Abstract

The TEL gene on 12p12-13 is a target for a number of translocations associated with various hematological malignancies. The fusion of the TEL gene to the Sykgene in a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) with t(9;12)(q22;p12) is reported. Southern blot analysis of patient bone marrow cells with TEL and Syk gene probes detected rearranged fragments. Anchored polymerase chain reaction identified the Syk gene, a nonreceptor tyrosine kinase, on 9q22 fused downstream of TEL exon 5. The TELgene was fused in-frame to Syk and produced a fusion protein that was constitutively phosphorylated in tyrosine with dimerization that was mediated by the helix-loop-helix domain of TEL. A TEL-Syk fusion product transformed the murine hematopoietic cell line BaF3 to interleukin-3 growth factor independence. TEL-Syk is a novel transforming protein and leads to the transformation of hematopoietic cells. These data implicate that the rearranged Syk gene is involved in the pathogenesis of hematopoietic malignancies.

Introduction

The chromosomal translocations frequently observed in human malignant cells are known to represent a crucial step to carcinogenesis.1 Recent molecular studies have shown that the TEL gene located on 12p12-13 (also known as the E26 transforming-specific [ETS] translocation variant gene 6,ETV6) is frequently involved in chromosomal translocations in a variety of human leukemias.2 The TEL gene codes for a ubiquitously expressed nuclear protein that possesses a predicted pointed domain (PNT domain, also referred to as helix-loop-helix oligomerization domain) at its N-terminal end and an ETS DNA-binding domain at its C-terminal. TEL has been found fused to several partner genes including receptor tyrosine kinases,PDGFRβ (5q33)2 and TRKC(15q25)3; nonreceptor tyrosine kinases, JAK2(9p24),4,5ABL (9q34),6,7 andARG (1q25)8; and other genes,MDS1/EVI1 (3q26),9,10BTL(4q11-q13),11ACS2 (5q31),12STL (6q23),13AML1/CBFA2(21q22),14,15 and MN1 (22q11),16respectively.

The TEL gene was initially identified by cloning the t(5;12)(q33;p13) associated with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML).2 The TEL-PDGFRβ fusion results in the expression of a fusion transcript linking the PNT domain of TEL to the transmembrane and tyrosine kinase domain ofPDGFRβ, mediated the PNT domain of TEL, thereby leading to constitutive activation of its tyrosine kinase activity.17,18 The TEL-ABL fusion7and the TEL-JAK24 also have been reported to have constitutive kinase activation with the same mechanism.

The Syk gene located on 9q22 encodes a nonreceptor protein tyrosine kinase consisting of 2 tandem Src-homology 2 (SH2) domains and a catalytic domain at C-terminal end.19,20Syk is widely expressed in hematopoietic cells. Its activation has been implicated in a variety of hematopoietic cell responses including the Fc gamma receptor, B-cell antigen receptor, immunoglobulin E (IgE) receptor, several interleukin (IL) receptors, integrin, and αIIβ3. The Syk gene has revealed important roles in B- and T-cell development in association with differentiation and mitogen-activated kinase pathways.21-26 However, there is no case of leukemia involvement in the Syk gene.

We have previously reported a case of MDS with t(9;12)(q22;p12) that involved the TEL gene using the fluorescence in situ hybridization technique.27 This case presented with eosinophilia (9%), dry cough, and skin involvement progressing to leukemic transformation with megakaryocytic blast. We now report that the consequence of t(9;12)(q22;p12) is a TEL-Syk fusion gene which results in a novel activation of Syk due to its fusion to the TEL gene.

Materials and methods

Southern blot analysis

Genomic DNA was prepared from human myeloid cell HL-60 and bone marrow (BM) mononuclear cells of a previously reported patient after the initial diagnosis and with informed consent. Following digestion with HindIII, BamHI, andXbaI, the resulting DNA was electrophoresed on 0.7% agarose gel and transferred to Nylon filters (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Tokyo, Japan). The TEL complementary DNA (cDNA) probes T1 and T2 were a 543–base pair (bp) fragment spanning nucleotides (nt) 40-583 and a 277-bp fragment spanning nt 925-1202, respectively. TheSyk cDNA probe S was a 374-bp fragment spanning nt 738-1112. These were amplified by reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from human BM mononuclear cell cDNA using the following primers: TEL40F: 5′-CTCAGTCTAGCATTAAGCAG-3′; TEL583R: 5′-GAAGGCCGGTGATTTGTCG-3′; TEL925F: 5′-GGGAAGCCCATCAACCTCTCT-3′; TEL1202R: 5′-GGCGCAGGGCTCTGGACATTT-3′; Syk738F: 5′-AGACAACAACGGGCTCCTACG-3′; and Syk1112R: 5′-TGCAAGTTCTGGCTCATACG-3′. The probes were labeled with phosphorous 32–dicytidine 5′-triphosphate (32P-dCTP) by the random priming method, and Southern hybridization was performed as previously described.28 DNA sequence analysis of the resulting products confirmed the identity of the TEL andSyk cDNA.

RNA preparation and Northern blot analysis

Total RNA was isolated from the patient's BM mononuclear cells and HL-60 by the guanidium thiocyanate method. Poly(A)+ RNA was purified using oligo(dT)-Latex (Daiichikagaku, Tokyo, Japan), and 2μg was elecrophoretically separated on 1.2% formaldehyde/MOPS (3-[N-morpholino] propanesulfonic acid)–containing gel. Subsequently, it was transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and probed with probe T1, T2, and S labeled with 32P-dCTP. Northern blot analysis was performed as described previously.29

Anchored PCR and RT-PCR

Anchored PCR was adapted from the method of Frohman with minor modifications. A total of 5 μg RNA was treated with DNase (deoxyribonuclease) (Amersham Pharmacia) and reverse transcribed using Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV)–RT (Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, NY) and primer QT, 5′-TGAGCAGAGTGACGAGGACTCGAGCTCAAGCTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT-3′. An aliquot of cDNA was used as a template for 35 cycles of PCR at 94°C for 40 seconds, 58°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 6 minutes with TEL41F, 5′-CTCAGTGTAGCATTAAGCAGGAACG-3′, and primer Q0, 5′-CCAGTGAGCAGAGTGACG-3′. A second round of amplification was then performed using nested TEL338F, 5′-GATCTCCTCATTCAGGTGCTGTG-3′, and primer Q1, 5′-GATCTCCTCATTCAGGTGCTGTG-3′.30 The resulting 1500-bp product was cloned into the plasmid vector, pBluescript SK(−) (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), and sequenced. The DNA sequence was sent to the BLAST (Basic Logical Alignment Search Tool) server at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, MD, to compare with GenBank.

For RT-PCR, total RNA was converted to single-stranded cDNA using oligo(dT) primers and MMLV-RT. We performed PCR amplification withTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer Biosystems Japan, Tokyo, Japan) for 30 cycles using oligonucleotide primers at 94°C for 40 seconds, 65°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 1 minute. The 5′ and 3′TEL primers were TEL925F and 1202R, and the 5′ and 3′Syk primers were Syk738F and Syk1112R, respectively. PCR reaction products were then electrophoresed on 1.5% agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide.

DNA constructs and expression plasmids

Full-length Syk, TEL-Syk, and Syk-TEL cDNAs were constructed by PCR. The primers used to generate TELΔ PNT mutant by PCR amplification were: TEL206R, 5′-GGCGACGTCATCCCTGCTCC-3′; and TEL442F, 5′-AGCCGGACGTCATACTGCAT-3′, resulting in the deletion of nt 222-461 of the TEL gene. PCR products were confirmed by sequencing to be devoid of mutations. We used CMV early promoter-based expression vector pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) and influenza hemagglutinin (HA) epitope–tagged vector pHM6 (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN). Flag epitope-tagged vector pFlag and retroviral expression vector pBabeNeo have been described, respectively.31 32 TEL-Syk, TELΔ PNT-Syk, and Syk constructs were cloned into pcDNA3.1 and pFlag (pF-TS, pF-TΔ PS, and pF-S); TEL-Syk was cloned into pHM6 (pH-TS); and TEL-Syk, Syk-TEL, and TELΔ PNT-Syk were cloned into pBabeNeo (pB-TS, pB-ST, and pB-TΔ PS), respectively.

Antibodies

The antibodies used were anti-Syk monoclonal antibody (mAb) (Upstate Biotechnology Inc, Lake Placid, NY), antiphosphotyrosine mAb horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated PY-20 (ICN Biochemicals, Aurora, OH), anti-Flag mAb (Eastman-Kodak Company, New Haven, CT), and HRP-conjugated anti-HA mAb (Roche). Anti-Syk mAb was directed against nt 1083-1163 of Syk.

Cell transfection assays

COS-7 cells were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). pF-TS, pF-TΔPS, and pF-S were cotransfected with pH-TS into subconfluent COS-7 cells by the calcium-phosphate technique (20 μg per transfection).

The pCMV-G containing vesicular stomatitis virus envelope glycoprotein was cotransfected with pB-TS, pB-ST, and pB-TΔ PS or vector alone as a control into 293GP cells, a retrovirus packaging cell line expressing MMLV gag and pol genes.33 34 The IL-3–dependent murine leukemia BaF3 cells were infected with these supernatants in the presence of 5 μg/mL polybrene. G418-resistant BaF3 expressing the indicated proteins and control cells were grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS and 5 ng/mL recombinant murine IL-3. Cells were washed twice in IL-3–free medium and seeded in IL-3–free medium in 6-well plates at a concentration of 1.2 × 105 cells per milliliter. The number of cells showing proliferation in either the absence or presence of IL-3 in the culture was scored every day for 5 days.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis

Cells were solubilized in lysis buffer comprising 20 mM Tris-HCL (tris[hydroxymethyl] aminomethane–hydrochloride) (pH 7.4), 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 1% Triton X-100, and 1% sodium deoxycholate. The cell lysates were precleared by incubation with protein G-agarose (Gibco) overnight and centrifuged. The supernatants were incubated with the indicated antibodies for 1 hour followed by 20 μL 50% (vol/vol) protein G–agarose for 2 hours at 4°C. The immunoprecipitates were washed 3 times in lysis buffer. For immunoblotting, the precipitates were boiled with electrophoresis SDS sample buffer for 3 minutes. Whole cell lysates or immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE (polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) and transferred onto polyvinylidine difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The membrane blots were blocked with 5% skim milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS-T) or with blocking buffer comprising 15 M sodium chloride (NaCl), 10 mM/M malic acid, and 1% blocking reagent (pH 7.5) for the detection of PY-20 (Roche) for 1 hour at 37°C followed by incubation with primary antibodies in TBS-T for 2 hours at room temperature. Following washing, membranes were incubated with HRP-linked whole antimouse IgG antibody (Amersham Pharmacia) in TBS-T for 2 hours at room temperature. After washing, the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) assay was performed, and positive bands were identified on x-ray films.

Results

Identification of TEL-Syk in MDS

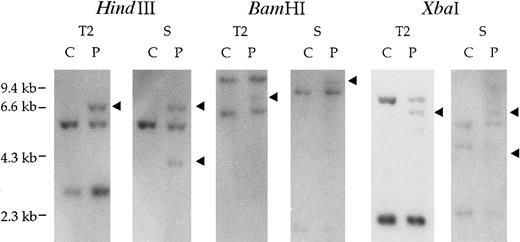

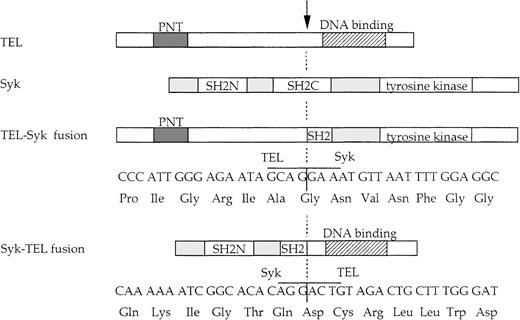

Southern blots of DNA from the patient's BM mononuclear cells with t(9;12), hybridized with the TEL probes T1 (data not shown) and T2 and the Syk probe S, are shown in Figure1. With probe T2, rearranged fragments were detected in each restriction digest of the patient's DNA, suggesting that the chromosome 12 breakpoint is localized to TEL exon 5-7. To identify the fusion partner on chromosome 12, we used anchored PCR with TEL primers to amplify the fusion transcript from the patient's BM cell cDNA. The resulting 1500-bp PCR product was cloned and sequenced. A database search showed that TEL was fused to nt 993 of exon 5, the sequence being completely identical to the Syk gene (Figure 2). We also confirmed the presence of rearranged bands detected with Syk probe S by Southern blot analysis.

Identification of t(9;12)(q22;p12).

Southern blot analysis of the patient's genomic DNA with t(9;12)(q22;p12) (P) and control cell, HL-60 (C). Genomic DNA samples (5μg each) were digested with HindIII,BamHI, and XbaI and hybridized with the TEL cDNA probe T2 (TEL925-1202) and Syk cDNA probe S (Syk738-1112). The arrows indicate the rearranged fragment in each of the digests.

Identification of t(9;12)(q22;p12).

Southern blot analysis of the patient's genomic DNA with t(9;12)(q22;p12) (P) and control cell, HL-60 (C). Genomic DNA samples (5μg each) were digested with HindIII,BamHI, and XbaI and hybridized with the TEL cDNA probe T2 (TEL925-1202) and Syk cDNA probe S (Syk738-1112). The arrows indicate the rearranged fragment in each of the digests.

Schematic representation of the TEL-Syk and Syk-TEL fusion proteins.

The nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the fusion proteins, normal TEL and Syk. The breakpoint, indicated by an arrow, occurs following TEL nt 1033 and Syk nt 993.

Schematic representation of the TEL-Syk and Syk-TEL fusion proteins.

The nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the fusion proteins, normal TEL and Syk. The breakpoint, indicated by an arrow, occurs following TEL nt 1033 and Syk nt 993.

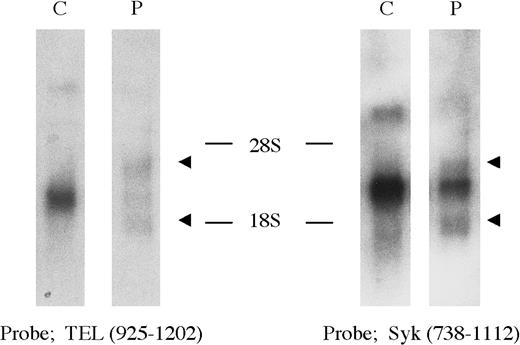

Expression of TEL-Syk fusion gene

Expression of the TEL, Syk, andTEL-Syk genes was examined by Northern blot analysis of RNA isolated from a blood sample of the same patient and HL-60 cell line (Figure 3). Wild-type 5.6- and 2.8-kb Syk transcripts and 6.5-, 4.5-, and 2.4-kbTEL transcripts were detected in HL-60 with theSyk probe S and the TEL probe T2, whereas novel 4.2- and 1.8-kb transcripts were specifically detected in the patient.

Northern blot analysis of the TEL-Syk transcript.

The TEL probe T2, located 5′ of the translocation breakpoint, detected wild-type 6.5-, 4.5-, and 2.4-kb transcripts present in HL-60; novel 4.2- and 1.8-kb transcripts were identified in the patient's mononuclear cells with t(9;12). The Syk probe S, located 3′ of the translocation breakpoint, detected the same 4.2- and 1.8-kb transcripts in the patient's cells, whereas 5.6- and 2.8-kb transcripts were detected in HL-60.

Northern blot analysis of the TEL-Syk transcript.

The TEL probe T2, located 5′ of the translocation breakpoint, detected wild-type 6.5-, 4.5-, and 2.4-kb transcripts present in HL-60; novel 4.2- and 1.8-kb transcripts were identified in the patient's mononuclear cells with t(9;12). The Syk probe S, located 3′ of the translocation breakpoint, detected the same 4.2- and 1.8-kb transcripts in the patient's cells, whereas 5.6- and 2.8-kb transcripts were detected in HL-60.

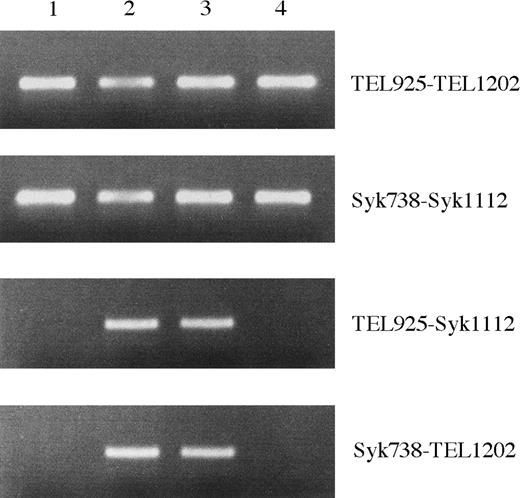

Identification of TEL-Syk and Syk-TELfusion transcript

RT-PCR analysis was performed to confirm the fusion transcripts between the TEL and Syk genes. We detected expression of TEL, Syk, TEL-Syk, andSyk-TEL genes in patient's BM cells upon initial diagnosis (Figure 4). The TEL-Syk andSyk-TEL fusion products were also detected at remission phase but not at postallogeneic BM transplantation (day 220).

Identification of TEL-Syk and Syk-TEL by RT-PCR.

RNA samples derived from the patient's BM mononuclear cells at initial diagnosis (lane 2), remission phase (lane 3), and postallogeneic BM transplantation day 220 (lane 4) and from HL-60 (lane 1) were reverse transcribed. Aliquots of cDNAs were amplified with the following primers: 5′ and 3′ TEL, 5′ and 3′ Syk, 5′ TEL and 3′ Syk, and 5′ Syk and 3′ TEL.

Identification of TEL-Syk and Syk-TEL by RT-PCR.

RNA samples derived from the patient's BM mononuclear cells at initial diagnosis (lane 2), remission phase (lane 3), and postallogeneic BM transplantation day 220 (lane 4) and from HL-60 (lane 1) were reverse transcribed. Aliquots of cDNAs were amplified with the following primers: 5′ and 3′ TEL, 5′ and 3′ Syk, 5′ TEL and 3′ Syk, and 5′ Syk and 3′ TEL.

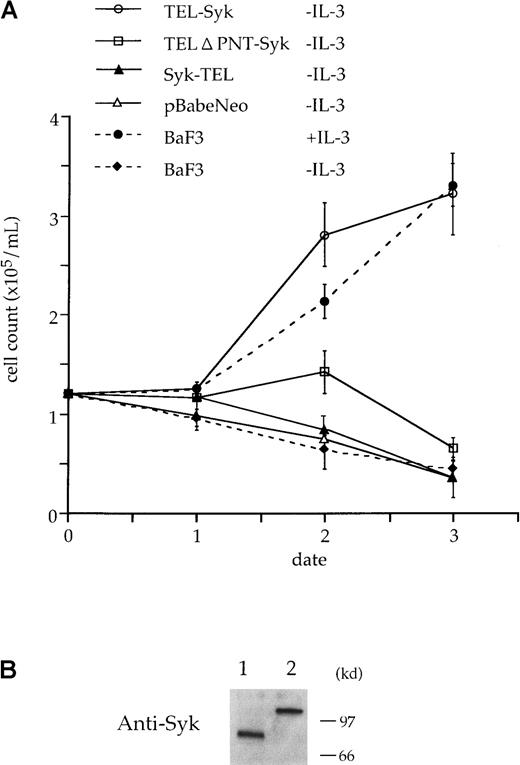

Mitogenic properties of the TEL-Syk

To analyze the importance of TEL-Syk for its mitogenic properties, we made use of the ability of the IL-3–dependent BaF3 to become independent of IL-3 for survival and proliferation. The IL-3–dependent murine leukemia BaF3 cells were infected with pB-TS, pB-ST, and pB-TΔ PS by retrovirus methods (Figure5). Cells were allowed to recover for 48 hours in growth medium plus IL-3 and then selected for G418 resistance for 2 weeks. To assay for IL-3 independence, infectants were switched to growth medium without IL-3. In the absence of IL-3, only the BaF3 cells with the intact TEL-Syk were found to be able to proliferate under these conditions (Figure6).

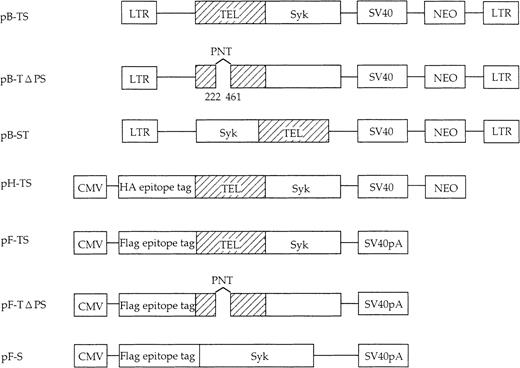

Schematic representation of constructed Syk, TEL-Syk, Syk-TEL, and deletion mutant TELΔ PNT-Syk (deletion of nt 222-461).

For immunoprecipitation and Western blot, TEL-Syk, TELΔ PNT-Syk, and Syk cDNAs cloned into pFlag (the Flag epitope tagged) and TEL-Syk cDNA into pHM (HA epitope tagged) were used. For high expression in BaF3 cells, TEL-Syk, Syk-TEL, and TELΔ PNT-Syk were cloned into the pBabeNeo construct, a retroviral vector based on a MMLV-expressing neomycin-resistant gene. LTR indicates long-terminal repeat; SV40, SV40 promoter; SV40pA, SV40 polyadenylation signal; and CMV, CMV promoter.

Schematic representation of constructed Syk, TEL-Syk, Syk-TEL, and deletion mutant TELΔ PNT-Syk (deletion of nt 222-461).

For immunoprecipitation and Western blot, TEL-Syk, TELΔ PNT-Syk, and Syk cDNAs cloned into pFlag (the Flag epitope tagged) and TEL-Syk cDNA into pHM (HA epitope tagged) were used. For high expression in BaF3 cells, TEL-Syk, Syk-TEL, and TELΔ PNT-Syk were cloned into the pBabeNeo construct, a retroviral vector based on a MMLV-expressing neomycin-resistant gene. LTR indicates long-terminal repeat; SV40, SV40 promoter; SV40pA, SV40 polyadenylation signal; and CMV, CMV promoter.

TEL-Syk transforms BaF3 cells to IL-3 factor independence.

(A) BaF3 cells were infected with pBabeNeo cloned with TEL-Syk, Syk-TEL, and TELΔ PNT-Syk or vector alone and then selected for G418 resistance for 2 weeks. G418-resistant cells were washed in IL-3–free medium and plated in RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS. Viable cells were counted on each day for 5 days. (B) BaF3 cells were infected with pB-TS or pB-TΔ PS, selected, and lysed. Lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane, and incubated with a mAb to Syk. TELΔ PNT-Syk (lane 1) and TEL-Syk (lane 2) proteins were expressed in BaF3 cells.

TEL-Syk transforms BaF3 cells to IL-3 factor independence.

(A) BaF3 cells were infected with pBabeNeo cloned with TEL-Syk, Syk-TEL, and TELΔ PNT-Syk or vector alone and then selected for G418 resistance for 2 weeks. G418-resistant cells were washed in IL-3–free medium and plated in RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS. Viable cells were counted on each day for 5 days. (B) BaF3 cells were infected with pB-TS or pB-TΔ PS, selected, and lysed. Lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane, and incubated with a mAb to Syk. TELΔ PNT-Syk (lane 1) and TEL-Syk (lane 2) proteins were expressed in BaF3 cells.

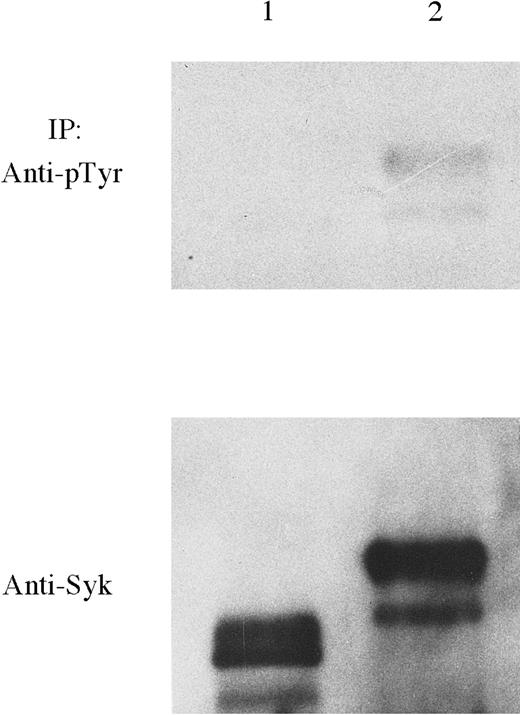

TEL-Syk is constitutively tyrosine-phosphorylated in vivo

Previous experiments have shown that TEL-induced oligomerization mediated by the PNT domain of TEL results in activation of TEL-PDGFRβ tyrosine kinase activity.4,7,17 18 To investigate whetherTEL-Syk is constitutively tyrosine-phosphorylated, we compared the autophosphorylation of TEL-Syk and TELΔ PNT-Syk in which the oligomerization domain (amino acids 66-145) was deleted. TEL-Syk and TELΔ PNT-Syk proteins expressed in COS-7 cells (pF-TS and pF-TΔ PS were transfected) were immunoprecipitated by the anti-Syk mAb. Subsequently, the immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane. Blots were probed using an antiphosphotyrosine mAb (Figure 7). A prominent 100-kd tyrosine-phosphorylated protein was only detected in TEL-Syk. Subsequent stripping and reprobing with the anti-Flag mAb confirmed that TEL-Syk and TELΔ PNT-Syk were equally immunoprecipitated.

TEL-Syk is constitutively tyrosine-phosphorylated in COS-7 cells.

COS-7 cells were transfected with pFlag-TELΔ PNT-Syk (lane 1) or TEL-Syk (lane 2), lysed, and immunoprecipitated with a mAb to Syk. Immunoprecipitants were then separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane, and blotted using HRP-conjugated tyrosine-phosphorylated antibody (PY20) and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection methods. Stripping and reprobing were performed using a mAb to Syk. Both proteins were immunoprecipitated.

TEL-Syk is constitutively tyrosine-phosphorylated in COS-7 cells.

COS-7 cells were transfected with pFlag-TELΔ PNT-Syk (lane 1) or TEL-Syk (lane 2), lysed, and immunoprecipitated with a mAb to Syk. Immunoprecipitants were then separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane, and blotted using HRP-conjugated tyrosine-phosphorylated antibody (PY20) and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection methods. Stripping and reprobing were performed using a mAb to Syk. Both proteins were immunoprecipitated.

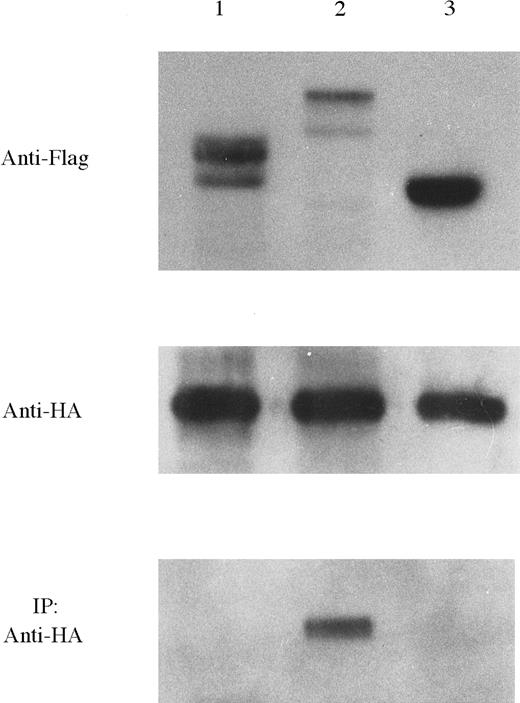

To investigate TEL-induced oligomerization properties, we compared the properties of intact TEL-Syk with TELΔ PNT-Syk. We cotransfected pF-TS, pF-TΔ PS, and pF-S with pH-TS into COS-7 cells by the calcium-phosphate technique, respectively. Western blot analysis confirmed expression of plasmids for either Flag epitope or HA epitope tag. Transfected proteins were immunoprecipitated using the Flag-specific mAb. Immunoprecipitated proteins were fractionated on SDS-PAGE and analyzed with HRP-conjugated anti-HA mAb (Figure8). Neither TELΔ PNT-Syk nor Syk were coimmunoprecipitated with TEL-Syk. These data suggest thatTEL PNT domain is required for oligomerization.

TEL-Syk dimerized in COS-7 cells that required the PNT domain of TEL.

In immunoprecipitation study, COS-7 cells were cotransfected with each Flag-tagged and HA-tagged constructs: pF-TΔ PS/pH-TS (lane 1), pF-TS/pH-TS (lane 2), and pF-S/pH-TS (lane 3). Lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane, and then probed using anti-Flag mAb. Subsequently, membranes were probed using HRP-conjugated HA mAb. Cells were then lysed and immunoprecipitated with a specific antibody for Flag epitope tag. Immunoprecipitants were then separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane, and probed with HRP-conjugated anti-HA mAb.

TEL-Syk dimerized in COS-7 cells that required the PNT domain of TEL.

In immunoprecipitation study, COS-7 cells were cotransfected with each Flag-tagged and HA-tagged constructs: pF-TΔ PS/pH-TS (lane 1), pF-TS/pH-TS (lane 2), and pF-S/pH-TS (lane 3). Lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane, and then probed using anti-Flag mAb. Subsequently, membranes were probed using HRP-conjugated HA mAb. Cells were then lysed and immunoprecipitated with a specific antibody for Flag epitope tag. Immunoprecipitants were then separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane, and probed with HRP-conjugated anti-HA mAb.

Discussion

Here we showed the existence of new fusion genesTEL-Syk and Syk-TEL as a result of the t(9;12)(q22;p12) with MDS. In TEL-Syk transcript, exons 1-5 of TEL containing the PNT domain, are fused toSyk containing a part of the C-terminal SH2 and the complete protein kinase domain. We also showed that the TEL-Sykfusion gene results in the constitutive activation of Sykkinase activity and demonstrates mitogenic potency. The reciprocal fusion protein, Syk-TEL, containing the SH2 domains and an ETS DNA-binding domain did not acquire transforming potency. It is well-established that receptor tyrosine kinases are activated by dimerization.35,36 However, most nonreceptor kinases are activated through transphosphorylation events involving receptor or other nonreceptor kinases. Recent experiments have shown that theTEL gene contributes to the pathogenesis through constitutive activation of the protein kinase which results in fusion of TEL to another nonreceptor tyrosine kinase, theABL7 and JAK2 genes4; this fusion is similar to the TEL-PDGFRβfusion.17 18 These data emphasized the importance of theTEL PNT domain as a self-associated motif leading to constitutive activation of the tyrosine kinase partner.

Here we reported that the TEL-Syk fusion induces oligomerization and results in constitutive activation ofSyk as assessed by tyrosine autophosphorylation. TheTEL-Syk fusion is an oncoprotein that transforms the hematopoietic cell line BaF3 to growth factor independence. On the other hand, TELΔ PNT-Syk is not tyrosine-phosphorylated and is incapable of growth in the absence of IL-3. These data show that the PNT domain ofTEL is required for transformed activity as well as oligomerization.

This is the first report to demonstrate the involvement of Syk in the pathogenesis of leukemia. Syk is a nonreceptor tyrosine kinase, and the localization of Syk to the receptor is mediated through a high-affinity interaction between the SH2 domain of Syk and immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) that is present in several receptors.37 The phosphorylation event of Syk is required for subsequent downstream signaling: activation of the Ras-MAPK and Rac1-JNK pathways as well as cytokine expression.22,23,38However, little is known about the activation mechanism of Syk without receptors. A recent study showed that cytoplasmic protein tyrosine kinase is maintained in an auto-inhibited state by means of intramolecular interactions between the SH2 and catalytic domain, and this conformational change contributes to the activation.39 We favor the hypothesis that Syk dimerization may be necessary for tyrosine kinase activation and subsequent activation of Syk-dependent signaling pathways. TheTEL-Syk fusion gene may provide a novel tool for the analysis of the Syk-mediated signal transduction.

The patient with MDS in this study received allogeneic BM transplantation at first remission due to the presence of malignant cells with t(9;12) detectable by RT-PCR at complete remission. The transcripts were identified at remission phase but not at postallogeneic transplantation. Detection of fusion transcripts by RT-PCR was important for the evaluation of a clinical cure and the presence of minimal residual disease at the level of stem cells.

In conclusion, this is the first demonstration that Syk plays an important role in malignant progression. The data presented here support the hypothesis that ectopic constitutive activation of Syk resulting from the TEL-Syk fusion increases activation of several signal pathways and demonstrates the oncogenic potential of Syk. In future experiments, we will attempt to clarify whether the constitutive activation of Syk is expressed in various hematological malignancies and whether a specific signal transduction pathway after activation by TEL-Syk is alternated in normal Syk signaling pathway.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Kaoru Tohyama, Fumihiko Hayakawa, Akihiro Tomita, and Kazuhito Yamamoto for helpful discussions and Satoru Suzuki and Chika Wakamatsu for their excellent technical assistance.

Supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (no. 10670941) from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan, Japan.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Yoshie Kuno, First Department of Internal Medicine, 65 Tsurumaicho, Showaku, Nagoya 466-8550, Japan; e-mail :kunoy@tsuru.med.nagoya-u.ac.jp

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal