Abstract

Divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) is the major transferrin-independent iron uptake system at the apical pole of intestinal cells, but it may also transport iron across the membrane of acidified endosomes in peripheral tissues. Iron transport and expression of the 2 isoforms of DMT1 was studied in erythroid cells that consume large quantities of iron for biosynthesis of hemoglobin. In mk/mk mice that express a loss-of-function mutant variant of DMT1, reticulocytes have a decreased cellular iron uptake and iron incorporation into heme. Interestingly, iron release from transferrin inside the endosome is normal in mk/mkreticulocytes, suggesting a subsequent defect in Fe++ transport across the endosomal membrane. Studies by immunoblotting using membrane fractions from peripheral blood or spleen from normal mice where reticulocytosis was induced by erythropoietin (EPO) or phenylhydrazine (PHZ) treatment suggest that DMT1 is coexpressed with transferrin receptor (TfR) in erythroid cells. Coexpression of DMT1 and TfR in reticulocytes was also detected by double immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy. Experiments with isoform-specific anti-DMT1 antiserum strongly suggest that it is the non–iron-response element containing isoform II of DMT1 that is predominantly expressed by the erythroid cells. As opposed to wild-type reticulocytes, mk/mk reticulocytes express little if any DMT1, despite robust expression of TfR, suggesting a possible effect of the mutation on stability and targeting of DMT1 isoform II in these cells. Together, these results provide further evidence that DMT1 plays a central role in iron acquisition via the transferrin cycle in erythroid cells.

Introduction

The divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1), also known as natural resistance–associated macrophage protein 2 (Nramp2) or divalent cation transporter 1 (DCT1), is a protein recently shown to play a pivotal role in iron uptake from both transferrin (Tf) and non-Tf sources in different anatomic sites.1,2 DMT1 is an integral membrane protein formed by 12 predicted transmembrane (TM) domains, several of which contain charged residues. This structural unit defines a protein family highly conserved from bacteria to man3,4 and that includes the closely related phagocyte-specific homologue Nramp1 (78% similarity) involved in macrophage function and resistance to infections.5The DMT1 gene encodes 2 messenger RNAs (mRNAs; isoforms I and II) produced by alternative splicing of two 3′ exons, resulting in transcripts with different 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) and encoding proteins with distinct C-termini.6,7 One of the DMT1 mRNAs, isoform I, is predicted to contain an iron-responsive element (IRE). DMT1 isoform II encodes a protein in which the C-terminal 18 amino acids derived from IRE-containing mRNA are replaced by a novel 25–amino acid segment.6 7

Studies in Xenopus laevis oocytes have shown that DMT1 (isoform I) is an electrogenic transporter of divalent cations including Fe++, Zn++, Mn++, and others.8 Studies in vitro in cultured mammalian cells have also demonstrated that both DMT1 isoforms can transport a variety of divalent cations at the plasma membrane, including Fe++.9-11 In mammalian cells, DMT1-mediated Fe++ transport was shown to be dependent on pH and coupled to proton symport.8,11,12 On the other hand, microfluorescence imaging studies in primary macrophages with a metal-sensitive fluorescent probe have recently established that Nramp1 also acts as a divalent cation efflux pump at the phagosomal membrane.13 Genetic studies in rodent models of iron deficiency and microcytic anemia have shown that DMT1 is mutated (Gly185Arg) in the mk mouse and in the Belgrade(b) rat.6,14 Both the mk mouse and the b rat exhibit severe microcytic, hypochromic anemia due to a defect in iron uptake in the intestine but also in iron acquisition and utilization in peripheral tissues, including red blood cell (RBC) precursors.15 16

In the intestine, expression studies of mRNA8,17 and protein18 indicate that the DMT1 IRE-containing isoform I is expressed in the proximal portion of the duodenum, where it is dramatically up-regulated by dietary iron deprivation. DMT1 expression is restricted to the distal half of the villi, where it localizes to the brush border of absorptive epithelial cells.18Interestingly, mk/mk mice show a dramatic increase in expression of the Gly185Arg mutant variant of DMT1 (isoform I) in the duodenum, but little of the overexpressed protein is detected at the brush border of mk/mk enterocytes,19 suggesting that the Gly185Arg mutation impairs not only the transport properties,9 but also membrane targeting of the protein in mice. In mk and b animals, the Tf-dependent iron uptake by erythroid precursors is also impaired.16,20,21Immature erythroid cells are the most avid consumers of iron in mammals, for use in hemoglobin synthesis. Although non–Tf-bound iron uptake has been described in vitro,22 most of the iron is delivered to developing erythroid cells from Tf via receptor-mediated endocytosis.23 This involves binding of diferric Tf to transferrin receptor (TfR), internalization of Tf within endocytic vesicles, and the release of iron from the protein following endosomal acidification.23,24 The metal is then transported through the endosomal membrane via a Fe++ transporter, a step found to be impaired in b reticulocytes.22,25-27 In different cell lines, including murine erythroleukemia (MEL) cells, as well as in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO), HEK293, and RAW cells expressing a transfected DMT1 complementary DNA (cDNA), the protein is detected primarily in Tf-positive compartments, a colocalization that supports a role for DMT1 in Tf-derived iron uptake within acidified endosomes.9 28

Therefore, a large body of experimental data support the proposal that, in addition to its demonstrated role in iron acquisition at the intestinal brush border, DMT1 also transports iron across the membrane of acidified endosomes into the cytoplasm. The defect in iron acquisition noted in peripheral tissues of mk andb animals, in particular in reticulocytes, suggests an important role of DMT1 in erythroid cells precursors as well. Here, we used 2 anti-DMT1 antibodies to examine expression of the 2 DMT1 isoforms in reticulocytes and erythrocytes from either normal mice, mice treated with phenylhydrazine (PHZ) or erythropoietin (EPO) , and from anemic mk/mk mice. Our results show abundant expression of DMT1 isoform II in erythroid cell precursors, suggesting a key role of this isoform in Fe aquisition and heme biosynthesis. The poor expression of DMT1 in mk erythroid cells, together with the demonstrated loss of transport activity associated with the Gly185Arg mutation,9 may both contribute to the severe impairment of iron uptake in mk/mk erythroid cells leading to hypochromic microcytic anemia.

Materials and methods

Animal care

Inbred 129sv mice were initially obtained from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY), and subsequently maintained as a breeding colony. MK/Rej-mk/+ and MK/Rej-mk/mk mice (Dr Andrews, Children's Hospital, Boston, MA) were originally derived from founders purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Homozygotes mk/mk mice were identified among the offspring of an mk/+ intercross by genotyping, as previously described.14 CD1 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (St. Constant, QC, Canada) and subsequently maintained as a breeding colony.

Treatment with PHZ and EPO

Neutralized PHZ (50 mg/kg per day) was injected intraperitoneally on 2 consecutive days. Three days later, blood was taken by cardiac puncture of avertin-anesthestized mice using heparin as anticoagulant. Recombinant human EPO (Epress, Janssen-Ortho, North York, ON, Canada, 4000 IU/mL) was injected intraperitoneally (50 IU/mouse) on 3 consecutive days and blood samples were collected 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours after the last injection. Reticulocyte counts were performed after staining with new methylene blue. Membrane fractions from spleens and from cultured MEL cells were prepared as previously described.18 29 Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Cell culture

The CHO LR73 cells and MEL cells were cultured as previously described.18,30 The c-Myc-tagged DMT1 (isoform II), and Nramp1 cDNAs inserted in expression plasmid pMT2 were introduced into CHO cells by transfection using calcium phosphate coprecipitation method. The isolation and characterization of cell clones expressing high levels of each protein, including preparation of membrane fractions and immunoblotting were as described.18

Salicylaldehyde isonicotinoyl hydrazone and 2,2′-dipyridyl interception experiments

Reticulocytes (50 μL packed cells) obtained frommk/mk or EPO-treated mk/+ mice were suspended in 250 μL minimal essential medium (MEM) containing 25 mM HEPES,10 mM NaHCO3, pH 7.4.59Fe-Tf was added to the final concentration of 5 μM (in terms of Tf concentration). In appropriate groups, salicylaldehyde isonicotinoyl hydrazone (SIH) and 2,2′-dipyridyl (DP; Sigma, St Louis, MO) were added to the final concentration of 100 μM and 1 mM, respectively. Cells were then incubated for 60 minutes at 37°C in a shaking water bath, followed by 3 washes in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 4°C. In parallel experiments, 59Fe-Tf was incubated with MEM (without reticulocytes) in the presence of either SIH or DP. Heme-59Fe was extracted by methyl-ethyl ketone,31 and its radioactivity was measured using a gamma counter. For 59Fe-SIH or 59Fe-DP determinations, 200 μL cell mixture was lysed with 600 μL H2O, and proteins were precipitated (ethanol 100%, −20°C, 1 hour). After centrifugation (3000 rpm, 20 minutes),59Fe-SIH or 59Fe-DP radioactivities in the supernatant were measured. Reticulocyte-mediated transfer of59Fe to SIH or DP is expressed as a difference between radioactivities in the samples containing reticulocytes and those incubated without the cells. Following ethanol treatment, the precipitate contains 59Fe associated with protein (Tf, ferritin, hemoglobin, etc), whereas the supernatant contains59Fe-SIH or 59Fe-DP.

Preparation of RBC membranes

The RBCs (0.4 mL heparinized mouse blood) were washed several times with PBS (5 minutes, 5000-8000g), and the final pellet was resuspended in 2.5 mL of a lysis buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) and protease inhibitors (PIs; 2 μg/mL leupeptin; 2 μg/mL aprotinin, 1 μg/mL pepstatin; 100 μg/mL phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF] and 2 mM EDTA). The homogenate was then centrifuged at 14 000g for 10 minutes and this was repeated 3 times. The final “ghost” pellet was resuspended in 200 μL of a solubilization buffer (5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.5% Triton X-100 and PIs) and stored frozen at −80°C. All procedures were carried out at 4°C. Protein concentration of various membrane fractions was determined by the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad).

Immunoblotting

Crude membrane preparations from tissues (80-120 μg protein), RBCs (80 μg), MEL cells (100 μg), or CHO cells (5 μg protein) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE; 10% polyacrylamide), and transferred by electroblotting to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. Because heat treatment of DMT1-containing samples was found to cause aggregation of the protein, samples were incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature in Laemmli buffer (with occasional vortexing) prior to SDS-PAGE. Similar loading and transfer of proteins were verified by staining the blots with Ponceau S (Sigma). Immunoblots were preincubated with blocking solution (0.02% Tween 20, 7% skim milk in PBS) for 3 hours at 20°C, prior to incubation with primary antibodies for16 hours at 4°C in blocking solution. Primary antibodies recognizing either both DMT1 isoforms (anti–DMT1-NT; 1:200), or DMT1 isoform I (anti–DMT1-CT; 1:100) or a rabbit anti–Nramp1-NT (1:200), and rat monoclonal anti–mouse TfR (1:500) were used for immunoblotting exactly as we have previously described.18 28

Immunofluorescence

For confocal microscopy, CD1 mice were injected with EPO (100 U/d for 3 days), and blood was taken 48 hours later. Following centrifugation of blood, buffy coat was removed. In the RBC fraction, no white blood cells (mononuclear and polymorphonuclear cells) were found in smears by Giemsa staining. Cells were resuspended in MEM supplemented with 10 mM NaHCO3 and 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) at 15 × 106 reticulocytes/mL followed by 30 minutes of incubation at 37°C to eliminate endogenous Tf. Cells were washed once with PBS and resuspended in MEM containing Tf (Alexa-Tf; 500 nM; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Cells were incubated 30 minutes on ice, followed by 20 minutes at 37°C and 3 washes with PBS at 4°C. Cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde (30 minutes at 4°C), washed 3 times in PBS, and permeabilized with 0.05% NP-40 (Sigma) in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma) and 5% normal goat serum (Life Technologies, Montreal, QC, Canada) at 4°C for 30 minutes. Cells were blocked for 1 hour at room temperature in PBS containing 1% BSA, 10% goat serum, 10% CD1 mouse serum in PBS (1 hour, 20°C). Cells were washed and incubated with anti–DMT1-NT antibody (1:100, 1 hour, 20°C) followed by washing and incubation with the secondary rhodamine-coupled donkey anti–rabbit antiserum (1:200). Colocalization studies were performed using a Bio-Rad scanning confocal fluorescence microscope and digitizing equipment, as we have previously described.28

Results

DMT1 expression in spleens and reticulocytes from EPO-treated, PHZ-treated, and mk/mk mice

Erythroid precursors are avid consumers of iron during heme biosynthesis, and animals bearing loss-of-function mutations in theDMT1 gene show a profound defect in iron acquisition by peripheral tissues, including RBC precursors.16,20,21 32Therefore, the aims of the present study were to identify the cellular and subcellular site of DMT1 expression in mature or precursors RBCs and analyze its expression in genetically anemic mice (mk/mk), and in response to experimental treatments known to induce erythropoiesis.

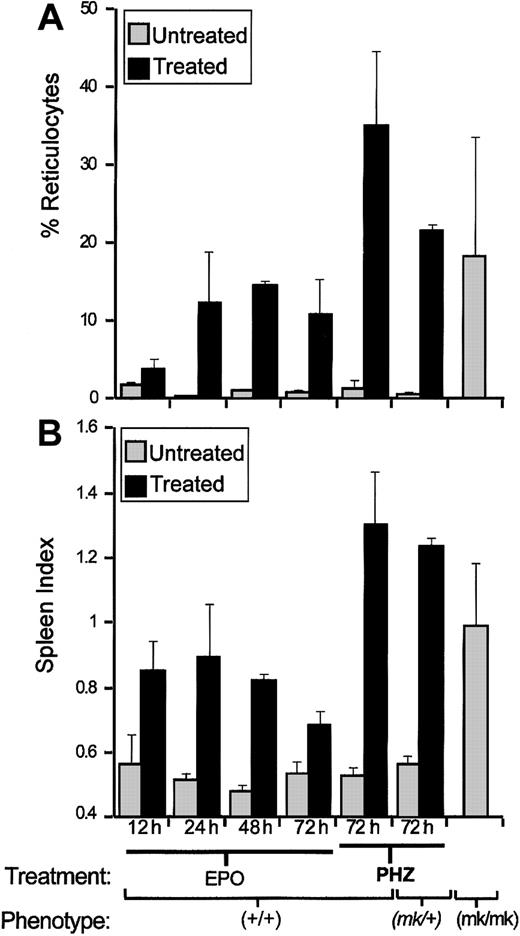

The 129sv mice were treated with EPO or PHZ, 2 agents known to induce reticulocytosis. EPO directly stimulates erythropoiesis, whereas PHZ causes profound anemia, which triggers vigorous EPO-mediated erythropoiesis both in the spleen and bone marrow. Erythropoiesis response was monitored after EPO and PHZ treatments (see “Materials and methods”), by recording splenomegaly (spleen index [SI]), and enumerating reticulocytes in blood samples (percent of total RBCs; Figure 1). Compared to saline-injected control mice, both EPO and PHZ treatments induced strong reticulocytosis (Figure 1A) consistent with splenomegaly (Figure 1B). Both responses were stronger in PHZ-treated (35% reticulocytes; SI = 1.3) than in EPO-treated mice (15% reticulocytes; SI = 0.9). The microcytic anemia induced in mk/mk mice by loss of DMT1 function is concomitant to enhanced reticulocytosis. Indeed, homozygous mk/mk mice show increased splenomegaly (SI = 1) and increased reticulocytosis (11.4%, 35.8%, and 8.3%) when compared with normal mk/+ heterozygotes 0.4,% 0.8%, and 0.8%) or 129sv controls (SI ≤ 0.5; < 2% reticulocytes). As observed for wild-type mice, PHZ treatment ofmk/+ heterozygotes caused a splenomegaly response (SI = 1.24) and blood reticulocytosis (21.7% ± 0.6%), which were similar to those seen in normal mice similarly treated. These results indicate robust splenic erythropoietic response occurring either naturally in mk/mk mutants lacking DMT1 function or induced by treatment with EPO or during recovery from PHZ-induced hemolytic anemia.

Reticulocytosis and splenomegaly in EPO- or PHZ-treated mice and in

mk/mk mice. Wild-type animals (129sv) ormk/+ heterozygotes were treated with either EPO or PHZ. Blood samples and spleens were collected at indicated times after the last injection and also from untreated mk/mk homozygotes. Reticulocyte counts (A) and spleen index (B; SI = ) were calculated for each group (2 or 5 mice in each). Results are expressed as means ± SD.

Reticulocytosis and splenomegaly in EPO- or PHZ-treated mice and in

mk/mk mice. Wild-type animals (129sv) ormk/+ heterozygotes were treated with either EPO or PHZ. Blood samples and spleens were collected at indicated times after the last injection and also from untreated mk/mk homozygotes. Reticulocyte counts (A) and spleen index (B; SI = ) were calculated for each group (2 or 5 mice in each). Results are expressed as means ± SD.

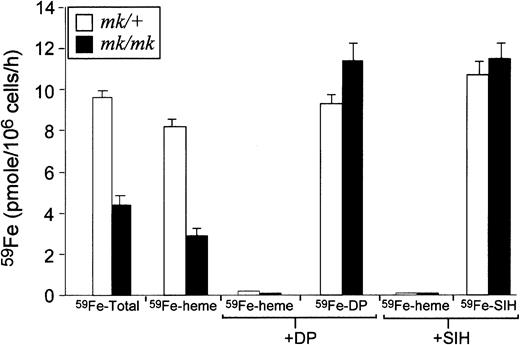

Although impaired iron assimilation by erythroid cells ofmk/mk mice has been reported,20,21 defects in Tf-mediated iron transport are poorly characterized in these animals. To clarify mechanisms underlying impaired utilization of Tf-bound iron by mk/mk erythroid cells, reticulocytes frommk/mk and mk/+ (following EPO treatment) mice were incubated with 59Fe-labeled Tf following which59Fe uptake by the cells and its incorporation into heme were measured. Two permeable Fe chelators, SIH (binds Fe+++and Fe++) and DP (binds Fe++ only) were exploited to estimate relative levels of Fe+++ and Fe++ present in endosomes of reticulocytes frommk/+ and mk/mk mice. In these experiments, no significant difference was seen in total cellular iron uptake between wild-type +/+ (9.7 ± 0.1 pmoles/106 cells per hour) andmk/+ (9.6 ± 0.3 pmoles/106 cells per hour). On the other hand, as compared to mk/+ cells,mk/mk reticulocytes had decreased cellular 59Fe uptake (4.4 ± 0.5 versus 9.6 ± 0.3 pmoles/106 cells per hour) and exhibited a significant inhibition of 59Fe incorporation into heme (3 ± 0.2 versus 8.3 ± 0.1 pmoles/106 cells per hour; Figure2). The reduced rate of heme synthesis inmk/mk mice was not due to a defect in heme synthesis pathway because the heme synthesis rate can be brought to the control levels by means of non-Tf Fe donor (Fe-SIH, not shown). Neither SIH nor DP affected Tf cycle (data not shown) but these chelators completely inhibited heme synthesis in both mk/+ and mk/mkreticulocytes. Importantly, the rates of 59Fe transfer from59Fe-Tf to DP or SIH were not decreased in mk/mkreticulocytes, suggesting that in mk/mk reticulocytes the endosomal Fe metabolism (Fe release from Tf and its reduction by a putative Fe+++ reductase) are functionally normal. These results indicate that the basic defect in mk/mkreticulocytes, as in those from brats,22 25-27 resides in an impaired Fe++transport efficiency across the endosomal membrane.

Rates of iron uptake and heme synthesis, SIH- and DP-interceptable Fe in reticulocytes obtained from

mk/+ or mk/mk mice.Tf-associated Fe uptake and its subsequent utilization for heme synthesis as well as Fe release from Tf and its subsequent reduction in the endosomal lumen of mk/mk reticulocytes were investigated using Tf- labeled with 59Fe and 2 membrane permeable Fe chelators, SIH (binds Fe+++ and Fe++) and DP (binds Fe++ only). The results obtained withmk/mk reticulocytes (black bars) were compared with those obtained using reticulocytes from EPO-treated mk/+ mice (white bars). Compared to mk/+, in mk/mkreticulocytes, total cellular 59Fe uptake and the rate of heme synthesis are reduced whereas the rate of 59Fe transfer from 59Fe-Tf to DP or SIH are unchanged .

Rates of iron uptake and heme synthesis, SIH- and DP-interceptable Fe in reticulocytes obtained from

mk/+ or mk/mk mice.Tf-associated Fe uptake and its subsequent utilization for heme synthesis as well as Fe release from Tf and its subsequent reduction in the endosomal lumen of mk/mk reticulocytes were investigated using Tf- labeled with 59Fe and 2 membrane permeable Fe chelators, SIH (binds Fe+++ and Fe++) and DP (binds Fe++ only). The results obtained withmk/mk reticulocytes (black bars) were compared with those obtained using reticulocytes from EPO-treated mk/+ mice (white bars). Compared to mk/+, in mk/mkreticulocytes, total cellular 59Fe uptake and the rate of heme synthesis are reduced whereas the rate of 59Fe transfer from 59Fe-Tf to DP or SIH are unchanged .

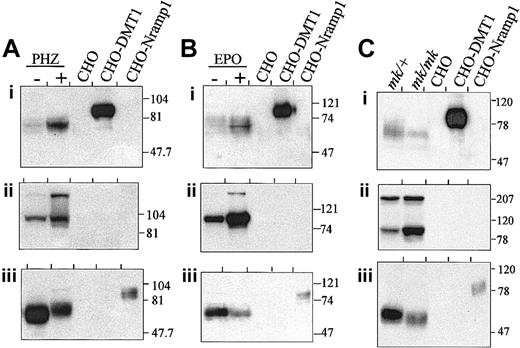

Thus far, the expression of DMT1 protein in erythroid cells including cellular and subcellular localization, has not been studied. Membrane fractions were prepared from spleens of normal, PHZ-treated (Figure3A), or EPO-treated animals (Figure 3B), as well as from mk/+ and mk/mk mutants (Figure3C), separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting. Immunodetection was done with an affinity-purified polyclonal rabbit anti-DMT1 antiserum directed against the amino terminus of the protein (DMT1-NT) (Figure 3Ai,Bi,Ci). Membrane fractions from CHO cells transfected with either Nramp1 (CHO-Nramp1) or DMT1 isoform II (CHO-DMT1) were included as negative and positive controls, respectively. Low-level expression of immunoreactive DMT1 of apparent molecular mass 70 kd was detected in spleen membranes from control mice (−; Figure 3Ai,Bi) and normal mk/+ heterozygotes (Figure 3Ci). Treatment with PHZ (Figure 3Ai) and to a lesser extent EPO (Figure 3Bi) was associated with increased expression of DMT1 in spleen, whereas in mk/mk mice that have a spontaneous reticulocytosis, no such increase, but a possible decrease (when compared to mk/+), was observed (Figure 3Ci). The DMT1 isoform detected in spleen showed faster electrophoretic mobility (70 kd) than that seen in the control DMT1 CHO transfectants (CHO-DMT1, 80-90 kd), indicating possible cell-specific differences in posttranslational modification of the protein. Parallel studies in Figure 3Aii, Bii, and Cii indicate that PHZ and EPO treatment of normal mice also resulted in increased expression of the TfR (≈90-kd band) in these samples, in agreement with strong erythroid expansion in the spleen of these animals. Likewise, increased TfR expression was noted in mk/mk spleen when compared to mk/+ controls, in agreement with constitutive reticulocytosis in mk/mkspleens (Figure 1). A high-molecular-weight immunoreactive species was sometimes detected with the anti-TfR antibody and likely corresponds to dimeric form (≈180 kd) of the receptor that resists the mild denaturing conditions used in our experiment (see “Materials and methods”). Finally, expression of the macrophage-specific Nramp1 protein33 was monitored in the same samples (Figure 3Aiii,Biii,Ciii). As previously observed,18 Nramp1 was expressed as an abundant 65-kd protein in spleens of control (−) andmk/+ animals. As opposed to DMT1, treatment with PHZ and EPO was associated with decreased expression of Nramp1 in control (−) spleens, and a similar situation was observed in mk/mk when compared to mk/+ spleens. Together, these results showed that reticulocytosis induced by PHZ and EPO treatment results in increased DMT1 detection, paralleled by a concomitant increase in TfR expression, and suggest that, like TfR, DMT1 is expressed in reticulocytes present in the spleen. On the other hand, dilution of mononuclear phagocytes in the spleen by expansion of the erythroid compartment may be responsible for the net decrease in Nramp1 signal on blot. Finally, although increased reticulocytosis (Figure 1), and elevated TfR expression are noted in mk/mk cells, there does not appear to be any increase in DMT1 expression in mk/mkspleen, suggesting an alteration in DMT1 expression, stability, or targeting of the protein in mk/mk reticulocytes.

Splenic expression of DMT1.

Expression of DMT1 in the spleens of PHZ- (A) or EPO- (B) (48 hour) treated mice and in the spleen of mk/mk (C) mice. Spleen microsomal fractions (80 μg) together with 5 μg membrane proteins prepared from CHO cells or CHO transfectants expressing either a cMyc-tagged DMT1 isoform II (CHO-DMT1) or a cMyc-tagged mNramp1 (CHO-Nramp1) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti–DMT1-NT (i), anti-TfR (ii), and anti– mNramp1-NT (iii) antisera. The positions and sizes (in kilodaltons) of molecular mass markers are shown.

Splenic expression of DMT1.

Expression of DMT1 in the spleens of PHZ- (A) or EPO- (B) (48 hour) treated mice and in the spleen of mk/mk (C) mice. Spleen microsomal fractions (80 μg) together with 5 μg membrane proteins prepared from CHO cells or CHO transfectants expressing either a cMyc-tagged DMT1 isoform II (CHO-DMT1) or a cMyc-tagged mNramp1 (CHO-Nramp1) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti–DMT1-NT (i), anti-TfR (ii), and anti– mNramp1-NT (iii) antisera. The positions and sizes (in kilodaltons) of molecular mass markers are shown.

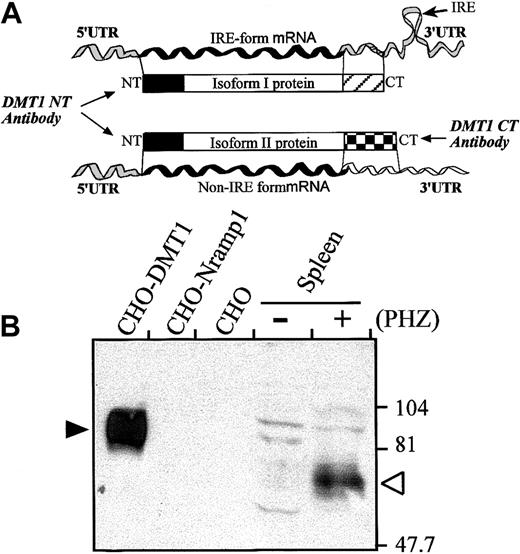

DMT1 isoform II is expressed in the spleen of PHZ-treated mice

By alternative splicing, DMT1 produces 2 products that can be distinguished by the presence (IRE, isoform I) or absence (non-IRE, isoform II) of an IRE in the 3′ UTR, as well as distinct C-terminal peptide sequences (Figure 4A). To gain information into which of the 2 DMT1 isoforms is expressed during erythropoiesis in the spleen, an immunoblot containing membrane fractions from spleens of control and PHZ-treated animals was analyzed with an isoform II–specific rabbit anti-DMT1 antiserum (anti–DMT1-CT) (Figure 4A,B). This anti–DMT1-CT antiserum detected a specific immunoreactive product in the PHZ-treated spleen (Figure 4B; open arrowhead), with apparent electrophoretic mobility (≈70 kd) similar to the DMT1 species detected by the anti–DMT1-NT antiserum (Figure 3). The DMT1 isoform II observed in the spleen migrated considerably faster than the same protein overexpressed in CHO transfectants (Figure 4B; filled arrowhead).

DMT1 isoform II is expressed in the spleen of PHZ-treated mice.

(A) Schematic representation of the 2 DMT1 mRNAs (IRE-containing and non–IRE-containing form generated by alternative splicing) and corresponding proteins (isoform I and II, respectively). The 2 isoforms show distinct 3′ UTR and encode polypeptides with distinct carboxy termini (hatched boxes). The DMT1-NT antibody recognizes the N-terminus of both isoforms I and II (solid boxes), whereas the DMT1-CT antibody was raised against the carboxy-terminal extremity of isoform II. (B) Microsomal spleen fractions (120 μg) from control (−) or PHZ-treated (+) mice were analyzed by immunoblotting with the DMT1-CT antiserum. Membrane proteins (5 μg) from CHO cells or CHO transfectant expressing either a cMyc-tagged DMT1 isoform II (CHO-DMT1) or a cMyc-tagged mNramp1 (CHO-Nramp1) were included as controls. The positions and sizes (in kilodaltons) of molecular mass markers are indicted on the right.

DMT1 isoform II is expressed in the spleen of PHZ-treated mice.

(A) Schematic representation of the 2 DMT1 mRNAs (IRE-containing and non–IRE-containing form generated by alternative splicing) and corresponding proteins (isoform I and II, respectively). The 2 isoforms show distinct 3′ UTR and encode polypeptides with distinct carboxy termini (hatched boxes). The DMT1-NT antibody recognizes the N-terminus of both isoforms I and II (solid boxes), whereas the DMT1-CT antibody was raised against the carboxy-terminal extremity of isoform II. (B) Microsomal spleen fractions (120 μg) from control (−) or PHZ-treated (+) mice were analyzed by immunoblotting with the DMT1-CT antiserum. Membrane proteins (5 μg) from CHO cells or CHO transfectant expressing either a cMyc-tagged DMT1 isoform II (CHO-DMT1) or a cMyc-tagged mNramp1 (CHO-Nramp1) were included as controls. The positions and sizes (in kilodaltons) of molecular mass markers are indicted on the right.

DMT1 isoform II protein is expressed in normal RBC membrane

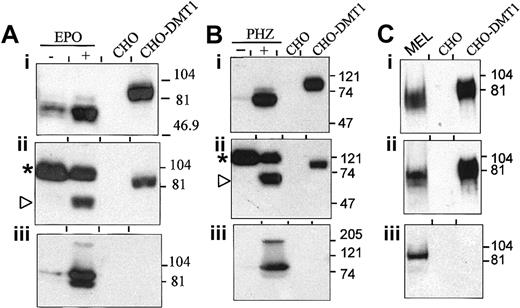

Expression of DMT1 protein was then measured in membrane fractions (erythrocyte ghosts) prepared directly from heparinized blood of normal mice, treated or not with EPO (Figure 5A) or PHZ (Figure 5B). DMT1 expression was also monitored in Friend erythroleukemia virus–transformed MEL erythroblastoid cells (Figure5C). Immunoblots were analyzed using either the anti–DMT1-NT (Figure 5Ai,Bi,Ci; recognizes isoforms I and II), or the anti–DMT1-CT (Figure5 Aii,Bii,Cii; isoform II specific) or anti-TfR antisera (Figure 5Aiii,Biii,Ciii). The DMT1-NT–reactive 70-kd protein (Figure 5Ai,Bi) was expressed at low levels in circulating RBCs from normal mice, and its expression was dramatically increased in similar samples from PHZ- and EPO-treated animals. The stronger DMT1 expression seen in blood from PHZ-treated than EPO-treated animals parallels both immunoblotting results with spleen membranes (Figure 3), and the extent of reticulocytosis in these groups (Figure 1). The 70-kd DMT1 species was also detected with our anti–DMT1-CT antibody in the RBC membranes after EPO and PHZ treatment (Figure 5Aii,Bii, open arrowheads). An additional prominent cross-reactive species of slower mobility was also detected by this antiserum in membranes from both untreated and treated mice (Figure 5Aii,Bii; asterisks). The identity of this cross-reactive species is currently unknown; however, the size of this protein (> 100 kd), its restricted expression in RBCs, together with its lack of reactivity with the non–isoform-specific DMT1-NT antiserum strongly suggest that it corresponds to a protein unrelated to DMT1 but expressed at high levels in RBCs. The expression of TfR in those samples paralleled that of DMT1 and was strongly enhanced during EPO-induced (Figure 5Aiii) or PHZ-induced (Figure 5Biii) reticulocytosis. Finally, results in Figure 5C show that MEL erythroid cells express abundant levels of DMT1 (70 kd) that is immunoreactive with both the anti–DMT1-NT and -CT antisera indicating high-level expression of isoform II in these cells. Together, these results combined with those obtained with splenic membranes (Figures 3and 4) identify the erythroid compartment as a normal physiologic site of expression of non-IRE DMT1 isoform II, as opposed to the intestine, which is the primary site of the IRE-containing isoform I.18

DMT1 expression in RBCs of normal mice.

(A-B) Immunoblotting of ghost RBC membranes (80 μg) isolated from control animals (−) or mice treated with EPO (48 hours, +, A) or PHZ (+, B). (C) Western blot analysis of crude membrane fractions (100 μg) obtained from MEL cells. Membrane proteins (5 μg) from control CHO cells (CHO) and CHO transfectant expressing a cMyc-tagged DMT1 isoform II (CHO-DMT1) were used as controls. Immunoblotting was performed with antibodies raised against DMT1-NT (i), DMT1-CT (ii), and TfR (iii). The asterisk indicates the position of an unspecific protein species detected only with our anti–DMT1-CT. The positions and sizes (in kilodaltons) of molecular mass markers are shown.

DMT1 expression in RBCs of normal mice.

(A-B) Immunoblotting of ghost RBC membranes (80 μg) isolated from control animals (−) or mice treated with EPO (48 hours, +, A) or PHZ (+, B). (C) Western blot analysis of crude membrane fractions (100 μg) obtained from MEL cells. Membrane proteins (5 μg) from control CHO cells (CHO) and CHO transfectant expressing a cMyc-tagged DMT1 isoform II (CHO-DMT1) were used as controls. Immunoblotting was performed with antibodies raised against DMT1-NT (i), DMT1-CT (ii), and TfR (iii). The asterisk indicates the position of an unspecific protein species detected only with our anti–DMT1-CT. The positions and sizes (in kilodaltons) of molecular mass markers are shown.

Expression of DMT1 protein in mk/mk RBC membranes

Expression of DMT1 was analyzed in membrane fractions prepared from heparinized blood of mk/+, mk/mk, and PHZ-treated mk/+ mice (anti–DMT1-NT; Figure6Ai,Bi). For comparison, DMT1 detection was monitored in parallel using RBC membranes from normal and EPO-treated wild-type mice (Figure 6Ai). The degree of reticulocytosis associated with these treatments (Figure 6Aiii,Biii), and the level of TfR expression in the corresponding samples (Figure 6Aii,Bii) were also measured and are shown. Blood specimens from mk/+ controls show low reticulocyte counts in the normal range (Figure 6Aiii, bar 3; Figure 6Biii, bar 2), and membrane fractions from these samples show low levels of DMT1 (Figure 6Ai,Bi) and TfR expression (Figure 6Aii,Bii). PHZ treatment of mk/+ mice resulted in robust reticulocytosis (Figure 6Biii, bar 1), which was similar to that seen for normal +/+ controls treated with EPO (Figure 6Aiii, bar 2), and was concomitant to a strong increase in DMT1 (Figure 6Bi) and TfR (Figure 6Bii) in RBC membrane fractions from these mice. On the other hand, membrane fractions prepared from heparinized blood of mk/mkmice showed little if any DMT1 expression when compared to normalmk/+ controls (Figure 6Ai,Bi), and this despite constitutive reticulocytosis (Figure 6Aiii, bar 4; Figure 6Biii, bar 3) associated with increased TfR expression in these membrane fractions (Figure 6Aii,Bii). After longer exposures (not shown), DMT1 was poorly detected in membranes prepared from mk/mk RBCs, suggesting only residual expression of the mutated protein. These results indicate that the loss-of-function mutation at DMT1 in mk mice affects not only protein function but may also affect stability or targeting of the protein in reticulocytes.

DMT1 expression in red blood cells from microcytic anemia

(mk) mice. Panels A and B represent 2 independent immunoblots of crude membrane fractions from RBCs isolated from heterozygotes mk/+ and from homozygotesmk/mk mice. Membrane proteins from +/+ mice untreated or treated with EPO [+/+(+EPO)] (A), from mk/+mice treated with PHZ [mk/+(+PHZ)] (B), or from CHO cells (CHO) and CHO transfectants expressing DMT1 isoform II (CHO-DMT1) (A and B), were used as controls. Immunoblotting was performed using antibodies raised against DMT1-NT (Ai and Bi) or TfR (Aii and Bii). The positions and sizes (in kd) of molecular mass markers are shown. (Aiii) Percentage of reticulocytes in blood samples isolated from +/+ (1), +/+ (+ EPO) (2), and mk/+ (3) and mk/mk (4). (Biii) Percentage of reticulocytes in blood samples isolated frommk/+(+PHZ) (1), mk/+ (2), andmk/mk (3).

DMT1 expression in red blood cells from microcytic anemia

(mk) mice. Panels A and B represent 2 independent immunoblots of crude membrane fractions from RBCs isolated from heterozygotes mk/+ and from homozygotesmk/mk mice. Membrane proteins from +/+ mice untreated or treated with EPO [+/+(+EPO)] (A), from mk/+mice treated with PHZ [mk/+(+PHZ)] (B), or from CHO cells (CHO) and CHO transfectants expressing DMT1 isoform II (CHO-DMT1) (A and B), were used as controls. Immunoblotting was performed using antibodies raised against DMT1-NT (Ai and Bi) or TfR (Aii and Bii). The positions and sizes (in kd) of molecular mass markers are shown. (Aiii) Percentage of reticulocytes in blood samples isolated from +/+ (1), +/+ (+ EPO) (2), and mk/+ (3) and mk/mk (4). (Biii) Percentage of reticulocytes in blood samples isolated frommk/+(+PHZ) (1), mk/+ (2), andmk/mk (3).

Subcellular localization of DMT1 in the RBCs

The subcellular localization of DMT1 was then investigated in erythroid cells by immunofluorescence, using heparinized blood from normal mice treated with EPO. RBCs were prepared and labeled with Alexa-conjugated Tf (Alexa-Tf) before fixation and immunostaining with the anti–DMT1-NT antiserum (see “Materials and methods”). Analysis by confocal microscopy (Figure 7) indicated that in a small fraction of RBCs (approximately 10%), Tf (green) produced a punctate intracellular staining consistent with a localization in recycling endosomes (Figure 7B,F). It is very likely that these Tf-positive cells correspond to immature erythroid cells (about 10% by methylene blue staining). A similar staining was observed in the same percentage of cells with the anti–DMT1-NT antiserum (red, Figure 7C,G; arrowhead). Superimposition of the 2 images (Figure 7D,H) clearly shows overlapping staining (yellow) of the 2 signals. A large number of cells corresponding to mature erythrocytes did not stain for either DMT1 or Tf (Figure 7B-C, arrows). Together, these results confirm that DMT1 is expressed in erythroid cell precursors and indicate that DMT1 partially colocalizes with Tf in the early recycling endosomal compartment of these cells.

Immunofluorescence analysis of DMT1 and Tf in RBCs.

Cells were incubated with Alexa-conjugated Tf (Alexa-Tf) before fixation and immunostaining with anti–DMT1-NT antibody and a rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody. The slides were then examined by confocal microscopy (approximate depth of the optical sections = 1 μm), and the Alexa-TF (green; B,F) and rhodamine (red; C,G) images were overlaid (yellow identifies overlapping staining; D,H). In erythroid cell precursors (arrowhead in A and cell in E), the DMT1 staining (C,G) showed extensive overlapping staining with the distribution of Alexa-Tf (B+C = D and F+G = H; arrowhead). On the other hand, erythrocytes (arrows in panel A) were negative for both Alexa-Tf (arrows in panel B) and DMT1 (arrows in panel C) staining. Original magnification for A-D, × 400; E-H, × 1000.

Immunofluorescence analysis of DMT1 and Tf in RBCs.

Cells were incubated with Alexa-conjugated Tf (Alexa-Tf) before fixation and immunostaining with anti–DMT1-NT antibody and a rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody. The slides were then examined by confocal microscopy (approximate depth of the optical sections = 1 μm), and the Alexa-TF (green; B,F) and rhodamine (red; C,G) images were overlaid (yellow identifies overlapping staining; D,H). In erythroid cell precursors (arrowhead in A and cell in E), the DMT1 staining (C,G) showed extensive overlapping staining with the distribution of Alexa-Tf (B+C = D and F+G = H; arrowhead). On the other hand, erythrocytes (arrows in panel A) were negative for both Alexa-Tf (arrows in panel B) and DMT1 (arrows in panel C) staining. Original magnification for A-D, × 400; E-H, × 1000.

Discussion

The present studies show that erythroid cell precursors are a major site of expression of DMT1 protein. Western analyses of membrane fractions from spleen, a major site of erythropoiesis in mice, have shown that the level of DMT1 isoform II and TfR expression positively correlate with reticulocytosis induced by EPO and PHZ treatment. Similar results were obtained using membrane fractions prepared from heparinized blood of animals undergoing reticulocytosis. These results suggest concomitant expression of the DMT1 isoform II and TfR in immature erythroid cells, in agreement with the known requirement for iron of these cells. Additional evidence for this was provided by immunofluorescence studies and confocal microscopy that identified DMT1 staining in immature erythroid cells, sharing overlapping distribution with Tf. Expression of DMT1 isoform II in young RBCs and during reticulocytosis suggests that it may transport iron across the membrane of acidified endosomes and into the cytoplasm of erythroid precursor cells. This proposal is in agreement with (1) the overlapping intracellular staining of Alexa-Tf and DMT1 reported here for reticulocytes; (2) the observation that the depressed59Fe-heme synthesis noted in mk/mk reticulocytes expressing a mutant DMT1 protein does not rest with impaired iron release from Tf inside the endosome, nor reduction of Fe+++to Fe++ (Figure 2); (3) the recent demonstration that isoform II of DMT1 expressed in CHO cells can transport Fe++ into the calcein-accessible labile iron pool.11

DMT1 plays a key role in iron acquisition at the brush border of the duodenum.14,18 19 As opposed to absorptive cells of intestinal villi that express exclusively the IRE-containing isoform I of DMT1, analysis of erythroid cell (blood and MEL cells) expression with antibodies directed against either the amino terminus (isoform I + II) or the carboxy terminus of DMT1 (isoform II specific) suggest that the non–IRE-containing isoform II is the major DMT1 isoform expressed in erythroid cell precursors. However, because we do not have available an isoform-specific anti–isoform I antibody, the possibility that this isoform is also present at low levels in reticulocyte membranes cannot be excluded.

The isoform II of DMT1 expressed in erythroid cells showed an apparent molecular mass of approximately 70 kd, in agreement with the mass predicted from cDNA sequence (62.3 kd). The observed 70-kd mass is smaller than the 80 to 100 kd measured for DMT1 isoform II expressed in transfected CHO cells. Because up to 50% of the molecular mass of the DMT1 isoform II expressed in CHO cells is contributed by N-linked glycosylation,28 it is likely that the differences in electrophoretic mobility of isoform II measured in erythroid versus CHO cells result from distinct posttranslational modifications of the protein. In addition, isoform I of DMT1 expressed at the intestinal brush border of epithelial cells shows a molecular mass of 80 to 90 kd, when analyzed by immunoblotting with the same antibody and the same gel,18,19,34 suggesting likely modification by glycosylation. Such a modification may provide protection against degradative attacks by the intestinal content, or may be important for proper maturation and targeting of the protein to the apical pole of intestinal enterocytes,35 requirements that may not be relevant for DMT1 isoform II expression in the Tf-positive compartment of erythroid cells. Therefore, our results suggest considerable heterogeneity in posttranslational modification of isoforms I and II in different cell types and tissues, perhaps contributing to variability of molecular mass reported for DMT1 by different groups.9,12 Finally, we have also noted large differences in the apparent molecular mass of the close DMT1 homologue Nramp1, as estimated by SDS-PAGE either in primary macrophages,33 or in transfected CHO and RAW.2647,18 36 or in membrane fractions from total spleen (this study), varying between 110 kd, 90 kd, and 65 kd, respectively. The role of posttranslational modifications of DMT1 and Nramp1 by glycosylation, phosphorylation, or others on the activity and transport properties of these proteins remains to be characterized.

The DMT1 mRNA coding isoform II does not contain in its 3′ UTR the IRE characteristic of isoform I.6,7 IREs are bound by a set of regulatory proteins (IRP, or IRE- binding proteins) that together ultimately regulate stability and translation of mRNAs such as TfR and ferritin in response to iron availability.37-39Furthermore, it has been proposed that in erythroid cells additional mechanisms such as transcriptional control may play an important role in regulation of TfR expression.23 The absence of IRE in the DMT1 isoform II expressed in reticulocytes suggests that DMT1 may not be regulated by iron status in erythroid cells. The high level of expression of DMT1 and TfR noted in membrane fractions from spleen and circulating RBCs from normal mice undergoing reticulocytosis in response to PHZ and EPO treatment may simply reflect expansion of the TfR/DMT1-positive reticulocyte pool without any modulatory activity at the mRNA or protein levels in response to iron. This proposition is supported by the observation that DMT1 isoform II protein levels in MEL cells are insensitive to exposure of these cells to high concentrations of iron or iron chelators (unpublished results, 2001). This is in sharp contrast to the DMT1 isoform I expressed in duodenum, which is clearly regulated by iron stores possibly via the IRE/IRP system.18 19 The precise characterization of transcriptional or posttranscriptional regulation of DMT1 expression in erythroid cells (if any) remains to be clarified.

Loss of function in mk/mk mice is associated with constitutive reticulocytosis, a compensatory response by these mice to the chronic defect in the synthesis of functional heme due to lack of available Fe++. Despite robust reticulocytosis and strong expression of TfR, mk/mk reticulocytes show very little, if any, DMT1 protein. This is in contrast with EPO- and PHZ-treated mice, where expansion of the erythroid pool is concomitant to increased expression of both DMT1 and TfR proteins. Although, we cannot rule out the possibility that the Gly185Arg mutation of mk/mk mice may have an unknown effect on expression of the protein (mRNA stability, translation, or other), these findings suggest that the Gly185Arg mutation may affect either stability or targeting of DMT1 to a functional site in erythroid cells. We have previously reported up-regulation of the Gly185Arg variant (isoform I) expression inmk/mk enterocytes, but the protein was not properly targeted to the brush border, a defect that may contribute to the systemic iron deficiency and the severe anemia in mice.19 Although the DMT1 protein (isoform I) could be readily detected in membrane fractions from mk/mk intestine, and thus is not rapidly degraded, it is possible that the targeting defect associated with the Gly185Arg mutation may have more severe consequences on the stability of the protein in reticulocytes (mostly isoform II) than enterocytes inmk/mk mice. Interestingly, a recent study by immunofluorescence suggested that b/b reticulocytes express similar quantities of DMT1 when compared to normal or b/+ reticulocytes.40 The possible cause of differences betweenmk mice and b rat remains to be clarified.

The Nramp2/DMT1 gene was initially cloned by virtue of its cross-hybridization to the Nramp1 gene.41 InNramp1, a single Gly169Asp mutation in predicted TM4, impairs macrophage function and causes susceptibility to infections by intracellular pathogens. Interestingly, Gly169Asp in Nramp1is immediately adjacent to the Gly185Arg mutation in the TM4 of DMT1 inmk mice. The Gly169Asp mutation in Nramp1 results in absence of mature polypeptide, as a result altered targeting and stability of the protein.33 Therefore, there is considerable similarity between the genotype and phenotype of the 2 known loss-of-function missense mutations in these 2 members of theNramp family. A residual expression of Gly185Arg DMT1 isoform II detected in mk/mk erythroid precursors, in addition to the residual activity of the mutated DMT1 demonstrated by Su and coworkers,9 likely contributes to the survival of homozygotes mk/mk mice. However, mk/mkreticulocytes have about 45% of normal Fe uptake (Figure 2) suggesting that an alternative iron transporter may be active in these cells.

Supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant AI355237 (to P.G.), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) grant MT-14100 (to P.P.), and Milestone Medica Corporation Award grant (to F.C-H.) P.G. is an International Research Scholar of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) and a Senior Scientist of the CIHR.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Philippe Gros, Department of Biochemistry, McGill University, 3655 William Osler Promenade, Rm 907, Montreal, QC, Canada, H3G-1Y; e-mail: gros@med.mcgill.ca.

![Fig. 6. DMT1 expression in red blood cells from microcytic anemia. / (mk) mice. Panels A and B represent 2 independent immunoblots of crude membrane fractions from RBCs isolated from heterozygotes mk/+ and from homozygotesmk/mk mice. Membrane proteins from +/+ mice untreated or treated with EPO [+/+(+EPO)] (A), from mk/+mice treated with PHZ [mk/+(+PHZ)] (B), or from CHO cells (CHO) and CHO transfectants expressing DMT1 isoform II (CHO-DMT1) (A and B), were used as controls. Immunoblotting was performed using antibodies raised against DMT1-NT (Ai and Bi) or TfR (Aii and Bii). The positions and sizes (in kd) of molecular mass markers are shown. (Aiii) Percentage of reticulocytes in blood samples isolated from +/+ (1), +/+ (+ EPO) (2), and mk/+ (3) and mk/mk (4). (Biii) Percentage of reticulocytes in blood samples isolated frommk/+(+PHZ) (1), mk/+ (2), andmk/mk (3).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/98/13/10.1182_blood.v98.13.3823/6/m_h82411842006.jpeg?Expires=1769097877&Signature=mTIFYpEG-X7bGMpPUFxPO4Hhil85YZjtaiQnwToqbg9Aw8aaNPlSyBSd47pNQ1VxApsEgagb84UJ5tbrsKk~aL-6-LpTEM4J12hysZUUJzrtQ6v1wEPQrbvPE-15VSHIYWZ9AIqXgP-cP3NbJfDBBBBQqCimVuzqHryOPwOqSTtEV5-H-0fQoBYmRmePkWybILfuzBCbFTOhe2pD-sGJkDWqZAf0b13ShCTQbxFrQ2JG1uGXvQw2yA~xLf6lIZCjZCjVpR6SqI~3WpYTueVAgh6G~jECYqv6QHIrwm9uOyOAjDSUJ7kl8ruygp9CpNfXNmJN6AWXLdgIMoQUKj63yA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal