Abstract

The effect of high-dose chemotherapy and autografting on bone turnover in myeloma is not known. A study of 32 myeloma patients undergoing blood or marrow transplant (BMT), conditioned with high-dose melphalan, was done. Bone resorption was assessed by urinary free pyridinoline (fPyr) and deoxypyridinoline (fDPyr), expressed as a ratio of the urinary creatinine concentration. Bone formation was assessed by serum concentration of procollagen 1 extension peptide (P1CP) and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BSAP). Eighteen cases had normal fPyr and fDPyr at transplant, and in all but one of these cases the level remained normal throughout subsequent follow-up. In contrast, in 14 cases urinary fPyr and fDPyr levels were increased at transplant. In these cases, both fPyr and fDPyr fell to normal levels over the next few months (P = .0009 and .0019, respectively). fPyr and fDPyr levels at transplant and their trends post-BMT were unrelated to the use of pre-BMT or post-BMT bisphosphonate or post-BMT interferon. Nine cases had elevated P1CP or BSAP at transplant, which rapidly normalized. In most patients there was an increase in P1CP and/or BSAP several months post-transplant. In conclusion, increased osteoclast activity may be present even in apparent plateau phase of myeloma. High-dose chemotherapy with autografting may normalize abnormal bone resorption, although the effect may take several weeks to emerge and may be paralleled by increased osteoblast activity. The findings provide biochemical evidence that autografting may help normalize the abnormal bone turnover characteristic of myeloma.

Introduction

Bone lesions are an important cause of morbidity in myeloma. The typical lytic lesions arise because of a local imbalance between bone resorption and formation. This imbalance may be due to both a low activity of bone-forming cells and an excess of osteoclast-mediated bone resorption.1-4 Excessive bone resorption may be present even in cases with early disease and may be a poor prognostic sign.2 Factors produced locally by myeloma cells are responsible for osteoclast activation, especially interleukin-6 and interleukin-1β.5-8 By the time that a lytic lesion is evident on a conventional bone radiograph, more than 50% of bone loss has occurred. Magnetic resonance imaging reveals abnormal appearances in 50% of patients with apparently normal skeletal surveys, using plain radiographs.9 Significant bone destruction may, therefore, have taken place in the presence of normal plain radiographs.10 Conventional chemotherapy may slow down or halt the progression of bony disease and may also relieve the associated pain, but even chemotherapy responders may have progression of skeletal disease.11 Bisphosphonates inhibit osteoclast-mediated bone resorption and may improve the skeletal prognosis in myeloma, in addition to their effects on myeloma-associated hypercalcemia.12-14

A recent report15 suggests that autologous blood/marrow stem cell transplantation (ABMT) in myeloma may delay disease progression and prolong survival, and further randomized studies addressing the role of ABMT are in progress. However, the effect of transplantation on the outcome of bony disease in myeloma has not been well studied. In a retrospective study by the European Blood and Marrow Transplant Group,16 12 of 76 patients showed radiological improvement of bone lesions following allografting. Lytic lesions assessed by plain radiographs may progress following ABMT, without evidence of hematological or immunological progression.17

Type I collagen constitutes 90% of bone protein, and the resorption of bone by osteoclasts results in the production of collagen peptides, cross-linked peptides, cross-linking molecules, and amino acids. Hydroxyproline released from the breakdown of collagen can be measured in the urine as an estimate of osteoclast activity. However, this molecule lacks specificity for bone, is present in the diet, may be reused in new collagen formation, and is secreted during complement activation.

Newer assays have been developed that are more specific for Type I collagen breakdown and formation and that accurately reflect osteoclast or osteoblast function. Pyridinoline and deoxypyridinoline are mature covalent crosslinks of collagen that are excreted in urine, and their measurement in urine correlates well with bone collagen resorption. Deoxypyridinoline measurement is believed to be most specific for Type I collagen.18 Amino and carboxy terminal propeptides of Type I collagen (P1NP, P1CP) can be measured in plasma as indices of osteoblast collagen formation.19,20Simultaneous measurements of these biochemical markers of bone turnover can provide information on the likelihood of bone loss or accumulation and on the coupling of bone cell activity.21 The use of biochemical markers of bone turnover has been reported in untreated myeloma and monoclonal gammopathies of undetermined significance22 and in a cross-sectional study of recipients of allogeneic bone marrow transplant (BMT) for diseases other than myeloma.23

To investigate the effect of high-dose chemotherapy on bone turnover in myeloma, the present study was designed to serially study markers of bone turnover following BMT. Such a study, to our knowledge, has not been previously reported.

Patients and methods

Study population

Ethical approval was granted by the Liverpool Research Ethics Committee, and all patients gave written informed consent prior to entry. Thirty-four consecutive myeloma patients were enrolled in the study, although 2 were later excluded, one because of technical problems with the pre-BMT samples, and one because of the post-BMT diagnosis of celiac disease, which might have confounded the interpretation of bone mineral turnover. Thirty-two patients undergoing autografting were therefore available for analysis. Their median age was 54 years (range 40-68). Pre-BMT clinical details are given in Table1. All but 4 cases had secretory disease at original diagnosis, and all but 3 were transplanted in first plateau or first remission. Eight cases had no evidence of bony disease on skeletal survey at original diagnosis. Seventeen cases had received pretransplant bisphosphonate.

Characteristics of the study population

| Case . | Age (yr)/sex . | Bony disease at diagnosis . | Serology . | Status at BMT . | Bisphosphonate pre-BMT . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 54/M | Yes | Urinary kappa light chains | 1st CR | Yes |

| 2 | 52/F | Yes | Serum IgA lambda | 1st plateau | No |

| 3 | 63/F | Yes | Urinary lambda light chains | 1st plateau | Yes |

| 4 | 57/M | Yes | Serum IgA kappa | 1st plateau | No |

| 5 | 40/F | Yes | Serum IgG kappa | 1st plateau | No |

| 6 | 48/M | Yes | Serum IgA kappa (also small IgG) | 1st CR | Yes |

| 7 | 58/F | Yes | Serum IgA kappa | 1st CR | Yes |

| 8 | 68/F | Yes | Serum IgG lambda | 1st plateau | Yes |

| 9 | 44/M | No | Serum IgG kappa | 2nd response | No |

| 10 | 58/F | Yes | Urinary lambda light chains | 1st CR | Yes |

| 11 | 61/F | Yes | Nonsecretory | 1st CR | No |

| 12 | 52/F | Yes | Serum IgG kappa | 1st plateau | Yes |

| 13 | 60/F | Yes | Serum IgG lambda | 1st plateau | Yes |

| 14 | 40/M | Yes | Nonsecretory | 1st CR | No |

| 15 | 63/F | Yes | Nonsecretory | 1st CR | No |

| 16 | 64/M | Yes | Serum IgG kappa | 1st plateau | Yes |

| 17 | 59/M | Yes | Nonsecretory | 1st CR | Yes |

| 18 | 53/M | No | Urinary lambda light chains | 2nd response | No |

| 19 | 44/M | No | Serum IgG lambda | 1st plateau | No |

| 20 | 50/M | No | Serum IgG kappa | 1st plateau | Yes |

| 21 | 51/M | Yes | Urinary kappa light chains | 1st plateau | Yes |

| 22 | 56/M | No | Serum IgA lambda | 1st CR | No |

| 23 | 61/M | No | Serum IgA kappa | 1st CR | No |

| 24 | 52/M | Yes | Serum IgG | 1st plateau | No |

| 25 | 52/F | No | Serum IgG lambda | 1st plateau | No |

| 26 | 53/F | Yes | Urinary lambda light chains | 1st CR | No |

| 27 | 52/M | Yes | Serum IgG kappa | 1st plateau | Yes |

| 28 | 41/M | Yes | Serum IgG kappa | 1st plateau | No |

| 29 | 55/M | Yes | Serum IgA kappa | 2nd CR | Yes |

| 30 | 51/F | Yes | Serum IgG kappa | 1st CR | Yes |

| 31 | 61/M | Yes | Serum IgA lambda | 1st plateau | Yes |

| 32 | 46/M | No | Serum IgG lambda | 1st CR | Yes |

| Case . | Age (yr)/sex . | Bony disease at diagnosis . | Serology . | Status at BMT . | Bisphosphonate pre-BMT . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 54/M | Yes | Urinary kappa light chains | 1st CR | Yes |

| 2 | 52/F | Yes | Serum IgA lambda | 1st plateau | No |

| 3 | 63/F | Yes | Urinary lambda light chains | 1st plateau | Yes |

| 4 | 57/M | Yes | Serum IgA kappa | 1st plateau | No |

| 5 | 40/F | Yes | Serum IgG kappa | 1st plateau | No |

| 6 | 48/M | Yes | Serum IgA kappa (also small IgG) | 1st CR | Yes |

| 7 | 58/F | Yes | Serum IgA kappa | 1st CR | Yes |

| 8 | 68/F | Yes | Serum IgG lambda | 1st plateau | Yes |

| 9 | 44/M | No | Serum IgG kappa | 2nd response | No |

| 10 | 58/F | Yes | Urinary lambda light chains | 1st CR | Yes |

| 11 | 61/F | Yes | Nonsecretory | 1st CR | No |

| 12 | 52/F | Yes | Serum IgG kappa | 1st plateau | Yes |

| 13 | 60/F | Yes | Serum IgG lambda | 1st plateau | Yes |

| 14 | 40/M | Yes | Nonsecretory | 1st CR | No |

| 15 | 63/F | Yes | Nonsecretory | 1st CR | No |

| 16 | 64/M | Yes | Serum IgG kappa | 1st plateau | Yes |

| 17 | 59/M | Yes | Nonsecretory | 1st CR | Yes |

| 18 | 53/M | No | Urinary lambda light chains | 2nd response | No |

| 19 | 44/M | No | Serum IgG lambda | 1st plateau | No |

| 20 | 50/M | No | Serum IgG kappa | 1st plateau | Yes |

| 21 | 51/M | Yes | Urinary kappa light chains | 1st plateau | Yes |

| 22 | 56/M | No | Serum IgA lambda | 1st CR | No |

| 23 | 61/M | No | Serum IgA kappa | 1st CR | No |

| 24 | 52/M | Yes | Serum IgG | 1st plateau | No |

| 25 | 52/F | No | Serum IgG lambda | 1st plateau | No |

| 26 | 53/F | Yes | Urinary lambda light chains | 1st CR | No |

| 27 | 52/M | Yes | Serum IgG kappa | 1st plateau | Yes |

| 28 | 41/M | Yes | Serum IgG kappa | 1st plateau | No |

| 29 | 55/M | Yes | Serum IgA kappa | 2nd CR | Yes |

| 30 | 51/F | Yes | Serum IgG kappa | 1st CR | Yes |

| 31 | 61/M | Yes | Serum IgA lambda | 1st plateau | Yes |

| 32 | 46/M | No | Serum IgG lambda | 1st CR | Yes |

BMT, bone marrow transplant; CR, complete response; Ig, immunoglobulin.

All patients underwent peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) harvesting following mobilization with cyclophosphamide 1.5 gm/m2 and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). At least 3 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg recipient weight were obtained from 17 cases, and CD34+ cells were positively selected from these cases, using an Isolex 300 (Baxter, Newbury, Berkshire, UK), in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Five cases (numbers 11, 15, 25, 26, and 31) were transplanted with autologous marrow as well as PBSC, because of a poor yield of the latter; the remaining cases received PBSC alone. Conditioning was with melphalan on day −1 at a dose of 200 mg/m2 in all except 3 cases, who received 70 mg/m2 because of either general frailty (cases 8 and 11) or impaired renal function (case 3). This patient had a serum creatinine level consistently less than 300 μmol/L (upper limit of reference range = 120 μmol/L) and a parathormone level within the reference range until day +302 post-BMT, beyond which she was removed from the study because of overt renal deterioration. All patients received methylprednisolone 1.5 gm daily from day 0 (the day of PBSC/marrow reinfusion) to +3 inclusive; no patient received any corticosteroids subsequent to this.

The post-transplant course is given in Table2. For most of the duration of the study, post-transplant G-CSF was only given routinely to recipients of marrow, commencing on day +7 at a dose of 5 μg/kg per day until the neutrophil count reached 1 × 109/L. Toward the end of the study, this policy was extended to PBSC recipients, and a further case (number 12) received G-CSF at the same dose from days 10-29 because of slow engraftment. On recovery from BMT, patients were discharged to the care of their local physician, with the recommendation to commence maintenance interferon at a dose of 3 megaunits three times weekly as soon as the neutrophil and platelet counts were adequate and to commence/resume either pamidronate 90 mg intravenously every 4 weeks or clodronate 800 mg twice daily orally, depending on local hospital policy. Details are given in Table 2.

Post-BMT outcome

| Case . | CD34 selected . | Post-BMT . | Outcome . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G-CSF . | IFN . | Bisphosphonate . | |||

| 1 | Yes | No | No | From day 358 | Well day 1363 |

| 2 | No | No | No | No | Progression day 501 |

| 3 | No | No | No | No | Renal failure day 353; progression day 491 |

| 4 | Yes | No | From day 115 | No | Progression day 640 |

| 5 | Yes | No | From day 814 | From day 546 | Well day 1206 |

| 6 | No | No | Days 181-467 | From day 181 | Progression day 658 |

| 7 | Yes | No | Days 106-730 | From day 54 | Well day 1104 |

| 8 | Yes | No | Days 93-397 | From day 429 | Progression day 597 |

| 9 | Yes | No | Days 62-206 | No | Progression day 225 |

| 10 | Yes | No | Days 260-376 | Days 30-376 | Progression day 390 |

| 11 | No* | Yes | No | No | Progression and consent withdrawn day 33 |

| 12 | No | Yes | No | From day 545 | Progression day 102 |

| 13 | No | No | Days 253-620 | From day 30 | Well day 783 |

| 14 | No | No | No | No | Well day 333; lost to follow-up since |

| 15 | No* | Yes | Days 72-309 | From day 72 | Well day 693 |

| 16 | No | No | From day 42 | From day 42 | Well day 665 |

| 17 | Yes | No | Days 49-124 | From day 94 | Well day 648 |

| 18 | No | Yes | Days 167-451 | No | Progression day 451 |

| 19 | No | Yes | No | No | Well day 494 |

| 20 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Well day 404 |

| 21 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Well day 105; lost to follow-up since |

| 22 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Well day 384 |

| 23 | Yes | Yes | From day 119 | From day 147 | Well day 370 |

| 24 | No | Yes | Days 129-312 | No | Well day 341 |

| 25 | No* | Yes | Days 105-231 | No | Progression day 272 |

| 26 | No* | Yes | No | From day 282 | Well day 309 |

| 27 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Well day 246 |

| 28 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Well day 237 |

| 29 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Well day 236 |

| 30 | Yes | Yes | Days 89-117 | No | Well day 214 |

| 31 | No* | Yes | No | No | Well day 111 |

| 32 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Well day 66 |

| Case . | CD34 selected . | Post-BMT . | Outcome . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G-CSF . | IFN . | Bisphosphonate . | |||

| 1 | Yes | No | No | From day 358 | Well day 1363 |

| 2 | No | No | No | No | Progression day 501 |

| 3 | No | No | No | No | Renal failure day 353; progression day 491 |

| 4 | Yes | No | From day 115 | No | Progression day 640 |

| 5 | Yes | No | From day 814 | From day 546 | Well day 1206 |

| 6 | No | No | Days 181-467 | From day 181 | Progression day 658 |

| 7 | Yes | No | Days 106-730 | From day 54 | Well day 1104 |

| 8 | Yes | No | Days 93-397 | From day 429 | Progression day 597 |

| 9 | Yes | No | Days 62-206 | No | Progression day 225 |

| 10 | Yes | No | Days 260-376 | Days 30-376 | Progression day 390 |

| 11 | No* | Yes | No | No | Progression and consent withdrawn day 33 |

| 12 | No | Yes | No | From day 545 | Progression day 102 |

| 13 | No | No | Days 253-620 | From day 30 | Well day 783 |

| 14 | No | No | No | No | Well day 333; lost to follow-up since |

| 15 | No* | Yes | Days 72-309 | From day 72 | Well day 693 |

| 16 | No | No | From day 42 | From day 42 | Well day 665 |

| 17 | Yes | No | Days 49-124 | From day 94 | Well day 648 |

| 18 | No | Yes | Days 167-451 | No | Progression day 451 |

| 19 | No | Yes | No | No | Well day 494 |

| 20 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Well day 404 |

| 21 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Well day 105; lost to follow-up since |

| 22 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Well day 384 |

| 23 | Yes | Yes | From day 119 | From day 147 | Well day 370 |

| 24 | No | Yes | Days 129-312 | No | Well day 341 |

| 25 | No* | Yes | Days 105-231 | No | Progression day 272 |

| 26 | No* | Yes | No | From day 282 | Well day 309 |

| 27 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Well day 246 |

| 28 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Well day 237 |

| 29 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Well day 236 |

| 30 | Yes | Yes | Days 89-117 | No | Well day 214 |

| 31 | No* | Yes | No | No | Well day 111 |

| 32 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Well day 66 |

BMT, bone marrow transplant; BM, bone marrow; PBSC, peripheral blood stem cell; G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; IFN, interferon.

Transplanted with BM and PBSC.

Five patients without bony disease undergoing autologous transplantation for lymphomas were included as controls. Conditioning for each case was with BEAM (BCNU, etoposide, cytosine, and melphalan) from days −6 to −1. Follow-up was limited to 30 days in the control cases.

Investigations of bone mineral turnover

Clinical samples were taken immediately before starting conditioning therapy, daily until day 7, weekly until discharge from hospital, and every 1-2 months thereafter. Routine biochemistry analysis of serum and urine was performed on a Hitachi 747 analyser (Boehringer Mannheim, Lewes, UK). Urea, creatinine, calcium, and phosphate were all estimated by standard methodologies.

Bone resorption was assessed by urinary levels of free pyridinoline (fPyr) and deoxypyridinoline (fDPyr) crosslinks, using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), modified from the method described by Black et al.24 Acidified urine is applied to microgranular cellulose (CC31) in butanol 1:4, and washed before elution with heptafluorobutyric acid (0.1%). The eluate is then analyzed by ion pair reverse-phase HPLC by using fluorescence detection. Acetylated Pyr (Metra Biosystems, Oxford, UK) is used as an internal standard.25 Results are expressed as a ratio of the urinary creatinine (Creat) concentration (upper limit of normal = 21.8 nmol/mmol for fPyr/Creat and 6.4 nmol/mmol for fDPyr/Creat). The interassay coefficient of variation (CV) is less than 5.5% across the working range of the assay.

Collagen formation and osteoblast function were assessed by serum levels of procollagen 1 extension peptide (P1CP) and by bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BSAP). P1CP was measured in serum by radioimmunoassay supplied by Orion Diagnostica (Espoo, Finland), with a sensitivity of 1.2 μmol/L and a CV of 4.0%-6.6% at concentrations of 54-451 μmol/L. The upper limit of the reference range was 202 μmol/L in males aged 20-60 years; 170 μmol/L in other situations. BSAP was measured by using a commercial assay (Metra Biosystems, Oxford, UK), with a sensitivity of 0.7 U/L, a CV of less than 8% across the range 12-100 U/L, and an upper limit of the reference range of 20 U/L.

Results

No control patient had abnormal levels of fPyr, fDPyr, P1CP, or BSAP, either on admission for BMT or during subsequent follow-up (data not shown).

Bone resorption measurements

Eighteen of the 32 myeloma patients had normal urinary fPyr and fDPyr levels on admission for BMT. In all but one of these cases, fPyr and fDPyr levels did not become significantly elevated at any subsequent follow-up point. The remaining case (case 13) showed a modest transient increase in both fPyr and fDPyr 21-89 days post-BMT, although all subsequent follow-up measurements to day 650 have been in the reference range (data not shown).

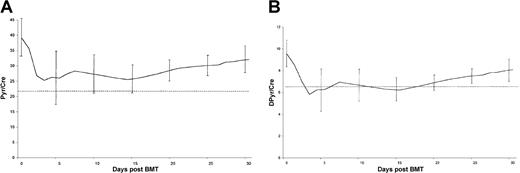

Fourteen patients had significantly elevated fPyr and fDPyr on admission for BMT (median = 31.2 and 8.2, respectively; mean = 41.0 and 9.2, respectively). Figure 1 shows the variation in mean fPyr and fDPyr in these 14 cases over the first 30 days from transplantation. There was a temporary decrease in both parameters for about 15 days after BMT; both fPyr and fDPyr were significantly less on day +5 than pre-BMT values (P = .005 and .007, respectively; Mann-Whitney test). Both fPyr and fDPyr rapidly returned to abnormally high pretransplant levels by day 30; there was no significant difference between fPyr and DPyr on day 30 compared with pre-BMT values.

Trends in mean fPyr (A) and mean fDPyr (B) concentrations in the first 30 days following BMT, for the 14 cases with elevated levels at transplant.

Error bars represent 95% confidence limits. Dotted line = upper limit of the reference range.

Trends in mean fPyr (A) and mean fDPyr (B) concentrations in the first 30 days following BMT, for the 14 cases with elevated levels at transplant.

Error bars represent 95% confidence limits. Dotted line = upper limit of the reference range.

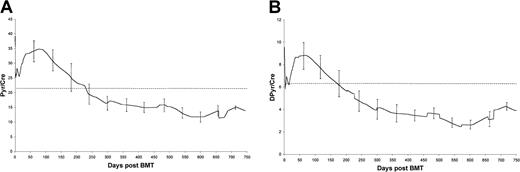

Figure 2 shows how the fPyr and fDPyr levels in these cases evolved over the 2 years following ABMT. The trend was for a gradual decrease of both fPyr and fDPyr into the normal range, and this decrease achieved statistical significance (P = .0009 for day 100 versus day 300 fPyr, andP = .0019 for day 100 versus day 300 fDPyr; Mann-Whitney test).

Long-term trends in mean fPyr (A) and mean fDPyr (B) concentrations for the 14 cases with elevated levels at transplant.

Error bars represent 95% confidence limits. Dotted line = upper limit of the reference range.

Long-term trends in mean fPyr (A) and mean fDPyr (B) concentrations for the 14 cases with elevated levels at transplant.

Error bars represent 95% confidence limits. Dotted line = upper limit of the reference range.

Effect of pre-BMT bisphosphonate and post-BMT therapy

No relationship was found between whether patients had received pre-BMT bisphosphonate and the presence of increased bone resorption at BMT. There was also no relationship between the pre-BMT use of bisphosphonate and the post-BMT trends of bone turnover markers. For the post-BMT trends in bone resorption markers described above, no difference was seen between patients who did or did not receive post-BMT bisphosphonate nor between those who did or did not receive post-BMT interferon.

Measurements of bone deposition

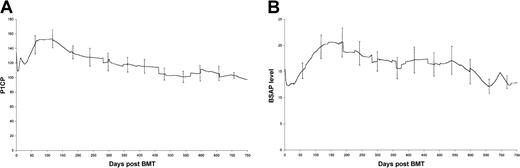

Figure 3 shows the results of P1CP and BSAP in all 32 cases. Results on case 3 are removed after day 302 post-ABMT because of deterioration in renal function and a rising parathormone level, because P1CP and BSAP levels are altered in the presence of renal osteodystrophy.26

Changes in P1CP (A) and BSAP (B) concentrations following BMT.

Error bars represent 95% confidence limits.

Changes in P1CP (A) and BSAP (B) concentrations following BMT.

Error bars represent 95% confidence limits.

Six patients (cases 2, 11, 12, 14, 24, and 27) had an elevated P1CP level at transplant, ranging from 188 to 268 μmol/L, 4 of whom also had elevated fPyr and fDPyr levels. In all 6 patients, P1CP levels returned to the reference range within 5 days of commencing conditioning therapy. Three different cases (16, 19, and 22) had elevated levels of BSAP; these levels also returned to within the reference range within 5 days of commencing conditioning.

Seventeen of 22 assessable cases had an increase of P1CP 50-150 days following BMT (an increase was defined as at least 50% of the P1CP values at 50-150 days were at least 20 μmol/L above the pre-BMT value). These data are shown in Figure 3A. P1CP levels at day 100 are significantly higher than pre-BMT levels (P = .03).

Similarly, several patients showed a posttransplant increase in BSAP levels (Figure 3B), beginning about 50 days from BMT; in some cases this increase persists into the second year of follow-up. In many cases, an increase in P1CP was associated with a rise in BSAP. In each case, this P1CP/BSAP elevation occurred at a time when fPyr and fDPyr were within the reference range, suggesting that at 50-150 days post-BMT, bone formation may exceed bone resorption.

No relationship was seen between the post-BMT rise in P1CP and the use of post-BMT bisphosphonates. As will be seen from the data of Table 2and Figure 3A, the rise in P1CP is at days 50-150, whereas only 6 cases have commenced bisphosphonate by day 147. In all cases, P1CP had returned to within the reference range by day 250 and remained within it thereafter. This rise cannot be explained by a gradual increase in bone remodeling following cessation of bisphosphonate treatment, for 2 reasons. First, such an increase would take 6-8 months to occur, whereas the present rise is already occurring well before day 100-150. Second, 8 cases received bisphosphonate pre-BMT but had not restarted it at the time of analysis, but 5 of these cases were followed for 105 days or less at the time of analysis, and none showed a rise in either P1CP or BSAP post-BMT. These 8 cases therefore hardly contribute to the rises shown in Figure 3.

Disease progression

Disease progression occurred in 11 patients (see Table 2), of which 9 were serological relapses without new bony lesions. One case developed an isolated soft tissue plasmacytoma in the pleura without alteration in the appearance of the adjacent ribs on plain radiographs, and one patient (case 2) developed a histologically confirmed new lytic lesion. Although increases in both fPyr and fDPyr levels were seen in case 2 at the time of progression (Figures 2A and 2B), insufficient data were available to test whether an upward trend in markers of bone resorption was predictive of disease progression.

Discussion

Previous reports have established that osteopenia may arise following BMT,23,27-29 However, these studies focused on recipients of allografts, in whom contributing factors might include prolonged glucocorticoid therapy, hormonal deficiency (because of total body irradiation), and cyclosporin A therapy,23 30Moreover, the patients in these series suffered from diseases that do not significantly affect bone metabolism. To our knowledge, no previous study has serially examined the effect of high-dose chemotherapy and autografting on bone turnover in myeloma.

In the present study, we report 2 principal findings. First, increased bone turnover may be present in about half of patients in serological plateau or remission. No statistically significant relationship was found between the use of pre-BMT bisphosphonate and the presence of raised fPyr or fDPyr levels at BMT. However, the absence of a statistically significant difference in the present data does not mean that pre-BMT bisphosphonate has no relevance, merely that we cannot detect a difference in the present data. A much larger study designed to explore this association will be of considerable interest.

All patients in this study received G-CSF before transplant for PBSC mobilization. G-CSF induces rapid bone remodeling and may increase osteoclast progenitor numbers31,32 and urinary fDPyr and serum alkaline phosphatase, peaking approximately 5 days after G-CSF commencement and returning to baseline about 7 days after cessation.33 Little is known of the long-term effects of G-CSF on the skeleton. Although prolonged G-CSF treatment may produce osteopenia in children, this condition might be due to their underlying marrow disorder.34 However, G-CSF treatment is unlikely to be the explanation of the increased fPyr and fDPyr levels seen on admission for BMT in 14 of the present cases, because G-CSF treatment was stopped at least 23 days before baseline measurements of bone turnover and also because no correlation was seen between fPyr and fDPyr levels and either the interval since stopping G-CSF or the total cumulative dose of G-CSF. The present data therefore suggest that the myeloma clone may continue to disturb bone turnover, independently of paraprotein production. This finding is in line with earlier histological evidence of persistent excessive osteoclast activity at plateau.4

A consistent observation was the temporary decrease in fPyr and fDPyr levels immediately following BMT, even in patients with normal fPyr and fDPyr levels on admission for BMT. This decrease was seen even in patients who received post-transplant G-CSF, which might be expected to produce an increase rather than a decrease in bone resorption. A possible explanation for this decrease is the cytotoxic effect of the conditioning chemotherapy.

Second, high-dose chemotherapy and autografting may normalize abnormal bone resorption. This effect may take several weeks to emerge. In many cases, this normalization is accompanied by an increase in markers of bone deposition, indicating increased osteoblast activity. These changes were not related to the posttransplant use of either bisphosphonates or interferon. There was also no relationship between the pre-BMT use of bisphosphonate and the post-BMT trends of bone turnover markers. In subgroup analysis, the post-BMT trends in bone resorption markers are apparent both in patients who received post-BMT bisphosphonate and in those who did not, although we acknowledge that the association between bisphosphonate therapy and bone turnover markers requires testing in a much larger study. Our findings suggest that a delayed effect of high-dose chemotherapy/autografting may be to uncouple bone resorption and deposition, in favor of promoting bone deposition. These data are therefore in line with the view that high-dose therapy and autografting can improve skeletal morbidity in myeloma. Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) was not carried out in the present study, although a recent serial study35 of DEXA suggests that recovery of bone density does occur following high-dose therapy in myeloma, in agreement with the present data.

In the present study, disease progression is defined in accordance with recent internationally agreed criteria.36 We cannot say from the present data whether increased bone resorption at BMT predicts a worse outcome (either in terms of time to progression or for the skeletal prognosis) or whether normalization of abnormal bone turnover following BMT improves the outlook. A much larger study will be needed to examine these roles for biochemical markers of bone metabolism.

In summary, we provide evidence that high-dose therapy and autografting may improve abnormal bone resorption in myeloma and also may lead to increased osteoblast activity. Skeletal endpoints have not been examined in clinical trials of high-dose therapy reported so far. It is possible that the skeletal benefit of high-dose therapy may occur independently of any beneficial effect on time to progression and overall survival and, therefore, that high-dose therapy might benefit the patient's quality of life even without improving survival. Future studies to test this possibility are required.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Richard E. Clark, Department of Haematology at the Royal Liverpool University Hospital, Prescot St, Liverpool L7 8XP, United Kingdom.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal