Abstract

The tyrosine kinase Syk has been proposed to play a critical role in the antiapoptotic effect of interleukin (IL)-5 in human eosinophils. However, little is known about the involvement of Syk in other IL-5–mediated activation events. To further address these questions, the role of Syk in IL-5–induced eosinophil differentiation, activation, and survival was analyzed using cells obtained from Syk-deficient mice. We could demonstrate that Syk-deficient fetal liver cells differentiate into mature eosinophils in response to IL-5 at the same rate as wild-type fetal liver cells and generate the same total number of eosinophils. Moreover, no difference in IL-5–induced survival of mature eosinophils between Syk−/− and wild-type eosinophils could be demonstrated, suggesting that the antiapoptotic effect of IL-5 does not require Syk despite the activation of this tyrosine kinase upon IL-5 receptor ligation. In contrast, eosinophils derived from Syk-deficient but not wild-type mice were incapable of generating reactive oxygen intermediates in response to Fcγ receptor (FcγR) engagement. Taken together, these data clearly demonstrate no critical role for Syk in IL-5–mediated eosinophil differentiation or survival but underline the importance of this tyrosine kinase in activation events induced by FcγR stimulation.

Introduction

Blood and tissue eosinophilia is a characteristic abnormality in various clinical conditions, such as allergy and asthma, where eosinophil-derived proteins contribute to specific pathologic features of these diseases.1-4 Increasing evidence indicates a unique role for interleukin (IL)-5 in the regulation of this selective eosinophilia. IL-5 not only regulates the terminal differentiation of committed eosinophil precursors but also activates mature eosinophils, prolongs their survival, and enhances degranulation.5-8 The unique role of IL-5 in eosinophil production, activation, and localization is further supported by findings that mice overexpressing IL-5 develop a long-lasting and selective eosinophilia, whereas IL-5–deficient mice are unable to produce increased numbers of eosinophils in response to specific antigens.5,6,9 Moreover, inhibition of IL-5 by neutralizing antibodies prevents eosinophil differentiation and infiltration of mature cells into inflamed tissues following antigen exposure.10-14

IL-5 exerts its functions on eosinophils by binding to a specific IL-5 receptor (IL-5R), which is a member of the hematopoietic receptor superfamily and composed of a ligand-specific α subunit and a common β (βc) subunit shared with IL-3 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor.15 Although neither of the receptor subunits contains a kinase-like catalytic domain, IL-5 does induce a rapid and reversible phosphorylation and activation of various cellular proteins, including protein kinases such as Lyn, Syk, Jak2, and Fyn as well as transcription factors such as Stat5.16The role of a number of these proteins has been recently associated with specific processes. Raf-1 kinase appears to have a central role for eosinophil activation and degranulation, whereas Lyn, Syk, Jak2, SHP-2, and Raf-1 are all intimately involved in cell survival.17,18 Among these few studies, the tyrosine kinases Lyn and Syk appear to be of particular importance for the antiapoptotic effect of IL-5 because depleting these kinases from human eosinophils by using antisense strategies completely abolished the IL-5–induced prolonged survival of these cells.18 19

Besides the proposed function of Syk in the prevention of apoptosis following IL-5 stimulation of eosinophils, this tyrosine kinase is also known as an important signaling molecule in immunoreceptor-stimulated T and B cells as well as Fc receptor–mediated activation and degranulation of mast cells, macrophages, and neutrophils.20-27 Cross-linking of FcεRI or Fcγ receptor (FcγR) as well as engagement of T- and B-cell antigen receptors leads to the recruitment and association of Syk to specific intracellular receptor domains, where the kinase binds through its 2 SH2 domains to phosphorylated tyrosines located within the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) of antigen or Fc receptor subunits.26-29 Targeted disruption of the Syk gene has demonstrated an essential role in murine development.30,31 These mice die perinatally, probably as a result of in utero hemorrhaging.31 However, analysis of chimeric mice reconstituted with Syk−/− fetal liver cells demonstrated that Syk was essential for B-cell development31 as well as for FcγR-mediated phagocytosis and the generation of reactive oxygen intermediates from macrophages and neutrophils.23,28 Moreover, Syk-deficient mast cells fail to degranulate, synthezise leukotrienes, and secrete cytokines when stimulated through FcεRI, clearly demonstrating the essential role of Syk in Fc receptor and immunoreceptor signaling.22 29

In the present study, the role of Syk in IL-5 signaling in eosinophils was analyzed using fetal liver cells derived from embryos genetically deficient for Syk. In particular, we compared the IL-5–induced differentiation of committed precursors into mature eosinophils as well as the IL-5–mediated prolonged survival of mature eosinophils in Syk-deficient and wild-type mice.

Materials and methods

Materials

All culture reagents were from Life Technologies (Paisley, UK). O-phenylenediamine, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), 30% hydrogen peroxide, histone H1, propidium iodide, superoxide dismutase, bovine serum albumin (BSA), the antirabbit immunoglobulin (Ig) G–alkaline phosphatase antibody, all the kinase inhibitors (phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], NaF, sodium vanadate, leupeptin, and pepstatin), and the protein A agarose were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co (Poole, England). Annexin V–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), IL-5, and normal rabbit IgG were from R&D Systems (Oxon, England). Diff-Quik stain was from Baxter Dade AG (Dudingen, Switzerland). Purified rat 2.4G2 monoclonal antibody was from Pharmingen. Goat antirat IgG polyclonal antibody was from Serotec Ltd (Kidlington, Oxford, England).

The anti-Syk rabbit polyclonal antibody used for immunoprecipitations was raised against amino acids 271 to 289 of murine Syk.31 The anti-Syk rabbit polyclonal (SC 1077) antibody used for Western blotting was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The enhanced chemifluorescence (ECF) substrate was obtained from Amersham Life Science (Buckinghamshire, England).

Fetal liver cell cultures

Because mice homozygous for a disruption of the Syk gene (Syk−/−) die perinatally,31 we obtained mutant and wild-type fetal livers at day 16.5 of gestation. Genotyping of offspring was performed by Southern blotting as described previously.31 Single fetal liver cell suspensions from wild-type and Syk-deficient mice were suspended at 106 cells/mL in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 2-mmol/L glutamine, 10% fetal calf serum, 50-μmol/L β-mercaptoethanol, 100-IU/mL penicillin, and 100-μg/mL streptomycin and cultured for various periods in the presence of IL-5 (0.1-5 ng/mL). Cells were analyzed every second day for 12 days. Cell viability was determined by trypan blue exclusion; cell numbers were determined by hemocytometry. Cytocentrifuge preparations were made, and the eosinophil phenotype was assessed both by the morphologic features and by eosinophil peroxidase (EPO) staining with O-phenylenediamine and counterstaining with thiazine.

IL-5 induced survival assay

Wild-type and Syk−/− fetal liver–derived cells were used after 8 days in culture, at which time they were either starved of IL-5 or maintained with various concentrations of IL-5 (0.1-2.5 ng/mL). After 24 hours and 48 hours, cells were harvested, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline, and spun at 350g for 5 minutes. The resulting pellet was then resuspended in 100 μL of binding buffer (10-mmol/L HEPES/NaOH, pH 7.4; 140-mmol/L NaCl; 2.5-mmol/L CaCl2) to which 5 μL of Annexin V-FITC (10 μg/mL) and 5 μL of propidium iodide (50 μg/mL) were added. The cells were analyzed by flow cytometry on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, England).

Cell stimulation

Fetal liver–derived eosinophils were used between day 6 and 10, after overnight starvation of IL-5. Cells were either left unstimulated or stimulated at 37°C with IL-5 (0.1-50 ng/mL). For FcγR stimulation, cells were incubated on ice with 2.4G2 rat antimouse monoclonal antibody before addition of cross-linking antibody (goat antirat polyclonal antibody, mouse adsorbed, 10 μg/mL) for indicated times. FcγR- and IL-5–stimulated cells were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline containing 1-mmol/L sodium vanadate and further lysed on ice for 10 minutes with 1 mL of ice-cold lysis buffer consisting of 50-mmol/L Tris-HCl, 150-mmol/L NaCl, 1-mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 1% Triton X-100 (pH 7.6), 1-mmol/L PMSF, 1-mmol/L sodium vanadate, 1-mmol/L NaF, 23-μmol/L leupeptin, and 1-μg/mL pepstatin. Cell lysates were either resolved on sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and subjected to Western blotting with rabbit polyclonal anti-Syk antibody before visualization with the ECF system and analysis with a PhosphoImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA), or they were immunoprecipitated with 30 μL of polyclonal anti-Syk antibody and protein A agarose for 4 hours at 4°C before further use in the in vitro kinase assay.

Oxidative burst

Fetal liver–derived eosinophils, used between day 6 and 10 (105 per well), were incubated with the relevant activators and cytochrome c at 1.5-mg/mL Hank's balanced salt solution per 0.1% BSA in the presence or absence of superoxide dismutase (20 μg/mL). Plates were then incubated at 37°C for 60 minutes before being analyzed for spectrometric absorbance at 550 nm to 540 nm. Superoxide dismutase inhibited 98.9% ± 0.7% and 99.3% ± 0.8% of the response in Syk−/− and wild-type–derived eosinophils.

In vitro kinase assay

Syk, immunoprecipitated as described above, was further washed twice with kinase buffer (50-mmol/L HEPES, pH 7.4; 5-mmol/L MgCl2; 5-mmol/L MnCl2; and 0.1-mmol/L sodium vanadate) and resuspended in 40 μL of kinase assay buffer (kinase buffer with 5-μmol/L adenosine triphosphate [ATP], 5-μmol/L histone H1, and 3.7 × 105 Bq [γ-32P]ATP). After a 30-minute incubation at 30°C, the reaction was terminated by spotting 25 μL of the supernatant onto P81 chromatography paper (Whatman). Filters were washed 4 times in 0.5% phosphoric acid, immersed in acetone, and dried before scintillation counting. Recombinant Syk was used as a positive control.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. All statistical analyses were performed using the Student unpairedt test.

Results

IL-5 induces eosinophil differentiation in fetal livers from both Syk−/− and wild-type mice

In a first set of experiments, the ability of IL-5 to stimulate eosinophil precursor growth and differentiation of Syk−/−and wild-type fetal liver cells was evaluated. Fetal liver single-cell suspensions from Syk−/− and wild-type mice were grown in the presence of various concentrations of IL-5 for 12 days. As shown in Figure 1A-B, after 2 days of culture with IL-5 (5 ng/mL), fetal livers from both Syk−/− and wild-type mice contained EPO+ cells displaying morphologic characteristics of precursors cells and very few mature eosinophils. Incubation with IL-5 for 12 days significantly increased the number of mature eosinophils with a loss of eosinophil precursors and noneosinophil lineage-committed cells. There was, however, no apparent difference in the number of IL-5–differentiated eosinophils between fetal liver cells obtained from Syk-deficient and wild-type mice (Figure 1C-D). In contrast, cultures maintained in medium without IL-5 contained very few or no EPO+ cells or mature eosinophils (results not shown).

Morphologic and cytochemical features of fetal liver–derived cells in culture with IL-5 (5 ng/mL).

Cytospin preparations of fetal liver–derived cells from wild-type (A,C) and Syk−/− (B,D) mice, maintained for 2 (A,B) and 12 (C,D) days after EPO staining and counterstaining. EPO is present in both mature and immature forms of eosinophils even when eosinophilic granules are not prominent. EPO+ cells at day 2 display the morphologic characteristics of precursors (large cell size and large unsegmented nucleus with loose chromatin), whereas EPO+cells at day 12 display characteristics of mature eosinophils (smaller cell size, donut-shaped nucleus with compact chromatin). Original magnification × 100.

Morphologic and cytochemical features of fetal liver–derived cells in culture with IL-5 (5 ng/mL).

Cytospin preparations of fetal liver–derived cells from wild-type (A,C) and Syk−/− (B,D) mice, maintained for 2 (A,B) and 12 (C,D) days after EPO staining and counterstaining. EPO is present in both mature and immature forms of eosinophils even when eosinophilic granules are not prominent. EPO+ cells at day 2 display the morphologic characteristics of precursors (large cell size and large unsegmented nucleus with loose chromatin), whereas EPO+cells at day 12 display characteristics of mature eosinophils (smaller cell size, donut-shaped nucleus with compact chromatin). Original magnification × 100.

To further analyze possible differences in IL-5–induced eosinopoiesis in Syk−/− and wild-type fetal liver cell cultures, we investigated the kinetics of eosinophil outgrowth up to 12 days. As shown in Figure 2A, the percentage of eosinophils increased in a time-dependent manner, reaching a plateau between days 10 and 12. Although the percentage of eosinophils increases up to day 12 (Figure 2A), the absolute number of eosinophils is maximal between days 6 and 10 (Figure 2B). Moreover, a dose-dependent IL-5–induced eosinopoiesis was observed in both Syk−/− and wild-type fetal liver cell cultures, with the maximum number of mature eosinophils being reached in cultures containing 2.5-ng/mL IL-5 (Figure 2B). Thus, no difference was found between Syk-deficient and wild-type fetal liver cells, because both cell types differentiate into mature eosinophils in response to the same concentrations of IL-5 with the same kinetics and gave rise to the same total number of eosinophils.

Time course of IL-5's (5 ng/mL) effect on Syk−/− and wild-type fetal liver–derived cultures.

Effect on Syk−/−, closed symbols; on wild-type, open symbols. (A) Total cell number (squares), eosinophil percentage (ovals), and mean values ± SEM from 3 independent experiments. (B) Total eosinophil numbers (triangles) were measured in cultures derived from 4 independent Syk−/− or wild-type mice and maintained with 0.1- (dashed line), 0.5- (plain line), or 2.5-ng/mL (bold line) IL-5 for various times. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Time course of IL-5's (5 ng/mL) effect on Syk−/− and wild-type fetal liver–derived cultures.

Effect on Syk−/−, closed symbols; on wild-type, open symbols. (A) Total cell number (squares), eosinophil percentage (ovals), and mean values ± SEM from 3 independent experiments. (B) Total eosinophil numbers (triangles) were measured in cultures derived from 4 independent Syk−/− or wild-type mice and maintained with 0.1- (dashed line), 0.5- (plain line), or 2.5-ng/mL (bold line) IL-5 for various times. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Role of Syk in IL-5–induced survival of eosinophils

Many studies have shown that IL-5 can inhibit eosinophil apoptosis up to 2 weeks in vitro as well as in explants of allergic sinus tissue. In contrast, eosinophils survive fewer than 48 hours in the absence of IL-5.32,33 A critical role of Syk in the antiapoptotic effect of IL-5 has been proposed in human eosinophils.19To assess the contribution of Syk to IL-5–mediated antiapoptotic signals, the survival of mature eosinophils obtained from wild-type and Syk−/− fetal livers was monitored. At the start of the experiment (day 6 or 8), the total cell number and the percentage of eosinophils were not significantly different between the wild-type and Syk−/− fetal liver–derived cells (93% ± 1% vs 92% ± 1% or 93% ± 2% vs 92% ± 1% eosinophils, respectively). Removal of IL-5 from these cultures resulted in a significant reduction in the number of viable eosinophils after 48 hours (Figure 3). In contrast, addition of various concentrations of IL-5 to these cultures significantly reduced the loss of viable eosinophils. No significant difference in viability after 48 hours between wild-type– and Syk−/−-derived eosinophils was noticed at any starting time and for any dose of IL-5 (0.02, 0.1, 0.5, 2.5 ng/mL), clearly demonstrating that Syk has no critical role in the IL-5–mediated survival of mouse eosinophils. It is noteworthy that although 0.02-ng/mL IL-5 is enough to prevent eosinophil apoptosis, higher amounts of IL-5 (> 0.5 ng/mL) are required to fully support eosinophil differentiation and maturation in vitro.

IL-5–induced eosinophil survival of wild-type and Syk−/− fetal liver–derived cells.

Mature eosinophils from 6-day-old (left) and 8-day-old (right) cultures (viability of wild-type [■] and Syk−/− [▪] cells at the starting date) were maintained with the indicated concentrations of IL-5 for 48 hours, after which time the viability of wild-type (○) and Syk−/− (●) cells was monitored as described in “Materials and methods.” Values are expressed as mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments.

IL-5–induced eosinophil survival of wild-type and Syk−/− fetal liver–derived cells.

Mature eosinophils from 6-day-old (left) and 8-day-old (right) cultures (viability of wild-type [■] and Syk−/− [▪] cells at the starting date) were maintained with the indicated concentrations of IL-5 for 48 hours, after which time the viability of wild-type (○) and Syk−/− (●) cells was monitored as described in “Materials and methods.” Values are expressed as mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments.

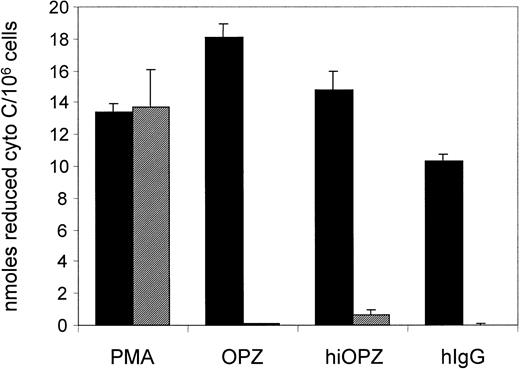

Syk−/− eosinophils fail to produce an oxidative burst in response to FcγR engagement

The results obtained so far clearly demonstrate no critical role of Syk in IL-5–mediated development and survival of murine eosinophils. However, this tyrosine kinase has been described as an important signaling molecule in Fc receptor–mediated activation and degranulation of mast cells, macrophages, and neutrophils.22,23,28 29 We therefore investigated whether signaling downstream of the FcγRs is affected in Syk−/−eosinophils. For that purpose, the role of Syk in the signaling events leading to the generation of reactive oxygen species in eosinophils upon FcγR stimulation was examined. Syk−/− and wild-type fetal liver–derived eosinophils were stimulated by exposure to IgG or zymosan particles opsonized with normal or heat-inactivated human serum, agents known to induce an oxidative burst in eosinophils. As shown in Figure 4, exposure to these stimuli triggered an oxidative burst in wild-type eosinophils. No significant difference between heat-inactivated and normal human serum opsonized zymosan was observed, suggesting that the production of reactive oxygen species in response to opsonized zymosan in these cultures is mediated mainly through Fc receptors and not complement receptors. Similar results were obtained using normal mouse serum opsonized zymosan (data not shown). In contrast, the IgG- and zymosan-induced generation of reactive oxygen species was completely abolished in Syk−/− eosinophils. This nonresponsiveness of Syk-deficient eosinophils to IgG stimulation was not due to a lack of FcγR expression because their number on Syk−/−eosinophils was similar to that of wild-type eosinophils (data not shown). Moreover, the defect in FcγR-mediated respiratory burst did not represent a general defect in the generation of reactive oxygen species by Syk-deficient eosinophils, because their response to PMA remained unaffected and comparable to that of wild-type cells. Thus, similarly to other cell types, Syk-deficient eosinophils have a selective block in FcγR signaling but are capable of generating reactive oxygen species in response to FcγR-independent stimuli.

Measurement of the oxidative burst response of mature eosinophils.

Eosinophils are derived from either wild-type (▪) or Syk−/− (░) fetal liver upon stimulation with PMA (20 ng/mL), normal human serum-opsonized zymosan (OPZ, 1 mg/mL), heat-inactivated normal human serum-opsonized zymosan (hiOPZ, 1 mg/mL), and human IgG (plate precoating) as determined by cytochromec reduction. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments.

Measurement of the oxidative burst response of mature eosinophils.

Eosinophils are derived from either wild-type (▪) or Syk−/− (░) fetal liver upon stimulation with PMA (20 ng/mL), normal human serum-opsonized zymosan (OPZ, 1 mg/mL), heat-inactivated normal human serum-opsonized zymosan (hiOPZ, 1 mg/mL), and human IgG (plate precoating) as determined by cytochromec reduction. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments.

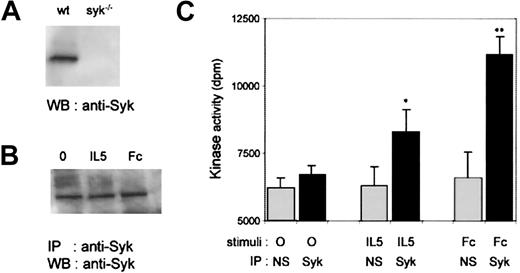

Activation of Syk by IL-5

Although Syk-deficient eosinophils respond normally to IL-5, they have defective responses to FcγR engagement. These data raise the question of whether Syk is indeed activated in response to IL-5 stimulation in wild-type murine eosinophils, because published data have only demonstrated IL-5–induced Syk activation in human eosinophils.19 We therefore compared the potency of IL-5 versus Fc stimuli to activate Syk in wild-type fetal liver–derived eosinophils. To address this, we first analyzed whether Syk was detectable in wild-type or Syk-deficient eosinophils. As expected, no Syk was detected in Syk−/− eosinophils, whereas it was readily detectable in wild-type murine eosinophils (Figure5A). To determine whether Syk was activated upon IL-5R or FcγR stimulation, we measured Syk kinase activity in fetal liver–derived wild-type eosinophils stimulated either with IL-5 or by cross-linking of FcγRs (CD16/CD32). Syk immunoprecipitates from stimulated cells, shown to contain equivalent amount of enzyme (Figure 5B), were used in an in vitro kinase assay. As shown in Figure 5C, both IL-5 and FcγR stimulation induced a significant increase in Syk kinase activity. Thus, although IL-5 ligation activates Syk, there appears to be no critical role for this tyrosine kinase in IL-5–induced murine eosinophil differentiation and survival.

Syk expression and activation in wild-type fetal liver–derived eosinophils.

(A) Expression of Syk in lysates of wild-type and Syk−/−fetal liver–derived eosinophils. Whole-cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotted with polyclonal rabbit anti-Syk antibody (Santa Cruz). (B) Starved mature eosinophils from 8-day-old cultures were stimulated with either 50-ng/mL IL-5 for 15 minutes (IL-5) or with anti-CD16/CD32 2.4G2 monoclonal antibody (2 μg/mL) for 30 minutes on ice and further cross-linking with goat antirat polyclonal antibody for 15 minutes at 37°C (Fc). The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with a polyclonal anti-Syk antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotted with polyclonal rabbit anti-Syk antibody for determination of Syk enzyme levels. (C) Lysates from stimulated cells were immunoprecipitated with a polyclonal anti-Syk antibody or with rabbit IgG (nonspecific, NS) and subjected to an in vitro kinase assay. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments. Significance of differences of Syk activity was determined by the Student t test, andP < .05 (*) or P < .005 (**) was considered significant.

Syk expression and activation in wild-type fetal liver–derived eosinophils.

(A) Expression of Syk in lysates of wild-type and Syk−/−fetal liver–derived eosinophils. Whole-cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotted with polyclonal rabbit anti-Syk antibody (Santa Cruz). (B) Starved mature eosinophils from 8-day-old cultures were stimulated with either 50-ng/mL IL-5 for 15 minutes (IL-5) or with anti-CD16/CD32 2.4G2 monoclonal antibody (2 μg/mL) for 30 minutes on ice and further cross-linking with goat antirat polyclonal antibody for 15 minutes at 37°C (Fc). The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with a polyclonal anti-Syk antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotted with polyclonal rabbit anti-Syk antibody for determination of Syk enzyme levels. (C) Lysates from stimulated cells were immunoprecipitated with a polyclonal anti-Syk antibody or with rabbit IgG (nonspecific, NS) and subjected to an in vitro kinase assay. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments. Significance of differences of Syk activity was determined by the Student t test, andP < .05 (*) or P < .005 (**) was considered significant.

Discussion

We demonstrate here that fetal liver cells derived from Syk-deficient embryos were fully capable of developing into mature eosinophils in response to IL-5. Moreover, no difference in the IL-5–induced antiapoptotic activity was found between wild-type and Syk-deficient eosinophils. These data clearly demonstrate that in murine cells differentiated in vitro, Syk plays no critical role in IL-5–mediated eosinophil differentiation, maturation, and survival.

In contrast, Syk appears to be absolutely required for the FcγR-induced oxidative burst in eosinophils. Indeed, the main function of Syk reported so far in myeloid lineages is downstream of FcγRs.23,28 The oxidative burst response triggered upon engagement of FcγRs is impaired in Syk-deficient eosinophils, while no defect was observed in response to a non-Fc stimulus like PMA. Similar results were obtained with Syk−/− neutrophils, which showed a complete block in the generation of reactive oxygen species in response to opsonin-IgG but responded normally to phorbol ester,28 and with Syk−/− macrophages, which exhibit impaired FcγR-induced phagocytosis but normal complement-induced phagocytosis.23 28 These results underline the critical role of Syk in FcγR-mediated activation events in multiple cell types.

There are only limited data available regarding the signaling pathways involved in IL-5–induced differentiation and maturation of eosinophils, mainly from signaling factor–deficient mice. Jak2−/− cells failed to respond to IL-5, indicating a crucial and nonredundant role of Jak2 in the IL-5 signaling leading to eosinophil growth and differentiation.34 Lyn-deficient mice are eosinopenic and have reduced eosinopoiesis in the bone marrow, suggesting a role for Lyn in eosinophil growth and differentiation.35 This observation was confirmed using a Lyn-specific inhibitor that abrogated IL-5–induced eosinophil differentiation from stem cells.36 Lyn, constitutively associated with the IL-5R β chain, is one of the earliest kinases activated after IL-5 stimulation, and in human eosinophils one of its functions may be to recruit and activate the cytosolic tyrosine kinase Syk.19 However, we show here that fetal liver cells derived from Syk−/− embryos show the same potential to develop into mature eosinophils in response to IL-5 as wild-type fetal liver cells. Hence, Syk is unlikely to be a critical signal transducer downstream of and recruited by Lyn in the IL-5–activated cascade leading to murine eosinophil differentiation. Similarly, no developmental deficiency could be demonstrated in other myelopoietic cells derived from Syk-deficient mice, such as monocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils.28 In contrast, blocks in the development of both B and γδ T cells have been reported in Syk-deficient mice, presumably because in these lineages Syk binds to and transduces antigen receptor signals required for progression through developmental checkpoints.28,30,31,37 38

Much evidence of the important role of IL-5 as an eosinophil survival factor has been reported.4,8,32,33 Lyn and Syk appeared to be of particular importance for the antiapoptotic effect of IL-5 because depletion of these kinases from human eosinophils by using antisense strategies or use of a Lyn-specific inhibitor completely abolished the IL-5–induced prolonged survival of these cells.18,19,36 In contrast, our results clearly demonstrate that Syk has no critical role in the IL-5–mediated survival of murine eosinophils. One potential explanation for this discrepancy with the published antisense data on human eosinophils is that there might be a species difference, with only the human IL-5R activating Syk. However, this is not the case, because we show here that IL-5 induces Syk activation in wild-type murine eosinophils. Another explanation for the difference could be that antisense administration renders cells acutely Syk-deficient whereas Syk−/− cells have a chronic Syk deficiency for which the eosinophil precursors may have compensated during their differentiation into mature eosinophils. Alternatively, other kinases could compensate for the lack of Syk in Syk-deficient murine but not human eosinophils. We were unable to detect the presence of the Syk-related kinase ZAP-70 39 in Syk-deficient eosinophils (data not shown), but we cannot rule out the possibility that another kinase could support IL-5–induced eosinophil differentiation and survival in the absence of Syk. However, we note that such compensation has not occurred in the FcγR signaling pathway, which we show here is absolutely dependent on Syk. In contrast, it appears that other signaling pathways like the Jak-Stat pathway, which is activated specifically by IL-5 but not FcγR, are essential in supporting eosinophil differentiation and survival.

Despite Syk not being required for IL-5–induced eosinophil differentiation and survival, we cannot rule out that Syk may play an important role in other IL-5–regulated activation events, such as priming, chemotaxis, and degranulation. These potential functions for Syk in IL-5 signaling are difficult to address in our system because IL-5 is required continuously during the culture of primary murine eosinophils for their survival.

In conclusion, this first report on Syk−/− eosinophils clearly shows that Syk plays no essential role in IL-5–regulated maturation and survival of murine fetal eosinophils. However, Syk plays a unique role in FcγR-induced oxidative burst, a pathway completely abrogated in Syk−/− eosinophils. Taken together with results from neutrophils and macrophages, this report on eosinophils further emphasizes the critical role of Syk in FcγR signaling.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Reth at the Max Planck Institute, Freiburg, Germany, for the generous gift of the Syk expressing baculovirus, D. Baldock and B. Graham for providing us with the recombinant Syk, and P. Finan and D. Head for critical reading and discussion of the manuscript.

Supported by a European Molecular Biology Organization (EMBO) long-term fellowship (E.S.) and partly funded by the Medical Research Council, London, England.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Christoph Walker, Novartis Horsham Research Centre, Wimblehurst Road, Horsham RH12 5AB, UK; e-mail:christoph.walker@pharma.novartis.com.

![Fig. 3. IL-5–induced eosinophil survival of wild-type and Syk−/− fetal liver–derived cells. / Mature eosinophils from 6-day-old (left) and 8-day-old (right) cultures (viability of wild-type [■] and Syk−/− [▪] cells at the starting date) were maintained with the indicated concentrations of IL-5 for 48 hours, after which time the viability of wild-type (○) and Syk−/− (●) cells was monitored as described in “Materials and methods.” Values are expressed as mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/96/7/10.1182_blood.v96.7.2506/5/m_h81900194003.jpeg?Expires=1766008333&Signature=vpWXAst0i1-~ePT-Pb7AyeKTbRvxNzhpU2r9OR~l4lYEPbXJstrbv1-NAVQ6shkDPoXAsQth5roI43awZ0C5Boe5qMbCZJ6wqZUEQCyLp63EmRlmYgXhieEwSVQYPo-eno1n7d48CmOEB2m8iNDZrqIouDysKEd3O0Vy7fcdU0klw2u4IrksxtbkQxq68je3hmbWqnEluyim6xa7lvx9llRgykfstRa4JJBmFWVwBDtHxM6dBA2WfWRMN3-ny2bGfkNVEIgB5sPXSnovQ6tn2mQDAHOCIvxvypDK1UFFn5hh4DSls5VkPryw1Uy91Fn-6RsSkvGBFzAiHccJ5-pUew__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal