Abstract

Platelet Endothelial Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 (PECAM-1, CD31) is a 130-kd member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily that is expressed on the surface of platelets, endothelial cells, myeloid cells, and certain lymphocyte subsets. PECAM-1 has recently been shown to contain functional immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs (ITIMs) within its cytoplasmic domain, and co-ligation of PECAM-1 with the T-cell antigen receptor (TCR) results in tyrosine phosphorylation of PECAM-1, recruitment of Src homology 2 domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase-2 (SHP-2), and attenuation of TCR-mediated cellular signaling. To determine the molecular basis of PECAM-1 inhibitory signaling in lymphocytes, the study sought to (1) establish the importance of the PECAM-1 ITIMs for its inhibitory activity, (2) determine the relative importance of SHP-2 versus SHP-1 in mediating the inhibitory effect of PECAM-1, and (3) identify the protein tyrosine kinases required for PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation in T cells. Co-ligation of wild-type PECAM-1 with the B-cell antigen receptor expressed on chicken DT40 B cells resulted in a marked reduction of calcium mobilization—similar to previous observations in T cells. In contrast, co-ligation of an ITIM-less form of PECAM-1 had no inhibitory effect. Furthermore, wild-type PECAM-1 was unable to attenuate calcium mobilization in SHP-2–deficient DT40 variants despite abundant levels of SHP-1 in these cells. Finally, PECAM-1 failed to become tyrosine phosphorylated in p56lck-deficient Jurkat T cells. Together, these data provide important insights into the molecular requirements for PECAM-1 regulation of antigen receptor signaling.

Introduction

The strength of the signal transduced by the T-cell antigen receptor (TCR) is influenced by the cellular context in which antigen is recognized (reviewed in1). One of the variables that provides context for antigen recognition is the expression of inhibitory receptors on T-cell targets. Inhibitory receptors possess, within their cytoplasmic domains, an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM), which is characterized by the presence of a tyrosine residue surrounded by a hydrophobic residue at position −2 and a leucine or valine residue at the +3 position (reviewed in2). For inhibitory receptors containing one such motif, protein tyrosine kinase (PTK)-dependent phosphorylation of the tyrosine residue enables recruitment of a Src-homology 2 (SH) domain-containing inositol phosphatase (SHIP). Inhibitory receptors that contain 2 such motifs that are separated from one another by a spacer of 16 to 30 amino acid residues support the binding of SH2-domain containing protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs), such as SHP-1 and SHP-2. In either case, recruited phosphatases interfere with PTK-dependent signaling (reviewed in2). Although the involvement of intracellular PTKs in TCR signal transduction has been well characterized, the roles and identities of the PTPs that regulate TCR signaling, as well as the inhibitory receptors to which they bind, remain to be established.

It has been proposed that Platelet Endothelial Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 (PECAM-1, CD31) may regulate signals transduced by antigen receptors (reviewed in3). PECAM-1 possesses a dual ITIM that, on tyrosine phosphorylation, supports the binding of SHP-2.4,5 In T cells, PECAM-1 becomes tyrosine phosphorylated and binds SHP-2 in response to engagement of the (TCR),6 and heightened levels of PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation and SHP-2 binding are observed in response to cross-linking of PECAM-1 alone or together with the TCR.7 In previous studies, we have used PECAM-1–expressing T-cell lines to show that PECAM-1 functions as an inhibitory receptor, in that co-ligation of PECAM-1 with the TCR results in attenuation of TCR-induced release of calcium from intracellular stores.7These studies did not, however, address whether either tyrosine phosphorylation of the PECAM-1 ITIMs or subsequent binding of SHP-2 were required for the inhibitory function of PECAM-1. The recent finding that mutant forms of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4), which fail to become tyrosine phosphorylated and bind SHP-2, continue to inhibit T-cell activation8,9 make this possibility an important consideration. In addition, several studies6,10-12 have reported that, in addition to SHP-2, the related PTP, SHP-1, can bind to the tyrosine-phosphorylated PECAM-1 ITIMs, albeit with lower affinity. Pumphrey et al12 have reported that SHP-2, SHP-1, and SHIP bind to the tyrosine-phosphorylated PECAM-1 ITIMs. Although each of these phosphatases may be capable of binding to the PECAM-1 ITIMs, their relative ability to support the inhibitory function of PECAM-1 has not yet been addressed.

PECAM-1 does not possess intrinsic kinase activity, and the range of the PTKs responsible for tyrosine phosphorylating the ITIMs within the cytoplasmic domain of PECAM-1 is not known. TCR-mediated signal transduction involves the activity of members of the Src, Syk, and Tec families of PTKs (reviewed in1,13). Several in vitro studies have shown that exogenous c-Src can phosphorylate glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-fusion proteins containing the PECAM-1 cytoplasmic domain5,14,15 or native PECAM-1 isolated from bovine aortic endothelial cells.15 In addition, PECAM-1 has been shown to become tyrosine phosphorylated in COS-1 cells that have been transiently co-transfected with pp60c-Src, p56lck, p59fyn, and p53lyn.10 The conclusion that Src family PTKs are involved in PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation is supported by the recent observation that PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation is reduced or abolished on exposure of stimulated platelets to the Src family PTK inhibitor, PP2.16 Among the Src family PTKs present in T cells, p56lck plays the best-documented role in TCR-mediated signal transduction in mature T lymphocytes.1 Whether p56lck functions in PECAM-1 signaling, however, is not yet known.

In the present investigation, we sought to determine whether an ITIM-less form of PECAM-1 expressed in the DT40 chicken B-cell line might be able to attenuate calcium mobilization and whether protein phosphatases other than SHP-2 might be able to functionally complement the inhibitory activity of a PECAM-1/SHP-2 signaling complex. We also investigated the importance of p56lck in PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation in T lymphocytes. Our results suggest that the molecular requirements for the inhibitory function of PECAM-1 include intact ITIMs, SHP-2, and, in T cells, the Src family PTK, p56lck.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and cell culture

The acute T-cell leukemia line, Jurkat E6-1,17 and the p56lck-deficient mutant derivative of Jurkat E6-1, JCaM1.6,18 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). JCaM1.6 transfectants that were stably expressing p56lck19 were a generous gift of Dr David Straus (University of Chicago). The chicken B-cell line, DT40, and the SHP-2–negative variant of DT40 were obtained from Riken Cell Bank (Ibaraki, Japan). T-cell lines were maintained in log phase growth at a density of 1 to 4 × 105/mL, and B-cell lines were maintained at a density of 0.5 to 1.5 × 106/mL in a humidified, 37°C, 5% CO2/95% air atmosphere. Jurkat cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD) containing 2 mM L-glutamine (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Life Technologies) 10 IU/mL heparin (Pharmacia/Upjohn, Kalamazoo, MI), 25 mM HEPES (Life Technologies), 50 μg/mL gentamicin (Elkins-Sinn, Cherry Hill, NC), 100 U/mL penicillin (Life Technologies), and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Life Technologies), containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Life Technologies). The p56lck-reconstituted JCaM1.6 cells were maintained in the presence of G418 (1 mg/mL) and hygromycin (250 μg/mL) (both from Life Technologies). DT40 B-cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 4 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 15% FBS, and 1.5% chicken serum (Life Technologies).

Generation and characterization of PECAM-1 transfectants

Methods for construction of pcDNA3.0 plasmid vectors containing wild-type20 and ITIM-less21 forms of PECAM-1 have been previously described. To generate transfectants, wild-type or SHP-2–deficient DT40 cells (5 × 106) were resuspended in 0.4 mL of serum-free RPMI 1640 medium containing 30 μg of plasmid DNA. Cells were electroporated at 250 V and 950 μF capacitance, using a gene pulser (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Cells were cultured for 48 hours in 10 mL of serum-containing RPMI 1640 medium before adding G418 (2 mg/mL; Life Technologies). G418-resistant stable transfectants, which represent a heterogeneous population of PECAM-1–transfected cells, were expanded and analyzed by flow cytometry for cell surface expression of PECAM-1.

Antibodies

To stimulate wild-type and mutant Jurkat T cells, the human CD3ε-specific antibody (Ab), UCHT1 (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), containing no azide and low endotoxin, was used. Wild-type and mutant DT40 B cells were stimulated with mouse anti-chicken B-cell antigen receptor (BCR), clone M-1 (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL). An F(ab′)2 fragment of the murine anti-human PECAM mAb, PECAM-1.3, used for cross-linking experiments, was prepared by using an Immunopure IgG1 F(ab′)2 Preparation Kit purchased from Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, IL). Azide-free F(ab′)2 goat antimouse (GAM) immunoglobulin G (IgG) was purchased from Accurate Chemical and Scientific (Westbury, NY) or ICN (Aurora, OH). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated GAM used in the flow cytometric analyses was purchased from Pharmingen.

PTK expression in T cells was evaluated by Western analysis, using mouse monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) specific for c-Src and p56lck from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and p59fyn from Transduction Laboratories (San Diego, CA). SHP-2 was detected by using a rabbit polyclonal SHP-2–specific Ab purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated GAM and goat antirabbit (GAR) IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) were used as secondary reagents for detection of bound mouse mAb and rabbit polyclonal Ab, respectively. Methods for induction and assessment of PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation have been previously described.7

Calcium mobilization assays

All procedures for measurement of intracellular calcium concentrations by fluorescence spectrofluorometry were performed in the dark. DT40 cells (5 × 106/mL) were incubated for 45 minutes at 37°C with 3 μM Fura-2AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) in calcium mobilization assay (CMA) buffer (PBS containing 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.2], 5 mM glucose, 0.025% bovine serum albumin, and 1 mM CaCl2). Cells were then adjusted to a final concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL with the addition of CMA buffer and were incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes in the presence of Abs at the indicated final concentrations. Preliminary dose response studies were performed to identify a dose of mAb directed against the chicken BCR (100 ng/mL) that induced a measurable but suboptimal increase in the intracellular calcium concentration only when cross-linked with F(ab′)2 fragments of GAM as measured by a change in the fluorescent properties of Fura-2AM (data not shown). To remove unbound Abs, cells were washed 3 times at room temperature with 4 mL of CMA buffer. Cell suspensions (2 mL) were transferred to a cuvette equipped with a magnetic stir bar and placed in a sample chamber, maintained at 37°C, of an SLM 8100 spectrofluorometer (SLM-Aminco, Urbana, IL). To cross-link surface-bound Abs, GAM F(ab′)2 was added at a final concentration of 50 μg/mL, which was determined in preliminary experiments to be super-optimal. Intracellular calcium concentration was assessed by measuring the intensity of light emitted at 510 nm on excitation at 340 and 380 nm every 3 seconds for 1 to 2 minutes. Results are presented as the ratio of the intensity of 510 nm light on excitation at 340, relative to 380, nm as a function of time.

Results

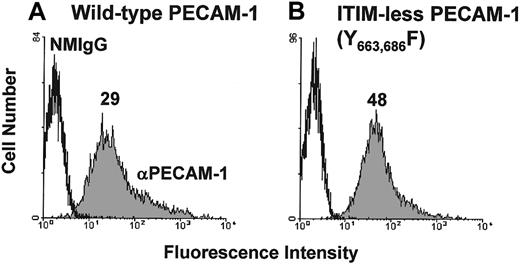

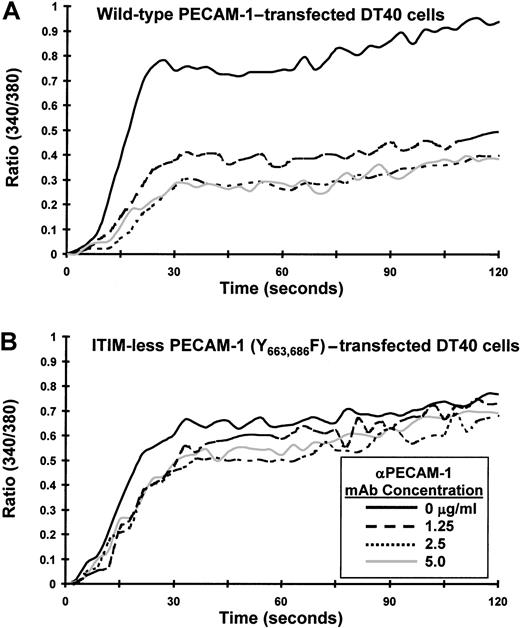

Previous studies have shown that PECAM-1 becomes tyrosine phosphorylated, binds SHP-2, and attenuates release of calcium from intracellular stores on its co-ligation with the TCR. The goal of the present investigation was to characterize the molecular requirements for the observed inhibitory activity of PECAM-1. We first sought to determine whether the inhibitory activity of PECAM-1 depends on tyrosine residues found within its cytoplasmic ITIMs. Studies in other cell systems have shown that PECAM-1 becomes tyrosine phosphorylated on residues 663 and 686,21 and sequences around these tyrosine residues conform to an ITIM (reviewed in3). To test the importance of these 2 tyrosines for the inhibitory function of PECAM-1, we made use of an ITIM-less mutant construct in which the tyrosine residues at positions 663 and 686 of the PECAM-1 cytoplasmic domain were substituted with phenylalanine residues.21Because the Jurkat T-cell line that we have used in previous studies constitutively expresses PECAM-1, we expressed PECAM-1 constructs in chicken DT40 B cells,22which are PECAM-1 negative (data not shown). As shown in Figure 1, wild-type and ITIM-less forms of PECAM-1 were expressed at similar levels on the surface of transfected DT40 cells. To determine whether the tyrosine residues within the PECAM-1 ITIMs were required to modulate antigen receptor-initiated signal transduction, we co-ligated wild-type or ITIM-less PECAM-1 with the BCR and measured the degree of calcium mobilization in Fura-2AM–loaded DT40 transfectants. As shown in Figure 2, cross-linking the BCR alone induced a rapid rise in intracellular calcium in B cells expressing either wild-type (Figure 2A) or ITIM-less (Figure 2B) forms of PECAM-1. Similar to what has been observed for the T-cell antigen receptor,7 co-ligation of wild-type PECAM-1 with the BCR resulted in dose-dependent attenuation of calcium mobilization (Figure 2A), whereas ITIM-less PECAM-1 was unable to attenuate calcium mobilization at any concentration of anti-PECAM-1 Ab tested (Figure 2B). From these results, we conclude that the ability of PECAM-1 to interfere with calcium mobilization induced by antigen receptor cross-linking is dependent on the presence of intact ITIMs.

Expression of wild-type and ITIM-less PECAM-1 on the surface of B-cell transfectants.

DT40 B cells were transfected with (A) wild-type human PECAM-1 or (B) an ITIM-less human PECAM-1 variant, in which the tyrosine residues at positions 663 and 686 were replaced by phenylalanine. Cells were pretreated with normal mouse IgG1 (NMIgG) or with PECAM-1.3, a murine mAb specific for human PECAM-1 (αPECAM-1). Antibody-pretreated cells were then stained with FITC-conjugated GAM IgG and analyzed by flow cytometry. Transfectants chosen for analysis expressed equivalent levels of cell surface PECAM-1.

Expression of wild-type and ITIM-less PECAM-1 on the surface of B-cell transfectants.

DT40 B cells were transfected with (A) wild-type human PECAM-1 or (B) an ITIM-less human PECAM-1 variant, in which the tyrosine residues at positions 663 and 686 were replaced by phenylalanine. Cells were pretreated with normal mouse IgG1 (NMIgG) or with PECAM-1.3, a murine mAb specific for human PECAM-1 (αPECAM-1). Antibody-pretreated cells were then stained with FITC-conjugated GAM IgG and analyzed by flow cytometry. Transfectants chosen for analysis expressed equivalent levels of cell surface PECAM-1.

The PECAM-1 ITIMs are required for attenuation of calcium mobilization in transfected B cells.

DT40 cells transfected with (A) wild-type PECAM-1 or (B) an ITIM-less form of PECAM-1, in which the tyrosine residues at positions 663 and 686 were changed to phenylalanine, were loaded with Fura-2AM and preincubated for 10 minutes at room temperature with murine antichicken BCR together with the indicated concentration of F(ab′)2 fragments of PECAM-1.3 Ab (αPECAM-1 mAb). Cells were washed free of unbound Ab and then added to the warmed (37°C) chamber of an SLM 8100 spectrofluorometer. Calcium mobilization was induced by cross-linking of surface-bound Abs on addition of F(ab′)2 fragments of GAM mouse IgG. The intracellular calcium concentration was assessed every 3 seconds over a period of 120 seconds. Note that co-ligation of the ITIM-less form of PECAM-1 with the BCR fails to attenuate calcium mobilization in DT40 cells.

The PECAM-1 ITIMs are required for attenuation of calcium mobilization in transfected B cells.

DT40 cells transfected with (A) wild-type PECAM-1 or (B) an ITIM-less form of PECAM-1, in which the tyrosine residues at positions 663 and 686 were changed to phenylalanine, were loaded with Fura-2AM and preincubated for 10 minutes at room temperature with murine antichicken BCR together with the indicated concentration of F(ab′)2 fragments of PECAM-1.3 Ab (αPECAM-1 mAb). Cells were washed free of unbound Ab and then added to the warmed (37°C) chamber of an SLM 8100 spectrofluorometer. Calcium mobilization was induced by cross-linking of surface-bound Abs on addition of F(ab′)2 fragments of GAM mouse IgG. The intracellular calcium concentration was assessed every 3 seconds over a period of 120 seconds. Note that co-ligation of the ITIM-less form of PECAM-1 with the BCR fails to attenuate calcium mobilization in DT40 cells.

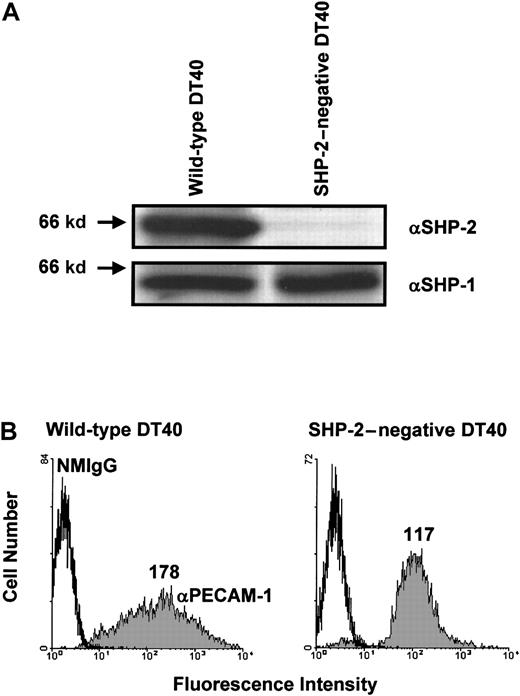

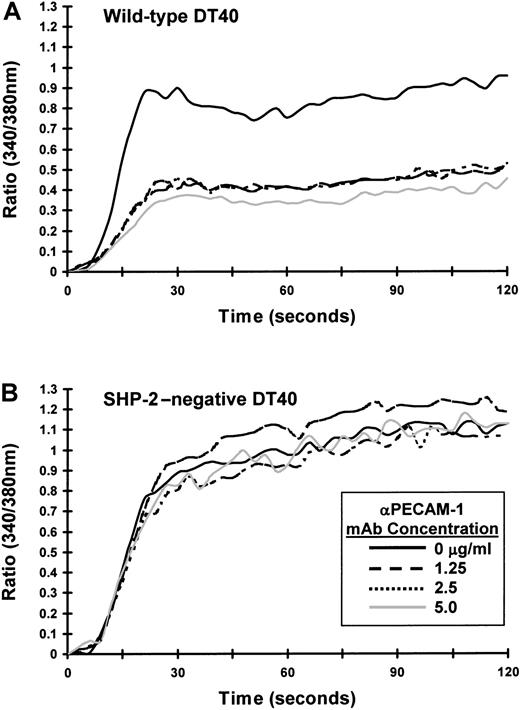

Next, we sought to determine whether SHP-2 is required for the inhibitory activity of PECAM-1. Although SHP-2 is the major phosphatase associated with tyrosine-phosphorylated PECAM-1,4-7 Hua et al11 have reported that phosphopeptides containing the PECAM-1 ITIM tyrosine residues or intact tyrosine-phosphorylated PECAM-1 can precipitate both SHP-1 and SHP-2. In addition, Pumphrey et al12 have reported that GST-fusion proteins containing the SH2 domains of SHP-1, SHP-2, or SHIP can interact with tyrosine-phosphorylated PECAM-1. To determine whether phosphatases other than SHP-2 can form a functional complex with PECAM-1 capable of mediating its inhibitory activity, we made use of an SHP-2–deficient variant of DT40 cells.23 As shown in Figure 3A, wild-type DT40 cells express both SHP-2 and SHP-1, whereas SHP-2–negative DT40 cells contain normal levels of SHP-1 but no SHP-2. Transfection of wild-type PECAM-1 resulted in similar cell surface expression in both wild-type and SHP-2–negative DT40 cells (Figure 3B), although the range of PECAM-1 expression in wild-type DT40 cells (left panel) was broader than that observed in SHP-2–negative cells (right panel). As shown in Figure 4A, co-ligation of PECAM-1 with the BCR in SHP-2–positive, wild-type DT40 transfectants resulted in a dose-dependent attenuation of calcium mobilization. In contrast, PECAM-1 was unable to attenuate calcium mobilization at any concentration of anti-PECAM-1 Ab tested in SHP-2–deficient DT40 cells (Figure4B), despite abundant levels of the related PTP, SHP-1 (Figure 3A). Failure of PECAM-1 to inhibit BCR-induced calcium mobilization in SHP-2–deficient DT40 cells is unlikely to be attributable to minor differences in PECAM-1 expression between these 2 cell lines, as wild-type DT40 cells expressing much lower levels of PECAM-1 (Figure 1A) inhibit calcium mobilization to a similar extent as do wild-type DT40 cells expressing higher levels of PECAM-1 (compare Figure 2A with Figure 4A). From these results, we conclude that the ability of PECAM-1 to modulate antigen receptor signaling is dependent on the presence of SHP-2.

Expression of wild-type PECAM-1 on the surface of wild-type and SHP-2-negative B-cell transfectants.

(A) Wild-type (left) or SHP-2–negative (right) DT40 cells were lysed in Triton X-100, and lysates were analyzed by anti-SHP-2 (αSHP-2; top) and anti-SHP-1 (αSHP-2; bottom) immunoblots. Note that wild-type DT40 cell lysates contain both SHP-2 and SHP-1, whereas SHP-2–negative DT40 cell lysates contained SHP-1 but not SHP-2. (B) Wild-type (left) and SHP-2–negative (right) DT40 cells were transfected with wild-type human PECAM-1. Transfectants were stained with normal mouse IgG1 (NMIgG) or with PECAM-1.3, a murine mAb specific for human PECAM-1 (αPECAM-1). Antibody-pretreated cells were then stained with FITC-conjugated GAM IgG and analyzed by flow cytometry. Transfectants chosen for analysis expressed equivalent levels of cell surface PECAM-1.

Expression of wild-type PECAM-1 on the surface of wild-type and SHP-2-negative B-cell transfectants.

(A) Wild-type (left) or SHP-2–negative (right) DT40 cells were lysed in Triton X-100, and lysates were analyzed by anti-SHP-2 (αSHP-2; top) and anti-SHP-1 (αSHP-2; bottom) immunoblots. Note that wild-type DT40 cell lysates contain both SHP-2 and SHP-1, whereas SHP-2–negative DT40 cell lysates contained SHP-1 but not SHP-2. (B) Wild-type (left) and SHP-2–negative (right) DT40 cells were transfected with wild-type human PECAM-1. Transfectants were stained with normal mouse IgG1 (NMIgG) or with PECAM-1.3, a murine mAb specific for human PECAM-1 (αPECAM-1). Antibody-pretreated cells were then stained with FITC-conjugated GAM IgG and analyzed by flow cytometry. Transfectants chosen for analysis expressed equivalent levels of cell surface PECAM-1.

SHP-2 is required for PECAM-1-mediated attenuation of calcium mobilization in B-cell transfectants.

PECAM-1–expressing (A) wild-type or (B) SHP-2–negative DT40 transfectants were loaded with Fura-2AM and preincubated for 10 minutes at room temperature with murine antichicken BCR together with the indicated concentration of F(ab′)2 fragments of PECAM-1.3 Ab (αPECAM-1 mAb). Cells were washed free of unbound Ab and then added to the warmed (37°C) chamber of an SLM 8100 spectrofluorometer. Calcium mobilization was induced by cross-linking of surface-bound Abs on addition of addition of F(ab′)2 fragments of GAM IgG. The intracellular calcium concentration was assessed every 3 seconds over a period of 120 seconds. Note that PECAM-1 co-ligation with the BCR fails to attenuate calcium mobilization in the absence of SHP-2.

SHP-2 is required for PECAM-1-mediated attenuation of calcium mobilization in B-cell transfectants.

PECAM-1–expressing (A) wild-type or (B) SHP-2–negative DT40 transfectants were loaded with Fura-2AM and preincubated for 10 minutes at room temperature with murine antichicken BCR together with the indicated concentration of F(ab′)2 fragments of PECAM-1.3 Ab (αPECAM-1 mAb). Cells were washed free of unbound Ab and then added to the warmed (37°C) chamber of an SLM 8100 spectrofluorometer. Calcium mobilization was induced by cross-linking of surface-bound Abs on addition of addition of F(ab′)2 fragments of GAM IgG. The intracellular calcium concentration was assessed every 3 seconds over a period of 120 seconds. Note that PECAM-1 co-ligation with the BCR fails to attenuate calcium mobilization in the absence of SHP-2.

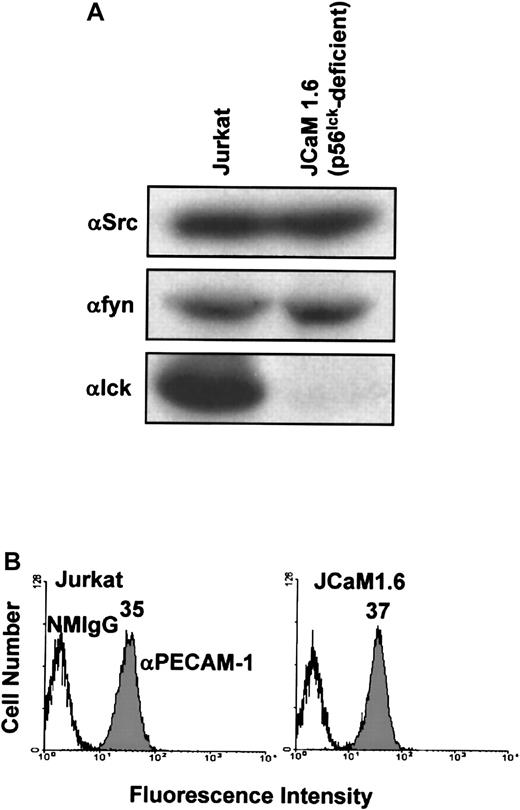

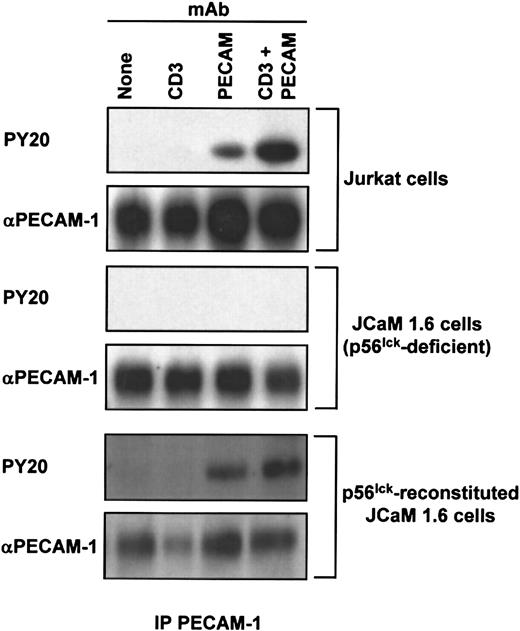

Last, we sought to determine the requirement for individual members of the Src family of PTKs for PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation in T cells. The major Src family PTK activated on ligation of the TCR in mature T cells is p56lck.1 Thus, we asked whether p56lck is required for PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation in T cells. To address this question, we made use of a p56lck-deficient variant Jurkat T-cell line, JCaM1.6. JCaM1.6 cells, as expected, expressed no p56lck, but they did express normal levels of pp60Src and p59fyn(Figure 5A) and had normal levels of PECAM-1 at the cell surface (Figure 5B). As previously observed,7 PECAM-1 became tyrosine phosphorylated in wild-type Jurkat cells stimulated by cross-linking of either the TCR alone, PECAM-1 alone, or by co–cross-linking of PECAM-1 and the TCR (Figure6, top). In contrast, PECAM-1 failed to become tyrosine phosphorylated under any of these conditions in p56lck-deficient JCaM1.6 cells (Figure 6, middle). Finally, PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation was restored in JCaM1.6 cells that were stably transfected with a p56lck-encoding plasmid and in which p56lckexpression was reconstituted (Figure 6, bottom). From these results, we conclude that p56lck is required for PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation in response to cross-linking of either the TCR or PECAM-1, and that, under these conditions, abundant levels of c-Src and p59fyn are unable to functionally compensate for the lack of p56lck.

Characterization of Src family PTK and PECAM-1 expression by wild-type Jurkat T cells and the p56lck-deficient Jurkat T-cell line, JCaM1.6.

(A) Wild-type Jurkat (left) or p56lck-deficient JCaM1.6 (right) T cells were lysed in Triton X-100, and lysates were analyzed by anti-pp60src (αSrc; top), anti-p59fyn(αfyn; middle), and anti-p56lck (αlck; bottom) immunoblots. Note that wild-type Jurkat T-cell lysates contain pp60src, p59fyn, and p56lck, whereas JCaM1.6 T cells contain pp60src and p59fyn but not p56lck. (B) Wild-type Jurkat (left) or p56lck-deficient JCaM1.6 (right) T cells stained with normal mouse IgG1 (NMIgG) or with PECAM-1.3, a murine mAb specific for human PECAM-1 (αPECAM-1). Antibody-pretreated cells were then stained with FITC-conjugated GAM IgG and analyzed by flow cytometry. Both cell lines expressed equivalent levels of cell surface PECAM-1.

Characterization of Src family PTK and PECAM-1 expression by wild-type Jurkat T cells and the p56lck-deficient Jurkat T-cell line, JCaM1.6.

(A) Wild-type Jurkat (left) or p56lck-deficient JCaM1.6 (right) T cells were lysed in Triton X-100, and lysates were analyzed by anti-pp60src (αSrc; top), anti-p59fyn(αfyn; middle), and anti-p56lck (αlck; bottom) immunoblots. Note that wild-type Jurkat T-cell lysates contain pp60src, p59fyn, and p56lck, whereas JCaM1.6 T cells contain pp60src and p59fyn but not p56lck. (B) Wild-type Jurkat (left) or p56lck-deficient JCaM1.6 (right) T cells stained with normal mouse IgG1 (NMIgG) or with PECAM-1.3, a murine mAb specific for human PECAM-1 (αPECAM-1). Antibody-pretreated cells were then stained with FITC-conjugated GAM IgG and analyzed by flow cytometry. Both cell lines expressed equivalent levels of cell surface PECAM-1.

p56lck is required for PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation in T cells.

Wild-type Jurkat (top), p56lck-deficient JCaM1.6 (middle), or p56lck-reconstituted JCaM1.6 (bottom) T cells were treated with no Ab (None; lane 1), 1 μg/mL of murine antihuman CD3ε (CD3; lane 2), 50 μg/mL of murine Ab specific for human PECAM-1 (PECAM, lane 3), or both anti-CD3ε and PECAM-1.3 (CD3 + PECAM; lane 4) at 4°C. After prewarming for 10 minutes at 37°C, receptor cross-linking was induced by addition of 100 μg/mL of GAM F(ab′)2. After a further incubation for 3 minutes, cells were lysed in Triton X-100, and PECAM-1 immunoprecipitates (IP PECAM-1) were prepared. Immunoblot analysis was performed to determine the extent of PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation, using an antiphosphotyrosine Ab (PY20; top panels) and the amount of PECAM-1 antigen present in the immunoprecipitates using the PECAM-1.3 Ab (αPECAM-1; bottom panels). Note that PECAM-1 does not become tyrosine phosphorylated in the absence of p56lck and that reconstitution of p56lck expression restores PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation.

p56lck is required for PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation in T cells.

Wild-type Jurkat (top), p56lck-deficient JCaM1.6 (middle), or p56lck-reconstituted JCaM1.6 (bottom) T cells were treated with no Ab (None; lane 1), 1 μg/mL of murine antihuman CD3ε (CD3; lane 2), 50 μg/mL of murine Ab specific for human PECAM-1 (PECAM, lane 3), or both anti-CD3ε and PECAM-1.3 (CD3 + PECAM; lane 4) at 4°C. After prewarming for 10 minutes at 37°C, receptor cross-linking was induced by addition of 100 μg/mL of GAM F(ab′)2. After a further incubation for 3 minutes, cells were lysed in Triton X-100, and PECAM-1 immunoprecipitates (IP PECAM-1) were prepared. Immunoblot analysis was performed to determine the extent of PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation, using an antiphosphotyrosine Ab (PY20; top panels) and the amount of PECAM-1 antigen present in the immunoprecipitates using the PECAM-1.3 Ab (αPECAM-1; bottom panels). Note that PECAM-1 does not become tyrosine phosphorylated in the absence of p56lck and that reconstitution of p56lck expression restores PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation.

Discussion

PECAM-1 was originally assigned to the family of immunoglobulin-like cellular adhesion molecules (CAMs) based on sequence similarity between its 6 extracellular immunoglobulin domains and those of other immunoglobulin domain-containing CAMs.24 However, more recent studies have revealed features of PECAM-1 that implicate it as a member of the immunoglobulin-like, ITIM-containing inhibitory receptor family (reviewed in3). Thus, PECAM-1 possesses ITIMs in its cytoplasmic domain,24 the PECAM-1 ITIMs, on tyrosine phosphorylation support binding of the cytoplasmic protein tyrosine phosphatase, SHP-2,4 and perhaps SHP-111 and SHIP,12 and tyrosine-phosphorylated PECAM-1 to which SHP-2 is bound attenuates calcium release from intracellular stores on co-ligation with the TCR.7 These previous observations have provided circumstantial evidence in favor of inclusion of PECAM-1 within the family of immunoglobulin-like, ITIM-containing inhibitory receptors. The present studies provide firmer evidence for this relationship by demonstrating that the PECAM-1 ITIMs and SHP-2 are required for its inhibitory function. In addition, we clarify the role of the Src family PTKs by showing that, in T lymphocytes, PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation depends on the presence of p56lck.

In the present study, we expand on previous observations that the PECAM-1 ITIMs become phosphorylated on tyrosine residues and bind SHP-2 by verifying that the presence of the PECAM-1 ITIMs is required for its inhibitory activity. Studies of another important regulator of T-cell activity, CTLA-4, have taught us that this is an important molecular connection to establish. The observations that (1) treatment of T cells with soluble anti-CTLA-4 Abs results in sequestration of CTLA-4 away from the TCR and augmentation of T-cell responses,25,26 (2) T-cell responses are inhibited on co-ligation of CTLA-4 with the TCR,25 and (3) CTLA-4 deficiency results in fatal lymphoproliferative disease27 support the role of CTLA-4 as an inhibitor of T-cell activation. The findings that CTLA-4 possesses cytoplasmic ITIMs that bind SHP-2 in a tyrosine phosphorylation-dependent manner suggested that the CTLA-4 ITIMs might be required for its inhibitory activity.28 However, studies have revealed that mutant forms of CTLA-4, in which the ITIM tyrosine residues are substituted with phenylalanine, retain full ability to bind SHP-229 and interfere with T-cell responses,8,9,30 suggesting that the inhibitory activity of CTLA-4 has more to do with its ability to compete with CD28 for binding to B/7.1 and B/7.2 than with its ability to become tyrosine phosphorylated and recruit a cytoplasmic PTP. Whereas PECAM-1 is unlike CTLA-4 in its dependence on ITIM phosphorylation and PTP binding for inhibitory activity, it is similar to other members of the immunoglobulin-like, ITIM-containing inhibitory receptor family, such as FcγRIIB,31 killer inhibitory receptors,32 and paired immunoglobulin-like receptor-B,33 for which it has been shown conclusively that inhibitory activity requires ITIM phosphorylation and phosphatase binding.

Our finding that PECAM-1 does not possess inhibitory activity in the absence of SHP-2 suggests that the reported interactions between PECAM-1 and either SHP-16,10,11 or SHIP12 are insufficient to support inhibitory function. The inability of PECAM-1/SHP-1 complexes to inhibit cellular responses may be attributable to the relatively low affinity of the PECAM-1/SHP-1 interaction. In support of this possibility, Sagawa et al6 found that SHP-1 precipitated less tyrosine-phosphorylated PECAM-1 than did SHP-2. In addition, Hua et al11 found that SHP-1 binds tyrosine-phosphorylated PECAM-1 with about 5-fold lower affinity than does SHP-2. Alternatively, a possible explanation for the inability of PECAM-1 to inhibit cellular responses in the presence of ample amounts of SHP-1 but no SHP-2 may be that targets of the antigen receptor signal transduction pathway that are dephosphorylated by PECAM-1/SHP-2 may not be dephosphorylated by PECAM-1/SHP-1 complexes. In support of this possibility, catalytic domain swapping studies have shown that the catalytic domains of SHP-1 and SHP-2 have different substrate specificities.34 35 Experiments are currently under way to identify the components of the TCR signal transduction pathway whose level of tyrosine phosphorylation is reduced on co-ligation of PECAM-1/SHP-2 complexes with the TCR relative to that observed on cross-linking of the TCR alone. Once the targets for dephosphorylation by PECAM-1/SHP-2 are identified, it should be possible to determine whether they are also substrates for dephosphorylation by SHP-1 bound to PECAM-1.

We found that, in the absence of p56lck, PECAM-1 fails to become tyrosine phosphorylated on cross-linking of the TCR and/or PECAM-1 in T cells and that, on reconstitution of p56lck expression, PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation in response to these stimuli is restored. This result is consistent with previous studies that demonstrate the ability of Src family PTKs to phosphorylate PECAM-1 in in vitro kinase assays,5,15 on overexpression in bovine aortic endothelial cells,14 or on transient transfection in COS-1 cells10 and also with a study showing that PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation was reduced or abolished by the Src family PTK inhibitor, PP2.16 One possible explanation for this finding is that PECAM-1 is a direct substrate of a Src family PTK but that, of the many Src family PTKs shown to be capable of mediating PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation, only p56lck has the appropriate target specificity under these conditions in T cells. Alternatively, it may be that other members of the Src family of PTKs could phosphorylate PECAM-1 in T cells but fail to do so because they do not become activated on TCR or PECAM-1 cross-linking. This conclusion is consistent with the finding that p56lck is the major Src family PTK activated in mature T cells on ligation of the TCR (reviewed in1). However, the extent to which PECAM-1 cross-linking induces activation of each of the Src family kinases is currently unknown. Our results do not, however, exclude the possibility that PECAM-1 is phosphorylated by a non-Src family kinase whose activation is dependent on the activity of p56lck. In T cells, the major Syk family PTK downstream of p56lck in TCR signaling is the ζ-associated protein of 70 kd (ZAP-70).36,37 Syk family PTKs have been implicated in PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation on the basis of a report that PECAM-1 becomes only minimally tyrosine phosphorylated on cross-linking of FcεRI in Syk-deficient rat basophilic leukemia cells.38 However, transient transfection of Syk failed to support PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation in COS-1 cells.10 Furthermore, studies in our own laboratory with the use of the ZAP-70–deficient Jurkat T-cell line, P116,39 revealed normal levels of PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation in the absence of ZAP-70 (data not shown). It has recently been shown, however, that Syk can compensate for the absence of ZAP-70 in T-cell signal transduction40; thus, the extent to which kinases downstream of p56lck might be involved in PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation remains to be established. Members of the Tec family of PTKs are also activated downstream of Src-family kinases in antigen receptor signal transduction pathways.13 However, the extent to which Tec kinases contribute to inhibitory receptor tyrosine phosphorylation in general, or to PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation in particular, has not yet been addressed.

In summary, we have found that the ability of PECAM-1 to function as an inhibitory receptor in T lymphocytes is dependent on the presence of intact ITIMs within its cytoplasmic domain, requires the recruitment and activation of SHP-2, and, in T cells, involves the activity of the Src family PTK, p56lck. Further definition of the signaling components affected by the PECAM-1/SHP-2 signaling complex is expected to provide important insights into the way this member of the immunoglobulin-ITIM family functions in blood and vascular cells.

We are grateful to Dr David Straus (University of Chicago) for generously providing p56lck-reconstituted JCaM1.6 cells, to Sara Hoffman for generating the data derived from this cell line and shown in Figure 6, and to Matthew Armstrong for technical assistance provided in the early phases of these studies.

Supported by grant P01 HL44612 from the National Institutes of Health and by the Blood Center Research Foundation.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Debra K. Newman, Blood Research Institute, The Blood Center of Southeastern Wisconsin, 638 N 18th St, Milwaukee, WI 53233; e-mail: dknewman@bcsew.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal