Abstract

Thromboxane A2 is a potent vasoconstrictor and platelet agonist; prostacyclin is a potent platelet inhibitor and vasodilator. Altered biosynthesis of these eicosanoids is a feature of human hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis. This study examined whether in 2 murine models of atherosclerosis their levels are increased and correlated with the evolution of the disease. Urinary 2,3-dinor thromboxane B2 and 2,3-dinor-6-keto prostaglandin F1α, metabolites of thromboxane and prostacyclin, respectively, were assayed in apoliprotein E (apoE)-deficient mice on chow and low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR)-deficient mice on chow and a Western-type diet. Atherosclerosis lesion area was measured by en face method. Both eicosanoids increased in apoE-deficient mice on chow and in LDLR-deficient mice on a high-fat diet, but not in LDLR-deficient mice on chow by the end of the study. Aspirin suppressed ex vivo platelet aggregation, serum thromboxane B2, and 2,3-dinor thromboxane B2, and significantly reduced the excretion of 2,3-dinor-6-keto prostaglandin F1α in these animals. This study demonstrates that thromboxane as well as prostacyclin biosynthesis is increased in 2 murine models of atherogenesis and is secondary to increased in vivo platelet activation. Assessment of their generation in these models may afford the basis for future studies on the functional role of these eicosanoids in the evolution and progression of atherosclerosis.

Introduction

Increased platelet activation in vivo plays a central role in the initiation of arterial thrombosis and, through the release of mitogenic factors and vasoactive compounds, it is thought to contribute to the development of atherosclerosis.1Thromboxane (Tx) A2 is a potent vasoconstrictor and platelet aggregating agent, released from activated platelets and produced by the metabolism of arachidonic acid through the cyclooxygenase pathway.2 Its formation by and action on platelets has been implicated in cardiovascular disease only by the observation that aspirin, an inhibitor of TxA2 synthesis, and thromboxane receptor antagonists result in significant benefit compared with placebo treatment.3,4 In addition, the capacity of the endothelium to generate prostacyclin (prostaglandin I2 [PGI2]), a potent platelet inhibitor and vasodilator, has also been reported to be altered in atherosclerosis.5,6 Atherosclerosis is a multifactorial disease and, in the recent past, the introduction of transgenic animal models that reproduce this disease has been extremely important in investigating some of the complex cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in its initiation and progression.7 8 To date, no data are available on whether TxA2 and PGI2biosynthesis are altered in any transgenic mouse models of atherosclerosis.

In this study, we examined in vivo TxA2 and PGI2 formation in 2 different murine models of this disease, the apolipoprotein E (apoE)-deficient (apoE−/−) and the low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient (LDLR−/−) mice, by a highly specific noninvasive method—measurement of its urinary metabolites 2,3-dinor TxB2 and 2,3- dinor-6-keto prostaglandin F1α(PGF1α). We demonstrate that both are altered and provide evidence that in vivo platelet activation plays an important role in such an increase.

Materials and methods

Animals

The C57Bl/6, apoE−/−, and LDLR−/−mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) (10th generation back-crossed from 129/B6F1 heterozygous to C57 Bl/6) and housed as previously described.9 All procedures and care of animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Usage Committee of the University of Pennsylvania. C57Bl/6 and apoE−/− mice were fed normal mouse chow (n = 14 for each group), LDLR−/− were fed a Western-type diet (normal chow supplemented with 0.15% cholesterol and 20% butter fat; n = 14). Another group of LDLR−/− mice was fed normal chow (n = 14). All of the diets were prepared by Arlan Teklad (Madison, WI), kept at 4°C, and replaced every 3 days. Urine was collected in metabolic cages (Nalgene, Rochester, NY) when the mice were 8, 16, and 26 weeks of age. Blood samples were obtained by retro-orbital bleeding at the same time points after animals were fasted overnight, as previously described.9

Two different groups of apoE−/− mice on chow and LDLR−/− mice on a high-fat diet (n = 4 for each group; 26 weeks old) were randomized to receive aspirin (60 mg/kg daily) in their drinking water for a week. This dose was selected based on preliminary experiments showing its ability to suppress platelet cyclooxygenase activity, as measured by serum TxB2 levels. By contrast, it did not influence prostaglandin E2(PGE2) levels in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated whole blood (12 ± 1.8 versus 11.5 ± 1.2 ng/mL before and after aspirin, respectively) (D.P., personal communication), an in vitro model that reflects cyclooxygenase-2 activity.10 Urine and blood samples were collected at baseline and at the end of the treatment.

Biochemical analysis

Urinary 2,3-dinor TxB2, 2,3-dinor-6-keto PGF1α, and serum TxB2 levels were measured by a stable dilution isotope gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) assay, as previously described.11 12 The intra- and interassay coefficient of variation is 5% ± 1% and 6% ± 1.5% for 2,3-dinor TxB2, 4.5% ± 1.5%, 5.8% ± 1% for 2,3-dinor-6-keto PGF1α, 4% ± 1.5% and 5% ± 1.4% for serum TxB2. Briefly, a known amount of each eicosanoid tetradeuterated internal standard was added to the samples. After solid phase extraction, samples were derived and purified by chromatography and analyzed on a Fison MD-800 GC/MS. Plasma cholesterol and triglyceride levels were determined enzymatically using Sigma reagents (Sigma, St Louis, MO).

Blood pressure and heart rate

Systolic blood pressure and heart rates in conscious mice were recorded with a computerized tail cuff system that determines systolic blood pressure using a photoelectric sensor.13 Before the study was initiated, mice were adapted to the apparatus for at least 4 days. The variability of measurements performed in the same animals in consecutive days after adaptation was less than 10%. The validity of this system has been established previously and a correlation with intra-arterial pressure measurements has been demonstrated.14

Platelet aggregation studies

Platelet aggregation was studied as previously described.12 14 Briefly, anticoagulated blood was immediately centrifuged at 100g for 10 minutes at room temperature and platelet-rich plasma collected. The remaining fraction was centrifuged at 2000g to obtain platelet-poor plasma. Platelet aggregation was determined by light absorbance using a platelet aggregometer with constant magnetic stirring. Agents used to induce an irreversible aggregation at baseline included adenosine diphosphate (ADP; 4 μmol/L) and arachidonic acid (100 μmol/L).

Preparation of mouse aortas and quantitation of atherosclerosis

After the final blood collection, mice were killed and the aortic tree was perfused for 10 minutes with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 20 mol/L butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) and 2 mmol/L EDTA, pH 7.4, by inserting a cannula into the left ventricle and allowing free efflux from an incision in the vena cava. Following the removal of surrounding adventitial tissue, the aorta was opened longitudinally from the aortic root to the iliac bifurcation, fixed in formal-sucrose (4% paraformaldehyde, 5% sucrose, 20 mol/L BHT, and 2 mmol/L EDTA, pH 7.4) then stained with Sudan IV. The extent of atherosclerosis was determined using theen face method.9 Quantitation was performed by capturing images of aortas with Dage-MTI 3CCD 3 chips color video camera connected to a Leica MZ12 dissection microscope, as previously described.9

Statistics

Results were expressed as mean ± SEM. Total cholesterol, triglyceride, serum TxB2, 2,3-dinor TxB2, and 2,3-dinor-6-keto PGF1α levels and the extent of aortic atherosclerosis were analyzed by ANOVA and subsequently by Student unpaired 2-tailed t test, as indicated. Correlations between parameters were tested by linear regression analysis.

Results

Eicosanoids biosynthesis in C57Bl/6 and apoE−/− mice

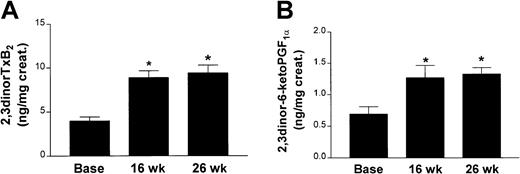

Compared with baseline, apoE−/− mice (7 males and 7 females) on chow diet showed an increase in body weight, plasma cholesterol levels, and systolic blood pressure, whereas no change was observed in triglycerides by the end of the study (Table1). Urinary 2,3-dinor TxB2and 2,3-dinor-6-keto PGF1α levels increased during the weeks of follow-up and were 3-fold and 2-fold higher than the corresponding values at the beginning of the study (Figure1A-B). No significant difference was observed between the values at 16 and 26 weeks. No correlation was observed between the increase in cholesterol and eicosanoid biosynthesis at the end of the study (data not shown).

Body weight (BW), systolic blood pressure (SBP), heart rate (HR), and total plasma cholesterol and triglyceride levels in C57Bl/6, apoE−/−, and LDLR−/− mice (n = 14 for each group)

| . | Age (wk) . | C57Bl/6 chow . | ApoE−/−chow . | LDLR−/− chow . | LDLR−/− Western diet . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BW (g) | 6 | 22 ± 2 | 21 ± 1.7 | 21 ± 2.1 | 21 ± 2.1 |

| 26 | 32 ± 2* | 36 ± 4.1* | 37.5 ± 3* | 37.5 ± 3* | |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 6 | 115 ± 12 | 121 ± 10 | 122 ± 14 | 116 ± 13 |

| 26 | 118 ± 16 | 140 ± 12* | 118 ± 12 | 148 ± 14* | |

| HR (bpm) | 6 | 558 ± 30 | 575 ± 22 | 580 ± 30 | 572 ± 24 |

| 26 | 610 ± 28 | 603 ± 25 | 620 ± 21 | 615 ± 25 | |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 6 | 130 ± 15 | 450 ± 22 | 190 ± 20 | 200 ± 16 |

| 16 | 135 ± 20 | 600 ± 25* | 210 ± 22 | 1200 ± 25† | |

| 26 | 150 ± 18 | 800 ± 35* | 240 ± 18 | 1770 ± 45† | |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 6 | 70 ± 10 | 80 ± 6 | 85 ± 12 | 95 ± 10 |

| 26 | 90 ± 10 | 95 ± 11 | 90 ± 8 | 930 ± 40† |

| . | Age (wk) . | C57Bl/6 chow . | ApoE−/−chow . | LDLR−/− chow . | LDLR−/− Western diet . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BW (g) | 6 | 22 ± 2 | 21 ± 1.7 | 21 ± 2.1 | 21 ± 2.1 |

| 26 | 32 ± 2* | 36 ± 4.1* | 37.5 ± 3* | 37.5 ± 3* | |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 6 | 115 ± 12 | 121 ± 10 | 122 ± 14 | 116 ± 13 |

| 26 | 118 ± 16 | 140 ± 12* | 118 ± 12 | 148 ± 14* | |

| HR (bpm) | 6 | 558 ± 30 | 575 ± 22 | 580 ± 30 | 572 ± 24 |

| 26 | 610 ± 28 | 603 ± 25 | 620 ± 21 | 615 ± 25 | |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 6 | 130 ± 15 | 450 ± 22 | 190 ± 20 | 200 ± 16 |

| 16 | 135 ± 20 | 600 ± 25* | 210 ± 22 | 1200 ± 25† | |

| 26 | 150 ± 18 | 800 ± 35* | 240 ± 18 | 1770 ± 45† | |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 6 | 70 ± 10 | 80 ± 6 | 85 ± 12 | 95 ± 10 |

| 26 | 90 ± 10 | 95 ± 11 | 90 ± 8 | 930 ± 40† |

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM

P < .001 versus 6 weeks;

P < .0001 versus 6 weeks.

Results in apoE−/− mice.

Urinary 2,3-dinor TxB2 (A) and 2,3 dinor-6-keto PGF1α ( B) levels in apoE−/− mice (n = 14) on chow at 8 (base), 16, and 26 weeks of age. (*P < .001 versus base.)

Results in apoE−/− mice.

Urinary 2,3-dinor TxB2 (A) and 2,3 dinor-6-keto PGF1α ( B) levels in apoE−/− mice (n = 14) on chow at 8 (base), 16, and 26 weeks of age. (*P < .001 versus base.)

No significant change in total plasma cholesterol levels or systolic blood pressure was observed in C57 Bl/6 mice at the end of the study (Table 1). Similarly, no difference was found between 6- and 26-week-old C57 Bl/6 mice for both eicosanoids levels (2,3-dinor TxB2 4 ± 1.5 versus 6 ± 1.8; 2,3-dinor-6-keto PGF1α 0.52 ± 0.1 versus 0.62 ± 0.1 ng/mg creatinine; P > .05). ApoE−/− and C57 Bl/6 mice were killed at the end of the study and their aortas analyzed for atherosclerotic lesions, which were quantitated by en facemethod. As expected for their age, apoE−/− mice had significant extension of an atherosclerotic lesion area, whereas C57 Bl/6 mice had no detectable lesions (Table2). Aortic lesion areas did not correlate with the increase in cholesterol or both eicosanoids levels (data not shown).

Aortic lesion area measured by en face method in C57Bl/6, apoE−/−, and LDLR−/− mice at 26 weeks of age (n = 14 for each group)

| . | C57Bl/6 chow . | ApoE−/−chow . | LDLR−/− chow . | LDLR−/−Western-diet . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aortic lesion area (μm2) | nd | 39 672 ± 8510 | nd | 61 581 ± 7094 |

| . | C57Bl/6 chow . | ApoE−/−chow . | LDLR−/− chow . | LDLR−/−Western-diet . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aortic lesion area (μm2) | nd | 39 672 ± 8510 | nd | 61 581 ± 7094 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

nd indicates not detectable.

Eicosanoid biosynthesis in LDLR−/− mice

Body weight, total plasma cholesterol, triglycerides, and systolic blood pressure were not different between the 2 groups of LDLR−/− mice at the beginning of the study (Table 1). Animals were randomized to receive Western-type diet or chow (7 males and 7 females for each group). LDLR−/− mice on Western-type diet showed a significant increase in plasma cholesterol and triglyceride levels, body weight, and systolic blood pressure by the end of the study (Table 1). After 8 weeks on the diet, they already had 2,3-dinor TxB2 and 2,3-dinor-6-keto PGF1α levels higher than apoE−/− mice, which further increased during the weeks of follow-up (Figure2A-B). Levels of these 2 eicosanoids were highly correlated in LDLR−/− mice (r2 = 0.75, P < .0001). At the end of the study, a direct correlation was observed between plasma cholesterol and 2,3-dinor TxB2 (r2 = 0.61) and 2,3-dinor-6-keto PGF1α (r2 = 0.55) (P < .001 for both). By contrast, at this time point no correlation was observed between triglycerides or systolic blood pressure and both eicosanoids (data not shown). Mice were killed at the end of the study and their aortas analyzed for atherosclerosis. Aortic atherosclerotic lesion area in LDLR−/− mice was more extended than in apoE−/− mice (Table 2). It also correlated with 2,3-dinor TxB2 (r2 = 0.70,P < .01), 2,3-dinor-6-keto PGF1α(r2 = 0.68, P < .01), and plasma cholesterol levels (r2 = 0.72,P < .01).

Results in LDLR−/− mice.

Urinary 2,3-dinor TxB2 (A) and 2,3-dinor-6-keto PGF1α (B) levels in LDLR−/− mice (n = 14) on a Western-type diet at 8 (base), 16, and 26 weeks of age. (*P < .001 versus base, **P < .001 versus 16 weeks.)

Results in LDLR−/− mice.

Urinary 2,3-dinor TxB2 (A) and 2,3-dinor-6-keto PGF1α (B) levels in LDLR−/− mice (n = 14) on a Western-type diet at 8 (base), 16, and 26 weeks of age. (*P < .001 versus base, **P < .001 versus 16 weeks.)

The LDLR−/− mice on chow showed an increase in their body weight but no significant change in their plasma lipid levels or systolic blood pressure was observed (Table 1). Similarly, no significant change was observed between 6- and 26-week-old animals for both eicosanoid levels (2,3-dinor TxB2 5 ± 0.9 versus 6.1 ± 1; 2,3-dinor-6-keto PGF1α 0.54 ± 0.1 versus 0.62 ± 0.09 pg/mg creatinine; P > .05 for both), nor were detectable atherosclerotic lesions found in their aortas (Table2).

Aspirin study

Next we investigated whether the increased eicosanoid biosynthesis was secondary to in vivo platelet activation. Twenty-six-week-old apoE−/− mice on chow and LDLR−/− mice on a high-fat diet (n = 4 for each group) were randomized to receive aspirin (60 mg/kg daily) for a week. In both animals, compared with baseline, aspirin suppressed serum TxB2 and 2,3-dinor TxB2 by roughly 90%, whereas a 60% reduction in 2,3-dinor-6- ketoPGF1α was observed (Table3). Similarly, aspirin completely prevented ADP- and arachidonic acid–induced platelet aggregation (data not shown).

Aspirin's effect on serum TxB2, 2,3-dinor TxB2 and 2,3-dinor-6-keto PGF1α levels in apoE−/− and LDLR−/− mice (n = 4 for each group) at baseline (B) and after 1 week on aspirin (A)

| . | . | Serum TxB2(ng/mL) . | 2,3-dinor TxB2 (ng/mg creatinine) . | 2,3-dinor-6-keto PGF1α (ng/mg creatinine) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ApoE−/− | B | 175 ± 20 | 13 ± 2 | 1.5 ± 0.20 |

| A | 10 ± 1.53-150 | 1.5 ± 0.53-150 | 0.74 ± 0.183-150 | |

| LDLR−/− | B | 180 ± 18 | 110 ± 10 | 3.8 ± 0.25 |

| A | 9 ± 1.63-150 | 10 ± 2.53-150 | 1.68 ± 0.203-150 |

| . | . | Serum TxB2(ng/mL) . | 2,3-dinor TxB2 (ng/mg creatinine) . | 2,3-dinor-6-keto PGF1α (ng/mg creatinine) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ApoE−/− | B | 175 ± 20 | 13 ± 2 | 1.5 ± 0.20 |

| A | 10 ± 1.53-150 | 1.5 ± 0.53-150 | 0.74 ± 0.183-150 | |

| LDLR−/− | B | 180 ± 18 | 110 ± 10 | 3.8 ± 0.25 |

| A | 9 ± 1.63-150 | 10 ± 2.53-150 | 1.68 ± 0.203-150 |

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (

P< 0.001).

Discussion

In this study we show that 2 different murine models of atherosclerosis, the apoE−/− and LDLR−/−mice on a Western-type diet, have increased endogenous TxA2biosynthesis. In contrast, C57 Bl/6 mice as well as LDLR−/− mice on a chow diet, which do not develop high cholesterol levels or atherosclerotic aortic lesions, do not show an increase in TxA2 biosynthesis. Although this eicosanoid shows a similar pattern in the first 2 models, some differences are evident. In apoE−/− mice, 2,3-dinor TxB2levels increased by 16 weeks of age compared with baseline, but no further significant increase was observed at 26 weeks of age. Furthermore, this increase did not correlate with cholesterol levels as well as with the extension of the aortic lesion area. By contrast, LDLR−/− mice on a Western-type diet had higher levels of cholesterol, triglycerides, and 2,3-dinor TxB2 than apoE−/− mice. Furthermore, levels of this eicosanoid correlated with the increase in plasma cholesterol levels and the extension of the atherosclerotic aortic lesion area. However, in both animals the increase in TxA2 biosynthesis was secondary to an increased in vivo platelet activation. This was demonstrated by the aspirin study. We are aware that aspirin is not a specific cyclooxygenase-1 inhibitor and that at high doses can also inhibit cyclooxygenase-2 activity.15 However, at the dosage used in our study it completely suppressed serum TxB2, ex vivo platelet aggregation, and 2,3-dinor TxB2. This would suggest that TxA2 generated in vivo is largely derived from cyclooxygenase-1, presumably from platelets. The increased 2,3-dinor TxB2 levels observed could also be secondary to the high circulating cholesterol levels. Thus, LDLR−/− mice on chow diet, which did not develop hypercholesterolemia, showed no increase in 2,3-dinor TxB2 levels. By contrast, we found higher 2,3-dinor TxB2 levels in animals with higher cholesterol levels. However, it is intriguing that the increase in 2,3-dinor TxB2 level correlated with cholesterol levels and atherosclerotic lesion areas only in LDLR−/− mice. We speculate that in vivo platelet activation could derive from different mechanism(s) and probably play a different role in these 2 murine models. Both animal models have been reported as having in vivo increased lipid peroxidation levels.9,16 17 It is possible that different levels of cholesterol can influence different levels of in vivo lipid peroxidation, which in turn could differently influence platelet metabolic activities. Future interventional studies in these animal models are necessary to address these hypotheses.

In addition to an increase in TxA2 formation, this study demonstrates enhanced PGI2 biosynthesis in both animals. LDLR−/− mice had higher levels of 2,3-dinor-6-keto PGF1α than apoE−/− mice. However, the different levels of increased PGI2 production could be secondary to the different increase in cholesterol or systolic blood pressure and subsequent platelet activation in these animals. This is consistent with other previous observations of increased PGI2 generation in a number of conditions associated with accelerated platelet turnover,5,6,11,13 and it suggests that enhanced PGI2 production in these mice could reflect a local compensatory response by stimulated vascular endothelium. This is supported by the fact that aspirin, by suppressing TxA2biosynthesis, significantly reduced prostacyclin levels in both animal models also, which is consistent with previous observations in humans.18 However, this effect could be due not only to inhibition of cyclooxygenase-1 but also cyclooxygenase-2 or both because of the nonselective action of aspirin.15

Previous studies have examined the biosynthesis of these eicosanoids in other animals and human atherosclerosis,19-23 but to the best of our knowledge, no data are available for transgenic mouse models of atherosclerosis. The results of the present investigation show that the biosynthesis of both eicosanoids is altered at an early stage of the disease process and is secondary to an increased in vivo platelet activation. We conclude that assessment of these urinary metabolites in murine models of atherosclerosis may afford the basis for future investigations on the functional role of these eicosanoids in the evolution and progression of such a disease.

Supported in part by a grant-in-aid from the American Heart Association (Pennsylvania and Delaware affiliate) and the National Institutes of Health (HL 61364 and M01RR00040).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Domenico Praticò, Center for Experimental Therapeutics, 812 BRB II/III, 421 Curie Blvd, Philadelphia, PA 19104; e-mail: domenico@spirit.gcrc.upenn.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal