12 The anti-inflammatory potency of AT III rather may rely on thrombin-independent effects on various cell types because AT III was shown to directly affect T- and B-cell activation,31 to reduce neutrophil migration,14 and to inhibit endotoxin-induced TF production by mononuclear cells in vitro.32 The molecular basis of the direct cellular anti-inflammatory effects of AT III, however, so far was unknown.

The results of the present study suggest a decrease in the rate of transcription of NF-κB–controlled genes as a probable mechanism by which AT III attenuates inflammatory processes. The NF-κB transcription factor, an immediate early mediator of immune and inflammatory responses, has specialized in the organism to rapidly induce the synthesis of genes that encode defense and signaling molecules in response to a wide variety of inflammatory stimuli, such as LPS, viruses, stress factors, and cytokines.17 However, although NF-κB is crucial to inflammatory gene regulation, to our knowledge it has not previously been investigated in detail whether NF-κB might be influenced by AT III treatment.

In this study, we investigated whether AT III affects agonist-induced induction of NF-κB in cell cultures. By all criteria tested, AT III proved to be a potent and specific inhibitor of NF-κB induction in intact cells. (1) Inhibition of NF-κB induction by AT III in vitro was observed with concentrations comparable to those AT III levels that have been documented to improve survival and to attenuate inflammatory responses in baboons lethally challenged with Escherichia coli.33 (2) AT III had no cytotoxic effect for at least 36 hours when used in cell cultures in the given concentrations. (3) AT III did not reduce the DNA-binding activity of the transcription factor AP-1. (4) AT III interfered with the induction of NF-κB by all stimulating agents and in both cell lines tested. (5) Active AT III, but not inactivated AT III (in terms of heparin binding), could prevent NF-κB induction. (6) The eluted immune-adsorbed AT III exhibited similar effectiveness, excluding the possibility that the inhibitory effect of AT III concentrate was due to the impact of potential trace impurities theoretically copurified from plasma. Although the finding that the pathway to NF-κB, but not the one to AP-1, is responsive to AT III seems to suggest that AT III is a specific inhibitor of NF-κB, we cannot definitely exclude the possibility that AT III might also affect other signaling pathways not investigated in the present study.

Blockade of NF-κB was observed with concentrations of AT III that were in the same range of recently reported in vitro investigations by Souter et al,15 which also demonstrated inhibitory effects on inflammatory cell activation at concentrations of 20 IU/mL, which equals 20 times physiologic plasma levels. In the latter study, effective AT III concentrations decreased with increasing complexity of the system, meaning that considerably lower AT III levels were required in the whole-blood system, which lay in the pharmacologic (supranormal) range of plasma levels detected in recent clinical trials.34 Accordingly, it seems conceivable that the efficiency of AT III to reduce NF-κB activation reported in the present study also is more significant if considered in a complex milieu, as found under in vivo conditions.

Because cell–cell contact and cross-talk between monocytes and endothelium are believed to play central roles in the interaction of coagulation and inflammation during septic disorders and DIC, we tested whether AT III is able to suppress the induction of NF-κB–regulated genes in monocytes and ECs. Indeed, AT III proved to potently block TNF-α agonist-induced TF gene transcription in monocytes and ECs and to inhibit the production of TNF-α and IL-6 in monocytes stimulated with LPS, known to be a strong inducer of NF-κB in those cells.

Next we analyzed in more detail the molecular basis of the inhibitory action of AT III. In resting cells, NF-κB is present in an inactive form, typically sequestered in the cytoplasm by an inhibitory protein of the IκB(s) family. Stimulation of cells by a wide variety of immune or inflammatory mediators induces rapid IκB phosphorylation and degradation and, subsequently, NF-κB translocation to the nucleus, where it binds to DNA.18 19 Both phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα in response to exogenous stimulation were found to be sharply reduced when cells were pretreated with AT III, suggesting that AT III functions to attenuate the cellular NF-κB response at the level of IκBα. The precise mechanism by which AT III prevents IκBα phosphorylation remains to be elucidated.

In this regard, an important observation might be that the β-isoform of AT III was found to be more effective in reducing NF-κB activation than the α–AT III isoform. This observation might deserve particular attention because the β-isoform, lacking glycosylation at position Asn135, is known to bind heparin with greater avidity and glycosaminoglycans with higher affinity than the fully glycosylated α–AT III.35 Because all cell culture experiments in the present study were performed in the absence of heparin, thereby excluding the possibility that NF-κB inhibition by AT III might be catalyzed by heparin, the enhanced potency of β–AT III might indicate that the inhibitory action of AT III is related to binding of AT III to heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans (or heparinlike structures) on the cell surface. This hypothesis is strongly supported by the finding that Trp49-modified AT III, which nearly completely lacks heparin-binding capacity, had absent or negligible effects on the induction of NF-κB no matter which agonist or which cell type was tested. These data are in line with the results of previous investigations demonstrating that cleavage of heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans by treatment with heparinase not only abolishes the inhibitory effect of AT III on neutrophil migration in vitro, but also abrogates the beneficial anti-inflammatory properties of AT III in vivo.14 The concept that the anti-inflammatory potency of AT III depends on an interaction of its heparin-binding site with cell surface receptors might also provide a plausible explanation for a surprising lesson from a recent large-scale phase 3 clinical trial, investigating whether AT III reduces mortality in patients suffering from severe sepsis. In this multicenter trial, contrary to the promising positive results of several prospective phase 2 clinical studies,5-7 the use of AT III failed to achieve efficacy in the primary study end point of 28-day all-cause mortality.34 A possible survival benefit of AT III was observed only in the specific subgroup of patients not receiving concomitant heparin. Given that in patients treated with both AT III and heparin, heparin achieved plasma concentrations sufficient to block AT III heparin-binding sites shown to be necessary for mediating the AT III effect in inhibitory intracellular signaling, this might provide an explanation for why AT III did not show the expected beneficial effects in this clinical trial.

Further studies are required to investigate, on the one hand, whether a distinct receptor for AT III exists among cell surface molecules related to the family of heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans, and, on the other hand, whether the β–AT III isoform without concomitant heparin prophylaxis might further improve the treatment of inflammatory events such as DIC.

We would like to thank B. Parviz for excellent technical assistance.

Supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), Sonderforschungsbereich 547, and by the Gesellschaft für Thrombose- und Hämostaseforschung (GTH). C.O. is a scholar of the DFG-Graduiertenkolleg 534.

J.R. and H.S. are employed by Aventis whose product was studied in the present work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Hans Hölschermann, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Giessen, Klinikstrasse 36, D-35392 Giessen, Germany; e-mail:hans.f.hoelschermann@innere.med.uni-giessen.de.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal