Abstract

Neuroserpin, a recently identified inhibitor of tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA), is primarily localized to neurons within the central nervous system, where it is thought to regulate tPA activity. In the present study neuroserpin expression and its potential therapeutic benefits were examined in a rat model of stroke. Neuroserpin expression increased in neurons surrounding the ischemic core (ischemic penumbra) within 6 hours of occlusion of the middle cerebral artery and remained elevated during the first week after the ischemic insult. Injection of neuroserpin directly into the brain immediately after infarct reduced stroke volume by 64% at 72 hours compared with control animals. In untreated animals both tPA and urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) activity was significantly increased within the region of infarct by 6 hours after reperfusion. Activity of tPA then decreased to control levels by 72 hours, whereas uPA activity continued to rise and was dramatically increased by 72 hours. Both tPA and uPA activity were significantly reduced in neuroserpin-treated animals. Immunohistochemical staining of basement membrane laminin with a monoclonal antibody directed toward a cryptic epitope suggested that proteolysis of the basement membrane occurred as early as 10 minutes after reperfusion and that intracerebral administration of neuroserpin significantly reduced this proteolysis. Neuroserpin also decreased apoptotic cell counts in the ischemic penumbra by more than 50%. Thus, neuroserpin may be a naturally occurring neuroprotective proteinase inhibitor, whose therapeutic administration decreases stroke volume most likely by inhibiting proteinase activity and subsequent apoptosis associated with focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion.

Stroke is the second most common cause of death in the world after heart disease and a leading cause of disability.1 It is estimated that in the United States someone suffers a stroke about every minute and a person dies of stroke about every 3.5 minutes.2 Various strategies have been used to reduce stroke morbidity and mortality, one of which has been thrombolysis with tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) to restore cerebral blood flow to ischemic brain tissue. Thrombolysis with tPA produces arterial recanalization in 40% to 67% of patients3 and is associated with absolute improvement in neurologic function after 90 days in 12% of the patients treated within 3 hours of the onset of symptoms.4 However, in seeming contradiction to these results, animal studies have demonstrated that tPA-deficient mice have a 41% decrease in stroke size and a 61% increase in neuronal survival compared with wild-type animals following occlusion of the middle cerebral artery (MCA).5 Although these results have been recently challenged,6,7 they have also been reproduced by others.8 Furthermore, this latter study also demonstrated that animals deficient in plasminogen had an increase in stroke volume, whereas animals deficient in the primary plasmin inhibitor, α2-antiplasmin, had a decrease in stroke size similar to tPA null mice, suggesting a plasminogen-independent function for tPA in cerebral ischemia.8

In both rats and mice, tPA expression is increased by events that require neuronal plasticity, such as synaptic remodeling, long-term potentiation, kindling, and seizures.9-11 Expression of tPA is also correlated with central nervous system (CNS) development and maintenance, and in the modulation of cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions.12-14 As in stroke, tPA-deficient mice are protected from excitotoxin-induced neuronal death. However, in contrast to stroke, plasminogen-deficient mice are also protected from excitotoxic injury,15-17 and it has been suggested that tPA and plasminogen may promote excitotoxin-induced neuronal death through proteolysis of the neuronal ECM.18

Following stroke there is a densely ischemic area where neurons are irreversibly damaged, surrounded by an area known as “ischemic penumbra,” where cerebral blood flow is sufficiently decreased to abolish electrical potentials yet sufficient to allow maintenance of membrane potentials and cellular ionic homeostasis.19-21This zone of penumbra has also been observed in magnetic resonance image studies of rats in the area surrounding the necrotic core.22-24 With time, this potentially salvageable area of penumbra, or reversible ischemia, tends to become infarcted. In vivo microdialysis has demonstrated that after cerebral ischemia there is a large release of excitotoxins 25-28 not only in the infarcted core but also in the area of ischemic penumbra,29where the presence of apoptotic cells has also been described.30-32 Because tPA may play an significant role in both excitotoxin- and ischemia-induced neuronal degeneration,5,8,15-17 33 it is possible that an inhibitor of tPA might play an important role in neuronal survival after stroke.

Neuroserpin is a recently identified member of the serine proteinase inhibitor (serpin) gene family34,35 that reacts preferentially with tPA, having a second-order rate constant for the inhibition of tPA of 6.2 × 105M−1s−1.36Furthermore, neuroserpin expression is primarily localized to regions of the brain where tPA has been previously identified.36 The present study demonstrates that neuroserpin is expressed in the area of ischemic penumbra in an animal model of focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion. Moreover, intracerebral administration of neuroserpin after stroke decreases stroke volume, reduces basement membrane proteolysis, and diminishes the number of cells with apoptotic features in the area of ischemic penumbra. Thus, the data presented suggest that neuroserpin, a selective, naturally occurring inhibitor of tPA, may play an important role in neuronal survival after stroke.

Materials and methods

Animal preparation and surgery

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats weighting 350 to 400 g were used. Anesthesia was induced with 4% halothane, 70% nitrous oxide, and a balance of oxygen and was maintained with 2% halothane and 70% nitrous oxide during the surgical procedure. Rats were intubated endotracheally and mechanically ventilated. Arterial blood pressure and blood gases were monitored. Body temperature was maintained at 37.5 ± 0.5°C with a warming blanket (Animal Blanket Control Unit, Harvard Apparatus) and controlled with a rectal thermistor and a probe inserted into the masseter muscle. The MCA was exposed and cauterized with a microbipolar coagulator (Non-Stick Bipolar Coagulation Forceps, Kirwan Surgical Products, Marshfield, MA) above its crossing point with the inferior cerebral vein as described elsewhere.37 Animals were then placed on a stereotactic frame and 20 μL of either 30 μmol/L active neuroserpin in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 30 μmol/L inactive elastase-cleaved neuroserpin in PBS, or 20 μL of PBS only was injected intracortically with a Hamilton Syringe through the burr hole. Comparison of untreated animals (no injection) to PBS-treated rats revealed no significant difference in stroke volume, indicating that the injection itself did not contribute to the infarct size (data not shown). After the intracortical injections, the left common carotid artery was exposed through a midline cervical incision and temporarily occluded for 1 hour with a microaneurysm clip (8 mm, 100 g pressure; Roboz Surgical Instruments, Rockville, MD).38 Animals were then allowed to recover under the heating lamp, returned to their cages, and given free access to water.

Infarct volume

Rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital intraperitoneally 72 hours after infarction and brains were removed after transcardiac perfusion with PBS and paraformaldehyde 4% (Fisher Scientific, HC-200). The entire brain was embedded in paraffin and coronal sections, 20 μm thick, were cut through the rostrocaudal extent of the brain (Figure1). The sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and using the NIH Image Analyzer System, the total volume of each infarction was determined by the integration of the areas of 8 chosen sections and the distances between them. The rostral and caudal limits for the integration were set at the frontal and occipital poles of the cortex.39 Statistical significance between groups of animals was identified by a Student t test.

Rat brain sections 72 hours after reperfusion

. Hematoxylin-eosin stain of 3 representative sections from the same brain 72 hours after reperfusion. The infarcted area is indicated with arrows, and the box indicates the location where higher resolution analysis was performed (magnification × 5).

Rat brain sections 72 hours after reperfusion

. Hematoxylin-eosin stain of 3 representative sections from the same brain 72 hours after reperfusion. The infarcted area is indicated with arrows, and the box indicates the location where higher resolution analysis was performed (magnification × 5).

TUNEL staining

Paraffin-embedded sections (5 μm) from neuroserpin- and control-treated animals killed at 6, 24, 48, and 72 hours after reperfusion were examined for TUNEL reactivity using the Apoptag Kit (Oncor, Gaithesburg, MD). Paraffin sections were dewaxed, rehydrated, and treated with proteinase K (20 μg/mL) and blocked for endogenous peroxidase activity with 3% H2O2. Subsequent end-labeling was done with TdT enzyme at 37°C for 1 hour. Anti-digoxigenin peroxidase conjugate was applied to the tissue for 30 minutes at room temperature. The slides were developed with peroxidase substrate DAB for 5 minutes (Sigma, St Louis, MO), washed in dH2O for 5 minutes, and counterstained with 0.5% methyl green for 10 minutes. To quantitate the presence of cells with apoptotic bodies, an area surrounding the ischemic core extending from the cerebral cortex to the most anterior (septal) part of the hippocampus was imaged in neuroserpin- and control-treated animals. Histologic features used by light microscopy to identify apoptosis depended on recognition of dark-brown rounded or oval apoptotic bodies.40 41 Statistical significance between groups of animals was identified by a Student t test.

Zymography

For sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) zymography the region containing the stroke in brains from neuroserpin- and PBS-treated animals killed at 6 and 72 hours after reperfusion were dissected and slices of approximately 600 mg were frozen in dry ice and stored at −70°C. A similar portion of brain was dissected from the same area in the contralateral hemisphere in both neuroserpin-treated and control animals. Protein extracts were prepared in 1.2 mL extraction buffer as described.36 The protein concentration was then determined, and 30 μg of extract (approximately 1 μL) was mixed with nonreducing sample buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE on a 10% gel (Novex, San Diego, CA). Human tPA 0.3 ng (Genentech, San Francisco, CA) and a rat kidney extract containing urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) prepared in the same way as the brain extracts were included as positive controls and the identity of each PA was determined by including either anti-tPA or anti-uPA in the indicator film (data not shown). Following electrophoresis, the gel was soaked in 2.5% Triton X-100 for 2 × 45 minutes to remove the SDS. An indicator gel was prepared by mixing 1.25 mL of an 8% solution of boiled and centrifuged milk in PBS, 5 mL PBS, and 3.75 mL of a 2.5% agar solution prewarmed at 50°C. Plasminogen (Molecular Innovations, Royal Oak, MI), was added to a final concentration of 30 μg/mL and the solution mixed and poured onto a prewarmed glass plate. The Triton X-100 soaked gel was applied to the surface of the plasminogen-milk indicator gel and incubated in a humid chamber at 37°C. Milk indicator gel without plasminogen was also included as a control. The relative increase of tPA and uPA ipsilateral to the stroke at 6 hours after reperfusion was quantified by scanning a photograph of the SDS-PAGE zymography gel taken at an early time of development, before full lysis had occurred, and using the NIH Image Analyzer System. Normal baseline PA activities were calculated from the average of the activity present in 6 independent contralateral samples for which the coefficient of variation was less than 0.2. Control analysis of purified tPA by this method demonstrated that lysis was linear over at least an 8-fold range with a correlation coefficient (r) of 0.994. Statistical significance between groups was identified by a Student t test.

For the in situ proteinase activity assay, brains from neuroserpin- and control-treated animals killed at 6 and 72 hours after reperfusion (n = 3 for each condition at each time point) were frozen in optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT) and stored at −70°C. Cryostat sections 8 μm thick were examined for PA activity in overlays prepared as described.14 The overlay mixture (150 μL) was applied to prewarmed tissue sections and spread under glass coverslips. Slides were incubated in a humid chamber at 37°C and developed. Control sections were overlaid with a milk agar mixture without plasminogen. Other controls included those in which either 100 μg/mL anti-tPA (a generous gift of Tom Podor, MacMaster University) or anti-uPA (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA) antibodies or 5 μmol/L neuroserpin36 were included in addition to plasminogen.

Immunohistochemistry

All immunohistochemistry was performed on 5-μm deparaffinized-embedded sections. The sections were first immersed in methanol 0.3% H2O2 for 30 minutes and then either preincubated directly with 10% serum (either horse or goat) or first treated with 0.04% pepsin in 0.1 N HCl for 20 minutes at 23°C before being blocked with serum. All sections were also developed with the ABC reagent (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), using the DAB chromogen for 4 minutes, after which the sections were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin for 1 minute. For neuroserpin staining, adult male Sprague-Dawley rats that were not injected with neuroserpin or PBS were killed 6, 24, 48, 72, 96, or 168 hours after bipolar coagulation of the MCA, or sham operation, and sections were prepared as above and stained with rabbit antihuman neuroserpin as described.36 For tPA, uPA, and laminin, both control and neuroserpin-treated animals were examined. For tPA, the sections were stained with affinity purified sheep antihuman tPA (a generous gift from Tom Podor, MacMaster University), at 1:800 dilution after pepsin digestion. For uPA goat antihuman, uPA (Chemicon International-AB767) was used at 1:200 dilution after pepsin digestion. For laminin staining, a murine monoclonal antihuman laminin (Chemicon International-MAB2920) was used at a 1:4000 dilution either with or without pepsin digestion as above. For all immunohistochemical analysis, n ≥ 2 for each condition at each time point except for neuroserpin staining at 96 and 168 hours, for which n = 1 each.

Results

Neuroserpin expression after stroke

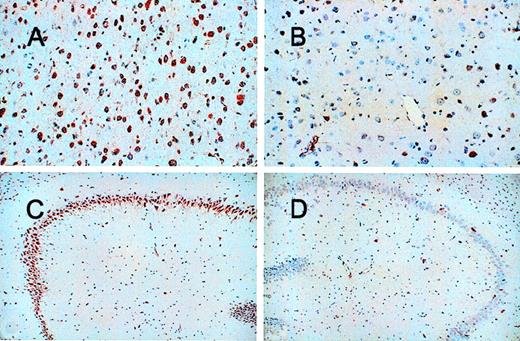

Because tPA may contribute to neuronal death after cerebral infarction, increased expression of neuroserpin might play an important role in neuronal survival after stroke. To examine the expression of neuroserpin after cerebral ischemia, immunohistochemical staining of brain sections was performed at 6, 24, 48, 72, 96, and 168 hours after MCA occlusion and reperfusion. Figure 1 shows 3 representative brain sections harvested 72 hours after reperfusion and stained with hematoxylin-eosin. The infarct is clearly evident as the lighter stained tissue in the cortex of the left hemisphere, and the box indicates the area where higher resolution analysis was performed. Neuroserpin immunoreactivity was increased in the area surrounding the ischemic core (penumbra) and in the ipsilateral hippocampus as early as 6 hours after stroke and remained elevated up to 168 hours when compared with the contralateral, nonischemic hemisphere or with sham-operated controls (data not shown). The peak of neuroserpin immunoreactivity in both the number of neuroserpin-positive cells and in the intensity of the staining appeared to be at 48 hours following reperfusion (Figure 2). The apparent rapid increase in neuroserpin expression following infarction suggests that the surrounding surviving cells may be up-regulating neuroserpin expression in response to the ischemic insult.

Immunohistochemical staining of neuroserpin in brain 48 hours after reperfusion.

Panel A shows the area of penumbra, panel B shows a similar area of the cortex contralateral to the stroke and panels C and D show the hippocampus. Panels A and C are ipsilateral to the stroke and panels B and D are contralateral (magnification × 100 in A and B and × 40 in C and D).

Immunohistochemical staining of neuroserpin in brain 48 hours after reperfusion.

Panel A shows the area of penumbra, panel B shows a similar area of the cortex contralateral to the stroke and panels C and D show the hippocampus. Panels A and C are ipsilateral to the stroke and panels B and D are contralateral (magnification × 100 in A and B and × 40 in C and D).

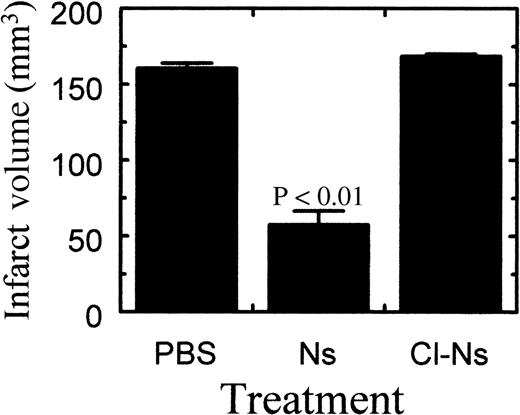

Effect of neuroserpin on stroke volume

To see if neuroserpin could reduce neuronal cell death after stroke with subsequent preservation of normal brain tissue, neuroserpin was administered intracerebrally immediately following MCA occlusion. Comparison of stroke volume between control and neuroserpin-treated animals 72 hours after reperfusion indicated that intracortical injection of 30 μmol/L neuroserpin reduced stroke size by 64%, from 161 mm3 in control animals to 58 mm3 in neuroserpin-treated animals (Figure 3). In contrast, stroke volume in animals treated with inactive neuroserpin, cleaved in its reactive center loop, showed no decrease in stroke size relative to control animals, suggesting that active neuroserpin is required to reduce stroke volume (Figure 3).

Quantitative analysis of infarct volume 72 hours after reperfusion.

Quantitation of the stroke volume was performed as described in “Materials and methods.” PBS indicates animals injected with PBS (n = 8); Ns, animals injected with neuroserpin (n = 8); Cl-Ns, animals injected with elastase-cleaved inactive neuroserpin (n = 2).P values relative to the PBS-treated animals < .01 are shown, and errors represent SEM.

Quantitative analysis of infarct volume 72 hours after reperfusion.

Quantitation of the stroke volume was performed as described in “Materials and methods.” PBS indicates animals injected with PBS (n = 8); Ns, animals injected with neuroserpin (n = 8); Cl-Ns, animals injected with elastase-cleaved inactive neuroserpin (n = 2).P values relative to the PBS-treated animals < .01 are shown, and errors represent SEM.

Proteinase activity after stroke

The fact that only the active inhibitory form of neuroserpin reduced stroke volume suggests that neuroserpin acts primarily by blocking proteinase activity, possibly tPA activity.36 To examine proteinase activity following stroke, and to determine the effect of neuroserpin treatment on proteinase activity, 2 different assays were used. The first, SDS-PAGE zymography was performed on extracts of tissues dissected from the cortex, either ipsilateral or contralateral to the stroke of both PBS- and neuroserpin-treated animals (Figure4A). After electrophoresis and removal of SDS, the gels were overlaid onto milk-agarose gels with or without plasminogen. In the absence of plasminogen no proteinase activity could be detected in any of the extracts, whereas addition of plasminogen to the milk-agarose mixture demonstrated that both tPA and uPA activity were present in all cortex extracts examined, including those from sham-operated animals (data not shown). Examination of extracts prepared from animals 6 hours after reperfusion suggested that both tPA and uPA activity were elevated ipsilateral to the stroke in PBS-treated animals but that only uPA appeared to be elevated in neuroserpin-treated brains (Figure 4A). However, by 72 hours tPA activity appeared to return to baseline, indicating that the increase in tPA activity is transient and that neuroserpin can reduce the extent of this increase. In contrast, uPA-catalyzed activity, which was relatively low in the 6-hour extracts, increased dramatically in ipsilateral extracts of animals killed 72 hours after reperfusion, and this increase was apparent in both control and neuroserpin-treated brains. However, like both tPA and uPA at 6 hours, the amount of uPA activity at 72 hours was significantly lower in neuroserpin-treated animals compared to controls (Figure 4A). Quantitative image analysis of these data indicated that by 6 hours following reperfusion ipsilateral to the stroke in PBS-treated animals there was an approximately 50% increase in tPA activity and an approximately 125% increase in uPA activity relative to baseline levels (Figure 4B). However, in neuroserpin-treated animals the increase of both PAs ipsilateral to the stroke was markedly reduced, showing only an approximately 50% increase for uPA and no significant increase in tPA compared to baseline levels (Figure 4B). These results indicate that there is an early and transient increase in tPA activity ipsilateral to the stroke and that neuroserpin is able to block this increase. Similarly, there is an early increase in uPA activity ipsilateral to the stroke, but in contrast to tPA this increase is not transient and continues to rise at least up to 72 hours after reperfusion, and is not blocked by treatment with neuroserpin but is only reduced compared to the PBS-treated animals.

SDS-PAGE zymography of brain extracts

. (A) SDS-PAGE zymography of brain extracts. Lane 1 is human tPA, lane 2 is a rat kidney extract as a marker for rat uPA, lanes 3 through 6 are extracts of brain 6 hours after reperfusion, and lanes 7 through 10 are extracts 72 hours after reperfusion. Lanes 3 and 7 are ipsilateral to the infarct of PBS- treated animals, lanes 4 and 8 are contralateral to the infarct. Lanes 5 and 9 are ipsilateral to the infarct in neuroserpin-treated animals and lanes 6 and 10 are contralateral. (B) Quantitative image analysis of PA activity from SDS-PAGE zymography of brain extracts 6 hours following reperfusion. The results represent the average fold increase in either tPA or uPA activity ipsilateral to the stroke relative to normal baseline PA activities contralateral to the stroke. PBS and Ns represent animals treated with either PBS or neuroserpin, respectively, and n ≥ 3 for each condition tested.P ≤ .05 relative to the contralateral activity are shown, and errors represent SEM.

SDS-PAGE zymography of brain extracts

. (A) SDS-PAGE zymography of brain extracts. Lane 1 is human tPA, lane 2 is a rat kidney extract as a marker for rat uPA, lanes 3 through 6 are extracts of brain 6 hours after reperfusion, and lanes 7 through 10 are extracts 72 hours after reperfusion. Lanes 3 and 7 are ipsilateral to the infarct of PBS- treated animals, lanes 4 and 8 are contralateral to the infarct. Lanes 5 and 9 are ipsilateral to the infarct in neuroserpin-treated animals and lanes 6 and 10 are contralateral. (B) Quantitative image analysis of PA activity from SDS-PAGE zymography of brain extracts 6 hours following reperfusion. The results represent the average fold increase in either tPA or uPA activity ipsilateral to the stroke relative to normal baseline PA activities contralateral to the stroke. PBS and Ns represent animals treated with either PBS or neuroserpin, respectively, and n ≥ 3 for each condition tested.P ≤ .05 relative to the contralateral activity are shown, and errors represent SEM.

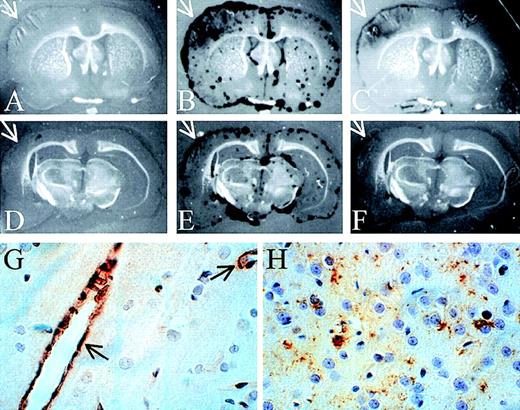

To examine the distribution of proteinase activity within the brains of the PBS- and neuroserpin-treated animals, in situ zymography of frozen brain sections was performed. These data demonstrate that, like the SDS-PAGE zymography, all of the proteolytic activity detected in both control and neuroserpin-treated brains was plasminogen dependent, because no proteinase activity was observed in the absence of plasminogen (Figure 5A,D). At 6 hours after reperfusion, proteinase activity in all sections was primarily associated with the meningeal tissues of both ipsilateral and contralateral sides. This activity was also completely blocked by the addition of anti-tPA antibodies, indicating that the majority of PA activity within the brain at this time is tPA (data not shown). In contrast, by 72 hours after reperfusion, there was a large increase in plasminogen-dependent proteolytic activity ipsilateral to the stroke in control animals (Figure 5B), and unlike the sections at 6 hours or the 72 hours contralateral side, this activity was not restricted to the meninges and was not completely blocked by the addition of anti-tPA antibodies to the plasminogen overlay (arrows in Figure 5B,C). In neuroserpin-treated animals this zone of proteinase activity was significantly smaller than in the untreated animals (Figure 5E,F). This suggests that by 72 hours much of the plasminogen-dependent activity within the region of the stroke was not tPA. Consistent with this, the addition of anti-uPA antibodies to the plasminogen overlay markedly reduced proteolysis within the area of the stroke while having no effect on the proteolytic activity in the meningeal tissues contralateral to the stroke (data not shown). This implies that within the area of the infarct at 72 hours following reperfusion there is a significant increase in uPA activity. These results also suggest that there is not a large up-regulation of either tPA or uPA immediately following stroke; however, by 72 hours after reperfusion, uPA-catalyzed proteolysis is significantly increased specifically within the region of the infarct. These results are also consistent with the SDS-PAGE zymography and suggest that the lesser increase in uPA activity observed by SDS-PAGE zymography in neuroserpin-treated animals may simply reflect the smaller size of the infarct in this group and not a direct inhibition of the up-regulation of uPA-activity by neuroserpin.

In situ zymography and immunohistochemical staining of brain sections

. In situ zymography in panels A-F; panels A and D are developed without plasminogen, and all other panels are developed with plasminogen. Panels C and F also contain anti-tPA antibodies. The white arrows indicate the area of the infarct (magnification × 3). (G) Immunohistochemical staining of tPA 6 hours after reperfusion. The black arrows indicate tPA-positive blood vessels. (H) Immunohistochemical staining of uPA in the area of penumbra 72 hours after reperfusion (magnification in G and H × 400).

In situ zymography and immunohistochemical staining of brain sections

. In situ zymography in panels A-F; panels A and D are developed without plasminogen, and all other panels are developed with plasminogen. Panels C and F also contain anti-tPA antibodies. The white arrows indicate the area of the infarct (magnification × 3). (G) Immunohistochemical staining of tPA 6 hours after reperfusion. The black arrows indicate tPA-positive blood vessels. (H) Immunohistochemical staining of uPA in the area of penumbra 72 hours after reperfusion (magnification in G and H × 400).

Immunohistochemical staining for tPA indicated that by 6 hours after reperfusion, tPA antigen was detected only within the vascular endothelial cells and not within neuronal cells (Figure 5G). Consistent with the relatively low levels of uPA activity at 6 hours, no uPA staining could be detected in these sections (data not shown). However, by 72 hours after reperfusion, uPA immunoreactivity was readily detected, but only in the area of ischemic penumbra (Figure 5H). This is consistent with the in situ zymography analysis demonstrating uPA activity predominantly within the cortex and only at 72 hours after reperfusion. Finally, at 72 hours in neuroserpin-treated animals, there was a marked reduction in the overall area where uPA antigen was detected but not in the intensity of the staining, compared to PBS-treated animals (data not shown). This further suggests that the reduced uPA activity observed by zymography was likely due to the reduced size of the infarct in neuroserpin-treated animals.

Basement membrane degradation after cerebral ischemia

Because excitotoxin-induced laminin degradation has been suggested to be mediated by tPA and to precede apoptotic cell death,18 we examined the effect of stroke on laminin immunoreactivity. For this analysis we used a monoclonal antibody that does not react strongly with rat laminin in fixed tissue unless the tissue is first proteolyzed to expose cryptic laminin epitopes. This is shown in Figure 6 panels A and B, where panel A shows a section of unproteolyzed rat cortex reacted with the antibody and panel B shows an adjacent section that was first treated with proteinase in vitro before reaction with the antibody. These results indicate that in the absence of proteolysis this antibody does not react with vascular laminin. However, after proteolysis there is a strong reaction that appears to be localized to the vessels. Thus, this antibody provides an excellent tool to probe for partial proteolysis of the basement membrane within fixed brain tissue. Examination of laminin staining in cortical tissue as early as 10 minutes after reperfusion indicated that even at this early time there was apparently significant proteolysis of the basement membrane in control animals (Figure 6C). However, in neuroserpin-treated animals the extent of laminin proteolysis was significantly reduced such that only slight staining of the vascular laminin was apparent (Figure 6D). This latter result was not due to the absence of laminin in this tissue because treatment of the sections with proteinase in vitro yielded staining indistinguishable from that shown in Figure 6B (data not shown). Vascular laminin staining was also observed at 6 hours after reperfusion in control animals and, similar to the results at 10 minutes, treatment with neuroserpin significantly reduced this staining (Figure 6E,F). Furthermore, by 6 hours after reperfusion laminin staining was also observed within neurons in the area of cerebral ischemia and, as with vascular laminin staining, was reduced by neuroserpin treatment (Figure 6E,F). The neuronal staining most likely represents new synthesis of laminin because in control animals not subjected to stroke no laminin staining was observed in neurons either with or without proteinase treatment (Figure 6A,B). Laminin staining remained strong at 24 and 48 hours, but started to decrease by 72 hours. Also, at each time point the neuroserpin-treated animals showed significantly less immunoreactivity than control animals (data not shown). These data suggest that there is a very early proteolytic event that appears to act on the vascular basement membrane and that neuroserpin treatment is able to reduce this proteolysis.

Immunohistochemical staining of laminin

. Panels A and B show normal cortex in an animal without stroke. Panel A was developed with anti-laminin but without pretreatment in vitro of the section with proteinase. Panel B is an adjacent section with in vitro proteinase treatment. Panels C to F are from stroked animals and developed with antilaminin and no proteinase treatment. Panels C and D are 10 minutes after reperfusion and panels E and F are 6 hours after reperfusion. Panels C and E represent PBS-treated and panels D and F neuroserpin-treated animals (magnification × 100).

Immunohistochemical staining of laminin

. Panels A and B show normal cortex in an animal without stroke. Panel A was developed with anti-laminin but without pretreatment in vitro of the section with proteinase. Panel B is an adjacent section with in vitro proteinase treatment. Panels C to F are from stroked animals and developed with antilaminin and no proteinase treatment. Panels C and D are 10 minutes after reperfusion and panels E and F are 6 hours after reperfusion. Panels C and E represent PBS-treated and panels D and F neuroserpin-treated animals (magnification × 100).

Apoptosis

Because cerebral ischemia has been suggested to induce apoptosis in the ischemic penumbra, a good therapeutic strategy aimed at reducing cell death after stroke should target the recovery of cells in this area. To see if neuroserpin reduced infarct volume by preventing penumbral apoptosis, tissue from untreated and neuroserpin-treated animals was stained by the TUNEL method (Figure7A-C). The extent of apoptosis in these sections was then quantified as described above and these data are shown in Figure 7, panel D. The number of cells within a defined area of the penumbra with apoptotic bodies after 72 hours of cerebral ischemia was 22 ± 5 in untreated animals and decreased to 8 ± 2 in neuroserpin-treated animals (Figure 7D). This indicates that neuroserpin significantly inhibits penumbral apoptosis. To see if neuroserpin also blocked cell death at earlier times, apoptosis was also quantified at 6, 24, and 48 hours. These data indicate that at all times examined apoptosis was reduced by at least 50% with neuroserpin treatment (Figure 7E). Finally, to test if neuroserpin had a direct effect on apoptosis, 2 independent assays were performed. In the first, neuroserpin was tested for its ability to block T-cell receptor-mediated apoptosis of a T-cell hybridoma in vitro.42 In the second assay, neuroserpin was tested for its ability to directly inhibit caspase activity in extracts of B lymphoma cells treated with anti-Fas IgG to induce apoptosis and caspase activation.43 In both assays neuroserpin had no effect on either apoptosis or caspase activity (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that neuroserpin is not a direct inhibitor of apoptosis, and therefore, it is likely that neuroserpin blocks events before induction of apoptosis.

Neuronal apoptosis within the ischemic penumbra

. TUNEL staining ipsilateral of the infarct in PBS-treated (panels A and B) and neuroserpin-treated (panel C) animals. In panel A, NC indicates the necrotic core and P indicates the area of the penumbra. Panels B and C are high magnification images of the penumbra in control (panel B) and neuroserpin-treated animals (panel C). Examples of cells considered to be apoptotic for the purposes of quantification are indicated with the open arrows; cells considered as necrotic are indicated with the closed arrows. Magnification in panel A is × 40 and in panels B and C × 400. (D) Quantitative analysis of apoptosis in the area of penumbra 72 hours after reperfusion. Quantitation was performed as described in “Materials and methods” and only cells with apoptotic bodies present (panel B) were counted. Control represents animals injected with PBS (n = 6). Neuroserpin indicates animals injected with neuroserpin (n = 6).P values < .05 are shown, and errors represent SEM. (E) Quantitation of apoptosis was performed as in panel D at the times indicated, (○) PBS-treated animals, (□) neuroserpin-treated animals.

Neuronal apoptosis within the ischemic penumbra

. TUNEL staining ipsilateral of the infarct in PBS-treated (panels A and B) and neuroserpin-treated (panel C) animals. In panel A, NC indicates the necrotic core and P indicates the area of the penumbra. Panels B and C are high magnification images of the penumbra in control (panel B) and neuroserpin-treated animals (panel C). Examples of cells considered to be apoptotic for the purposes of quantification are indicated with the open arrows; cells considered as necrotic are indicated with the closed arrows. Magnification in panel A is × 40 and in panels B and C × 400. (D) Quantitative analysis of apoptosis in the area of penumbra 72 hours after reperfusion. Quantitation was performed as described in “Materials and methods” and only cells with apoptotic bodies present (panel B) were counted. Control represents animals injected with PBS (n = 6). Neuroserpin indicates animals injected with neuroserpin (n = 6).P values < .05 are shown, and errors represent SEM. (E) Quantitation of apoptosis was performed as in panel D at the times indicated, (○) PBS-treated animals, (□) neuroserpin-treated animals.

Discussion

Neuroserpin, a natural inhibitor of tPA, is found almost exclusively within the CNS36 and shows an early and significant increase in its expression within the area of ischemic penumbra in response to stroke (Figure 2). Cerebral ischemia induces neuronal depolarization44 and releases excitotoxins,29which in turn triggers the release of tPA.45,46 Because tPA may be associated with increased neuronal loss in response to both ischemia and excitotoxins,5,8,15 33 the increased local expression of neuroserpin following ischemia may represent an innate protective response to elevated tPA levels and suggests that neuroserpin may be a naturally occurring neuronal survival factor. Consistent with this hypothesis, neuroserpin treatment resulted in a significant decrease in stroke volume relative to control animals. Furthermore, only functionally active neuroserpin was able to reduce infarct size, suggesting that inhibition of proteinase activity was necessary for the neuroprotective effects of neuroserpin (Figure 3).

Zymographic analysis of brain extracts at 6 and 72 hours after reperfusion indicated that there was an early rise in both tPA and uPA activity in the area of the infarct in control animals and that treatment with neuroserpin significantly reduced these activities (Figure 4). These data are similar to earlier results that reported an increase in uPA activity in both rats and mice following cerebral ischemia47,48 and to at least 1 other study that reported a significant increase in tPA activity.5 However, in 2 studies tPA activity after stroke was reported to be either decreased47 or unchanged.48 The apparent difference in the activity of tPA noted here compared to these earlier studies may in part reflect the time after cerebral ischemia when tPA was measured because our data suggest that the increase in tPA activity is transient and because none of these other studies measured tPA at 6 hours following reperfusion. These differences might also be due to the different animal models used in the various studies. For example, the model used here37,49 creates a permanent occlusion of the middle cerebral artery at its crossing point with the inferior cerebral vein with reperfusion provided by temporary clamping of the left carotid artery. This produces an ischemic injury in a well-defined area of the cerebral cortex (Figure 1), and in contrast to the intravascular filament model,50 avoids the potential of large lesions to the vascular endothelium and severe disruption of the blood-brain barrier that could lead to significant changes in the local tPA activity. Nonetheless, our results and those of Wang et al5suggest that there is an early local increase in tPA activity in the area of the infarct, and the data reported here further suggest that this increase is transient. Because treatment with functionally active neuroserpin reduced both the local increase in tPA activity as well as the infarct size, it is possible that these 2 effects are related and that by blocking the action of tPA very early after reperfusion the later increase of the infarcted area is prevented.

In contrast to tPA, uPA activity increased to very high levels by 72 hours following reperfusion and was localized almost exclusively to the ischemic penumbra (Figures 4 and 5). The role of uPA after cerebral ischemia is largely unknown. However, because the necrotic core is already well defined by 72 hours after the stroke, it is unlikely that the late increase in uPA activity plays an important role in the development of the infarct. This inference is also consistent with a recent study of stroke in uPA-deficient mice that indicated that there was no difference in infarct volume between wild-type and uPA−/− mice 24 hours after reperfusion.8However, because uPA has been demonstrated in both glial cells during myelination and in mature cortical neurons,51 the late expression of uPA activity and antigen suggests that uPA could participate in the process of neuronal recovery after stroke as was suggested by Rosenberg et al.47

Although the role of tPA activity in infarct evolution is not well understood, tPA-induced plasmin cleavage of basement membrane laminin has been suggested to play a role in excitotoxin-induced neuronal death within the hippocampus18 and in the disappearance of basement membrane antigens following ischemia and reperfusion.52 The basement membrane is a specialized part of the ECM that connects the endothelial cell compartment to the surrounding cell layers.53 Laminins are important components of the basement membrane, playing a pivotal role in cell-ECM interactions, including promotion of neurite outgrowth, cell attachment, proliferation, and differentiation, as well as in the development and regeneration of the CNS.54-58 In the present study exposure of cryptic laminin epitopes within the basement membrane was observed within 10 minutes of reperfusion, suggesting that there is proteolytic activity acting on the basement membrane very early following cerebral ischemia (Figure 6). Like the observed increase in tPA, this activity appears to be transient with peak epitope exposure occurring within 6 to 24 hours of reperfusion. Whether this effect is due to the direct action of tPA on laminin, is mediated through plasmin as has been suggested,18 or involves matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs)59 or other as yet unidentified proteinases is not clear. Regardless of which proteinase is responsible for the apparent basement membrane degradation, the extent of laminin epitope expression was significantly decreased in neuroserpin-treated animals (Figure 6). This suggests that neuroserpin is inhibiting the proteolytic attack on the basement membrane, most likely by inhibiting tPA. Thus, neuroserpin, by blocking the early increase in tPA activity, may be able to preserve the integrity of the basement membrane and thus the blood-brain barrier after stroke.

It is known that disruption of cell-matrix interactions can lead to apoptosis.60,61 Because the cryptic laminin epitopes were observed as early as 10 minutes after reperfusion, with high levels of neuronal expression seen by 6 hours (Figure 6), well before 24 to 48 hours, the peak of apoptosis (Figure 7E), the proteolytic disruption of the basement membrane may be the trigger that initiates the program of apoptotic neuronal cell death. Thus, the capacity of active neuroserpin to block tPA-induced degradation of the basement membrane may explain the ability of neuroserpin treatment to reduce neuronal apoptosis by nearly 70% (Figure 7D). Finally, although it has been demonstrated that apoptotic cell death in stroke is mediated by proteinases known as caspases,62-64 neuroserpin failed to inhibit either caspase activity or T-cell apoptosis, suggesting that neuroserpin is not an inhibitor of apoptosis per se and does not directly block caspase activation or activity.

Intraneuronal laminin-like immunoreactivity has been reported in both the developing and adult CNS,33,65,66 and in astrocytes after transient ischemia.67 Laminin has also been shown to promote neurite outgrowth.55 We observed morphologically healthy neurons that were positive for intracellular laminin staining in the area of penumbra in control animals by 6 hours after reperfusion (Figure 6E), suggesting a role for intraneuronal laminin in neuronal maintenance following ischemia. It is possible that synthesis of laminin by neurons is in response to laminin degradation within the basement membrane and that neuroserpin treated animals show fewer laminin-positive cells because there is less basement membrane degradation and thus many fewer distressed cells. It is interesting to note that the region of the cortex that shows many laminin-positive cells at 6 hours after reperfusion is the same region that shows many apoptotic cells at 48 hours. This suggests that if laminin expression is an early marker for cell distress then neuroserpin treatment must be acting very early in the pathway that leads to neuronal apoptosis.

Taken together the data presented here suggest a model for stroke-induced neuronal death within the ischemic penumbra and demonstrate the potential therapeutic benefits of neuroserpin in this setting. We speculate that one of the first potentially deleterious events to occur is the release of tPA by the vascular endothelial cells in response to the acute ischemia. If there is also increased vascular permeability at this time as a result of damage to the blood-brain barrier,68 then this will allow tPA to cross from the lumen of the vessel into the subvascular space, where it can bind directly to laminin.69 This inappropriately targeted tPA can then, either by itself or in concert with other proteinases such as plasmin or MMPs,59,70 begin to degrade the basement membrane. This leads to a further increase in vascular permeability, which in turn may accelerate the degradation of the blood-brain barrier. In addition, neuronal cells that are also dependent on the integrity of the basement membrane may begin to lose their contacts with the substrate, which in itself might induce a program of apoptosis as has been described for other cell types.60 Our data also suggest that by approximately 72 hours after the stroke onset the basement membrane degradation and neuronal apoptosis have decreased, stabilizing the lesion. At this time other factors such as uPA are up-regulated possibly as part of the recovery process. Neuroserpin treatment, by blocking the early effects of proteinase activity, may help to maintain the integrity of the basement membrane, preventing further passage of tPA or other potentially harmful blood-borne factors to the subvascular space. Neuroserpin may also directly prevent neuronal loss by helping to preserve neuronal contacts to the basement membrane. Further studies of the efficacy of neuroserpin in the treatment of acute stroke will certainly clarify and refine this possible model.

Acknowledgment

We wish to thank K. Ingham for critically reading the manuscript.

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL55374 and HL55747 to D.A.L.

Reprints:Daniel A. Lawrence, Biochemistry Department, J. H. Holland Laboratory, American Red Cross, 15601 Crabbs Branch Way, Rockville, MD 20855; e-mail: lawrenced@usa.redcross.org.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal