In the present study we investigated whether endothelial microparticles (EMPs) can bind to monocytic THP-1 cells and modulate their procoagulant properties. Using flow cytometry, we demonstrated that EMPs express adhesive receptors similar to those expressed by activated endothelial cells. Expression of endothelial antigens by THP-1 cells incubated with EMP was shown by immunoperoxidase staining and flow cytometry using antibodies directed against E-selectin, VCAM-1, and endoglin. EMP binding to THP-1 cells was time- and concentration- dependent, reached a plateau at 15 minutes, and had an EMP-to-monocyte ratio of 50:1. EMP binding was not affected by low temperature and was not followed by the restoration of phosphatidylserine asymmetry, suggesting that adhesion was not followed by fusion. A 4-hour incubation of THP-1 cells with EMP led to an increase in procoagulant activity as measured by clotting assay. Concomitantly, THP-1 exhibited increased levels of tissue factor (TF) antigen and TF mRNA compared to control cells. The ability of EMP to induce THP-1 procoagulant activity was significantly reduced when THP-1 cells were incubated with EMP in the presence of blocking antibodies against ICAM-1 and β2 integrins. These results demonstrate that EMPs interact with THP-1 cells in vitro and stimulate TF-mediated procoagulant activity that is partially dependent on the interaction of ICAM-1 on EMP and its counterreceptor, β2 integrins, on THP-1 cells. Induction of procoagulant activity was also demonstrated using human monocytes, suggesting a novel mechanism by which EMP may participate in the dissemination and amplification of procoagulant cellular responses.

Introduction

Under physiological conditions, the endothelium provides a thromboresistant surface that maintains blood fluidity and prevents thrombus formation.1,2 In response to injury or activation, it is shifted toward a prothrombotic state resulting from different mechanisms. Activated endothelial cells display a decreased level of anticoagulant surface molecules such as thrombomodulin, and they express tissue factor (TF), the main stimulus for thrombin generation.3-5 Endothelial activation is also associated with enhanced leukocyte recruitment through the expression of adhesion molecules such as E-selectin, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1, which interact with leukocyte ligands mainly belonging to integrin family adhesion molecules.6 These cell contacts play a major role in amplifying coagulation events through the induction of TF.7,8 Recently we have demonstrated that the release of procoagulant microparticles originating from activated endothelial cells9 could constitute a novel pathway of prothrombotic response.

Membrane microparticles (MPs) are a hallmark of cellular alteration. MPs are shed from the plasma membrane of most eukaryotic cells undergoing activation or apoptosis. They result from an exocytotic budding process that translocates phosphatidylserine from the inner to the outer leaflet of the cell membrane. This inversion of membrane polarity is followed by blebbing of the membrane surface, leading to the formation of MPs and their release in the extracellular environment.10,11 Even if there is no real consensus on MP definition, it is accepted that MPs are submicron elements (from 0.1 to 1 μm) that express at their surfaces phosphatidylserine and membrane antigens characteristic of their cell of origin.12 13

Most studies have focused on MPs derived from blood cells, with a large interest on those derived from platelets and leukocytes. However, the functional role of MPs is still largely unknown. Several lines of evidence suggest that they could play a role in the control of coagulation. Surface exposure of phosphatidylserine on MPs derived from in vitro–stimulated cells provides catalytic surface that supports the formation of activated clotting enzymes (ie, tenase and prothombinase complexes).14,15 This procoagulant potential is corroborated by clinical studies showing elevated levels of circulating MPs in patients with an increased risk for thromboembolic events (ie, patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, myocardial infarction, diabetes, or disseminated intravascular coagulation).16-19 In addition, studies performed with MP fractions isolated from plasma of patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass or extracted from atherosclerotic plaques have demonstrated that MPs produced in vivo retain a thrombin-generating activity.20 21

In addition to their direct effect on the promotion and the amplification of the coagulation cascade, MPs participate in a variety of intercellular adhesion processes and induce cellular responses. Platelet MPs activate platelets and endothelial cells through the transcellular delivery of arachidonic acid.22 Moreover, platelet MPs increase the adherence of monocyte to endothelial cell by the up-regulation of adhesion molecules on both cell types.23 They also interact with extracellular matrix proteins such as fibrinogen, thereby promoting platelet adhesion.24 More recently, these MPs have been shown to enhance vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation by stimulating a mitogenic signaling pathway.25

Little is known about the function of MPs derived from endothelial cells. Our recent data indicated that, on stimulation with inflammatory cytokines, cultured endothelial cells shed MPs.9 Their procoagulant potential has already been documented, but nothing is known about their capacity to interact with circulating cells. The importance of endothelium–monocyte interaction in the promotion of prothrombotic TF-dependent pathway led us to investigate whether endothelial microparticles (EMPs) might also interact with monocytic cells and stimulate their procoagulant activity.

Materials and methods

Reagents and monoclonal antibodies

Human recombinant tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) was from RD Systems (Abington, United Kingdom). The following monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were purchased from Beckman Coulter Immunotech (Marseilles, France): mAb to vitronectin receptor (anti-αvβ3, CD51, clone AMF7, IgG1), mAb to PECAM-1 (CD31, clone 1F11, IgG1), mAb to E-selectin (CD62E, clone 1.2B6, IgG1), mAb to VCAM-1 (CD106, clone 1G11, IgG1). mAbs to ICAM-1 (CD54, IgG1) and to endoglin (CD105, IgG1) were from Biocytex (Marseilles, France). Irrelevant isotype-matched mAb IgG1 (clone 679.1MC7) and blocking mAbs to integrins LFA-1 (CD11a, IgG1), CR3 (CD11b, IgG1), P150 (CD11c, IgG1), and VLA-4 (CD49d, IgG1) were from Beckman Coulter Immunotech. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated annexin V was purchased from Beckman Coulter Immunotech. FITC-F(ab′)2 goat anti-mouse IgG (FITC-Fab) and PE-F(ab′)2 goat anti-mouse IgG were purchased from Silenus (Eurobio, Les Ullis, France). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Escherichia coli 026.B6), and n-octyl-glucopyranoside were from Sigma (St Louis, MO).

Cell culture and monocyte preparation

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were prepared according to the method of Jaffe et al,26 as previously described. They were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies, Paisley, United Kingdom) containing 20% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) (Life Technologies), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 100 U/mL penicillin, 50 IU/mL heparin, and 50 μg/mL endothelial growth supplement (Sigma). HUVECs were selected for experimental use at the first passage and were subcultured into 150-cm2 gelatin-coated culture flasks.

THP-1 cells, a human monocytic cell line obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD), were grown in tissue culture flasks in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 25 mM HEPES, and antibiotics (100 U/mL penicillin, 50 μg/mL streptomycin). THP-1 cell density was kept between 1 × 106 and 5 × 106 cells/25 cm2.

Peripheral blood of healthy donors was obtained by venipuncture, using EDTA as the anticoagulant. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque density-gradient centrifugation (MSL 1077; Eurobio), washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and resuspended in endotoxin-free RPMI 1640 supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, antibiotics, and 25 mM HEPES. Monocytes were purified by allowing them to adhere to 24-well tissue culture plates for 1 hour at 37°C as previously described.27 Nonadherent cells were removed by washing, and monocytes were removed by scraping. This procedure yielded cells composed of approximately 90% monocytes, as determined by CD14 staining and subsequent flow cytometry analysis.

Generation and harvesting of EMPs

EMPs were prepared as previously described.9Briefly, confluent HUVEC monolayers were incubated for 48 hours with 100 ng/mL TNF-α. Culture supernatants from flasks containing 12 × 106 cells were collected and cleared from detached cells or large cell fragments by centrifugation at 4300g for 5 minutes. The supernatant was then ultracentrifuged at 20 000g for 120 minutes at 10°C. Pelleted EMPs were washed 2 times with PBS, then resuspended in 200 μL cell culture PBS and used immediately. EMP preparations were checked for LPS contamination using the Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (Endochrome; Charles River Endosafe, Charleston, WV) showing that endotoxin content was 0.5 EU/mL or less (0.05 ng/mL). In addition, to further exclude traces of endotoxin contamination, EMP samples were pretreated with 50 μg/mL polymixin B before they were added to monocytic cells. In some experiments, supernatant resulting from the last wash was used as control. This supernatant was free of EMP, as attested by flow cytometry analysis (data not shown).

Flow cytometry analysis of EMPs

Aliquots of 10 μL EMP suspension were labeled according to 2 different protocols. First, EMPs were labeled by phosphatidylserine probing using 5 μL annexin V–FITC diluted 1:50 in annexin buffer. Incubation was carried out for 15 minutes in the dark at room temperature. This protocol was used to determine the total number of EMPs in the suspension. Second, EMPs were labeled by indirect immunofluorescence after 30-minute incubation with the first-layer mAb (10 μL, 25 μg/mL) or a mixture of 3 mAbs (VCAM-1, endoglin, E-selectin: 3End mAbs) at 4°C, followed by 30-minute incubation with the second-layer FITC-F(ab)'2 (50 μL, 1:200 dilution). In each experiment, control labeling was performed by incubating EMPs with isotype control or annexin V in the appropriate buffer. Labeled EMPs were then diluted in 1.5 mL PBS and analyzed by flow cytometry on a Coulter Epics XL (Coultronics, Margency, France). The light scatters and fluorescence channels were set at logarithmic gain. Regions corresponding to shed MPs were defined using forward light scatter (FSC) versus side-angle light scatter (SSC) intensity dot-plot representation. MP gate was defined by excluding the first FSC channel that contained most of the background noise and by including 0.8-μm latex beads. Only events included within this gate were further analyzed for fluorescence associated with irrelevant and specific labeling on an FL1/SSC cytogram. Consequently, EMPs were defined as elements smaller than 1 μm that were positively labeled by specific mAbs or annexin V–FITC. For EMP numeration, a determined number of calibrated 3-μm latex beads (Sigma) was added to the sample, as an internal standard, as previously described.9 For each marker, results were expressed as the proportion of positively labeled MPs among the total number of annexin V–positive EMPs. For double labeling, EMPs were stained with 3End mAb cocktail or isotype control followed by incubation with 10 μL goat anti-mouse IgG-PE (1:40 dilution). Annexin V–FITC was added 15 minutes before the end of incubation, and EMPs were resuspended in annexin buffer before flow cytometry analysis.

Binding assay

EMPs were added to THP-1 cells in 24-well plates in culture medium and were incubated at 37°C or 4°C for 5 minutes to 1 hour. The number of EMPs ranged from 0 to 100 EMPs per THP-1 cell. After incubation, THP-1 was washed 3 times with PBS–1% bovine serum albumin. Each washing step included centrifugation at 1000gfor 5 minutes to remove nonadherent EMPs.

THP-1–EMP adhesion was visualized by immunocytochemistry. After 15-minute incubation with EMPs, washed THP-1 cells were cytocentrifuged over slides and air dried. Immunostaining was performed according to the avidin–biotin–peroxidase procedure using the histo-stain plus kit (Zymed, San Francisco, CA). Samples were fixed with acetone for 5 minutes and were incubated sequentially for 10 minutes each with 3% hydrogen peroxide, blocking reagent containing 10% human serum, primary antibody, biotinylated secondary antibody, streptavidin–peroxidase conjugate, and AEC chromogenic substrate resulting in a brown reaction product. Primary antibody was a mixture of 3 mAbs directed against VCAM-1 (CD106), E-selectin (CD62E), and endoglin (CD105), called 3End mAbs used at 50 μg/mL. Isotype-specific irrelevant antibody at the same concentration was used as control.

Measurement of binding of EMPs to THP-1 cells was also analyzed by flow cytometry. After incubation with EMPs, THP-1 cells were washed 3 times with PBS and were labeled by the indirect immunofluorescence method. Cells were incubated with 3End mAbs at 50 μg/mL or with an isotype control at the same concentration, washed twice, incubated with FITC-Fab, and analyzed by flow cytometry. In some experiments, to detect EMPs on THP-1 cell surfaces, THP-1 cells were labeled with annexin V–FITC according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Measurement of procoagulant activity

THP-1 cells (5 × 104) or monocytes (15 × 104) were incubated for 15 minutes or 4 hours with, respectively, 2.5 × 106 or 7.5 × 106 EMPs resuspended in PBS or with control culture medium alone. A positive stimulation control was performed with 5 μg/mL and 1 μg/mL LPS (Sigma), respectively, for THP-1 cells and monocytes. After 3 washes, cells were disrupted using lysing buffer (0.15 M NaCl, 25 mM HEPES, 15 mM n-octyl-glucopyranoside) at 37°C for 15 minutes, and their procoagulant properties were evaluated by a plasma recalcification time assay. Briefly, 100 μL normal plasma was mixed with 50 μL cell suspension and was incubated for 5 minutes in a 37°C warmed water bath. Then 100 μL of 0.025 M CaCl2was added, and the clotting time was recorded. Clotting times were converted to thromboplastin equivalents by reference to a standard curve established by serial dilutions of human thromboplastin preparation (Thromborel S; Dade Behring, Marburg, Germany). A value of 1000 arbitrary units (au) was given to a 1/400 dilution of this preparation, which clotted human plasma in 60 seconds. All clotting assays were carried out in triplicate. Procoagulant activity was characterized as TF using a factor VII–deficient plasma (Diagnostica, Stago, Asnières, France). In some experiments, procoagulant activity of THP-1 cells was analyzed after 4-hour incubation with EMPs in the presence of blocking monoclonal antibodies directed against adhesion molecules or isotype control using a final concentration of 40 μg/mL.

Measurement of TF protein level

THP-1 cells (2 × 105 cells) were incubated with EMPs (ratio, 1:50 THP-1–EMP) for 15 minutes to 4 hours, washed 3 times with PBS, and lysed with 100 μL lysis buffer, 50 nM Tris HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, and 1% NP40 supplemented with proteolysis inhibitors for 20 minutes on ice before TF antigen levels were measured in cell lysates. The TF enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Immubind) was purchased from American Diagnostica (Greenwich, CT). The quantity of antigen was expressed in pg/mL cell lysate.

Analysis of TF mRNA expression

Controls THP-1 and THP-1, incubated with EMPs for 30 minutes to 3 hours, were washed by PBS and immediately processed for RNA isolation. This procedure was carried out at room temperature using RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The concentration of total RNA was determined by spectrophotometry. Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) amplification of TF mRNA was processed by a single-step method using the Superscript One-Step RT-PCR system kit (Life Technologies, Paisley, United Kingdom). Sequences of TF-specific primers were TF D (sense) 5′ GGC GCT TCA GGC ACT ACA A 3′and TF R (antisense) 5′CTC CTT TAT CCA CAT CAA TC 3′. For control purposes, primers for the housekeeping gene G3PDH, G3D (sense) 5′GGG AAG CTG TGG CGT GAT G 3′ and G3R (antisense) 5′CTG TTG CTG TAG CCG AAT C 3′ were used in a side-by-side amplification with the target gene for TF. PCR profiles consisted of initial denaturation at 95°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 55°C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 60 seconds. The amount of total RNA used for each RT-PCR and the number of cycles were defined inside the linearity range of the reaction. RT-PCR was performed with 80 ng total RNA, and 23 and 32 cycles of amplification were carried out for G3PDH and TF, respectively. Total PCR products (10 μL) were analyzed by ethidium bromide–stained 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis and were visualized by UV transillumination. Expected sizes of the PCR products for TF and G3PDH were 553 and 379 bp, respectively. Because all these primer pairs were designed from different exons, the products with the expected size were amplified from single-strand cDNA but not from contaminating genomic DNA. Bands were quantitated by densitometry using Scion Image software (Scion, Frederick, MD) and were normalized using G3PDH band intensity. RNA from THP-1 stimulated by 10 μg/mL LPS for 2 hours was used as a positive control.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as the mean and standard deviation of the indicated number of experiments. Because the data did not show a Gaussian distribution, differences between groups were evaluated using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test; P < .05 was considered statistically significant. When representative studies were shown, these were indicative of at least 3 equivalent and independent experiments.

Results

Expression of adhesion molecules on EMPs derived from TNF-α–stimulated HUVECs

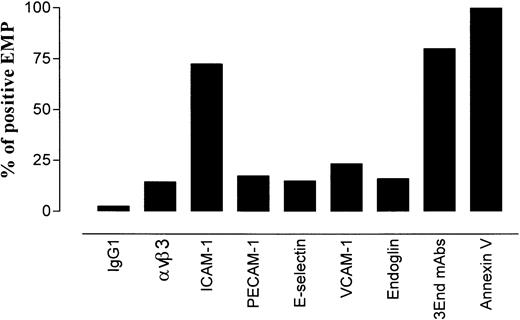

To investigate whether EMPs expressed molecules involved in leukocyte–endothelium adhesion, the presence of constitutive or inducible endothelial adhesion receptors was analyzed on EMP using flow cytometry. For each molecule, results were expressed as the percentage of positively labeled EMPs among the total number of annexin V–positive EMPs. As shown in Figure 1, EMPs expressed adhesion molecules such as PECAM-1, ICAM-1, VCAM-1, E-selectin, and the integrin αvβ3. The expression of these markers was heterogeneous. ICAM-1 was expressed on 72% of the total annexin V–positive EMPs, whereas the other adhesion molecules were detected on 14% to 23% of the annexin V–positive EMPs. The highest number of ICAM-1–positive EMPs could be related to the high expression of ICAM-1 on stimulated endothelial cells.

Distribution of endothelial antigens on EMPs derived from TNF-α–stimulated HUVECs.

EMPs were labeled with mAbs using indirect immunofluorescence or with annexin V–FITC. They were analyzed by flow cytometry as described in “Materials and methods.” For each marker, results are expressed as the percentage of stained EMPs within the total annexin V–positive EMP. Data are representative of 4 independent experiments.

Distribution of endothelial antigens on EMPs derived from TNF-α–stimulated HUVECs.

EMPs were labeled with mAbs using indirect immunofluorescence or with annexin V–FITC. They were analyzed by flow cytometry as described in “Materials and methods.” For each marker, results are expressed as the percentage of stained EMPs within the total annexin V–positive EMP. Data are representative of 4 independent experiments.

We took advantage of this phenotypic characterization to select a marker, or a combination of markers, allowing specific detection of EMP bound to THP-1 cells. The fact that ICAM-1 was expressed by THP-1 cells and EMPs and that only a small proportion of EMPs was detected with the other single mAbs led us to optimize the detection of EMPs by using a combination of 3 mAbs directed against specific endothelial molecules—VCAM-1 and E-selectin as inducible molecules and endoglin as constitutively expressed molecule. As shown in Figures 1 and2, this association, designated as 3End mAbs, allowed optimal detection of EMPs, with 80% of positively stained EMPs compared with 23%, 15%, or 16% of staining with, respectively, anti–VCAM-1, anti–E-selectin, or anti-endoglin used alone. Double labeling for 3End mAbs and annexin V confirmed that more than 90% of endothelial-positive events co-expressed annexin V (data not shown). Consequently, we used this mAb combination to detect EMPs adherent to THP-1 cells in the following experiments.

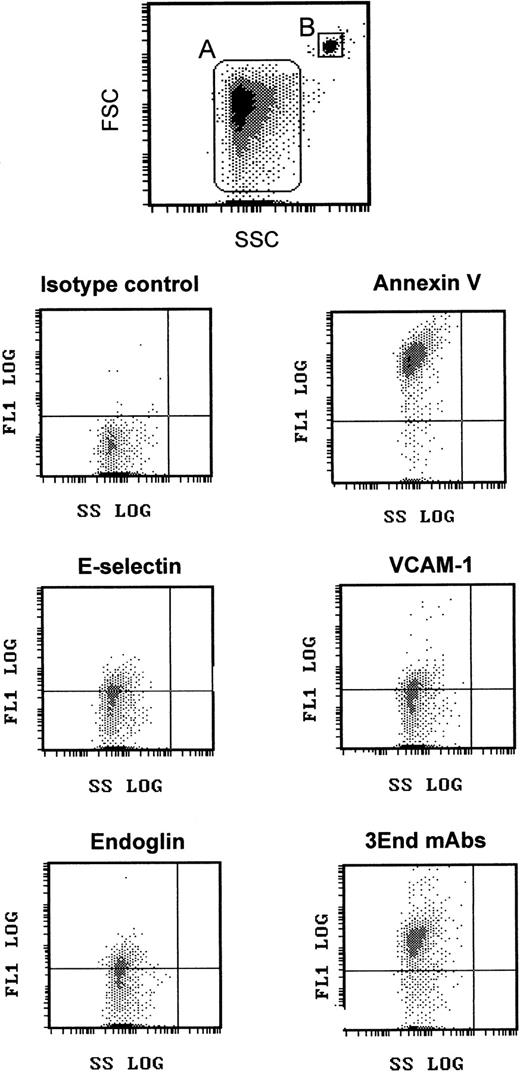

Flow cytometry detection of EMPs.

EMPs were labeled using annexin V–FITC or mAbs directed against endothelial-specific molecules (VCAM-1, endoglin, E-selectin) used alone or in combination (3End mAbs) as described in “Materials and methods.” EMPs (gate A) were discriminated by size on an FSC–SSC cytogram. They were further analyzed for fluorescence associated with irrelevant and specific antibodies. Graphs are representative flow cytometry dot plots depicting fluorescence intensity versus side scatter intensity (FL1–SSC) of EMPs counted using 3-μm latex beads (gate B) as an internal standard. The horizontal gate was drawn at a fluorescence intensity above the background level.

Flow cytometry detection of EMPs.

EMPs were labeled using annexin V–FITC or mAbs directed against endothelial-specific molecules (VCAM-1, endoglin, E-selectin) used alone or in combination (3End mAbs) as described in “Materials and methods.” EMPs (gate A) were discriminated by size on an FSC–SSC cytogram. They were further analyzed for fluorescence associated with irrelevant and specific antibodies. Graphs are representative flow cytometry dot plots depicting fluorescence intensity versus side scatter intensity (FL1–SSC) of EMPs counted using 3-μm latex beads (gate B) as an internal standard. The horizontal gate was drawn at a fluorescence intensity above the background level.

Adhesion of EMPs to THP-1 cells

The presence of adhesion molecules on EMPs derived from TNF-stimulated HUVECs suggests that they could interact with monocytic cells. To investigate this adhesive potential, we incubated THP-1 cells with EMPs at 37°C and performed immunoperoxidase staining using 3End mAbs. Although no staining was detectable in the absence of EMPs, the incubation of THP-1 cells with EMPs for 15 minutes resulted in positive staining compared with isotype control (Figure3). This staining was patchily and heterogeneously distributed on THP-1 cells. The acquisition of endothelial markers by monocytic cells exposed to EMPs suggests that EMPs could adhere to THP-1 cells.

EMP binding to THP-1 cells.

THP-1 cells incubated with EMPs for 15 minutes (C, D) or control THP-1 cells (A, B) were immunostained according to the avidin–biotin–peroxidase procedure and analyzed by microscopy as described in “Materials and methods.” Primary antibody was 3End mAbs (B, D) or isotype-matched control (A, C) used at 50 μg/mL. The ratio of EMP to THP-1 cells was 50:1. Brown coloration on THP-1 cells incubated with EMPs indicated the presence of endothelial antigens. Observations are representative of 4 independent experiments. Original magnification: × 50.

EMP binding to THP-1 cells.

THP-1 cells incubated with EMPs for 15 minutes (C, D) or control THP-1 cells (A, B) were immunostained according to the avidin–biotin–peroxidase procedure and analyzed by microscopy as described in “Materials and methods.” Primary antibody was 3End mAbs (B, D) or isotype-matched control (A, C) used at 50 μg/mL. The ratio of EMP to THP-1 cells was 50:1. Brown coloration on THP-1 cells incubated with EMPs indicated the presence of endothelial antigens. Observations are representative of 4 independent experiments. Original magnification: × 50.

Binding of EMPs to THP-1 cells was confirmed by flow cytometry. THP-1 cells incubated with EMPs for 15 minutes were specifically stained with 3End mAbs, as shown by a right shift in the fluorescence histogram in contrast to the histogram generated by the isotype control (Figure 4A). Moreover, no positive signal was detected on THP-1 cells in the absence of EMPs. Binding of EMPs to THP-1 cells was further analyzed by flow cytometry assays according to duration of incubation, ranging from 5 minutes to 1 hour. Increased fluorescence intensity of THP-1 cells labeled with 3End mAbs was detectable as early as the 5-minute incubation with EMP, using a 50:1 EMP–THP-1 ratio, compared with control THP-1 cells without EMPs. Between 15 minutes and 1 hour, an overlapping of fluorescence histograms was observed showing that maximum EMP binding occurred within 15 minutes (Figure 4B). We also investigated whether EMP binding depended on the quantity of EMP added. THP-1 cells were incubated with various amounts of EMP for 15 minutes. The percentage of THP-1 cells positively stained with 3End mAbs increased with the ratio of EMP–THP-1 cells and reached a plateau at 50 EMPs for 1 THP-1 cell. In this condition, 35% of THP-1 cells were positive for endothelial cell markers (Figure 5).

Kinetics of EMP binding to THP-1 cells.

THP-1 cells were incubated with EMP (50:1 EMP–THP-1 ratio) and were analyzed for the presence of endothelial antigens (VCAM-1, E-selectin, endoglin) by flow cytometry. (A) Representative fluorescence histograms showing 3End mAb-positive staining of THP-1 cells incubated with EMPs for 15 minutes (EMP 3End mAbs) compared with controls. THP-1 cells incubated with control medium stained with isotype control (CM IgG1) or 3End mAbs (CM 3End mAbs), and THP-1 cells incubated with EMP stained with isotype control (EMP IgG1). (B) Representative fluorescence histogram showing staining of THP-1 cells with 3End mAbs after incubation with EMP for 5 minutes, 15 minutes, 30 minutes, and 1 hour (EMP 3End mAbs 5 minutes, 15 minutes, 30 minutes, 1hour) compared with isotype control (EMP IgG1).

Kinetics of EMP binding to THP-1 cells.

THP-1 cells were incubated with EMP (50:1 EMP–THP-1 ratio) and were analyzed for the presence of endothelial antigens (VCAM-1, E-selectin, endoglin) by flow cytometry. (A) Representative fluorescence histograms showing 3End mAb-positive staining of THP-1 cells incubated with EMPs for 15 minutes (EMP 3End mAbs) compared with controls. THP-1 cells incubated with control medium stained with isotype control (CM IgG1) or 3End mAbs (CM 3End mAbs), and THP-1 cells incubated with EMP stained with isotype control (EMP IgG1). (B) Representative fluorescence histogram showing staining of THP-1 cells with 3End mAbs after incubation with EMP for 5 minutes, 15 minutes, 30 minutes, and 1 hour (EMP 3End mAbs 5 minutes, 15 minutes, 30 minutes, 1hour) compared with isotype control (EMP IgG1).

Dose-response curve of EMP binding to THP-1 cells.

THP-1 cells were incubated with increasing numbers of EMPs and were analyzed for the presence of endothelial antigens (VCAM-1, E-selectin, endoglin) by flow cytometry. Graph shows the percentage of FITC-positive cells after immunostaining with 3End mAbs or isotype control. Values are mean ± SD (n = 4).

Dose-response curve of EMP binding to THP-1 cells.

THP-1 cells were incubated with increasing numbers of EMPs and were analyzed for the presence of endothelial antigens (VCAM-1, E-selectin, endoglin) by flow cytometry. Graph shows the percentage of FITC-positive cells after immunostaining with 3End mAbs or isotype control. Values are mean ± SD (n = 4).

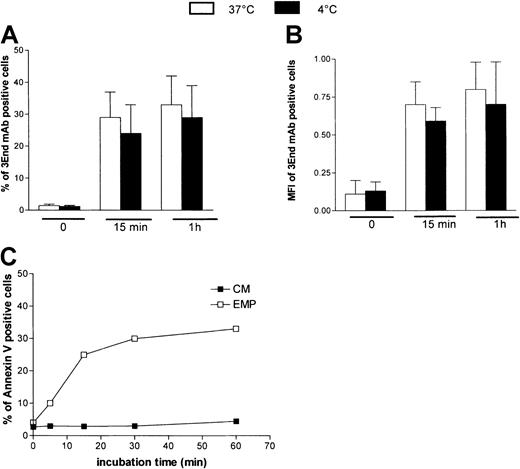

To investigate whether the EMP–THP-1 association resulted from simple adherence or adherence followed by fusion, we analyzed the influence of temperature on this binding. THP-1 cells were incubated with EMPs at 4°C or 37°C and were analyzed after immunoperoxidase staining using 3End mAbs. Microscopic observations demonstrated that endothelial staining was not modified, irrespective of the temperature used for incubation (data not shown). In addition, flow cytometry data showed that the percentage of THP-1 cells positively stained with 3End mAbs was not significantly modified when incubation was performed at ±4°C compared with 37°C (Figure 6A). Mean fluorescence intensity of positive cells, reflecting the amount of EMPs bound to THP-1 cells, was also not modified by low temperatures (Figure6B). To investigate whether phosphatidylserine asymmetry was restored after EMP binding, staining of THP-1 cells with annexin V–FITC was analyzed after incubation with EMPs for various times. Between 5 and 15 minutes, an increase of the level of annexin V staining was observed, reflecting the increase of EMP binding to THP-1 cells. Between 15 and 60 minutes, the amount of positive cells did not decrease (Figure 6C).

Characteristics of EMP binding to THP-1 cells.

Temperature dependency of EMP binding to THP-1 cells. THP-1 cells were incubated with EMP at 4°C or 37°C for various times and were analyzed for the presence of endothelial antigens (VCAM-1, E-selectin, endoglin) by flow cytometry. Graph shows the percentage (A) and mean fluorescence intensity (B) of 3End mAb-positive cells. Values are mean ± SD (n = 3). Phosphatidylserine expression on THP-1 cells after EMP binding. THP-1 cells were incubated with EMP or control medium (CM) for 5 minutes to 60 minutes at 37°C and were stained with annexin V–FITC. Representative flow cytometry data of 3 independent experiments are illustrated (C).

Characteristics of EMP binding to THP-1 cells.

Temperature dependency of EMP binding to THP-1 cells. THP-1 cells were incubated with EMP at 4°C or 37°C for various times and were analyzed for the presence of endothelial antigens (VCAM-1, E-selectin, endoglin) by flow cytometry. Graph shows the percentage (A) and mean fluorescence intensity (B) of 3End mAb-positive cells. Values are mean ± SD (n = 3). Phosphatidylserine expression on THP-1 cells after EMP binding. THP-1 cells were incubated with EMP or control medium (CM) for 5 minutes to 60 minutes at 37°C and were stained with annexin V–FITC. Representative flow cytometry data of 3 independent experiments are illustrated (C).

Taken together, these data indicated that EMP bound to THP-1 cells. This interaction occurred rapidly, in a dose-dependent manner. EMP binding was not affected by low temperature and was not followed by restoration of phosphatidylserine asymmetry.

Effect of EMP binding on the procoagulant activity of THP-1 cells

To investigate whether the binding of EMP may influence THP-1 cell functional properties, we analyzed the procoagulant activity of THP-1 cells incubated with EMPs. A 15-minute exposure of THP-1 cells to EMPs resulted in a moderate but significant increase of their procoagulant activity compared to control THP-1 cells (respectively, 124 ± 30 au vs 49 ± 29 au; P = .04) (Figure7). After a 4-hour incubation, the procoagulant activity of THP-1 cells was strongly increased (700 ± 136 au vs 60 ± 24 au for control THP-1 cells;P = .0022). Procoagulant activity induced by EMPs was lower than that induced by LPS used as a positive control (1823 ± 429 au; P = .02).

Induction of THP-1 cell procoagulant activity by EMP binding.

THP-1 cells were incubated with EMP (black bars), control medium (white bars), or LPS (gray bars) for 15 minutes and 4 hours and then were prepared for assessment of procoagulant activity using clotting assay, as noted in “Materials and methods.” Procoagulant activity was determined by reference to a thromboplastin standard curve and was expressed as arbitrary units. Values are mean ± SD (n = 7). *P < .05; **P < .01.

Induction of THP-1 cell procoagulant activity by EMP binding.

THP-1 cells were incubated with EMP (black bars), control medium (white bars), or LPS (gray bars) for 15 minutes and 4 hours and then were prepared for assessment of procoagulant activity using clotting assay, as noted in “Materials and methods.” Procoagulant activity was determined by reference to a thromboplastin standard curve and was expressed as arbitrary units. Values are mean ± SD (n = 7). *P < .05; **P < .01.

These experiments were then reproduced using a plasma deficient in factor VII, the major substrate of TF. Under these conditions, no significant difference was observed between the clotting time measured in the presence of control THP-1 cells or EMP-stimulated THP-1 cells (data not shown). Taken together, these results show that, in response to EMPs, monocytic cells exhibited a procoagulant activity that could be attributable to TF pathway induction.

Effect of EMP binding on TF protein level in THP-1 cells

To analyze the role of TF expression in the procoagulant response of THP-1 cells, we determined TF antigen content in THP-1 cells on exposure to EMPs for various times. In cellular extract of resting THP-1 cells, TF antigen content was 34 ± 21 pg/mL. It significantly increased after 1- and 2-hour incubations with EMPs (71.7 ± 24.5,P = .017, and 117.8 ± 31, P = .005, respectively) and reached a peak at 4 hours (198.8 ± 30.4;P = .004). Conversely, TF antigen content in THP-1 cells was unmodified after 15-minute or 4-hour incubation with EMP-free supernatant (Figure 8). As a positive control, monocyte stimulation by LPS produced a significant increase in TF antigen levels (251 ± 80 pg/mL; P = .008).

Effect of EMPs on TF protein level in THP-1 cells.

THP-1 cells were incubated with control medium (CM), EMP, or EMP-free supernatant (S) for 15 minutes to 4 hours, and TF antigen level in cell lysates was determined using ELISA. At 4 hours, LPS stimulation was used as positive control. The quantity of antigen was expressed in pg/mL cell lysate. Values are mean ± SD (n = 4). *P < .05; **P < .01.

Effect of EMPs on TF protein level in THP-1 cells.

THP-1 cells were incubated with control medium (CM), EMP, or EMP-free supernatant (S) for 15 minutes to 4 hours, and TF antigen level in cell lysates was determined using ELISA. At 4 hours, LPS stimulation was used as positive control. The quantity of antigen was expressed in pg/mL cell lysate. Values are mean ± SD (n = 4). *P < .05; **P < .01.

Effect of EMPs on TF mRNA expression by THP-1 cells

To investigate whether the increase in TF antigen resulted from a net synthesis by THP-1 cells, TF gene transcription in THP-1 cells was investigated by RT-PCR after 30-minute to 3-hour incubations with EMPs. As shown in Figure 9, TF mRNA was weakly expressed in control THP-1 cells, whereas it dramatically increased in THP-1 cells incubated with EMPs for 1 hour and 2 hours. The intensity of the signal returned to baseline after 3 hours of incubation. TF mRNA was undetectable in EMP suspension (data not shown), indicating that the increased signal observed by RT-PCR was related to TF synthesis by THP-1 cells. In control experiments, THP-1 cells incubated with EMP-free supernatant displayed levels of TF mRNA similar to those of resting cells, whatever the incubation time, excluding a soluble factor as a potential trigger of TF expression.

Effect of EMPs on TF gene transcription in THP-1 cells.

THP-1 cells were incubated with EMPs or EMP free-supernatant (S) for 30 minutes to 3 hours, and TF mRNA expression in THP-1 cells was assessed using RT-PCR. THP-1 cells stimulated with LPS for 2 hours were used as positive controls. (A) Representative ethidium bromide visualization of PCR-amplified products of TF and G3PDH mRNA after agarose gel electrophoresis. Band intensity was measured by densitometry. (B) Relative values of TF mRNA normalized to G3PDH mRNA. Values are mean ± SD (n = 5). *P < .05; **P < .01.

Effect of EMPs on TF gene transcription in THP-1 cells.

THP-1 cells were incubated with EMPs or EMP free-supernatant (S) for 30 minutes to 3 hours, and TF mRNA expression in THP-1 cells was assessed using RT-PCR. THP-1 cells stimulated with LPS for 2 hours were used as positive controls. (A) Representative ethidium bromide visualization of PCR-amplified products of TF and G3PDH mRNA after agarose gel electrophoresis. Band intensity was measured by densitometry. (B) Relative values of TF mRNA normalized to G3PDH mRNA. Values are mean ± SD (n = 5). *P < .05; **P < .01.

Role of adhesion molecules in THP-1 cell procoagulant activity induced by EMPs

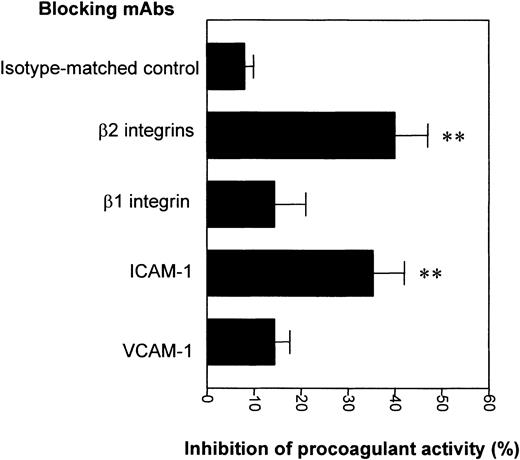

The integrin family of adhesive molecules has been involved in monocyte TF expression. Because EMPs express adhesive receptors, such as VCAM-1 and ICAM-1, that mediate monocyte adhesion, we analyzed their potential involvement in the EMP-induced procoagulant activity of THP-1 cells. For this purpose, blocking antibodies against VCAM-1, ICAM-1, or their monocytic ligands were added with EMPs to THP-1 cells. Blocking antibodies against β2 integrins (mixed CD11a, CD11b, and CD11c) significantly inhibited the procoagulant activity of THP-1 cells by 40% ± 12% compared with the isotype control (8% ± 6%;P = .007) (Figure 10). This procoagulant activity was also reduced by 35% ± 11% (P = .008) in the presence of blocking antibodies directed against ICAM-1. The inhibitory effects of blocking antibodies against β2 integrins and ICAM-1 were not significantly additive (data not shown). Antibodies directed against the β1 integrin VLA-4 or against VCAM-1 did not significantly decrease EMP-induced procoagulant activity. These results indicated that the induction of THP-1 cell procoagulant activity by EMPs involved the ICAM-1–β2 integrin interaction.

Role of adhesion molecules in THP-1 cell procoagulant activity induced by EMPs.

THP-1 cells were incubated with EMPs for 4 hours in the presence of isotype control or blocking antibodies directed to adhesion molecules. Then THP-1 cell procoagulant activity was determined by measuring the clotting time after addition to normal plasma and recalcification. Results are expressed as the percentage of inhibition of EMP-induced monocytic procoagulant activity. Data are mean ± SD of 5 separate experiments. **P < .01.

Role of adhesion molecules in THP-1 cell procoagulant activity induced by EMPs.

THP-1 cells were incubated with EMPs for 4 hours in the presence of isotype control or blocking antibodies directed to adhesion molecules. Then THP-1 cell procoagulant activity was determined by measuring the clotting time after addition to normal plasma and recalcification. Results are expressed as the percentage of inhibition of EMP-induced monocytic procoagulant activity. Data are mean ± SD of 5 separate experiments. **P < .01.

Effect of EMP on the procoagulant activity of peripheral blood monocytes

To investigate whether the response induced by EMPs in the THP-1 cell line was representative of peripheral blood monocytes, the procoagulant activity of human monocytes exposed to EMP was analyzed. A 15-minute exposure of monocytes to EMPs (50:1 ratio, EMP–THP-1) induced a moderate but significant increase in procoagulant activity compared with control cells (65 ± 32 au vs 19 ± 17 au, respectively; P = .044) (Table1). After a 4-hour incubation, the procoagulant activity was strongly increased (173 ± 84 au vs 21 ± 17 au for control monocytes; P = .008). EMPs induced a procoagulant activity lower than that induced by LPS used as positive control, and no significant effect was observed when monocytes were stimulated with EMP-free supernatant. In addition, as observed for THP-1 cells, the clotting time of factor VII–deficient plasma was not significantly reduced in the presence of EMP-stimulated monocytes compared with resting monocytes (data not shown), showing that this activity is TF-dependent. Taken together, these results indicated that EMP induced a procoagulant activity in purified human monocytes in a way similar to that observed in the THP-1 cell line.

Procoagulant activity of peripheral blood monocytes

| . | Monocyte procoagulant activity (au) . | |

|---|---|---|

| 15-min incubation . | 4-h incubation . | |

| Control medium | 19.5 ± 17.5 | 21.9 ± 17 |

| EMP | 65.6 ± 32.2* | 173 ± 84† |

| EMP-free supernatant | 20 ± 14 | 23 ± 9 |

| LPS (1 μg/mL) | 28 ± 12 | 821 ± 97† |

| . | Monocyte procoagulant activity (au) . | |

|---|---|---|

| 15-min incubation . | 4-h incubation . | |

| Control medium | 19.5 ± 17.5 | 21.9 ± 17 |

| EMP | 65.6 ± 32.2* | 173 ± 84† |

| EMP-free supernatant | 20 ± 14 | 23 ± 9 |

| LPS (1 μg/mL) | 28 ± 12 | 821 ± 97† |

Peripheral blood monocytes from healthy volunteers were incubated with EMP, control medium, LPS (1 μg/mL), or supernatant free of EMP for 15 minutes and 4 hours and then were prepared for assessment of procoagulant activity using clotting assay. Procoagulant activity was determined by reference to a thromboplastin standard curve and was expressed as arbitrary units. Data are mean ± SD (n = 4).

P < .05 compared with control medium;

P < .01 compared with control medium.

Discussion

In the present study, we showed that EMPs derived from TNF-α–stimulated endothelial cells bind to THP-1 cells and induce a TF-dependent procoagulant activity in these cells; this effect involves the interaction between ICAM-1 on EMP and β2 integrin on monocytic cells.

Phenotypic analysis of MPs shed by TNF-α–stimulated HUVECs showed that EMPs expressed receptors belonging to immunoglobulin superfamily adhesion molecules or to the integrin family. The fact that the EMP phenotype was similar to that displayed by activated cells suggested that EMP may represent a “circulating endothelial compartment” bearing the capacity to develop adhesive interactions with leukocytes. The positive labeling of monocytic cells for VCAM-1, E-selectin, and endoglin, evidenced by immunoperoxidase labeling and flow cytometry, clearly indicated that EMP binds to THP-1 cells. This binding occurs rapidly, in a dose-dependent manner. The mechanisms of EMP–THP-1 association remain to be elucidated. The fact that EMP binding was not temperature-dependent and was not followed by the restoration of phosphatidylserine asymmetry suggests that EMP–THP-1 association is a receptor-mediated binding rather than a membrane fusion. Moreover, the patchy distribution of endothelial antigens on THP-1 cells indicates that the protein acquisition is not attributable to the fusion of vesicles to plasma membrane of recipient cells, as already observed during the interaction between lymphocytic MPs and epithelial cells.28 In accordance with a mechanism of receptor-mediated interaction, the binding of platelet MPs to leukocytes has been shown to be partially inhibited by anti–P-selectin or anti-sialyl Lewis X blocking antibodies.29,30 However, others models have documented the membrane incorporation of vesicles derived from peripheral blood mononuclear cells able to transfer the chemokine receptor, CCR5, to endothelial cells.31 More recently, it has been shown that TF is transferred from monocyte membrane particles to platelets during thrombus formation.32

Cell–cell interactions are known to represent an important mechanism for TF regulation in monocytic cells, as shown by coculture of monocytes with stimulated endothelial cells.33,34 In a similar way, our results demonstrated that the procoagulant properties of THP-1 cells were amplified by contact with EMPs. Two different processes may be involved in this increased procoagulant activity. EMPs are known to bear intrinsic procoagulant potential supported by phosphatidylserine and TF present at their surfaces. Therefore, the increase in procoagulant activity observed after a 15-minute incubation with EMPs could result from the adhesion and transfer of EMP procoagulant activity on THP-1 cells. Moreover, the strong enhancement of THP-1 procoagulant activity after a 4-hour incubation suggests that THP-1 procoagulant pathways were induced by EMPs. In agreement with this hypothesis, increased TF antigen and mRNA levels were observed in THP-1 cells exposed for different times to EMP. These effects were not caused by the presence of residual TNF-α or others soluble mediators in the EMP suspension because these were not observed when THP-1 cells were incubated with an EMP-depleted supernatant. In addition, no TF mRNA was recovered by RT-PCR in EMPs, ruling out the possibility of a TF mRNA transfer from EMP to THP-1 cells during coincubation. Therefore, we can assume that EMPs are able to modulate TF gene expression in monocytic cells. TF induction on stimulation by MP is not restricted to monocytic cells. A similar paradigm has been proposed for leukocyte MPs able to mediate a procoagulant response in endothelial cells by increasing the expression of TF mRNA.35 However, this effect appears to be dependent on the cellular origin of MPs. In fact, Mesri and Altieri36 showed that platelet-derived MPs failed to affect TF expression in endothelial cells.

At present, the molecular basis of THP-1 stimulation by endothelium-derived MPs remains to be elucidated. A hypothesis for TF synthesis involves interactions between cellular adhesion molecules. Studies have shown that the outside-in signaling pathway triggered by β2 integrins LFA-1 (CD11a) and Mac-1 (CD11b) or β1 integrin VLA-4 on THP-1 cells is sufficient to generate monocytic tissue factor expression.37,38 Consistent with the major contribution of integrin-mediated signaling events, we observed that in THP-1 cells, the procoagulant activity induced by EMPs was significantly reduced by blocking THP-1 surface integrins or their MP counterreceptors. These data indicate that the interaction between monocytic β2 integrins and ICAM-1 at the EMP surface participate in stimulatory signals following EMP–THP-1 adhesion. However, the fact that this inhibitory effect was partial suggests additional mechanisms of monocyte activation. Transcellular delivery of arachidonic acid has been proposed as an alternative mechanism of cell activation by platelet MPs.39 Moreover, MPs supply phospholipid substrates for the generation of potent inflammatory mediators, such as lysophosphatidic acid.40 Finally, TF induction on monocytes exposed to EMPs may result from the autocrine secretion of cytokines. This hypothesis is supported by recent data demonstrating enhanced cytokine secretion by endothelial cells or monocytes on stimulation by platelet MPs.30-36

The pathophysiological relevance of this mechanism in vivo is still unknown. We have shown that induction of a TF-dependent procoagulant activity was also observed during interaction of EMPs with peripheral blood monocytes. Thus, EMPs delivered through the blood circulation disseminate prothrombotic potential through their capacity to adhere to circulating cells and to amplify monocytic procoagulant properties. This phenomenon could be implicated in prothrombotic situations associating increased levels of EMPs and monocyte-associated TF such as meningococcal sepsis,41 thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura,42 antiphospholipid syndrome,9 or rupture of the atherosclerotic plaque.21

In summary, we propose that EMP generation represents an alternative mechanism of endothelium–leukocyte cross-talk through sequential steps of adhesion to circulating cells and transduction of activating signals. Together with locally released cytokines and leukocyte–endothelium intercellular signaling, EMPs may act as a complementary paracrine activation pathway controlling the procoagulant properties of circulating cells.

We thank P. Stellman and R. Giordana for cell cultures, M. Revest-Jamond and A. Boyer for technical assistance, and Beckman Coulter Immunotech and Biocytex Company for providing antibodies. We also thank D. Arnoux for reviewing the article.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Françoise Dignat-George, INSERM EMI 00-19, UFR de Pharmacie, 27 Blvd Jean Moulin, 13385 Marseille Cedex 5, France; e-mail: dignat@pharmacie.univ-mrs.fr.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal