Abstract

Tie-2 receptor tyrosine kinase expressed in endothelial and hematopoietic cells is believed to play a role in both angiogenesis and hematopoiesis during development of the mouse embryo. This article addressed whether Tie-2 is expressed on fetal liver hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) at day 14 of gestation. With the use of anti–Tie-2 monoclonal antibody, its expression was detected in approximately 7% of an HSC population of Kit-positive, Sca-1–positive, lineage-negative or -low, and AA4.1-positive (KSLA) cells. These Tie-2–positive KSLA (T+ KSLA) cells represent 0.01% to 0.02% of fetal liver cells. In vitro colony and in vivo competitive repopulation assays were performed for T+ KSLA cells and Tie-2–negative KSLA (T− KSLA) cells. In the presence of stem cell factor, interleukin-3, and erythropoietin, 80% of T+ KSLA cells formed colonies in vitro, compared with 40% of T− KSLA cells. Long-term multilineage repopulating cells were detected in T+ KSLA cells, but not in T− KSLA cells. An in vivo limiting dilution analysis revealed that at least 1 of 8 T+ KSLA cells were such repopulating cells. The successful secondary transplantation initiated with a limited number of T+ KSLA cells suggests that these cells have self-renewal potential. In addition, engraftment of T+ KSLA cells in conditioned newborn mice indicates that these HSCs can be adapted equally by the adult and newborn hematopoietic environments. The data suggest that T+ KSLA cells represent HSCs in the murine fetal liver.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) develop in the murine fetal liver accompanied by the generation of myeloid and lymphoid precursor cells.1-6 It has been suggested that fetal liver HSCs have a greater self-renewal capacity than do adult bone marrow HSCs.7-10 Understanding of the properties of fetal liver HSCs may help reveal the mechanism of HSC self-renewal. A high degree of purification is necessary before characterization of HSCs.

By using a monoclonal antibody, AA4.1, a first attempt was made to enrich HSCs from the murine fetal liver.11 Subsequently, it has been shown that the application of a bone marrow HSC phenotype—Kit-positive, Sca-1–positive, and lineage-negative or -low (KSL)12—improves the purification of fetal liver HSCs.13-15 On the other hand, it has also been noticed that the expression of some cell-surface molecules differs between fetal liver and adult bone marrow HSCs.16,17 In the case of bone marrow cells, we have obtained a nearly homogeneous stem cell population by excluding CD34+ cells from KSL cells.18 In the fetal liver, however, most KSL cells are present in the CD34+ fraction where HSCs reside19 (H.N. et al, unpublished data, December 1999). Thus, anti-CD34 antibody seems not to be useful for the further purification of fetal liver HSCs.

Tie-2, also termed Tek, is a receptor tyrosine kinase cloned from endothelial cells20 and bone marrow HSCs.21Studies of mutant mice with a loss of function have implied that the interaction of Tie-2 and its ligand, angiopoietin-1, plays an important role in remodeling and stabilization of the primitive vasculature.22,23 It has been demonstrated that Tie-2–positive cells in the aorta-gonad-mesonephros (AGM) region contain hemangioblasts capable of differentiating into both hematopoietic and endothelial lineages.24 Tie-2–positive cells detected in KSL bone marrow cells have been shown to have stem cell activity.25 To extend these observations, we examined the Tie-2 expression on KSL cells in the fetal liver and performed in vitro colony formation and in vivo long-term repopulation assays for Tie-2–positive and Tie-2–negative KSL fetal liver cells. We present data indicating that fetal liver HSCs express the Tie-2 molecule and that anti–Tie-2 antibody is useful for the further purification of HSCs in the fetal liver.

Materials and methods

Mice

C57BL/6N (B6-Ly5.2) mice were obtained from Clea Japan Inc. (Shizuoka, Japan). C57BL/6 mice congenic for the Ly5 locus (B6-Ly5.1) were bred and maintained in the University of Tsukuba Laboratory Animal Research Center. To obtain F1-hybrid embryos, B6-Ly5.1 male and B6-Ly5.2 female mice were mated. The day of appearance of a vaginal plug was designated as day 0 of gestation.

B6-Ly5.2 females at 8 to 10 weeks of age and B6-Ly5.2 newborn mice were used as recipients in transplantation experiments.

Purification of HSCs

At day 14 of gestation, the liver was removed from an embryo under a dissecting microscope. Fetal liver cells were dispersed in Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS; Life Technologies, Rockville, MD) containing 5% fetal calf serum (HBSS/FCS) by flushing through graded sizes of needles. Cells were counted on a hemocytometer and subjected to immuno-panning with AA4.1 antibody, as described.26Briefly, the supernatant of AA4.1 hybridoma was incubated in 10-cm petri dishes (Falcon 1001; Becton Dickinson Labware, Lincoln, NJ) that had been coated with mouse antirat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Cells were plated at 2 × 107 cells per dish and incubated at 4°C for 1 hour. After extensive washing of the dishes with HBSS/FCS, adherent cells were collected. The cells were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline containing 2% FCS and 0.05% sodium azide (staining medium), counted, and subjected to the staining process with monoclonal antibodies at pretitrated optimal concentrations. The cells were incubated with a lineage antibody cocktail consisting of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti–Gr-1 (RB6-8C5), Mac-1 (M1/70), B220 (RA3-6B2), NK1.1 (PK136), and Ter-119 (a gift from Dr T. Kina, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan); phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti–Sca-1 (E13-161.7), allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti–c-Kit antibody (ACK-2; a gift from S.-I. Nishikawa, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan), and biotinylated anti–Tie-2 antibody (TEK4). After washing the cells with staining medium, we used streptavidin-Texas Red (Molecular Probes Inc, Eugene, OR) to develop biotinylated antibody. The cells were finally suspended in staining medium containing propidium iodide at 1 μg/mL. Anti–Tie-2 monoclonal antibody was prepared as described previously.25 All other monoclonal antibodies were purchased from PharMingen (San Diego, CA) except as specified. Four-color flow cytometric analysis and sorting were performed on a FACS Vantage (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

Single-cell culture.

A round-bottom 96-well plate (Corning Inc, Corning, NY) containing 200 μL of 10% FCS, 5 × 10−5 mol/L 2-β-mercaptoethanol, 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, 10 ng/mL mouse interleukin (IL)-3, 2 U/mL human erythropoietin, and 10 ng/mL mouse stem cell factor (SCF) in α medium per well was prepared. All cytokines were kindly provided by Kirin Brewery (Maebashi, Japan). Automated deposition of single cells was carried out by the Clonecyt (Becton Dickinson). Sorted cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2in air. Observations of colony formation were made at 1, 2, and 3 weeks of culture. Colonies were classified according to their sizes. C-level cells were defined as the cells that formed clusters consisting of fewer than 50 cells. L-level cells formed colonies consisting of 50 to 100 cells. M-level cells formed colonies consisting of 100 to 104 cells. H-level cells formed colonies of more than 104 cells. Representative colonies between 2 and 3 weeks of culture were transferred onto glass slides by using a Cytospin (Shandon Inc, Pittsburgh, PA) and stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa solution for morphologic examination.

Conditioning of recipients and competitive repopulation.

Adult mice (8 to 10 weeks old) were irradiated at a dose of 9.5 Gy with an x-ray machine. Newborn mice were conditioned as described,27 with a slight modification. In brief, busulfan (1,4-butanediol dimethanesulfonate; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was injected subcutaneously into the dams at days 17 and 18 of gestation at a dosage of 15 mg/kg of body weight. Before injection, busulfan was resolved in dimethylsulfoxide at 15 mg/mL, and then the solution was diluted with HBSS to 1.5 mg/mL for use. Purified fetal liver cells (B6-F1) were mixed with 2 × 105 adult bone marrow cells (B6-Ly5.1) and injected either into irradiated adult recipients (B6-Ly5.2) through the tail vein or directly into the liver of conditioned newborn recipients (B6-Ly5.2).

Analysis of hematopoietic chimerism.

Blood samples were obtained from the recipients after transplantation. After red blood cell lysis, blood cells were stained with biotinylated anti-Ly5.1, FITC–anti-Ly5.2, APC–anti-B220, and a mixture of PE–anti-Mac-1 and PE–anti-Gr-1 or PE–anti-CD4 and PE–anti-CD8 antibodies. Multicolor analysis was performed on a FACS Vantage. A total of 104 events were collected and analyzed with CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson). Chimerism (as a percentage) of fetal liver–derived cells was obtained as follows: (% F1-type cells)/(% F1-type cells + % Ly5.1-type cells) × 100. When percentage chimerism was more than 1.0, recipients were considered to be successfully engrafted and presented as positive mice. Exclusion of the residual host cells (Ly5.2 cells) and contaminated red blood cells upon analysis allowed precise evaluation of the contribution of fetal liver–derived cells versus competitor-derived cells.28This was particularly useful in analysis of newborn recipients because the sublethal conditioning resulted in varying degrees of recovery of endogenous hematopoiesis. Reconstitution in myeloid and B- and T-lymphoid lineages was verified by the presence of Mac-1– or Gr-1–positive cells, B220-positive cells, and CD4- or CD8-positive cells in fetal liver–derived peripheral blood cells. The number of repopulating units (RUs) was calculated by applying the percentage of chimerism for total leukocytes to the formula previously described.10 28 The number of RUs per 100 test donor cells (RU/100) was calculated for comparison among different cells.

Semiquantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction.

Total RNA was extracted from purified cells. Synthesis and normalization of cDNA were performed as described previously.29 Before amplification, samples were denatured at 94°C for 1 minute. A 40-cycle polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed with the GeneAmp PCR system 9600 (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, CA). Each cycle consisted of 20 seconds at 94°C, 20 seconds at 55°C, and 30 seconds at 72°C. Extension was done at 72°C for 3 minutes. PCR products were analyzed on a 2% agarose gel.

The primers used were as follows: 5′-ACAGGATTCAGGTATGTTGC-3′ and 5′-CTCATGGGCTCAGGAATATTC-3′ for c-kit gene, 5′-GGATGGCAATCGAATCACTG-3′ and 5′-TCTGCTCTAGGCTGCTTCTT-3′ fortie-2 gene, 5′-TGAGCCAAGTGTTAAGTGTGG-3′ and 5′-GAGCAAGCTGCATCATTTCC-3′ for flk-1 gene, and 5′-AGTACATGCTGAGGATTGAGC-3′ and 5′-GTTATCAGCATCCTTCGTGC-3′ for angiopoietin-1 gene.

Results

Expression of Tie-2 on KSLA cells

A number of studies have shown that hematopoietic stem and precursor cells in the fetal liver express the AA4.1 molecule.4,11,13,17,30 31 Immuno-panning with AA4.1 monoclonal antibody was first performed on total fetal liver cells at day 14 of gestation. By this method, Kit+, Sca-1+, lineage−/low (KSL) cells were significantly enriched (more than 10-fold). The recovery rate of the cells after panning was 2.0% ± 0.4% (mean ± SE, n = 8), as expected. KSL cells accounted for 11.4% ± 0.8% (mean ± SE, n = 8) of AA4.1-positive cells.

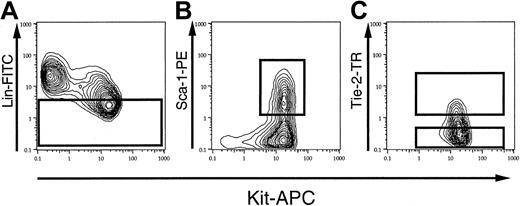

Figure 1 demonstrates the sorting gates for Kit+, Sca-1+, lin−/low, AA4.1+ (KSLA) cells on FACS profiles. Lineage marker–negative or –low (lin−/low) cells were selected first (Figure 1A), and subsequently Kit+, Sca-1+ cells were gated on these lin−/low cells (Figure 1B). A low level of Tie-2 expression was observed in KSLA cells, as shown in Figure 1C. Tie-2–positive KSLA (T+ KSLA) cells represented 7.4% ± 1.4% (mean ± SE, n = 8) of the KSLA cells when unstained AA4.1+ cells were used as negative controls. Thus, T+ KSLA cells were considered to represent between 0.01% and 0.02% of the total fetal liver cells. To compare the developmental potential of Tie-2–positive and –negative KSLA cells, we tentatively set a sorting gate for Tie-2–negative cells in KSLA cells, as shown in Figure 1C. As a result, the cells in the Tie-2–negative gate accounted for 64.5% ± 4.3% (mean ± SE, n = 8) of the KSLA cells.

Tie-2 expression on KSLA fetal liver cells.

After panning with AA4.1 antibody, the cells were stained with FITC–anti-lineage markers, PE–anti-Sca-1, APC–anti-Kit, and biotinylated anti–Tie-2, followed by streptavidin-Texas Red. (A) The gate for lineage-negative or -low (lin−/low) cells upon FACS analysis. Lin−/low cells consisted of 37.4% ± 2.1% (mean ± SE, n = 8) of AA4.1-enriched cells. (B) Kit-positive, Sca-1–positive cells among lin−/lowAA4.1+ cells. (C) The sorting gates for Tie-2–positive (T+ KSLA) and Tie-2–negative (T− KSLA) cells.

Tie-2 expression on KSLA fetal liver cells.

After panning with AA4.1 antibody, the cells were stained with FITC–anti-lineage markers, PE–anti-Sca-1, APC–anti-Kit, and biotinylated anti–Tie-2, followed by streptavidin-Texas Red. (A) The gate for lineage-negative or -low (lin−/low) cells upon FACS analysis. Lin−/low cells consisted of 37.4% ± 2.1% (mean ± SE, n = 8) of AA4.1-enriched cells. (B) Kit-positive, Sca-1–positive cells among lin−/lowAA4.1+ cells. (C) The sorting gates for Tie-2–positive (T+ KSLA) and Tie-2–negative (T− KSLA) cells.

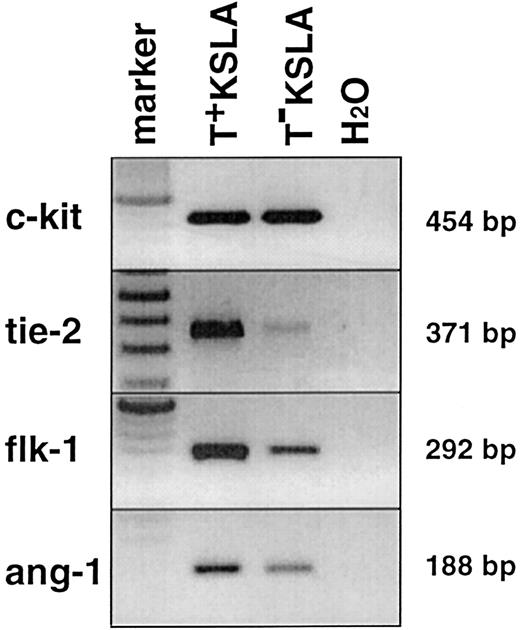

To verify the segregation based on Tie-2 expression, we performed semiquantitative reverse transcriptase (RT)–PCR on normalized cDNA from sorted T+ KSLA cells and T− KSLA cells. As shown in Figure 2, the amounts ofc-kit transcript detected in T+ KSLA and T− KSLA cells were similar. In contrast, tie-2transcript was predominantly detected in T+ KSLA cells, confirming a good separation of Tie-2–positive cells from a KSLA population. In addition, the flk-1 transcript was detected in both cells,32 but its expression level seemed higher in T+ KSLA cells than in T− KSLA cells. Interestingly, the expression of a ligand for the tie-2receptor, angiopoietin-1,33 was detected in T+KSLA cells, consistent with a recent report.34

RT-PCR on Tie-2–positive and –negative KSLA cells.

PCRs for c-kit, tie-2, flk-1, andang-1 genes were performed on normalized cDNA from these cells. One PCR contained cDNA equivalent to 500 to 1000 cells by calculation.

RT-PCR on Tie-2–positive and –negative KSLA cells.

PCRs for c-kit, tie-2, flk-1, andang-1 genes were performed on normalized cDNA from these cells. One PCR contained cDNA equivalent to 500 to 1000 cells by calculation.

In vitro colony formation of Tie-2–positive KSLA cells

We conducted a single-cell culture of KSLA, T+ KSLA, and T− KSLA cells in the presence of SCF, IL-3, and erythropoietin because this assay gives reproducible and precise frequencies of colony-forming cells in a limited number of purified cells when compared with a conventional methylcellulose colony assay (H.N. et al, unpublished data, December 1999).

We classified the colony-forming ability of individual cells into C-, L-, M-, and H-levels according to the size of colonies formed. In the case of KSLA cells, 49.7% ± 10.4% (mean ± SD, n = 3) of the cells formed colonies during 3 weeks. T+ KSLA cells formed colonies at a frequency of 79.2% ± 12.9% (n = 3), whereas T− KSLA cells did so at 39.2% ± 7.5% (n = 3) (Figure 3). The frequencies of C-level cells were similar among KSLA, T+ KSLA, and T−KSLA cells. However, the frequency of the total of M- and H-level cells in T+ KSLA cells was significantly higher than that in KSLA cells as well as that in T− KSLA cells (P < .001). Morphologic examination of colony cells showed that H-level colonies contained all granulocytes, macrophages, erythroblasts, and megakaryocytes in most of the cases examined (data not shown).

Colony formation of KSLA, T+ KSLA, and T− KSLA cells.

A single-cell culture of a total of 240 cells was performed for each KSLA, T+ KSLA, and T− KSLA cell population. C-, L-, M-, and H-level cells formed colonies consisting of fewer than 50, 50 to 100, 100 to 104, and more than 104cells, respectively. C-level cells represented 25.8% ± 12.1%, 26.7% ± 11.6%, and 25.8% ± 3.6% (mean ± SD, n = 3) of KSLA, T+ KSLA, and T− KSLA cells, respectively. L-level cells represented 3.6% ± 0.5%, 1.7% ± 1.7%, and 1.7% ± 1.7% of KSLA, T+ KSLA, and T− KSLA cells. M-level cells represented 15.8% ± 2.2%, 35.6% ± 5.9%, and 9.7% ± 2.7% of KSLA, T+ KSLA, and T− KSLA cells. H-level cells represented 4.4% ± 1.9%, 15.3% ± 4.9%, and 1.9% ± 2.1% of KSLA, T+ KSLA, and T− KSLA cells.

Colony formation of KSLA, T+ KSLA, and T− KSLA cells.

A single-cell culture of a total of 240 cells was performed for each KSLA, T+ KSLA, and T− KSLA cell population. C-, L-, M-, and H-level cells formed colonies consisting of fewer than 50, 50 to 100, 100 to 104, and more than 104cells, respectively. C-level cells represented 25.8% ± 12.1%, 26.7% ± 11.6%, and 25.8% ± 3.6% (mean ± SD, n = 3) of KSLA, T+ KSLA, and T− KSLA cells, respectively. L-level cells represented 3.6% ± 0.5%, 1.7% ± 1.7%, and 1.7% ± 1.7% of KSLA, T+ KSLA, and T− KSLA cells. M-level cells represented 15.8% ± 2.2%, 35.6% ± 5.9%, and 9.7% ± 2.7% of KSLA, T+ KSLA, and T− KSLA cells. H-level cells represented 4.4% ± 1.9%, 15.3% ± 4.9%, and 1.9% ± 2.1% of KSLA, T+ KSLA, and T− KSLA cells.

Existence of long-term repopulating stem cells in T+KSLA cells

KSLA, T+ KSLA, or T− KSLA cells were mixed with 2 × 105 adult bone marrow cells and transplanted into irradiated adult mice. After transplantation, peripheral blood cells of the recipients were analyzed for multilineage reconstitution by purified fetal liver cells versus bone marrow cell competitors. Figure 4A represents the FACS analysis of blood cells in the recipients after transplantation. Fetal liver–derived cells were detected as F1-type cells expressing both Ly5.1 and Ly5.2 antigens. Bone marrow competitor-derived cells were of Ly5.1 origin. We calculated the percentage of fetal liver–derived cells in the total donor-derived cells, excluding residual host cells upon analysis.

Reconstitution analysis of the adult and newborn recipients.

Ten T+ KSLA cells (B6-F1) and 2 × 105 bone marrow cells (B6-Ly5.1) were mixed and transplanted into either irradiated adult or conditioned newborn mice. Twelve weeks after transplantation, peripheral blood cells of the recipients were analyzed on a FACS. The representative results for adult (A) and newborn (B) recipients are shown. F1-type cells, presenting both Ly5.1 and Ly5.2 antigens, were derived from T+ KSLA cells. Ly5.1-type cells were derived from bone marrow competitor cells. Note the large number of host-derived cells (Ly5.2 type) in the case of a newborn recipient (Bi). Myeloid (Aii and Bii), B-lymphoid (Aiii and Biii), and T-lymphoid (Aiv and Biv) cells are present within the gate of fetal liver–derived cells (F1 type).

Reconstitution analysis of the adult and newborn recipients.

Ten T+ KSLA cells (B6-F1) and 2 × 105 bone marrow cells (B6-Ly5.1) were mixed and transplanted into either irradiated adult or conditioned newborn mice. Twelve weeks after transplantation, peripheral blood cells of the recipients were analyzed on a FACS. The representative results for adult (A) and newborn (B) recipients are shown. F1-type cells, presenting both Ly5.1 and Ly5.2 antigens, were derived from T+ KSLA cells. Ly5.1-type cells were derived from bone marrow competitor cells. Note the large number of host-derived cells (Ly5.2 type) in the case of a newborn recipient (Bi). Myeloid (Aii and Bii), B-lymphoid (Aiii and Biii), and T-lymphoid (Aiv and Biv) cells are present within the gate of fetal liver–derived cells (F1 type).

Table 1 shows the data for long-term reconstitution by purified fetal liver cells. In 7 of 9 mice having transplantation with 10 T+ KSLA cells, long-term reconstitution was observed after transplantation. The contribution of T+ KSLA–derived cells in blood of the recipients increased with time versus that of bone marrow competitor-derived cells. At 24 weeks after transplantation, all myeloid and B- and T-lymphoid lineages were reconstituted (Table 2). The mean of RUs per 100 T+ KSLA cells at 24 weeks was 4.24. Because T+ KSLA cells accounted for 7.4% of KSLA cells on average, the number of RUs given by T+ KSLA cells among 100 KSLA cells should be 0.31 RUs (4.24 × 0.074). This was identical to the number of RUs in 100 KSLA cells actually measured. Thus, all repopulating activity of 100 KSLA cells turned out to belong to T+ KSLA cells. In contrast, none of 7 mice having transplantation with 100 T− KSLA cells showed a significant level of reconstitution. From these data, we conclude that T+ KSLA represented the repopulating activity among KSLA cells.

Transplantation of purified fetal liver cells at day 14 of gestation

| Cells . | Time after transplantation, wk . | Positive mice . | % Chimerism . | RU/100 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 KSLA cells | 4 | 6/7 | 5.3 ± 6.8 (n = 6) | 0.10 |

| 12 | 7/7 | 11.4 ± 11.5 (n = 7) | 0.28 | |

| 24 | 7/7 | 13.4 ± 8.8 (n = 7) | 0.31 | |

| 10 T+ KSLA cells | 4 | 7/9 | 6.2 ± 5.5 (n = 7) | 1.08 |

| 12 | 7/9 | 15.6 ± 11.7 (n = 7) | 2.88 | |

| 24 | 7/9 | 21.4 ± 25.8 (n = 7) | 4.24 | |

| 100 T− KSLA cells | 4 | 2/7 | 1.5 (n = 2) | 0.009 |

| 12 | 1/7 | 1.1 (n = 1) | 0.003 | |

| 24 | 0/7 |

| Cells . | Time after transplantation, wk . | Positive mice . | % Chimerism . | RU/100 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 KSLA cells | 4 | 6/7 | 5.3 ± 6.8 (n = 6) | 0.10 |

| 12 | 7/7 | 11.4 ± 11.5 (n = 7) | 0.28 | |

| 24 | 7/7 | 13.4 ± 8.8 (n = 7) | 0.31 | |

| 10 T+ KSLA cells | 4 | 7/9 | 6.2 ± 5.5 (n = 7) | 1.08 |

| 12 | 7/9 | 15.6 ± 11.7 (n = 7) | 2.88 | |

| 24 | 7/9 | 21.4 ± 25.8 (n = 7) | 4.24 | |

| 100 T− KSLA cells | 4 | 2/7 | 1.5 (n = 2) | 0.009 |

| 12 | 1/7 | 1.1 (n = 1) | 0.003 | |

| 24 | 0/7 |

Kit+, Sca+, Lin−/low, AA4.1+ (KSLA) cells were sorted on a FACS and transplanted to lethally irradiated adult mice together with 2 × 105 adult bone marrow cells. KSLA cells were fractionated based on Tie-2 expression. Tie-2–positive (T+) and –negative (T−) KSLA cells were also transplanted. After transplantation, peripheral blood cells of the recipients were analyzed to evaluate engraftment. The number of positive mice per number of mice having transplantation is shown. The mean of repopulating units (RU) per 100 cells (RU/100) was obtained with the formula of Harrison et al.10

Lineage reconstitution

| Result no. . | Cells . | Time after transplantation, wk . | % Chimerism . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myeloid . | B-lymphoid . | T-lymphoid . | |||

| 1 | KSLA | 24 | 12.0 ± 7.7 (n = 7) | 12.3 ± 8.1 (n = 7) | 10.9 ± 8.6 (n = 7) |

| T+KSLA | 24 | 24.2 ± 31.1 (n = 7) | 19.7 ± 25.5 (n = 7) | 18.5 ± 21.9 (n = 7) | |

| 2 | T+KSLA | 12 | 23.2 ± 21.6 (n = 7) | 40.3 ± 18.9 (n = 7) | 58.8 ± 20.6 (n = 7) |

| 3 | T+KSLA | 12 | 49.7 ± 28.6 (n = 9) | 69.7 ± 19.6 (n = 9) | 76.6 ± 29.4 (n = 9) |

| 4 | T+KSLA | 12 | 5.4 ± 3.6 (n = 3) | 3.2 ± 1.8 (n = 3) | 7.2 ± 3.3 (n = 3) |

| Result no. . | Cells . | Time after transplantation, wk . | % Chimerism . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myeloid . | B-lymphoid . | T-lymphoid . | |||

| 1 | KSLA | 24 | 12.0 ± 7.7 (n = 7) | 12.3 ± 8.1 (n = 7) | 10.9 ± 8.6 (n = 7) |

| T+KSLA | 24 | 24.2 ± 31.1 (n = 7) | 19.7 ± 25.5 (n = 7) | 18.5 ± 21.9 (n = 7) | |

| 2 | T+KSLA | 12 | 23.2 ± 21.6 (n = 7) | 40.3 ± 18.9 (n = 7) | 58.8 ± 20.6 (n = 7) |

| 3 | T+KSLA | 12 | 49.7 ± 28.6 (n = 9) | 69.7 ± 19.6 (n = 9) | 76.6 ± 29.4 (n = 9) |

| 4 | T+KSLA | 12 | 5.4 ± 3.6 (n = 3) | 3.2 ± 1.8 (n = 3) | 7.2 ± 3.3 (n = 3) |

Result no. 1 shows the percentages of chimerism as mean ± SD for myeloid and B- and T-lymphoid lineages for the experiment presented in Table 1. Result nos. 2 and 3 are from experiments 1 and 3 shown in Table 3. Result no. 4 is from the experiment in Table 4. In all cases, multilineage reconstitution was observed.

Hematopoietic reconstitution in conditioned adult and newborn mice with T+ KSLA cells

To confirm the repopulating activity in a limited number of T+ KSLA cells and to clarify whether the same cells are able to reconstitute hematopoiesis in conditioned newborns, we transplanted 10 T+ KSLA cells into either irradiated adult mice or conditioned newborn mice, together with 2 × 105bone marrow cells. Because a given dose of busulfan was sublethal to newborn mice,27 host cells remarkably contributed to chimerism at varying degrees, as demonstrated in Figure 4B. Thus, it was important to exclude the percentage of host-derived cells upon calculation of the percentage of chimerism of fetal liver–derived cells.

The data in Table 3 show that 10 T+ KSLA cells were sufficient to reconstitute the hematopoietic system of myeloablated adults in repeated experiments. It is also shown that these 10 cells were able to repopulate newborn mice in most cases for an observation period of 12 weeks. Reconstitution occurred in myeloid and B- and T-lymphoid lineages, as shown in Table2.

Irradiated adult and conditioned newborn mice having transplantation with 10 T+ KSLA cells

| Experiment . | Recipients . | Positive mice . | % Chimerism . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adult | 7/7 | 25.1 ± 19.5 (n = 7) |

| 2 | Adult | 6/6 | 41.9 ± 25.5 (n = 6) |

| Newborn | 8/8 | 17.2 ± 20.0 (n = 8) | |

| 3 | Newborn | 9/10 | 55.1 ± 22.2 (n = 9) |

| Experiment . | Recipients . | Positive mice . | % Chimerism . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adult | 7/7 | 25.1 ± 19.5 (n = 7) |

| 2 | Adult | 6/6 | 41.9 ± 25.5 (n = 6) |

| Newborn | 8/8 | 17.2 ± 20.0 (n = 8) | |

| 3 | Newborn | 9/10 | 55.1 ± 22.2 (n = 9) |

Tie-2+, Kit+, Sca+, Lin−/low, AA4.1+ (T+ KSLA) cells were purified from fetal liver cells at day 14 of gestation. Ten purified cells were mixed with 2 × 105 adult bone marrow cells and transplanted to either irradiated adult or conditioned newborn mice. Peripheral blood cells of the recipient mice were analyzed for the presence of fetal liver–derived cells at 12 weeks after transplantation. Positive mice showed more than 1% chimerism. Chimerism (%) is presented as mean ± SD.

Limiting dilution assay of T+KSLA cells

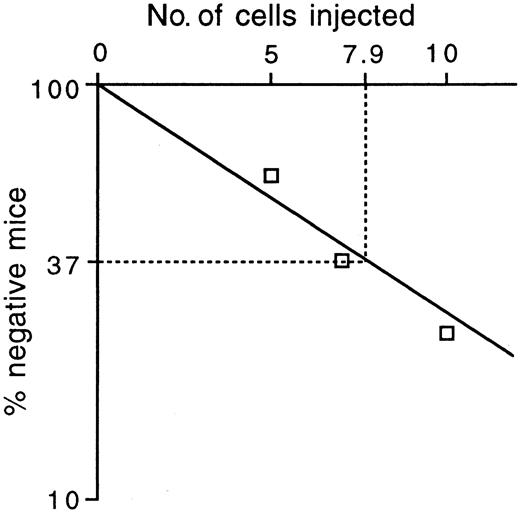

To estimate the frequency of long-term repopulating stem cells among T+ KSLA cells, we mixed 5 cells, 7 cells, and 10 cells, respectively, with 2 × 105 competitor cells and transplanted them into a group of irradiated mice. According to the Poisson probability distribution, the frequency of repopulating cells at 12 weeks after transplantation was estimated as 1 in 7.9 T+ KSLA cells (Figure5). Reconstitution levels varied among the mice engrafted with T+ KSLA cells, but all myeloid and B- and T-lymphoid lineages were reconstituted in positive recipients (data not shown). Given the frequency of repopulating cells, T+ KSLA cells with repopulating capacity are considered to be present at 1.3 to 2.5 cells per 105 fetal liver cells.

In vivo limiting dilution analysis of T+KSLA cells.

Five, 7, and 10 T+ KSLA cells were transplanted into irradiated mice together with 2 × 105 bone marrow cells. Peripheral blood cells of the recipient mice were analyzed for engraftment of transplanted cells 12 weeks after transplantation. Reconstitution was observed in 4 of 10 mice with transplants of 5 cells, 5 of 8 mice with transplants of 7 cells, and 6 of 8 mice with transplants of 10 cells. The percentages of negative mice were plotted against the number of injected T+ KSLA cells.

In vivo limiting dilution analysis of T+KSLA cells.

Five, 7, and 10 T+ KSLA cells were transplanted into irradiated mice together with 2 × 105 bone marrow cells. Peripheral blood cells of the recipient mice were analyzed for engraftment of transplanted cells 12 weeks after transplantation. Reconstitution was observed in 4 of 10 mice with transplants of 5 cells, 5 of 8 mice with transplants of 7 cells, and 6 of 8 mice with transplants of 10 cells. The percentages of negative mice were plotted against the number of injected T+ KSLA cells.

Secondary transplantation with T+KSLA–derived bone marrow cells

To find out whether T+ KSLA cells generated repopulating stem cells in the primary recipients as much as bone marrow competitor cells, we performed secondary transplantation with bone marrow cells of the primary recipients. Bone marrow cells were obtained from the adult recipients of 20 T+ KSLA cells at 25 weeks after transplantation, stained with anti-Ly5.1 and -Ly5.2 antibodies, and analyzed on a FACS. We selected 2 representative mice for secondary transplantation. One mouse had 70% chimerism for T+ KSLA–derived cells. The other showed 70% chimerism for bone marrow competitor-derived cells. In both cases, about 4 × 107 bone marrow cells were harvested from both sides of the femora and tibiae. T+ KSLA–derived bone marrow cells (B6-F1) and competitor-derived bone marrow cells (B6-Ly5.1) were independently sorted on a FACS. One million sorted cells were mixed with 2 × 105 freshly isolated adult bone marrow cells (B6-Ly5.2) and transplanted into irradiated mice (B6-Ly5.2).

Table 4 shows the results of secondary transplantation. The reconstitution level at 12 weeks after transplantation was lower than that at 4 weeks after transplantation, presumably reflecting a limitation in self-renewal capacity of HSCs. However, it should be noted that the reconstitution levels by T+ KSLA cells at 4 and 12 weeks after transplantation were comparable to those by primary bone marrow competitor cells. We observed reconstitution in myeloid, B, and T cells in all mice (Table2). These data suggest that 20 T+ KSLA fetal liver cells are equivalent to 2 × 105 unfractionated bone marrow cells in terms of their self-renewal potential.

Secondary transplantation of bone marrow cells from the recipients of T+ KSLA fetal liver cells

| Origins of the cells . | Time after transplantation, wk . | Positive mice . | % Chimerism . |

|---|---|---|---|

| T+KSLA | 4 | 3/3 | 16.1 ± 1.0 (n = 3) |

| 12 | 3/3 | 3.9 ± 2.1 (n = 3) | |

| Competitor | 4 | 6/6 | 15.4 ± 6.0 (n = 6) |

| 12 | 6/6 | 3.5 ± 1.9 (n = 6) |

| Origins of the cells . | Time after transplantation, wk . | Positive mice . | % Chimerism . |

|---|---|---|---|

| T+KSLA | 4 | 3/3 | 16.1 ± 1.0 (n = 3) |

| 12 | 3/3 | 3.9 ± 2.1 (n = 3) | |

| Competitor | 4 | 6/6 | 15.4 ± 6.0 (n = 6) |

| 12 | 6/6 | 3.5 ± 1.9 (n = 6) |

Primary recipients had transplantation with 20 T+KSLA cells of B6-F1, together with 2 × 105 bone marrow competitor cells of B6-Ly5.1. At 25 weeks after transplantation, the recipients presenting about 70% chimerism of either fetal liver– or competitor-derived cells were selected and used as donors. Bone marrow cells presenting F1 type or Ly5.1 type were independently sorted on a FACS, and 1.0 × 106 sorted cells of F1 or Ly5.1 type were transplanted into irradiated B6-Ly5.2 mice together with 2 × 105 freshly isolated bone marrow cells of B6-Ly5.2.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that the Tie-2 receptor is expressed in Kit+, Sca-1+, Lin−/low, AA4.1+ (KSLA) HSCs in the fetal liver at day 14 of gestation of a mouse embryo. The Tie-2 expression was detected in about 7% of KSLA cells. An in vitro clonal assay revealed a higher frequency of highly proliferative colony-forming cells in the Tie-2–positive fraction than in the Tie-2–negative fraction among KSLA fetal liver cells (Figure 3). This finding led us to compare in vivo long-term reconstituting activity between Tie-2–positive and –negative KSLA cells. A competitive repopulation assay in irradiated adult mice resulted in long-term repopulation with 10 T+ KSLA cells, but not with 100 10 T− KSLA cells (Table 1). Given the frequency of 1 repopulating cell per 7.9 T+ KSLA cells (Figure 5), T+ KSLA cells with repopulating activity are calculated to be present at approximately 2 cells per 105fetal liver cells. This is comparable to our estimated frequency of HSCs (2-4 per 105 cells) using unseparated fetal liver cells28 (H.N. et al, unpublished data, December 1999). In addition, the repopulating activity of KSLA cells was shown to be totally represented by that of T+ KSLA cells (Table 1). Further, the self-renewal potential of these repopulating T+ KSLA cells was confirmed by a successful secondary transplantation (Tables 2 and 4). Taken together, these data indicate that T+ KSLA cells represent a large part, if not all, of HSCs in the fetal liver.

We have previously shown that at least 1 of 5 CD34− KSL cells is a repopulating stem cell in the adult bone marrow.18 It should be possible to compare directly the developmental potential of fetal liver and bone marrow HSCs at the clonal level.

It has been proposed that yolk-sac HSCs favor the hematopoietic microenvironment in the newborn liver when they home, proliferate, and differentiate.27 We addressed whether T+ KSLA fetal liver cells reconstitute hematopoiesis of newborn mice better than that of adult mice. However, T+ KSLA fetal liver cells were able to repopulate in the adult and newborn environments (Table3). These fetal liver HSCs appeared to engraft equally in adult and newborn recipients.

Endothelial cell progenitors, which are present in the human peripheral blood, and their differentiated cells have been shown to express Flk-1, Tie-2, and CD34 molecules.35 The expression of these molecules was detected in T+ KSLA fetal liver cells. Recently, it has been reported that Flk-1 is expressed in human CD34+ cells capable of reconstituting the hematopoietic system of nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD/SCID) mice and fetal sheep.36 Because Tie-2–positive AGM cells have been shown to differentiate along hematopoietic and endothelial lineages,24 it is likely that T+KSLA fetal liver cells are also able to differentiate into endothelial cells.

We have used several culture systems to develop endothelial cells in vitro. However, so far we have not succeeded in efficient generation of endothelial cells from T+ KSLA fetal liver cells under the conditions described to obtain endothelial cells in culture from adult bone marrow cells.37 It is possible that the culture condition is not sufficient for the development of the endothelial lineage from fetal liver cells. Alternatively, the developmental potential is different between fetal liver and bone marrow cells. Further studies will be required to address this issue.

Both Tie-2 receptor and its agonistic ligand, angiopoietin-1, were expressed in T+ KSLA cells. Because these transcripts were also detected in CD34+ KSL cells of the adult bone marrow, we speculate that an autocrine or paracrine mechanism controls the development of hematopoiesis and angiogenesis. Further studies may reveal the role of angiopoietin-1 and Tie-2 interaction in the function of HSCs.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Iwama and A. Shibuya for their critical reading of the manuscript.

Supported by grants from CREST of Japan Science and Technology Corporation; the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture in Japan; the Agency for Science and Technology; and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS-RFTF96I00202).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Hiromitsu Nakauchi, Department of Immunology, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Tsukuba and CREST (Japan Science and Technology Corporation), 1-1-1 Tennodai, Tsukuba, 305-8575 Japan; e-mail: nakauchi@md.tsukuba.ac.jp.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal