Abstract

The use of tumor cells as vaccines in cancer immunotherapy is critically dependent on their capacity to initiate and amplify tumor-specific immunity. Optimal responses may require the modification of the tumor cells not only to increase their immunogenicity but also to improve their ability to recruit effector cells to the tumor sites or sites of tumor antigen exposure. It has been reported that CD40 cross-linking of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cells significantly increases their immunogenicity and allows the generation and expansion of autologous antileukemia cytotoxic T lymphocytes. This study demonstrates that the CD40 ligation of these tumor cells also induces the secretion of the CC-chemokines MDC and TARC. Supernatants from malignant cells cultured in the presence of sCD40L promote the migration of activated T cells that express CCR4, the common specific receptor for MDC and TARC. More importantly, the supernatants from CD40-stimulated tumor cells also support the transendothelial migration of autologous CCR4+ antileukemia T cells. Therefore, the results demonstrate that the delivery to leukemia cells of a single physiologic signal, that is, CD40 cross-linking, simultaneously improves tumor cell immunogenicity and induces potent chemoattraction for T cells.

Introduction

Successful T-cell–mediated immunity requires tightly regulated trafficking of T cells. First, naı̈ve T cells must enter specialized microenvironments where antigenic exposure occurs. Second, these primed T cells must recirculate to be continuously available for potential antigenic rechallenge. To achieve these critical functions, T cells respond to chemotactic molecules, termed chemokines,1 that signal through at least 15 different G protein–coupled 7 transmembrane domain molecules, the so-called chemokine receptors (CRs).1-3 The trafficking of specific subpopulations of T cells is regulated by their differential expression of CRs, thus defining particular patterns of chemokine reactivity. It has been shown that the antigenic experience, state of activation, and polarization of T cells defines the CRs that they express.4,5 This is best exemplified by the mutually exclusive expression of some CRs by Th1 and Th2 cells.6

Activated, antigen-primed T cells display a distinct CR phenotype that includes the expression of CCR1, CCR3, CCR4, CCR7, CCR8, CXCR3, and CX3CR1.7-9 Among them, CCR4, the receptor for the chemokines MDC/CCL22 and TARC/CCL17,1,10,11 has been shown to be constitutively expressed by CD4+ Th2 cells7,8,12 and up-regulated following TCR and CD28 engagement.13 In contrast, CD4+ Th1 cells do not constitutively express CCR4, but can be induced to express it following activation.13 Importantly, the pattern and regulation of CR expression by antigen-activated CD8+ T cells overlap with CD4+ T cells.13 Therefore, CCR4 is thought to play a critical role in attracting both CD4+- and CD8+-activated T cells to sites of antigenic challenge or to specialized microenvironments of lymphoid tissues.13

Transduction of chemokine genes alone or in combination with other immunoregulatory genes has been shown to significantly improve the generation of antitumor immunity in several animal model systems. Coexpression of a T-cell chemokine, lymphotactin, and interleukin-2 (IL-2) potentiated antitumor responses in vivo by recruiting both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in a murine leukemia model.14 In this model, transduction of lymphotactin alone also improved the antitumor effect. Glioma cells transduced with the chemokine MCP-1/CCL2 increased the antitumor response in a murine brain tumor model.15 These studies demonstrated that chemokines could improve the generation of antitumor immunity. However, it is not known whether primary tumor cells constitutively produce chemokines or whether tumor cells can be physiologically activated to secrete T-cell chemoattractants.

We have previously shown that human precursor B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cells can be induced to become functional tumor antigen-presenting cells (APCs), by CD40 cross-linking.16 We have used this strategy to generate autologous antileukemia-specific T cells that are capable of lysing primary tumor cells.17 18 However, it is not known whether these activated ALL cells would have the capacity to attract significant numbers of antigen-specific T cells. Here, we show that ALL cells do not constitutively express significant levels of chemokines. CD40 cross-linking of these tumor cells induces the secretion of high levels of the chemokines MDC and TARC, which mediate the chemoattraction of both antitumor-specific effector T cells. These findings suggest that the stimulation of malignant cells via physiologic signals can improve both their capacity to mobilize tumor-specific T cells and their antigen-presenting function. Both effects could potentiate their efficacy as a tumor cell vaccine.

Materials and methods

Tumor cells

Malignant B-cell precursors were obtained from the bone marrow or peripheral blood of B-ALL patients with extensive leukemia involvement (> 90% of mononuclear cells). Appropriate informed consent and Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for all sample collections. Samples were enriched by density centrifugation over Ficoll-Hypaque. When indicated, B-lineage cells were purified by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) (> 99% purity).

CD40 stimulation of leukemia cells

Leukemia B cells were stimulated by CD40 cross-linking as previously reported.16,17 Briefly, leukemia cells were cultured in the serum-free medium AIM V (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) in the presence of 30% (vol/vol) soluble CD40L (sCD40L). Malignant cells were cultured at variable cell densities (3 × 106-3 × 107 cells/mL), and cells and supernatants were harvested at day 3. The sCD40L was obtained from high-density culture of a producing cell line19 grown in AIM V using the Integra Celline system (Integra Biosciences, Ijamsville, MD). The sCD40L-producing cells were kindly provided by Dr P. Lane (Oxford University, United Kingdom). Alternatively, ALL cells were CD40 cross-linked using 200 ng/mL of a recombinant CD40L-FLAG-tag fusion protein (Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, CA) supplemented with 1 μg/mL “CD40L enhancer” (Alexis Biochemicals).

Generation of antileukemia-specific T-cell lines

Autologous antileukemia-specific T-cell lines were generated and expanded as previously described.17 18 Briefly, bulk cultures of bone marrow were initiated in the presence of CD40L, and cultured for cycles of expansion (with IL-2) and restimulation (with CD40-stimulated tumor cells) for up to 30 days.

Activated T cells

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy individuals were separated by density centrifugation and 2-hour adhesion to plastic. T cells were purified from the nonadherent fraction by negative selection (depletion of CD19+, CD56+, CD11b+, and CD14+ cells) and activated by repetitive stimulation using monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) anti-CD3 and anti-CD2820 plus IL-4 (5 ng/mL). Supernatants from these T cells were used as positive controls for MDC and TARC activity.

Chemokines and supernatants with chemoattractant activity

Recombinant MDC and TARC were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) and Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ). Chemokines were used at the concentrations indicated. Supernatants from high-density cultures of leukemia cells were collected after 3 days of culture at 37°C, 5% CO2, in AIM V medium. All supernatants were filtered and frozen.

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction

RNA was extracted from 1 to 2 × 106 cells using RNAzol (Biotecx Laboratories, Houston, TX) following the manufacturer's instructions. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was prepared at 42°C using a reverse transcription (RT) mix containing Superscript II (Life Technologies). The enzyme was inactivated for 2 minutes at 95°C. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of cDNA samples was carried out using the primers whose sequences are shown in Table 1. All the primer pairs allowed for the distinction between expressed messenger RNA (mRNA) and genomic DNA. Positive controls for each chemokine have been used. All reactions were carried out in a PerkinElmer thermocycler (PerkinElmer, Foster City, CA).

Primers sequences

| Gene . | Primer . | Sequence . |

|---|---|---|

| MDC/CCL22 | Fw | ACTGCACTCCTGGTTGTCCTC |

| Rev | CACGGTCATCAGAGTAGGCTC | |

| TARC/CCL17 | Fw | ATGGCCCCACTGAAGATGCTGG |

| Rev | TCAAGACCTCTCAAGGCTTTGC | |

| MIP-1α/CCL3 | Fw | CTGCTGCTTCAGCTACACCTCC |

| Rev | ACCCCTCAGGCACTCAGCTCC | |

| RANTES/CCL5 | Fw | TATTCCTCGGACACCACAC |

| Rev | GCTCATCTCCAAAGAGTTGA | |

| LARC/CCL20 | Fw | TTGCTCCTGGCTGCTTTGATG |

| Rev | TCTTTCTGTTCTTGGGCTATG | |

| SLC/CCL21 | Fw | AGCCTCCTTATCCTGGTTCTG |

| Rev | TTACAAGGAAGAGGTGGGGTG | |

| ELC/CCL19 | Fw | ATGGCCCTGCTACTGGCCCTC |

| Rev | GCTCCCTCTGCACGGTCATAG | |

| I-309/CCL1 | Fw | GTGGTGAGCTCTTAGCTTCACC |

| Rev | ACCAAGCAGATCCTCTGTGACC | |

| TECK/CCL25 | Fw | AACCTGTGGCTCCTGGCCTGC |

| Rev | GGCTCACAGTCCTGAATTAGC | |

| PARC/CCL18 | Fw | TGCCCTCCTTGTCCTCGTCTG |

| Rev | GAAGGGAAAGGGGAAAGGATG | |

| MCP-1/CCL2 | Fw | ATGAAAGTCTCTGCCGCCCTTC |

| Rev | AGTCTTCGGAGTTTGGGTTTG | |

| MCP-2/CCL8 | Fw | CCAAGATGAAGGTTTCTGCAG |

| Rev | GTCCAGATGCTTCATGGAATC | |

| MCP-3/CCL7 | Fw | CCTCACCCTCCAACATGAAAG |

| Rev | GTTTTCTTGTCCAGGTGCTTC | |

| IL-8/CXCL8 | Fw | ATGACTTCCAAGCTGGCCGTGG |

| Rev | TCTGGCAACCCTACAACAGACC | |

| IP-10/CXCL10 | Fw | AACTGCGATTCTGATTTGCTG |

| Rev | TTGGAAGATGGGAAAGGTGAG | |

| MIG/CXCL9 | Fw | TTGCTGGTTCTGATTGGAGTG |

| Rev | GTTGTGAGTGGGATGTGGTTG | |

| SDF-1/CXCL12 | Fw | ATGAACGCCAAGGTCGTGGTCG |

| SDF-1α | Rev | AAGTCCTTTTTGGCTGTTGTGC |

| SDF-1β | Rev | TGACCCTCTCACATCTTGAACC |

| BCA-1/CXCL13 | Fw | GCCGCCACCATGAAGTTCATCTCGACATCTC |

| Rev | TAGTGGAAATATCAGCATCAGG | |

| Fractalkine/CX3CL1 | Fw | CCACCTTCTGCCATCTGACTG |

| Rev | CCATCTCTCCTGCCATCTTTC | |

| Actin | Fw | GTGGGGCGCCCCAGGCACCA |

| Rev | CTCCTTAATGTCACGCACGATTTC |

| Gene . | Primer . | Sequence . |

|---|---|---|

| MDC/CCL22 | Fw | ACTGCACTCCTGGTTGTCCTC |

| Rev | CACGGTCATCAGAGTAGGCTC | |

| TARC/CCL17 | Fw | ATGGCCCCACTGAAGATGCTGG |

| Rev | TCAAGACCTCTCAAGGCTTTGC | |

| MIP-1α/CCL3 | Fw | CTGCTGCTTCAGCTACACCTCC |

| Rev | ACCCCTCAGGCACTCAGCTCC | |

| RANTES/CCL5 | Fw | TATTCCTCGGACACCACAC |

| Rev | GCTCATCTCCAAAGAGTTGA | |

| LARC/CCL20 | Fw | TTGCTCCTGGCTGCTTTGATG |

| Rev | TCTTTCTGTTCTTGGGCTATG | |

| SLC/CCL21 | Fw | AGCCTCCTTATCCTGGTTCTG |

| Rev | TTACAAGGAAGAGGTGGGGTG | |

| ELC/CCL19 | Fw | ATGGCCCTGCTACTGGCCCTC |

| Rev | GCTCCCTCTGCACGGTCATAG | |

| I-309/CCL1 | Fw | GTGGTGAGCTCTTAGCTTCACC |

| Rev | ACCAAGCAGATCCTCTGTGACC | |

| TECK/CCL25 | Fw | AACCTGTGGCTCCTGGCCTGC |

| Rev | GGCTCACAGTCCTGAATTAGC | |

| PARC/CCL18 | Fw | TGCCCTCCTTGTCCTCGTCTG |

| Rev | GAAGGGAAAGGGGAAAGGATG | |

| MCP-1/CCL2 | Fw | ATGAAAGTCTCTGCCGCCCTTC |

| Rev | AGTCTTCGGAGTTTGGGTTTG | |

| MCP-2/CCL8 | Fw | CCAAGATGAAGGTTTCTGCAG |

| Rev | GTCCAGATGCTTCATGGAATC | |

| MCP-3/CCL7 | Fw | CCTCACCCTCCAACATGAAAG |

| Rev | GTTTTCTTGTCCAGGTGCTTC | |

| IL-8/CXCL8 | Fw | ATGACTTCCAAGCTGGCCGTGG |

| Rev | TCTGGCAACCCTACAACAGACC | |

| IP-10/CXCL10 | Fw | AACTGCGATTCTGATTTGCTG |

| Rev | TTGGAAGATGGGAAAGGTGAG | |

| MIG/CXCL9 | Fw | TTGCTGGTTCTGATTGGAGTG |

| Rev | GTTGTGAGTGGGATGTGGTTG | |

| SDF-1/CXCL12 | Fw | ATGAACGCCAAGGTCGTGGTCG |

| SDF-1α | Rev | AAGTCCTTTTTGGCTGTTGTGC |

| SDF-1β | Rev | TGACCCTCTCACATCTTGAACC |

| BCA-1/CXCL13 | Fw | GCCGCCACCATGAAGTTCATCTCGACATCTC |

| Rev | TAGTGGAAATATCAGCATCAGG | |

| Fractalkine/CX3CL1 | Fw | CCACCTTCTGCCATCTGACTG |

| Rev | CCATCTCTCCTGCCATCTTTC | |

| Actin | Fw | GTGGGGCGCCCCAGGCACCA |

| Rev | CTCCTTAATGTCACGCACGATTTC |

Fw indicates forward; Rev, reverse.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

The production of the chemokines MDC, TARC, MIP-1α, and RANTES was quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). For MDC, sandwich ELISA using a murine anti–human MDC mAb (252Y) and a chicken anti-MDC polyclonal antibody (generously provided by Dr P. A. Gray, ICOS, Bothell, WA) was performed as previously described.7 Immunoreactivity was evaluated using peroxidase-conjugated donkey antichicken antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch Lab, West Grove, PA). Quantification of TARC, MIP-1α, and RANTES was performed using commercially available antibody pairs (capture and detection) matched for construction of ELISA (R&D Systems), following the manufacturer's instructions. The lower limit of detection of the ELISA was 0.25 ng/mL for MDC, 0.13 ng/mL for TARC, 15 pg/mL for MIP-1α, and 31 pg/mL for RANTES.

Phenotypic analysis and cell sorting

Expression of cell surface molecules was determined by flow cytometry using standard methodology. Fc receptors were blocked by incubation with mouse Ig prior to the addition of the specific mAbs. The mAbs used were unconjugated CCR4 and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated anti-CCR4, which were produced by us12; phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated anti-CD8, anti-CD45RO (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), and anti–granzyme B (Caltag, Burlingame, CA); FITC–anti-CD3 and PE–anti-CD19 (kindly provided by Coulter, Miami, FL). FITC-conjugated goat anti–mouse Ig (Southern Biotechnologies, Birmingham, AL) was used as secondary reagent. Irrelevant isotype-matched antibodies were used as negative controls. Appropriate controls were used to determine optimal voltage settings and electronic subtraction for the spectral fluorescence overlap correction. Samples were analyzed in a Coulter Elite or XL flow cytometer and data were acquired in listmode files. At least 5000 positive events were measured for each sample. For cell sorting, CD19-labeled cells were concentrated, filtered, and purified using a high-speed sorting (Moflow, Fort Collins, CO).

Calcium mobilization assay

For the calcium flux experiments, Indo-1 am(Molecular Probes, Eugene OR) was used as fluorescent Ca++indicator following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, activated T cells were loaded with Indo-1 for 45 minutes at room temperature. After 2 washes, cells were resuspended in AIM V for flow cytometry analysis using a Coulter Elite. For the analysis of the effect of MDC and TARC, these chemokines were added at 100 to 500 ng/mL at 30 seconds of acquisition. To test the effect of supernatants from cultures of CD40-stimulated leukemia cells, the activated T cells were initially resuspended in a smaller volume and supernatant (75% vol/vol) was added at 30 seconds of the cell acquisition. Events were acquired for a total of 5 minutes. Supernatants were concentrated to approximately a third of the initial volume prior to their use. Both negative (medium alone and 10 mM EDTA) and positive (Ionomycin) controls were used (data not shown).

Chemotaxis assay

Chemotaxis assays were performed using the Transwell system (Costar, Cambridge, MA). The transendothelial chemotaxis assay was performed as previously described,21 22 using primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) as the endothelial layer. Briefly, 5 × 104 to 1 × 105endothelial cells were seeded on 6.5-mm or 24-mm diameter microporous Transwell inserts and cultured at 37°C to establish the endothelial layers (4-7 days or until monolayer confluence was reached). To assess endothelial cell confluence and the establishment of monolayers, sample inserts were stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa and visualized by microscopy. For the chemotaxis assay, the medium used was AIM V. Supernatants were used at 100% vol/vol, whereas recombinant chemokines (MDC or TARC) were added to the assay medium and distributed on cluster plates (lower compartment of chemotaxis system) and warmed for 15 minutes at 37°C. Following removal of culture medium, the Transwell inserts covered with the endothelial monolayer were transferred to the prewarmed cluster plates. Activated T cells or antileukemia-specific T cells (5 × 104 cells for 6.5-mm inserts; 1 to 2 × 106 cells for 24-mm inserts) were placed into the Transwell inserts (upper compartment of the chemotaxis system). The plates were incubated for 6 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2. A control condition without chemokines or supernatant was also included. After the 6-hour period, the Transwell inserts were removed and all the liquid accumulated in the lower compartment, including the liquid on the lower surface of the insert, was carefully recovered. All migrated cells were collected and then counted by flow cytometry. The flow cytometer settings were determined prior to the acquisition of the migrated cells using samples of the input population. The migration percentage was calculated by dividing the number of migrated cells by the total number of input cells. When indicated, the migrated cells were used for flow cytometry.

Checkerboard analysis was performed by placing recombinant TARC and MDC or supernatants in the upper chamber of the Transwell system, to prevent the establishment of a chemokine gradient between chambers.

In separate experiments, neutralizing antibodies anti-MDC (10 μg/mL, R&D Systems) or anti-TARC (10 μg/mL, R&D Systems), or both, were added to the supernatants, in the lower compartments, prior to the chemotaxis assay.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance between the treatment groups was determined using the t test.

Results

CD40 cross-linking of leukemia cells induces the secretion of the chemokines MDC and TARC

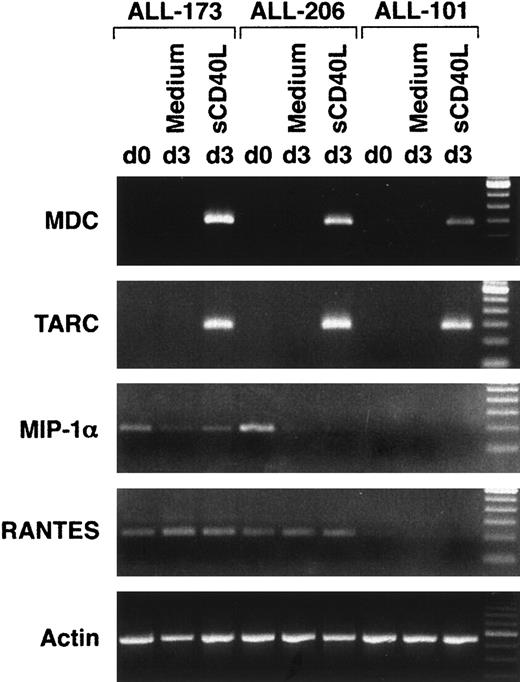

The capacity to attract antigen-specific T cells to a tumor microenvironment or to sites of tumor-antigen exposure is required for the development of an effective antitumor immune response. Using B-cell ALL as a human tumor model, we sought to determine whether these tumor cells produced chemokines, particularly T-cell chemoattractants. As shown in Table 2, no chemokines could be detected in primary leukemia cells (n = 18) with the exception, in some patients, of faint bands corresponding to mRNA for MIP-1α and RANTES (Figure 1). Based on our previous evidence that CD40 cross-linking on both normal and neoplastic B cells markedly improved their immunogenicity, we examined whether this signal would alter their chemokine expression profile. No increase in the level of expression of either MIP-1α or RANTES was observed in malignant B-cell precursors (Figure 1). In contrast, CD40 ligation induced strong expression of both the CC-chemokines MDC and TARC (Table2, Figure 1). Kinetic studies showed that both MDC and TARC were maximally expressed by 24 hours (data not shown) and maintain levels of expression on day 3. No differences in the malignant phenotype (ie, differentiation or change in clonality) of these tumor cells were observed following CD40 ligation (Cardoso et al16 and data not shown).

Messenger RNA expression of chemokines by malignant B-cell precursors (n = 18 patients)

| . | Pre-B ALL unstimulated . | Pre-B ALL CD40-stimulated . |

|---|---|---|

| C-C Chemokine | ||

| MDC | − | + |

| TARC | − | + |

| MIP-1α | + | + |

| RANTES | + | + |

| LARC | − | − |

| SLC | − | − |

| ELC | − | − |

| I-309 | − | − |

| TECK | − | − |

| PARC | − | − |

| MCP-1 | − | − |

| MCP-2 | − | − |

| MCP-3 | − | − |

| C-X-C Chemokines | ||

| IL-8 | − | − |

| IP-10 | − | − |

| MIG | − | − |

| SDF-1α | − | − |

| SDF-1α | − | − |

| BCA-1 | − | − |

| C-X3-C Chemokine | ||

| Fractalkine | − | − |

| . | Pre-B ALL unstimulated . | Pre-B ALL CD40-stimulated . |

|---|---|---|

| C-C Chemokine | ||

| MDC | − | + |

| TARC | − | + |

| MIP-1α | + | + |

| RANTES | + | + |

| LARC | − | − |

| SLC | − | − |

| ELC | − | − |

| I-309 | − | − |

| TECK | − | − |

| PARC | − | − |

| MCP-1 | − | − |

| MCP-2 | − | − |

| MCP-3 | − | − |

| C-X-C Chemokines | ||

| IL-8 | − | − |

| IP-10 | − | − |

| MIG | − | − |

| SDF-1α | − | − |

| SDF-1α | − | − |

| BCA-1 | − | − |

| C-X3-C Chemokine | ||

| Fractalkine | − | − |

CD40-stimulated cells correspond to tumor cells cultured for 3 days in the presence of sCD40L.

CD40 cross-linking of leukemia cells induces the expression of mRNA for the chemokines MDC and TARC.

CD19+ leukemia cells were sorted using a high-speed sorter to obtain near 100% purity. Three representative patients, of 18 tested, are shown. Tumor cells were cultured in AIM V medium in the presence or absence of sCD40L, for 3 days.

CD40 cross-linking of leukemia cells induces the expression of mRNA for the chemokines MDC and TARC.

CD19+ leukemia cells were sorted using a high-speed sorter to obtain near 100% purity. Three representative patients, of 18 tested, are shown. Tumor cells were cultured in AIM V medium in the presence or absence of sCD40L, for 3 days.

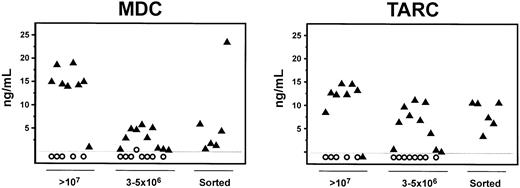

To determine whether MDC, TARC, MIP-1α, and RANTES were secreted, we examined the supernatants of leukemia cells cultured either in medium alone or stimulated with sCD40L (Figure2). The supernatants were generated using 3 different conditions: (1) high density of leukemia cells (>107 cells/mL), (2) intermediate density of leukemia cells (3 to 5 × 106 cells/mL), and (3) FACS-sorted CD19+ leukemia cells (3 to 5 × 106cells/mL). Chemokines were measured by ELISA. As shown in Figure 2, CD40-stimulated tumor cells produced both MDC and TARC (triangles) at levels that parallel with cell density. Similar results were obtained when CD40 cross-linking was induced using sCD40L or a purified CD40L-FLAG-tag fusion protein (data not shown). In contrast, leukemia cells cultured in control medium did not produce detectable levels of these chemokines (circles) regardless of cell density. Confirmation that MDC and TARC were secreted by the tumors cells was obtained by demonstrating that highly purified (> 99%) malignant cells sorted from heavily infiltrated bone marrow produced high levels of both MDC and TARC (Figure 2), which were equivalent to those detected in supernatants produced from unpurified ALL specimens. Conversely, neither MIP-1α nor RANTES was detected on supernatants of leukemia cells cultured in the presence of sCD40L or of control medium (data not shown). Moreover, no significant levels of MIP-1α or RANTES were detectable in bone marrow plasma from ALL patients (data not shown).

CD40 cross-linking of tumor cells induces the secretion of the chemokines MDC and TARC.

Leukemia cells were cultured in control medium (open circles) or sCD40L (solid triangles) for 3 days. Supernatants were collected from nonpurified leukemia cells cultured at 107 cells/mL (or more) or at 3 to 5 × 106 cells/mL, or from leukemia cells purified by sorting and cultured at 3 × 106cells/mL. The dotted lines indicate the limit of detection (LD) of the ELISA, which was 0.25 ng/mL for MDC and 0.13 ng/mL for TARC. For the purpose of clarity, the supernatants in which MDC and TARC were below the detection limit are represented as below the 0 level.

CD40 cross-linking of tumor cells induces the secretion of the chemokines MDC and TARC.

Leukemia cells were cultured in control medium (open circles) or sCD40L (solid triangles) for 3 days. Supernatants were collected from nonpurified leukemia cells cultured at 107 cells/mL (or more) or at 3 to 5 × 106 cells/mL, or from leukemia cells purified by sorting and cultured at 3 × 106cells/mL. The dotted lines indicate the limit of detection (LD) of the ELISA, which was 0.25 ng/mL for MDC and 0.13 ng/mL for TARC. For the purpose of clarity, the supernatants in which MDC and TARC were below the detection limit are represented as below the 0 level.

Secreted MDC and TARC are functional and induce the migration of activated T cells

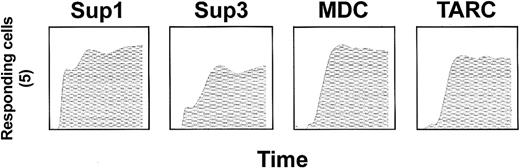

To determine whether MDC and TARC produced by CD40-stimulated ALL cells were functional, supernatants were tested for their capacity to induce the mobilization of calcium in activated T cells, as well as for their capacity to induce the migration of activated T cells, both known to be targets of these 2 chemokines.12 23 T cells were activated with a combination of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAbs to mimic both cognitive and costimulatory signals, in the presence of IL-4 to skew these cells to a Th2 phenotype. As shown in Figure3, MDC- and TARC-containing supernatants (Sup1 and Sup3) from cultures of CD40-stimulated tumor cells at high density induced the mobilization of Ca++. In contrast, no calcium flux was induced by the addition of supernatants from ALL cells cultured in medium alone (data not shown). The expression of functional receptors for these chemokines by the activated T cells was demonstrated by their mobilization of Ca++ in response to both recombinant MDC and TARC (Figure 3).

Calcium mobilization.

Supernatants from CD40-stimulated tumor cells (Sup1 and Sup3) induce calcium mobilization on activated T cells. Supernatants were concentrated and used at 75% vol/vol. Recombinant MDC and TARC were used at 500 ng/mL. The x-axis indicates time (300 seconds). The y-axis indicates percentage of responding cells calculated after subtraction of background levels.

Calcium mobilization.

Supernatants from CD40-stimulated tumor cells (Sup1 and Sup3) induce calcium mobilization on activated T cells. Supernatants were concentrated and used at 75% vol/vol. Recombinant MDC and TARC were used at 500 ng/mL. The x-axis indicates time (300 seconds). The y-axis indicates percentage of responding cells calculated after subtraction of background levels.

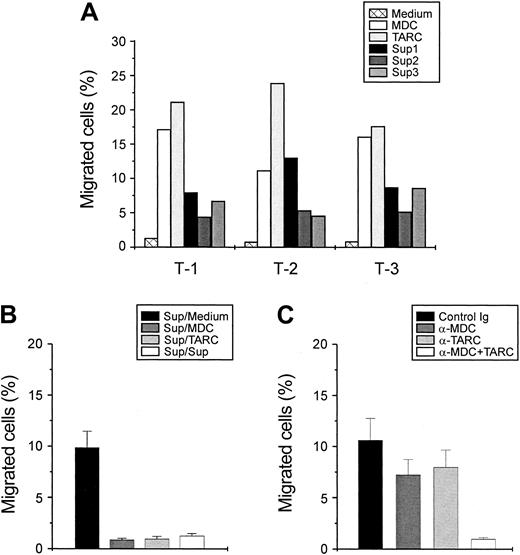

We next sought to determine whether supernatants from CD40-stimulated tumor cells could induce the migration of activated T cells. As shown in Figure 4A, the migration induced by these supernatants from CD40-stimulated cells was significantly higher than that induced by control culture supernatants (P < .01). As expected, both recombinant MDC (P < .01) and TARC (P < .001) efficiently promoted the migration of activated T cells. The supernatant-induced migration was considerably lower than that induced by recombinant MDC or TARC because the total amount of these chemokines present in the supernatants was lower than the optimal dose of chemokine necessary to induce optimal migration. A checkerboard analysis was performed to confirm that the migration of activated T cells was induced through CCR4, the common receptor for MDC and TARC. In this assay, recombinant MDC and TARC placed in the upper chamber of the Transwell system prevented the migration of T cells induced by the supernatants placed in the lower chamber (Figure 4B). This migration was also abrogated by the addition of supernatants to the upper chamber of the Transwell (Figure 4B). These results also support the conclusion that significant migration occurs only when a gradient exists between the 2 compartments and, therefore, is directional (chemotaxis) rather than random (chemokinesis).

Transendothelial migration.

(A) Supernatants (Sup) from CD40-stimulated tumor cells induce transendothelial migration of activated T cells. Supernatants obtained from cultures of leukemia cells from 3 representative patients were used at 100% vol/vol. Activated T cells were derived from 3 different donors (T-1 to T-3). Recombinant MDC and TARC were used at 500 ng/mL. Data are expressed as percentage of migrated cells. (B) The migration induced by supernatant of CD40-stimulated ALL cells is inhibited by disruption of chemokine gradient, by the addition of MDC, TARC, or supernatants to the Transwell upper chamber. Results represent mean ± SE of 3 individual experiments. Legend indicates the supernatant placed in the lower chamber followed by reagent placed in the upper chamber. (C) A combination of neutralizing anti-MDC and anti-TARC antibodies abrogates the migration induced by supernatants of CD40-stimulated ALL cells. Results represent mean ± SE of 3 individual experiments.

Transendothelial migration.

(A) Supernatants (Sup) from CD40-stimulated tumor cells induce transendothelial migration of activated T cells. Supernatants obtained from cultures of leukemia cells from 3 representative patients were used at 100% vol/vol. Activated T cells were derived from 3 different donors (T-1 to T-3). Recombinant MDC and TARC were used at 500 ng/mL. Data are expressed as percentage of migrated cells. (B) The migration induced by supernatant of CD40-stimulated ALL cells is inhibited by disruption of chemokine gradient, by the addition of MDC, TARC, or supernatants to the Transwell upper chamber. Results represent mean ± SE of 3 individual experiments. Legend indicates the supernatant placed in the lower chamber followed by reagent placed in the upper chamber. (C) A combination of neutralizing anti-MDC and anti-TARC antibodies abrogates the migration induced by supernatants of CD40-stimulated ALL cells. Results represent mean ± SE of 3 individual experiments.

To positively demonstrate that the T-cell chemotactic activity of the supernatants was specifically mediated by MDC and TARC, experiments were performed using neutralizing antibodies for these chemokines. The use of a single antibody resulted in partial inhibition of the T-cell migration (Figure 4C; 31.9% ± 2.7% inhibition with anti-MDC and 25.1% ± 7.5% with anti-TARC). In contrast, the combination of both neutralizing antibodies completely abrogated the T-cell migration induced by the supernatants (Figure 4C). These results demonstrate that MDC and TARC are the mediators of the T-cell chemotactic activity present in the supernatants from CD40-stimulated ALL cells.

Antitumor-specific T-cell lines express CCR4 and migrate through endothelium in response to tumor cell–secreted MDC and TARC

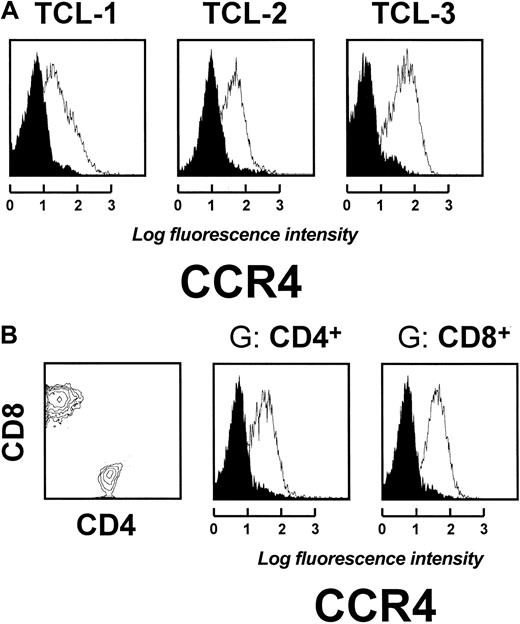

Because MDC and TARC share CCR4 as common receptor,10 11 we sought to determine whether antitumor-specific T-cell lines generated from leukemia patients express this molecule. In all patients tested, CCR4 was detected in the autologous ex vivo generated antitumor-specific T-cell lines (Figure5A). This expression was also confirmed at mRNA level (data not shown). The expression of CCR4 varied from 45% to 89% of these T cells and was detected in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Figure 5B). As control, activated Th2-skewed T cells were tested and found to express CCR4 (data not shown).

Antitumor-specific autologous T cells express CCR4.

(A) Data represents T-cell lines (TCL) from 3 representative patients, of 5 tested. (B) Both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells express CCR4. Fluorescence intensity is shown on the x-axis. Blank areas represent fluorescence distribution of the molecules indicated and filled areas represent that of isotype-matched control antibodies. The cell number is shown on the y-axis.

Antitumor-specific autologous T cells express CCR4.

(A) Data represents T-cell lines (TCL) from 3 representative patients, of 5 tested. (B) Both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells express CCR4. Fluorescence intensity is shown on the x-axis. Blank areas represent fluorescence distribution of the molecules indicated and filled areas represent that of isotype-matched control antibodies. The cell number is shown on the y-axis.

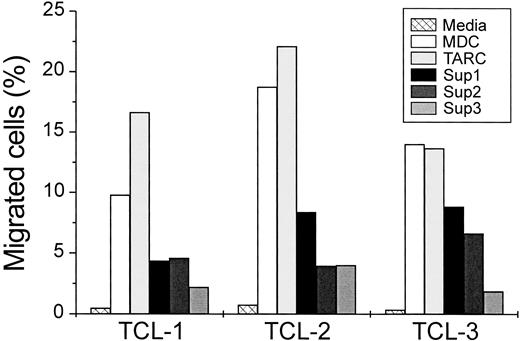

We next sought to determine whether the antileukemia T-cell lines were capable of migration through HUVEC layers in response to the supernatants from CD40-stimulated tumor cells or recombinant chemokines. As shown in Figure6, antileukemia T cells were capable of transendothelial migration in response to all the supernatants from CD40-stimulated tumor cells. This transmigration varied from 1.9% to 8.8% of the input T cells and was significantly higher (P < .01) in comparison to control conditions, for which the migration varied from 0.35% to 0.76%. The migration of these T cells to recombinant MDC (P < .001) and TARC (P < .0001) was even more robust (Figure 6). No significant migration of purified naı̈ve T cells was observed in response to these supernatants or to recombinant chemokines (data not shown). Antitumor-specific T cells showed a significant response to optimal doses of recombinant MDC and TARC in all cases tested (Figure6). Addition of recombinant MDC and TARC to the Transwell insert inhibited the T-cell migration induced by the CD40-stimulated leukemia cell supernatants (data not shown).

Antitumor-specific T cells migrate through endothelium in response to supernatants from CD40-stimulated tumor cells as well as to recombinant MDC and TARC.

MDC and TARC were used at 500 ng/mL. Supernatants were produced as described. Antitumor T-cell lines (TCL) were from 3 representative patients and were generated as described.17 Data are expressed as percentage of migrated cells.

Antitumor-specific T cells migrate through endothelium in response to supernatants from CD40-stimulated tumor cells as well as to recombinant MDC and TARC.

MDC and TARC were used at 500 ng/mL. Supernatants were produced as described. Antitumor T-cell lines (TCL) were from 3 representative patients and were generated as described.17 Data are expressed as percentage of migrated cells.

To determine the characteristics of the cells migrating through the endothelium, flow cytometric analysis of both the input and the migrated T cells was performed. The phenotypic profile of the migrated antitumor T cells was not significantly different from that of the input population (Figure 7). In fact, both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells migrated in response to the supernatant from the CD40-stimulated tumor cells, and the migrated cells were mostly antigen-experienced CD8+CD45RO+ T cells, expressing the cytotoxicity-mediator granzyme B (Figure 7).

Phenotypic characterization of antileukemia T cells migrated through endothelium in response to supernatant from CD40-stimulated tumor cells.

Data represent both input (upper section) and migrated cell populations after the 6-hour chemotaxis assay through HUVEC endothelial cell layer (lower section). Fluorescence intensity is shown on the x-axis. Blank areas represent fluorescence distribution of the molecules indicated and filled areas represent that of isotype-matched control antibodies. The cell number is shown on the y-axis.

Phenotypic characterization of antileukemia T cells migrated through endothelium in response to supernatant from CD40-stimulated tumor cells.

Data represent both input (upper section) and migrated cell populations after the 6-hour chemotaxis assay through HUVEC endothelial cell layer (lower section). Fluorescence intensity is shown on the x-axis. Blank areas represent fluorescence distribution of the molecules indicated and filled areas represent that of isotype-matched control antibodies. The cell number is shown on the y-axis.

Discussion

A compelling rationale for the use of intact tumor cells as vaccines is that they have the potential to display the widest range of tumor antigens to the host's T-cell repertoire and, consequently, mobilize a larger number of tumor-reactive T cells.24,25Because chemokines mediate the trafficking of different cell types and play important roles in regulating leukocyte movements during immune and inflammatory reactions,2,26 they may also play critical roles in the host's immune responses to tumors. The expression and modulation of chemokines, such as those regulating the trafficking of effector immune cells or tumor cells vaccines, may thereby be essential for the design of effective immunotherapeutic strategies. Here, we demonstrate that primary leukemia cells do not express significant levels of T-cell chemoattractants but can be induced following CD40 ligation to secrete the CC-chemokines MDC and TARC. Importantly, supernatants from CD40-stimulated tumor cells support the transendothelial migration of autologous antileukemia T cells, which express CCR4, the common specific receptor for MDC and TARC. Because we have previously reported that CD40 cross-linking of ALL cells significantly increases their immunogenicity and allows the generation and expansion of autologous antileukemia cytotoxic T lymphocytes,17 18 these findings demonstrate that the delivery to leukemia cells of a single physiologic signal, that is, CD40 cross-linking, simultaneously improves tumor cell immunogenicity and induces potent T-cell chemoattraction.

A major obstacle to the use of tumor cells as vaccines is their poor immunogenicity.16,27,28 To increase the APC function of tumor cells and induce effective tumor-specific responses, different approaches have been used such as the insertion or induction of major histocompatibility complex molecules, adhesion molecules, costimulatory molecules, and cytokines.28-35 Considerably fewer studies have been reported attempting to induce tumor immunity by using chemokine genes, alone or in combination with other immunomodulators. In general, these studies have shown that the coexpression of a chemokine and an immunostimulatory molecule is more effective in inducing the regression of established tumors and conferring protection to tumor rechallenge.14,36 The effect of chemokines alone was found to be more variable, probably reflecting differences between tumor models and in the activity of the chemokines.14,15,36 Chemokines have also been used in other vaccination approaches, such as endogenous peptide-based strategies37 or as part of a chemokine/tumor antigen fusion protein.38 Despite successes in animal tumor models, it remains to be determined whether the use of chemokines is effective in inducing antitumor immunity in humans.

The potential use of chemokines to augment antitumor immunity raises several issues. First, for most tumors, the profile of chemokines produced by the malignant cells and the cells of the tumor microenvironment is unknown. Second, it is unclear whether the induction of endogenous secretion or exogenous administration is the most effective way to deliver chemokines. Also, it is not known whether all tumor cells can be modified via physiologic signals to produce relevant chemokines. Third, it has been suggested that chemokines may play important roles in tumor development, and it has been demonstrated that chemokines secreted by the tumor cells can favor tumor progression.39-41 Therefore, it will be necessary to determine whether the chemokines inserted or induced in the tumor cells will have a detrimental rather than a positive effect.

In the present study, we show that primary leukemia B cells do not express relevant levels of chemokines. This paucity of chemokine production is striking and may contribute to the leukemia cells' ability to evade the host's immune system. Although other factors, such as the inadequate expression of costimulatory molecules,16,42 may also account for this “immune escape,” we have demonstrated that this is not due to the lack of leukemia-specific T cells in the repertoire of the leukemia host.17 18 The lack of chemokine production by the tumor cells may prevent the attraction of existing effector cells to the tumor site and contribute to tumor cell immune evasion. It will be interesting to explore in other human tumors whether this is a more general mechanism used by tumors to evade tumor-specific T cells of the patient's repertoire.

We have previously shown that CD40 ligation of murine normal B-cell precursors induces the expression of MDC and TARC.43,44Our observation that human B-lineage cells can be induced to secrete MDC and TARC is particularly striking because both these chemokines have been previously described as being specifically secreted by myeloid cells.23,45,46 To date, MDC and TARC are the only T-cell chemoattractants known to be secreted by B cells. Their secretion following CD40 ligation suggests that MDC and TARC might play an important role in the guidance of T-cell–dependent B-cell responses in secondary lymphoid tissues,47,48 ensuring the recruitment of T-cell help and dendritic cells.7,8 13

CD40 is also expressed by other hematopoietic cells,49 as well as nonhematopoietic cells (eg, various endothelial and epithelial cells).50-53 It may thereby be important to determine whether CD40 ligation of tumor cells from other malignancies would also result in the modulation of chemokines that could attract immune effector cells to tumor sites. This study emphasizes the fact that the ability to manipulate the endogenous production of molecules critical for optimal tumor-APC function deserves further investigation.

The possibility that a single signal may modify the tumor cells to become optimal cell vaccines offers significant advantages in comparison with the more frequently explored gene transfer-based strategies, which are more labor intensive and can be associated with potentially life-threatening side effects.54 55 In conclusion, our demonstration that a single, physiologic signal delivered to the tumor cells is capable of improving both their immunogenicity and T-cell chemoattractiveness further underscores the rationale for the use of CD40-stimulated leukemia cells in vaccination strategies for the treatment of ALL.

We thank Dr W. Nicholas Haining for the critical reading of the manuscript.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health grants P01-CA68484 and P01-CA66996 (to L.M.N.); by the ‘Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro’ (AIRC), Milano, Italy; and the ‘Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia’ (FCT), Portugal. The Basel Institute for Immunology was funded and is supported by F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland. J.P.V. is a recipient of a fellowship from FCT, Portugal.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Angelo A. Cardoso, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Rm D-540B, 44 Binney St, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail:cardoso@mbcrr.harvard.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal