Abstract

Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S-1P) has been implicated as a second messenger preventing apoptosis by counteracting activation of executioner caspases. Here it is reported that S-1P prevents apoptosis and executioner caspase-3 activation by inhibiting the translocation of cytochrome c and Smac/DIABLO from mitochondria to the cytosol induced by anti-Fas, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), serum deprivation, and cell-permeable ceramides in the human acute leukemia Jurkat, U937, and HL-60 cell lines. Furthermore, the tumor promoter 12-O-tetradecanoyl-phorbol-13-acetate, which stimulates sphingosine kinase, the enzyme responsible for S-1P production, also inhibits cytochrome c and Smac/DIABLO release. In contrast, dimethylsphingosine (DMS), a specific inhibitor of sphingosine kinase, sensitizes cells to cytochrome c and Smac/DIABLO release triggered by anti-Fas, TNF-α, serum deprivation, or ceramide. DMS-induced mitochondrial apoptogenic factor leakage can likewise be overcome by S-1P cotreatment. Hence, S-1P, likely generated through a protein kinase C– mediated activation of sphingosine kinase, inhibits the apoptotic cascade upstream of the release of the mitochondrial apoptogenic factors, cytochrome c, and Smac/DIABLO in human acute leukemia cells.

Introduction

Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S-1P), a sphingolipid metabolite generated from sphingosine through sphingosine kinase (SphK) activation, has been implicated as a signaling molecule that promotes cell survival in response to apoptotic stimuli such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), Fas monoclonal antibody, serum deprivation, bacterial sphingomyelinase, cell-permeable ceramides, ionizing radiation, and anticancer drugs.1-10 More precisely, we have previously established that S-1P can rescue cells from apoptosis by exerting an inhibitory effect on the caspase cascade.4,10 In fact, we have shown that S-1P can inhibit the activation of executioner caspases (eg, caspase-3, -6, and -7) that cleave poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase and lamins during Fas- and ceramide-mediated apoptosis in Jurkat T cells.4Accordingly, Xia et al8 recently found that S-1P strongly reduced TNF-α–induced caspase-3 activation in human endothelial C11 cells. Nevertheless, it is not known how S-1P is linked to this caspase cascade.

A primary caspase activation cascade relies on the release of cytochrome c (cyt c) from the intermembrane space of mitochondria, which occurs in response to several apoptotic stimuli including serum deprivation, DNA damage, and activation of cell surface death receptors (reviewed in Hengartner11). Once in the cytoplasm, cyt c binds to Apaf-1,12 inducing it to associate with the inactive procaspase-9,13 thereby triggering its autoactivation into a mature form, which in turn can initiate a caspase cascade involving downstream executioner procaspase-3, -6, and -7.14 Concurrent with cytc release, another mitochondrial protein, Smac (second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase) or DIABLO (direct IAP binding protein with low pI), was recently found to be released in the cytosol in response to UV radiation.15 Whereas cytc induces multimerization of Apaf-1 to activate procaspase-9 and -3, Smac/DIABLO promotes apoptosis by binding to the inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) preventing them from sequestering caspases.15-20

Herein, we report that S-1P inhibits executioner caspase activation by significantly counteracting the release of mitochondrial proteins, cytc and Smac/DIABLO, induced by Fas monoclonal antibody (mAb), TNF-α, serum deprivation, and exogenous ceramides in human acute leukemia Jurkat, U937, and HL-60 cells. In addition, the protein kinase C activator 12-O-tetradecanoyl-phorbol-13-acetate (TPA), an established agonist of sphingosine kinase,1,8,21,22 also inhibits cyt c and Smac/DIABLO release upon apoptotic stimuli. Conversely, dimethylsphingosine (DMS), a competitive inhibitor of sphingosine kinase,23 potentiates cyt c and Smac/DIABLO release triggered by anti-Fas, TNF-α, serum deprivation, and exogenous ceramides, and its effect could be overcome by cotreatment with S-1P. Thus, our findings suggest that S-1P, likely generated through a protein kinase C-mediated activation of sphingosine kinase, can inhibit the apoptotic machinery before release of the mitochondrial apoptogenic factors, cyt c and Smac/DIABLO.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and reagents

Bcl-xL- and neomycin control vector (Neo)–transfected human T-cell leukemia Jurkat cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) supplemented with 1 mg/mL G418 as previously described.24,25 Human monocytelike U937 and promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 containing 10% and 15% FBS, respectively, as previously described.1 Cells were suspended in serum-free medium before treatment. Anti-Fas immunoglobulin M (IgM) (clone CH-11) was from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY). d-erythro-N-acetylsphingosine (C2-ceramide) andd-erythro-N-hexanoylsphingosine (C6-ceramide), DMS, and S-1P (Biomol, Plymouth Meeting, PA) were delivered as a complex with bovine serum albumin (BSA) in 4 mg/mL BSA (fatty-acid free; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Staurosporine and TPA were from Sigma-Aldrich. Escherichia coli recombinant human TNF-α was from R&D Systems (Barton, United Kingdom).

Preparation of mitochondria and Western blot analysis of cytc and Smac/DIABLO

Mitochondrial preparations were carried out as previously described.24 25 In brief, cell samples were collected by centrifugation at 600g for 5 minutes at 4°C. Cell pellets were washed once with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and resuspended with 5 vol ice-cold buffer A (20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 0.1% BSA, 1 mM sodium EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 20 μg/mL leupeptin, 10 μg/mL aprotinin, and 10 μg/mL pepstatin A) containing 250 mM sucrose. After swelling on ice for 5 minutes, the cells were homogenized with 15 to 20 strokes of a number 22 Kontes Dounce homogenizer with the B pestle (Kontes Glass, Vineland, NJ), and the homogenates were centrifuged at 750g for 5 minutes at 4°C. Supernatants were then pelleted at 10 000g for 15 minutes at 4°C. Resultant pellets containing mitochondria were resuspended in cold buffer A. Supernatants were further cleared at 20 000g for 30 minutes at 4°C. For Western blot analysis, equal amounts of mitochondrial and cytosolic proteins were separated on 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and then trans-blotted to nitrocellulose. Anti–cytochrome c mAb (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), anti-Smac/DIABLO (gift of Dr Xiadong Wang, Department of Biochemistry, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas), anti–cytochrome oxidase subunit II (COX II) mAb (Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands), and anti–β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich) were used as primary antibodies. Proteins were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce, Rockford, IL) using anti–mouse or anti–rabbit horseradish peroxidase–conjugated IgG (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Western blot analysis of caspase-3, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and Mcl-1

Cell lysate preparation and Western blot analysis were carried out as previously reported.4 24 Rabbit anti–caspase-3 (gift of Dr Donald Nicholson, Merck-Frosst Centre for Therapeutic Research, Pointe Claire-Dorval, Québec, Canada), mouse anti–Bcl-xL (Pharmingen), mouse anti–Bcl-2 (Dako, Trappes, France), and rabbit anti–Mcl-1 (Pharmingen) were used as primary antibodies. Proteins were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce) using anti–rabbit or anti–mouse horseradish peroxidase–conjugated IgG (Bio-Rad).

Fluorogenic DEVD cleavage enzyme assay

Enzyme reactions were performed with 25 μg cytosolic proteins and a final concentration of 20 μM Ac-DEVD-AMC substrate (Bachem, Voisins, France).4 After 30-minute incubation at room temperature, the amount of the released fluorescent product, aminomethylcoumarin, was determined using a Jobin-Yvon spectrofluorometer (at 351 and 430 nm for the excitation and emission wavelengths, respectively).

Cell viability assay

The MTT reagent (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) was used to determine cell death as previously described.26 After treatment, cells (100 μL) were incubated with 10 μL MTT solution (5 mg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) in 96-well plates for approximately 4 hours. After solubilization for 16 hours with 100 μL lysis buffer (20% SDS in 50% N,N-dimethylformamide), formazan was quantified by spectrophotometry with a microplate reader at 560 nm absorbance.

Results

TPA and S-1P inhibit cell surface death receptor–mediated release of cyt c and Smac/DIABLO

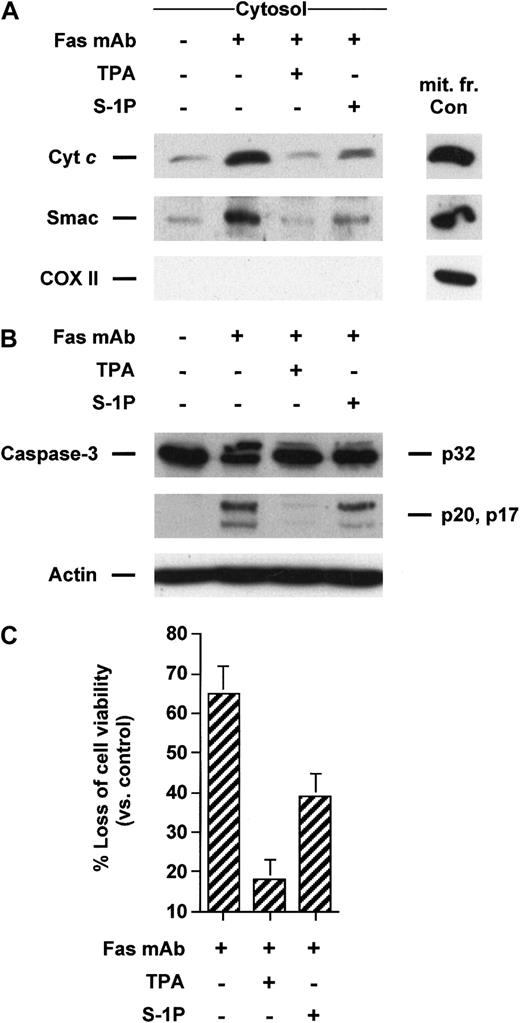

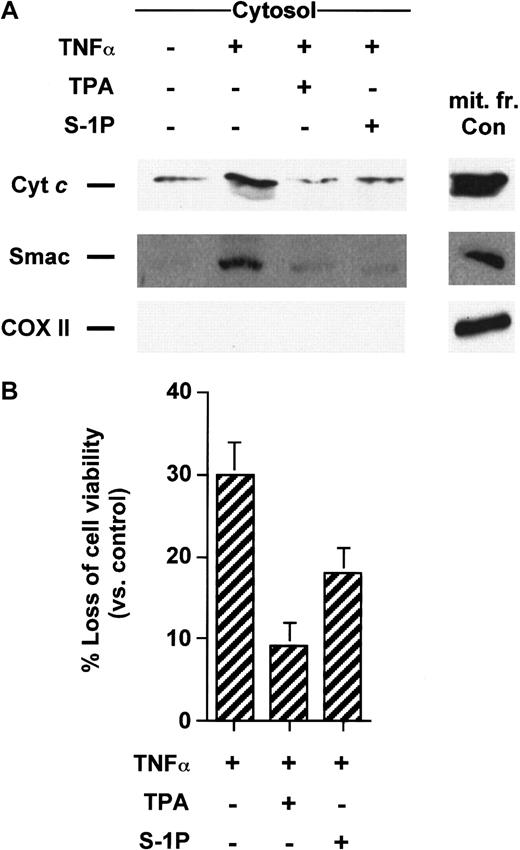

Apoptosis induced by Fas mAb and TNF-α can be blocked by the activation of protein kinase C by the tumor-promoting phorbol ester TPA in Jurkat4,27,28 and U937 cells,1,29,30respectively. To evaluate whether TPA could inhibit the translocation of cyt c and Smac/DIABLO from mitochondria to the cytosol initiated by these cell surface death receptors, Jurkat and U937 cells were respectively treated with Fas mAb and TNF-α in the absence or presence of TPA. Jurkat cells treated with Fas antibody underwent cytosolic cyt c accumulation that was strongly diminished in cells treated with TPA (Figure 1A). Similarly, TPA also impeded Smac/DIABLO release from the mitochondria triggered by Fas mAb (Figure 1A). TPA-promoted blockade of mitochondrial death molecules was correlated with the inhibition of caspase-3 activation (Figure 1B), as previously reported.4,27 28 As shown in Figure2A, both cyt c and Smac/DIABLO translocation induced by TNF-α could be suppressed by cotreatment with TPA in U937 cells. Caspase-3–like increased activity was also blocked in TPA-treated cells in response to TNF-α (data not shown). Finally, TPA inhibited cell death initiated by Fas mAb or TNF-α (Figures 1C, 2B) in Jurkat T and U937 cells, respectively.

TPA and S-1P inhibit cyt c and Smac/DIABLO release, caspase-3 activation, and loss of viability induced by anti-Fas in Jurkat cells.

(A) Cytosolic extracts from Jurkat cells treated for 3 hours with 50 ng/mL anti-Fas antibody alone or after pretreatment with 50 nM TPA or 5 μM S-1P for 15 minutes were subjected to 15% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti–cyt c, anti-Smac/DIABLO, and anti-COX II (cytochrome oxidase serves as a marker for mitochondrial contamination of cytosolic extracts). A mitochondrial extract from nontreated cells (mit. fr. Con) was used as a positive control for cytc, Smac/DIABLO, and COX II. (B) Proteins from duplicate extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti–caspase-3 antibody. The mobilities of the 32-kd precursor (p32) and proteolytically processed forms (p20 and p17) are indicated. Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments. (C) Jurkat cells were treated for 5 hours in the conditions described above. Loss of viability was assessed by the MTT assay. Samples were made in quadruplicate. Mean values with standard deviation are shown.

TPA and S-1P inhibit cyt c and Smac/DIABLO release, caspase-3 activation, and loss of viability induced by anti-Fas in Jurkat cells.

(A) Cytosolic extracts from Jurkat cells treated for 3 hours with 50 ng/mL anti-Fas antibody alone or after pretreatment with 50 nM TPA or 5 μM S-1P for 15 minutes were subjected to 15% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti–cyt c, anti-Smac/DIABLO, and anti-COX II (cytochrome oxidase serves as a marker for mitochondrial contamination of cytosolic extracts). A mitochondrial extract from nontreated cells (mit. fr. Con) was used as a positive control for cytc, Smac/DIABLO, and COX II. (B) Proteins from duplicate extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti–caspase-3 antibody. The mobilities of the 32-kd precursor (p32) and proteolytically processed forms (p20 and p17) are indicated. Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments. (C) Jurkat cells were treated for 5 hours in the conditions described above. Loss of viability was assessed by the MTT assay. Samples were made in quadruplicate. Mean values with standard deviation are shown.

TPA and S-1P inhibit cyt c and Smac/DIABLO release and cell death induced by TNF-α in U937 cells.

(A) Cytosolic extracts from U937 cells treated for 5 hours with 50 ng/mL TNF-α alone or after pretreatment with 50 nM TPA or 5 μM S-1P for 15 minutes were subjected to 15% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-cyt c, anti-Smac/DIABLO, and anti-COX II, as described in Figure 1. (B) U937 cells were treated under the same conditions as described above. Loss of viability was assessed by the MTT assay. Samples were made in quadruplicate. Mean values with standard deviations are shown.

TPA and S-1P inhibit cyt c and Smac/DIABLO release and cell death induced by TNF-α in U937 cells.

(A) Cytosolic extracts from U937 cells treated for 5 hours with 50 ng/mL TNF-α alone or after pretreatment with 50 nM TPA or 5 μM S-1P for 15 minutes were subjected to 15% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-cyt c, anti-Smac/DIABLO, and anti-COX II, as described in Figure 1. (B) U937 cells were treated under the same conditions as described above. Loss of viability was assessed by the MTT assay. Samples were made in quadruplicate. Mean values with standard deviations are shown.

Intracellular accumulation of S-1P has been shown to be one of the effects triggered by the protein kinase C activator TPA, an established agonist of sphingosine kinase in the cell lines tested (data not shown).1,8,21,22 Hence, we next tested whether S1-P could also prevent cyt c and Smac/DIABLO leakage from the mitochondria triggered by TNF-α or anti-Fas. We found that 5 μM S1-P, a demonstrated antiapoptotic concentration in these cell lines,1,4 like TPA, was able to significantly inhibit release of the mitochondrial proteins induced by anti-Fas in Jurkat cells (Figure 1A) or TNF-α in U937 cells (Figure 2A). In Jurkat T cells, this blockade was associated with S-1P–mediated inhibition of caspase-3 cleavage (Figure 1B) and loss of viability (Figure 1C), in agreement with our previous findings.4 In a like manner, S-1P inhibited caspase-3 activation (data not shown) and apoptosis (Figure 2B) in U937 cells, in line with our previous data.1

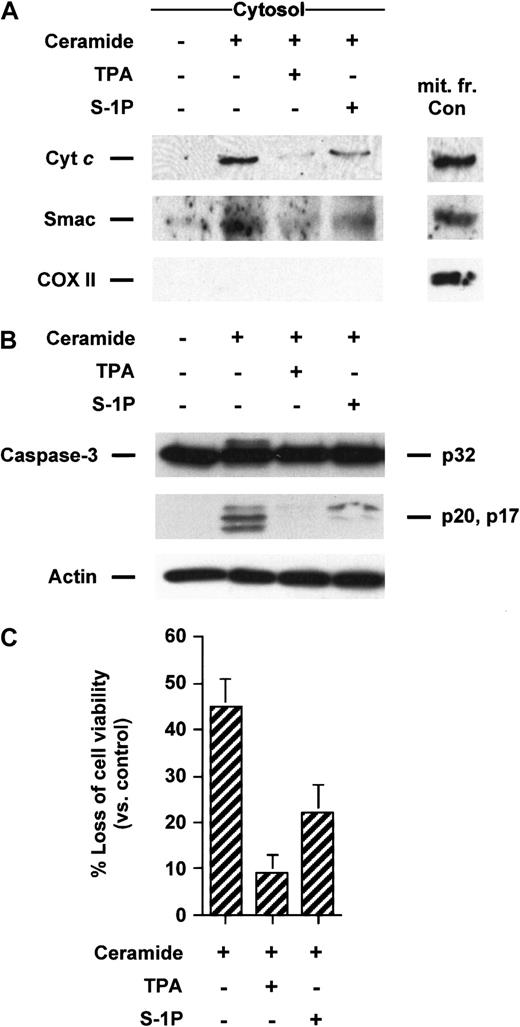

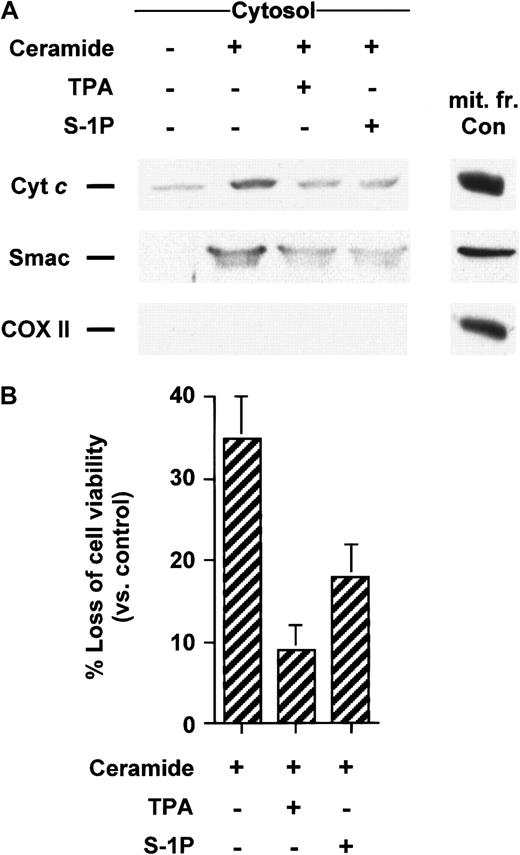

TPA and S-1P inhibit release of cyt c and Smac/DIABLO triggered by exogenous ceramide in Jurkat and U937 cells

Ceramide has been involved as an early mediator in anti-Fas–induced apoptosis in Jurkat cells25,31-34 and TNF-α–induced apoptosis in U937 cells.1,29,31,35 In addition, it is well established that the addition of ceramide analogues such as C2- or C6-ceramide initiate apoptosis in many cell types, including Jurkat and U937 cells. Recently, we have shown that C2-ceramide acts by causing the translocation of cyt c from mitochondria in Jurkat cells totally suppressed by Bcl-xL–enforced expression,25 supporting the notion that mitochondria are required for the apoptosis-inducing activity of C2-ceramide. Because we have previously demonstrated that TPA and S-1P can overcome apoptosis and executioner caspase activation in Jurkat cells,4 we tested the effects of TPA and S-1P on cyt c release triggered by exogenous ceramides. We found that both TPA and S-1P markedly inhibit cytosolic cyt caccumulation induced by C2- (data not shown) or C6-ceramide in Jurkat (Figure3A) and U937 cells (Figure4A). Analogously, exogenous ceramides triggered a release of Smac/DIABLO in both cell lines that could be strongly reduced by cotreatment with TPA or S-1P (Figures 3A, 4A). Jurkat cells exhibited a processing of caspase-3 (Figure 3B) or a loss of cell viability (Figure 3C) after C6-ceramide exposure that was inhibited when TPA or S-1P was added to the cells. Similarly, TPA or S-1P treatment markedly inhibited DEVDase increased activity (data not shown) and loss of viability (Figure 4B) when U937 cells were stimulated with C6-ceramide.

TPA and S-1P inhibit cyt c and Smac/DIABLO release, caspase-3 activation, and loss of viability in Jurkat cells induced by C6-ceramide.

(A) Cytosolic extracts from Jurkat cells treated for 5 hours with 25 μM C6-ceramide alone or after pretreatment with 50 nM TPA or 5 μM S-1P for 15 minutes were subjected to 15% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-cyt c, anti-Smac/DIABLO, and anti-COX II, as described in Figure 1. (B) Proteins from duplicate extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti–caspase-3 antibody. The mobilities of the 32-kd precursor (p32) and proteolytically processed forms (p20 and p17) are indicated. Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments. (C) Jurkat cells were treated for 5 hours, as described above. Loss of viability was assessed by the MTT assay. Samples were made in quadruplicate. Mean values with standard deviation are shown.

TPA and S-1P inhibit cyt c and Smac/DIABLO release, caspase-3 activation, and loss of viability in Jurkat cells induced by C6-ceramide.

(A) Cytosolic extracts from Jurkat cells treated for 5 hours with 25 μM C6-ceramide alone or after pretreatment with 50 nM TPA or 5 μM S-1P for 15 minutes were subjected to 15% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-cyt c, anti-Smac/DIABLO, and anti-COX II, as described in Figure 1. (B) Proteins from duplicate extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti–caspase-3 antibody. The mobilities of the 32-kd precursor (p32) and proteolytically processed forms (p20 and p17) are indicated. Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments. (C) Jurkat cells were treated for 5 hours, as described above. Loss of viability was assessed by the MTT assay. Samples were made in quadruplicate. Mean values with standard deviation are shown.

TPA and S-1P inhibit cyt c and Smac/DIABLO release and cell death in U937 cells induced by C6-ceramide.

(A) Cytosolic extracts from U937 cells treated for 5 hours with 25 μM C6-ceramide alone or after pretreatment with 50 nM TPA or 5 μM S-1P for 15 minutes were subjected to 15% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-cyt c, anti-Smac/DIABLO, and anti-COX II, as described in Figure 1. (B) U937 cells were treated as described above. Loss of viability was assessed by the MTT assay. Samples were made in quadruplicate. Mean values with standard deviation are shown.

TPA and S-1P inhibit cyt c and Smac/DIABLO release and cell death in U937 cells induced by C6-ceramide.

(A) Cytosolic extracts from U937 cells treated for 5 hours with 25 μM C6-ceramide alone or after pretreatment with 50 nM TPA or 5 μM S-1P for 15 minutes were subjected to 15% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-cyt c, anti-Smac/DIABLO, and anti-COX II, as described in Figure 1. (B) U937 cells were treated as described above. Loss of viability was assessed by the MTT assay. Samples were made in quadruplicate. Mean values with standard deviation are shown.

S-1P inhibits the release of cyt c and Smac/DIABLO triggered by serum starvation in HL-60 cells

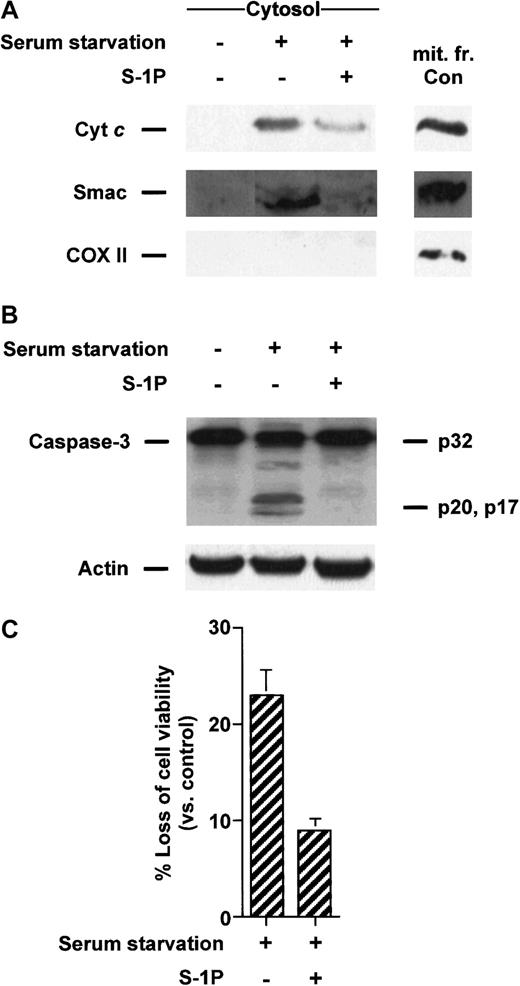

The ability of S-1P to prevent apoptosis by serum deprivation in HL-60 cells1 may be related to an attenuation of ceramide-mediated cell death given that serum removal results in the generation of ceramide in many cell types.36 37 Therefore, we wanted to determine whether S-1P repressed proapoptotic mitochondrial protein release in cells deprived of serum. Figure5A shows that 8-hour serum starvation of HL-60 cells led to an increase in the cytosolic cyt c and Smac/DIABLO content that was suppressed when S-1P was added to the cells. Similarly, proteolytic cleavage of caspase-3 (Figure 5B) and loss of viability (Figure 5C) induced by serum withdrawal were also inhibited when S1-P was present.

S-1P inhibits cyt c and Smac/DIABLO release and caspase-3 activation induced by serum deprivation in HL-60 cells.

(A) Cytosolic extracts from HL-60 cells left untreated in the presence or absence of 5 μM S-1P for 8 hours were subjected to 15% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-cyt c, anti-Smac/DIABLO, and anti-COX II, as described in Figure 1. (B) Proteins from duplicate extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti–caspase-3 antibody. The mobilities of 32-kd precursor (p32) and proteolytically processed forms (p20 and p17) are indicated. Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments. (C) HL-60 cells were treated as described above. Loss of viability was assessed by the MTT assay. Samples were made in quadruplicate. Mean values with standard deviation are shown.

S-1P inhibits cyt c and Smac/DIABLO release and caspase-3 activation induced by serum deprivation in HL-60 cells.

(A) Cytosolic extracts from HL-60 cells left untreated in the presence or absence of 5 μM S-1P for 8 hours were subjected to 15% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-cyt c, anti-Smac/DIABLO, and anti-COX II, as described in Figure 1. (B) Proteins from duplicate extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti–caspase-3 antibody. The mobilities of 32-kd precursor (p32) and proteolytically processed forms (p20 and p17) are indicated. Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments. (C) HL-60 cells were treated as described above. Loss of viability was assessed by the MTT assay. Samples were made in quadruplicate. Mean values with standard deviation are shown.

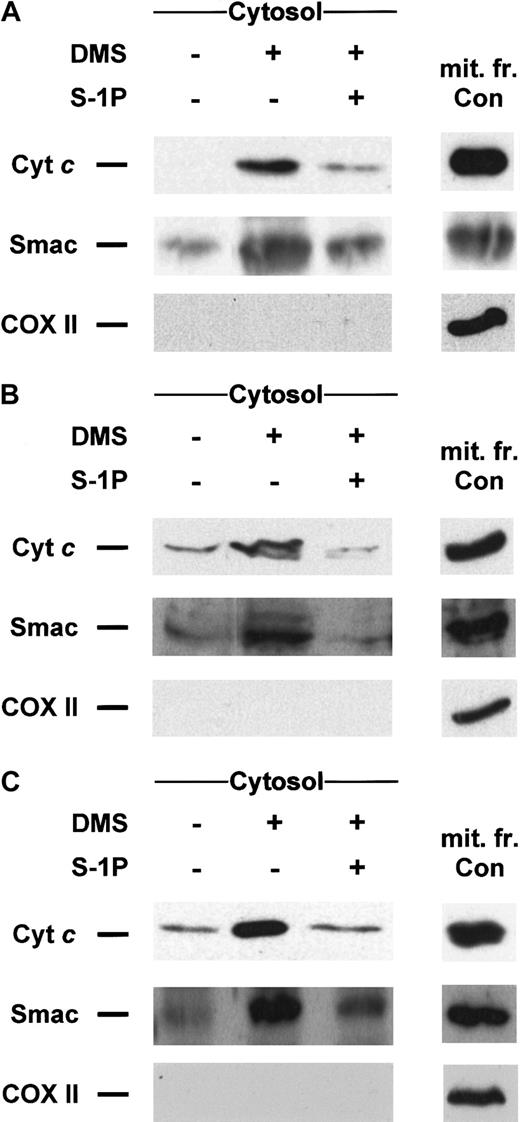

Sphingosine 1-phosphate antagonizes release of cyt cand Smac/DIABLO induced by DMS treatment

Dimethylsphingosine is a potent competitive inhibitor of sphingosine kinase23,38 able to induce apoptosis,1,5,25,39-46 which can be overcome by cotreatment with S-1P.1,2,5,44,45 Recently, we have established that treatment with DMS induces cell death in Jurkat T cells in a mitochondria-dependent manner inasmuch as the overexpression of Bcl-xL could completely prevent apoptosis and caspase-3–like proteolytic activity increase.25 Hence, we sought to determine whether the inhibition of sphingosine kinase by DMS could lead to those downstream events through the release of cytc or Smac/DIABLO. As anticipated, DMS is indeed capable of triggering translocation of both cyt c and Smac/DIABLO in Jurkat (Figure 6A), U937 (Figure 6B), and HL-60 (Figure 6C), which can be prevented in all cell lines tested by cotreatment with S-1P (Figure 6A-C). S-1P was also capable of blocking caspase-3 activation and the loss of viability in these cell lines (data not shown).

DMS-induced cyt c and Smac/DIABLO release is suppressed by cotreatment with S-1P.

Cytosolic extracts from Jurkat (A), U937 (B), or HL-60 cells (C) treated for 5 hours (A, B) or 8 hours (C) with 20 μM DMS in the presence or absence of 5 μM S-1P were subjected to 15% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-cyt c, anti-Smac/DIABLO, and anti-COX II, as described in Figure 1. Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments.

DMS-induced cyt c and Smac/DIABLO release is suppressed by cotreatment with S-1P.

Cytosolic extracts from Jurkat (A), U937 (B), or HL-60 cells (C) treated for 5 hours (A, B) or 8 hours (C) with 20 μM DMS in the presence or absence of 5 μM S-1P were subjected to 15% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-cyt c, anti-Smac/DIABLO, and anti-COX II, as described in Figure 1. Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments.

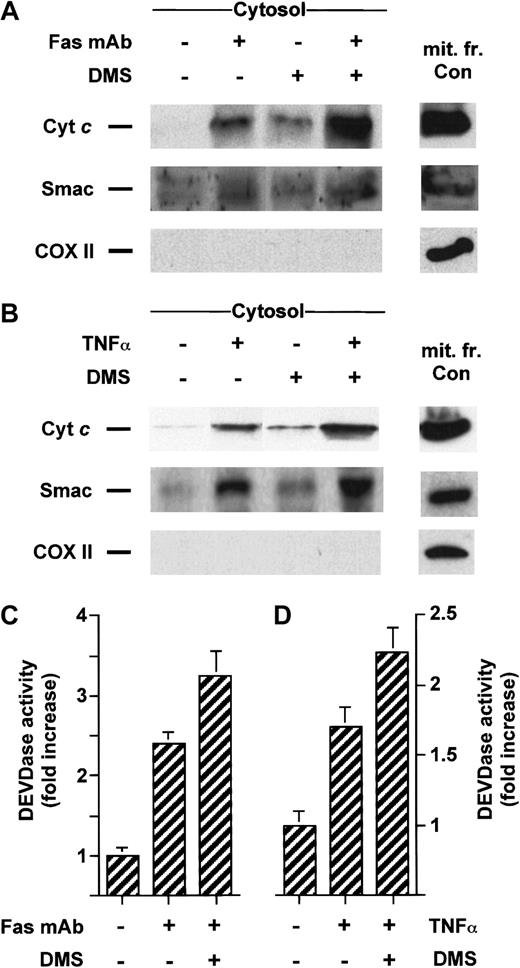

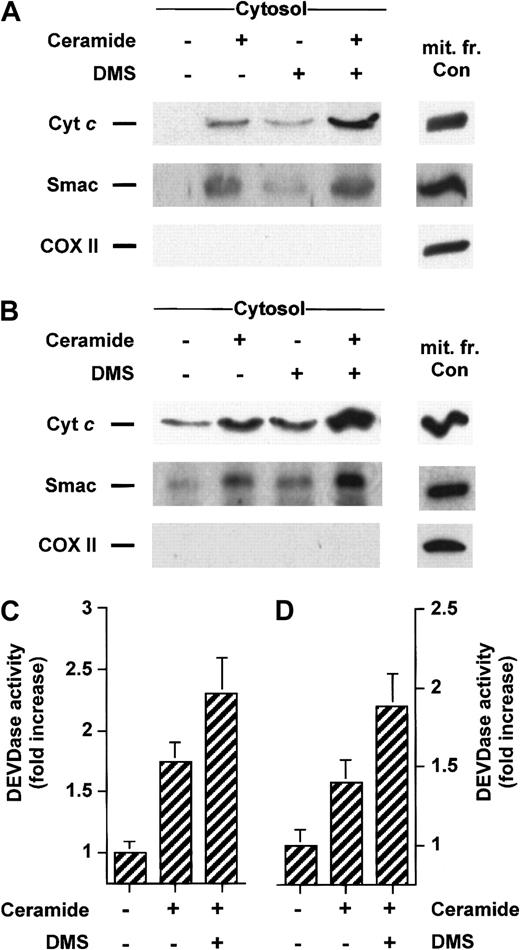

Inhibition of sphingosine kinase by DMS sensitizes cells to stimuli-induced translocation of cyt c and Smac/DIABLO

We have previously established that DMS can potentiate apoptosis induced by serum withdrawal, ionizing radiation, or bacterial sphingomyelinase treatment.1,5 46 We then asked whether inhibition of sphingosine kinase could lead to enhanced stimuli-induced release of cyt c or Smac/DIABLO. Treatment with a low concentration of DMS was indeed able to amplify the accumulation of cytosolic cyt c and Smac/DIABLO caused by Fas mAb (Figure7A) or C6-ceramide (Figure8A) treatment in Jurkat cells and enhanced caspase-3–like proteolytic activity (Figures 7C and 8C, respectively). A similar result was found in U937 cells costimulated with TNF-α (Figure 7B) or C6-ceramide (Figure 8B), which was accompanied by enhanced caspase-3–like proteolytic activity (Figures 7C, 8C).

DMS potentiates cyt c and Smac/DIABLO release and caspase-3 activation induced by cell surface death receptors.

Jurkat (A) or U937 cells (B) were preincubated with 5 μM DMS for 15 minutes and then treated for an additional 3 hours without or with 50 ng/mL anti-Fas antibody or for 5 hours with 50 ng/mL TNF-α, respectively. Cytosolic extracts were subjected to 15% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-cyt c, anti-Smac/DIABLO, and anti-COX II, as described in Figure 1. Caspase-3–like activity in duplicate extracts from Jurkat (C) or U937 cells (D) was measured with the fluorogenic substrate Ac-DEVD-AMC. Results are means of 3 independent experiments.

DMS potentiates cyt c and Smac/DIABLO release and caspase-3 activation induced by cell surface death receptors.

Jurkat (A) or U937 cells (B) were preincubated with 5 μM DMS for 15 minutes and then treated for an additional 3 hours without or with 50 ng/mL anti-Fas antibody or for 5 hours with 50 ng/mL TNF-α, respectively. Cytosolic extracts were subjected to 15% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-cyt c, anti-Smac/DIABLO, and anti-COX II, as described in Figure 1. Caspase-3–like activity in duplicate extracts from Jurkat (C) or U937 cells (D) was measured with the fluorogenic substrate Ac-DEVD-AMC. Results are means of 3 independent experiments.

DMS potentiates cyt c and Smac/DIABLO release and caspase-3 activation induced by ceramide.

Jurkat (A) or U937 cells (B) were preincubated with 5 μM DMS for 15 minutes and then treated for an additional 5 hours without or with 25 μM C6-ceramide. Cytosolic extracts were subjected to 15% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-cyt c, anti-Smac/DIABLO, and anti-COX II, as described in Figure 1. Caspase-3–like activity in duplicate extracts from Jurkat (C) or U937 cells (D) was measured with the fluorogenic substrate Ac-DEVD-AMC. Results are means of 3 independent experiments.

DMS potentiates cyt c and Smac/DIABLO release and caspase-3 activation induced by ceramide.

Jurkat (A) or U937 cells (B) were preincubated with 5 μM DMS for 15 minutes and then treated for an additional 5 hours without or with 25 μM C6-ceramide. Cytosolic extracts were subjected to 15% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-cyt c, anti-Smac/DIABLO, and anti-COX II, as described in Figure 1. Caspase-3–like activity in duplicate extracts from Jurkat (C) or U937 cells (D) was measured with the fluorogenic substrate Ac-DEVD-AMC. Results are means of 3 independent experiments.

Smac/DIABLO release initiated by staurosporine and DMS is impeded in cells overexpressing Bcl-xL

A wealth of reports indicates that overexpression of Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL can block all apoptosis-specific mitochondrial activities. Both proteins have been shown to inhibit the release of cytc47,48 and AIF49 in a number of experimental systems. We have previously shown that stable overexpression of Bcl-xL could totally repress apoptosis and caspase-3–like activities induced by DMS in Jurkat T cells.25 Thus, we postulated that Bcl-xL-enforced expression would lead to a blockade of apoptogenic factors from mitochondria triggered by DMS. As expected, DMS-induced cytosolic accumulation of cyt c and Smac/DIABLO was completely blocked in Jurkat/Bcl-xL (Figure9A). Moreover, in agreement with our previous study,25 processing of caspase-3 induced by DMS was totally abolished in Bcl-xL–overexpressing cells (Figure 9B). A similar integral inhibitory effect of Bcl-xLwas found in cells treated with staurosporine, a strong inducer of apoptosis believed to act upstream of the mitochondrial level,47 48 in which Bcl-xL totally blocked both cyt c and Smac/DIABLO (Figure 9A) and caspase-3 cleavage (Figure 9B). These data support the notion that DMS sensitizes cells at a point upstream of the mitochondria.

DMS- and staurosporine-induced cyt c and Smac/DIABLO release and caspase-3 processing are blocked in Bcl-xL–overexpressing Jurkat cells.

(A) Cytosolic extracts from Jurkat/neo or Jurkat/Bcl-xLcells treated with 20 μM DMS or 500 nM staurosporine for 5 hours were subjected to 15% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-cytc, anti-Smac/DIABLO, and anti-COX II, as described in Figure1. (B) Proteins from duplicate extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti–caspase-3 antibody. The mobilities of the 32-kd precursor (p32) and proteolytically processed forms (p20 and p17) are indicated. Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments.

DMS- and staurosporine-induced cyt c and Smac/DIABLO release and caspase-3 processing are blocked in Bcl-xL–overexpressing Jurkat cells.

(A) Cytosolic extracts from Jurkat/neo or Jurkat/Bcl-xLcells treated with 20 μM DMS or 500 nM staurosporine for 5 hours were subjected to 15% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-cytc, anti-Smac/DIABLO, and anti-COX II, as described in Figure1. (B) Proteins from duplicate extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti–caspase-3 antibody. The mobilities of the 32-kd precursor (p32) and proteolytically processed forms (p20 and p17) are indicated. Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments.

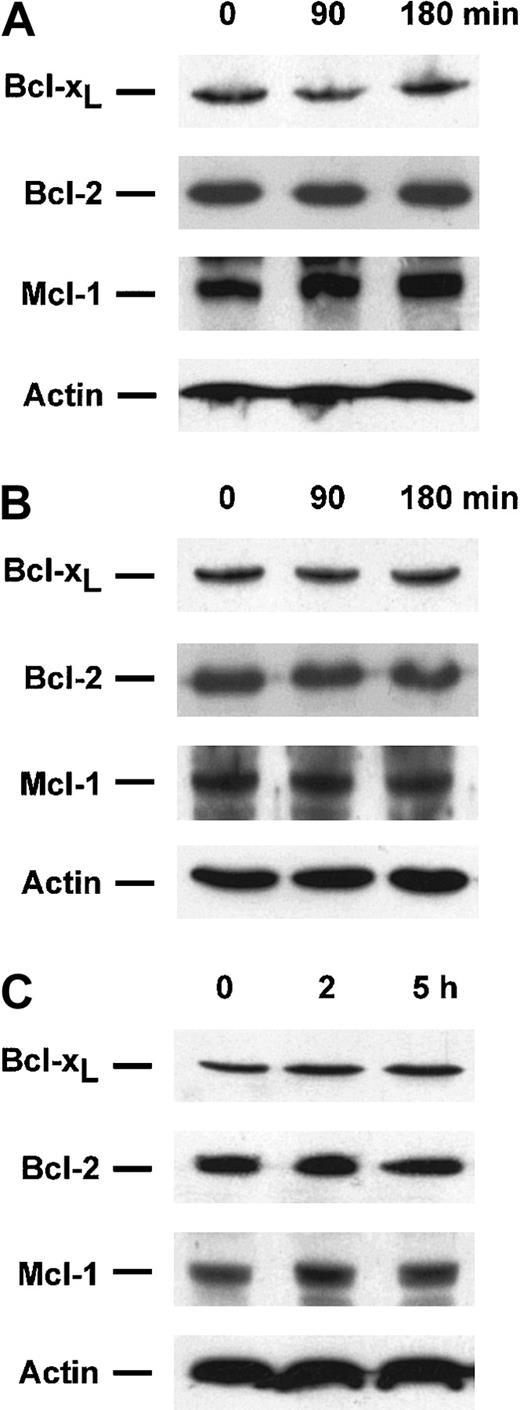

Protective effect of sphingosine 1-phosphate does not appear to involve Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, or Mcl-1

Because both Bcl-xL overexpression and S-1P treatment could inhibit the release of cyt c and Smac/DIABLO from mitochondria, levels of Bcl-2 antiapoptotic family proteins were determined by Western blotting to examine whether S-1P treatment could increase their expression. There were no detectable changes in Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and Mcl-1 protein levels discernible after S-1P treatment in Jurkat (Figure 10A), U937 (Figure 10B), and HL-60 cells (Figure 10C). Similar results were found with an S-1P dose ranging from 0.5 to 5 μM (data not shown). Thus, enhanced expression of these antiapoptotic proteins does not appear to be required for accomplishment of the protective effect of S-1P toward cyt c and Smac/DIABLO release in our systems.

Sphingosine 1-phosphate treatment does not affect Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, or Mcl-1 levels in Jurkat, U937, and HL-60 cells.

Extracts from Jurkat (A), U937 (B), or HL-60 cells (C) treated for the indicated times with 5 μM S-1P were subjected to 15% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-Bcl-2, anti-Bcl-xL, anti-Mcl-1, and actin, as described in Figure 1. Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments.

Sphingosine 1-phosphate treatment does not affect Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, or Mcl-1 levels in Jurkat, U937, and HL-60 cells.

Extracts from Jurkat (A), U937 (B), or HL-60 cells (C) treated for the indicated times with 5 μM S-1P were subjected to 15% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-Bcl-2, anti-Bcl-xL, anti-Mcl-1, and actin, as described in Figure 1. Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments.

Discussion

Within the past few years, the involvement of mitochondria in the control of apoptosis has been well documented (reviewed in Green and Kroemer50 and Desagher and Martinou51). A death-inducing signal propagates to the mitochondria, which release several harmful proteins such as cyt c. Cyt c, the adaptor protein Apaf-1, the precursor procaspase-9, and dATP form the apoptosome death complex (reviewed in Adrain and Martin52). Procaspase-9 is cleaved to form the active enzyme, caspase-9, which activates caspase-3, -6, or -7 in the same way. Two groups15 16 have recently identified a novel mitochondrial factor with a central role in the modulation of apoptosis, Smac/DIABLO, which unblocks one step in the cell death pathway. Smac/DIABLO remains associated with the mitochondrial membrane and is released simultaneously with cyt c. Once released into the cytoplasm, Smac/DIABLO binds to IAPs, allowing caspases at the apoptosome to be activated.

Although our understanding is incomplete, several lines of evidence suggest that mitochondrial dysfunction is required for ceramide-mediated apoptosis. In vitro studies have shown that ceramide itself does not induce nuclear apoptosis unless mitochondria are present.53 In addition, Bcl-2 and Bcl-xLprotect against cell-permeable ceramide-triggered apoptosis,25,27,54-57 caspase-3–caspases activation,25 cyt c release,25,58and AIF release.53 Reports indicate that ceramide can represent an early mediator in Fas- and TNF-α–induced apoptosis preceding mitochondrial events given that overexpression of Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL does impede its early generation in numerous systems such as Jurkat or U937 cells (reviewed in Hannun and Luberto59).

S1-P, a further metabolite of ceramide, prevents apoptosis resulting from ceramide elevation induced by various stress stimuli such as serum withdrawal,1,2,5,6,10 TNF-α,1,8 Fas mAb,1,4 bacterial sphingomyelinase,1,5,6ionizing radiation,9 anticancer drugs,3,9 or exogenous ceramides.1,4,7 The fact that S1-P was capable of counterbalancing the proapoptotic effects mediated by ceramide inspired the concept that a ceramide/S1-P rheostat could regulate apoptosis in the systems in which ceramide was implicated.1

Recently, we have established that S1-P represses the activation of the principal downstream death executioner caspases, caspase-3, -6, and -7, and their substrates caused by anti-Fas or C2-ceramide treatment in Jurkat T lymphocytes.4 Similar findings were observed in human endothelial C11 cells in which S-1P markedly reduced TNF-α–induced caspase-3 activation.8

In this study, we now propose that S1-P likely exerts its inhibitory effect on apoptosis through a mechanism lying upstream of the mitochondrion. Indeed, S1-P cotreatment inhibits the translocation of the mitochondrial key proteins cyt c and Smac/DIABLO to the cytoplasm on the induction of apoptosis by stimulation of the cell surface Fas and TNF-α death receptors, serum deprivation, or addition of exogenous ceramides in human acute leukemia cells. According to the ceramide/S1-P rheostat hypothesis,1 SphK activity stimulation is likely to be involved in clearing the cell of sphingosine and ceramide, both of which have proapoptotic functions,25 thus tilting the balance toward survival. Indeed, SphK stimulation by the phorbol ester TPA resulted in analogous inhibitory effects on stress-induced cyt c and Smac/DIABLO release, thus mimicking S-1P. It should be noted that TPA had a consistently stronger effect than S-1P in inhibiting cyt cand Smac/DIABLO release. This is not surprising because TPA likely has multiple targets in its inhibitory effect besides SphK. On the other hand, it was expected that inhibition of SphK by DMS would lead to an increased release of apoptogenic factors from the mitochondrion. Previously, we demonstrated that DMS can potentiate apoptosis induced by serum withdrawal, ionizing radiation, or bacterial sphingomyelinase treatment in HL-60 or prostate cancer cells1,5,46 because it leads to an increase in sphingosine and ceramide contents.23 Here, the negative regulation of SphK by its competitive inhibitor DMS23 led to an increased release of cyt c and Smac/DIABLO in cells induced to die by TNF-α, Fas mAb, or cell-permeable ceramides. Finally, DMS promotes cytosolic accumulation of cyt c and Smac/DIABLO that is overcome by S-1P cotreatment in all cell lines tested. This is in line with our previous data1,2 5 establishing that S-1P impedes apoptosis resulting from inhibition of the SphK. The notion that DMS sensitizes cells at a point upstream of the mitochondrion was further supported by the fact that Bcl-xL-enforced expression completely prevented mitochondrial release of cyt c and Smac/DIABLO promoted by DMS in Jurkat cells.

Collectively, our results suggest that S1-P likely exerts its inhibitory effect on apoptosis through a mechanism taking place upstream of mitochondria. This effect does appear to involve Bcl-2 antiapoptotic family proteins (Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and Mcl-1) because there were no distinguishable changes in their expression pattern after S-1P treatment. Several recent reports have implied that ceramide could mediate apoptosis by demonstrating negative regulation on the Akt/Bad pathway.60-63 It is unknown whether S-1P is linked to this Akt/Bad pathway; further studies are needed to establish such a molecular link.

We thank Donald Nicholson (Merck-Frosst Centre for Therapeutic Research, Pointe Claire-Dorval, Québec) and Xiadong Wang (Department of Biochemistry, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX) for the generous gift of caspase-3 and Smac/DIABLO antibodies, respectively. We thank Sarah Spiegel (Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, DC) and Robert Salvayre for continuous support, and we thank Stéphane Carpentier for technical assistance.

Supported by Inserm (Unité de Recherche U466, régulations cellulaires–lipidoses et athérosclérose). O.C. is a recipient of the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (Aide au Retour Niveau 2 Grant-in Aid).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Olivier Cuvillier, Inserm U466, CHU Rangueil, 1 avenue Jean Poulhès, 31403 Toulouse Cedex 4, France; e-mail:olivier.cuvillier@rangueil.inserm.fr.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal