Signal transducers and activators of transcription (Stat) proteins play important roles in the regulation of hematopoiesis as downstream molecules of cytokine signal transduction. It was previously demonstrated that erythropoietin (EPO), a major regulator of erythropoiesis, activates 3 different Stat members, Stat1, Stat3, and Stat5, in a human EPO-dependent cell line, UT-7/EPO. To clarify the mechanism by which EPO activates Stat1 and Stat3 via the EPO receptor (EPOR), a series of chimeric receptors was constructed bearing the extracellular domain of the granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor linked to the transmembrane domain of EPOR and the full length or several mutants of the cytoplasmic domain of EPOR, and these chimeric receptor complementary DNAs were introduced into UT-7/EPO cells. Tyr432 on human EPOR was important for activation of Stat1 and Stat3 and c-myc gene induction. In addition, Jak2 and Fes tyrosine kinases were involved in EPO-induced activation of Stat1 and Stat3. These results indicate that Stat1 and Stat3 are activated by EPO via distinct mechanisms from Stat5.

Introduction

Erythropoietin (EPO) is the major regulator of the proliferation and differentiation of erythroid progenitors.1 The binding of EPO to its specific receptor on the cell surface induces the tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of many proteins, including Jak2 tyrosine kinase, signal transducers and activators of transcription (Stat) proteins, the p85 subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, mitogen-activated protein kinases, and phospholipase C-γ1.2

Stat family members lie downstream of numerous cytokine receptors and regulate cell growth, survival, and differentiation via activation of target genes as transcription factors.3 Among Stat members, Stat5 is an EPO-responsive protein and necessary for erythroid differentiation in a murine leukemia cell line.4,5 It was reported that a dominant-negative Stat5 reduced the erythroid colony formation from CFU-E (erythroid colony-forming unit) in fetal liver cells.6 Furthermore, Stat5a and Stat5b double knock-out (Stat5a−/−/5b−/−) reduced Bcl-XL expression and led to modest fetal anemia through increased apoptosis of erythroid progenitor cells.7 Thus, Stat5 proteins appear to play important roles at least in erythropoiesis. However, surprisingly, the adult mice with the Stat5a−/−/5b−/−phenotype had normal hematocrit levels and normal numbers of erythroid progenitor cells7,8 Therefore, the Stat5 system may be important in times of erythropoietic expansion (fetal life, response to hydrazine-induced hemolysis, etc), but it's not so critical and can be compensated for in steady state erythropoiesis. Alternatively, a compensatory mechanism may overcome the deficiency of Stat5 and allow the survival of knock out mice. One of the putative compensatory mechanisms may be the activation of Stat1 and Stat3 induced by EPO.7 Several lines of evidence support this notion. First, the expression of Stat1 protein was enhanced in Stat5a−/−/5b−/− mice. Second, both Stat1 and Stat3 can bind the promoter of the Bcl-XL gene and up-regulate the gene expression.9,10 Third, several groups reported that Stat1 and Stat3 were activated by EPO in murine erythroleukemia cell lines.11,12 We also found that EPO rapidly and strongly activates Stat1 and Stat3 by supershift analysis in EPO-responsive human leukemia cell lines UT-7/EPO and F36-E.13 Recently, it was reported that erythroid burst-forming units from Stat1 knock-out mice showed a weaker response to EPO than those from normal mice.14 Taken together, these results strongly suggested that Stat1 and Stat3 play an important role in erythropoiesis as downstream molecules of EPO receptor (EPOR), although the mechanism by which EPO activates Stat1 and Stat3 through EPOR is still open to question.

In this study, we focused on determining the EPOR region required for activation of Stat1 and Stat3 and on identifying the tyrosine kinases involved in the activation. To this end, we generated a series of chimeric receptors composed of the extracellular domain of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor (G-CSFR) and various lengths of the internal region of EPOR, and we transfected them into UT-7/EPO that does not express endogenous G-CSFR.15 We show here that Tyr432 on human EPOR is critical for EPO-induced activation of Stat1 and Stat3 and that Jak2 and c-Fes tyrosine kinases are directly involved in the activation of these Stat proteins.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

UT-7/EPO cells were maintained in liquid culture with Iscoves modified Dulbecco medium (Gibco Laboratories, Grand Island, NY) containing 10% fetal calf serum (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT) and 1 U/mL EPO.15 The 293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Sigma, St Louis, MO) with 10% fetal calf serum.

Hematopoietic growth factors and reagents

Recombinant human EPO and recombinant human G-CSF were gifts from the Life Science Research Institute of the Snow Brand Milk Company (Tochigi, Japan). Neomycin (G418) was purchased from Gibco BRL Life Technologies (Gaithersburg, MD). Antisera against v-Fes was purchased from Calbiochem (Cambridge, MA). Antisera against Jak2 and phosphoJak2 (pY1007/1008) were purchased from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY) and BioSource International (Camarillo, CA), respectively. AG490 was purchased from Sigma. Anti–G-CSFR antibody was purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). Antiphosphotyrosine antibody (PY20) was purchased from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY). pRC/CMV-FES-KE was kindly provided by Dr Greer (Queen's University, Ontario, Canada). Antisera against Lyn-A and expression vector containing lyn complementary DNA (cDNA) were gifts from Dr Mano (Jichi Medical School, Tochigi, Japan).

Preparation of nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts and electromobility shift assay

After stimulation with EPO, cells were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline containing 2 mM Na3VO4, resuspended in a hypertonic buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, 15 μg/mL aprotinin, 3 μg/mL leupeptin, 3 μg/mL pepstatin, and 2 mM Na3VO4, with 0.2% Nonidet P-40) and homogenized. After centrifugation at 1000g for 5 minutes, the supernatant was separated from the nuclear pellet and then centrifuged at 14 000g for 20 minutes at 4°C. After the debris was removed, the supernatants were collected as cytoplasmic extracts. The nuclear pellets were resuspended in hypotonic buffer with 300 mM NaCl, then debris was removed by centrifugation (14 000g for 20 minutes) and the supernatants were collected as nuclear extracts. Electromobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed as described previously.13

Preparation of cell lysates, immunoprecipitation, and Western blotting

UT-7/EPO cells were deprived of any growth factors for 24 hours. After stimulation with cytokines at 37°C for 10 minutes, cell lysates were prepared as described previously.13 The supernatants were immunoprecipitated with anti–v-Fes antibody. Immunoprecipitates were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and then electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Bio Rad, Richmond, CA). The blots were incubated with the appropriate concentration of primary antibodies, including antiphosphotyrosine monoclonal antibody PY20 and visualized by using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (ECL Western Blotting Analysis System; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, England). In some experiments, total cell lysates were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. The blots were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin for 1 hour, then incubated with antiphosphoJak2 polyclonal antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. After a wash with phosphate-buffered saline containing Tween 20 (1:2000), the blots were probed with a 1:10 000 dilution of goat antirabbit horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies for 20 minutes at room temperature. After a second wash, the blots were incubated with an enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (ECL plus Western Blotting Analysis System; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and were exposed to Hyperfilm ECL to visualize immunoreactive bands. The blots were stripped with 62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 100 μM β-mercaptoethanol at 50°C for 30 minutes, washed, blocked, and reprobed.

Construction of G-CSFR/EPOR chimeric receptors

The plasmids bearing the genes that encode the extracellular domain of G-CSFR were described before.16 Various lengths of the intracellular domain of human EPOR cDNA were generated by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) by using theEcoRI site-containing sense primer, 5′-CGGAATTCGACCCCCTCATCCTGAC-3′ and the SpeI site-containing antisense primer, 5′-GACTAGTCCTACTGATCATCTGCAGCCT-3′ for GEY8, 5′-GACTAGTCCTAGGGGCCATCGGATAAGCC-3′ for GEY5, 5′-GACTAGTCCTACAGGTACTTTAGGTGGGGTGG-3′ for GEY3, or 5′-GACTAGTCCTACTCCACTGCCTGCATCGT-3′ for GEY0 (underline indicates restriction sites). The amplified fragments were subcloned into TA-cloning vector PCRII. Each plasmid was sequenced to confirm PCR fidelity. Then cDNA fragments encoding the EPOR cytoplasmic portion were subcloned into the pBluescript containing the extracellular domain of G-CSFR and fusion genes were generated. The cDNA encoding chimeric receptors was then subcloned into mammalian expression vector pcDNA 3.1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing the neomycin-resistance gene.

Site-directed mutagenesis

The GEY4F or GEY5F mutant construct was made by site-directed mutagenesis (Quick change mutagenesis kit; Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) by using primer pairs, 5′-CCCCACCTAAAGTACCTGTTCCTTGTGGTATCTGAC-3′ for Y4F and 5′-GGCATCTCAACTGACTTCAGCTCAGGGGACTCC-3′ for Y5F. Each plasmid was sequenced to confirm PCR fidelity.

Generation of stable transfectants

UT-7/EPO cells were transfected with mammalian expression vector (pcDNA3.1) alone or with pcDNA3.1 containing a series of G-CSFR–EPOR chimeric receptor cDNAs by the lipofection method (Promega, Madison, WI). We selected 3 independent clones resistant to neomycin (1.0 mg/mL). We also introduced the kinase-inactive form of c-fescDNA into UT-7/EPO cells by using the expression vector pRC/CMV.

Analysis of G-CSFR expression by flow cytometry

Cell-surface antigens were detected by immunofluorescence staining with antibodies against G-CSFR. In brief, UT-7/EPO cells or transfectants expressing chimeric receptors were incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C with the appropriately diluted antibody. Then the cells were incubated with fluorescein-labeled second antibody for 30 minutes at 4°C. After a second washing, signals were analyzed by using a Becton Dickinson Flow Cytometer (FACScan; Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA), using 10 000 cells for each sample.

Colorimetric MTT assay for cell proliferation

Cell growth was examined by a colorimetric assay according to Mosmann17 with some modifications.

Luciferase assay

UT-7/EPO cells or UT-7/EPO–derived transfectants were starved for 12 hours and then transfected with luciferase reporter plasmid containing the human c-myc gene and its deletion mutants, named −2039/+532myc, −2039/+532mE2Fmyc, −101/+532myc, and −101/+532mE2Fmyc,18 by lipofection with the internal control plasmid pRL-TKLUC (Promega). After an additional 12 hours' incubation, the cells were treated with or without EPO (10 U/mL). Six hours later, the cells were harvested for Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay (Promega). Test values were corrected for the luciferase activity value of the internal control plasmid, pRL-CMV. In some experiments, expression vector pCAGGS-neo, pCAGGS-Stat1F, or pCAGGS-Stat3F was cotransfected.

RNA extraction and Northern blotting

Total RNA was isolated from cells according to the method as previously described.13 RNA was resolved by electrophoresis on agarose formaldehyde gels, transferred to nylon membranes (Hybond-N+, Amersham) in 10× standard sodium citrate, and hybridized to human cDNA fragments for c-myc (Takara Shuzo, Shiga, Japan) labeled with AlkPhos Direct kit (Amersham). Then the hybridized bands were visualized with Geneimages kit (Amersham).

Results

Generation of the transfectants expressing G-CSFR–EPOR chimeric receptors

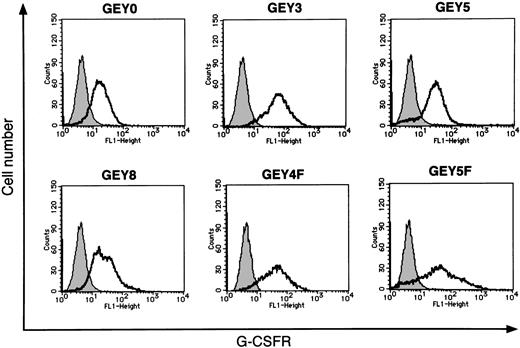

Human EPOR has 8 tyrosine residues in its cytoplasmic domain. Among them, both the first and the second tyrosine residues (Tyr344 and Tyr402) are required for Stat5 activation.19 20 To determine the region of EPOR required for Stat1 and Stat3 activation, we constructed a series of chimeric receptors bearing the extracellular domain of human G-CSFR linked to the transmembrane domain of human EPOR and the full-length or several deletion mutants of the cytoplasmic domain of human EPOR (Figure 1). We introduced these chimeric receptors into UT-7/EPO and established 3 independent clones expressing each chimeric receptor. The expression levels of chimeric receptors were determined by flow cytometry using anti–G-CSFR antibody (Figure 2) and confirmed by Western blot analysis (data not shown).

Schematic structures of G-CSFR–EPOR chimeric receptors.

Schematic structures of G-CSFR–EPOR chimeric receptors are shown. TM, transmembrane domain; Y, tyrosine; F, phenylalanine.

Schematic structures of G-CSFR–EPOR chimeric receptors.

Schematic structures of G-CSFR–EPOR chimeric receptors are shown. TM, transmembrane domain; Y, tyrosine; F, phenylalanine.

Flow cytometric analysis of expression of chimeric receptors on the cell surface of UT-7/EPO–derived transfectants.

Parental UT-7/EPO cells and each transfectant were incubated with mouse antihuman G-CSFR antibodies. Then the cells were stained with fluorescein-conjugated rabbit antimouse antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry. The thin line in each panel indicates the expression profile of parental UT-7/EPO cells as a negative control. The thick line in each panel indicates the expression profile of each transfectant.

Flow cytometric analysis of expression of chimeric receptors on the cell surface of UT-7/EPO–derived transfectants.

Parental UT-7/EPO cells and each transfectant were incubated with mouse antihuman G-CSFR antibodies. Then the cells were stained with fluorescein-conjugated rabbit antimouse antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry. The thin line in each panel indicates the expression profile of parental UT-7/EPO cells as a negative control. The thick line in each panel indicates the expression profile of each transfectant.

Stat activation through chimeric receptors

To confirm the potential of the mutated receptors to activate Stat proteins, the chimeric receptor-expressing cells were stimulated with EPO (10 U/mL), G-CSF (250 ng/mL), or medium alone after 24 hours' starvation of cytokine. Nuclear extracts were then prepared for EMSA. We used SIE and β-CAP oligonucleotides for detection of activated Stat1 and Stat3, and activated Stat5, respectively. We identified A, B, and C in Figure 3 as a homodimer of Stat3, a heterodimer of Stat1 and Stat3, and a homodimer of Stat1, respectively13 (data not shown). In UT-7/EPO cells expressing chimeric receptors containing the full-length cytoplasmic domain of EPOR (UT-7/EPO/GEY8), G-CSF activated Stat1, Stat3, and Stat5 (Figure 3A,B lanes 4-6). These 3 Stat proteins were also activated in UT-7/EPO/GEY5 after G-CSF stimulation (Figure 3A,B lanes 7-9). However, G-CSF activated only Stat5 in UT-7/EPO/GEY3 (Figure 3A,B lanes 10-12). None of the Stat proteins were activated in UT-7/EPO/GEY0 after G-CSF stimulation (Figure 3A,B lanes 13-15). In contrast to G-CSF, EPO activated all 3 Stat proteins in each clone, indicating that the differences in the Stat activation pattern did not result from loss of the machinery for Stat activation in the clones used in these experiments. Collectively, these results clearly indicated that Stat1 and Stat3 were activated through a specific region of EPOR distinct from that required for Stat5 activation.

Activation of Stat proteins by G-CSF through the chimeric receptors.

Parental UT-7/EPO cells and each chimeric clone were starved for 24 hours. Then the cells were stimulated with medium alone (−), 250 ng/mL G-CSF (G), or 10 U/mL EPO (E) for 15 minutes, and nuclear proteins were extracted for EMSA. SIE (A) and β-CAP (B) probes were used for detection of Stat1 and Stat3 DNA-binding activities, and Stat5 DNA-binding activity, respectively. Arrows A, B, and C indicate a homodimer of Stat3, a heterodimer of Stat1α and Stat3, and a homodimer of Stat1α, respectively.13 Arrow D indicates the Stat5 homodimer.13

Activation of Stat proteins by G-CSF through the chimeric receptors.

Parental UT-7/EPO cells and each chimeric clone were starved for 24 hours. Then the cells were stimulated with medium alone (−), 250 ng/mL G-CSF (G), or 10 U/mL EPO (E) for 15 minutes, and nuclear proteins were extracted for EMSA. SIE (A) and β-CAP (B) probes were used for detection of Stat1 and Stat3 DNA-binding activities, and Stat5 DNA-binding activity, respectively. Arrows A, B, and C indicate a homodimer of Stat3, a heterodimer of Stat1α and Stat3, and a homodimer of Stat1α, respectively.13 Arrow D indicates the Stat5 homodimer.13

Substitution of Y4 decreases Stat1 and Stat3 activation

Because G-CSF induced Stat1 and Stat3 activation in UT-7/EPO/GEY5 but not in UT-7/EPO/GEY3 cells, we hypothesized that the region containing Y4 (Tyr432) and/or Y5 (Tyr444) is crucial for activation of Stat1 and Stat3 proteins. To test this notion, we generated a chimeric receptor with the mutation at the Y4 or Y5 tyrosine residue as illustrated in Figure 1. Each tyrosine residue was replaced by phenylalanine (GEY4F and GEY5F). These mutated cDNAs were introduced into UT-7/EPO cells, and the expression level of the receptors was determined by flow cytometry by using anti–G-CSFR antibody (Figure 2). Each transfectant was stimulated with G-CSF, and the activation of Stat proteins was analyzed by EMSA. As shown in Figure 3A,B, G-CSF activated Stat5 but not Stat1 or Stat3 in UT-7/EPO/GEY4F cells. By contrast, G-CSF induced the activation of Stat1, Stat3, and Stat5 in UT-7/EPO/GEY5F cells (Figure 3A,B). These results indicate that the Y4 tyrosine residue of the cytoplasmic domain of EPOR is essential for Stat1 and Stat3 activation.

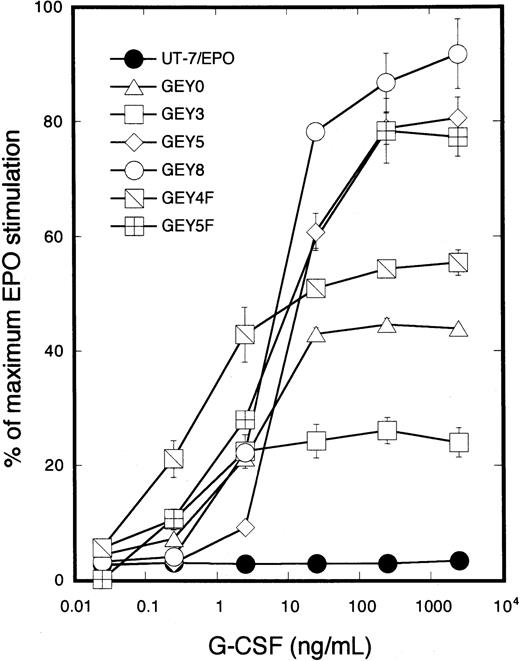

Proliferative response to G-CSF in the transfectant cells expressing chimeric receptors

To determine whether mutant chimeric receptors can transduce signals for proliferation into the nucleus in response to G-CSF, transfectant cells were cultured with increasing concentrations of G-CSF (0.025 to 2500 ng/mL). MTT assay revealed that the cells expressing GEY8 or GEY5 chimeric receptors exhibited the same proliferative response to G-CSF as to EPO. In contrast, the proliferative response to G-CSF decreased in UT-7/EPO/GEY3, UT-7/EPO/GEY0, and UT-7/EPO/GEY4F cells, showing impaired Stat1 and Stat3 activation after G-CSF treatment (Figure4). These results support our previous finding that activation of Stat1 and Stat3 was correlated with EPO-induced cellular proliferation of UT-7/EPO cells.13

Growth curve of the transfectant cells expressing chimeric receptors in response to G-CSF.

Parental UT-7/EPO cells or the transfectants expressing GEY0, GEY3, GEY5, GEY8, GEY4F, or GEY5F were cultured with various concentrations of G-CSF (0.25 to 2500 ng/mL) or EPO (10 U/mL). MTT reduction assay was performed after 3 days of culture. The values represent the mean ± SD from triplicate cultures and are expressed as a percentage of maximal response to EPO.

Growth curve of the transfectant cells expressing chimeric receptors in response to G-CSF.

Parental UT-7/EPO cells or the transfectants expressing GEY0, GEY3, GEY5, GEY8, GEY4F, or GEY5F were cultured with various concentrations of G-CSF (0.25 to 2500 ng/mL) or EPO (10 U/mL). MTT reduction assay was performed after 3 days of culture. The values represent the mean ± SD from triplicate cultures and are expressed as a percentage of maximal response to EPO.

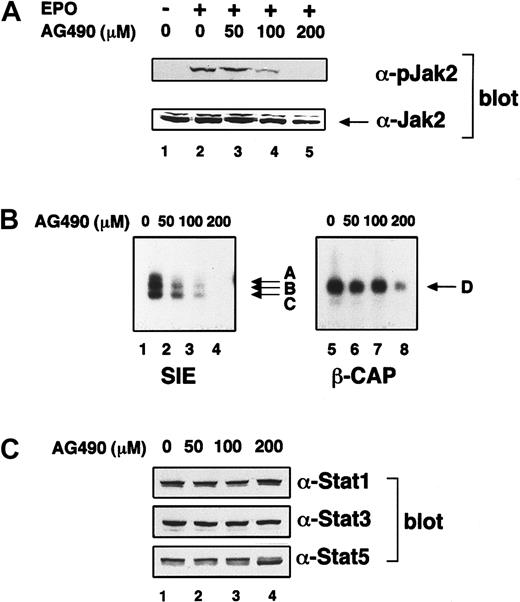

Jak2 activates Stat1 and Stat3 in response to EPO in UT-7/EPO cells

On cytokine stimulation, Stat proteins are phosphorylated at the specific tyrosine residues that are required for dimerization. Several protein tyrosine kinases can phosphorylate Stat proteins. Among them, Jak2 tyrosine kinase is activated by EPO21,22 and induces tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat5.23 Lyn also activates Stat5.24,25 However, it is still open to question which tyrosine kinase(s) phosphorylates Stat1 and Stat3 proteins on EPO treatment. First, using UT-7/EPO cells, we examined whether Jak2 tyrosine kinase can induce activation of Stat1 and Stat3 in response to EPO. For this purpose, we used AG490 as an inhibitor of Jak2.26 UT-7/EPO cells were pretreated with various concentrations of AG490 for 16 hours and subsequently stimulated with EPO (10 U/mL). Ten minutes later, the cells were harvested for Western blotting and EMSA. AG490 clearly inhibited the EPO-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Jak2 tyrosine kinase (Figure5A). AG490 suppressed Jak2 tyrosine kinase activity up to 20% of the control at 100 μM AG490 at which dosage the DNA-binding activity of Stat1 and Stat3 was significantly reduced (Figure 5B, lanes 1-4). These results indicate that the activation of Stat1 and Stat3 is dependent on Jak2 activation. In contrast, Stat5 activation was not suppressed even after treatment with 100 μM AG490 (Figure 5B, lanes 7), and 200 μM AG490 was required for strong inhibition of Stat5 activation (Figure 5B, lane 8). AG490 did not affect the expression of either Stat protein (Figure 5C), indicating that the reduced DNA-binding activities were not due to the down-regulation of each Stat protein level.

Jak2 is involved in EPO-induced Stat1 and Stat3 activation.

(A) The effect of AG490 on EPO-induced activation of Jak2. UT-7/EPO cells were starved for 8 hours and subsequently treated with the indicated concentration of AG490. Then, 16 hours later, the cells were stimulated with EPO (10 U/mL) for 7 minutes, and the supernatants were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. Next, the membrane was blotted with antiphosphoJak2 antibody. The same membrane was stripped and reblotted with anti-Jak2 antibody to confirm equal loading of protein. (B) The effect of AG490 on EPO-induced Stat1 and Stat3 activation. UT-7/EPO cells were starved for 8 hours and subsequently treated with the indicated concentration of AG490. Then, 16 hours later, the cells were stimulated with EPO (10 U/mL) for 15 minutes, and the nuclear fractions were extracted for EMSA. (C) The effect of AG490 on expression of Stat proteins. UT-7/EPO cells were starved for 8 hours and subsequently treated with the indicated concentration of AG490. Then, 16 hours later, the cells were stimulated with EPO (10 U/mL) for 15 minutes, and total cell lysates were prepared for Western blotting with each anti-Stat antibody.

Jak2 is involved in EPO-induced Stat1 and Stat3 activation.

(A) The effect of AG490 on EPO-induced activation of Jak2. UT-7/EPO cells were starved for 8 hours and subsequently treated with the indicated concentration of AG490. Then, 16 hours later, the cells were stimulated with EPO (10 U/mL) for 7 minutes, and the supernatants were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. Next, the membrane was blotted with antiphosphoJak2 antibody. The same membrane was stripped and reblotted with anti-Jak2 antibody to confirm equal loading of protein. (B) The effect of AG490 on EPO-induced Stat1 and Stat3 activation. UT-7/EPO cells were starved for 8 hours and subsequently treated with the indicated concentration of AG490. Then, 16 hours later, the cells were stimulated with EPO (10 U/mL) for 15 minutes, and the nuclear fractions were extracted for EMSA. (C) The effect of AG490 on expression of Stat proteins. UT-7/EPO cells were starved for 8 hours and subsequently treated with the indicated concentration of AG490. Then, 16 hours later, the cells were stimulated with EPO (10 U/mL) for 15 minutes, and total cell lysates were prepared for Western blotting with each anti-Stat antibody.

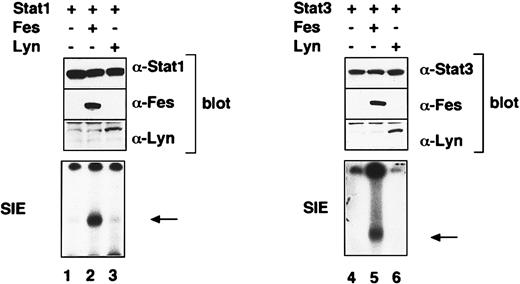

Fes tyrosine kinase directly activates Stat1 and Stat3 in 293T cells

Besides Jak2, EPO activates protein tyrosine kinases Lyn, Syk, and Fes.27,28 Reports showed that Lyn and Fes can activate Stat proteins.25 29 These findings raised the possibility that Fes and/or Lyn also contributes to the activation of Stat1 and Stat3 after EPO treatment. To examine whether or not Fes and Lyn directly activate Stat1 and Stat3, we cotransfected lyn orc-fes cDNA with Stat1 or Stat3 cDNA into 293T cells. EMSA revealed that Fes clearly activates both Stat1 and Stat3 (Figure6, lanes 2 and 5). By contrast, neither Stat1 nor Stat3 was activated by Lyn (Figure 6, lanes 3 and 6).

Fes activates Stat1 and Stat3 in 293T cells.

The 293T cells were transfected with the indicated combination of expression vectors containing Stat1, Stat3,lyn, or c-fes cDNAs and, 48 hours later, harvested for extraction of total cell lysates and nuclear fractions. The activated Stat bands are indicated by arrows.

Fes activates Stat1 and Stat3 in 293T cells.

The 293T cells were transfected with the indicated combination of expression vectors containing Stat1, Stat3,lyn, or c-fes cDNAs and, 48 hours later, harvested for extraction of total cell lysates and nuclear fractions. The activated Stat bands are indicated by arrows.

Fes is involved in EPO-induced activation of Stat1 and Stat3

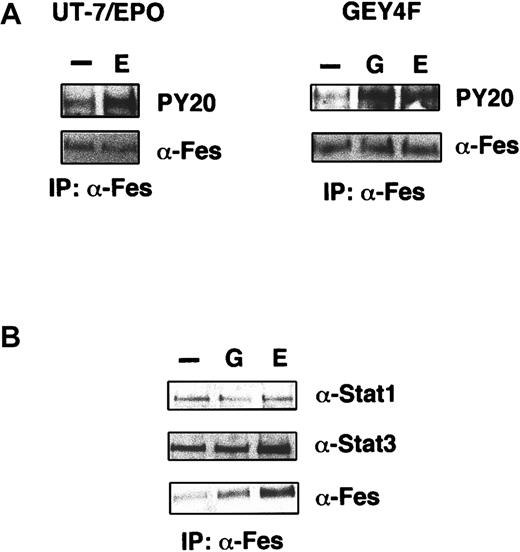

We examined whether or not Fes is actually activated by EPO in UT-7/EPO cells. Cytokine-starved UT-7/EPO cells were stimulated with EPO for 7 minutes, and then the cells were harvested for preparation of cell lysates. Supernatants were immunoprecipitated with anti-Fes antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting using antiphosphotyrosine antibody PY20. Fes was tyrosine phosphorylated after EPO stimulation (Figure7A, left panel) in UT-7/EPO cells. In addition, not only EPO but also G-CSF induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Fes in UT-7/EPO/GEY4F cells (Figure 7A, right panel). These findings indicate that Fes is indeed activated by EPO and that Tyr432 (Y4) on human EPOR is not essential for EPO-induced activation of Fes.

Fes is activated by EPO stimulation and constitutively associates with Stat1 and Stat3.

(A) Phosphorylation of Fes by EPO stimulation in UT-7/EPO (left panel) or UT-7/EPO/GEY4F cells (right panel). EPO-starved cells were stimulated with EPO (10 U/mL) or G-CSF (200 ng/mL) for 7 minutes, and the cell lysates were prepared for immunoprecipitation with anti-Fes antibody. Western blotting analysis was performed by using antiphosphotyrosine (PY-20) or anti-Fes antibody. (B) Complex formation of Fes, Stat1, and Stat3. EPO-starved cells were stimulated with EPO (10 U/mL) for 7 minutes, and the cell lysates were prepared for immunoprecipitation with anti-Fes. Western blotting analysis was performed by using antibodies against Stat1, Stat3, or Fes.

Fes is activated by EPO stimulation and constitutively associates with Stat1 and Stat3.

(A) Phosphorylation of Fes by EPO stimulation in UT-7/EPO (left panel) or UT-7/EPO/GEY4F cells (right panel). EPO-starved cells were stimulated with EPO (10 U/mL) or G-CSF (200 ng/mL) for 7 minutes, and the cell lysates were prepared for immunoprecipitation with anti-Fes antibody. Western blotting analysis was performed by using antiphosphotyrosine (PY-20) or anti-Fes antibody. (B) Complex formation of Fes, Stat1, and Stat3. EPO-starved cells were stimulated with EPO (10 U/mL) for 7 minutes, and the cell lysates were prepared for immunoprecipitation with anti-Fes. Western blotting analysis was performed by using antibodies against Stat1, Stat3, or Fes.

To clarify the physical association of Fes and Stat1/Stat3 proteins, we performed a coimmunoprecipitation assay by using antibodies against Fes, Stat1, or Stat3. After stimulation with medium alone, G-CSF, or EPO, UT-7/EPO/GEY8 cells were lysed and supernatants were immunoprecipitated with anti-Fes antibody. Western blotting using anti-Stat1 or anti-Stat3 antibody revealed ligand-independent association of these Stat proteins with Fes (Figure 7B). By contrast, reciprocal experiments with antibody against Stat1 or Stat3 revealed that Fes was not coimmunoprecipitated with Stat1 or Stat3 (data not shown). This discrepancy may be due in part to the difference in expression levels of Fes and Stat proteins.30

Next, to elucidate the biologic role of Fes in EPO signaling, we generated UT-7/EPO transfectant cells expressing kinase inactive Fes (FES-KE).31 FES-KE inhibits wild-type Fes activation as a dominant-negative form in vitro.31 The expression level of FES-KE was confirmed by Western blotting using anti-Fes antibody in transfectants (Figure 8A). After cytokine starvation, these transfectant cells were stimulated with EPO and nuclear extracts were prepared for EMSA. The degree of Stat1 and Stat3 activation was definitely diminished in cells expressing FES-KE, and the magnitude of the inhibition paralleled the expression level of FES-KE proteins (Figure 8B). In contrast, Stat5 activation was unchanged in these transfectant cells (Figure 8B). The growth response to EPO in the transfectant cells was significantly lower than that in the parental cells (Figure 8C). These results indicate that EPO induced cell growth in part via FES-induced activation of Stat1 and Stat3 in UT-7/EPO cells.

Fes is involved in EPO-induced cell growth in UT-7/EPO cells.

(A) The expression of Fes in the transfectant clones. UT-7/EPO cells were transfected with expression vector containing the kinase-negative form of c-fes cDNA. Three neomycin-resistant clones were chosen, and the expression of the dominant-negative form of Fes was monitored by Western blotting. (B) The effect of the dominant-negative form of Fes on EPO-induced Stat1 and Stat3 activation. The parental UT-7/EPO and the transfectant cells were starved of cytokine for 24 hours and then stimulated with EPO (10 U/mL) for 15 minutes. Nuclear extracts were analyzed by EMSA using SIE and β-CAP probes. (C) The growth response curve of parental UT-7/EPO and the transfectant cells expressing the mutant FES. MTT reduction assay was performed after 3 days of culture. The values represent the mean ± SD from triplicate cultures.

Fes is involved in EPO-induced cell growth in UT-7/EPO cells.

(A) The expression of Fes in the transfectant clones. UT-7/EPO cells were transfected with expression vector containing the kinase-negative form of c-fes cDNA. Three neomycin-resistant clones were chosen, and the expression of the dominant-negative form of Fes was monitored by Western blotting. (B) The effect of the dominant-negative form of Fes on EPO-induced Stat1 and Stat3 activation. The parental UT-7/EPO and the transfectant cells were starved of cytokine for 24 hours and then stimulated with EPO (10 U/mL) for 15 minutes. Nuclear extracts were analyzed by EMSA using SIE and β-CAP probes. (C) The growth response curve of parental UT-7/EPO and the transfectant cells expressing the mutant FES. MTT reduction assay was performed after 3 days of culture. The values represent the mean ± SD from triplicate cultures.

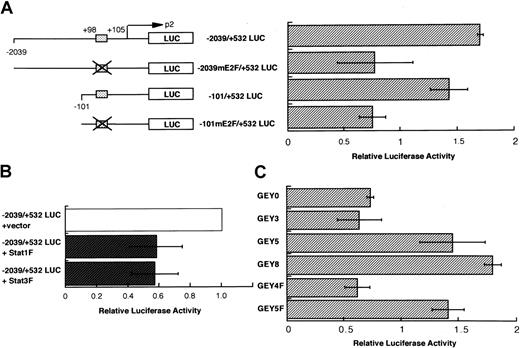

EPO-induced activation of Stat1 and Stat3 is involved in c-myc gene activation

The results above indicate that the activation of Stat1 and Stat3 induces the cellular proliferation in response to EPO. Studies reported that Stat1 and Stat3 proteins regulate the gene expression of several mitogenesis-associated molecules, including cyclins and c-myc.18,32 It was previously reported that the overexpression of c-myc causes erythroleukemia in transgenic mice.33 On the basis of these observations, we examined whether or not Stat1 and/or Stat3 enhances the transcription of thec-myc gene after EPO stimulation. We introducedc-myc promoter reporter constructs containing a normal or mutated Stat binding site into UT-7/EPO cells.18Introduction of the mutation at the Stat binding site clearly reduced the activity of the c-myc promoter (Figure9A). In addition, coexpression of the dominant-negative form of Stat1 and Stat334 also decreased the reporter activity (Figure 9B). We also analyzed thec-myc promoter activity in cells expressing chimeric receptors. EPO induced an elevation of c-myc promoter activity equally in all the cell lines (data not shown). In contrast, G-CSF induced the c-myc promoter activity in UT-7/EPO/GEY8, UT-7/EPO/GEY5, and UT-7/EPO/GEY5F clones but not in UT-7/EPO/GEY3, UT-7/EPO/GEY0, and UT-7/EPO/GEY5F clones (Figure9C). These results strongly suggest that c-myc is one of the target genes for activated Stat1 and Stat3 in EPO signaling.

Activation of Stat1 and Stat3 is required for the

c-myc gene activation. (A) EPO-induced activation of c-myc promoter via the putative binding site of Stat1 and Stat3. Luciferase reporter constructs containing human c-mycgene promoter and internal control reporter plasmid pRL-TK vector were introduced into UT-7/EPO cells. The cells were starved for 12 hours and then transfected with the reporter constructs. After an additional 12 hours of incubation, the cells were treated with or without EPO (10 U/mL). Finally, 6 hours later, the cells were harvested for dual luciferase assay. The results for EPO-exposed cells are expressed as a fold-induction of the luciferase activity of the same construct in the control condition (without EPO). The values represent the mean ± SD from triplicate experiments. The box indicates the putative binding site of Stat1 and Stat3. (B) The effects of dominant-negative Stat1 and Stat3 on EPO-induced activation of c-myc promoter. Thec-myc reporter constructs −2039/+532 myc were introduced into the UT-7/EPO cells with expression vector pCAGGS-neo or pCAGGS-Stat1F bearing cDNA encoding dominant-negative Stat1, or with pCAGGS-Stat3F bearing the cDNA encoding dominant-negative Stat3. After transfection, the cells were cultured with EPO for 6 hours and then harvested for luciferase assay. The results are expressed as a fold-induction of the luciferase activity of the combination of −2039/+532 myc and pCAGGS vector. The values represent the mean ± SD from triplicate experiments. (C) G-CSF–induced activation ofc-myc promoter in UT-7/EPO cells expressing the chimeric receptor. The transfectant cells were starved for 12 hours and then introduced with the −2039/+532 myc reporter constructs. After an additional 12 hours of incubation, the cells were treated with or without G-CSF (250 ng/mL) for 6 hours and then harvested for luciferase assay. The results for G-CSF–exposed cells are expressed as a fold-induction of the luciferase activity of the same construct in the control condition (without G-CSF). The values represent the mean ± SD from triplicate experiments.

Activation of Stat1 and Stat3 is required for the

c-myc gene activation. (A) EPO-induced activation of c-myc promoter via the putative binding site of Stat1 and Stat3. Luciferase reporter constructs containing human c-mycgene promoter and internal control reporter plasmid pRL-TK vector were introduced into UT-7/EPO cells. The cells were starved for 12 hours and then transfected with the reporter constructs. After an additional 12 hours of incubation, the cells were treated with or without EPO (10 U/mL). Finally, 6 hours later, the cells were harvested for dual luciferase assay. The results for EPO-exposed cells are expressed as a fold-induction of the luciferase activity of the same construct in the control condition (without EPO). The values represent the mean ± SD from triplicate experiments. The box indicates the putative binding site of Stat1 and Stat3. (B) The effects of dominant-negative Stat1 and Stat3 on EPO-induced activation of c-myc promoter. Thec-myc reporter constructs −2039/+532 myc were introduced into the UT-7/EPO cells with expression vector pCAGGS-neo or pCAGGS-Stat1F bearing cDNA encoding dominant-negative Stat1, or with pCAGGS-Stat3F bearing the cDNA encoding dominant-negative Stat3. After transfection, the cells were cultured with EPO for 6 hours and then harvested for luciferase assay. The results are expressed as a fold-induction of the luciferase activity of the combination of −2039/+532 myc and pCAGGS vector. The values represent the mean ± SD from triplicate experiments. (C) G-CSF–induced activation ofc-myc promoter in UT-7/EPO cells expressing the chimeric receptor. The transfectant cells were starved for 12 hours and then introduced with the −2039/+532 myc reporter constructs. After an additional 12 hours of incubation, the cells were treated with or without G-CSF (250 ng/mL) for 6 hours and then harvested for luciferase assay. The results for G-CSF–exposed cells are expressed as a fold-induction of the luciferase activity of the same construct in the control condition (without G-CSF). The values represent the mean ± SD from triplicate experiments.

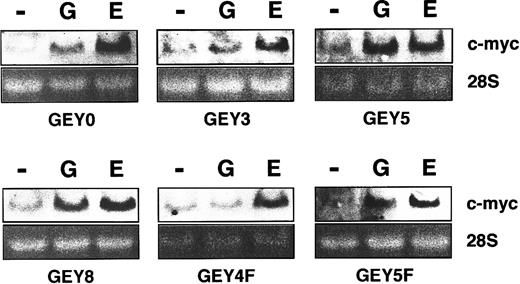

Tyr432 (Y4) on human EPOR is important for

c-myc gene induction. UT-7/EPO cells having series of chimeric receptors were starved for 24 hours and then exposed to EPO (10 U/mL) or G-CSF (250 ng/mL). One hour later, total cellular RNA was isolated and subjected to Northern blot analysis for c-myc mRNA expression. Ethidium bromide staining of the gels is shown as a loading control.

Tyr432 (Y4) on human EPOR is important for

c-myc gene induction. UT-7/EPO cells having series of chimeric receptors were starved for 24 hours and then exposed to EPO (10 U/mL) or G-CSF (250 ng/mL). One hour later, total cellular RNA was isolated and subjected to Northern blot analysis for c-myc mRNA expression. Ethidium bromide staining of the gels is shown as a loading control.

To confirm this notion, we checked whether c-myc messenger RNA (mRNA) is induced by EPO or G-CSF stimulation in the transfectants. Northern blotting analysis revealed that EPO induced the expression of c-myc mRNA in all the transfectants. However, G-CSF induced c-myc mRNA in UT-7/EPO/GEY8, UT-7/EPO/GEY5, and UT-7/EPO/GEY5F clones but not in UT-7/EPO/GEY3 and UT-7/EPO/GEY4F clones. G-CSF slightly induced c-myc mRNA in UT-7/EPO/GEY0 (see “Discussion”).

Discussion

In this study, we examined the mechanism by which Stat1 and Stat3 are activated after EPO treatment. Experiments with serially mutated cytoplasmic EPORs revealed that the fourth tyrosine residue from the transmembrane, Tyr432 (Y4), is required for Stat1 and Stat3 activation. In addition, we demonstrated that Jak2 and Fes tyrosine kinases are involved in EPO-induced activation of Stat1 and Stat3. Finally, we identified one of the target genes for Stat1 and Stat3 asc-myc downstream of the EPO signal transduction pathway.

The sequence containing Tyr432 on human EPOR we identified is TyrLeuValVal (YLVV). This sequence is apparently different from the known Stat1 or Stat3 recruitment motif. For example, Stat3 activation requires the amino acid sequence TyrXaaXaaGln (YXXQ).35 A novel amino acid motif TyrXaaXaaCys (YXXC) on G-CSFR was found to work as the docking site for Stat3.36 However, none of the tyrosine residues on EPOR contain identified Stat1 and Stat3 consensus-binding motifs.35,37 We previously showed relatively slow kinetics of Stat1 and Stat3 activation and a requirement for a high concentration of ligand for the activation of these Stat proteins, compared with that of Stat5.13Furthermore, it required a higher concentration of peptides containing phospho-Tyr432 to completely block the DNA-binding activity of Stat1 and Stat3 than peptides containing phospho-Tyr767 or phospho-Tyr905 on gp130 which Stat3 directly binds to (100 μM versus 30 μM)36 (data not shown). In other words, this result suggested that the affinity of phospho-Tyr432 on EPOR to Stat3 is significantly lower than that of phospho-Tyr767 or phospho-Tyr905 on gp130 to Stat3. Therefore, Stat1 and Stat3 activation may have occurred indirectly through an association of Tyr432 on EPOR and an adaptor protein. If so, although speculative at present, one of the candidates for adaptor molecules is Ship1 (SH2 inositol 5-phosphatase 1), because Ship1 can directly bind to Tyr432 on EPOR38 and works as an adaptor molecule for several signal transduction molecules, including Grb1, Shc, and Gab.39

We showed that Jak2 inhibitor AG490 inhibited the EPO-induced Stat1 and Stat3 activation in UT-7/EPO cells. This result indicates that Jak2 activated Stat1 and Stat3 in response to EPO. Interestingly, the EPO-induced activation of Stat1 and of Stat3 was more sensitive to AG490 than that of Stat5. Treatment with 100 μM AG490 clearly inhibited the activation of Jak2 and suppressed the DNA-binding activity of Stat1 and Stat3 up to 20% of the control. However, Stat5 activity was almost unchanged even in the presence of 100 μM AG490, indicating that the loss of Stat1 and Stat3 activation is not due to cell damage caused by AG490. Indeed, cell viability was almost 100% when the cells were treated with 100 μM AG490 for 16 hours. These findings also suggest that the large reduction in activity of Jak2 is enough for Stat5 activation. Collectively, our results indicate that for their activation Stat1 and Stat3 require the activity of Jak2 much more than Stat5. This notion is consistent with our previous finding that expression of a large number of EPORs on the cell surface was required for EPO-induced activation of Stat1 and Stat3, compared with Stat5.13,40 It was reported that AG490 inhibited the activation of Jak3.41 Therefore, AG490 might have inhibited the activation of these Stat proteins via suppression of Jak3 activity. However, this inhibition is unlikely because Jak3 was not actually activated by EPO in UT-7/EPO cells (data not shown),

We also demonstrated that Fes but not Lyn activated both Stat1 and Stat3 in 293T cells. Although it is controversial whether or not EPO activates Fes tyrosine kinases,21,28 we confirmed in this study that EPO actually activates Fes in UT-7/EPO cells. In addition, it was found that a dominant-negative Fes inhibited the EPO-induced proliferation of UT-7/EPO cells. Taken together with the report that c-Fes is expressed in CD34+ human hematopoietic progenitor cells and the expression level declines during the EPO-induced erythroid differentiation of CD34+ cells,42our results suggest that activation of Stat1 and Stat3 is down-regulated on terminal differentiation of erythroid cells. This notion may in part explain why a dominant-negative Stat3 did not inhibit the erythroid colony formation from relatively mature erythroid progenitor CFU-E in fetal liver cells.6

We found that Fes is associated with Stat1 and Stat3 without EPO stimulation. Because the activation of Fes requires EPO in UT-7/EPO cells, it is possible that Fes interacts with Stat proteins through a specific domain distinct from SH2 domain that binds to a tyrosyl-phosphorylated residue. Recently, it has been reported that the coiled-coil domain of c-fer, a member of the Fes family, is critical for Stat3 activation.43 Therefore, Fes may interact with Stat1 and Stat3 through its coiled-coil domain.31

Tyr432 (Y4) on human EPOR was essential for EPO-induced activation of Stat1 and Stat3. However, this tyrosine residue was not prerequisite for Fes activation because G-CSF induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Fes in UT-7/EPO/GEY4F cells (Figures 3A and 7A). These results also suggest that activated Fes is required but not sufficient for Stat1 and Stat3 activation. Association of Fes/Stat1/Stat3 complex and Tyr432 on human EPOR may trigger the conformational change of the complex, resulting in the activation of Stat1 and Stat3. Thus, Tyr432 on human EPOR may work as a scaffold for Fes-induced activation of Stat1 and Stat3. However, whether the complex is directly associated with Tyr432 on human EPOR remains debatable.

Stat proteins regulate the expression of the genes inducing cell cycling and preventing apoptosis. Stat3 enhanced the expression ofcyclin D1, cyclin D2, and c-myc genes in interleukin 6-responsive cell lines.18,32 Stat1 induced the expression of Bcl-XL in response to cardiotrophin.9 In myeloma cells, a constitutive activation of Stat3 enhanced the expression of the Bcl-XLgene.10 In addition, constitutively active mutant of Stat3 caused the elevation of cyclin D1, Bcl-XL, andc-myc gene expression in transformed cells.44Therefore, it is possible that the aberrant expression and dysregulation of these genes induced by constitutively activated Stat proteins are involved in oncogenesis. We demonstrated here that Stat1 and Stat3 increased the c-myc gene promoter activity after EPO treatment. Moreover, when UT-7/EPO cells were used for the reporter assay, EPO increased the c-myc gene promoter activity, and the activity was significantly diminished by deletion of the Stat-binding site in the promoter. In addition, G-CSF–inducedc-myc promoter activity was detected only in chimeric mutants that had the ability to activate Stat1 and Stat3 after G-CSF stimulation. Finally, overexpression of dominant-negative forms of Stat1 and Stat3 decreased the EPO-induced c-myc promoter activity. As described previously,18 the Stat-binding site in the c-myc gene promoter also contains the putative E2F-binding site. Therefore, it is possible that E2F contributes to the EPO-induced c-myc expression at the same site. Indeed, neither Stat1F nor Stat3F completely inhibited the c-mycpromoter activity. Previous studies reported that EPO rapidly induced the c-myc expression in normal murine erythroid cells45 and c-myc expression was required for the growth of human and murine erythroid progenitors.46 In addition, the transgenic mice overexpressing the c-myc in erythroid lineage cells developed erythroleukemia.32Considering these observations, an aberrant expression of thec-myc gene activated by Stat3 and presumably in part by Stat1 may be one of the causes of erythroleukemia.

Surprisingly, the growth response to G-CSF was about 50% of that to EPO in UT-7/EPO/GEY0. UT-7/EPO/GEY0 cells have the chimeric receptor containing the box1 and box2 regions but not any cytoplasmic tyrosine residues. When the transfectants were stimulated with G-CSF, Jak2 tyrosine kinase was activated but Stat proteins were not (Figures 3A,B and data not shown). This finding suggested that the growth of UT-7/EPO/GEY0 cells was mediated by Jak2 and its downstream-signaling molecules other than Stat proteins. In addition, UT-7/EPO/GEY0 showed an enhanced mitogenic response to G-CSF compared with UT-7/EPO/GEY3 at 10 to 1000 ng/mL G-CSF (P < .01). Consistent with this finding, c-myc mRNA was slightly induced by G-CSF stimulation in UT-7/EPO/GEY0 but not in UT-7/EPO/GEY3. These findings can be explained in 2 ways. First, GEY0 lacks the binding site for hematopoietic protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 (also called HCP, SH-PTP1, and PTP1C) on EPOR. It was reported that Tyr430 (Y3) (corresponding to Tyr429 on murine EPOR) in the cytoplasmic domain of human EPOR is the binding site for SHP-1.47 SHP-1 inactivates “active” Jak2 by dephosphorylation, resulting in the termination of proliferative signals.47 Therefore, loss of the SHP-1–binding site on EPOR resulted in prolonged G-CSF–induced phosphorylation of Jak2 and hypersensitivity to G-CSF in UT-7/EPO/GEY0. Second, expression of cytokine inducible SH2-containing protein (CIS48) and Jak binding protein (JAB) (also called SOCS-1 and SSI-1)49,50may explain the difference in sensitivity to G-CSF between UT-7/EPO/GEY0 and UT-7/EPO/GEY3. CIS and JAB are transcriptionally regulated by Stat5 and function as negative regulators of the Jak2-Stat activation pathway. The evidence that Tyr344 (Y1) and Tyr402 (Y2) are independently necessary for Stat5 activation19 20 can explain our result that G-CSF cannot activate Stat5 in GEY0 lacking both Y1 and Y2 (Figure 3B). Therefore, although in this case we did not check the expression CIS and JAB, it is predicted that neither CIS nor JAB is inducibly expressed by G-CSF in UT-7/EPO/GEY0 cells.

In conclusion, EPO actually activates Stat1 and Stat3 via an identified cytoplasmic region of EPOR in a human erythroleukemia cell line. Although the physiologic function of Stat1 and Stat3 in EPO signaling is still to be elucidated, our results suggest that Stat proteins are involved in the development of normal and/or abnormal erythropoiesis, via the gene activation of c-myc.

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Cancer Research and Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan and by grants from the Yamanouchi Foundation for Research on Metabolic Disorders and Mochida Medical and Pharmaceutical Foundation.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Norio Komatsu, Division of Hematology, Department of Medicine, Jichi Medical School, Minamikawachi-machi, Tochigi-ken 329-0498, Japan; e-mail: nkomatsu@ms.jichi.ac.jp.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal