Abstract

Some chelators of the pyridoxal isonicotinoyl hydrazone class have antiproliferative activity that is far greater than desferrioxamine (DFO). In this study, DFO was compared with one of the most active chelators (311) on the expression of molecules that play key roles in cell-cycle control. This was vital for understanding the role of iron (Fe) in cell-cycle progression and for designing chelators to treat cancer. Incubating cells with DFO, and especially 311, resulted in a decrease in the hyperphosphorylated form of the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene product (pRb). Chelators also decreased cyclins D1, D2, and D3, which bind with cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (cdk4) to phosphorylate pRb. The levels of cdk2 also decreased after incubation with DFO, and especially 311, which may be important for explaining the decrease in hyperphosphorylated pRb. Cyclins A and B1 were also decreased after incubation with 311 and, to a lesser extent, DFO. In contrast, cyclin E levels increased. These effects were prevented by presaturating the chelators with Fe. In contrast to DFO and 311, the ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor hydroxyurea increased the expression of all cyclins. Hence, the effect of chelators on cyclin expression was not due to their ability to inhibit ribonucleotide reductase. Although chelators induced a marked increase in WAF1 and GADD45 mRNA transcripts, there was no appreciable increase in their protein levels. Failure to translate these cell-cycle inhibitors may contribute to dysregulation of the cell cycle after exposure to chelators.

Introduction

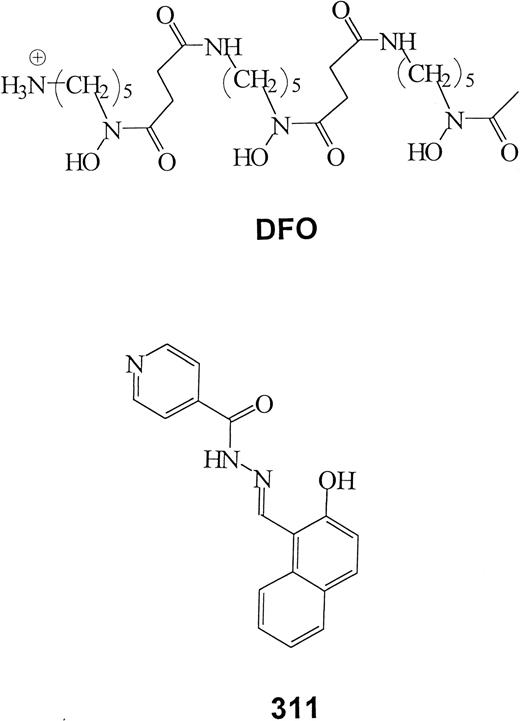

Many studies have demonstrated that some tumor cells are sensitive to iron (Fe) chelation therapy.1-5 The ability of these ligands to inhibit growth reflects the importance of Fe in crucial metabolic pathways, including DNA synthesis and adenosine triphosphate production.6,7 Numerous cancer cell types are more susceptible to the effects of chelators than normal cells.6-10 Indeed, a series of studies has demonstrated that the clinically used chelator, desferrioxamine (DFO; Figure1), is capable of a potent cytotoxic effect on neuroblastoma (NB) cells both in vitro and in clinical trials.11-15 However, DFO has some serious disadvantages, including high cost, short plasma half-life, poor absorption from the gut, limited membrane permeability, and long subcutaneous administration (12-24 hours a day, 5-6 times a week).7Hence, further studies are necessary to develop more effective ligands as anticancer agents.

Some chelators of the PIH class show high antiproliferative activity.7,16 These compounds have high affinity and specificity for Fe similar to that of DFO and much greater than that of EDTA.17 We have characterized PIH analogues of the 2-hydroxy-1-naphthylaldehyde group that show much greater antiproliferative activity than DFO.18-21 In fact, their activity was comparable to bleomycin and cisplatin.19 Our studies have shown that their ability to chelate intracellular Fe is the reason for the cytotoxic effects.18-21 One of the most active chelators identified was 2-hydroxy-1-naphthylaldehyde isonicotinoyl hydrazone, also known as 311 (Figure 1).18-20

Despite the well-known role of Fe in cellular proliferation and DNA synthesis, surprisingly little is known concerning the role of this metal ion in the molecular control of cell-cycle progression. Some Fe chelators inhibit the activity of ribonucleotide reductase (RR), a critical Fe-containing enzyme involved in the conversion of ribonucleotides to deoxyribonucleotides (dNTPs).22-25 The reduction in dNTPs prevents DNA synthesis, which is thought to result in a G1/S arrest after exposure to chelators.3,19,24,26 27

Because the G1/S checkpoint is crucial in terms of entrance into DNA synthesis, it is relevant to assess the role of Fe and chelators in this process. This is required for understanding the role of Fe in proliferation and the design of chelators that inhibit cancer cell growth. In a recent study,20 we examined the effect of DFO and 311 on the expression of several genes that play roles in regulating cell-cycle progression (eg, WAF1 andGADD-45).28-30 An increase in WAF1and GADD45 expression can occur by p53-dependent or p53-independent mechanisms.31-33 Our studies using SK-N-MC and K562 cells suggest that chelators induce the expression of these genes through a p53-independent process.20

In the present study, we examined the effect of 311 compared to DFO on the expression of a variety of molecules involved in cell-cycle progression, particularly the G1/S transition. Cell-cycle progression is regulated by the sequential activation and subsequent inactivation of a family of cyclin-dependent protein kinases (cdks).34 The active forms of these kinases are heterodimers composed of a regulatory subunit known as a cyclin and a catalytic subunit with kinase activity.34 A critical target of cdk activity is the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene product (pRb). Phosphorylation of pRb by cdk activity (eg, through cdk4-cyclin D complexes) results in the release of E2F-DP1 heterodimeric transcription factors that transcribe genes essential for G1/S progression, such as cyclins A and E.35-37

The cdks are numbered sequentially in order of discovery (cdk1, cdk2, and so on), with p34cdc2 being cdk1 in mammals. Ten major cyclin families have been identified and are designated cyclins A to J.38 Progression through the G1 phase of the cycle is mediated by the appearance and disappearance of cyclins D, E, and possibly A.34-36,38,39 Progression through S is mediated predominantly by cyclin A, whereas passage through G2 and M is mainly mediated by B-type cyclins.34-36,38,39 In mammalian cells, the G1-specific cdk activities are composed of complexes between D-type cyclins and either cdk4 or cdk6 and also between cyclin E (and possibly cyclin A) and cdk2.38,39 An important mitotic cdk activity is mediated through complexing cyclin B and cdk1.39 Various factors modulate cdk activity by altering cyclin levels, the levels of cdk inhibitory proteins (eg, p16, p21, p27), and the phosphorylation of the cdks. Expression of p53 increases after DNA damage or when dNTP levels are low, and it transactivates genes that affect cell-cycle progression—for example,WAF1(p21Cip1), GADD45, andmdm-2.40 The WAF1 gene encodes the universal cdk inhibitor p21Cip1, which can also act on the proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) required for DNA synthesis.39GADD45 is induced on DNA damage and can arrest the cell cycle and is also involved in DNA nucleotide excision repair.30 On the other hand, p53-mediated transactivation of mdm-2 results in feedback control of p53 activity.30

In the current investigation, we demonstrate that potent Fe chelators affect the expression of essential molecules involved in regulating the cell cycle. Moreover, the effect observed cannot be completely attributed to the inhibition of RR because the widely used inhibitor of this enzyme, hydroxyurea (HU), had a different effect. The results of this study suggest that Fe chelators affect multiple molecular targets involved in cell-cycle control in addition to RR. These findings are significant for understanding the effect of chelators on inhibiting the proliferation of cancer cells and the role of Fe in cell-cycle progression.

Materials and methods

Chelators and their iron(III) complexes

Cell culture

Human SK-N-MC neuroepithelioma cells, IMR-32 NB cells, SK-N-SH NB cells, and MCF-7 breast cancer cells were from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). The SH-SY-5Y NB cell line was provided by Hiroki Nishimura (Queensland Pharmaceutical Research Institute, Brisbane, Australia). The BE-2 NB cell line was a gift from Dr Greg Anderson (The Queensland Institute for Medical Research, Brisbane, Australia). The MCF-7, SK-N-MC, SK-N-SH, and SH-SY-5Y cell lines were grown in Eagle modified minimum essential medium (EMEM; Gibco, Melbourne, Australia) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; CSL, Melbourne, Australia), 1% (vol/vol) nonessential amino acids (Gibco), 2 mM L-glutamine (Sigma), 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Gibco), 100 U/mL penicillin (Gibco), and 0.28 μg/mL fungizone (Squibb Pharmaceuticals, Montreal, Canada). The IMR-32, and BE-2 cell lines were grown in RPMI (Gibco) containing 10% FCS, and the supplements described above for EMEM. Cellular growth and viability were assessed using standard techniques.43 44 In all experiments, nonsynchronous cycling cells were used because tumors in vivo are found in this state.

Antibodies

Mouse anti–human p53 monoclonal antibody (mAb) (Ab-1; catalog no. OP03L) was used at 0.1 μg/mL and was from Oncogene Research Products (Darmstadt, Germany). Mouse anti–human p27 (Kip1/Ab1) mAb (catalog no. ms-256-p1) was used at 0.4 μg/mL and was from Neomarkers (Union City, CA). mAb against β-actin (clone AC-15; used at a dilution 1:5000) was from Sigma. Rabbit anti–human p73 polyclonal antibody (catalog no. 90 001 500; used at 0.2 μg/mL) was from Silenus Labs (Melbourne, Australia).

The remaining antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). These are listed in the 2 sections below—mouse antihuman mAbs and rabbit antihuman polyclonal antibodies. Catalog numbers and working concentrations are listed next to each antibody.

Monoclonal antibodies.

Cyclin A (BF683/SC239; 0.2 μg/mL); cyclin B1 (GNS1/SC245; 0.1 μg/mL); cyclin D1 (R124/SC6281; 0.2 μg/mL); cyclin E (HE12/SC247; 0.1 μg/mL); cdk2 (D12/SC6248; 0.2 μg/mL); cdk6 (B10/SC7961; 0.4 μg/mL); GADD45 (4T-27/SC796; 0.2 μg/mL); p21Cip1(187/SC817; 0.2 μg/mL); PCNA (PC10/SC56; 0.5 μg/mL); pRb (IF8/SC102; 0.2 μg/mL).

Polyclonal antibodies.

c-fos (4/SC52; 0.2 μg/mL); cyclin D2 (H289/SC754; 0.2 μg/mL); cyclin D3 (C16/SC182; 0.2 μg/mL); cdk4 (C22/SC260; 0.1 μg/mL); E2F-1 (C-20/SC193; 0.2 μg/mL); p16 (C-20/SC468; 0.2 μg/mL); p63α (SC-8344; 0.2 μg/mL).

Northern blot analysis

Northern blot analysis was performed by isolating total RNA as described previously.20

Western blot analysis

Whole cell protein extracts were obtained by lysing 2 × 106 cells per sample. Cells were removed from a 75-cm2 tissue culture flask on ice using a plastic policeman in the presence of 700 μL ice-cold lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4]), 1% NP-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 1 mM NaF, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, pepstatin and aprotinin, respectively). The DNA in the lysate was sheared by passage through a 21-gauge needle before centrifugation at 15 000 rpm for 30 minutes at 4°C. The protein concentration of the supernatant was assessed by the Bio-Rad protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

For nuclear protein extracts, cells were scraped from the flasks on ice in 800 μL ice-cold nuclear lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.6], 20% glycerol, 10 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM PMSF, 10 μg/mL leupeptin, 10 μg/mL pepstatin, and 100 μg/mL aprotinin) and then centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 5 minutes at 4°C. Nuclei were resuspended at 2.5 × 107 nuclei/mL in 250 μL ice-cold nuclear lysis buffer containing 500 mM NaCl. The nuclei were then gently rocked for 1 hour at 4°C and centrifuged at 10 000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. The protein concentration of the supernatant was determined as described above.

Lysates were mixed with loading buffer under reducing conditions and were then added (60 μg/lane) to a sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel (polyacrylamide, 10%). After electrophoresis, the proteins were electroblotted for 1 hour at 4°C onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (NEN, Boston, MA). The membrane was stained with Ponceau S (Sigma) to ensure all lanes contained equal amounts of protein. As an additional check of protein loading, membranes were probed for β-actin. Membranes were then washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% Tween-20 (Sigma) (PBST) and blocked with 6% nonfat milk and 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma) in PBS for 60 minutes. Membranes were then washed 3 times in PBST, for 10 minutes each time.

Antibodies were added to PBS containing 6% nonfat milk and 1% BSA, and they were incubated with the membranes for 1.5 hours at room temperature. Membranes were then washed 3 times in PBST, for 10 minutes each time. After washing, antimouse (0.03-0.1 μg/mL) or antirabbit (0.05-0.1 μg/mL) antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Zymed Laboratories) were incubated with the membranes for 60 minutes at room temperature. After washing, the membranes were developed using the Western Blot Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus (NEN, Boston, MA) by using a 1-minute incubation and exposure to x-ray film for 30 seconds to 15 minutes. Films were scanned and montages assembled with Adobe Photoshop. All densitometric data were normalized to the β-actin–loading control.

Results

Iron chelation by desferrioxamine, and especially 311, decreases expression of cyclins A, B1, D1, D2, and D3 but increases the expression of cyclin E: effect of chelator concentration

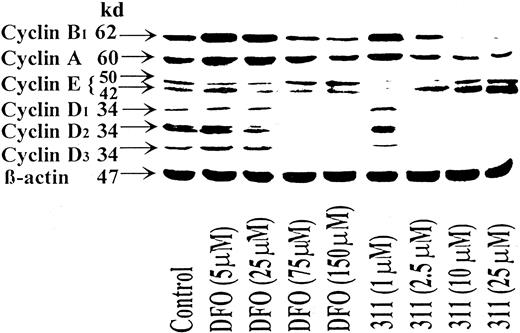

One mechanism of how chelator-mediated growth arrest could occur is by down-regulating or up-regulating the expression of proteins that control progression through the G1-S and G2-M transitions. In initial experiments, we compared the effect of DFO (5-150 μM) and 311 (1-25 μM) on the expression of the cyclins (Figure 2). Protein levels of the G1 cyclins (cyclins A, D1, D2, D3, and E) and a G2 cyclin (cyclin B1) were investigated after a 30-hour incubation at 37°C with SK-N-MC cells (Figure 2). The SK-N-MC cell type has nonfunctional p53,46,47 and the results obtained were compared to SH-SY-5Y NB cells, which have wild-type p53.48 In all experiments, the effects of chelators on cyclin expression in SH-SY-5Y cells were similar to that in SK-N-MC.

The iron chelator 311 is more effective than DFO at decreasing the expression of the cyclins A, B1, D1, D2, and D3 and increasing the expression of cyclin E.

SK-N-MC cells were incubated with DFO (5-150 μM) or 311 (1-25 μM) for 30 hours at 37°C, and the cells were harvested. Western blot analysis was then performed as described in “Materials and methods.” Results shown are representative of 3 separate experiments performed.

The iron chelator 311 is more effective than DFO at decreasing the expression of the cyclins A, B1, D1, D2, and D3 and increasing the expression of cyclin E.

SK-N-MC cells were incubated with DFO (5-150 μM) or 311 (1-25 μM) for 30 hours at 37°C, and the cells were harvested. Western blot analysis was then performed as described in “Materials and methods.” Results shown are representative of 3 separate experiments performed.

Increasing concentrations of DFO and 311 decreased cyclins A, B1, D1, D2, and D3 compared to the control (Figure 2). The greatest decrease in expression was found for the D-type cyclins, which were ablated at DFO concentrations of 75 to 150 μM or at a 311 concentration of 2.5 μM and above. The much greater activity of 311 compared to DFO at decreasing the expression of the cyclins is in good correlation with the greater Fe chelation efficacy18-20 and antiproliferative effects of 311.18 19 Before the decrease in cyclin D levels, an initial slight increase in cyclins D1, D2, and D3 was observed at 5 μM DFO, whereas increased expression of cyclin D1 and D2 was seen at 1 μM 311 (Figure 2). The reason for the increase in expression of these molecules at low chelator concentrations and the decrease at higher concentrations remains unclear. It can be speculated at low chelator concentrations that a compensatory increase in expression may occur to overcome the cell-cycle arrest. Further detailed studies are required to elucidate the precise molecular mechanisms involved.

Compared to the control, cyclin A and B1 expression increased at low concentrations of DFO (5 and 25 μM) and 311 (1 μM) and then decreased as the concentration of both chelators increased (Figure 2). The effect of the chelators on cyclin A levels was less than that found for cyclins B1, D1, D2, and D3; again, 311 was more effective than DFO. For example, at DFO and 311 concentrations of 150 μM and 25 μM, normalized cyclin A levels were reduced by 5% and 70% compared to the control, respectively. In repeat experiments, only 311 consistently decreased cyclin A and B1 levels.

Cyclin E appeared as double bands in Western blots at 42 and 50 kd (Figure 2), and this may result from alternative splicing of the gene.49 50 In some blots, a third cyclin E band was found between these 2 bands. The effect of the chelators on the expression of cyclin E was opposite that found for other cyclins. At low concentrations of DFO (5-25 μM) and 311 (1 μM), there was a decrease in both the 42- and the 50-kd cyclin E bands compared to the control (Figure 2). Increasing the DFO concentration up to 150 μM resulted in a 1.6-fold increase in the normalized level of the 50-kd cyclin E band compared to the control, whereas the 42-kd band was only slightly elevated (Figure 2). In a more pronounced manner, increasing concentrations of 311 up to 25 μM resulted in a 3-fold and a 5-fold increase in the 50-and 42-kd cyclin E bands, respectively, compared to the control (Figure 2).

Effect of incubation time with chelators on cyclin expression

The effect of incubation time with the chelators on the protein levels of the cyclins was examined by incubating SK-N-MC cells for 2 to 30 hours at 37°C with either DFO (150 μM) or 311 (25 μM) (data not shown). The effect of the chelators at reducing cyclins D1 and D2 became evident after an 8-hour incubation with 311 but not DFO. A decrease in cyclin D2 was found after a 4-hour incubation with 311, and this became more evident as the incubation increased to 8 hours. Longer incubations of 20 to 30 hours ablated the expression of cyclins D1, D2, and D3 after incubation with DFO and 311. A decrease in cyclins A and B1 compared to the relevant control was seen only after a 20-hour incubation with 311, whereas DFO did not have any effect. After a 30-hour incubation, both DFO and 311 decreased cyclin B1 levels compared to the relevant control, yet only 311 appreciably reduced cyclin A levels after this incubation. An increase in cyclin E levels was found after an 8-hour incubation with DFO and 311, the extent of this becoming more clear after 30 hours.

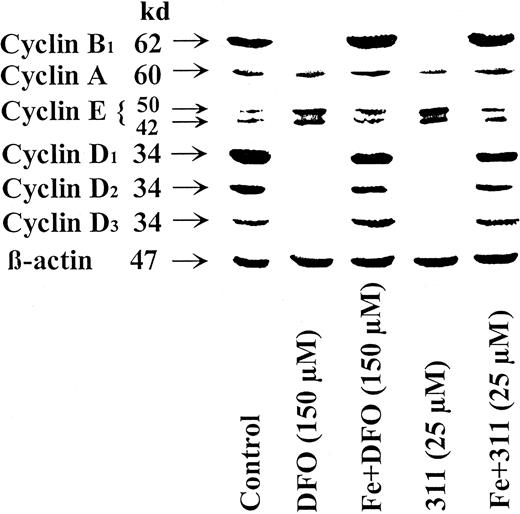

Saturation of chelators with iron prevents their effects on cyclin expression

To determine whether the effect of DFO and 311 on cyclin expression was owing to their ability to bind Fe, the Fe(III) complexes of these chelators were prepared, and their effects on cyclin expression were compared to the ligands (Figure3). In contrast to chelators, the Fe complexes did not increase cyclin E or decrease cyclins A, B1, D1, D2, or D3. Thus, Fe chelation by the ligands was essential for their effects on cyclin expression.

Saturation of DFO or 311 with iron prevents their effects at reducing the protein levels of cyclin A, B1, D1, D2, and D3 and increasing cyclin E protein levels.

The SK-N-MC neuroepithelioma cell line was incubated with DFO (150 μM), the DFO-Fe complex (150 μM), 311 (25 μM), or the 311-Fe complex (25 μM) for 30 hours at 37°C. Western blot analysis was then performed as described in “Materials and methods.” Results shown are representative of 3 separate experiments performed.

Saturation of DFO or 311 with iron prevents their effects at reducing the protein levels of cyclin A, B1, D1, D2, and D3 and increasing cyclin E protein levels.

The SK-N-MC neuroepithelioma cell line was incubated with DFO (150 μM), the DFO-Fe complex (150 μM), 311 (25 μM), or the 311-Fe complex (25 μM) for 30 hours at 37°C. Western blot analysis was then performed as described in “Materials and methods.” Results shown are representative of 3 separate experiments performed.

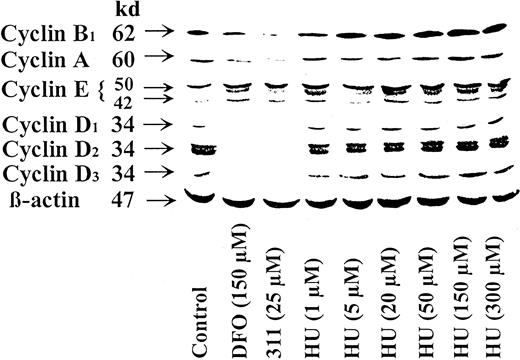

Ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor, hydroxyurea, acts differently than iron chelators on cyclin expression

It could be suggested that the effects of the Fe chelators at inducing changes in cyclin expression was through the inhibition of RR, which resulted in a decrease of dNTPs. Indeed, DFO and, especially, 311 inhibit 3H-thymidine incorporation and RR activity,19,24,25 and a decrease in dNTP levels can modulate other molecules (eg, p53) involved in controlling G1/S progression.51 To examine the possible regulatory role of RR activity on cyclin expression, we examined the effect of the RR inhibitor HU. This latter agent acts to inhibit RR by directly scavenging its free radical,52 whereas chelators act indirectly by stopping Fe uptake by RR.24 In contrast to DFO and 311 (Figures 2, 3, 4), increasing concentrations of HU (1-300 μM) increased the protein levels of cyclin A, B1, D1, D2, and D3 compared to the control (Figure 4). These results suggested that DFO and 311 act by a different mechanism than HU. However, similar to the results found for DFO and 311, HU increased the expression of cyclin E compared to the control at all concentrations (1-300 μM) (Figure 4).

Ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor HU acts differently to DFO and 311 as it increases the protein levels of cyclins A, B1, D1, D2, and D3 but has similar action to chelators in terms of increasing cyclin E.

The SK-N-MC neuroepithelioma cell line was incubated for 30 hours at 37°C with DFO (150 μM), 311 (25 μM), or HU (1-300 μM). Western blot analysis was then performed as described in “Materials and methods.” Results shown are representative of 3 separate experiments performed.

Ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor HU acts differently to DFO and 311 as it increases the protein levels of cyclins A, B1, D1, D2, and D3 but has similar action to chelators in terms of increasing cyclin E.

The SK-N-MC neuroepithelioma cell line was incubated for 30 hours at 37°C with DFO (150 μM), 311 (25 μM), or HU (1-300 μM). Western blot analysis was then performed as described in “Materials and methods.” Results shown are representative of 3 separate experiments performed.

Effect of DFO and 311 on the protein levels of cyclin-dependent kinases, cdk inhibitors, and tumor suppressor molecules p53, p63, and p73

Cyclin-dependent kinases.

After incubating SK-N-MC cells with DFO for 30 hours, normalized cdk2 protein levels increased slightly at DFO and 311 concentrations of 5 μM and 1 μM, respectively, and then decreased as the concentration increased (Figure 5). At a DFO concentration of 150 μM, the normalized cdk2 levels had decreased to 30% of the untreated control, whereas 311 at 25 μM totally prevented cdk2 expression (Figure 5). The effects of the chelators at reducing cdk2 expression could be prevented by presaturating them with Fe (results not shown). In contrast to cdk2, neither chelator had any marked effect on cdk4 expression (Figure 5). Repeated attempts to identify cdk6 were made using nuclear lysates with SK-N-MC and SH-SY-5Y cells. However, the results were negative despite detection of other nuclear proteins (eg, c-fos).

Chelator 311 markedly reduced the expression of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (cdk-2) but not cdk4.

The SK-N-MC neuroepithelioma cell line was incubated for 30 hours at 37°C with DFO (5-150 μM) or 311 (1-25 μM). Western blot analysis was then performed as described in “Materials and methods.” Results shown are representative of 3 separate experiments performed.

Chelator 311 markedly reduced the expression of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (cdk-2) but not cdk4.

The SK-N-MC neuroepithelioma cell line was incubated for 30 hours at 37°C with DFO (5-150 μM) or 311 (1-25 μM). Western blot analysis was then performed as described in “Materials and methods.” Results shown are representative of 3 separate experiments performed.

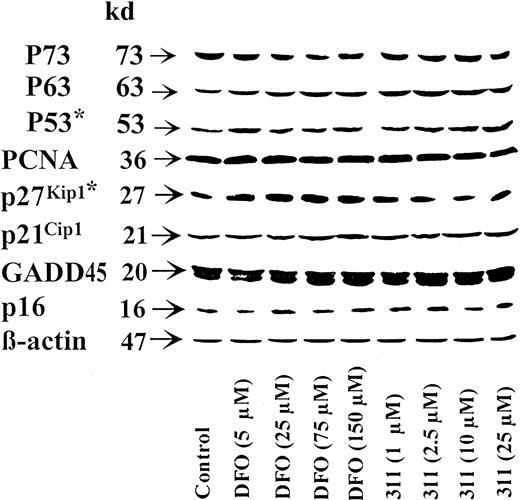

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors and other cell-cycle inhibitory molecules.

There are 2 major families of cdk inhibitors, the Cip/Kip and the INK4 families.34 Of the Cip/Kip family, we have examined the effect of chelators on the expression of p27Kip1 and p21Cip1 (WAF1), the latter of which is transactivated by the tumor suppressor protein p53.28-30Of the INK4 members, expression of p16 was assessed. We also examined the influence of chelators on the expression of PCNA and GADD45.

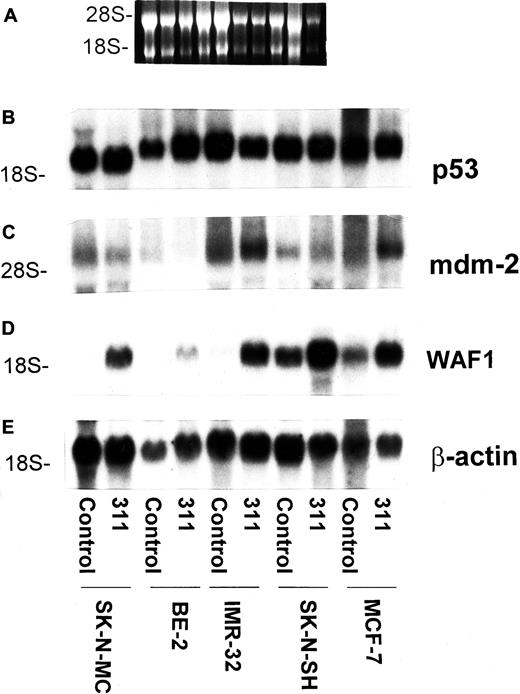

Our previous study demonstrated that the increase in WAF1mRNA levels after exposure to DFO or 311 appeared to occur by a p53-independent pathway in SK-N-MC and K562 cells.20 To further examine the effects of chelators on the expression ofWAF1, a range of neoplastic cell lines was compared to SK-N-MC (Figure 6). In these studies we examined the effect of incubating cells with control medium or 311 (25 μM) for 30 hours at 37°C on the levels of p53,mdm-2, and WAF1 mRNA in SK-N-MC cells, BE-2 NB cells, IMR-32 NB cells, SK-N-SH NB cells, and MCF-7 breast cancer cells (Figure 6). The latter 3 cell lines have native p53, some sequestered in the cytosol, but some of which becomes translocated to the nucleus, where it transactivates target genes.47,53 The SK-N-MC cell line has mutant p53,46,47 and it was of interest to compare the effects of 311 on cells with both mutant and native p53 (Figure 6). It is unknown whether BE-2 cells have native or mutant p53, but it was included as a positive control because we previously showed that exposure to 311 resulted in increased WAF1 mRNA levels.20 Incubation with 311 had no appreciable or consistent effect on the levels of p53 or mdm-2mRNAs compared to the relevant control for each cell type (Figure6). The p53 mRNA from SK-N-MC cells runs more quickly in gels because of a deletion mutation resulting in a smaller molecule.46 For all cell types, an increase inWAF1 mRNA occurred relative to each control, indicating that p53 status did not affect the result obtained (Figure 6). Interestingly, WAF1 was expressed under control conditions in some cell types (eg, SK-N-SH) but not others (eg SK-N-MC). The reason for this may relate to different mechanisms of cell-cycle control in different cancer cell types.

The chelator 311 has no effect on p53 or mdm-2 mRNA levels but increases the expression of WAF1 mRNA in a variety of cell types with wild-type or mutant p53.

The SK-N-MC neuroepithelioma, BE-2 neuroblastoma, IMR-32 neuroblastoma, SK-N-SH neuroblastoma, and MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines were exposed to control medium or 311 (25 μM) for 30 hours at 37°C. Cells were harvested, and the total mRNA was isolated using standard techniques.20 (A) Ethidium bromide staining of the agarose gel; (B) p53; (C) mdm-2; (D) WAF-1; (E) β-actin. The result is representative of 2 separate experiments performed.

The chelator 311 has no effect on p53 or mdm-2 mRNA levels but increases the expression of WAF1 mRNA in a variety of cell types with wild-type or mutant p53.

The SK-N-MC neuroepithelioma, BE-2 neuroblastoma, IMR-32 neuroblastoma, SK-N-SH neuroblastoma, and MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines were exposed to control medium or 311 (25 μM) for 30 hours at 37°C. Cells were harvested, and the total mRNA was isolated using standard techniques.20 (A) Ethidium bromide staining of the agarose gel; (B) p53; (C) mdm-2; (D) WAF-1; (E) β-actin. The result is representative of 2 separate experiments performed.

In contrast to the robust increase in WAF1 mRNA after incubation of SK-N-MC cells with chelators observed in Figure 6 and in prior investigations,20 there was only a slight increase in p21Cip1 protein levels (Figure7). Similarly, though a marked increase in the GADD45 transcript was observed in this study (data not shown) and previous studies,20 no appreciable change was observed in its protein level (Figure 7). In addition, no alterations were observed in the protein levels of p16 or PCNA in SK-N-MC cells after incubation with DFO or 311 (Figure 7). The expression of p27Kip1 was not detected in SK-N-MC cells, and chelators had no appreciable effect on the level of this molecule in SH-SY-5Y cells (Figure 7).

Effect of DFO and 311 concentration on cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors and other cell-cycle inhibitory molecules.

The SK-N-MC neuroepithelioma cell line or SH-SY-5Y neuroblastoma cell line* was incubated for 30 hours at 37°C with DFO (5-150 μM) or 311 (1-25 μM). Western blot analysis was then performed, as described in “Materials and methods.” Results shown are representative of 3 to 5 separate experiments performed.

Effect of DFO and 311 concentration on cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors and other cell-cycle inhibitory molecules.

The SK-N-MC neuroepithelioma cell line or SH-SY-5Y neuroblastoma cell line* was incubated for 30 hours at 37°C with DFO (5-150 μM) or 311 (1-25 μM). Western blot analysis was then performed, as described in “Materials and methods.” Results shown are representative of 3 to 5 separate experiments performed.

Incubation of SH-SY-5Y cells with the chelators resulted in an increase in the expression of p53 as a function of chelator concentration; this was most apparent for chelator 311 (Figure 7). In contrast, when using SK-N-MC cells, no change in p53 protein levels were detected (data not shown). The effect of chelators on expression of the p53 homologues p63 and p73 was also assessed as they acted on p53 DNA-binding sites.55 Hence, they might have been responsible for the p53-independent increase in WAF1 and GADD45 mRNAs in SK-N-MC cells after incubation with chelators.20 In 3 separate experiments, no marked or repeatable changes in expression were detected in p63 or p73 after incubation with chelators (Figure 7).

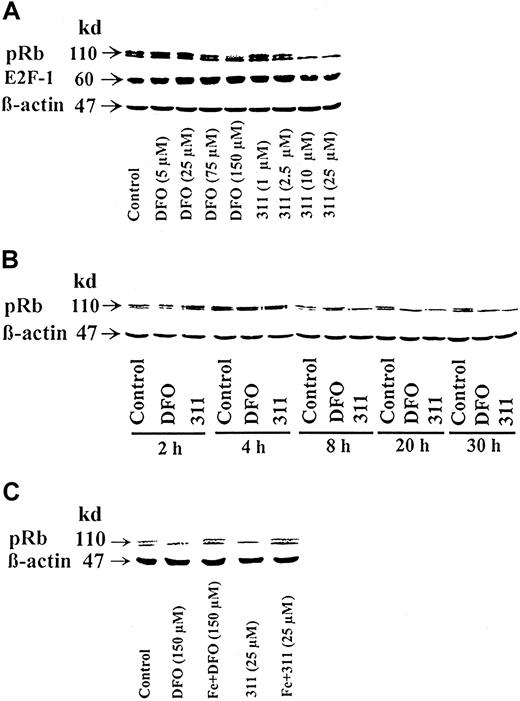

Effect of chelators on the expression of the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene product and associated cell-cycle control molecules

The best-characterized substrate of G1 cdk activity is the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene product, pRb.35Because chelators result in a marked decrease in D-type cyclins and cdk2 (Figures 2-5), it was relevant to assess their effect on pRb phosphorylation (Figure 8A-C). In SDS gels, pRb separates into 2 bands; the top band is the hyperphosphorylated molecule56 (Figure 8A-C, controls). Treatment of cells with DFO or 311 resulted in a decrease in the hyperphosphorylated band of pRb but only at concentrations of 150 μM and 10 to 25 μM, respectively (Figure 8A). For example, when compared to the normalized control, there was an 80% decrease or a total loss of the hyperphosphorylated form of pRb using DFO (150 μM) or 311 (10 μM), respectively (Figure 8A).

Effect of chelator concentration, chelator incubation time, and complexation with Fe on the phosphorylation status of the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene product (pRb).

(A) Chelator concentration. The SK-N-MC neuroepithelioma cell line was incubated for 30 h at 37°C with DFO (5-150 μM) or 311 (1-25 μM). (B) Chelator incubation time. Cells were incubated for 2-30 h with DFO (150 μM) or 311 (25 μM). (C) Complexation with Fe. Cells were incubated with DFO (150 μM) or 311 (25 μM) or their preformed Fe complexes for 30 hours at 37°C. Western blot analysis was then performed after each of these incubation conditions, as described in “Materials and methods.” Results shown are representative of 3 separate experiments performed.

Effect of chelator concentration, chelator incubation time, and complexation with Fe on the phosphorylation status of the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene product (pRb).

(A) Chelator concentration. The SK-N-MC neuroepithelioma cell line was incubated for 30 h at 37°C with DFO (5-150 μM) or 311 (1-25 μM). (B) Chelator incubation time. Cells were incubated for 2-30 h with DFO (150 μM) or 311 (25 μM). (C) Complexation with Fe. Cells were incubated with DFO (150 μM) or 311 (25 μM) or their preformed Fe complexes for 30 hours at 37°C. Western blot analysis was then performed after each of these incubation conditions, as described in “Materials and methods.” Results shown are representative of 3 separate experiments performed.

Considering that pRb binds E2F transcription factors and that E2F-1 has been shown to induce cyclin E transcription36,57 and G1/S progression,37 the effects of chelators on the expression of E2F1 was assessed. However, neither DFO nor 311 had any marked or repeatable effect on its protein levels in 3 experiments (Figure 8A).

The effect of 311 (25 μM) at causing hypophosphorylation of pRb was evident after an 8-hour incubation, whereas DFO (150 μM) required a 20-hour incubation to cause the same effect (Figure 8B). The effect of the chelators in causing a decrease in hyperphosphorylated pRb could be prevented by presaturating DFO and 311 with Fe (Figure 8C). These results suggest that the effect of the chelators on pRb was due to their ability to bind Fe.

Discussion

Despite the well-understood role of Fe in proliferation and the fact that Fe depletion generally results in G1/S arrest,3,19,24,26,27,58 little is known concerning the molecular mechanisms involved. This lack of information regarding the role of Fe is surprising, especially considering the well-characterized roles of p53, cyclins, and cdks in neoplasia and cell-cycle control.34-36 Understanding the role of Fe in these processes is vital for designing chelators to treat cancer and Fe overload.59

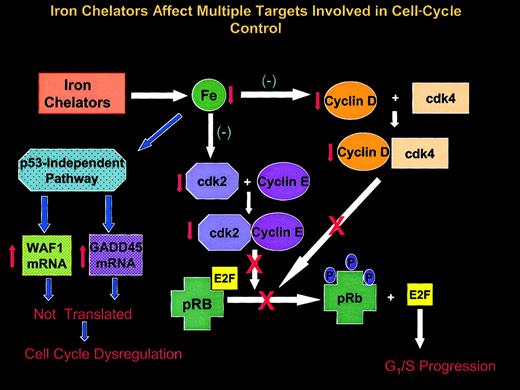

The current work is the first to comprehensively assess the effect of potent Fe chelators on a range of molecules that play key roles in G1/S progression (Figure 9). In fact, we have assessed changes in 20 key molecules involved in cell-cycle control after the incubation of cells with DFO compared to 311. Only a few earlier studies have examined the effects of Fe depletion on several components or one component involved in regulation of the cell cycle.56,58,60,61 In addition, in some of these latter studies,56,60 61 it was unclear whether the observed effects were attributed to Fe depletion or to some other effect of the chelator. In the current investigation, the effects of both chelators could be prevented by saturation of the ligand with Fe, strongly suggesting a role for Fe depletion in the effects observed.

Schematic illustration showing multiple effects of Fe chelators on the expression of molecules involved in cell-cycle control.

Iron chelators deplete intracellular Fe pools that can lead to a number of effects. In SK-N-MC neuroepithelioma cells, these compounds act through a p53-independent pathway to markedly increase the levels ofWAF1 and GADD45 mRNAs. However, the mRNAs of these cell-cycle inhibitory molecules are not efficiently translated, leading to possible cell-cycle dysregulation. Iron chelation also markedly reduces the expression of cyclins D1, D2, and D3, each of which forms a complex with cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (cdk4). The cyclin D-cdk4 complex is involved in progression through the G1phase and the phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene product (pRb). Phosphorylation of this latter molecule is required for it to release the E2F family of transcription factors critical for the transcription of genes essential for cell-cycle progression. Chelators also depress the expression of cdk2, which combines with cyclin E to further phosphorylate pRb that is essential for G1/S progression (see “Discussion” for further details).

Schematic illustration showing multiple effects of Fe chelators on the expression of molecules involved in cell-cycle control.

Iron chelators deplete intracellular Fe pools that can lead to a number of effects. In SK-N-MC neuroepithelioma cells, these compounds act through a p53-independent pathway to markedly increase the levels ofWAF1 and GADD45 mRNAs. However, the mRNAs of these cell-cycle inhibitory molecules are not efficiently translated, leading to possible cell-cycle dysregulation. Iron chelation also markedly reduces the expression of cyclins D1, D2, and D3, each of which forms a complex with cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (cdk4). The cyclin D-cdk4 complex is involved in progression through the G1phase and the phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene product (pRb). Phosphorylation of this latter molecule is required for it to release the E2F family of transcription factors critical for the transcription of genes essential for cell-cycle progression. Chelators also depress the expression of cdk2, which combines with cyclin E to further phosphorylate pRb that is essential for G1/S progression (see “Discussion” for further details).

Chelators affect expression of the cyclins and cdk-2 and the phosphorylation of pRb

For all effects on the expression of cell-cycle control molecules, chelator 311 was far more active than DFO. It has been shown that the greater activity of 311 is related to its high lipophilicity, resulting in high permeability through membranes and access to cellular Fe pools.18-20 With respect to the effect of chelators on cyclin expression, it was clear that the effects observed could not be explained by the inhibition of RR activity, because the potent inhibitor of this enzyme, HU, increased the levels of all cyclins (Figure 4). Therefore, Fe depletion through the chelators acts distally to RR and may suggest a more basic role of Fe in controlling the transcription of cell-cycle control molecules.

Chelators increased cyclin E expression and decreased the expression of all other cyclins assessed (Figure 2). The decrease in the D-type cyclin family and the increase of cyclin E with increasing chelator concentrations deserves comment. The difference in response of these latter cyclins to Fe chelators was not totally unexpected—both regulate different aspects of G1progression.62 After combination with the relevant cdks, cyclin E is thought to act on pRb but only after the D-type cyclins.35,36,57,58,62 In fact, cdk4-cyclin D complexes phosphorylate pRb, releasing E2F transcription factors that act to increase cyclin E transcription.35,36,57,58 62

Kung et al63 have shown that the inhibition of DNA synthesis using the S-phase inhibitor aphidicolin64 results in cyclin B accumulation. They propose that the inhibition of cell-cycle progression can dissociate normally coupled cell-cycle events, which has implications for cytotoxicity.65,66Similarly, in the current study, the increase in cyclin E protein levels at high chelator concentrations may reflect dysregulation of the cell cycle. Alternatively, and more likely, the chelators may inhibit progression through G1 at approximately the G1/S transition, when cyclin E protein levels are at their maximum and cyclin D levels have fallen.36

Because there was a marked accumulation of cyclin E levels as a function of chelator concentration, it can be suggested that sufficient phosphorylation of pRb by cyclin D-cdk4 complexes must have occurred to allow release of the E2F proteins that are necessary for cyclin E transcription.36,57,58 The decrease in the hyperphosphorylated form of pRb (Figure 8A) and the marked accumulation of cyclin E (Figure 2) may be a consequence of the lack of cdk2, preventing formation of the cyclin E-cdk2 complex (Figure 9). The kinase activity of this complex is necessary for maintaining the hyperphosphorylated form of pRb and progression to S.36Indeed, it is notable that as a function of chelator concentration, the decrease in hyperphosphorylated pRb occurs in concert with the reduction in cdk2 levels, both of which only occur at high ligand concentrations (Figures 5, 8). Our previous studies showed that high concentrations of these chelators were required to induce a G1/S arrest.19 Thus, a significant effect of the ligands appears to be the marked decrease in cdk2 levels preventing pRb hyperphosphorylation (Figure 9).

Apart from the effects on pRb, the marked decrease in cdk2 levels at high chelator concentrations prevent the formation of the cyclin A-cdk2 complex that is also essential for G1/S progression.35 Previous studies27showed that DFO could reduce the expression of cdk1 that is vital for the G2/M transition.39 Hence, inhibition of cdk1 and cdk2 expression may explain why a G1/S arrest, and sometimes a G2/M arrest, can be observed after exposure to chelators.19 67

Effect of chelators on expression of cell-cycle inhibitors

It was significant that though chelators induced a marked increase in WAF1 and GADD45 mRNA transcripts (Figure6),20 this did not lead to an appreciable increase in their protein levels (Figure 7), possibly suggesting that chelators prevent translation. Indeed, DFO inhibits the formation of hypusine, a component of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A.68 However, this would not explain the increase in cyclin E (Figures 2, 3) or the transferrin receptor after incubation with chelators.27 44

Considering the paradox between transcription and translation ofWAF1 mRNA, it is of interest to discuss a study by Ashcroft et al,61 in which DFO, cisplatin, and actinomycin D increased p53 protein levels in cells with wild-type p53. However, only cisplatin and actinomycin D increased p21Cip1 protein levels, despite increased mRNA levels of this molecule after exposure to all agents.61 The failure of DFO to induce translation of WAF1 mRNA was not adequately explained by these authors.61 However, it is clear these results are similar to ours, except that SK-N-MC cells do not have functional p53.46 47 Failure to translate WAF1 mRNA may be another factor inducing dysregulation of the cell cycle after exposure to chelators (Figure 9).

We thank the members of our group and Dr Paul Wilson for their suggestions concerning the manuscript before submission.

Supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council, by an Australian Research Council Large Grant, and by The Heart Research Institute.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Des R. Richardson, Iron Metabolism and Chelation Group, The Heart Research Institute, 145 Missenden Rd, Camperdown, Sydney, New South Wales, 2050 Australia; e-mail:d.richardson@hri.org.au.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal