The glycolipid-anchored glycoprotein CD59 inhibits assembly of the lytic membrane attack complex of complement by incorporation into the forming complex. Absence of CD59 and other glycolipid-anchored molecules on circulating cells in the human hemolytic disorder paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria is associated with intravascular hemolysis and thrombosis. To examine the role of CD59 in protecting host tissues in health and disease, CD59-deficient (CD59−/−) mice were produced by gene targeting in embryonic stem cells. Absence of CD59 was confirmed by staining cells and tissues with specific antibody. Despite the complete absence of CD59, mice were healthy and fertile. Erythrocytes in vitro displayed increased susceptibility to complement and were positive in an acidified serum lysis test. Despite this, CD59−/− mice were not anemic but had elevated reticulocyte counts, indicating accelerated erythrocyte turnover. Fresh plasma and urine from CD59−/− mice contained increased amounts of hemoglobin when compared with littermate controls, providing further evidence for spontaneous intravascular hemolysis. Intravascular hemolysis was increased following administration of cobra venom factor to trigger complement activation. CD59−/− mice will provide a tool for characterizing the importance of CD59 in protection of self tissues from membrane attack complex damage in health and during diseases in which complement is activated.

Introduction

Cell membranes express a battery of proteins that regulate activation of the complement (C) system and provide essential defense against damage to self.1 Regulators act either on the enzymes of the activation pathways or on the lytic membrane attack complex (MAC). In humans, 2 broadly expressed proteins collaborate to effect control in the activation pathways, decay-accelerating factor (DAF; CD55) and membrane cofactor protein (MCP; CD46). A third regulator of the activation pathways, CR1 (CD35), is expressed at relatively few sites and acts primarily as a receptor for immune complexes. A single protein, CD59, controls MAC assembly by physical association with the nascent complex to prevent lytic pore formation.2 In rodents, in which MCP expression is restricted to testis,3,4 an additional broadly expressed regulator, termed Crry, functions in the activation pathways.5

Deficiencies of membrane C regulators in humans have provided clues to their importance in controlling C activation in vivo. In paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH), defects in the pathway of glycosyl phosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor synthesis in a hematopoietic stem cell–derived clone cause complete absence of GPI-anchored proteins on cells arising from the clone.6 PNH erythrocytes and other clone-derived blood cells thus lack the GPI-anchored C regulators DAF and CD59. Because human erythrocytes do not express the transmembrane-anchored regulator MCP, PNH erythrocytes have no membrane C regulators and are thus highly vulnerable to C damage. Isolated deficiencies of DAF and CD59 have been described and provide additional clues. Isolated deficiency of DAF has been reported in about 20 individuals in 4 kindreds.7-10 Absence of DAF was not associated with intravascular hemolysis or any other evidence of failure of C regulation, leading to the conclusion that absence of CD59 is the key factor in PNH. This conclusion was supported by reports of a single individual, presenting with a PNH-like syndrome, found to have isolated deficiency of CD59.11 12

The roles of the various regulators in tissue homeostasis have also been assessed in rodents using blocking monoclonal antibody (mAb) or by gene deletion. Blocking of Crry in rats caused profound hypotension and increased vascular permeability, indicating that Crry is a key membrane regulator in this species.13Blocking of CD59 alone caused no effect, but in combination with blocking of Crry, it exacerbated the hypotensive and other effects. Mice possess 2 DAF genes encoding, respectively, a GPI-anchored form that is widely distributed and a transmembrane form that is expressed only in testis.14 Deletion of the gene encoding the GPI form yielded healthy mice.15 The presence of intravascular hemolysis was not examined in this report; however, analysis in vitro of DAF-deficient erythrocytes revealed increased susceptibility to heterologous C attack. In stark contrast to the apparent lack of effect of DAF deficiency, deletion of the gene encoding Crry resulted in death in utero because of C activation in the fetoplacental unit.16

Although these studies implicate CD59 as an important C regulator in rodents and humans, much of the evidence is circumstantial and, for humans, based on a single case. We therefore set out to investigate the relevance of CD59 to C regulation by gene targeting in the mouse. We have previously described the cloning and characterization of mouse CD59.17 CD59 in the mouse resembles human CD59 in that it is broadly distributed and functions to regulate MAC assembly on mouse cells. The gene has been localized to a region of mouse chromosome 2 that is orthologous with the location of human CD59 on chromosome 11 and the gene structure is shown to resemble closely that in humans.18 We undertook to delete the gene encoding CD59 by standard gene-targeting technologies in mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells using a targeting vector designed to eliminate exon 3 that encodes the majority of the mature protein sequence. The derivation of CD59-deficient mice and the characterization of the resultant phenotype are here described.

Materials and methods

Generation of CD59-deficient mice

The mouse CD59 gene was cloned and characterized in this laboratory and was shown to span 4 exons, with the major coding portion of the gene present in the third exon. Sequence at the exon/intron boundaries was used to amplify the 2 intronic regions on either side of exon 3 by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). These regions were then subcloned into a vector either side of the neomycin resistance gene (neo, from pMC1Neo-poly(A)+; Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), forming a gene-targeting construct containing 6 kilobase (kb) of homologous sequence, capable of replacing exon 3 withneo. A negative selection marker, the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene, was also included at the 3′ end of the construct to enable selection against random integration. Embryonic stem cells derived from 129/Sv mice were transfected with the linearized vector by electroporation, and clones resistant to G418 and gancyclovir were screened for homologous recombination by PCR and Southern blot analysis. Recombinant clones were microinjected into blastocysts of C57BL/6 mice; chimeric mice thus generated were bred with female C57BL/6 mice, and germline transmission was detected by the presence of agouti offspring. Heterozygotes (CD59+/−) were identified by PCR and bred to produce homozygous CD59-deficient (CD59−/−) mice and wild-type (CD59+/+) littermates. All mice were maintained in specific pathogen-free conditions and handled according to institutional guidelines. In all the studies described below, mice on the mixed 129/Sv-C57BL/6 background were used.

Collection of urine and blood

Urine was collected from mice during the late afternoon. Individual mice were placed in a clean cage lined with Nescofilm (Azwell, Osaka, Japan) and observed closely until urine was passed. The urine was taken immediately into tubes on ice.

Blood was collected from mice anesthetized with halothane by tail snipping. Blood (200 μL) was collected into EDTA (10 μL 0.5 M stock) in graduated tubes for cell analysis and into tubes without anticoagulant for collection of serum. When large volumes of blood were required, mice were exsanguinated by cardiac puncture under halothane anesthesia. Blood was either used immediately or stored in an equal volume of Alsever solution at 4°C. Donor mouse blood was obtained by cardiac puncture from male Balb/C mice, serum was separated immediately after clotting on ice and stored in aliquots at −70°C.

Flow cytometry

Blood was harvested by cardiac puncture, and its components were separated by centrifugation on Histopaque 1083 (Sigma, Poole, United Kingdom). Monoclonal antibodies to mouse CD59 and mouse DAF were developed in this laboratory and were biotinylated for use in flow-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis.19Phycoerythrin-conjugated streptavidin was purchased from Jackson Laboratories (West Grove, PA). All analyses were carried out on a FACScalibur, using CELLQuest software (Becton Dickinson, Oxford, United Kingdom).

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were killed by exsanguination under anesthesia, and tissues were quick-frozen in 2-methyl butane chilled on dry ice. Cryosections (10 μm) were cut on a Shandon cryotome (Runcorn, United Kingdom) and labeled with the biotinylated mAbs described above followed by peroxidase-conjugated extra-avidin (Sigma, Poole, United Kingdom). Cryosections were then stained as described in detail elsewhere.20

Measurement of intravascular hemolysis and hemoglobinuria

Mouse blood (200 μL) was collected into tubes containing 10 μL 0.5 M EDTA. The blood was promptly centrifuged, the plasma carefully removed and diluted 1:10 in 0.942 M Na2CO3. Measurement of hemolysis in the diluted samples utilized the method of Harboe.21 22 Absorbance in each of the diluted plasma samples was measured at 380 nm, 415 nm, and 450 nm in a Pharmacia tunable spectrophotometer (Amersham Pharmacia, Amersham, United Kingdom). The hemoglobin concentration (cHb in grams per liter) for each diluted sample was calculated from the following formula: cHb = 1.65 × A415 − 0.93 × A380 − 0.73 × A450. For measurement of hemoglobinuria, freshly collected urine was aliquoted undiluted into the wells of a 96-well plate (100 μL/well). The absorbance at 412 nm was measured in a BioRad (Hemel Hempstead, United Kingdom) plate reader as an index of hemoglobin content.

Measurement of hematology profile and erythrocyte half-life

Mouse blood (0.5 mL) was obtained by cardiac puncture and collected into EDTA-containing tubes. The blood was analyzed on an automated hematology analyser (Bayer Advia 120; Newbury, United Kingdom) that had previously been shown to generate reproducible data from mouse blood. All standard hematologic parameters, including reticulocyte count, were measured. Reticulocyte measurement on this analyser involves the measurement of light scatter and absorption by cells exposed to RNA stains, followed by automatic signal processing. The erythrocyte half-life (t1/2) in CD59−/−mice was calculated from the following formula: t1/2CD59−/− = t1/2CD59+/+ × ([% reticulocytes in CD59+/+/% mature erythrocytes in CD59+/+]/[% reticulocytes in CD59−/−/% mature erythrocytes in CD59−/−]). The half-life of CD59+/+erythrocytes was taken as 15 days, the published figure for normal erythrocytes in mice of this genetic background.23 24

Measurement of C hemolytic activity in CD59−/− and CD59+/+ mice

Mouse blood (0.2 mL) was collected into tubes without anticoagulant and clotted on ice for 1 hour; serum was separated by centrifugation. Serum was assayed immediately or stored at −70°C. Rabbit erythrocytes were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom), and a 2% suspension was incubated with an equal volume of a 1:250 dilution in PBS of mouse anti–rabbit erythrocyte antiserum (made in house) for 15 minutes at 37°C. The antibody-sensitized rabbit erythrocytes were washed into Veronal buffered saline (VBS++, C fixation diluent; Oxoid) at 1% final concentration. For each mouse serum to be tested, doubling dilutions in VBS++ were made in the wells of a 96-well plate (50 μL/well), including zero and 100% lysis wells. The antibody-sensitized rabbit erythrocytes (50 μL) were added to each well, and the plate was incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. Intact cells were removed by centrifugation, and the absorbance at 540 nm in the supernatant was measured as an index of hemolysis. Percentage of hemolysis for each well and CH50 for each serum were calculated by standard methods.25

In vitro C lysis assays on mouse erythrocytes

Classical pathway assay.

Washed erythrocytes were resuspended in PBS at 2% (vol/vol) and sensitized by incubation for 15 minutes on ice with a 1:100 final dilution in PBS of rabbit anti–mouse erythrocyte antiserum (generated in house). The original antiserum, made by immunization with washed normal mouse erythrocytes, contained substantial anti-CD59 reactivity as assessed by Western blotting. This reactivity was completely removed by passage of the antiserum over a column of recombinant mouse CD59 coupled to Sepharose prior to use in hemolysis assays. Sensitized erythrocytes (EAs) were washed, resuspended to 2% in VBS++, aliquoted into the wells of a 96-well plate (0.1 mL/well), and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes with 0.1 mL dilutions of rat or mouse serum in VBS++. Zero and 100% lysis controls were included in all assays. Plates were centrifuged, and the absorbance at 412 nm in the supernatant was measured as an index of lysis. Percentage of lysis for individual wells was calculated from the following formula: % lysis = (test OD412-zero OD412 / 100% OD412-zero OD412) × 100.

Cobra venom factor–mediated “reactive lysis” assay.

Washed erythrocytes were resuspended in VBS++ at 1% (vol/vol), aliquoted into the wells of a 96-well plate (0.1 mL/well), and incubated with dilutions of rat or mouse serum (0.1 mL in VBS++) and cobra venom factor (CVF; 1.5 μg/mL final) for 15 minutes at 37°C. Zero and 100% lysis controls were included in all assays. Plates were centrifuged, and the absorbance at 412 nm in the supernatant was measured as an index of lysis. Percentage of lysis was calculated as described above.

C5b-7 site assay.

Erythrocytes were antibody sensitized as described. EAs (2% in VBS++) were then incubated with an equal volume of C8-depleted human or rat serum (diluted 1:5 in VBS++) for 15 minutes at 37°C. The C5b-7–bearing intermediates so formed (EAC5b-7) were washed and resuspended at 1% in PBS. EAC5b-7s were aliquoted into the wells of a 96-well plate (100 μL/well) and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C with various dilutions of mouse or rat serum (100 μL in PBS). Zero and 100% lysis controls were included in all assays. Plates were centrifuged, and the absorbance at 412 nm in the supernatant was measured as an index of lysis. Percentage of lysis was calculated as described above.

Acidified serum lysis assay (Ham test).

The Ham test is the classical test for PNH.26 A modified Ham test, based on that described by Okada et al,11 was used in this study. Aliquots (100 μL) of fresh rat serum were placed in wells of a 96-well plate and acidified by addition of 0.2 N HCl, 10 μL/well. The pH of the serum immediately following acidification was between 6.5 and 6.8. Erythrocytes (10 μL 50% E in PBS) were added to each well, and the plate was incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. Zero and 100% lysis controls were included in all assays. Plates were centrifuged, and the absorbance at 412 nm in the supernatant was measured as an index of lysis. Percentage of lysis was calculated as described above.

Administration of CVF

CD59−/− (3 male, 3 female) and CD59+/+(3 male, 3 female) mice were bled by tail snipping into EDTA-containing tubes that were kept on ice. Mice were then given CVF (5 mg/kg in PBS) intraperitoneally. All mice were closely observed for signs of distress. All were exsanguinated 1 hour after administration of CVF and blood taken into EDTA as before. Plasma was separated and cHb was measured in pre-CVF and post-CVF samples as described above.

Results

Generation of CD59-deficient mice

The mouse CD59 gene was disrupted by homologous recombination in ES cells. The targeting vector was designed to replace the major coding portion of the gene, exon 3, with the neomycin resistance gene (Figure1). Three of 200 clones screened were successfully targeted and these were expanded and microinjected into C57BL/6 blastocysts. Chimeric mice showed germline transmission of the disrupted gene, and resultant heterozygotes were bred to give homozygotes, heterozygotes, and wild-type offspring in Mendelian ratios. Homozygous mutants were fully viable and fertile. No obvious abnormalities were seen up to 30 weeks, except that male CD59−/− mice were consistently 2 to 3 g lighter in weight than their CD59+/+ male littermates. Female mice showed no difference in weight according to genotype.

Targeted disruption of Cd59.

(A) A gene-targeting vector was constructed in which exon 3, the major coding portion of the protein, was replaced by the neomycin-resistance gene (neo). The herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase cassette (HSV-tk) was inserted at the 3′ end of the homologous region (delineated by dotted lines). Double-headed arrows indicate the size of fragments seen in Southern blot analysis of wild-type (top) and targeted (bottom) alleles afterBglII digestion of genomic DNA hybridized to the external probe (hatched box). (B) Southern blot analysis of ES cell DNA showing wild-type and targeted clones. (C) PCR genotyping of genomic DNA derived from the progeny of CD59+/− mice showing the 200-bp fragment amplified from the wild-type allele (with primers P1 and P3) and the 450-bp fragment amplified from the targeted allele (with primers P2 and P3).

Targeted disruption of Cd59.

(A) A gene-targeting vector was constructed in which exon 3, the major coding portion of the protein, was replaced by the neomycin-resistance gene (neo). The herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase cassette (HSV-tk) was inserted at the 3′ end of the homologous region (delineated by dotted lines). Double-headed arrows indicate the size of fragments seen in Southern blot analysis of wild-type (top) and targeted (bottom) alleles afterBglII digestion of genomic DNA hybridized to the external probe (hatched box). (B) Southern blot analysis of ES cell DNA showing wild-type and targeted clones. (C) PCR genotyping of genomic DNA derived from the progeny of CD59+/− mice showing the 200-bp fragment amplified from the wild-type allele (with primers P1 and P3) and the 450-bp fragment amplified from the targeted allele (with primers P2 and P3).

CD59 protein is not expressed on cells or tissues from CD59−/− mice

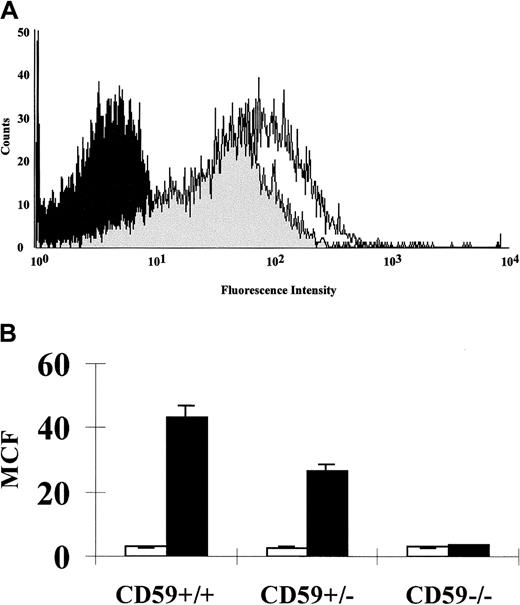

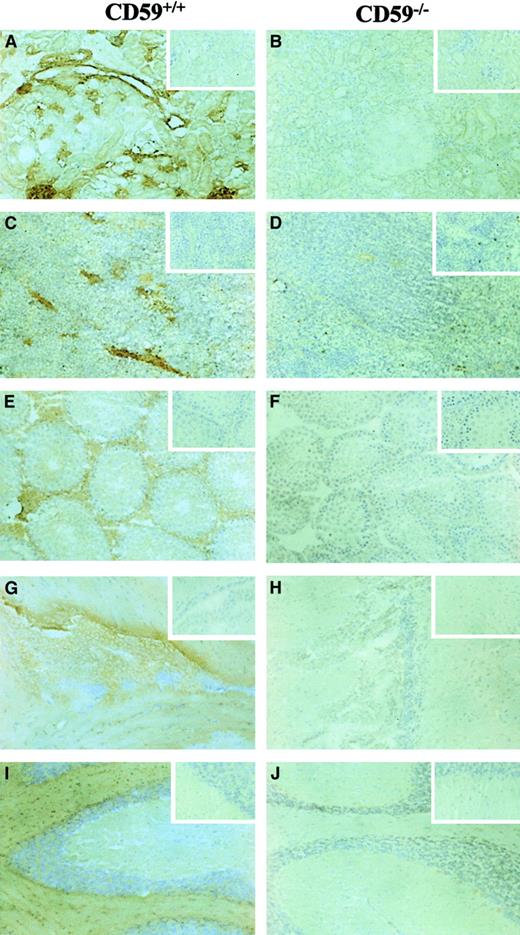

FACS analysis on erythrocytes from CD59−/−, CD59+/−, and CD59+/+ mice (3 in each group, age 8 weeks at sampling) showed a 50% loss of CD59 expression in heterozygotes and total loss of the protein in CD59−/−mice (Figure 2). The expression of CD59 on leukocytes and platelets showed a similar pattern with no staining on cells from CD59−/− mice. No up-regulation of the C regulators DAF or Crry was observed on cells from CD59−/−mice (data not shown). Immunohistochemistry on a range of tissues from 4-week-old male mice, including kidney, spleen, testis, and brain, showed total loss of CD59 expression in homozygous knockout mice compared with CD59+/+ littermate controls (Figure3). No obvious morphologic differences were apparent in tissues from CD59−/− mice compared with CD59+/+ mice.

CD59 expression on erythrocytes of CD59+/+, CD59+/−, and CD59−/− mice.

Erythrocytes were isolated by centrifugation, labeled with a biotinylated anti-CD59 mAb followed by phycoerythrin-conjugated streptavidin, and gated on the forward scatter versus side scatter dot plot generated by the FACSCalibur. (A) Overlay of the histogram profiles of CD59+/+ (unshaded), CD59+/−(lightly shaded), and CD59−/− (heavily shaded) erythrocytes. (B) Graph showing the CD59 mean cell fluorescence (MCF) obtained for erythrocytes from CD59+/+, CD59+/−, and CD59−/− mice (filled bars; 3 in each group). The negative controls shown underwent the same procedure but without the anti-CD59 mAb being present (open bars). Error bars represent SD for the 3 determinations.

CD59 expression on erythrocytes of CD59+/+, CD59+/−, and CD59−/− mice.

Erythrocytes were isolated by centrifugation, labeled with a biotinylated anti-CD59 mAb followed by phycoerythrin-conjugated streptavidin, and gated on the forward scatter versus side scatter dot plot generated by the FACSCalibur. (A) Overlay of the histogram profiles of CD59+/+ (unshaded), CD59+/−(lightly shaded), and CD59−/− (heavily shaded) erythrocytes. (B) Graph showing the CD59 mean cell fluorescence (MCF) obtained for erythrocytes from CD59+/+, CD59+/−, and CD59−/− mice (filled bars; 3 in each group). The negative controls shown underwent the same procedure but without the anti-CD59 mAb being present (open bars). Error bars represent SD for the 3 determinations.

Immunohistochemistry of tissue sections from CD59+/+ and CD59−/− mice.

All sections were labeled with a biotinylated anti-CD59 mAb followed by peroxidase-conjugated extra-avidin (Sigma), using DAB substrate and then counterstained with hematoxylin. The inserts show control sections that underwent the same procedure but without the mAb being present. The tissues represented are (A,B) kidney, (C,D) spleen, (E,F) testis, (G,H) brain (sagittal section through lateral ventricle), and (I,J) cerebellum. Magnification ×20 for all plates.

Immunohistochemistry of tissue sections from CD59+/+ and CD59−/− mice.

All sections were labeled with a biotinylated anti-CD59 mAb followed by peroxidase-conjugated extra-avidin (Sigma), using DAB substrate and then counterstained with hematoxylin. The inserts show control sections that underwent the same procedure but without the mAb being present. The tissues represented are (A,B) kidney, (C,D) spleen, (E,F) testis, (G,H) brain (sagittal section through lateral ventricle), and (I,J) cerebellum. Magnification ×20 for all plates.

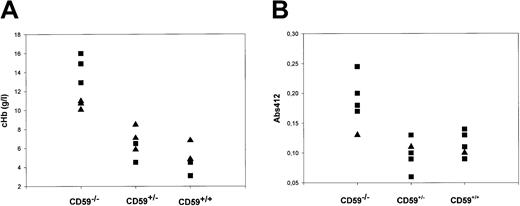

Mice lacking CD59 exhibit spontaneous intravascular hemolysis and hemoglobinuria

Fresh EDTA plasma samples were obtained by cardiac puncture under conditions that minimized the possibility of hemolysis ex vivo from CD59+/+, CD59+/−, and CD59−/−mice (6 in each group, 3 each female and male, age 10 weeks at sampling), and cHb was measured by spectrophotometry at multiple wavelengths. The mean cHb was 12.6 g/L in CD59−/− mice, 6.5 g/L in CD59+/− mice, and 4.8 g/L in CD59+/+ mice (Figure 4a). The difference was statistically significant when comparing CD59−/− mice with either of the other groups (P < .05 by one-way analysis of variance). Of note, cHb was significantly higher in male CD59−/− mice than in females (14.6 g/L versus 10.6 g/L; P < .05).

Intravascular hemolysis and hemoglobinuria in CD59−/− mice.

(A) CD59+/+, CD59+/−, and CD59−/− mice (6 CD59−/−, 5 in other groups) were bled into EDTA tubes and the plasma was promptly separated. The hemoglobin concentration (cHb) in each plasma sample was measured by spectrophotometry of the diluted plasma sample at 3 wavelengths and application of a published formula. Male mice are represented by squares, females by triangles. Of note, the 3 mice in the CD59−/− group with the highest cHb were all male. Similar results were obtained with a second set of mice. (B) Urine was collected from CD59+/+, CD59+/−, and CD59−/− mice (6 CD59−/−, 5 in other groups), and absorbance at 412 nm in the undiluted urine was measured. Male mice are represented by squares, females by triangles.

Intravascular hemolysis and hemoglobinuria in CD59−/− mice.

(A) CD59+/+, CD59+/−, and CD59−/− mice (6 CD59−/−, 5 in other groups) were bled into EDTA tubes and the plasma was promptly separated. The hemoglobin concentration (cHb) in each plasma sample was measured by spectrophotometry of the diluted plasma sample at 3 wavelengths and application of a published formula. Male mice are represented by squares, females by triangles. Of note, the 3 mice in the CD59−/− group with the highest cHb were all male. Similar results were obtained with a second set of mice. (B) Urine was collected from CD59+/+, CD59+/−, and CD59−/− mice (6 CD59−/−, 5 in other groups), and absorbance at 412 nm in the undiluted urine was measured. Male mice are represented by squares, females by triangles.

Fresh urine samples were collected from CD59+/+, CD59+/−, and CD59−/− mice (5 in each group, age 8 weeks at sampling) and assessed for hemoglobin content by measuring absorbance at 412 nm. Absorbance in urine from the CD59−/− mice was significantly increased in comparison with each of the other groups (P < .001 by one-way analysis of variance), indicating the presence of hemoglobin in the urine (Figure 4b).

Mice lacking CD59 are not anemic but do have an elevated reticulocyte count

In a first study, blood samples from CD59−/−, CD59+/−, and CD59+/+ littermate mice (6 in each group, 3 each female and male, age 10 weeks at sampling) were run on an automated hematology analyser. Two samples were lost because of clotting in the tube. All standard parameters were measured (Table1). Hemoglobin concentration, red cell number, and platelet number did not differ between the groups. However, reticulocyte count was significantly elevated in the CD59−/− mice as compared with either of the other groups (CD59−/−, 5.14%; CD59+/−, 3.16%; CD59+/+, 3.06%; P < .01). Reticulocyte counts in CD59−/− mice were lower in females than in male mice, although this difference was not statistically significant. In a second study, blood samples were taken from CD59−/− and CD59+/+ mice (10 in each group, all males, age 20 weeks at sampling) and analyzed as described above. Again, with the exception of the reticulocyte count, hematologic parameters did not differ between the groups (Table 1). In these older mice the reticulocyte count was significantly elevated in the CD59−/− mice (CD59−/−, 4.58%; CD59+/+, 3.43%;P < .001). Taking the t1/2 in wild-type mice on this background as 15 days,24 the calculated t1/2 in CD59−/− mice was 8.7 days from study 1 and 11.1 days from study 2.

Key hematology parameters in CD59−/−, CD59+/−, and CD59+/+ mice

| . | Hb (g/dL) . | RBC (1012/L) . | WBC (109/L) . | Plts (109/L) . | Retics (109/L) . | Retics (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 (n = 5 in each group) | ||||||

| CD59−/− | 14.20 (0.97) | 9.28 (0.56) | 1.89 (1.21) | 997 (102) | 472 (85.7)* | 5.14 (1.25)* |

| CD59+/− | 14.00 (0.53) | 9.28 (0.27) | 2.39 (0.89) | 985 (223) | 294 (64.3) | 3.16 (0.63) |

| CD59+/+ | 14.48 (0.33) | 9.48 (0.42) | 3.58 (1.52) | 1029 (216) | 290 (22.4) | 3.06 (0.23) |

| Study 2 (n = 10 in each group) | ||||||

| CD59−/− | 14.90 (0.77) | 9.78 (0.49) | 4.76 (2.65) | 1071 (150) | 448 (53.4)* | 4.58 (0.48)* |

| CD59+/+ | 14.60 (0.51) | 9.85 (0.35) | 4.83 (2.19) | 1210 (236) | 338 (39.7) | 3.43 (0.33) |

| . | Hb (g/dL) . | RBC (1012/L) . | WBC (109/L) . | Plts (109/L) . | Retics (109/L) . | Retics (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 (n = 5 in each group) | ||||||

| CD59−/− | 14.20 (0.97) | 9.28 (0.56) | 1.89 (1.21) | 997 (102) | 472 (85.7)* | 5.14 (1.25)* |

| CD59+/− | 14.00 (0.53) | 9.28 (0.27) | 2.39 (0.89) | 985 (223) | 294 (64.3) | 3.16 (0.63) |

| CD59+/+ | 14.48 (0.33) | 9.48 (0.42) | 3.58 (1.52) | 1029 (216) | 290 (22.4) | 3.06 (0.23) |

| Study 2 (n = 10 in each group) | ||||||

| CD59−/− | 14.90 (0.77) | 9.78 (0.49) | 4.76 (2.65) | 1071 (150) | 448 (53.4)* | 4.58 (0.48)* |

| CD59+/+ | 14.60 (0.51) | 9.85 (0.35) | 4.83 (2.19) | 1210 (236) | 338 (39.7) | 3.43 (0.33) |

Hb, hemoglobin; RBC, red blood cell count; WBC, white blood cell count; Plts, platelets; Retics, reticulocytes. Numbers in brackets are SDs. The mice in study 1 were 10-week-old littermates (mixed sexes), and in study 2 they were 20-week-old littermates (all male).

Significant differences (P < .01 toP < .001) when compared with same parameter in other group(s) in study.

Female CD59−/− mice have markedly reduced hemolytic C levels compared with male mice

Serum C hemolytic activity was assessed in CD59−/−(3 male, 2 female), CD59+/− (2 male, 3 female), and CD59+/+ (2 male, 3 female) littermate mice at 10 weeks. There was no difference in hemolytic activities for same-sex mice in the 3 groups, but male mice in each group had CH50 levels 10- to 12-fold higher than female mice. For the male mice the mean CH50 value (7 mice) was 85 hemolytic units (hu); for female mice (8 mice) the mean CH50 value was 7 hu.

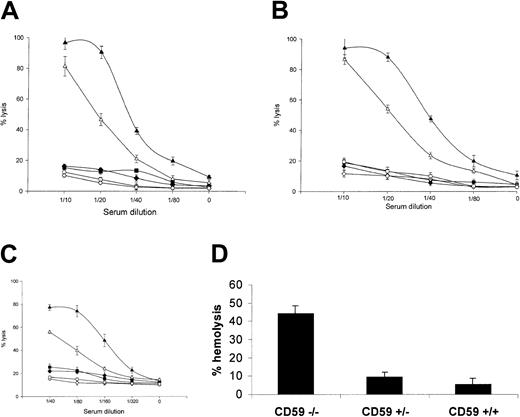

Erythrocytes from mice lacking CD59 are highly sensitive to heterologous and homologous C lysis in vitro

In a classical pathway assay, using an antiserum raised against mouse erythrocytes adsorbed to remove anti-CD59 reactivity, antibody-sensitized erythrocytes from CD59−/− mice were much more sensitive to C lysis using heterologous (rat) or homologous (mouse) serum as a source of C than those from CD59+/+ mice (Figure 5a). At serum dilutions causing approximately 80% to 100% hemolysis of CD59−/−erythrocytes, erythrocytes from CD59+/− and CD59+/+ mice were not lysed above background by either serum source. Of note, when the nonadsorbed antiserum was used to sensitize, CD59+/+ erythrocytes were lysed to a much greater extent, indicating that the anti-CD59 activity in the antiserum blocked CD59 function (data not included). In a CVF-mediated reactive lysis assay using heterologous (rat) or homologous (mouse) serum as source of C, erythrocytes from CD59−/− mice were again much more sensitive to C attack than those from CD59+/+mice (Figure 5b). In a C5b-7 site assay using mouse erythrocytes bearing human C5b-7 and either rat or mouse serum as a source of C8 and C9, erythrocytes from CD59−/− mice were also much more sensitive to C attack than those of CD59+/+ mice (Figure5c). Similar results were obtained using mouse erythrocytes bearing rat C5b-7 sites (data not shown). In a modified Ham test using rat serum as a source of C, erythrocytes from CD59−/− mice were positive in that they were lysed by acidified serum, whereas erythrocytes from the other groups were not lysed under the same conditions (Figure 5d). Mouse serum was not lytic in this assay.

Erythrocytes from CD59−/− mice are susceptible to C lysis.

Four lytic assays were used to test lytic susceptibility of CD59−/− erythrocytes. In each case, erythrocytes from 3 mice of each group were tested and results are means (± SDs) of the percentage of lysis for the 3. (A) Classical pathway assay. Erythrocytes were sensitized and exposed to dilutions of rat (closed symbols) or mouse (open symbols) serum. CD59+/+ (diamond) and CD59+/− (square) erythrocytes were lysed significantly only at the highest serum doses used (1:10), whereas CD59−/− (triangles) erythrocytes were almost completely lysed at this dose when exposed to rat serum, 80% lysed at the same dose of mouse serum and were measurably lysed at all serum doses tested. (B) CVF-triggered reactive lysis assay. Unsensitized erythrocytes were incubated with CVF and dilutions of rat (closed symbols) or mouse (open symbols) serum. CD59+/+ (diamond) and CD59+/− (square) erythrocytes were not lysed even at the highest serum doses used (1:10), whereas CD59−/−(triangles) erythrocytes were almost completely lysed at this dose of either rat or mouse serum and were measurably lysed at all doses tested. (C) C5b-7 site assay. Erythrocytes bearing preformed C5b-7 sites were incubated with dilutions of rat (closed symbols) or mouse (open symbols) serum in PBS as source of C8/C9. Even at the highest dose (1:40), neither rat nor mouse serum lysed CD59+/+(diamond) and CD59+/− (square) erythrocytes, whereas CD59/ (triangle) erythrocytes were 80% lysed when exposed to rat serum and 50% lysed by mouse serum at this dose and were measurably lysed at all serum doses. (D) A modified Ham test in which unsensitized erythrocytes were incubated at 37°C with acidified serum. CD59−/− erythrocytes were lysed more than 40%, whereas CD59+/+ and CD59+/− erythrocytes were not significantly lysed.

Erythrocytes from CD59−/− mice are susceptible to C lysis.

Four lytic assays were used to test lytic susceptibility of CD59−/− erythrocytes. In each case, erythrocytes from 3 mice of each group were tested and results are means (± SDs) of the percentage of lysis for the 3. (A) Classical pathway assay. Erythrocytes were sensitized and exposed to dilutions of rat (closed symbols) or mouse (open symbols) serum. CD59+/+ (diamond) and CD59+/− (square) erythrocytes were lysed significantly only at the highest serum doses used (1:10), whereas CD59−/− (triangles) erythrocytes were almost completely lysed at this dose when exposed to rat serum, 80% lysed at the same dose of mouse serum and were measurably lysed at all serum doses tested. (B) CVF-triggered reactive lysis assay. Unsensitized erythrocytes were incubated with CVF and dilutions of rat (closed symbols) or mouse (open symbols) serum. CD59+/+ (diamond) and CD59+/− (square) erythrocytes were not lysed even at the highest serum doses used (1:10), whereas CD59−/−(triangles) erythrocytes were almost completely lysed at this dose of either rat or mouse serum and were measurably lysed at all doses tested. (C) C5b-7 site assay. Erythrocytes bearing preformed C5b-7 sites were incubated with dilutions of rat (closed symbols) or mouse (open symbols) serum in PBS as source of C8/C9. Even at the highest dose (1:40), neither rat nor mouse serum lysed CD59+/+(diamond) and CD59+/− (square) erythrocytes, whereas CD59/ (triangle) erythrocytes were 80% lysed when exposed to rat serum and 50% lysed by mouse serum at this dose and were measurably lysed at all serum doses. (D) A modified Ham test in which unsensitized erythrocytes were incubated at 37°C with acidified serum. CD59−/− erythrocytes were lysed more than 40%, whereas CD59+/+ and CD59+/− erythrocytes were not significantly lysed.

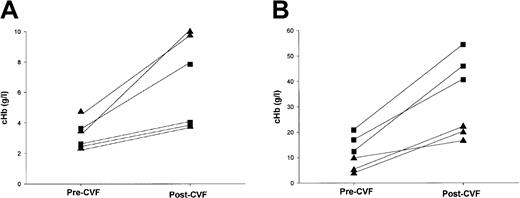

Administration of CVF provokes further intravascular hemolysis in CD59−/− mice

Administration of CVF to male mice (3 littermates of each genotype, aged 9 weeks at testing), caused a marked increase in cHb in CD59−/− mice at 1 hour after administration (Figure6). The cHb also increased in female CD59−/− mice, albeit to a lesser extent. In CD59+/+ mice, cHb was only slightly increased following CVF treatment. None of the CVF-treated mice developed severe clinical symptoms, although some mice in all groups showed mild signs of shivering and piloerection.

CVF induces further intravascular hemolysis in CD59−/− mice.

Mice were bled prior to intraperitoneal injection of CVF. After 1 hour the mice were exsanguinated. Plasma was separated from the pre-CVF and post-CVF bleeds, and cHb was measured by spectrophotometry as described in the “Materials and methods” section. Male mice are depicted by squares, females by triangles. (A) In CD59+/+ mice, cHb was low in the pre-CVF sample and, although cHb increased in all mice (lines join pre- and postsamples for individual mice), remained low post-CVF. (B) In CD59−/− mice, cHb was high in the pre-CVF samples and, in some mice, increased to very high levels after CVF treatment. Of note, the 3 mice with the highest pre- and post-CVF cHb levels were male; the other 3, showing modest increases, were female. Note different scales in (A) and (B).

CVF induces further intravascular hemolysis in CD59−/− mice.

Mice were bled prior to intraperitoneal injection of CVF. After 1 hour the mice were exsanguinated. Plasma was separated from the pre-CVF and post-CVF bleeds, and cHb was measured by spectrophotometry as described in the “Materials and methods” section. Male mice are depicted by squares, females by triangles. (A) In CD59+/+ mice, cHb was low in the pre-CVF sample and, although cHb increased in all mice (lines join pre- and postsamples for individual mice), remained low post-CVF. (B) In CD59−/− mice, cHb was high in the pre-CVF samples and, in some mice, increased to very high levels after CVF treatment. Of note, the 3 mice with the highest pre- and post-CVF cHb levels were male; the other 3, showing modest increases, were female. Note different scales in (A) and (B).

Discussion

Although it is clear that membrane C regulators provide an essential defense against damage to self cells when C is activated either through the physiologic process of “tickover” or in response to foreign particles in pathology, the relative importance of the different regulators is unclear. Attempts have been made to elucidate the relative contributions of the various regulators to homeostasis in vivo by neutralizing single or multiple regulators in rodents using specific antibodies.13,27,28 These studies have demonstrated a key role for Crry in the regulation of C activation and the importance of CD59 as a second-line defense when activation is inadequately regulated in the activation pathways. Although neutralization of CD59 alone in vivo in rats caused only minor disturbance, in combination with neutralization of Crry, an important role for CD59 was revealed. Indeed, neutralization of CD59 alone in a normal rat knee was sufficient to trigger an acute arthritis, presumably because of the high level of tickover activation occurring at this site.29 Further, neutralization of CD59 in the rat kidney caused a marked exacerbation of disease in a model of glomerulonephritis.30

Indications of the relative importance of membrane regulators in man have been gleaned from studies of the acquired hemolytic disorder PNH and rare inherited deficiencies. In PNH, a mutation in a hematopoietic stem cell gives rise to an expanding clone of blood cells that lack glycolipid-anchored molecules.6,31 Erythrocytes and other blood cells derived from the clone thus lack DAF and CD59. Human erythrocytes also do not express MCP, making PNH erythrocytes particularly susceptible to C damage because they lack all intrinsic C regulators. Individuals present with hemoglobinuria, anemia, and, sometimes, thrombotic problems because of involvement of platelets and neutrophils. Isolated deficiency of DAF has been described in 4 families and is not associated with loss of C regulation, implying that lack of DAF is not itself responsible for the hemolytic and thrombotic features of PNH.7-9 In contrast, isolated CD59 deficiency has been reported in a single individual, a 22-year-old Japanese man who had presented with a classical PNH-like syndrome at the unusually young age of 13 and continued to experience episodes of hemolysis and intravascular thrombosis.12 32 This single case implicated lack of CD59 as the key factor in causing pathology in PNH. However, given that only a single case of CD59 deficiency has been described and relatively few studies of the susceptibility of CD59−cells to C damage have been published, evidence indicating a key role for CD59 in homeostasis remains circumstantial.

In the present study, we undertook to delete the gene encoding CD59 in mice by homologous recombination in ES cells. Mouse CD59 had previously been identified, characterized, and cloned in this laboratory,17 and the genomic structure ascertained,18 enabling design of a gene-targeting cassette. Heterozygote crosses produced homozygote CD59−/− mice at the predicted frequency, indicating that absence of CD59 did not compromise the embryo. This finding contrasts with that in the Crry gene-deleted mice, in which C activation in the fetoplacental unit caused 100% loss of embryos.16 Initial characterization of homozygote CD59−/− mice confirmed that CD59 was absent from all circulating cells and all tissues. The mice appeared to be healthy, bred readily, and produced litters of the anticipated size. Male CD59−/− mice were consistently approximately 10% (2 to 3 g in adults) lighter than their CD59+/+ male littermates. We have no explanation for this observation at present and are continuing to monitor the mice.

We have used the CD59−/− mice so obtained to explore further the roles of CD59 in vivo, focusing initially on the role of CD59 in protecting erythrocytes from C lysis. Despite the presence of DAF and Crry, erythrocytes from the CD59−/− mice were much more susceptible in a classical pathway assay to lysis by homologous or heterologous serum in vitro than those taken from heterozygote or wild-type littermate controls. This increased lytic susceptibility was also seen in assays targeting specifically the membrane attack pathway. CD59−/− erythrocytes bearing human or rat C5b-7 sites were extremely susceptible to lysis when either rat or mouse serum was added as a source of terminal C components, whereas wild-type controls treated in an identical manner were resistant. These results confirmed that the lytic deficit in the CD59−/− erythrocytes was in regulation of MAC assembly and that mouse CD59 regulates both heterologous and homologous C. The classical test for PNH, the Ham test,26 involves exposure of erythrocytes to fresh, acidified serum. Mild acidification of serum to a pH between 6.5 and 7.0 causes activation of the alternative pathway through enhancement of convertase formation33 and directly activates MAC assembly by triggering generation of C5b-6–like complexes in the fluid phase.34 35 CD59−/−erythrocytes were positive in the Ham test, that is, they lysed, whereas wild-type erythrocytes were negative. Mouse erythrocytes express Crry and DAF to protect against C activation. No compensatory increase in expression of either regulator was detected on erythrocytes or other circulating cells in the CD59−/− mice (data not shown).

In marked contrast to the findings in humans with PNH and the CD59-deficient individual, CD59−/− mice were not anemic and the standard hematologic parameters were unremarkable. However, the mean reticulocyte count in CD59−/− mice was significantly increased when compared with wild-type mice, indicative of increased erythrocyte turnover. Mice were studied at 10 and 20 weeks of age. The calculated t1/2 in CD59−/− mice at these ages were 8.7 days and 11.1 days, respectively, a highly significant decrease when compared to 15 days in wild-type mice. Plasma from CD59−/− mice contained increased levels of hemoglobin as compared with littermate controls and evidence for hemoglobinuria was also obtained. Together, these findings provide strong evidence that spontaneous intravascular hemolysis occurred in the absence of CD59.

Male CD59−/− mice, when compared with females at 10 weeks of age, had higher reticulocyte counts (mean of 5.63% versus 4.23%) and shorter calculated t1/2 (7.9 days versus 10.7 days). Both intravascular hemolysis and hemoglobinuria were also greater in male CD59−/− mice than in females, although erythrocytes tested in vitro were equally susceptible to C lysis. These findings led us to ask whether the sex difference observed in vivo was due to differences in serum C activity. Analysis of plasma hemolytic activities confirmed that male mice had much higher hemolytic C activities, providing a likely explanation for the observed sex difference. Administration of CVF to initiate intravascular activation of C caused a marked increase in plasma cHb in male CD59−/− mice, indicating increased intravascular hemolysis. The CVF-induced increase in cHb was much less in female CD59−/− mice and was very small in CD59+/+mice of either sex.

It must be stressed that the phenotype observed in the CD59−/− mice is mild and differs in many respects from that seen in PNH. The mice were not anemic, and reticulocyte counts and plasma hemoglobin levels were only modestly increased when compared with the levels seen in PNH. Two reports have described attempts to generate by different strategies a mouse model of PNH by creating mosaic mice in which a proportion of the hemopoietic stem cells bear mutations in the piga gene and are consequently deficient in GPI-anchored proteins.23,36 The percentage of circulating erythrocytes lacking GPI-linked proteins, including CD59 and DAF, was 4% in one study and 20% to 30% in the other. In the former study, a rigorous hematologic analysis failed to detect evidence of intravascular hemolysis or hemoglobinuria, although the circulating half-life of the GPI-deficient erythrocytes was halved in comparison with normal erythrocytes in the same mice. Reduced t1/2 in this model may be due to increased opsonization and clearance because of absence of DAF or to increased intravascular hemolysis because of absence of CD59. In the present study, in which 100% of the circulating erythrocytes lack CD59 but express DAF and Crry, intravascular hemolysis and hemoglobinuria were present, albeit at low levels. The calculated t1/2 of GPI-deficient and CD59−/− erythrocytes were similar, 7.3 days and 8.7 days (at 10 weeks), respectively, suggesting that the role of DAF is minor and differences in observed phenotypes likely reflect the fact that only 4% of erythrocytes in the PNH model were compromised. Observations on mice deleted for the gene encoding the GPI-anchored form of DAF,15 and studies of DAF-deficient humans,7 support this suggestion.

The phenotypes in both the CD59−/− and thepiga chimaera mice are mild when compared with PNH. In PNH, erythrocytes lack all intrinsic membrane C regulators and are thus exquisitely sensitive to C; individuals presenting with moderate to severe anemia as compensatory mechanisms fail in the face of greatly increased erythrocyte turnover.37 In the models, erythrocytes express Crry and, in the CD59−/− mice, DAF. Anemia is not a feature of either of the models, although decreased t1/2 and sensitivity to C in vitro are observed in both. Protection afforded by the residual regulators, although insufficient to fully protect, enables compensatory mechanisms to prevail. A further confounding feature is that human erythrocytes, by virtue of their role in transporting immune complexes, may be more challenged by complement in vivo than mouse erythrocytes that do not perform this task.38 To create a mouse PNH model, Crry, DAF, and CD59 would all need to be deleted from blood cells. It should now be possible to generate DAF/CD59−/− mice by crossing the DAF−/− mice15 with those reported here, but elimination of Crry will be problematic because the knockout is lethal.16 Selective knockouts in which Crry is eliminated only on hemopoietic cells might be possible. Alternatively, antibody neutralization of Crry in DAF/CD59−/− mice may provide a working model.

A recent report describes the presence in mice of a second gene, designated cd59b, encoding a CD59-like protein expressed only in testis.39 We do not at present know whether this gene is expressed in the CD59−/− mice. No staining for CD59 was detected in testis of CD59−/− mice by using a specific mAb. However, the predicted protein encoded by thecd59b gene is only 63% identical to mouse CD59. It thus remains possible that the cd59b gene product is present and active in testis in the CD59−/− mice.

CD59 is the only membrane regulator of the membrane attack pathway to be characterized. Lack of CD59 will thus render all cells exposed to plasma susceptible to damage by MAC. The spontaneous intravascular hemolysis observed in the CD59−/− mice is only the most visible indication of a general inability to regulate MAC assembly. It is likely that other sequelae of the deficiency will emerge during aging, on removal of the mice from specific pathogen-free conditions into the more challenging environment of the animal house, and following challenge in models of C-mediated diseases.

Supported by the Wellcome Trust through the award of a Senior Clinical Fellowship (grant no. 016668 to B.P.M.) and Programme support (grant no. 054838 to M.J.W. and M.B.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

B. Paul Morgan, Complement Biology Group, Department of Medical Biochemistry, University of Wales College of Medicine, Cardiff, United Kingdom; e-mail: morganbp@cardiff.ac.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal