Fc receptors play an important role in leukocyte activation and the modulation of ligand binding (“activation”) is a critical point of regulation. Previous studies demonstrated that the Fc receptor for IgA (FcαRI/CD89) is regulated by cytokine stimulation, switching it to a high-binding state. To investigate the mechanism by which cytokine-induced signal transduction pathways result in FcαRI activation, cell lines expressing various receptor mutants were generated. Binding studies indicated that truncation of the C-terminus of the FcαRI resulted in constitutive IgA binding, removing the need for cytokine stimulation. Furthermore, mutagenesis of a single C-terminal serine residue (S263) to alanine (S>A) (single-letter amino acid codes) also resulted in constitutive IgA binding, whereas a serine to aspartate (S>D) mutation was no longer functional. The role of S263 might be in regulating the interaction with the cytoskeleton, because disruption of the cytoskeleton results in reduced IgA binding to both FcαRwt and FcαR_S>A. In addition, overexpression of a membrane-targeted intracellular domain of FcαR, and the introduction of cell-permeable CD89 fusion proteins blocked IgA binding, implying a competition for endogenous proteins. The proposal is made that Fc receptors are activated by cytokines via an inside-out mechanism converging at the cytoplasmic tail of these receptors.

Introduction

Transmembrane receptors specific for the Fc region of immunoglobulins, Fc receptors (FcRs), play an important role in leukocyte activation by the recognition and binding of opsonized particles during inflammatory processes.1 Specific FcRs exist for all 5 classes of human immunoglobulins. The best studied FcRs are the leukocyte receptors for IgG (FcγR) and IgE (FcεR), due to early isolation of their genes and the availability of anti-FcR antibodies.2,3 Relatively little is known about the receptor(s) for IgA (FcαR). FcαRI (CD89) has been described to be expressed on many cell types, including monocytes/macrophages, neutrophils, and eosinophils4-7; however, little is known about its regulation and functioning.6 7

We have previously demonstrated that activation of the FcR for IgA (FcαR) and IgG (FcγRII) on primary human eosinophils is regulated by Th2-derived cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-5.8,9 Cytokine stimulation leads to an increase in ligand binding, without changing the levels of receptor expression, suggesting that stimulation with cytokines regulates either the affinity or avidity of FcR.8-10

To understand the mechanism by which FcR activation is regulated, we have studied the regulation of the human FcR for IgA (FcαR/CD89) by cytokines in a murine pre-B (Ba/F3) model system as well as in primary human eosinophils. By expressing various receptor mutants we demonstrate that the intracellular domain of FcαRI is important for its regulation by cytokines. Furthermore, we also present data showing that the cytoskeleton is important for correct FcR activation. Our data demonstrate that this process of cytokine-induced inside-out signaling is similar to that observed in the regulation of the integrin family of cell surface adhesion receptors.11-13 This inside-out signaling regulating FcRs is a rapid mechanism that allows cells to respond quickly to their environment.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

Ficoll-paque and Percoll were obtained from Pharmacia (Uppsala, Sweden). N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP) was purchased from Sigma Chemical (St Louis, MO). Human serum albumin (HSA) was from the Central Laboratory of the Netherlands Red Cross Blood Transfusion Service (Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Purified human serum IgA (> 20 mg/mL) was obtained from Cappel (Malvern, PA). It contained no detectable trace of IgG, IgM, or nonimmunoglobulin serum proteins. Recombinant human IL-5 was a gift from Dr M. McKinnon, GlaxoWellcome (Stevenage, United Kingdom). Recombinant mouse IL-3 was produced in COS cells.14 For the detection of FcαR (CD89) with a FACSvantage flow cytometer we used a specific phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated monoclonal antibody A59 (A59-PE, Pharmingen, Torrey Pines, CA). Specific HIV-tat coupled peptides for inhibition studies were purchased from Eurogentec (Liège, Belgium). Cytochalasin D was ordered from Sigma Chemical.

FcαR mutants

The FcαRwt and FcαR mutants were cloned into a pMT2 vector containing a VSV-epitope tag. Human FcαR (in pSG513)15was used as a template and several substitution and deletion constructs were generated via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the following primers: FcαRwt (Fwt: GCTGTCAGCACGATGGAC and Rwt: TTCACCTCCAGGTGTTTA), FcαRS263A (Fwt and RS>A: CTTGCAGACAGCTGGTG), FcαRS263D (Fwt and RS>D: CTTGCAGACATCTGGTG), FcαRΔic (Fwt and RΔ229: GTGCCAATTTTCAACCAG) and FcαRΔ262 (Fwt and RΔ262: TGGTGTTCGTGCAAAGGT). Gag-FcαR (aa226-266) and gag-Δ262 (aa226-262) constructs were generated using pMT2_FcαRwt_VSV and pMT2_FcαRΔ262_VSV as a template and PCR was performed with Fgag (GAAAATTGGCACAGC) and Rgag (TCTAGATTACTTTC) primers. PCR products were cloned into pCDNA3, via a vector that contained the murine Moloney leukemia virus (MuMoLV) gag sequence.16 The intracellular domains of FcαRwt and FcαRS263A were fused to GST. Constructs were generated using pMT2_FcαRwt_VSV and pMT2_FcαRS>A_VSV as a template and performing PCR with FGST (GAAAATTGGCACAGCC) and Rwt or RS>A primers. PCR products were cloned into a pRP265 glutathione vector and proteins were expressed inEscherichia coli. All construct were verified by sequencing.

Generation of stable transfectants

The Ba/F3 cells were cultured at a cell density of 105 to 106 cells/mL in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 8% Hyclone serum (Gibco, Rockville, MD) and recombinant mouse IL-3. For the generation of polyclonal transfectants pMT2_VSV containing FcαRwt or mutants were electroporated into Ba/F3 cells (0.28 V; capacitance 960 μFD) together with pSG5-CMV-Hygro containing the hygromycin resistance gene. Cells were cultured in the presence of IL-3 and selected in 500 μg/mL hygromycin (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany). After 2 weeks of selection, cells were tested for FcαR expression and positive cells were sorted with a FACSvantage flowcytometer (Becton and Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, Mountain View, CA). Briefly, FcαR transfected Ba/F3 cells were incubated with the PE-conjugated monoclonal antibody (mAb) A59 (A59-PE) for 30 minutes at 4°C. Fluorescence of the cells was quantified with the flow cytometer and A59+ cells were sorted and cultured. In this way polyclonal cell lines expressing either FcαRwt, deletion mutants Δic and Δ262, or substitution mutants S263A and S263D were generated. Ba/F3_FcαRwt cells, expressing FcαRwt_VSV were subsequently used for transfection of pCDNA3 containing either gag_FcαR or gag-Δ262. Cells were cultured with mouse IL-3 and 500 μg/mL G418 (Boehringer Mannheim) to select resistance. Stable cell lines were grown continually on murine IL-3, G418, and hygromycin. Expression of FcαR was checked regularly with the flow cytometer.

Isolation of eosinophils

Blood was obtained from healthy volunteers from the Red Cross Blood Bank, Utrecht, The Netherlands. Eosinophils were isolated as described previously17 and resuspended in incubation buffer (20 mM Hepes, 132 mM NaCl, 6.0 mM KCl, 1.0 mM MgSO4, 1.2 mM KH2 PO4, supplemented with 5 mM glucose, 1.0 mM CaCl2, and 0.5% [wt/vol] HSA). Purity of eosinophils was 97% (± 0.5 SEM), and recovery was usually 60% to 70%.

IgA-binding assays

The IgA-binding assays were performed either with purified human eosinophils or with cytokine-starved Ba/F3 cells. For IL-3 starvation, Ba/F3 cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and left in medium (RPMI 1640 with 0.5% serum) without IL-3 for 4 hours. Prior to performing a binding assay, Ba/F3 cells or purified eosinophils were washed with Ca++-free incubation buffer containing 0.5 mM EGTA and brought to a concentration of 8 × 106 cells/mL. A 50-μL cell suspension (0.4 × 106 cells) was incubated at 37°C, with or without cytokines. Ba/F3 cells were preincubated with IL-3 (1:1000; 15 minutes). Human eosinophils were stimulated with IL-5 with a final concentration of 10−9 M. After stimulation of the cells, Dynabeads coated with serum IgA (10 mg/mL) as described previously17 were added in a ratio of 3.5 beads/cell. After briefly mixing, the cells and beads were pelleted for 15 seconds at 100 rpm and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. After incubation cells were resuspended vigorously and IgA binding was evaluated under a microscope. All cells that had bound 2 beads or more were defined as rosettes. One hundred cells were scored and the number of beads that were bound to the cells was counted. The amount of beads bound to a total of 100 cells (bound and unbound to beads) was designated as the rosette index. As described previously, the rosetting method with magnetic beads is specific because there is no appreciable background binding of cells to beads coated with ovalbumin.18 19

Inhibition of IgA binding

Cytochalasin D was used to study the involvement of the cytoskeleton. Cytokine-starved Ba/F3 cells or freshly isolated eosinophils were preincubated with cytochalasin D (1 or 10 μM) for 10 minutes prior to cytokine stimulation.

Specific tat-peptides were designed for inhibition studies. These peptides consist of a 12–amino acid sequence of the HIV-tat peptide,18 20 necessary for entering a cell, coupled to either a specific amino acid sequence of FcαR (C-terminal aa254-266) or a scrambled sequence (SCR). The following tat-peptides were purchased from Eurogentec: tat_FcαR (YGRKKRRQRRRG-PGLTFARTPSVCK), tat_S263A (YGRKKRRQRRRG-PGLTFARTPAVCK) and tat_SCR (YGRKKRRQRRRG-PSFVLAPKGRTCT). Before stimulation cells were incubated for 10 minutes at 37°C with these peptides at a concentration of 100 μM. After stimulation IgA-binding assays were performed as described above.

In vitro kinase assay

Fusion proteins, consisting of the intracellular domain of FcαRwt or FcαR_S>A coupled to GST, were used as substrates for in vitro kinase assays. Equal amounts of GST proteins were precoupled to glutathione beads for 30 minutes at 4°C, and washed prior to use. Cytokine-starved Ba/F3 cells (5 × 106) and freshly isolated human eosinophils (5 × 106) were lyzed in 50 μL lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5,100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100) supplemented with aprotinin (10 μg/mL), leupeptin (10 μg/mL), and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). After addition of 450 μL kinase buffer (25 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 25 mM MgCl2, 50 μM rATP, 3 μCi γ32P]-ATP), lysates were incubated with GST substrates for 30 minutes at room temperature. Samples were washed 8 × with lysis buffer before addition of 5 × Laemmli sample buffer and analyzed by electrophoresis on 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gels. Substrate phosphorylation was detected by autoradiography.

Results

The cytoplasmic domain of FcαR is important for cytokine-induced ligand binding

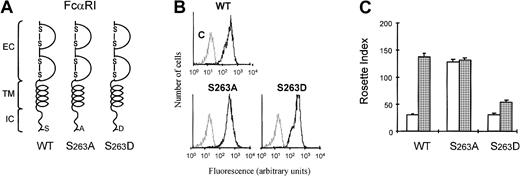

We have previously shown that ligand binding to FcRs on human eosinophils is modulated by cytokine-induced activation of PI3K.19 To understand how the PI3K-mediated signal from the cytokine receptor can modulate the function of FcαRI (CD89), we generated stable cell lines expressing intracellular deletion mutants of FcαR in Ba/F3 cells. As shown in Figure1A, deletion mutant FcαRIΔic lacks the complete intracellular domain (from aa229), whereas in FcαRIΔ262 the 4 C-terminal amino acids (aa263-266) were deleted. Cells transfected with FcαRI or mutants were stained with CD89 antibody (A59-PE) and sorted with a FACS flow cytometer, to obtain polyclonal cell lines expressing high levels of FcαRI (CD89) (Figure1B). As shown in Figure 1C, cells expressing FcαRwt did not bind IgA beads when IL-3 had been removed for 4 hours (Figure 1C, white bar). In contrast, addition of IL-3 to these cells resulted in a high level of IgA binding. Expression of the mutant FcαRIΔic resulted in constitutive IgA binding that was not modulated by cytokines (Figure1C). We generated several deletion mutants of the receptor to locate the region whereby cytokine-induced control of the receptor was mediated. It turned out that deletion of C-terminal amino acids 262 to 266 resulted in an increase in IgA binding. Interpretation of data obtained with deletion mutants can be complicated by nonspecific structural changes of the receptor. Therefore, we examined whether S263 might be important for receptor activation, because this 4–amino acid stretch (262-266) contains a serine residue at this position. As shown in Figure 2, substitution of the serine residue by an alanine residue (FcαRS>A) resulted in an FcαRI that constitutively binds IgA (Figure 2C), independently of cytokine stimulation. In contrast, mutation of S263 to an aspartic acid led to a receptor that could only weakly bind IgA, even after cytokine stimulation (Figure 2C).

The intracellular domain of FcαRI is important for cytokine-induced IgA binding.

(A) Schematic diagrams of FcαRI and different FcαR-deletion mutants are shown. (B) The expression of the receptors was analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) Ba/F3 cells expressing FcαRI mutants were used for IgA-rosette assays. Cells were cytokine starved and subsequently stimulated for 15 minutes with either buffer (■) or IL-3 (░). IgA binding to the cells was measured by the formation of rosettes between cells and IgA-coated beads. Results are expressed as rosette index and as means ± SE (n = 3).

The intracellular domain of FcαRI is important for cytokine-induced IgA binding.

(A) Schematic diagrams of FcαRI and different FcαR-deletion mutants are shown. (B) The expression of the receptors was analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) Ba/F3 cells expressing FcαRI mutants were used for IgA-rosette assays. Cells were cytokine starved and subsequently stimulated for 15 minutes with either buffer (■) or IL-3 (░). IgA binding to the cells was measured by the formation of rosettes between cells and IgA-coated beads. Results are expressed as rosette index and as means ± SE (n = 3).

S263 is critical for FcαRI activation by cytokines.

(A) Schematic diagrams of FcαRI and different S263 substitution mutants are shown. (B) The expression of the different receptors was analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) Ba/F3 cells expressing FcαRI mutants were used for IgA-rosette assays. Cells were cytokine starved and subsequently stimulated for 15 minutes with either buffer (■) or IL-3 (gray bars). IgA binding to the cells was measured by the formation of rosettes between cells and IgA-coated beads. Results are expressed as rosette index and as means ± SE (n = 3).

S263 is critical for FcαRI activation by cytokines.

(A) Schematic diagrams of FcαRI and different S263 substitution mutants are shown. (B) The expression of the different receptors was analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) Ba/F3 cells expressing FcαRI mutants were used for IgA-rosette assays. Cells were cytokine starved and subsequently stimulated for 15 minutes with either buffer (■) or IL-3 (gray bars). IgA binding to the cells was measured by the formation of rosettes between cells and IgA-coated beads. Results are expressed as rosette index and as means ± SE (n = 3).

Because a negatively charged aspartic acid might mimic the phosphorylation of this residue, we hypothesized that phosphorylation of S263 may be involved in the negative regulation of FcαRI.

Phosphorylation of the intracellular domain of FcαRI

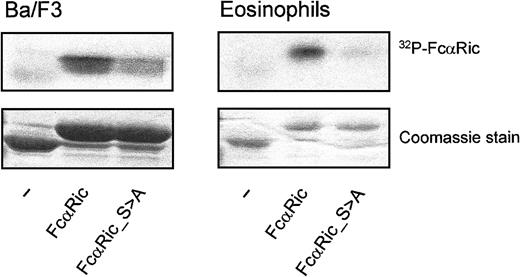

To investigate whether FcαRI is indeed phosphorylated in resting Ba/F3 cells or eosinophils, we performed in vitro kinase assays with the intracellular domain of FcαRI as a substrate. Whole cell lysates of IL-3–starved Ba/F3 cells (Figure 3A) and freshly isolated eosinophils (Figure 3B) were incubated with the GST-coupled intracellular domain of FcαRwt or FcαR_S>A. As shown in Figure 3, the intracellular tail of FcαRwt was indeed phosphorylated by total lysates of unstimulated cells. In contrast, this intracellular tail with an S>A substitution on residue 263 was not phosphorylated by either of the cell lysates (Figure 3, right lanes). These data suggest that the phosphorylation state of S263 may indeed contribute to the regulation of ligand-binding to FcαR.

Phosphorylation of the intracellular domain of FcαRI.

The intracellular domain of CD89 is constitutively phosphorylated in nonprimed cells. This phosphorylation is critically controlled by S263. GST-tagged intracellular domains of CD89 are used for an in vitro kinase assay with eosinophil and Ba/F3 lysates. Hereafter, constructs are “fished” with glutathione-coated beads and visualized by autoradiography (upper panels) and protein staining for checking equal loading (lower panels). The experiment shown is representative of 3 additional experiments.

Phosphorylation of the intracellular domain of FcαRI.

The intracellular domain of CD89 is constitutively phosphorylated in nonprimed cells. This phosphorylation is critically controlled by S263. GST-tagged intracellular domains of CD89 are used for an in vitro kinase assay with eosinophil and Ba/F3 lysates. Hereafter, constructs are “fished” with glutathione-coated beads and visualized by autoradiography (upper panels) and protein staining for checking equal loading (lower panels). The experiment shown is representative of 3 additional experiments.

Involvement of the cytoskeleton in FcαRI activation

The mechanism of cytokine-induced inside-out signaling of FcαRI appears to be similar to the regulation of integrin activation.11-13 Integrin regulation by inside-out signaling is well established, although different signaling pathways are involved in regulation of different integrins, depending on the cellular context and the activation stimuli used. Interactions of integrins with the cytoskeleton are also thought to be important for their (in)activation.12 18 To investigate whether the cytoskeleton may also be critically involved in the regulation of FcRs, we studied the importance of an intact cytoskeleton for correct FcαRI functioning. Incubation of cells with cytochalasin D enabled us to study the effect of disrupting the cytoskeleton on FcαR activation in both Ba/F3 cells (Figure 4A) and primary eosinophils (Figure 4B). As shown in Figure 4A, cytokine-stimulated Ba/F3_FcαRI cells did not bind IgA when they were pretreated with cytochalasin D, suggesting that correct assembly of cytoskeletal proteins is necessary for activation of FcαRI. Interestingly, FcαR_S>A also could not bind IgA after cytochalasin D treatment. Comparable with Ba/F3_FcαRI cells, binding to IL-5–treated eosinophils was also completely abolished by disruption of cytoskeletal organization (Figure 4B). These data suggest that besides the phosphorylation state of S263, the interaction of FcαRI with the cytoskeleton is also crucial for correct activation.

Cytokine-induced activation is inhibited by cytochalasin D.

Cytokine-starved Ba/F3_FcαRI cells (A) or purified eosinophils (B) were incubated with buffer (■) or with cytochalasin D for 10 minutes and subsequently stimulated or left untreated. Ba/F3_FcαRI cells were incubated with IL-3 (1:1000; 15 minutes) (A) and eosinophils were stimulated with IL-5 (10−9M; 15 minutes) (B). Binding of IgA beads to these cells was measured and results are expressed as rosette index (number of beads/100 cells) and as means ± SE (n = 3).

Cytokine-induced activation is inhibited by cytochalasin D.

Cytokine-starved Ba/F3_FcαRI cells (A) or purified eosinophils (B) were incubated with buffer (■) or with cytochalasin D for 10 minutes and subsequently stimulated or left untreated. Ba/F3_FcαRI cells were incubated with IL-3 (1:1000; 15 minutes) (A) and eosinophils were stimulated with IL-5 (10−9M; 15 minutes) (B). Binding of IgA beads to these cells was measured and results are expressed as rosette index (number of beads/100 cells) and as means ± SE (n = 3).

Overexpression of the FcαRI cytoplasmic domain inhibits IgA binding to the full-length receptor

Because the intracellular domain of FcαRI was critical for ligand binding, we were interested in studying whether overexpression of the intracellular tail of FcαRI could inhibit the activation of the receptor. This would implicate the involvement of an associating protein in the activation of the receptor. To specifically express the cytoplasmic tail at the membrane, we coupled the intracellular domain of FcαRI to the viral gag-sequence from MuMoLV.16 As a result of myristoylation of this gag-sequence, a fusion protein is targeted to the membrane. In this way, we overexpressed membrane targeted gag-fusions with either the complete intracellular domain of FcαRI (gag_wt) or the cytoplasmic domain lacking the last 4 amino acids (gag_Δ262) (Figure 5A,B). Overexpression of the complete intracellular domain abrogated the IL-3–dependent up-regulation of IgA binding (Figure 5C). However, when the intracellular region lacked the last 4 amino acids, there was no inhibition of IL-3–induced FcαRI modulation. This suggested that the overexpressed cytoplasmic domain can compete with the full-length FcαRI for certain proteins necessary for proper receptor regulation.

Overexpression of the intracellular domain of FcαRI inhibits the binding of IgA beads to Ba/F3 cells.

Ba/F3_FcαRI cells overexpressing gag-tagged FcαRI constructs (A) were checked for FcαRI expression by FACS flow cytometry (B). Cells were used for IgA-binding assays and were cytokine starved and stimulated with either buffer (■) or IL-3 (░) (C). After stimulation rosette assays were performed, and binding of IgA beads was counted. Results are expressed as rosette index (number of beads/100 cells) and as means ± SE (n = 3).

Overexpression of the intracellular domain of FcαRI inhibits the binding of IgA beads to Ba/F3 cells.

Ba/F3_FcαRI cells overexpressing gag-tagged FcαRI constructs (A) were checked for FcαRI expression by FACS flow cytometry (B). Cells were used for IgA-binding assays and were cytokine starved and stimulated with either buffer (■) or IL-3 (░) (C). After stimulation rosette assays were performed, and binding of IgA beads was counted. Results are expressed as rosette index (number of beads/100 cells) and as means ± SE (n = 3).

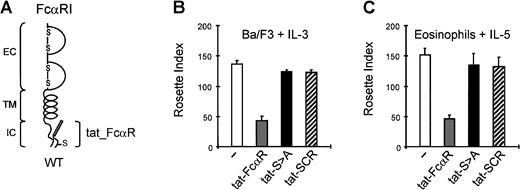

In contrast to Ba/F3 cells, eosinophils are refractory to DNA transfection and to perform competition experiments in primary cells, another approach was required. Recently, it has been described that the coupling of peptides to a specific short amino acid sequence of the tat protein of HIV results in the uptake of these peptides into cells.18,20 21 We designed peptides consisting of this tat-sequence fused to either the last 13 amino acids of FcαRIwt (aa254-266), designated tat_FcαR, or to the same 13–amino acid sequence with the S>A substitution at position 263 (tat_S>A) (Figure 6A). Furthermore, as a control the 13 amino acids of the wt-peptide were scrambled and linked to the tat-sequence (tat_SCR). As shown in Figure 6B, incubation of Ba/F3_FcαR cells with tat_FcαR resulted in a concentration-dependent inhibition of IgA binding on cytokine stimulation. Incubation with tat_S>A or tat_SCR, however, did not influence the IL-3–induced IgA binding. The activity of tat_S>A was specific because Mac-1–mediated activation of the respiratory burst, which is also sensitive for cytokine-induced inside-out control, was not inhibited by the peptide (results not shown). Using these tat-peptides, it was also possible to investigate the effect of FcαR mutants in primary human eosinophils that are refractory to manipulation by either transfection or viral infection. Similar to the effect on Ba/F3_FcαR cells, binding of IgA beads to cytokine (IL-5)-primed eosinophils was inhibited by preincubation with tat_FcαR, whereas neither the S>A mutation nor the scrambled peptide had any effect (Figure 6C). We thus conclude that in a relevant myeloid cell-type endogenously expressing FcαR, the process of modulation of the receptor functionality via inside-out signaling also involves the intracellular domain, with a critical role for S263.

Overexpression of the intracellular domain of FcαRI by cell permeable tat-peptides inhibits the binding of IgA beads to Ba/F3 cells and human eosinophils.

Overexpression of the intracellular domain was also obtained with tat-peptides (A). Both cytokine-starved Ba/F3_FcαRI cells (B) and purified human eosinophils (C) were incubated with 100 μM of the tat-FcαRI (wt), tat_S>A or a nonrelevant scrambled peptide (tat-SCR). After stimulation for 15 minutes of the Ba/F3 cells with IL-3 (1:1000) and the eosinophils with IL-5 (10−9M), rosette assays were performed, and binding of IgA beads was counted. Results are expressed as rosette index (number of beads/100 cells) and as means ± SE (n = 3).

Overexpression of the intracellular domain of FcαRI by cell permeable tat-peptides inhibits the binding of IgA beads to Ba/F3 cells and human eosinophils.

Overexpression of the intracellular domain was also obtained with tat-peptides (A). Both cytokine-starved Ba/F3_FcαRI cells (B) and purified human eosinophils (C) were incubated with 100 μM of the tat-FcαRI (wt), tat_S>A or a nonrelevant scrambled peptide (tat-SCR). After stimulation for 15 minutes of the Ba/F3 cells with IL-3 (1:1000) and the eosinophils with IL-5 (10−9M), rosette assays were performed, and binding of IgA beads was counted. Results are expressed as rosette index (number of beads/100 cells) and as means ± SE (n = 3).

Discussion

Cytokines, such as interleukins, are important regulators of cellular activation, and it is described for human eosinophils that cytokines are involved in the stimulation of many effector functions,21 such as degranulation, respiratory burst, and activation of adhesion and complement receptors. For the FcRs for IgA (FcαR) and IgG (FcγRII) we have previously shown that binding of Ig-coated targets to FcRs on eosinophils is dependent on cytokine stimulation of the cells.8,9,19 Although the FcRs on eosinophils do not bind monomeric ligand, the functional status of both FcαR and FcγRII for complexed ligand is altered by Th2-derived cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-5. Because this cytokine-mediated modulation is very rapid,8 this switch is not likely to be due to de novo receptor synthesis. Moreover, FACS analysis revealed that levels of receptor expression on the membrane are not altered by cytokine stimulation (M. Bracke, unpublished results, June 1999; Dustin and Springer22).

In this study we used Ba/F3 cells as a model to study the molecular mechanism of cytokine-induced ligand binding to FcαRI (CD89). This murine pre-B cell line, Ba/F3, lacks endogenous CD89 expression and these cells require IL-3 to survive, similar to the requirement for IL-5/IL-3/granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) for human eosinophil survival. In contrast with other cell lines commonly used for FcR studies, such as the murine pre-B IIA1.6 cells, Ba/F3_FcαRI cells interact with IgA-coated targets in a cytokine-dependent fashion. Therefore, Ba/F3 cells provide an excellent system to study FcR regulation.

From the work described in this report it is clear that FcαRI activation requires the intracellular domain of the receptor. We demonstrate that the IgA-binding subunit (CD89) of the FcαR does not simply play a passive role in immunoglobulin binding but is critical for correct regulation of receptor functioning. The concept of inside-out signaling for FcRs is novel and it appears to be comparable to the activation paradigm previously described for integrins. Integrins consist of α and β subunits that are noncovalently associated in the membrane (reviewed in Hynes12). Studies with chimeras containing the cytoplasmic domains of various α and β subunits joined to the transmembrane and extracellular domain of the platelet αIIbβ3-integrin indicated that integrin cytoplasmic domains transduce cell type–specific signals that modulate ligand-binding affinity.23 Thus, integrin cytoplasmic tails are targets for the modulation of integrin affinity. Here we show that, analogous to integrin activation, inside-out signaling of FcαRI also requires the intracellular domain of the receptor to modulate the ligand binding extracellularly. Moreover, expression of deletion or substitution mutants of the cytoplasmic domain of FcαRI revealed that cytokine-dependent modulation requires the C-terminus of the receptor. Deletion of the cytoplasmic tail of FcαRI results in a constitutive binding of ligand, independent of cytokine stimulation. Furthermore, expression of FcαRI in cell lines, such as fibroblasts or cytokine-independent pre-B cells (IIA1.6), results in a receptor that contains a constitutive high activity state.15 In unstimulated eosinophils and cytokine-starved Ba/F3 cells, FcαRI is not activated. This suggests that there are cytoplasmic signaling pathways that constitutively suppress FcαR activation in resting eosinophils. In parallel, for integrins it has been suggested that active cellular mechanisms are involved in inhibition of activation. It has been described that activation of integrins on T cells is often transient, even with continued stimulation, suggesting the existence of an inhibitory signal that overrules the activation signal.24,25 A negative regulation has also been suggested to explain the highly activated state of purified αvβ3-integrin, in contrast with the moderate affinity state of cellular αvβ3.26 Comparable, cytokine-induced activation of immunoglobulin receptors on eosinophils is likely to be caused by inhibition of an active signal, which normally keeps the receptor in a nonfunctional state. This mechanism is important in preventing activation of the cells in circumstances where activation is not required and could even be harmful.

It has been described for β1-integrins that the phosphorylation state of a conserved C-terminal serine is important role for the activation state of the receptor. In cells that undergo mitosis, phosphorylation of this sering residue of β1-integrin leads to inactivation of the integrin resulting in the cells losing adhesion.12,27 28 In this report we show that substitution of a C-terminal serine (S263) affects the activation state of FcαRI. It is difficult to study the phosphorylation state of S263 specifically, because the very short cytoplasmic tail of FcαRI contains several possible phosphorylation sites and tryptic mapping is not possible. In addition, eosinophils are nonproliferative primary cells that could not be labeled with radioactivity. Moreover, it is also not possible to immunoprecipitate endogenous FcαRI from eosinophils. To circumvent problems with eosinophils and to compare the phosphorylation status of FcαRI both in Ba/F3 cells and primary human eosinophils, we used another approach. We used the intracellular domain of FcαRI as a substrate for in vitro kinase assays. As suggested from Figures 1 and 2, the intracellular domain of FcαRI is indeed phosphorylated (Figure 3A,B, middle lanes). In contrast, a substitution mutant of S263 cannot be phosphorylated by lysates from resting cells, suggesting that this residue indeed is phosphorylated in cytokine-starved or resting cells. An interesting possibility is that dephosphorylation of S263 is the first step in activation of the receptor, subsequently followed by other steps leading to a change in conformation and a fully functional receptor. However, addition of cytokines to Ba/F3 cells and eosinophils did not lead to an inhibition of this in vitro kinase assay implying that the level of control is not simply by inhibition of this kinase activity (results not shown). We speculate that proteins associating with the C-terminus of FcαRI are involved in this cytokine-mediated regulation, because overexpression of the intracellular domain of the receptor leads to inappropriate binding of IgA beads. In contrast, a tat-peptide with the S>A mutation (Figure 6B,C) is not competitive, and therefore it is tempting to speculate that activation by cytokines leads to dissociation of interacting proteins or dephosphorylation of S263, subsequently resulting in a functional FcαRI that is able to bind IgA beads.

In addition to (de)phosphorylation of the receptors, interactions with the cytoskeleton are also thought to contribute to integrin activation by stabilizing an active conformation.28 However, there are also reports that interactions of the cytoplasmic domain of integrins with the cytoskeleton can lock integrins in an inactive state.13,18 28 Interestingly, for FcαRI we also provide evidence that the cytoskeleton might be important in maintaining FcαRI activation. Disruption of the cytoskeleton with cytochalasin D treatment inhibits IgA binding to FcαR_S263A, suggesting that although the mutation of S263 into alanine switched the receptor to a state of constitutive high binding to IgA, this mutant receptor also requires the interaction with the cytoskeleton. This concept is corroborated by the finding that the lateral movement (determined by fluorescence recovery after photobleaching) of both wild-type and mutant receptors is similar (results not shown). These findings argue against a hypothesis that priming of FcαRI function is mediated by an increased avidity due to enhanced lateral movement of the receptor. In addition, these data again show the importance of the interaction between cytoskeleton and opsonin and integrin receptors.

It is tempting to speculate that FcαRI, which is phosphorylated in unstimulated cells, will become dephosphorylated on cytokine stimulation and allow interaction with the cytoskeleton, stabilizing the receptor in an activated state. Although further experiments will be necessary to determine the precise nature of this mechanism, we clearly show that the very short intracellular tail of FcαRI plays a crucial role in the IgA-binding switch. Moreover, the phosphorylation state of the C-terminal serine-residue (S263) in this intracellular tail of FcαRI appears to be critical for a proper regulation of the receptor. It appears that FcαRI does not simply bind ligand but that it is critical for cytokine-dependent regulation of IgA binding to the cell.

Cytokine-induced “inside-out” signaling switches FcαRI to an active state and subsequent ligand binding will lead to FcR-γ chain-mediated “outside-in” signaling, resulting in cell activation. In this way, leukocytes can respond very rapidly and efficiently to their environment, a process that requires tight regulation. A greater understanding of cytokine-mediated modulation of FcR functioning on leukocytes will generate insight into the regulation of leukocyte activation and the pathogenesis of inflammation, possibly providing novel therapeutic options, such as inhibiting eosinophil activation in the lungs of allergic asthmatics.

The authors would like to thank Jan van de Linden and Deon Kanters for assistance with the FACS flow cytometer and cell sorting, and Rolf de Groot for constructing GST-FcαRS>A.

Supported by a research grant of the Netherlands Asthma Foundation (NAF 94.44).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Leo Koenderman, Department of Pulmonary Diseases, F02.333, University Hospital Utrecht, Postbus 85500, 3508 GA Utrecht, The Netherlands; e-mail: l.koenderman@hli.azu.nl.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal