Abstract

The role of the chemokine binding stromal-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) in normal human megakaryopoiesis at the cellular and molecular levels and its comparison with that of thrombopoietin (TPO) have not been determined. In this study it was found that SDF-1, unlike TPO, does not stimulate αIIbβ3+ cell proliferation or differentiation or have an antiapoptotic effect. However, it does induce chemotaxis, trans-Matrigel migration, and secretion of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) by these cells, and both SDF-1 and TPO increase the adhesion of αIIbβ3+ cells to fibrinogen and vitronectin. Investigating the intracellular signaling pathways induced by SDF-1 and TPO revealed some overlapping patterns of protein phosphorylation/activation (mitogen-activated protein kinase [MAPK] p42/44, MAPK p38, and AKT [protein kinase B]) and some that were distinct for TPO (eg, JAK-STAT) and for SDF-1 (eg, NF-κB). It was also found that though inhibition of phosphatidyl-inositol 3-kinase (PI-3K) by LY294002 in αIIbβ3+ cells induced apoptosis and inhibited chemotaxis adhesion and the secretion of MMP-9 and VEGF, the inhibition of MAPK p42/44 (by the MEK inhibitor U0126) had no effect on the survival, proliferation, and migration of these cells. Hence, it is suggested that the proliferative effect of TPO is more related to activation of the JAK-STAT pathway (unique to TPO), and the PI-3K–AKT axis is differentially involved in TPO- and SDF-1–dependent signaling. Accordingly, PI-3K is involved in TPO-mediated inhibition of apoptosis, TPO- and SDF-1–regulated adhesion to fibrinogen and vitronectin, and SDF-1–mediated migration. This study expands the understanding of the role of SDF-1 and TPO in normal human megakaryopoiesis and indicates the molecular basis of the observed differences in cellular responses.

Introduction

The immunoglobulin superfamily cytokine receptor c-mpl binds thrombopoietin (TPO), and the 7-transmembrane G-protein–coupled chemokine receptor CXCR4 binds stromal-derived factor 1 (SDF-1).1-8 Targeted disruption of the genes for TPO or c-mpl results in thrombocytopenia, and animals defective in either SDF-1 or CXCR4 have a deficit in colony-forming units–megakaryocyte (CFU-MK) in the adult marrow.1-4 Both receptors are present in high concentrations on the surfaces of developing megakaryocytes,1,2,9-11 but though the role of c-mpl during megakaryopoiesis has been established, that of CXCR4 is less clear. SDF-1 stimulates chemotaxis of early megakaryocytic progenitors and plays a role in the migration of megakaryocytic (αIIbβ3+) cells in the bone marrow and potentially in the release of platelets.10-16 A recent study using a murine model has also indicated that SDF-1 acts together with TPO in promoting CFU-MK proliferation,17which is in contrast to studies by our group and others showing that SDF-1 does not effect megakaryocytic precursor proliferation.10,11 We have previously described a method using a chemically defined artificial serum for ex vivo expansion of normal human αIIbβ3+cells,18-20 which were shown by immunophenotypical and morphologic criteria to be megakaryoblasts10,18-22 and, hence, are a good model for studying various aspects of megakaryopoiesis and signal transduction pathways. Although some SDF-1 and TPO signaling pathways have been investigated in hematopoietic cell lines, platelets, and murine megakaryocytes,23-29intracellular signaling pathways in normal human αIIbβ3+ cells have not been elucidated. It is unknown which of the intracellular signaling pathways are critical for regulating various aspects of human megakaryopoiesis (proliferation, differentiation, inhibition of apoptosis, and so on)1; moreover, data derived from cell lines cannot always be reliably extrapolated.23

The aim of this study was to extend our understanding of the molecular basis of megakaryopoiesis by investigating the biologic responses of human megakaryocytic cells to stimulation by SDF-1 or TPO and the intracellular signaling pathways involved (mitogen-activated protein kinase [MAPK] p42/44, p38, JNK, AKT [protein kinase B], NF-κB, STAT-1, STAT-3, STAT-5, and STAT-6). Similarities and discrepancies observed in the activation of particular pathways were related to the biologic effects of SDF-1 and TPO on cell activation, adhesion, proliferation, apoptosis, and secretion of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). To ascertain the significance of our observations, we blocked phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI-3K) activity and MAPK p42/44 pathway with the specific inhibitors LY294002 and U0126, respectively.

Our results suggest that SDF-1 and TPO activate human megakaryoblastic αIIbβ3+ cells by overlapping (MAPKp42/44, p38, AKT), but distinct, intracellular signaling pathways (JAK-STAT for TPO and NF-κB for SDF-1). The result of these differences in intracellular signaling appears to be that SDF-1 increases the interaction of these cells with their microenvironment but has no effect on their proliferation, differentiation and survival, whereas TPO has the opposite role. Moreover, we demonstrate that the proliferative effect of TPO is more related to activation of the JAK-STAT pathway unique to TPO and that the PI-3K–AKT axis, which plays an important role in the biology of human megakaryoblasts, is differentially involved in TPO and SDF-1–dependent signaling.

Materials and methods

Human CD34+ cells, megakaryoblasts, and platelets

Light-density bone marrow mononuclear cells (BM MNCs) were obtained from consenting healthy donors, depleted of adherent cells and T lymphocytes (A−T− MNCs), and enriched for CD34+ cells by immunoaffinity selection with MiniMACS paramagnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) as described.10,18-20,30 31 The purity of isolated BM CD34+ cells was greater than 95%, as determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis.

BM CD34+ cells were expanded in a serum-free liquid system, and growth of CFU-MK was stimulated with recombinant human (rh) TPO (50 ng/mL) and rhIL-3 (10 ng/mL) (both from R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) as described.19,20,31 After incubation for 11 days at 37°C, approximately 85% of the expanded cells were positive for the megakaryocytic-specific marker αIIbβ3+,22,30,31and this population was further enriched to more than 95% purity (as determined by FACS analysis) by additional selection with immunomagnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec), as previously described by us.20 31

Cell cycle analysis and detection of apoptosis by Annexin V binding assay, caspase-3 activation, and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase cleavage

DNA content as a measure of cell cycling was determined as previously described.32 Briefly, αIIbβ3+ cells (2 × 106 ) were stimulated with appropriate ligands (IL-3, TPO, or SDF-1α or β) and after fixation were spun down; 250 to 500 μL RNase (50 μg/mL in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) was then added, and the cells were incubated (at 37°C for 30 minutes) and resuspended in 250 to 500 μL propidium iodine solution (50 μg/mL in sodium citrate; Sigma, St Louis, MO) before reincubation at room temperature for 30 minutes. Subsequently, the cells were analyzed using FACstar and the Cell Quest program.

Apoptosis was assessed by staining with FITC-Annexin V and flow cytometric analysis (FACScan; Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) and by using the apoptosis detection kit (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Activation of caspase-3 and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage was determined by FACS and Western blot analysis, respectively, according to the manufacturers' protocols (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Cellular extracts were assayed for telomerase activity using the PCR-based telomeric repeat amplification protocol assay as described.33

Chemotaxis, trans-Matrigel migration, Ca 2+ fluxes, and MMP and VEGF production

Chemotaxis assays to SDF-1 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ; R&D Systems) or TPO (R&D) through an 8-μm pore filter were performed in Costar-Transwell 24-well plate (Costar Corning, Cambridge, MA) as described before.34 Results were calculated as a percentage of the input number of cells. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Chemoattraction of megakaryoblasts across Matrigel was evaluated in a trans-Matrigel migration assay according to a method previously described by us.35,36 The lower chambers were filled with migration media containing 100 ng/mL SDF-1α or TPO, and percentage migration was calculated from the ratio of the number of cells recovered from the lower compartment to the total number of cells loaded. To examine the role of MMPs, specifically MMP-2 and MMP-9, in trans-Matrigel migration, megakaryoblasts were preincubated for 2 hours with 10 μg/mL MMP inhibitors rhTIMP-1 (a gift from Dr Dylan Edwards, University of East Anglia, United Kingdom) or rhTIMP-2 (a gift from Dr Rafael Fridman, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI) before they were loaded onto Boyden chambers, and the trans-Matrigel migration assay was conducted as before. To evaluate MMP secretion by megakaryoblastic cells, 2 × 106 cells/mL were incubated (for 3-24 hours at 37°C in 5% CO2 ) in the absence or presence of 100 ng/mL SDF-1 or TPO, and the cell-conditioned media were analyzed immediately by zymography as described previously.36 37The intensity of the bands was quantified using the National Institutes of Health ScionImage for Windows software (Scion, Frederick, MD).

Ca++ flux studies on ex vivo–expanded megakaryoblasts were performed using a spectrophotofluorimeter, as previously described.10,34 Secretion of VEGF by normal human megakaryoblastic cells was evaluated by the Quantikine human VEGF immunoassay (R&D) according to the manufacturer's protocol, as described.20

αIIbβ3 Receptor activation and adherence assays

Activation of αIIbβ3 receptors was measured using the MoAb PAC-1 (Becton Dickinson) as previously described.38 The αIIbβ3+ cells (1 × 106) were washed twice with PBS, resuspended in 50 μL PBS plus 2% fetal bovine serum, and treated with the appropriate ligands: thrombin (2 U/mL), SDF-1α (500 ng/mL), or TPO (100 ng/mL) for 5 minutes. Subsequently, 20 μL FITC-conjugated PAC-1 was added, and the cells were incubated for 15 to 20 minutes at room temperature in the dark. RGDS peptide38 was added to confirm specific binding of PAC-1 antibody. After staining, cells were analyzed by FACstar and the Cell Quest program.

Adherence assays of αIIbβ3+cells were performed as described.39 In brief, 96-microtiter plates (Dynatech Labs) were covered with 4 μg/mL BSA, fibrinogen, vitronectin, fibronectin, or VCAM-1 (all from Sigma), and αIIbβ3+ cells (106/mL) were incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C in lymphocyte suspension buffer39 in the absence or presence of SDF-1 (500 ng/mL), TPO (100 ng/mL), SDF-1 + TPO (500 ng/mL + 100 ng/mL), 2 U/2 mL thrombin or IL-3 (100 ng/mL). Cell suspensions (100 μL) were applied to the wells and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. The number of adherent cells was estimated by using the colorimetric phosphate assay as described.40

Phosphorylation of intracellular pathway proteins

Western blot analysis was performed on extracts prepared from human αIIbβ3+ cells (1 × 107), which were kept in RPMI medium containing low levels of BSA (0.5%) to render the cells quiescent. The cells were then divided and stimulated with optimal doses of SDF-1α or SDF-1β (500 ng/mL) or TPO (100 ng/mL) for 1 minute to 2 hours at 37°C, and cells were then lysed for 10 minutes on ice in M-Per lysing buffer (Pierce, Rockford, IL) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma). Subsequently, the extracted proteins were separated on either a 12% or 15% SDS-PAGE gel, and the fractionated proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH) as previously described.20,34 Phosphorylation of each of the intracellular kinases—MAPK p44/42, MAPK p38, JNK MAPK, p90 RSK, AKT, ELK-1 and STAT-1, -3, -5, and -6—was detected using commercial mouse phosphospecific monoclonal antibody (p44/42) or rabbit phosphospecific polyclonal antibodies for each of the remainders (all from New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat antimouse IgG or goat antirabbit IgG as a secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), as described.13 26 Equal loading in the lanes was evaluated by stripping the blots and reprobing them with the appropriate monoclonal antibodies: p42/44 anti-MAPK antibody clone 9102, anti p38 MAPK antibody clone 9212, an anti-JNK antibody clone 9252, an anti-AKT antibody clone 9272, an anti–ELK-1 antibody clone 9182, an anti–STAT-3 9132 (New England Biolabs), an anti–STAT-1 sc-464 and STAT-6 sc-1689 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), an anti–STAT-5 89 or p90 RSK 78 (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY). The membranes were developed with an ECL reagent (Amersham Life Sciences, Little Chalfont, UK) and subsequently dried and exposed to film (HyperFilm; Amersham Life Sciences). Densitometric analysis was performed using exposures that were within the linear range of the densitometer (Personal Densitometer SI; Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA) and ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics).

Blocking of PI-3K and MEK

PI-3K and MAPK p42/244 activities were blocked by selective inhibitors. To assess the effects of the PI-3K inhibitor LY294002 (Sigma) or the MEK inhibitor U0126 (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA), cells were preincubated with each of these compounds for 30 minutes before SDF-1α or TPO stimulation.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

To evaluate NF-κB pathways, nuclear extracts were prepared from normal human megakaryoblasts using a modified method of Pan et al,41 and electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed using 2.5 μg nuclear extract as described previously.41 Oligonucleotides and their complementary strands for EMSA were obtained from Promega (Madison, WI) and Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The sequences were a consensus κB site (underlined), 5′-AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCC CAGGC-3′ (NF-κB).41,42 [γ-32 P]ATP (greater than 500 Ci/mmol) was from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech.

Statistical analysis

Arithmetic means and standard deviations of our FACS and chemotaxis data were calculated on a Macintosh computer PowerBase 180 (Apple, Cupertino, CA), using Instat 1.14 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA) software.

Results

SDF-1 does not affect proliferation of human CFU-MK and megakaryoblasts

It has been unknown whether SDF-1 stimulates human CFU-MK colony formation. In our previous studies, we used a plasma clot system10 that might have contained confounding growth factors. Hence, to remove the unwanted influence of growth factors and cytokines in a serum, we now evaluated the growth of CFU-MK or αIIbβ3+ cells stimulated with SDF-1 or TPO in cultures supplemented with chemically defined artificial serum.18-20,30 SDF-1 was found not to have any effect, either on its own or acting as a costimulator with TPO, on the formation of human CFU-MK colonies from CD34+ cells (Table1). In addition, when human megakaryoblastic αIIbβ3+ cells were expanded ex vivo from CD34+ cells (in the presence of a suboptimal or an optimal dose of TPO + IL-3) and SDF-1 was added as a costimulator, we did not observe SDF-1 to affect proliferation or maturation of these cells at days 6 and 11 of culture (Table2). Neither the number of αIIbβ3+ cells in the cultures nor the intensity of expression of αIIbβ3+ on the cell surface changed (data not shown). Because it has been recently suggested that SDF-1 may stimulate proliferation of CD34+ cells if used at very low concentrations,43 we repeated these experiments using low doses of SDF-1 (10 pg to 1 ng/mL) and still did not observe any effect on cell proliferation (data not shown).

CFU-MK colony formation by human CD34+ cells in serum-free, semisolid methylcellulose medium

| . | SDF-1 100 ng/mL . | TPO 25 ng/mL . | SDF-1 + TPO 100 ng/mL + 25 ng/mL . |

|---|---|---|---|

| CFU-MK | 0 ± 0 | 87 ± 26 | 89 ± 31 |

| . | SDF-1 100 ng/mL . | TPO 25 ng/mL . | SDF-1 + TPO 100 ng/mL + 25 ng/mL . |

|---|---|---|---|

| CFU-MK | 0 ± 0 | 87 ± 26 | 89 ± 31 |

Each data entry constitutes 3 independent clonogenic assays from 3 different donors. Data shown are mean ± 1 SD.

CFU-MK indicates colony-forming units–megakaryocyte.

Lack of SDF-1 effect on TPO + IL-3–dependent proliferation of human CD34+ BM MNCs

| . | Suboptimal* stimulation by TPO + IL-3 . | Suboptimal stimulation by TPO + IL-3 + SDF-1 . | Optimal*stimulation by TPO + IL-3 . | Optimal stimulation by TPO + IL-3 + SDF-1 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 6 | 1.2 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 0.8 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 0.7 |

| Day 11 | 3.6 ± 1.9 | 3.5 ± 2.2 | 6.8 ± 2.8 | 6.1 ± 3.5 |

| . | Suboptimal* stimulation by TPO + IL-3 . | Suboptimal stimulation by TPO + IL-3 + SDF-1 . | Optimal*stimulation by TPO + IL-3 . | Optimal stimulation by TPO + IL-3 + SDF-1 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 6 | 1.2 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 0.8 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 0.7 |

| Day 11 | 3.6 ± 1.9 | 3.5 ± 2.2 | 6.8 ± 2.8 | 6.1 ± 3.5 |

Each data entry consists of data from 3 different donors. Data shown represent mean ± 1 SD.

SDF-1 indicates stromal-derived factor 1; TPO, thrombopoietin; IL-3, interleukin-3; BM MNCs, bone marrow mononuclear cells.

CD34+ cells (104 cells/point) were ex vivo expanded toward megakaryoblasts in the presence of TPO + IL-3 at suboptimal doses (10 ng/mL + 5 U/mL) or optimal doses (50 ng/mL + 20 U/mL) in the presence or absence of SDF-1 (100 ng/mL).

Cell cycle analysis of megakaryoblasts growing in the presence of SDF-1 or TPO was also undertaken. The αIIbβ3+ cells expanded for 6 days (in the presence of TPO + IL-3) were transferred to cultures containing no growth factors or to cultures supplemented with TPO + IL-3, TPO, or SDF-1. Within 24 hours of withdrawal of TPO + IL-3, the number of αIIbβ3+ cells in the S and G2/M phases of the cell cycle had decreased by 20% to 30% in comparison with the cultures supplemented with TPO + IL-3 or TPO alone (not shown). More important, the number of αIIbβ3+ cells in the S and G2/M phases of the cell cycle also decreased (by approximately 20%-30%) in the cultures supplemented with SDF-1, as in the cultures depleted of TPO and IL-3 (not shown). Finally, stimulation of αIIbβ3+ cells by SDF-1 did not increase telomerase activity tested by the telomeric repeat amplification protocol assay (data not shown), as it did in the TPO-stimulated cells. These observations together suggest that, unlike what occurs in murine cells,17 SDF-1 does not affect proliferation and maturation of human megakaryoblasts.

SDF-1 does not affect survival of human αIIbβ3+ cells

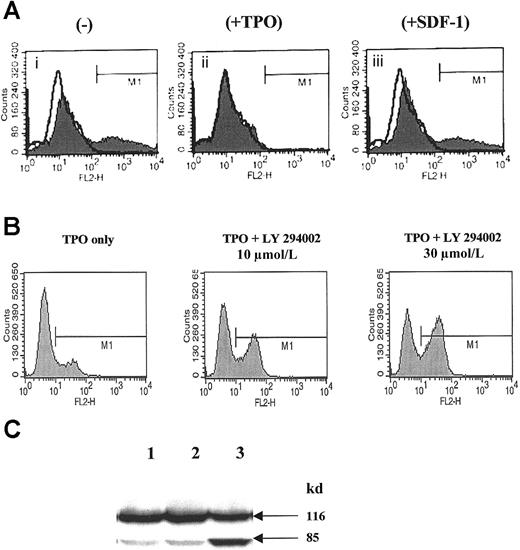

TPO is a potent antiapoptotic factor for human CD34+cells,1 erythroid progenitors,44,45 and megakaryocytic cells,1 but whether SDF-1 influences the survival of normal human αIIbβ3+ cells is unknown. To address this issue, human αIIbβ3+ cells were cultured for 12 hours in the absence or presence of TPO or SDF-1. We found that cells that were withdrawn from TPO + IL-3 underwent apoptosis after 12 hours, as evidenced by an Annexin V binding assay (Figure1Ai).46 The presence of TPO in the culture media prevented these cells from undergoing apoptosis (Figure 1Aii), but the presence of SDF-1 did not (Figure1Aiii). Megakaryoblastic cells cultured in the presence of SDF-1 bound Annexin V to the same extent as cells cultured without TPO + IL-3 (Figure 1Aiii). These data clearly indicate that SDF-1 does not maintain or enhance megakaryopoiesis.

SDF-1, in contrast to TPO, does not affect the survival of normal human αIIbβ3+ cells but activates calcium flux.

(A) Annexin V binding to human αIIbβ3+ cells cultured for 12 hours in the absence of growth factors (i), in the presence of 100 ng/mL TPO (ii), or in the presence of 500 ng/mL SDF-1 (iii). A representative experiment of 3 is demonstrated. (B) Detection of activated caspase-3 in normal human αIIbβ3+ cells cultured in the presence of TPO, TPO + LY294002 (10 μmol/L), and TPO + LY294002 (30 μmol/L). A representative experiment of 3 is demonstrated. (C) Detection of PARP cleavage in normal human αIIbβ3+ cells cultured in the presence of TPO (lane 1), TPO + DMSO (lane 2), and TPO + LY294002 (30 μmol/L) (lane 3). A representative experiment of 3 is demonstrated.

SDF-1, in contrast to TPO, does not affect the survival of normal human αIIbβ3+ cells but activates calcium flux.

(A) Annexin V binding to human αIIbβ3+ cells cultured for 12 hours in the absence of growth factors (i), in the presence of 100 ng/mL TPO (ii), or in the presence of 500 ng/mL SDF-1 (iii). A representative experiment of 3 is demonstrated. (B) Detection of activated caspase-3 in normal human αIIbβ3+ cells cultured in the presence of TPO, TPO + LY294002 (10 μmol/L), and TPO + LY294002 (30 μmol/L). A representative experiment of 3 is demonstrated. (C) Detection of PARP cleavage in normal human αIIbβ3+ cells cultured in the presence of TPO (lane 1), TPO + DMSO (lane 2), and TPO + LY294002 (30 μmol/L) (lane 3). A representative experiment of 3 is demonstrated.

Because PI-3K (a potential target for TPO signaling) plays an important role in inhibiting apoptosis in human hematopoietic cells,47-50 normal human megakaryoblasts were exposed to the PI-3K inhibitor LY294002, and we found that the inhibition of PI-3K activity resulted in increases in Annexin V binding of cells (not shown), activation of caspase-3 (Figure 1B) and PARP cleavage (Figure1C). Of note, inhibition of the MAPK p42/44 pathway by the MEK inhibitor (UO126) did not affect the survival of human megakaryoblasts (not shown).

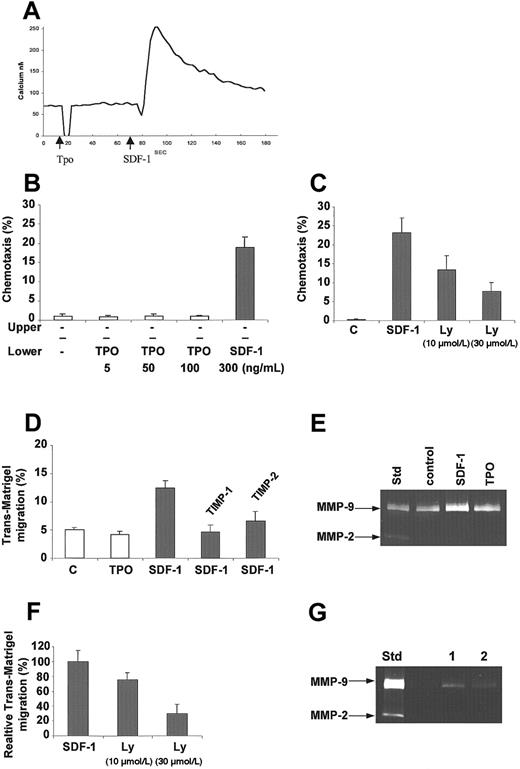

SDF-1 but not TPO induces Ca++ flux, chemotaxis, trans-Matrigel chemoattraction, MMP-9, and VEGF production

Next we extended our studies to define the roles of SDF-1 and TPO in the homing of human megakaryoblastic cells by examining their effects on chemotaxis, Ca++ fluxes, trans-Matrigel chemoattraction, and production of MMP and VEGF.

We have reported that SDF-1 induces Ca++ flux in human megakaryoblasts,10 and TPO has been shown to enhance the platelet reactivity of other agonists.51 Because the chemotactic ability of TPO had not yet been studied in human megakaryoblasts, we investigated whether TPO could induce Ca++ flux in these cells. We found that in comparison with SDF-1, which stimulated a measurable Ca++ flux in these cells, TPO added at various concentrations (physiological and high) did not (Figure 2A). Moreover, having previously shown that SDF-1 is a strong chemoattractant for human megakaryocytes,10 we examined whether TPO could attract these cells as well. We found that TPO, in contrast to SDF-1, did not attract human αIIbβ3+ cells (Figure 2B). Of note, and in agreement with a recent report,52 SDF-1–induced chemotaxis was inhibited by LY294002 (Figure 2C) but not by U0126 (not shown), suggesting the involvement of PI-3K in this process. Similarly, an SDF-1 gradient, unlike a TPO gradient, attracted αIIbβ3+ cells across the reconstituted basement membrane Matrigel (Figure 2D), and the MMP inhibitors (rhTIMP-1 and rhTIMP-2) reduced this trans-Matrigel chemotaxis by 68% ± 8% and 52% ± 11%, respectively (Figure2D), suggesting that MMPs are involved in this process. We then determined whether αIIbβ3+cells secrete MMPs, especially MMP-9 and MMP-2, and demonstrated for the first time that megakaryocytic cells constitutively secrete MMP-9 and that SDF-1 increases this secretion slightly (Figure 2E). SDF-1–induced trans-Matrigel migration and MMP-9 secretion were inhibited when cells were preincubated with LY 29002 (Figure 2F,G, respectively), suggesting the involvement of PI-3K in both processes.

SDF-1 in contrast to TPO activates calcium flux, chemotaxis, trans-Matrigel migration, and MMP-9 production in normal human αIIbβ3+ cells.

(A) Calcium flux studies of Fura-2–loaded normal human αIIbβ3+ cells. TPO (100 ng/mL) or SDF-1 (500 ng/mL) was added, and subsequently calcium flux was evaluated by a spectrophotofluorimeter. Data presented are from a representative experiment repeated 3 times and yielding similar results. (B) Normal human αIIbβ3+ cells show chemotaxis to SDF-1 but not to TPO. The experiment was repeated 3 times in duplicate. The bottom chambers contained media alone (−) or 5 to 100 ng/mL TPO or 300 ng/mL SDF-1. (C) Inhibition of SDF-1–dependent chemotaxis after preincubation of megakaryoblasts with increasing concentration of LY294002 (10 μmol/L and 30 μmol/L). The experiment was repeated 3 times in duplicate. (D) Trans-Matrigel migration of megakaryoblasts toward SDF-1 and TPO gradients and the effect of MMP inhibitors. The bottom chambers contained media alone (control, c) or 100 ng/mL each of SDF-1 or TPO. The assay was carried out twice using 4 to 5 chambers. Inhibition of trans-Matrigel migration toward SDF-1 was carried out by preincubating the megakaryoblasts for 2 hours in the absence or presence of 10 μg/mL rhTIMP-1 or rhTIMP-2. Percentages of cells that migrated after 3 hours of incubation at 37°C are shown as mean ± 1 SD. (E) MMP expression in megakaryoblasts in the presence of SDF-1 and TPO. Media conditioned by megakaryoblasts after incubation for 3 hours in the absence (control) or presence of 100 ng/mL SDF-1 or TPO were analyzed by zymography. Media conditioned by KG-1 cells were used as the standard to show the positions of the MMP-9 and MMP-2 activities in the gel. The experiment was repeated 3 times. (F) Inhibition of trans-Matrigel migration to SDF-1 after preincubation of megakaryoblasts with increasing concentration of LY294002 (10 μmol/L and 30 μmol/L). The experiment was repeated twice, using 6 chambers each. (G) MMP expression in megakaryoblasts stimulated with SDF-1 without (lane 1) or with (lane 2) LY294002. The experiment was repeated 2 times.

SDF-1 in contrast to TPO activates calcium flux, chemotaxis, trans-Matrigel migration, and MMP-9 production in normal human αIIbβ3+ cells.

(A) Calcium flux studies of Fura-2–loaded normal human αIIbβ3+ cells. TPO (100 ng/mL) or SDF-1 (500 ng/mL) was added, and subsequently calcium flux was evaluated by a spectrophotofluorimeter. Data presented are from a representative experiment repeated 3 times and yielding similar results. (B) Normal human αIIbβ3+ cells show chemotaxis to SDF-1 but not to TPO. The experiment was repeated 3 times in duplicate. The bottom chambers contained media alone (−) or 5 to 100 ng/mL TPO or 300 ng/mL SDF-1. (C) Inhibition of SDF-1–dependent chemotaxis after preincubation of megakaryoblasts with increasing concentration of LY294002 (10 μmol/L and 30 μmol/L). The experiment was repeated 3 times in duplicate. (D) Trans-Matrigel migration of megakaryoblasts toward SDF-1 and TPO gradients and the effect of MMP inhibitors. The bottom chambers contained media alone (control, c) or 100 ng/mL each of SDF-1 or TPO. The assay was carried out twice using 4 to 5 chambers. Inhibition of trans-Matrigel migration toward SDF-1 was carried out by preincubating the megakaryoblasts for 2 hours in the absence or presence of 10 μg/mL rhTIMP-1 or rhTIMP-2. Percentages of cells that migrated after 3 hours of incubation at 37°C are shown as mean ± 1 SD. (E) MMP expression in megakaryoblasts in the presence of SDF-1 and TPO. Media conditioned by megakaryoblasts after incubation for 3 hours in the absence (control) or presence of 100 ng/mL SDF-1 or TPO were analyzed by zymography. Media conditioned by KG-1 cells were used as the standard to show the positions of the MMP-9 and MMP-2 activities in the gel. The experiment was repeated 3 times. (F) Inhibition of trans-Matrigel migration to SDF-1 after preincubation of megakaryoblasts with increasing concentration of LY294002 (10 μmol/L and 30 μmol/L). The experiment was repeated twice, using 6 chambers each. (G) MMP expression in megakaryoblasts stimulated with SDF-1 without (lane 1) or with (lane 2) LY294002. The experiment was repeated 2 times.

Because normal human megakaryoblasts have been shown to secrete VEGF15,16 and because endogenously secreted VEGF plays an important role in the transendothelial migration of megakaryocytes,15 we next evaluated whether SDF-1 or TPO has any effect on the secretion of VEGF by normal human αIIbβ3+ cells. Table3 shows that SDF-1, but not TPO, significantly stimulates the secretion of VEGF by these cells. Cells that have been preincubated with LY294002, but not with U0126, did not respond to SDF-1 stimulation with increased VEGF secretion (not shown).

Effects of SDF-1 and TPO on VEGF secretion by human megakaryoblasts (106 cells/mL) cultured for 24 hours in serum-free medium

Each data entry consists of 2 independent measurements from 3 different donors. Data shown are mean ± 1 SD.*

SDF-1 indicates stromal-derived factor 1; TPO, thrombopoietin; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Sensitivity of the ELISA assay for VEGF was > 5 pg/mL.

P < .0001 compared to (−) and TPO.

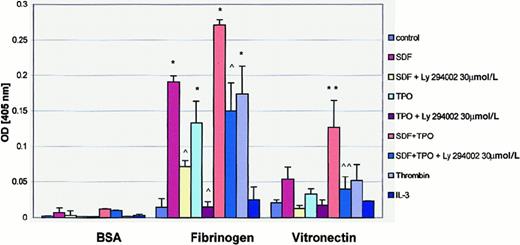

SDF-1 and TPO activate αIIbβ3 and αVβ3 integrins and adhesion of human megakaryoblasts to fibrinogen and vitronectin

Adhesion to extracellular ligands is an important step in megakaryocyte migration. Using the PAC-1 binding assay,38we demonstrated that both SDF-1 and TPO activate αIIbβ3 integrin on human megakaryoblasts (data not shown), which is consistent with previous findings by others that TPO enhances platelet reactivity51 and with our recent observations that SDF-1 also stimulates it.53 Consistent with these observations, we found that both SDF-1 and TPO increased the adherence of αIIbβ3 cells to fibrinogen (Figure 3). Both cytokines, if added together, also induced adhesiveness to vitronectin (Figures 3,4). Of note, adhesion of human megakaryoblasts was inhibited when the cells were pretreated with the PI-3K inhibitor, suggesting again the involvement of PI-3K in this process. Interestingly, the adhesion of human differentiating αIIbβ3+ cells to fibronectin and VCAM-1 was weak and not affected by SDF-1 or TPO (data not shown). Thus, it appears that both SDF-1 and TPO increase the adhesion of megakaryoblasts to their microenvironment.

SDF-1 and TPO stimulate adhesion of normal human αIIbβ3+ cells to fibrinogen and vitronectin.

Adhesion was measured to BSA- (control), fibrinogen-, and vitronectin-coated microtiter plates. Cells in the adhesion assay were nonstimulated (control) or stimulated with 500 ng/mL SDF-1, 100 ng/mL TPO, 500 ng SDF-1 + 100 ng TPO, 2 U/mL thrombin, or 100 ng/mL IL-3. The number of cells stuck to the plates was quantified by colorimetric phosphatase assay. Y axis: OD values at 405 nm. Experiments were repeated 3 times in triplicate, yielding similar results. * and **P < .0001 compared to control. ^ and ^^P < .0001 compared to cells untreated with LY294002.

SDF-1 and TPO stimulate adhesion of normal human αIIbβ3+ cells to fibrinogen and vitronectin.

Adhesion was measured to BSA- (control), fibrinogen-, and vitronectin-coated microtiter plates. Cells in the adhesion assay were nonstimulated (control) or stimulated with 500 ng/mL SDF-1, 100 ng/mL TPO, 500 ng SDF-1 + 100 ng TPO, 2 U/mL thrombin, or 100 ng/mL IL-3. The number of cells stuck to the plates was quantified by colorimetric phosphatase assay. Y axis: OD values at 405 nm. Experiments were repeated 3 times in triplicate, yielding similar results. * and **P < .0001 compared to control. ^ and ^^P < .0001 compared to cells untreated with LY294002.

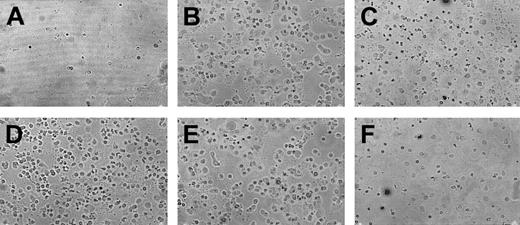

Adherence of human αIIbβ3+ cells to fibrinogen.

Representative photographs showing adherence of normal human αIIbβ3+ cells to fibrinogen. Cells were not exposed (A) or were exposed (B) to SDF-1, TPO (C), SDF-1 + TPO (D), thrombin (E), or IL-3 (F). Experiment was repeated 3 times in triplicate and yielded similar results.

Adherence of human αIIbβ3+ cells to fibrinogen.

Representative photographs showing adherence of normal human αIIbβ3+ cells to fibrinogen. Cells were not exposed (A) or were exposed (B) to SDF-1, TPO (C), SDF-1 + TPO (D), thrombin (E), or IL-3 (F). Experiment was repeated 3 times in triplicate and yielded similar results.

Phosphorylation of MAPK (p42/44 and p38) and AKT in normal human megakaryoblasts is induced by SDF-1 and TPO

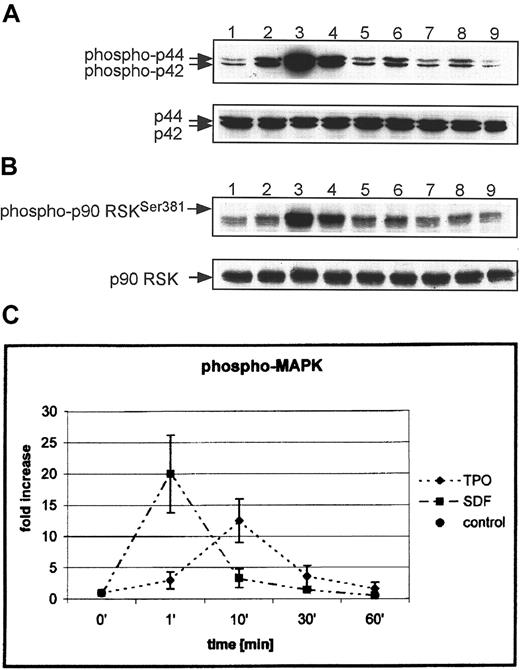

To explain the molecular basis of the different biologic effects of SDF-1 and TPO, we examined the intracellular signaling pathways induced by these cytokines in human megakaryocytic cells. It has been reported that the intracellular kinase MAPK p42/44 is phosphorylated in human cell lines, platelets, and murine megakaryoblasts after stimulation by both TPO or SDF-1.23-26 In this study, we examined the MAP kinases (p42/44, p38, and JNK) that have been reported to play an important role in regulating cell proliferation,54 including the intensity and kinetics of their activation in normal human megakaryoblasts. We found that both SDF-1 and TPO induced strong phosphorylation of MAPK p42/44 (Figure5A); however, after stimulation with SDF-1, it was phosphorylated faster than with TPO (peak at 1 minute for SDF-1 vs 10 minutes for TPO) and more intensely (21- ± 6- vs 11- ± 3-fold increases, respectively) (Figure 5C). We correctly predicted that the activation of MAPK p42/44 should lead to phosphorylation of several MAPK substrates (p90 RSK and ELK-1), and this was confirmed for p90 RSK (Figure 5B) and ELK-1 (not shown). Again, though both SDF-1 and TPO stimulated strong phosphorylation of both substrates, SDF-1 induced an earlier and more intense response.

SDF-1 and TPO activate MAPK (p42/44) and p90 RSK in normal human αIIbβ3+ cells.

Western blot analysis of MAPK phosphorylation (A) and p90 RSK (B) in normal human αIIbβ3+ cells. Cells were nonstimulated (lane 1) or stimulated with 100 ng/mL TPO (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8) or 500 ng/mL SDF-1 (lane 3, 5, 7, 9) for 1 minute (lanes 2, 3), 10 minutes (lanes 4, 5), 30 minutes (lanes 6, 7), and 1 hour (lanes 8, 9). Equal loading in the lanes was evaluated by stripping the blot and reprobing with an anti-MAPK (p42/44) antibody or anti-p90 RSK antibody. (C) Densitometric data showing changes in MAPK p42/44 phosphorylation. The experiment was repeated 5 times for MAPK p42/44 and 3 times for p90 RSK with similar results. Data are presented from 5 independent experiments.

SDF-1 and TPO activate MAPK (p42/44) and p90 RSK in normal human αIIbβ3+ cells.

Western blot analysis of MAPK phosphorylation (A) and p90 RSK (B) in normal human αIIbβ3+ cells. Cells were nonstimulated (lane 1) or stimulated with 100 ng/mL TPO (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8) or 500 ng/mL SDF-1 (lane 3, 5, 7, 9) for 1 minute (lanes 2, 3), 10 minutes (lanes 4, 5), 30 minutes (lanes 6, 7), and 1 hour (lanes 8, 9). Equal loading in the lanes was evaluated by stripping the blot and reprobing with an anti-MAPK (p42/44) antibody or anti-p90 RSK antibody. (C) Densitometric data showing changes in MAPK p42/44 phosphorylation. The experiment was repeated 5 times for MAPK p42/44 and 3 times for p90 RSK with similar results. Data are presented from 5 independent experiments.

We next tested whether other members of the MAPK family (p38, JNK) are activated in αIIbβ3+ cells by either TPO or SDF-1. To address this question, αIIbβ3+ cells were made quiescent by BSA starvation and subsequently were stimulated with TPO or SDF-1; p38 was phosphorylated by both TPO and SDF-1, though the phosphorylation was found to be 3 times more intense after stimulation with SDF-1 (data not shown). In contrast, JNK showed no change in phosphorylation in αIIbβ3+cells stimulated by either TPO or SDF-1 (not shown).

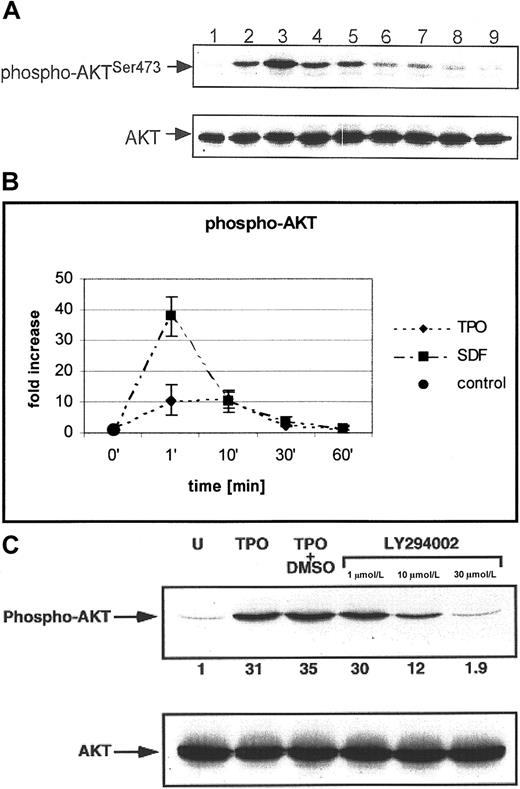

AKT is a serine-threonine kinase that plays an important role in the phosphorylation of several antiapoptotic proteins that may be key to normal hematopoiesis.47-50 It has been reported that integrin stimulation of human αIIbβ3+ cells results in the phosphorylation of AKT,26 but whether TPO stimulates AKT as part of its antiapoptotic effect and how this differs from SDF-1 have not been investigated. Examining the kinetics of AKT phosphorylation in megakaryoblastic cells (Figure6), we observed that AKT is already phosphorylated 1 minute after stimulation by either TPO or SDF-1; however, SDF-1 phosphorylated AKT approximately 3 times more intensely than TPO (36- ± 8- vs 10- ± 4-fold increases, respectively). Moreover, LY294002 abolished SDF-1– or TPO-induced AKT phosphorylation, suggesting that AKT phosphorylation is PI-3K dependent (Figure 6C). Hence, it appears that though intracellular signaling through the c-mpl and the CXCR4 receptors overlaps and leads to phosphorylation of AKT with the same kinetics, one results in an antiapoptotic effect and the other does not. Whether the degree of phosphorylation by the 2 agonists is responsible for the observed difference or whether TPO and SDF-1 differently activate other proteins related to PI-3K–AKT axis requires further analysis.

SDF-1 and TPO phosphorylate AKT in normal human αIIbβ3+ cells in a PI-3K–dependent manner.

(A) Western blot analysis of AKT phosphorylation (upper panel) in normal human αIIbβ3+ cells. Cells were nonstimulated (lane 1) or stimulated with 100 ng/mL TPO (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8) or 500 ng/mL of SDF-1 (lanes 3, 5, 7, 9) for 1 minute (lanes 2, 3), 10 minutes (lanes 4, 5), 30 minutes (lanes 6, 7), and 1 hour (lanes 8, 9). Equal loading in the lanes was evaluated by stripping the blot and reprobing with an anti-AKT antibody (lower panel). (B) Densitometric data showing changes in AKT phosphorylation. The experiment was repeated 5 times with similar results. Data are presented from 5 independent experiments. (C) Normal human αIIbβ3+ cells were pretreated with LY294002 and then stimulated with TPO (100 ng/mL) or SDF-1 (500 ng/mL) (not shown). phospho-AKT (upper panel); total AKT (lower panel). The experiment was repeated 3 times with similar results.

SDF-1 and TPO phosphorylate AKT in normal human αIIbβ3+ cells in a PI-3K–dependent manner.

(A) Western blot analysis of AKT phosphorylation (upper panel) in normal human αIIbβ3+ cells. Cells were nonstimulated (lane 1) or stimulated with 100 ng/mL TPO (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8) or 500 ng/mL of SDF-1 (lanes 3, 5, 7, 9) for 1 minute (lanes 2, 3), 10 minutes (lanes 4, 5), 30 minutes (lanes 6, 7), and 1 hour (lanes 8, 9). Equal loading in the lanes was evaluated by stripping the blot and reprobing with an anti-AKT antibody (lower panel). (B) Densitometric data showing changes in AKT phosphorylation. The experiment was repeated 5 times with similar results. Data are presented from 5 independent experiments. (C) Normal human αIIbβ3+ cells were pretreated with LY294002 and then stimulated with TPO (100 ng/mL) or SDF-1 (500 ng/mL) (not shown). phospho-AKT (upper panel); total AKT (lower panel). The experiment was repeated 3 times with similar results.

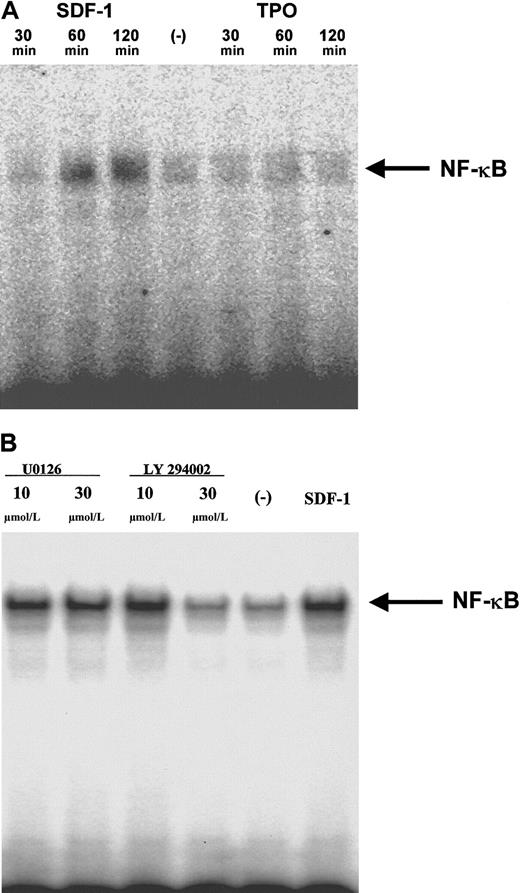

AKT is also involved in the activation of NF-κB, a regulator of gene transcription.42,49 Because NF-κB regulates the expression of MMP-9 and VEGF,54 55 and, as we have shown above, the secretion of both these factors was up-regulated after stimulation by SDF-1 (Figure 2D, Table 3, respectively), we hypothesized that SDF-1 might influence NF-κB activation. As predicted, using EMSA, we detected biologically active NF-κB in nuclear extracts isolated from normal human megakaryoblastic cells stimulated by SDF-1 (Figure 7A). At the same time, we established that TPO did not influence NF-κB activation. We also observed that the activation of NF-κB by SDF-1 was PI-3K but not MEK dependent in human megakaryoblasts (Figure 7B).

SDF-1, but not TPO, stimulates NF-κB activation in human αIIbβ3+ cells in a PI-3K–dependent manner.

(A) Normal human αIIbβ3+ cells were made quiescent and subsequently were stimulated with 300 ng/mL SDF-1 (lanes 1, 2, 3) or 100 ng/mL TPO (lanes 5, 6, 7). EMSA was performed with cell nuclear extracts from cells stimulated with SDF-1 for 30 minutes (lane 1), 60 minutes (lane 2), 120 minutes (lane 3), nonstimulated (lane 4), or stimulated with TPO for 30 minutes (lane 5), 60 minutes (lane 6), and 120 minutes (lane 7). A representative autoradiogram of 2 separate experiments is shown. (B) Normal human αIIbβ3+ cells were made quiescent and then were pretreated with 10 μmol/L or 30 μmol/L (lanes 1 and 2) of MEK inhibitor U0126 or 10 μmol/L or 30 μmol/L PI-3K inhibitor LY294002 (lanes 3 and 4) and stimulated with 300 ng/mL SDF-1. Control, cells pretreated but not stimulated with SDF-1 (lane 5), cells not pretreated but stimulated with SDF-1 (lane 6). EMSA was performed with nuclear extracts from cells stimulated with SDF-1 for 90 minutes. A representative autoradiogram of 2 separate experiments is shown.

SDF-1, but not TPO, stimulates NF-κB activation in human αIIbβ3+ cells in a PI-3K–dependent manner.

(A) Normal human αIIbβ3+ cells were made quiescent and subsequently were stimulated with 300 ng/mL SDF-1 (lanes 1, 2, 3) or 100 ng/mL TPO (lanes 5, 6, 7). EMSA was performed with cell nuclear extracts from cells stimulated with SDF-1 for 30 minutes (lane 1), 60 minutes (lane 2), 120 minutes (lane 3), nonstimulated (lane 4), or stimulated with TPO for 30 minutes (lane 5), 60 minutes (lane 6), and 120 minutes (lane 7). A representative autoradiogram of 2 separate experiments is shown. (B) Normal human αIIbβ3+ cells were made quiescent and then were pretreated with 10 μmol/L or 30 μmol/L (lanes 1 and 2) of MEK inhibitor U0126 or 10 μmol/L or 30 μmol/L PI-3K inhibitor LY294002 (lanes 3 and 4) and stimulated with 300 ng/mL SDF-1. Control, cells pretreated but not stimulated with SDF-1 (lane 5), cells not pretreated but stimulated with SDF-1 (lane 6). EMSA was performed with nuclear extracts from cells stimulated with SDF-1 for 90 minutes. A representative autoradiogram of 2 separate experiments is shown.

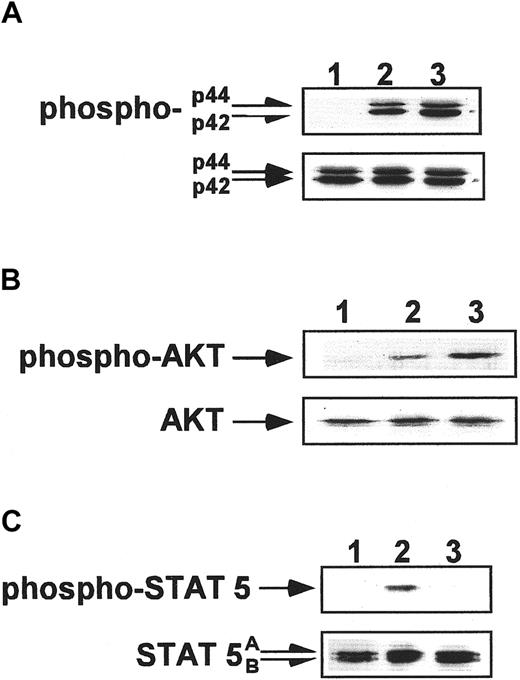

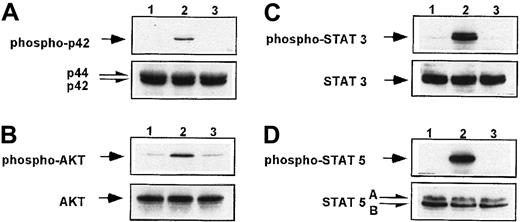

SDF-1 induces phosphorylation of MAPK p42/44 and AKT in human CD34+ cells but not in platelets

We also investigated the responsiveness of CD34+ cells and circulating platelets to stimulation by SDF-1 or TPO. Examining CD34+ cells, we found that though both factors induced the phosphorylation of MAPK p42/44 and AKT (Figure8A,B), only TPO stimulated the proliferation of these cells (Table 1) and, as reported previously, protected them from undergoing apoptosis.1 44 This observation again suggests that SDF-1 is not primarily directed toward maintaining or enhancing cell proliferation. In contrast to CD34+ and αIIbβ3+cells, the stimulation of human platelets by SDF-1 under similar conditions did not lead to phosphorylation of MAPK p42/44 and AKT (Figure 9A,B). This observation supports our hypothesis that the responsiveness of CXCR4 to stimulation by SDF-1 (phosphorylation of MAPK p42/44, and AKT) decreases in the final stages of megakaryocytopoiesis–thrombocytopoiesis. In contrast, TPO stimulation of human platelets resulted in the phosphorylation of MAPK p42 and AKT (Figure 9).

Phosphorylation studies of CD34+ cells.

Western blot analysis of MAPK p42/44 phosphorylation (A), AKT phosphorylation (B), and STAT-5 phosphorylation (C) in normal human CD34+ cells. Cells were nonstimulated (lane 1) or stimulated for 10 minutes by 100 ng/mL TPO (lane 2) or for 1 minute by 500 ng/mL SDF-1 (lane 3). Equal loading in the lanes was evaluated by stripping the blot and reprobing with anti-MAPK p42/44, AKT, and STAT-5 antibodies (lower panels). The experiment was repeated 3 times with similar results.

Phosphorylation studies of CD34+ cells.

Western blot analysis of MAPK p42/44 phosphorylation (A), AKT phosphorylation (B), and STAT-5 phosphorylation (C) in normal human CD34+ cells. Cells were nonstimulated (lane 1) or stimulated for 10 minutes by 100 ng/mL TPO (lane 2) or for 1 minute by 500 ng/mL SDF-1 (lane 3). Equal loading in the lanes was evaluated by stripping the blot and reprobing with anti-MAPK p42/44, AKT, and STAT-5 antibodies (lower panels). The experiment was repeated 3 times with similar results.

SDF-1, in contrast to TPO, does not phosphorylate MAPK, AKT, and STAT proteins in human platelets.

Western blot analysis of MAPK p42/44 phosphorylation (A), AKT phosphorylation (B), STAT-3 (Tyr 705) (C), and STAT-5 (D) phosphorylation in normal human peripheral blood platelets. Platelets were nonstimulated (lane 1) or stimulated for 10 minutes by 100 ng/mL TPO (lane 2) or for 1 minute by 500 ng/mL SDF-1 (lane 3). Equal loading in the lanes was evaluated by stripping the blot and reprobing with anti-MAPK p42/44, AKT, and STAT-5 antibodies. The experiment was repeated 3 times with similar results.

SDF-1, in contrast to TPO, does not phosphorylate MAPK, AKT, and STAT proteins in human platelets.

Western blot analysis of MAPK p42/44 phosphorylation (A), AKT phosphorylation (B), STAT-3 (Tyr 705) (C), and STAT-5 (D) phosphorylation in normal human peripheral blood platelets. Platelets were nonstimulated (lane 1) or stimulated for 10 minutes by 100 ng/mL TPO (lane 2) or for 1 minute by 500 ng/mL SDF-1 (lane 3). Equal loading in the lanes was evaluated by stripping the blot and reprobing with anti-MAPK p42/44, AKT, and STAT-5 antibodies. The experiment was repeated 3 times with similar results.

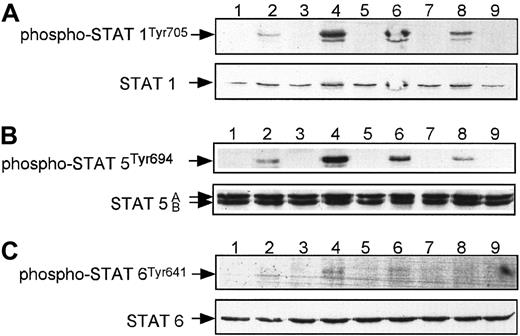

SDF-1, in contrast to TPO, does not induce tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT family proteins in human megakaryoblasts

Despite the fact that the stimulation of human αIIbβ3+ cells with SDF-1 led to the phosphorylation of MAPK p42/44, p38 and the nuclear protein ELK-1, SDF-1 (as shown above) had no effect on the proliferation or maturation of normal human megakaryoblasts. To understand the molecular basis of these findings, we looked at the activation of the JAK-STAT pathways in normal human αIIbβ3+ cells. STAT proteins have been shown to play an important role in regulating cell proliferation5,21,27,54 and in signaling from the activated c-mpl receptor in various hematopoietic cell lines1,27 and normal human platelets.22,23 In particular, the stimulation of human platelets by TPO led to the phosphorylation of STAT-1, STAT-2, STAT-3, and STAT-5 proteins28 and of STAT-3 and STAT-5 in FDCP-2 cells genetically engineered to constitutively express human c-mpl.27 However, the effects of SDF-1 on the phosphorylation of STAT proteins in human megakaryocytic cells have not been studied.

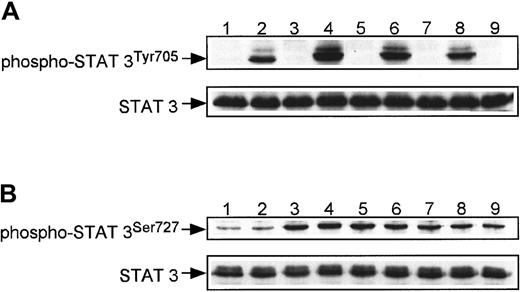

We focused our studies on the phosphorylation of STAT-1 and STAT-3 at both Tyr705 and Ser727 and of STAT-5 and STAT-6 (Figures10, 11) in human megakaryocytes, and we found that among these proteins, only STAT-3 at Ser727 was phosphorylated after stimulation by SDF-1 (Figure11B). TPO, however, caused phosphorylation of all the STAT proteins tested (Figures 10, 11), consistent with previous studies of human blood platelets.28 29 The phosphorylation of STAT proteins was maximal 10 minutes after stimulation by TPO. The fact that multiple STAT proteins were not phosphorylated in αIIbβ3+ cells after stimulation by SDF-1 may provide a molecular explanation as to why SDF-1, in contrast to TPO, does not affect the proliferation of human megakaryocytic cells.

SDF-1, in contrast to TPO, does not phosphorylate STAT-1, STAT-5, or STAT-6 in normal human αIIbβ3+ cells.

Western blot analysis of STAT-1 phosphorylation (A), STAT-5 phosphorylation (B), and STAT-6 phosphorylation (C) in normal human αIIbβ3+ cells. Cells were nonstimulated (lane 1) or stimulated with 100 ng/mL TPO (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8) or 500 ng/mL SDF-1 (lanes 3, 5, 7, 9) for 1 minute (lanes 2, 3),10 minutes (lanes 4, 5), 30 minutes (lanes 6, 7), and 1 hour (lanes 8, 9). Equal loading in the lanes was evaluated by stripping the blot and reprobing with an anti–STAT-1, anti–STAT-5, or anti–STAT-6 antibody. The experiment was repeated 3 times with similar results.

SDF-1, in contrast to TPO, does not phosphorylate STAT-1, STAT-5, or STAT-6 in normal human αIIbβ3+ cells.

Western blot analysis of STAT-1 phosphorylation (A), STAT-5 phosphorylation (B), and STAT-6 phosphorylation (C) in normal human αIIbβ3+ cells. Cells were nonstimulated (lane 1) or stimulated with 100 ng/mL TPO (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8) or 500 ng/mL SDF-1 (lanes 3, 5, 7, 9) for 1 minute (lanes 2, 3),10 minutes (lanes 4, 5), 30 minutes (lanes 6, 7), and 1 hour (lanes 8, 9). Equal loading in the lanes was evaluated by stripping the blot and reprobing with an anti–STAT-1, anti–STAT-5, or anti–STAT-6 antibody. The experiment was repeated 3 times with similar results.

SDF-1 phosphorylates STAT-3 at Ser727 but not at Tyr705 in αIIbβ3+ cells.

Western blot analysis of STAT-3 phosphorylation at Tyr705 (A) and at Ser727 (B) in normal human αIIbβ3+ cells. Cells were nonstimulated (lane 1) or stimulated with 100 ng/mL TPO (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8) or 500 ng/mL SDF-1 (lanes 3, 5, 7, 9) for 1 minute (lanes 2, 3), 10 minutes (lanes 4, 5), 30 minutes (lanes 6, 7), and 1 hour (lanes 8, 9). Equal loading in the lanes was evaluated by stripping the blot and reprobing with an anti–STAT-3 antibody. The experiment was repeated 3 times with similar results.

SDF-1 phosphorylates STAT-3 at Ser727 but not at Tyr705 in αIIbβ3+ cells.

Western blot analysis of STAT-3 phosphorylation at Tyr705 (A) and at Ser727 (B) in normal human αIIbβ3+ cells. Cells were nonstimulated (lane 1) or stimulated with 100 ng/mL TPO (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8) or 500 ng/mL SDF-1 (lanes 3, 5, 7, 9) for 1 minute (lanes 2, 3), 10 minutes (lanes 4, 5), 30 minutes (lanes 6, 7), and 1 hour (lanes 8, 9). Equal loading in the lanes was evaluated by stripping the blot and reprobing with an anti–STAT-3 antibody. The experiment was repeated 3 times with similar results.

SDF-1, in contrast to TPO, does not induce tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT proteins in human CD34+ cells and platelets

Finally, we investigated the responsiveness of both human CD34+ cells and circulating platelets to stimulation by SDF-1 or TPO. We found that only TPO stimulated the phosphorylation of STAT-5 (Figures 8C, 9D) and STAT-3 at Tyr705 (Figure 9C) in these cells. This finding for human CD34+cells (Figure 8C) may also explain why TPO, but not SDF-1, stimulates the proliferation of CD34+ cells.

Discussion

Data on CXCR4 or SDF-1 knockout mice1,3,4 and recent findings suggesting that SDF-1 enhances the effect of TPO9,17 on megakaryocyte formation indicate a potential role for SDF-1 in megakaryopoiesis. However, our previous work10 and that of others11 provided evidence that though SDF-1 stimulated homing features in human megakaryocytic progenitors, it did not influence CFU-MK formation and growth. These observations prompted us to compare the effects of SDF-1 with those of TPO on development and activation of human megakaryocytic cells and to study the intracellular signaling pathways activated by these cytokines to better define the molecular basis for the observed differences. We found that the stimulation of human CD34+ cells and megakaryoblasts by SDF-1 does not influence proliferation, apoptosis, or telomerase activity, even when the SDF-1 is added with TPO. Hence, our data collectively suggest that, unlike TPO, SDF-1 is not a megakaryopoietic growth factor. This agrees with a recent report demonstrating lack of a proliferative effect by SDF-1 on CFU-MK formation from human CD34+ cells.11 However, it does not support recent observations on a murine model suggesting that SDF-1 acts together with TPO to enhance the development of CFU-MK17 and that SDF-1 at low doses enhances the proliferation of peripheral blood CD34+cells.43 We suggest that this difference in results may be due to the different culture systems used (serum-free medium vs serum-supplemented medium) or to the different target cells (human vs murine marrow cells).

We next evaluated the role of SDF-1 and TPO in the homing of human megakaryoblastic cells. We found that TPO, in contrast to SDF-1, does not induce Ca++ flux and is not a chemoattractant for human αIIbβ3+ cells. We also demonstrated that human megakaryoblasts secrete MMP-9 constitutively and that SDF-1 slightly up-regulates it. Moreover, trans-Matrigel chemotaxis of megakaryoblasts to an SDF-1 gradient was decreased by the tissue inhibitors of MMPs rhTIMP-1 and rhTIMP-2. We also found that the stimulation of normal human megakaryoblasts by SDF-1, but not by TPO, increases endogenous secretion of VEGF by these cells. Because VEGF up-regulates the expression of E-selectin on human endothelium,15 we postulate that VEGF endogenously secreted by megakaryocytic cells may play an important role in the interaction of megakaryocytes with endothelium,55,56 their egress from the bone marrow, and proplatelet formation.16Adhesion of human megakaryoblasts to fibrinogen and vitronectin was also increased by SDF-1, and both agonists were synergistic in activating binding of the latter. This supports the hypothesis that both SDF-1 and TPO may regulate the adhesiveness of megakaryoblasts in the hematopoietic microenvironment by activating αIIbβ3 and αvβ3integrins. Our data are also consistent with a recent report showing that SDF-1 activates integrins (α4β1 and αLβ2) on the surfaces of human CD34+ cells.57 Collectively, our data indicate that the homing of immature megakaryoblasts in bone marrow and egress of platelet-releasing megakaryocytes through the endothelial layer and subendothelial basement membranes may be regulated by changes in or responsiveness to an SDF-1 gradient.9-11

To find an explanation at the molecular level for the differences in the biologic effects of SDF-1 and TPO, we investigated signal transduction pathways activated in normal human megakaryoblasts by these cytokines. First, we found that the stimulation of human αIIbβ3+ cells by both TPO and SDF-1 leads to the phosphorylation of the kinases MAPK p42/44 and p38 and their downstream targets (p90 RSK and ELK-1). However, we found a clear difference in the kinetics and possibly in the intensity of stimulation of megakaryoblasts by these 2 cytokines. This may be related to previous observations that signaling pathways from G-protein–coupled CXCR receptors are activated faster7,8,54 than those from the cytokine-type c-mpl receptor.1

AKT has been reported to be important in preventing apoptosis during hematopoiesis.47-50 In agreement with this observation, we have now demonstrated that AKT is phosphorylated in normal human megakaryoblasts after stimulation by both SDF-1 and TPO in a PI-3K–dependent manner and that the inhibition of PI-3K activity by LY294002 induced apoptosis in these cells. However, though both factors activate the PI-3K–AKT axis, our in vitro data showed that only TPO protected αIIbβ3+ cells from apoptosis; SDF-1 had no effect on their survival. We therefore postulate that SDF-1–driven activation of the PI-3K–AKT axis does not lead to activation of the appropriate antiapoptotic pathways. We suggest that TPO and SDF-1 differentially activate other proteins related to the PI-3K–AKT axis. A report showing that activation of AKT does not always lead to phosphorylation and inactivation of proapoptotic BAD supports this hypothesis.58 Based on these results, we postulate the simultaneous activation of other pathways by TPO in normal human megakaryoblasts that are central to preventing apoptosis of αIIbβ3+cells. We are currently investigating this in our laboratory. Moreover, we found that NF-κB, which is one of the PI-3K–AKT axis downstream-regulated proteins, is activated after stimulation by SDF-1. The fact that NF-κB regulates the expression of MMP-959and VEGF60 explains why the stimulation of normal human megakaryoblasts by SDF-1 leads to increased endogenous MMP-9 and VEGF secretion.

Because TPO has been shown to be crucial for the proliferation and differentiation of developing murine megakaryocytes through JAK-STAT pathways,24,27 we investigated whether similar pathways are activated after SDF-1 stimulation. Identification of these pathways could shed more light on the regulation of proliferation of normal human megakaryocytic cells and explain at a molecular level why TPO and not SDF-1, as demonstrated in this study, stimulated the proliferation of these cells. We found that only STAT-3 was phosphorylated at the serine residue (Ser727) after SDF-1 stimulation, in contrast to much of the STAT family of proteins, which are phosphorylated by TPO at tyrosine residues in megakaryocytic cells.27-29 Because it has been suggested that the phosphorylation of STAT-3 at Ser727 may play a role in the down-regulation of STAT-3 protein activation,61 the phosphorylation of STAT-3 at Ser727 by SDF-1 suggests that it may down-regulate STAT-3 in normal human megakaryoblasts. Hence, we suggest that the tyrosine phosphorylation of JAK-STAT proteins probably plays a crucial role in the proliferation of megakaryocytic cells after TPO stimulation but that activation of the MAPK p42/44 and p38 pathways is not an important intermediate step in the proliferation of these cells given that SDF-1 also activates them. Of note, we found that the inhibition of MEK by UO126 affected neither survival nor proliferation of human megakaryoblasts. These data are consistent with recent studies showing that the MAPK p42/44 pathway is not required for megakaryoblast formation, though it may regulate the transition from proliferation to maturation in this lineage.21 24

In contrast, the phosphorylation of MAPK p42/44, p38, and AKT after stimulation with SDF-1 does not occur in human platelets, and we find this intriguing. We suggest that the differences between human megakaryoblasts and platelets in the composition of G and RGS proteins, coupled to the particular chemokine receptor, could explain these differences.62

In summary, we demonstrated that though both TPO and SDF-1 are important in megakaryopoiesis and stimulate some of the same intracellular pathways, they have distinct biologic effects on human megakaryocytic cells. SDF-1, but not TPO, regulates some steps in the migration of these cells in the hematopoietic microenvironment (eg, chemotaxis and secretion of MMP-9 and VEGF). In contrast, TPO, but not SDF-1, permits growth of megakaryocyte precursors (eg, by enhancing proliferation and by inhibiting apoptosis); both factors regulate their adhesion. Hence, this study sheds light on the relation between 2 distinct cytokine axes critical in human megakaryopoiesis and the molecular basis of the observed differences in cellular responses.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 HL61796-01 (M.Z.R., M.A.K., and M.P.), Leukemia and Lymphoma Society grant 64907-00 (M.Z.R.), and Canadian Blood Services Research and Development grant XE 0004 (A.J.-W.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Mariusz Z. Ratajczak, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, 405A Stellar Chance Labs, 422 Curie Blvd, Philadelphia PA 19104; e-mail: mariusz@mail.med.upenn.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal