In systemic vasculitis, interactions between antineutrophil cytoplasm autoantibodies (ANCAs) and neutrophils initiate endothelial and vascular injury. ANCAs directed against either myeloperoxidase (MPO) or proteinase 3 (PR3) can activate cytokine-primed neutrophils by binding cell surface–expressed MPO or PR3, with the concurrent engagement of Fcγ receptors (FcγR). Because roles for phospholipase D (PLD) and phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K) have been demonstrated in FcγR activation of neutrophils, this study investigated the hypothesis that ANCA stimulation of neutrophils involved a similar engagement of FcγR and activation of PLD and PI3K. Pretreatment of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α-primed neutrophils with antibodies against FcγRII and FcγRIII inhibited MPO-ANCA and PR3-ANCA induced superoxide generation, confirming that FcγR ligation is involved in ANCA-mediated neutrophil activation. However, although stimulation of TNF-α–primed neutrophils by conventional FcγR ligation, either using antibody-mediated cross-linking of FcγR or aggregated IgG, induced PLD activation, ANCA stimulation did not. Moreover, although ANCA-induced neutrophil activation results in significant PI3K activation—as assessed by phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate generation—conventional FcγR ligation, but not ANCA, activates the p85/p110 PI3K subtype. Inhibition of ANCA-induced superoxide generation with pertussis toxin suggests that ANCAs activate the p101/p110γ PI3K isoform. In addition, the kinetics of activation of protein kinase B differs between conventional FcγR ligation and ANCA stimulation of neutrophils. These results demonstrate that though ligation of FcγRIIa and FcγRIIIb may be necessary, it is likely that ANCAs require other membrane cofactors for neutrophil activation.

Introduction

Antineutrophil cytoplasm autoantibodies (ANCAs) directed against azurophilic granule proteins of polymorphonuclear cells are pathogenic in patients with specific forms of systemic vasculitis, namely Wegener granulomatosis, microscopic polyangiitis and Churg-Strauss syndrome.1 Two main types of ANCAs have been described, those directed against proteinase 3 (PR3) and those directed against myeloperoxidase (MPO).2 In vitro, ANCAs can activate cytokine-primed neutrophils, causing an oxidative burst, degranulation, production of interleukin-1β, and damage to endothelial cells.3 Thus, they are implicated in the initiation of the endothelial and vascular damage associated with these vasculitides.4

Priming of neutrophils with cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, as probably occurs in vivo during episodes of infection or inflammatory disease, induces the translocation of target antigens (PR3 and MPO) from the cytoplasm to the extracellular surface, where they are accessible to autoantibody binding.5,6 Binding of the antibodies then triggers signaling events that lead to neutrophil activation. At present, there is much debate as to whether these signaling events are initiated by ANCA Fab binding to MPO or PR37,8 and additionally, or even exclusively, proceed through antibody binding to FcγRIIa and FcγRIIIb receptors.9-11 Although the signaling mechanism(s) by which ANCAs stimulate neutrophils have not been fully elucidated, we have recently demonstrated the involvement of tyrosine kinases and protein kinase C in ANCA-mediated neutrophil activation.12

Freshly isolated human neutrophils express 2 forms of Fcγ receptors (FcγR), the glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked FcγRIIIb (CD16) and FcγRIIa (CD32), a conventional type I transmembrane protein of 40 kd.13,14 Cross-linking of these receptors in vitro, either by using aggregates of immunoglobulin (Ig) G as immune complexes or specific monoclonal antibodies, results in the activation of neutrophil phagocytosis, degranulation, and respiratory burst.15-17Although the signaling events have not yet been fully unraveled, signaling through FcγRIIa and FcγRIIIb, either independently or in combination, is accompanied by the activation of phospholipase C (PLC) by a tyrosine kinase-dependent, G-protein–independent mechanism18 and a rise in intracellular calcium level.15,16 It has also been reported that cross-linking of FcγR induces the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K)19 and the recruitment of the serine–threonine kinase protein kinase B (PKB), a major downstream target of PI3K.20 Moreover, a recent study demonstrated a role for phospholipase D (PLD) in immune complex–induced FcγR activation of neutrophils.21 Thus, the signaling mechanisms induced by ANCAs and FcγR activation in neutrophils show many similarities, suggesting that ANCA signaling proceeds through Fcγ receptor ligation.

Other neutrophil activators that induce superoxide release—such as the chemoattractant formyl-methionyleucylphenylalanine (fMLP)—activate several intracellular phospholipid signaling pathways including phospholipase A2, PLC, PI3K, and PLD after ligation of surface receptors.22 PLD catalyzes the hydrolysis of phosphatidylcholine to phosphatidate (PtdOH) and choline. PtdOH can then be converted to diacylglycerol (DAG), a potent second messenger in a variety of cell signaling processes, though recent studies have suggested that PtdOH may play a more important role than DAG in the activation of the NADPH oxidase system and subsequent oxidative burst.23

Two types of PI3K enzymes have been described in neutrophils, a class IA form consisting of a p110 catalytic subunit and a p85 regulatory subunit that binds phosphorylated tyrosine residues and a class IB form, PI3K γ, consisting of a p110γ catalytic subunit and a p101 regulatory subunit stimulated by G-protein βγ subunits and also by ras.24 These enzymes catalyze the 3-phosphorylation of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3). PIP3 is a potent second messenger25 and is thought to play an important role in the activation of the neutrophil NADPH oxidase system26,27 and in Fcγ receptor-mediated phagocytosis.18

The aim of this study was, therefore, to determine the Fcγ receptor requirements for ANCAs and subsequently to investigate the roles of PLD and PI3K in ANCA-induced neutrophil activation and superoxide production, comparing these results with conventional FcγR ligation (using either monoclonal antibody–mediated FcγR cross-linking or aggregated IgG) and fMLP activation of neutrophils. Detailed understanding of ANCA-induced neutrophil signaling may ultimately provide targets for therapeutic intervention and control of neutrophil-mediated acute severe vasculitis.

Materials and methods

Isolation of neutrophils

Blood was obtained from healthy volunteers, and neutrophils were separated as previously described using centrifugation over a Percoll discontinuous density gradient.28

Preparation of ANCAs and normal IgG

Serum samples were obtained from 3 MPO-ANCA–positive patients, 3 PR3-ANCA–positive patients, and 2 healthy volunteers. IgG was prepared from these serum samples using selection on protein G–Sepharose columns (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, St Albans, United Kingdom) with endotoxin-free materials. The protein content of these samples was estimated, and these samples were then used at either 200 or 250 μg/mL in subsequent assays. In previous studies, both these concentrations of ANCA, but not normal, IgG have been shown to induce substantial superoxide generation in 105 neutrophils (200 μg/mL) or 4 × 106 neutrophils (250 μg/mL), respectively, following dose-response analyses (data not shown). IgG samples were free of endotoxin contamination, as assessed by a Limulus amebocyte assay (Sigma, Poole, United Kingdom). All assays were made in the absence of serum to avoid endotoxin-induced binding and activation and at equivalent cell densities in either polystyrene microtiter plates or polystyrene sample tubes to ensure identical conditions for cell adhesion.

Generation of aggregated IgG

IgG samples from 3 MPO-ANCA–positive patients, 3 PR3-ANCA–positive patients, and 2 healthy volunteers were resuspended at a concentration of 20 mg/mL in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and heated to 63°C for 20 minutes as previously described.29

Superoxide assay

Freshly isolated neutrophils were resuspended at a concentration of either 5 × 105 or 107 cells/mL in 10 mM Hepes-buffered Hanks balanced salt solution (HBH) and primed with 2 ng/mL TNF-α for 15 minutes at 37°C. Aliquots of 105cells (in microtiter plates) or 4 × 106 cells (in sample tubes) were then stimulated either with 1 μM fMLP (Sigma), 50-250 μg/mL MPO-ANCA, PR3-ANCA, normal IgG, or heat-aggregated IgG samples. Superoxide release was measured over 15 minutes using an assay based on the superoxide dismutase inhibitable reduction of ferricytochrome c and performed as described previously.30 In some experiments, wortmannin (Sigma) or LY294002 (Sigma) was added to the primed neutrophil samples, and the cells were equilibrated for 5 to 10 minutes before stimulation.

Pertussis toxin treatment was performed by treating freshly isolated neutrophils, at a concentration of 107 cells/mL, with pertussis toxin (Calbiochem-Novabiochem, Nottingham, United Kingdom) or vehicle (100 mM NaPO4, 50 mM NaCl, pH 7) for 2 hours at 37°C. The cells were diluted to 5 × 105 cells/mL and primed with 2 ng/mL TNF-α for 15 minutes at 37°C before stimulation.

For the assessment of superoxide production in FcγR cross-linked neutrophils, 5 × 105/mL cells were primed with 2 ng/mL TNF-α for 15 minutes at 37°C and incubated with either 1 μg/mL IV.3 Fab (recognizing FcγRII), 1 μg/mL 3G8 F(ab′)2(recognizing FcγRIII) (Medarex, Annandale, NJ), or both. Monoclonal antibodies were removed by centrifugation, and cells were resuspended in HBH containing 2 ng/mL TNF-α. Cross-linking was achieved by treating the cells with 10 μg/mL F(ab′)2 fragments of goat anti–mouse Fab (GAM F(ab′)2; Sigma). Superoxide release was then measured over 15 minutes. Optimal concentrations of IV.3, 3G8, and GAM F(ab′)2 antibodies had been previously determined from dose-response analyses.

To examine anti-FcγR monoclonal antibody blocking of ANCA superoxide production, 5 × 105/mL primed neutrophils were treated with either 1 μg/mL IV.3 Fab (anti-FcγRII), 1 μg/mL 3G8 F(ab′)2 (anti-FcγRIII), or both. Aliquots of 105 cells were then stimulated with 200 μg/mL MPO-ANCA, PR3-ANCA IgG, or 200 μg/mL normal IgG, and superoxide release was measured over 15 minutes. All samples were tested as 6 replicates, and all the experiments were repeated 3 times.

PLD assays

Two methods were used to assess the involvement of PLD signaling pathways in anti-FcγR, fMLP, and ANCA-stimulated neutrophils.

Assessment of phosphatidylbutanol formation.

Freshly isolated neutrophils were resuspended at a concentration of 2 × 107/mL in 25 mM Hepes buffer containing 125 mM NaCl, 10 mM glucose, 1 mM EGTA, and 1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA). The cells were labeled with 37 kBq/mL 1-O-[3H]-alkyl-sn-glyceryl-3-phosphorylcholine (NEN, Hounslow, United Kingdom) for 30 minutes at 37°C, washed, and resuspended in HBH. Butan-1-ol (0.3%) was added to aliquots of 4 × 106 cells, which were then primed with 2 ng/mL TNF-α for 15 minutes at 37°C and stimulated with 1 μM fMLP, 50-250 μg/mL MPO-ANCA, PR3-ANCA, normal IgG, or heat-aggregated IgG samples or by cross-linking FcγR1 μg/mL IV.3 Fab, 1 μg/mL 3G8 F(ab′)2, or both for 5 minutes followed by 10 μg/mL GAM F(ab′)2. The reaction was stopped by the addition of chloroform and methanol (1:2), the lipids were separated, and levels of [3H]phosphatidylbutanol were assessed as previously described.31 All samples were tested in triplicate, and the results were expressed as percentage dpm pbut (percentage [3H] incorporation in phosphatidylbutanol fraction/[3H] incorporation in total lipids measured). All experiments were repeated 3 times.

Determination of PtdOH and DAG generation.

Levels of PtdOH and DAG were assessed after fMLP and ANCA stimulation of neutrophils. Cells were labeled with 37 kBq/mL 1-O-[3H]-alkyl-sn-glyceryl-3-phosphorylcholine, primed with 2 ng/mL TNF-α, and stimulated as before. Levels of PtdOH and DAG were then measured as described.31 All samples were tested in triplicate, and the results were expressed as either % dpm PtdOH or % dpm DAG, (ie, percentage [3H] incorporation in PtdOH or DAG fraction/[3H] incorporation in total lipids measured).

Measurement of PIP3 generation.

Freshly isolated neutrophils were resuspended at a concentration of 5 × 107/mL in HBH containing 0.1% fatty acid-free BSA (Sigma). The cells were labeled with 74 MBq/mL [32P]orthophosphate (Amersham Life Science, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) for 70 minutes at 37°C, washed twice, and resuspended in HBH-BSA. Aliquots of 2 × 107 cells (400 μL) were then primed with 2 ng/mL TNF-α for 15 minutes at 37°C and were stimulated with either 1 μM fMLP, 250 μg/mL MPO-ANCA, PR3-ANCA, or normal IgG. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 1.5 mL ice-cold chloroform and methanol 1:2, and the lipids were extracted, diacetylated, and separated by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as previously described.32As an internal standard, the HPLC runs were spiked with [3H]GroPInsPns (including [3H]GroPInsP3) derived from [3H]inositol-radiolabeled yeast inducibly expressing a farnesylated p110 subunit.33 All samples were tested in duplicate, and the experiment were repeated twice.

Assessment of PKB activation.

Freshly isolated neutrophils at a concentration of 2 × 107/mL in HBH were primed with TNF-α and stimulated with 1 μM fMLP, 250 μg/mL MPO-ANCA, PR3-ANCA, and normal IgG or by FcγR cross-linking 1 μg/mL IV.3 Fab or 1 μg/mL 3G8 F(ab′)2 (or both) followed by 10 μg/mL GAM F(ab′)2. The reaction was stopped with the addition of 4 × ice-cold PBS. Cells were then lysed in 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.2), 2.5 mM EGTA, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM NaCl, and 5 mM MgCl2 containing 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 40 μg/mL leupeptin, 40 μg/mL aprotinin, 2 mM sodium orthovanadate, 50 mM sodium fluoride, and 40 mM sodium pyrophosphate (lysis buffer). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation, and their protein content was assessed using the Bio-Rad method (Bio-Rad, Hemel Hempstead, United Kingdom).

Levels of PKB and phospho-PKB in anti-PKB immunoprecipitates prepared from the lysates were assessed as follows: 100 μg protein was incubated with 5 μL anti-PKB antibody (rabbit polyclonal Akt antibody; New England BioLabs, Hitchin, United Kingdom) overnight at 4°C. An aliquot of 65 μL Protein G–Sepharose (Sigma) was then added to the lysates for 2 hours at 4°C. The immunoprecipitate was washed at 4°C with 2 × 1 mL lysis buffer, 1 × 1 mL 0.5 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 1 × 1 mL 0.5 M LiCl, 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8, and 2 × 1 mL lysis buffer. Samples were resuspended in 30 μL 2 × sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) loading buffer, heated to 100°C for 5 minutes, subjected to electrophoresis in 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and transferred to nitrocellulose. Immunodetection of PKB or phospho-PKB was performed using either the PKB antibody or a phospho-PKB antibody (rabbit polyclonal phospho-Akt antibody; New England Bio-Labs) followed by an antirabbit peroxidase-linked secondary antibody (Amersham Life Science) as described in the data sheets and as visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham). Experiments were repeated 3 times using lysates prepared on separate occasions with MPO-ANCA or PR3-ANCA IgG samples from different patients.

Assessment of PI3K activity.

PI3K activity in anti-p85α immunoprecipitates prepared from 100 μg TNF-α–primed, unstimulated, and stimulated (with 1 μM fMLP, 50-250 μg/mL MPO-ANCA, PR3-ANCA, normal IgG, heat-aggregated IgG, or by cross-linking FcγR (1 μg/mL IV.3 Fab or 1 μg/mL 3G8 F(ab′)2 for 5 minutes followed by 10 μg/mL GAM F(ab′)2) neutrophil lysates was assessed essentially as previously described34 using 1.5 mg/mL propidium iodide (Sigma) in 0.5% cholate as substrate. After separation of the lipids by thin-layer chromatography, PtdIns(3)P levels were quantified using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Chesham, United Kingdom). All samples were tested in duplicate, and all experiments were repeated at least 3 times.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as means ± SEM. For each data set, results from all the replicate experiments were pooled. Statistical significance was evaluated using analysis of variance (Minitab v.13.1; Minitab, State College, PA) to assess whether there was a significant overall effect of treatment and time. If significant effects were found, individual analyses were also performed using Tukey-Kramner multiple comparison tests (Minitab), with these results presented as probability values (P). P ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Superoxide production in fMLP-, ANCA-, and anti-FcγR– stimulated neutrophils

ANCA stimulation of TNF-α–primed neutrophils has previously been reported to induce superoxide production.10 12 Our results, shown in Figure 1, confirmed that stimulation of such neutrophils with fMLP, MPO-ANCA, PR3-ANCA IgG, or conventional FcγR engagement (using either cross-linking anti-FcγR antibodies or heat-aggregated IgG) lead to significant superoxide production.

Superoxide production in neutrophils stimulated with fMLP or ANCA IgG or by conventional FcγR ligation using either cross-linking antibodies or aggregated IgG.

Superoxide production in 105 neutrophils primed with 2 ng/mL TNF-α and stimulated with (A) 1 μM fMLP, 200 μg/mL MPO-ANCA IgG, 200 μg/mL PR3-ANCA IgG, or 200 μg/mL normal IgG, or with (B) primed, unstimulated cells or cells stimulated with 1 μg/mL IV.3 (FcRII XL), 1 μg/mL 3G8 (FcRIII XL), or both monoclonal antibodies (FcRII+III XL), followed by cross-linking with 10 μg/mL GAM F(ab′)2, or with (C) primed, unstimulated cells or cells stimulated with either 1 μM fMLP, 200 μg/mL normal IgG, or 200 μg/mL heat-aggregated IgG for 1 (■), 5 (░), or 15 (▨) minutes. (Note different scales in the 3 panels.) All experiments were repeated 3 times using neutrophils from different donors, 3 different MPO-ANCA and PR3-ANCA IgG preparations, and 2 different normal IgG samples (native and heat-aggregated) and 6 replicates of all samples. Results show mean ± SEM of data pooled from all 3 experiments.

Superoxide production in neutrophils stimulated with fMLP or ANCA IgG or by conventional FcγR ligation using either cross-linking antibodies or aggregated IgG.

Superoxide production in 105 neutrophils primed with 2 ng/mL TNF-α and stimulated with (A) 1 μM fMLP, 200 μg/mL MPO-ANCA IgG, 200 μg/mL PR3-ANCA IgG, or 200 μg/mL normal IgG, or with (B) primed, unstimulated cells or cells stimulated with 1 μg/mL IV.3 (FcRII XL), 1 μg/mL 3G8 (FcRIII XL), or both monoclonal antibodies (FcRII+III XL), followed by cross-linking with 10 μg/mL GAM F(ab′)2, or with (C) primed, unstimulated cells or cells stimulated with either 1 μM fMLP, 200 μg/mL normal IgG, or 200 μg/mL heat-aggregated IgG for 1 (■), 5 (░), or 15 (▨) minutes. (Note different scales in the 3 panels.) All experiments were repeated 3 times using neutrophils from different donors, 3 different MPO-ANCA and PR3-ANCA IgG preparations, and 2 different normal IgG samples (native and heat-aggregated) and 6 replicates of all samples. Results show mean ± SEM of data pooled from all 3 experiments.

After stimulation with fMLP, superoxide production was evident after 1 minute and significantly increased after 5 minutes (Figure 1A). By contrast, stimulation with 3 different MPO-ANCA or PR3-ANCA samples consistently produced lower initial levels of superoxide (0-1 nmol at 1 to 5 minutes), which then increased over 15 minutes. Stimulation with equivalent amounts of normal IgG produced significantly lower levels of superoxide than seen with any of the ANCA IgG samples (Figure 1A; normal IgG, 0.61 ± 0.07 nmol at 15 minutes, P < .05).

Conventional FcγR engagement of TNF-α–primed neutrophils, either using anti-FcγR cross-linking antibodies or aggregated IgG, also led to significant stimulation of superoxide production over the course of the assay (Figure 1B-C). Incubation of primed neutrophils with either IV.3 Fab (FcRII XL) or 3G8 F(ab′)2 (FcRIII XL), followed by cross-linking with GAM F(ab′)2, led to initial low levels of superoxide production after 1-minute stimulation (less than 0.3 nmol), which further increased over 15 minutes to 1.2 to 1.5 nmol (P < .001). Stimulation of primed neutrophils with cross-linked IV.3 Fab and 3G8 F(ab′)2 antibodies together (FcRII+III XL) led to a faster and greater superoxide burst, with levels of 1.09 ± 0.12 nmol at 5 minutes (P ≤ .001; Figure 1B). Stimulation of neutrophils with the monoclonal antibodies only or the GAM cross-linking antibody alone produced significantly lower levels of superoxide over the assay period (maximum, 15-minutes values: IV.3 Fab 0.47 ± 0.11 nmol superoxide; 3G8 F(ab′)2 0.43 ± 0.17 nmol superoxide; GAM F(ab′)2 0.52 ± 0.13 nmol superoxide;P < .05). Use of 200 μg/mL heat-aggregated normal IgG resulted in significant superoxide generation after 1 minute compared with nonaggregated normal IgG, with levels increasing to 2.6 ± 0.27 nmol after 15 minutes (P < .001; Figure 1C). Even at lower concentrations of heat-aggregated normal IgG (50-100 μg/mL), significant superoxide was evident after 1-minute stimulation (eg, stimulation with 50 and 100 μg/mL led to levels of 0.61 ± 0.05 and 0.67 ± 0.19 nmol, respectively, compared to 0 ± 0.14 and 0 ± 0.2 nmol, respectively, in nonaggregated IgG samples;P < .01). Stimulation of primed neutrophils with 200 μg/mL aggregated MPO-ANCA or PR3-ANCA IgG also led to increased superoxide generation, with levels of 1.5 to 3 nmol (aggregated ANCA IgG) compared with 1.3 to 1.9 nmol superoxide (native ANCA IgG) after 15 minutes (P < .05).

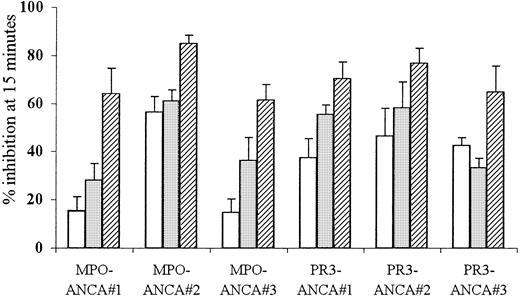

Anti-FcγR monoclonal antibody pretreatment blocks ANCA-induced superoxide production in primed neutrophils

To clarify the role for FcγR in ANCA-mediated neutrophil activation, TNF-α–primed neutrophils were pretreated with either IV.3 Fab (anti-FcγRII) or 3G8 F(ab′)2 (anti-FcγRIII) monoclonal antibodies before stimulation with ANCA. Used individually, either antibody reduced superoxide production by 15% to 61% in response to stimulation with 3 different MPO-ANCA and PR3-ANCA samples (P ≤ .001). Pretreatment of neutrophils with both anti-FcγR antibodies together resulted in even greater inhibition (46%-85%) of the superoxide response to all the MPO-and PR3-ANCA samples (P < .001). These results, shown in Figure2, confirmed a role for both FcγRIIa and FcγRIIIb in ANCA-mediated neutrophil activation.

Effect of FcγR blocking on ANCA IgG superoxide response.

Aliquots of 105 neutrophils were primed with 2 ng/mL TNF-α and pretreated with either 1 μg/mL IV.3 (anti-FcRII, ■), 1 μg/mL 3G8 (anti-FcRIII, ░), or both monoclonal antibodies (anti-FcRII+III, ▨) before stimulation with 200 μg/mL MPO-ANCA or PR3-ANCA IgG for 15 minutes. All experiments were repeated 3 times using neutrophils from different donors, 3 different MPO-ANCA and PR3-ANCA preparations, and 6 replicates of all samples. Results show mean ± SEM of data pooled from all 3 experiments.

Effect of FcγR blocking on ANCA IgG superoxide response.

Aliquots of 105 neutrophils were primed with 2 ng/mL TNF-α and pretreated with either 1 μg/mL IV.3 (anti-FcRII, ■), 1 μg/mL 3G8 (anti-FcRIII, ░), or both monoclonal antibodies (anti-FcRII+III, ▨) before stimulation with 200 μg/mL MPO-ANCA or PR3-ANCA IgG for 15 minutes. All experiments were repeated 3 times using neutrophils from different donors, 3 different MPO-ANCA and PR3-ANCA preparations, and 6 replicates of all samples. Results show mean ± SEM of data pooled from all 3 experiments.

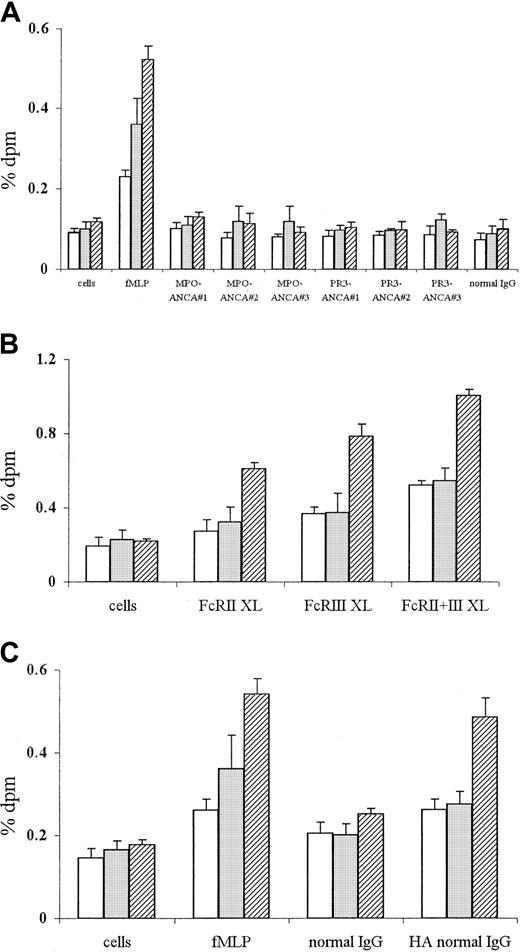

ANCA stimulation fails to activate PLD, as measured by either phosphatidylbutanol or lipid messenger production

Signal transduction pathways activated by ANCAs were compared with those activated by conventional FcγR ligation (using either anti-FcγR cross-linking antibodies or aggregated IgG) and fMLP stimulation. PLD activation was measured using an accumulating trap assay for the detection of both small and slowly accumulating levels of PLD products. This assay has been fully described elsewhere,30 is well validated, and is definitive for cellular PLD activation. fMLP stimulation led to rapid and significant PLD activation of TNF-α–primed neutrophils, with [3H] incorporation in phosphatidylbutanol fraction at 0.23% ± 0.02% after 1 minute (P < .001) and remaining elevated throughout the assay period (0.52% ± 0.03% at 15 minutes,P < .001) (Figure 3A). By contrast, stimulation with 3 different MPO-ANCA or PR3-ANCA preparations or with normal IgG did not result in any PLD activation above background levels (primed, unstimulated cells) or indeed for 100 minutes (data not shown) during the time-course of the assay (Figure 3A), in spite of significant superoxide production (as shown in Figure 1A).

PLD activation in neutrophils stimulated with fMLP or ANCA IgG or by conventional FcγR ligation using either cross-linking antibodies or aggregated IgG.

Phosphatidylbutanol production in 4 × 106 neutrophils primed with 2 ng/mL TNF-α and stimulated with (A) 1 μM fMLP, 250 μg/mL MPO-ANCA, PR3-ANCA, or normal IgG, or with (B) primed, unstimulated cells, or cells stimulated with 1 μg/mL IV.3 (FcRII XL), 1 μg/mL 3G8 (FcRIII XL), or both monoclonal antibodies (FcRII+III XL), followed by cross-linking with 10 μg/mL GAM F(ab′)2, or with (C) primed, unstimulated cells or cells stimulated with either 1 μM fMLP, 250 μg/mL normal IgG, or 250 μg/mL heat-aggregated IgG for 1 (■), 5 (░), or 15 (▨) minutes. All experiments were repeated 3 times using neutrophils from different donors, 3 different MPO-ANCA and PR3-ANCA IgG preparations, and 2 different normal IgG samples (native and heat-aggregated) and triplicates of all samples. Results show mean ± SEM of data pooled from all 3 experiments.

PLD activation in neutrophils stimulated with fMLP or ANCA IgG or by conventional FcγR ligation using either cross-linking antibodies or aggregated IgG.

Phosphatidylbutanol production in 4 × 106 neutrophils primed with 2 ng/mL TNF-α and stimulated with (A) 1 μM fMLP, 250 μg/mL MPO-ANCA, PR3-ANCA, or normal IgG, or with (B) primed, unstimulated cells, or cells stimulated with 1 μg/mL IV.3 (FcRII XL), 1 μg/mL 3G8 (FcRIII XL), or both monoclonal antibodies (FcRII+III XL), followed by cross-linking with 10 μg/mL GAM F(ab′)2, or with (C) primed, unstimulated cells or cells stimulated with either 1 μM fMLP, 250 μg/mL normal IgG, or 250 μg/mL heat-aggregated IgG for 1 (■), 5 (░), or 15 (▨) minutes. All experiments were repeated 3 times using neutrophils from different donors, 3 different MPO-ANCA and PR3-ANCA IgG preparations, and 2 different normal IgG samples (native and heat-aggregated) and triplicates of all samples. Results show mean ± SEM of data pooled from all 3 experiments.

To confirm PLD activation of neutrophils by fMLP stimulation, PtdOH and DAG levels were measured. Stimulation of neutrophils with 1 μM fMLP for 15 minutes led to an initial rise in PLD-induced PtdOH after 5 minutes ([3H] incorporation in PtdOH fraction, 0.712% ± 0.018%, P < .001) and a subsequent increase in DAG levels ([3H] incorporation in DAG fraction at 10 minutes, 2.001% ± 0.152%, P < .001). By contrast, stimulation with either 250 μg/mL MPO-ANCA, PR3-ANCA, or normal IgG did not result in significant PLD-induced PtdOH or DAG production over the same time.

FcγR ligation using anti-FcγR cross-linking antibodies or aggregated IgG stimulates PLD activation in primed neutrophils

In contrast to the lack of PLD activation after ANCA stimulation, cross-linking of either FcγRIIa (FcRII XL) or FcγRIIIb (FcRIII XL) activated PLD (Figure 3B), with levels of 0.61% ± 0.03% (FcRII XL), P ≤ .001) and 0.79% ± 0.06% [3H]pbut incorporation (FcRIII XL),P ≤ .001) at 15 minutes. Cross-linking of both FcγR (FcRII+III XL) led to an increase in PLD activation, with levels of 0.52% ± 0.02% [3H]pbut incorporation at 1 minute (P < .001), increasing to 1.00% ± 0.03% after 15 minutes (P < .001, Figure 3B). Stimulation of neutrophils with monoclonal antibodies only or GAM cross-linking antibody alone did not lead to significant PLD activation at any time.

Ligation of FcγR with 50 to 250 μg/mL heat-aggregated IgG also induced significant PLD activity. Use of 250 μg/mL aggregated normal IgG resulted in increased levels of PLD activity after 1 minute (0.26% ± 0.03% [3H]pbut incorporation) in contrast to nonaggregated normal IgG (0.20% ± 0.03% [3H]pbut incorporation), with significantly elevated levels at 15 minutes (aggregated IgG, 0.49% ± 0.05% [3H]pbut incorporation compared to nonaggregated IgG, 0.25% ± 0.01% [3H]pbut incorporation;P < .001) (Figure 3C). Even at lower concentrations (50-100 μg/mL), aggregated normal IgG was able to induce significant PLD activity (eg, stimulation with 50 and 100 μg/mL aggregated IgG for 5 minutes resulted in 0.24% ± 0.01 and 0.26% ± 0.02% [3H]pbut incorporation, respectively, compared to 0.18% ± 0.02% and 0.19% ± .02%, respectively, in nonaggregated IgG samples; P < .05). Aggregation of both PR3-ANCA and MPO-ANCA IgG also led to significant PLD activation within 1 minute of stimulation, with levels of 0.24% to 0.26% [3H]pbut incorporation (aggregated ANCA IgG) compared with 0.18% to 0.19% [3H]pbut incorporation (native ANCA IgG, P < .05).

fMLP-, ANCA-, and anti-FcγR–induced superoxide production can be blocked by PI3K inhibitors

Superoxide production by TNF-α–primed neutrophils stimulated with fMLP, ANCA IgG, or antibody-mediated FcγR cross-linking was inhibited by pretreatment with LY294002 (Figure4). Use of this compound led to dose-dependent inhibition of the fMLP-induced superoxide response at concentrations of 0.5 to 50 μM (Figure 4A) and significant inhibition of ANCA IgG-induced superoxide responses (Figure 4A; fMLP response at 5 μM, 23% ± 1.0% inhibition, P < .005; ANCA response at 0.5 μM, 81%-95% inhibition,P ≤ .01). Pretreatment of neutrophils with LY294002 also significantly suppressed superoxide production in antibody-mediated FcγR cross-linked neutrophils (Figure 4B). There was 70% to 100% inhibition of anti-FcγRII (FcRII XL) and anti-FcγRIII (FcRIII XL)-induced responses (P ≤ .05) and 37% inhibition of FcRII+III XL responses at 0.5 μM concentrations (P < .01) (Figure 4B). These data suggested that neutrophil stimulation by fMLP, ANCA, and FcγR cross-linking recruited PI3K because the IC50 for inhibition of PI3K by LY294002 is 1.4 μM.35

Effect of LY294002 on fMLP, ANCA, and anti-FcγR superoxide production.

Aliquots of 105 neutrophils were primed with 2 ng/mL TNF-α and treated with 0.5 (■), 5 (░), 10 (▨), or 50 μM LY294002 (▥) before stimulation with (A) 1 μM fMLP, 200 μg/mL MPO-ANCA, or PR3-ANCA IgG or (B) 1 μg/mL IV.3 (FcRII XL), 1 μg/mL 3G8 (FcRIII XL), or 1 μg/mL of both anti-FcγR monoclonal antibodies (FcRII+III XL) followed by 10 μg/mL GAM F(ab′)2cross-linking antibody for 15 minutes. All experiments were repeated 3 times, with 6 replicates of all samples. Results are shown as mean percentage inhibition of superoxide production ± SEM of data pooled from all 3 experiments.

Effect of LY294002 on fMLP, ANCA, and anti-FcγR superoxide production.

Aliquots of 105 neutrophils were primed with 2 ng/mL TNF-α and treated with 0.5 (■), 5 (░), 10 (▨), or 50 μM LY294002 (▥) before stimulation with (A) 1 μM fMLP, 200 μg/mL MPO-ANCA, or PR3-ANCA IgG or (B) 1 μg/mL IV.3 (FcRII XL), 1 μg/mL 3G8 (FcRIII XL), or 1 μg/mL of both anti-FcγR monoclonal antibodies (FcRII+III XL) followed by 10 μg/mL GAM F(ab′)2cross-linking antibody for 15 minutes. All experiments were repeated 3 times, with 6 replicates of all samples. Results are shown as mean percentage inhibition of superoxide production ± SEM of data pooled from all 3 experiments.

Use of another PI3K inhibitor, wortmannin, which selectively inhibits PI3K activity at concentrations of 5 to 10 nM,27 confirmed these observations. Pretreatment with wortmannin led to significant inhibition of both fMLP and ANCA IgG-induced superoxide responses at concentrations of 2 to 25 nM (fMLP response at 5 nM, 56% ± 9.9% inhibition, P < .001; ANCA response at 5 nM, 56%-62% inhibition, P ≤ .001). Pretreatment of neutrophils with wortmannin also significantly suppressed superoxide production in neutrophils stimulated by FcγR cross-linking, with 48% to 56% inhibition of anti-FcγRII (FcRII XL) and anti-FcγRIII (FcRIII XL) responses (P ≤ .05) and 64% inhibition of anti-FcγRII+FcγRIII-induced responses at 5 nM concentration (P < .03).

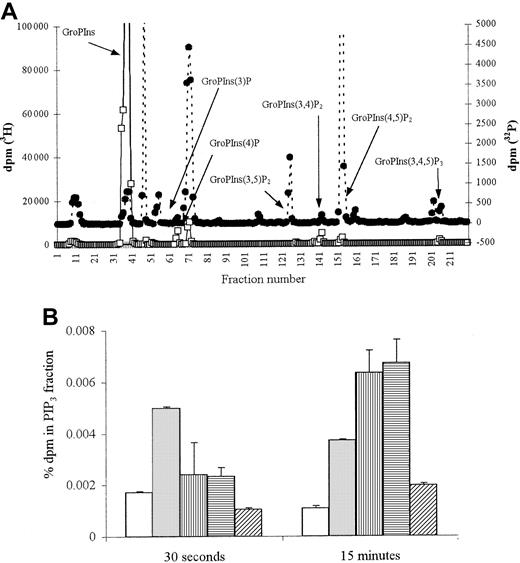

ANCA stimulation results in PIP3 formation

To confirm the activation of PI3K, levels of its product, PIP3, were measured. Stimulation of TNF-α–primed neutrophils with fMLP led to significant PIP3 generation at 30 seconds (Figure 5A), with a 3-fold increase above background levels maintained over 15 minutes (Figure 5B;P < .03). Stimulation with both MPO- and PR3-ANCA also resulted in PIP3 generation, but the initial response was slower, with significantly greater levels (6-fold increase,P < .01) seen after 15 minutes of stimulation (Figure 5B).

PIP3 production in fMLP and ANCA-stimulated neutrophils.

2 × 107 neutrophils were primed with 2 ng/mL TNF-α and stimulated either with 1 μM fMLP, 250 μg/mL MPO-ANCA, 250 μg/mL PR3-ANCA, or 250 μg/mL normal and PIP3 production measured. (A) Representative HPLC trace showing inositol phosphates derived from 30-second fMLP-stimulated 32P-labeled neutrophils (●) superimposed on trace 3H internal standards (■). (B) Graph showing percentage dpm in 32P PIP3 fraction after 30-second and 15-minute stimulation. All samples were tested in duplicate, and results show pooled data from 2 experiments. ■ indicates cells; ░, fMLP; ▥, MPO-ANCA; ▤, PR3-ANCA; ▨, normal IgG.

PIP3 production in fMLP and ANCA-stimulated neutrophils.

2 × 107 neutrophils were primed with 2 ng/mL TNF-α and stimulated either with 1 μM fMLP, 250 μg/mL MPO-ANCA, 250 μg/mL PR3-ANCA, or 250 μg/mL normal and PIP3 production measured. (A) Representative HPLC trace showing inositol phosphates derived from 30-second fMLP-stimulated 32P-labeled neutrophils (●) superimposed on trace 3H internal standards (■). (B) Graph showing percentage dpm in 32P PIP3 fraction after 30-second and 15-minute stimulation. All samples were tested in duplicate, and results show pooled data from 2 experiments. ■ indicates cells; ░, fMLP; ▥, MPO-ANCA; ▤, PR3-ANCA; ▨, normal IgG.

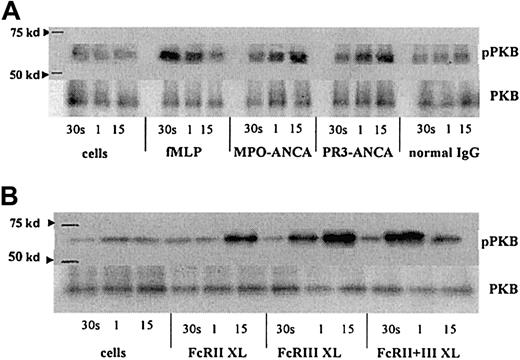

fMLP, ANCA, and FcγR cross-linking activate protein kinase B

Protein kinase B (PKB) is a downstream target following PI3K activation. Stimulation of TNF-α–primed neutrophils with fMLP, MPO-ANCA, and PR3-ANCA and by cross-linking FcγR each led to an increase in phospho-PKB levels. However, the kinetics differed with each stimulus, with fMLP stimulation giving the earliest detectable activation of PKB, at 30 seconds, with levels returning to background by 15 minutes (Figure 6A). Activation of PKB occurred later, after ANCA stimulation, with increased phosphorylation detectable after 1 minute and sustained at 15 minutes (Figure 6A). Cross-linking of either FcγRIIa or FcγRIIIb individually gave significant phosphorylation of PKB at 1 minute (FcγRIIIb) and 15 minutes (FcγRIIa), whereas cross-linking of both receptors resulted in a greater, but more transient, increase in phospho-PKB (Figure 6B).

PKB activation in fMLP, ANCA, and FcγR cross-linked neutrophils.

Phospho-PKB (pPKB) levels were assessed in blots of PKB immunoprecipitates from primed neutrophils stimulated with either (A) 1 μM fMLP, 250 μg/mL MPO-ANCA, PR3-ANCA, or normal IgG or (B) 1 μg/mL anti-FcγRII, 1 μg/mL anti-FcγRIII, or 1 μg/mL of both anti-FcγR monoclonal antibodies followed by 10 μg/mL GAM F(ab′)2 cross-linking antibody for 30 seconds, 1 minute, and 15 minutes. Molecular weight (kd), as assessed using Rainbow markers (Amersham), are shown on the left. Levels of PKB are also shown to indicate equal amounts of protein within the samples. These results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

PKB activation in fMLP, ANCA, and FcγR cross-linked neutrophils.

Phospho-PKB (pPKB) levels were assessed in blots of PKB immunoprecipitates from primed neutrophils stimulated with either (A) 1 μM fMLP, 250 μg/mL MPO-ANCA, PR3-ANCA, or normal IgG or (B) 1 μg/mL anti-FcγRII, 1 μg/mL anti-FcγRIII, or 1 μg/mL of both anti-FcγR monoclonal antibodies followed by 10 μg/mL GAM F(ab′)2 cross-linking antibody for 30 seconds, 1 minute, and 15 minutes. Molecular weight (kd), as assessed using Rainbow markers (Amersham), are shown on the left. Levels of PKB are also shown to indicate equal amounts of protein within the samples. These results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

FcγR ligation and fMLP stimulation, but not ANCA, activates p85 PI3K

To examine the PI3K isoform activated by fMLP, ANCA, and FcγR ligation (using either cross-linking antibodies or aggregated IgG), the in vitro activity of PI3K in anti-p85 immunoprecipitates was determined. Stimulation of TNF-α–primed neutrophils with fMLP induced significant activation of p85 PI3K 30 seconds after stimulation (Figure 7A; P < .04). Stimulation with 3 different preparations of MPO-ANCA or PR3-ANCA, however, failed to induce p85 PI3K activation above that seen in cells stimulated with normal IgG at any time examined (Figure 7A). By contrast, individual cross-linking of FcγRII (FcRII XL) and FcγRIII (FcRIII XL) using monoclonal antibodies led to significant p85 PI3K activation after 1 minute (Figure 7B; P < .05). Antibody cross-linking of both FcγR together (FcRII+III XL) also induced significant p85 activity, which was evident after 30 seconds of stimulation (Figure 7B; P < .04). Ligation of FcγR using 250 μg/mL heat-aggregated normal IgG also induced significant p85 activity, which was evident after 30 seconds and increased over 15 minutes (Figure 7C).

p85 PI3K activity in neutrophils stimulated with fMLP or ANCA IgG or by conventional FcγR ligation using either cross-linking antibodies or aggregated IgG.

p85 PI3K activation measured by in vitro kinase assays in anti-p85α immunoprecipitates from aliquots of 4 × 106 neutrophils primed with 2 ng/mL TNF-α and stimulated with either (A) 1 μM fMLP, 250 μg/mL MPO-ANCA, PR3-ANCA, or normal IgG or (B) 1 μg/mL IV.3 (FcRII XL), 1 μg/mL 3G8 (FcRIII XL), or 1 μg/mL both anti-FcγR monoclonal antibodies (FcRII+III XL) followed by 10 μg/mL GAM F(ab′)2 cross-linking antibody or (C) primed, unstimulated cells or cells stimulated with either 1 μM fMLP, 250 μg/mL normal IgG, or 250 μg/mL heat-aggregated IgG for 30 seconds (■), 1 minute (░), and 15 minutes (▨). All experiments were repeated 3 times using neutrophils from different donors, 3 different MPO-ANCA and PR3-ANCA IgG preparations, and 2 different normal IgG samples (native and heat-aggregated) and duplicates of all samples. Results show mean ± SEM of data pooled from all 3 experiments.

p85 PI3K activity in neutrophils stimulated with fMLP or ANCA IgG or by conventional FcγR ligation using either cross-linking antibodies or aggregated IgG.

p85 PI3K activation measured by in vitro kinase assays in anti-p85α immunoprecipitates from aliquots of 4 × 106 neutrophils primed with 2 ng/mL TNF-α and stimulated with either (A) 1 μM fMLP, 250 μg/mL MPO-ANCA, PR3-ANCA, or normal IgG or (B) 1 μg/mL IV.3 (FcRII XL), 1 μg/mL 3G8 (FcRIII XL), or 1 μg/mL both anti-FcγR monoclonal antibodies (FcRII+III XL) followed by 10 μg/mL GAM F(ab′)2 cross-linking antibody or (C) primed, unstimulated cells or cells stimulated with either 1 μM fMLP, 250 μg/mL normal IgG, or 250 μg/mL heat-aggregated IgG for 30 seconds (■), 1 minute (░), and 15 minutes (▨). All experiments were repeated 3 times using neutrophils from different donors, 3 different MPO-ANCA and PR3-ANCA IgG preparations, and 2 different normal IgG samples (native and heat-aggregated) and duplicates of all samples. Results show mean ± SEM of data pooled from all 3 experiments.

Compared to native ANCAs or normal IgG samples, aggregation of both PR3-ANCA and MPO-ANCA IgG also led to significant p85 activity, with levels of 0.6 to 0.8 PtdIns3P U at 30 seconds and 1.2 to 1.4 U after 15 minutes. (Figure 7C). Even at lower concentrations (50-100 μg/mL), aggregated ANCA IgG and aggregated normal IgG samples were able to induce significant p85 activity (eg, stimulation with 50 and 100 μg/mL aggregated IgG for 30 seconds and resulted in 0.55-0.7 and 0.62-0.9 PtdIns(3)P U, respectively, compared to 0.12-0.23 and 0.2-0.3 PtdIns(3)P U, respectively, in nonaggregated IgG samples;P < .04). These data showed that native ANCAs do not recruit the p85/p110 isoform of PI3K, suggesting that an alternative isoform of PI3K, possibly Gβγ-activated p101/p110γ, is recruited.

fMLP and ANCA, but not anti-FcγR–induced, superoxide generation can be blocked with pertussis toxin

To determine whether ANCA activation of neutrophils involves heterotrimeric G-protein activation, which could then lead to Gβγ-mediated recruitment of p101/p110γ, the effect of pertussis toxin (a Gi/o protein inhibitor) on superoxide generation was investigated. Pretreatment with 0.1 to 2 μg/mL pertussis toxin led to significant inhibition of both the fMLP and the ANCA-induced oxidative burst—for example, at 0.1 μg/mL, there is 100% inhibition of fMLP response and 70% to 75% inhibition of MPO-ANCA and PR3-ANCA responses (P < .005). By contrast, pretreatment with equivalent concentrations of pertussis toxin had no significant effect on the superoxide response seen after conventional FcγR cross-linking.

Discussion

Systemic vasculitis is an important cause of pulmonary hemorrhage and rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis with acute renal failure. Where ANCAs are present in such diseases, these autoantibodies have been implicated in the initiation of neutrophil-mediated vascular and endothelial cell damage.1-3 The results presented in this study demonstrate that the ANCA-induced oxidative burst from primed neutrophils can be blocked by pretreatment with anti-FcγR antibodies. This implies that FcγR engagement is involved in ANCA activation of primed neutrophils. Despite the involvement of FcγR, we demonstrate for the first time that the activation events evoked by ANCAs are distinct from those induced by conventional FcγR ligation, either by cross-linking of FcγR using monoclonal antibodies or by aggregated IgG, because ANCAs stimulate neither activation of PLD nor production of the PLD-induced messengers PtdOH and DAG. Our results also show that ANCAs activate PI3K and subsequently PKB. However, ANCAs use a PI3K isoform distinct from conventional FcγR ligation, which activates the p85/p110 isoform.

Blocking either FcγRIIa or FcγRIIIb with anti-FcγR antibodies led to significant inhibition (up to 65%) of the ANCA-induced superoxide response, whereas the combined use of both anti-FcγRII and anti-FcγRIII antibodies could abolish the response. Our results confirm and extend previous findings that ANCA activation of neutrophils requires both FcγRIIa and FcγRIIIb engagement9-11; indeed, we have previously shown that F(ab′)2 fragments of ANCAs alone are insufficient to produce a superoxide response.12 Therefore, these results demonstrate an important role for FcγR in the initiation of ANCA-mediated signal transduction pathways.

The activation of neutrophils by ANCAs was dependent on PI3K. The fungal metabolite wortmannin, which selectively inhibits PI3K at concentrations of 5 to 10 nM,27 inhibited ANCA-induced superoxide production at a concentration of 5 nM. Moreover, the structurally and functionally distinct PI3K inhibitor LY29400235 also blocked ANCA-mediated superoxide production. Stimulation of neutrophils with ANCAs and fMLP and cross-linking them with FcγR also led to the activation of PKB, but with differing kinetics. PKB, a major downstream target of PI3K, has been reported to be involved in the neutrophil respiratory burst and exocytosis.20 Altogether, these results suggest a role for PI3K in the ANCA-induced oxidative burst. This is supported by a recent study showing that PI3K–generated PIP3 enhances superoxide production in TNF-α–primed neutrophils.36 PI3K activation has been shown to mediate the activation of Rac by certain growth factors,37 resulting in membrane ruffling. Thus, ANCA-stimulated PI3K could also play a role in the shape change and actin reorganization reported previously,38 which may lead to neutrophil sequestration within the microcirculation and contribute to the vascular damage associated with systemic vasculitis.

Two types of PI3K enzymes have been described in human neutrophils, the phosphotyrosine-associated class IA p85/p110 isoform and the G-protein–activated class IB p101/p110γ isoform.24 Stimulation with fMLP is known to strongly activate this latter isoform,39 though there have been reports that fMLP can also activate p85/p110 PI3K.40 In this study, stimulation with fMLP led to the activation of p85 PI3K, though to a lesser degree than stimulation of neutrophils by conventional FcγR ligation using either cross-linking antibodies or aggregated IgG. Stimulation with ANCA, on the other hand, failed to activate p85 PI3K, though we could demonstrate significant production of the PI3K–generated second messenger PIP3. Thus, it is likely that ANCAs activate the p101/p110γ PI3K isoform. In support of this, pretreatment of neutrophils with pertussis toxin (a Gi/o protein inhibitor) inhibits ANCA-induced, but not anti-FcγR-stimulated, superoxide generation.

After heat aggregation of ANCA IgG, the signaling response is similar to that obtained with conventional FcγR ligation, either using cross-linking anti-FcγR antibodies or aggregated IgG. Thus, the conformational structure and specific binding properties of the ANCA IgG are central to its unique signaling effects (lack of PLD or p85 PI3K activation). The mechanism by which ANCAs activate neutrophils in a manner distinct from conventional FcγR ligation is unclear but implies an important role for the ANCA antigens MPO and PR3 in modifying the response. ANCA binding to MPO or PR3 on the neutrophil surface may result in cross-linking of these molecules and their internalization, leading to recruitment of distinct signaling molecules or cascades. Alternatively, given that both MPO and PR3 are highly charged molecules, they may associate with membrane components that then alter the downstream signaling that occurs after concurrent ANCA FcγR engagement. Our results clearly point to the existence of an FcγR-modifying mechanism of ANCA-stimulated neutrophil activation.

This study is the first to demonstrate divergence in the signaling pathways evoked by ANCAs and conventional FcγR ligation of primed neutrophils. It also shows that ANCA activation of primed neutrophils uses a different signaling pathway than that stimulated by fMLP, where PLD may play a role in early, rapid superoxide production. Further elucidation of the distinct ANCA-mediated signaling processes may provide ways to circumvent inappropriate neutrophil activation in vivo and lead to improved targeting of drug intervention strategies for the treatment of systemic vasculitis.

We thank Prof E. Skolnik for his kind gift of the yeast farnesylated-p110 expression vector, Dr R. L. Holder for statistical advice, Drs D. Scheel-Toellner and R. McEwan for technical advice, and Prof R. Jefferis for useful discussions.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Caroline O. S. Savage, Renal Immunobiology, MRC Centre for Immune Regulation, The Medical School, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, B15 2TT, United Kingdom; e-mail:c.o.s.savage@bham.ac.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal