Abstract

Mouse plasma cell tumor (PCT) and human multiple myeloma (MM) are terminal B-cell malignancies sharing many similarities. Our recent work demonstrated that activation of the insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF-IR)/insulin receptor substrate (IRS)/phosphatidylinositol 3′ kinase (PI 3′K) pathway was evident in the tumor lines derived from both species. Although PI 3′K activity was higher in mouse tumor lines than that in human tumors, activation of Akt serine/threonine kinase was markedly lower in mouse lines. This discrepancy prompted us to test the status of PTEN tumor suppressor gene, as it has been shown to be a negative regulator of PI 3′K activity. Although all the mouse lines expressed intact PTEN, 2 of the 4 human lines (Δ47 and OPM2) possessing the highest Akt activity lost PTEN expression. Sequencing analysis demonstrated that the PTEN gene contains a deletion spacing from exon 3 to exon 5 or 6 in the Δ47 line and from exon 3 to 7 in the OPM2 line. Restoration of PTEN expression suppressed IGF-I–induced Akt activity, suggesting that loss of PTEN is responsible for uncontrolled Akt activity in these 2 lines. Despite the expression of PTEN with the concomitant low Akt activity in all mouse PCT lines, their p70S6K activities were generally higher than those in 3 human MM lines, arguing for specific negative regulation of Akt, but not p70S6K by PTEN. These results suggest that p70S6K and Akt may be differentially used by the plasma cell tumors derived from mice and humans, respectively.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a terminal B-cell malignancy, which accounts for 1% of total cancers, and to date, available treatment options are largely ineffective. The etiology and signaling pathways leading to the tumorigenesis are not fully elucidated.1 However, activation of interleukin 6 (IL-6) signaling and the translocation of IgH locus to other chromosomes, resulting in their subsequent activation, are common phenomena in the pathogenesis of myeloma development.2 Stimulation of the IL-6 receptor pathway leading to the activation of the Ras/Raf/MAPK cascade3 and constitutive activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 34 have been linked to disease development. Loss of chromosome fragments in chromosome 11 and 13 has been well documented from patient samples, although the potential tumor suppressor genes from these chromosomes have not been cloned.5

Mouse plasma cell tumor (PCT) is the counterpart disease of human MM.6 It can arise either spontaneously or be chemically induced by mineral oil or pristane,7-9 or by retroviral infections, including v-raf/v-myc10-12 and v-abl/v-myc13 oncogenes. Genetically, chromosome translocation involving IgH locus linked to c-myc activation is almost invariably detected from the spontaneous PCTs.6 Recently, the T-cell and IL-6 dependency has been demonstrated for the induction of PCTs by v-raf/v-myc oncogenes.14-16 On the other hand, v-abl/v-myc oncogenes seem to be able to bypass the IL-6 and T-cell requirement to induce tumors.16 Interestingly, the constitutive and IL-6–dependent STAT3 activation has also been observed in v-abl/v-myc– and v-raf/v-myc–induced PCTs, respectively.16 Because both mouse and human plasma tumors share many similarities, including IL-6 and T-cell dependency for tumorigenicity, chromosome translocation involving IgH loci, and signal transduction affecting the STAT3 pathway, the mouse model mimics human disease, which allows us to compare the signal transduction pathways.17

Recently, our group has attempted to uncover the molecular mechanisms involved in PCT development.18 Our results indicated that overexpression and activation of insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) receptor (IGF-IR) was detected in both raf/myc and chemically induced PCT lines. Constitutive activation of the insulin receptor substrate (IRS)-2 and phosphatidylinositol 3′ kinase (PI 3′K) cascade was evident in all mouse tumors induced by eitherraf/myc or abl/myc oncogenes or by chemical reagents. The importance of IGF-IR activation in tumorigenesis was further demonstrated by expressing a dominant-inhibitory mutant of IGF-IR in several mouse lines, which specifically inhibited tumor development in syngeneic Balb/c mice. In human MM, activation of IGF-IR resulting in IRS-1 tyrosine phosphorylation and PI 3′K association with IRS-1 has also been observed (W. Li, unpublished observation). These results suggest that the enhanced IGF-IR activity and the IRS/PI 3′K pathway may be involved in the terminal B-cell tumor development.

Activation of PI 3′K leading to generation of phosphatidylinositol (PI) phosphates, including PI-3,4,5-P3 (PIP3), has been linked to proliferating and survival pathways.19,20The Akt/PKB serine/threonine kinase, which binds to PIP3with high affinity, has been defined to be an important signaling molecule downstream of PI 3′K.21 In response to growth factor or cytokine stimulation, the elevated PIP3 recruits Akt from the cytosol to the plasma membrane, where it can be phosphorylated by 3′-phosphoinositide–dependent kinase 1 and another unknown kinase on Thr308 and Ser473, respectively. Activated Akt subsequently phosphorylates several substrates, including BAD (BCL-2/Bcl-XL-antagonist, causing cell death), glycogen synthase kinase-3, forkhead transcription factor, and nitric oxide synthase, leading to the suppression of apoptosis by several different mechanisms.22

PTEN is a recently identified tumor suppressor gene,23,24which has a dual phosphatase activity toward both phosphotyrosine25 and phospholipid substrates.26 Dephosphorylation of PI 3′K products, mainly PIP3, by PTEN leads to the decreased level of this important phospholipid and the concomitant reduction in Akt activity. Thus, PTEN expression is considered to be an important negative regulator controlling the PI 3′K/Akt activation in vivo.27Conversely, loss of PTEN expression has been detected in many cancers, including glioblastomas, breast and prostate carcinomas, and several syndromes with multiple tumor incidences, including Cowden disease, Lhermitte-Duclos disease, and Bannayan-Zonana syndrome.28When PTEN gene is restored in glioblastomas or other PTEN null cells, the Akt activity is suppressed, linking the role of PTEN to Akt activation directly.29-32 Interestingly, high incidence of hematopoietic tumors and lymphoid hyperplasia were observed in several PTEN heterozygous mice,33 34 strongly suggesting the role of PTEN in regulating hematopoietic cell proliferation, cell death, and malignant transformation.

Although both human and mouse tumors were found to utilize IGF-IR/IRS/PI 3′K as a major signaling cascade to transmit signals, we present data here that they diverge significantly downstream of PI 3′K activation. Although Akt activation, due to loss of PTEN, is observed in MM lines, the p70S6K activity, also controlled by PI 3′K, is not affected by PTEN expression.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and culture

Cell lines used in these studies include the following: B-cell line — WEHI231; and plasma cell lines — S107 and X24 (oil induced), 7.2 and 12.2 (raf/myc induced), and 121.1 and 128.3 (abl/myc induced). All lines were grown in RPMI 1640 containing 10% calf serum and 2-mercaptoethanol. For human myeloma cell lines, they were cultured in RPMI containing 10% fetal bovine serum.35 Human ANBL6 line was kept in the same media with human IL-6.

DNA constructs, transfection, and retroviral infection

The human PTENWT and C124S mutant cDNAs cloned in the pCMV vector, kindly provided by Dr J. Dixon,26 were subcloned into pLXIN vector (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) by EcoRI andSalI digestion. The PT67 packaging line was transfected with different DNA constructs by using calcium phosphate coprecipitation, as described previously.36 Supernatants derived from transfected PT67 cells were cocultivated with target cells (MM or PCT lines) in the presence of 8 μg/mL of polybrene (Sigma, St Louis, MO) for 12 hours. The infected target cells were selected out by G418 (750 μg/mL; Gibco BRL, Rockville, MD).

Cell lysates, immunoprecipitation, and immunoblot analysis

Cells were serum starved for 2 hours in Dulbecco's Modified Essential Medium containing 25 μmol/L of Na3VO4 and were either not treated or stimulated with human IGF-I (100 ng/mL) (Intergen, Purchase, NY) for 10 minutes at 37°C. Cell pellets were lysed in a Triton X100 containing buffer.36 Equivalent amounts of cell lysates (2 mg per sample) were immunoprecipitated with anti-PTEN (Santa Cruz, SC7974, Santa Cruz, CA). Washed immunoprecipitates were electrophoresed on 8% SDS-PAGE gels, transferred to Immobilon P (Millipore, Bedford, MA), and immunoblotted with anti-Flag (Kodak, New Haven, CT). For direct Western analysis, anti-PTEN (Santa Cruz; SC6818), anti-Akt (Santa Cruz; SC1618), or anti-P-Akt (Ser473) (New England BioLab, Beverly, MA) was utilized. Proteins were detected using an ECL system from Amersham (Piscataway, NJ).

PI 3′K activity assay

Cells were similarly treated and lysed as described previously. Equivalent amounts of cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti–IRS-2,37 anti–IRS-1,37 or anti-phosphotyrosine (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) and subjected to PI 3′K activity assay by measuring the phosphorylation of PI to yield PIP3 as previously reported.38

Akt activity assay using Histone H2B as a substrate

The method used for measuring Akt activity in vitro has been reported elsewhere.39

The p70S6K activity assay

Various cell lines were similarly treated, as stated previously, and lysed. Equivalent amounts of cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-p70S6K (Santa Cruz; SC230) or anti-Grb2 (Santa Cruz; SC255; negative control). Washed immunoprecipitates were subjected to a S6K activity assay using a kit from Upstate Biotechnology containing a peptide AKRRRLSSLRA as substrate. The results were the mean value from 2 independent experiments.

Genomic Southern blot analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated using an Easy DNA kit from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The 10 μg of genomic DNA was digested with either HindIII or EcoRI overnight and separated by 0.7% agarose gel. DNA transfer and hybridization were performed according to the standard protocol.40 Human PTEN cDNA (1.2 kilobase [kb]) was labeled using a random primer labeling kit from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA) and used as a probe for the hybridization. Washed membranes were autoradiographed.

Northern blot analysis

The method of total RNA preparation and Northern blot analysis has been previously described.38

One-step reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction, TOPO TA cloning, and sequencing analysis

One-step reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed according to the instruction from the manufacturer (Gibco, BRL). The 5′ primer used was 5′ACGAATTCATGACAGCCATCATCA 3′ and the 3′ one was 5′ ATGGATCCTCAGACTTTTGTAATT 3′. PCR was run for 30 cycles (94°C for 15 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 1 minute). The PCR products were subcloned to TOPO TA cloning vector (Invitrogen) and subsequently sequenced using the ABI system.

In vivo tumorigenesis

Parental and PTEN infected cells were injected intraperitoneally (2 × 106 cells per mouse) into female BALB/c mice 24 hours after pristane priming. Tumor development was monitored twice per week.

Results

PI 3′K activity was strongly detected in all mouse PCTs, but only weakly detected in human MM lines

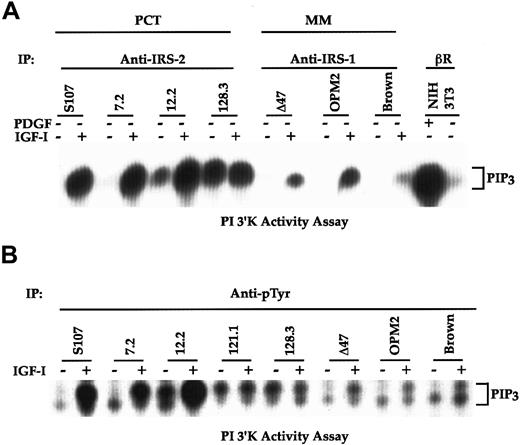

To determine the downstream signaling events linked to IGF-IR activation and IRS phosphorylation, we analyzed PI 3′K activity from the human MM and mouse PCT lines. As shown in Figure1A, PI 3′K activity estimated as PIP3 yields in anti–IRS-2 immunoprecipitates was greatly increased in response to IGF-I stimulation in S107 (chemically induced) and 7.2 and 12.2 (raf/myc induced) mouse plasma cell tumors. Constitutive PI 3′K activity was detected in the 128.3 mouse plasma cell line (abl/myc induced). The PI 3′K activity measured by PIP3 production correlated with our previous observation in which p85 subunit of PI 3′K was coprecipitated with the phosphorylated IRS-2 in vivo, either IGF-I dependently for chemical andraf/myc PCTs or constitutively for abl/myclines.18 Because IRS-1, instead of IRS-2, was preferentially phosphorylated in response to IGF-I in human MM lines (W. Li, unpublished observation), anti–IRS-1 immunoprecipitates were used to recover PI 3′K activity from MM lines. Again, the IGF-I–dependent PI 3′K activity associated with IRS-1 was detectable. However, the activity was much lower in MM than in PCT lines. Stimulation of mouse NIH3T3 fibroblasts with the platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB) resulted in a robust increase in PI 3′K activity as determined by using anti–PDGF-βR for immunoprecipitation and showed as a positive control.

PI 3′K activity is higher in mouse than in human plasma cell tumors.

(A) Various cell lines were serum starved for 2 hours and either left untreated or stimulated with IGF-I for 10 minutes. Equivalent cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti–IRS-2 (for PCT lines) or anti–IRS-1 (for MM lines) and subjected to a PI 3′K activity assay as previously described.38 NIH 3T3 fibroblasts were serum starved overnight and treated with PDGF-BB (100 ng/mL) for 10 minutes. Cell lysates from NIH 3T3 cells were immunoprecipitated with anti–PDGF-βR and included in the assay as a positive control. (B) Cells were similarly treated as in panel A and equivalent amounts of cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-pTyr. Washed immunoprecipitates were subjected to a PI 3′K activity assay. The PIP3 products of PI 3′K activation are indicated.

PI 3′K activity is higher in mouse than in human plasma cell tumors.

(A) Various cell lines were serum starved for 2 hours and either left untreated or stimulated with IGF-I for 10 minutes. Equivalent cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti–IRS-2 (for PCT lines) or anti–IRS-1 (for MM lines) and subjected to a PI 3′K activity assay as previously described.38 NIH 3T3 fibroblasts were serum starved overnight and treated with PDGF-BB (100 ng/mL) for 10 minutes. Cell lysates from NIH 3T3 cells were immunoprecipitated with anti–PDGF-βR and included in the assay as a positive control. (B) Cells were similarly treated as in panel A and equivalent amounts of cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-pTyr. Washed immunoprecipitates were subjected to a PI 3′K activity assay. The PIP3 products of PI 3′K activation are indicated.

To exclude that the affinities of anti–IRS-1 versus anti–IRS-2 used for immunoprecipitation led to the differences in PI 3′K activities in human and mouse lines, we included antiphosphotyrosine (anti-pTyr) for immunoprecipitation in a subsequent PI 3′K activity assay. As shown in Figure 1B, stimulation of both chemical (S107) andraf/myc (7.2 and 12.2) PCT lines with IGF-I led to the greatest induction of PIP3. Again, abl/myc lines (121.1 and 128.3) possessed constitutive PI 3′K activity independent of IGF-I. All 3 human MM lines responded to IGF-I for PIP3induction. Consistent with the results shown in Figure 1A, the PI 3′K activity in human lines was much lower than that of mouse lineages. Together, these results indicate that stimulation of the IGF-IR pathway leads to PI 3′K activation in both mouse and human terminal B-cell tumors.

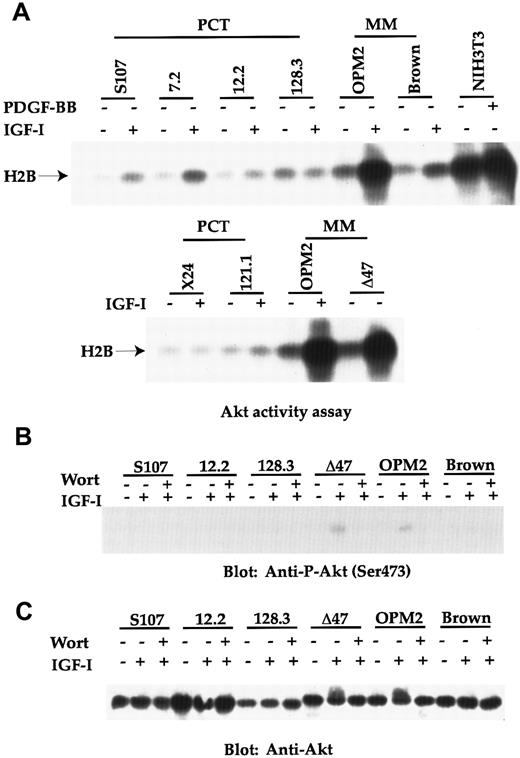

Akt activities detected in mouse and human tumor lines do not correlate with their PI 3′K activation

We next measured Akt activity, as it is known to be a downstream target of PI 3′K and to play a key role in tumor development by suppressing apoptosis.22 To our great surprise, IGF-I–stimulated Akt activities were only weakly induced in chemically (S107) and raf/myc (7.2 and 12.2)-induced plasma cell tumors, but not in abl/myc (128.3 and 121.1) lines and another chemical line (X24) (Figure 2A). In contrast, 2 of 3 human lines (OPM2 and Δ47) analyzed possessed extremely high levels of basal Akt activities, which was further enhanced in response to IGF-I. In contrast, the Brown human MM line had a similar low level of Akt activity as the mouse plasma cell lines. As a positive control, stimulation of NIH 3T3 fibroblasts with PDGF-BB resulted in a strong induction of Akt activity.

Akt activity is greatly induced in the 2 human MM lines (OPM2 and Δ47), but not in any mouse PCT lines.

(A) Cell lines were serum starved for 2 hours and either untreated or stimulated with either IGF-I (100 ng/mL) or PDGF-BB (100 ng/mL) for 10 minutes. Equivalent amounts of cell lysates from each sample were immunoprecipitated with anti-Akt serum. Washed immunoprecipitates were subjected to an Akt activity assay using Histone H2B as substrate. The kinase reaction was separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred proteins on Immobilon P were detected by autoradiography. Phosphorylated Histone H2B is indicated. (B) Cell lines were similarly treated as in panel A. When wortmannin (100 nmol/L; abbreviated as wort in the figure) was used, it was added 20 minutes before IGF-I stimulation. Equivalent amounts of cell lysates were subjected to a SDS-PAGE. Transferred proteins were immunoblotted with anti–P-Akt (Ser473). (C) The same Immobilon P derived from panel B was reblotted with anti–Akt antibody.

Akt activity is greatly induced in the 2 human MM lines (OPM2 and Δ47), but not in any mouse PCT lines.

(A) Cell lines were serum starved for 2 hours and either untreated or stimulated with either IGF-I (100 ng/mL) or PDGF-BB (100 ng/mL) for 10 minutes. Equivalent amounts of cell lysates from each sample were immunoprecipitated with anti-Akt serum. Washed immunoprecipitates were subjected to an Akt activity assay using Histone H2B as substrate. The kinase reaction was separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred proteins on Immobilon P were detected by autoradiography. Phosphorylated Histone H2B is indicated. (B) Cell lines were similarly treated as in panel A. When wortmannin (100 nmol/L; abbreviated as wort in the figure) was used, it was added 20 minutes before IGF-I stimulation. Equivalent amounts of cell lysates were subjected to a SDS-PAGE. Transferred proteins were immunoblotted with anti–P-Akt (Ser473). (C) The same Immobilon P derived from panel B was reblotted with anti–Akt antibody.

Phosphorylation of Akt on Ser473, another indicator of Akt activation41 was subsequently tested. Although phosphorylation on this site was easily detectable in OPM-2 and Δ47 human tumor lines in response to IGF-I, no significant phosphorylation was found in any of the mouse PCT lines (Figure 2B and data not shown for other PCT lines). The PI 3′K specific inhibitor, wortmannin, inhibited Akt phosphorylation on Ser473 in OPM2 and Δ47 lines in response to IGF-I, supporting the importance of PI 3′K in activating the Akt pathway.

The lower Akt activities in all the mouse plasma cell lines, compared with the 2 human MM lines (OPM-2 and Δ47), were not caused by the lower expression of Akt. As can be seen in Figure 2C, mouse plasma cell lines express similar levels of Akt as those human lines. Interestingly, the slower mobility of Akt, another indicator of Akt phosphorylation and activation, on SDS-PAGE was observed in OPM2 and Δ47 lines, in response to IGF-I, thus correlating with the increased Akt activity in these lines. Again, the slower mobility was reversed on adding wortmannin. Taken together, our results demonstrate that Akt activation is only observed in the 2 human MM lines, but not in mouse PCT lines, indicating that signaling in the tumors derived from these 2 species may diverge at this point.

Loss of PTEN expression in OPM2 and Δ47 MM lines correlates with the uncontrolled Akt activation

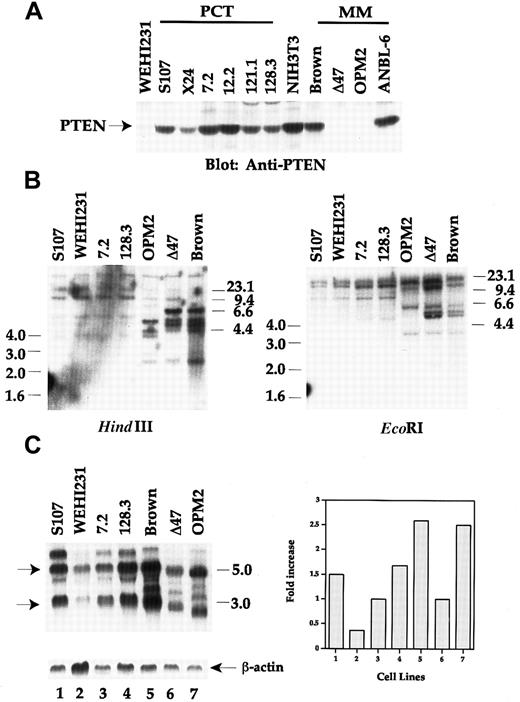

To explore the molecular basis for the discrepancy between human and mouse plasma cell tumors concerning Akt activation linked to PI 3′K, we tested whether the PTEN expression status was related to the enhanced Akt activity in human cells. Correlating with the uncontrolled high Akt activity, PTEN expression was lost in the 2 human myeloma lines (OPM2 and Δ47), as determined by Western blot analysis using anti-PTEN antibody recognizing the N-terminus of the sequence (Figure 3A). The other 2 human myeloma lines (Brown and ANBL-6) possessed wild-type PTEN, and Brown had low Akt activity (Figure 2). Similarly, PTEN expression was detected in all mouse PCT lines. One mouse B lymphoma line, WEHI231, had very low PTEN expression. Together, the expression pattern of PTEN between human and mouse plasma cell tumor lines conversely correlates with Akt activity.

Loss of PTEN expression due to genomic DNA rearrangement in OPM2 and Δ47 human MM lines.

(A) Equivalent amounts of cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-PTEN. (B) Genomic DNA was isolated from the cell lines shown in the figure. 10 μg of genomic DNA was digested with either HindIII or EcoRI overnight and separated by 0.7% agarose gel. DNA transferred membrane was hybridized with 1.2-kb human PTEN cDNA probe. Washed membrane was autoradiographed. DNA size markers are shown. (C) Twenty μg of total RNA from each sample was fractionated using the Trizol Reagent and hybridized with human PTEN cDNA probe (upper left panel). The 3.0- and 5.5-kb PTEN transcripts are marked by arrows. The same membrane was stripped and rehybridized with β-actin probe (lower left panel). After normalization for RNA loading by β-actin control, the RNA levels are arbitrarily plotted by using 7.2 and Δ47 as basal levels for mouse and human lines, respectively (right panel).

Loss of PTEN expression due to genomic DNA rearrangement in OPM2 and Δ47 human MM lines.

(A) Equivalent amounts of cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-PTEN. (B) Genomic DNA was isolated from the cell lines shown in the figure. 10 μg of genomic DNA was digested with either HindIII or EcoRI overnight and separated by 0.7% agarose gel. DNA transferred membrane was hybridized with 1.2-kb human PTEN cDNA probe. Washed membrane was autoradiographed. DNA size markers are shown. (C) Twenty μg of total RNA from each sample was fractionated using the Trizol Reagent and hybridized with human PTEN cDNA probe (upper left panel). The 3.0- and 5.5-kb PTEN transcripts are marked by arrows. The same membrane was stripped and rehybridized with β-actin probe (lower left panel). After normalization for RNA loading by β-actin control, the RNA levels are arbitrarily plotted by using 7.2 and Δ47 as basal levels for mouse and human lines, respectively (right panel).

To further characterize the loss of PTEN expression in those 2 human MM lines, we performed genomic Southern blot analyses by using human PTEN cDNA as a probe. As shown in Figure 3B in the left panel,HindIII digestion showed that OPM2 lost 2 bands of 6.6 and 4.6 kb when compared with the digestion pattern in the Brown line, but generated one extra band of 4.2 kb. The intensities of 2.5-kb bands were much weaker in both OPM2 and Δ47 lines than that of Brown. Two bands of 6.0 and 5.8 kb were lost in OPM2 cells by EcoRI digestion (right panel of Figure 3B). Three PCT lines, representing chemical (S107), raf/myc (7.2)- and abl/myc(128.3)-induced tumors, did not show any alteration in genome structure of PTEN. No significant changes were detected in the WEHI231 line, despite the low protein expression (Figure 3A).

To determine the expression of PTEN at the transcriptional levels, we performed a Northern blot analysis using human PTEN cDNA as a probe. As seen in Figure 3C, 2 major transcripts of 5.5 and 3.0 kb were detected in most of the lines analyzed. However, the sizes of the transcripts were much smaller in both OPM2 and Δ47 human lines. Furthermore, the intensities of the 2 major transcripts in WEHI231 and Δ47 were much weaker than the other lines after normalizing for the loading with β-actin (lower left panel and right panel of Figure 3C). Taken together, our results in protein, genomic DNA, and RNA analyses demonstrate that OPM2 and Δ47 human lines do not express PTEN protein, which can be explained by genomic DNA rearrangement and altered transcriptional regulation.

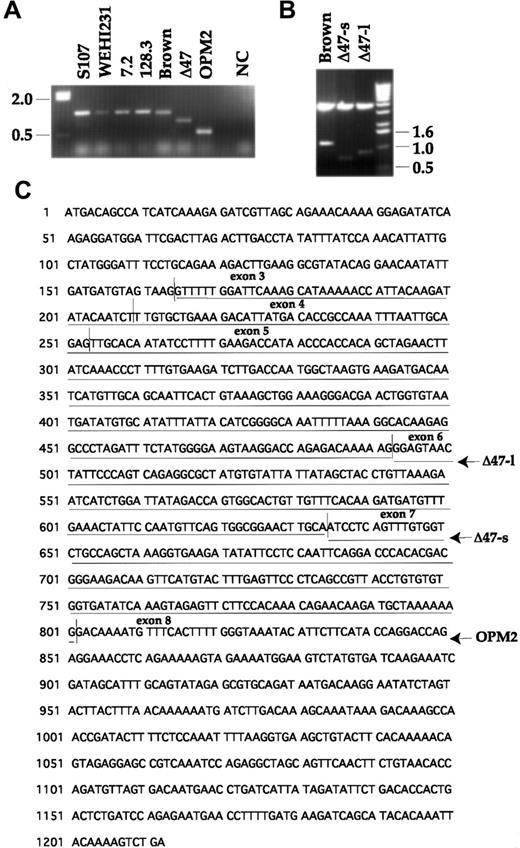

Internal deletion of PTEN gene is detected in OPM2 and Δ47 human myeloma lines

To fully understand the structural, genomic instability of the human MM lines leading to the loss of PTEN expression, we performed an RT-PCR assay and subsequently sequenced the PCR products. As seen in Figure 4A, RT-PCR using primers flanking the translation start codon and stop codon allowed us to amplify 1.2-kb cDNAs from all the 4 mouse lines and the Brown human line. Again, the intensity of the PCR product derived from the WEHI231 line was the lowest. The sizes of PCR products from OPM2 and Δ47 are about 600 and 850 base pair (bp), respectively (Figure 4A). By omitting reverse transcriptase in the reaction of 7.2 raf/myc line, we did not amplify any bands, indicating no genomic DNA contamination in our RNA preparation. When PCR products were subsequently cloned into the TOPO TA cloning vector, 2 complementary DNA (cDNA) inserts in the sizes of about 900 and 700 bp were detected from Δ47 and were thus designated Δ47 long (Δ47-l) and short (Δ47-s), respectively (Figure 4B).

Internal deletion of several exons within PTEN in OPM2 and Δ47 MM lines.

(A) The RNA isolated from each cell line was reverse transcribed to cDNA and amplified using primers flanking the translation start and stop codons of human PTEN cDNA. The RNA from 7.2 line was also subjected to the 1-step RT-PCR without reverse transcriptase and shown as a negative control (NC). (B) The RT-PCR products shown in panel A were subcloned to a TOPO TA cloning vector. The minipreparation of plasmid DNA was digested with EcoRI and run on 1% agarose gel. Both vector and PTEN inserts are shown after ethidium bromide staining. (C) Deletion of exons 3 to 5 in Δ47-l, 3 to 6 in Δ47-s and 3 to 7 in OPM2 are shown after sequencing analysis.

Internal deletion of several exons within PTEN in OPM2 and Δ47 MM lines.

(A) The RNA isolated from each cell line was reverse transcribed to cDNA and amplified using primers flanking the translation start and stop codons of human PTEN cDNA. The RNA from 7.2 line was also subjected to the 1-step RT-PCR without reverse transcriptase and shown as a negative control (NC). (B) The RT-PCR products shown in panel A were subcloned to a TOPO TA cloning vector. The minipreparation of plasmid DNA was digested with EcoRI and run on 1% agarose gel. Both vector and PTEN inserts are shown after ethidium bromide staining. (C) Deletion of exons 3 to 5 in Δ47-l, 3 to 6 in Δ47-s and 3 to 7 in OPM2 are shown after sequencing analysis.

Sequencing analysis indicates that the exons 3 to 5 and to 6 were deleted in Δ47-l and Δ47-s, respectively, generating the transcripts in the sizes of 884 and 742 bp (Figure 4C). The exons 3 to 7 of PTEN are internally deleted in OPM2, resulting in a truncated transcript of 637 bp. Because exon 4 encodes the phosphatase catalytic domain, these results clearly indicate that OPM2 and Δ47 will lose PTEN phosphatase activity in vivo because of the internal deletion of the gene. On the other hand, no obvious deletion and point mutation of PTEN in Brown and WEHI231 were detected in the sequence analysis.

Restoration of PTEN expression in OPM2 and Δ47 lines leads to suppression of Akt activity

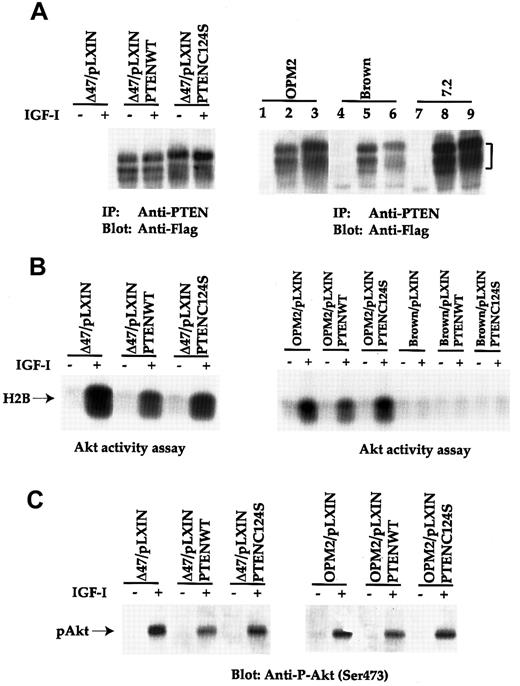

To address whether the loss of PTEN was responsible for the uncontrolled Akt activation, a retroviral vector carrying PTEN was used to infect human MM lines. As shown in Figure5A, expression of both PTENWT and C124S mutant was detected by anti-PTEN immunoprecipitation, followed by anti-Flag immunoblot analysis in all 3 human MM lines. Expression of the same constructs in human lines was not as high as that in the 7.2 mouse line). It was also found that the growth rate of PTENWT-infected cells was much slower in OPM2 and Δ47 lines than in those lines expressing either the vector alone or with C124S mutant (data not shown). Furthermore, many apoptotic cells were detected by PTENWT infection of these 2 lines (data not shown).

Forced expression of PTEN in OPM2 and Δ47 results in suppression of Akt activity.

(A) The human and mouse plasma cell tumor lines infected with PTENWT or C124S mutant retrovirus were immunoprecipitated with anti-PTEN. Transferred proteins were immunoblotted with anti-Flag MoAb. Lanes 1, 4, and 7 represent vector-infected cells. Lanes 2, 5, and 8 indicate PTENWT infectants, and lanes 3, 6, and 9 are obtained from PTENC124S infection. (B) Cell lines were treated similarly as in Figure 2A and subjected to an Akt activity assay. Phosphorylated Histone H2B is indicated. (C) Similar treated cell lines as shown in panel B were immunobloted with anti–P-Akt (Ser473).

Forced expression of PTEN in OPM2 and Δ47 results in suppression of Akt activity.

(A) The human and mouse plasma cell tumor lines infected with PTENWT or C124S mutant retrovirus were immunoprecipitated with anti-PTEN. Transferred proteins were immunoblotted with anti-Flag MoAb. Lanes 1, 4, and 7 represent vector-infected cells. Lanes 2, 5, and 8 indicate PTENWT infectants, and lanes 3, 6, and 9 are obtained from PTENC124S infection. (B) Cell lines were treated similarly as in Figure 2A and subjected to an Akt activity assay. Phosphorylated Histone H2B is indicated. (C) Similar treated cell lines as shown in panel B were immunobloted with anti–P-Akt (Ser473).

The PTEN-infected human lines were subsequently subjected to an Akt activity assay using Histone H2B as a substrate (Figure 5B). About a 50% reduction of Akt activity in response to IGF-I was reproducibly detected from Δ47 and OPM2 lines expressing the PTENWT construct. On the other hand, expression of PTENC124S mutant in the same lines did not affect Akt activity. When PTEN constructs were expressed in the Brown MM line (endogenous PTEN is intact, Figures 3 and 4), no significant changes in Akt activity were observed.

To substantiate our finding that expression of PTENWT in those PTEN null lines did negatively regulate Akt activity, we again measured Ser473 Akt phosphorylation. As shown in Figure 5C, a similar level of reduction of Akt phosphorylation was achieved in both Δ47 and OPM2 lines. Taken together, our results strongly suggest that the loss of PTEN is responsible for the uncontrolled Akt activation in human terminal B-cell malignancy. Combined with the inhibition of cell growth and increased apoptotic cell population in the 2 lines re-expressing PTENWT (data not shown), these data argue for the importance of the PI 3′K/PTEN/Akt pathway in tumor progression of human myeloma origin.

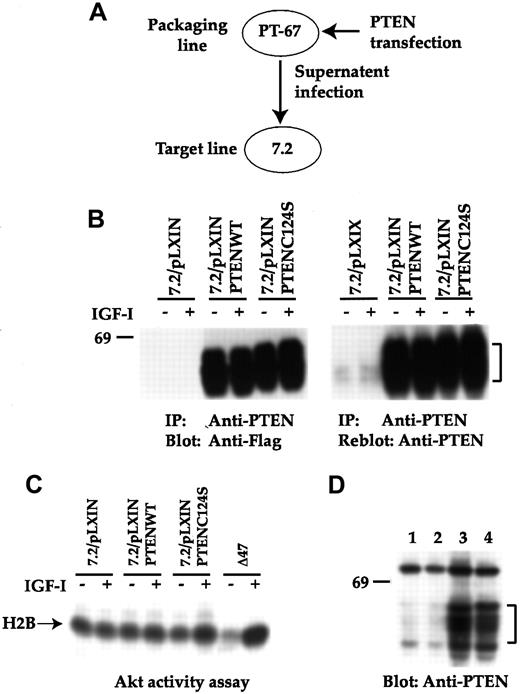

The PTEN/Akt pathway is dispensable for mouse plasma cell tumor development in vivo

To fully exclude the role of PTEN as a tumor suppressor gene for mouse tumor development, we expressed either PTENWT or C124S mutant in the 7.2 raf/myc line by using retroviral gene transfer with pLXIN vector (Figure 6A). On drug selection, more than a 100-fold increase of PTEN protein was achieved (Figure 6B). However, expression of PTENWT did not further affect endogenous Akt activity (Figure 6C), suggesting that endogenously expressed PTEN may be sufficient to negatively control endogenous Akt activation. Similarly, expression of the C124S mutant did not enhance endogenous Akt activity, which may indicate the difficulty of reversing the inhibition of Akt imposed by the existing PTEN. When the new infectants were subjected to tumorigenicity study by injecting the various lines into Balb/c syngeneic mice, tumor developed among all the lines (5 of 5 mice for each group, 2- week latent period, similar sizes for all the 4 groups). Subsequently, tumor cells were harvested from peritoneal cavities and lysed. Expression of either PTENWT or C124S mutant was detected in the corresponding infectants injected (Figure 6D), indicating that overexpression of PTEN does not affect the growth of mouse plasma cell tumors in vivo.

PTEN is dispensable for tumorigenicity of a mouse plasma cell tumor line.

(A) Scheme of the retroviral infection of 7.2 raf/myc line with the various PTEN constructs is shown. (B) Various infectants were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-PTEN and transferred proteins were immunoblotted with anti-Flag (left panel). The same Immobilon P was reblotted with anti-PTEN (right panel). (C) Akt activity assay was performed as described in Figure 2 by using Histone H2B as a substrate. The Δ47 line was used as a positive control. (D) Cell lysates from tumors induced on injecting 7.2 (lane 1), 7.2/vector (lane 2), 7.2/PTENWT (lane 3), and 7.2/PTENC124S (lane 4) were immunoblotted with anti-PTEN.

PTEN is dispensable for tumorigenicity of a mouse plasma cell tumor line.

(A) Scheme of the retroviral infection of 7.2 raf/myc line with the various PTEN constructs is shown. (B) Various infectants were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-PTEN and transferred proteins were immunoblotted with anti-Flag (left panel). The same Immobilon P was reblotted with anti-PTEN (right panel). (C) Akt activity assay was performed as described in Figure 2 by using Histone H2B as a substrate. The Δ47 line was used as a positive control. (D) Cell lysates from tumors induced on injecting 7.2 (lane 1), 7.2/vector (lane 2), 7.2/PTENWT (lane 3), and 7.2/PTENC124S (lane 4) were immunoblotted with anti-PTEN.

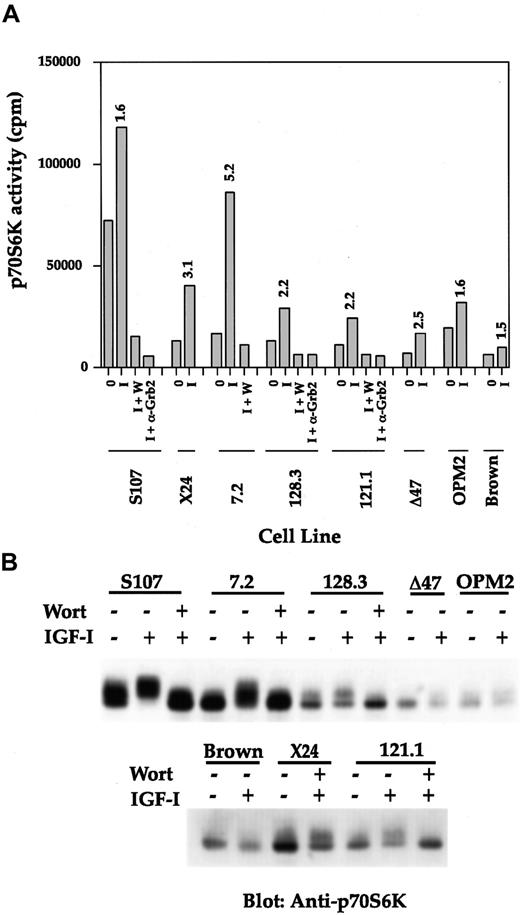

The p70S6K activity is not negatively regulated by PTEN expression and is induced in mouse tumor lines in response to IGF-I stimulation

Having demonstrated that Akt was not active among the all mouse PCT lines, we were interested to know whether other known PI 3′K downstream signaling molecules, such as p70S6K,42 would also be negatively controlled by the expression of PTEN. Conversely, would the p70S6K activity be highly induced in the 2 human MM lines null for PTEN? Thus, p70S6K activity was measured by immunoprecipitating equivalent amounts of cell lysates with anti-p70S6K, followed by an in vitro phosphorylation assay using a peptide, AKRRRLSSLRA, as substrate. As shown in Figure7A, all the mouse PCT lines responded to IGF-I for p70S6K induction, ranging from 1.6- to 5.2-fold. Three human MM lines showed 1.5- to 2.5-fold increases in kinase activities in response to IGF-I. The specific detection of p70S6K activity was demonstrated by using an isotype-matched anti-Grb2 antibody for immunoprecipitation as a negative control. Dependency on PI 3′K for p70S6K activity was established by including wortmannin, which completely reversed IGF-I–induced p70S6K activities in several lines analyzed. The net counts per minute of basal and induced kinase activities were much higher in mouse lines when compared with that of human lines and correlate with the protein levels (Figure 7B). IGF-I stimulation of the 2 abl/myc lines (128.3 and 121.1) reproducibly induced p70S6K activity by 2.2-fold, suggesting that some other pathways other than IRS-2 may be induced by IGF-I to stimulate extra PI 3′K activity in abl transformed lines.

The p70S6K activation is not regulated by PTEN status and transmits signal downstream of PI 3′K in mouse PCT lines.

(A) Various cell lines were serum starved and either untreated or stimulated with IGF-I for 10 minutes. When wortmannin (100 nmol/L; abbreviated as w or wort in the figure) was included, it was added 20 minutes before IGF-I stimulation. Equivalent amounts of cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-p70S6K or anti-Grb2 (negative control). Washed immunoprecipitates were subjected to an in vitro p70S6K activity assay according to the protocol from the manufacturer. Results are the mean value of 2 individual experiments. (B) Same cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred proteins were immunoblotted with anti-p70S6K.

The p70S6K activation is not regulated by PTEN status and transmits signal downstream of PI 3′K in mouse PCT lines.

(A) Various cell lines were serum starved and either untreated or stimulated with IGF-I for 10 minutes. When wortmannin (100 nmol/L; abbreviated as w or wort in the figure) was included, it was added 20 minutes before IGF-I stimulation. Equivalent amounts of cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-p70S6K or anti-Grb2 (negative control). Washed immunoprecipitates were subjected to an in vitro p70S6K activity assay according to the protocol from the manufacturer. Results are the mean value of 2 individual experiments. (B) Same cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred proteins were immunoblotted with anti-p70S6K.

Direct immunoblot analysis using anti-p70S6K antibody showed that more p70S6K protein is expressed in mouse than in human lines (Figure 7B). Furthermore, slower migration indicating kinase activation in response to IGF-I fully correlated with the kinase activities measured using the known substrate (Figure 7A). Again, wortmannin reversed slower migration of p70S6K in several mouse lines in response to IGF-I. Combining the results of p70S6K activity assay and mobility shifting pointing to the stronger induction of p70S6K activity in mouse than in those 2 human lines lacking PTEN expression, our results clearly indicate that p70S6K activation is not negatively regulated by PTEN. The p70S6K may be responsible for transmitting signals downstream of PI 3′K in mouse PCTs.

Discussion

In this study, we present data that PI 3′K was activated in both mouse plasma cell tumors and human multiple myelomas. Interestingly, Akt serine/threonine kinase activity was only induced in 2 of 4 human lines, but not in any of the mouse tumor lines analyzed. By testing the expression of the PTEN tumor suppressor gene, we found a strong inverse correlation between PTEN expression and Akt activation. Ectopic expression of wild-type PTEN was able to suppress Akt activity in the 2 human MM lines lacking the PTEN gene, establishing the causative role of PTEN in regulating PI 3′K/Akt activation loop in human myeloma development. On the other hand, stable expression of PTENWT or C124S mutant in a mouse cell line did not affect Akt activity, or the tumorigenicity in vivo, suggesting that the PTEN/Akt cascade may be dispensable for mouse tumor development. Finally, strong evidence was provided that p70S6K activity was not affected by the status of PTEN in both species. These results reveal a significant difference in signaling pathways downstream of PI 3′K in the terminal B-cell tumors derived from the 2 species. Whereas uncontrolled activation of Akt because of the loss of PTEN may lead to malignant transformation of human MM cells, p70S6K may be preferentially utilized by most of the mouse PCT lines for cell signaling and tumor development.

The pivotal role of PI 3′K in B lymphocyte proliferation has been suggested by the finding that the knockout of p85 α subunit of PI 3′K resulted in the failure of B-cell proliferation and development.43,44 Furthermore, a truncated version of p85 associated with the p110 catalytic subunit has also been isolated from transformed lymphoid cells.45 Deletion of one allele of PTEN also resulted in hyperproliferation of hematopoietic cells with the concomitant activation of Akt.33,34 In addition, Akt was originally cloned from T-cell lymphoma by fusing the Akt with the retroviral sequence.46 47 All these data point to the critical importance of PI 3′K signaling pathway in hematopietic cells, particularly in lymphoid cell transformation.

Signal transduction through the IGF-IR pathway involving the up-regulation and activation of IGF-IR, the activation of the IRS-2/PI 3′K cascade in mouse plasma cell tumor development has been previously elucidated.18 Although either spontaneous (abl/myc) or IGF-I–induced (raf/myc and chemical) PI 3′K activity was very high in the mouse tumors (Figure 1), we failed to detect Akt activation, which may be due to the negative regulation by PTEN. However, we cannot conclude that the endogenous PTEN caused Akt inactivation, as the expression of its C124S mutant in the raf/myc mouse line did not reverse the low level of Akt activation (Figure 6C). Nevertheless, we do not believe that PTEN can have any influence on tumorigenicity, as its overexpression did not affect the size and latency of tumor development in the animal study (Figure 6). Furthermore, several mouse lines expressing the Akt K179M mutant did not suppress mouse tumor development in vivo (W. Li, unpublished observation), excluding the possibility of PTEN/Akt involvement in the pathogenesis of mouse plasma cell tumors.

Despite no induction of Akt activation, stimulation of the mouse lines with IGF-I significantly induced p70S6K activity. On the other hand, the 2 MM lines null for PTEN expression did not show as high p70S6K activity as that of Akt in response to IGF-I. Because it has been known that both Akt and p70S6K are dependent on PI 3′K for activation and that wortmannin can completely suppress both kinase activities, these results no doubt emphasize that p70S6K and Akt are differentially regulated downstream of PI 3′K. Our results are also in agreement with several findings using different cell models in which differential regulation of p70S6K and Akt was observed.48 49 Because PTEN is mainly able to dephosphorylate PIP3 in vivo, it will be tempting to speculate that p70S6K may not fully rely on PIP3 for its activation. It is also possible that the protein kinase activity, rather than lipid kinase activity of PI 3′K may directly activate p70S6K. Regardless of how these 2 molecules are regulated by PI 3′K, our results strongly suggest that signals can be transduced in mouse tumor lines through IRS-2/PI 3′K/p70S6K cascade independent of PTEN expression.

In striking contrast to mouse plasma cell tumors, expression of PTENWT in the 2 human PTEN null lines suppressed the IGF-I–induced Akt activity by 50%, as determined by both kinase activity assay and Ser473 phosphorylation in the stably infected cells (Figure 5). Because the endogenous Akt activity was not completely inhibited by PTENWT expression, it is possible that other signaling pathway(s) independent of PI 3′K activation and PTEN negative regulation may induce Akt activity. It is more likely that the tumor suppressor effect of PTEN expression directly affected cell growth (unpublished observation), which only allowed selection of the lower PTEN expression in the infectants, thus leading to the partial inhibition of Akt. We are currently attempting to establish an inducible system to express PTEN in the human MM lines lacking PTEN expression, to overcome the potential toxicity of high levels of PTEN toward cell growth. However, on the basis of the reconstitution experiment, together with genomic and biochemical data, it is clear that PTEN is a major player controlling Akt activity and cell survival of several human MM lines.

On the cloning of the PTEN tumor suppressor gene, many reports documented its involvement in the etiology and/or the pathology of tumor development, including glioblastoma, prostate carcinoma, thyroid cancer, lung carcinoma, melonoma, and several syndromes exhibiting multiple tumor incidence.28 Recently, several studies indicated that the PTEN gene is mutated and deleted in several kinds of hematopoietic malignancies.50-52 We also observed the extremely low level of PTEN expression in WEHI231 mouse lymphoma line. However, the mutation rate for lymphoma was not very high in those cell lines and fresh samples analyzed. Furthermore, whether the loss of PTEN expression could lead to high Akt activity remains to be determined in lymphomas. We demonstrated the loss of PTEN expression in 2 of 4 human myeloma lines and established the role of PTEN in regulating Akt activity by re-expressing PTEN in the 2 cell lines. To our knowledge, this represents the first evidence for such a large internal deletion of PTEN gene in tumor cells. Because no protein expression was detected and RT-PCR only showed the truncated allele in the OPM2 line, these data suggest that the other allele appears to be completely deleted or nontranscriptional. For the Δ47 line, it is possible that the heterogenous deletion on both alleles contributed to the transcripts in different lengths. Because the exon encoding phosphatase catalytic domain located on exon 4 is deleted in both cell lines, it is expected that its phosphatase function would be completely destroyed. The concomitant activation of Akt in the 2 lines and reversion of Akt activity by reinforced PTEN expression confirmed this idea.

When PTEN was expressed in those 2 PTEN null lines using the pLXIN vector, slower growth and higher apoptotic population of the infected cells were observed (W. Li, unpublished observation), consistent with its role in the inhibition of cell cycle entry and induction of apoptosis.27,30,32 53 Currently, we are attempting to define the functional role of PTEN in the pathogenesis of human myeloma by testing tumorigenicity of PTEN-expressing lines in animal models. Furthermore, the pathologic role of PTEN dysregulation in the various stages of myeloma, particularly at the onset of the disease is another important area for further exploration.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Stuart Rudikoff and Jacalyn Pierce for encouragement and Drs Michael Kuehl and John Dixon for reagents. The critical reviewing of the manuscript by Dr Robert Dickson is also greatly appreciated.

T.H. and A.Y. contributed equally to this work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Weiqun Li, Department of Oncology, Lombardi Cancer Center, Georgetown University Medical Center, New Research Building, E407, 3970 Reservoir Rd NW, Washington, DC 20007; e-mail:wwl@gunet.georgetown.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal