Abstract

Successful immunologic control of HIV infection is achieved only in rare individuals. Dendritic cells (DCs) are required for specific antigen presentation to naive T lymphocytes and for antiviral, type I interferon secretion. Two major blood DC populations are found: CD11c+ (myeloid) DCs, which secrete IL-12, and CD123+ (IL-3–receptor+) DCs (lymphoid), which secrete type I interferons in response to viral stimuli. The authors have previously found a decreased proportion of blood CD11c+ DCs in chronic HIV+ patients. In this study, 26 to 57 days after infection and before treatment, CD123+ and CD11c+ DC numbers were dramatically reduced in 13 HIV+ patients compared with 13 controls (P = .0002 and P = .001, respectively). After 6 to 12 months of highly active antiretroviral therapy, DC subpopulation average numbers remained low, but CD123+ DC numbers increased again in 5 of 13 patients. A strong correlation was found between this increase and CD4 T-cell count increase (P = .0009) and plasma viral load decrease (P = .009). Reduced DC numbers may participate in the functional impairment of HIV-specific CD4+ T cells and be responsible for the low type I interferon responsiveness already known in HIV infection. The restoration of DC numbers may be predictive of immune restoration and may be a goal for immunotherapy to enhance viral control in a larger proportion of patients.

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is fought by the immune system with limited success. The primary stage is critical. During the first days after infection, the virus replicates to reach high plasma levels, then decreases. CD4+ T lymphocytes are the main targets of infection. CD4 T-cell counts drop, then rise again to subnormal levels, and functional proliferative and T-helper 1 (TH1)–type secretion responses to HIV antigens are impaired, including interleukin 2 (IL-2) production.1-3CD8+ T lymphocyte responses are not as high in primary HIV infection as in other viral infections and are impaired at later stages of disease.1,4-6 After 6 months, the plasma viral load reaches a set point which is correlated with the probability of survival, and convergent evidence has shown the crucial role of HIV-specific CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T-helper cells.7-9 Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has changed the prognosis.10 Under treatment, CD4 cell counts increase again. HIV-specific CD4+ functional response restoration appears limited,11 but can be obtained when HAART is initiated very early after acute infection,1,12,13 and even in chronic infection, after prolonged periods of viral suppression.14,15 However, if HAART is discontinued, replication flares again within 2 weeks.16

Some exceptional individuals seem to control the virus after treatment interruption.17 The immune system also seems to control HIV infection successfully in rare long-term nonprogressors18,19 and in exposed, noninfected individuals who have anti-HIV CD8+ T lymphocytes.8,20 21 Because there is a clear role for the immune system in viral replication control, defects in antigen-presenting cells (APCs) may be crucial.

Among APCs, dendritic cells (DCs) are the only cells that can stimulate naive T lymphocytes.22 In peripheral blood, they are mostly immature and comprise 2 major populations. “Myeloid” DCs express CD11c and other myeloid-related surface molecules, including the granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) receptor. They are dependent on GM-CSF for growth and survival. When stimulated, they secrete IL-12, a key cytokine for the induction of cytotoxicity and TH1-type secretions by T lymphocytes. “Lymphoid” DCs do not express CD11c, but the IL-3 receptor, and are dependent on IL-3 for survival.23,24 Importantly, they are responsible for type I interferon (IFN) secretion in response to viral stimuli.25 26

DCs can be infected by HIV in vitro and in vivo, although with a low frequency,27 and mediate CD4+ T-cell transinfection.28 Because they are the only APCs that can stimulate naive T lymphocytes, they are required for vaccination and induction of primary immune responses at the onset of infection and immune responses against variant epitopes. DCs are also agents of innate immune responses to viruses, through type I IFN secretion25,26,29 and natural killer (NK) cell activation.30 Therefore, DC defects in HIV infection would decrease innate and adaptative immune responses against the virus.

Impairment of antigen presentation was found in HIV infection, particularly a defect in alloantigen presentation by Langerhans cells—DCs of the multistratified epithelia—from infected individuals compared with their noninfected, seronegative twins.31,32Using rare event analysis of flow cytometry data, we have found a decreased up-regulation in culture of CD83, which is related to DC maturation, in DCs from the spleens of HIV+patients.33 More importantly, we have also evidenced a marked decrease in the proportion of peripheral blood CD11c+ DCs in a group of chronically HIV-infected patients.34

In the present work, we investigated whether CD123+ DCs were also decreased in HIV infection. We studied both DC subpopulations during the primary infection, when therapeutic intervention appears to have the greatest impact on establishment of the balance between the virus and the immune system. In addition, we determined whether early initiation of HAART would affect DCs, by quantifying them longitudinally before treatment initiation and after 6 to 12 months of treatment.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patients and controls

Heparinated blood was collected from 13 patients with primary infection from the ANRS PRIMO cohort,4 approved by the local Comité Consultatif de Protection des Personnes dans la Recherche Biomédicale (Paris, France). Primary infection was diagnosed by an incomplete Western blot (WB) or by a positive p24 antigenemia with negative or weakly positive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or negative WB. Infection date was estimated as the date of symptom onset minus 15 days or date of incomplete WB minus 1 month. Patients were tested at their first visit, estimated 26 to 57 days after infection, and 6 to 12 months after institution of HAART, consisting of 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase (RT) inhibitors and one protease inhibitor or one nonnucleoside RT inhibitor (Table 1). Peripheral blood from 13 noninfected individuals, ages 31 to 53, was obtained from the Etablissement de Transfusion Sanguine of La Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, Paris, France, according to ethical guidelines. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were separated using flotation on a Ficoll-Paque density gradient and frozen in fetal calf serum (FCS; Dutscher, Brumath, France)-10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma, St Quentin Fallavier, France) before analysis. HIV plasma viral load was quantified using Roche Amplicor PCR kits (Roche Diagnostics, Meylan, France) with a lower limit of detection of 20 copies/mL.

Clinical data from patients with primary infection

| Patient . | Age, Sex . | Days after infection, before HAART . | Months after infection, after HAART . | Treatment* . | CD4 T cells/μl, before HAART . | CD4 T cells/μl, after HAART . | Plasma HIV RNA (log copies/mL), before HAART . | Plasma HIV RNA (log copies/mL), after HAART . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 43, Female | 57 | 12 | ZDV LAM SQV | 453 | 789 | 4.7 | 2.7 |

| 2 | 28, Male | 37 | 12 | d4T LAM NFV | 734 | 1085 | 4.7 | 1.0 |

| 3 | 24, Male | 41 | 6 | ZDV LAM NFV | 740 | 742 | 5.3 | 2.1 |

| 4 | 31, Male | 26 | 6 | ZDV LAM NFV | 451 | 361 | 6.3 | 3.6 |

| 5 | 34, Male | 38 | 6 | d4T ddI RTV HU | 684 | 655 | 6.5 | 1.0 |

| 6 | 34, Male | 35 | 6 | ZDV LAM NFV | 954 | 851 | 2.6 | 1.0 |

| 7 | 29, Male | 32 | 12 | ZDV LAM IDV† | 558 | 881 | 4.8 | 4.6 |

| 8 | 51, Male | 33 | 6 | ZDV LAM EFV | 594 | 1079 | 5.3 | 1.0 |

| 9 | 32, Male | 39 | 6 | ZDV LAM RTV | 371 | 1428 | 7.1 | 1.0 |

| 10 | 46, Male | 31 | 6 | LAM ABC RTV IDV | 529 | 487 | 5.9 | 2.4 |

| 11 | 28, Male | 31 | 6 | ZDV ddI EFV | 863 | 1496 | 4.3 | 1.8 |

| 12 | 34, Male | 28 | 6 | d4t ddI NFV RTV HU | 194 | 353 | 6.9 | 1.9 |

| 13 | 34, Male | 50 | 12 | ZDV LAM RTV SQV | 934 | 722 | 5.4 | 3.5 |

| Mean ± SD | 34 ± 8 | 37 ± 9 | 620 ± 230 | 840 ± 360 | 5.4 ± 1.2 | 2.1 ± 1.2 |

| Patient . | Age, Sex . | Days after infection, before HAART . | Months after infection, after HAART . | Treatment* . | CD4 T cells/μl, before HAART . | CD4 T cells/μl, after HAART . | Plasma HIV RNA (log copies/mL), before HAART . | Plasma HIV RNA (log copies/mL), after HAART . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 43, Female | 57 | 12 | ZDV LAM SQV | 453 | 789 | 4.7 | 2.7 |

| 2 | 28, Male | 37 | 12 | d4T LAM NFV | 734 | 1085 | 4.7 | 1.0 |

| 3 | 24, Male | 41 | 6 | ZDV LAM NFV | 740 | 742 | 5.3 | 2.1 |

| 4 | 31, Male | 26 | 6 | ZDV LAM NFV | 451 | 361 | 6.3 | 3.6 |

| 5 | 34, Male | 38 | 6 | d4T ddI RTV HU | 684 | 655 | 6.5 | 1.0 |

| 6 | 34, Male | 35 | 6 | ZDV LAM NFV | 954 | 851 | 2.6 | 1.0 |

| 7 | 29, Male | 32 | 12 | ZDV LAM IDV† | 558 | 881 | 4.8 | 4.6 |

| 8 | 51, Male | 33 | 6 | ZDV LAM EFV | 594 | 1079 | 5.3 | 1.0 |

| 9 | 32, Male | 39 | 6 | ZDV LAM RTV | 371 | 1428 | 7.1 | 1.0 |

| 10 | 46, Male | 31 | 6 | LAM ABC RTV IDV | 529 | 487 | 5.9 | 2.4 |

| 11 | 28, Male | 31 | 6 | ZDV ddI EFV | 863 | 1496 | 4.3 | 1.8 |

| 12 | 34, Male | 28 | 6 | d4t ddI NFV RTV HU | 194 | 353 | 6.9 | 1.9 |

| 13 | 34, Male | 50 | 12 | ZDV LAM RTV SQV | 934 | 722 | 5.4 | 3.5 |

| Mean ± SD | 34 ± 8 | 37 ± 9 | 620 ± 230 | 840 ± 360 | 5.4 ± 1.2 | 2.1 ± 1.2 |

Treatment abbreviations are as follows: ZDV indicates zidovudine; LAM, lamivudine; SQV, saquinavir; NFV, nelfinavir; RTV, ritonavir; HU, hydroxyurea; IDV, indinavir; EFV, efavirenz; ABC, abacavir.

Stopped after 3 months.

HAART indicates highly active antiretroviral therapy.

Flow cytometry

One million PBMCs in 50 μL were incubated simultaneously with monoclonal antibodies for 30 minutes in the dark at 4°C. To estimate CD11c and CD123 expression, we used a combination of phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated antibodies to either CD11c (S-HCl 3, diluted 1:20) or CD123 (9F5, diluted 1:20) with peridinin-chlorophyll protein (PerCP)–conjugated anti–human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DR (L243, diluted 1:10), and a cocktail of 6 fluorescein-isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated antibodies (lineage cocktail 1, diluted 1:10) comprising anti-CD3 (SK7), anti-CD14 (MϕP9), anti-CD16 (3G8), anti-CD19 (SJ25C1), anti-CD20 (L27) and anti-CD56 (NCAM 16-2) (Becton Dickinson, Le Pont de Claix, France).35 Cells were then washed twice in 2 mL phosphate buffered saline (PBS; Gibco, Paisley, Scotland) supplemented with 2% FCS and fixed in 300 μL PBS 1% para-formaldehyde (Sigma). Flow-cytometry analysis was performed using a FACScalibur and CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson). All data were collected using identical instrument settings. As previously described,33 34 we used a rare event analysis of DCs. One hundred thousand events corresponding to mononuclear cells by forward/side scatter characteristics were acquired (gate R1). Absolute numbers of DC subpopulations per milliliter of blood were calculated as follows, using hemocytometer data for lymphocytes and monocytes and flow cytometry data for windows: number of (monocytes+lymphocytes)/mL × (number of events in the population [ie, in R3 or R4, Figure 1]/number of PBMCs [ie, events in R1]).

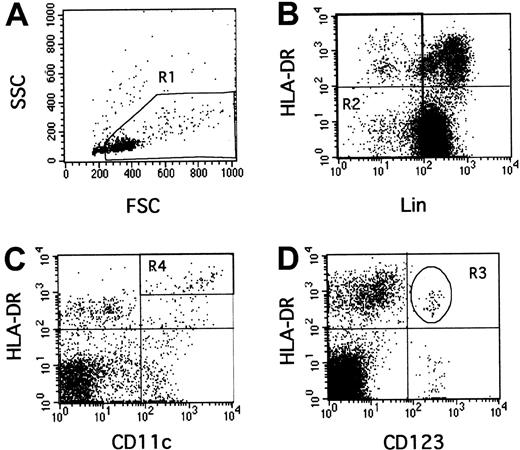

Rare event analysis of human CD123+ and CD11c+ DCs by flow cytometry.

PBMCs were selected in the R1 gate excluding debris and polynuclear cells (A). Lineage-negative cells were selected in the R2 gate (B). In this combined R1 and R2 gate, CD11c+, HLA-DR++(C, R4) or CD123+, HLA-DR+ (D, R3) events were quantified.

Rare event analysis of human CD123+ and CD11c+ DCs by flow cytometry.

PBMCs were selected in the R1 gate excluding debris and polynuclear cells (A). Lineage-negative cells were selected in the R2 gate (B). In this combined R1 and R2 gate, CD11c+, HLA-DR++(C, R4) or CD123+, HLA-DR+ (D, R3) events were quantified.

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons between groups were performed using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test and correlations were made by use of simple regression tests. P < .05 was considered significant. Statview 5 software was used (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA).

Type I interferon plasma level assay

IFN titrations were performed using a biologic assay.36 Plasma was diluted 2-fold in duplicate in 96-well microplates. Madin Darby bovine kidney (MDBK) cells, which are sensitive to type I but not type II IFNs, were added in 10% FCS minimum essential medium (MEM) (30 000/100 μL per well). Mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 18 hours then vesicular stomatitis virus was added (multiplicity of infection: 1). Cytopathic effect was scored under the microscope 24 hours later. Titration end points represent dilutions that gave destruction of 50% of the cells. A laboratory reference of human IFN-alpha, standardized with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Ga 023-902-530, was included with each titration. In addition, antiviral activity was further characterized by neutralization with IFN-alpha–specific antiserum.

Results

CD123+ and CD11c+ DC numbers are decreased during HIV primary infection

Thirteen HIV+ patients were studied 26 to 57 days after the estimated date of infection, then after 6 to 12 months of HAART (Table 1). They had on average 620 ± 230 CD4 T lymphocytes/μL (median 600, range, 194-954) and 5.4 ± 1.2 logs viral RNA copies/mL plasma (median 5.3, range 2.6-7.1). The numbers of CD123+ (lymphoid) and CD11c+ (myeloid) DCs were assessed by flow cytometry using rare event analysis33-35(Figure 1). The R1 gate containing PBMCs and excluding debris and polynuclear cells (Figure 1A) was combined with an R2 gate excluding cells strongly positive for other lineage-specific molecules (T and B lymphocytes, monocytes, natural killer [NK] cells, Figure 1B). Some weakly positive lineage cells were retained in gate R2, because they comprised intricated populations of myeloid DCs (HLA-DR++, CD14low, CD11c+) and of monocyte/macrophages (HLA-DR+, CD14low; 4-color labeling, data not shown). Therefore, the HLA-DR+, Lin− quadrant (Figure 1B) contained lymphoid DCs, myeloid DCs, and monocyte/macrophages mostly represented in the lower right corner of this quadrant but difficult to separate from the myeloid DCs in this plot. However, they could be separated after further labeling with CD11c, since myeloid DCs are HLA-DR++, CD11c+(Figure 1C, gate R4), whereas monocyte/macrophages are HLA-DR+, CD11c+ (Figure 1C, under gate R4). Lymphoid DCs were delineated as HLA-DR+, CD123+in gate R3 (Figure 1D); they expressed HLA-DR less strongly than myeloid DCs (4-color labeling, data not shown).

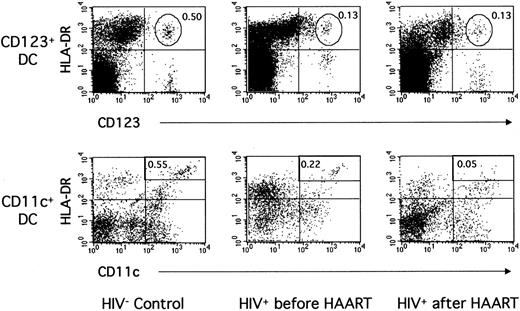

Figure 2 shows data from a representative control donor and a representative HIV+ patient. In the patient, a low proportion of CD123+ DCs (0.13% of PBMCs vs 0.50% in the control) and of CD11c+ DCs (0.22% vs 0.55%) was found before treatment initiation. These proportions were typical of the whole patient group (Table 2, Figure 3). Indeed, the mean number of CD123+ DCs was greatly decreased in the patients compared with 13 healthy donors (4320/mL ± 2510/mL vs 12 300/mL ± 6500/mL blood, P = .0002). The numbers of CD11c+ DCs were also decreased in the patients (5590/mL ± 3050/mL blood) compared with the controls (16 900/mL ± 14 300/mL blood,P = .001). In fact, in 8 of 13 patients, the CD11c+ DC subpopulation became difficult to distinguish from other mononuclear, lineage-weak or lineage-negative cells expressing HLA-DR and CD11c (Figure 2). No correlation was found between DC numbers and CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts or viral load before treatment initiation. Therefore, the numbers of blood CD123+ as well as CD11c+ DCs were clearly decreased in these patients during primary infection.

Blood CD123+ and CD11c+ DCs in one noninfected donor and in one patient during primary infection before and after 12 months of HAART.

PBMCs from one HIV-noninfected control donor and one HIV-infected patient (patient no. 2) before and after HAART were labeled as in Figure 1.

Blood CD123+ and CD11c+ DCs in one noninfected donor and in one patient during primary infection before and after 12 months of HAART.

PBMCs from one HIV-noninfected control donor and one HIV-infected patient (patient no. 2) before and after HAART were labeled as in Figure 1.

Dendritic cell populations during HIV primary infection

| Patient . | CD123+ DC/mL blood (% vs PBMCs) . | CD11c+ DC/mL blood (% vs PBMCs) . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| before HAART . | after HAART . | before HAART . | after HAART . | |||||

| 1 | 5 270 | 0.25 | 6 060 | 0.29 | 7 370 | 0.35 | 2 920 | 0.14 |

| 2 | 4 150 | 0.13 | 4 000 | 0.13 | 7 020 | 0.22 | 1 540 | 0.05 |

| 3 | 7 550 | 0.19 | 4 560 | 0.16 | 5 960 | 0.15 | 2 850 | 0.10 |

| 4 | 1 470 | 0.06 | 1 090 | 0.05 | 5 860 | 0.24 | 870 | 0.04 |

| 5 | 8 950 | 0.20 | 1 630 | 0.12 | 13 000 | 0.29 | 2 720 | 0.20 |

| 6 | 5 320 | 0.18 | 1 520 | 0.06 | 4 140 | 0.14 | 760 | 0.03 |

| 7 | 4 200 | 0.19 | 990 | 0.04 | 6 400 | 0.29 | 3 230 | 0.13 |

| 8 | 1 980 | 0.08 | 2 790 | 0.07 | 4 000 | 0.18 | 15 080 | 0.27 |

| 9 | 2 300 | 0.13 | 13 700 | 0.29 | 4 600 | 0.26 | 12 000 | 0.33 |

| 10 | 5 500 | 0.27 | 3 100 | 0.13 | 4 900 | 0.51 | 10 400 | 0.22 |

| 11 | 6 240 | 0.24 | 11 200 | 0.32 | 1 300 | 0.05 | 5 950 | 0.17 |

| 12 | 150 | 0.01 | 5 730 | 0.39 | 760 | 0.05 | 7 350 | 0.50 |

| 13 | 3 080 | 0.08 | 1 410 | 0.03 | 7 310 | 0.19 | 6 580 | 0.14 |

| Mean ± SD | 4 320 ± 2 510 | 0.15 ± 0.08 | 4 450 ± 3 970 | 0.16 ± 0.12 | 5 590 ± 3 050 | 0.22 ± 0.12 | 5 560 ± 4 550 | 0.18 ± 0.13 |

| P vs controls | P = .0002 | P < .0001 | P = .0009 | P = .0009 | P = .001 | P = .003 | P = .003 | P = .0007 |

| HIV− controls (n = 13) | 12 300 ± 6500 | 0.43 ± 0.19 | 16 900 ± 14 300 | 0.60 ± 0.46 | ||||

| Patient . | CD123+ DC/mL blood (% vs PBMCs) . | CD11c+ DC/mL blood (% vs PBMCs) . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| before HAART . | after HAART . | before HAART . | after HAART . | |||||

| 1 | 5 270 | 0.25 | 6 060 | 0.29 | 7 370 | 0.35 | 2 920 | 0.14 |

| 2 | 4 150 | 0.13 | 4 000 | 0.13 | 7 020 | 0.22 | 1 540 | 0.05 |

| 3 | 7 550 | 0.19 | 4 560 | 0.16 | 5 960 | 0.15 | 2 850 | 0.10 |

| 4 | 1 470 | 0.06 | 1 090 | 0.05 | 5 860 | 0.24 | 870 | 0.04 |

| 5 | 8 950 | 0.20 | 1 630 | 0.12 | 13 000 | 0.29 | 2 720 | 0.20 |

| 6 | 5 320 | 0.18 | 1 520 | 0.06 | 4 140 | 0.14 | 760 | 0.03 |

| 7 | 4 200 | 0.19 | 990 | 0.04 | 6 400 | 0.29 | 3 230 | 0.13 |

| 8 | 1 980 | 0.08 | 2 790 | 0.07 | 4 000 | 0.18 | 15 080 | 0.27 |

| 9 | 2 300 | 0.13 | 13 700 | 0.29 | 4 600 | 0.26 | 12 000 | 0.33 |

| 10 | 5 500 | 0.27 | 3 100 | 0.13 | 4 900 | 0.51 | 10 400 | 0.22 |

| 11 | 6 240 | 0.24 | 11 200 | 0.32 | 1 300 | 0.05 | 5 950 | 0.17 |

| 12 | 150 | 0.01 | 5 730 | 0.39 | 760 | 0.05 | 7 350 | 0.50 |

| 13 | 3 080 | 0.08 | 1 410 | 0.03 | 7 310 | 0.19 | 6 580 | 0.14 |

| Mean ± SD | 4 320 ± 2 510 | 0.15 ± 0.08 | 4 450 ± 3 970 | 0.16 ± 0.12 | 5 590 ± 3 050 | 0.22 ± 0.12 | 5 560 ± 4 550 | 0.18 ± 0.13 |

| P vs controls | P = .0002 | P < .0001 | P = .0009 | P = .0009 | P = .001 | P = .003 | P = .003 | P = .0007 |

| HIV− controls (n = 13) | 12 300 ± 6500 | 0.43 ± 0.19 | 16 900 ± 14 300 | 0.60 ± 0.46 | ||||

PBMCs indicates peripheral blood mononuclear cells; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy.

Blood CD123+ and CD11c+ DC absolute numbers in primary HIV infection before and after 6 to 12 months of HAART.

PBMCs from 13 HIV+ patients and 13 HIV−controls were analyzed by flow cytometry as in Figure 1.

Blood CD123+ and CD11c+ DC absolute numbers in primary HIV infection before and after 6 to 12 months of HAART.

PBMCs from 13 HIV+ patients and 13 HIV−controls were analyzed by flow cytometry as in Figure 1.

CD123+ blood DC number recovery under HAART correlates with CD4 count increase and viral load decrease

HAART, administered for 6 to 12 months, induced at least a 2-log decrease in plasma viral load in 11 of 13 patients, reaching undetectable levels (1.0) in 5 patients, with a mean of 2.1 log copies/mL ± 1.2 log copies/mL plasma (median 1.9, range 1.0-4.6; Table 1). Treatment also induced an increase of the CD4 T-lymphocyte counts in 8 of 13 patients (average CD4 cell count after therapy: 840/μL ± 360/μL, median 790, range 353-1496). Surprisingly, the mean number of CD123+ DCs remained as low as before treatment (4450/mL ± 3970/mL blood, median 3100,P = .0009 compared with healthy donors;P = .59, ie, nonsignificant compared with before treatment; Table 2, Figure 3). Eight patients had decreased numbers, and 5 patients had higher numbers than before treatment initiation. Among these, 2 (no. 9 and no. 11) recovered numbers of CD123+ DCs close to the average number observed in noninfected controls. Patient no. 9 had the highest plasma viral load of the group before treatment (7.1 log copies/mL) and a relatively low CD4 lymphocyte count (371/μL), but after HAART, the patient's viral load became undetectable and his CD4 cell count normal (1428/μL). Moreover, this patient had a strikingly atypical clinical story: after HAART interruption at month 12, his viral load remained undetectable 6 months later. The viral load of patient no. 11 remained detectable, but his CD4 cell count was the highest of all patients after treatment (1496/μL). A strong correlation was found between CD123+DC increase and CD4 T-cell count increase (P = .0009) (Figure 4A) and plasma viral load decrease (P = .009) (Figure 4B) after treatment.

Correlation between lymphoid DC numbers and CD4 T-cell count increase and plasma viral load decrease after HAART.

Blood CD123+ and CD11c+ DC number difference after HAART and (A, C) CD4 T-cell count difference after HAART and (B, D) plasma viral load difference after HAART. Lines represent regressions; P values, regression probabilities.

Correlation between lymphoid DC numbers and CD4 T-cell count increase and plasma viral load decrease after HAART.

Blood CD123+ and CD11c+ DC number difference after HAART and (A, C) CD4 T-cell count difference after HAART and (B, D) plasma viral load difference after HAART. Lines represent regressions; P values, regression probabilities.

The mean number of CD11c+ DCs was not restored by treatment either (5560/mL ± 4550/mL blood, median 3230; Table 2, Figure 3). It was lower than in healthy donors (P = .003), and not significantly different from before treatment (P = .64). The CD11c+ DC subpopulation became difficult to distinguish from other mononuclear, lineage-negative HLA-DRlow, CD11c+ populations in all but one patient. Five of 13 patients had higher CD11c+ DC numbers under treatment than before, but no correlation was found between this increase and viral loads or CD4 cell counts (Figure 4C, D; Table 2: compare patient no. 8 and patient no. 9 with patient no. 10).

Therefore, HAART did not restore the average numbers of the 2 DC subpopulations, but some patients had higher numbers than before treatment initiation. Whereas CD11c+ DC number recovery did not correlate with viral load or CD4 cell count changes, CD123+ DC number recovery was strongly correlated with good virologic and immunologic parameters, and in one patient, restoration of normal CD123+ DC numbers was found together with a remarkable control of infection.

Type I interferon plasma levels

To help interpret the functional consequences of the decreased blood CD123+ DC numbers, type I IFN plasma levels were measured. All were undetectable (< 2 international units (IU)/mL), except for patient no. 12 at initiation of the study (8 IU/mL). These numbers are normal compared with healthy blood donors (< 2 IU/mL), and low compared with levels of more than 100 IU/mL found in birth-infected newborns from HIV-seropositive mothers (A. Krivine MD, St Vincent de Paul Hospital, P. Lebon, personal written communication, 1992) and 200 to 400 IU/mL in the first 10 days of experimental simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection in macaques.37

Discussion

The data presented here show for the first time a profound reduction of blood CD123+ DC numbers in primary HIV infection, and show at this stage of infection the blood CD11c+ DC number decrease that we had previously found in chronically HIV-infected patients.34 These are the first DC population alterations described in an infectious disease. These defects were found here as early as 26 to 57 days after the estimated date of infection, indicating that they were probably related to HIV itself rather than to the chronic activation of the immune system found in later stages of infection. Most interestingly, they were restored by antiretroviral treatment in only a few patients, and a strong correlation was found between CD123+ DC number recovery and good virologic and immunologic parameters. The striking clinical history of one of the patients, whose viral load remained undetectable as long as 6 months after HAART interruption, as already seen in other exceptional cases,17 coincides with a remarkable restoration of CD123+ (and CD11c+) DCs to normal numbers. Therefore, CD123+ DC number recovery under HAART could represent a predictor of viral control. In addition, the implications of this quantitative APC defect might be clues to design new strategies to enhance viral control.

Potential causes of blood DC number reduction may be either central or peripheral. In the periphery, DCs may have homed to lymphoid organs and may no longer be in the blood. Comparative data from blood and lymphoid organs are not available during primary infection. An elevated frequency of CD1a+ DCs was found in HIV+ patient tonsils38; these cells may originate either from mucosal Langerhans cells or from blood DC precursors.39 Alternately and not exclusively, DCs may be destroyed in the periphery, either by the virus itself, by CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes, by a lack of survival factors, or by other mechanisms. Conversely, the causes of DC reduction may be central, with a decreased production of DCs from bone marrow CD34+ or blood monocyte precursors, the latter being suggested by the aspect of the flow cytometry data (Figure 2). In vitro differentiation of CD11c+ DCs from HIV+patient monocytes seems normal,40,41 but indirect interactions may occur in the relevant microenvironment in vivo,and in vitro infection data using different DCs and precursors are needed. CD11c+ DCs with a lower HLA-DR expression—and a lower antigen presentation ability—may be present, but undistinguishable from other myeloid cells with low CD14 expression. DC production, differentiation, and survival are supported by T lymphocytes through several interleukins (including IFN-gamma, GM-CSF, and IL-4) and surface molecules (including CD40L, 4-1BB, OX 40, and TRANCE) (reviewed in Banchereau et al22). The T-cell defect, which is a main event in HIV infection,2-6 11 may induce the DC number reduction found here.

The potential consequences of the decreased numbers of DC populations in HIV infection are related to some of their functions: cytokine production (type I IFN, IL-12) and antigen presentation to naive T lymphocytes.

CD123+ DCs are the natural interferon-producing cells.25,26 During chronic HIV infection, a defective type I IFN in vitro response of DCs to viral stimuli was shown.29 During experimental primary SIV infection in macaques, the peak of IFN-alpha secretion preceded that of antigenemia and levels became undetectable between 25 and 50 days after infection.37 In the patients studied here, all but one had undetectable levels at initiation of the study as well as 6 or 12 months later. The patient with a low but detectable level of plasma IFN was one of the earliest patients in the study (28 days, plasma drawn at the end of symptoms and 4 days after indeterminate WB) and had the second highest viral load (6.3 logs). The kinetics of type I IFN secretion still need to be studied in HIV+ patients, but if they parallel macaque studies, the peak may occur earlier than in the present study. Then reduction of CD123+ DC numbers might decrease this innate immune response, which was shown to be able to decrease HIV replication (reviewed in Khatissian et al37), to promote CD123+ DC survival, to increase TH1-type responses,24 and, together with GM-CSF, to mediate in vitro differentiation of DCs with strong HIV antigen presentation capacities in the severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mouse model.42

CD11c+ and CD123+ DCs secrete IL-12.23,24 Their reduced numbers may participate in the defective IL-12 responsiveness to inflammatory and viral stimuli that was found in PBMCs from HIV+ patients.43-46This might contribute to the low IL-2 secretion by CD4+ T cells, because IL-12 was shown to restore in vitro IL-2 production from chronic HIV+ patient cells in response to HIV antigens.43 47

A consequence of low DC numbers may be a decreased ability to stimulate naive HIV-specific T lymphocytes. Indeed, Langerhans cells from HIV+ patients were deficient for allostimulation, hence naive T-cell stimulation, but not memory CD8+ T-cell activation.32,40 This would add to the T helper cell defect to explain the low T-cell responses during HIV primary infection. In addition, if DCs are not restored under HAART, naive T cells may not respond to viral antigens when HAART is interrupted. This may also hamper responses to therapeutic vaccination protocols currently undertaken under HAART to restore strong memory T-cell responses to the virus. It might be necessary to restore DC numbers before vaccination. This might be achieved, like CD4+T-cell restoration, by long-term viral suppression,14 15and might be improved by immune therapy.

In combination with vaccination protocols under HAART, it may be necessary either to supplement DCs by IFN-alpha42 or IL-12 treatment if toxicity potential was overcome.44,47Alternatively, it may be necessary to try and restore DC numbers using interleukins or molecules triggering DC survival, differentiation, and activation, like FLT3 ligand, GM-CSF, CD40 ligand trimers, IFN-gamma,43,46,48 49 alone or in combination. This might restart the positive feedback loop between DCs and T cells, and hopefully help stimulate stronger HIV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes able to control HIV infection after HAART interruption. A larger proportion of infected individuals would then join the exceptional exposed, noninfected individuals or the long-term nonprogressors in a successful immune control of HIV replication.

We thank all the participating patients from the PRIMO cohort and their clinicians. We thank Sophie Maillet, Jean-Christophe Deschemin, Marion Dupuis, Alejandra Urrutia, and Joël Vega for skillful technical help; Muriel Andrieu and Cecile Cau for teaching FACS use; Sylvie Jacod-Le Borgne for help with statistical analysis; Michèle Villemur, the Etablissement de Transfusion Sanguine, and the donors for control blood; Claire Chougnet and Muriel Moser for helpful discussion and for carefully reading the manuscript; and Jean-Gérard Guillet and Jean-François Delfraissy for support.

Supported by the Agence Nationale de Recherche sur le SIDA (ANRS), Ensemble Contre le SIDA (Sidaction), and the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (J.P.).

J.P. and S.K. contributed equally to this work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Anne Hosmalin, INSERM Unité 445, Institut Cochin de Génétique Moléculaire, 27 rue du Faubourg Saint Jacques, 75014 Paris, France; e-mail: hosmalin@cochin.inserm.fr.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal