Abstract

Under conditions of high shear stress, both hemostasis and thrombosis are initiated by the interaction of the platelet membrane glycoprotein (GP) Ib-IX-V complex with its adhesive ligand, von Willebrand factor (vWF), in the subendothelial matrix or plasma. This interaction involves the A1 domain of vWF and the N-terminal extracellular region of GP Ibα (His-1-Glu-282), and it can also be induced under static conditions by the modulators ristocetin and botrocetin. In this study, a panel of anti-vWF and anti-GP Ibα antibodies—previously characterized for their effects on ristocetin- and botrocetin-dependent vWF–GP Ib-IX-V interactions—was analyzed for their capacity to inhibit either the adhesion of Chinese hamster ovary cells expressing recombinant GP Ibα to surface-associated vWF under hydrodynamic flow or shear-stress–induced platelet aggregation. The combined results suggest that the shear-dependent interactions between vWF and GP Ibα closely correlate with ristocetin- rather than botrocetin-dependent binding under static conditions and that certain anti-vWF monoclonal antibodies are able to selectively inhibit shear-dependent platelet aggregation.

Introduction

The interaction between von Willebrand factor (vWF) and the glycoprotein (GP) Ib-IX-V complex is critical to the initiation of both hemostasis and thrombosis in the arterial vasculature.1 In the normal circulatory system, vWF does not spontaneously interact with the GP Ib-IX-V complex. This interaction occurs in vivo in regions of elevated shear stress when vWF is associated with exposed subendothelial matrix, presumably because of an activating conformational change in the vWF A1 domain.2Alternatively, in the fluid phase, platelets can undergo shear-dependent aggregation initiated by the binding of vWF to the GP Ib-IX-V complex, a process dependent on a conformational change in vWF, the GP Ib-IX-V complex, or both.3

In vitro, the binding of soluble vWF to the GP Ib-IX-V complex under static conditions can also be artificially induced by modulators such as ristocetin and botrocetin that bind the A1 domain of vWF. Ristocetin, a vancomycin-like antibiotic from Nocardia lurida, binds to the proline-rich sequence, Glu-700 to Asp-709, C-terminal to the Cys-509–Cys-695 disulfide bond in the A1 domain,4-7 whereas the botrocetin binding site resides within the A1 domain.8 However, although both ristocetin and botrocetin can induce binding of vWF to the GP Ib-IX-V complex, each modulator induces an interaction that involves distinct regions of both the ligand and the receptor, in addition to the regions common to both modulators. For example, we have recently identified 2 anti-vWF A1 domain antibodies with differential effects on the vWF–GP Ib-IX-V interaction, depending on the method used to induce it. The monoclonal antibody 5D2 inhibits ristocetin- and botrocetin-dependent interactions and asialo-vWF dependent platelet aggregation, whereas CR1 inhibits only the ristocetin-dependent interaction and platelet aggregation induced by asialo-vWF but has no effect on the botrocetin-mediated interaction.7 Similarly, though many anti-GP Ibα antibodies inhibit both ristocetin- and botrocetin-dependent binding of vWF to platelets,9,10 some anti-GP Ibα antibodies selectively inhibit binding induced by only one modulator.11,12 Consistent with these observations, we have recently shown that leucine-rich repeats 2 to 4 in GP Ibα (Leu-60 to Glu-128) are critical for ristocetin- but not botrocetin-dependent binding of vWF,10 whereas a sulfated-tyrosine/negative-charge cluster between Asp-269 and Asp-287 is more important for the botrocetin-dependent binding of vWF.11,13 14

The interaction between vWF and the GP Ib-IX-V complex can also be examined in the absence of modulators under conditions that more closely resemble conditions in vivo. In studies using a parallel-plate flow chamber to generate defined wall shear stresses, both platelets and GP Ib-IX–expressing cells have been demonstrated to adhere to and roll across vWF-containing matrices, in a process similar to the rolling of leukocytes on activated endothelium, albeit at much higher shear stresses.15-17 (GP V is necessary neither in transfected cells18 nor in mouse platelets19,20for the vWF-binding function of the GP Ib-IX-V complex). Platelet rolling was recently also demonstrated to occur in vivo. After superfusing exteriorized mouse mesentery with ferric chloride to induce vascular injury, Denis et al21 were able to observe microscopically the attachment and rolling of fluorescently labeled platelets at sites of vascular damage. In marked contrast to these observations in normal mice, the platelets of mice deficient in vWF neither rolled nor attached effectively to the damaged vessels, directly demonstrating that platelets can roll in vivo using vWF. At much higher shear stresses than present in the normal circulation, platelets can also undergo fluid-phase, shear-dependent aggregation. Studies using cone-and-plate viscometry indicate that this process is initiated by binding of vWF to the GP Ib-IX-V complex, followed by platelet activation and aggregation mediated by binding of vWF to the GP IIb-IIIa complex.22-24 However, though initiated by the vWF–GP Ib-IX-V interaction, platelet aggregation induced by shear appears to require the concomitant binding of vWF by both the GP Ib-IX-V complex and GP IIb-IIIa.23-25

In the current study, we have evaluated a panel of anti-vWF and anti-GP Ibα antibodies, previously characterized for their effects on ristocetin- and botrocetin-dependent vWF–GP Ib-IX-V interactions, for their effects on flow-driven attachment of GP Ib-IX–expressing cells at defined shear stresses using a parallel-plate flow chamber and on shear-induced platelet aggregation by cone-and-plate viscometry. The combined results suggest that the shear-dependent interaction of vWF with GP Ibα closely correlates with ristocetin-dependent, rather than with botrocetin-dependent, binding of vWF to platelets. Further, these studies have identified several anti-vWF antibodies that selectively inhibit shear-dependent platelet aggregation.

Materials and methods

Cell lines, antibodies, and reagents

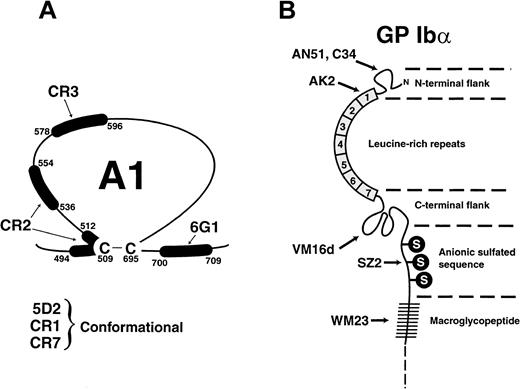

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells stably expressing the GP Ib-IX complex (CHOαβIX cells) or only GP Ibβ and GP IX (CHOβIX cells) were prepared as previously reported.26-28 The anti-vWF A1 domain monoclonal antibodies 5D2, 6G1, CR1, CR2, CR3, and CR7 have been characterized and described elsewhere.7 In addition, 6G1 recognizes the sequence Glu-700 to Asp-709; CR2 binds a discontinuous epitope formed by the sequences Leu-494 to Leu-512 and Phe-536 to Ala-554; and CR3 binds within the sequence Arg-578 to Glu-596. Numbering for the residues is from the N-terminus of the mature, processed vWF monomer (from Ser-764 of the unprocessed polypeptide). The epitopes for 5D2, CR1, and CR7 have not been defined and appear to be conformational. Anti-GP Ibα antibodies used in these studies include AK2, WM23, VM16d, C34, SZ2, and AN51. AK2 recognizes an epitope in the first leucine-rich repeat, Leu-36 to Gln-59,10whereas WM23 binds to an epitope in the macroglycopeptide mucin core.29 VM16d30 was a generous gift from Dr Alexey Mazurov (Moscow, Russia) and C3431 was obtained from the Fifth International Workshop on Leukocyte Antigens (Boston, MA, 1993).9 They recognize GP Ibα epitopes in the C-terminal flanking sequence (Phe-201 to Gly-268) and at the N-terminus (His-1 to Thr-81), respectively.10 SZ232 was purchased from Immunotech (Westbrook, ME) and AN5133 from Dako (Carpinteria, CA). SZ2 binds to the anionic sulfated sequence Asp-269 to Glu-282,10,11 and AN51 binds to the N-terminus of GP Ibα, His-1 to Gln-59.10 The binding sites for the anti-vWF and anti-GPIbα antibodies are shown schematically in Figure1. Purified vWF was obtained from normal human cryoprecipitate by glycine and NaCl precipitation34 35 followed by gel filtration on a Sepharose 4B column (2.5 × 50 cm).

Schema showing the location of the epitopes used in the current study.

(A) Monoclonal anti-vWF antibodies. (B) Anti-GPIbα antibodies.

Schema showing the location of the epitopes used in the current study.

(A) Monoclonal anti-vWF antibodies. (B) Anti-GPIbα antibodies.

Binding of sodium iodide I 125-labeled vWF to platelets

Parallel-plate flow chamber and digital image processing

Purified vWF was immobilized onto 11 × 22 mm2glass coverslips by incubating the coverslips with 200 μL PBS containing 50 μg/mL vWF for 45 minutes at room temperature. Unbound vWF was removed by washing the coverslips with saline. The coverslip was then incorporated into a parallel-plate flow chamber assembly where it formed the floor of the chamber. The flow chamber was mounted onto an inverted-stage microscope (DIAPHOT-TMD; Nikon, Garden City, NY) equipped with a silicon-intensified target video camera (model C2400; Hammatus, Waltman, MA) connected to a videocassette recorder. To induce cell rolling on immobilized vWF, a cell suspension (100 000 cells/mL) was perfused through the chamber at a flow rate calculated to generate a fluid shear stress of 10 dynes/cm2. Cell rolling in a single-view field was recorded in real time for 3 minutes, and the video data were then analyzed off-line using imaging software (IC-300 Modular Image Processing Workstation; Inovision, Durham, NC) to calculate the rolling velocities of 50 or more cells per run. Each experiment was performed at least 3 times. Cells considered to be rolling were those observed to be moving in the direction of fluid flow while maintaining constant contact with the vWF matrix.36The distance a single cell rolled during a defined period determined its rolling velocity; the mean velocity was calculated by averaging the velocities of all the rolling cells in each experiment. To test the blocking effects of antibodies, vWF-coated coverslips were incubated with anti-vWF antibody (final concentration, 25 μg/mL) for 15 minutes, or cells were incubated with anti-GP Ibα antibody (final concentration, 25 μg/mL) for 15 minutes.

Shear-induced platelet aggregation

Human blood was collected from any of 8 healthy donors who constituted our donor pool. Blood was only drawn from those who had been medication-free for the previous 2 weeks. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was obtained from 50 mL anticoagulated blood (trisodium citrate at a final concentration of 0.32%) by centrifuging the whole blood at 140g for 15 minutes at 24°C. To determine the effects of monoclonal anti-vWF and anti-GP Ibα antibodies on shear-induced platelet aggregation, 475 μL PRP was incubated with either 25 μL Tris-buffered saline (positive control) or 25 μL antibody (final concentration, 25 μg/mL) for 5 minutes at room temperature. The PRP was then loaded onto a cone-and-plate viscometer (Ferranti-Shirley, Dayton, OH) and sheared for 1 minute at 40, 90, or 120 dynes/cm2 with a one-third degree cone. Twenty μL sheared PRP was collected and fixed in an isotonic solution containing 0.2% glutaraldehyde. The extent of platelet aggregation was determined by particle counting in a Coulter counter (Coulter Electronics, Miami, FL). As platelet aggregates form, each aggregate is counted as one particle, whether it contains 2 or 30 platelets. Thus, a decrease in the particle count signals an increase in aggregation. Unsheared PRP was used as negative control throughout the experiments. The particle counts obtained through the Coulter counter were normalized to reflect percentage of maximal aggregation, with the positive control as 100% and nonsheared PRP as 0%.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using the Student t test.P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

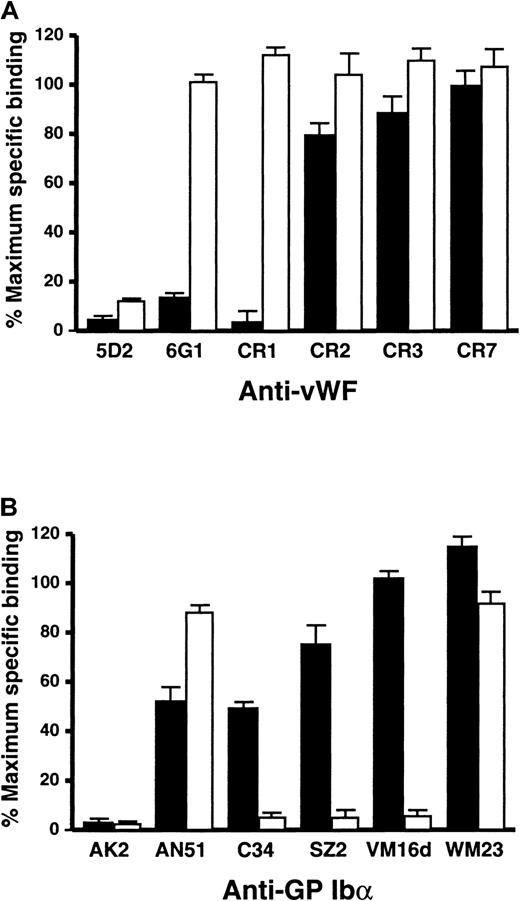

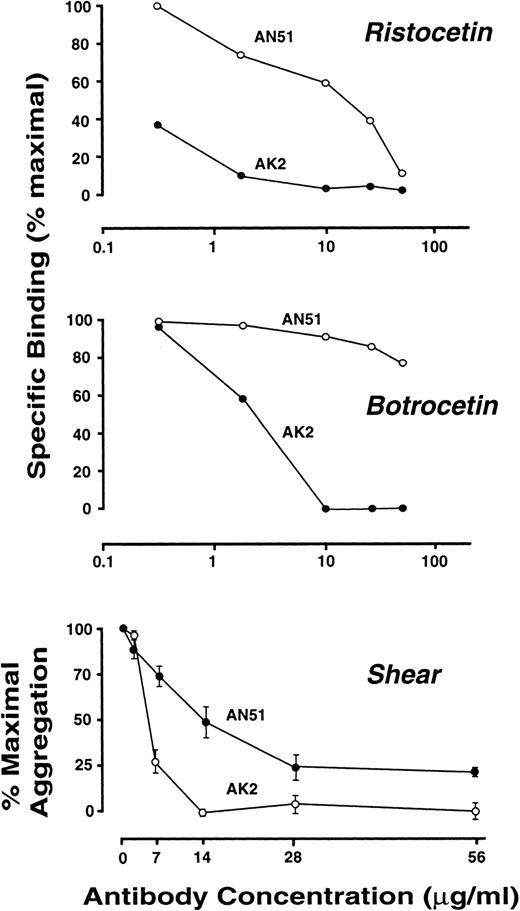

Functional analyses of murine monoclonal antibodies against the vWF A1 domain or the N-terminal 282 residues of GP Ibα have been important for defining the interaction of vWF with the GP Ib-IX-V complex. Both anti-vWF (Figure 2A) and anti-GP Ibα (Figure 2B) antibodies have previously been shown to differentially inhibit vWF binding to platelets under static conditions, depending on whether the interaction was induced by ristocetin or botrocetin. The anti-vWF antibody, 5D2, strongly inhibited both ristocetin- and botrocetin-dependent binding, whereas 6G1 and CR1 preferentially inhibited binding in the presence of ristocetin; CR2, CR3, and CR7 were not significantly inhibitory regardless of the modulator (Figure 2A). Similarly, the anti-GP Ibα antibody AK2 was equally effective at inhibiting ristocetin- and botrocetin-dependent vWF binding, whereas AN51 preferentially inhibited ristocetin-dependent binding, and C34, SZ2, and VM16d were markedly more inhibitory in the presence of botrocetin (Figure 2B). Because AN51 was the only antibody used that was selective for inhibiting ristocetin- but not botrocetin-dependent binding of vWF, we examined the effect of AN51 on a wide range of antibody concentrations. However, though high concentrations of AN51 (50 μg/mL) could inhibit ristocetin-dependent vWF binding by more than 80%, the effect on botrocetin-dependent binding of vWF, even at this concentration, was minimal (Figure 3). In contrast, AK2 maximally inhibited both interactions at a concentration of 10 μg/mL (Figure 3). The control antibody WM23 did not inhibit vWF binding under any circumstances, recognizing an epitope in the macroglycopeptide region of GP Ibα, downstream of Arg-293.29

Effect of anti-vWF and anti-GP Ibα antibodies on vWF binding to platelets.

(A) Effect of the anti-vWF monoclonal antibodies (10 μg/mL, final concentration) on specific binding of 125I-labeled vWF (1 μg/mL) to washed platelets (5 × 107) in the presence of either 1 mg/mL (final concentration) ristocetin (▪) or 2.5 μg/mL botrocetin (■).7 The labeled vWF was incubated with the cells for 30 minutes at 22°C, after pre-incubating the platelets with the antibody for 5 minutes. Maximum binding was measured in the absence of antibody, and nonspecific binding was determined in the absence of modulator, in parallel assays. Data are the mean of triplicate determinations (± SEM). (B) Effect of anti-GP Ibα monoclonal antibodies (10 μg/mL, final concentration) on specific binding of125I-labeled vWF to washed platelets in the presence of either ristocetin (▪) or botrocetin (■) using the same assay as described in the legend to panel A.9 10

Effect of anti-vWF and anti-GP Ibα antibodies on vWF binding to platelets.

(A) Effect of the anti-vWF monoclonal antibodies (10 μg/mL, final concentration) on specific binding of 125I-labeled vWF (1 μg/mL) to washed platelets (5 × 107) in the presence of either 1 mg/mL (final concentration) ristocetin (▪) or 2.5 μg/mL botrocetin (■).7 The labeled vWF was incubated with the cells for 30 minutes at 22°C, after pre-incubating the platelets with the antibody for 5 minutes. Maximum binding was measured in the absence of antibody, and nonspecific binding was determined in the absence of modulator, in parallel assays. Data are the mean of triplicate determinations (± SEM). (B) Effect of anti-GP Ibα monoclonal antibodies (10 μg/mL, final concentration) on specific binding of125I-labeled vWF to washed platelets in the presence of either ristocetin (▪) or botrocetin (■) using the same assay as described in the legend to panel A.9 10

Effect of increasing concentrations of AN51 and AK2 on ristocetin- and botrocetin-dependent binding of vWF to platelets and on shear-dependent platelet aggregation.

Effect of increasing concentrations of AN51 and AK2 on ristocetin- and botrocetin-dependent binding of vWF to platelets and on shear-dependent platelet aggregation.

vWF can also bind the GP Ib-IX-V complex as a shear-dependent interaction without the requirement for either ristocetin or botrocetin. We therefore used this panel of antibodies to compare the shear-dependent vWF–GP Ib-IX-V interaction to the interactions induced by either ristocetin or botrocetin.

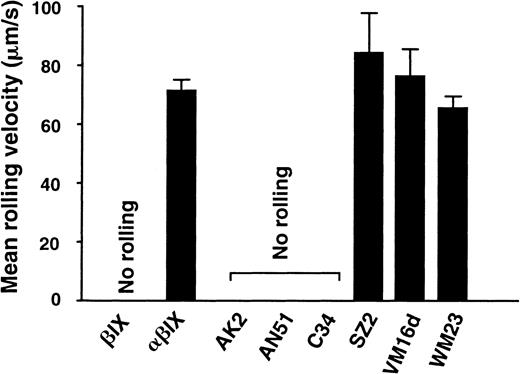

Effect of anti-vWF and anti-GP Ibα monoclonal antibodies on GP Ibα-dependent adhesion to vWF under flow

In the absence of ristocetin or botrocetin, CHOαβIX cells expressing GP Ibα (and GP Ibβ and GP IX to facilitate GP Ibα expression) are able to adhere to and roll along vWF-coated surfaces under flow at shear stresses up to 40 dynes/cm.16 In contrast to GP Ib-IX–expressing cells, CHOβIX cells, which lack GP Ibα, fail to adhere to the surface (Figure4). The anti-GP Ibα monoclonal antibodies AK2, AN51, and C34 completely abolished CHOαβIX cell adhesion, whereas SZ2, VM16d, and WM23 did not significantly affect either adhesion or rolling velocity (Figure 4). In separate experiments, the vWF-coated surface was pretreated with anti-vWF monoclonal antibodies. Two antibodies, 5D2 and CR1, completely blocked the adhesion of GP Ibα-expressing cells, whereas 6G1 had only a marginal effect, comparable to the effect of an irrelevant control mouse IgG (Figure 5). Thus, with the exception of 6G1, which inhibits ristocetin-dependent binding of vWF to platelets because it competes for the ristocetin-binding site on vWF,7 the capacity of the anti-GP Ibα and anti-vWF antibodies to inhibit GP Ibα-dependent adhesion under flow correlated with their capacity to inhibit ristocetin-dependent, but not botrocetin-dependent, vWF binding to the receptor. The anti-vWF antibodies CR2, CR3, and CR7 were not tested in this system because, unlike the other anti-vWF antibodies tested, these antibodies do not bind to immobilized vWF.7 All the antibodies, however, bind native vWF spotted onto nitrocellulose and recognized by Western blot a 39/34-kd proteolytic fragment of vWF (Leu-478–Gly-718) encompassing the A1 domain.7

Effect of anti-GP Ibα monoclonal antibodies on the adhesion of GP Ib-IX–expressing CHO cells to vWF under flow.

Mean velocities are shown for CHOαβIX cells rolling over a glass surface coated with 50 μg/mL vWF (this concentration saturates the vWF binding sites on the glass coverslip) after the application of a shear stress of 10 dynes/cm2. CHOβIX cells, lacking GP Ibα, did not adhere to the surface. Where indicated, CHOαβIX cells were pretreated with monoclonal antibody at 25 μg/mL for 15 minutes. This concentration was well above the saturating concentration for each of these antibodies. Results are the means of analysis of 300 to 700 cells from 3 to 5 experimental runs.

Effect of anti-GP Ibα monoclonal antibodies on the adhesion of GP Ib-IX–expressing CHO cells to vWF under flow.

Mean velocities are shown for CHOαβIX cells rolling over a glass surface coated with 50 μg/mL vWF (this concentration saturates the vWF binding sites on the glass coverslip) after the application of a shear stress of 10 dynes/cm2. CHOβIX cells, lacking GP Ibα, did not adhere to the surface. Where indicated, CHOαβIX cells were pretreated with monoclonal antibody at 25 μg/mL for 15 minutes. This concentration was well above the saturating concentration for each of these antibodies. Results are the means of analysis of 300 to 700 cells from 3 to 5 experimental runs.

Effect of anti-vWF monoclonal antibodies on binding of GP Ibα-expressing CHO cells to vWF under flow.

The experiment was conducted as in Figure 4 except that the vWF-coated surfaces, rather than the cells, were pretreated with monoclonal antibodies (25 μg/mL, 15 minutes). Results are the means of analysis of 300 to 700 cells from 3 to 5 experimental runs.

Effect of anti-vWF monoclonal antibodies on binding of GP Ibα-expressing CHO cells to vWF under flow.

The experiment was conducted as in Figure 4 except that the vWF-coated surfaces, rather than the cells, were pretreated with monoclonal antibodies (25 μg/mL, 15 minutes). Results are the means of analysis of 300 to 700 cells from 3 to 5 experimental runs.

Effect of anti-vWF and anti-GP Ibα monoclonal antibodies on shear-induced platelet aggregation

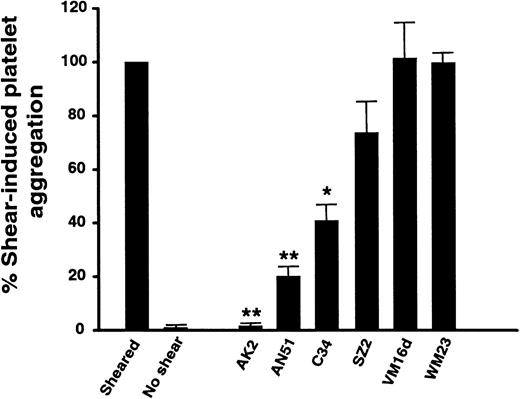

At a shear stress of 90 dynes/cm2, platelet aggregation was strongly inhibited by the anti-GP Ibα antibody, AK2, and, to a lesser extent, by AN51 and C34, whereas there was no significant inhibition by SZ2, VM16d, or the control antibody WM23 (Figure 6). Inhibition was dose dependent, with maximal inhibition at concentrations above 20 μg/mL (see Figure 3). AK2, AN51, and C34 inhibited not only shear-induced platelet aggregation but also ristocetin-dependent vWF binding to GP Ibα by 50% or more (Figure 2B) and GP Ibα-dependent rolling of CHO cells on immobilized vWF (Figure 4). However, when anti-vWF monoclonal antibodies were tested under the same conditions, there were marked differences in the correlation between rolling and shear. 5D2, 6G1, CR1, and CR2 strongly inhibited shear-induced platelet aggregation at shear stresses of 40, 90, and 120 dynes/cm2; CR3 and CR7 did not inhibit at any shear stress (Figure7). The degree of inhibition by 5D2 and 6G1 was essentially independent of the level of shear stress, whereas CR1 and CR2 showed less, but still significant, inhibition with increasing shear stress, up to 120 dynes/cm2 (Figure 7). Of the antibodies that inhibited shear-induced platelet aggregation, 5D2 and CR1 also inhibited cell adhesion to vWF under flow- and ristocetin-dependent vWF binding to GP Ibα, 6G1 inhibited ristocetin-dependent binding but not adhesion, and CR2 only inhibited shear-induced platelet aggregation.

Effect of anti-GP Ibα monoclonal antibodies on shear-induced platelet aggregation.

Shear-induced aggregation in platelet-rich plasma was measured in the absence of antibodies or after pre-incubating the sample with 25 μg/mL antibody (a concentration that far exceeds the saturating concentration for each antibody) for 5 minutes at ambient temperature before the application at 90 dynes/cm2 of shear stress in a cone-and-plate viscometer. Results are the means of 4 to 8 experiments performed using different donors. *P < .05; **P < .001.

Effect of anti-GP Ibα monoclonal antibodies on shear-induced platelet aggregation.

Shear-induced aggregation in platelet-rich plasma was measured in the absence of antibodies or after pre-incubating the sample with 25 μg/mL antibody (a concentration that far exceeds the saturating concentration for each antibody) for 5 minutes at ambient temperature before the application at 90 dynes/cm2 of shear stress in a cone-and-plate viscometer. Results are the means of 4 to 8 experiments performed using different donors. *P < .05; **P < .001.

Effect of anti-vWF monoclonal antibodies on shear-induced platelet aggregation.

Shear-induced aggregation in platelet-rich plasma was measured in the absence of antibodies or after pre-incubating the sample with 25 μg/mL antibody (final concentration) for 5 minutes at ambient temperature before the application of shear at 40, 90, or 120 dynes/cm2. Results are the means of 4 to 8 experiments performed using different donors. *P < .05; **P < .001.

Effect of anti-vWF monoclonal antibodies on shear-induced platelet aggregation.

Shear-induced aggregation in platelet-rich plasma was measured in the absence of antibodies or after pre-incubating the sample with 25 μg/mL antibody (final concentration) for 5 minutes at ambient temperature before the application of shear at 40, 90, or 120 dynes/cm2. Results are the means of 4 to 8 experiments performed using different donors. *P < .05; **P < .001.

Discussion

It has been unclear whether it is the ristocetin- or the botrocetin-induced interaction between vWF and the GP Ib-IX-V complex that more closely approximates the shear-dependent interactions between this ligand-receptor pair. In this study, we addressed this question by examining the effect on shear-dependent interactions of a group of monoclonal antibodies against both vWF and GP Ibα with differential effects on the ristocetin- or botrocetin-dependent interactions. Our results indicate that the vWF–GP Ibα interaction induced by shear stress more closely resembles the interaction induced by ristocetin than that induced by botrocetin. AK2 and C34, anti-GP Ibα monoclonal antibodies that inhibit both ristocetin- and botrocetin-dependent binding of vWF, and AN51, which selectively inhibits ristocetin-dependent binding, also inhibited both the rolling of CHOαβIX cells on immobilized vWF and shear-dependent platelet aggregation. In contrast, VM16d and SZ2, antibodies that selectively inhibit botrocetin-dependent binding of vWF, had no effect on these shear-dependent interactions. Similarly, the vWF antibodies 5D2 and CR1 inhibited ristocetin-dependent binding of vWF to platelets, asialo-vWF–induced platelet aggregation, rolling of CHOαβIX cells on immobilized vWF, and shear-dependent platelet aggregation. Of these 2 antibodies, only 5D2 also inhibited botrocetin-dependent binding of vWF to platelets.7 The exception to this correlation between the capacity of antibodies to inhibit both ristocetin- and shear-dependent vWF binding to receptor was the anti-vWF antibody, 6G1, which only inhibited ristocetin-dependent binding of vWF and shear-dependent platelet aggregation but not rolling of CHOαβIX cells on immobilized vWF. However, our previous studies suggest that the inhibition of ristocetin-dependent binding of vWF is due to interference of the antibody with the ristocetin-binding site on vWF.7

That shear- and ristocetin-dependent interactions of vWF with the GP Ib-IX-V complex are similar is supported by our recent studies. One study involved analysis of human-canine chimeras of GP Ibα expressed in CHO cells as components of GP Ib-IX complexes.10 When human GP Ibα was made progressively canine from the N-terminus, the ability of the CHOαβIX chimeras to bind human vWF in the presence of ristocetin and to roll on immobilized vWF was lost when the second leucine-rich repeat was converted to canine sequence. Similarly, when recombinant GP Ibα that was canine to position 282 was rehumanized from the N-terminus, ristocetin-dependent vWF binding and rolling on immobilized vWF were both regained when the sequence was made human to the end of the fourth leucine-rich repeat. In contrast, botrocetin did not discriminate between human and canine GP Ibα sequences, inducing the binding of human vWF not only to human GP Ibα, but also to canine GP Ibα and to each of the chimeras.10 In complementary studies, anti-GP Ibα antibodies were also mapped using this series of canine-human chimeras.10 Notably, AN51, AK2, and C34, which inhibit both shear- and ristocetin-dependent interaction of vWF with the GP Ib-IX-V complex, map to the N-terminal 81 residues of GP Ibα. VM16d and SZ2, on the other hand, map to the C-terminal flank (Phe-201–Gly-268) and the adjacent anionic–sulfated sequence, respectively.

Also indicating that ristocetin mimics shear in inducing vWF binding to GP Ibα were our studies of GP Ibα mutants carrying mutations of conserved Asn residues. We found that mutation of Asn-41 to either Lys or Ser produced GP Ibα polypeptides with defective adhesion to immobilized vWF under flow, a defect that was also reflected in the ristocetin-induced vWF binding assay.37 Botrocetin-induced vWF binding, on the other hand, was not different between cells expressing the different mutants, even those completely defective in adhesion. The correlation between ristocetin and shear therefore includes the effects of both mutations and blocking antibodies.

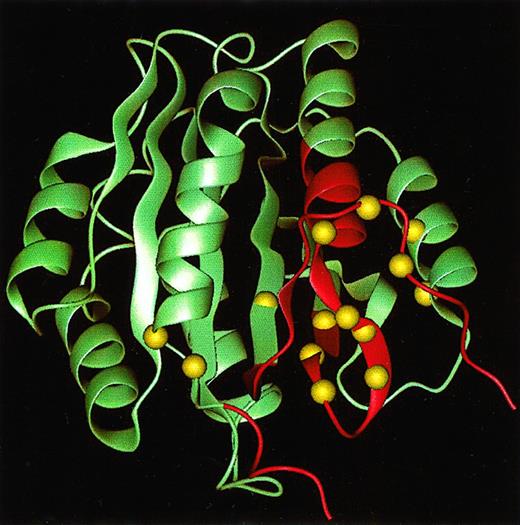

Thus, with respect to GP Ibα, we have found no instance in which a mutation or an antibody that produced defective shear-induced interactions with vWF did not also yield defective ristocetin-induced vWF binding. The same is not true of anti-vWF antibodies. In the current study, we identified 2 monoclonal antibodies, 6G1 and CR2, that selectively inhibited shear-induced platelet aggregation. Both antibodies recognize linear sequences proximal to the Cys-509–Cys-695 disulfide bond in the vWF A1 domain; 6G1 binds within the sequence Glu-700 to Asp-709, and CR2 recognizes an epitope formed by the sequences Leu-494 to Leu-512 and Phe-536 to Ala-554 (Figure8).7 However, 6G1 had no effect on adhesion and rolling of CHOαβIX cells on immobilized vWF. Neither antibody affected asialo–vWF-induced platelet aggregation7 or botrocetin-induced binding of vWF to platelets. Although 6G1 inhibited the ristocetin-dependent vWF interaction, it did so by interfering with the ristocetin modulator site (see above).7

Epitopes for anti-vWF monoclonal antibodies.

Structure of the vWF A1 domain based on the radiograph crystal coordinates39 with highlighted sequences representing epitopes for the anti-vWF antibodies 6G1 and CR2.7 The Cα locations of gain-of-function point mutations in type 2B von Willebrand disease are shown as van der Waal spheres.38The figure was generated using the Quanta package (MSI, San Diego, CA).

Epitopes for anti-vWF monoclonal antibodies.

Structure of the vWF A1 domain based on the radiograph crystal coordinates39 with highlighted sequences representing epitopes for the anti-vWF antibodies 6G1 and CR2.7 The Cα locations of gain-of-function point mutations in type 2B von Willebrand disease are shown as van der Waal spheres.38The figure was generated using the Quanta package (MSI, San Diego, CA).

There are 2 possible explanations why 6G1 and CR2 might selectively inhibit shear-dependent platelet aggregation. One is that they interfere with a region of the vWF A1 domain involved in binding the GP Ib-IX-V complex only in the presence of fluid-phase shear forces. The other is that they prevent a conformational change in the A1 domain required for the fluid-phase, shear-dependent activation of vWF. Although it is not possible to distinguish between these 2 potential inhibitory mechanisms, it is of interest, with respect to the latter possibility, that 6G1 and CR2 bind to the region of the vWF A1 domain that includes most type 2B von Willebrand disease gain-of-function mutations38 (Figure 8).

In summary, a comparison of the functional effects of anti-vWF and anti-GP Ibα monoclonal antibodies on the interaction of vWF and GP Ibα induced under static conditions or conditions of high shear or flow suggests that shear-dependent binding of vWF to GP Ibα closely correlates with ristocetin-dependent binding. Moreover, the finding that specific anti-vWF antibodies may selectively inhibit shear-dependent platelet aggregation raises the intriguing possibility of inhibiting shear-induced thrombosis without affecting hemostasis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Susan Krause and Andrea Aprico for their excellent technical assistance.

Supported by an American Heart Association/Texas Affiliate grant-in-aid; National Institutes of Health grants HL18672, NS23327, and HL46416; and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Michael C. Berndt, Baker Medical Research Institute, PO Box 6492, St Kilda Road Central, Melbourne, Victoria, 8008 Australia; e-mail: michael.berndt@baker.edu.au or Jin-Fei Dong, Baylor College of Medicine, BCM286, N1319, One Baylor Plaza, Houston, TX 77030; e-mail: jfdong@bcm.tmc.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal